1. Introduction

The history of the Afro-descendant community in Latin America is profoundly shaped by the transatlantic slave trade, considered the largest forced migration in history [

1]. More than 500 years ago, Afro-descendants arrived in the region under adverse conditions driven by racist, economic, and religious motives. Many slaves were brought to serve as laborers in plantations, mines, domestic service, and to a lesser extent as warriors. The strugglerightsedom, which began with failed escape attempts, confrontations, and demands for rights, only gained results in the early nineteenth century. However, following the progressive abolition of slavery, Afro-descendant settlement groups have continued to be seen and treated as a threat to social security, leading to exclusion and racial violence.

Over the last 250 years, these groups have rebuilt their identity and sense of belonging in new territories, but they continue to face poverty, social and economic hardship, and limited access to health care. Geographic isolation, while fostering the preservation of identity, culture, and social cohesion, has also led to endogamy, which predisposes these populations to the expression of genetic, cardiovascular, and mental diseases [

2].

Various international studies have shown that a history of violence, trauma, deprivation, racism, and post-migration difficulties is associated with high rates of mental disorders—mainly post-traumatic stress disorder and depression—among Afro-descendant and African migrant populations in Europe, Asia, and the Americas. Social and economic determinants make a significant contribution to the development of problems such as depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders. Additionally, exposure to natural disasters, geographic isolation, illiteracy, medical comorbidities, and low income markedly affect the quality of life of these communities.[

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

Mental health problems in migrants and refugees are reflected in difficulties coping with stress, working productively, and contributing to society due to various barriers. Likewise, violent traumas and severe deprivation can explain a heightened risk of mental illnesses. [

2]. A study conducted with 500 low-income African Americans and Latinos highlights the harmful consequences of cumulative stress and trauma on mental health [

8]. Unresolved traumas and emotional patterns are passed down through generations, influencing current family dynamics [

9]. It is well known how an adverse environment can provoke genetic polymorphisms under conditions of social stress and economic hardship, emphasizing the importance of the interaction between environmental and genetic factors in the manifestation of mental disorders [

10].

In Ecuador, most Afro-descendant settlements that arrived as slaves are in rural riverside areas in the north of the country, where vulnerability to disasters and social exclusion is especially pronounced. However, despite the magnitude and specificity of these challenges, there is a notable lack of published studies in Ecuador that systematically address the mental health of Afro-descendant communities. The scarce existing literature is focused on demographic or cultural aspects, neglecting a thorough analysis of psychosocial factors as determinants in the prevalence of mental disorders within these groups [

11,

12].

The lack of local research hampers the understanding of an empirically observed problem and consequently limits the design of interventions and the development of policies aimed at optimally and pertinently addressing this situation. Therefore, it is essential to obtain scientific information regarding the interaction of social and economic factors on the mental health of these groups [

13,

14,

15].

The present study aims to identify the social and economic factors associated with an increased risk of mental disorders in Afro-descendant communities, providing relevant evidence to guide future preventive intervention strategies adapted to the specific reality [

16,

17].

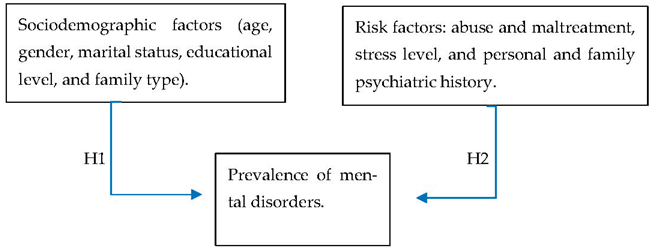

Research Hypothesis 1 (H1): There is a significant association between sociodemographic factors (age, gender, marital status, educational level, and family type) and the prevalence of mental disorders.

Research Hypothesis 2 (H2): Risk factors (abuse and maltreatment, stress levels, and personal and family psychiatric history) are associated with a higher prevalence of mental disorders.

Research question: (RQ1): What factors are associated with a higher presence of mental disorders among the Afro-descendant population of the Chota River basin?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

An analytical, quantitative, cross-sectional study was conducted in communities of the Chota River basin, using a sample of 557 Afro-descendant individuals. The sample size was determined to ensure representativeness by age and gender, following demographic criteria of the local population.

2.2. Sampling Design

The sample was selected from a population of 5,118 inhabitants using probabilistic cluster sampling in the communities of Caldera, Piquiucho, Carpuela, San Vicente de Pusir, and Pusir Grande.

2.3. Procedure

Prior to data collection, participants were informed about the objectives and scope of the study, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant. Data collection was carried out by a team of researchers and trained students who administered the instrument and conducted individual interviews in confidential settings within each community, until the planned sample size was reached.

2.4. Instruments

The assessment of mental disorders was conducted using the GMHAT-PC (Global Mental Health Assessment Tool – Primary Care), an instrument that identifies a wide range of mental health problems and can be used by healthcare professionals to detect and manage mental disorders in primary care among the general population. Validation studies have reported a sensitivity of 0.79 (95% CI: 0.73–0.85) and a specificity of 0.94 (95% CI: 0.83–1) [

18,

19,

20,

21]. GMHAT is used for the systematic assessment of mental symptoms and disorders, allowing for the identification of conditions such as depression, anxiety, and psychotic disorders, among others. It has been used in various settings, including inpatient services and community-based contexts [

22,

23]. In addition, sociodemographic variables, history of abuse, stress level, and personal and family psychiatric history were recorded.

