1. Introduction: The Collapse of the Digital "Sacred Object"

1.1. Historical Background

In March 2021, the art world was shaken by a seemingly impossible event: a JPEG file sold for

$69 million at Christie’s auction house. The digital work titled

Everydays: The First 5000 Days by Mike Winkelmann (known as Beeple) became the symbol of what was proclaimed as a "revolution" in the art world—the arrival of

Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) as a new medium destined to democratize the art market and liberate artists from the grip of traditional

gatekeeping institutions [

13].

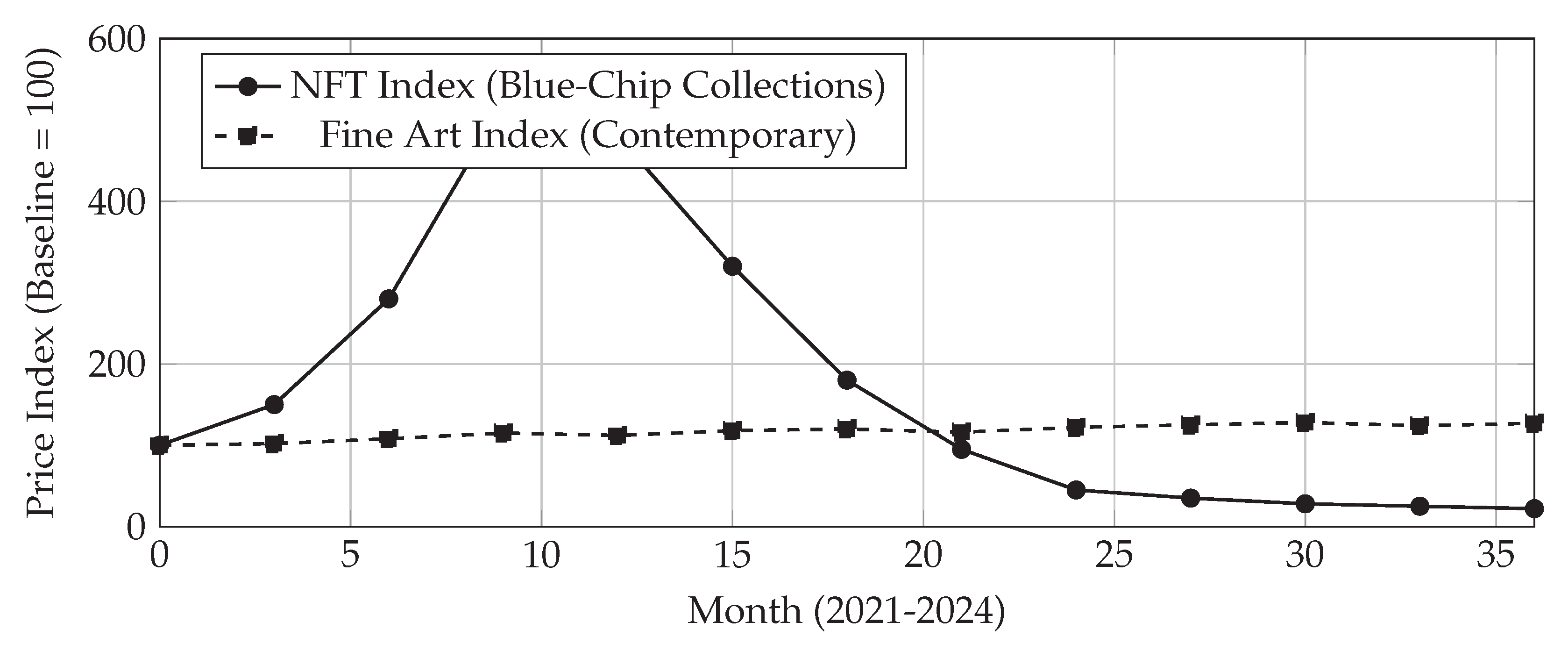

In the following 18 months, the NFT market experienced exponential growth. Monthly trading volume peaked at $5 billion in January 2022. Celebrities, multinational corporations, and millions of speculators rushed into an ecosystem promising instant wealth through the ownership of "unique" and "rare" digital assets. The dominant narrative at the time was that blockchain had solved a fundamental problem in the digital economy: artificial scarcity verified cryptographically.

However, only two years later, by mid-2023, more than 95% of all NFT projects had lost their value. A survey by dappGambl [

16] found that 79% of all NFT collections had a market value of zero—there were no buyers at all at any price point. Even "blue-chip" projects like

Bored Ape Yacht Club saw their value decline by more than 90% from their peak. More shockingly: the same Beeple work that sold for

$69 million in 2021 was estimated to be worth only around

$10 million by the end of 2023—losing 85% of its value in less than three years.

1.2. Problematics: The Paradox of Scarcity Without Value

The contrast with the traditional art market is striking. A 500-year-old canvas painting by a Renaissance master can maintain or even increase its value across generations. Works by modern masters like Picasso or Rothko are consistently valued at tens to hundreds of millions of dollars, even during global economic turbulence [

9]. Meanwhile, "assets of the future" claimed to be technologically superior—created with unforgeable cryptographic standards—lost almost all their value in a matter of months.

This paradox raises a fundamental question: Why do physical objects that can be reproduced (paintings can be photographed, scanned, forged) maintain their symbolic and financial value, while digital objects that are technologically "rarer" (verified by immutable blockchain) lose their value catastrophically?

The conventional explanation—that this is simply a classic case of a speculative bubble bursting—is insufficient. Speculative bubbles occur in various markets, but not all assets lose 95-99% of their value following a market correction. The traditional art market itself has experienced corrections (e.g., the crashes of 1990-1991 or 2008-2009), yet important works retained substantial value and recovered within a few years. There are distinct structural mechanisms operating here.

1.3. Central Hypothesis: Institutional Failure as Theological Failure

This paper proposes the hypothesis that the failure of NFTs is fundamentally an institutional failure that can be understood through an analogy with theological structures of legitimacy. Value in the art economy is not an intrinsic property of the object itself, but the result of complex social processes similar to consecration mechanisms in religious institutions—a process we will term value transubstantiation.

In Catholic theology, transubstantiation is the doctrine that bread and wine, through the Eucharistic ritual performed by a legitimate priest, literally change into the body and blood of Christ—even though their physical appearance remains the same. The crucial point here is that this transformation is valid only if performed by a priest who possesses apostolic succession—an unbroken chain of ordination traceable back to the Apostles ordained directly by Jesus Christ.

