1. Introduction

1.1. Aim and Scope

Since its inception information theory has permeated a number of fields: from electrical engineering, linguistic, biology to complex systems.

The purpose of this work is at least twofold: 1) serve as a form of index for material around Information Theory Laws, thus a story of information theory inequalities, 2) highlight some of the mechanisms around the existence and validity of these inequalities.

What for? Besides the intellectual pursuit of the task, there is a tight connection between these inequalities and the converse coding theorems. Do we need to recall the foundational and pervasive nature of these? To name a few, from communication channels, data compression (multimodal [

1]: text, audio, image video), error-correcting codes and data storage.

The present work does not aim to be a systematic or regular review of the field – even though it has some overlaps. The goal of this writing is to give a landscape view of the technical developments – of concern are the so-called Shannon information measures and in particular those of the form: Information Theory Laws. These stem from constraints on the entropy function. Since Shannon’s key work, the existence and variety of inequalities were unclear.

Initially, within this prime framework, the type of inequalities we encounter are called of Shannon-type. However, it turned out that they were others. In this work, we review and explore the milestones that were involved in unveiling the spectrum of these inequalities.

1.2. Genesis & Historical Lineage

Information Theory Laws are the object of our attention. Foundational to them is the concept of

entropy. From Rudolf Clausius [

2], passing by incarnations and variations: Boltzmann’s

statistical theory of entropy [

3], Gibbs’s

statistical mechanics [

3], von Neumann [

4]’s

quantum systems1, Brillouin [

6]’s

negentropy,

Rényi entropy [

7] – a generalized form of Shannon’s measure. Our starting point will be with Claude Shannon which laid down the foundations of information theory (IT).

As mentioned in the previous Section (

1.1), we purposely start our recollection with the seminal

2 work of C.E. Shannon and the introduction of the concept of

Shannon Entropy in:

A Mathematical Theory of Communication [

8].

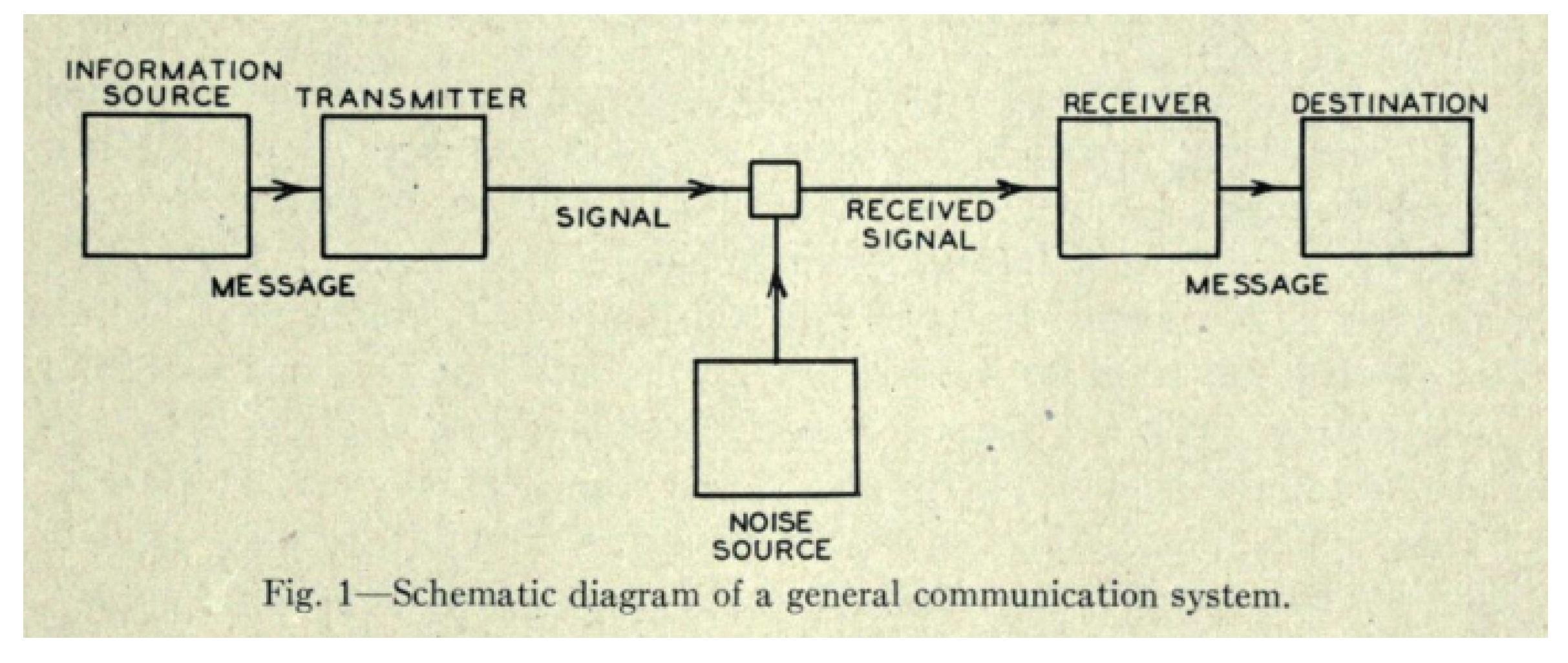

Figure 1.

General Communication Channel – Source: Shannon [

9]. This figure can be seen as one of the early artifacts of the digital age.

Figure 1.

General Communication Channel – Source: Shannon [

9]. This figure can be seen as one of the early artifacts of the digital age.

This apparent simplicity could be the key to information theory pervasiveness across disciplines and theories. Indeed, from binary stars in cosmology, passing by: sexual reproduction in biology, deep learning models in artificial intelligence, to the presence of natural hydrogen; dyadic systems seem to carry weight in the universe.

Furthermore, this appearance can be in a superposition of state or, juxtaposition with the following observations. From circuits, digital computers, analog-to-digital converters to digital physics; binary is the alphabet, its symbols: , a cardinality of and binary entropy expressed in . Additionally, the very nature of the number (symbol) 2 originally (Arab numbers) comes from the fact that its writing delimits two (2) angles.

This begs a fundamental question of whether:

2 in its different embodiment characterizes equality

3 or not.

We propose to answer this question using the following lens. What differentiate the DNAs of homo sapiens sapiens from the bonobos is not expressed in their equal strains but in the parts that differentiate them.

Similarly, our object of interest is rooted in linear inequalities and the constraints that are applied upon them. It is through the interplay of constraints on these inequalities that emerge complexity.

Hence, our study will revolve around linear inequalities of information measures and their particularities.

1.3. Paper Structure

This work is structured as follows:

We start with by reviewing the necessary material to understand the so-called Information Theory Laws,

Secondly, we linger on the two main flavors of information inequalities i.e.: Shannon-type and non-Shannon-type inequalities before focusing on the Information Theory Laws and bringing the attention to

In third, we propose two retrospects: 1) on the machine-assisted verification relation of information inequalities, 2) on the evolution of research with respect to the complexity verification task of these inequalities.

Finally, we close this study with our impressions left by the work and exploration of this field.

2. Preliminaries and Main Concepts

The following are definitions are taken from [

11,

12]. Thus for a

complete mathematical profile i.e. the domain and image within which they are defined and operate; the interested reader should refer to these works.

2.1. Definitions: Shannon Information Measures

2.1.1. Shannon Entropy

The

Shannon Entropy is defined as:

2.1.2. Entropy Function –

For a collection

of

n random variables, define the set function

by:

with

because

is a constant.

is called the

entropy function of

(which is a collection of discrete random variables).

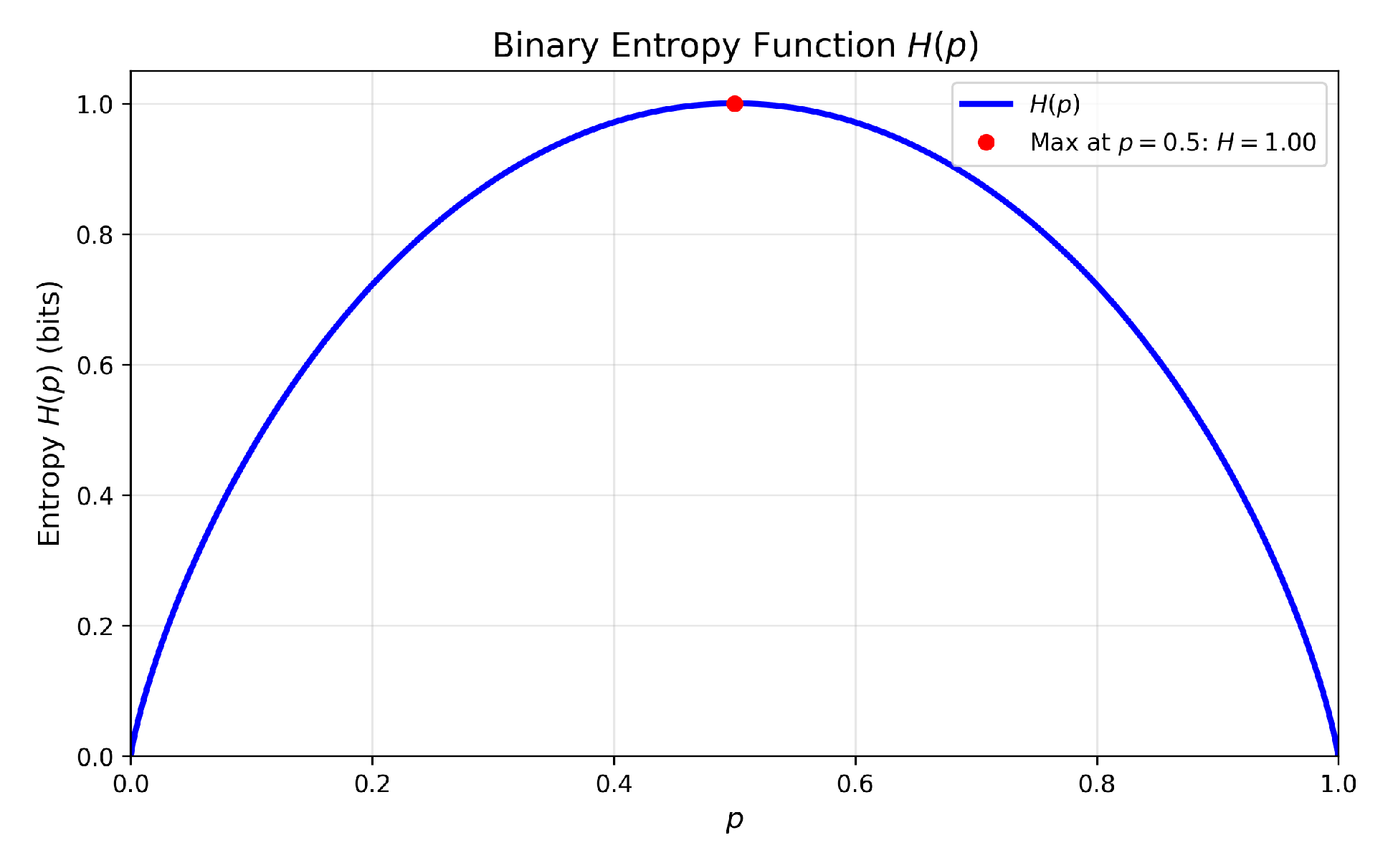

Binary Entropy Function

One of the most commonly used

is the binary form:

Figure 2.