To assess lifestyle-related factors, questions from Phase 1 of the World Health Organization (WHO) STEPS instrument were incorporated. This tool is designed for the epidemiological surveillance of behavioral risk factors associated with noncommunicable chronic diseases. The initial stage (STEPS I) gathers information on sociodemographic characteristics, tobacco and alcohol consumption, nutritional status, and physical activity. The STEPS questionnaire is widely used in population-based studies and has been validated across multiple settings, facilitating the identification of risk behaviors that impact the mental and physical health of populations [

24].

Finally, to assess participants’ level of physical activity, the short version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) was used. This instrument is designed to measure physical activity in adults aged 18 to 69 years. It covers different domains of physical activity, including occupational activity, transportation, leisure-time activity, and household tasks, and allows individuals to be categorized by activity level (low, moderate, and high) based on Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET) scores [

25].

2.5. Data Analysis

Data was processed and analyzed using Jamovi statistical software (version 2.6). A descriptive analysis of frequencies and percentages was performed for sociodemographic and risk factor variables. Subsequently, the prevalences of the identified mental disorders were estimated, and associations between independent variables (age, gender, educational level, history of violence, social support, dietary habits, physical activity) and mental health outcomes were examined using logistic regression models. The significance level was set at 0.05.

3. Results

This study provided a description of sociodemographic factors and key determinants of mental health in a population located in northern Ecuador. It focused on describing data such as gender, economic status, marital status, educational level, age, and family structure, as well as risk factors including history of abuse and maltreatment, stress level, and personal and family history of mental disorders.

3.1. Sociodemographic Data

The sociodemographic characterization of the sample, consisting of 557 participants, revealed a population profile marked by social and economic vulnerability, shaping a context of significant psychosocial risk.

3.1.1. Sex Distribution

Most participants were women, as shown in

Table 1 (61.2%). This pattern is consistent with the higher participation of women in community-based studies and aligns with global trends indicating a greater burden of affective and anxiety disorders among females—often attributed to social role demands, dual labor responsibilities, and differential exposure to violence and discrimination.

3.1.2. Age-Group Distribution

The age distribution showed a balanced representation of young adults, middle-aged adults, and older adults, reflecting the demographic heterogeneity of rural Afro-descendant communities. This pattern allowed for the identification of different expressions of psychological distress across the life course: socioeconomic stress and unemployment among younger adults, family and work overload in middle-aged adults, and isolation or bereavement among older adults.

3.1.3. Marital Status

Although most participants were married, a significant proportion of individuals without a stable partner (single, separated, or widowed) was observed, suggesting a possible fragility in affective support networks. The literature has documented that the absence of protective marital or family bonds increases vulnerability to depressive and anxiety symptoms, particularly in environments where social cohesion has been eroded by migration or poverty.

3.1.4. Education

Regarding education level, basic education predominated, with a minority reaching higher education. This low schooling reflects historical limitations in access to formal education, characteristic of rural Afro-descendant communities, constituting a structural determinant of mental health, as it is associated with lower health literacy, precarious jobs, and limited opportunities.

3.1.5. Economic Income

Most of the population was below the basic wage, confirming the presence of structural poverty. This aspect, widely recognized as one of the main social determinants of mental health, is linked to high levels of chronic stress, insecurity, and exclusion, creating an environment that perpetuates various mental disorders.

3.1.6. Family Type

The most predominant grouping was the nuclear family, although there was a notable presence of single-parent households, especially headed by women. This family structure implies a greater economic and emotional burden, which can be associated with increased risk of depression and anxiety symptoms in both caregivers and dependents. Extended families, while providing some social support, can generate intergenerational tensions and domestic overload in contexts of scarcity.

Table 2.

Presence of Risk Factors.

Table 2.

Presence of Risk Factors.

| Variable |

Frecuency |

Percentage of total |

| Abuse and maltreatment |

|

|

| Physical, sexual, and psychological |

7 |

1.3% |

| Physical |

36 |

6.5% |

| Psychological |

114 |

20.5% |

| Sexual |

3 |

0.5% |

| None |

397 |

71.3% |

| Stress level |

|

|

| Mild stress |

211 |

37.9% |

| Moderate stress |

93 |

16.7% |

| Severe stress |

39 |

7.0% |

| No stress |

214 |

38.4% |

| Personal psychiatric history |

|

|

| Yes |

127 |

22.8% |

| No |

430 |

77.2% |

| Family psychiatric history |

|

|

| Yes |

71 |

12.7% |

| No |

386 |

87.3% |

| Total |

557 |

100% |

3.2. Risk Factors

The analysis of psychosocial risk factors and psychiatric history in the studied population revealed a complex pattern of emotional vulnerability and cumulative exposure to adverse experiences, situated within a historical context of structural marginalization.

