1. Introduction

Since the first generation (1G), several access techniques have evolved to allow multiple users, focusing on ensuring better utilization of the spectrum. These included frequency division multiple access (FDMA), time division multiple access (TDMA), code division multiple access (CDMA), and orthogonal frequency division multiple access (OFDMA), respectively, and were adopted early on across generations 1G, 2G, 3G, and 4G [

1]. These methods, known as orthogonal multiple access (OMA), separate users by time, frequency, or code to prevent interference. OMA enables low-cost, low-complexity receiver designs; however, its dependence on orthogonal resources limits user bandwidth [

2]. As an alternative to OMA, NOMA was introduced, which allows for a greater number of users compared to OMA by increasing the receiver complexity to handle overlapping signals, making it highly suitable for Internet of Things (IoT), massive machine-type communications (mMTC), and smart city infrastructures [

3]. Intelligent Reflecting Surfaces (IRS) further add a dynamic dimension to NOMA, enabling electromagnetic wave redirection to overcome signal blockages and hence enhance link quality in Non-Line-of-Sight (NLoS) environments. IRS technology represents a flexible and convenient solution for improving wireless communication, as the deployment of IRS components can be easily done on facades, walls, and ceilings with very low power consumption [

4]. Remarkably, the IRS does not require an active RF component in its technology to process and retransmit the signal, which provides an energy-efficient solution implicitly. Structurally, the IRS is made up of three essential layers:

Metasurface Layer: This is the top layer fabricated with sub-wavelength-sized particles in a planar array for electromagnetic wave modulation.

Copper Layer: This is a layer below the metasurface that prevents the leakage of signal energy and keeps the signals within the desired paths.

Circuit Board and IRS Controller: The main circuit board is connected to the IRS controller, which is the controller that is in charge of the adaptability of the surface.

However, IRS performance heavily relies on the availability and quality of the natural signal paths, which could be seriously degraded under NLoS scenarios due to interference from obstacles that attenuate signal strength.

Similarly, EH-NOMA introduces a new level of robustness in wireless networks, particularly in challenging NLoS environments where conventional power supplies are scarce or unavailable. This capability provides relief from not only the burden of power infrastructure but also incessant and reliable network performance; hence, EH-NOMA becomes very promising for remote areas and IoT applications, which require day-to-day network uptime [

5,

6]. It enables devices to operate independently of conventional power grids, allowing for more resilient, scalable, and energy-efficient network deployments.

In such scenarios where NLoS communication dominates, the addition of IRS to EH-NOMA systems introduces a revolutionary method for mitigating the NLoS limitation and amplifying the core of NOMA [

7]. The IRS dynamically reconfigures the wireless propagation environment by establishing alternatives to virtual LoS and then compensates for the performance degradation caused by blockages.

Nevertheless, but phase shifts optimization over several IRS surfaces in real time is still a challenging and non-convex task, particularly under the joint energy and time allocation constraints. Standard optimization approaches, e.g., semidefinite programming (SDP) and alternating optimization, provide superior performance whereas are not readily applicable to real-time or large-scale scenarios because of being iterative and computationally demanding. To address these scalability limitations, machine learning (ML), and in particular, deep learning, have recently been gained attention as alternative approaches.

While a limited number of studies have explored the use of machine learning in order to optimize phase shifts in multiple-IRS systems, their work mainly focused on conventional MISO beamforming scenarios using neural networks. These approaches were designed to minimize transmit power or improve active beamforming, without addressing the complexities introduced by more advanced wireless setups. Our work, on the other hand, looks at a fundamentally different system architecture (i.e., a wireless-powered Cooperative NOMA network supported by dual IRSs). While NOMA remains a promising technology that researchers have recently focused on, several fundamental challenges remain when integrating this architecture with dual IRS systems, energy harvesting, and cooperative relaying under NLoS conditions. Current studies primarily focus on (a) Allocation using a single IRS beam or (b) Passive IRS–NOMA rate optimization. However, the following multidimensional challenges remain:

(i) To date, joint impact of EH, dual IRS, and cooperative NOMA has not been modelled in ML-based optimization at the time of this publication.

(ii) In addition, there is no prior work that learns directly from the wireless environment without supervised labels from Convex Optimization (CVX)/SDP at the time of this publication. Hence, the main contributions of the study are as follows:

NLoS Mitigation via IRS: This work proposes a novel system using a double IRS, which can dynamically reconfigure the propagation environment by effectively mitigating NLoS issues and thus providing robust communication links.

Machine Learning-based IRS Optimization: Instead of solving complex optimization problems for IRS phase shift optimization, we introduce a machine learning-based approach to predict optimal phase shifts and reduce computational complexity.

Energy Harvesting in NOMA: This energy harvesting system uses power to embed energy harvesting into the cooperative NOMA system for energy sustainability at IoT devices.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents related work on NOMA and other advanced solutions for managing Non-Line-of-Sight (NLoS) transmission challenges, along with their respective evaluation methodologies, performance benchmarks, and key findings.

Section 3 describes the Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model structure used for optimization.

Section 4 provides a comprehensive overview of the system model’s details, highlighting its components and assumptions.

Section 5 presents the numerical results, analyzing the study’s findings and providing relevant insights. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the current research work.

2. Related Work

In this section, the existing work to mitigate the challenges faced by the NLoS environments is presented. We mainly focus on the studies about IRS-NOMA, EH-NOMA, and C-NOMA in this regard.

2.1. IRS-NOMA

The IRS’s involvement in wireless networks has brought about a significant change in how non-line-of-sight (NLoS) problems are addressed. By altering how wireless signals propagate through the environment, the IRS enables precise control of scattered signals. This ensures that reflected signals reach the intended users and reduces the interference caused by others. This allows an increase in energy efficiency and spectrum use [

8].

The IRS makes the traditional NOMA system even more customizable when paired with NOMA. In contrast to conventional NOMA, which relies on fixed channel settings based on the signal environment, IRS-NOMA uses dynamic phase adjustment. These changes result in different user signal strengths, making NOMA more effective in challenging NLoS conditions. This combination helps IRS-NOMA blend into its surroundings and create stronger, more user-friendly communication [

9].

In NLoS cases, where Rayleigh and Nakagami m-paths are used, the IRS enhances system performance by creating virtual paths, similar to LoS links. For example, a study [

10] showed that IRS combined with NOMA works better than traditional IRS-OMA in networks with high interference under Nakagami-m fading, offering 20–30% higher data rates and fewer connection drops. However, existing IRS and IRS–radar studies [

8,

9,

10] typically focus on simplified single-surface setups and offline optimization, and do not consider energy-harvesting or cooperative NOMA operation under real-time constraints, which motivates the AI-driven dual-IRS C-NOMA framework proposed in this work.

2.2. Energy Harvesting Enabled NOMA

Energy harvesting is a viable option in NLoS environments where obstacles such as buildings or terrain impede signal strength and cause power loss. Devices with energy harvesting technology can control surrounding energy sources and ensure waste-free operation even in areas where traditional methods of transmission and power are unavailable [

11]. These systems enable effective communication over long distances and overcome physical obstacles.

Although energy consumption alone cannot fully solve the NLoS communication problem, integration with the NOMA system increases productivity and guarantees stable and portable operation with a wide range of applications. This connection helps address challenges such as fading and interference, while also extending the network’s operating life. Studies examining Nakagami-m and Rayleigh fading channels, which characterize NLoS conditions, consistently highlight the superior performance of EH-NOMA systems over conventional orthogonal multiple access (OMA) methods [

12].

Recent works have investigated energy-harvesting-enabled NOMA under different architectures. In [

13], a MIMO NOMA system with nonlinear energy harvesting and imperfect CSI has been analyzed, Authors derive an explicit throughput and outage expressions for a SWIPT-based relay node that harvests and forwards data to a far user. However, their model remains a single-relay downlink without intelligent reflecting surfaces or cooperative NOMA relaying across multiple hops in which they focus on analytical performance evaluation rather than real-time optimization.