Binary Entropy Function.

Figure 2.

Binary Entropy Function.

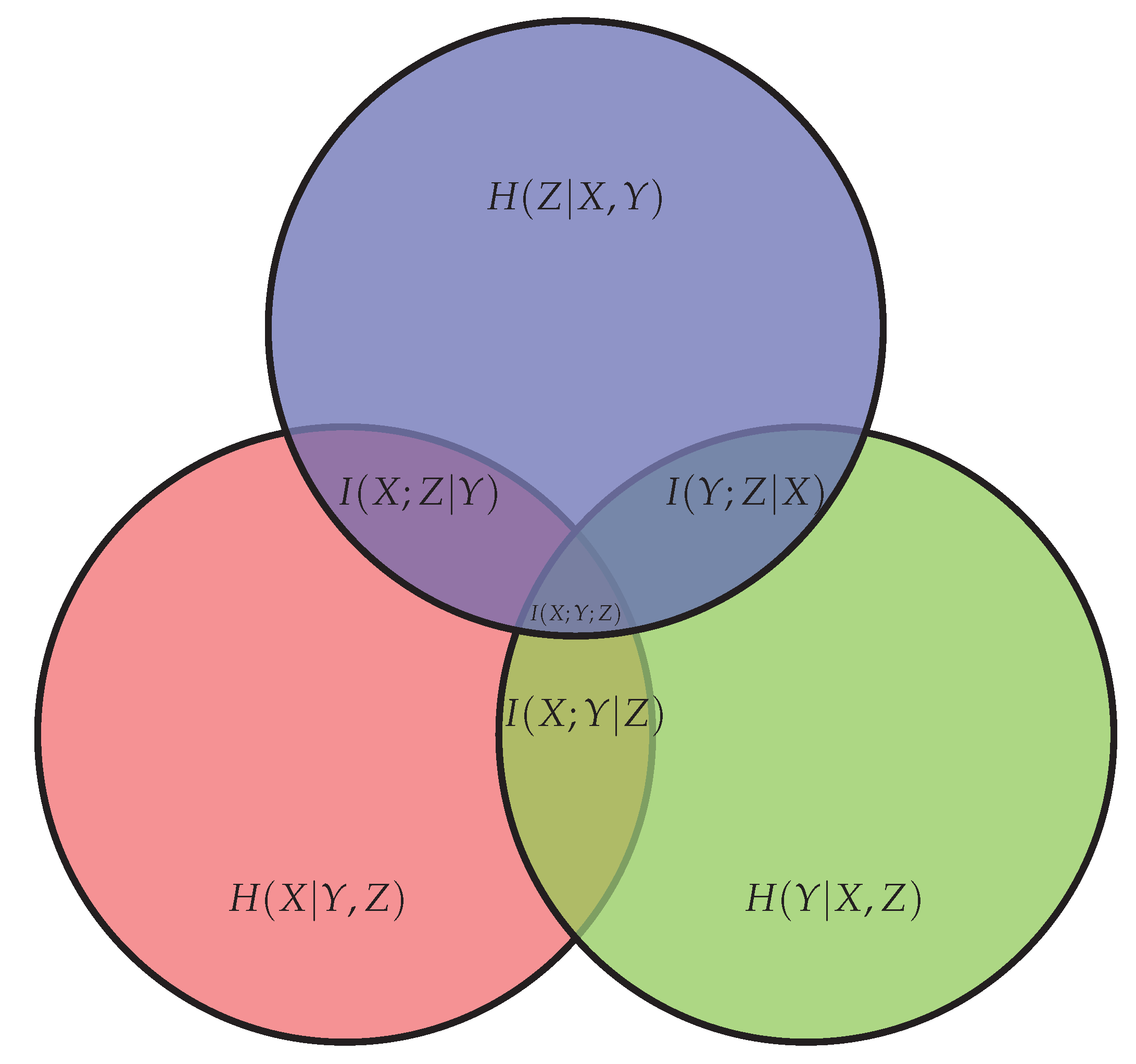

2.1.3. Conditional Entropy, Conditional and Mutual Information

- -

(

3) – Conditional Entropy,

- -

(4) – Mutual Information,

- -

(5) – Conditional Mutual Information.

These definitions (2.1.1, 3, 4, 5) are what define Shannon information measures and they are usually presented using the following Venn diagram:

We can observe that the joint entropy of random variables

is given by:

From (discrete) random variables,

Shannon information measures can be built and expressed as linear combinations of

joint entropies.

The concept of

linear combination is also of importance. To be expressed, they need a mathematical

space (

) which will be explored in the following sections. In this study, we work with

linear information inequalities, the case of

linear information equalities being a particular instance (

A.1).

2.1.4. Entropy Space –

As defined in [

12][p.326], the

entropy function () evolves in a

k-dimensional Euclidean space with coordinates labeled by , where corresponds to the value of for any collection Θ of n random variables – it precedes that, by definition

is in

[

11].

Where an

entropy function can be represented as a column vector in an

entropy space of

n random variables. A particular column or entropy vector

is called

entropic if it equates with the

entropy function [

12].

2.1.5. {Entropy, Shannon} Regions –

These entropic vectors describe a region in

such that:

defines a region of entropy functions also called the

entropy region[

11]. In other words, it is a subset of

of all entropy functions defined for

n discrete random variables.

Moreover, with

f representing the linear combination of some

Shannon information measures, we have that, an entropy inequality such as:

is valid if and only if [

11][p.91]:

is the closure of

– more on that in Section (

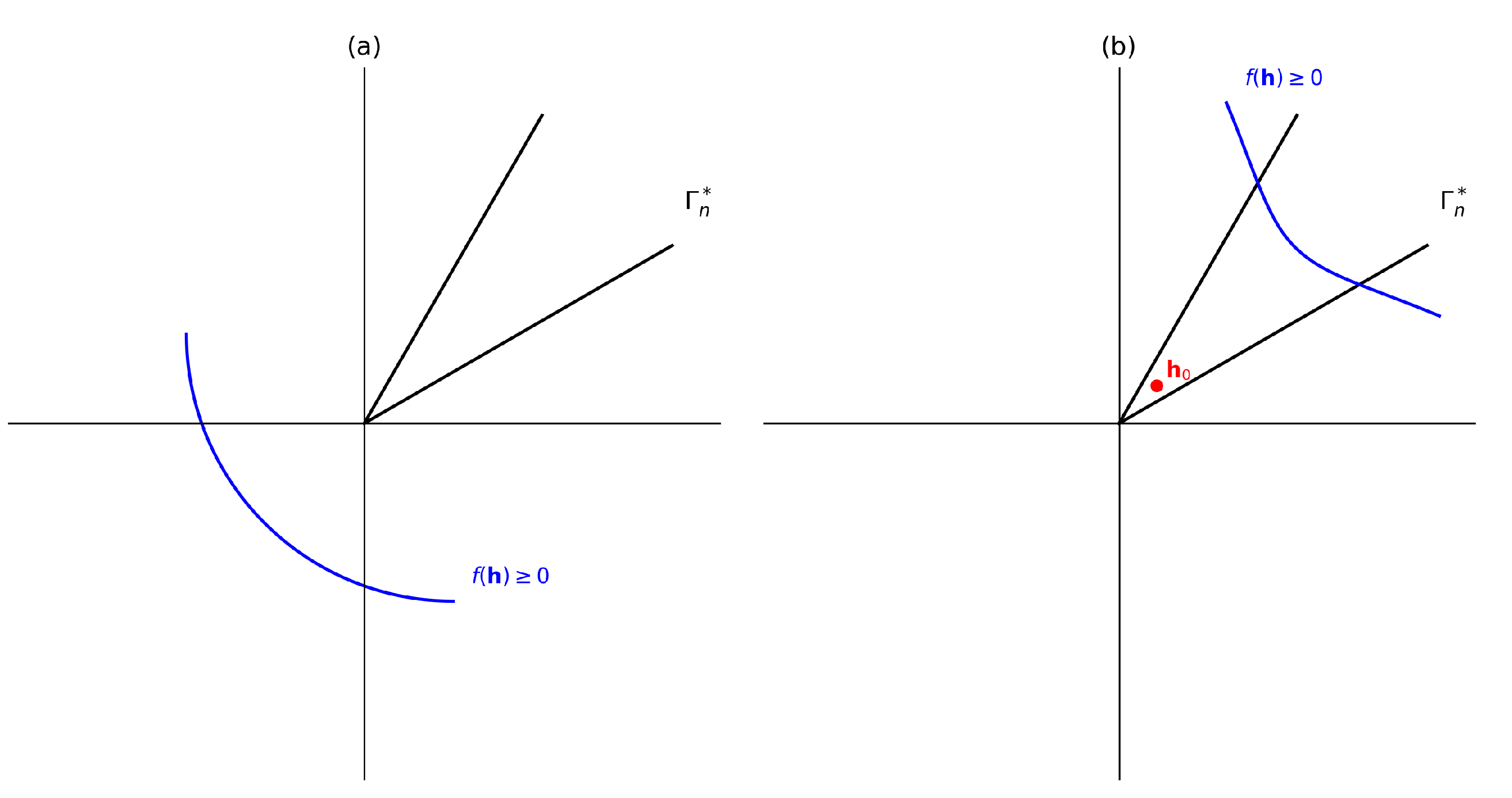

2.4). Now, the inequality of the form

only exists because of the half-space closure, giving:

This relation between

and

and the property

is illustrated in

Figure 3.

The

basic linear inequalities (

2.2) exist in a region called

Shannon region:

:

– that is because the

basic linear inequalities are satisfied by any random variable.

More generally, the

nonnegativity is one of the properties of

polymatroids, a necessary but not sufficient property, which we look into in

Section 2.4.