The parallel with the art world is striking. A mass-produced ceramic urinal—a utilitarian object worth

$5—can transform into an art work worth millions of dollars (

Fountain by Marcel Duchamp, 1917) not because of any physical change to the object, but because of a ritual of consecration performed by institutions possessing legitimate authority: exhibition in a museum context, writing by leading critics and art historians, teaching in university curricula, and acquisition by museum collections [

4,

5].

NFTs attempted what in a religious context would be called a "Protestant Reformation"—eliminating intermediaries (curators, galleries, critics) and providing direct access between artist and collector, much as Protestantism advocated direct access to God without priestly mediation. However, as this paper will argue, without building alternative mechanisms for legitimacy—without creating a credible new chain of authority (sanad)—this alternative "church" collapses into a dogma-less cacophony, where everyone claims authority but no one truly possesses it.

1.4. Theoretical Significance

The contribution of this paper is twofold:

First, theoretically, it extends and integrates Bourdieu’s theory of the field of cultural production with concepts from the sociology of religion and institutional theology, creating a new framework for understanding the mechanisms of symbolic value consecration. By translating theological concepts such as apostolic succession, transubstantiation, and canonization into sociological analysis of art, we gain a more precise language to describe processes often depicted by Bourdieu in more abstract terms like "symbolic violence" or "misrecognition."

Second, practically, this analysis provides a deeper understanding of why technology, however innovative, cannot by itself create value if not supported by adequate sociological infrastructure. This has important implications not only for the digital art market but also for any attempt at "disruption" of established institutions that ignores the function of institutional legitimacy [

17].

This paper is structured as follows: Section II builds the theoretical framework by synthesizing Bourdieu and theological concepts. Section III explains the methodology and limitations of the analogy. Section IV analyzes the structure of "The Traditional Art Church." Section V dissects the NFT ecosystem as "The Digital Heresy." Section VI introduces the concept of ontological debt. Section VII discusses broader implications, Section VIII presents limitations and counter-arguments, and Section IX concludes with reflections on the future of digital art.

2. Theoretical Framework: Bourdieu Meets Theology

2.1. Bourdieu and Symbolic Violence in the Field of Art

Pierre Bourdieu, in his monumental work

The Field of Cultural Production [

1], proposed the thesis that art is not the result of individual genius working in a vacuum, but the product of a

field—a structured social space where various agents (artists, galleries, critics, collectors, educational institutions) compete to accumulate

symbolic capital.

The radical aspect of Bourdieu’s analysis is his demonstration that artistic value is the result of a series of collective

misrecognitions. What appears as "pure" aesthetic appreciation or recognition of an artwork’s "intrinsic quality" is actually the result of a long socialization process that has implanted specific schemes of perception and appreciation in the individual habitus [

2]. Bourdieu writes:

"The work of art is an object which exists as such only by virtue of the (collective) belief which knows and acknowledges it as a work of art."

Consecration—the process by which a profane object is transformed into a valuable work of art—does not occur through the inherent quality of the object itself, but through a series of institutional actions: curation, exhibition, criticism, collection, teaching, and historical writing. Each of these actions is a ritual that adds a layer of legitimacy, until finally, the object is universally accepted as "art."

A crucial point for our analysis is Bourdieu’s emphasis on the temporal dimension of this process. Symbolic capital accumulates slowly and requires long-term investment. Successful artists are not those chasing quick financial profit (economic capital), but those willing to engage in disinterested practice—practice without immediate economic motive—for the sake of accumulating symbolic capital first, with the understanding that this can eventually be converted into economic capital.

2.2. Apostolic Succession: The Theological Model of Legitimacy

In Christian theology, particularly the Catholic and Orthodox traditions, apostolic succession is the doctrine stating that ecclesiastical authority is valid only if it can be traced through an unbroken chain of ordination back to the Apostles. A bishop is legitimate only if ordained by a legitimate bishop, who in turn was ordained by a previous legitimate bishop, and so on back to the Apostle Peter and his colleagues ordained directly by Jesus.

This doctrine is not merely a bureaucratic formality, but a mechanism to guarantee the

continuity of truth. In theological logic, the truth of Christian teaching is guaranteed not only by the text of Scripture (which can be interpreted in various ways) but by the

living tradition—the transmission of knowledge from teacher to student in an unbroken chain [

21].

Similar concepts can be found in the Islamic tradition as sanad or isnad—the chain of transmission validating hadith (sayings of the Prophet Muhammad). A hadith is considered authentic only if every narrator in its transmission chain can be verified for credibility. In the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, the concept of lineage (brgyud pa) functions similarly, where the validity of teachings depends on a traceable teacher-to-student transmission chain.

The crucial aspect of this model is that legitimacy is relational and genealogical, not substantive. One cannot claim authority simply because one "understands" the teaching or "experiences" enlightenment; one must be able to show who gave them that authority.

2.3. Synthesis: The Chain of Value in the Art Economy

When we apply the apostolic succession model to Bourdieu’s art field, we get a much more precise framework for understanding consecration mechanisms. Artists do not gain legitimacy solely from the "quality" of their work (which is hard to measure and highly subjective), but from

who consecrates them [

6]:

Which gallery exhibits their work?

Which curator writes about them?

Which museum collection acquires their work?

Which critic gives a positive review?

Which university teaches them?

Each of these institutions possesses legitimacy due to its own

historical chain—the

Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) has authority because it was founded in 1929 and has curated exhibitions defining the canon of modern art. Critics like Clement Greenberg have authority because their writings shaped our understanding of Abstract Expressionism [

24]. Galleries like Gagosian have authority because they have represented the most important artists of the last 50 years.

This forms a hierarchy of consecration analogous to the ecclesiastical hierarchy:

Table 1.

Structural Parallel: Hierarchy of Consecration.

Table 1.

Structural Parallel: Hierarchy of Consecration.

| Ecclesiastical Hierarchy |

Art Hierarchy |

| Pope |

Major Museums (MoMA, Tate, etc.) |

| Cardinals |

Blue-chip Galleries (Gagosian, Pace) |

| Bishops |

Regional Museums, Mid-tier Galleries |

| Priests |

Curators, Established Critics |

| Deacons |

Emerging Curators, Art Writers, Academics |

| Laity |

Collectors, Public |

Artists "ordained" by top-tier institutions gain legitimacy that then facilitates consecration by next-tier institutions, and so on. But crucially: there is no self-ordination. One cannot declare oneself an "important artist"—one must be consecrated by an institution that already possesses legitimacy.

2.4. Operational Terminology

To facilitate subsequent analysis, we will use the following terminological translation:

Field (Bourdieu) → Cathedral/Church: Structured social space with a clear hierarchy of authority.