On the other hand, the authors in [

14] consider secured full-duplex NOMA with energy harvesting, where an energy transmitter both powers the NOMA node and jams an eavesdropper, and secrecy/reliability metrics are derived under CSI, hardware, and SIC imperfections. Yet this work still assumes a single-cell setting with conventional RF links and no IRS-assisted NLoS mitigation or learning-based control. In the IoT context, the study in [

15] proposes an energy-harvesting buffer-aided cooperative NOMA network with relay selection based on the joint state of data and energy buffers to improve outage probability and throughput. Nevertheless, this approach captures random energy arrivals and cooperative relaying; it relies on conventional half-duplex relays without IRSs. In addition, they used simple linear EH models and did not consider joint phase-shift/beamforming optimization. Hence, existing EH-NOMA studies either focus on analytical performance or relay/parameter selection in conventional RF networks, but none address dual-IRS-assisted, EH-enabled cooperative NOMA with low-complexity AI-driven real-time phase optimization under NLoS conditions, which is the focus of this work.

2.3. Cooperative NOMA

Researchers have explored the integration of cooperative communications technology with NOMA to address the challenge of wireless channel fading, thereby enhancing wireless coverage. A cooperative NOMA in which nearby users act as relays. A method for transmitting data to more distant users is proposed in [

16]. Similarly, [

17,

18] investigated Cooperative NOMA systems in Decode-and-Forward (DF) and Amplify-and-Forward (AF) methods. They studied the system’s outage performance and Bit Error Rate under these configurations. Moving beyond Half-Duplex (HD) systems, Full-Duplex (FD) NOMA is now a strong approach. FD allows for the sending and receiving of signals at the same time, making better use of the spectrum [

19]. Studies [

20,

21,

22] showed that FD cooperative NOMA is better than HD systems, as it can achieve a

greater spectral efficiency than Half-Duplex (HD) setups. They also studied problems such as Loop Self-Interference (LSI) and its impact on system performance.

Research on cooperative NOMA systems has expanded beyond user-assisted relaying to include setups with dedicated relays. Studies indicate that systems using amplify-and-forward (AF) relays outperform Orthogonal Multiple Access (OMA) in terms of coding gain, outage performance, and throughput. Under Rayleigh fading, AF-based C-NOMA systems achieve

higher throughput than OMA, whereas DF systems reduce outage probability by

, as noted in [

23]. While initial research focuses on Rayleigh-fading channels, studies [

24,

25] extended these to Nakagami-m-fading channels and analyzed the outage probability and sum rate under this more comprehensive model, which has the property of adaptation to various fading conditions. However, all of these previous studies still consider conventional cooperative NOMA with fixed relay links and no dual-IRS assistance. Plus, they lack any adaptation of a low-complexity AI scheme for real-time phase-shift control in NLoS channels, which is exactly the scenario addressed in this work.

3. System Model

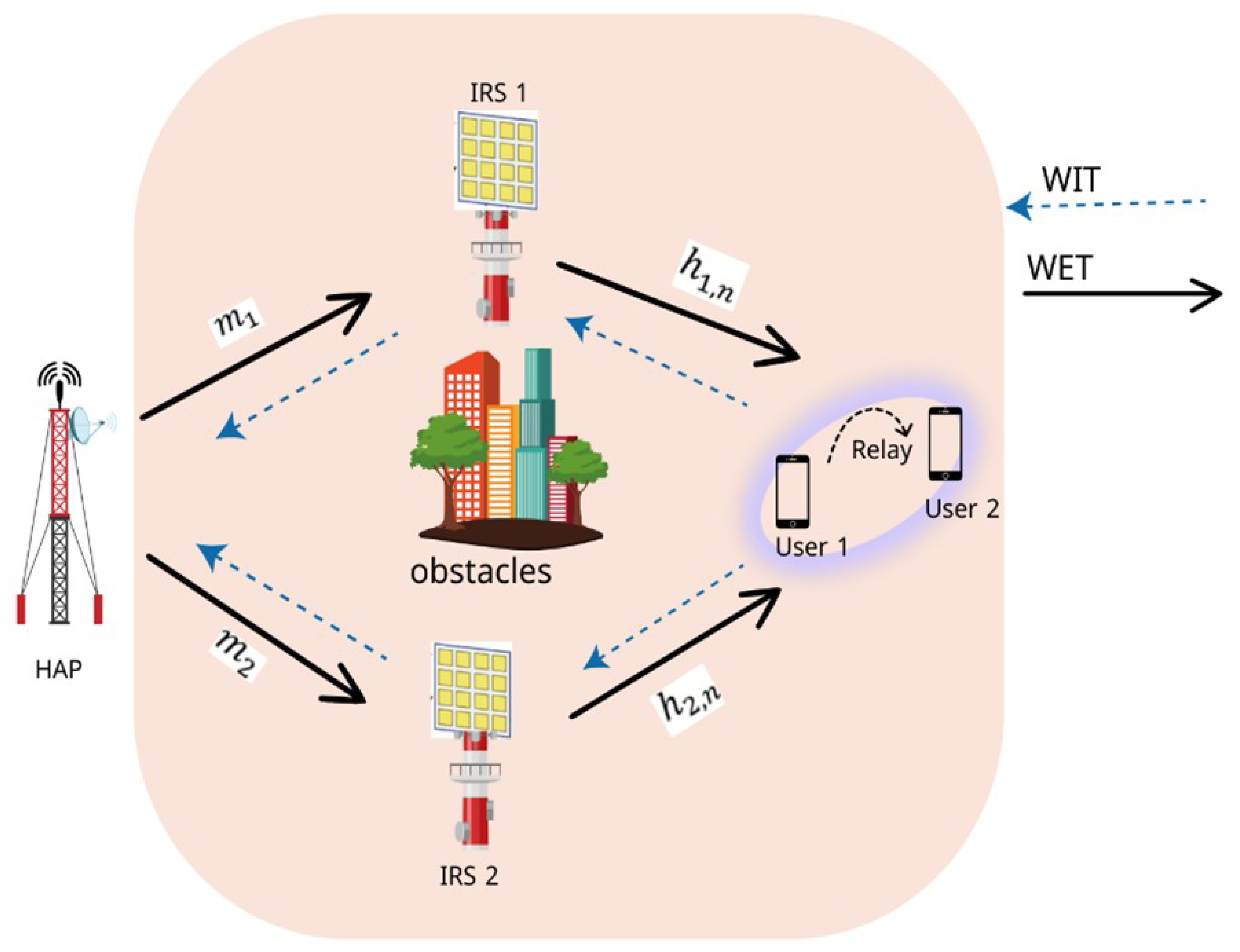

Figure 1 shows the block-level components of the proposed system.The system model incorporates advanced techniques, including NOMA for efficient resource allocation, IRS for signal propagation enhancement, and machine learning for data-driven performance predictions. Specifically, the system employs a double-IRS arrangement to mitigate NLoS issues caused by obstacles that act as passive signal relays, reflecting RF signals toward the intended users to establish reliable communication links. The presence of two IRSs significantly enhances the system’s ability to sustain communication in situations where direct pathways are inaccessible. On the user side of

Figure 1, the architecture incorporates a Signal/Power Splitting mechanism for both users,

and

, to harvest energy and process information simultaneously. We examine a wireless system that includes two intelligent reflecting surfaces (IRSs), designated IRS1 and IRS2, a hybrid access point (HAP), a near user, and a far user.

and

stand for the number of reflecting elements for IRS1 and IRS2, respectively, and both the HAP and users have single-antenna configurations for simplicity. Both wireless energy transfer (WET) and wireless information transmission (WIT) must rely on the IRSs since a physical barrier prevents direct contact between the HAP and users.

The near user’s cooperative relaying helps the remote user receive a stronger signal, further improving signal reception. There are two separate stages to the transmission process:

We assume that in a general manner. The network layout is structured to overcome signal propagation challenges caused by obstacles or deep fading in non-line-of-sight (NLoS) environments. The components of the network and their configurations are as follows:

HAP: Located at , the HAP serves as the primary source of both energy and information. It employs a single antenna and operates in a time-division manner to support the WET and WIT phases.

IRS1 and IRS2: The two IRSs are positioned at and , respectively. Each IRS is equipped with reflecting elements. These surfaces dynamically adjust their phase shifts to enhance signal strength and effectively manage interference.

