Submitted:

11 December 2025

Posted:

12 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Study Period and COVID-19 Phase Definition

- Pre-Pandemic (January 1 to March 15, 2020), representing baseline conditions before mobility restrictions;

- Strict Lockdown (March 16 to May 3, 2020), characterized by mandatory home confinement, suspension of non-essential activities, and curfew enforcement;

- Phase 1 (May 4 to June 4, 2020), initial economic reactivation with limited activities;

- Phase 2 (June 5 to June 30, 2020), progressive reopening of additional sectors;

- Phase 3 (July 1 to September 26, 2020), broader economic reactivation; and

- Phase 4 (September 27 to December 31, 2020), advanced reopening with most sectors operational.

2.3. Data Sampling and Measurement

2.4. Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

2.5. Statistical Analysis Framework

2.5.1. Descriptive Statistics

2.5.2. Multiple Linear Regression Models

- Model 1 (Meteorology-Only)Y = β₀ + β₁(Temperature) + β₂(WindSpeed) + β₃(Humidity) + ε

- Model 2 (Full Model with COVID-19 Periods)where Y denotes daily pollutant concentration, Temperature (°C), Wind Speed (m s⁻¹) and Humidity (%) are continuous meteorological predictors, and Period₂–₆ are binary indicators for pandemic phases (reference: Pre-Pandemic). The error term ε is assumed normally distributed with constant variance. Meteorological predictors were selected based on their established roles in dispersion and atmospheric chemistry: temperature modulates photochemical reaction rates and boundary layer stability, wind speed controls dilution and transport, and humidity influences gas-to-particle conversion and wet deposition [39]. These meteorological variables have been identified as key predictors in Random Forest-based meteorological normalization studies across diverse urban settings [34,36,54,71].Y = β₀ + β₁(Temperature) + β₂(WindSpeed) + β₃(Humidity) + Σβᵢ(Periodi) + ε

2.5.3. Variance Decomposition and Effect Quantification

- Meteorological contributionR² Meteo = R² Model1

- COVID-19 contributionR² COVID = R² Model2 - R² Model1

- Relative percentage contributions%Meteo = (R² Meteo / R² Model2) × 100%COVID = (R² COVID / R² Model2) × 100

- Percentage change%Changei = [(Meani – Mean PrePandemic) / Mean PrePandemic] × 100 ± 1.96 × SE diff

2.5.4. Random Forest Analysis

2.5.5. Sensitivity Analyses

2.6. Health Impact Assessment

2.6.1. Concentration-Response Model

- Relative Riskwhere RR represents relative risk, β is the risk coefficient per unit increase (1 μg/m³) in PM2.5, and ΔPM2.5 corresponds to the change in mean concentration relative to the pre-pandemic reference period [89]. The attributable fraction (AF) was calculated as:RR = exp(β × Δ PM2.5)

- Attributable FractionAF = (RR - 1) / RR

- Attributable Deathsfollowing established methods in environmental health impact assessment [90].Deaths = Population × Baseline_Mortality_Rate × AF