2.2. Linear Inequalities

The previous definitions: (

2.1.3) constitute what is commonly referred to the:

Shannon Information Measures:

Source: Yeung [

11][p.90]

Similarly to classical

linear algebra, the

Shannon information measures are built through

linear combination of

joint entropies which leads to the

canonical form construction which is

unique [

12][Corollary 13.3, p.328]. That is, an

information expression can be written as a function of linear entropy combinations; using

n discrete random variables, we observe:

joint entropies.

The presented

basic linear inequalities are not “atomic” that is, they do not form a

minimal set; some expressions can be implied by information identities (

B.1) [

12,

13].

The reduced set version of these inequalities is called the elemental forms.

Theorem 1 (II.1 [

13])

. [14] Any Shannon’s information measure can be expressed as a conic combination of the following two elemental forms of Shannon’s information measures:

i)

ii) , where and .

2.3. Geometric Framework

As touched upon in the introduction (

1), being able to evaluate an information inequality is of importance.

The

basic linear inequalities are expressed on the

region (

10). Under the hood, they are joint entropies expressed in a vector form.

Thus, the

geometric framework introduced by Ho et al. [

15] is a powerful way to study them and allows for:

- -

The identification of Shannon-type inequalities through the use of a geometric form and an interactive theorem verifier i.e. an automated way to generate, verify and prove inequalities built from the canonical form,

- -

Proving “statements” that an

algebraic-only approach could not [

12,

15].

The concern is to verify the correctness of an information inequality by either:

The difficulty begins when there is more than three variables at play. Thus, requiring the need for a more powerful strategy and with automation. These are some of the motivations behind Ho et al. [

15] and we will highlight its main approach.

The dialectic between

algebraic and

geometric forms is articulated in Ho et al. [

15] and, they proceed with the following observation/statement.

When, an inequality cannot be determined by the interactive theorem prover

4, their resolution branches as follows:

The main insight can be summed up as follows: isolated, the geometric approach which embodies the primal problem, cannot discriminate between: 1) the non-Shannon-type inequalities evaluated as true and, 2) the invalid inequalities. This is where the prover comes into play to figure out if it is possible to construct an analytical proof.

2.4. Polymatroid Axioms

The

basic linear inequalities are

nonnegative, this constitutes one of the

polymatroid properties – this was showed by Fujishige [

16]. The Shannon information measures we deal with are discrete random variables for which we have

possible

joint entropies which must satisfy these axioms.

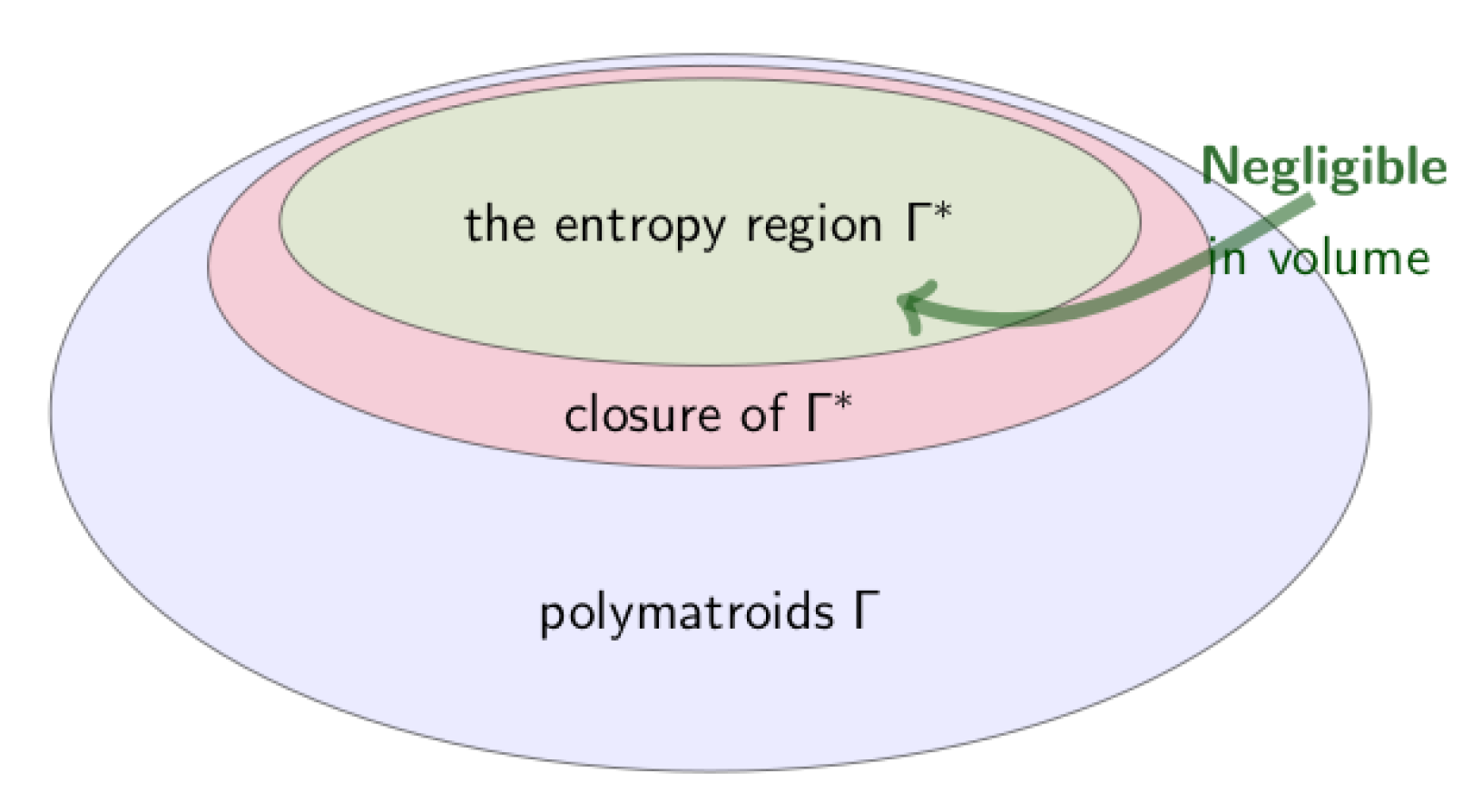

They are defined in the entropy space () where different regions are described:

- -

The region (Shannon region) consists of all vectors that satisfy the elemental inequalities,

- -

The region describes the space of entropic vectors that corresponds to actual entropy functions for some d.r.v. collection (). A vector is called entropic if and only if it belongs to .

- -

The region is the closure of – also called the almost entropic region.

In Section (

2.1.5), we discussed the

regions and its closure

[

11][p.93].

The following

Figure 4 gives a visual illustration of these relations:

The following

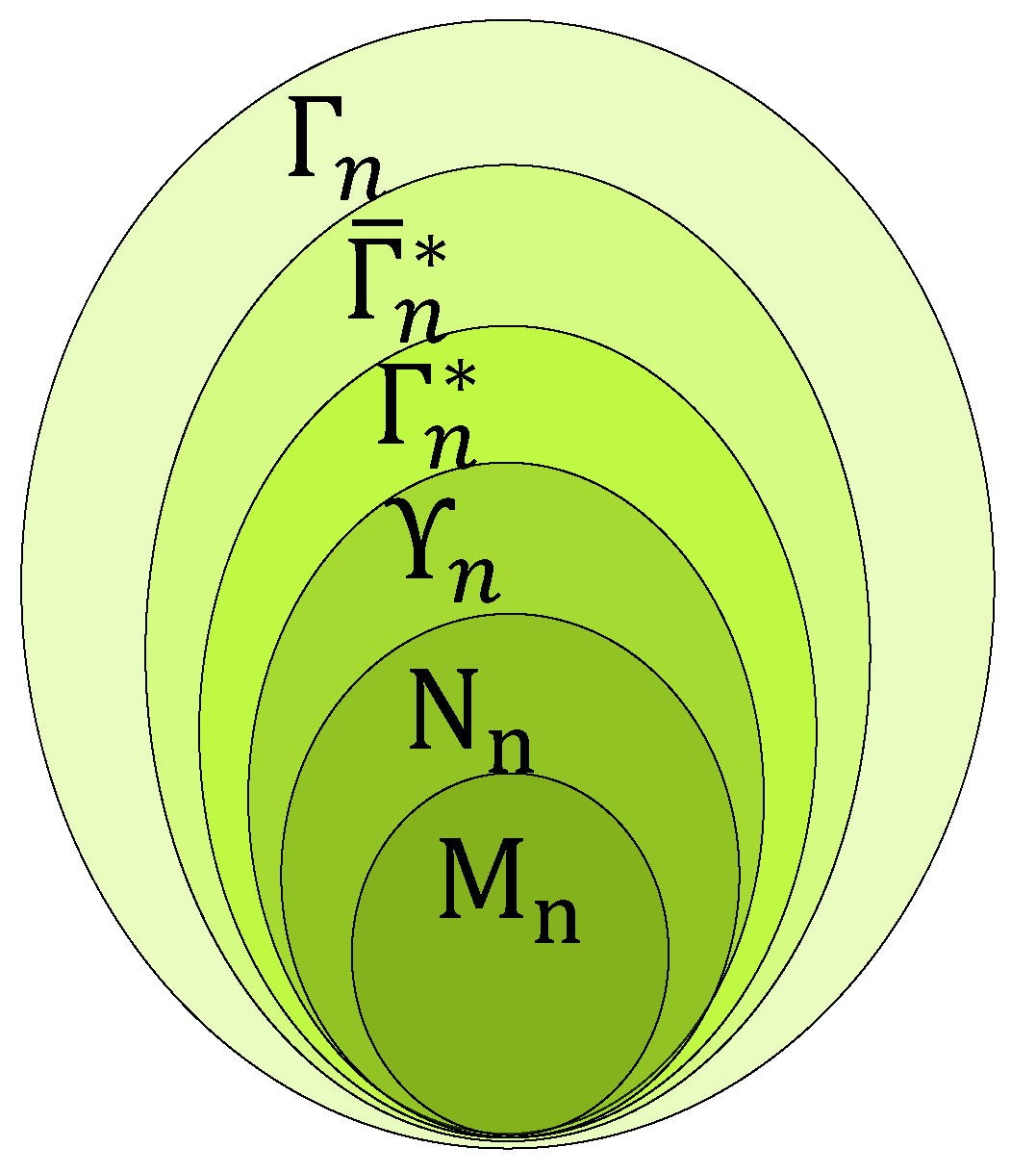

Figure 5 gives a hierarchical view of polymatroids with the entropy regions:

Where:

Table 1.

