Submitted:

18 December 2025

Posted:

18 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- We introduce a degradation-aware modeling module to explicitly encode multi-source, multi-scale degradations as priors guiding the diffusion process.

- We propose a dual-decoder recursive generation mechanism that balances local detail restoration with global semantic consistency.

- We design a static regularization guidance strategy to stabilize structural preservation and enhance perceptual realism.

- We conduct extensive experiments on three widely used remote sensing benchmarks (UCMerced, AID), where our method consistently surpasses state-of-the-art approaches under both idealized and realistic degradations, demonstrating superior robustness, generalization, and adaptability to cross-domain scenarios.

2. Related Work

2.1. Remote Sensing Image Super-Resolution

2.2. Applications of Diffusion Models in Super-Resolution

2.3. Degradation Modeling

2.4. Regularization and Structural Consistency

3. Methodology

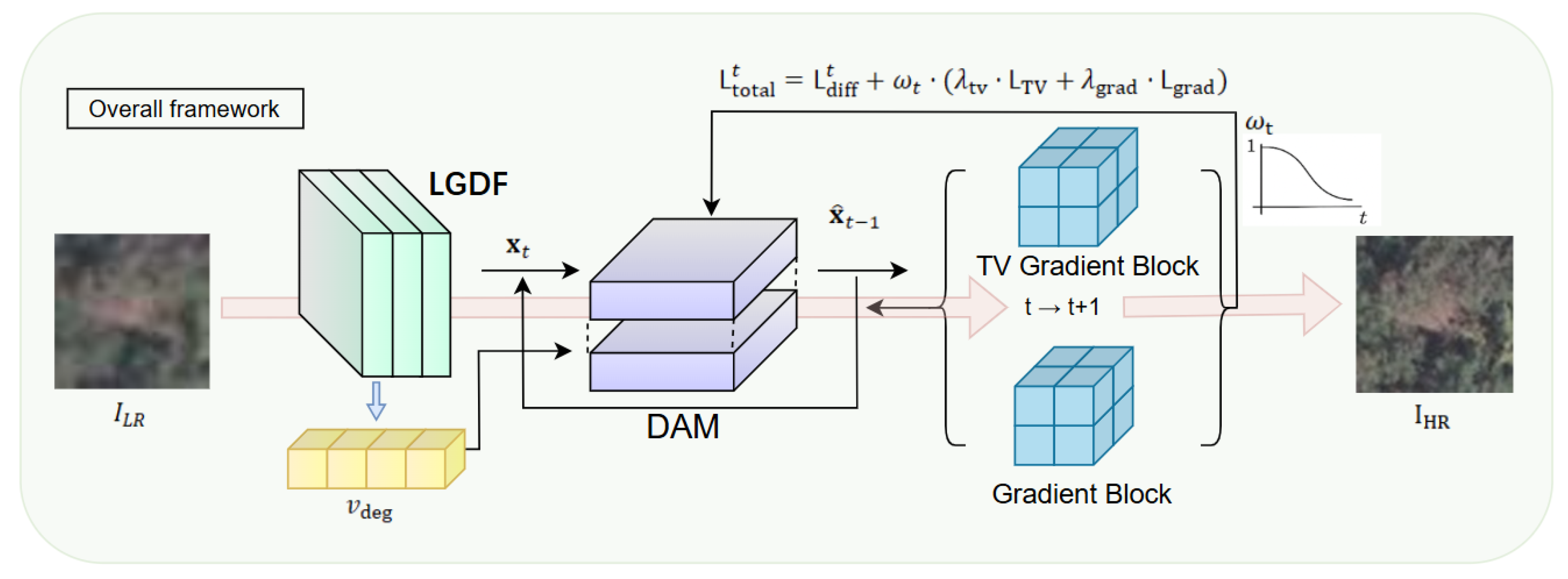

3.1. Overall Framework

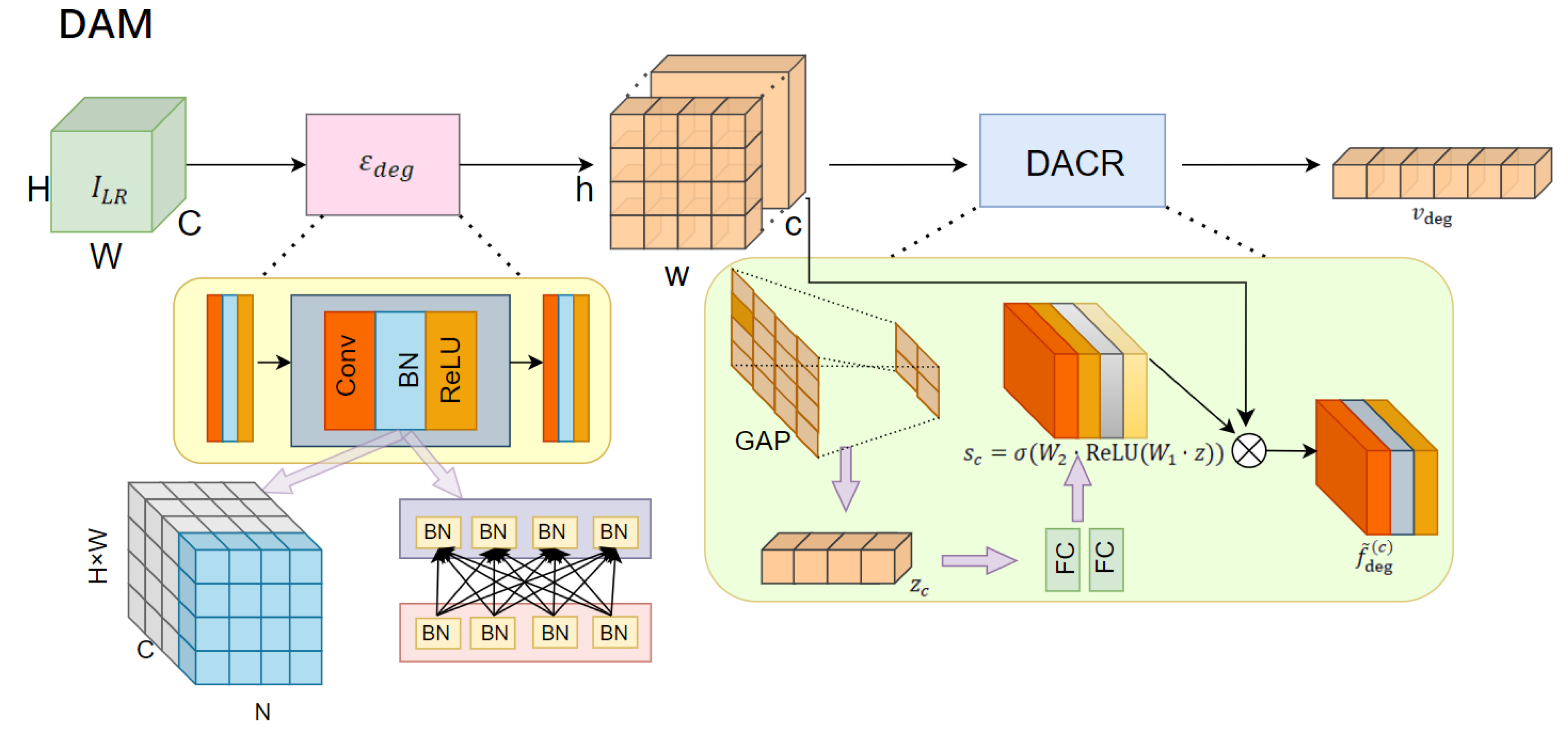

3.2. Degradation-Aware Modeling Module

3.2.1. Lightweight Feature Extractor

3.2.2. Degradation-Aware Channel Recalibration

3.2.3. Degradation-Aware Conditional Injection

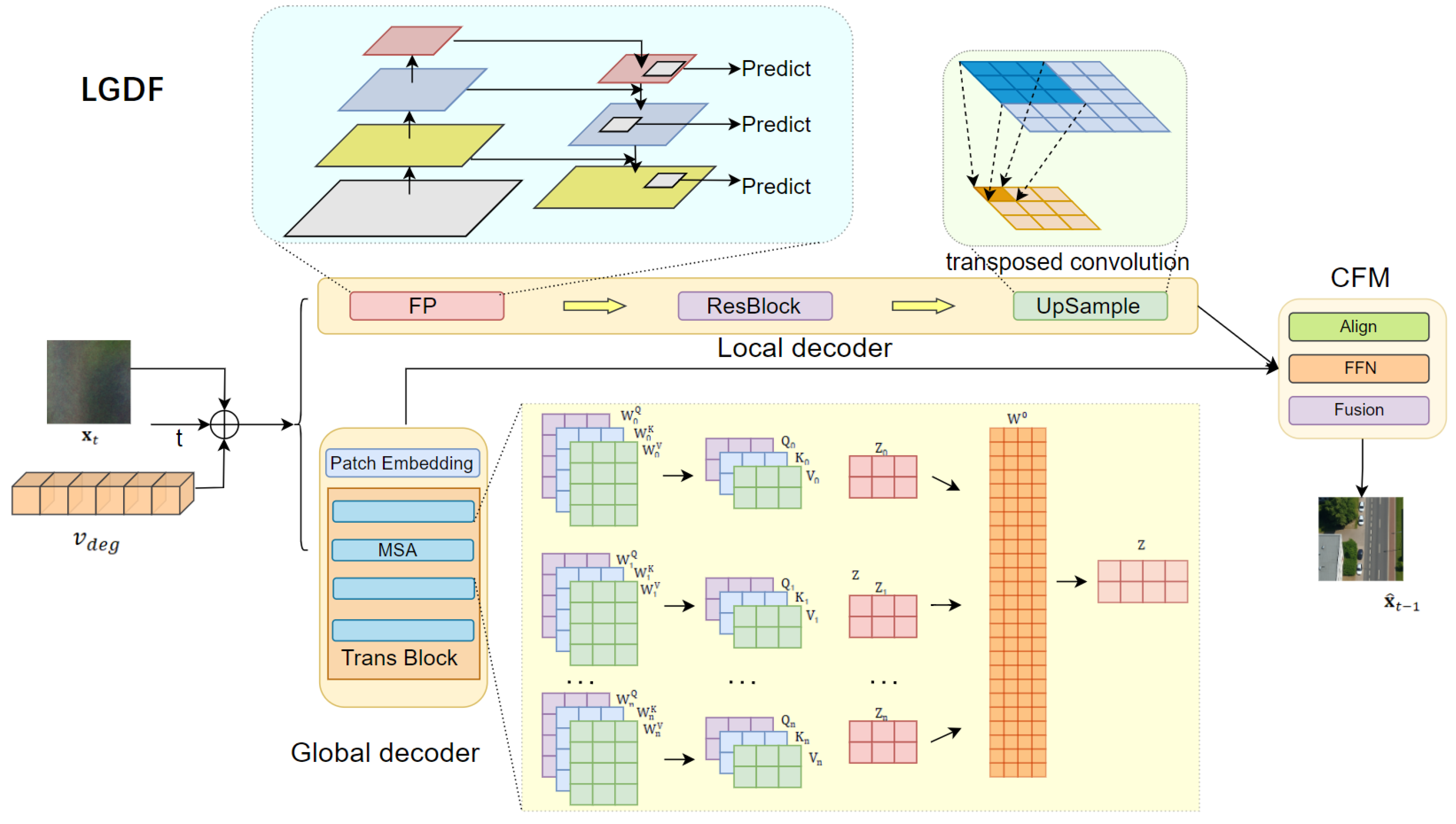

3.3. Dual-Decoder Design and Recursive Generation

3.3.1. Dual-Decoder Design

(1) Decoding Output Formulation

3.3.1.2. (2) Local Decoder

3.3.1.3. (3) Global Decoder

(4) Complementary Fusion Module

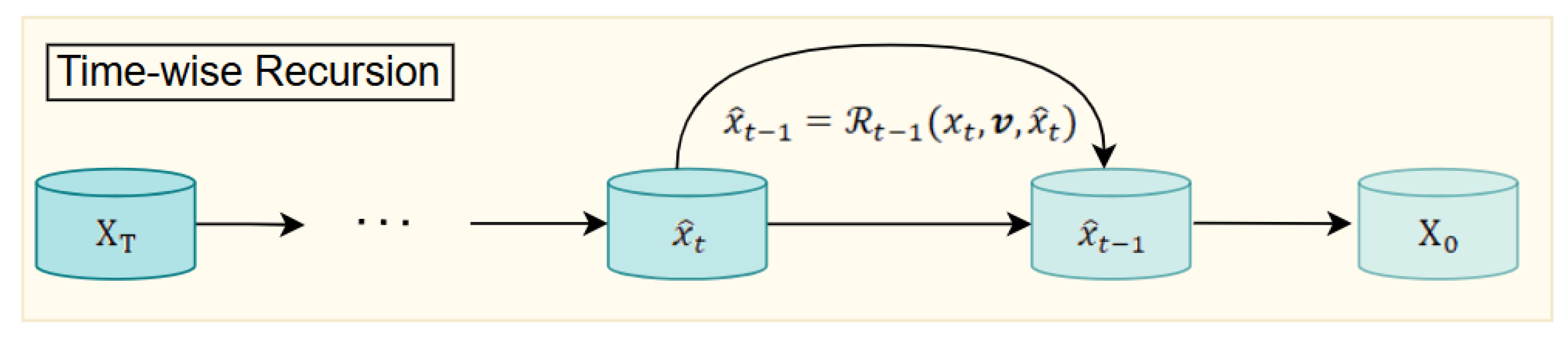

3.3.2. Recursive Generation Mechanism

(1) Time-wise Recursion

(2) Residual Correction Recursion

3.4. Static Regularization Guidance

3.4.1. Overall Loss Function

3.4.2. Total Variation Regularization

3.4.3. Gradient Consistency Loss

