1. Introduction: The Politics of Architecture

In his influential essay

Post-Functionalism, Peter Eisenman critiques mainstream architecture for prioritising external forces—such as clients and capital—over internal disciplinary critique [

1]. He argues that this shift reduces architecture to an apolitical service industry. This persistent notion of architectural neutrality has shaped both professional culture and architectural theory, where innovation is often located in forms and representational strategies rather than in the social and material processes that underpin construction.

In developing economies marked by poverty, unplanned urbanism, weak institutions, and unequal access to land and resources, architectural politics cannot be confined to formal or symbolic critiques. Instead, the political dimension of architecture lies in transforming the social, economic, and institutional systems that structure the built environment [

2]. This raises a crucial question: can a practice concerned with labour organisation, knowledge sharing, and community reintegration be understood as inherently political—even without explicit ideological claims?

Henri Lefebvre argued that space is an active social construct that influences daily life, thereby making architecture fundamentally political [

3]. Land, territory, and displacement form the foundational layer of this political landscape; urban renewal initiatives, infrastructural corridors, and housing policies have historically perpetuated socio-economic hierarchies and segregation [

4]. Patronage further demonstrates how architectural production reflects institutional priorities and aligns with dominant socio-economic interests [

5]. Aesthetics, on the other hand, functions as an ideological instrument of representation and legitimation [

6].

In developing economies, however, the politics of architecture are deeply tied to labour. Construction is carried out by workers whose contributions remain largely invisible, reflecting social hierarchies embedded in the profession [

7]. Whether a project engages local craft, community participation, or precarious migrant labour influences both its social ethics and its political meaning. Thus, architecture is not political because it intends to be, but because it materially arranges relationships between land, labour, knowledge, capital, and power. The relevant question is not whether architecture is political, but whose politics it enacts.

This political complexity is rooted in the discipline’s historical foundations, particularly Alberti’s thinker–maker dualism, which continues to shape architectural authorship, professional hierarchies, and the persistent illusion of apolitical practice.

2. The Conflict at the Origin: The Thinker–Maker Divide

Leon Battista Alberti’s

De Re Aedificatoria (1443–1452) marks the foundational moment in which the architect is separated from the builder. Alberti’s architect is a learned intellectual whose role is to devise ideas, while the builder merely executes them [

8]. This establishes a hierarchy between intellectual authorship and manual labour—a division that has had profound political consequences.

By marginalising the builder’s knowledge, Alberti frames construction labour as instrumental rather than epistemic. The architect becomes a manager of representations [

9], while the builder—often from marginalised social groups—becomes invisible in architectural discourse. This dualism persists today in education, practice, and authorship, producing a profession that is intellectually elevated yet materially detached [

10].

Contemporary scholars such as Peggy Deamer note that this hierarchy continues to shape labour conditions, privilege professional authorship, and obscure the contributions of construction workers [

11]. Although many contemporary practices challenge this model through participatory methods and labour-centred tectonics, the mainstream profession continues to operate under Alberti’s division: architects think and draw, others build.

This structural tension, foundational yet ongoing, sets the stage for examining theories such as critical regionalism, which attempt to mediate between global modernity and local identity but often reproduce the very hierarchies they critique.

3. How Critical is ‘Regionalism’: The Problem of the ‘Marginal’ Interstice

Regionalist architecture emerged in the Global South during the 1960s and 70s as a response to industrialisation, import-substitution policies, and the need for locally appropriate building practices. Over time, however, regionalist strategies shifted from practical material adaptation to symbolic cultural representation.

Kenneth Frampton’s ‘critical regionalism’ sought to counter homogenising global modernism by positioning the architect in the “interstice” between universal civilisation and local culture [

12,

13]. The term ‘critical’ emphasised that this approach is intended as a reflective, evaluative critique—similar to Emmanuel Kant’s ‘test of criticism’—rather than an emotional, biased, or irrational attachment to traditional forms. Yet this framework has been criticised for aestheticising cultural difference while underplaying the structural conditions—colonial histories, labour inequalities, informal economies, class hierarchies—that shape regional contexts.

Keith Eggener [

14], for example, argues that critical regionalism romanticises the peripheral and reduces the region to a cultural atmosphere rather than a site of material relations. Frampton’s architect operates from a position of autonomy reminiscent of Alberti’s dualism, mediating culture rather than engaging with the political economies of land, labour, or institutional power. Eggener highlights that this leads to a culturalist definition of the region, one that privileges symbolic place-making over material spatial justice. The politics of marginality are thus aestheticised rather than interrogated.

In this way, critical regionalism risks stabilising exactly what it claims to oppose: it depicts the region as timeless, rather than as a dynamic historical and economic entity; it treats labour as texture rather than a political and economic relation; it positions the architect as an autonomous cultural mediator, rather than a participant in collective spatial transformation. As a result, critical regionalism resists stylistic universalism but does not confront socio-spatial inequality. It focuses on the representation of culture rather than the production of space.

4. Methodology

This research employs a qualitative, multi-site case study methodology, combined with a practitioner-researcher approach, to investigate how architecture functions as a political process in post-conflict, resource-limited regions. The method examines not only formal outcomes but also the labour, social relations, and institutional negotiations embedded in the production of architecture.

Six projects completed by Robust Architecture Workshop (RAW) between 2013 and 2023 were selected using purposive sampling. Projects were included based on three criteria: (1) engagement with marginalised or structurally excluded labour groups; (2) operation within resource-constrained or politically complex environments; and (3) inclusion of explicit pedagogical or capacity-building components in the construction process.

The study draws on multiple qualitative sources, including project drawings, details, and procurement documents; field observations from design meetings, training sessions, and construction sites; photographic and material documentation; and reflective notes on interactions with soldiers, villagers, farmers, contractors, and public authorities, who, at various capacities, have contributed to the projects as labour stakeholders. Although formal interviews were not conducted, these materials collectively provide a detailed dataset for analysing the political dynamics of architectural production.

Data were examined through an interpretive thematic analysis structured around five analytical dimensions: (1) labour structures – organisation, visibility, and skill circulation; (2) knowledge ecologies – exchange between professionals, workers, and communities; (3) material and technological choices – relations to supply chains and economic constraints; (4) institutional negotiation and procurement – power relations and tactical engagement; and, (5) aesthetic and tectonic expression – visibility of labour and recognition. This framework enabled consistent comparison across projects and the identification of shared political patterns in the design–construction process.

As a practitioner-researcher, the author had unique access to internal processes that are seldom visible in architectural research [

15,

16]. This provides a strong scholarly foundation for assessing architecture as a negotiated and political process.

5. Architecture as Social Process: Post-Conflict Reconstruction

Established in 2012, RAW emerged at a time when Sri Lanka was transitioning from civil war (1987-2009) to uneven reconstruction. In this setting, architecture is inseparable from state power, donor influence, militarisation of development, and the contested rewriting of public memory [

17]. Post-war reconstruction in Sri Lanka has often taken the form of large-scale infrastructural expansion and speculative urban development—projects that privilege capital accumulation and national image-making over local agency [

18]. Against this backdrop, the projects under study foreground architecture as a tool for social reintegration and civic rebuilding, rather than as a demonstration of national progress or global modernity.

5.1. Case Studies as Political Instruments

The case study projects demonstrate how small- and medium-scale buildings can operate as infrastructures of civic repair and social pedagogy rather than merely acting as symbolic monuments of cultural identity.

