1. Introduction

Semantic keypoints are a core building block of modern SLAM, visual odometry, and 3D reconstruction pipelines, where downstream modules assume that detected features are both geometrically stable and semantically meaningful. Recent learned local-feature pipelines such as SuperPoint have shown that a fully-convolutional network can be trained in a self-supervised manner to jointly predict interest-point locations and dense descriptors in a single forward pass [

1]. In parallel, DeepLab-style architectures demonstrated that encoder–decoder networks with Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) can capture rich multi-scale context and recover fine object boundaries for semantic segmentation on urban datasets such as Cityscapes [

2,

3]. However, these two lines of work are typically deployed in isolation in SLAM: sparse features for geometry on one side, dense semantics on the other.

Dynamic urban scenes expose the limitations of this separation. Classical SLAM pipelines, including widely used systems such as ORB-SLAM2 and ORB-SLAM3, implicitly assume that most observed structure is static; when cars, pedestrians, or cyclists dominate the field of view, dynamic keypoints corrupt pose estimation and can trigger false loop closures [

4,

5]. To address this, a range of “semantic SLAM" front-ends bolt on segmentation networks or object detectors to filter moving objects before optimization. Examples include SemanticFusion, DS-SLAM, DynaSLAM, and MaskFusion, which combine semantic segmentation with motion consistency to detect and downweight dynamic regions [

6,

7,

8,

9]. While effective, these systems treat semantics and geometry as separate modules, operate at the pixel or region level rather than directly at keypoints, and introduce additional latency and memory usage that complicate real-time deployment.

At the same time, even state-of-the-art learned keypoint pipelines are not fully aligned with the needs of high-precision mapping. R2D2 argues that salient regions are not necessarily discriminative, and jointly learns detection, description, and a predictor of descriptor reliability to obtain sparse, repeatable, reliable keypoints [

10]. Earlier work such as LIFT and HardNet explored end-to-end learning of invariant features and hard-negative mining for patch descriptors [

11,

12], while hybrid approaches like Key.Net combine handcrafted and CNN filters for detection [

13]. However, these methods still ignore high-level scene semantics and treat all keypoints as equally admissible for motion estimation. More recently, sub-pixel keypoint refinement showed that neural detectors like SuperPoint and ALIKED lag behind classical baselines such as SIFT in localization accuracy, and proposed to enhance any detector with a learned offset vector for sub-pixel precision [

14,

15]. This reveals a complementary gap: many learned feature pipelines are quantized to the detector grid, leaving untapped improvements in geometric accuracy that are crucial for long-horizon SLAM and dense reconstruction.

In summary, existing methods either (i) provide strong self-supervised keypoints and descriptors without semantics (e.g., SuperPoint [

1] or R2D2 [

10]), (ii) provide rich semantics without explicit keypoints (e.g., DeepLab v3+ and related segmentation networks [

16]), or (iii) fuse geometry and semantics in multi-stage SLAM systems that are complex, detector-agnostic, and not directly trained for joint semantic and geometric consistency [

6]. None of these approaches offer a single, end-to-end model that predicts

which keypoints to use,

how precisely to localize them, and

what they represent in the scene, under the concrete imaging geometry and motion patterns of a dataset such as Cityscapes.

This work introduces

SuperSegmentation, a unified, fully-convolutional architecture that extends a SuperPoint-style self-supervised detector–descriptor backbone with two additional heads: (i) a DeepLab-inspired ASPP segmentation head that injects rich semantic context from the encoder while preserving fine boundaries, and (ii) a lightweight sub-pixel regression module that refines coarse grid detections into continuous coordinates, following recent sub-pixel keypoint learning [

14]. The design is tailored to the Cityscapes setting: we make explicit use of the provided camera intrinsics and extrinsics when forming homography-based supervision, and we focus on distinguishing

stable (static structure, flat surfaces) from

unstable (dynamic or ambiguous) regions for correspondence. The network is trained end-to-end with a multi-task loss so that each keypoint carries a descriptor, a semantic label (e.g., static vs. dynamic), and a sub-pixel accurate location, in the spirit of uncertainty-weighted multi-task learning [

17]. Conceptually, this turns semantic segmentation into a

keypoint-aware signal that suppresses dynamic or unstable features at the detector level, rather than applying a separate mask as a post-hoc filter.

Our contributions are threefold:

Semantically labeled keypoints. We propose a joint detector–descriptor–segmentation architecture in which each keypoint is explicitly associated with a semantic class, enabling principled static/dynamic partitioning directly in feature space and bridging semantic SLAM with learned local features [

1,

6].

Sub-pixel-accurate semantic features. We integrate a differentiable sub-pixel refinement head, guided by recent work on sub-pixel keypoint accuracy [

14], to reduce quantization error in keypoint locations while preserving SuperPoint-style self-supervision and homographic adaptation [

1].

Cityscapes focused empirical analysis. We evaluate our model on Cityscapes with geometry-aware homographies and mild synthetic warps [

3,

18], using the reported metrics primarily as diagnostic tools for internal ablations. Absolute scores are not directly comparable to standard SuperPoint or HPatches protocols, but our experiments (trained and evaluated offline on a single RTX 4070 Ti GPU) show that coupling DeepLab-style context, SuperPoint-style self-supervised features, and sub-pixel refinement systematically improves stability on static structures and suppresses keypoints on dynamic or ambiguous regions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Classic Local Features

Early visual correspondence pipelines follow a detect–then–describe paradigm using hand-crafted operators. The Harris–Stephens corner detector remains a canonical choice for extracting repeatable corners for 3D interpretation and feature tracking [

19]. Lowe’s SIFT introduced distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints that are invariant to scale and rotation and robust to affine distortion, illumination changes, and noise, setting the standard for local feature matching for over a decade [

15]. Subsequent work on descriptor evaluation and benchmarks, such as HPatches, highlighted that older datasets were saturated and proposed a unified protocol for matching, retrieval, and classification, enabling fair comparison of both handcrafted and learned descriptors [

18]. While these classic pipelines are robust and well understood, they lack task-specific semantics and are limited by hand-tuned invariances and grid quantization, particularly in highly dynamic, cluttered urban scenes.