Consecration→Transubstantiation: Ontological transformation from profane object to "sacred object" (artwork).

Symbolic Capital→Grace/Charisma: Invisible charisma that is recognized and confers authority.

Habitus→Catechism: Internalization of perception schemes through long socialization.

Misrecognition→Faith/Belief: Acceptance of value without questioning the foundation of its legitimacy.

This translation is not merely a linguistic game, but an analytical strategy to make explicit the dimensions implicit in Bourdieu’s theory. By using religious language, we emphasize the aspects of

collective belief and

ritualistic practice fundamental to the symbolic economy of art [

20].

3. Methodology and Limitations of Analogy

3.1. Comparative-Structural Approach

This paper uses a structural analogy approach, comparing structures and mechanisms between two different systems (religious institutions vs. art institutions) to identify similar operating principles. This method has a long precedent in social science, from Durkheim’s organic analogy to Lévi-Strauss’s structural analysis.

Empirical data used include:

- (1)

Market Data: Trading volume, price fluctuations, and holder statistics from NFT platforms (OpenSea, LooksRare) for the period 2021-2024, compared with traditional art auction data (Christie’s, Sotheby’s) for the same period.

- (2)

Institutional Analysis: Documentation on curatorial processes, museum acquisitions, and artist career patterns in the traditional system vs. the NFT ecosystem.

- (3)

Discourse Analysis: Analysis of dominant narratives in NFT marketing, community manifestos, and "democratization" rhetoric used by NFT projects.

3.2. Limitations and Caveats: Where the Analogy Breaks Down

It is important to acknowledge that every analogy has limitations. Art institutions are not identical to religious institutions, and forcing total equivalence would be reductionist. Here are some fundamental differences:

1. Truth Claims

Religious institutions make metaphysical and transcendent truth claims—about the nature of reality, life after death, and absolute moral obligations. Art institutions, conversely, generally do not claim that a specific artwork is "true" in an ontological sense. Art value is more constructed and contingent.

However, this does not entirely invalidate the analogy. Art institutions

do make quasi-transcendent claims about "universal aesthetic value," "historical urgency," and "cultural significance"—claims that, while not metaphysical, still function as unquestionable legitimacy within their field [

23].

2. Stakes and Consequences

In a religious context, "heresy" can result in eternal damnation or exclusion from the community of salvation. In an art context, "heresy" merely results in... market unsellability or exclusion from the art historical canon.

Nevertheless, for the actors involved—artists, collectors, institutions—the stakes can be equally existential. Artists who are not consecrated experience symbolic death in their field; collectors who invest wrongly face potentially devastating financial losses; institutions losing legitimacy become irrelevant.

3. Enforcement Mechanisms

The Church has formal and institutional enforcement mechanisms—excommunication, anathema, and (historically) legal or physical sanctions. Art institutions work through more diffuse and less formal mechanisms—exclusion from exhibitions, absence from publications, or being ignored in history.

Nonetheless, the symbolic violence produced can be equally effective. Artists who do not "enter" the gallery-museum system find it almost impossible to achieve high prices or historical recognition, regardless of the "quality" of their work.

3.3. Heuristic Justification

Why persist with the theological analogy despite these differences? Because this analogy is heuristically productive—it helps us see aspects of art institutions that are often hidden or naturalized.

By comparing art consecration to sacramental transubstantiation, we explicate that value transformation is a

ritual act requiring specific conditions, not a natural result of the object’s intrinsic quality. By comparing artist legitimacy to apostolic succession, we emphasize the importance of

genealogical continuity in a field that often claims to value "originality" and "rupture" [

25].

Analogy is not identity, but it is a powerful instrument of cognition.

4. The White Cube Church: Anatomy of Traditional Consecration

4.1. Sacred Architecture: The White Cube as Liturgical Space

The term "white cube" was coined by critic Brian O’Doherty in 1976 to describe the characteristic modern gallery space: white walls, overhead lighting, no windows, a space appearing neutral and timeless. O’Doherty argued that this space is not neutral at all, but an

ideological construct defining what counts as "serious" art [

22].

The parallel with sacred architecture is clear. Gothic cathedrals, with their high ceilings, light entering through stained glass, and acoustics creating reverberation, were designed to create a transcendental experience—to make visitors feel they had entered a space distinct from the profane world outside.

The white cube does the same. When you enter a Chelsea gallery or the Museum of Modern Art, a ritual transition occurs: you leave the bustle of Manhattan streets and enter a silent, bright space where every object is displayed with reverential care. This context itself consecrates—it sends a signal: "The objects here are different. They are not ordinary commercial goods. They require contemplation, respect, and seriousness."

4.2. Hierarchy of Clergy: Structure of Authority in the Art Field

Just as the Catholic Church has a clear hierarchy—from Pope to cardinals, bishops, priests—the art field has a clear, albeit informal, stratification of authority.

Level 1: "Vatican" - Major Museums

At the top of the hierarchy are major museums like MoMA (New York), Tate Modern (London), Centre Pompidou (Paris), or the Guggenheim. These museums function as final arbiters of what enters the art historical canon. Acquisition by these museums is the highest form of consecration—it literally guarantees that the work will be "immortalized" for future generations.

Level 2: "Cardinals" - Blue-Chip Galleries

Top-tier galleries like Gagosian, Pace, David Zwirner, or Hauser & Wirth possess authority approaching that of museums. They can "make" an artist’s career by recruiting them into their roster. Representation by these galleries is a very strong signal to the market that this artist is "serious" and investment-worthy.

Level 3: "Bishops" - Regional Museums and Mid-Tier Galleries

These institutions serve an important function in the hierarchy: they disseminate the "doctrine" already consecrated by the highest level and help identify new talent that might ascend to the highest level.

Level 4: "Priests" - Curators and Critics

These individuals are the

interpreters of dogma. They write exhibition catalogues, critical essays, and art history books that form public understanding of the work’s meaning and significance. Curators decide which works are displayed in exhibitions; critics decide which works are "important" and worthy of discussion [

27].

Crucially, their authority stems from institutional affiliation and educational credentials—they hold PhDs from prestigious universities, work for leading institutions, and have been consecrated by the previous generation through publication in cited journals and appointments to curatorial positions.

Level 5: "Deacons" - Emerging Curators, Art Writers, Academics

This is the generation being "ordained"—individuals still building credentials but being trained in the field’s "doctrine" through doctoral programs, curatorial residencies, or assistant positions in established institutions.

