1. Introduction

The time-course and phases of learning a balance skill have recently been described [

1]. These phases were distinct and are characterized by an early ‘online’ phase of large, rapidly accrued, gains (fast learning), followed by a plateau phase during the initial training session; a between-sessions ‘offline’ phase of further changes in performance without additional practice, and long-term retention of both the within-session and between-session gains. The acquired gains in balance performance were specific to the context of the trained task conditions and were not transferred to performance in a set of external perturbations differing by the sequence and properties of the trained VE (i.e.: velocity, direction, axis of rotation of the perturbations, as well as the visual cues [

1,

2].

Balance maintenance, including orientation of the head with respect to the earth vertical and stabilization against external perturbations, is dependent upon the processing of sensory input from the visual, vestibular and somatosensory (mainly proprioceptive and tactile) systems [

3]. This redundancy in sensory information is advantageous because of the different types of balance disturbances that the system needs to address [

3]. These different types of disturbances include static and dynamic steady state balance, anticipatory and compensatory postural adjustments [

4].

Anticipatory postural adjustments (APAs) are triggered by visual input. They predict disturbances in stability and, in turn, trigger task dependent responses (i.e., non-stereotypical) [

5,

6] that maintain stability [

7] . The relative contributions of vision and proprioception are flexibly weighted to minimize errors due to conflicting sensory input [

8]. Hence, when environmental conditions change, the postural control system must identify and selectively focus upon the sensory inputs that provide the most reliable information to maintain functionality [

9]. The loss of visual input, for example, via eye closure, forces the postural control system to rely only on vestibular and proprioceptive sensory inputs [

10,

11]. Generally, the loss of any type of sensory input modifies the performance of the postural control system and it is usually expressed as an increase in body sway [

12,

13].

The ability of maintaining balance while eliminating visual input, in order to enhance the performance of the somatosensory system is a key feature in the assessment of balance [14, 15], as well as in balance rehabilitation programs [

16]. Also, there is evidence that training with visual deprivation can improve balance after rehabilitation more than training with unrestricted vision [

17], suggesting that visual over-dependence as a compensatory strategy for coping with balance impairments may come with a functional cost [

17].

Given the important role of visual input for balance maintenance and postural adjustments, the aim of the current research was to study the learning of a balance task with no visual input - in task settings that, as a previous study [

1] has shown, affords robust gains in stability when practiced with visual input. We hypothesized that eliminated visual input would not modify the time-course characteristics of skill acquisition process due to sensory reweighting

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Seven healthy participants (N=7, male: female 4:3, mean age ±SD = 28.57 ±2.5 years), practiced maintaining balance on a moving platform, using an identical number of task iterations and the same platform movements, as published previously [

1] but with the participants blindfolded (refer to “training condition”). Data from the blindfolded (No Vision) group were compared to the data of a With-Vision group, training with visual input (N=8, male: female 4:4, mean age ±SD = 26.4 ±1.7 years), previously described [

1].

Due to factors related to lab availability, the lengthy preparation of each participant for each session and the long protocol, the number of participants per group was kept small. This is in agreement with similar studies on skill acquisition [

1]. Participants reported no history of disease or injury to the central or peripheral nervous systems (e.g., stroke, spinal cord injury), or to the musculoskeletal system (e.g., fractures ligament or muscle tears); none used medications that affect the Central Nervous System or motor performance (e.g., Ritalin). Eyeglasses or contacts wearers were allowed. The study was approved by the ethics committee for human experimentation at the C. Sheba Medical Center (RN 4308/06) and all participants gave their written informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study