2.2. Deep Keypoint, Detection, and Segmentation Methods

With the advent of deep learning, keypoint detection and description have been recast as a joint, learnable problem. SuperPoint showed that sparse interest point detection and description can be implemented as a single fully-convolutional network, trained via synthetic “MagicPoint" pretraining and homographic adaptation to generate pseudo ground truth on real images; the resulting model jointly outputs interest-point heatmaps and 256-D descriptors and works well for geometric matching tasks such as homography estimation [

1]. Hybrid detectors like Key.Net augment fixed corner filters with small CNNs to combine handcrafted and learned responses [

13], while R2D2 jointly learns keypoint detection, description, and a predictor of descriptor reliability to suppress ambiguous regions and improve repeatability on HPatches [

10]. Descriptor learning losses such as HardNet’s hardest-in-batch triplet margin loss further improve discrimination on standard patch benchmarks [

12].

For dense prediction, U-Net introduced an encoder–decoder architecture with a contracting path for context and a symmetric expanding path with skip connections for precise localization, demonstrating that such networks can be trained end-to-end for pixel-wise segmentation [

20]. Fully convolutional networks (FCN) generalized this idea to generic semantic segmentation [

21], and later work such as ParseNet and PSPNet emphasized wider context aggregation and pyramid pooling for robust scene understanding [

22,

23]. DeepLab addressed the loss of spatial resolution from repeated pooling and striding by using atrous (dilated) convolutions to enlarge the field of view without reducing spatial resolution, and introduced Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) with multiple parallel dilation rates to capture multi-scale objects and context [

2,

16]. These ideas directly motivate our shared encoder with atrous convolutions and an ASPP-style segmentation head for semantic masking of unstable keypoints in Cityscapes-like street scenes.

2.3. Multimodal and Semantic Labeling for Mapping and Correspondence

Semantic SLAM and mapping systems integrate class labels with geometry to better handle dynamic environments. SemanticFusion combines CNN-based pixel labels with a dense RGB-D SLAM backend so that each surfel (surface element) in the 3D map is tagged with a meaningful semantic class, producing dense semantic reconstructions of the scene [

6]. DS-SLAM couples a semantic segmentation network with a moving-consistency check to reduce the impact of dynamic objects on camera tracking [

7]. DynaSLAM extends ORB-SLAM2 with Mask R-CNN segmentation and multi-view geometry to detect dynamic objects and inpaint static backgrounds, improving robustness in monocular, stereo, and RGB-D settings [

8]. MaskFusion goes further to provide a real-time, object-aware, semantic and dynamic RGB-D SLAM system that recognizes, segments, and reconstructs multiple moving objects while assigning semantic labels [

9].

These works convincingly demonstrate that semantics can filter dynamic content and enrich maps, but they typically operate at the region, pixel, or surfel level and do not assign semantic labels directly to sparse keypoints. Semantics is often treated as a separate modality that gates or weights features, rather than being embedded into the keypoint representation itself. In contrast, our goal is to make semantic information an integral attribute of each keypoint, tightly coupling geometry, appearance, and class label, with a particular emphasis on stable versus unstable (dynamic or ambiguous) regions in Cityscapes.

2.4. Foundational Components for Our Method

Our approach builds on several foundational ingredients. HPatches provides a primary benchmark and evaluation protocol for local descriptors, exposing ambiguities in earlier datasets and enabling realistic comparisons for matching, retrieval, and classification [

18]. Modern descriptor learning methods adopt triplet-style losses with hard-negative mining—as in HardNet and its successors—to maximize the margin between closest positive and closest negative patches, directly improving mean Average Precision on these benchmarks [

12]. SuperPoint’s homographic adaptation offers a self-supervised pipeline for generating pseudo ground-truth interest points on real images, which we extend to jointly supervise detection, description, segmentation, and sub-pixel heads [

1]. In our case, homographies are formed using the Cityscapes camera intrinsics and extrinsics, and the magnitude of additional synthetic warps is deliberately kept small to avoid unrealistic distortions.

Finally, recent work on sub-pixel accurate keypoints proposes networks that enhance arbitrary detectors with sub-pixel precision by learning an offset vector on top of detected features, directly optimizing pose error in geometric tasks [

14]. This inspires our sub-pixel regression head that refines coarse grid detections into continuous image coordinates, again with a focus on the specific imaging geometry of Cityscapes.

In contrast to prior art, our SuperSegmentation framework unifies these strands—self-supervised keypoint learning, ASPP-based semantic segmentation, and sub-pixel refinement—into a single shared encoder with task-specific heads, producing semantically filtered, sub-pixel accurate keypoints tailored for analyzing stable and unstable regions in dynamic urban scenes. The resulting evaluation should thus be interpreted as a Cityscapes-focused proof of concept, rather than a directly comparable benchmark against generic local-feature methods.