Users: Randomly distributed within a square region centered at with dimensions of , reflecting typical user mobility patterns and varying channel conditions.

3.1. Statistical Modelling

The channel gains from the HAP to

and

are denoted by

and

, respectively. Similarly, the channels between

and the two users are represented by

and

. Furthermore, the channels between

and the near user and between

and the far user are denoted by

and

, respectively. We consider Rayleigh fading channels between the HAP and users with distance-based path loss to capture realistic NLoS environments, such as urban or indoor environments. The channels are considered to be quasi-static within each transmission block, which is applicable to low-mobility users and fixed IRS. We also consider perfect IRS phase alignment and unit-modulus reflection as a benchmark. The channel gain for a link at distance

d is modeled as

where

are independent Gaussian random variables. This expression characterizes small-scale Rayleigh fading in environments without a dominant line-of-sight (LoS) component, and the normalization factor

ensures that the channel gain is properly scaled according to the path-loss attenuation. Considering that the channels between the HAP–IRS links and the IRS–user links contain LoS components, they are modeled using Rician fading, expressed as

where

is the Rician factor, and

and

denote the line-of-sight and non-line-of-sight components of the channel, respectively. The effective channel gain

, which combines the direct path and the reflected paths from

and

, is given by

where the reflected contributions from both IRSs are expressed as

with

and

denoting the channel gains associated with the

nth reflecting element of

and

, respectively. The direct channel

because the HAP-to-user path is assumed to be fully blocked due to severe NLoS conditions. The terms

and

represent the phase shifts applied by the corresponding IRS elements.

The scaling by assumes that the IRS elements introduce constructive interference. This requires precise phase alignment, and , for the IRS elements. However, perfect alignment may not always be achievable due to hardware imperfections or channel estimation errors. Therefore, channel state information (CSI) is crucial, especially for practical implementations. In our system, machine learning models utilize historical channel characteristics to predict system performance under varying configurations.

The SIC is applied to decode and subtract the far user’s signal first, enabling clean decoding of the near user’s signal. The far user, being located farther away, decodes its own signal while treating the near user’s signal as interference. The SINR for the near and far users is expressed as

where

denotes the noise power. The SIC mechanism ensures that the near-user signal is decoded first, while the far-user signal is treated as interference. The transmit power

is dynamically computed as

. The terms

and

denote the effective channel gains for the near and far users, respectively, considering both direct and IRS-reflected paths. The power-allocation factors are set to

and

.

The harvested energy

, measured in joules (or milli-joules for practical applications), is given by

where

represents the energy-harvesting efficiency and

t is the allocated harvesting duration. The corresponding achievable rate is expressed as

where

denotes the communication rate in bits per second per hertz (bps/Hz).

Outage probability is a critical metric that characterizes system reliability. For a threshold

, the outage probabilities for the near and far users are defined as

The above expressions summarise the main performance metrics considered in this work, namely the harvested energy, the achievable rate, and the outage probabilities of the near and far users. Together, they capture the fundamental trade–off between energy harvesting time, transmit power, and link reliability in the proposed EH-enabled C-NOMA system. In the next subsection, we specify the system parameters and describe how these metrics are jointly improved using the proposed ML-based optimization framework.

3.2. System Parameters

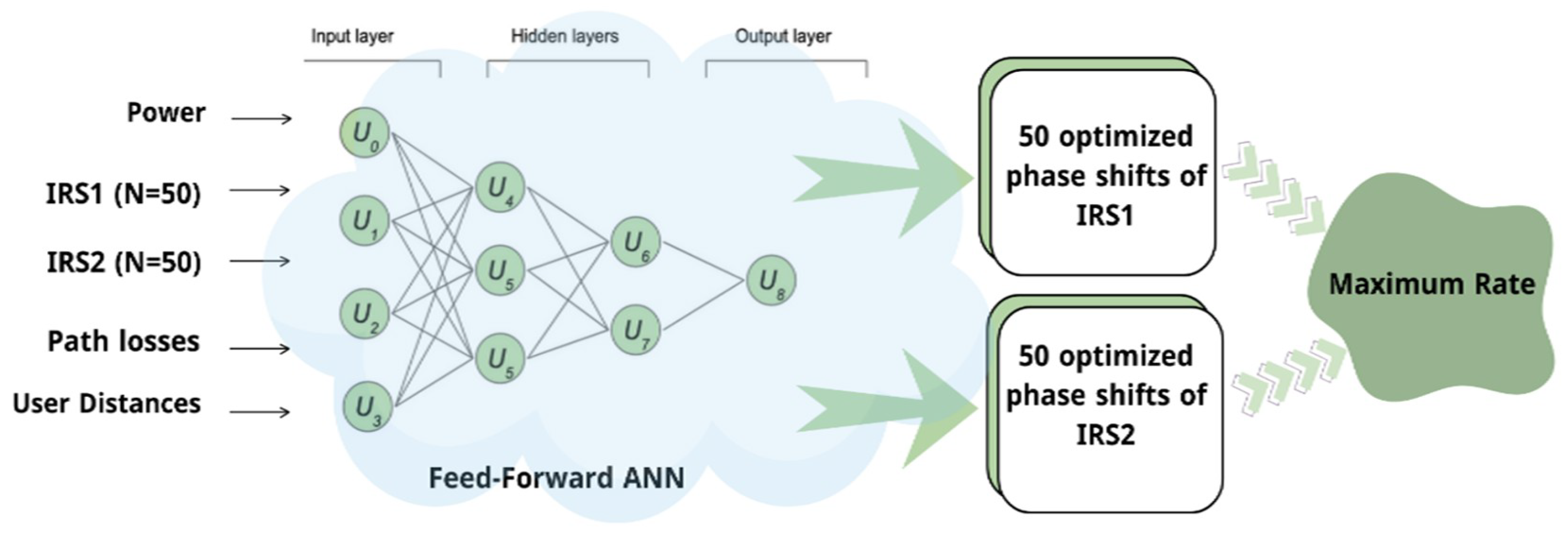

The primary objective of the proposed system is to enhance both the achievable data rate and the amount of harvested energy which can be obtained by training the model to learn the most effective IRS phase configurations. The system should adapt to varying wireless conditions to improve overall system performance. Such a learning-based approach enhances the model’s reliability and adaptability in dynamic environments.

Figure 2 shows a generic view of our optimization parameters. As shown in the figure, several comprehensive hyperparameter optimization were conducted. It can be achieved by utilizing grid search techniques in order to make sure that the model is robust and stable over different combinations of learning rates, batch sizes, dropout levels, and regularization terms. As shown in

Figure 2, the final model architecture was carefully chosen based on the computational complexity and whether the model was able to generalize well to unseen data. Furthermore, we monitored both training and validation loss curves over successive epochs to avoid overfitting.

To avoid training instability, we introduce a randomness factor of 0.3. This ensures that the generated phase-shifts will only vary within 30% of the full range. For convenience, we set the number of users

and the Noise Spectral Density

to ensure a fair and direct comparison between our ML-based method and the benchmark SDP-based approach [

7].

Increasing the number of users would require different optimization techniques and advanced machine learning models to handle IRS phase shifts, EH relay selection, and interference management efficiently, which is beyond the scope of this study. Other system settings are shown in

Table 1.

4. ML-Based Optimization Approach

4.1. Selection of ML Framework

Since jointly optimizing a large number of phase shifts in a dual-IRS system is both computationally complex and resource-intensive, we conducted a comprehensive evaluation of several algorithms in order to identify the most effective machine learning approach for our system. Among these algorithms are Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), a type of Deep Neural Network (DNN), Random Forest, Support Vector Regression (SVR), and k-Nearest Neighbour (KNN). The comparison, presented in

Figure 3, shows each model’s ability to predict average rate values and their peak performance metrics are summarized in

Table 2. Although Random Forest delivered slightly higher predictive accuracy, we ultimately selected the Multilayer Perceptron (DNN) due to its proven capacity to model complex nonlinear relationships [

26], its architectural flexibility, and its strong suitability for real-time, AI-driven IRS-based wireless systems [

27].