Level 6: "Congregation" - Collectors and Public

At the bottom level are the "laity"—those who buy art, visit exhibitions, and ultimately provide the economic capital making the whole system function. However, they generally do not possess the authority to define what is valuable; they accept the judgments consecrated by the levels above them.

4.3. Ritual of Transubstantiation: From Object to Art Work

How exactly does a profane object—canvas with paint, welded metal, or even a factory urinal—transform into a "work of art"? This process is not magical, but ritualistic and institutional.

Ritual 1: Selection and Curation

The first stage is selection. From thousands of artists producing work, curators choose a handful to exhibit. This act of selection itself is an initial form of consecration distinguishing work "worthy of attention" from that which is not.

Ritual 2: Spatial Consecration

The work is then placed in the white cube—a space already consecrated. This spatial context alters viewer perception. The same object, if placed in an ordinary furniture store, would be perceived as decoration; in a Chelsea gallery, it becomes an object of artistic contemplation.

Ritual 3: Textual Consecration

Curators write wall text—short descriptions accompanying the work—and catalogue essays explaining the work’s "meaning" and "significance" in the context of art history. This text functions like biblical exegesis—it provides an authoritative interpretive framework.

Ritual 4: Critical Discourse

Critics write reviews in prestigious publications (Artforum, Art in America, Frieze). Positive reviews in these publications are highly valuable endorsements—they add a layer of legitimacy and make the work "visible" to serious collectors and other institutions.

Ritual 5: Market Validation

Galleries set prices—an act that is not solely economic but also semiotic. High prices

signal high artistic value [

7]. Sales to important collectors or at public auctions add further legitimacy.

Ritual 6: Institutional Collection

The pinnacle of consecration is acquisition by a museum. This is the form of final "canonization," where the work is literally entered into a permanent collection to be preserved for future generations and taught in art history curricula.

4.4. Intergenerational Catechism: Reproduction of Belief

What makes this system sustainable across generations is the educational infrastructure—the process by which trust in institutions and their judgments is reproduced.

Children are taken to museums on school field trips, where they learn that the objects here are "important" and "valuable." Art students study curated art history—a canon determined by previous generations. They read textbooks teaching that Picasso was a "genius," that Pollock was "revolutionary," that Warhol "changed art forever."

This process is indoctrination—not in a negative sense, but in a neutral sociological sense: the transmission of a belief system from one generation to the next. Once internalized, this belief becomes "common sense"—appearing as objective fact rather than social construction.

Bourdieu calls this the formation of habitus—dispositions of perception and appreciation that become "second nature." When someone with a formed art habitus views a Rothko, they do not "think" about its value, but intuitively "feel" its quality, because their perception schemes have been programmed to recognize specific value signals.

4.5. Temporal Dimension: Time as a Source of Legitimacy

One of the most important aspects of the traditional consecration system is the temporal dimension. Legitimacy requires time—it cannot be generated instantly.

"Important" artists generally do not become important overnight. They build careers over decades, through gradually more prestigious exhibitions, acquisitions by increasingly important collections, and the accumulation of increasingly substantial critical discourse. This process creates narrative depth—a history that can be told, a trajectory that can be traced.

Museums are literally institutions that "keep time"—they preserve objects from the past for the future. When museums acquire contemporary work, they are making a prediction: this is work that will remain relevant for future generations. This prediction is self-fulfilling—because the museum keeps it, it will remain relevant.

This temporal dimension creates what we will call ontological debt—a concept to be explored further in Section VI.

5. The Digital Heresy: Anatomy of the NFT Ecosystem

5.1. The Protestant Moment: Decentralization as Ideology

The fundamental narrative driving the NFT boom was the narrative of disintermediation—the elimination of intermediaries between artists and collectors. NFT project manifestos repeatedly emphasized this theme:

"For too long, artists have been at the mercy of gatekeepers, galleries that take 50% commission, curators who decide what’s ’good’, critics who can make or break careers. NFTs democratize art. Anyone can mint. Anyone can collect. The community decides value, not elites."

This rhetoric is very similar to the rhetoric of the Protestant Reformation: The Catholic Church was seen as corrupt, priests selling indulgences (simony), ordinary people having no direct access to truth because they had to be mediated by the clergy. Martin Luther offered a solution: sola scriptura (Scripture alone), priesthood of all believers (where everyone can access God directly without a priest).

NFTs offered an analog: sola blockchain (code alone, not institutions), collectorship of all participants (everyone can determine value, not just the educated elite).

This was a seductive narrative, especially in the context of the cultural zeitgeist of the 2020s characterized by distrust of established institutions and celebration of "disruptive" technology. However, as we will show, this narrative ignores the fundamental function played by institutions in the production of trust.

5.2. The Missing Genealogy: The Absence of Sanad

When we examine the artists who became millionaires in the NFT boom, a striking pattern emerges: almost none of them had an institutional pedigree in the traditional art world.

Take Beeple (Mike Winkelmann) as a paradigmatic case. Before the $69 million sale at Christie’s in March 2021, Beeple was a digital artist relatively unknown in the contemporary art world. He had no blue-chip gallery representation. His work was not in major museum collections. He was not mentioned in digital art history books. He did not hold an MFA from a prestigious art school. In other words: he lacked apostolic succession—there was no chain of institutional consecration linking him to the art canon.

What he had was: 1.8 million Instagram followers and a viral presence on social media.

In our terminology: Beeple was not "ordained" by an "art bishop"; he self-ordained through the accumulation of attention economy on digital platforms. This is analogous to someone claiming to be a bishop without ever being ordained by another bishop in the apostolic line—an act that, in theology, is called invalid ordination.

Similar patterns are seen across almost the entire NFT ecosystem:

CryptoPunks: Created by Larva Labs (two programmers) in 2017 as a technical experiment, not an artistic statement. No critical discourse, no curatorial framing, no institutional validation—until the 2021 hype cycle began.

Bored Ape Yacht Club: Launched in April 2021 by four people using pseudonyms. No serious artistic statement, no positioning in digital art history, no institutional backing. Main marketing: celebrity endorsement and promises of "community" and "utility."

Art Blocks: A generative art platform launching thousands of projects. Some artists had pedigrees (Tyler Hobbs, Dmitri Cherniak), but the majority were programmers or hobbyists without institutional validation.

5.3. Digital Simony: Wash Trading and Artificial Hype

In the Middle Ages, simony—the buying and selling of ecclesiastical offices or sacraments—was considered a grave sin. One cannot buy spiritual grace; it must be received through grace and legitimate process.

The NFT ecosystem was filled with the equivalent of simony: wash trading, where individuals or groups buy and sell NFTs to themselves to create the illusion of demand and raise the floor price.

