1. Introduction

The era of channel coding began with linear block codes, in which codewords are represented as vectors in an

n-dimensional space generated by a set of linearly independent rows of a generator matrix. Classical decoding methods for such codes, including syndrome-based lookup decoding and bounded-distance decoding, identify the most probable error pattern consistent with the received syndrome [

1]. While these techniques are optimal for short block lengths, their computational complexity grows exponentially with the code dimension or the number of parity constraints, which makes them impractical for moderate and long codes [

2]. Maximum-likelihood (ML) decoding provides optimal error performance, but its complexity of

makes it impractical for most real-time applications.

Iterative message-passing decoding, most notably belief propagation (BP) and the sum-product algorithm, offers a scalable alternative by performing probabilistic inference on the Tanner-graph representation of a code [

3,

4]. The computational complexity of message passing grows linearly with the number of graph edges, and when applied to sparse parity-check matrices, it enables decoding performance that approaches the Shannon limit [

5]. These properties have established message-passing decoding as a core technique in modern communication systems, including wireless standards, optical transmission, and data storage.

Despite these advances, conventional coded systems fundamentally rely on the transmission of redundancy, and the channel code rate is necessarily smaller than one. Improvements in minimum distance or iterative convergence typically require additional parity symbols, which reduces the effective throughput. In this work, an alternative operating principle is considered. Only the uncoded information bits are transmitted over the channel, while the receiver alone embeds these k bits into a higher-dimensional linear block code and performs decoding entirely within that code space. From the channel perspective, the system operates at unit rate (), while the receiver continues to benefit from the algebraic and graphical structure of a full block code.

The main contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

The transmission information rate is maximized by eliminating explicit redundancy over the channel while preserving structured decoding at the receiver.

Strong decoding performance can be achieved by increasing the receiver-side reliability parameters and code dimension, while keeping the number of transmitted information bits fixed.

At the receiver, the observed k uncoded bits are interpreted as the systematic portion of a block code and embedded into the corresponding code space. Appropriately valued log-likelihood ratios (LLRs) are assigned to the parity positions, and parallel message-passing decoding is performed across all information-bit hypotheses. For each hypothesis, a single BP iteration refines the soft estimate, and an orthogonality-based energy criterion—computed through the correlation between the estimate and the corresponding codeword representation—determines the most probable candidate.

A key aspect of the proposed receiver lies in the correct interpretation of the performance shifts observed in the bit-error-rate (BER) curves. In the proposed framework, a single compensation mechanism is inherently present and must be carefully accounted for.

This effect originates from the LLRs assigned to the parity positions. From a theoretical point of view, since parity symbols are not physically transmitted through the channel and are fully known to the receiver, their corresponding LLRs should be infinite in magnitude. In practice, however, finite parity LLR values are employed due to numerical stability considerations.

According to the standard LLR definition

and assuming normalized constellation values with

, assigning nonzero (and increasingly large) parity LLR magnitudes corresponds to assuming a fixed and reduced effective noise variance for the parity positions. This assumption does not modify the physical channel noise, but it introduces an artificial reliability model inside the decoder.

As a consequence, increasing the parity LLR magnitude produces two simultaneous effects on the BER curves: first, a horizontal shift along the axis caused by the change in the assumed noise variance; and second, an improvement in hypothesis separation within the code space, which results in near-vertical waterfall behavior of BER performance. Since the horizontal displacement is purely model-induced, it must be compensated in order to enable a fair and physically meaningful interpretation of the decoding performance.

Once the artificial performance shift introduced by the parity LLRs is properly compensated, a clear insight emerges: increasing the parity LLR leads to systematic improvements in decoding performance. For sufficiently large parity LLR values, the proposed decoding strategy can exceed the performance of conventional iterative decoders applied to the same code structure. Although the framework suggests that increasingly strong error performance is theoretically attainable by further raising the parity LLR magnitude, practical implementations impose an upper limit due to numerical effects such as finite precision and message saturation.