2.2. Instrumentation

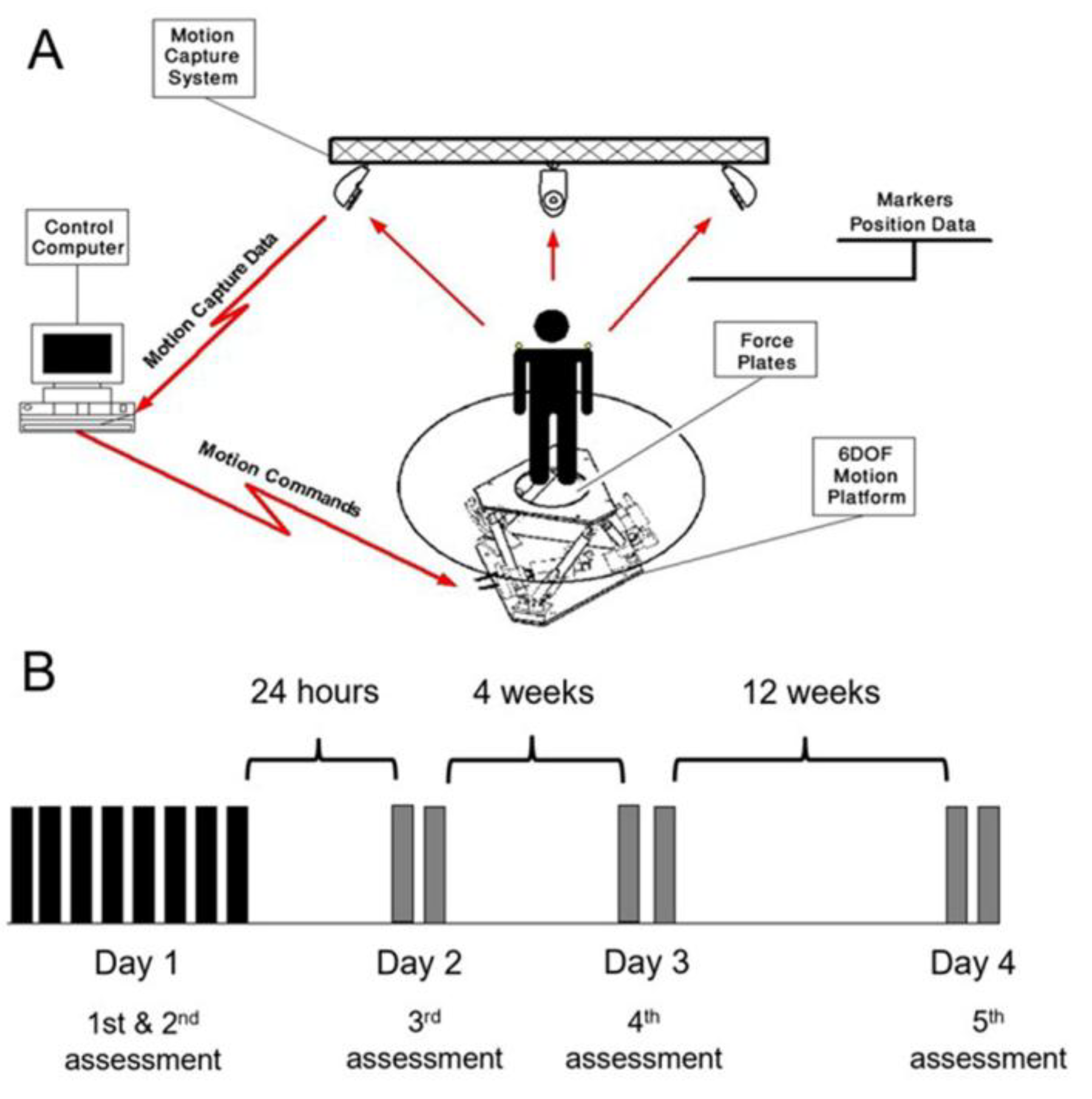

All experiments were conducted in a hospital-based motor performance laboratory. A “road” virtual environment (VE) was generated and displayed using the CAREN Integrated Reality System (Computer Assisted Rehabilitation Environment) with CAREN III software (MOTEK BV, Amsterdam, The Netherlands,

www.motekforcelink.com). Further information about the experimental setup and the road VE is provided in [

1] and

Figure 1A.

2.3. Procedures

The training task consisted of eight iterations of the virtual road scenario. To assess consolidation and long-term retention, participants performed three re-tests: two iterations of the training task 24 hours (Day 2), 4 weeks (Day 3) and 12 weeks (Day 4) post training. (

Figure 1B).

2.4. Basic Position for Assessment

The participants stood at the center of the platform with feet placed apart by about pelvis width (i.e., in the stance previously recommended) [

18] with each foot placed on a separate force plate. The foot placing was clearly marked using an adhesive marker. As participants did not step during the trial no correction of foot position was needed. Participants were secured by a harness and two slack safety ropes that did not restrict movement while upright. Participants were instructed to maintain this home position and to return to it if their feet moved due to platform perturbation.

2.5. Training Condition

A simulated road scenario (The road VE) was used for training. Participants were required to maintain their balance while standing on the platform and "travelling" along a "road" that was displayed onto a screen (2.5x3 meters, viewed from 2.4 meters). The road velocity was 30 m/s (equals to 1.8 km/min or 108 km/h). The completion of each run (i.e., route along the road) took 2 minutes and 48 seconds. The platform's movements were correlated with the visual stimuli; the actual platform movements were 40% of the perturbations’ function curve, hence forming a mismatch with the visual cues. The participants in the No-Vision group were blindfolded throughout all iterations of the training session. Maximal platform rotations on the x-axis (pitch) were 3.4° forward and 4.2° backward. The maximal translations on the x-axis (sway) were 12 cm to the right and 13 cm to the left. On the z-axis (roll) the maximum platform tilt was 6.5° to the right and 8.2° to the left. On the y-axis only, translation movements were made (maximum 8 cm). These parameters were determined following several pilot tests to achieve a challenging perturbation but to avoid excessive stepping. This task was new to participants; they could not have practiced it prior to the study, since the specific system and set-up are unique. The two training conditions (groups) differed only in that one group of participants trained with visual input from the VE (the ‘road’ scenario), while the other group were blindfolded throughout the training and in the post-training retention tests (i.e., whenever they experienced the VE road condition).

2.6. Performance Measures

The outcome measures used to assess performance, learning and retention were the total displacements of the CoP (x and z axes) as well as peak-to-peak displacements of each axis separately, in each task iteration [

19]. Since the parameters of the platform displacements were identical for all participants, the total CoP displacement was calculated without subtracting the platform displacements. Larger CoP displacements, related to stepping (postural corrections) in reaction to the perturbation, were included in the calculation of the CoP displacements, as long as the foot remained within the force-plates limits. However, there was no need to exclude any trials. The raw data were filtered and processed using MatLab software tool kits (Version 2008a, The Mathworks Inc., Natick, MA -

www.mathworks.com). A 4th order Butterworth low pass filter with a cutoff frequency of 6 Hz was used. The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.

2.7. Statistical Analyses

To test for overall learning, in the No-Vision group, the CoP displacements averaged across 2 consecutive task iterations, were compared across five time-points as within-subject factors in a repeated measures ANOVA. The time-points were Start (the first two task iterations, i.e., iterations 1 & 2); End (the final two task iterations in the training session, i.e., iterations 7 & 8); Day 2 (the 2 task iterations performed at 24 hours post-training); Day 3 (the 2 task iterations performed at 4 weeks), and Day 4 (the 2 task iterations performed by 12 weeks post-training).

To test the overall peak-to-peak CoP (the distance from the origin of axis) in the right-left and forward-backward directions in the No-Vision group, the CoP displacements averaged across 2 consecutive task iterations, were compared across five time-points (Start, End, Day 2, Day 3 Day 4) as within-subject factors in a repeated measures ANOVA.

To directly test for within-session gains (group means and SDs), a repeated measures ANOVA was applied to compare the performance measures across the 8 task iterations within the session (8 iterations) as a within-subject factor. To test for post training, between-sessions gains the following time-points compared: End of the training and Day2, Day3, Day4 post-training.