4. Experiment

4.1. Datasets and Evaluation Metrics

4.2. Comparison with Existing Methods

4.3. Ablation Study

4.4. Further Analysis: Robustness Under Different Degradation Levels

5. Conclusions

References

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Du, B. Deep Learning for Remote Sensing Data: A Technical Tutorial on the State of the Art. IEEE Geoscience & Remote Sensing Magazine 2016, 4, 22–40. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Qi, F.; Wan, Y. Improvements on bicubic image interpolation. Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 4th advanced information technology, electronic and automation control conference (IAEAC) 2019, Vol. 1, 1316–1320. [Google Scholar]

- Keys, R.G. Cubic convolution interpolation for digital image processing. IEEE Transactions on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing 2003, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Zhang, L.; Shi, G.; Wu, X. Image Deblurring and Super-Resolution by Adaptive Sparse Domain Selection and Adaptive Regularization. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2011, 20, 1838–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In IEEE; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Rabinovich, A. Going Deeper with Convolutions. In IEEE Computer Society; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, B.; Son, S.; Kim, H.; Nah, S.; Mu Lee, K. Enhanced deep residual networks for single image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops, 2017; pp. 136–144. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Li, K.; Wang, L.; Zhong, B.; Fu, Y. Image super-resolution using very deep residual channel attention networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 2018; pp. 286–301. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Cao, J.; Sun, G.; Zhang, K.; Timofte, R. SwinIR: Image Restoration Using Swin Transformer. In IEEE; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Cun, X.; Bao, J.; Zhou, W.; Liu, J.; Li, H. Uformer: A general u-shaped transformer for image restoration. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022; pp. 17683–17693. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, G.A.; Hussain, M. A review of transformer-based models for computer vision tasks: Capturing global context and spatial relationships. arXiv 2024. arXiv:2408.15178. [CrossRef]

- Saxena, D.; Cao, J. Generative adversarial networks (GANs) challenges, solutions, and future directions. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial networks. Communications of the ACM 2020, 63, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, W.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Guo, L.; Chau, L.P.; Liu, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Kot, A.C.; Wen, B. SinSR: Diffusion-Based Image Super-Resolution in a Single Step. Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2024, 25796–25805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Yuan, S.; Luo, B.; Chen, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, W.; Zheng, J.; Fu, H. Building bridges across spatial and temporal resolutions: Reference-based super-resolution via change priors and conditional diffusion model. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024; pp. 27684–27694. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Jiang, K.; He, J.; Jin, X.; Zhang, L. EDiffSR: An Efficient Diffusion Probabilistic Model for Remote Sensing Image Super-Resolution. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2024, 62, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yue, J.; Xia, S.; Ghamisi, P.; Xie, W.; Fang, L. Diffusion models meet remote sensing: Principles, methods, and perspectives. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Yi, J.; Guo, J.; Song, Y.; Lyu, J.; Xu, J.; Yan, W.; Zhao, J.; Cai, Q.; Min, H. A review of image super-resolution approaches based on deep learning and applications in remote sensing. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 5423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Li, Z.; Xia, Y.; Chen, Z. Remote sensing image super-resolution: Challenges and approaches. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE international conference on digital signal processing (DSP), 2015; IEEE; pp. 196–200. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Li, C.; Zhang, P.; Dai, X.; Xiao, B.; Yuan, L.; Gao, J. Focal attention for long-range interactions in vision transformers. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 34, 30008–30022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xu, D.; Wang, X.; Ben, G.; Zhao, Z.; Li, Z. A multi-degradation aided method for unsupervised remote sensing image super resolution with convolution neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2020, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudin, L.I.; Osher, S.; Fatemi, E. Nonlinear total variation based noise removal algorithms. Physica D: nonlinear phenomena 1992, 60, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saharia, C.; Ho, J.; Chan, W.; Salimans, T.; Fleet, D.J.; Norouzi, M. Image Super-Resolution Via Iterative Refinement. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dhariwal, P.; Nichol, A. Diffusion models beat gans on image synthesis. Advances in neural information processing systems 2021, 34, 8780–8794. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Meng, C.; Ermon, S. Denoising diffusion implicit models. arXiv arXiv:2010.02502.