3.2.1. Abuse and Maltreatment

Although most participants did not report experiencing abuse, a considerable proportion reported a history of physical or psychological violence, with the latter being the most prevalent form (20.5%). The coexistence of physical and psychological maltreatment in certain cases suggests a multifactorial pattern of violence, which may potentially impact emotional regulation, self-esteem, and coping capacities. The presence, albeit low, of sexual abuse constitutes a clinically significant indicator, given its strong association with major depressive disorders, post-traumatic stress, and self-injurious behaviors in vulnerable populations.

3.2.2. Stress Level

The distribution of stress levels showed that nearly half of the participants experienced some degree of perceived stress, with a non-negligible group experiencing severe stress. The predominance of mild and moderate stress could reflect mechanisms of community resilience and cultural adaptation to adversity; however, the presence of severe stress in a notable proportion (7%) suggests that traditional coping strategies may be overwhelmed, thereby facilitating the emergence of anxiety, depressiveness, and somatic symptoms. These findings reinforce the hypothesis that chronic stress is one of the main immediate determinants of mental disorders observed in the Afro-descendant population of Chota.

3.2.3. Personal and Family Psychiatric History

The proportion of participants with a personal and family history of mental health disorders confirmed the presence of psychobiological vulnerability in a significant segment of the population. Personal history reflected previous exposure to depressive, anxious, or psychotic episodes. The existence of family history suggests a hereditary or familial component which, in combination with adverse environmental factors, may potentiate the clinical expression of mental disorders.

Table 3.

Prevalences of the main mental disorder diagnoses detected by the GMHAT/PC (Global Mental Health Assessment Tool Primary Care.

Table 3.

Prevalences of the main mental disorder diagnoses detected by the GMHAT/PC (Global Mental Health Assessment Tool Primary Care.

| Mental Disorder |

Frequencies |

% of Total |

| Total with mental illness |

338 |

60.7% |

| Total without mental illness |

219 |

39.3 |

| Major depressive disorder |

87 |

15.6% |

| Anxiety disorder |

57 |

10.2% |

| Psychosis with depression |

46 |

8.3% |

| Organic mental disorder |

34 |

6.1% |

| Psychotic disorder |

20 |

3.6% |

| Personality disorder |

19 |

3.4% |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder |

12 |

2.2% |

| Eating disorder |

16 |

2.9% |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder |

11 |

2.0% |

| Phobia |

9 |

1.6% |

3.3. Mental Disorder Prevalence

Screening through the Global Mental Health Assessment Tool (GMHAT/PC) revealed a high psychiatric morbidity burden in the Afro-descendant population of the Chota River basin, with a predominance of affective and anxiety disorders, followed by psychotic disorders and organic-origin disorders. This epidemiological profile reflects a mixed pattern of psychological suffering in which emotional, social, and neurobiological factors converge.

Major depressive disorder was the most frequent diagnosis (15.6%), constituting the principal mental health problem in the sample. Anxiety disorder ranked second, reinforcing the hypothesis of a high prevalence of common mental disorders (CMDs) in contexts characterized by sustained stress and economic precariousness. The coexistence of depression and anxiety suggests the presence of affective-anxious comorbidity, common in community settings with limited access to treatment.

The detection of psychosis with depressive symptoms and primary psychotic disorders suggests a significant subgroup of cases with severe mental functioning impairment. Although less prevalent, other mental health conditions such as personality disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, phobias, and eating disorders were identified, broadening the observed clinical spectrum and reflecting the diversity of psychopathological expressions in the community. The presence of post-traumatic stress, although in a smaller proportion (2%), is clinically relevant as it indicates exposure to direct traumatic events such as domestic violence or discrimination.

Bivariate analysis (

Table 4) revealed significant associations between certain sociodemographic factors and risk factors with the presence of mental disorders in the population. Female sex showed a higher prevalence of mental illness (40.6%) compared to males (20.1%), a difference that was statistically significant (p = 0.006). No significant differences were found in age groups (p = 0.3), although older adults exhibited a slightly higher proportion of cases (21.4%), suggesting a possible increase in mental symptoms related to social isolation, chronic diseases, and loss of family support. Marital status did not reach statistical significance in relation to mental disorders (p = 0.073), but divorced individuals (76.7%) and widowed individuals (71.2%) showed the highest prevalences, which may reflect the impact of the rupture or loss of affective bonds on mental health. Singles and separated individuals also exhibited relatively high percentages, reinforcing the influence of social and emotional support on psychological stability. Educational level showed a non-significant association (p = 0.094), but it was observed that people without schooling or with primary education had a higher frequency of mental disorders (62.2% and 65.5%, respectively) compared to those who reached higher education (48.9%). This pattern suggests an indirect relationship between education and coping resources for stress or socioeconomic adversities. Regarding economic income, a significant association was found (p = 0.014), with individuals earning less than the minimum wage presenting a prevalence of mental disorders of 62.6%, compared to 47.1% among those who earned more. Economic precariousness thus appears as an important determinant of psychological vulnerability. Stress level showed a strongly significant relationship (p < 0.001); as the stress level increased, the prevalence of mental disorders also increased: from 44.9% among those who reported no stress to 94.9% among those with severe stress. This gradient highlights the role of stress as a critical risk factor in the genesis and maintenance of mental disorders. Finally, the variable abuse and maltreatment showed the strongest association (p < 0.001). Individuals reporting experiences of physical, sexual, or psychological maltreatment exhibited mental illness rates between 66.7% and 100%, underscoring the direct relationship between traumatic experiences and the emergence of psychiatric symptoms.