2.6.2. Epidemiological Parameters

2.6.3. Population Estimation

2.6.4. Comparative Periods

2.6.5. Uncertainty Analysis

2.6.6. Model Assumptions and Limitations

2.7. Data Visualization

2.8. Software and Reproducibility

3. Results

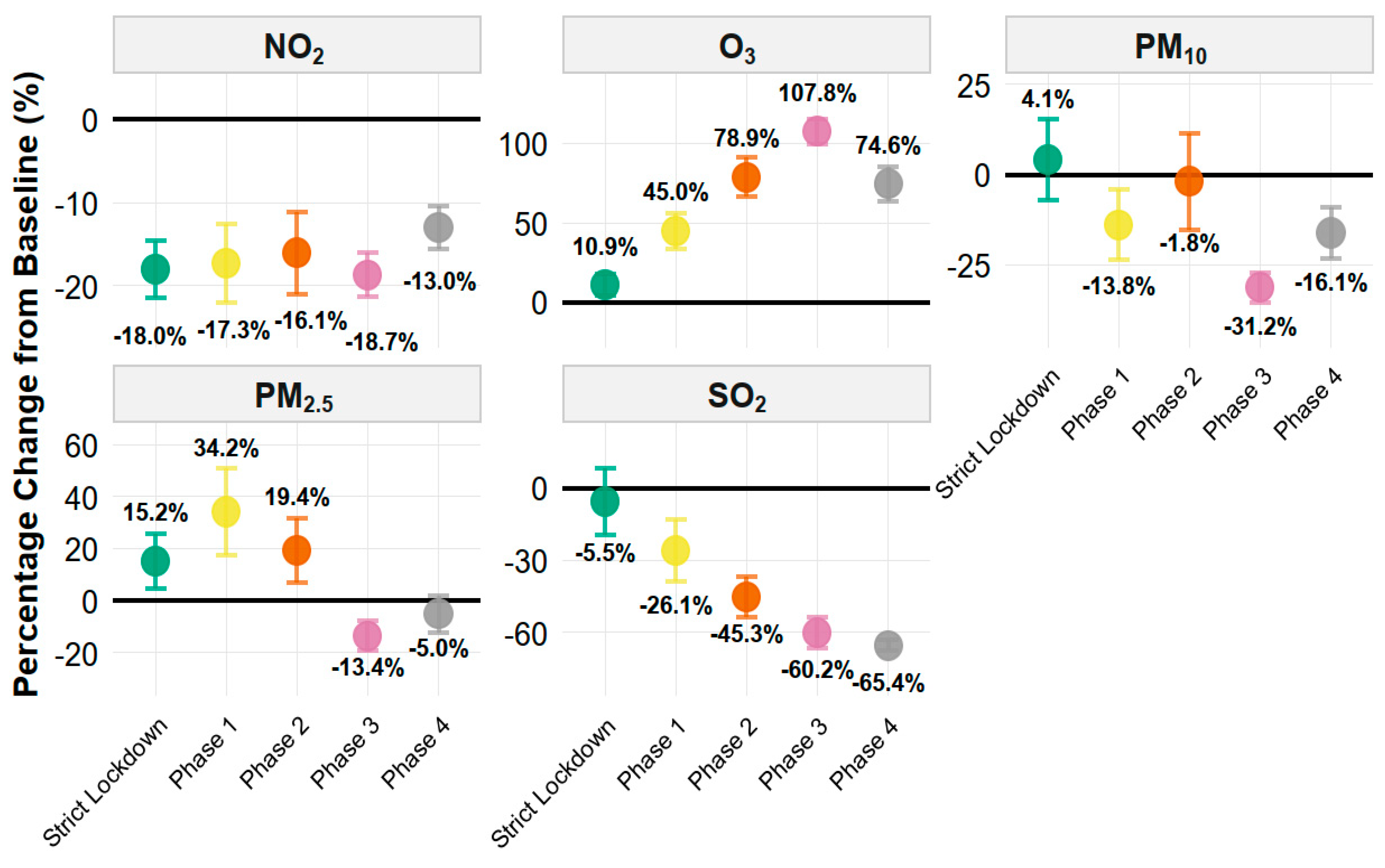

3.1. Air Pollutant Concentrations Across COVID-19 Pandemic Phases

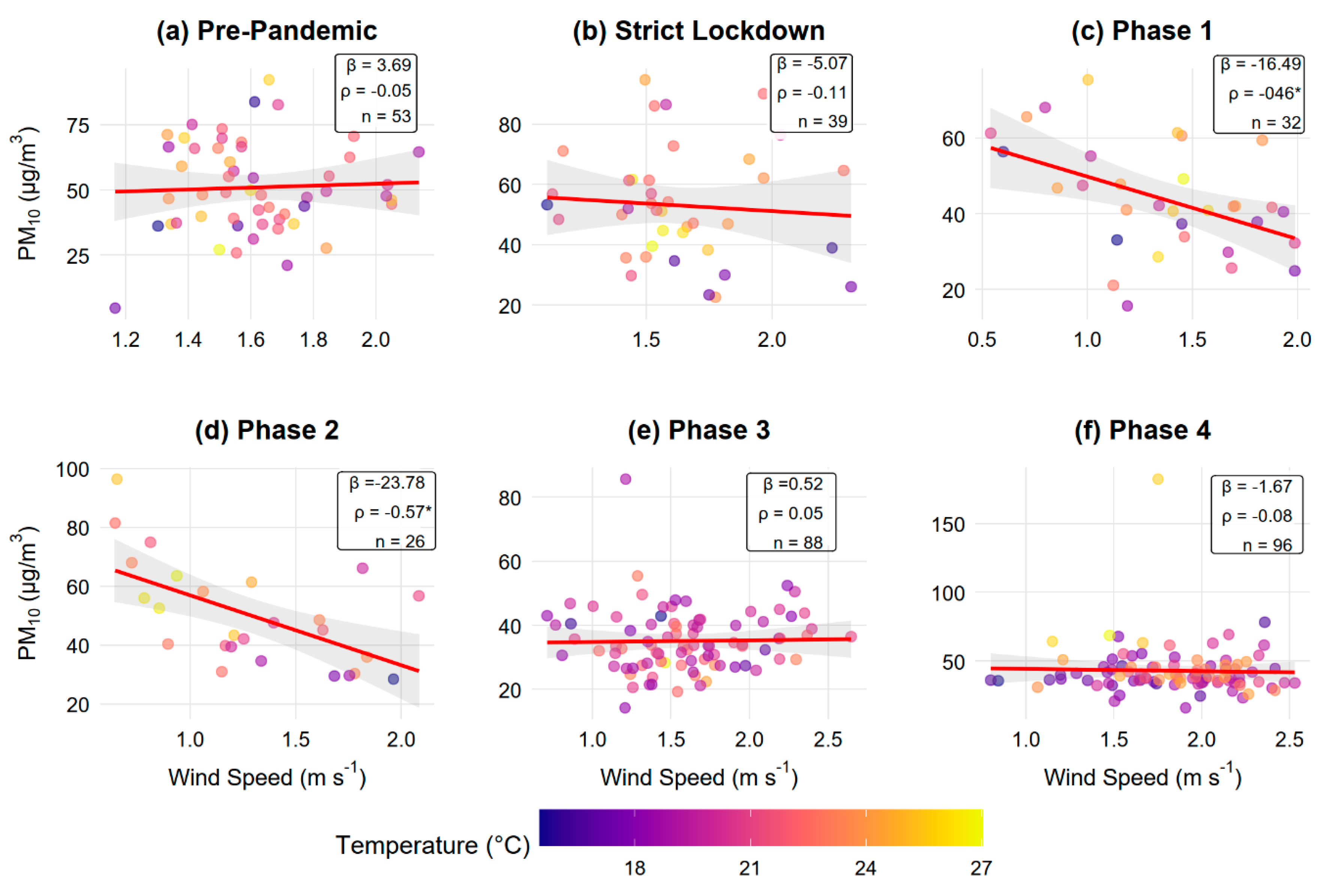

3.2. Meteorological Conditions and Pollutant–Meteorology Relationships

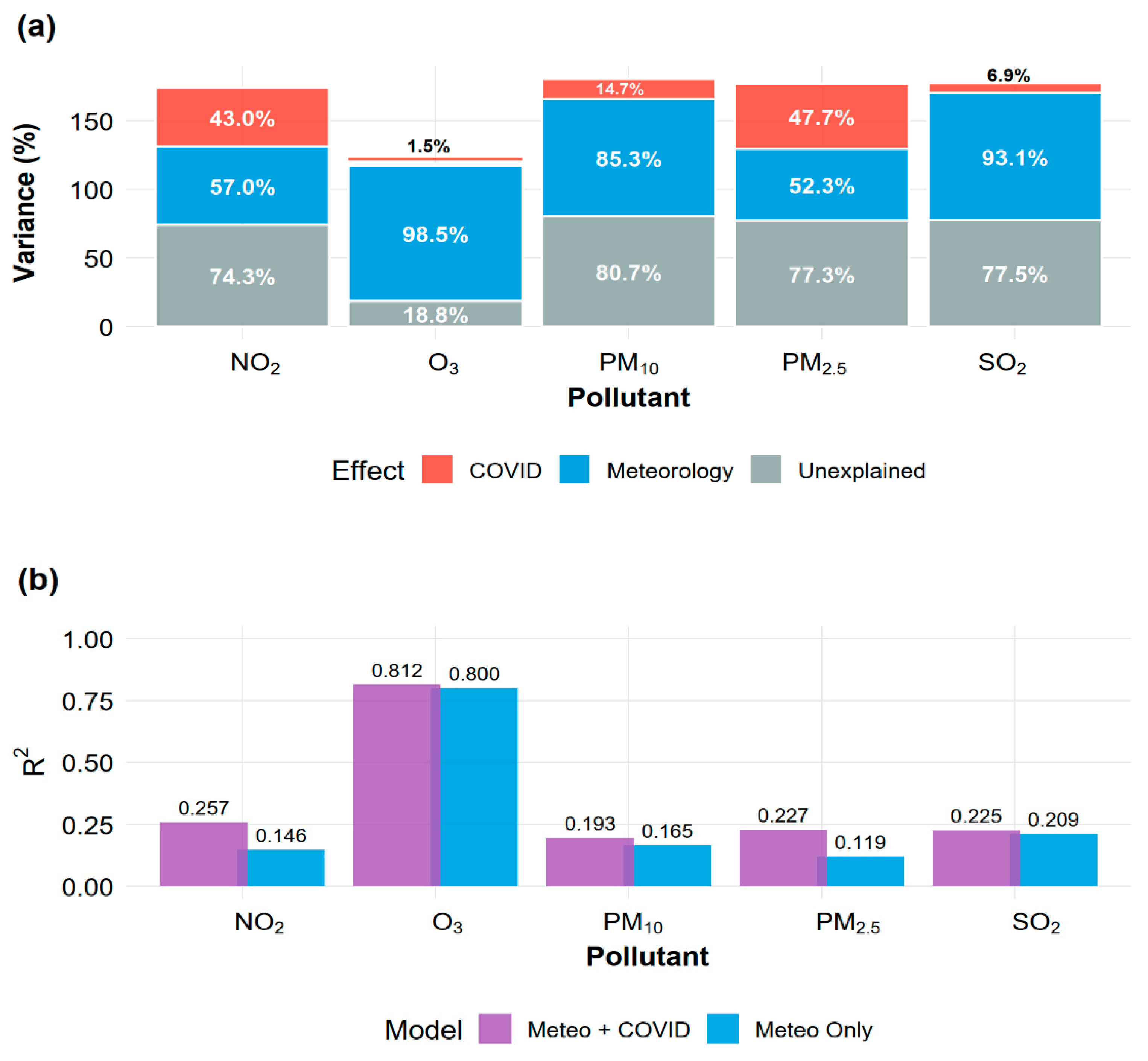

3.3. Relative Contributions of COVID-19 Restrictions and Meteorology

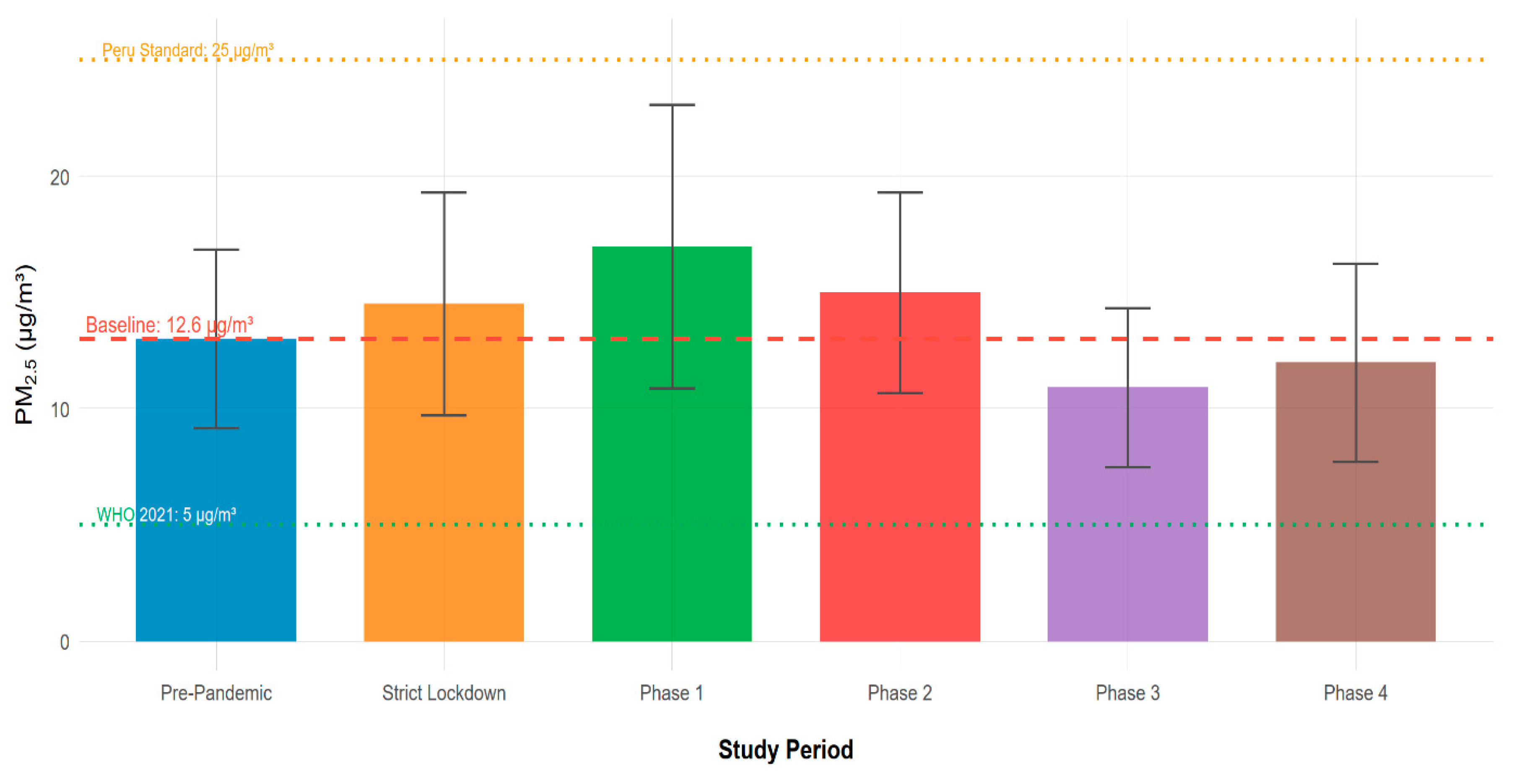

3.4. Health Impact Assessment of PM2.5 Changes

4. Discussion

4.1. Air Quality Responses to COVID-19 Measures in a Coastal Latin American City

4.2. Disentangling Restriction Measures and Meteorology: Pollutant-Specific Patterns

4.3. Health Relevance and Implications for Air Quality Management

4.4. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fang, T.; Di, Y.; Xu, Y.; Shen, N.; Fan, H.; Hou, S.; et al. Temporal trends of particulate matter pollution and its health burden, 1990–2021, with projections to 2036: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Front