To test the overall peak-to-peak CoP (the distance from the origin of axis) in the right-left and forward-backward directions in the No-Vision group, the CoP displacements averaged across the 8 task iterations within the session (8 iterations) as a within-subject factorTo compare overall learning in the two conditions the CoP displacements at five time-points (Start, End, Day2, Day3, Day4) were compared as within-subject factors and group (No-Vision, With-Vision) was used as a between-subjects factor in a repeated measures ANOVA." Because there were only 2 groups, Independent sample t-tests and not post hoc tests were used to compare the performance of the two groups at each time point.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Version 23, SPSS Inc., Chicago IL). Whenever sphericity was not supported, the Greenhouse-Geisser method was used to correct the degrees of freedom and determine the significance of results [

20].

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3. Results

3.1. Training Blindfolded Within-Session and Long-Term Effects

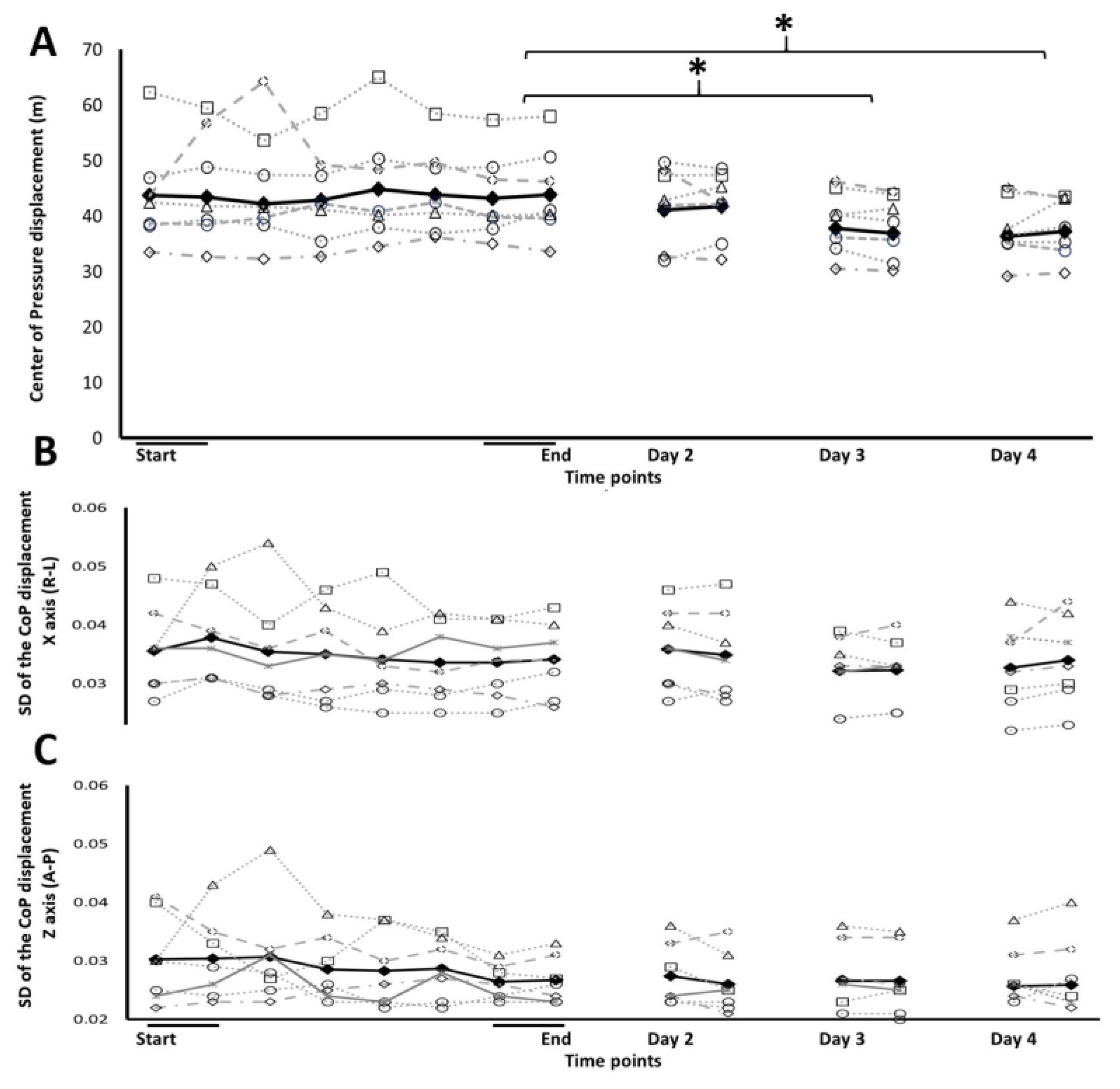

Overall, there were significant reductions in CoP displacement across the 5 time points of the experiment (F(4,24)=5.728, p=0.002, η2= 0.488) indicating a beneficial effect of training on postural stability (

Figure 2A). However, on average there were no significant changes in CoP displacements within the training session (F(1.567,9.403)=0.405, p=0.630, η2= 0.063). Moreover, the performance of the No-Vision group was poorly fitted by a power law function (R2=0.0009), with individual fits ranging between R2= 0.0135-0.8827 (median R2=0.1868). The gains in stability were, however, expressed after the training session, as between sessions gains across time-points: End, Day2, Day3, Day4 (F(3,18)=5.461, p=0.008 η2= 0.476), (

Figure 2A). Compared to the final two iterations of the training session (End), a significant reduction in the CoP displacement was evident at Day 3; 4 weeks (t(6)=2.833, p=0.03), (t(6)=5.44, p=0.026) and at Day 4; 12 weeks (t(6)= 6.05, p=0.033) post-training (

Figure 2A; S2).

