1. Introduction

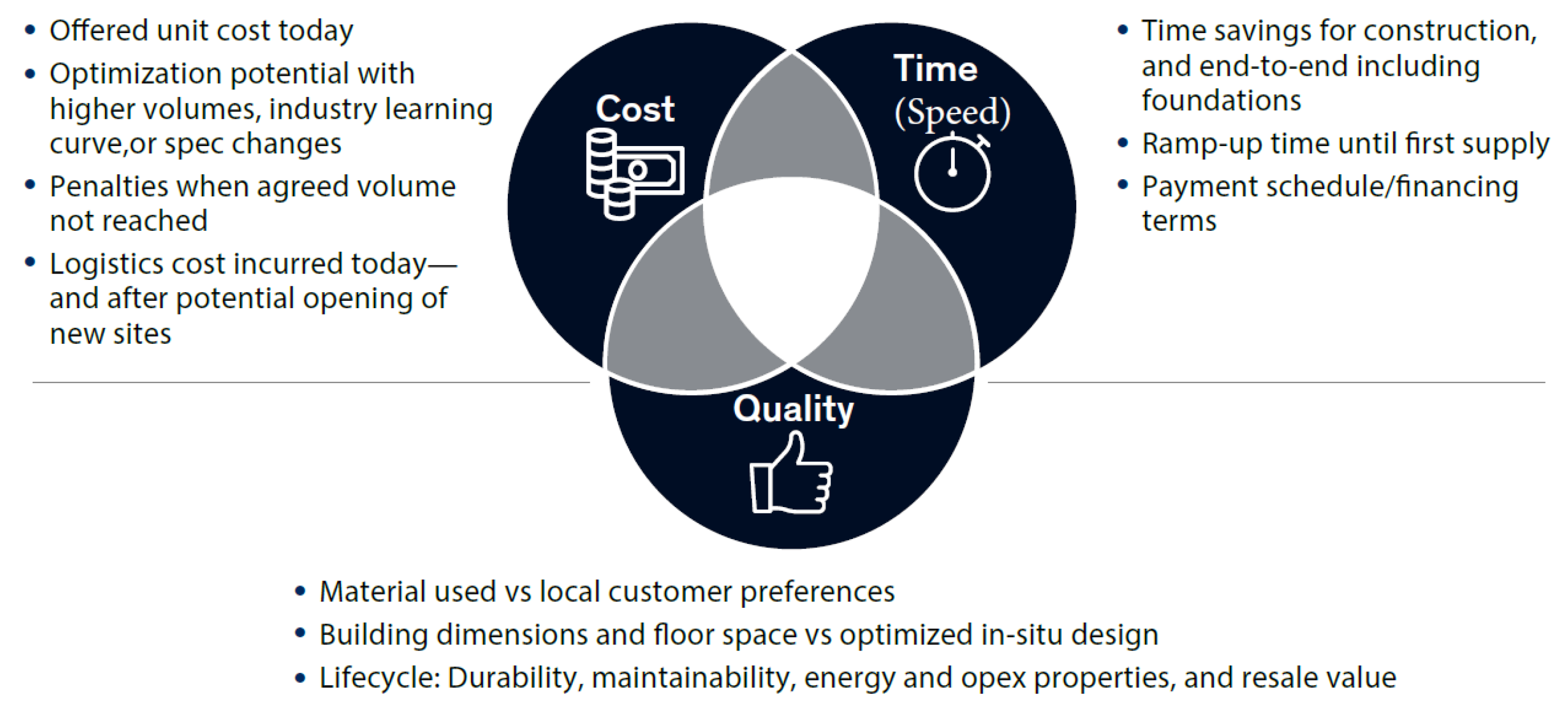

The production of permanent post-disaster housing necessitates rapid and high-quality solutions, with façade systems playing a critical role in determining overall construction cost, quality, production time, and efficiency. This study aims to address a significant gap in the literature by focusing on modular façade systems within the context of the 2023 earthquakes in Türkiye, while exploring sustainable post-disaster reconstruction solutions. Observations from the delayed delivery of permanent housing in Türkiye, compared to the reconstruction processes in countries that experienced disasters of similar magnitude, suggest that prefabricated façade systems can offer substantial contributions to the timely provision of post-disaster housing. While conventional methods often fall short in meeting demands related to speed, quality, and cost, prefabricated and modular systems shift a significant portion of the construction process to a controlled factory environment. This transition leads to cost reductions, shortened production times, enhanced quality, and reductions in material waste and labor inefficiencies [