These observations demonstrate that reliable decoding can be achieved without transmitting redundancy or employing high-dimensional channel coding at the transmitter. Instead, robustness is achieved through enhanced receiver-side processing and carefully controlled parity reliability, illustrating an alternative design philosophy for high-rate communication over additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) channels.

The authors use this space to illustrate how a solid research idea can emerge from an early-stage approach. The present work builds on a previous study reported in [

7], which had clear limitations but provided important insight that motivated the development of the approach presented here. A similar process can be observed in the authors’ earlier work on decoding over multipath channels, where initial receiver designs based on parallel matched filters were after months unconsciously refined into more effective solution, i.e., the one was reported in [

8].

The rest of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the system model and notation.

Section 3 presents the proposed receiver architecture, including LLR construction and the orthogonality-based selection rule.

Section 4 analyzes the computational complexity.

Section 5 reports simulation results.

Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. System Model and Preliminaries

2.1. Linear Block Code Representation

We consider a binary linear block code

of length

n and dimension

k, denoted as a

code. The code can be specified by a generator matrix

and a parity-check matrix

such that

We focus on systematic generator matrices of the form

where

is the

identity matrix and

P is a

parity matrix. A corresponding systematic parity-check matrix is

The minimum Hamming distance is denoted by , and the Tanner graph associated with H is a bipartite graph with variable nodes corresponding to codeword symbols and check nodes corresponding to parity equations. The girth of the Tanner graph is the length of its shortest cycle; in this work we are interested in codes whose Tanner graphs have girth at least six.

2.2. Channel Model and LLRs

The transmitter sends

k uncoded information bits

These bits are binary-phase shift-keying (BPSK) modulated as

and are transmitted over an AWGN channel:

No parity symbols are transmitted; the effective information rate over the channel is therefore

.

At the receiver, LLRs are computed for each received symbol:

These

k LLRs will be embedded into a higher-dimensional code structure by introducing parity LLRs.

2.3. Noise-Variance Interpretation

In traditional coded communication, all

n symbols of a codeword are transmitted over the channel and independently corrupted by noise. Since only

k of these symbols correspond to information bits, the effective bit energy is spread across

n channel uses, which leads to the well-known expression

In the proposed architecture, however, only the

k information bits are transmitted through the AWGN channel, while decoding is performed in an

n-dimensional code space using attached LLRs for the

parity positions. Because only

k bits suffer noise but

n bits participate in the decoding, the correct noise-variance relation becomes

Equivalently,

is the variance that would be used if all

n positions were physically transmitted through the channel.

3. Proposed Receiver and Parallel Decoding

3.1. Receiver-Only Code Embedding

The receiver is equipped with a

linear block code

with known matrices

and

. The

k observed bits are interpreted as the systematic part of a codeword, while the

parity positions are not transmitted over the channel. Instead, the receiver forms an

n-dimensional LLR vector

where:

for are the channel-derived LLRs in (8);

for are LLRs assigned to the parity positions according to the chosen design rule and operating SNR.

Parity columns of the codebook should provided to the receiver, so that the parity structure is known at the receiver side.

3.2. Parity LLR Construction

For each parity position

, the receiver assigns a synthetic soft observation that models the presence of a parity bit without transmitting it over the channel. Let

denote the parity bit required by the

code, and let

be its corresponding BPSK constellation value.

Properly valued LLRs are assigned to the parity positions. This assignment enables the parity bits of the code to be involved in message passing without transmitting any redundancy over the channel.

From a theoretical point of view, since parity symbols are not physically transmitted through the channel and are fully known to the receiver through the code structure, their corresponding LLRs should ideally have infinite magnitude. In practice, however, finite parity LLR values are employed due to numerical stability limitations in message-passing implementations.