Public Health 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brauer, M.; Roth, G.A.; Aravkin, A.Y.; Zheng, P.; Abate, K.H.; Abate, Y.H.; et al. Global burden and strength of evidence for 88 risk factors in 204 countries and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet [Internet] 2024, 403, 2162–2203. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673624009334. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza-Cano, O.; Vázquez-Yañez, A.; Trujillo, X.; Huerta, M.; Ríos-Silva, M.; Lugo-Radillo, A.; et al. Cardiovascular disease burden linked to particulate matter pollution in Latin America and the Caribbean: Insights from GBD 2021 and socio-demographic index analysis. Public Health 2025, 238, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangones, S.C.; Cuéllar-Álvarez, Y.; Rojas-Roa, N.Y.; Osses, M. Addressing urban transport-related air pollution in Latin America: Insights and policy directions. Latin American Transport Studies 2025, 3, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020 [Internet]. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/speeches/item/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Hale, T.; Angrist, N.; Goldszmidt, R.; Kira, B.; Petherick, A.; Phillips, T.; et al. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). Nat Hum Behav. 2021, 5, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, M.; Alsafi, Z.; Sohrabi, C.; Kerwan, A.; Al-Jabir, A.; Iosifidis, C.; et al. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. In International Journal of Surgery; Elsevier Ltd, 2020; Vol. 78, pp. 185–193. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook, April 2020: The Great Lockdown [Internet]. Washington, DC, USA. 2020. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/publications/weo/issues/2020/04/14/weo-april-2020 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Le Quéré, C.; Jackson, R.B.; Jones, M.W.; Smith, A.J.P.; Abernethy, S.; Andrew, R.M.; et al. Temporary reduction in daily global CO2 emissions during the COVID-19 forced confinement. Nat Clim Chang. 2020, 10, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, Z.S.; Aunan, K.; Chowdhury, S.; Lelieveld, J. COVID-19 lockdowns cause global air pollution declines. The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences [Internet] 2020, 117. Available online: https://www.pnas.org. [CrossRef]

