Submitted:

11 December 2025

Posted:

12 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microwave-Assisted Dyeing Setup

2.2. Dyeing Procedure

2.3. Dyeing Kinetics Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

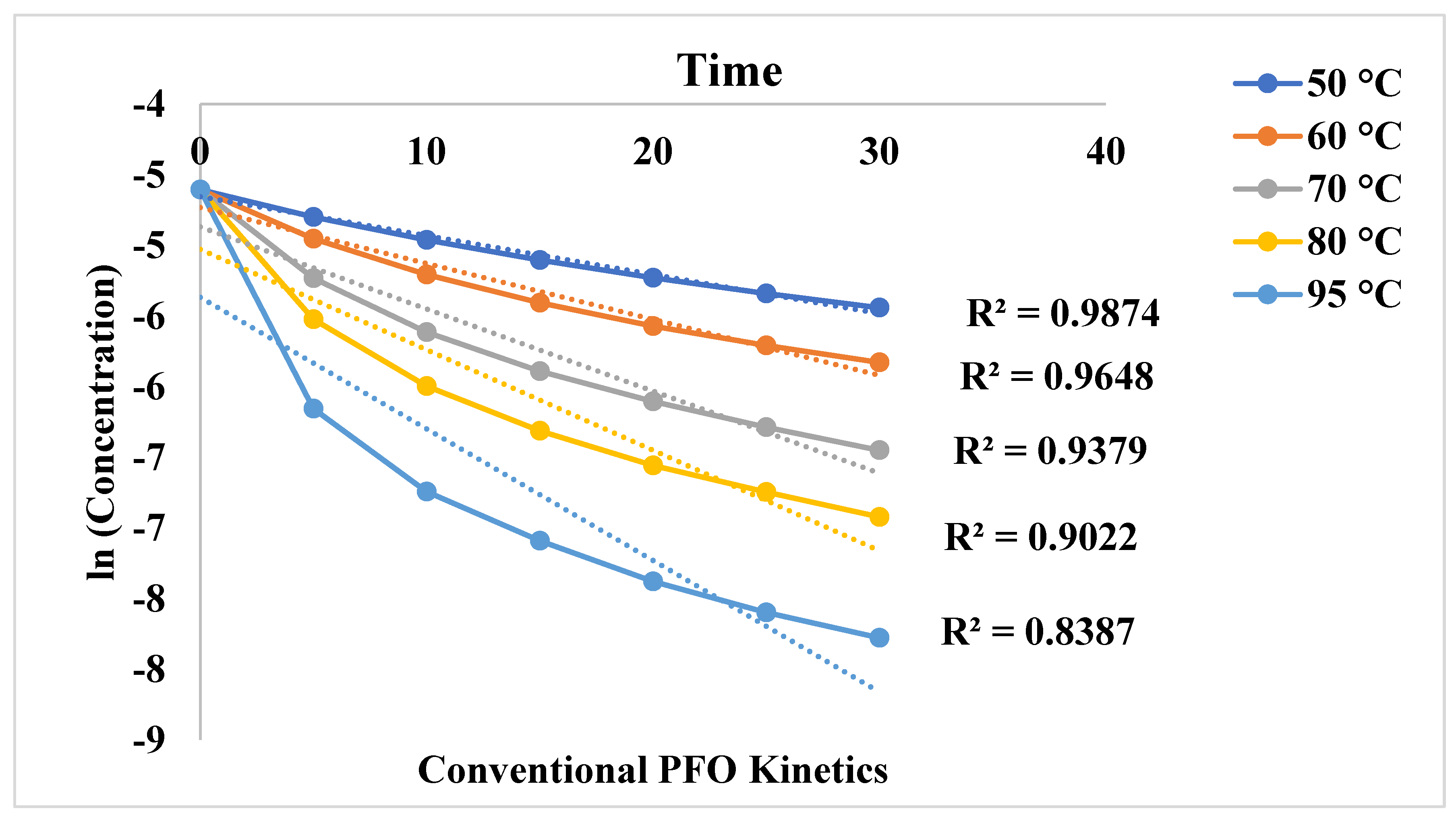

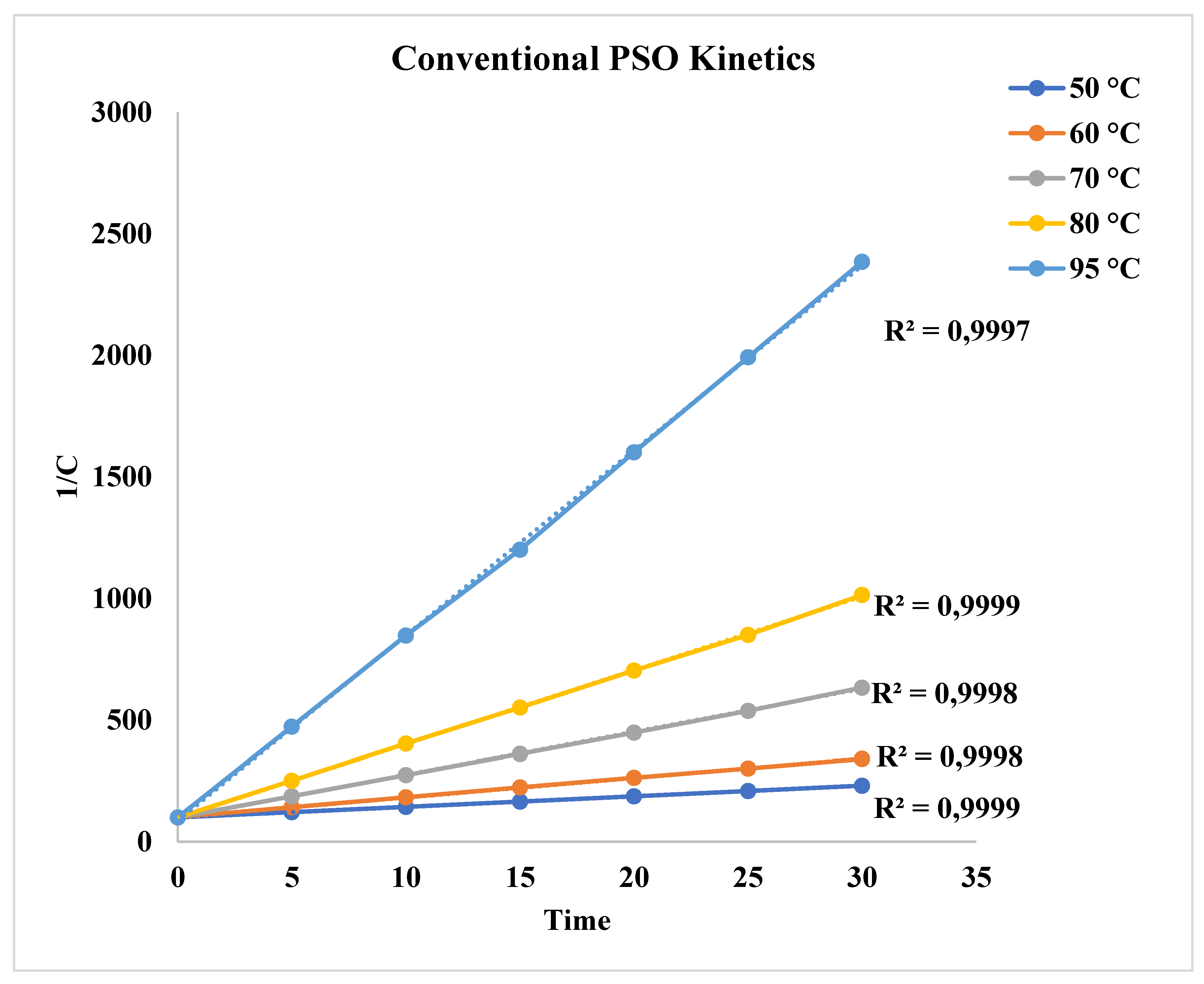

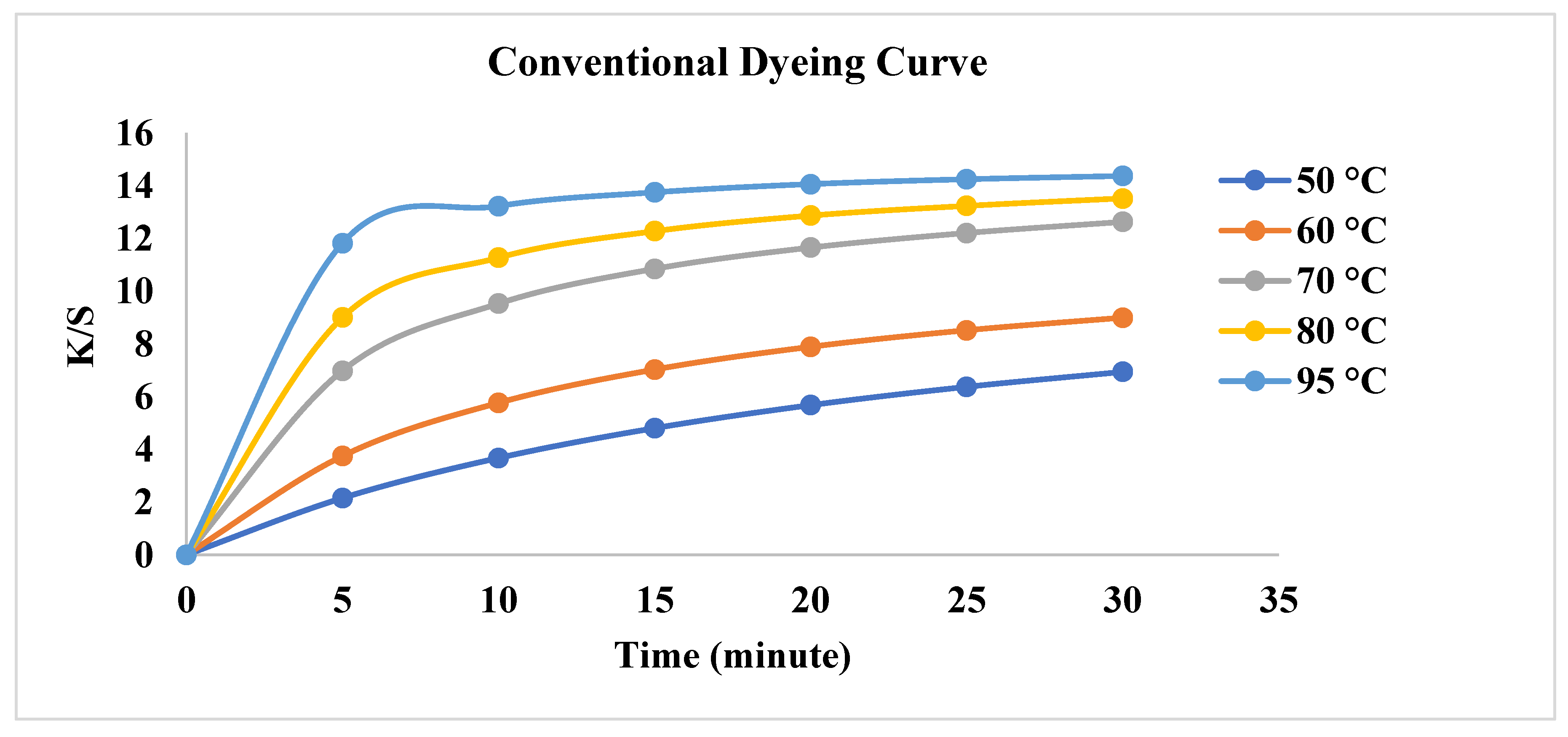