1]. Given that façade construction is among one of the most time-consuming and labor-intensive stages of construction projects, this study strategically focuses on this component. Modular panel façade systems allow for faster enclosure of buildings, earlier initiation of interior works, and increased structural flexibility. The research investigates whether these systems deliver measurable advantages in terms of speed, cost, and quality, based on the perspectives of construction industry stakeholders (

Figure 1).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Post-Disaster Housing Reconstruction

Post-disaster housing reconstruction is widely acknowledged as a complex, multi-dimensional process that goes beyond the physical rebuilding of structures. It also encompasses social recovery, economic revitalization, and the establishment of long-term resilience strategies [

2]. In the aftermath of major earthquakes, governments face the dual challenge of delivering housing both rapidly and responsibly ensuring structural safety, affordability, and community acceptance.

Comparative analyses of reconstruction efforts following earthquakes in Chile (2010), Japan (2011), and China (2008) highlight the critical role of governance, institutional capacity, and construction technologies in shaping recovery outcomes [

3,

4]. In Japan, for instance, the adoption of industrialized construction systems contributed to the relatively swift delivery of permanent housing, although high costs and demographic shifts presented additional challenges. China, in contrast, prioritized speed through standardized large-scale housing models, often at the expense of context-specific solutions.

The 2023 Kahramanmaraş-centered earthquakes in Türkiye resulted in approximately 518,000 homes becoming uninhabitable and damage to more than 2 million residential units [

5]. Government announcements projected the delivery of 319,000 new homes within the first year and 650,000 in total. However, with only 46,000 units completed by the end of the first year, the reconstruction process has significantly lagged behind initial targets [

6]. This shortfall underscores the urgent need for more efficient and scalable construction solutions.

Prefabricated modular systems are increasingly viewed as a viable approach to meeting these challenges. Lessons from past earthquakes in Chile, Japan, and China demonstrate that industrialized construction methods can reduce reconstruction timelines while maintaining structural quality [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Following the 9.1 Mw Tōhoku Earthquake and Tsunami in 2011 one of the strongest earthquakes in Japan’s history 122,000 buildings were completely destroyed, and 734,000 sustained partial damage [

8]. Coordinated efforts between central and local authorities enabled over 90% of displaced residents to be rehoused by December 2020 [

9].

At the time, Japan’s housing sector had already embraced prefabrication, with 12–16% of new residential construction utilizing prefabricated methods between 2005 and 2016 [

10]. By contrast, prefabrication in Türkiye’s construction sector remains underutilized, accounting for only 2–3% of total production [

11]. This disparity suggests a significant opportunity to adopt prefabricated modular systems more broadly within Türkiye’s post-disaster housing strategies.

2.2. Prefabrication and Modular Construction

Prefabrication involves manufacturing building components in a controlled factory environment, which are then transported and assembled on-site. Modular construction represents a more advanced application of this approach, wherein volumetric or panelized modules are produced with a high degree of completion. Both methods enable parallel processing between off-site manufacturing and on-site activities, leading to significant time savings and enhanced efficiency.

Numerous studies have shown that prefabrication can reduce construction timelines by 20–50%, improve cost predictability, and strengthen quality control through standardized production processes [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. In disaster recovery contexts, these advantages become even more critical, as prefabricated systems allow for accelerated project delivery, reduced on-site labor demands, and improved occupational safety [

14].

Façade systems—such as precast concrete panels, unitized curtain walls, sandwich panels, and composite claddings—play a vital role in this context. These elements often account for a substantial portion of both construction costs and project duration. Advances in materials, including glass fiber reinforced concrete (GFRC) and high-performance composites, now offer a wide range of options tailored to diverse requirements in terms of time, cost, aesthetics, and durability. The growing demand for prefabricated modular façades is driven by their compatibility with mass production, rapid manufacturing, aesthetic versatility, resistance to environmental factors, and ease of installation [

15].

Despite these benefits, several challenges hinder widespread adoption. These include high initial investment costs, design processes not aligned with prefabricated systems, logistical constraints, limited crane accessibility, and regulatory gaps [

16]. In Türkiye, the integration of prefabrication into the construction sector remains limited. However, the need to scale up the use of prefabricated modular components has become increasingly apparent in the aftermath of the 2023 earthquakes [

17].