Landscape of Polymatroids – Source: Suciu [

18].

Table 1.

Landscape of Polymatroids – Source: Suciu [

18].

| Symbol Region |

Meaning |

|

Modular Polymatroids |

|

Normal Polymatroids |

|

Group Realizable |

|

Entropic |

|

Almost-Entropic |

|

Polymatroid |

When n the number of variables is not specified then is expressed as . In this text, we are interested in the entropic, almost-entropic and polymatroid.

It should be noted that for , the closure and convexity are not defined.

- -

,

- -

but i.e. is the smallest cone containing (),

- -

.

This last point is of interest because it allows the existence of

unconstrained non-Shannon-type inequalities [

11] (

Section 3.2).

Additionally, we report the following results [

21]:

- -

Little is known for behavior for and for given ,

- -

In general, is a convex cone,

- -

2.4.1. Polymatroids Visualizations

In this section, to support understanding and intuition, we gather and propose visualizations of objects used in the study of information inequalities.

These include:

A polymatroid convex cone in and the concept of facet,

The hierarchy relation between elemental inequalities, basic inequalities and the Shannon region () for r.d.v.,

A

conceptual illustration of the ZY98 [

22]

unconstrained non-Shannon-type inequality (

Figure 8) and, with two additional configurations: 1) one with the ZY98 inequality closure representation (

Figure 9), 2) a comparison with the case where

(

Figure 10).

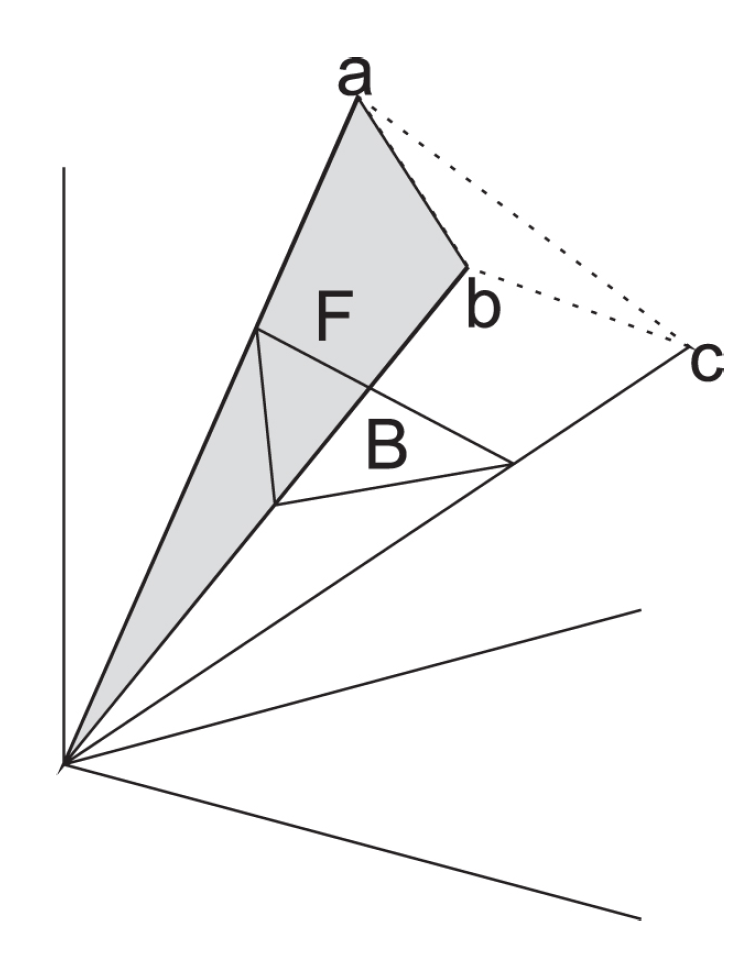

1. Illustration: Polymatroid convex cone and a facet:

Figure 6.

Illustration of a convex cone in

, where the surface F represents one of its facets and extremal rays are:

– Source: [

23][Figure 2]

Figure 6.

Illustration of a convex cone in

, where the surface F represents one of its facets and extremal rays are:

– Source: [

23][Figure 2]

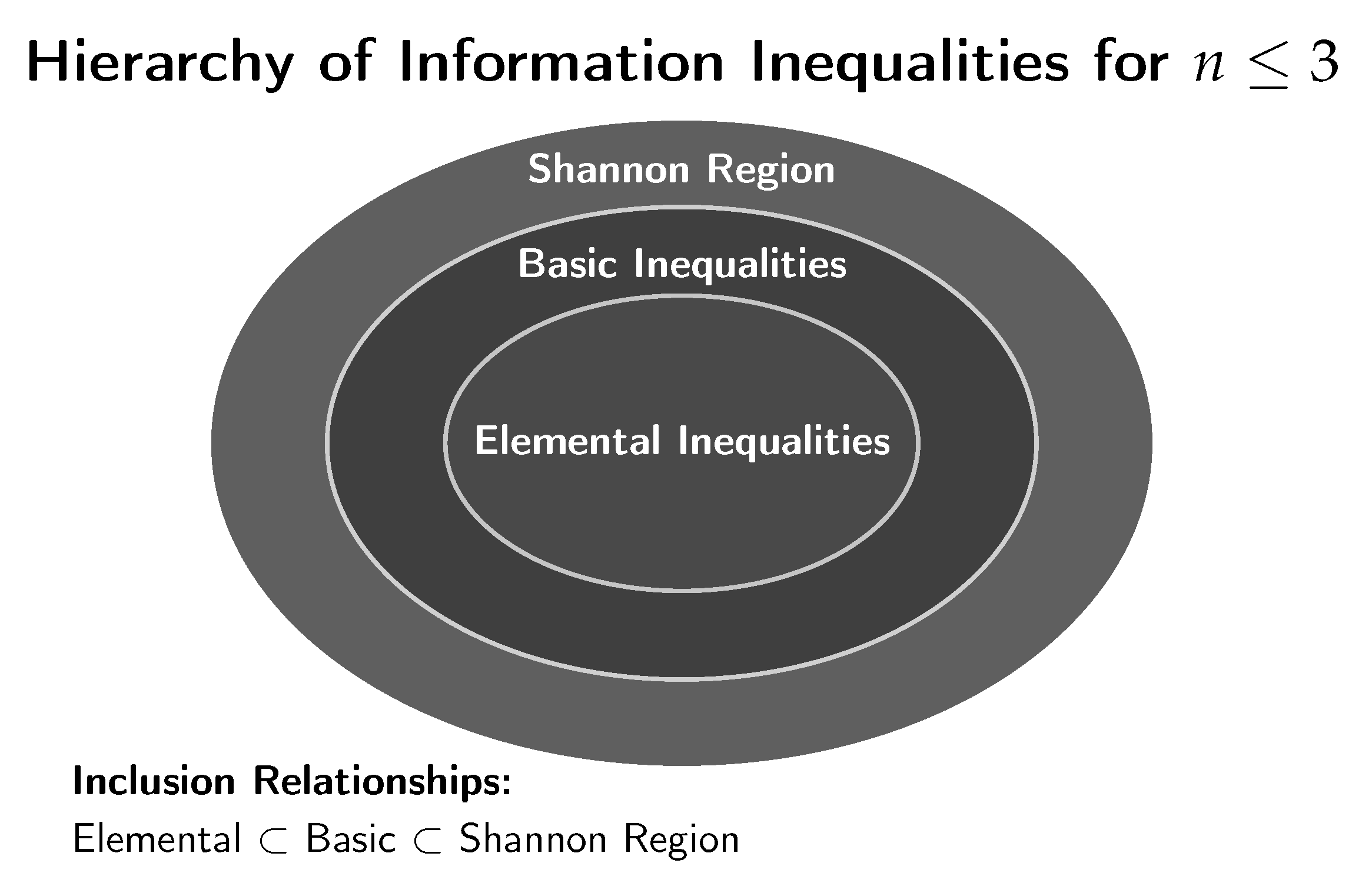

2. Illustration: Hierarchy of Information Inequalities for :

The regions for can be visualized as follows:

