Submitted:

20 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Preliminaries and Problem Formulation

2.1. Modalities and Data Representation

2.2. Tokenization and Embedding Spaces

2.3. Multimodal Transformer Backbone

2.4. Learning Objectives

2.5. Inference and Multimodal Reasoning

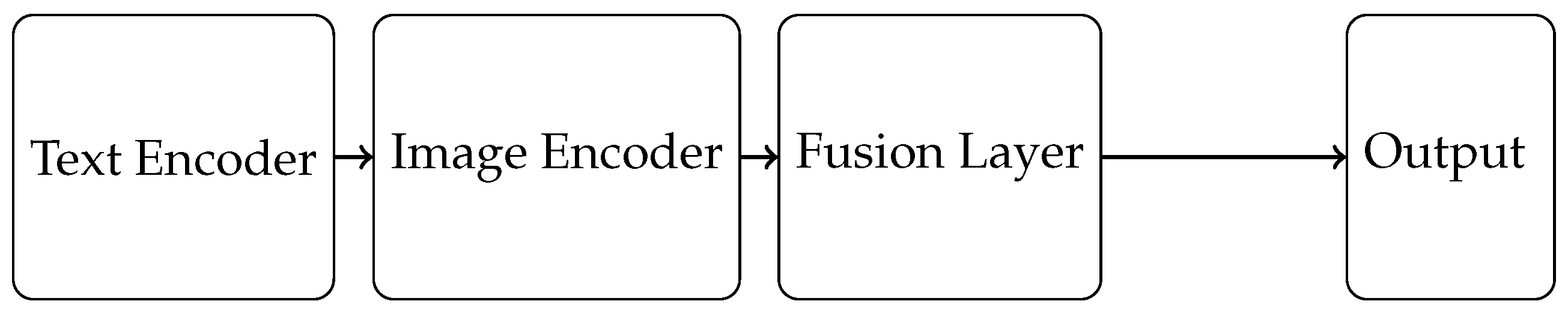

3. Architectural Approaches in Multimodal Large Language Models

4. Training Strategies for Multimodal Large Language Models

| Training Strategy | Description | Advantages | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contrastive Learning | Optimizes joint representations of aligned modality pairs | Improves cross-modal alignment | Requires large amounts of aligned data |

| Modality-Specific Pretraining | Pretrain individual modality encoders before multimodal fine-tuning | Leverages modality-specific features | Requires extensive pretraining data for each modality |

| Early Fusion | Combines modality-specific features at the initial layers of the model | Enables fine-grained multimodal interactions early in processing | Computationally expensive due to large input size |

| Late Fusion | Combines modality-specific features at the final layers of the model | Simpler architecture and easier to train | May fail to capture complex modality interactions |

| Model Distillation | Transfers knowledge from a large model to a smaller, more efficient one | Reduces memory and computation requirements | Distilled models may lose some accuracy |

| Sparse Attention | Limits the number of tokens that can attend to each other to reduce complexity | Reduces computational cost | May decrease model performance if too aggressive |

5. Applications of Multimodal Large Language Models

6. Challenges and Open Issues in Multimodal Large Language Models

7. Future Directions and Research Trends in Multimodal Large Language Models

8. Conclusions

References

- Mildenhall, B.; Srinivasan, P.P.; Tancik, M.; Barron, J.T.; Ramamoorthi, R.; Ng, R. Nerf: Representing scenes as neural radiance fields for view synthesis. Communications of the ACM 2021, 65, 99–106.

- Hong, Y.; Zhen, H.; Chen, P.; Zheng, S.; Du, Y.; Chen, Z.; Gan, C. 3d-llm: Injecting the 3d world into large language models. NeurIPS 2023.

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Küttler, H.; Lewis, M.; Yih, W.t.; Rocktäschel, T.; et al. Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive nlp tasks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 9459–9474.

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models. In Proceedings of the CVPR, 2022.

- Srinivasan, K.; Raman, K.; Chen, J.; Bendersky, M.; Najork, M. Wit: Wikipedia-based image text dataset for multimodal multilingual machine learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 2021, pp. 2443–2449.

- Bustos, A.; Pertusa, A.; Salinas, J.M.; De La Iglesia-Vaya, M. Padchest: A large chest x-ray image dataset with multi-label annotated reports. Medical image analysis 2020, 66, 101797.