Assigning finite, nonzero LLR magnitudes to the parity positions does not force the physical channel noise variance toward zero. Instead, according to the standard LLR definition in

and assuming normalized constellation values with

, increasing the parity LLR magnitude corresponds to assuming a smaller

effective noise variance at the decoder. This reduction is introduced by the modeling assumption and does not reflect any actual improvement in the physical channel conditions. Consequently, the resulting BER curves experience a systematic horizontal shift given by

which must be compensated before any meaningful performance comparison is made.

As the parity LLR magnitude increases, competing hypotheses in the code space become more clearly separated, improving discrimination among candidate codewords. This enhanced separation yields as a sharper, near-vertical waterfall region in the BER curves. At the same time, the artificial reliability introduced by large parity LLR values results in a horizontal shift of the BER curves along the axis. This shift is therefore a direct consequence of the decoding model rather than a physical noise reduction and must be totally compensated before interpretation of the results.

3.3. Parallel Message-Passing Across Hypotheses

All

possible information vectors are considered,

where each hypothesis

determines a candidate codeword

For each hypothesis, a single iteration of message passing is executed on the Tanner graph using the initialized LLR vector

. The resulting soft estimate

is evaluated through an orthogonality-based metric defined directly with respect to the candidate codeword. Specifically, the following energy functional is computed:

The final decision is obtained by selecting the hypothesis that minimizes this energy:

and the decoded information vector is given by

. This yields an ML-like selection mechanism where parallel message passing refines each hypothesis prior to metric evaluation.

4. Complexity Considerations

A naive ML decoder over all

hypotheses has complexity

. A standard BP decoder for a length-

n code, when all

n symbols are transmitted, requires iterative processing, with complexity on the order of

where

I is the number of iterations and

E is the number of edges in the Tanner graph, typically scaling linearly with

n.

In the proposed architecture, two observations fundamentally alter the complexity profile. First, the number of hypotheses

is fixed and small (e.g.,

), and second,

each hypothesis requires only a single message-passing iteration. Thus, the total computational effort is dominated by

where

denotes the cost of one BP iteration on graph. Since

is constant for fixed

k, the resulting complexity scales essentially linearly with

n.

In contrast, a conventional BP decoder operating on the same code length requires many iterations to converge—often tens, hundreds, or even thousands—yet still cannot achieve the decoding performance obtained by the proposed parallel-hypothesis method with a single iteration per hypothesis.

Modern hardware platforms can support hundreds of parallel BP processors, making the proposed -hypothesis, single-iteration structure computationally feasible and highly competitive for short-block, high-reliability scenarios.

5. Simulation Setup and Illustrative Results

In this section, we outline the simulation framework used to evaluate the proposed receiver.

5.1. Code Family

We consider a family of codes with:

fixed information dimension ;

block length ;

minimum distance value are 3;

systematic generator matrix of the form ;

parity-check matrix constructed via a progressive edge-growth (PEG) like procedure;

sparse parity-check structure (low-density parity-check (LDPC) type), with limited column and row weights;

Tanner graph girth at least six (no four-cycles);

no zero rows or zero columns in H.

These code is generated using a PEG style construction to ensure large girth and good graph connectivity [

6].

5.2. Channel and Decoder Parameters

For each code and each SNR point, the simulation procedure is as follows:

Random information vectors are generated.

The bits are BPSK-modulated and transmitted over an AWGN channel with noise variance

corresponding to an effective transmission rate of

.

LLRs for the information positions are computed from the received symbols.

Since the parity bits are known at the receiver, their corresponding LLRs should, in principle, be assigned infinite magnitude. Nevertheless, the parity LLRs are varied from 25 to 100 to select an optimal value that yields the best BER performance.

Parallel message-passing decoding is executed over all information-bit hypotheses, with each hypothesis refined through a single BP iteration.

An orthogonality-based metric is computed for each candidate, and the hypothesis minimizing this metric is selected as the decoded information word.

BER are estimated over a large number trials, i.e., 1000 packet errors at every SNR point.