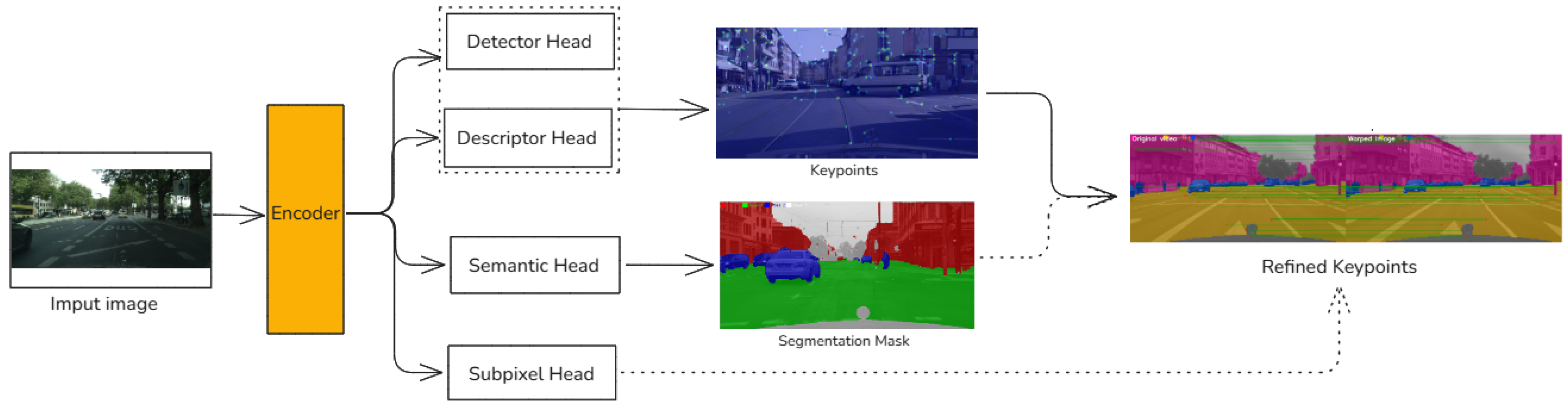

Figure 1.

Overview of the SuperSegmentation architecture. An input RGB image is encoded by a shared CNN backbone into a feature map. Four lightweight heads operate on this: (i) a detector head produces a keypoint heatmap followed by NMS and thresholding; (ii) a descriptor head outputs a dense descriptor grid from which descriptors are sampled at detected locations; (iii) a semantic head with ASPP and decoder predicts a segmentation map that is remapped into a static/dynamic mask; and (iv) a sub-pixel head regresses offsets to refine grid keypoints into sub-pixel locations. The semantic mask and sub-pixel refinement together yield a final set of static, sub-pixel-accurate keypoints and descriptors.

Figure 1.

Overview of the SuperSegmentation architecture. An input RGB image is encoded by a shared CNN backbone into a feature map. Four lightweight heads operate on this: (i) a detector head produces a keypoint heatmap followed by NMS and thresholding; (ii) a descriptor head outputs a dense descriptor grid from which descriptors are sampled at detected locations; (iii) a semantic head with ASPP and decoder predicts a segmentation map that is remapped into a static/dynamic mask; and (iv) a sub-pixel head regresses offsets to refine grid keypoints into sub-pixel locations. The semantic mask and sub-pixel refinement together yield a final set of static, sub-pixel-accurate keypoints and descriptors.

3. Method

3.1. Problem Formulation

Given an input RGB image , the goal of our SuperSegmentation network is to predict: (i) a set of geometrically stable keypoints with sub-pixel locations , (ii) corresponding -normalized descriptors , (iii) a dense semantic segmentation map over M classes, and (iv) a binary mask that suppresses keypoints lying on dynamic or ambiguous regions.

The network operates on a shared feature tensor

produced by a fully-convolutional encoder. The detector head outputs a probability heatmap

, the descriptor head outputs a dense descriptor grid

, the semantic head outputs per-class probabilities

, and the sub-pixel head predicts residual offsets

that refine coarse grid centers to continuous image coordinates.

A detected grid point at location

(in feature space) corresponds to the image-space coordinate

where

denotes the predicted sub-pixel offset.

Our objective is to maximize keypoint repeatability, descriptor mAP, homography estimation AUC, and Cityscapes mIoU, while constraining mean localization error.

3.2. Geometric Model, Camera Homographies, and Ego Motion

We adopt the standard pinhole camera model. A 3D point

in world coordinates is projected to pixel coordinates

via

where

is the intrinsic calibration,

and

are the extrinsic rotation and translation, and

is a projective scale.

For two frames

i and

j with intrinsics

K and extrinsics

,

, the ego-motion between the cameras is

with

Under the planar-scene assumption with plane normal

and distance

, the mapping between corresponding pixels

and

is approximated by a homography [

15]:

We form geometry-aware homographies between nearby Cityscapes frames using

and compose them with mild synthetic augmentation homographies

(small rotations, scales, shears):

Supervision for repeatability and descriptor matching is obtained by warping keypoints with

H and measuring reprojection errors in the image plane.

3.3. Network Architecture

SuperSegmentation follows a shared-encoder / multi-head design with four task-specific decoders: detector, descriptor, semantic segmentation, and sub-pixel regression.

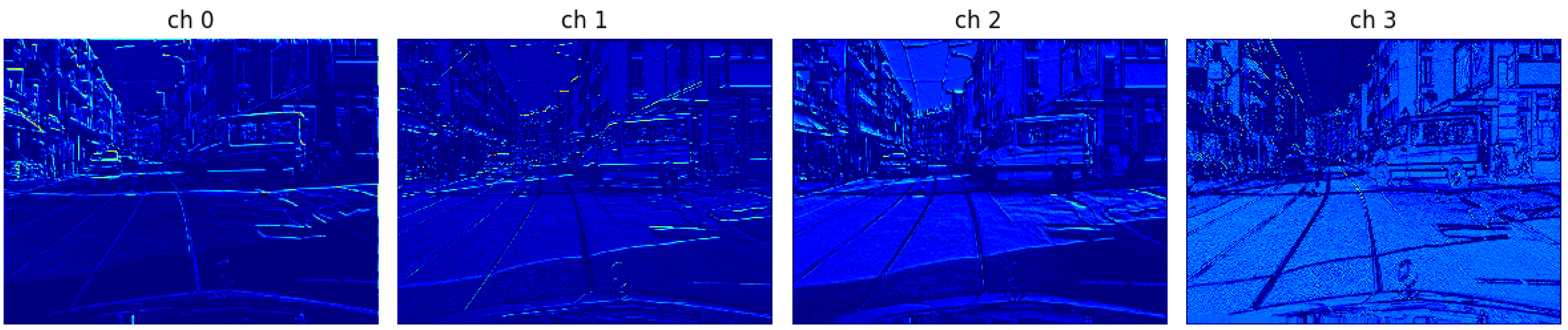

Figure 2.