- Jia, C.; Yang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Chen, Y.T.; Parekh, Z.; Pham, H.; Le, Q.; Sung, Y.H.; Li, Z.; Duerig, T. Scaling up visual and vision-language representation learning with noisy text supervision. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2021, pp. 4904–4916.

- Bu, H.; Du, J.; Na, X.; Wu, B.; Zheng, H. Aishell-1: An open-source mandarin speech corpus and a speech recognition baseline. In Proceedings of the O-COCOSDA, 2017.

- Hu, X.; Gan, Z.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Wang, L. Scaling up vision-language pre-training for image captioning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022, pp. 17980–17989.

- Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Nie, W.; Eaton, J.; Rees, B.; Gu, Q. MoleculeGPT: Instruction Following Large Language Models for Molecular Property Prediction. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2023 Workshop on New Frontiers of AI for Drug Discovery and Development, 2023.

- Rae, J.W.; Potapenko, A.; Jayakumar, S.M.; Lillicrap, T.P. Compressive transformers for long-range sequence modelling. arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.05507 2019.

- Lipping, S.; Sudarsanam, P.; Drossos, K.; Virtanen, T. Clotho-aqa: A crowdsourced dataset for audio question answering. In Proceedings of the 2022 30th European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1140–1144.

- Wang, Y.; Ma, X.; Zhang, G.; Ni, Y.; Chandra, A.; Guo, S.; Ren, W.; Arulraj, A.; He, X.; Jiang, Z.; et al. MMLU-Pro: A More Robust and Challenging Multi-Task Language Understanding Benchmark. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.01574 2024.

- He, X.; Zhang, Y.; Mou, L.; Xing, E.; Xie, P. Pathvqa: 30000+ questions for medical visual question answering. arXiv:2003.10286 2020.

- Liang, H.; Li, J.; Bai, T.; Chen, C.; He, C.; Cui, B.; Zhang, W. KeyVideoLLM: Towards Large-scale Video Keyframe Selection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.03104 2024.

- Lu, K.; Yuan, H.; Yuan, Z.; Lin, R.; Lin, J.; Tan, C.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, J. # InsTag: Instruction Tagging for Analyzing Supervised Fine-tuning of Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023.

- Reimers, N.; Gurevych, I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019.

- Hsu, C.; Verkuil, R.; Liu, J.; Lin, Z.; Hie, B.; Sercu, T.; Lerer, A.; Rives, A. Learning inverse folding from millions of predicted structures. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2022, pp. 8946–8970.

- Shu, F.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, H.; Xie, C. Audio-Visual LLM for Video Understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.06720 2023.

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Lee, Y.J. Improved baselines with visual instruction tuning. arXiv:2310.03744 2023.

- He, X.; Zhao, K.; Chu, X. AutoML: A survey of the state-of-the-art. Knowledge-based systems 2021, 212, 106622.

- Xu, R.; Yao, Y.; Guo, Z.; Cui, J.; Ni, Z.; Ge, C.; Chua, T.S.; Liu, Z.; Sun, M.; Huang, G. Llava-uhd: an lmm perceiving any aspect ratio and high-resolution images. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.11703 2024.

- Kafle, K.; Price, B.; Cohen, S.; Kanan, C. Dvqa: Understanding data visualizations via question answering. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 5648–5656.

- Ren, Y.; Hu, C.; Tan, X.; Qin, T.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, T.Y. Fastspeech 2: Fast and high-quality end-to-end text to speech. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.04558 2020.

- Wu, Z.; Song, S.; Khosla, A.; Yu, F.; Zhang, L.; Tang, X.; Xiao, J. 3d shapenets: A deep representation for volumetric shapes. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2015, pp. 1912–1920.

- Ye, J.; Hu, A.; Xu, H.; Ye, Q.; Yan, M.; Xu, G.; Li, C.; Tian, J.; Qian, Q.; Zhang, J.; et al. Ureader: Universal ocr-free visually-situated language understanding with multimodal large language model. In Proceedings of the EMNLP, 2023.

- Jiang, A.Q.; Sablayrolles, A.; Roux, A.; Mensch, A.; Savary, B.; Bamford, C.; Chaplot, D.S.; Casas, D.d.l.; Hanna, E.B.; Bressand, F.; et al. Mixtral of experts. arXiv:2401.04088 2024.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. NeurIPS 2017.