A prevailing perception in the industry is that prefabrication limits architectural creativity. Yet, particularly in concrete-based prefabricated façade panels, a wide range of colors, patterns, and surface textures are available. These systems enable the creation of complex forms that are often unattainable through conventional on-site construction methods [

18].

2.3. Façade Systems as a Critical Construction Interface

Façades constitute a substantial share of total building costs ranging from 15% to 40% depending on building type and specification—and often represent a critical path activity within construction schedules [

19]. Delays in façade installation can significantly affect project completion times, particularly in multi-storey residential buildings.

Prefabricated façade systems, including precast concrete panels, lightweight steel assemblies, and timber-based solutions such as cross-laminated timber (CLT), have been increasingly adopted in international projects to accelerate construction and improve performance consistency. Despite this, façade-level prefabrication remains underexplored in post-disaster housing research, particularly in contexts where full modular construction may face practical constraints.

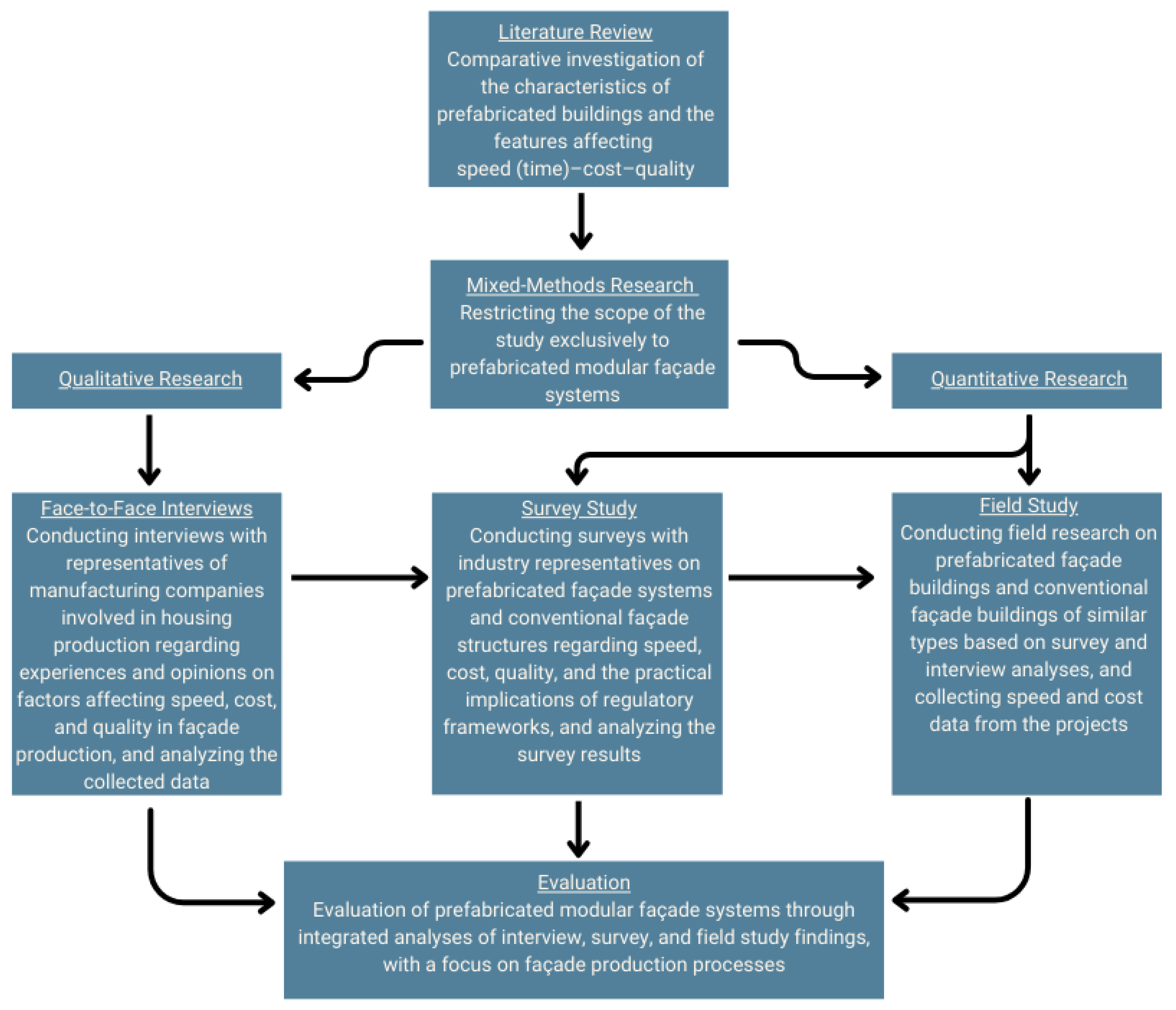

3. Research Methodology

This study evaluates the applicability of prefabricated modular façade systems in post-disaster permanent housing production in Türkiye, based on insights gathered from sector stakeholders and construction professionals. A mixed-methods research design was employed, integrating both qualitative and quantitative approaches (

Figure 2).

Initially, a literature review was conducted to examine international post-disaster reconstruction case studies. This was followed by semi-structured interviews with 15 anonymous stakeholders in the construction sector, including company owners and senior representatives.

Subsequently, a quantitative survey was administered to a sample of 366 professionals including architects, civil engineers, and construction technicians using an anonymous, structured questionnaire. The survey assessed perceptions of prefabricated versus conventional construction methods with respect to time, cost, and quality dimensions. The research followed Creswell’s exploratory sequential design model, wherein qualitative findings informed the development of the quantitative instrument, allowing for empirical validation across a broader sample.

Interview data were analyzed using thematic analysis [

20] and processed via MaxQDA and TurboScribe AI transcription software. The survey instrument included 18 items measured on a three-point Likert scale (“Agree”, “Neutral”, “Disagree”), evaluating the perceived advantages and limitations of prefabrication across cost, time, quality, and regulatory dimensions.

Quantitative data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 27.0. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participant responses, and chi-square (χ²) tests were applied to examine associations between categorical variables. The sample size (n = 366) was determined based on a 95% confidence level and a margin of error of ±5.1%. The study population was defined as white-collar and technical personnel employed in Türkiye’s construction sector. Subgroup analyses were performed across different demographic and professional categories within the sample.