- Johnson, J.; Alahi, A.; Fei-Fei, L. Perceptual Losses for Real-Time Style Transfer and Super-Resolution; Springer: Cham, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.; Saharia, C.; Chan, W.; Fleet, D.J.; Norouzi, M.; Salimans, T. Cascaded Diffusion Models for High Fidelity Image Generation. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2022, 23, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Z.; Wang, J.; Loy, C.C. Resshift: Efficient diffusion model for image super-resolution by residual shifting. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36, 13294–13307. [Google Scholar]

- Nichol, A.Q.; Dhariwal, P. Improved denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2021; pp. 8162–8171. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Xie, L.; Dong, C.; Shan, Y. Real-esrgan: Training real-world blind super-resolution with pure synthetic data. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021; pp. 1905–1914. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Liu, X.; Zeng, B.; Xu, S.; Li, Y.; Luo, X.; Liu, J.; Zhen, X.; Zhang, B. Implicit diffusion models for continuous super-resolution. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2023; pp. 10021–10030. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Liang, J.; Van Gool, L.; Timofte, R. Designing a practical degradation model for deep blind image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021; pp. 4791–4800. [Google Scholar]

- Haris, M.; Shakhnarovich, G.; Ukita, N. Deep back-projection networks for super-resolution. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018; pp. 1664–1673. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Xie, J.; Zhang, L.; Meng, D.; Wong, K.Y.K. Blind image super-resolution with elaborate degradation modeling on noise and kernel. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022; pp. 2128–2138. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Dong, X.; Xu, Q.; Yang, J.; An, W.; Guo, Y. Unsupervised degradation representation learning for blind super-resolution. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2021; pp. 10581–10590. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, W.S.; Huang, J.B.; Ahuja, N.; Yang, M.H. Deep laplacian pyramid networks for fast and accurate super-resolution. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017; pp. 624–632. [Google Scholar]