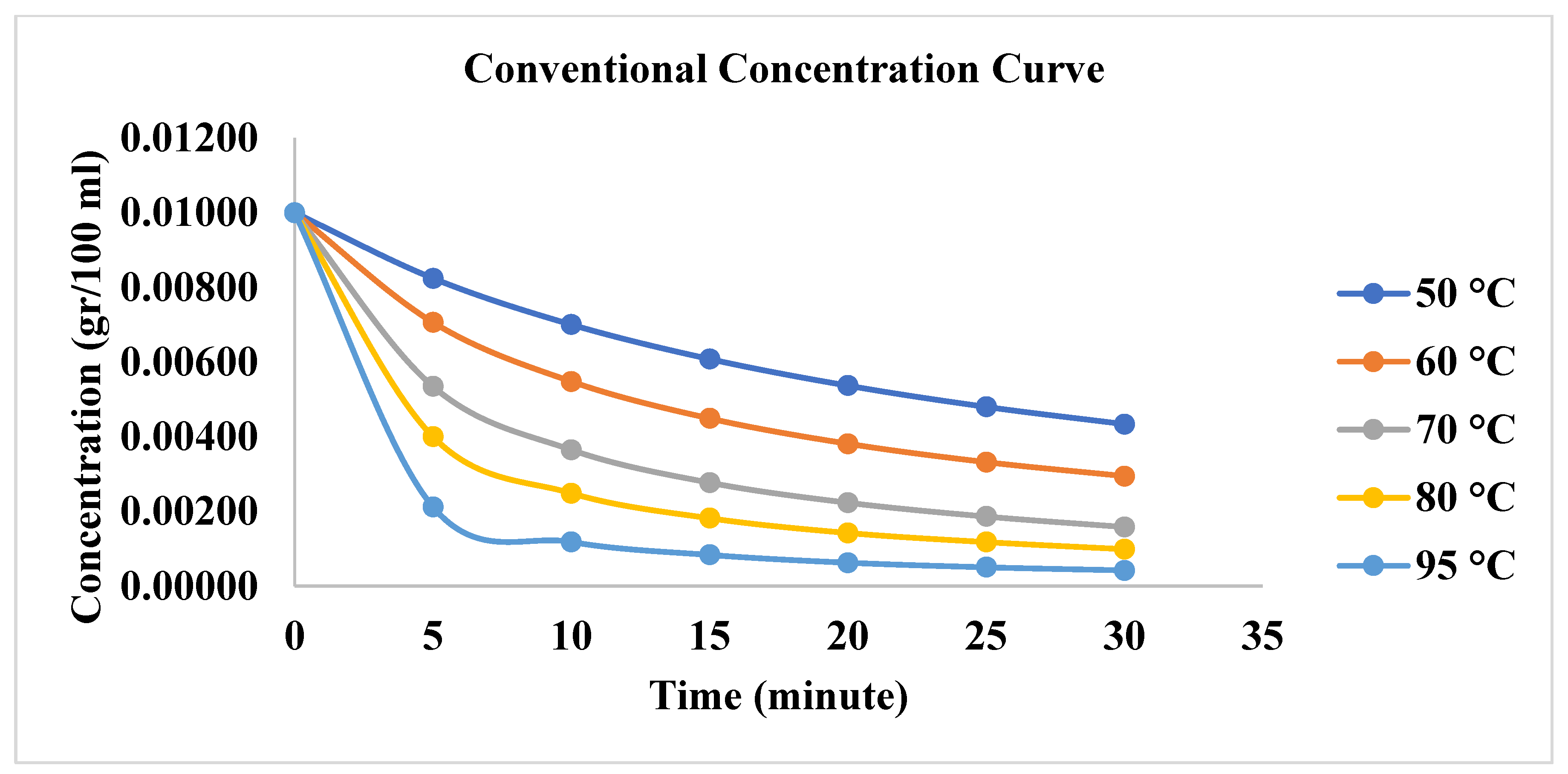

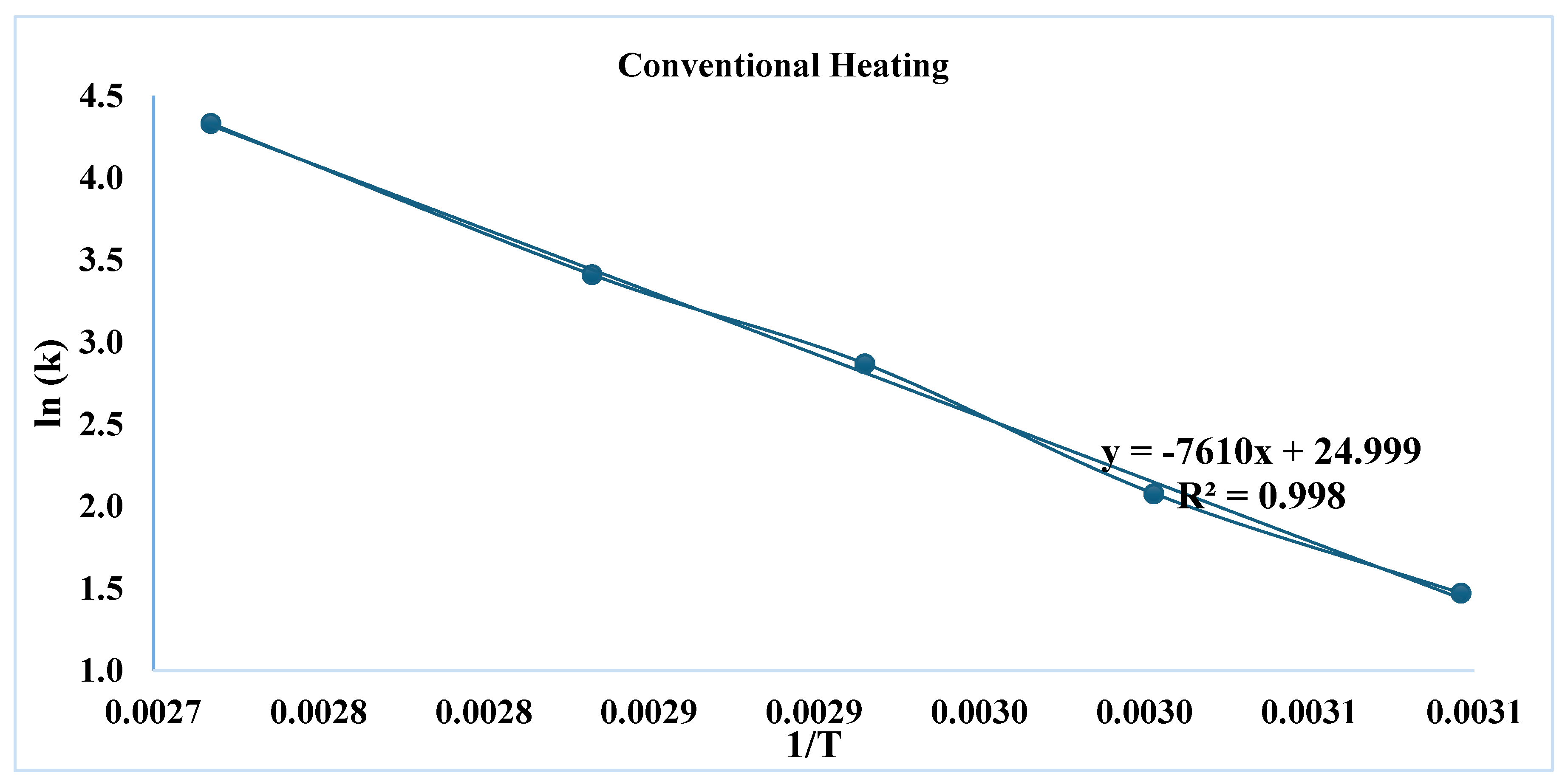

3.1. Effect of Conventional Heating on Dyeing Kinetics

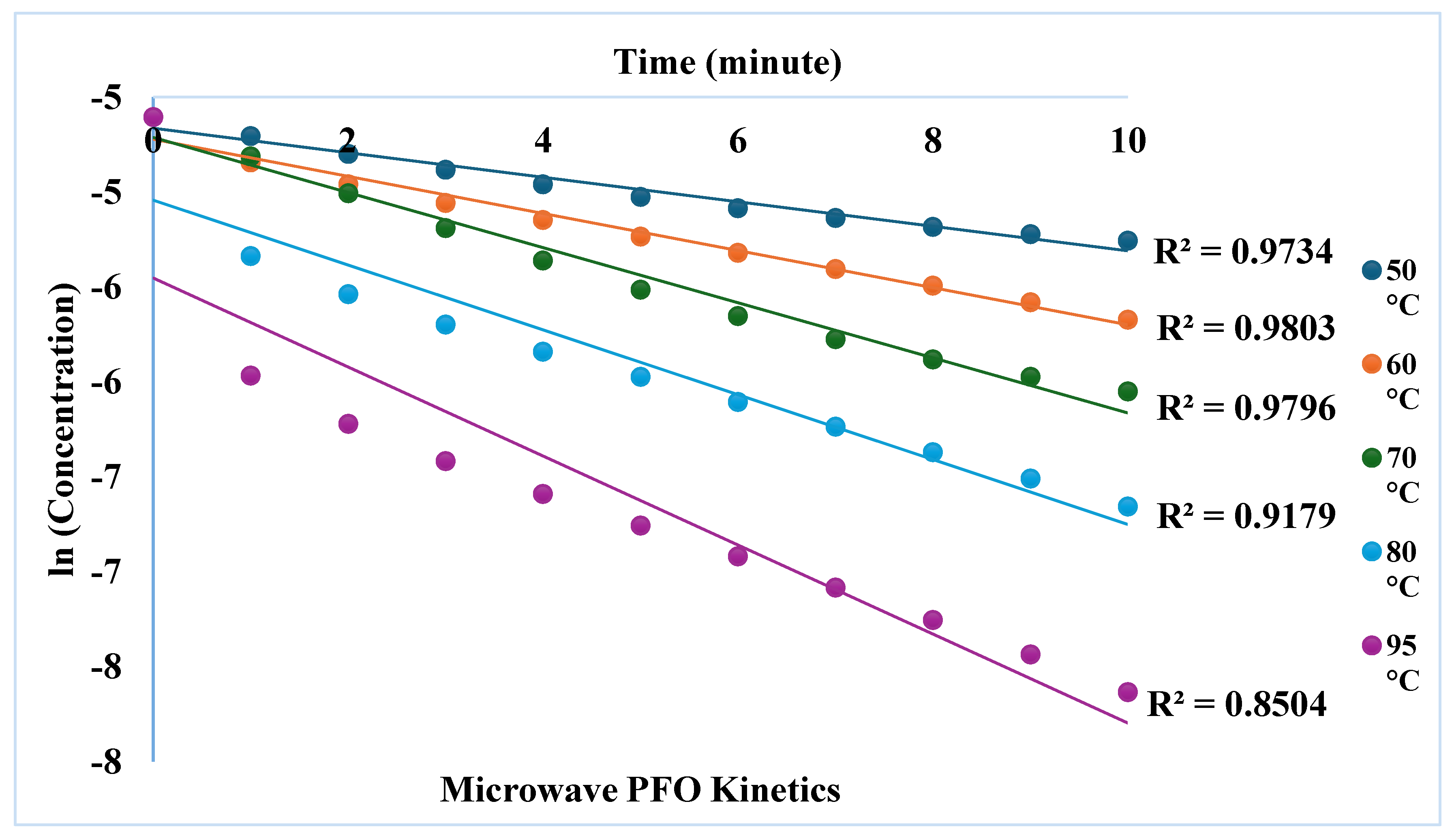