A study by Chainalysis [

15] found that

wash trading accounted for up to 50% of NFT trading volume on certain platforms. This is not merely market manipulation in a financial sense—it is the

fabrication of consecration. High prices in a normal system are a signal that an object has been consecrated; in the NFT system, high prices were often artificial, created through self-dealing.

Besides wash trading, the NFT ecosystem relied heavily on influencer shilling—celebrities or crypto influencers with millions of followers promoting specific NFT projects (often because they were paid or had a financial interest). This created FOMO (fear of missing out) and drove impulsive buying.

In our analogy: this is like hiring actors to pretend to be saints and perform fake "miracles" to attract a congregation. It produces the appearance of legitimacy without underlying substance.

5.4. Discursive Failure: Absence of Critical Infrastructure

One of the most striking differences between traditional art and NFTs is the absence of serious critical discourse in the NFT ecosystem.

In traditional art, every important movement or artist is accompanied by a large volume of critical writing—essays, books, academic articles—analyzing, interpreting, and positioning the work in historical and theoretical contexts. Greenberg wrote on Abstract Expressionism, Rosalind Krauss on Minimalism, Hal Foster on the Neo-Avant-Garde [

26]. These writings are

not mere descriptions; they are

constitutive of value—they create the interpretive frameworks that make work "meaningful."

NFTs, conversely, have almost no serious critical writing. The dominant forms are:

Marketing Copy: Twitter threads and Discord announcements promoting "utility" and "community" but not engaging with aesthetic or conceptual dimensions.

Financial Analysis: Articles on "top performing collections" and "investment strategies," using financial language, not art criticism.

Technical Documentation: Explanations of smart contracts and tokenomics, not artistic weight.

Some contemporary art publications like Artforum or Frieze tried to write about NFTs, but coverage was skeptical or dismissive, as traditional art institutions largely viewed NFTs as a financial spectacle, not a serious artistic development.

This absence of critical infrastructure means that NFTs are not integrated into the discourse of art history. They exist in a theoretical vacuum—objects traded but not interpreted, owned but not understood in the context of broader art narratives.

5.5. The Utility Fallacy: Collapsing the Sacred into the Profane

One of the most revealing aspects of NFTs is the obsession with utility—the idea that an NFT must "do something" beyond being art. Bored Ape Yacht Club promised "membership" to a virtual club and access to exclusive events. Other projects promised token staking, game integration, or merchandise.

This is a fundamental category error revealing a misunderstanding of how art acquires value. In traditional art logic, an artwork is valuable precisely because it is not utilitarian—it is an object of contemplation transcending economic use-value. This is what Kant called disinterested aesthetic contemplation.

When NFT projects emphasize utility, they implicitly admit that the object itself is insufficient—it requires external justification for its value. This destroys the aura—the sacred quality making art distinct from ordinary commodities.

Imagine if the Catholic Church began marketing the Eucharist by emphasizing the "nutritional value" of the wafer or the "health benefits" of the wine. It would destroy the sanctity of the ritual—it would collapse the spiritual dimension into the utilitarian dimension.

NFTs do the same. By emphasizing utility, they reveal they are unable to create intrinsic symbolic value—value existing independently of external function.

7. Ontological Debt: Why Collectors Hold or Fold

7.1. The Concept of Ontological Debt

This is the most original theoretical concept in this paper, so we will develop it extensively.

Ontological debt is the psychological debt felt by an individual toward historical and cultural narratives that give meaning to their existence. It is the feeling that we "owe something" to the past—to human achievements that make our lives possible.

When someone buys a Picasso painting for

$50 million, they are not just buying paint and canvas. They are buying the

embodiment of historical significance—an object that has witnessed 20th-century art history, been admired by millions, and analyzed by thousands of scholars. They are buying

temporal thickness—layer upon layer of meaning accumulated over decades [

28].

This psychological attachment makes collectors hold even when the market falls. When Picasso prices fell 30% in the 2008 crash, serious collectors did not panic sell—because they did not buy the object for short-term profit. They bought because they felt a responsibility to guard this historical object, paying off their "debt" to the cultural heritage they inherited.

7.2. NFT and Ahistorical Speculation

NFT holders, conversely, possess no ontological debt toward the object they purchased. Bored Ape #3749 has no history—it was created in 2021, has no narrative depth, no scholarly interpretation, no embeddedness in art historical fabric.

When someone bought a Bored Ape for $200,000 at the 2022 peak, the motivation was:

- 1.

Financial speculation: Hope that the price would go higher.

- 2.

Status signaling: Showing they were an "early adopter" and wealthy.

- 3.

FOMO: Fear of missing out on a viral trend.

- 4.

Community access: Membership to an exclusive Discord server.

Nothing in these motivations creates psychological stickiness—attachment making someone hold when prices drop. When the Bored Ape price dropped 50%, there was no reason to hold—no historical "debt" to repay, no cultural responsibility to fulfill. The logical response was: sell before it drops further.

This is why NFT holder behavior differs so vastly from fine art collectors. NFT holders are renters of attention, not custodians of history.

7.3. Temporality and Narrative: The Unconscious Contract

Bourdieu argued that symbolic capital requires temporal investment—it cannot be bought instantly. An artist builds a reputation over decades; an institution builds legitimacy over generations.

In psychoanalytic terms, we could say serious collectors enter an unconscious contract with the object they buy. The contract reads: "I will guard this object, care for it, preserve it, and eventually pass it to the next generation (via museum donation or family inheritance). In exchange, this object gives me a sense of participation in something larger than myself—in the continuity of human history."

This unconscious contract is what makes art collecting different from asset speculation. It is the reason serious collectors often say they feel like "temporary custodians" rather than "owners" of the work they possess.

NFTs cannot create this unconscious contract because the object has no narrative past and there is no reason to believe it will have a narrative future. It exists in the eternal present of the hype cycle, where it is relevant today, forgotten tomorrow.

7.4. Comparative Cases: Artists Who "Repented"

Instructive are cases where NFT artists or projects tried to gain institutional legitimacy—essentially, "repented" and returned to the "Church."

Case 1: Beeple at Christie’s

The Beeple sale at Christie’s (2021) was a watershed moment—it was an attempt to gain institutional consecration. Christie’s, as a 250+ year old institution with clear apostolic succession in the art auction world, provided borrowed legitimacy to NFTs.

However, notably, post-Christie’s sale, Beeple failed to fully integrate into the art world establishment. He did not gain major blue-chip gallery representation. Museums did not acquire his work for permanent collections. Art critics largely ignored him or wrote with skepticism.