- Zamir, S.W.; Arora, A.; Khan, S.; Hayat, M.; Khan, F.S.; Yang, M.H. Restormer: Efficient transformer for high-resolution image restoration. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022; pp. 5728–5739. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, R.; Mou, L.; Zhang, L.; Fu, H.; Zhu, X.X. Real-world remote sensing image super-resolution via a practical degradation model and a kernel-aware network. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2022, 191, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, T.; Li, J.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, Y. Single-image super resolution of remote sensing images with real-world degradation modeling. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Nie, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Sun, J.; Zhu, M.; Lu, J.; Pan, Q. Multi-Degradation Super-Resolution Reconstruction for Remote Sensing Images with Reconstruction Features-Guided Kernel Correction. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Sun, T.; Yu, S.; Wu, S. Global Prior-Guided Distortion Representation Learning Network for Remote Sensing Image Blind Super-Resolution. Remote Sensing 2025, 17, 2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Ni, N.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L. Blind super-resolution for remote sensing images via conditional stochastic normalizing flows. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.07751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, L. Efficient and degradation-adaptive network for real-world image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, 2022; Springer; pp. 574–591. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Liang, J.; Van Gool, L.; Timofte, R. Designing a practical degradation model for deep blind image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021; pp. 4791–4800. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, R.; Mou, L.; Zhang, L.; Fu, H.; Zhu, X.X. Real-world remote sensing image super-resolution via a practical degradation model and a kernel-aware network. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2022, 191, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aybar, C.; Montero, D.; Contreras, J.; Donike, S.; Kalaitzis, F.; Gómez-Chova, L. SEN2NAIP: A large-scale dataset for Sentinel-2 Image Super-Resolution. Scientific Data 2024, 11, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Nie, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Sun, J.; Zhu, M.; Lu, J.; Pan, Q. Multi-degradation super-resolution reconstruction for remote sensing images with reconstruction features-guided kernel correction. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Mou, L.; Zhang, L.; Fu, H.; Zhu, X.X. Real-world remote sensing image super-resolution via a practical degradation model and a kernel-aware network. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2022, 191, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Tang, X.; Xie, J.; Song, W.; Mo, F.; Gao, X. Spatio-temporal super-resolution reconstruction of remote-sensing images based on adaptive multi-scale detail enhancement. Sensors 2018, 18, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shao, Z.; Lu, T.; Huang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zuo, X. Lightweight remote sensing super-resolution with multi-scale graph attention network. Pattern Recognition 2025, 160, 111178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, X. Ddsr: Degradation-aware diffusion model for spectral reconstruction from rgb images. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Mou, L.; Zhang, L.; Fu, H.; Zhu, X.X. Real-world remote sensing image super-resolution via a practical degradation model and a kernel-aware network. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2022, 191, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xia, M.; Weng, L.; Hu, K.; Lin, H. Dual encoder–decoder network for land cover segmentation of remote sensing image. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2023, 17, 2372–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.P.; Su, W.Y. Recursive high-resolution reconstruction of blurred multiframe images. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 1993, 2, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, K.; Chen, G.; Tan, X.; Zhang, L.; Dai, F.; Liao, P.; Gong, Y. Geospatial object detection on high resolution remote sensing imagery based on double multi-scale feature pyramid network. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Dang, D. Mixed hierarchy network for image restoration. Pattern Recognition 2025, 161, 111313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleissaee, A.A.; Kumar, A.; Anwer, R.M.; Khan, S.; Cholakkal, H.; Xia, G.S.; Khan, F.S. Transformers in remote sensing: A survey. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichol, A.Q.; Dhariwal, P. Improved denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2021; pp. 8162–8171. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Meng, C.; Ermon, S. Denoising diffusion implicit models. arXiv arXiv:2010.02502.

- Zafar, A.; Aftab, D.; Qureshi, R.; Fan, X.; Chen, P.; Wu, J.; Ali, H.; Nawaz, S.; Khan, S.; Shah, M. Single stage adaptive multi-attention network for image restoration. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2024, 33, 2924–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Kim, J.; Mccann, M.T.; Klasky, M.L.; Ye, J.C. Diffusion posterior sampling for general noisy inverse problems. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.14687. [Google Scholar]

- Nichol, A.Q.; Dhariwal, P. Improved denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2021; pp. 8162–8171. [Google Scholar]

- Nichol, A.Q.; Dhariwal, P. Improved denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2021; pp. 8162–8171. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, M.K.; Shen, H.; Lam, E.Y.; Zhang, L. A total variation regularization based super-resolution reconstruction algorithm for digital video. EURASIP Journal on Advances in Signal Processing 2007, 2007, 074585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Rao, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, C.; Lu, J.; Zhou, J. Structure-preserving super resolution with gradient guidance. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020; pp. 7769–7778. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Newsam, S. Bag-of-visual-words and spatial extensions for land-use classification. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 18th SIGSPATIAL international conference on advances in geographic information systems, 2010; pp. 270–279. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, G.S.; Hu, J.; Hu, F.; Shi, B.; Bai, X.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Lu, X. AID: A benchmark data set for performance evaluation of aerial scene classification. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2017, 55, 3965–3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jähne, B. Digital image processing; Springer, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh, H.R.; Bovik, A.C. Image information and visual quality. IEEE Transactions on image processing 2006, 15, 430–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scale | Method | UCMerced | AID |

|---|---|---|---|

| EDSR | 32.14 / 0.918 / 0.112 / 0.025 / 2.0 | 31.02 / 0.912 / 0.125 / 0.028 / 2.1 | |

| RCAN | 32.48 / 0.923 / 0.108 / 0.023 / 2.1 | 31.30 / 0.917 / 0.120 / 0.026 / 2.2 | |

| SwinIR | 32.60 / 0.925 / 0.106 / 0.022 / 1.9 | 31.40 / 0.919 / 0.118 / 0.025 / 2.0 | |