Also, one of our key considerations in this choice was inference efficiency. Specifically, MLPs, once trained, require minimal computational overhead during prediction, making them ideal for latency-sensitive or power-constrained environments. In contrast, Random Forests, despite its accuracy, depend on ensembles of decision trees, which increases prediction time proportionally with the number of estimators. This makes them less favourable for applications where fast, scalable, and energy-efficient performance is essential [

28]. The MLP network used has several layers, starting with 256 neurons, then 128, and finally, 64. Furthermore, Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation functions are used in our machine learning approach, as they work well for this type of optimization by introducing non-linearity into the neural network. This enables the system to model complex relationships between inputs and outputs. To ensure proper training and avoid overfitting, batch normalization is applied, and dropout layers with a rate of 0.4 are included. Additionally, L2 regularization with a factor of 0.01 is used to discourage the model from assigning excessive importance to any single feature or noise in the data.

After justifying the choice of learning model, the following subsection explains how this network is incorporated into the proposed optimization framework, including the creation of the dataset, the design of the features, and the training procedure used to learn the mapping from system parameters to near-ideal IRS phase configurations.

4.2. DNN Optimization Mechanism

4.2.1. ML Dataset and Feature Design

We generate a training dataset by simulating thousands of random IRS phase shift combinations, evaluating their performance, and selecting the best-performing configuration (i.e., with the highest rate and/or energy) for each scenario. The goal is to learn a function that maps a set of system inputs to their corresponding maximum achievable performance. The objective function can be expressed as

where

are the IRS phase shifts for both

and

,

is the achievable rate,

is the harvested energy, and

is a weighting factor balancing the two objectives. The DNN learns to make optimum phase shift vectors directly by learning to predict the IRS phase shift configurations that give the best performance (rate and/or energy) based on system parameters. It can be modeled by

where

is the input feature vector and

is the predicted performance metric (e.g., maximum rate or energy). The output layer of the DNN represents the phase shift vector

, where each

. Furthermore, the model is trained using the Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss function, which is given by

where

denotes the best observed performance (rate or energy) for the

scenario. We approached IRS phase shift optimization as a supervised regression problem. To support this, we created a dataset of 10,000 samples, where each sample represents a unique set of system conditions, including transmit power, path losses, distances, and randomly assigned IRS phase shifts, along with the resulting achievable rate. We chose these particular features as they play an important role in the signal strength shaping and overall performance in IRS-assisted NOMA systems. As seen in

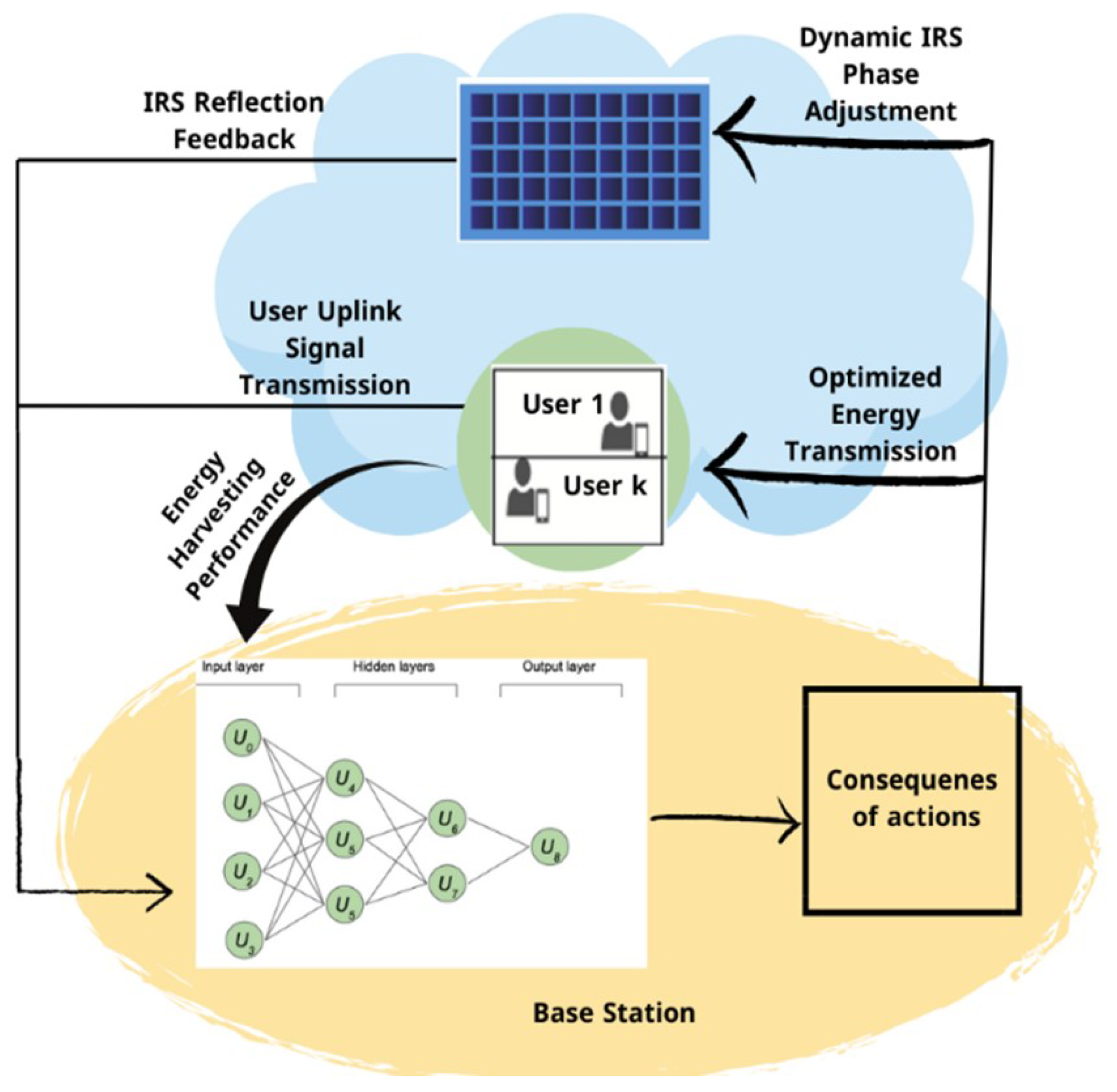

Figure 4, the DNN at the BS continuously optimizes the IRS phase shifts which are then applied to maximize the desired metric (i.e., rate and energy). The system relies on real-time user feedback and environmental conditions to dynamically adjust the IRS phase shifts.

The process begins when users send uplink signals to the base station (BS). These uplink signals contain important information such as energy harvesting status, channel conditions, and the impact of previous phase shifts. This feedback is crucial for the DNN to determine whether sufficient energy is available and to evaluate the current propagation environment, allowing for more precise phase shift adjustments.

The DNN processes the input data and generates optimized IRS phase shifts. These shifts are then transmitted to the IRS to reconfigure the reflecting surfaces, so that the incoming signals are redirected toward the users. This enhances energy harvesting and ensures users receive the maximum possible harvested power.

While IRS’s main role is applying the new optimized phase shifts sent by BS, it can also monitor the effectiveness of these adjustments. The IRS then sends reflection feedback back to BS to report key parameters such as reflected channel state, phase shift effectiveness, and environmental variations. This feedback loop is essential because it allows the DNN to refine its predictions promptly to ensure that phase shifts remain optimized even when network conditions change.

4.2.2. ML Model Complexity and Real-World Applicability

To further strengthen the proposed machine learning-based approach and address the computational limitations of traditional optimization, we analyze both the computational complexity and the performance accuracy of the DNN compared to conventional SDP methods.

Given the importance of computational efficiency in real-time IRS optimization, the DNN model was chosen because it is well-suited for practical deployment beside its strong predictive performance. As shown in

Table 3, DNN achieves significantly faster inference times compared to SDP.

This advantage stems from the fact that generating predictions with MLP primarily involves straightforward matrix operations and activation functions. In contrast, SDP relies on iterative solvers and demands substantial computational resources, whereas DNN can produce accurate results almost instantly, making it ideal for real-time wireless applications.