Why? Because one auction sale is not enough—apostolic succession requires sustained engagement with institutions. Beeple performed the equivalent of a "one-night stand" with the art institution, not the long-term "marriage" required for full legitimacy.

Case 2: Refik Anadol at MoMA

Contrast with Refik Anadol, a digital artist with a proper institutional pedigree. Anadol holds an MFA from UCLA, has exhibited extensively in museums and biennials, and his works have been collected by major institutions. When MoMA commissioned Anadol for an AI-generated art installation in 2022, this was legitimate consecration—because Anadol already possessed apostolic succession.

Interestingly: although Anadol also creates NFTs, he is perceived very differently from "NFT artists" like Beeple. He is a "digital artist" who happens to use blockchain as one medium—not an "NFT bro" trying to enter the art world.

Lesson

The lesson from these cases: technology (blockchain) cannot bypass the process of institutionalization. One cannot "hack" legitimacy with viral marketing or celebrity endorsement. Institutional consecration requires sustained performance of seriousness—participation in established field rituals, submission to institutional judgment, and acceptance that legitimacy is a gift given by others, not something self-declared.

8. Implications: The Future of Digital Art

8.1. Three Possible Scenarios

Based on our analysis, there are three possible trajectories for digital art and NFTs:

Scenario 1: Full Institutionalization ("The Orthodox Path")

In this scenario, a small fraction of the most "serious" NFTs and digital art are gradually adopted by traditional institutions. Museums begin collecting selectively, not based on hype but based on critical weight built through scholarship. University art programs teach digital art history with the same rigor as traditional media. A new generation of critics and curators emerges with proper training in digital aesthetics.

This is already happening on a small scale—museums like LACMA and Centre Pompidou have started careful and critically grounded NFT collecting programs. However, the process will be slow—requiring 10-20 years for full integration.

Scenario 2: Parallel Ecosystem ("The Schism")

In this scenario, NFT art and traditional art remain separated indefinitely—like the Eastern Orthodox Church and Catholic Church after the Great Schism of 1054. Each has its own institutions, standards, and audiences.

The NFT ecosystem develops its own institutions of legitimacy—perhaps virtual museums, serious critical publications on crypto art, and educational programs. However, this remains separate from the traditional art world and does not compete for the same prestige.

This is the most likely scenario in the medium term. Platforms like SuperRare or Art Blocks have attempted to build quality criteria and curatorial standards, essentially creating "mini-cathedrals" within the crypto ecosystem.

Scenario 3: Permanent Marginalization ("The Failed Reformation")

In the most pessimistic scenario, NFT art remains permanently marginalized—perceived as a historical curiosity or speculative bubble that never developed serious artistic legitimacy.

This is the fate of many "art movements" that loudly proclaimed revolution but were later forgotten—like Stuckism or the Kitsch Movement. They made noise in their time but failed to gain institutional traction and finally faded into irrelevance.

Our data suggests this is an increasingly likely scenario if there is no fundamental change in how the NFT ecosystem operates.

8.2. Requirements for Sustainable Legitimacy

If digital artists and projects wish to achieve lasting value, our analysis suggests they must:

1. Build Critical Infrastructure

The NFT ecosystem needs equivalents of Artforum, October Journal, or Art in America—publications engaging seriously with aesthetic and conceptual dimensions of the work, not just financial performance. This requires:

Critics with proper training in art history and aesthetic theory.

Peer-reviewed journals publishing scholarship on digital art.

Books and monographs placing work in broader art historical contexts.

2. Build Educational Lineage

Digital art requires pedagogical institutionalization via serious MFA programs, tenured faculty positions at universities, and curricula teaching digital aesthetic history and theory with rigor.

This is happening at some institutions (UCLA, Parsons, RCA London), but is still marginal compared to traditional media.

3. Cultivate Temporal Patience

Most challenging: the ecosystem must abandon the culture of instant gratification and rapid flipping. Legitimacy requires long-term commitment, where artists must be willing to build careers over decades, collectors must be willing to hold for years or decades, and institutions must be willing to bet on work that may not appreciate financially for a long time.

This is fundamentally incompatible with crypto culture driven by "number go up" mentality and quarterly thinking.

4. Submit to Institutional Judgment

Most controversial: digital artists must accept they cannot completely bypass institutions. They must be willing to have their work judged by curators, critics, and scholars with expertise—and accept rejection as part of the process.

"Democratization" in the sense of "everyone can call themselves an artist" produces no legitimacy. Legitimacy requires differentiation—acknowledgment that not all works are equal in merit, and that assessment requires expertise cultivated through training and experience.

8.3. The Paradox of Disintermediation

Our analysis reveals a fundamental paradox: the attempt to "democratize" art by eliminating intermediaries (curators, galleries, critics) actually destroys the mechanism that creates value itself.

This is not because intermediaries "add" value in a simple economic sense. But because they are carriers of tradition—they are the ones maintaining continuity between past and present, curating selection from overwhelming noise, providing interpretive frameworks making works meaningful.

Without intermediaries, we do not get a "pure" relation between artist and collector. We get chaos—a sea of competing claims without standards to distinguish merit, marketing spectacle without substance, and volatility without anchor.

This is a broader lesson beyond art:

institutions exist for a reason. They are often imperfect, sometimes corrupt, occasionally sclerotic. But they serve functions that cannot easily be replaced by technology or market forces alone [

18]. Attempts to "disrupt" institutions without understanding these functions are destined to fail.

9. Limitations and Counter-Arguments

Before drawing final conclusions, it is important to acknowledge several substantive limitations of this analysis and engage seriously with objections that can be raised against the theoretical framework developed. Intellectual honesty requires identifying where our arguments might overreach or where alternative interpretations have merit.

9.1. Methodological and Geographical Limitations

9.1.1. Anglo-American Bias

This analysis focuses almost exclusively on the dynamics of the Anglo-American art market, specifically institutions in New York, London, and some Western European cities. This is a serious limitation for several reasons:

First, the NFT market in Asia operates with fundamentally different logic. In South Korea, for example, NFTs are deeply integrated with the idol economy, a system where celebrity fan clubs have sophisticated organizational structures and a collecting culture established before blockchain. When K-pop idols like BTS or Blackpink launch NFTs, they are not trying to bypass institutions, but leveraging existing institutional structures in the entertainment industry.

In Japan, the NFT market is more connected to otaku culture and a long tradition of collecting limited edition merchandise, trading cards, and figurines. In this context, NFTs are not "heresy" but an evolutionary step in established cultural practices. Virtual idol Hatsune Miku, for example, has possessed strong cultural legitimacy since 2007, long before NFTs, and her NFTs do not claim to disrupt the system but merely extend an existing platform.