5.3. Results and Interpretations

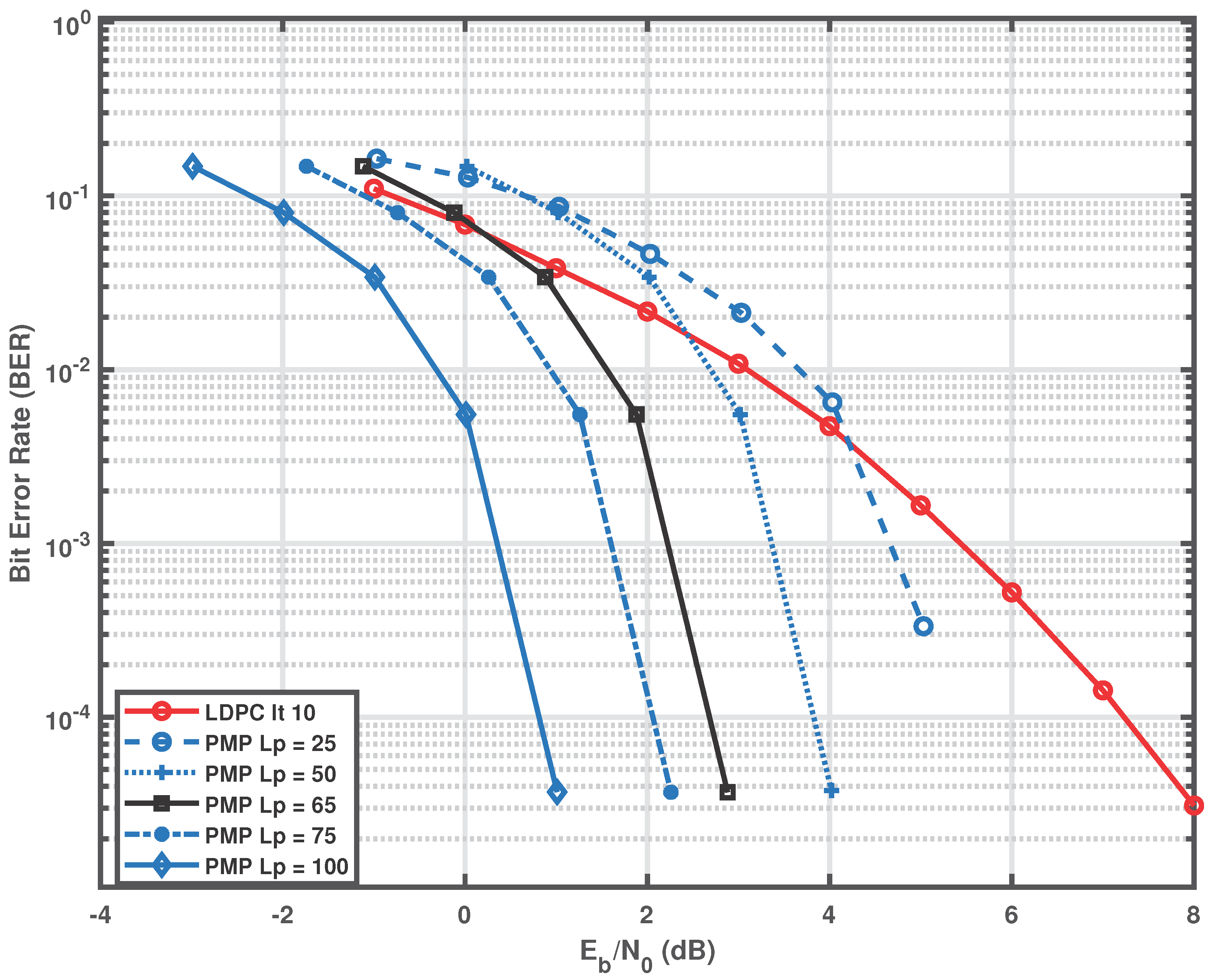

Figure 1 presents the BER performance of the conventional LDPC decoder for the

code and the proposed receiver for different magnitudes of the parity LLRs in the range

dB. The curve labeled

LDPC corresponds to the standard iterative LDPC decoder operated with its maximum allowed number of decoding iterations. The curves labeled

PMP correspond to the proposed parallel message-passing (PMP) decoder for different parity LLR magnitudes.