5. Numerical Results

In this work, we intentionally centered our comparison around three primary benchmarks: SDP, random phase assignment, and a single IRS configuration. These were made to highlight established reference methods in the area. In particular, SDP is a classic standard in the literature for IRS optimization, as it provides a classical convex optimization method as a reference when there are perfectly ideal mathematical models for the optimization problem. On the other hand, the random phase scheme and single IRS configurations are considered to provide lower-bound baselines and minimal implementation cases as discussed in the literature [

7,

29].

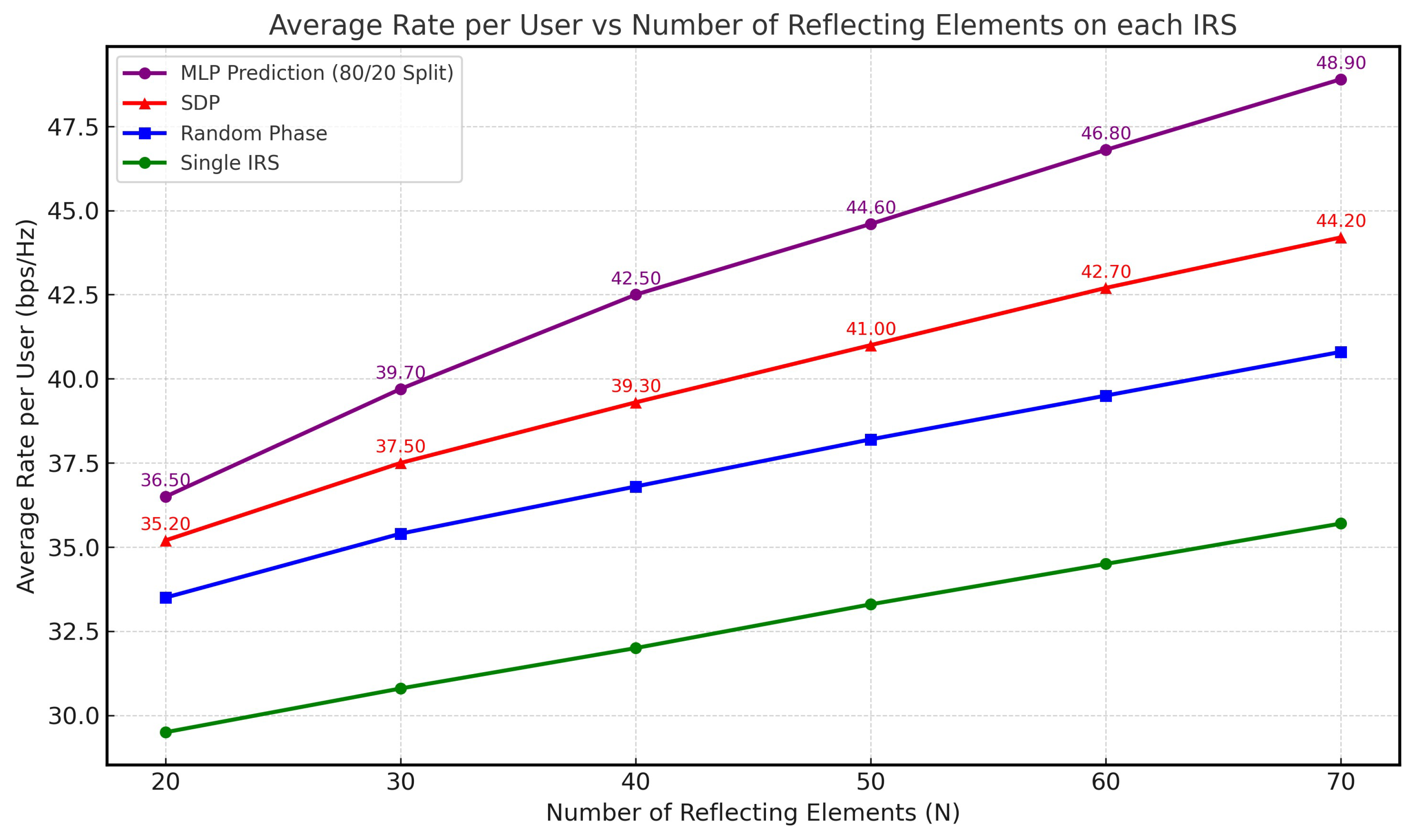

The dataset was divided into three different training and testing configurations which are (70%, 30%), (80%, 20%), and (60%, 40%). Ultimately, we consider (80%, 20%) split set since it gives better results compared to the other splits. We positioned our user at the optimal location, meters, equidistant between both IRS panels located at meters and meters, respectively. We assume that each IRS is equipped with 50 reflecting elements, i.e., . Herein, we set the path loss exponent to 2.8 for HAP-IRS links and 3.0 for IRS-user links. The power allocation factor for the near user and for the far user . The path loss constant is set as .

Figure 5 illustrates the sum rate versus the number of reflecting elements (

N) for each IRS. The results indicate that all cases exhibit an increasing trend as

N grows, demonstrating that a higher number of reflecting elements enhances system performance. Our proposed deep neural network (DNN) approach demonstrates empirically competitive or superior performance compared to all benchmark methods, highlighting the strength of machine learning compared to traditional optimization techniques, especially in handling complex, high-dimensional optimization problems with non-convex constraints. In contrast, the random phase shift strategy and the single IRS configuration produce the lowest performance due to their limited signal enhancement capabilities and the absence of coherent beamforming.