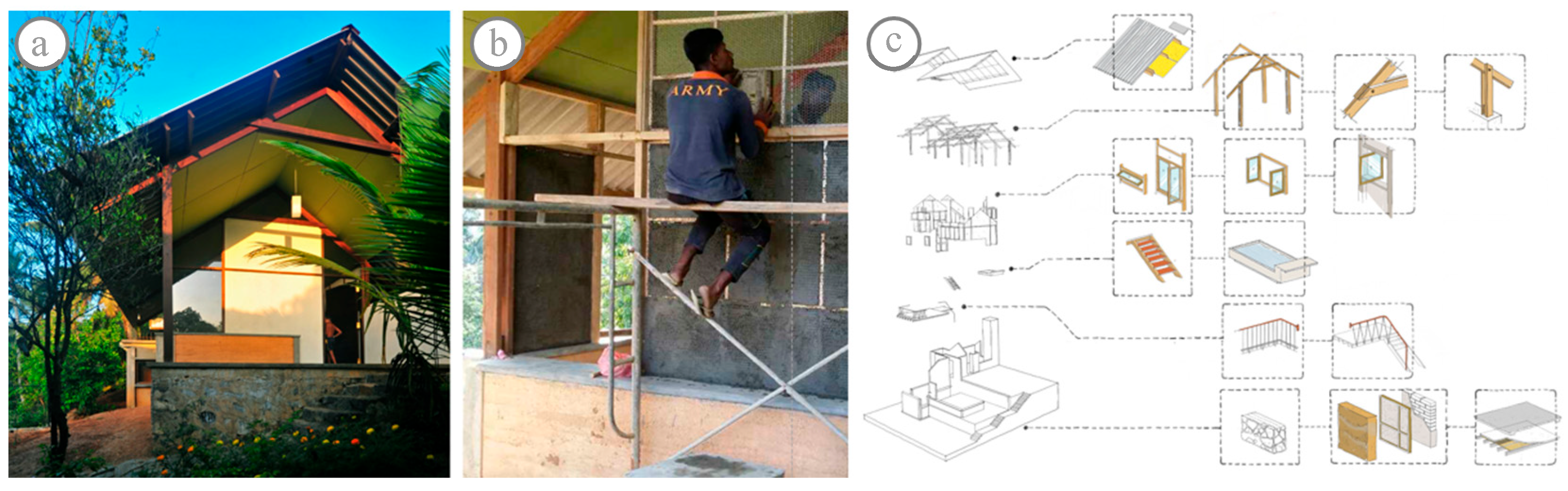

Community Library, Ambepussa: Using soldier-labour in the aftermath of the civil war, the library positioned construction as a means of rehabilitation and skill development (

Figure 1). Instead of viewing ex-combatants as aid recipients or mere labour in a mechanised building process, this initiative involves them as active participants in shaping the project. In doing so, it reconfigures the figure of the soldier—from a symbol of state violence to an agent of civic contribution. The political significance of this is practical rather than symbolic; the architecture acts as a tool for renegotiating social identities and capacities fractured by war [

19,

20,

21,

22].

Dewahuwa School: Situated in a socially deprived rural setting, this project explores a way to build cultural infrastructure by using a production approach that relies on locally sourced materials, social capital, and a network of contributors outside the largely inactive state-led supply system (

Figure 2). The building process generated a replicable typology for educational infrastructure in resource-poor regions, embedding social capital into spatial design [

23,

24].

Sanitary Blocks, Kandy: Addressing deteriorated school facilities, this project linked environmental dignity with typological innovation (

Figure 3). It reduced reliance on imported materials, revived post-independence cement-based construction methods, and supported small-scale territorial suppliers, subtly reorganising regional supply chains. It demonstrates how small infrastructure projects, such as toilets, can support both positive placemaking and industrial restructuring [

23,

25,

26].

Thirappane Farmer Field School: Developed during a national agricultural crisis, the school created a hybrid space for Climate-smart Agriculture (CSA) education and construction training (

Figure 4). Funded by the World Bank and administered by the Ministry of Agriculture, the project supports 15,000 farming families who learn CSA techniques at 60 model farms established and managed by local farmers. Farmers gained skills in sustainable building techniques, connecting spatial learning with economic resilience. They helped build the facilities as a village cooperative and now maintain them, sharing operational benefits [

27].

Primrose House and Wakwella House: These residential projects examined craft and tectonics as strategies for labour training and skill development. While Primrose House reused existing building fabric to refine small builder expertise (

Figure 5), Wakwella House created a transferable, low-cost housing prototype for war widows, connecting domestic space with social equity (

Figure 6). Despite their differences in spending capacity and technical context,both projects aimed to unify ideas of space, craft, and methodology to build capacity onsite and create equally liveable buildings [

28,

29].

Collectively, these projects frame architecture as an active political instrument in post-conflict Sri Lanka, where rebuilding is inseparable from repairing social relations and restructuring inequitable systems. Politically, the work challenges the top-down, technocratic model of reconstruction by mobilising architecture as a participatory, labour-centred process that redistributes agency to communities, ex-combatants, small-scale builders, farmers, and marginalised households. It converts construction into a civic and pedagogical arena where identities fractured by war—such as former soldiers or war widows—are recast as co-producers of public value.

5.1. From Reconstruction to Political Practice

At a systemic scale, the projects critique dysfunctional state supply chains, over-reliance on imported materials, and neglected rural institutions by demonstrating alternative networks of local production, knowledge exchange, and micro-industry support. The political force of this work lies not in symbolic gestures but in reorganising material, economic, and social infrastructures, showing how modest architectural interventions can challenge entrenched inequalities and cultivate new forms of post-disaster citizenship.

To that end, the case study projects align closely with key principles of Frankfurt School critical theory, particularly its concern with the political dimensions of production, labour, and institutional systems. Frankfurt School theorists consistently argued that political agency is not primarily located in symbolic representation, but in the organisation of material processes and the structures through which knowledge, work, and value are distributed [

30]. This perspective supports the projects’ focus on construction not merely as a technical procedure, but as a socio-political process capable of reorganising relationships among workers, institutions, and local communities.

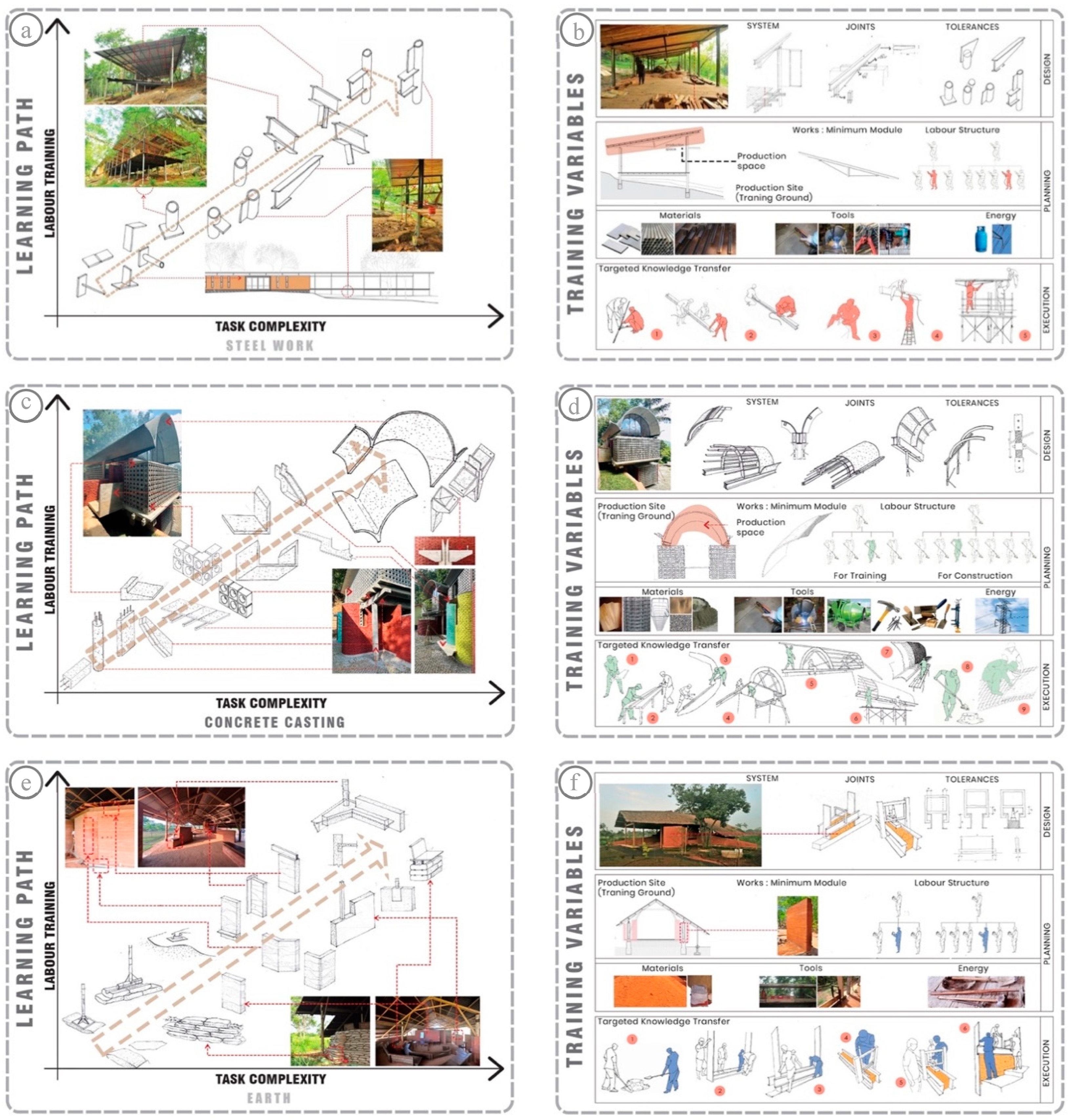

6. Labour, Knowledge, and the Politics of Production

The centrality of labour in these works invites interpretation through the lens of political economy. In developing-world construction industries, labour is often deskilled, outsourced, or rendered invisible within supply chains that privilege professional expertise and subcontracted execution [