- Ravindra, K.; Singh, T.; Vardhan, S.; Shrivastava, A.; Singh, S.; Kumar, P.; et al. COVID-19 pandemic: What can we learn for better air quality and human health? In Journal of Infection and Public Health; Elsevier Ltd, 2022; Vol. 15, pp. 187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Beloconi, A.; Probst-Hensch, N.M.; Vounatsou, P. Spatio-temporal modelling of changes in air pollution exposure associated to the COVID-19 lockdown measures across Europe. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addas, A.; Maghrabi, A. The impact of covid-19 lockdowns on air quality —a global review. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, K.; Mushtaq, S.; Bao, Y.; Saifullah Bibi, S.; Yaseen, M.; et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on air pollution: a global research framework, challenges, and future perspectives. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 29, 52618–52634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gama, C.; Relvas, H.; Lopes, M.; Monteiro, A. The impact of COVID-19 on air quality levels in Portugal: A way to assess traffic contribution. Environ Res. 2021, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.; Toshniwal, D. Impact of lockdown on air quality over major cities across the globe during COVID-19 pandemic. Urban Clim. 2020, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, J.D.; Ebisu, K. Changes in U.S. air pollution during the COVID-19 pandemic. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Tartarini, F. Changes in air quality during the COVID-19 lockdown in singapore and associations with human mobility trends. Aerosol Air Qual Res. 2020, 20, 1748–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siciliano, B.; Dantas, G.; da Silva, C.M.; Arbilla, G. Increased ozone levels during the COVID-19 lockdown: Analysis for the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, G.; Pan, Y.; Tanaka, T. The short-term impacts of COVID-19 lockdown on urban air pollution in China. Nat Sustain. 2020, 3, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wang, M.; Zheng, M. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on global air quality and health. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, S.; Pal, S.; Ghosh, K.G. Effect of lockdown amid COVID-19 pandemic on air quality of the megacity Delhi, India. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, Z.S.; Aunan, K.; Chowdhury, S.; Lelieveld, J. Air pollution declines during COVID-19 lockdowns mitigate the global health burden. Environ Res. 2021, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Song, C.; Liu, B.; Lu, G.; Xu, J.; Van Vu, T.; et al. Abrupt but smaller than expected changes in surface air quality attributable to COVID-19 lockdowns [Internet]. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7. Available online: https://www.science.org. [CrossRef]