In

Table 5, a multivariate analysis was conducted among sociodemographic factors, gender, and main psychiatric diagnoses such as depression, anxiety, and psychosis; the results showed relevant interactions between sociodemographic variables, particularly gender and educational level, with the prevalence of the main identified mental disorders. In general, women present a higher proportion of psychiatric diagnoses compared to men. For major depressive disorder, a statistically significant association was found between lower educational level and higher prevalence (p=0.041), especially among women with primary education or less. Regarding psychosis, a significant association was also found with education level (p=0.046), with the most severe cases concentrated among people with lower educational attainment, especially women. In the case of anxiety disorders, no significant differences were observed according to educational level (p > 0.05), which may indicate that this type of disorder is influenced by transversal factors present throughout the population, such as social stress, economic insecurity, and exposure to structural violence, rather than differences in educational capital. Regarding income level, a significant association was observed with anxiety (p < 0.01), being more prevalent among women with incomes below the minimum wage. This result highlights the interaction between economic inequality and gender in the genesis of psychological distress, where women in poverty conditions present greater emotional burden and less access to formal or informal support, reinforcing a cycle of vulnerability. Finally, the analysis by marital status revealed a trend, though not statistically significant, of higher rates of depression and psychosis in women who were separated, divorced, or widowed.

Table 6 presents the results of the association analysis between perceived stress level, experiences of abuse and maltreatment, and the presence of the three most prevalent mental disorders (depression, anxiety, and psychosis). The Mann-Whitney U test was applied to evaluate these associations, showing that stress was significantly associated with all evaluated mental disorders. Abuse and maltreatment were strongly associated with depression and psychosis, but not with anxiety. The effects of stress and trauma appear to act differently: stress is related to more reactive conditions (such as anxiety), while maltreatment is linked to deeper or structural conditions like depression and psychosis. These findings support a cumulative vulnerability model, where prolonged exposure to stress and violence causes emotional and physiological wear that increases the likelihood of developing severe mental disorders, especially in populations with limited economic resources and social support networks.

4. Discussion

The findings on mental disorders reveal a concerning reality in these populations and simultaneously show relevant associations of some sociodemographic factors such as history of abuse and maltreatment, stress level, gender, and economic income. The overall prevalence of mental disorders at 60.7% found in this African American population significantly exceeds figures reported in general population studies. The U.S. survey conducted from 2001 to 2003, which considered racial differences between Whites and Blacks, found that African Americans have equal or higher likelihoods of presenting mental disorders. Jude Mary C, in a recent meta-analysis including 1.3 million Afro-descendant individuals, found a depression prevalence of 20.2% (95% CI: 18.7%–21.7%). Meanwhile, U.S. studies report that African American adults are 20% more likely to experience serious mental health problems compared to the White population [

26]. A systematic review mentioned in the World Mental Health Report states that socially marginalized groups, including ethnic minorities, have higher rates of mental disorders. However, none of these findings surpass the figures found in the present study, which is likely due to the tool used that allows detecting more mental disorders. This finding is possibly associated with specific social determinants such as discrimination, socioeconomic marginalization, and limited access to mental health services [

27,

28]. Structural racism, which causes various social problems, along with other social determinants, leads to chronic stress and trauma [

29,

30,

31].

The data also confirm the global epidemiological pattern, where women more frequently present mental disorders. The explanation lies in greater biological and hormonal vulnerability, specific psychosocial factors, cultural models, low educational level, social class, unemployment, and lack of social support affecting African American women. This includes traditional gender roles, family care overload, and greater exposure to gender-based violence, as suggested by studies from Galbis and Bacigalupe, as well as the abuse and maltreatment data in this study, resulting in compounded traumatic factors [

14,

32].

Most of the population was found to have incomes below the minimum wage, including unemployment, and these individuals have the highest prevalence of mental disorders. This finding is consistent with the evidence found in Gili's study, which links poverty and mental health as a result of moderate to severe psychological distress. [

29,

33]. This association is particularly relevant in African American communities, where it has been described that populations living below the poverty line are more than twice as likely to report severe stress, in addition to other conditions that these communities have historically faced. [

27].