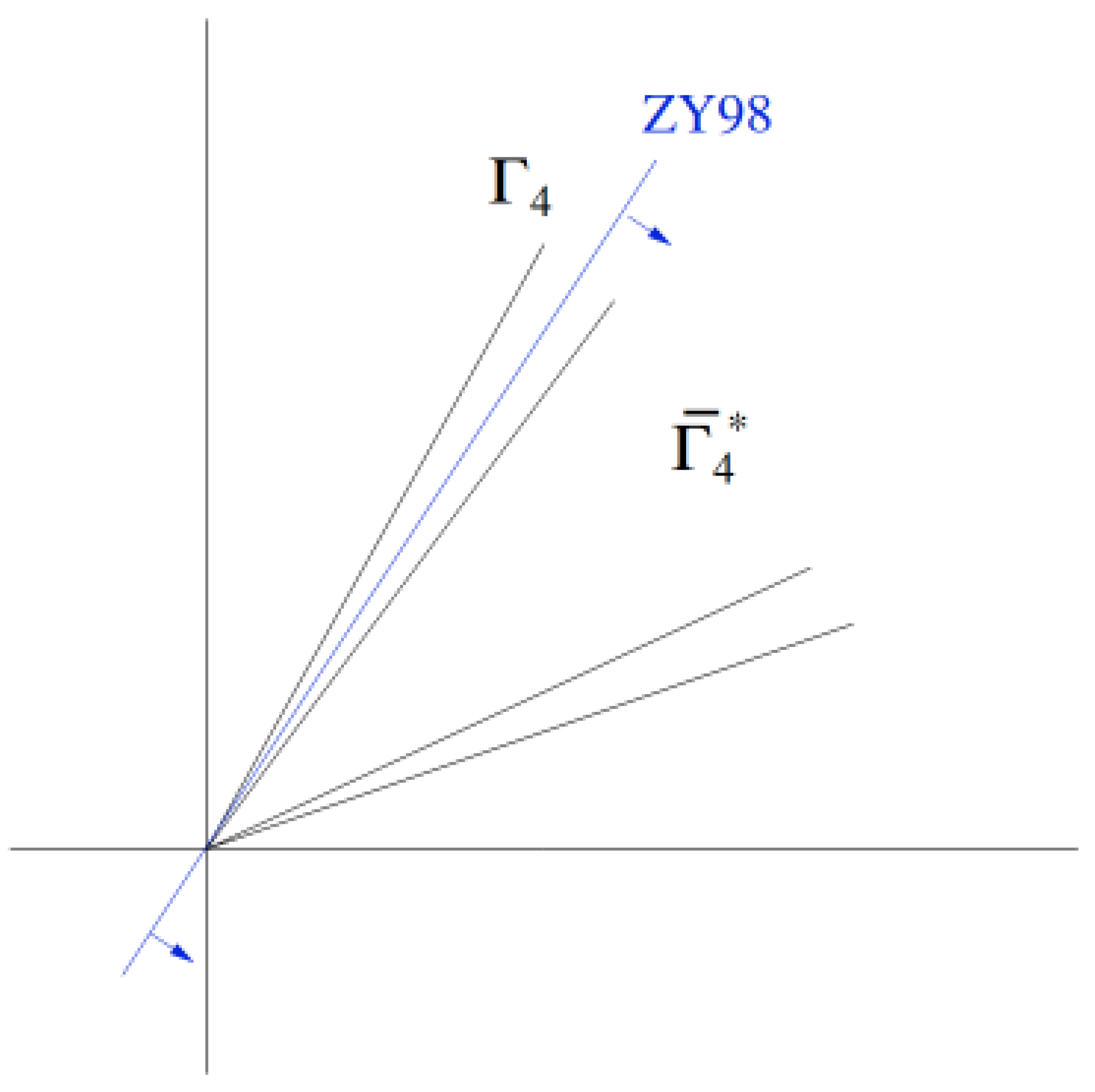

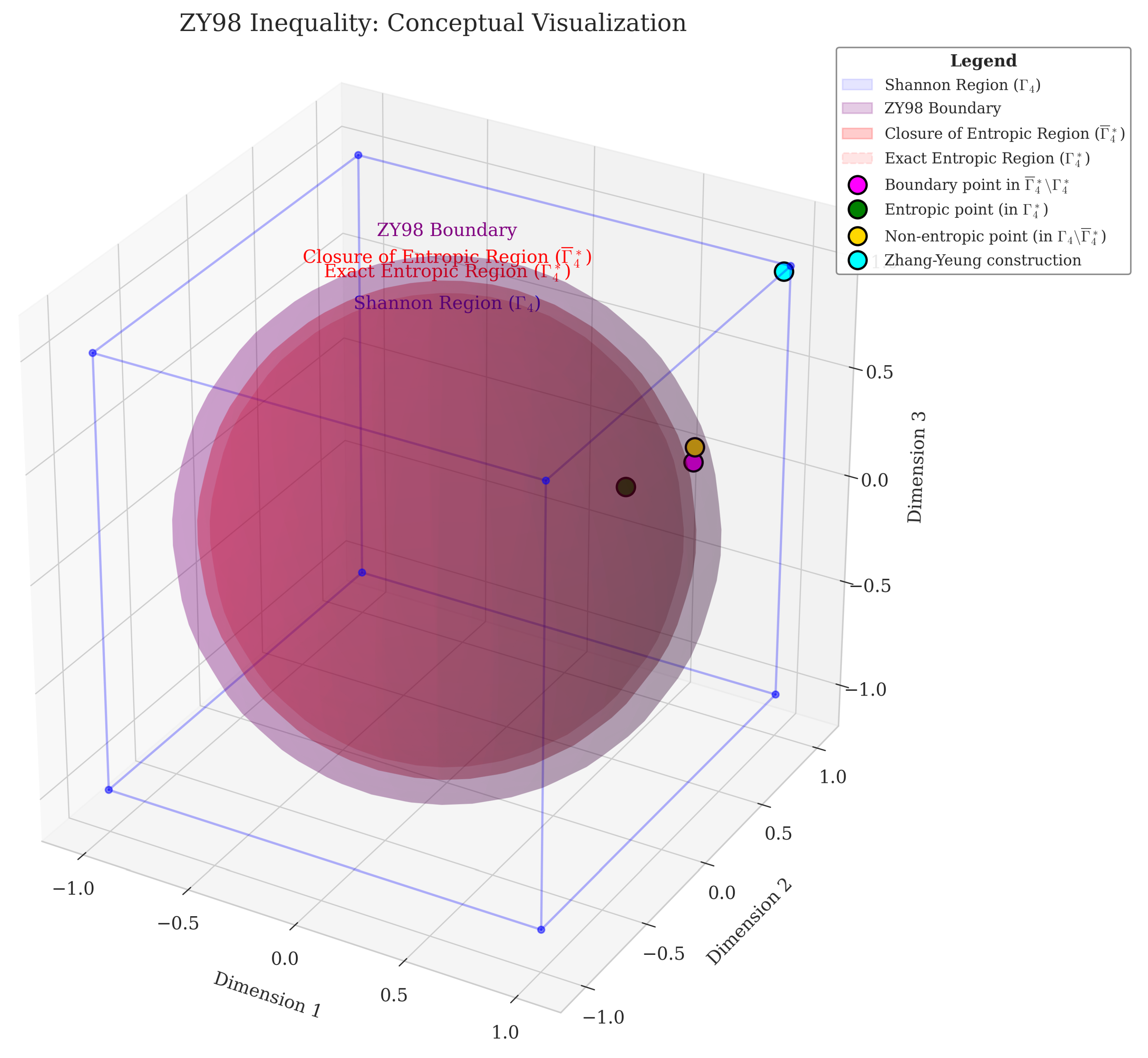

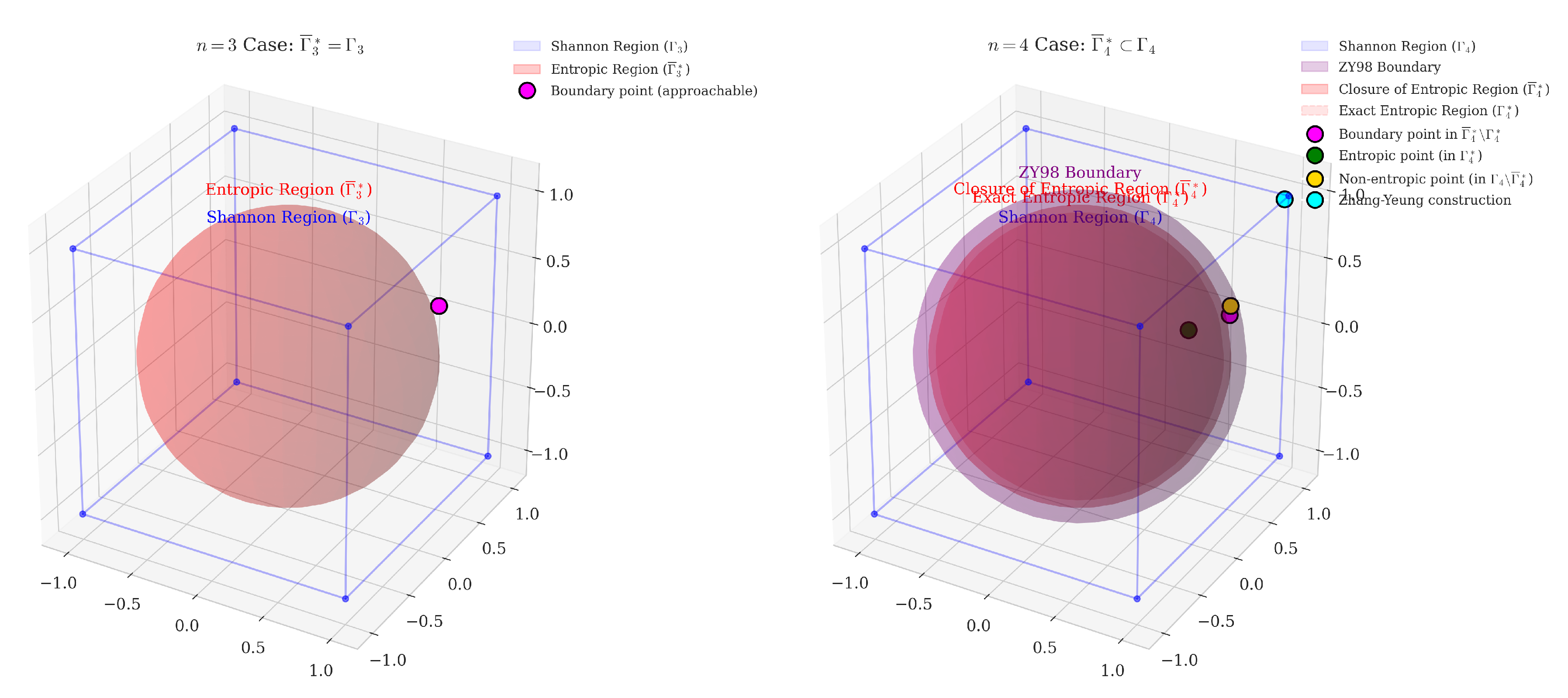

3. Illustration: The ZY98 unconstrained non-Shannon-type Inequality:

Being the first

unconstrained non-Shannon-type inequality (ZY98) to be discovered, it is a landmark in the field [

22]. In addition, to the illustration given in [

11], we propose an additional

conceptual visualization using a

cube and sphere metaphor.

We proceed as follows: 1) we recall the theorem (2) 2), we present the illustration given in Yeung [

11][p.94] (

7) and 3), we propose our visualization (

8).

Theorem 2 (ZY98).

For any four random variables

Source: Zhang and Yeung [

22]

And its illustration as provided in [

11][p.94]:

Figure 7.

ZY98 Inequality – Source: Yeung [

11][p.94]

Figure 7.

ZY98 Inequality – Source: Yeung [

11][p.94]

We propose the following

3D conceptual visualization:5

Figure 8.

The ZY98 inequality defines a boundary that separates the closure of the () from the gap within the Shannon region (). Points in the gap satisfy all Shannon-type inequalities but cannot be realized by any joint probability distribution, and cannot even be approached arbitrarily closely by entropic points.

Figure 8.

The ZY98 inequality defines a boundary that separates the closure of the () from the gap within the Shannon region (). Points in the gap satisfy all Shannon-type inequalities but cannot be realized by any joint probability distribution, and cannot even be approached arbitrarily closely by entropic points.

The figure illustrates the ZY98 inequality (2), where:

- -

(Exact Entropic Region) is the sphere in red,

- -

The closure of Exact Entropic Region ,

- -

The purple surface is the ZY98 boundary defined by the ZY98 inequality,

- -

(Shannon region) is the cube in blue – points satisfying the basic inequalities,

- -

Magenta point(s): boundary points in ,

- -

Green point(s): entropic points in ,

- -

Gold point(s): non-entropic points in (satisfying basic inequalities but non-entropic),

- -

Cyan point(s): Zhang-Yeung construction along the

extreme ray [

20].

The insight is that for , we have , not just .