31]. The projects under study challenge this hierarchical separation between design and labour by structuring them as pedagogical environments in which technical knowledge is transmitted, shared, and iteratively developed in situ [

32,

33]. Rather than importing expertise, the work cultivates it locally (

Figure 7).

This recalls Partha Chatterjee’s distinction between the civil society (comprising formal institutions and expert knowledge) and political society (which involves informal, negotiated collectivities) [

34]. There is an attempt here to insert architectural knowledge into the sphere of ordinary workers, rural communities, and post-conflict populations—spaces typically excluded from architectural authorship. In doing so, the work destabilises the epistemic privilege of the professional architect, instead producing what might be described as collective authorship of spatial form. The building is thus not only a finished object but also a durable record of social relations, negotiations, and shared skill formation (

Figure 8).

6.1. Knowledge Ecologies and Site-Based Learning

At the core of this approach is the premise that process is political. Instead of treating construction as a technical or purely managerial operation, this work deliberately transforms building into a platform for skill development, labour empowerment, and the redistribution of knowledge. The Community Library in Ambepussa, for example, served as a rehabilitation and reintegration initiative, offering training in rammed-earth construction, steel welding, and construction management to individuals emerging from military life in the aftermath of Sri Lanka’s civil war. Here, the architectural project operates at two levels: formally, as a public library that provides cultural infrastructure, and operationally, as a social mechanism that guides participants into civilian labour networks. The building is not simply a product; it is evidence of a political proposition—that architecture can be a direct instrument of social repair, reconfiguring outcomes of war by enabling new civilian futures.

In rural areas where educational infrastructure often lacks government support and climate resilience, Dewahuwa School utilises local resources, skills training, and robust construction methods to create public buildings that go beyond basic function to embody civic values and processes. Here, the construction team comprised villagers—builders, artisans, and volunteers—most of whom were farmers and parents of students, learning construction skills while actively participating in the building process.

In Thirappane, the agricultural training centre is designed for smallholder farmers adopting sustainable practices, linking knowledge transfer with spatial design. Consequently, architecture functions as both economic infrastructure—enhancing local independence from centralised agricultural systems—and cultural infrastructure through training in CSA and building techniques.

Similarly, the kit-of-parts approach in the toilet project involved training unconventional soldier labour to develop alternative material and labour relations, aiming to reshape the technological landscape of urbanising areas. The two houses, meanwhile, see craft as a skill learned through consistent practice, emphasising its role for functional and educational purposes rather than for formal or decorative reasons.

6.2. Labour Visibility and Material Agency

Collectively, these projects align with Karl Marx’s belief that labour creates epistemological knowledge, which is vital for their social integration [

35]. Marx’s critique of capitalist production arises from his claim that it causes workers to feel alienated from their work, the process, society, and their own identities. On the contrary, the work discussed here seeks to empower ex-combatants, farmers, villagers, and small builder groups, who are often marginalised in architectural production.

By utilising local materials, offering on-site training, and promoting cooperative building practices, these projects confront government neglect, reliance on global supply chains, and the de-skilling of labour. Politically, they aim to transform production into a site of empowerment and labour visibility—building infrastructures that encourage new social connections, educational opportunities and economic prospects.

7. Tactical Pragmatism: Procurement Strategies and Negotiating Power

Regarding the social organisation of the building procurement process, one of the most intellectually demanding aspects of these works is their strategic engagement with the state, military, NGOs, and donor organisations. Instead of opposing these structures or merely acting as tools within them, efforts are made to channel institutional resources toward socially beneficial objectives. Nonetheless, this approach carries inherent tensions. Partnering with military or government bodies can inadvertently reinforce existing hierarchies, despite efforts to mitigate such effects.

Generally, independent architecture practices in developing economies struggle to work on government projects due to pervasive corruption in procurement, commissioning, and delivery [

36]. Inflated budgets, non-competitive bidding, and politically connected contractors undermine transparency, making it difficult for principled architects to participate without compromising their ethics [

37]. Consequently, many withdraw from public work, reinforcing their view that architects and artists should not serve as extensions of state power—particularly when that power lacks accountability. This distance preserves professional integrity but limits their capacity to influence civic architecture and weakens the public realm they might otherwise help to build.