In China, before stricter crypto bans, NFTs (or "digital collectibles") were regulated and mediated by authorized platforms like Ant Group’s Whale, essentially creating state-sanctioned intermediation. This is a very different model from the anarcho-capitalist ethos of Western NFT culture.

Second, art institutions in non-Western contexts have different histories of legitimacy. Post-colonial museums in Africa, Asia, and Latin America often struggle with the legacy of art canons imposed by colonial powers. For artists in these contexts, the desire to bypass Western-dominated institutional structures is not purely about financial disruption, but has a legitimate decolonial dimension.

Museums that historically excluded or marginalized non-Western art forms do not possess the same moral authority to claim apostolic succession. If the "Church" itself is built on structural exclusion, then "Heresy" might be a justified rebellion, not merely misguided disruption.

9.1.2. Implications for Argument

This geographical limitation means our claim about the "universal failure" of NFTs needs qualification. It is more accurate to say: "In the context of the Anglo-American art market with highly developed and relatively stable institutional structures, NFTs failed to achieve legitimacy because they attempted a wholesale bypass of institutional structures without adequate substitute."

In other contexts, where institutional structures are more fluid, where digital culture is already more dominant, or where historical grievances against established institutions are more acute, dynamics might differ.

Revised Claim: The apostolic succession framework remains useful for explaining legitimacy mechanisms, but the necessity of specific Western art institutions as gatekeepers is not universal. Alternative lineages of legitimacy might be possible in different cultural contexts.

9.2. Temporal Limitations: Is This Premature Failure?

9.2.1. Historical Precedents Take Decades

A serious critique of this paper is that analysis based on 2021-2024 data might be historically premature judgment. Art media history shows that institutional legitimacy often requires generations, not just years.

Consider the following trajectories:

Photography (1839 invention): Viewed as merely mechanical reproduction until late 19th century. Only fully accepted as fine art in 1940s-1950s after MoMA established Photography Department. Timeline: 100 years.

Film/Cinema (1895): Initially considered carnival entertainment. Not considered "art" until auteur theory in 1950s-1960s and establishment of Film Studies programs. Timeline: 60 years.

Video Art (1960s): Nam June Paik and other pioneers struggled for decades. Museum acquisitions and serious scholarship not substantial until 1980s-1990s. Timeline: 30 years.

Street Art/Graffiti: Basquiat died 1988 but only fully legitimated posthumously. Banksy remains partially outside institutional validation despite massive market success. Timeline: ongoing, 40+ years.

If we accept this historical pattern, then declaring NFTs "failed" after only 3-4 years is premature judgment. Perhaps NFTs are in a stage analogous to photography in the 1850s or video art in the 1970s—controversial and rejected by the establishment, but eventually to be legitimated.

9.2.2. Generational Shift

More fundamentally: this paper does not adequately consider intergenerational value perception transformation.

Gen Z (born 1997-2012) and Gen Alpha (born 2013-) are digital natives in a way qualitatively different from Millennials. For these generations:

Virtual ownership feels "real," spending thousands on Fortnite skins, Roblox items, or game cosmetics without questioning the legitimacy of this ownership.

Social media validation is a genuine form of capital, where Instagram likes, TikTok views, and Discord roles are meaningful currency.

Meme culture is a legitimate form of cultural production, where they do not need museum validation to consider something "significant."

In 20-30 years, when this generation becomes the dominant force in the art market, museum curators, and academic positions, perhaps they will bring a fundamentally different epistemology regarding what constitutes legitimate art. NFTs currently seen as failed experiments might be retrospectively consecrated as important early moments in digital culture.

9.2.3. Revised Temporal Framework

Given historical precedents, our conclusion needs reframing with humbler epistemology:

"As of 2024, NFTs have not succeeded in building institutional legitimacy within the traditional art world context. Whether this represents permanent failure or merely delayed —analogous to photography or video art eventually legitimated—will depend on: (1) whether future generations develop different value epistemologies accommodating digital native forms, (2) whether institutional structures themselves transform to include alternative lineages, and (3) whether the NFT ecosystem develops critical infrastructure currently absent."

The prudent conclusion is: failure to date is factual; permanent failure is speculative.

9.3. Counter-Arguments: Steelmanning the Opposition

Academic rigor requires engaging with the strongest versions of arguments we critique, not merely straw-man versions. Here are serious objections that can be raised against our framework:

9.3.1. Objection 1: Decentralization as Moral Imperative

Argument from NFT Advocates:

"This analysis treats institutional gatekeeping as a neutral quality control mechanism, but ignores that institutions are sites of structural power. Museums historically excluded women artists, artists of color, and non-Western art forms. Gallery systems favor artists with connections and wealthy backgrounds. Critics and curators are dominated by educated white elites reproducing their own class taste.

NFTs offer a genuinely democratizing alternative: anyone can mint, anyone can collect, and the market decides value—not elite curators. If this produces ’chaos’, it is a small price to break the monopoly of cultural gatekeepers."

Partial Concession:

This critique has substantial weight. Traditional art institutions do have a terrible record on inclusion. Statistics show:

Women artists comprise only 15% of major museum collections (Guerrilla Girls data).

Artists of color severely underrepresented until very recently.

Non-Western art often ghettoized in "ethnographic" departments.

The apostolic succession framework we developed does not inherently justify existing institutions—it only explains legitimacy mechanisms. If existing institutions are structurally exclusive, creating alternative lineages is a morally justifiable project.

Where This Objection Fails:

However, the problem is that the NFT ecosystem did not truly succeed in creating a more equitable alternative. Data shows:

NFT wealth extremely concentrated, where top 10% holders own 85% of value.

"Democratization" largely benefited already-wealthy crypto early adopters.

Barriers to entry (gas fees, technical knowledge) excluded many communities supposedly being "liberated."

So the valid critique is: NFTs claimed democratization but delivered plutocracy with different elites. This is not an argument defending the old system, but an argument that technology alone does not solve structural inequality.

9.3.2. Objection 2: Museums as Colonial Gatekeepers

Argument:

"’Apostolic succession’ is a Eurocentric concept assuming Western institutional history as universal norm. For artists from Africa, Asia, or Indigenous communities, ’legitimacy’ from British Museum or MoMA is morally compromised—these institutions built wealth through colonial extraction and still hold looted artifacts.

Why should artists from former colonies seek ’blessing’ from institutions that historically stole and misrepresented their cultures?"