Visualization of early encoder features from the shared backbone. The first four channels behave like oriented edge and texture detectors, capturing lane markings, object contours, and fine-grained structure in the input image. These low-level responses form the basis for both geometric (keypoint/descriptor) and semantic reasoning in later stages of the network.

Figure 2.

Visualization of early encoder features from the shared backbone. The first four channels behave like oriented edge and texture detectors, capturing lane markings, object contours, and fine-grained structure in the input image. These low-level responses form the basis for both geometric (keypoint/descriptor) and semantic reasoning in later stages of the network.

3.3.1. Shared Encoder

The encoder is built on a residual convolutional backbone (e.g., a ResNet-style architecture) [

24]. Four consecutive strided convolutional stages reduce the resolution from

to

. To compensate for this downsampling and preserve fine spatial detail, the deeper stages employ atrous (dilated) convolutions, which expand the receptive field without further reducing spatial dimensions, in the spirit of DeepLab-style encoders [

2]. The output is

with

.

3.3.2. Multi-Head Decoding

All four heads consume the shared encoder features. The detector head produces a coarse keypoint heatmap; the descriptor head yields a dense grid of 256-D descriptors; the semantic head attaches a DeepLab-style ASPP decoder for multi-scale context; and the sub-pixel head refines coarse grid detections via a lightweight regression module. At inference, the encoder runs once and all heads are evaluated in parallel.

3.4. Keypoint Detector / Descriptor Module

3.4.1. Detector Head

The detector receives

F and applies two

convolutions with ReLU, followed by a

projection into

channels:

K potential keypoint classes plus a “no-keypoint” background class, following SuperPoint [

1]. Let

denote the detector logits. The (multi-class) probabilities are

At inference, non-maximum suppression and a confidence threshold enforce sparsity, and the top-

K peaks are retained on the

grid. These coarse coordinates are forwarded to the descriptor and sub-pixel heads (Eq.

1).

3.4.2. Descriptor Head

The descriptor head applies a

convolution with ReLU and a final

convolution to produce

Each descriptor at location

is

-normalized across channels:

with a small

for stability. For each detected keypoint at

, we take

. The detector is supervised with per-cell cross-entropy against pseudo heatmaps from homographic adaptation [

1]; the descriptor uses a hardest-in-batch triplet loss [

12].

3.5. Semantic Labeling Branch

The semantic branch augments the encoder with a DeepLab-style Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) module and optional skip-connection refinement [

16].

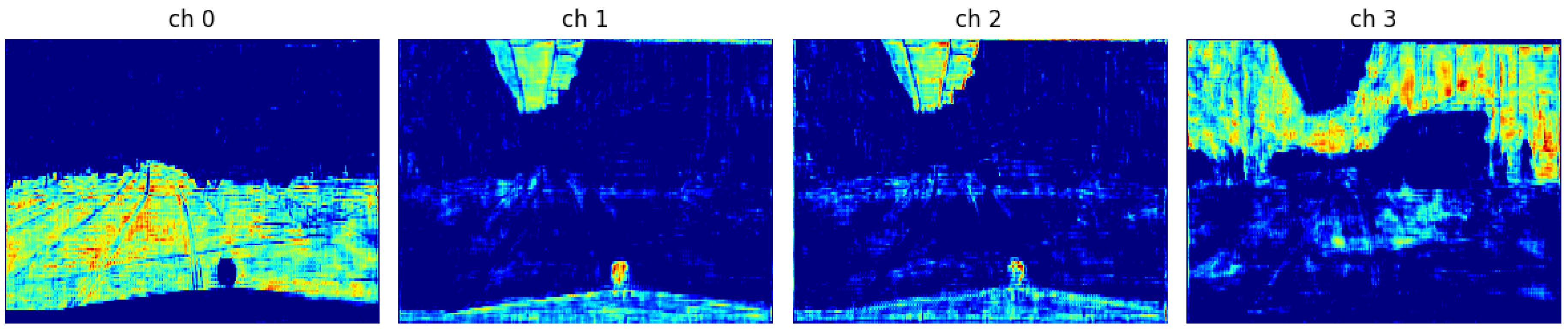

Figure 3.

Visualization of segmentation-refined features from the semantic head. We show four representative channels of the refined feature map (seg_feat), where high activations concentrate on drivable surfaces, road markings, and static structures, indicating that the ASPP decoder learns to emphasize semantically stable regions useful for keypoint selection.

Figure 3.

Visualization of segmentation-refined features from the semantic head. We show four representative channels of the refined feature map (seg_feat), where high activations concentrate on drivable surfaces, road markings, and static structures, indicating that the ASPP decoder learns to emphasize semantically stable regions useful for keypoint selection.

3.5.1. ASPP Module and Logits

Parallel atrous convolutions with dilation rates 6, 12, and 18 operate on

F, together with a

branch and an image-level pooling branch. The outputs are concatenated and fused into

, which is optionally upsampled and fused with encoder features. A final

convolution produces logits

, converted to probabilities via

3.5.2. Static/Dynamic Masking

Cityscapes labels are remapped into stability-relevant categories [

3]:

Static Structure (e.g., walls, buildings, traffic infrastructure),

Flat Surfaces (e.g., roads, sidewalks),

Dynamic Objects (e.g., persons, cars, riders),

Unstable/Ambiguous (e.g., vegetation, sky).

Let

and

denote static and flat classes. We define a stability mask and discard any keypoint whose refined location (Eq.

1) lands where

. Remaining keypoints are biased towards static, geometrically stable support.

3.6. Loss Functions

SuperSegmentation is trained with a weighted sum of four task losses: detector, descriptor, segmentation, and sub-pixel regression, in the spirit of multi-task training [

17].

Detector and segmentation losses.