7.1. Limitations of One-Off and Model Approaches

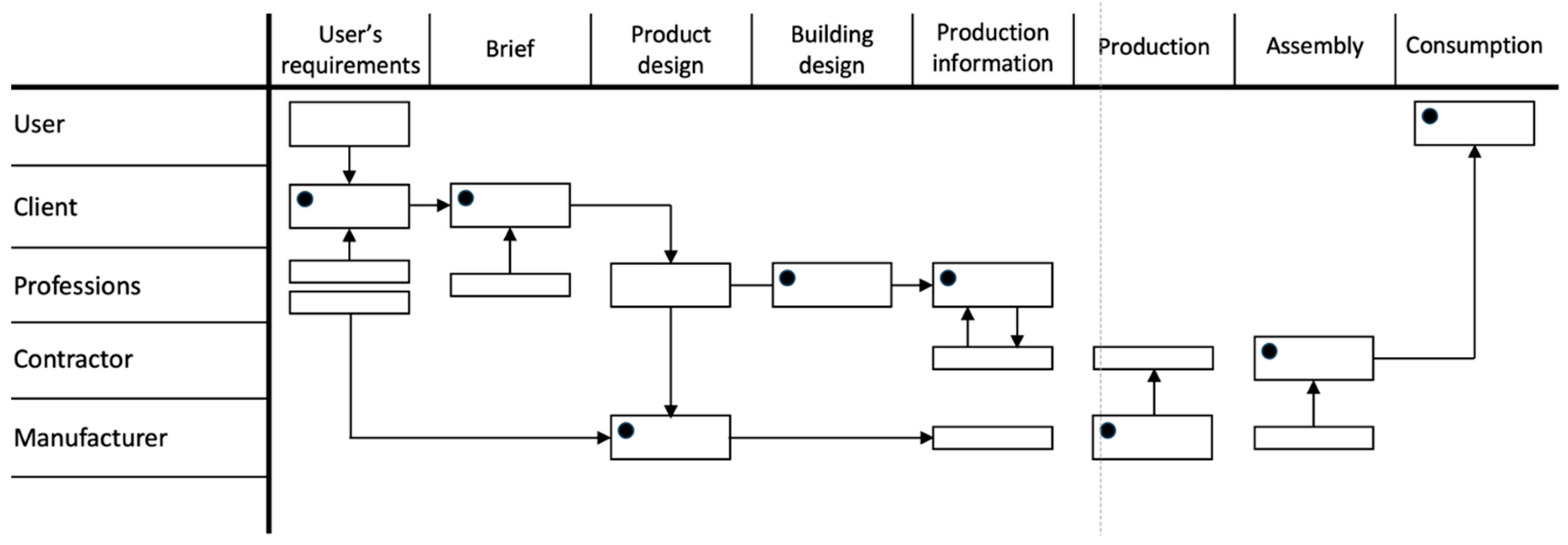

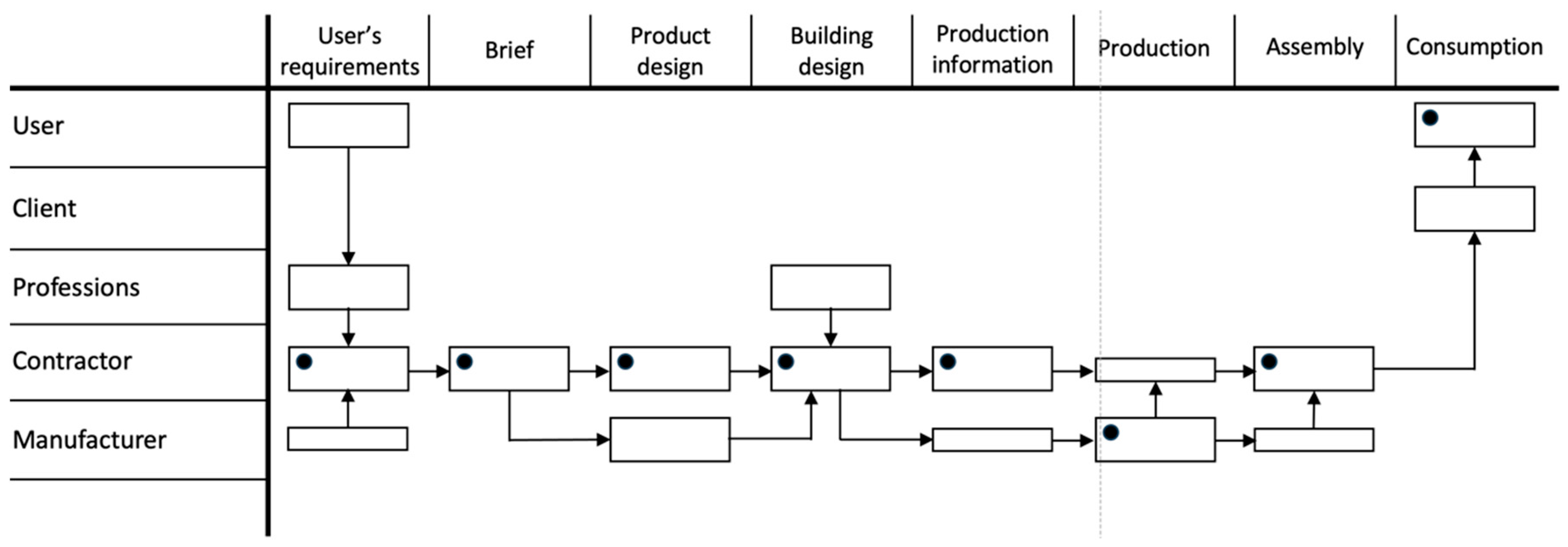

The position explored here considers whether architecture can serve as a subtle form of subversion, changing systems through tactical intervention rather than external critique. The work’s political strength then lies in its ability to navigate power relations by acting as an independent authority within procurement processes, transforming institutional frameworks into platforms for public benefit. In developing economies, public works are generally procured using either ‘one-off’ or ‘model-based’ methods, as described by the Construction Economist Duccio Turin [

38]. The ‘one-off’ approach involves creating unique products that are sold before production, with the producer agreeing to the specifications set by the designer and client in advance (

Figure 9). Conversely, the ‘model’ approach grants the producer – or contractor - control over production, emphasising the standardisation of the final product (

Figure 10).

Both methods, however, have significant drawbacks on their own. The ‘one-off’ approach involves a straightforward, step-by-step transfer of project responsibilities: starting with the client managing brief creation, then designers developing the scheme, followed by the contractor supervising assembly, and finally, the manufacturer leading production. Here, limited contractor involvement during the design phase diminishes motivation for labour integration, knowledge sharing, and labour training planning. Conversely, the ‘model’ approach designates the contractor or developer as the main initiator and leader throughout the project, resulting in less professional and user input. Both methods share weaknesses, such as poor coordination among project actors and socio-cultural separation between design and construction activities.

7.2. The Process Approach and Knowledge Exchange

In contrast, the projects discussed here adopt a procurement strategy that involves all stakeholders from the outset, emphasising shared values and non-monetary incentives. This approach helps recognise individual motivations, fosters collaborative development of training strategies, and encourages shared authorship of the project. The integrated work style aligns with Turin’s ‘process’ approach, which emphasises the early appointment of contractors and manufacturers to build a cohesive team capable of consistent decision-making from the beginning [

38].

Early team selection includes professionals in brief creation and design development, especially concerning the connection between building design and labour training. It also provides design professionals with political space to define their terms of engagement with project initiators and funders—whether from the state, NGOs, military, community groups, or private financiers—and to identify and align on the available labour landscape, such as soldier-labour, volunteers, farmers, or traditional labour groups.