All ethical protocols were strictly observed, and participant responses were fully anonymized to ensure confidentiality and data protection.

4. Results

4.1. Findings from Semi-Structured Interviews

Semi-structured interviews provided rich qualitative insights into the applicability of prefabricated modular façade systems in Türkiye’s post-disaster housing context. Thematic analysis revealed four principal themes: time efficiency, cost implications, quality performance, and regulatory and governmental frameworks. Overall, participants expressed cautious optimism about modular façades. Time savings were consistently identified as the most prominent benefit, with prefabricated panels enabling enclosure of buildings within a few weeks, thus alleviating critical bottlenecks at construction sites.

Cost assessments varied among participants; however, many indicated that overall project expenditures benefited from shortened project durations, decreased overhead, minimized weather-related delays, and reduced material waste due to factory-controlled environments. In terms of quality, participants noted improvements in thermal and moisture performance. Key challenges included regulatory ambiguity, lengthy permit processes, and limited local manufacturing capacity. The thematic analysis yielded 15 codes across the four major themes (

Table 1).

4.2. Survey Results

Following the qualitative phase, a structured questionnaire comprising 14 opinion-based Likert-scale items and 4 demographic items was developed. The target population consisted of white-collar and technical personnel (white helmets) within the Turkish construction sector. A purposive sampling strategy was applied, focusing on professionals such as architects, engineers, draftspersons, and technicians. The estimated professional population includes approximately 230,000 architects and engineers operating nationally. The sample size was calculated using a 95% confidence level and ±5.1% margin of error, resulting in a minimum required sample of 360 participants. The survey was completed by n = 366 respondents, thus satisfying statistical power requirements.

Survey results generally supported the advantages of prefabricated façade systems (

Table 2).

The analysis employed descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) and chi-square (χ²) tests to assess associations between participant subgroups and their responses. Subgroup comparisons were conducted based on profession, education level, role in the construction process, and professional experience (

Table 3).

4.3. Key Findings

Field analyses demonstrate that projects employing prefabricated façade systems achieved measurable reductions in façade installation time compared to conventional methods. While initial material costs were comparable, prefabricated systems exhibited advantages in labor efficiency and scheduling reliability.

A statistically significant difference was observed in perceptions of construction duration: participants from architectural disciplines (architects, technicians, draftspersons) were more likely than engineers/technicians to agree that prefabrication shortens overall project duration (82.3% vs. 70%; χ², p < 0.05).