Each PMP curve has been horizontally shifted according to the compensation term given in in order to account for the artificial reliability introduced by the parity LLR assignment. As the parity LLR magnitude increases, the decoding performance of the proposed receiver consistently improves. Around a parity LLR magnitude of approximately 65 dB, the proposed scheme approaches the performance of the conventional LDPC decoder. Further increasing the parity LLR magnitude results in decoding performance that exceeds what can be achieved by the conventional LDPC decoder, even when it operates with a large number of iterations. It is also observed that beyond a parity LLR magnitude of approximately 65 dB, the shape of the BER curve remains unchanged and only undergoes a horizontal shift along the SNR axis. This behavior indicates that further performance improvement cannot be achieved by increasing the parity LLR alone, and instead requires increasing the code length while keeping the information dimension k fixed.

6. Conclusions

This paper investigated a receiver-side decoding approach for uncoded data transmission, aiming to maximize the information transmission rate by eliminating channel redundancy. By embedding the k transmitted information bits into a higher-dimensional linear block code at the receiver and assigning controlled LLRs to the parity positions, reliable data recovery was achieved without employing any channel-side coding.

The proposed architecture relies on one-shot parallel message-passing across all information-bit hypotheses, combined with an orthogonality-based energy selection rule. For a fixed linear block code, the decoding behavior was analyzed as a function of the parity-bit LLR magnitude. It was shown that increasing the parity LLR introduces artificial reliability that enhances hypothesis separation in the code space, resulting in a waterfall region in the BER curves. At the same time, this artificial reliability induces a systematic horizontal shift of the BER curves, which does not correspond to a physical reduction of channel noise and must therefore be compensated for a fair performance comparison.

After proper compensation, the results demonstrate that increasing the parity LLR consistently improves decoding performance, up to a point where the proposed scheme can outperform conventional iterative LDPC decoding. In principle, arbitrarily strong decoding performance can be approached by further increasing the parity LLR magnitude; however, the maximum usable value is limited by numerical instabilities in practical message-passing implementations.

Overall, the presented results show that strong decoding performance can be achieved without transmitting redundancy and without employing high-dimensional coding at the transmitter. Instead, reliability is obtained through receiver-side processing and controlled parity reliability, highlighting a fundamentally different design paradigm for high-rate communication over AWGN channels.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.; methodology, A.M.; software, A.M.; validation, A.M.; formal analysis, A.M.; investigation, A.M.; resources,, A.M.; data curation,, A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M. and; writing—review and editing, A.M.; visualization, A.M.; supervision, A.M.; project administration, A.M.; funding acquisition, A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lin, S.; Costello, D.J. Error Control Coding: Fundamentals and Applications, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Blahut, R.E. Theory and Practice of Error Control Codes; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Kschischang, F.R.; Frey, B.J.; Loeliger, H.-A. Factor graphs and the sum-product algorithm. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2001, 47, 498–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, T.J.; Urbanke, R.L. Modern Coding Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MacKay, D.J.C.; Neal, R.M. Good codes based on very sparse matrices. In Cryptography and Coding; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1995; pp. 100–111. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.-Y.; Eleftheriou, E.; Arnold, D.-M. Regular and irregular progressive edge-growth Tanner graphs. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2005, 51, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirbadin, A.; Zaraki, A. Low–Complexity, Fast–Convergence Decoding in AWGN Channels: A Joint LLR Correction and Decoding Approach. Preprints 2025, 2025051199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirbadin, A.; Zaraki, A. Partial Path Overlapping Mitigation: An Initial Stage for Joint Detection and Decoding in Multipath Channels Using the Sum–Product Algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).