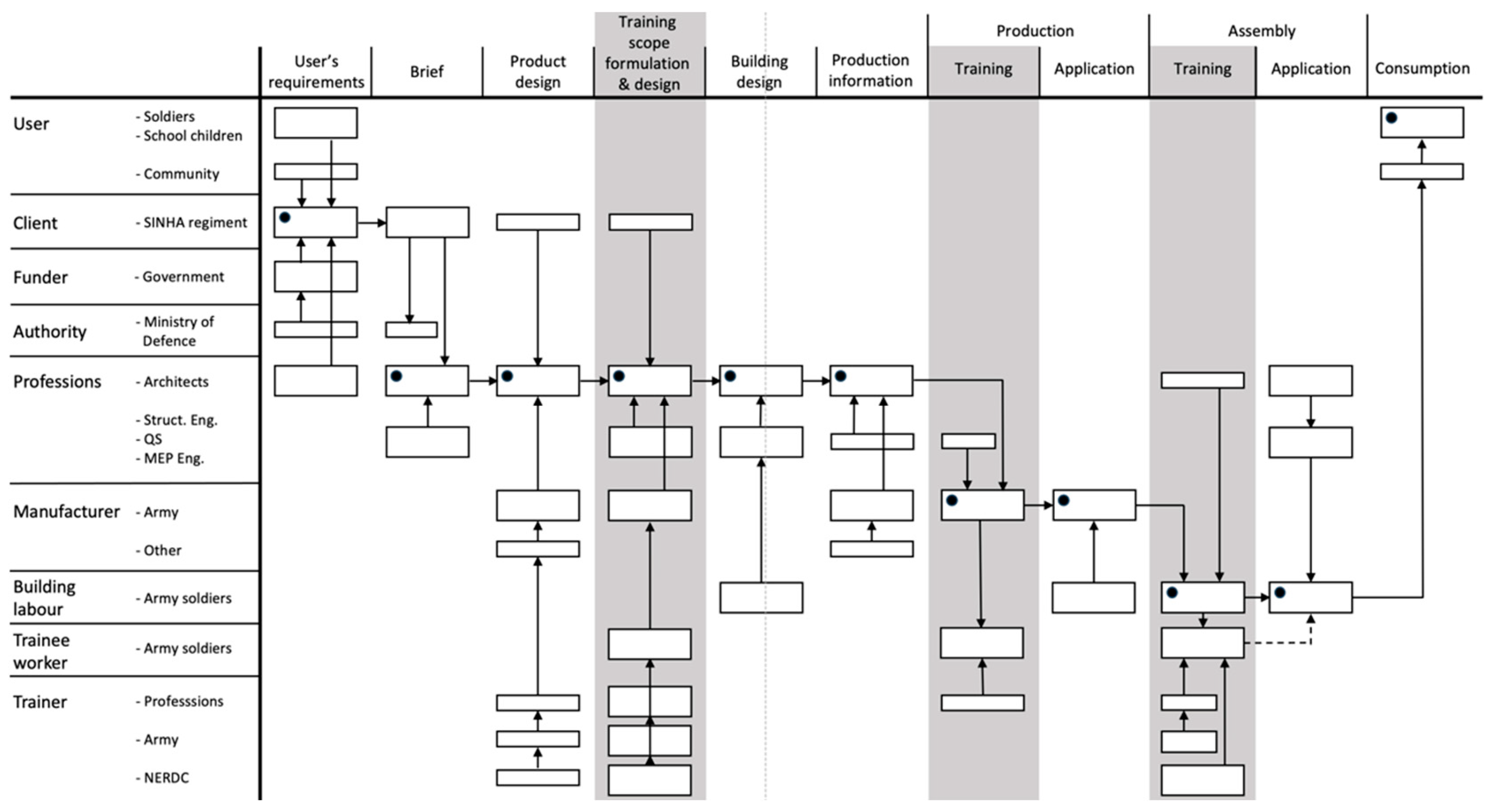

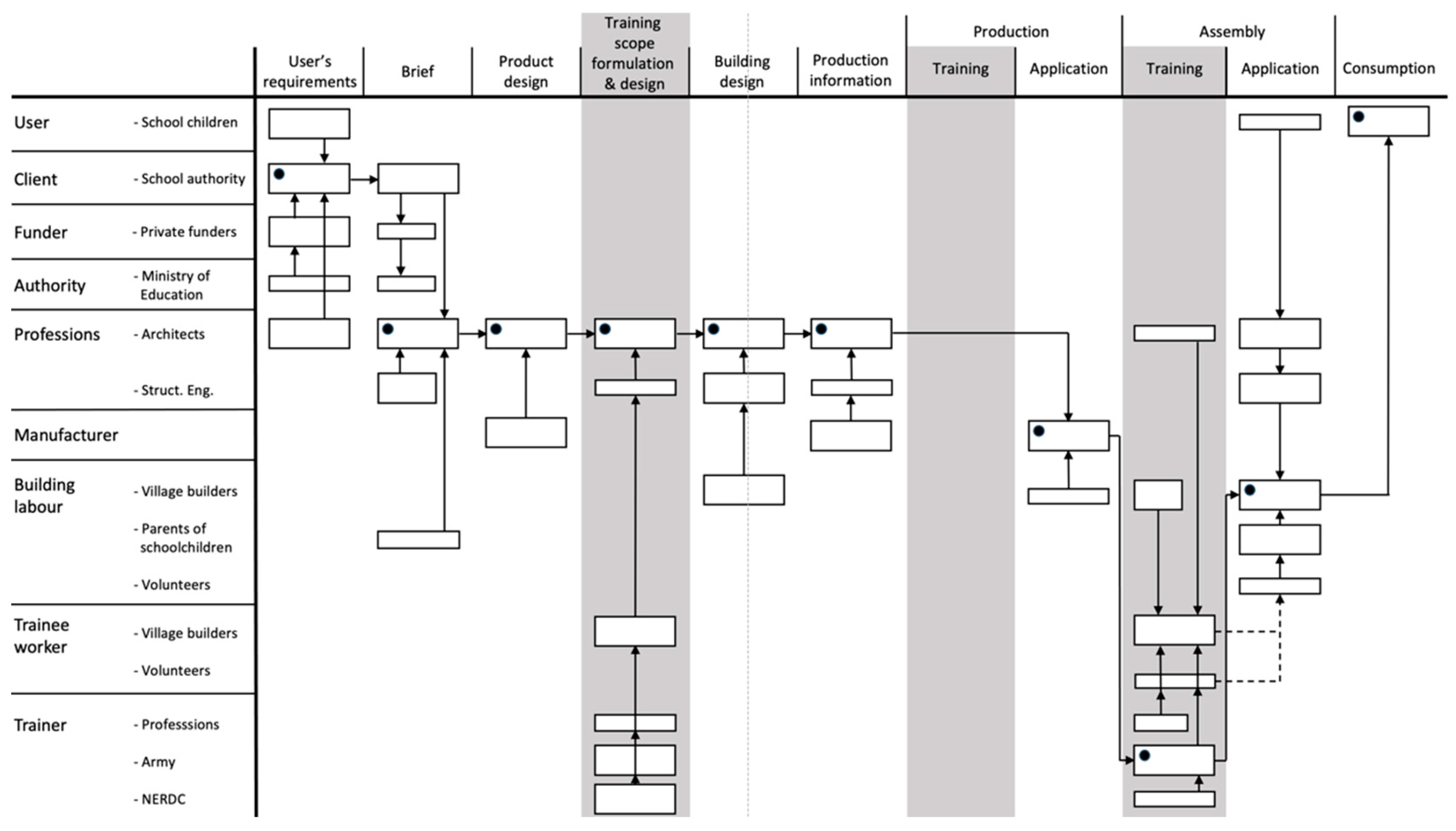

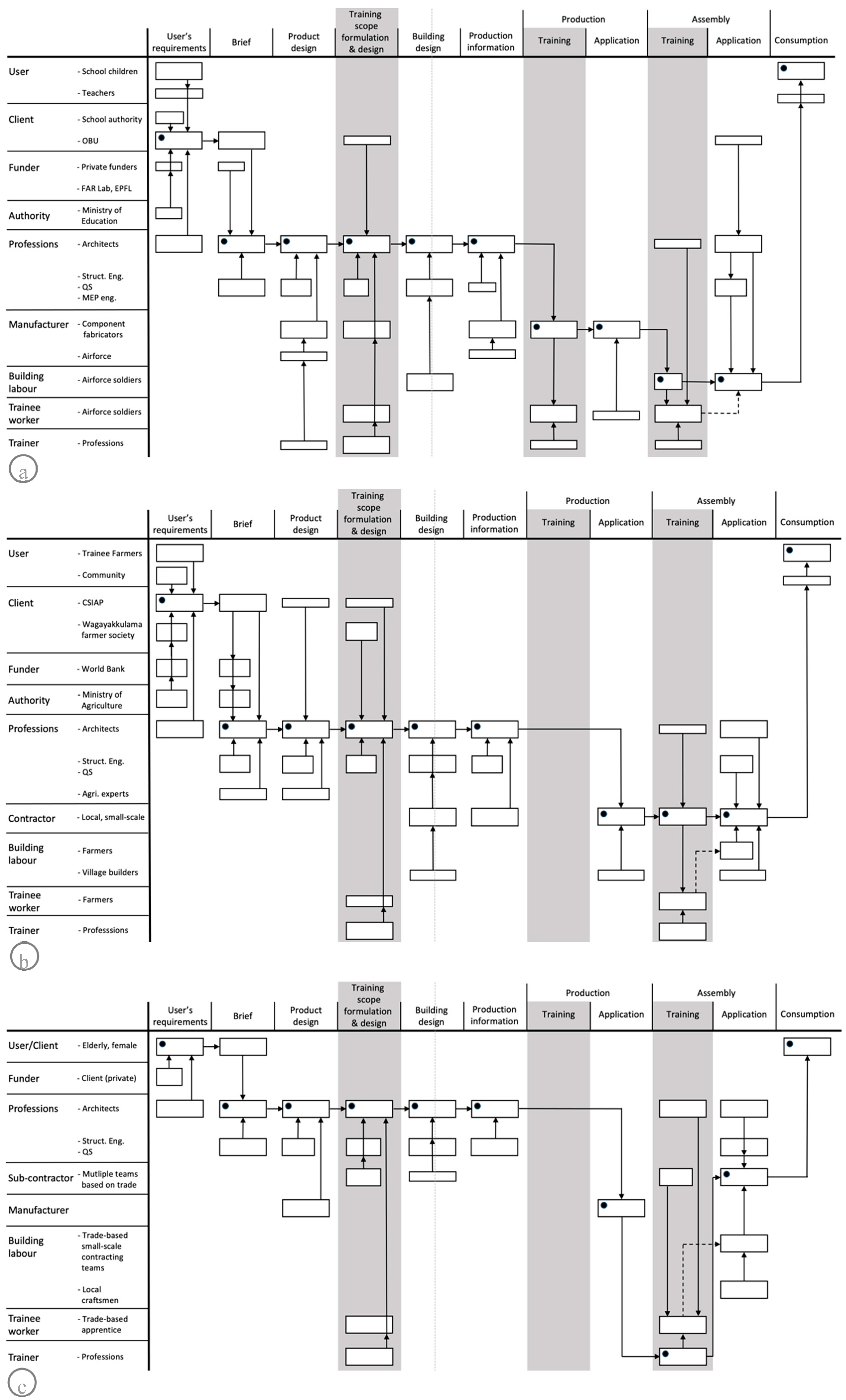

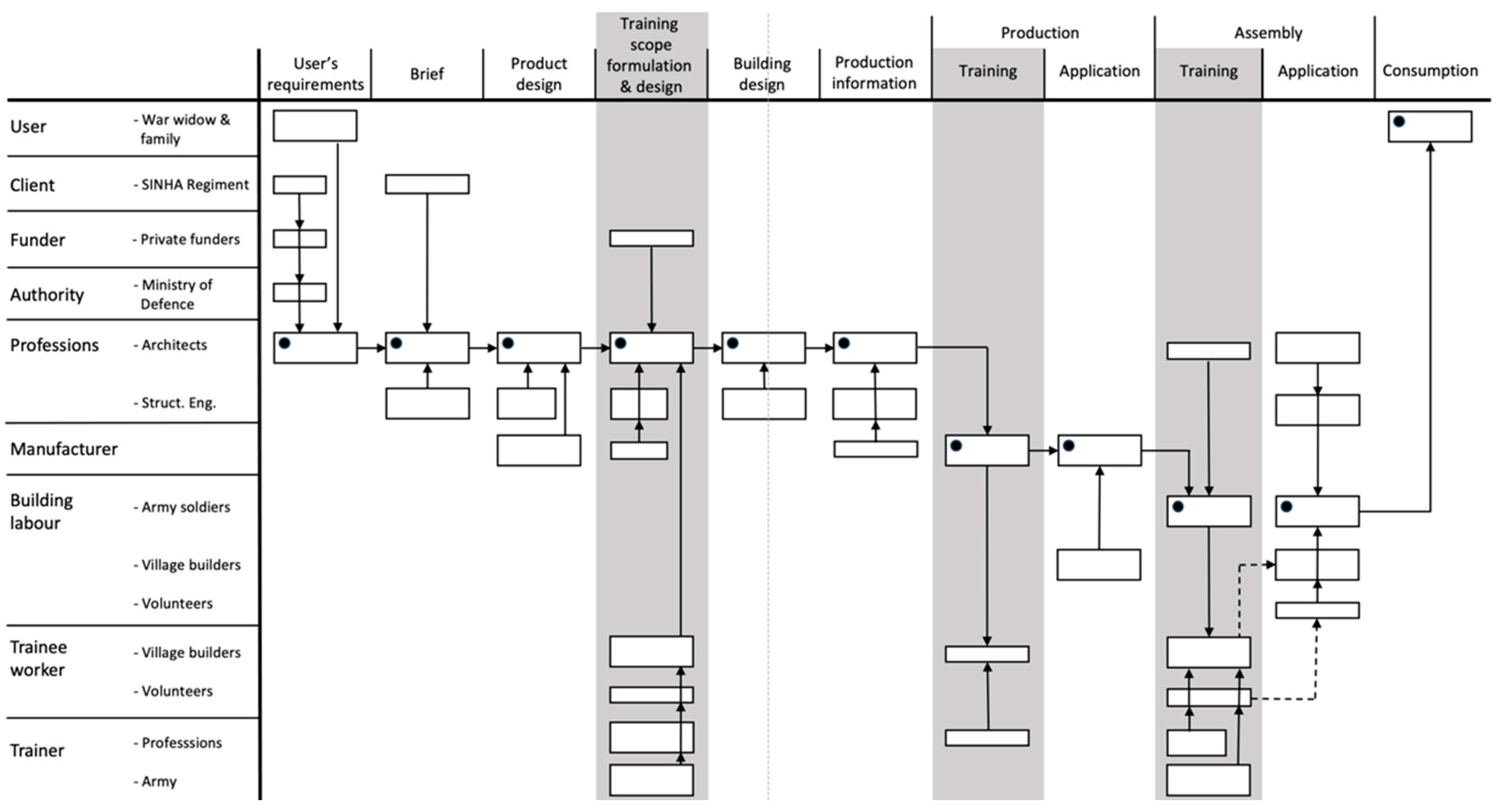

In this context, being political involves making necessary adjustments to standard procurement frameworks, which remain consistent across the case study projects (figures 11-14). These adjustments include: (1) creating a ‘training scope formulation and design stage’ that involves various stakeholders- either directly or indirectly- to define the technical and cultural aspects of specific labour conditions; (2) involving construction workers and trainees early in the project, as their understanding of the process and roles is crucial for effective training and the final outcome; (3) considering labour training—covering learning parameters, workmanship tolerances, and product results—as a design-related task or service, ideally managed by the architect, to integrate social, technical, and cultural design goals; and (4) officially assigning training responsibilities to contractors and manufacturers, either onsite or at the production yard.

Figure 11.

The Ambepussa library procurement approach involves bringing together all key political and professional stakeholders at the start. Training programmes for soldier labour are planned and designed early in collaboration with these stakeholders. The architects then lead the process as independent contributors.

Figure 11.

The Ambepussa library procurement approach involves bringing together all key political and professional stakeholders at the start. Training programmes for soldier labour are planned and designed early in collaboration with these stakeholders. The architects then lead the process as independent contributors.

Figure 12.

At Dewahuwa, training programmes for volunteers and village builders were conducted during the assembly stage, with input from state institutes such as the National Engineering Research and Design Centre (NERDC), which shared their rammed-earth building techniques with the project.

Figure 12.

At Dewahuwa, training programmes for volunteers and village builders were conducted during the assembly stage, with input from state institutes such as the National Engineering Research and Design Centre (NERDC), which shared their rammed-earth building techniques with the project.

Figure 13.

Procurement approaches for Kandy toilets (a), Farm field school (b), and Primrose house (c). The targeted trainees were, respectively, Airforce soldiers, farmers, and small-scale subcontracting crews.

Figure 13.

Procurement approaches for Kandy toilets (a), Farm field school (b), and Primrose house (c). The targeted trainees were, respectively, Airforce soldiers, farmers, and small-scale subcontracting crews.

Figure 14.

At Wakwella, soldiers previously trained through the Ambepussa library project served as trainers, imparting rammed-earth construction skills to local village builders. These cross-cultural exchanges between projects break down insularity and promote a shared building culture.

Figure 14.

At Wakwella, soldiers previously trained through the Ambepussa library project served as trainers, imparting rammed-earth construction skills to local village builders. These cross-cultural exchanges between projects break down insularity and promote a shared building culture.