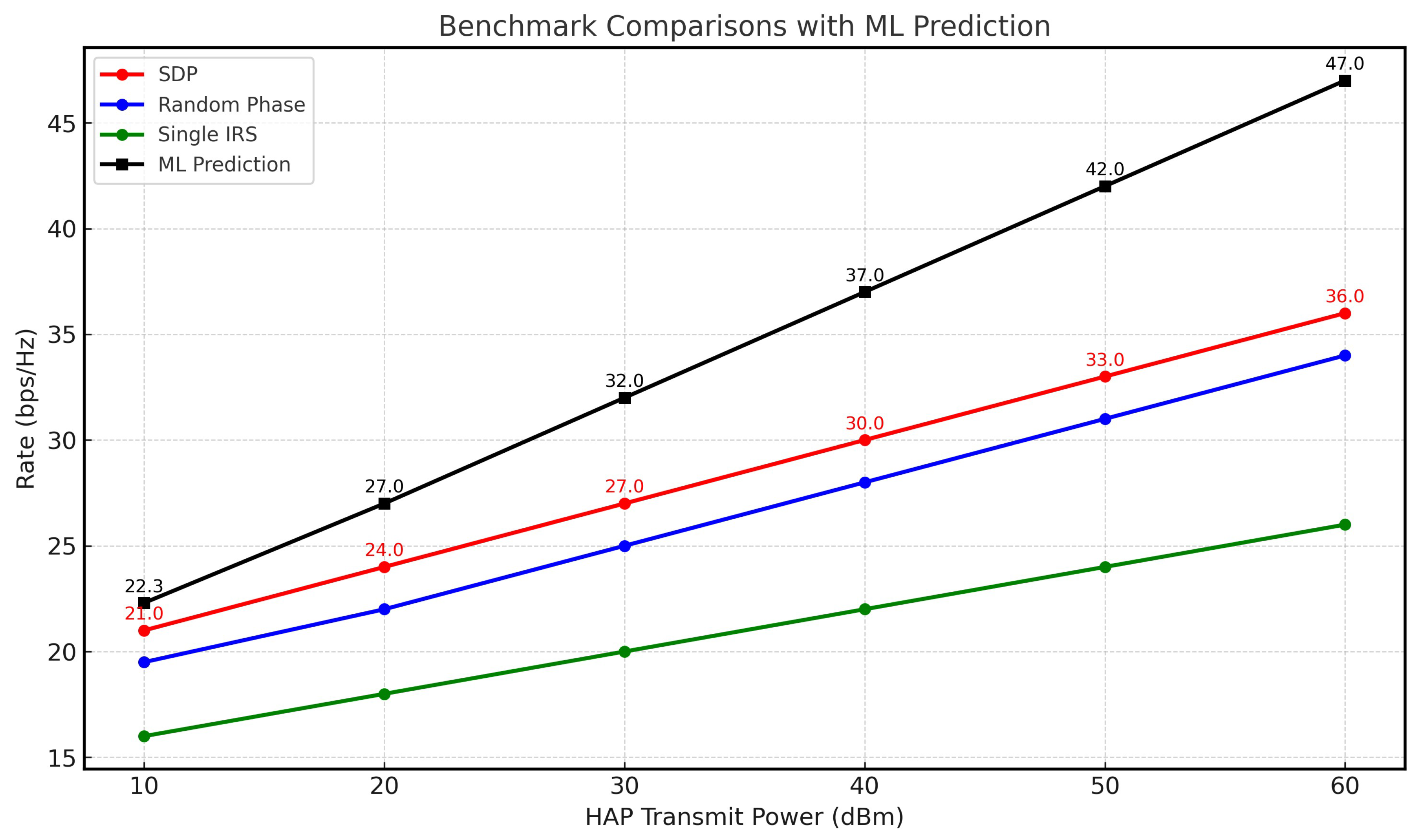

Figure 6 presents the sum rate versus transmitted power (

) at the HAP across different scenarios. While all methods follow similar growth trends, the single IRS case exhibits the slowest increasing rate, primarily due to the absence of the second IRS. Furthermore, our machine learning algorithm achieves the highest observed performance in this comparison, highlighting the critical role of phase shift optimization in maximizing the sum rate.

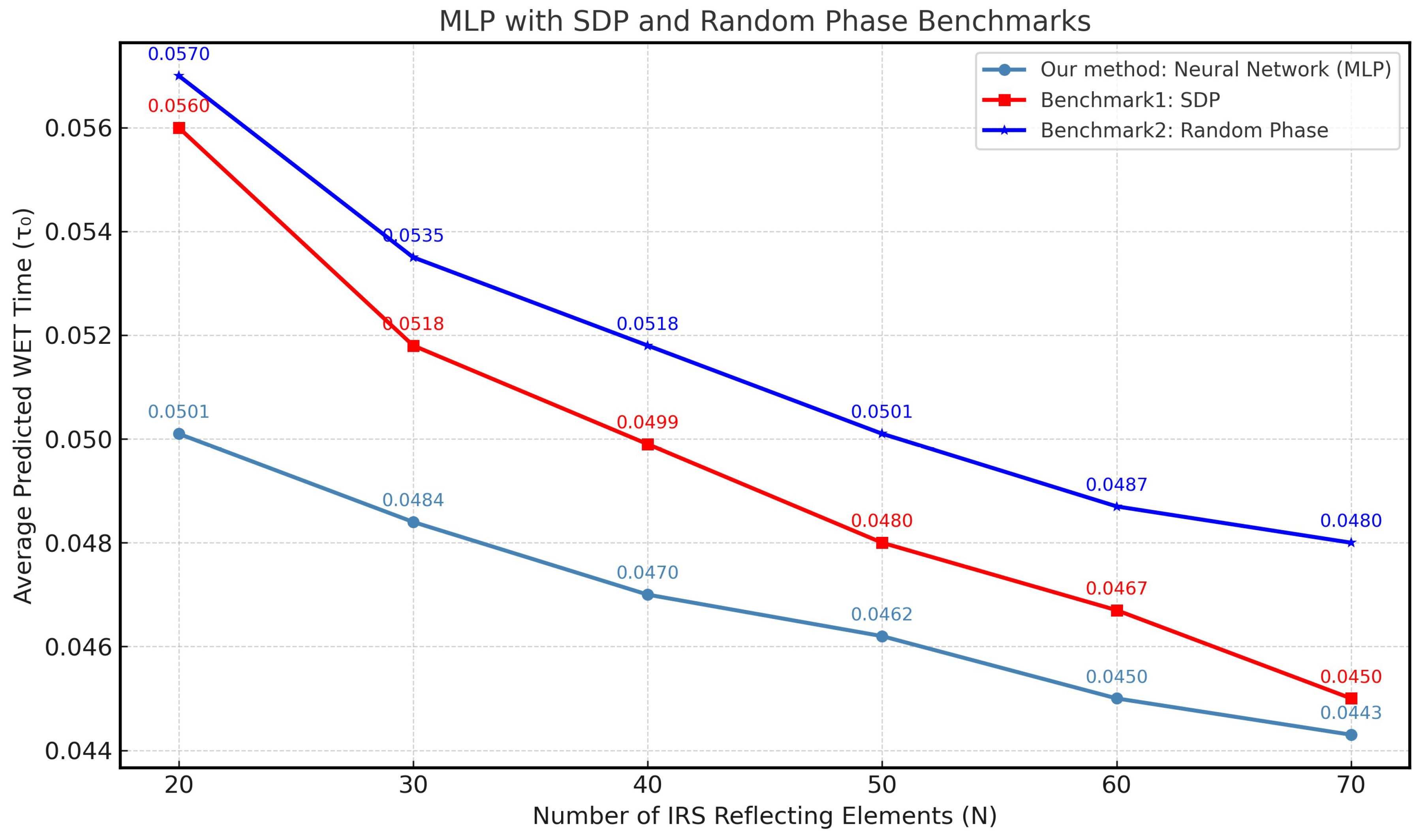

Wireless Energy Transfer (WET) time needs to be optimized to ensure that users receive sufficient energy to sustain both uplink and downlink transmissions while enhancing overall system efficiency. Optimizing is particularly delicate, as it must balance energy transmission and data communication. If is too short, users may not harvest sufficient energy, resulting in communication failures due to energy outages. Conversely, if is too long, it reduces the time available for data transmission and significantly impacts the achievable rate. For each channel realization and phase configuration, the script sweeps over candidate values (e.g., from 0.01 to 0.1) to find the value that maximizes the sum rate under energy harvesting and time-splitting constraints. The DNN predicts optimal phase shifts for a given , while itself is optimized via the outer-loop grid search.

Figure 7 shows the average predicted WET time

with respect to the number of reflecting elements. As shown, interesting relationships between this parameter and system performance are discovered through neural network optimization. The optimal WET time

decreases as the number of IRS reflecting elements increases. Specifically, when the system configuration has 20 elements, about 0.0501 time units are needed for energy harvesting, which decreases by approximately 11.6% to 0.0443 when 70 elements are used. This improvement is comparable to the SDP approach (which shows a 19.6% reduction from 0.056 to 0.045) and random phase allocation (which demonstrates an 18.9% reduction from 0.058 to approximately 0.047).