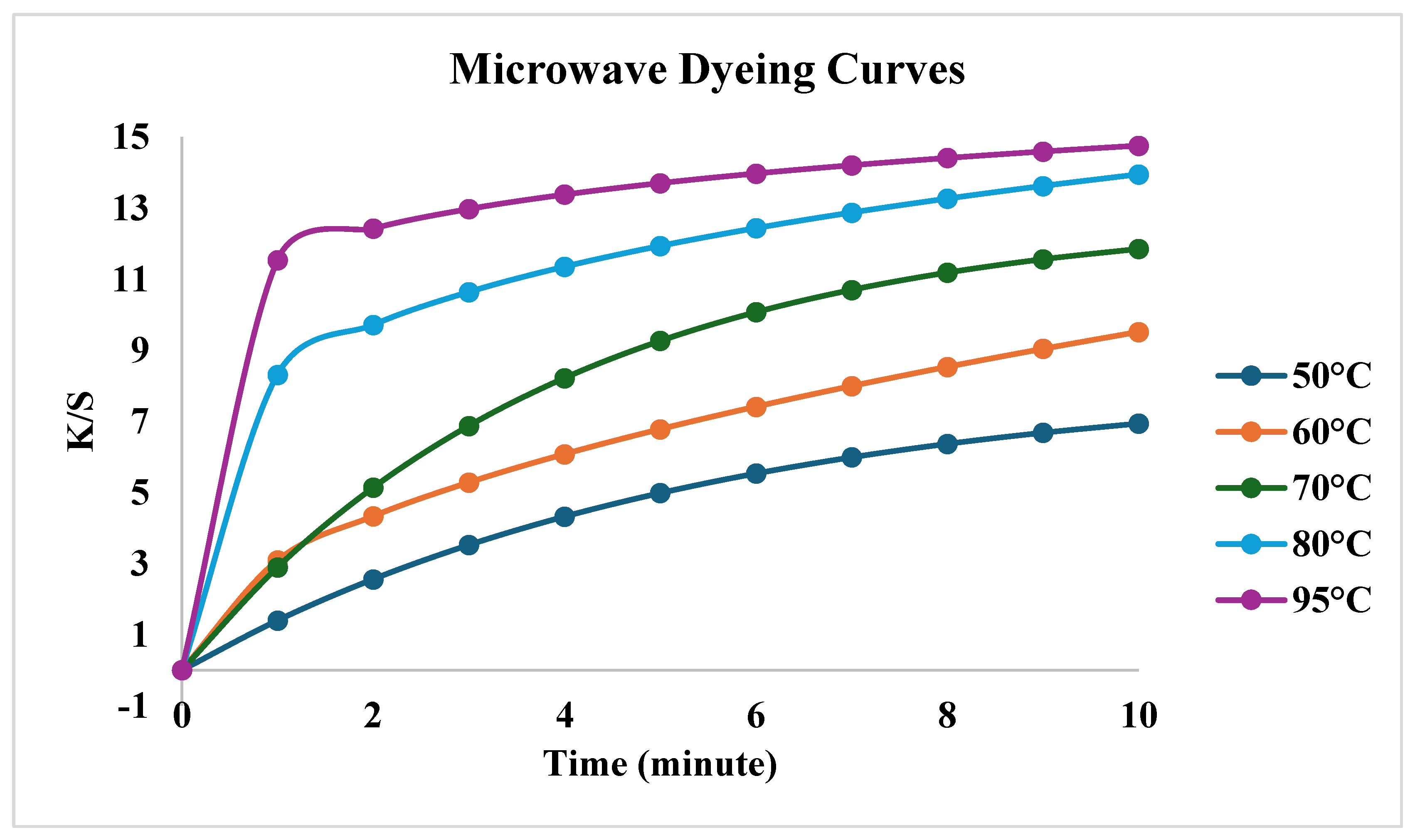

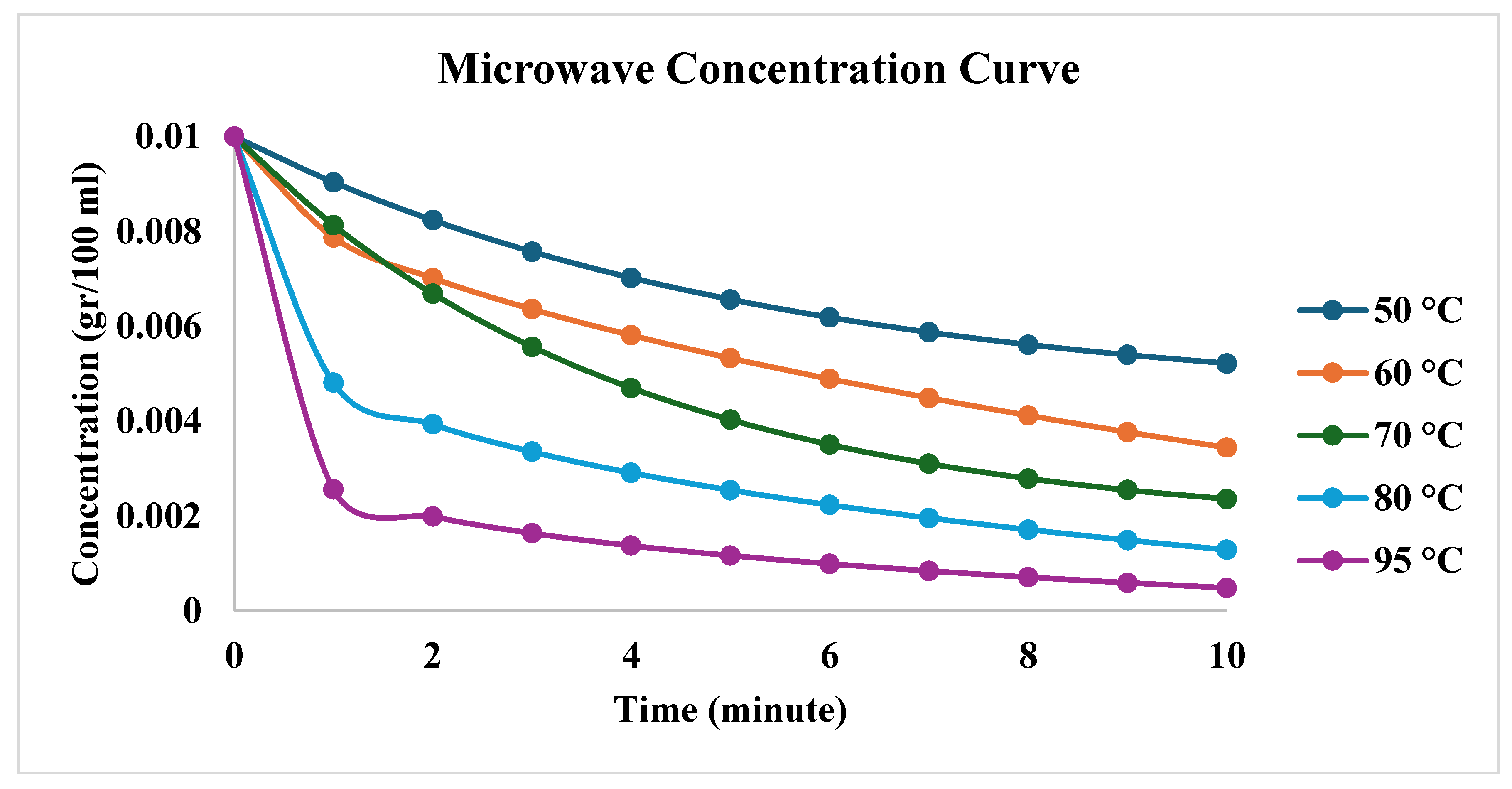

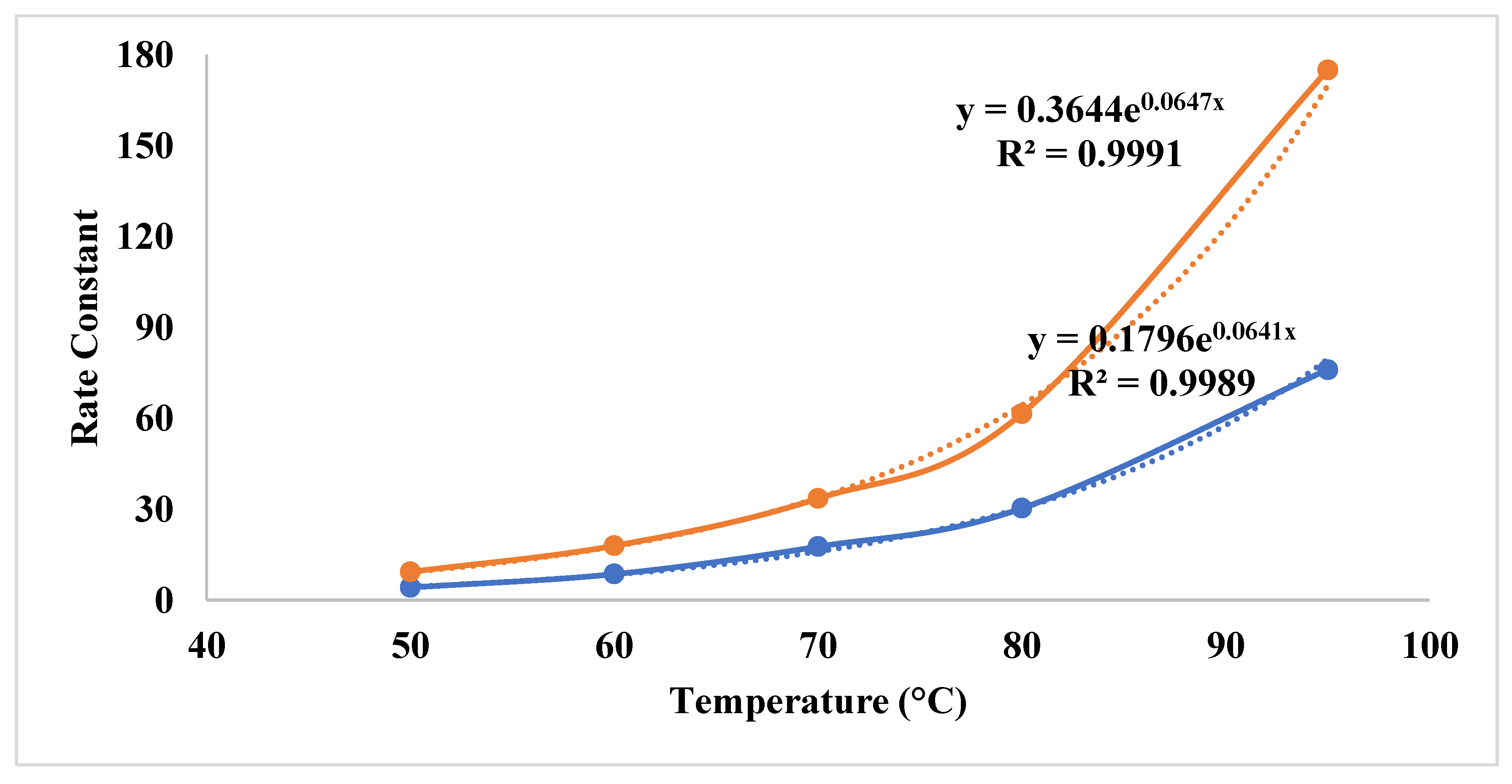

3.2. Effect of Microwave Power on Dyeing Kinetics