7.2. Procurement as Political Negotiation

According to Frankfurt School theorists, the contemporary construction systems, procurement frameworks, contractor hierarchies, and donor logics tend to reduce human capacities to measurable outputs such as cost, time, and efficiency [

30]. The approach taken in these case studies contrasts with such logic by introducing non-instrumental values into procurement—training, collective authorship, and knowledge transfer. These acts represent what Herbert Marcuse called the “reappropriation of technical systems,” wherein dominant institutional structures are tactically redirected to produce alternative social relations [

39].

The pursued approach also aligns with Jürgen Habermas’s theory of communicative action, which offers insight into how procurement can serve as a framework for negotiated understanding. Early stakeholder engagement, shared decision-making on design, and project-based training initiatives establish “communicative rationality” [

40], enabling architecture to serve as a space where competing institutional and personal interests are mediated rather than imposed.

In this sense, the work embodies a critical theory perspective on architecture, focusing on altering production processes to redefine public agency in post-conflict contexts. Its political significance stems from its role in organising labour, procurement, and collective action, rather than from cultural symbolism. However, this does not mean that aesthetics are not important to this work. On the contrary, what we see, value, feel, and imagine about the world are shaped by how power is distributed and justified in architecture.

8. The Role of Aesthetics: Tectonics, Craft and the Politics of Recognition

Aesthetics is fundamentally non-neutral; the appearance, sensation, and experience of things influence who is seen, heard, recognised, included, or excluded. As Jacques Rancière explains, aesthetics has a political dimension because it controls the “distribution of the sensible” [

41]. To that end, the politics of aesthetics involves conflicts over who can appear, whose experiences are considered real, and whose voices are heard. It involves deciding who or what is made visible, valued, and acknowledged through aesthetic expressions, and who or what remains invisible [

41].

The main point is that aesthetic choices go beyond just style; they act as a means of power distribution. The aesthetics convey messages about the world and an individual’s place within it. To that end, the aesthetics of the case-study projects presented here can be seen as political because they make labour visible—materiality shows the creator’s hand rather than hiding it, while joints, beams, and connections are openly displayed without smooth concealment. This aesthetic recognises the worker as a co-author, turning construction into a social and educational act, and challenges the invisibility of labour in capitalist and militarised economies. The aesthetic goal here is not mere stylistic but involves a politics of recognition and dignity.