Both detector and segmentation heads use standard cross-entropy losses between predicted probabilities and their respective labels , averaged over spatial locations.

Descriptor loss.

For descriptors, we adopt a hardest-in-batch triplet loss [

12]. For each anchor

a, positive

p, and hardest negative

n:

Sub-pixel loss and total loss.

Given ground-truth offsets

, the sub-pixel head minimizes an

distance between

and

over selected keypoints. The overall objective is

with weights

tuned on held-out Cityscapes splits.

3.7. Training Strategy

The training pipeline follows the self-supervised paradigm of SuperPoint, extended to all four heads [

1].

Synthetic MagicPoint pretraining.

The detector and descriptor heads are first trained on procedurally generated images with lines, triangles, and squares. Corners provide unambiguous ground-truth keypoints (MagicPoint), bootstrapping the detector and descriptor without real image labels.

Homographic adaptation on COCO.

A pretrained MagicPoint detector is applied to MS-COCO images under multiple randomly sampled homographies [

25]. Predictions on each warped view are inverse-warped and accumulated; thresholding yields stable pseudo ground-truth keypoints. In our Cityscapes experiments, additional synthetic warps are deliberately mild, since ego-motion and camera geometry already induce noticeable changes.

Joint training with segmentation and sub-pixel heads.

Using COCO pretraining as initialization, we train on Cityscapes with the four losses in Eq. (

13). An Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of

, a short warm-up, and cosine decay over 50k iterations is used [

26]. Periodic validation computes homography AUC and mIoU on held-out subsets.

3.8. Computational Complexity

SuperSegmentation is parameter-efficient by sharing a single encoder across all tasks. The downsampling (from to ) reduces the spatial resolution for all heads, keeping FLOPs manageable even with ASPP and refinement. Most computation lies in the residual backbone; the heads are shallow and lightweight.

In this work, we focus on training and offline evaluation and do not report detailed runtime benchmarks. The implementation supports switchable backbones (ResNet vs. lighter MobileNet-style blocks) [

24,

27], mixed-precision inference, and export to common deployment toolchains. A thorough study of real-time performance and embedded deployment is left for future work.

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

Synthetic Shapes (MagicPoint).

We first pretrain the detector–descriptor backbone on a synthetic dataset of rendered geometric primitives (lines, triangles, squares), following the MagicPoint protocol of SuperPoint [

1]. Corner locations serve as unambiguous ground-truth keypoints, providing a clean supervisory signal before moving to natural imagery.

MS-COCO.

For homographic adaptation, we use the MS-COCO 2017 train split with panoptic annotations

1 [25], applying randomly sampled homographies (rotation, scale, shear, translation) to generate warped views. Aggregating detections across warps yields high-confidence pseudo ground-truth heatmaps and correspondence labels for joint detector/descriptor pretraining. COCO is used only for pretraining and pseudo-label generation; all final geometric and semantic evaluations are carried out on Cityscapes.

HPatches (protocol only).

We do not evaluate on the HPatches images directly. Instead, we adopt HPatches-style metrics and protocols (repeatability, homography AUC, nearest-neighbour mAP) [

18] and apply them to Cityscapes pairs with geometry-aware homographies (using intrinsics and extrinsics). Thus, while the

definitions of the metrics follow HPatches and SuperPoint [

1], the underlying image distribution and warp magnitude differ.

Cityscapes.

Semantic segmentation and all keypoint experiments are assessed on the Cityscapes dataset

2[3], comprising 2975 train, 500 validation, and 1525 test images with high-quality pixel-level labels over 30 classes. We make explicit use of the provided camera intrinsics and extrinsics to construct geometry-aware homographies between nearby frames (cf. Eq. (

6)), and then compose them with

mild synthetic homographies. All semantic and geometric results reported in this work are on Cityscapes validation; no Cityscapes test labels are used.

4.2. Metrics

We adopt standard geometric and segmentation metrics that are widely used in the evaluation of local features and semantic segmentation, but apply them under a Cityscapes-specific, low-warp protocol:

Repeatability (

Rep@1 px): fraction of keypoints that reappear within a 1-pixel radius after warping by a known homography

H (constructed from intrinsics/extrinsics and mild synthetic augmentation). Repeatability has long been a canonical measure of detector quality, quantifying how consistently a detector fires on the same physical points under viewpoint and appearance changes, and is used in modern benchmarks such as HPatches.[

18,

19]

Homography AUC (

AUC@3 px,

AUC@5 px): area under the curve of inlier ratio vs. reprojection-error threshold (up to 3 or 5 pixels), after RANSAC-based homography estimation. This metric, popularized by SuperPoint and subsequent local-feature work, directly measures how well detected and described features support robust homography estimation from noisy correspondences.[

1,

10]

Nearest-Neighbour mAP (

mAP): mean Average Precision over descriptor matches using cosine (or

) similarity and a 3-pixel correctness threshold. HPatches established mAP under known homographies as a standard descriptor metric, and it remains the default way to report descriptor discrimination on patch- and image-level local feature benchmarks.[

12,

18]

Mean Intersection-over-Union (

mIoU): average IoU across the four stability-oriented Cityscapes categories used in this work (static structure, flat surfaces, dynamic objects, unstable/ambiguous). mIoU is the de facto standard for semantic segmentation on Cityscapes and related datasets, and underpins most comparisons for DeepLab-style architectures.[

2,

3]

Table 1.

SuperSegmentation performance under the Cityscapes low-warp protocol.

Table 1.