In line with the notion of little or no practice related gains in the amount of sway during the training session, there were no significant reductions in the within-subject variability of balance maintenance performance as reflected in the standard deviations (SD) of the CoP displacement. The decrease in performance variability, (expressed by decreased standard deviation (sd) has been consider to be a hallmark of the establishment of a stable movement routine and automaticity in task performance [

21]. Task performance across the session, was of similar overall variance. Thus, when the individual SDs of the CoP's distance from the origin of axis (peak-to-peak CoP in the right-left and forward-backward directions) in each of the task iterations were compared across the 8 successive training iterations, there were no significant differences in the variability neither along the left–right axis (F(2.3061,13.836)=1.412, p=0.279, η2=0.190), (

Figure 2B) nor along the forward-backward axis (F(1.939,11.631)=1.591, p=0.244; η2=0.210) (

Figure 2C), across the task iterations in the training session. No significant reduction in the SD of the CoP displacement occurred even after the training session, i.e., as between sessions gains across time-points: End, Day2, Day3, Day4 (forward-backwards; (F(3,18)=0.726, p=0.550), η2= 0.108, right-left; F(3,18)=0.153, p=0.927, η2=0.025). Thus, the trained individuals showed no significant decreases in the variability of their postural adjustments to the moving platform (SD of the CoP displacements) during the training session itself, as well as between sessions after the completion of the training.

3.2. Training Blindfolded Compared with Training with Visual Input

The pattern of improvement in the blindfolded participants practicing the task in the current study (No-Vision) differed markedly from the time course of improvement in a group of participants practicing the same task with visual input afforded (With-Vision), described previously [

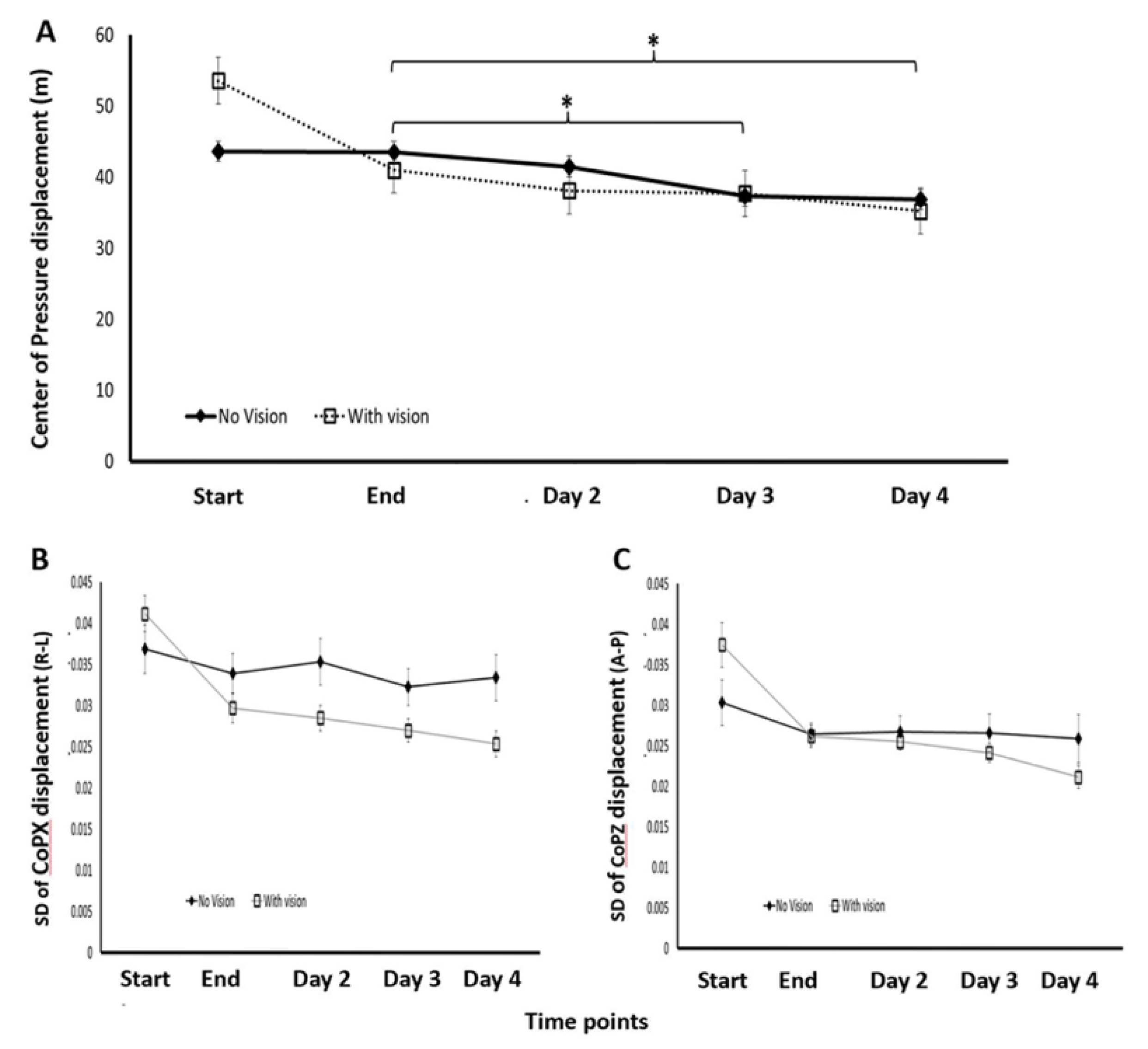

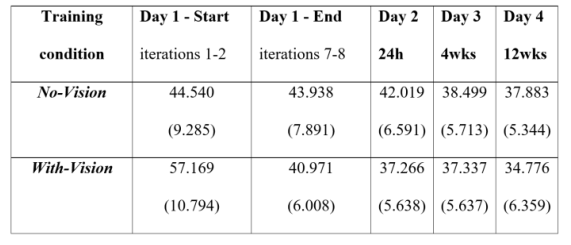

1]. Note that the actual platform movements in each task iteration and the number of task iterations were identical across the two groups. Means and (SDs) of the CoP displacements, for the 2 groups (No-Vision and With-Vision), compared across the 5 time points of the training condition are presented in

Table 1.