Strong Concession:

This is a devastating critique if our framework claims universality. Colonial legacy of major Western museums is undeniable:

British Museum: Elgin Marbles, Benin Bronzes—looted artifacts.

Metropolitan Museum: Disputed origins for countless Egyptian, African, and Asian objects.

Museum ethnographic collections: Objects acquired through coercion or unfair exchange.

For artists from cultures subjected to this extraction, refusing institutional validation is an ethical stance, not merely naive anti-institutionalism.

Nuanced Response:

However, the solution is not elimination of all institutional structures, but transformation and decolonization. Some museums are actively involved in repatriation, collection diversification, and hiring curators from underrepresented communities.

Alternative lineages can and must be built—but they still require some form of institutional structure to create lasting legitimacy. These could be museums led by Indigenous curators, funded by non-Western foundations, and operating with different epistemic frameworks—but still institutional, still possessing standards, still maintaining temporal continuity.

NFTs’ error was not in challenging Western institutions, but in assuming that no institutions were needed at all.

9.3.3. Objection 3: Speed as Feature, Not Bug

Argument:

"Your framework assumes ’temporal depth’ and ’historical continuity’ are required for value. But this is slow culture bias. Digital culture operates on different temporality—viral memes have immense cultural impact despite existing only for weeks. TikTok trends shape millions of lives despite rapid turnover.

Why should digital art be judged by oil painting standards requiring centuries to appreciate? Perhaps rapid cycles, remix culture, and ephemeral value are legitimate aesthetic modes for the digital age."

Interesting Challenge:

This is a philosophically sophisticated objection. It challenges fundamental assumptions about the relationship between value and duration.

It is true that digital culture has created powerful but ephemeral forms. Memes shape political discourse. Viral videos launch careers. Ephemeral Snapchat stories are meaningful to billions.

Where Framework Still Holds:

However, the crucial distinction is between:

Memes can be highly influential without needing to be sold as investments. Viral content can be meaningful without claiming millions in value. The problem with NFTs is not that they are ephemeral—the problem is they claimed lasting economic value (as investments) while operating on ephemeral logic.

If NFTs were framed as "digital experiences" or "participatory moments" rather than "assets," rapid turnover would not be an issue. But once you claim this JPEG is a "store of value" or "better than gold," you invite comparison with other stores of value—and that is where temporal depth becomes critical.

9.4. Synthesis: Toward Reform, Not Restoration

The apostolic succession framework developed in this paper is an analytical tool, not a normative prescription. It explains how legitimacy functions in existing systems—not arguing that existing systems are perfect or must remain unchanged.

What we critique about NFTs is not the desire for change, but the naivete in assuming technology can eliminate the need for social trust mechanisms, or that "decentralization" automatically produces equity.

Productive Path Forward requires:

- 1.

Institutional Reform: Transforming existing institutions to be more inclusive, less Eurocentric, and more responsive.

- 2.

Alternative Lineages: Building new institutions with different values—but still institutions with standards, continuity, and accountability.

- 3.

Hybrid Models: Combining technological innovation (blockchain transparency) with social innovation (new, more democratic legitimacy forms).

- 4.

Epistemological Humility: Acknowledging that value epistemologies can differ across cultures and generations without assuming total relativism.

The goal is not to defend every aspect of the status quo, but to learn from why certain social structures exist and what functions they serve—so when we transform them, we do not accidentally destroy capacities that turn out to be essential.

10. Conclusion: From Heresy to Orthodoxy?

10.1. Argument Recapitulation

This paper has argued that the failure of NFTs (2021-2023) is fundamentally a failure of institutionalization, not a technology or market condition failure. By synthesizing Bourdieu’s cultural production theory with the theological concept of apostolic succession, we have demonstrated that:

- 1.

Art value is relational, not intrinsic, produced through institutional consecration rituals, not inherent in the object itself.

- 2.

Legitimacy requires genealogy, as artists and works acquire value through association with already legitimate institutions, forming consecration chains analogous to apostolic succession.

- 3.

Technology cannot replace sociology, because Blockchain can verify ownership but cannot create trust requiring temporal investment, critical discourse, and educational infrastructure.

- 4.

Ontological debt is key, where serious collectors have psychological attachment transcending financial calculation because they feel they participate in historical continuity. NFT speculators lack this.

- 5.

Institutions are tradition carriers, where attempts to eliminate intermediaries destroy the mechanism creating lasting value.

10.2. Beyond NFT: Implications for "Disruption"

Lessons from NFT failure extend beyond the art market. In an era where "disruption" is celebrated and intermediaries demonized, this case is a sobering reminder of technological solutionism’s limits.

Not all inefficient or gatekeeping institutions are purposeless. Often, they serve functions invisible until removed—legitimacy functions, quality control, knowledge transmission, and standard maintenance requiring generations to build but destroyable in months.

Silicon Valley ideology emphasizing "move fast and break things" assumes anything broken can be rebuilt better using technology. The NFT experiment shows this is not always true—some "broken" things (institutional authority, critical infrastructure, temporal patience) cannot be easily reconstructed.

10.3. Future Prospects

Do digital art and NFTs have a legitimate future? Our answer is: yes, but only if they are willing to "repent" and engage with institutions.

This does not mean full submission or abandonment of technological innovation. But it requires:

Humility: Recognition that creating lasting value requires more than technology—it requires participation in tradition.

Patience: Acceptance that legitimacy cannot be hacked or shortcut—it requires decades of sustained work.

Seriousness: Commitment to developing critical discourse, educational programs, and standards transcending hype cycles.

Some corners of the digital art ecosystem show signs of this—platforms like Feral File (curated by Casey Reas), Verse (focusing on generative art with critical standards), and institutions like Rhizome (curating digital art since 1996) represent models of how digital art can develop legitimacy through institutional engagement rather than institutional rejection.

10.4. Final Reflection: Cathedrals Take Time

This paper’s title—"Cathedral Without Apostles"—captures the essential problem: You cannot build a cathedral overnight, and you cannot declare yourself an apostle. Medieval cathedrals took centuries to build, with generations of craftsmen contributing. Apostles must be trained, ordained, and connected to a lineage returning to the founding moment.

The NFT ecosystem tried to build a "cathedral" in months and declare "apostles" via Twitter followers. This is a fundamental category error—confusion between attention and authority, between hype and legitimacy, between price and value.

Digital art can have a future—but only if practitioners are willing to learn from history, engage with institutions, and commit to long-term infrastructure building creating lasting trust.

Technology gives us new tools, but it cannot give us tradition—that must be cultivated, transmitted, and honored across time. A cathedral cannot exist without its apostles, and apostles cannot ordain themselves.