Regarding the spectrum of mental disorders, there was a predominance of the following disorders: major depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, and psychotic disorders. According to the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (SAMHSA), 19.7% of Black and African American adults have experienced a mental health condition in the past year [

34]. In Greene et al.'s review study, 22-point prevalence studies in 12 North African countries determined that the prevalence of major depressive disorder ranged from 2.0% to 33.2%, with the highest prevalence in South Africa, the region of origin for Ecuadorian Afro-descendants. In the same study, point prevalence for anxiety disorders ranged from 0.9% to 36.5% across 12 of the 36 reviewed studies [

35]. The prevalence findings for depression and anxiety in the present study are consistent with this review; however, there are discrepancies between the analyzed studies regarding psychosis data, which show point prevalences ranging from 0.19% to 9.3% in only two studies conducted in different African cities, with lifetime prevalences reaching over 39%. None of the studies included in Greene et al.'s review used the GMHAT/PC tool; nevertheless, despite diagnostic heterogeneity, they agree on the DSM criteria and findings [

35]. The significant presence of psychosis, alone or associated with affective disorders, requires special attention, as it may reflect both genetic vulnerabilities and the impact of chronic psychosocial stress [

36]. The presence of major depressive disorder, psychosis, and anxiety, in that order, showed a significant correlation with higher stress levels and the presence of abuse and maltreatment more than with other sociodemographic variables, except for the variable of low income for anxiety disorder and low educational attainment, where depression and psychosis approached statistical significance.

The data showed a highly significant association between stress level and the presence of mental disorders (p<0.001). The progressive increase in prevalence according to stress level, reaching up to 94.9% in cases of severe stress, highlights the central role of this factor in psychiatric pathophysiology. Chronic stress has been associated with dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, neuroinflammation, and neuroplastic alterations that favor the emergence of depressive and anxious symptoms [

37].

The results of the present study regarding abuse and maltreatment as risk factors for mental disorders revealed a pattern of high prevalence with depressive and anxious symptoms, showing a significant association (p<0.001). These findings are consistent with those reported by Grayson et al., where racial and structural trauma generates lasting effects on the mental health of the African American community. Both physical and psychological abuse act as chronic stressors that trigger mental health disorders [

38]. The results of Ricks and Horan [

39], found that exposure to childhood sexual abuse (40.6%) and intimate partner violence (44.9% physical, 63% emotional, 40.6% sexual) are extremely frequent and strongly associated with depressive symptoms, anxiety, and poorer quality of life, which was evidenced in the population of the Chota Valley

5. Conclusions

The sociodemographic factors revealed a female predominance in the sample and a high proportion of young and older adults, with low educational levels and high poverty rates, as most participants reported incomes below the minimum wage. This economic precariousness was significantly associated with a higher prevalence of mental disorders.

The present study confirms a high burden of psychiatric morbidity in the Afro-descendant communities of the Chota River basin, showing a significantly higher prevalence of mental disorders than the national and regional averages reported for Latin America.

The most frequent mental disorders were major depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, and psychosis with depressive symptoms, all with a female predominance.

A central role of stress and experiences of abuse/maltreatment in the genesis of mental disorders was evidenced, with a directly proportional relationship observed between the intensity of stress and the presence of mental illness (anxiety).

Physical and psychological abuse showed a 100% association with the presence of mental disorders, confirming the relevance of interpersonal trauma as a psychiatric trigger, especially depression.

Author Contributions

Y.A. and R.A. contributed equally to the conceptualization, design, data collection, analysis, and writing of this manuscript. Both authors have read and approved the final version.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The study was supported by institutional resources from the Universidad Técnica del Norte, Ibarra, Ecuador.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received written approval from the Directorate of Research of the Universidad Técnica del Norte, Ibarra, Ecuador (RES. Nro. UTN-CI-2024-252-R, approval date: 16 Oct 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Participants were informed about the purpose, voluntary nature, and confidentiality of the research prior to participation, and all provided with written consent in accordance with institutional requirements.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data is not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions established by the Universidad Técnica del Norte, as they contain information that could compromise the confidentiality of study participants.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the Universidad Técnica del Norte for its institutional and logistical support, as well as to the participating communities of the Chota River basin for their collaboration throughout the research process. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used several artificial intelligence and digital tools to support the research workflow. Specifically, ChatGPT (GPT-5, OpenAI, 2025) was employed for language editing and manuscript style refinement; Perplexity AI was used to access tutorials and guidance for statistical analysis using Jamovi software; and Consensus was utilized to organize and synthesize bibliographic search. The authors have reviewed and edited all outputs from these tools and take full responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