A repeated measures ANOVA comparing the CoP displacements at the 5 time-points of the two experiments showed that in both groups the total CoP displacements were significantly reduced across the entire study interval (F(1.747,22.709)=21.463, p>0.001, η2= 0.623) (

Figure 3A). There was also a significant group effect with the No-Vision group exhibiting overall smaller CoP displacements, (F(1,13)=0.783.916, p<0.001, η2= 0.984) as well as a significant interaction of group*time-point (F(1.747,22.709)=8.240, p<0.001, η2= 0.388). This significant interaction reflected the larger changes in CoP displacement within the training session in the With-Vision group (F(1.862,13.032)=9.535, p=0.003, η2=0.577), compared to the No-Vision group (F(1.567,9.403)=0.405, p=0.630, η2=0.063) (

Figure 3A). However, the group average CoP displacements did not differ by the 4 weeks post-training session (38.50m±5.71m, 37.34m±5.64m, No-Vision, With-Vision, respectively) (t(13)=-0.396, p=0.699) or at 12 weeks post-training (37.88m±5.34m, 34.78m±6.36m, respectively) (t(13)=-1.015, p=0.329) (

Table 1). Also, there was no significant interaction of group*time-point in the post-training phases of the study (between sessions, four time-points) (F(3,39)=0.780, p=0.512, η2=0.057); thus, in terms of the delayed gains and their maintenance in long-term memory, both training conditions were equally effective.

The individuals’ SDs of the CoP's distance from the origin of axis (peak-to-peak CoP) in each of the task iterations (representing the individuals’ variability) across the two groups (No-Vision, With-Vision) decreased significantly during the 8 iterations of the training session in both the forward-backward and right-left and directions (F(3.554,46.203)=9.144, p<0.001, η2=0.413; F(2.995,38.940)=12.179, p<0.001, η2=0.484, respectively). However, the timepoint*group interaction was significant, (F(3.554, 46.203)=4.187, p=0.007, η2=0.244, F(2.995,38.940)=5.760, p<0.001, η2=0.307, forward-backward and right-left and directions, respectively) (

Figure 3B,C) reflecting the larger reductions in variability, in both directions, in the With-Vision group [

1]. Significant reduction in the SD of the CoP displacement occurred, after the training session, as between sessions gains across the time-points (End, Day2, Day3, Day4) in both groups, in the right-left direction (F(3,39)=3.422, p=0.026, η2=0.208), but not in the forward-backward direction (F(3,39)=2.307, p=0.092, η2=0.151). For these 4 post-training timepoints, the timepoint*group interaction was not significant in either directions F(3,39)=1.890, p=0.147, η2=0.127; (F(3,39)=0.857, p=0.472, η2= 0.062; right-left; forward-backwards, respectively). Thus, the main differences between the groups were related to performance within the training session (across the 8 task iterations) but no such differences were found in the post-training phase

3.3. Training Blindfolded Triggered Smaller Initial CoP Displacements

The CoP displacements in the first iteration of the training session (

Figure 3A) were significantly smaller in the No-Vision group than that of the With-Vision group (t(13)= 3.056, p=0.009); by the end of the training session, there was no difference in the CoP displacements between the two groups (t(13)=(-0.824), p=0.425), a closing of the initial gap. The same trend was evident in the variance (SDs of the CoP displacements from origin) (

Figure 3B,C). In the first iteration, the variance in the No-Vision group was significantly smaller than that of the With-Vision group in the right-left and in the forward-backward direction (t(13)=2.476, p=0.028; t(13)=2.615, p=0.021, respectively). However, no such differences were found in the final iteration of the practice session (t(13)=-1.762, p=0.102; t(13)=-0.267, p=0.794, right-left and in the forward-backward directions, respectively) (

Figure 3B,C).3.1.1. Subsubsection

Bulleted lists look like this:

4. Discussion

The results of the current study show that practicing a complex balance maintenance task without visual input resulted in no significant within-session, “online”, gains, but nevertheless the training led to significant delayed reductions in the CoP displacement, i.e., gains that evolved between sessions. Thus, significant gains in postural stability were attained and retained weeks after the training experience, despite no evidence for immediate learning.

4.1. Blindfolded Training Resulted in Between-Sessions Gains

A pattern of improved performance ‘between-sessions’ without clear gains during the training experience (‘within-session’) is characteristic of training in well-established motor (familiar) motor tasks, and has been previously reported in perceptual and motor tasks that differ from the current one (e.g., the finger opposition sequence) [22-25]. It was proposed that in advanced stages of mastering a given skill there is no need to readjust the task solution routine when it is called to action since the adaptations that were initially required for the performance of the task are memorized and consolidated [

26]. Thus, if adequate training is afforded, gains will occur, but between the training sessions rather than between each individual iteration during the training session [

24,

25,

27]. These changes in performance represent distinct shifts in the activation of brain areas during learning: from a cortico–cerebellar-cortico loop in the novice learner to a crtico-striatal-cortico loop in the experienced learner, hence defining the ‘novelty effect’ in learning [

28]. In line with this notion, the current results suggest that the learning of the balance task, with no visual input, was based on the participants’ prior experience in situations of maintaining balance. One can consider, for example, prior experience with bumpy rides while standing in a vehicle (e.g., a bus ride) engaged in conversation (i.e., without paying attention to the route); a situation that most typical adults would have experienced many times.