Today, in most mainstream building cultures—particularly those influenced by global capital—labour is deliberately concealed. Elements like smooth surfaces, curtain walls, prefabrication, and seamless finishes serve not just aesthetic purposes but act as means of erasure: they hide workers, anonymise labour, and create the illusion that buildings are finished products rather than processes. Marx referred to this as the fetishism of the commodity—the building appears as a polished, static object detached from the human and material effort behind it [

42]. Conversely, this work makes tectonics visible by revealing labour, highlighting craftsmanship to honour the agency and dignity of the creator.

8.1. Expression vs Suppression

To that end, this work engages with the politics of aesthetics through three main theoretical perspectives. First, Rancière’s aesthetics of recognition sees politics as the moment when those usually invisible become perceptible [

41]. When material textures, tool marks, construction joints, and assembly sequences are expressed rather than concealed, the building acknowledges the worker as a subject, rather than a background function. Second, if construction is viewed as a space of collective learning, negotiation, apprenticeship, and community-building, then the tectonic expression becomes a public record of this social production. Third, craft represents local, context-specific intelligence—knowledge that is adaptable and rooted in experience—and emphasising craft legitimises forms of knowledge outside formal expertise.

Choosing between expressive and concealed tectonics is, therefore, both constructional and political. The political choice is especially significant in postcolonial construction economies, where labour is plentiful but undervalued, workers are vital but unrecognised, and architecture is often imported rather than produced locally. When a building uses local earth rather than imported material, trains workers rather than outsourcing prefabrication, and reveals its construction rather than hiding it, it reshapes power dynamics. It proclaims that workers’ bodies and knowledge matter, and that they have a stake in shaping this space.

In this context, tectonics is not merely style, and craft is not just nostalgia. Instead, they serve as constructive responses to navigate social complexity in building and as political tools to expose relations, affirm dignity, and reassign authorship of space.

9. Beyond Regionalism: Towards a Critical Practice

In comparison with the celebrated proponents of architectural regionalism, notably Geoffrey Bawa in the context of architectural production in Sri Lanka, the work highlighted here demonstrates a divergent articulation of how labour and craft are framed. While both approaches are deeply indebted to the knowledge of craftsmen and local construction cultures, they differ markedly in how labour is produced and becomes visible, valued, and meaningful within the final work.

In regionalist architecture, for example, craft is central to producing an atmosphere of refinement, cultural continuity, and environmental responsiveness [

43]. Yet, the traces of labour are aesthetically absorbed into the seamlessness of carefully mediated spatial experience [

44]. The building appears resolved and timeless, an effect supported by what Walter Benjamin describes as the bourgeois aesthetic of completion, in which the bodily work of making is rendered invisible [

45].

This work, by contrast, approaches craft and tectonics as political instruments for recognition and empowerment. In all the projects evaluated in the study, construction is treated as a pedagogical process; joints, bonds, and assembly sequences remain legible rather than concealed. This aligns with Rancière’s [

41] argument that politics begins when the invisible becomes perceptible: here, labour is not erased but acknowledged. Construction becomes a shared, situated knowledge practice—what James C. Scott [

46] terms

metis—grounded in the intelligence of embodied skill. The building is not merely a finished object; it becomes a record of social relations, echoing Lefebvre’s [

3] conception of space as socially produced but reframing that observation within a constructional paradigm.

Thus, if regionalist architecture offers beauty as cultural reassurance, this work proposes beauty as the dignity of shared making. The shift is not stylistic but political: from architecture as representation to architecture as collective capacity-building.

10. Outlining a Normative Framework

The preceding analysis demonstrates that the political aspect of architecture in post-conflict and resource-limited contexts cannot be understood solely through symbolic expression. Instead, it must be examined via the organisation of production systems. Across the six case studies, recurring operational mechanisms emerged that consistently influenced labour agency, knowledge transfer, material decision-making, and institutional negotiation (

Table 1). These mechanisms are not accidental; they appear wherever architectural production is used to reorganise relationships between builders, communities, funders, and public institutions.

Treating construction as pedagogy fosters forms of collective authorship, as seen in training initiatives at Ambepussa, Dewahuwa, Kandy, and Thirappane. Process-based procurement shows how power can be negotiated tactically rather than resisted, especially in collaborations with the military, donor agencies, and local government. Material choices serve as political decisions when they reconfigure supply chains, reduce reliance on imported technology, and support micro-industry, as illustrated by the sanitary blocks and housing prototypes. Lastly, tectonic strategies create aesthetic conditions that make labour visible, recognised, and documented as a social contribution.

From these patterns, eight normative principles have been developed. They are not abstract theories but general lessons drawn from empirical evidence. The normative framework, therefore, articulates what projects have already demonstrated in practice: small-to-medium-scale architectural interventions can foster civic infrastructure by reorganising labour, redistributing knowledge, and renegotiating institutional power. In this way, the framework formalises a practice-based method, providing strategic guidance for architectural work in developing economies.

-

(1)

Architecture as the production of the social

Space is not merely a neutral container, and architecture is intertwined with social relations shaped by labour, institutional frameworks, and ideological influences. Buildings become political when they reflect the visible results of social negotiations, training processes, and material decisions.

-

(2)

Knowledge as shifting postcolonial political authority

Architecture can be seen as a way to decentralise colonial influences on professional authority, aligning with Chatterjee’s [

34] distinction between civil society and political society. Knowledge can be shifted from professional architectural labour to socially embedded construction training programs, thereby redefining who is empowered to build and design.

-

(3)

Engagement with power tactically

Professionals can manage power dynamics by positioning themselves as politically neutral authorities and engaging all stakeholders early in the building procurement process. This approach emphasises shared values and mutual gains, helps clarify personal motivations, fosters collaborative training, and promotes shared project ownership. It fosters adaptive knowledge through practical experience rather than external imposition, and redirects institutional resources towards civic objectives.

-

(4)

Building as social pedagogy

Construction sites can act as learning environments where building tasks are ‘designed’ for skill development and the reconstruction of identity. This idea aligns with Paulo Freire’s [

47] concept of praxis: transforming the world through reflective action. As a result, construction becomes a collective, context-specific activity grounded in both learned and embodied skills at the site.

-

(5)

Materiality as temporal politics

The emphasis on locally sourced, energy-efficient, and durable materials signals a move away from development models based on imported systems and short-lived designs. Architecture is seen as a long-term investment in the public realm rather than a fleeting display of capital. This perspective challenges the developmental narrative that links progress with novelty, speed, and verticality. Instead, it champions resilience, continuity, and the ability to repair. Here, materiality is driven by economic and ecological considerations, not aesthetics. It resists the dependency-producing tendencies of global supply chains and aligns instead with place-specific resource ecologies.

-

(6)

Spatial justice through typological response

Increasingly, project types such as libraries, schools, training centres, and community infrastructure are being neglected in Sri Lanka’s contemporary architectural discourse, which has oscillated between state-led monumentalism and private-market individualism. If spatial justice signifies fair access to spatial resources for all populations, then efforts should be made to reintroduce architectural care where it has been notably absent—particularly in the everyday environments of rural and peri-urban communities—by responding thoughtfully to climate, providing generous spatial design, and maintaining formal dignity. This can challenge the notion that high-quality architecture is exclusive to elite clients.

-

(7)

Tectonics as both an act of constructing and revealing

Expressing material textures, tool marks, joints, and assembly sequences positions the worker as an active participant rather than merely a background element. Viewing construction as a collective learning process and community-building transforms tectonic expression into a public record of social production, challenging existing power structures. It emphasises the importance of workers’ bodies and knowledge, giving them a role in shaping space. Tectonics thus addresses the social complexity of construction and functions as a political tool to reveal relationships, uphold dignity, and reassign authorship.

-

(8)

Aesthetics as a process of becoming

In the context studied, architecture is seen more as a means of collective capacity-building than mere representation and cultural aestheticisation. It involves expressing labour through form rather than forcing it into naturalisation within the environment. Craft is valued for transmitting skills and fostering agency, not merely as a source of refinement and beauty. Tectonics is demonstrated explicitly, not concealed or smoothed. Aesthetics are viewed as an ongoing process of becoming, rather than simply resolving a stylistic trope.