No significant differences were found among participants based on education level or construction role regarding their attitudes toward prefabrication.

Participants with less than 5 years of experience were more likely to view prefabrication as cost-reducing compared to more experienced professionals. Among early-career respondents, 27.2% expressed uncertainty or disagreement, compared to 47.7% among those with >5 years of experience (χ², p < 0.05).

Conversely, those with more than 6 years of experience showed a higher tendency to agree that prefabrication could improve building longevity and reduce lifecycle costs (72.3% vs. 62.6%; χ², p < 0.05).

A notable difference was observed in perceptions of adaptability: 72.5% of less-experienced participants agreed that prefabricated façades offer more flexible and adaptive solutions, compared to 60% among more experienced respondents (χ², p < 0.05).

On regulatory oversight, 64% of participants agreed that prefabrication allows for more efficient quality control in factory settings. Agreement was higher among more experienced respondents (69.2%) than among less experienced professionals (57.3%) (χ², p < 0.05)

5. Discussion

The findings align with international literature emphasizing the role of industrialized construction in enhancing post-disaster recovery capacity. Importantly, the study demonstrates that façade-level prefabrication can serve as a pragmatic intermediate strategy, bridging the gap between fully conventional and fully modular construction systems. The findings align the urgency of post-earthquake housing demand with the key advantages of modular façade systems, reinforcing their applicability in disaster recovery contexts.

Speed and Scheduling Efficiency: Prefabrication of façade panels enables concurrent execution of factory production and on-site operations, significantly reducing the overall project timeline. When supported by proper architectural and structural detailing, prefabrication processes can be initiated even during the permitting phase. Unlike on-site construction, factory-based production is insulated from weather-related disruptions such as rainfall, storms, or freezing temperatures, which frequently delay site activities. Apart from minimal time required for on-site installation, prefabricated façade systems maintain uninterrupted production regardless of seasonal or environmental conditions [

13].

Cost Efficiency: While mobilization costs may be higher for small-scale projects, economies of scale can be realized in large, standardized developments. Although unit material costs may not differ substantially between prefabricated and conventional methods, time savings from industrialized production can offset overall expenditures [

21]. Additionally, using mass-produced modular panels can lead to further cost reductions on building envelopes.

Quality Control: Factory-controlled environments enhance construction performance and workmanship. Up to 80% of the labor activities in a prefabricated modular project can be relocated off-site [

1], allowing for streamlined quality assurance and tighter control of material waste.

Architectural Design Flexibility: Although Gropius (1911) acknowledged that prefabrication could impose constraints on design freedom, he emphasized the architect’s responsibility to creatively address such limitations [

22]. Contemporary façade systems allow for substantial aesthetic variety, mitigating concerns over monotony and repetitive appearance. Advances in formwork, pigmentation, surface textures, and modular customization further support design adaptability.

Policy and Regulation: The most significant barrier remains regulatory uncertainty. A clear legislative framework, accompanied by certification systems, pilot implementation programs, and financial incentives, is essential to foster wider adoption and reduce market hesitation.

Social Impact: The rapid provision of permanent housing shortens the duration spent in temporary shelters, thereby accelerating social recovery and improving post-disaster community resilience.

6. Conclusions and Implications

The study concludes that prefabricated modular façade systems are a feasible and effective tool for accelerating permanent housing delivery in post-earthquake contexts. Policymakers should consider targeted incentives, regulatory adaptations, and investment in local production capacity to support broader adoption. Prefabricated modular façade systems offer a viable solution for delivering fast, cost-effective, and high-quality permanent housing in post-disaster reconstruction scenarios in Türkiye. Sector stakeholders and construction professionals generally express favorable views regarding their applicability. However, scaling this approach requires the development of a comprehensive enabling environment, including:

Clear and consistent regulatory frameworks,

Certified design and construction protocols,

Capacity-building programs for manufacturers and contractors,

Careful detailing of seismic connections, and

Workforce training initiatives tailored to modular systems.