4.2. Role of Visual Input in VR Training

Visual input plays a major role in triggering the anticipatory postural adjustments that occur prior to the perturbation and are designed to minimize balance disturbances via preprogrammed responses in order to maintain stability [

7]. Moreover, visual input has been shown to be the most dominant sensory source under compliant or moving-support surface conditions [

29]. In our previous study [

1], subjects were afforded a good preview of the upcoming parts of the “road”, a condition that has been shown to trigger anticipatory postural adjustments [

30]. Moreover, it has been shown that anticipatory postural adjustments for predictable perturbations decrease, with the excursions of the CoP and center of mass reduced following the perturbation [

31]. In retrospect (and given the current results) we propose that much of the gains in stability reported across the task iterations during the training [

1] may relate to decreases in anticipatory postural adjustments as the perturbations become more predictable and familiar. Given the notion that training with visual input triggers APA’s which rely on vision and anticipation, as well as cognitively driven processes that would be probably influenced by vision, and balance recovery relies on reflexive movements induced by an external perturbation, [

32] we suggest that the results show two distinct learning mechanisms, one for visual driven APA’s in the With-Vision group, characterized by with-in session gains and one for proprioceptive driven Compensatory Postural Reactions (CPA’s) in the No-Vision group, characterized by slow, between session gains.

Additionally, in the settings of the trained VE there was a platform-movement- visual mismatch the actual tilts of the platform were smaller by a factor of 0.4 compared to the VE presented inclines (i.e., the VE scenario was exaggerated to twice the actual platform tilts) (This was done in order to maintain safety on the one hand and make the scenario more salient and engaging on the other) [

1]. Thus, the rapid and large decreases in the CoP displacement when training with eyes open in the presence of incongruent sensory information may have been due to adaptation to 'incongruent' sensory information, resulting in a type of sensory re-weighting [

33]. Another explanation is that eliminating visual information during the training session interfered with the learning process. Therefore, there were no with-in session gains. The long-term gains could be explained by adapting a compensation mechanism.

We conjecture that many of the movements (CoP displacements) that occurred when the ‘road scenario’ was presented (with eyes open) entailed redundant anticipatory movements reflected by increased CoP displacements, rather than a response to the ‘road scenario’ perturbations per-se. These redundant anticipatory movements appeared to have been suppressed during the familiarization with the ‘road scenario’ during the training session.

In the absence of visual input, with increased dependence on proprioceptive and vestibular input, the balance system appears to address relatively familiar conditions (the platform movements) without the need to generate redundant anticipatory movements to the visual cues of (large) upcoming perturbations [34-36]. However, the training with no visual input afforded was a significant learning experience given the changes observed in the 'No-Vision' training group of the current study in the retention phase. In relation to real life posture adjustment, it would seem therefore that training in the No-Vision condition may be conducive to stability gains that are more relevant compared to the eye open condition where a sensory-mismatch was involved as is current in many VEs (e.g., [37-39].

Altogether, the results of the previous [

1] and the current study are in line with the notion that minimizing the displacement of the CoP or optimizing the amplitude of anticipatory movements perhaps exaggerated given a sensory mismatch, constitutes a key phase in learning a balance and stability skill when visual input is afforded [

40]. With no visual input triggering anticipatory postural adjustments and preparation for the up-coming perturbations, participants addressed the training conditions with little recourse to adapting existing balance maintaining routines, most probably using compensatory postural adjustments, which are not visually dependent, e.g., increased triceps surae Ia proprioceptive weighting [

41]. This conjecture is supported in the current study by the low CoP displacements already in the initial task iteration when practicing with no visual input compared to initial performance given identical platform movements in practicing with visual input. One would predict, for example, that blind adults who have never been exposed to visual cues for anticipatory postural adjustments in developing balance skills, would show even smaller CoP displacements during road scenario training than adults with acquired blindness; the latter may have learned to use visual input for anticipation when they established their basic balance skill repertoire. However, one would expect to find task-specific learning reflected as delayed and well retained gains in stability in both groups.

4.3. Training Conditions May Generate Different Sensory-Motor Gains

The current results may also be pertinent to the notion that different training conditions can generate different types of knowledge [

42]. Thus, a more visually dependent balance maintenance skill may develop in training with visual input, while a more proprioceptive input dependent balance maintenance skill may evolve in training with no visual input in the same VE conditions [

29]. Some support for this conjecture comes from the Elion et al, (2015)[

1] study wherein participants who practiced the ‘road’ scene in a vision afforded (eyes open) condition, showed no practice related gains in task-unrelated perturbation tests. Although performance in later sessions in task-unrelated perturbation tests was better than performance in the early sessions of the study, the gains were not related to the affordance of actual training in the road scene [

1].

In a systematic review of postural control in blind individuals [

43], it was suggested that there is good evidence that sensory systems other than vision, i.e., proprioception, light touch and vestibular, are used to compensate deficits in postural control in the blind. Nevertheless, there are reports showing that postural stability with eyes open or closed, was better in sighted athletes than blind athletes [

44]. On the other hand, congenitally blind subjects can perform equally well as normal sighted individuals when tested in their responses to perturbations with eyes open [

45]. Congenitally blind individuals performed significantly better than sighted individuals with eyes closed [

45]. Robust learning of how to anticipate repeated perturbations and to respond to them was described in congenitally blind people [

46] indicating that a nonvisual motor learning process, within the postural control systems, enables congenitally blind people to develop and control postural stability skills [

46]. On the other hand, studies of the effect of visual deprivation on rehabilitation after stroke suggest over-dependence on visual input as a compensatory strategy for coping with balance impairments [

47], specifically when the proprioceptive and vestibular systems have been impaired [

48]. The results of recent studies indicate that post-stroke patients may gain from balance maintenance training with no visual input afforded [

17]. However, the current results suggest that in the absence of visual input, gains may become apparent only days and weeks after the training session, i.e., much later than the learning of a balance skill with visual input [

49]

5. Conclusions

The results of the current study show that training blindfolded in a balance maintenance task can lead to long-lasting task-specific balance routines, a slow process mainly reflected in “offline” post-training gains. The results suggest that blindfolded balance training may rely on pre-established balance skills that are independent of visual input and require very little “online” adaptation. The results also raise the possibility that the initial, large, stability gains reported in eyes open VE training may reflect a minimizing of redundant postural adjustments to specific VE settings, such as the mismatch between the visual and actual platform movements’ amplitude. The current results thus support the notion that different training conditions on a given task can engage different brain systems and generate different types of ‘how to’ knowledge to be retained in long-term skill memory.