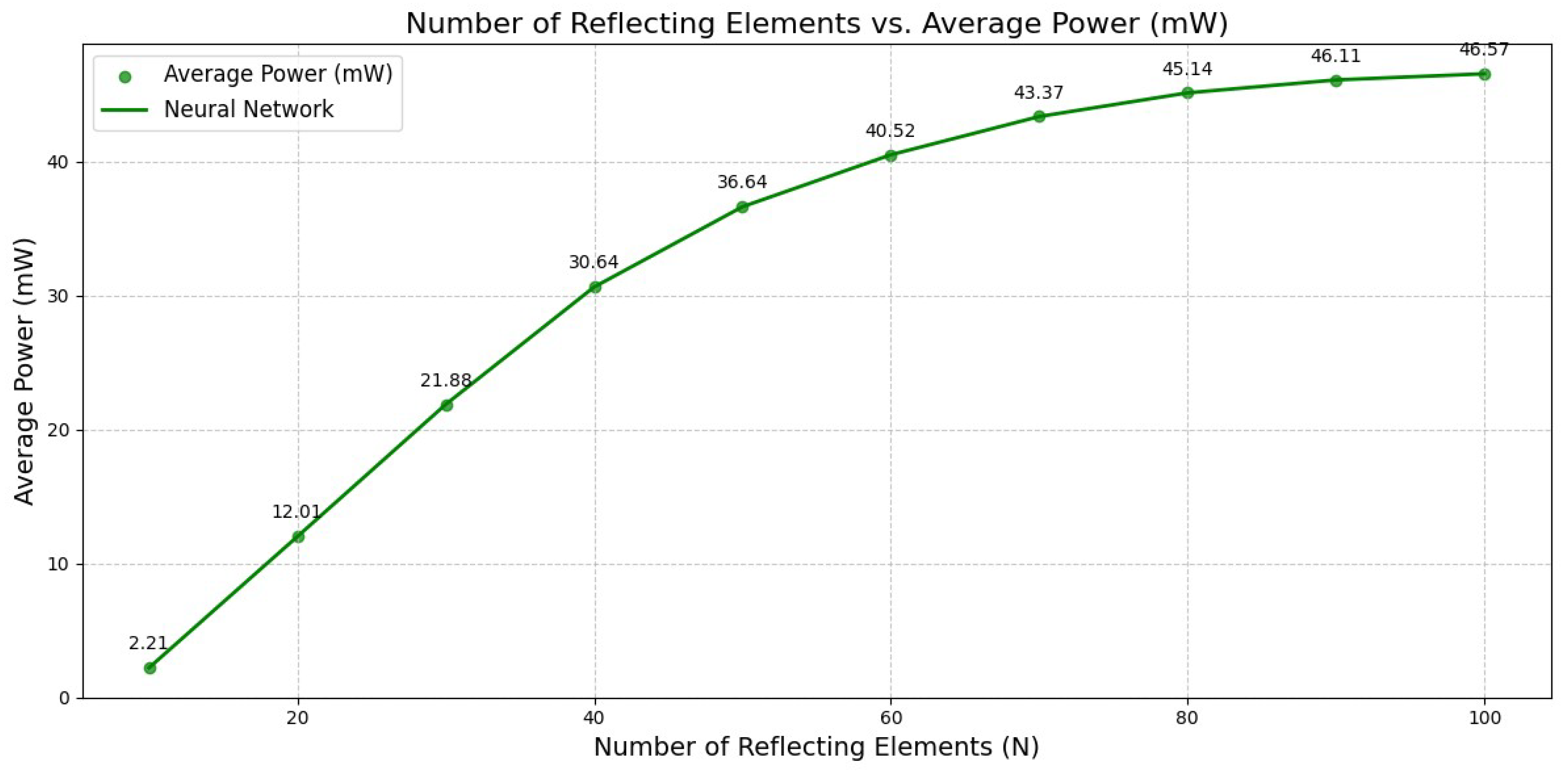

Figure 8 shows the harvested power with respect to the number of reflecting elements. From the graph, we observe that at

, the average harvested power is only 2.21 mW, indicating minimal energy transfer due to the limited reflecting surface. However, the amount increases as the IRS size increases to 40 elements, with the harvested power reaching approximately 30.64 mW. This demonstrates a 14-fold improvement compared to the smallest configuration. This trend continues with larger IRS configurations: when

, the average harvested power reaches 46.57 mW. This growth can be attributed to the array gain and the enhanced capability of the IRS to focus and reflect energy toward the users more efficiently. These results highlight the empirical effectiveness of increasing the number of IRS elements in improving wireless energy transfer.

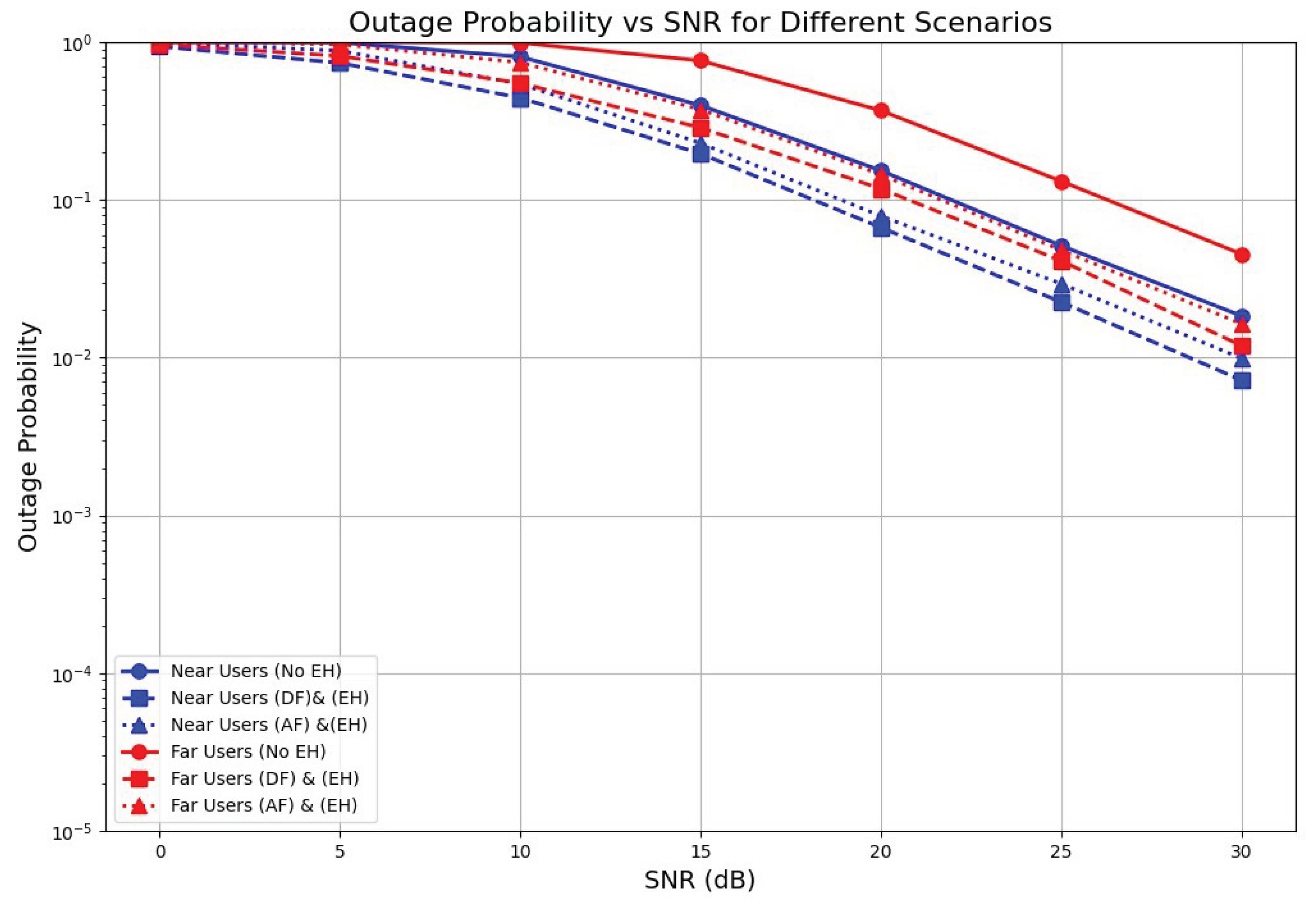

Figure 9 shows the outage performance of the near user

and the far user

with respect to different values of the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Outage probabilities are evaluated using Monte Carlo simulations that exploit the system behavior under IRS phase shifts predicted by ML. The DNN does not directly estimate the outage. We investigate the outage probability of

and

under two different relaying schemes, namely, Decode and Forward (DF) and Amplify and Forward (AF), considering both non-energy-harvesting and energy-harvesting relaying schemes.

As we can see that near users consistently perform better across all SNR values. With energy harvesting and DF relaying (blue dashed line), near users achieve an outage probability of less than at 30 dB SNR. This significant improvement over the no-EH scenario (blue solid line) demonstrates the effectiveness of our energy harvesting scheme.

The results show that while the AF relaying scheme with energy harvesting also provides substantial improvement over the no-EH scenario, it lags behind the DF relaying scheme at all SNR levels. For instance, at 30 dB, AF relaying achieves an outage probability slightly higher than , while the DF scheme drops below this threshold.

On the other hand, far users exhibit more interesting behaviour in the results. Without energy harvesting (red solid line), they experience higher outage probabilities, particularly at lower SNR values. However, their performance improves significantly with DF relaying and energy harvesting (red dashed line).