- Petetin, H.; Bowdalo, D.; Soret, A.; Guevara, M.; Jorba, O.; Serradell, K.; et al. Meteorology-normalized impact of the COVID-19 lockdown upon NO2 pollution in Spain. Atmos Chem Phys. 2020, 20, 11119–11141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Ding, A.; Gao, J.; Zheng, B.; Zhou, D.; Qi, X.; et al. Enhanced secondary pollution offset reduction of primary emissions during COVID-19 lockdown in China. Natl Sci Rev. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collivignarelli, M.C.; Abbà, A.; Bertanza, G.; Pedrazzani, R.; Ricciardi, P.; Carnevale Miino, M. Lockdown for CoViD-2019 in Milan: What are the effects on air quality? Science of the Total Environment 2020, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Chen, K.; Zhu, S.; Wang, P.; Zhang, H. Severe air pollution events not avoided by reduced anthropogenic activities during COVID-19 outbreak. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2020, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.W.A.; Chien, L.C.; Li, Y.; Lin, G. Nonuniform impacts of COVID-19 lockdown on air quality over the United States. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoor, A.; Chen, X.; Farooq, T.H.; Shahzad, U.; Ashraf, F.; Rehman, A.; et al. Fluctuations in environmental pollutants and air quality during the lockdown in the USA and China: two sides of COVID-19 pandemic. Air Qual Atmos Health 2020, 13, 1335–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara, M.; Jorba, O.; Soret, A.; Petetin, H.; Bowdalo, D.; Serradell, K.; et al. Time-resolved emission reductions for atmospheric chemistry modelling in Europe during the COVID-19 lockdowns. Atmos Chem Phys. 2021, 21, 773–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wang, Y.; Shang, Y.; Song, X.; Zhang, R.; Wang, Y.; et al. Contrasting the effect of aerosol properties on the planetary boundary layer height in Beijing and Nanjing. Atmos Environ. 2023, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Zhao, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C. Do meteorological variables impact air quality differently across urbanization gradients? A case study of Kaohsiung, Taiwan, China. Heliyon 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Tian, H.; Luo, L.; Liu, S.; Bai, X.; Zhao, H.; et al. Meteorology-normalized variations of air quality during the COVID-19 lockdown in three Chinese megacities. Atmos Pollut Res. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Zheng, H.; Ding, D.; Wang, S. A comparison of meteorological normalization of PM2.5 by multiple linear regression, general additive model, and random forest methods. Atmos Environ. 2024, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.J.; Yeganeh, A.; Chia, M.Y.; Shiu, H.Y.; Ooi, M.C.G.; Chang, J.H.W.; et al. Quantification of COVID-19 impacts on NO2 and O3: Systematic model selection and hyperparameter optimization on AI-based meteorological-normalization methods. Atmos Environ. 2023, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicard, P.; De Marco, A.; Agathokleous, E.; Feng, Z.; Xu, X.; Paoletti, E.; et al. Amplified ozone pollution in cities during the COVID-19 lockdown. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grange, S.K.; Lee, J.D.; Drysdale, W.S.; Lewis, A.C.; Hueglin, C.; Emmenegger, L.; et al. COVID-19 lockdowns highlight a risk of increasing ozone pollution in European urban areas. Atmos Chem Phys. 2021, 21, 4169–4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seinfeld, J.H.; Pandis, S.N. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: From Air Pollution to Climate Change, 3rd ed.; Wiley (John Wiley & Sons): Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Le, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Yang, J.; Yung, Y.L.; Li, G.; et al. Unexpected air pollution with marked emission reductions during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Science (1979) [Internet] 2020, 702–706. Available online: https://www.science.org. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, N.; Wang, G.; Li, G.; Lang, J.; Zhang, H. Air pollution episodes during the COVID-19 outbreak in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region of China: An insight into the transport pathways and source distribution. Environmental Pollution 2020, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, J.H.; Heald, C.L.; Cappa, C.D.; Farmer, D.K.; Fry, J.L.; Murphy, J.G.; et al. The complex chemical effects of COVID-19 shutdowns on air quality. In Nature Chemistry; Nature Research, 2020; Vol. 12, pp. 777–779. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, J.P.; Urdanivia, F.R.; Garay, R.A.; García, A.J.; Enciso, C.; Medina, E.A.; et al. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic control measures on air pollution in Lima metropolitan area, Peru in South America. Air Qual Atmos Health 2021, 14, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, A. R; Catalán, F; Urdanivia, FR; Rojas, JP; Manzano, CA; Seguel, R.; et al. Air pollution and COVID-19 lockdown in a large South American city: Santiago Metropolitan Area, Chile. Urban Clim. 2021, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volke, M.I.; Abarca-del-Rio, R.; Ulloa-Tesser, C. Impact of mobility restrictions on NO2 concentrations in key Latin American cities during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Urban Clim. 2023, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Melgarejo, M.; Reyes-Figueroa, A.D.; Gassó-Domingo, S.; Güereca, L.P. Analysis of empirical methods for the quantification of N2O emissions in wastewater treatment plants: Comparison of emission results obtained from the IPCC Tier 1 methodology and the methodologies that integrate operational data. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Urrego, D.; Rodríguez-Urrego, L. Air quality during the COVID-19: PM2.5 analysis in the 50 most polluted capital cities in the world. In Environmental Pollution; Elsevier Ltd, 2020; Vol. 266. [Google Scholar]

- Otmani, A.; Benchrif, A.; Tahri, M.; Bounakhla, M.; Chakir, E.M.; El Bouch, M.; et al. Impact of Covid-19 lockdown on PM10, SO2 and NO2 concentrations in Salé City (Morocco). Science of the Total Environment 2020, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, P.K.; Collins, D.B.; Grassian, V.H.; Prather, K.A.; Bates, T.S. Chemistry and Related Properties of Freshly Emitted Sea Spray Aerosol. In Chemical Reviews; American Chemical Society, 2015; Vol. 115, pp. 4383–4399. [Google Scholar]

- O’Dowd, C.D.; De Leeuw, G. Marine aerosol production: A review of the current knowledge. Vol. 365, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. Royal Society; 2007. p. 1753–1774.

- Duan, Y.; Wang, M.; Shen, Y.; Yi, M.; Fu, Q.; Chen, J.; et al. Influence of ship emissions on PM2.5 in Shanghai: From COVID19 to OMICRON22 lockdown episodes. Atmos Environ. 2023, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aas, W.; Fagerli, H.; Alastuey, A.; Cavalli, F.; Degorska, A.; Feigenspan, S.; et al. Trends in Air Pollution in Europe, 2000–2019. Aerosol Air Qual Res. 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Xu, X.; Liao, D.; Zheng, R.; Ji, X.; Chen, Y.; et al. Source apportionment of PM2.5 and sulfate formation during the COVID-19 lockdown in a coastal city of southeast China. Environmental Pollution 2021, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio Durán, R.E.; Cortez-Huerta, M.; Sosa Echeverría, R.; Fuentes García, G.; César Valdez, E.; Kahl, J.D.W. Random Forest approach to air quality assessment for port emissions in a coastal area in the Gulf of Mexico. Mar Pollut Bull. 2026, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Kong, Q.; Lan, Y.; Sng, J.; Yu, L.E. Refined Sea Salt Markers for Coastal Cities Facilitating Quantification of Aerosol Aging and PM2.5 Apportionment. Environ Sci Technol. 2024, 58, 8432–8443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindra, K.; Stranger, M.; Van Grieken, R. Chemical characterization and multivariate analysis of atmospheric PM 2.5 particles. J Atmos Chem. 2008, 59, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M.F.; Ma, B.; Bilal Komal, B.; Bashir, M.A.; Tan, D.; et al. Correlation between climate indicators and COVID-19 pandemic in New York, USA. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, R.; Chen, H.; Szyszkowicz, M.; Fann, N.; Hubbell, B.; Pope, C.A.; et al. Global estimates of mortality associated with longterm exposure to outdoor fine particulate matter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, 9592–9597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zanobetti, A.; Wang, Y.; Koutrakis, P.; Choirat, C.; et al. Air Pollution and Mortality in the Medicare Population. New England Journal of Medicine 2017, 376, 2513–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet [Internet] 2020, 396, 1135–1159. Available online: www.thelancet.com.