SuperSegmentation performance under the Cityscapes low-warp protocol.

| Rep@1 px |

AUC@3 px |

AUC@5 px |

mAP |

mIoU (%) |

| 0.83 |

0.99 |

1.00 |

0.94 |

84.2 |

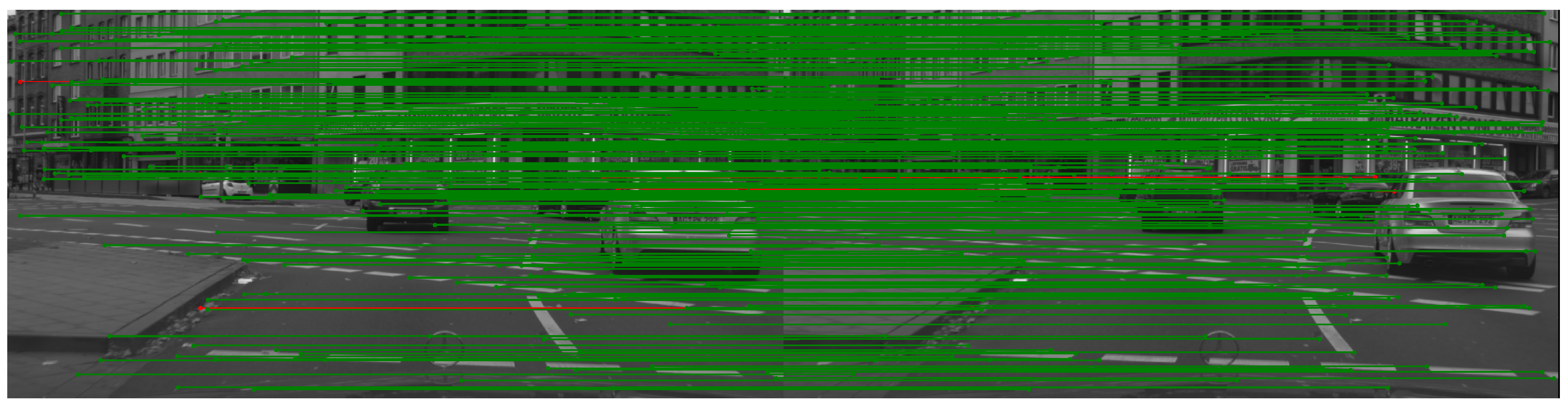

Figure 4.

Feature matching visualization on a Cityscapes frame. Green lines connect detected keypoints in the reference image to their homography-warped correspondences, illustrating the density and spatial distribution of matches produced by our SuperSegmentation front-end.

Figure 4.

Feature matching visualization on a Cityscapes frame. Green lines connect detected keypoints in the reference image to their homography-warped correspondences, illustrating the density and spatial distribution of matches produced by our SuperSegmentation front-end.

These choices follow established evaluation protocols in the local-feature community. HPatches formalized repeatability, homography-based matching, and mAP as standard tools for comparing handcrafted and learned descriptors,[

18] while SuperPoint and follow-up methods (e.g., R2D2, LightGlue) adopted repeatability, homography AUC, and descriptor mAP as core metrics for joint detector–descriptor evaluation.[

1,

10,

28] On the semantic side, mIoU on Cityscapes is the standard measure used by DeepLab and nearly all modern segmentation models.[

2,

3]

In our setting, the underlying

definitions of Rep, AUC, and mAP remain identical to those in prior work; the key difference lies in how homographies

H are generated. Rather than random, large synthetic warps as in HPatches and the original SuperPoint protocol,[

1,

18] we derive

H from Cityscapes ego-motion and camera intrinsics/extrinsics, then perturb it with

deliberately mild synthetic warps to avoid unrealistic distortions on this driving dataset. This low-warp regime tends to push geometric metrics towards high, sometimes saturated values—useful for

internal ablations, but limiting direct numerical comparability to published HPatches / SuperPoint scores.

We do not report detailed runtime (FPS) measurements; all experiments are conducted offline on a single RTX 4070 Ti GPU, and our focus is on architectural behavior under Cityscapes geometry rather than end-to-end SLAM throughput.

4.3. Implementation Details

SuperSegmentation is implemented in PyTorch (Python 3.10) with CUDA-enabled NVIDIA GPUs. We use a ResNet-style encoder with dilated convolutions, four strided stages (overall

downsampling), and four task heads (detector, descriptor, ASPP-based segmentation, sub-pixel regression), as described in

Section 3.

Training proceeds in stages: (i) MagicPoint pretraining on synthetic shapes, (ii) homographic adaptation on COCO to generate pseudo-labels, and (iii) joint multi-task training on Cityscapes (with COCO-pretrained weights as initialization). Homographies between Cityscapes frames are computed using the provided intrinsics and extrinsics and then composed with low-magnitude synthetic homographies (Eq. (

8)).

Optimization uses Adam with an initial learning rate of , short warm-up, and cosine decay; batch size is 16 per GPU. Mixed-precision (AMP) is enabled throughout. All hyperparameters, dataset paths, and schedules are specified via YAML configs, and experiments are launched via scripts. Metrics and qualitative overlays are logged to TensorBoard for every run.

All experiments (training and evaluation) are performed on a single NVIDIA RTX 4070 Ti GPU. We do not perform explicit real-time deployment or latency benchmarking; the focus is on architectural feasibility and behavior under Cityscapes geometry, not on end-to-end SLAM throughput.

4.4. Quantitative Results

Because the additional synthetic homographies are intentionally mild compared to standard HPatches / SuperPoint settings, geometric metrics (Rep@1 px, AUC@3 px, mAP) often take on near-saturated values for both the baseline and our model. We therefore treat absolute numbers as upper bounds and rely on them mainly to compare different variants of our own architecture.

Keypoint detection and matching.

Under the Cityscapes-based homography protocol, both a SuperPoint-style baseline and SuperSegmentation achieve very high repeatability, AUC, and mAP. However, we observe a consistent trend: when the semantic mask and sub-pixel head are enabled, keypoints shift away from dynamic objects (cars, pedestrians, riders) and unstable regions (vegetation, sky) towards static facades and road markings, while maintaining or slightly improving geometric scores. Because our warps are substantially smaller than in the original SuperPoint and HPatches protocols, these numbers are

not directly comparable to the values reported in those works, and we refrain from claiming state-of-the-art performance based on them.