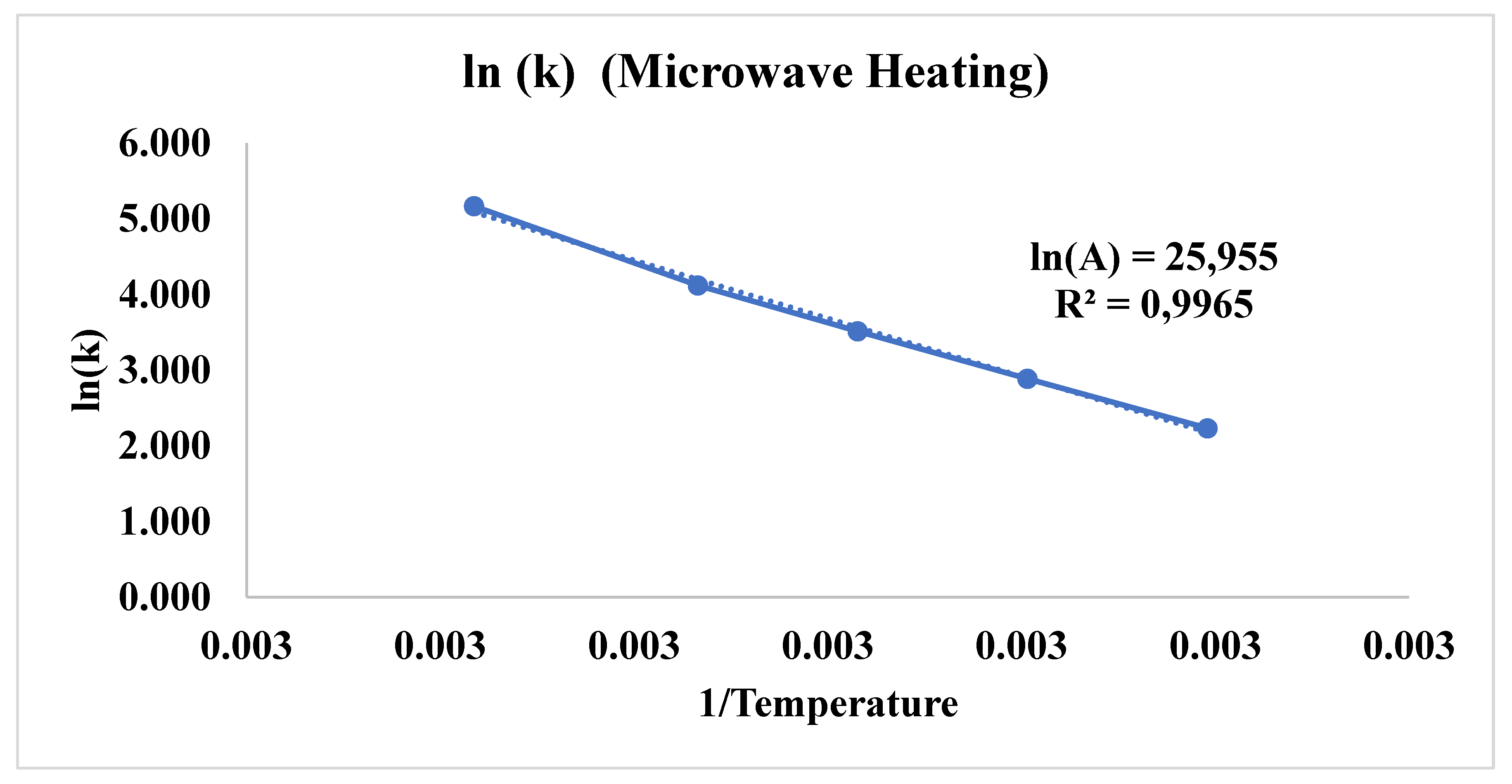

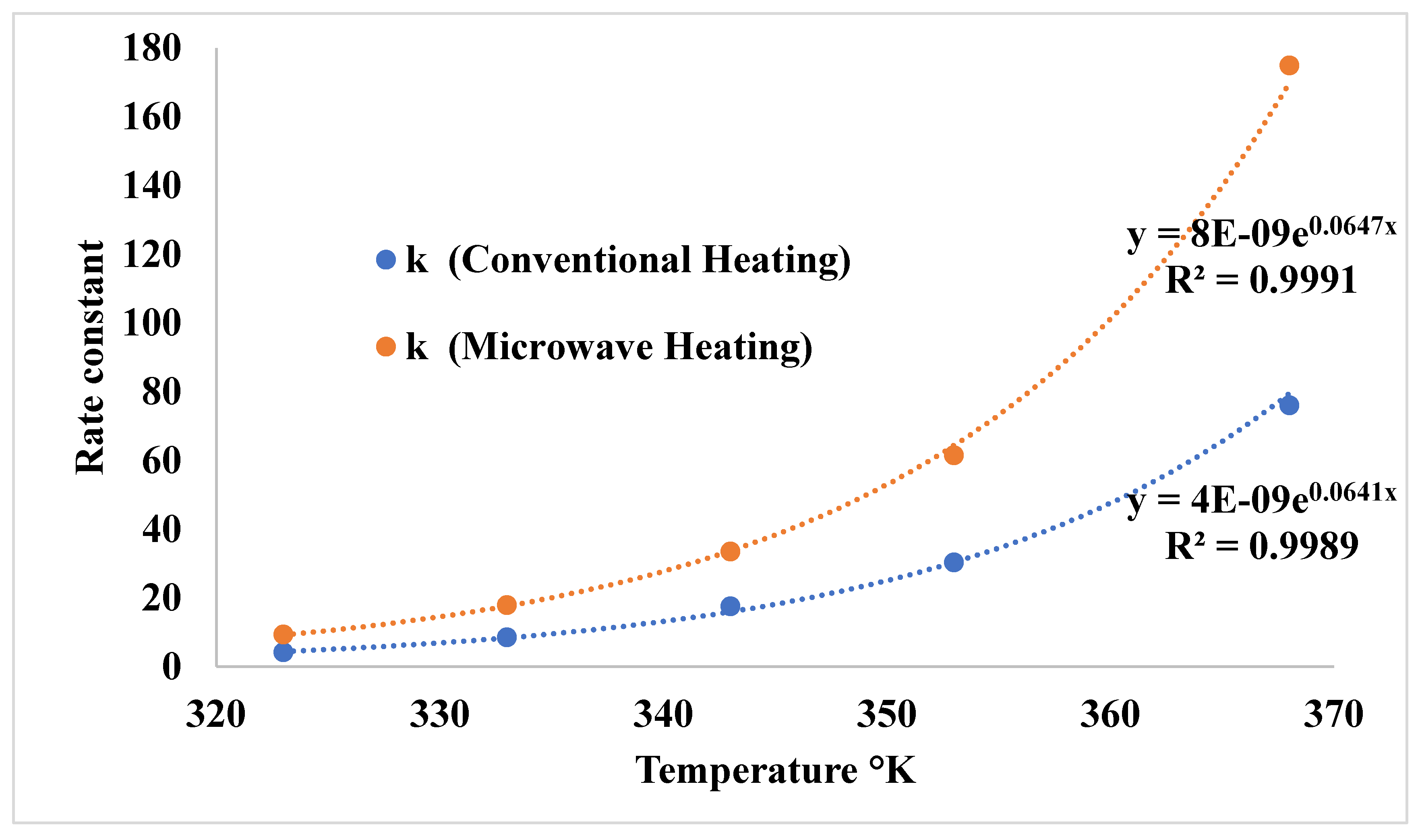

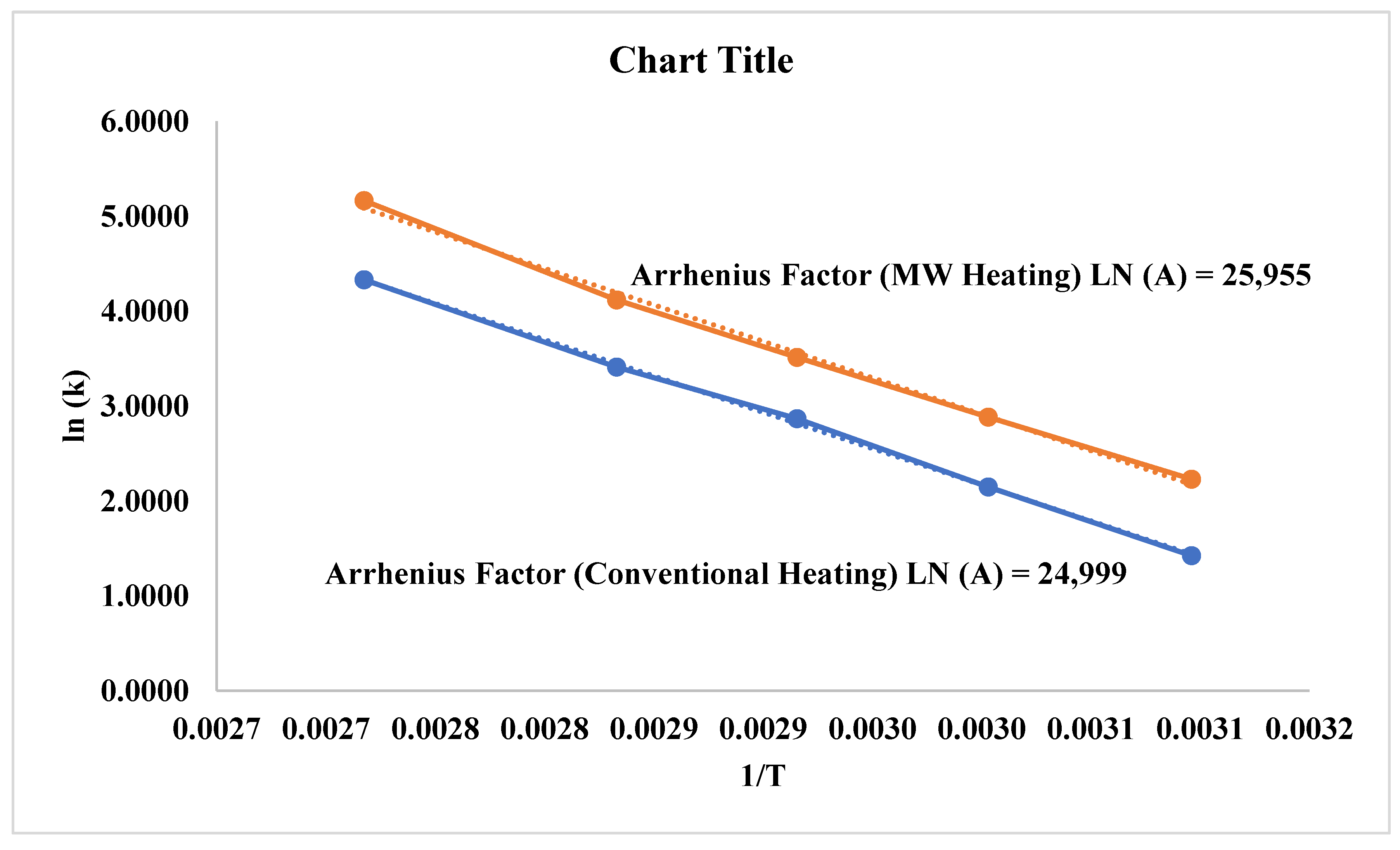

3.3. Comparison of Microwave and Conventional Heating on Dyeing Kinetics

4. Conclusions

- ɣ: The number of adjacent jump sites (The number of possible neighboring positions to which an atom or molecule can migrate)