- Gadre, S.Y.; Ilharco, G.; Fang, A.; Hayase, J.; Smyrnis, G.; Nguyen, T.; Marten, R.; Wortsman, M.; Ghosh, D.; Zhang, J.; et al. Datacomp: In search of the next generation of multimodal datasets. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36.

- Johnson, A.E.W.; Pollard, T.J.; Greenbaum, N.R.; Lungren, M.P.; ying Deng, C.; Peng, Y.; Lu, Z.; Mark, R.G.; Berkowitz, S.J.; Horng, S. MIMIC-CXR-JPG, a large publicly available database of labeled chest radiographs, 2019, [arXiv:cs.CV/1901.07042].

- Sun, Z.; Shen, S.; Cao, S.; Liu, H.; Li, C.; Shen, Y.; Gan, C.; Gui, L.Y.; Wang, Y.X.; Yang, Y.; et al. Aligning large multimodal models with factually augmented rlhf. arXiv:2309.14525 2023.

- Han, J.; Zhang, R.; Shao, W.; Gao, P.; Xu, P.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, K.; Liu, C.; Wen, S.; Guo, Z.; et al. Imagebind-llm: Multi-modality instruction tuning. arXiv:2309.03905 2023.

- Yang, Z.; Gan, Z.; Wang, J.; Hu, X.; Lu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L. An empirical study of gpt-3 for few-shot knowledge-based vqa. In Proceedings of the AAAI, 2022.

- Lai, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wu, W.; Bai, H.; Timofeev, A.; Du, X.; Gan, Z.; Shan, J.; Chuah, C.N.; Yang, Y.; et al. From scarcity to efficiency: Improving clip training via visual-enriched captions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.07699 2023.

- Xia, M.; Malladi, S.; Gururangan, S.; Arora, S.; Chen, D. Less: Selecting influential data for targeted instruction tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.04333 2024.

- Nakano, R.; Hilton, J.; Balaji, S.; Wu, J.; Ouyang, L.; Kim, C.; Hesse, C.; Jain, S.; Kosaraju, V.; Saunders, W.; et al. Webgpt: Browser-assisted question-answering with human feedback. arXiv:2112.09332 2021.

- Hong, W.; Wang, W.; Lv, Q.; Xu, J.; Yu, W.; Ji, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Dong, Y.; Ding, M.; et al. Cogagent: A visual language model for gui agents. arXiv:2312.08914 2023.

- Panagopoulou, A.; Xue, L.; Yu, N.; Li, J.; Li, D.; Joty, S.; Xu, R.; Savarese, S.; Xiong, C.; Niebles, J.C. X-InstructBLIP: A Framework for aligning X-Modal instruction-aware representations to LLMs and Emergent Cross-modal Reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.18799 2023.

- Yu, Q.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, X.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wang, X.; Liu, J. Capsfusion: Rethinking image-text data at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.20550 2023.

- Young, P.; Lai, A.; Hodosh, M.; Hockenmaier, J. From image descriptions to visual denotations: New similarity metrics for semantic inference over event descriptions. TACL 2014.

- Suárez, P.J.O.; Sagot, B.; Romary, L. Asynchronous pipeline for processing huge corpora on medium to low resource infrastructures. In Proceedings of the 7th Workshop on the Challenges in the Management of Large Corpora (CMLC-7). Leibniz-Institut für Deutsche Sprache, 2019.

- Liu, Z.; Li, S.; Luo, Y.; Fei, H.; Cao, Y.; Kawaguchi, K.; Wang, X.; Chua, T.S. Molca: Molecular graph-language modeling with cross-modal projector and uni-modal adapter. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.12798 2023.

- Wu, P.; Xie, S. V*: Guided Visual Search as a Core Mechanism in Multimodal LLMs. arXiv:2312.14135 2023.

- Stiennon, N.; Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Ziegler, D.; Lowe, R.; Voss, C.; Radford, A.; Amodei, D.; Christiano, P.F. Learning to summarize with human feedback. NeurIPS 2020.

- Zhou, T.; Chen, Y.; Cao, P.; Liu, K.; Zhao, J.; Liu, S. Oasis: Data curation and assessment system for pretraining of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.12537 2023.

- Wang, Z.; Zhong, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Mi, F.; Wang, B.; Shang, L.; Jiang, X.; Liu, Q. Data management for large language models: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.01700 2023.