- Fann, N.; Lamson, A.D.; Anenberg, S.C.; Wesson, K.; Risley, D.; Hubbell, B.J. Estimating the National Public Health Burden Associated with Exposure to Ambient PM2.5 and Ozone. Risk Analysis 2012, 32, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.J.; Brauer, M.; Burnett, R.; Anderson, H.R.; Frostad, J.; Estep, K.; et al. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. The Lancet 2017, 389, 1907–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Nobile, F.; Marb, A.; Dubrow, R.; Kinney, P.L.; Peters, A.; et al. Air pollution changes due to COVID-19 lockdowns and attributable mortality changes in four countries. Environ Int. 2024, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Du, H.; Lin, Z.; Chen, X.; Chen, Z.; Tu, Q. Green recovery or pollution rebound? Evidence from air pollution of China in the post-COVID-19 era. J Environ Manage 2022, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, E.; Michalski, G.; Welp, L.; Larrea Valdivia, A.E.; Reyes Larico, J.; Salcedo Peña, J.; et al. Mineral dust and fossil fuel combustion dominate sources of aerosol sulfate in urban Peru identified by sulfur stable isotopes and water-soluble ions. Atmos Environ. 2021, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presidencia del Consejo de Ministros. Decreto Supremo N° 044-2020-PCM que declara Estado de Emergencia Nacional por las graves circunstancias que afectan la vida de la Nación a consecuencia del brote del COVID-19 [Internet]. Lima, Peru, 2020. Available online: https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/566448/DS044-PCM_1864948-2.pdf?v=1584330685 (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Bauwens, M.; Compernolle, S.; Stavrakou, T.; Müller, J.F.; van Gent, J.; Eskes, H.; et al. Impact of Coronavirus Outbreak on NO2 Pollution Assessed Using TROPOMI and OMI Observations. Geophys Res Lett. 2020, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobías, A.; Carnerero, C.; Reche, C.; Massagué, J.; Via, M.; Minguillón, M.C.; et al. Changes in air quality during the lockdown in Barcelona (Spain) one month into the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Tyagi, B. Transformation of air quality over a coastal tropical station chennai during covid-19 lockdown in India. Aerosol Air Qual Res. 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopke, P.K. Review of receptor modeling methods for source apportionment. Vol. 66, Journal of the Air and Waste Management Association. Taylor and Francis Inc.; 2016. p. 237–259.

- Wu, Q.; Li, T.; Zhang, S.; Fu, J.; Seyler, B.C.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Evaluation of NOx emissions before, during, and after the COVID-19 lockdowns in China: A comparison of meteorological normalization methods. Atmos Environ. 2022, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (INEI). Censos Nacionales 2017: XII de Población, VII de Vivienda y III de Comunidades Indígenas [Internet]. Lima. 2018. Available online: https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1539/libro.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Boon, R.G.J.; Alexaki, A.; Becerra, E.H. The Ilo Clean Air Project: a local response to industrial pollution control in Peru. Environ Urban [Internet] 2001, 13. Available online: http://www.ihs.nl. [CrossRef]

- WHO global air quality guidelines. Particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10) ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide [Internet]. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240034228 (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Wijnands, J.S.; Nice, K.A.; Seneviratne, S.; Thompson, J.; Stevenson, M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on air pollution: A global assessment using machine learning techniques. Atmos Pollut Res. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [Internet]; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.gnu.org/copyleft/gpl.html.

- Cleveland, W.S.; Devlin, S.J. Locally weighted regression: An approach to regression analysis by local fitting. J Am Stat Assoc. 1988, 83, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, Third Edition. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, Third Edition [Internet]. 2013, pp. 1–704. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9780203774441/applied-multiple-regression-correlation-analysis-behavioral-sciences-jacob-cohen-patricia-cohen-stephen-west-leona-aiken (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- James Gareth Witten Daniela Hastie Trevor Tibshirani Robert An introduction to statistical learning : with applications in, R. Springer : Springer Science+Business Media; 2017. 426 p.

- Kutner, MH.; Chris, Nachtsheim; John, Neter; William, Li. Applied linear statistical models; McGraw-Hill Irwin, 2005; p. 1396 p. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, J.M. Hastie Travor Statistical models in, S; Chapman & Hall, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- White, H. A HETEROSKEDASTICITY CONSISTENT COVARIANCE MATRIX ESTIMATOR AND A DIRECT TEST FOR HETEROSKEDASTICITY. Econometrica 1980, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, G.; Finch, S. Inference by eye confidence intervals and how to read pictures of data. American Psychologist 2005, 60, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, A.; Wiener, M. Classification and Regression by randomForest. R News [Internet] 2002, 2. Available online: http://www.stat.berkeley.edu/.

- Bickel, P.; Diggle, P.; Fienberg, S.; Gather, U.; Olkin, I.; Zeger, S. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction [Internet], 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Available online: http://www.springer.com/series/692.