GMHAT/PC

Global Mental Health Assessment Tool – Primary Care Version |

IPAQ

International Physical Activity Questionnaire |

WHO

World Health Organization |

STEPS

WHO STEPwise Approach to Noncommunicable Disease Risk Factor Surveillance

UTN

Universidad Técnica del Norte

CI

Confidence Interval

OR

Odds Ratio

SDH

Social Determinants of Health

|

References

- Fortes-Lima, C.; Gessain, A.; Ruiz-Linares, A.; Bortolini, M.; Migot-Nabias, F.; Bellis, G.; et al. Genome-wide Ancestry and Demographic History of African-Descendant Maroon Communities from French Guiana and Suriname. American journal of human genetics 2017, 101, 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelo, J.N.; Gastón, M. Educación superior y pueblos indígenas y afrodescendientes en América Latina. Normas, políticas y prácticas. Perfiles Educativos 2014, 36, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, W.; Ncube, F.; Shaaban, K.; Dafallah, A. Prevalence, predictors, and economic burden of mental health disorders among asylum seekers, refugees and migrants from African countries: A scoping review. PLOS ONE 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P.B.; Renzaho, A.; Mwanri, L.; Miller, I.; Wardle, J.; Gatwiri, K.; et al. The prevalence of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder among African migrants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research 2022, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harriman, N.; Williams, D.; Morgan, J.; Sewpaul, R.; Manyaapelo, T.; Sifunda, S.; et al. Racial disparities in psychological distress in post-apartheid South Africa: results from the SANHANES-1 survey. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 2021, 57, 843–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailam, S.; Sudershan, A.; Sheetal Younis, M.; Arora, M.; Kumar, H.; et al. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among the adult population in a rural community of Jammu, India: a cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemu, W.G.; Due, C.; Muir-Cochrane, E.; Mwanri, L.; Azale, T.; Ziersch, A. Quality of life among people living with mental illness and predictors in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Quality of Life Research 2023, 33, 1191–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, H.F.; Wyatt, G.E.; Ullman, J.B.; Loeb, T.B.; Chin, D.; Prause, N.; et al. Cumulative burden of lifetime adversities: Trauma and mental health in low-SES African Americans and Latino/as. Psychol Trauma 2015, 7, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harden, B.A.-O.; Martoccio, T.L.; Lee, K.A.; Jaramillo, M. Intergenerational trauma, parenting, and child behavior among African American families living in poverty. Psychological trauma 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, K.; Gravlee, C.C.; McCarty, C.; Mitchell, M.M.; Mulligan, C.J. Stressful social environment and financial strain drive depressive symptoms, and reveal the effects of a FKBP5 variant and male sex, in African Americans living in Tallahassee. Am J Phys Anthropol 2021, 176, 572–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pueblo, D.d. El Pueblo Afrodescendiente en el Ecuador. Informe Temático. 2012.

- Capella, M.; Jadhav, S.; Moncrieff, J. History, violence and collective memory: Implications for mental health in Ecuador. Transcultural Psychiatry 2020, 57, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayiku, R.N.B.; Jahan, Y.; Adjei-Banuah, N.Y.; Antwi, E.; Awini, E.; Ohene, S.; et al. Incidence, prevalence and risk factors for comorbid mental illness among people with hypertension and type 2 diabetes in West Africa: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacigalupe, A.; Cabezas, A.; Bueno, M.B.; Martín, U. El género como determinante de la salud mental y su medicalización. Informe SESPAS 2020. Gaceta Sanitaria 2020, 34, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edison, C.; Benjamín, P. Epidemiología de la morbilidad psiquiátrica en el Ecuador. Gaceta Médica Espirituana 2021, 23, 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Paz, C.; Mascialino, G.; Adana-Díaz, L.; Rodríguez-Lorenzana, A.; Simbaña-Rivera, K.; Gómez-Barreno, L.; et al. Behavioral and sociodemographic predictors of anxiety and depression in patients under epidemiological surveillance for COVID-19 in Ecuador. PLoS ONE 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores Bassino, J. Salud Mental en la Comunidad. 2020. p. 61.

- Dhami, S.S.; Bhatt, L. Validation of Global Mental Health Assessment Tool in Western Development Region, Nepal: A Cross Sectional Study. 2020.

- Sharma, V.K.; Lepping, P.; Cummins, A.G.; Copeland, J.R.; Parhee, R.; Mottram, P. The Global Mental Health Assessment Tool--Primary Care Version (GMHAT/PC). Development, reliability and validity. World Psychiatry 2004, 3, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- GoRaymi. Valle del Chota [s.f.]. Available online: https://www.goraymi.com/es-ec/imbabura/ibarra/comunidades/valle-chota-akvn62nxv.

- Tejada, P.; Polo, G.; Jaramillo, L.; Sharma, V. Psychiatric morbidity in medically ill patients by means of the Spanish version of the Global Mental Health Assessment Tool - Primary Care (GMHAT/PC). International Journal of Culture and Mental Health 2017, 10, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Lepping, P.; Krishna, M.; Durrani, S.; Copeland, J.; Mottram, P.; et al. Mental health diagnosis by nurses using the Global Mental Health Assessment Tool: a validity and feasibility study. The British journal of general practice: the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners 2008, 58, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Jagawat, S.; Midha, A.; Jain, A.; Tambi, A.; Mangwani, L.K.; et al. The Global Mental Health Assessment Tool-validation in Hindi: A validity and feasibility study. Indian Journal of Psychiatry 2010, 52, 316–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, L.; Guthold, R.; Cowan, M.; Savin, S.; Bhatti, L.; Armstrong, T.; et al. The World Health Organization STEPwise Approach to Noncommunicable Disease Risk-Factor Surveillance: Methods, Challenges, and Opportunities. Am J Public Health 2016, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.H.; Macfarlane, D.J.; Lam, T.H.; Stewart, S.M. Validity of the international physical activity questionnaire short form (IPAQ-SF): A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2011, 8, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cénat, J.M.; Moshirian Farahi, S.M.M.; Gakima, L.; Mukunzi, J.; Darius, W.P.; Diao, D.G.; et al. Prevalence and moderators of depression symptoms among black individuals in Western Countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis among 1.3 million people in 421 studies. The Lancet Regional Health - Americas 2025, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, S.A.-O.; Coelho, R.; Millett, C.; Saraceni, V.; Coeli, C.M.; Trajman, A.; et al. Racial inequalities in mental healthcare use and mortality: a cross-sectional analysis of 1.2 million low-income individuals in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 2010-2016. BMJ Glob Health 2023, 8, e013327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organización Panamericana de la S. Informe mundial sobre la salud mental: Transformar la salud mental para todos. Technical reports. Washington, D.C.: OPS; 2023 2023. Report No.: 978-92-75-32771-5 (PDF) 978-92-75-12771-1 (versión impresa). ISBN Report No.: 978-92-75-32771-5 (PDF) 978-92-75-12771-1.