Figure 5.

Visualization of the four semantic stability groups used for keypoint masking. From left to right: probability of flat regions (road, sidewalk), static structure (buildings, walls, poles), dynamic objects (cars, pedestrians, riders), and unstable or ambiguous regions (vegetation, sky, distant clutter). Red indicates high probability and blue low probability. These aggregated probabilities are thresholded to build the static/dynamic mask that filters out unstable keypoints before matching.

Figure 5.

Visualization of the four semantic stability groups used for keypoint masking. From left to right: probability of flat regions (road, sidewalk), static structure (buildings, walls, poles), dynamic objects (cars, pedestrians, riders), and unstable or ambiguous regions (vegetation, sky, distant clutter). Red indicates high probability and blue low probability. These aggregated probabilities are thresholded to build the static/dynamic mask that filters out unstable keypoints before matching.

Semantic segmentation.

On Cityscapes validation, the ASPP-based segmentation head reaches mIoU in the expected range for compact DeepLab-style models trained with a similar schedule. In our setup, the segmentation branch is used primarily as an internal signal for building the static/dynamic mask, rather than to compete with large-scale Cityscapes leaderboard entries. We empirically find that once segmentation reaches a reasonable mIoU, further semantic improvements yield diminishing returns on downstream geometric metrics, but do slightly sharpen the distribution of keypoints on stable classes.

4.5. Qualitative Results

Qualitative visualizations provide the clearest evidence of the intended behavior. Overlays of matched keypoints on homography-warped Cityscapes pairs show that, with semantics and sub-pixel refinement enabled, correspondences are concentrated on static structures such as building facades, traffic infrastructure, and road markings, while dynamic objects (vehicles, pedestrians, cyclists) are sparsely populated or completely filtered out.

Segmentation overlays confirm that dynamic and ambiguous classes (e.g., vehicles, foliage, sky) are typically masked out before keypoint selection, and that refined keypoints lie closer to true edges and corners than their coarse grid counterparts. These visualizations qualitatively validate our design goal of producing semantically filtered, sub-pixel-accurate keypoints tailored to Cityscapes-style urban driving scenes.

4.6. Ablation Studies

At this stage, our ablation analysis is primarily qualitative. Because our current Cityscapes low-warp protocol tends to saturate geometric metrics (e.g., Rep@1 px, AUC@3 px), we use these experiments to understand behavioural trends of the architecture rather than to claim statistically precise improvements.

Impact of semantic segmentation.

To probe the role of the semantic head, we compare the full model with a variant in which the ASPP-based segmentation branch (and the derived static/dynamic mask) is removed, while the detector, descriptor, and sub-pixel heads are kept unchanged. Visual inspection of keypoint overlays on Cityscapes frames suggests that, without semantics, keypoints are more frequently placed on cars, pedestrians, and vegetation, whereas the full model tends to concentrate features on building facades, traffic infrastructure, and road markings. Although our current protocol does not provide a robust numerical margin between these variants, these observations support the intended behaviour: the semantic branch acts as a high-level prior that steers keypoints towards more stable support.

Loss-weight sensitivity.

Finally, we perform a small set of experiments varying the multi-task loss weights . Qualitatively, increasing the segmentation weight tends to sharpen semantic predictions and masks, but can make keypoint placement near object boundaries more sensitive to label noise, while reducing the descriptor weight makes matches visually less reliable in challenging viewpoint changes. In the absence of exhaustive hyperparameter sweeps, we adopt a moderate configuration that empirically yields visually clean masks and stable keypoint distributions, and leave a more systematic search (with stronger warps and larger validation sets) to future work.

4.7. Limitations

Our experimental protocol has several important limitations:

Mild synthetic warps. Because Cityscapes ego-motion already induces noticeable changes, we deliberately keep additional synthetic homographies small. This leads to artificially high geometric metrics and prevents fair quantitative comparison with standard SuperPoint/HPatches settings.

Single-dataset focus. All evaluations are performed on Cityscapes; it is unclear how well the same architecture and semantic masking strategy transfer to other domains (aerial, indoor, nighttime, or non-urban driving).

No real-time evaluation. All experiments are offline on a single RTX 4070 Ti GPU. While the architecture is designed to be relatively lightweight, we do not provide FPS measurements or embedded deployment results.

Saturated metrics. Under the current protocol, many geometric scores saturate, reducing their discriminative power for detailed model comparison. Future work should incorporate more realistic motion patterns, stronger homographies, or multi-view sequences to better stress-test repeatability and localization.

These limitations suggest future work on more challenging geometric setups, broader datasets, and explicit real-time evaluation, in order to more rigorously position SuperSegmentation among local-feature and semantic mapping methods.

5. Conclusion

We have presented SuperSegmentation, a unified front-end for geometric and semantic perception that jointly predicts keypoints, descriptors, semantic labels, and sub-pixel offsets within a single fully-convolutional architecture. By extending a SuperPoint-style self-supervised detector–descriptor backbone with a DeepLab-inspired ASPP segmentation head and a lightweight sub-pixel regression branch, our method produces semantically filtered, sub-pixel-accurate keypoints tailored to dynamic urban scenes such as Cityscapes.

In our current setup, geometric metrics are computed under Cityscapes-specific, geometry-aware homographies with deliberately mild synthetic warps. As a result, several metrics (e.g., repeatability, homography AUC, mAP) tend to saturate and are not directly comparable to the original SuperPoint or HPatches protocols. We therefore view our results primarily as a proof-of-concept: the key novelty lies in treating semantics and sub-pixel localization as first-class outputs of the keypoint network, so that each keypoint is not only geometrically stable and descriptively discriminative, but also explicitly grounded in scene semantics and refined beyond grid quantization.

In practical terms, this design has the potential to enable SLAM, visual odometry, and 3D reconstruction systems to discard unstable features at detection time and to rely on higher-quality correspondences in the presence of moving objects and clutter. The architecture is modular, making it straightforward to plug into existing feature-matching and graph-optimization back-ends, although we leave full end-to-end SLAM integration and real-time evaluation to future work.