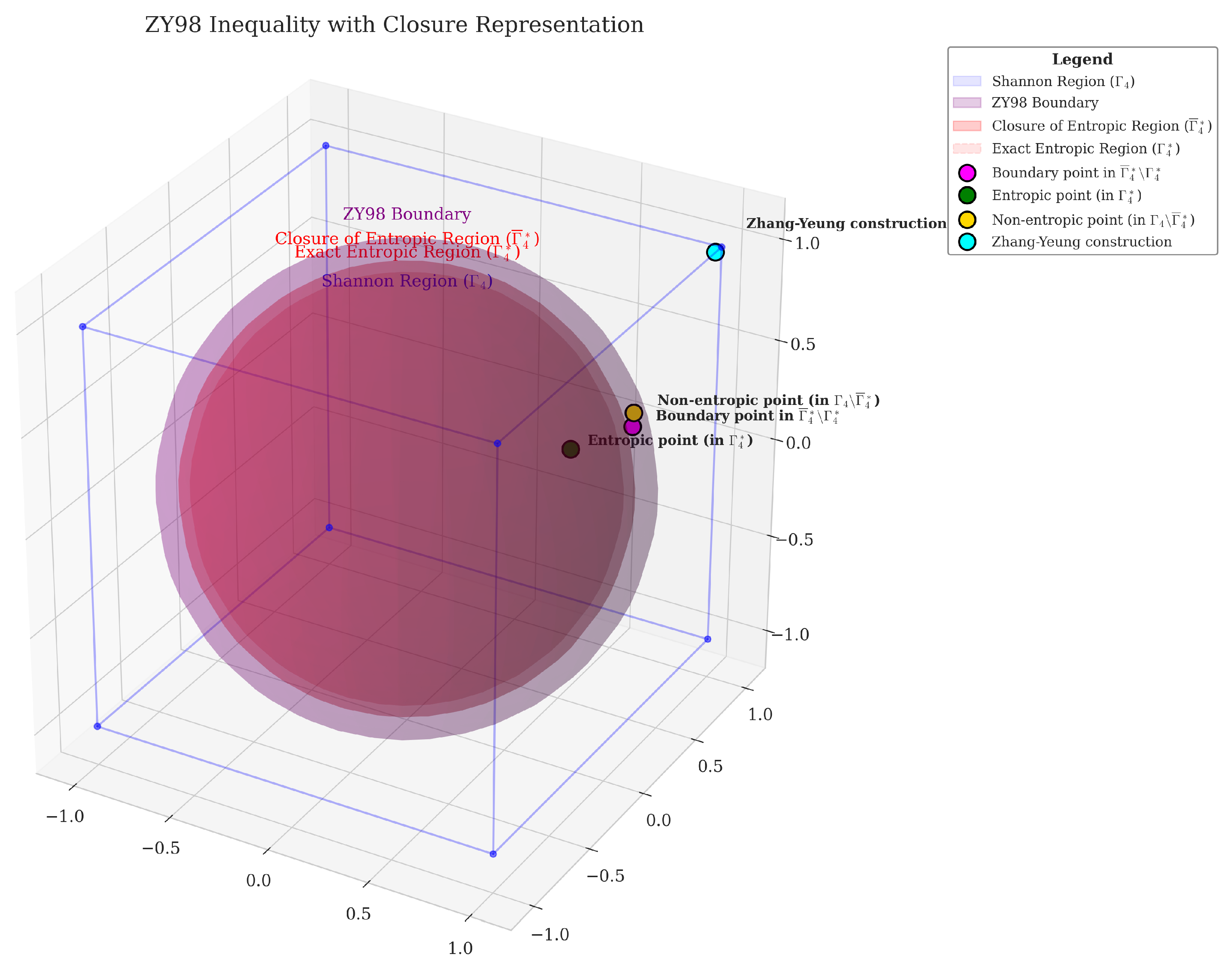

Figure 9.

The ZY98 inequality demonstrates that . Points in can be approached arbitrarily closely but aren’t exactly entropic.

Figure 9.

The ZY98 inequality demonstrates that . Points in can be approached arbitrarily closely but aren’t exactly entropic.

Figure 10.

Comparison of entropy regions for and random variables. For , the closure of the entropic region equals the Shannon region (). For , the ZY98 inequality reveals a strict inclusion (), demonstrating the first unconstrained non-Shannon-type inequality.

Figure 10.

Comparison of entropy regions for and random variables. For , the closure of the entropic region equals the Shannon region (). For , the ZY98 inequality reveals a strict inclusion (), demonstrating the first unconstrained non-Shannon-type inequality.

The ZY98 inequality separates from the gap . The points in this gap cannot be approached arbitrarily closely by entropic points which is unlike for the case of r.d.v.

2.4.2. Remarks – Visualizations “hacks” cube/sphere

Let us recall why our

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 are just conceptual visualizations of the underlying mathematical reality. Indeed, for

r.d.v., the entropy space (

) has a dimension of 15 from:

. The Shannon region (

) is a polyhedral cone in this 15-dimensional space.

Whereas, its facets are 14-dimensional faces which are constructed by replacing a basic inequality with equality and taking its intersection with

[

24].

The ZY98 inequality describes a constraint that reveals: which shows that not all points in the Shannon region () are entropic or, can be approached arbitrarily closely by entropic points.

2.4.3. Polymatroid Properties

In addition to the nonnegativity, the basic inequalities are characterized by the following properties, for :

Table 2.

Polymatroid Properties

Table 2.

Polymatroid Properties

| Property |

Meaning |

|

Nonnegativity |

|

Monotonicity |

|

Submodularity |

All in all, saying that the entropy function satisfies the polymatroid axioms is equivalent way to refer to the basic linear inequalities.

Equipped with these concepts, we can move on to the main object of this text i.e.:

Shannon-type (

3.1) and

non-Shannon-type (

3.2)

inequalities.

2.5. Notation

In this work, we follow the nomenclature developed by Raymond. W. Yeung [

12].

Table 3.

Notation Index.

| Symbol |

Meaning |

|

Entropy Space (in ) |

|

Entropy Vector |

| f |

(Linear) Information Expression (IE) |

|

Linear Combination on IE |

|

or

|

Entropic Region |

|

Almost Entropic Region (closure on ) |

|

Shannon Region |

| ZY98 |

Unconstrained Non-Shannon-type Zhang-Yeung Inequality (2) |

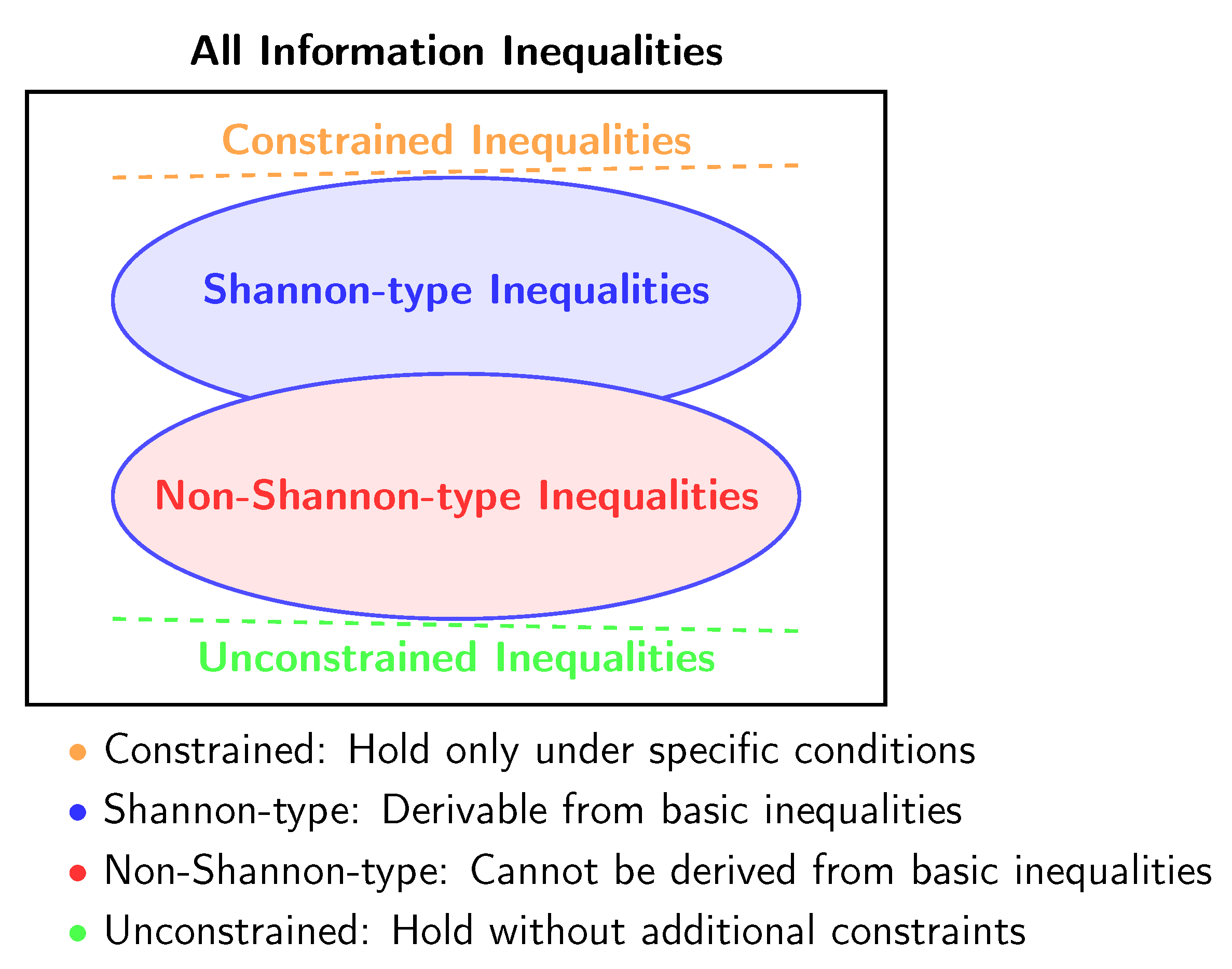

3. Spectrum of Information Inequalities

The main corpus of information inequalities are based on the basic linear inequalities i.e. they are derived from the latter. Additionally, since Shannon’s Mathematical Theory of Communication, they were thought to be the only type of inequalities there were and, they are dubbed Shannon-type inequalities.

Moreover, for this family of inequalities, we can distinguish both constrained and unconstrained declinations.

In addition to Shannon-type inequalities, we have their counterpart which fall into the category of non-Shannon-type inequalities.

These different families of information inequalities can be visualized as follows:

We give an overview

6 of these inequalities in the following sections.