- Das, A.; Kottur, S.; Gupta, K.; Singh, A.; Yadav, D.; Moura, J.M.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Visual dialog. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 326–335.

- Singh, A.; Natarajan, V.; Shah, M.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, X.; Batra, D.; Parikh, D.; Rohrbach, M. Towards vqa models that can read. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019, pp. 8317–8326.

- Girdhar, R.; El-Nouby, A.; Liu, Z.; Singh, M.; Alwala, K.V.; Joulin, A.; Misra, I. Imagebind: One embedding space to bind them all. In Proceedings of the CVPR, 2023.

- Gu, J.; Meng, X.; Lu, G.; Hou, L.; Minzhe, N.; Liang, X.; Yao, L.; Huang, R.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, X.; et al. Wukong: A 100 million large-scale chinese cross-modal pre-training benchmark. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 26418–26431.

- Shu, Y.; Dong, S.; Chen, G.; Huang, W.; Zhang, R.; Shi, D.; Xiang, Q.; Shi, Y. Llasm: Large language and speech model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.15930 2023.

- Gao, J.; Sun, C.; Yang, Z.; Nevatia, R. Tall: Temporal activity localization via language query. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp. 5267–5275.

- Longpre, S.; Yauney, G.; Reif, E.; Lee, K.; Roberts, A.; Zoph, B.; Zhou, D.; Wei, J.; Robinson, K.; Mimno, D.; et al. A Pretrainer’s Guide to Training Data: Measuring the Effects of Data Age, Domain Coverage, Quality, & Toxicity. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.13169 2023.

- Kembhavi, A.; Salvato, M.; Kolve, E.; Seo, M.; Hajishirzi, H.; Farhadi, A. A diagram is worth a dozen images. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 11–14, 2016, Proceedings, Part IV 14. Springer, 2016, pp. 235–251.

- Pham, V.T.; Le, T.L.; Tran, T.H.; Nguyen, T.P. Hand detection and segmentation using multimodal information from Kinect. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Multimedia Analysis and Pattern Recognition (MAPR). IEEE, 2020, pp. 1–6.

- Rogers, V.; Meara, P.; Barnett-Legh, T.; Curry, C.; Davie, E. Examining the LLAMA aptitude tests. Journal of the European Second Language Association 2017, 1, 49–60.

- Kombrink, S.; Mikolov, T.; Karafiát, M.; Burget, L. Recurrent Neural Network Based Language Modeling in Meeting Recognition. In Proceedings of the Interspeech, 2011, Vol. 11, pp. 2877–2880.

- Askell, A.; Bai, Y.; Chen, A.; Drain, D.; Ganguli, D.; Henighan, T.; Jones, A.; Joseph, N.; Mann, B.; DasSarma, N.; et al. A general language assistant as a laboratory for alignment. arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.00861 2021.

- Chen, C.; Qin, R.; Luo, F.; Mi, X.; Li, P.; Sun, M.; Liu, Y. Position-enhanced visual instruction tuning for multimodal large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.13437 2023.

- Shen, S.; Hou, L.; Zhou, Y.; Du, N.; Longpre, S.; Wei, J.; Chung, H.W.; Zoph, B.; Fedus, W.; Chen, X.; et al. Mixture-of-experts meets instruction tuning: A winning combination for large language models. arXiv:2305.14705 2023.

- Piczak, K.J. ESC: Dataset for environmental sound classification. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 23rd ACM international conference on Multimedia, 2015, pp. 1015–1018.

- Roberts, J.; Lüddecke, T.; Sheikh, R.; Han, K.; Albanie, S. Charting new territories: Exploring the geographic and geospatial capabilities of multimodal llms. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.14656 2023.

- Hu, A.; Xu, H.; Ye, J.; Yan, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, B.; Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Jin, Q.; Huang, F.; et al. mPLUG-DocOwl 1.5: Unified Structure Learning for OCR-free Document Understanding. arXiv:2403.12895 2024.

- Byeon, M.; Park, B.; Kim, H.; Lee, S.; Baek, W.; Kim, S. COYO-700M: Image-Text Pair Dataset. https://github.com/kakaobrain/coyo-dataset, 2022.

- Zhao, H.; Andriushchenko, M.; Croce, F.; Flammarion, N. Long is more for alignment: A simple but tough-to-beat baseline for instruction fine-tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.04833 2024.