- λ: The jump distance (The average distance an atom or molecule travels in a single diffusion jump)

- Γ: The jump frequency (The rate at which an atom or molecule makes successful jumps from one site to another) [42].

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Acknowledgments

References

- Böcek, Nevin (2001), Investigation of Fiber and Temperature Interaction in Dyeing of Synthetic Fibers, [Master’s thesis;Sakarya University]. YÖK National Thesis Center. Available online: https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/.

- Haggag, K.; El-Molla, M. M.; Ahmed, K. A. Dyeing of Nylon 66 Fabrics Using Disperse Dyes by Microwave Irradiation Technology. International Research Journal of Pure & Applied Chemistry 2015, 8(2), 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usluoğlu, A.; Teker, M. Investigation of Dyeing Kinetics of Cotton Fiber with C.I. Reactive Yellow 138:1 Dyestuff in Microwave Environment. Journal of the Institute of Science of Yüzüncü Yıl University 2024, Vol.29, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiğit, E.A.; Teker, M. Disperse Dyeability of Polypropylene Fibers via Microwave and Ultrasonic Energy - Polymer and Polymer Composites. 2011, Vol.19, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Ma, J.; Wu, Y.; Niu, T.; Sun, D.; Fang, L.; Zhang, X. Investigation on dyeing mechanism of modified cotton fiber. RSC Adv. 2022, vol. 12(no. 49), 31596–31607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggag, K.; El-Molla, M. M.; Mahmoued, Z. M. Dyeing of Cotton Fabric using Reactive Dyes by Microwave Irradiation Technique. Indian J. Fibre Text. Res. 2014, vol. 39(no. 4), 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. M.; Ahmed, M.; Jalil, M. A.; Mondal, M. I. H. The effect of microwave preheating on the dyeing of wool fabric with a reactive dye. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2008, 108(1), 314–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Meng, J. A novel process of dyeing wool with acid dyes under microwave irradiation. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2009, 113(5), 2798–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. S.; Leem, S. G.; Ghim, H. D.; Kim, J. H.; Lyoo, W. S. Microwave Heat Dyeing of Polyester Fabric. Fibers and Polymers 2003, 4(4), 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazal, H. A. Microwave Irradiation as A New Novel Dyeing of Polyamide 6 Fabrics by Reactive Dyes. Egyptian Journal of Chemistry 2020, 63(6), 2125–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocak, D.; Akalin, M.; Merdan, N.; Sahinbaskan, B.Y. Effect of Microwave Energy on Disperse Dyeability of Polypropylene Fibres. Marmara Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences 2015, Vol. 27, Special(Issue-1), 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggag, K.; Hanna, H.L.; Youssef, B.M.; El-Shimy, N.S. Dyeing Polyester With Microwave Heating Using Disperse Dyestuffs. American Dyestuff Reporter 1995, 84, 22–36. [Google Scholar]

- Büyükakıncı, Y. B.; Karada, R.; Guzel, E.T. Organic cotton fabric dyed with dyer’s oak and barberry dye by microwave irradiation and conventional methods. Industria Textila 2021, Vol No, 72, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, M.; Haggag, K. M.; Boraie, W. E; Aljaafari, A.; Al-Faiyz, Y. Synthesis and Characterization of Inorganic Pigment Nanoparticles for Textile Coloration Using Microwave Techniques. AATCC Journal of ResearchVolume 2016, 3(Issue 3), Pages 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, M.J.; Bhat, N.V. Effect of microwave pretreatment on the dyeing behaviour of polyester fabric. Society of Dyers and Colourists, Color. Technol. 127, 365–371. [CrossRef]

- Popescu, V.; Astanei, D.G.; Burlica, R.; Popescu, A.; Munteanu, C.; Ciolacu, F.; Ursache, M.; Ciobanu, L.; Cocean, A. Sustainable and cleaner microwave-assisted dyeing process for obtaining eco-friendly and fluorescent acrylic knitted fabrics. Journal of Cleaner Production Volume 2019, 232, Pages 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keglevich, G. The Application of Microwaves in the Esterification of P-Acids. Current Microwave Chemistry 2022, *9*(2), 62–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffar, A.; Adeel, S.; Habib, N.; Jalal, F.; Ul-Haq, A.; Munir, B.; Ahmad, A.; Jahangeer, M.; Jamil, Q. Effects of Microwave Radiation on Cotton Dyeing with Reactive Blue 21 Dye, Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2019, Vol. 28(No. 3), 1687–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Etaibi, A.M.; El-Apasery, M.A. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Azo Disperse Dyes for Dyeing Polyester Fabrics: Our Contributions over the Past Decade. Polymers 2022, 14, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshemy, N.S.; Haggag, K. New Trend in Textile Coloration Using Microwave Irradiation. J. Text. Color. Polym. Sci. 2019, Vol. 16(No.1), pp 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öner, E.; Büyükakıncı, Y.; Sökmen, N. Microwave-assisted dyeing of poly(butylene terephthalate) fabrics with disperse dyes. Coloration Technology 2013, 129(2), 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyükakıncı, Y.; Sökmen, N.; Öner, E. Microwave assisted exhaust dyeing of polypropylene. Paper presented at the 4th Centrel European Conference, Liberec, Czech Republic, 7-9 September 2005; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Haggag, K. Fixation of Pad-Dyeing on Cotton Using Microwave Heating. American Dyestuff Reporter 1990, vol. 79, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lill, J. R. Microwave-Assisted Proteomics 2009.

- Hayes, B. L. Microwave Synthesis 2002.