3.1. Shannon-type Inequalities

Shannon-type constitute the most important set of information inequalities. They are implied from the

basic inequalities and the application of

information identities (

B.1) and

chain rules (

B.2).

The

information inequalities derived from the

nonnegativity property or, equally by the

polymatroid axioms (

2.4) are referred to as:

Shannon-type inequalities. To extend on their mathematical properties, conferred by transitivity of the

basic inequalities, we say that they always

hold [

12][p.323].

In other words, for the unconstrained cases with , they are said to hold () because that is the case for any joint-distributions of the involved r.d.v. For, , the Shannon-type inequalities still hold but they don’t describe the complete set of constraints on the entropy vectors.

Constrained and Unconstrained Shannon-type Inequalities

The unconstrained versions can be seen as a special case of the constrained Shannon-type inequalities. That is, unconstrained inequalities is an instance where the constraint subspace encompasses the entire entropy space ().

3.2. Non-Shannon-type Inequalities

The non-Shannon-types are the ones that cannot be reduced to the basic inequalities. Looking at it through regions, we have that if for some n then, the possibility of observing valid inequalities that are not implied by the basic inequalities exists.

We hypothesis and explore in Section (

4), that this “hiatus” could be correlated to the advances or the lack thereof, in computing power and proper software availability. In other words, the time lapse between the theoretically possibility of

non-Shannon-type inequalities (1950s) and their actual discovery [

19] can be linked to the availability of computational tools capable of verifying the large space of possibilities.

Constrained and Unconstrained Non-Shannon-type Inequalities:

The first

constrained non-Shannon-type inequality was reported in: Zhang and Yeung [

25], Matús [

26], they can occur with

d.r.v. As for the

unconstrained non-Shannon-type, this type of inequalities can only exists for

r.d.v., with the Zhang-Yeung (ZY98) inequality [

22] being the first discovered.

3.3. Laws of Information Theory

The

Laws of Information Theory – due to N. Pippenger [

12], express the limits of

information inequalities. They surface by constraints applied to the

entropy function. In other words, the constraints are applied on the

joint-probability distributions described by the underlying random variables.

The question Pippenger raised in 1986 [

12][p.385] was: are there any constraints other than the

polymatroid axioms on the entropy function?

Why does it matter?

As touched upon in the introduction (

1) and following Pippenger’s postulate, the potential existence of inequalities other than the

Shannon-type allows for the possibility of new proofs for

converse coding theorems.

This was positively answered in the 1990s by Zhang and Yeung. They showed in prime the existence of both:

constrained non-Shannon-type inequality [

25] and

unconstrained non-Shannon-type inequality, commonly known as ZY98 inequality [

22].

3.4. Except Lin as Laws 7

A discussion involving

Laws8 would not be complete with at least an exception to the set of rules. As briefly depicted in the introduction (

1), the roots of

entropy are to be found within the fields of

physical chemistry and

physics.

Almost, in collision and collusion with the classical

laws of thermodynamics, we find it appropriate to recall (verbatim) the following

information theory laws due to Lin [

27]:

The first law of information theory: the total amount of data L (the sum of entropy and information, L = S + I ) of an isolated system remains unchanged.

The second law of information theory: Information (I) of an isolated system decreases to a minimum at equilibrium.

The third law of information theory: For a solid structure of perfect symmetry (e.g., a perfect crystal), the information I is zero and the (information theory) entropy (called by me as static entropy for solid state) S is at the maximum.

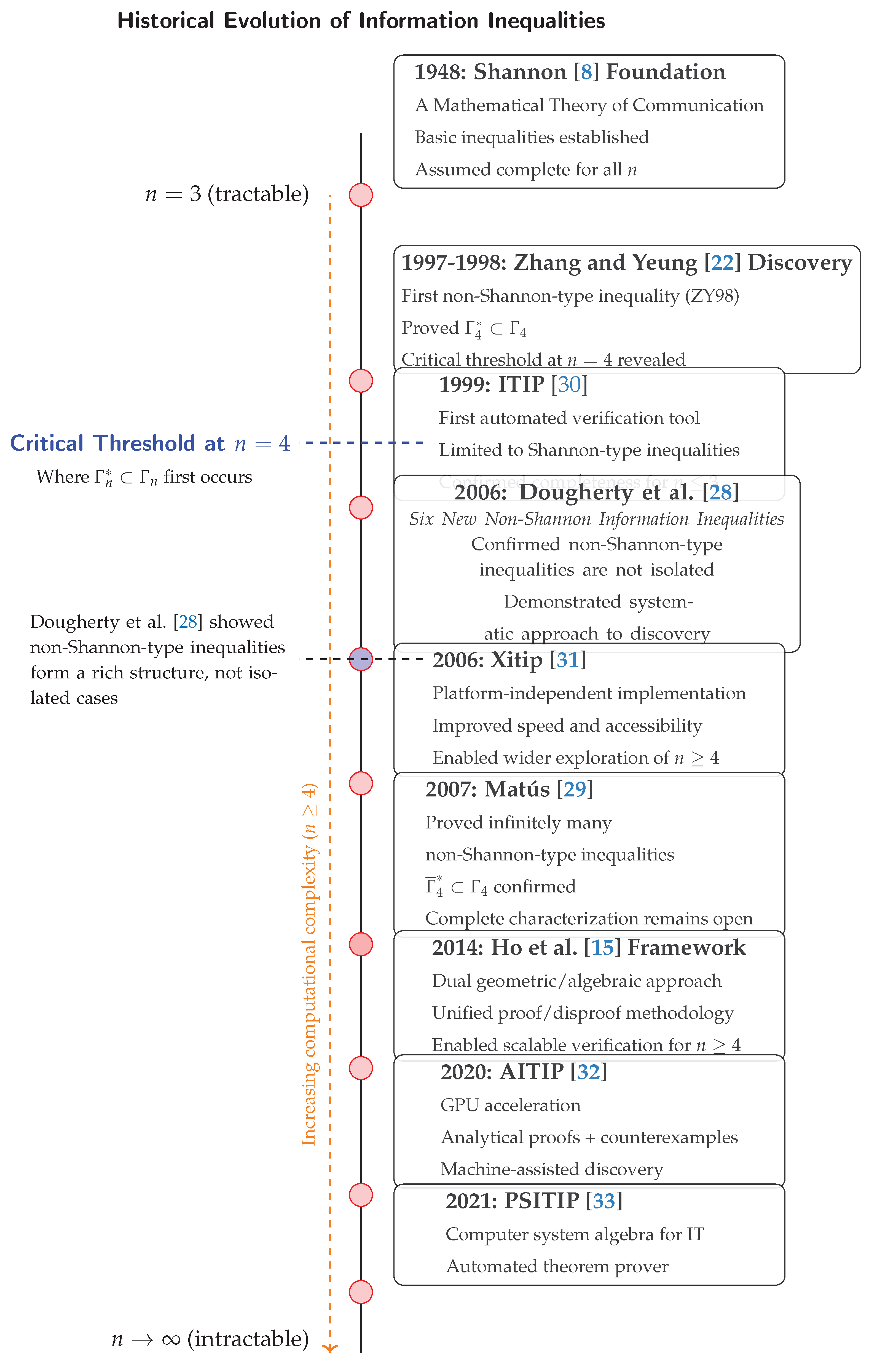

4. Information Inequalities – Timelines

We recalled in the section’s entry (

3), after the seminal work:

A Mathematical Theory of Communication [

8]; the search and research about whether the

basic linear inequalities were the only ones existing was, in a sense, launched.

Furthermore, as outlined in Section (

1.1), this is not a typical

review type-of-work.

In a sense, our lens focuses on the joint evolution of: 1) the increase in computational complexity

9 of inequalities under study and, 2) the improvements in software and, increased use of machine-assisted mathematical research or vice-versa. We are mainly concerned with point 1) but we also draw attention at the second point.

Thus, our reading is linked to the cardinality of d.r.v. at play; more closely, to the dynamics between: the search and verification of discrete random variables inequalities.

We explore these aspects from a historical research development perspective, passing by three layers:

We start by highlighting the inflection point(s) from where the use of “mechanization” becomes required (

4.1).

Then, we present a timeline of the main machine-assisted software for information inequality verification.

Finally, we give a historical/broader overview of these evolutions.

4.1. The Critical Threshold: and

The evaluation of information inequalities is a tale of regions: which takes the following form:

- -

For : , the basic inequalities are complete; the space of entropic vectors is completely characterized by the Shannon region ().

- -

For : (proper subset), but ; all information inequalities are of Shannon-type, yet the space of entropic vectors () is strictly contained within the Shannon region (though its closure equals the Shannon region ()).

- -

For : and ; the basic inequalities are insufficient because there exist non-Shannon-type inequalities that cannot be derived from basic inequalities; the space of entropic vectors () is strictly contained within the Shannon region (), with additional constraints beyond Shannon-type inequalities.

From a Computational Complexity Progression Perspective:

- -

n=2 variables: simple and easy case where basic inequalities completely characterize all the possible information relationships.

- -

n=3 variables: still theoretically manageable, this is why early researchers could have believed that basic inequalities might have been universally sufficient.

- -

n=4 variables: the critical threshold where everything changed. The Zhang-Yeung discovery [

22] showed that: 1)

basic inequalities are no longer complete, 2)

non-Shannon-type inequalities exist, 3) the verification complexity increased drastically.