- Liu, Z.; Sun, M.; Zhou, T.; Huang, G.; Darrell, T. Rethinking the value of network pruning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.05270 2018.

- Feng, J.; Sun, Q.; Xu, C.; Zhao, P.; Yang, Y.; Tao, C.; Zhao, D.; Lin, Q. MMDialog: A Large-scale Multi-turn Dialogue Dataset Towards Multi-modal Open-domain Conversation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2023, pp. 7348–7363.

- Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Bing, L. Video-llama: An instruction-tuned audio-visual language model for video understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.02858 2023.

- Ben Abacha, A.; Demner-Fushman, D. A question-entailment approach to question answering. BMC bioinformatics 2019, 20, 1–23.

- Kung, P.N.; Yin, F.; Wu, D.; Chang, K.W.; Peng, N. Active Instruction Tuning: Improving Cross-Task Generalization by Training on Prompt Sensitive Tasks. In Proceedings of the The 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2023.

- Penedo, G.; Malartic, Q.; Hesslow, D.; Cojocaru, R.; Cappelli, A.; Alobeidli, H.; Pannier, B.; Almazrouei, E.; Launay, J. The RefinedWeb dataset for Falcon LLM: outperforming curated corpora with web data, and web data only. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.01116 2023.

- Honda, S.; Shi, S.; Ueda, H.R. Smiles transformer: Pre-trained molecular fingerprint for low data drug discovery. arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.04738 2019.

- Han, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ding, N.; Gu, Y.; Liu, X.; Huo, Y.; Qiu, J.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, L.; et al. Pre-trained models: Past, present and future. AI Open 2021, 2, 225–250.

- Rasheed, H.; Maaz, M.; Shaji, S.; Shaker, A.; Khan, S.; Cholakkal, H.; Anwer, R.M.; Xing, E.; Yang, M.H.; Khan, F.S. Glamm: Pixel grounding large multimodal model. arXiv:2311.03356.

- Dettmers, T.; Pagnoni, A.; Holtzman, A.; Zettlemoyer, L. Qlora: Efficient finetuning of quantized llms. arXiv:2305.14314 2023.

- Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Fan, W.; Wei, X.Y.; Liu, H.; Tang, J.; Li, Q. Empowering Molecule Discovery for Molecule-Caption Translation with Large Language Models: A ChatGPT Perspective. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.06615 2023.

- Wang, D.; Shang, Y. A new active labeling method for deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2014 International joint conference on neural networks (IJCNN). IEEE, 2014, pp. 112–119.

- Zhao, Q.; Gao, X.; Li, J.; Luo, L. Optimization algorithm for point cloud quality enhancement based on statistical filtering. Journal of Sensors 2021, 2021, 1–10.

- Shen, Y.; Song, K.; Tan, X.; Li, D.; Lu, W.; Zhuang, Y. Hugginggpt: Solving ai tasks with chatgpt and its friends in huggingface. arXiv:2303.17580 2023.

- Yuan, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, J.; Tang, D.; Luo, X.; Qin, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, J. Osprey: Pixel Understanding with Visual Instruction Tuning. arXiv:2312.10032.

- Chen, C.; Liu, M.; Codella, N.; Li, Y.; Yuan, L.; Gurari, D. Fully authentic visual question answering dataset from online communities. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.15562 2023.

- Agrawal, H.; Desai, K.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Jain, R.; Johnson, M.; Batra, D.; Parikh, D.; Lee, S.; Anderson, P. Nocaps: Novel object captioning at scale. In Proceedings of the ICCV, 2019.

- Jiang, J.; Shu, Y.; Wang, J.; Long, M. Transferability in deep learning: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2201.05867 2022.

- Friedman, D.; Dieng, A.B. The vendi score: A diversity evaluation metric for machine learning. Transactions on Machine Learning Research 2023.

- Lyu, C.; Wu, M.; Wang, L.; Huang, X.; Liu, B.; Du, Z.; Shi, S.; Tu, Z. Macaw-llm: Multi-modal language modeling with image, audio, video, and text integration. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.09093 2023.

- He, P.; Liu, X.; Gao, J.; Chen, W. DEBERTA: DECODING-ENHANCED BERT WITH DISENTANGLED ATTENTION. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, 2020.