The graph shows that at 30 dB SNR, far users achieve an outage probability of about , representing a substantial improvement over the no-EH case. The AF protocol (dotted lines) performs slightly worse than DF for both user types, but still better than the no-EH scenario. This trade-off is expected, as AF is simpler to implement but also amplifies noise along with the signal.

6. Conclusion

To enhance the quality of the received signal in scenarios where line-of-sight (LoS) is limited, we propose a double IRS-assisted C-NOMA system that leverages wireless energy transmission.

The key contribution lies in using a machine learning model to optimize the double IRS phase shifts without relying on supervised labels from optimization solvers. We demonstrate that this learning-based approach achieves comparable or superior performance in terms of outage, harvested power, and time allocation at significantly lower complexity. The analysis captures the system’s joint behavior under practical energy constraints and relay protocols (DF and AF), which has not been addressed in this form before. These insights offer useful design directions for 6G systems in smart environments, particularly for low-power IoT and remote access networks. This paper considers a perfect SIC for ease of analysis and to benchmark the attainable performance. In future work, we plan to explore other state-of-the-art ML models such as deep reinforcement learning (DRL), graph neural networks (GNNs) and incorporate practical impairments such as residual interference and phase quantization to better study and generalize these findings.

Author Contributions

Y.A.-G.: Original draft preparation; Writing, review and editing; Formal analysis; Investigation; H.M.A.: Conceptualization; Validation; Writing, review and editing; Supervision; Investigation; N.T.: Methodology, Validation; Investigation; Writing, review and editing; Supervision; Z.N.: Investigation; Resources; Methodology, Validation; Writing, review and editing; Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to their use exclusively for academic research and their storage in a local environment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to Sultan Qaboos University for their support. The authors also wish to express their sincere appreciation to the Telecommunications Regulatory Authority (TRA) of Oman for its generous grant to support the publication of this paper through the TRA’s contribution to the UNESCO Chair on Artificial Intelligence at the Communication and Information Research Centre, Sultan Qaboos University, where the corresponding author is associated with.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Salih, M.M.; Khaleel, B.M.; Qasim, N.H.; Ahmed, W.S.; Kondakova, S.; Abdullah, M.Y. Capacity, Spectral and Energy Efficiency of OMA and NOMA Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 35th Conference of Open Innovations Association (FRUCT), 2024; pp. 652–658. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, P.V.; et al. Analytical Review on OMA vs. NOMA and Challenges Implementing NOMA. In Proceedings of the 2021 2nd International Conference on Smart Electronics and Communication (ICOSEC), Trichy, India, 2021; pp. 552–556. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Xu, X.; Fang, S.; Sun, Y.; Cao, Y.; Tao, X.; Zhang, P. Energy efficient secure computation offloading in NOMA-based mMTC networks for IoT. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2019, 6, 5674–5690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Yadav, P.; Kaur, M.; Kumar, R. A survey on IRS NOMA integrated communication networks. Telecommunication Systems 2022, 80, 277–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazunga, F.; Nechibvute, A. Ultra-low power techniques in energy harvesting wireless sensor networks: Recent advances and issues. Scientific African 2021, 11, e00720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lata, S.; Mehfuz, S. Efficient Ambient Energy-Harvesting Sources with Potential for IoT and Wireless Sensor Network Applications. In Proceedings of the Efficient Ambient Energy-Harvesting Sources with Potential for IoT and Wireless Sensor Network Applications, 2022; pp. 19–63. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Z.; et al. Resource Allocation for Double IRSs Assisted Wireless Powered NOMA Networks. IEEE Wireless Communications Letters 2023, 12, 823–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubry, A.; Maio, A.D.; Rosamilia, M. RIS-aided radar sensing in N-LoS environment. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 8th International Workshop on Metrology for AeroSpace (MetroAeroSpace), Virtual Conference, 2021; pp. 277–282. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Fei, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Guo, J. Joint waveform design and passive beamforming for RIS-assisted dual-functional radar-communication system. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2021, 70, 5131–5136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaghthawi, S.; Alsusa, E.; Al-Dweik, A. On the Performance of IRS-Aided NOMA in Interference-Limited Networks. IEEE Wireless Communications Letters 2024, 13, 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, B.P.; Mishra, R.K. Performance Analysis of SWIPT Cooperative-NOMA Over Rayleigh Fading Channel. In Proceedings of the 2023 15th International Conference on Computer and Automation Engineering (ICCAE), Sydney, Australia, 2023; pp. 541–545. [Google Scholar]

- Hoang, T.M.; Van, N.L.; Nguyen, B.C.; Dung, L.T. On the Performance of Energy Harvesting Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access Relaying System with Imperfect Channel State Information over Rayleigh Fading Channels. Sensors 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le-Thanh, T.; Ho-Van, K. MIMO NOMA with Nonlinear Energy Harvesting and Imperfect Channel Information. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering 2024, 49, 6675–6693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le-Thanh, T.; Ho-Van, K. Secured NOMA Full-Duplex Transmission with Energy Harvesting. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 91342–91356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhawatrah, M. Energy-Harvesting Cooperative NOMA in IoT Networks. Modelling and Simulation in Engineering 2024, 2024, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadevi, M.; Anuradha, S.; Sree, L.P. Performance Analysis of Downlink Cooperative NOMA System. In Proceedings of the VLSI, Communication and Signal Processing, Singapore, 2023; pp. 455–464. [Google Scholar]

- Umakoglu, I.; Namdar, M.; Basgumus, A.; Kara, F.; Kaya, H.; Yanikomeroglu, H. BER Performance Comparison of AF and DF Assisted Relay Selection Schemes in Cooperative NOMA Systems. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Black Sea Conference on Communications and Networking (BlackSeaCom), Virtual Conference, 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ajmal, M.; Zeeshan, M. A Novel Hybrid AF/DF Cooperative Communication Scheme for Power Domain NOMA. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 15th International Symposium on Applied Computational Intelligence and Informatics (SACI), Timișoara, Romania, 2021; pp. 000055–000060. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, D.; Yang, J.; Nam, S.S.; Joung, J.; Song, H.K. Cooperative Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access Transmission Through Full-Duplex and Half-Duplex Relays. IEEE Wireless Communications Letters 2023, 12, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Xia, X.; Zhou, J. Beamforming Optimization for Full-Duplex Relay in SIC-Enhanced Cooperative NOMA System. In Proceedings of the 2024 18th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP), Glasgow, UK, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, T.M.C.; Zepernick, H.J.; Duong, T.Q. Full-Duplex Cooperative NOMA Short-Packet Communications with K-Means Clustering. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Statistical Signal Processing Workshop (SSP), Hanoi, Vietnam, 2023; pp. 576–580. [Google Scholar]

- Elakiya, N.G.; Kandasamy, K.; Selvaraj, M.D. Performance Analysis Of Relay Based Cooperative NOMA System. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Wireless Antenna and Microwave Symposium (WAMS), Chennai, India, 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Bansal, M. Performance Analysis of NOMA-Based AF Cooperative Overlay System With Imperfect CSI and SIC. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 40263–40273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, J.; Shaik, P.; Bhatia, V. Performance of Cooperative NOMA with Virtual Full-Duplex based DF Relaying in Nakagami-m Fading. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 93rd Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2021-Spring), Virtual Conference, 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Han, L.; Zhu, W.P.; Lin, M. Outage Performance of Downlink Coordinated Direct and Relay Transmission with NOMA over Nakagami-m Fading Channels. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 92nd Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2020-Fall), Virtual Event, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Jadoon, A.; Aguiar, R.; Corujo, D.; Ferrao, F. A Comparative Analysis of Random Forest and Multilayer Perceptron Approaches for Classification of IoT Devices. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM), 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Isabona, J.; Oguejiofor, O.; Uche, C.; Onoh, G.; James, C.; Agu, F. Development of a Multilayer Perceptron Neural Network for Optimal Predictive Modeling in Urban Microcellular Radio Environments. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 5713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazici, I.; Shayea, I.; Din, J. A Survey of Applications of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Future Mobile Networks-Enabled Systems. Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal 2023, 44, 101455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Guan, X.; Zhang, R. Intelligent reflecting surface-aided wireless energy and information transmission: An overview. Proceedings of the IEEE 2021, 110, 150–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).