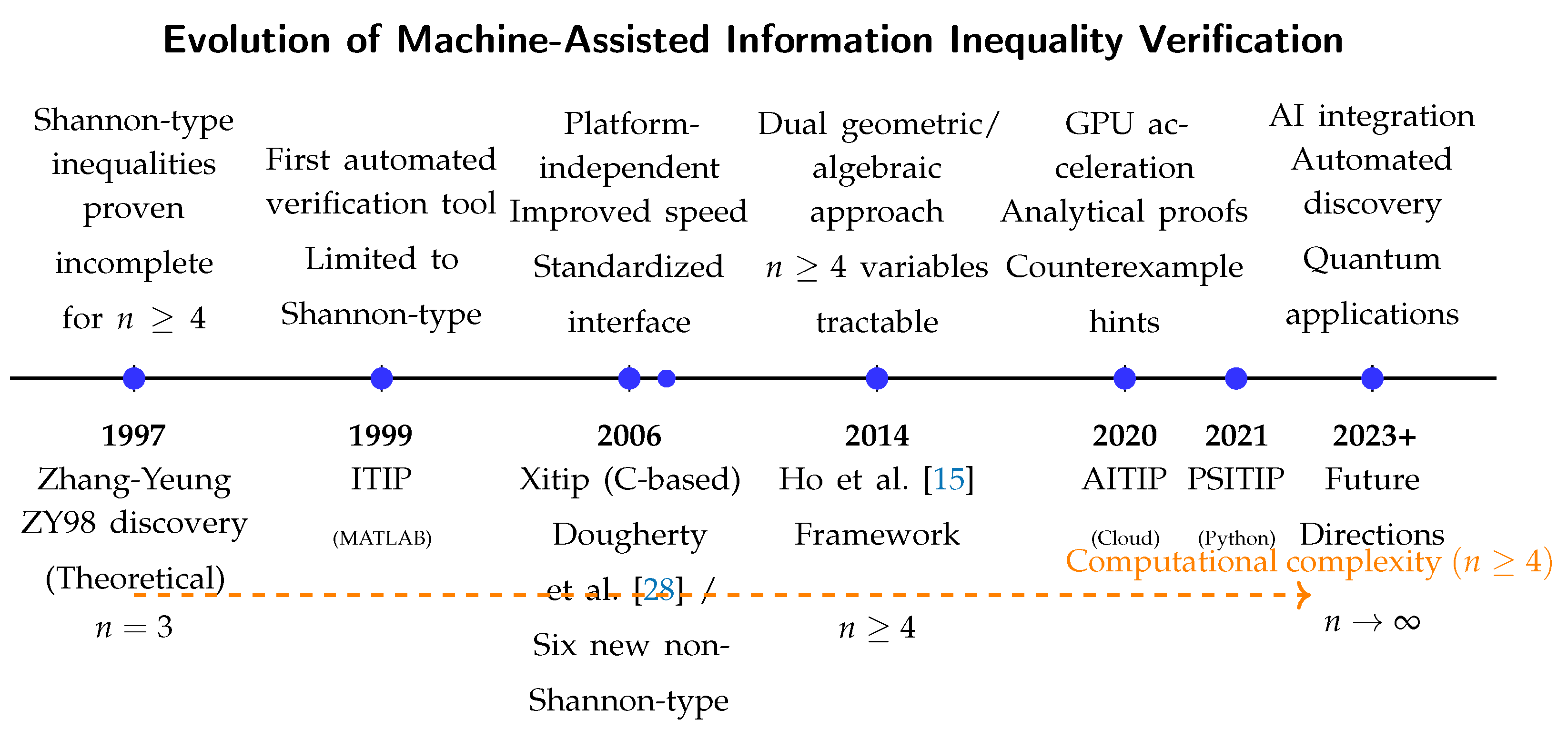

4.2. Machine-Assisted Information Inequality Verification

Hereafter, we present the main research software developments for machine-assisted information inequalities verification.

From Shannon-type to non-Shannon-type inequalities

Overall, we can observe the following:

4.3. Historical Evolution of Information Inequalities

5. Discussion and Conclusion

In this work, we studied the basic linear inequalities of information theory in the entropy space. From Shannon’s initial framework, to the information theory laws, we explored the research topography that lead to the formulation of these “laws”. Beyond the linear inequalities shaping the landscape; it is the depicted regions that govern the story.

Our path led us to uncover that there are multiple relations between the initial research question around the possibility of other inequalities than the basic linear inequalities.

We followed the guiding principle of random variables cardinality at play. We noticed a critical threshold (above three) from where the visualization and verification of the inequalities become significantly more difficult.

At this point, the use of an interactive theorem prover (or other computer assistance), i.e., machine-assisted research, becomes a requirement to navigate the complexity panorama. The question of whether there is or isn’t a causal relation between the increase of compute power and research advancement, or a linear co-evolution, was not our lens. However, we outlined elements pointing in a direction of synergy.

Author Contributions

The author conducted the study and wrote the manuscript. The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The author conducted this research as an independent scholarly project outside the scope of their primary research duties at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IT |

Information Theory |

| IE |

Information Expression |

| d.r.v. |

Discrete Random Variable |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| ITIP |

Information Theoretic Inequality Prover |

| AITIP |

Automated Information Theoretic Inequality Prover |

| PSITIP |

Python Symbolic Information Theoretic Inequality Prover |

Appendix A. Information Expressions

Appendix A.1. Information Identities

An information expression f can take one of the following two forms, either as a linear inequality or linear equality.

Based from source: Yeung [

12][p.323]

Linear inequality form:

where

c is a constant, usually equal to zero.

Linear equality form:

where

c equals to zero.

Appendix B. Information Theory

Appendix B.1. Information Identities

Reproduced from source: Yeung [

12][p.340]

Appendix B.2. Chain Rules

Reproduced from source: Yeung [

12][p.21-22]

Chain Rule – Conditional Entropy

Chain Rule – Mutual Information

Chain Rule – Conditional Mutual Information

References

- Parcalabescu, L.; Trost, N.; Frank, A. What is Multimodality?, 2021, [arXiv:cs.AI/2103.06304].

- Cropper, W.H. Rudolf Clausius and the road to entropy. American Journal of Physics 1986, 54, 1068–1074. [CrossRef]

- Brush, S.G. The Kind of Motion We Call Heat: A History of the Kinetic Theory of Gases in the 19th Century; Vol. 6, Studies in Statistical Mechanics, North-Holland Publishing Company: Amsterdam, 1976. Published in two volumes: Book 1 (Physics and the Atomists) and Book 2 (Statistical Physics and Irreversible Processes).

- von Neumann, J. Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics: New Edition; Princeton University Press: Princeton, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Pippenger, N. The inequalities of quantum information theory. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2003, 49, 773–789. [CrossRef]

- Brillouin, L. Science and Information Theory; Courier Corporation, 2013.

- Rényi, A. On measures of entropy and information. Proc. 4th Berkeley Symp. Math. Stat. Probab. 1, 547-561 (1961)., 1961.

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 623–656. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. The Bell System Technical Journal 1948. 27. Includes seminal papers such as C. E. Shannon’s "A Mathematical Theory of Communication" (Parts I and II in Issues 3 and 4). Available at the Internet Archive.

- Hartnett, K. With Category Theory, Mathematics Escapes From Equality. Quanta Magazine 2019.

- Yeung, R.W. Facets of entropy. Commun. Inf. Syst. 2015, 15, 87–117. [CrossRef]

- Yeung, R.W. Information theory and network coding, 2008 ed.; Information Technology: Transmission, Processing and Storage, Springer: New York, NY, 2008.

- Guo, L.; Yeung, R.W.; Gao, X.S. Proving Information Inequalities and Identities With Symbolic Computation. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theor. 2023, 69, 4799–4811. [CrossRef]

- Yeung, R.W. A framework for linear information inequalities. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1997, 43, 1924–1934. [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.; Ling, L.; Tan, C.W.; Yeung, R.W. Proving and Disproving Information Inequalities: Theory and Scalable Algorithms. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2020, 66, 5522–5536. [CrossRef]

- Fujishige, S. Polymatroidal dependence structure of a set of random variables. Information and Control 1978, 39, 55–72. [CrossRef]

- Csirmaz, L. Around entropy inequalities. https://seafile.lirmm.fr/f/1a837bfc0063408f934b/, 12 Oct 2022. Accessed: 2025-11-23.

- Suciu, D. Applications of Information Inequalities to Database Theory Problems, 2024, [arXiv:cs.DB/2304.11996].

- Yeung, R.W. A framework for information inequalities. Proceedings of IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory 1997, pp. 268–.

- Chen, Q.; Yeung, R.W. Characterizing the entropy function region via extreme rays. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Information Theory Workshop, Lausanne, Switzerland, September 3-7, 2012. IEEE, 2012, pp. 272–276. [CrossRef]

- Yeung, R.W.; Li, C.T. Machine-Proving of Entropy Inequalities. IEEE BITS the Information Theory Magazine 2021, 1, 12–22. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yeung, R. On characterization of entropy function via information inequalities. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1998, 44, 1440–1452. [CrossRef]

- Chaves, R.; Luft, L.; Gross, D. Causal structures from entropic information: geometry and novel scenarios. New Journal of Physics 2014, 16, 043001. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, H.; Thakor, S. On Characterization of Entropic Vectors at the Boundary of Almost Entropic Cones. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Information Theory Workshop, ITW 2019, Visby, Sweden, August 25-28, 2019. IEEE, 2019, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yeung, R. A non-Shannon-type conditional inequality of information quantities. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1997, 43, 1982–1986. [CrossRef]

- Matús, F. Piecewise linear conditional information inequality. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 2006, 52, 236–238. [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.K. Gibbs Paradox and the Concepts of Information, Symmetry, Similarity and Their Relationship. Entropy 2008, 10, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, R.; Freiling, C.F.; Zeger, K. Six New Non-Shannon Information Inequalities. In Proceedings of the Proceedings 2006 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, ISIT 2006, The Westin Seattle, Seattle, Washington, USA, July 9-14, 2006. IEEE, 2006, pp. 233–236. [CrossRef]

- Matús, F. Infinitely Many Information Inequalities. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, ISIT 2007, Nice, France, June 24-29, 2007. IEEE, 2007, pp. 41–44. [CrossRef]

- Yeung, R.W.; Yan, Y.O. ITIP—Information Theoretic Inequality Prover. http://user-www.ie.cuhk.edu.hk/~ITIP/, 1996.

- Pulikkoonattu, R.; Perron, E.; Diggavi, S. Xitip Information Theoretic Inequalities Prover. http://xitip.epfl.ch, 2008.

- Ho, S.W.; Ling, L.; Tan, C.W.; Yeung, R.W. AITIP. https://aitip.org, 2020.

- Li, C.T. An Automated Theorem Proving Framework for Information-Theoretic Results 2021. pp. 2750–2755. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

Inscribed in a closer temporal timeframe: Pippenger [ 5]. |

| 2 |

Let’s us recall the prior foundational work of R. V. R. Hartley. |

| 3 |

Incidentally, the canonical symbol defining equality (=) is depicted using two superposed segments; the nature of “equality” is questioned: [ 10] |

| 4 |

In this case: ITIP(Information Theoretic Inequality Prover) but the approach is generally applicable. |

| 5 |

We recall ( 2.4.2) and develop on why both ( 7) & ( 8) visualizations are a mere approximation of the mathematical reality they are trying to describe. |

| 6 |

For the interested reader in a thorough mathematical description Yeung [ 12] can be consulted. |

| 7 |

This is a wink to a Python exception handling statement / design pattern. |

| 8 |

That is, in the context of Science. |

| 9 |

This is not in the sense of Computational Complexity Theory (CCT) as a field, though some close-ups could be made. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).