Submitted:

12 December 2025

Posted:

12 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Dynamic Modeling of Transmission System

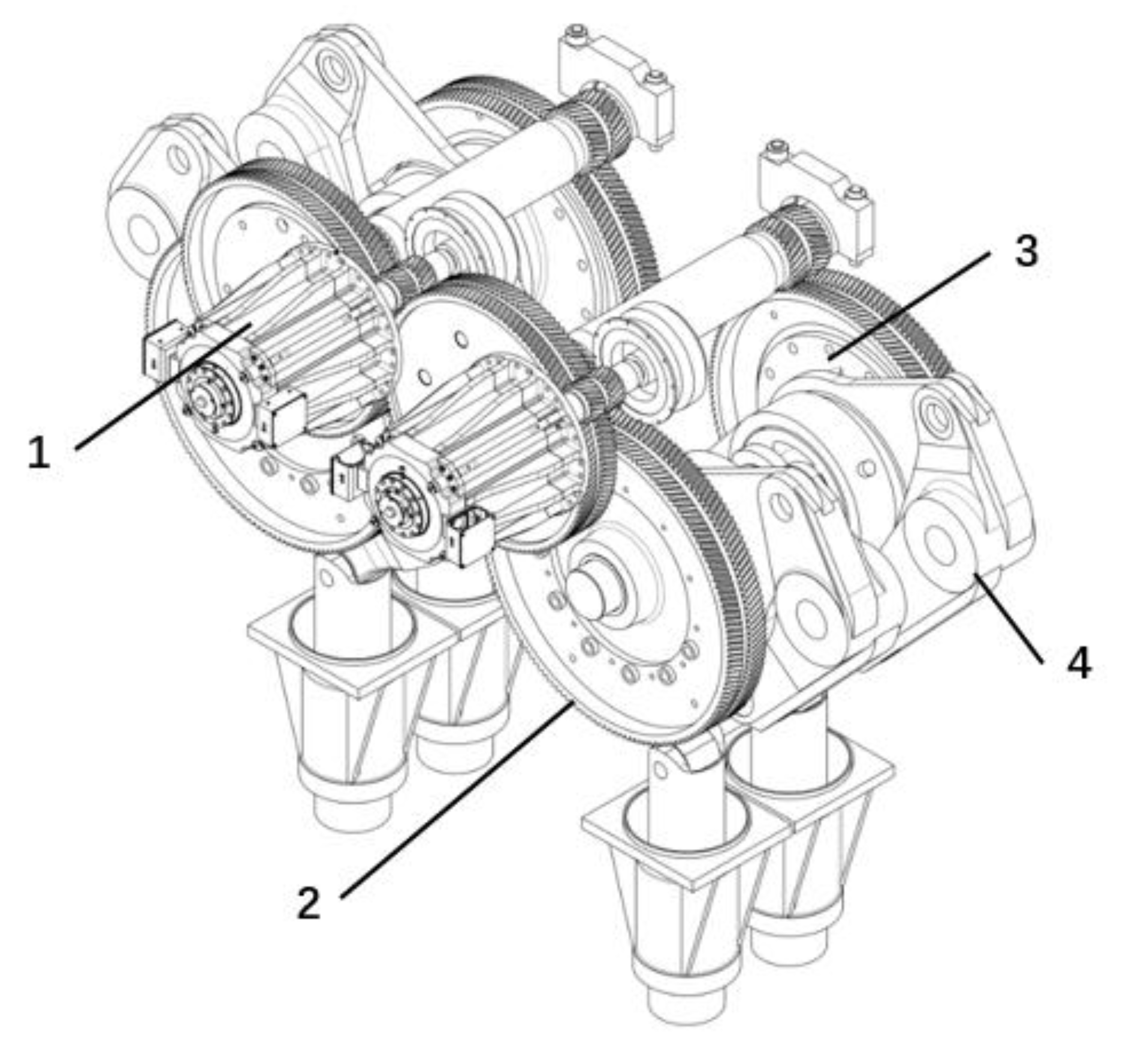

2.1. Mechanical Configuration of Servo Press Transmission Mechanism

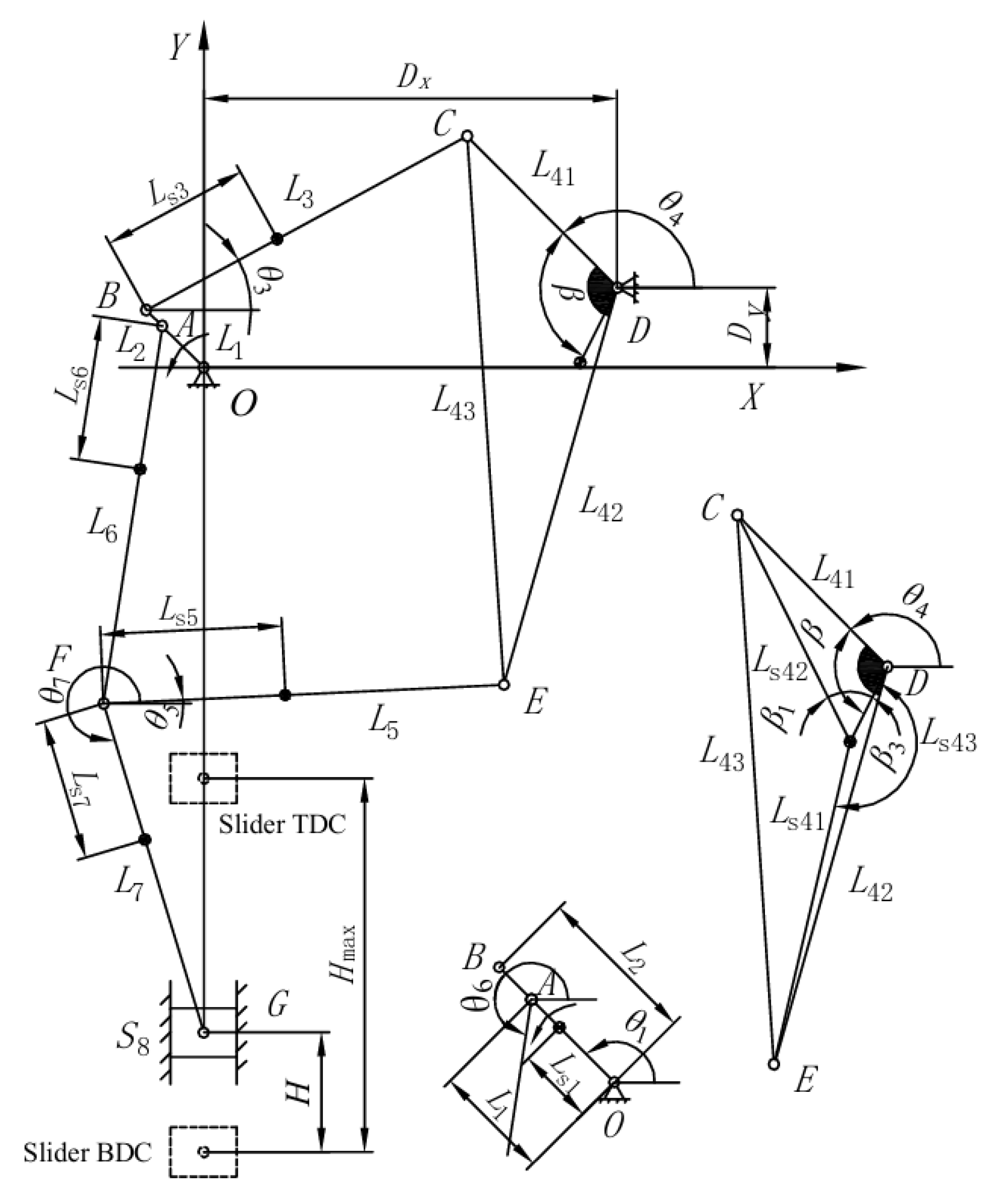

2.2. Dynamic Modeling of Eight-bar Mechanism

2.3. Generalized External Forces and Friction Modeling

2.3.1. Gravitational Force

2.3.2. Friction Modeling

2.3.3. Slide Balance Force

2.3.4. Stamping Process Force

2.3.5. Generalized External Force Integration

2.4. Servo Motor Drive Torque Modeling

3. Sensitivity Analysis and Identification of Dynamics Parameters

3.1. Definition and Classification of Theoretical Design Parameters

3.2. Sobol Global Sensitivity Analysis and Response Function Definition

3.2.1. Sobol Method for Global Sensitivity

3.2.2. Definition of Response Function

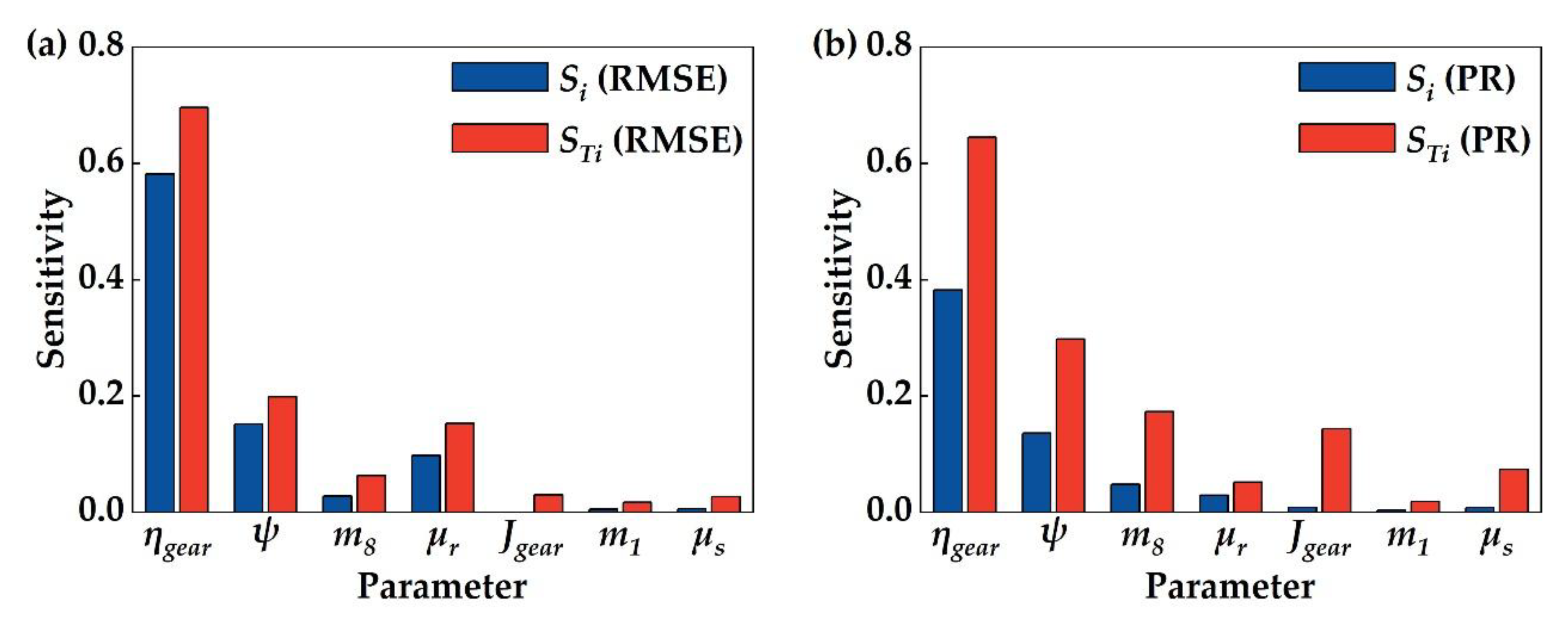

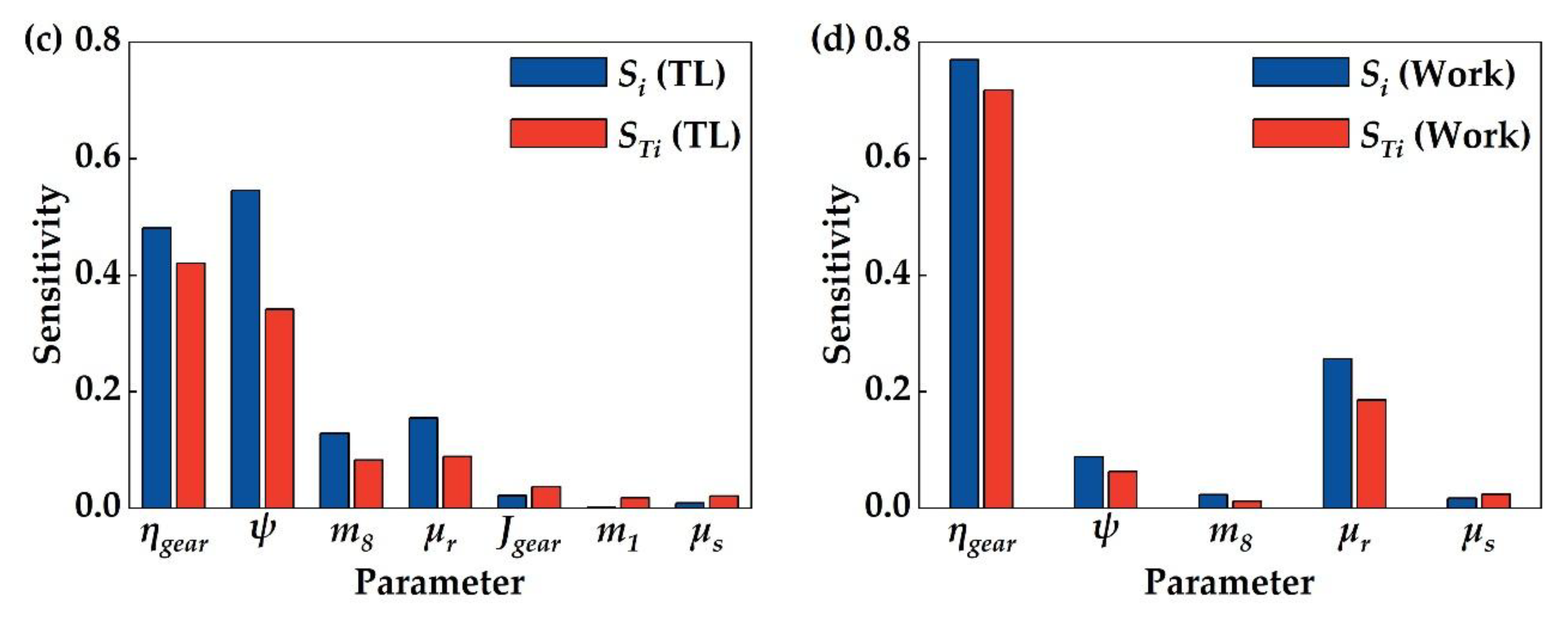

3.3. Sensitivity Analysis Results and Key Parameter Identification