- Kwate, N.O.; Goodman, M.S. Cross-sectional and longitudinal effects of racism on mental health among residents of Black neighborhoods in New York City. Am J Public Health 2015, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, A.I.C.; Surachman, A.; Armendariz, M. Where I'm Livin' and How I'm Feelin': Associations among community stress, gender, and mental-emotional health among Black Americans. Soc Sci, Med. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Escobar, F.J.; Osorio-Cuéllar, G.V.; Pacichana-Quinayaz, S.G.; Rangel-Gómez, A.N.; Gomes-Pereira, L.D.; Fandiño-Losada, A.A.-O.; et al. Impacts of violence on the mental health of Afro-descendant survivors in Colombia. MEDICINE, CONFLICT AND SURVIVAL 2021, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvis-Palacios, L.F.; Álzate-Posada, M.L. Remando, remando salgo adelante entre la lucha y el sufrimiento: salud mental y emocional en mujeres adultas mayores afrochocoanas. Index de Enfermería 2024, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gili, M.; García Campayo, J.; Roca, M. Crisis económica y salud mental. Informe SESPAS 2014. Gaceta Sanitaria 2014, 28, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCance-Katz, E.F. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA): New Directions. Psychiatric Services 2018, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, M.C.; Yangchen, T.; Lehner, T.; Sullivan, P.F.; Pato, C.N.; McIntosh, A.; et al. The epidemiology of psychiatric disorders in Africa: a scoping review. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, E.E.M.; Peralta, J.; Rodrigue, A.; Mathias, S.; Mollon, J.; Leandro, A.; et al. Differential gene expression study in whole blood identifies candidate genes for psychosis in African American individuals. Schizophrenia Research 2025, 280, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, B.S. Neurobiological and Systemic Effects of Chronic Stress. Chronic Stress 2017, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grayson, A.M. Addressing the Trauma of Racism from a Mental Health Perspective within the African American Community. Dela J Salud Pública 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricks, J.; Horan, J. Associations Between Childhood Sexual Abuse, Intimate Partner Violence Trauma Exposure, Mental Health, and Social Gender Affirmation Among Black Transgender Women. Health Equity 2023, 7, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population.

| Variable |

Frequency |

Percentage of total |

| Sex |

|

|

| Female |

341 |

61.2% |

| Mal |

216 |

38.8% |

| Total |

557 |

100% |

| Age |

|

|

| Young adults |

199 |

35.7% |

| Middle – aged adults |

164 |

29.4% |

| Older adults |

194 |

34.8% |

| Marital status |

|

|

| Married |

183 |

32.9% |

| Divorced |

30 |

5.4% |

| Separated |

21 |

3.8% |

| Single |

195 |

35% |

| Common-law union |

62 |

11.1% |

| Widowed |

66 |

11.8% |

| Educational level |

|

|

| None |

37 |

6.6% |

| Primary |

264 |

47.7% |

| Secondary |

208 |

37.3% |

| Higher education |

48 |

8.6% |

| Economic income |

|

|

| Above minimum wage |

68 |

12.2% |

| Below minimum wage |

489 |

87.8% |

| Family type |

|

|

| |

|

|

| Nuclear family |

288 |

51.7% |

| Single-parent family |

118 |

21.2% |

| Extended family |

54 |

9.7% |

| Large/complex family |

38 |

6.8% |

| Other |

58 |

10.6 |

Table 4.

Sociodemographic variables and risk factors in relation to the presence of mental disorders.

Table 4.

Sociodemographic variables and risk factors in relation to the presence of mental disorders.