11. Limitations

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations. First, the practitioner-researcher position provides unique insight into project processes but introduces potential bias. Interpretations are shaped by the author’s involvement in the projects, and external verification is limited. Nevertheless, references to published literature on the projects and reflective practices on practitioner-researcher approach [

48] and have been used to mitigate researcher bias.

Second, the study relies primarily on qualitative sources without systematic quantitative measurements of impacts such as skill acquisition, socio-economic change, or long-term community outcomes. Claims regarding empowerment or knowledge transfer, therefore, remain interpretive.

Finally, many of the projects are recent, and long-term post-occupancy data are limited. Outcomes related to training, identity reconstruction, and institutional change require longitudinal study to assess their durability. Nevertheless, the reflective analysis method used within the practitioner-researcher framework offers a fitting approach to evaluate the key objective of this study: to understand architecture as a negotiated and political process.

12. Conclusions

Transitioning from a historical critique to an empirical case study, this practice-based research investigates how architecture can enable political agency in post-conflict contexts. It identifies key mechanisms — labour visibility, pedagogical construction, process-based procurement, tactical institutional negotiation, and material autonomy — and consolidates them into an eight-point normative framework. The key conclusion is that architectural politics should shift from emphasising representational aesthetics to focusing on production systems.

By viewing building as social pedagogy and procurement as political negotiation, architecture can reshape knowledge, dignity, and power in developing economies. In societies emerging from conflict, where development often reinforces existing power structures rather than fostering equality, this approach contributes to architecture serving as a means to redistribute skills, authorship, and a sense of belonging; and buildings acting as frameworks of labour, identity, and civic participation. The projects reviewed here illustrate that architectural efforts in the global south should emphasise redefining architecture as a socially rooted, politically engaged process rather than following stylistic trends. Change should unfold gradually through collaboration, care and strategic intervention.

References

- Eisenman, P. Post-Functionalism; Oppositions, 1976; Volume 6, pp. 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cuff, D. Architecture: The Story of Practice; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Nicholson-Smith, D., Translator; Blackwell: Cambridge, MA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The Right to the City. New Left Review 2008, 53, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, L. Architecture, power and national identity; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Adorno, T. Aesthetics and Politics; Verso: London, New York, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pathiraja, M.; Tombesi, P. Towards a more “robust” technology? Capacity building in post-tsunami Sri Lanka. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal 2009, 18, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, L. B. On the Art of Building in Ten Books; Rykwert, J.; Leach, N.; Tavernor, R., Translators; MIT Press, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Carpo, Mario. The Alphabet and the Algorithm; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jarzombek, M. Architecture Constructed:Notes on a Discipline; Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Deamer, P. The Architect as Worker: Immaterial Labor, the Creative Class, and the Politics of Design; Bloomsbury: London, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Frampton, K. Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance. In The Anti-Aesthetic; Foster, H., Ed.; Bay Press, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Frampton, K. Prospects for a Critical Regionalism. Perspecta 1987, 20, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggener, K. Placing Resistance: A Critique of Critical Regionalism. Journal of Architectural Education 1992, 45, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksamija, A. Research Methods for the Architectural Profession; Routledge, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, C. Real World Research: A Resource for Social Scientists and Practitioner-Researchers, 2nd ed.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Perera, I.; Spencer, J. ‘Beautification, Governance, and Spectacle in Post-war Colombo’. In Controlling the Capital: Political Dom- inance in the Urbanizing World; Goodfellow, T., Jackman, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2023; pp. 203–33. [Google Scholar]

- Venugopal, R. Nationalism, Development and Ethnic Conflict in Sri Lanka; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kishnani, N. Community Library, Ambepussa’ in Ecopuncture: Transforming Architecture and Urbanism in Asia; BCI Media Group: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zutter, M. Community Library, Ambepussa, Sri Lanka’, in Arketipo, March 2020; New Business Media, Italy, 2022; pp. 40–53. [Google Scholar]

- Leutenegger, M. Designing with plenty of tolerances. In Fourth Holcim Awards; Schwarz, E., Ed.; Holcim Sustainable Construction Press, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dawswatte, C. ‘Robust Architecture Workshop: Ambepussa Community Library’. In A+U (Architecture and Urbanism); Yoshida, N, Ed.; A+U Publishing Co. Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 2019; Vol 590, pp. 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Tombesi, P. ‘Two Works’. In Casabella, ed. Francesco Dal Co; Mondadori: Milano, 2023; Volume Issue 951/no. 11, pp. 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, C. ‘Library, Boralukanda Primary’. In FuturArc, ed. N. Kishnani; BCI Asia construction information pte ltd, Singapore, 2019; Vol 64, pp. 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Perroud, S. Toilets serve as concrete examples for industrial restructuring. EPFL. 23 September 2023. Available online: https://actu.epfl.ch/news/toilets-serve-as-concrete-examples-for-industrial-/.

- Lim, C.; Mundakir, L. ‘FuturArc Interview: Milinda Pathiraja, PhD’. In FuturArc, ed. C. Lim; BCI Asia construction information pte ltd, Singapore, 2024; Vol. 84, pp. 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- De Silva, S. ‘Farmer Field School Thirappane: Robust Architecture Workshop’. In The Architectural Review; Mollard, M., Ed.; 1514; Emap: London, 2024; pp. 100–108. [Google Scholar]

- Pathiraja, M.; Tombesi, P. Circularity by stock in Sri Lanka: Economic necessity meets urban fabric renovation. Frontiers in Built Environment 2023, 8, 1098389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunewardena, N. ‘Thirasara Nimawumaka Asiriya’. In Vastu; Sri Lanka Institute of Architects (SLIA): Colombo, 2016; Vol 14, pp. 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Adorno, T. W.; Horkheimer, M. Dialectic of Enlightenment; Social Studies Association, Inc: New York, 1944. [Google Scholar]

-

New Perspectives on Construction in Developing Countries, 1st ed.; Ofori, G., Ed.; Routledge, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathiraja, M. Robustness as a design strategy: Navigating the social complexities of technology in building production. Buildings 2025, 15, 3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombesi, P. ‘Robust Architecture Workshop (RAW)’. In AA (Architecture Australia); Butler, K, Ed.; Architecture Media Pty Ltd: South Melbourne, Australia, 2020; pp. 102–106. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, P. The politics of the governed: Reflections on popular politics in most of the world; Columbia University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, K.; Engels, F. The German Ideology; International Publishers, 1846. [Google Scholar]

- Abeysinghe, S.; Weerawardane, B.; Randeniya, I.; Sirinivasan, A.; Arangala, M.; Hingert, J. Backwards in blacklisting: Gaps in Sri Lanka’s procurement framework enable corruption [Research Brief]. In Verité Research; 2023; Available online: https://www.veriteresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/BackwardsinBlacklisting_ResearchBrief_Nov2023.pdf.

- Hadiwattege, C.; De Silva, L.; Pathirage, C. Corruption in Sri Lankan Construction Industry [Paper presentation]. 18th CIB World Building Congress, Salford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Turin, D. A. What do we mean by building? Habitat International 1980, 5, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcuse, H. One-Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society; Beacon Press, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. The theory of communicative action: Reason and the rationalization of society; Beacon Press: Boston, 1984; Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Rancière, J. The Politics of Aesthetics. The Distribution of the Sensible; Continuum: New York/London, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, K. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume I; Engels, Friedrich; Moore, Samuel; Aveling, Edward, Translators; Penguin Classics, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, D. Geoffrey Bawa: The Complete Works; Thames & Hudson: London, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pieris, A. Architecture and Nationalism in Sri Lanka: The Trouser Under the Cloth, 1st ed.; Routledge, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, W. The work of art in the age of its mechanical reproducibility and other writings on media. In The work of art in the age of its mechanical reproducibility and other writings on media; Jennings, M. W., Doherty, B., Levin, T. Y., Eds.; Belknap Press: Cambridge, MA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J. C. Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed; Yale University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed.; Seabury Press: New York, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- McNiff, J. Action Research: Principles and Practice, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, 2013. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).