- Can, M. C. Microwave Heating as a Tool for Sustainable Chemistry; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Trotman, E.R. Dyeing and Chemical Technology of Textile Fibres; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Özcan, Y. Textile Fiber and Dyeing Technique; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer, M.; Taylor, P. Chemical Kinetics and Mechanism; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- House, J. E. Principles of Chemical Kinetics; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vassileva, V.; Zheleva, Z.; Valcheva, E. The Kinetic Model of Dye Fixation on Cotton Fibers. Journal of University of Chemical Technology and Metallurgy 2008, 43(3), 323–326. [Google Scholar]

- Teker, M; Imamoglu, M; Bocek, N. - Adsorption of Some Textile Dyes on Activated Carbon Prepared From Rice Hulls - Fresenıus Environmental Bulletin - Vol.18 - pp.709 - ISSN: 1018-4619 - English - Article - 2009 - WOS:000266898500009. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujhelyiova, A.; Bolhova, E.; Oravkinova, J.; Tin, R.; Marcin, A. Kinetics of dyeing process of blend polypropylene/polyester fibres with disperse dye. Dyes and Pigments 2007, 72, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, MN; Hossain, MT; Hasan, MZ; Islam, K; Rokonuzzaman, M; Islam, MA; Khandaker, S; Bashar, MM. Adsorption, Kinetics and Thermodynamics of Reactive Dyes on Chitosan Treated Cotton Fabric. Textile & Leather Review 2023, 6, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, M. J.; Bezerra, F. M.; Meng, X.; Qian, H.; Immich, A. P. S. Kinetics of Dyeing in Continuous Circulation with Direct Dyes: Tencel Case. World Journal of Textile Engineering and Technology 2019, 5, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshemy, N. S.; Elshakankery, M. H.; Shahien, S. M.; Haggag, K.; El-Sayed, H. Kinetic Investigations on Dyeing of Different Polyester Fabrics Using Microwave Irradiation. Egyptian Journal of Chemistry 2017, 60(Conference Issue), 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujhelyiova, A.; Bolhova, E.; Oravkinova, J.; Tiňo, R.; Marcinčin, A. Kinetics of dyeing process of blend polypropylene/polyester fibres with disperse dye. Dyes and Pigments 2007, 72(2), 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alşan, H. G. Investigation of Dyeing Kinetics of Cotton Fiber with Disperse Dyestuff in Microwave Environment. Master’s thesis;Sakarya University, YÖK National Thesis Center, 2019. Available online: https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/.

- Hu, Q.; Siting, Ma; He, Z.; Liu; Pei, X. A revisit on intraparticle diffusion models with analytical solutions: Underlying assumption, application scope and solving method. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2024, Vol. 60, 10524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiğit Atabek, E. Investigation of Dyeability of Polypropylene Fiber. Doctoral thesis;Sakarya University, YÖK National Thesis Center, 2009. Available online: https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/.

- Huang, J.; Liu, F.; Zhang, J. Insights into adsorption rate constants and rate laws of preset and arbitrary orders. Separation and Purification Technology 2021, Vol.255, 117713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyuran, A. Dyeing of Synthetic Fibers in Microwave Environment. Master’s thesis;Sakarya University, YÖK National Thesis Center, 2010. Available online: https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/.

- Miklavc, a. Chem. Phys.Chem 2001, 552.

- Binner, J.G.P.; Hassine, N. A.; Cross, T. E. J. Mater. Sci. 1995, 30, 5389.56. [CrossRef]

- Garbacia, S.; Desai, B.; Lavaster, O.; Kappe, C. O. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 9136. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stadler, a.; Kappe, C. O. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2000, 2, 1363. [CrossRef]

- Hoz; Diaz-Ortiz, A.; Moreno, A. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2005, 34, 164. [CrossRef]

| First order | Second Order | |||

| Temperature | k1 (1/min) | R2 | k2(L/g.min) | R2 |

| 50 0C | 0,0275 | 0,9874 | 4,1579 | 0.9999 |

| 60 0C | 0,0396 | 0,9648 | 8,556 | 0.9998 |

| 70 0C | 0,0581 | 0,9379 | 17,660 | 0.9998 |

| 80 0C | 0,0711 | 0,9022 | 30,298 | 0.9999 |

| 95 0C | 0,0931 | 0,8387 | 76,063 | 0.9997 |

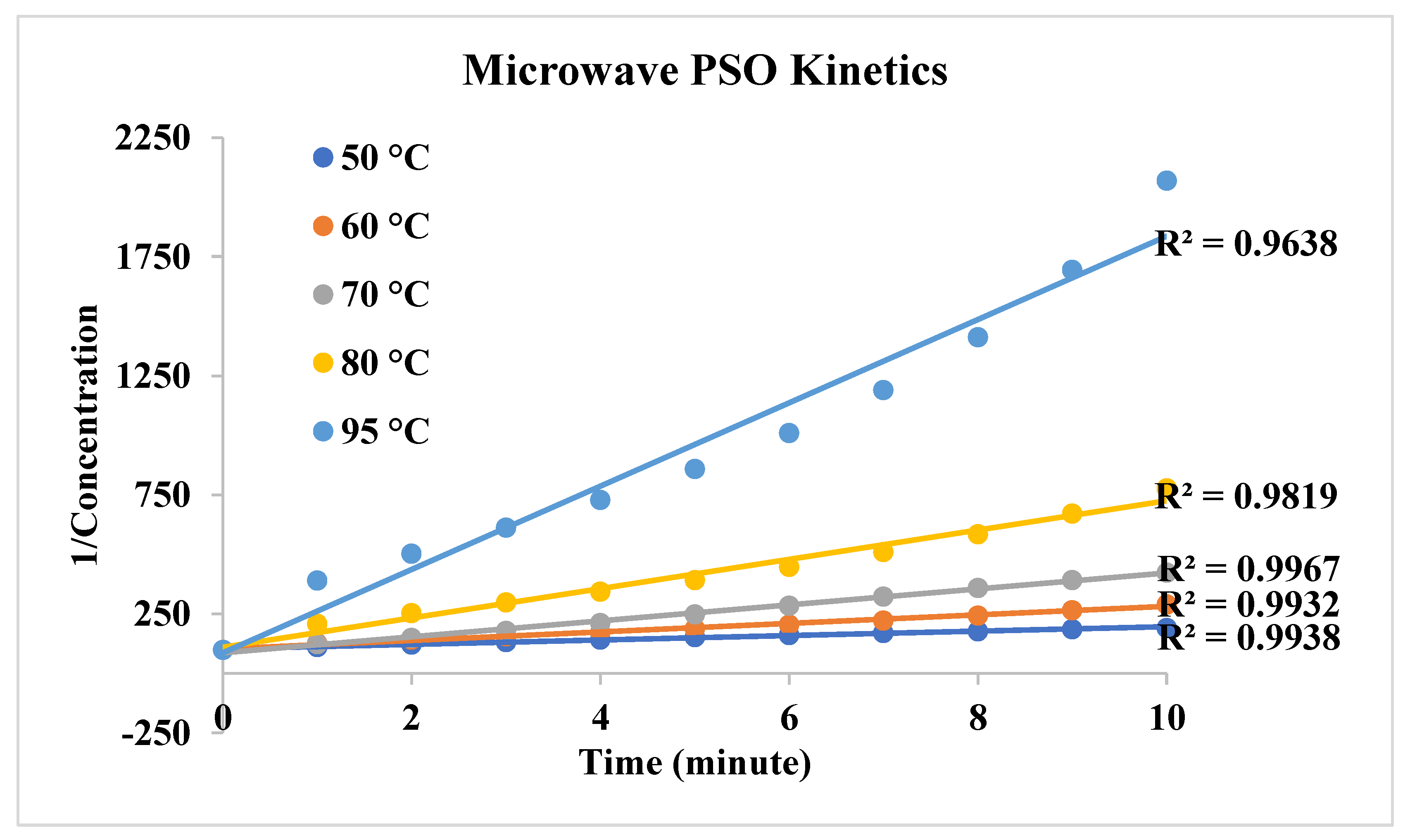

| First order | Second Order | |||

| Temperature | k1(1/min) | R2 | k2(lt/g.min) | R2 |

| 50 0C | 0,0646 | 0,9734 | 9,3013 | 0,9938 |

| 60 0C | 0,0977 | 0,9803 | 17,925 | 0,9932 |

| 70 0C | 0,1451 | 0,9796 | 33,52 | 0,9967 |

| 80 0C | 0,1708 | 0,9179 | 61,509 | 0,9819 |

| 95 0C | 0,2344 | 0,8504 | 174,94 | 0,9638 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).