| Variable |

With Mental Disorder |

Without Mental Disorder |

Total |

% With Mental Disorder |

p-value |

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

| Female |

226 |

115 |

341 |

40.6% |

0.006 |

| Male |

112 |

104 |

216 |

20.1% |

|

| Age |

|

|

|

|

|

| Young Adults |

113 |

86 |

199 |

20.3% |

0.3 |

| Middle-aged Adults |

106 |

58 |

164 |

19% |

|

| Older Adults |

119 |

75 |

194 |

21.4% |

|

| Marital Status |

|

|

|

|

|

| Married |

111 |

72 |

183 |

60.7% |

0.073 |

| Divorced |

23 |

7 |

30 |

76.7% |

|

| Separated |

11 |

10 |

21 |

52.4% |

|

| Single |

115 |

80 |

195 |

59.0% |

|

| Common-law union |

31 |

31 |

62 |

50.0% |

|

| Widowed |

47 |

19 |

66 |

71.2% |

|

| Education Level |

|

|

|

|

|

| None |

23 |

14 |

37 |

62.2% |

0.094 |

| Primary |

173 |

91 |

264 |

65.5% |

|

| Secondary |

119 |

89 |

208 |

57.2% |

|

| Higher |

23 |

25 |

48 |

48.9% |

|

| Economic Income |

|

|

|

|

0.014 |

| Above minimum wage |

32 |

36 |

68 |

47.1% |

|

| Below minimum wage |

306 |

183 |

489 |

62.6% |

|

| Family Type |

|

|

|

|

|

| Nuclear family |

171 |

114 |

285 |

60% |

|

| Single-parent family |

78 |

40 |

118 |

66.1% |

0.236 |

| Extended family |

32 |

22 |

54 |

59.3% |

|

| Large family |

18 |

20 |

38 |

47.4% |

|

| Stress Level |

|

|

|

|

|

| Mild Stress |

132 |

79 |

211 |

62.6% |

<.001 |

| Moderate Stress |

73 |

20 |

93 |

78.5% |

|

| Severe Stress |

37 |

2 |

39 |

94.9% |

|

| No Stress |

96 |

118 |

214 |

44.9% |

|

| Abuse and Maltreatment |

|

|

|

|

|

| Physical, sexual, psychological |

7 |

0 |

7 |

100% |

<.001 |

| Physical |

29 |

7 |

36 |

80.6% |

|

| Psychological |

87 |

27 |

114 |

76.3% |

|

| Sexual |

2 |

1 |

3 |

66.7% |

|

| Total |

338 |

219 |

557 |

60.7% |

|

Table 5.

Sociodemographic Variables and Risk Factors in Relation to the Presence of Mental Disorders.

Table 5.

Sociodemographic Variables and Risk Factors in Relation to the Presence of Mental Disorders.

| Sociodemographic Variable |

Gender |

Major Depressive Disorder n (%) p-value |

Anxiety Disorder n (%) p-value |

Psychosis n (%) p-value |

| Education Level |

|

|

|

|

| Primary or less |

Female |

66 (35.1%) |

27 (14.4%) |

30 (16%) |

| |

Male |

27 (23.9%) |

12 (10.6%) |

9 (8%) |

| |

p-valor |

0.041 |

0.46 |

0.046 |

| Secondary and higher |

Female |

25 (16.3%) |

31 (20.3%) |

16 (10.4%) |

| |

Male |

19 (18.4%) |

13 (12.6) |

12 (11.6%) |

| |

p-valor |

0.66 |

NaN |

0.7 |

| Economic Income |

|

|

|

|

| Above minimum wage |

Female |

4 (16,7%) |

3 (12.5%) |

2 (8.3%) |

| |

Male |

4 (9.1%) |

9 (20.5%) |

2 (4.5%) |

| Below minimum wage |

Female |

83 (26.8%) |

55 (17.4%) |

44 (13.9%) |

| |

Male |

42 (24,9%) |

16 (9.3%) |

19 (11%) |

| |

p-valor |

0.311 |

< 0.01 |

0.417 |

| Marital Status |

|

|

|

|

| Married |

Female |

29 (24.8%) |

19 (60.7%) |

12 (26.1%) |

| |

Male |

13 (19.7%) |

11 (39.3%) |

4 (19%) |

| Divorced |

Female |

6 (33.3%) |

2 (66.7%) |

3 (60%) |

| |

Male |

2 (16.7%) |

1 (33,3%) |

2 (40%) |

| Separated |

Female |

6 (54.5%) |

2 (66.7%) |

2 (100%) |

| |

Male |

2 (20%) |

1 (33.3%) |

|

| Single |

Female |

24 (20.9%) |

23 (76.7) |

19 (67.9%) |

| |

Male |

17 (21.2) |

7 (23.3%) |

9 (32.1%) |

| Common-law union |

Female |

8 (25.8%) |

8 (80%) |

9 (18.4%) |

| |

Male |

8 (25.8%) |

2 (20%) |

3 (17.6%) |

| Widowed |

Female |

18 (36.7%) |

6 (66.7%) |

9 (18.4%) |

| |

Male |

4 (23.5%) |

3 (33.3%) |

3 (17.6%) |

| |

p-valor |

0.299 |

0.801 |

0.3 |

Table 6.

Association between Stress Level, Abuse and Maltreatment with Prevalent Mental Disorders.

Table 6.

Association between Stress Level, Abuse and Maltreatment with Prevalent Mental Disorders.

| Mental Disorder |

N (%)

|

Stress Level

Mann-Whitney U Test (p-value) |

Abuse and Maltreatment

Mann-Whitney U Test (p-value) |

| Major depressive disorder |

137 (24.6%) |

19544 (< 0.001) |

23119 (< 0.001) |

| Anxiety disorder |

83 (14.9%) |

16615 (0.016) |

18250 (0.185) |

| Psychosis |

67 (12%) |

13251 (0.006) |

14219 (0.025) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).