Integrating modular façades into a holistic reconstruction strategy can contribute to the development of more resilient, durable, and dignified living environments, particularly in regions facing recurrent seismic risks

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B. and M.E.B.; Methodology, S.B. and M.E.B.; Software, S.B. and M.E.B.; Formal analysis, S.B. and M.E.B.; Investigation, S.B. and M.E.B.; Writing—original draft, S.B. and M.E.B.; Writing—review & editing, S.B. and M.E.B.; Supervision, S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The research team utilized AI tools, mostly OpenAIs ChatGPT, during the preparation of this paper for two primary purposes: (1) identifying grammar mistakes and (2) assisting with writing LaTeX code. These tools were employed exclusively for editorial and technical support and were not used to generate any content, research ideas, or results. This use complies with the ethical guidelines and policies of the journal and our institution.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bertram, N.; Fuchs, S.; Mischke, J.; Palter, R.; Strube, G.; Woetzel, J. Modular Construction: From Projects to Products; McKinsey & Company, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Comerio, M.C. Housing Recovery in Chile: A Qualitative Mid-Program Review; University of California: Berkeley.

- Bernal, V. A.; Procee, P. (2012, May 11). Four years on: What China got right when rebuilding after the Sichuan earthquake. World Bank Blogs. 2013.

- Kalkan, M.; Kaçar, A. D.; Alptekin, O. Ülkelerin Deprem Sonrası Yeniden Yapılaşma Süreçlerinin Karşılaştırılması: Çin, Şili ve Türkiye Örnekleri. Tasarım + Kuram 2020, 16(31). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presidency of Strategy and Budget. Türkiye Earthquakes Recovery and Reconstruction Assessment (TERRA). 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Erem, O. 6 Şubat depremleri sonrası Erdoğan’ın konut vaadi neydi, bir yılda verilen sözler tutuldu mu? BBC News Turkey 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Learning from megadisasters: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake, The World Bank, Washington, DC, 2012. The World Bank: Washington, DC.

- Akyıldız, Ş.; Şafak, U.; Özcan, K.; Sert, A. Deprem Sonrası Etkin Politika Tasarımı: İyi Uygulama Örnekleri. In PwC Türkiye. PwC Türkiye, 2023.

- The Reconstruction Agency of Japan. Current status of reconstruction and future efforts. In The Reconstruction Agency. The Reconstruction Agency, Government of Japan, 2023.

- Seitablaiev, M. Ö.; Umaroğullari, F. Türkiye’de Betonarme Prefabrikasyon. Mimarlık Bilimleri ve Uygulamaları Dergisi (MBUD), 2020. [CrossRef]

- Amani, A.; Niyazi, A. Q. Rapid Development Prefabricated Construction Sector in Turkey. Mühendislik Bilimleri ve Tasarım Dergisi 2018, 6(3), 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.E.; Timberlake, J. Prefab Architecture: A Guide to Modular Design and Construction; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Building Sciences. Modular Construction for Multifamily Affordable Housing. WSP. Off-Site Construction Council, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, J. T.; O’Brien, W. J.; Choi, J. O. Industrial Project Execution Planning: Modularization versus Stick-Built. Practice Periodical on Structural 5576.0000270. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Akyürek, Y. Giydirme Cepheler ve Cam Seçimi (by Ö. Güvenli). Giydirme Cepheler Symposium, İstanbul, Turkey. (1991, December 21).

- Jeong, B.; Chang, S.; Mahalingam, A. “Impediments to modular construction implementation: A review”. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2016, Vol. 142(No. 11), 04016066. [Google Scholar]

- Dağ, İ.; Kaçar, Ö.; Alptekin, M. “Depreme dayanıklı prefabrike betonarme yapıların mimari ve yapısal açıdan incelenmesi”. Afet ve Risk Dergisi 2023, Vol. 5(No. 1), 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gültek, M.; Avinç, G. M.; Sarıcıoğlu, P.; Yıldız, A. Beton Esaslı Prefabrike Cephe Panellerinin Tarihsel Gelişiminin Farklı Ülkelerdeki Örnekler Üzerinden Değerlendirilmesi. Uluslararası Mühendislik Araştırma ve Geliştirme Dergisi 2023, 15(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A. Advances in Cladding. RIBA Advances in Technology Series, Oxford, 2002.

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. “Using thematic analysis in psychology”. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006, Vol. 3(No. 2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayrimenkul Yatırımcıları Derneği [GYODER]. İnşaat Sektörü ve İş Gücü Dinamikleri: Türkiye’24. In GYODER. Bahçeşehir Üniversitesi, 2025.

- Koman, İ. İnovasyon değerinin yaratılmasında mimarın rolünün Walter Gropius’un çalışmaları bağlamında analizi. Mimarlık Bilimleri ve Uygulamaları Dergisi (MBUD), 2021. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).