| Uformer | 32.35 / 0.922 / 0.109 / 0.024 / 2.0 | 31.25 / 0.916 / 0.121 / 0.027 / 2.1 | |

| SinSR | 32.55 / 0.924 / 0.107 / 0.023 / 2.0 | 31.38 / 0.918 / 0.119 / 0.026 / 2.0 | |

| RefDiff | 32.50 / 0.923 / 0.108 / 0.023 / 2.0 | 31.35 / 0.917 / 0.120 / 0.026 / 2.1 | |

| EDiffSR | 32.58 / 0.924 / 0.107 / 0.022 / 1.9 | 31.39 / 0.918 / 0.119 / 0.025 / 2.0 | |

| Ours | 33.12 / 0.932 / 0.098 / 0.020 / 1.8 | 32.01 / 0.926 / 0.107 / 0.022 / 1.8 | |

| EDSR | 30.50 / 0.870 / 0.140 / 0.033 / 2.1 | 29.45 / 0.858 / 0.155 / 0.035 / 2.2 | |

| RCAN | 30.80 / 0.875 / 0.135 / 0.031 / 2.2 | 29.70 / 0.862 / 0.150 / 0.033 / 2.3 | |

| SwinIR | 31.00 / 0.878 / 0.132 / 0.030 / 2.0 | 29.85 / 0.865 / 0.148 / 0.032 / 2.1 | |

| Uformer | 30.75 / 0.873 / 0.136 / 0.032 / 2.1 | 29.65 / 0.860 / 0.151 / 0.034 / 2.2 | |

| SinSR | 30.95 / 0.876 / 0.134 / 0.031 / 2.0 | 29.80 / 0.863 / 0.149 / 0.033 / 2.1 | |

| RefDiff | 30.90 / 0.875 / 0.135 / 0.031 / 2.1 | 29.75 / 0.862 / 0.150 / 0.033 / 2.1 | |

| EDiffSR | 30.97 / 0.876 / 0.134 / 0.030 / 2.0 | 29.82 / 0.863 / 0.149 / 0.032 / 2.1 | |

| Ours | 31.55 / 0.888 / 0.125 / 0.028 / 1.9 | 30.20 / 0.875 / 0.138 / 0.030 / 1.9 | |

| EDSR | 28.90 / 0.820 / 0.170 / 0.038 / 2.2 | 27.80 / 0.805 / 0.185 / 0.040 / 2.3 | |

| RCAN | 29.30 / 0.825 / 0.165 / 0.036 / 2.3 | 28.20 / 0.810 / 0.180 / 0.038 / 2.4 | |

| SwinIR | 29.45 / 0.828 / 0.162 / 0.035 / 2.1 | 28.35 / 0.813 / 0.178 / 0.037 / 2.2 | |

| Uformer | 29.20 / 0.823 / 0.166 / 0.036 / 2.2 | 28.15 / 0.808 / 0.181 / 0.038 / 2.3 | |

| SinSR | 29.40 / 0.826 / 0.163 / 0.035 / 2.1 | 28.33 / 0.811 / 0.179 / 0.037 / 2.2 | |

| RefDiff | 29.35 / 0.825 / 0.164 / 0.035 / 2.2 | 28.30 / 0.810 / 0.180 / 0.037 / 2.3 | |

| EDiffSR | 29.42 / 0.826 / 0.163 / 0.035 / 2.1 | 28.34 / 0.811 / 0.179 / 0.037 / 2.2 | |

| Ours | 30.10 / 0.838 / 0.150 / 0.032 / 1.9 | 29.05 / 0.823 / 0.163 / 0.034 / 1.9 |

| Scale | Method | UCMerced | AID |

|---|---|---|---|

| EDSR | 31.20 / 0.905 / 0.125 / 0.028 / 2.1 | 30.10 / 0.898 / 0.138 / 0.030 / 2.2 | |

| RCAN | 31.55 / 0.910 / 0.120 / 0.026 / 2.2 | 30.40 / 0.903 / 0.133 / 0.028 / 2.3 | |

| SwinIR | 31.70 / 0.913 / 0.118 / 0.025 / 2.0 | 30.55 / 0.905 / 0.131 / 0.027 / 2.1 | |