3.4. Parameter Calibration Model

4. Experimental Verification and Engineering Application

4.1. Experiment Design for Model Calibration

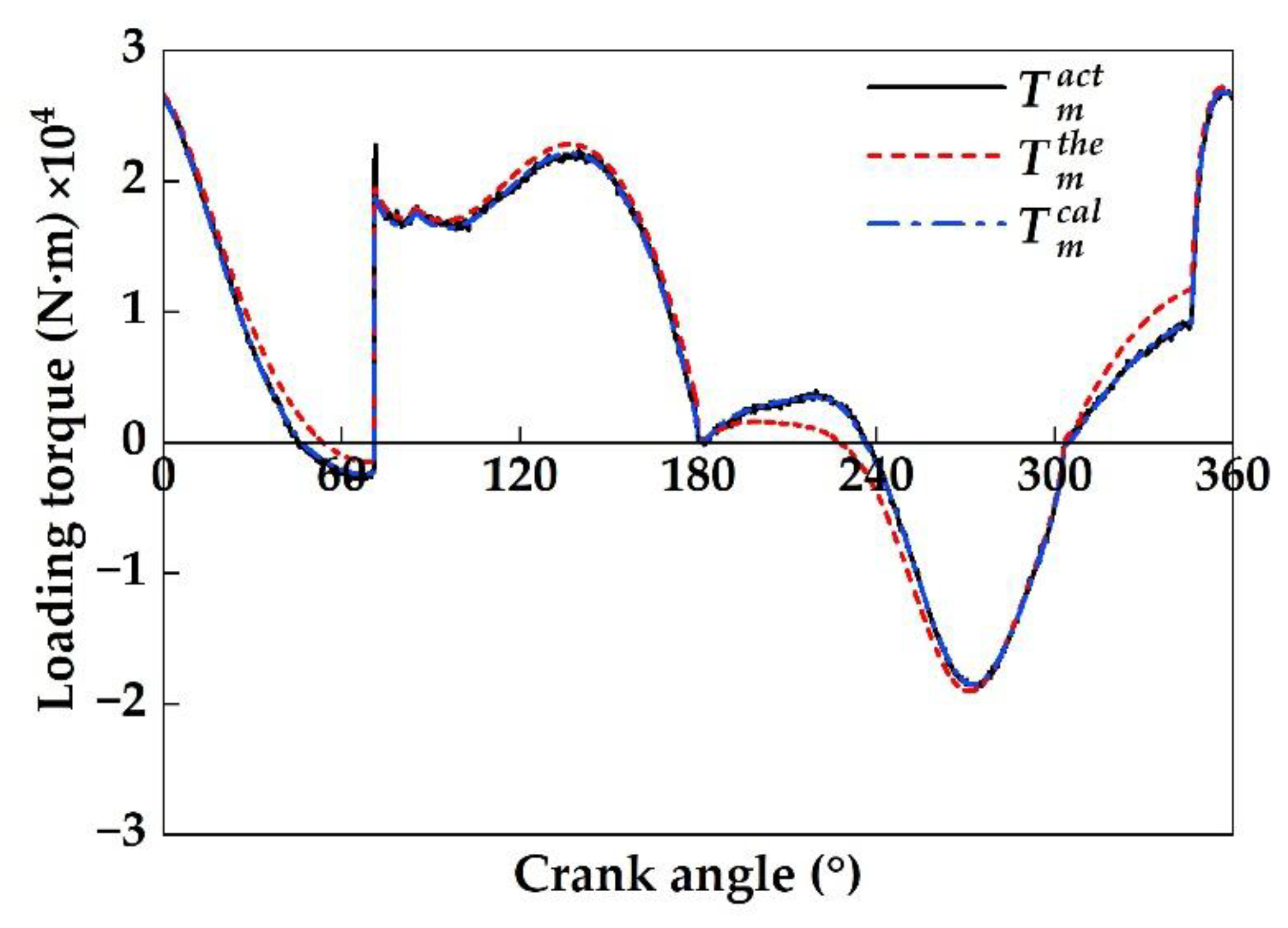

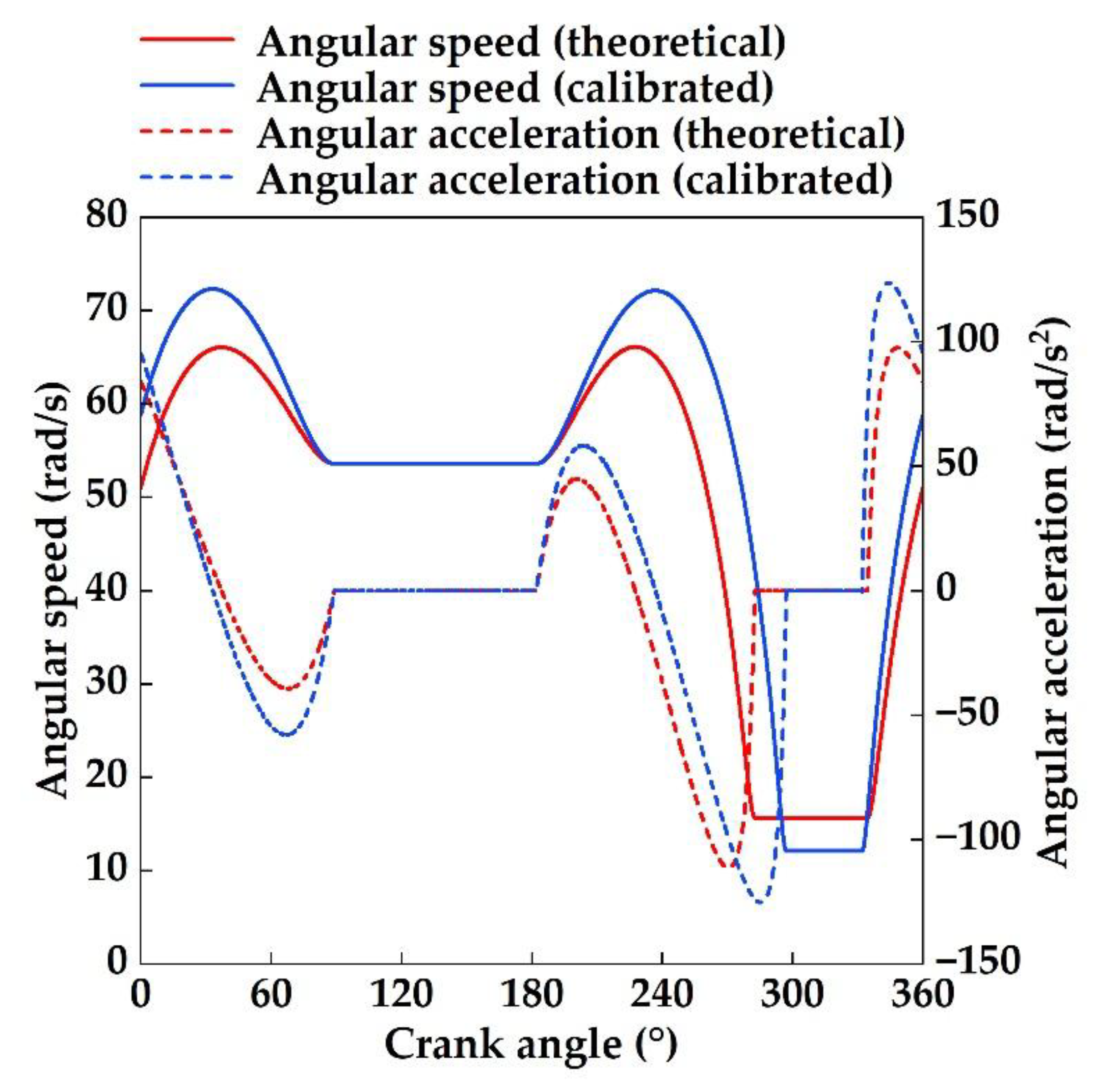

4.2. Calibration Results and Analysis

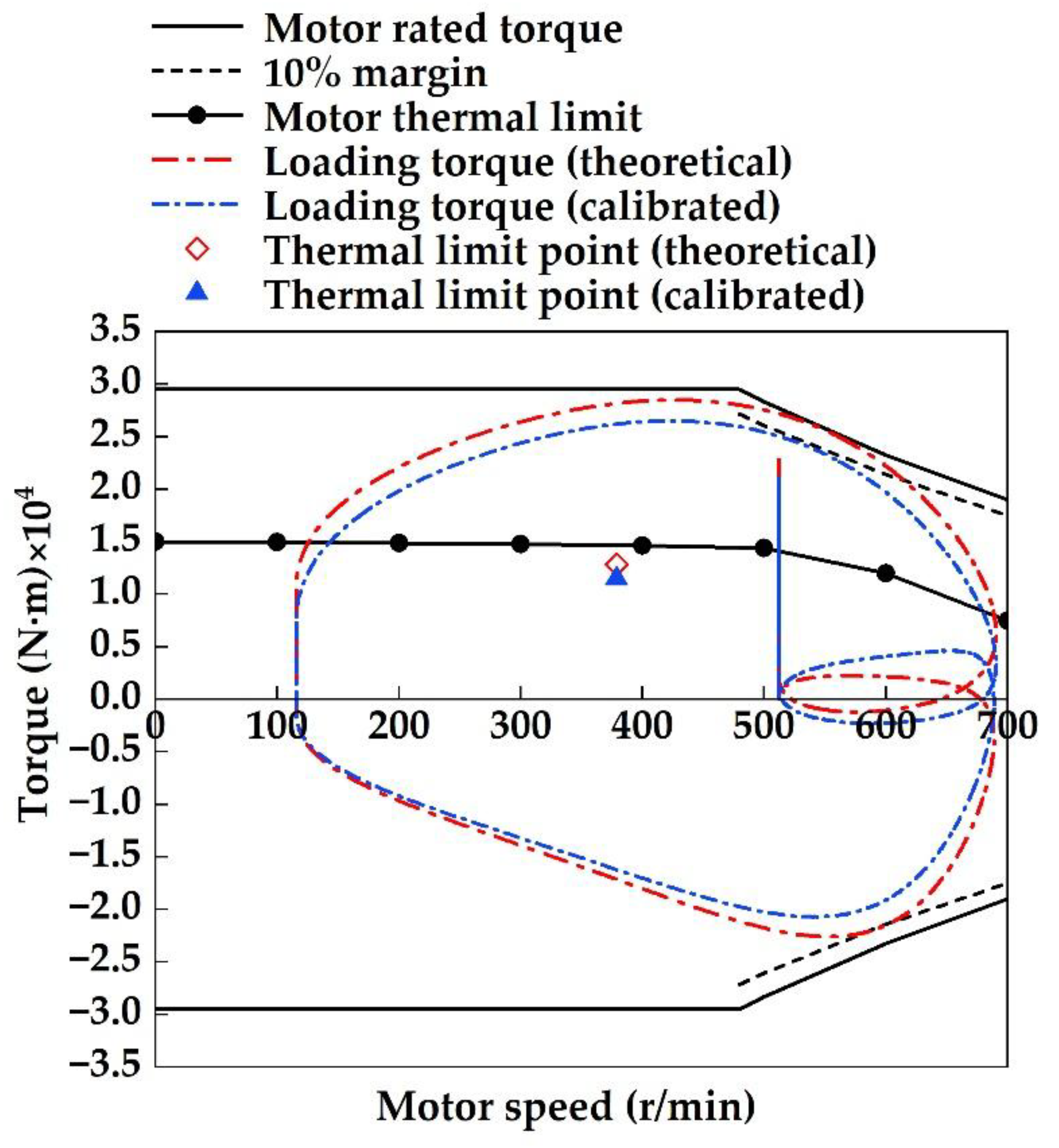

4.3. Engineering Application

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, J.Z.; Zhao, S.D.; Jiang, F.; Du, W.; Zheng, Z.H. A novel hollow two-sided output PMSM integrated with mechanical planetary gear: a solution for drive and transmission system of servo press. IEEE-ASME Transactions On Mechatronics 2022, 27(5), 3076–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, H.M.; Gao, J.B.; Xu, Y.L.; Rodriguez, J.; Kennel, R. Nonlinear-disturbance-observer-based model-predictive control for servo press drive. IEEE Transactions On Industrial Electronics 2024, 71(8), 8448–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.Z.; Luo, X.; Wang, X.S. Research and simulation analysis of fuzzy intelligent control system algorithm for a servo precision press. Applied Sciences-Basel 2024, 14(15). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaizola, J.; Esteban, E.; Trinidad, J.; Iturrospe, A.; Galdos, L.; Abete, J.M.; De, A.E.S. Integral design and manufacturing methodology of a reduced-scale servo press. IEEE-ASME Transactions On Mechatronics 2021, 26(5), 2418–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Lv, Y.; Kennel, R.; Rodriguez, J. Semiclosed loop based on predictive current control for spmsm drives during servo stamping. IEEE Transactions On Power Electronics 2024, 39(9), 11430–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K.; Gupta, A.; Krishnaswamy, H.; Chakkingal, U.; Banerjee, D.K.; Lee, M.G. Does friction contribute to formability improvement using servo press. Friction 2023, 11(5), 820–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.Z.; Zhao, S.D.; Li, J.X.; Jiang, F.; Du, W.; Zheng, Z.H.; Feng, Z.Y. A novel main drive system for the servo press: combination of integrated motor and symmetrically toggle booster mechanism. Journal of Manufacturing Science and Technology 2022, 37, 596–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.X.; Shu, Y.W.; Hu, W.T.; Zhao, X.H.; Xu, Z.C. Active vibration control of a mechanical servo high-speed fine-blanking press. Strojniski Vestnik-Journal of Mechanical Engineering 2021, 67, 445–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.L.; Gao, S.; Wang, T. Experimental verification of dynamic behavior for multi-link press mechanism with 2D revolute joint considering dry friction clearances and lubricated clearances. Nonlinear Dynamics 2022, 109(2), 707–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, O.J.; Thomas, R.; Michael, B.; Christian, J.; Friedrich, B. Expanding the forming limits of DP780 by adjusting ram slide motions on a mechanical servo press. Procedia CIRP 2025, 134, 503–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaizola, J.; Bouganis, C.S.; De, A.E.S.; Iturrospe, A.; Abete, J.M. Real-time servo press force estimation based on dual particle filter. IEEE