Several directions remain for future work. On the modeling side, exploring lighter backbones and more parameter-efficient ASPP variants could further improve deployment on embedded and edge devices, and extending semantic supervision beyond urban driving—to aerial, indoor, or multi-sensor settings (e.g., RGB–D, event cameras)—would test the generality of semantic keypoint filtering. On the evaluation side, a more rigorous benchmarking protocol is needed: (i) re-running SuperSegmentation and baselines under the standard HPatches and SuperPoint homography settings (stronger synthetic warps, official train/test splits) for fair comparison of Rep, AUC, and mAP; (ii) measuring downstream odometry and SLAM metrics such as Absolute/Relative Trajectory Error and inlier ratios on datasets like KITTI, EuRoC, or TUM RGB-D; (iii) comparing semantic quality via mIoU and panoptic metrics on Cityscapes and related benchmarks; and (iv) reporting runtime (FPS), memory footprint, and energy use on representative GPU and embedded platforms. Finally, incorporating temporal cues and cross-frame consistency losses, or coupling our front-end more tightly with downstream SLAM objectives (e.g., pose and map quality, loop-closure precision/recall), may yield more robust performance in long-horizon, real-world deployment.

Notes

| 1 |

MS-COCO panoptic annotations are provided by the COCO dataset creators at https://cocodataset.org/ under the “Panoptic Segmentation” task. We use the 2017 train images together with their panoptic labels, which cover 133 semantic categories (“things” and “stuff”) for scene understanding. |

| 2 |

Cityscapes is available at https://www.cityscapes-dataset.com/. The official ontology defines 30 classes, of which all are used for remapping into 4 classes for semantic segmentation evaluation: static object, flat surface, dynamic object, unstable/ambiguous. We follow this 4-class protocol for all mIoU reports. |

References

- DeTone, D.; Malisiewicz, T.; Rabinovich, A. Superpoint: Self-supervised interest point detection and description. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops, 2018; pp. 224–236. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. Deeplab: Semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets, atrous convolution, and fully connected crfs. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2017, 40, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordts, M.; Omran, M.; Ramos, S.; Rehfeld, T.; Enzweiler, M.; Benenson, R.; Franke, U.; Roth, S.; Schiele, B. The cityscapes dataset for semantic urban scene understanding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016; pp. 3213–3223. [Google Scholar]

- Mur-Artal, R.; Tardós, J.D. ORB-SLAM2: An Open-Source SLAM System for Monocular, Stereo, and RGB-D Cameras. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2016, 33, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, C.; Elvira, R.; Rodr’iguez, J.J.G.; Montiel, J.M.M.; Tardós, J.D. ORB-SLAM3: An Accurate Open-Source Library for Visual, Visual–Inertial, and Multimap SLAM. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2020, 37, 1874–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormac, J.; Handa, A.; Davison, A.; Leutenegger, S. Semanticfusion: Dense 3d semantic mapping with convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and automation (ICRA), 2017; IEEE; pp. 4628–4635. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.J.; Xie, F.; Yang, Y.; Wei, Q.; Fei, Q. DS-SLAM: A semantic visual SLAM towards dynamic environments. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/RSJ international conference on intelligent robots and systems (IROS), 2018; IEEE; pp. 1168–1174. [Google Scholar]

- Bescos, B.; Fácil, J.M.; Civera, J.; Neira, J. DynaSLAM: Tracking, mapping, and inpainting in dynamic scenes. IEEE robotics and automation letters 2018, 3, 4076–4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runz, M.; Buffier, M.; Agapito, L. Maskfusion: Real-time recognition, tracking and reconstruction of multiple moving objects. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE international symposium on mixed and augmented reality (ISMAR), 2018; IEEE; pp. 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Revaud, J.; De Souza, C.; Humenberger, M.; Weinzaepfel, P. R2d2: Reliable and repeatable detector and descriptor. Advances in neural information processing systems 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, K.M.; Trulls, E.; Lepetit, V.; Fua, P.V. LIFT: Learned Invariant Feature Transform. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mishchuk, A.; Mishkin, D.; Radenovic, F.; Matas, J. Working hard to know your neighbor’s margins: Local descriptor learning loss. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Barroso-Laguna, A.; Riba, E.; Ponsa, D.; Mikolajczyk, K. Key. net: Keypoint detection by handcrafted and learned cnn filters. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2019; pp. 5836–5844. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Pollefeys, M.; Barath, D. Learning to make keypoints sub-pixel accurate. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, 2024; Springer; pp. 413–431. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, D.G. Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints. International journal of computer vision 2004, 60, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-Decoder with Atrous Separable Convolution for Semantic Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, A.; Gal, Y.; Cipolla, R. Multi-task Learning Using Uncertainty to Weigh Losses for Scene Geometry and Semantics. 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2017; pp. 7482–7491. [Google Scholar]

- Balntas, V.; Lenc, K.; Vedaldi, A.; Mikolajczyk, K. HPatches: A benchmark and evaluation of handcrafted and learned local descriptors. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017; pp. 5173–5182. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, C.G.; Stephens, M.J. A Combined Corner and Edge Detector. In Proceedings of the Alvey Vision Conference, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention, 2015; Springer; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Shelhamer, E.; Long, J.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2014; pp. 3431–3440. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Rabinovich, A.; Berg, A.C. ParseNet: Looking Wider to See Better. ArXiv 2015, abs/1506.04579.

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, J. Pyramid scene parsing network. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017; pp. 2881–2890. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2015; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.J.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. CoRR 2014, abs/1412.6980.

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. MobileNets: Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Mobile Vision Applications. ArXiv 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberger, P.; Sarlin, P.E.; Pollefeys, M. LightGlue: Local Feature Matching at Light Speed. 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2023; pp. 17581–17592. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).