| Uformer | 31.45 / 0.911 / 0.121 / 0.027 / 2.1 | 30.35 / 0.903 / 0.134 / 0.029 / 2.2 | |

| SinSR | 31.65 / 0.912 / 0.119 / 0.026 / 2.1 | 30.50 / 0.905 / 0.132 / 0.028 / 2.1 | |

| RefDiff | 31.60 / 0.911 / 0.120 / 0.026 / 2.1 | 30.45 / 0.904 / 0.133 / 0.028 / 2.2 | |

| EDiffSR | 31.68 / 0.912 / 0.119 / 0.025 / 2.0 | 30.52 / 0.905 / 0.132 / 0.027 / 2.1 | |

| Ours | 32.70 / 0.925 / 0.105 / 0.022 / 1.9 | 31.55 / 0.916 / 0.118 / 0.024 / 1.9 | |

| EDSR | 29.45 / 0.885 / 0.142 / 0.033 / 2.2 | 28.40 / 0.872 / 0.157 / 0.035 / 2.3 | |

| RCAN | 29.80 / 0.890 / 0.138 / 0.031 / 2.3 | 28.75 / 0.877 / 0.152 / 0.033 / 2.4 | |

| SwinIR | 29.95 / 0.892 / 0.135 / 0.030 / 2.1 | 28.90 / 0.880 / 0.149 / 0.032 / 2.2 | |

| Uformer | 29.70 / 0.889 / 0.139 / 0.032 / 2.2 | 28.70 / 0.876 / 0.153 / 0.034 / 2.3 | |

| SinSR | 29.90 / 0.891 / 0.136 / 0.031 / 2.1 | 28.85 / 0.879 / 0.150 / 0.033 / 2.2 | |

| RefDiff | 29.85 / 0.890 / 0.137 / 0.031 / 2.2 | 28.80 / 0.878 / 0.151 / 0.033 / 2.2 | |

| EDiffSR | 29.92 / 0.891 / 0.136 / 0.030 / 2.1 | 28.87 / 0.879 / 0.150 / 0.032 / 2.2 | |

| Ours | 30.95 / 0.905 / 0.121 / 0.028 / 1.9 | 29.90 / 0.893 / 0.134 / 0.030 / 1.9 | |

| EDSR | 27.90 / 0.860 / 0.165 / 0.038 / 2.3 | 26.85 / 0.848 / 0.180 / 0.040 / 2.4 | |

| RCAN | 28.35 / 0.868 / 0.160 / 0.036 / 2.4 | 27.30 / 0.855 / 0.175 / 0.038 / 2.5 | |

| SwinIR | 28.50 / 0.871 / 0.157 / 0.035 / 2.2 | 27.45 / 0.858 / 0.172 / 0.037 / 2.3 | |

| Uformer | 28.25 / 0.868 / 0.161 / 0.036 / 2.3 | 27.25 / 0.855 / 0.174 / 0.038 / 2.4 | |

| SinSR | 28.45 / 0.870 / 0.158 / 0.035 / 2.2 | 27.40 / 0.857 / 0.173 / 0.037 / 2.3 | |

| RefDiff | 28.40 / 0.869 / 0.159 / 0.035 / 2.3 | 27.35 / 0.856 / 0.174 / 0.037 / 2.4 | |

| EDiffSR | 28.48 / 0.870 / 0.158 / 0.035 / 2.2 | 27.42 / 0.857 / 0.173 / 0.037 / 2.3 | |

| Ours | 29.50 / 0.882 / 0.142 / 0.032 / 1.9 | 28.45 / 0.871 / 0.155 / 0.034 / 1.9 |

| Method | DAM | LGDF | SRG | PSNR/SSIM/LPIPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base | 27.15 / 0.812 / 0.138 | |||

| Base+DAM | 27.78 / 0.823 / 0.130 | |||

| Base+DAM+LGDF | 28.05 / 0.809 / 0.123 | |||

| Base+DAM+LGDG+SRG | 28.45 / 0.837 / 0.115 |

| Method | Weak | Medium | Strong | Drop |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDSR | 29.12 | 27.65 | 25.48 | -3.64 |

| RCAN | 29.36 | 27.82 | 25.70 | -3.66 |

| SwinIR | 29.58 | 28.10 | 25.95 | -3.63 |

| Ours | 29.92 | 28.65 | 26.78 | -3.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).