TransactionsIndustrial Electronics 2020, 67(5), 4088–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, K.; Ni, J.; Zheng, H.; Sun, Y. Electromechanical coupling dynamic modeling and dynamic response analysis of servo press. International Journal of Non-Linear Mechanics 2025, 173, 104712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halicioglu, R.; Dulger, L.C.; Bozdana, A.T. Modeling, design, and implementation of a servo press for metal-forming applica-tion. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2017, 91, 2689–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, H.; Zhang, Y.J.; Song, Z.A.; Zang, C.Y.; Zhang, Q.L.; Lv, P.; Li, J.J. The influence of dynamic characteristics of six-bar linkage mechanical press transmission system on the accuracy of slide. Materials Research Proceedings 2024, 44, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.Y.; Li, W.W.; Chen, M.F.; Chen, Y. Research on optimization design of six-rod main transmission mechanism of Adams warm forging servo press. Forging & Stamping Technology 2020, 45, 112–116. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, T.; Xia, Q.X.; Long, J.C.; Long, X.B. A study on multi-domain modeling and simulation of precision high-speed servo nu-merical control punching press. In Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers Part I Journal of Systems and Control Engi-neering, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Song, Q.Y. Parameter calibration of main transmission system for heavy-duty servo press. Forming & Stamping Technology 2022, 12, 148–153. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Chen, X. Test study and nonlinear dynamic analysis of planar multi-link mechanism with compound clearances. Eur J Mech A Solids 2021, 88, 104260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; GoodAll, R.; Ren, L. Influences of car body vertical flexibility on ride quality of passenger railway vehicles. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part F: Journal of Rail and Rapid Transit. 