- Liu, Y.; Cao, J.; Liu, C.; Ding, K.; Jin, L. Datasets for Large Language Models: A Comprehensive survey, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CL/2402.18041].

- Schuhmann, C.; Köpf, A.; Vencu, R.; Coombes, T.; Beaumont, R. Laion coco: 600m synthetic captions from laion2b-en. https://laion.ai/blog/laion-coco/ 2022.

- Zhao, Z.; Guo, L.; Yue, T.; Chen, S.; Shao, S.; Zhu, X.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, J. ChatBridge: Bridging Modalities with Large Language Model as a Language Catalyst. arXiv:2305.16103 2023.

- Su, Y.; Lan, T.; Li, H.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Cai, D. PandaGPT: One Model To Instruction-Follow Them All. arXiv:2305.16355 2023.

- Xue, L.; Yu, N.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Martín-Martín, R.; Wu, J.; Xiong, C.; Xu, R.; Niebles, J.C.; Savarese, S. ULIP-2: Towards Scalable Multimodal Pre-training for 3D Understanding, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CV/2305.08275].

- Xu, J.; Mei, T.; Yao, T.; Rui, Y. Msr-vtt: A large video description dataset for bridging video and language. In Proceedings of the CVPR, 2016.

- Hernandez, D.; Brown, T.; Conerly, T.; DasSarma, N.; Drain, D.; El-Showk, S.; Elhage, N.; Hatfield-Dodds, Z.; Henighan, T.; Hume, T.; et al. Scaling laws and interpretability of learning from repeated data. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.10487 2022.

- Zhang, R.; Hu, X.; Li, B.; Huang, S.; Deng, H.; Qiao, Y.; Gao, P.; Li, H. Prompt, generate, then cache: Cascade of foundation models makes strong few-shot learners. In Proceedings of the CVPR, 2023.

- Ye, J.; Liu, P.; Sun, T.; Zhou, Y.; Zhan, J.; Qiu, X. Data Mixing Laws: Optimizing Data Mixtures by Predicting Language Modeling Performance. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.16952 2024.

- Xu, Z.; Feng, C.; Shao, R.; Ashby, T.; Shen, Y.; Jin, D.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, Q.; Huang, L. Vision-Flan: Scaling Human-Labeled Tasks in Visual Instruction Tuning. arXiv:2402.11690 2024.

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2021, pp. 8748–8763.

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. In Proceedings of the ECCV, 2014.

- Li, J.; Li, D.; Savarese, S.; Hoi, S. Blip-2: Bootstrapping language-image pre-training with frozen image encoders and large language models. arXiv:2301.12597 2023.

- Goyal, S.; Choudhury, A.R.; Raje, S.; Chakaravarthy, V.; Sabharwal, Y.; Verma, A. Power-bert: Accelerating bert inference via progressive word-vector elimination. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2020, pp. 3690–3699.

- Li, B.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Liu, Z. Otter: A multi-modal model with in-context instruction tuning. arXiv:2305.03726 2023.

- Fan, S.; Pagliardini, M.; Jaggi, M. Doge: Domain reweighting with generalization estimation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.15393 2023.

- Wang, L.; Yang, N.; Huang, X.; Jiao, B.; Yang, L.; Jiang, D.; Majumder, R.; Wei, F. Text embeddings by weakly-supervised contrastive pre-training. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.03533 2022.

- Li, L.; Yin, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, L.; Wang, P.; Ren, S.; Li, M.; Yang, Y.; Xu, J.; Sun, X.; et al. M3IT: A Large-Scale Dataset towards Multi-Modal Multilingual Instruction Tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.04387 2023.

- Schuhmann, C.; Vencu, R.; Beaumont, R.; Kaczmarczyk, R.; Mullis, C.; Katta, A.; Coombes, T.; Jitsev, J.; Komatsuzaki, A. Laion-400m: Open dataset of clip-filtered 400 million image-text pairs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2111.02114 2021.

- Zhu, D.; Chen, J.; Shen, X.; Li, X.; Elhoseiny, M. MiniGPT-4: Enhancing Vision-Language Understanding with Advanced Large Language Models, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CV/2304.10592].

- Chen, D.; Dolan, W.B. Collecting highly parallel data for paraphrase evaluation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 49th annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics: human language technologies, 2011, pp. 190–200.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).