Author Contributions

OE contributed to the conceptualization of the study, the methodology, and the running of the study. data analysis and investigation, writing the manuscript and reviewing and editing. AK and PWeiss contributed to the conceptualization of the study, the methodology, the data analysis, to reviewing and editing and supervised the study. IS contributed to the methodology, the resources and to the data analysis. YB contributed to the methodology, to resources and to operating and running the study. ISN contributed to the conceptualization of the study, to review and editing and to funding of the study. All authors read and approved of the final manuscript.

Funding

“This research received no external funding”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the ethics committee for human experimentation at the C. Sheba Medical Center (RN 4308/06).

Informed Consent Statement

“Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.”.

Data Availability Statement

Will be provided upon request.

Acknowledgments

The study was part of a Ph.D. dissertation at the Sagol Department of Neurobiology, University of Haifa (O.E.). O.E. was supported in part by the Sheba Medical Center, Israel, the Sagol Foundation (2009-AK) and the ONO Academic College, Israel. The study was performed at the Center for Advanced Technologies in Rehabilitation, The Sheba Medical Center, Israel. We thank MOTEK Medical, The Netherlands, for technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Elion, O.; Sela, I.; Bahat, Y.; Siev-Ner, I.; Weiss, P. L.; Karni, A. Balance Maintenance as an Acquired Motor Skill: Delayed Gains and Robust Retention after a Single Session of Training in a Virtual Environment. Brain Res. 2015, 1609, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naumann, T.; Kindermann, S.; Joch, M.; Munzert, J.; Reiser, M. No Transfer between Conditions in Balance Training Regimes Relying on Tasks with Different Postural Demands: Specificity Effects of Two Different Serious Games. Gait Posture 2015, 41, 774–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massion, J. W. M. Posture and Equilibrium. In Clinical Disorders of Balance, Posture and Gait; Bornstein, A. M., Brandt, T. W. M., Eds.; Hodder Education Publishers, 1996; pp. pp 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Shumway-Cook, A.; Woollacott, M. H. Motor Control: Translating Research into Clinical Practice; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Maki, B. E.; McIlroy, W. E. Cognitive Demands and Cortical Control of Human Balance-Recovery Reactions. J. Neural Transm. 2007, 114, 1279–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, J. V.; Horak, F. B. Cortical Control of Postural Responses. J. Neural Transm. 2007, 114, 1339–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, D.; Kiemel, T.; Dominici, N.; Cappellini, G.; Ivanenko, Y.; Lacquaniti, F.; Jeka, J. J. The Many Roles of Vision During Walking. Exp. Brain Res. 2010, 206, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sober, S. J.; Sabes, P. N. Flexible Strategies for Sensory Integration During Motor Planning. Nat. Neurosci. 2005, 8, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, S.; Kiemel, T.; Jeka, J. J. Modeling the Dynamics of Sensory Reweighting. Biol. Cybern. 2006, 95, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M.; Casabianca, L.; Bottaro, A.; Schieppati, M. Graded Changes in Balancing Behavior as a Function of Visual Acuity. Neuroscience 2008, 153, 1079–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashner, L. M. Adaptation of Human Movement to Altered Environments. Trends Neurosci. 1982, 5, 358–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterka, R. J. Dynamic Regulation of Sensorimotor Integration in Human Postural Control. J. Neurophysiol. 2003, 91, 410–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marigold, D. S.; Eng, J. J.; Tokuno, C. D.; Donnelly, C. A. Contribution of Muscle Strength and Integration of Afferent Input to Postural Instability in Persons with Stroke. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2004, 18, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horak, F. B.; Wrisley, D. M.; Frank, J. The Balance Evaluation Systems Test (BESTest) to Differentiate Balance Deficits. Phys. Ther. 2009, 89, 484–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, A.; Montoya, M. F.; Llorens, R.; Bermúdez i Badia, S. A Virtual Reality Bus Ride as an Ecologically Valid Assessment of Balance: A Feasibility Study. Virtual Reality 2023, 27, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winstein, C. J.; Stein, J.; Arena, R.; Bates, B.; Cherney, L. R.; Cramer, S. C.; et al. AHA/ASA Guideline: Guidelines for Adult Stroke Rehabilitation and Recovery. Stroke 2016, 47, e98–e169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonan, I. V.; Yelnik, A. P.; Colle, F. M.; Michaud, C.; Normand, E.; Panigot, B.; et al. Reliance on Visual Information after Stroke. Part II: Effectiveness of a Balance Rehabilitation Program with Visual Cue Deprivation after Stroke: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2004, 85, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, M.; Freitas, S. M. Revision of Posturography Based on Force Plate for Balance Evaluation. Rev. Bras. Fisioter. 2010, 14, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, R. M.; Ingersoll, C. D.; Stone, M. B.; Krause, B. A. Center-of-Pressure Parameters Used in the Assessment of Postural Control. J. Sport Rehabil. 2002, 11, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathke, A. C.; Schabenberger, O.; Tobias, R. D.; Madden, L. V. Greenhouse–Geisser Adjustment and the ANOVA-Type Statistic: Cousins or Twins? Am. Stat. 2009, 63, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adi-Japha, E.; Karni, A.; Parnes, A.; Loewenschuss, I.; Vakil, E. A Shift in Task Routines During the Learning of a Motor Skill: Group-Averaged Data May Mask Critical Phases in the Individuals’ Acquisition of Skilled Performance. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2008, 34, 1544–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M. P. Refined Model of Sleep and the Time Course of Memory Formation. Behav. Brain Sci. 2005, 28, 51–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, D. A.; Kishon-Rabin, L.; Hildesheimer, M.; Karni, A. A Latent Consolidation Phase in Auditory Identification Learning: Time in the Awake State Is Sufficient. Learn. Mem. 2005, 12, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauptmann, B.; Reinhart, E.; Brandt, S. A.; Karni, A. The Predictive Value of the Leveling Off of Within-Session Performance for Procedural Memory Consolidation. Cogn. Brain Res. 2005, 24, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korman, M.; Raz, N.; Flash, T.; Karni, A. Multiple Shifts in the Representation of a Motor Sequence During the Acquisition of Skilled Performance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2003, 100, 12492–12497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauptmann, B.; Karni, A. From Primed to Learn: The Saturation of Repetition Priming and the Induction of Long-Term Memory. Cogn. Brain Res. 2002, 13, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karni, A.; Sagi, D. The Time Course of Learning a Visual Skill. Nature 1993, 365, 250–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyon, J.; Penhune, V.; Ungerleider, L. G. Distinct Contribution of the Cortico-Striatal and Cortico-Cerebellar Systems to Motor Skill Learning. Neuropsychologia 2003, 41, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golomer, E.; Crémieux, J.; Dupui, P.; Isableu, B.; Ohlmann, T. Visual Contribution to Self-Induced Body Sway Frequencies and Visual Perception of Male Professional Dancers. Neurosci. Lett. 1999, 267, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Aruin, A. S. The Effect of Short-Term Changes in Body Mass Distribution on Feed-Forward Postural Control. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2009, 19, 931–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M. J.; Kanekar, N. S.; Aruin, A. S. The Role of Anticipatory Postural Adjustments in Compensatory Control of Posture: 2. Biomechanical Analysis. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2010, 20, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, A. J.; Harris, L. R.; Bent, L. R. Visual Feedback Is Not Necessary for Recalibrating the Vestibular Contribution to the Dynamic Phase of a Perturbation Recovery Response. Exp. Brain Res. 2019, 237, 2185–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, D.; Kiemel, T.; Jeka, J. J. Asymmetric Sensory Reweighting in Human Upright Stance. PLoS One 2014, 9, e100418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanekar, N.; Aruin, A. S. Improvement of Anticipatory Postural Adjustments for Balance Control: Effect of a Single Training Session. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2016, 25, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horak, F. B.; Shupert, C. L.; Mirka, A. Components of Postural Dyscontrol in the Elderly: A Review. Neurobiol. Aging 1989, 10, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horak, F. B.; Nashner, L. M. Central Programming of Postural Movements: Adaptation to Altered Support-Surface Configurations. J. Neurophysiol. 1986, 55, 1369–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelnik, A. P.; Tasseel Ponche, S.; Andriantsifanetra, C.; Provost, C.; Calvalido, A.; Rougier, P. Walking with Eyes Closed Is Easier than Walking with Eyes Open without Visual Cues: The Romberg Task versus the Goggle Task. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2015, 58, 332–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutt, K.; Redding, E. The Effect of an Eyes-Closed Dance-Specific Training Program on Dynamic Balance in Elite Pre-Professional Ballet Dancers: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. J. Dance Med. Sci. 2014, 18, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horak, F. B.; Diener, H. C.; Nashner, L. M. Influence of Central Set on Human Postural Responses. J. Neurophysiol. 1989, 62, 841–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ooteghem, K.; Frank, J. S.; Allard, F.; Buchanan, J. J.; Oates, A. R.; Horak, F. B. Compensatory Postural Adaptations During Continuous, Variable Amplitude Perturbations Reveal Generalized Rather than Sequence-Specific Learning. Exp. Brain Res. 2008, 187, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, G. R. Triceps Surae Ia Proprioceptive Weighting in Postural Control During Quiet Stance with Vision Occlusion. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaravi Hesseg, R.; Gal, C.; Karni, A. Not Quite There: Skill Consolidation in Training by Doing or Observing in Motor Skill Acquisition. Learn. Mem. 2016, 13, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parreira, R. B.; Grecco, L. A. C.; Oliveira, C. S. Postural Control in Blind Individuals: A Systematic Review. Gait Posture 2017, 57, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campayo-Piernas, M.; Caballero, C.; Barbado, D.; Reina, R. Role of Vision in Sighted and Blind Soccer Players in Adapting to an Unstable Balance Task. Exp. Brain Res. 2017, 235, 1269–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwesig, R.; Goldich, Y.; Hahn, A.; Müller, A.; Kohen-Raz, R.; Kluttig, A.; Morad, Y. Postural Control in Subjects with Visual Impairment. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2010, 21, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakata, H.; Yabe, K. Automatic Postural Response Systems in Individuals with Congenital Total Blindness. Gait Posture 2001, 14, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaboda, J. C.; Barton, J. E.; Maitin, I. B.; Keshner, E. A. Visual Field Dependence Influences Balance in Patients with Stroke. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2009, 1147–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H.; Nakashizuka, M.; Uetake, T.; Itoh, T. The Effects of Visual Input on Postural Control Mechanisms: An Analysis of Center-of-Pressure Trajectories Using the Auto-Regressive Model. J. Hum. Ergol. (Tokyo) 2000, 29, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vidoni, E. D.; Boyd, L. A. Motor Sequence Learning Occurs Despite Disrupted Visual and Proprioceptive Feedback. Behav. Brain Funct. 2008, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).