2009, 223, 461−471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, H.Y.; Lu, L. Global sensitivity analysis of Earth-Moon transfer orbit parameters based on sobol method. International Journal of Aerospace Engineering 2022, 6587890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.Y.; Guo, B.F.; Li, J. Drawing motion profile planning and optimizing for heavy servo press. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2013, 69, 2819–2831. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.Z.; He, J.; Yue, Y. A new type of controllable mechanical press: motion control and experiment validation. J Manufac Sci Eng Trans ASME 2005, 127, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | ParameterValue |

| (kg·m2) | 54.4 |

| 0.917 |

| Component | Length (m) | Distance (m) | Mass(kg) | Moment of Inertia (kg·m2) |

| Link 1 | ||||

| Link 2 | ||||

| Link 3 | ||||

| Link 4 | ||||

| Link 5 | ||||

| Link 6 | ||||

| Link 7 | ||||

| Slide 8 | ||||

| Frame | ||||

| ° | ° | ° |

| Parameter | Symbol | ParameterValue |

| Friction coefficient of revolute joint | 0.028 | |

| Viscous damping coefficient of revolute joint (m·s/rad) | 2.5 | |

| Friction coefficient of slide joint | 0.12 | |

| Viscous damping coefficient of slide joint (N·s/m) | 3000 | |

| Inner radius of bearing at joint O (m) | 0.18 | |

| Inner radius of bearing at joint A (m) | 0.4925 | |

| Inner radius of bearing at joint B (m) | 0.595 | |

| Inner radius of bearing at joint C (m) | 0.1 | |

| Inner radius of bearing at joint D (m) | 0.14 | |

| Inner radius of bearing at joint E (m) | 0.09 | |

| Inner radius of bearing at joint F1 (m) | 0.175 | |

| Inner radius of bearing at joint F2 (m) | 0.175 | |

| Inner radius of bearing at joint G (m) | 0.06 |

| Parameter | Theoretical Value | CalibratedValue | Relative Error (%) |

| 0.917 | 0.842 | 8.9 | |

| 1.15 | 1.06 | 8.5 | |

| 0.028 | 0.012 | 133.3 | |

| 30595 | 32940 | -7.1 | |

| 54.4 | 60.6 | -10.2 | |

| 0.12 | 0.085 | 41.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or instructions referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).