- Sandve, G.K.; Nekrutenko, A.; Taylor, J.; Hovig, E. Ten Simple Rules for Reproducible Computational Research. In PLoS Computational Biology; Public Library of Science, 2013; Vol. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Louppe, G.; Wehenkel, L.; Sutera, A.; Geurts, P. Understanding variable importances in forests of randomized trees. In 27th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2013) [Internet]; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, 2013; pp. 431–439. (accessed on 11 September 2025). [Google Scholar]

- Apte, J.S.; Marshall, J.D.; Cohen, A.J.; Brauer, M. Addressing Global Mortality from Ambient PM2.5. Environ Sci Technol. 2015, 49, 8057–8066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khomenko, S.; Cirach, M.; Pereira-Barboza, E.; Mueller, N.; Barrera-Gómez, J.; Rojas-Rueda, D.; et al. Premature mortality due to air pollution in European cities: a health impact assessment. Lancet Planet Health 2021, 5, e121–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Salud del Perú (MINSA). Análisis de Situación de Salud del Perú 2019 [Internet]. Centro Nacional de Epidemiología, Prevención y Control de Enfermedades: Lima, Peru, 2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.dge.gob.pe/portalnuevo/publicaciones/analisis-de-situacion-de-salud/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Krewski, D.; Jerrett, M.; Burnett, R.T.; Ma, R.; Hughes, E.; Shi, Y.; et al. Extended Follow-Up and Spatial Analysis of the American Cancer Society Study Linking Particulate Air Pollution and Mortality; Health Effects Institute: Boston, MA, 2009; Volume 140, pp. 5–114. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, C.A.; Dockery, D.W. Health effects of fine particulate air pollution: Lines that connect. J Air Waste Manage Assoc. 2006, 56, 709–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellano, P.; Reynoso, J.; Quaranta, N.; Bardach, A.; Ciapponi, A. Short-term exposure to particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and ozone (O3) and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Vol. 142, Environment International. Elsevier Ltd; 2020.

- Dockery, D.W.; Pope, C.A.; Xu, X.; Spengler John Ware, J.; Fay, M.; et al. AN ASSOCIATION BETWEEN AIR POLLUTION AND MORTALITY IN SIX U.S. CITIES. N Engl J Med. 1993, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickham, Hadley. ggplot2 Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis [Internet], 2nd ed.; Houston, Texas, USA; Available online: http://www.springer.com/series/6991.

- Garnier, S; Ross, N; Rudis, boB; Filipovic-Pierucci, A; Galili, T; timelyportfolio; et al. sjmgarnier/viridis: CRAN release v0.6.3. 2025. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/7890878 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.; François, R.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grolemund, G.; Wickham, H. Journal of Statistical Software Dates and Times Made Easy with lubridate [Internet]. 2011, Vol. 40. Available online: http://www.jstatsoft.org/.

- Carslaw, D.C.; Ropkins, K. openair — An R package for air quality data analysis. Environmental Modelling & Software 2012, 27–28, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, G.M.; Feinn, R. Using Effect Size—or Why the P Value Is Not Enough. J Grad Med Educ. 2012, 4, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkatzelis, G.I.; Gilman, J.B.; Brown, S.S.; Eskes, H.; Gomes, A.R.; Lange, A.C.; et al. The global impacts of COVID-19 lockdowns on urban air pollution: A critical review and recommendations; University of California Press, 2021; Vol. 9, p. Elementa. [Google Scholar]

- Atiaga, O.; Páez, F.; Jácome, W.; Castro, R.; Collaguazo, E.; Nunes, L.M. COVID-19 pandemic impacted differently air quality in Latin American cities. Air Qual Atmos Health 2025, 18, 1919–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querol, X.; Massagué, J.; Alastuey, A.; Moreno, T.; Gangoiti, G.; Mantilla, E.; et al. Lessons from the COVID-19 air pollution decrease in Spain: Now what? Science of the Total Environment 2021, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velayarce, D.; Bustos, Q.; García, M.P.; Timaná, C.; Carbajal, R.; Salvatierra, N.; et al. Air Quality Analysis in Lima, Peru Using the NO2 Levels during the COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown. Atmosphere (Basel) 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Peláez, L.M.; Santos, J.M.; de Almeida Albuquerque, T.T.; Reis, N.C.; Andreão, W.L.; de Fátima Andrade, M. Air quality status and trends over large cities in South America. Environ Sci Policy 2020, 114, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Tang, Y.; Lu, M.; Yang, X.; Shi, J.; Cai, Z.; et al. Influence of coastal planetary boundary layer on PM2.5 with unmanned aerial vehicle observation. Atmos Res. 2023, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aswini, A.R.; Hegde, P. Impact assessment of continental and marine air-mass on size-resolved aerosol chemical composition over coastal atmosphere: Significant organic contribution in coarse mode fraction. Atmos Res. 2021, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodonos, A.; Awad, Y.A.; Schwartz, J. The concentration-response between long-term PM2.5 exposure and mortality; A meta-regression approach. Environ Res. 2018, 166, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Chu, C. Assessing the health impacts attributable to PM2.5 and ozone pollution in 338 Chinese cities from 2015 to 2020. Environmental Pollution 2021, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.; Davy, P.; Tollemache, C.; Talbot, N.; Salmond, J.; Williams, D.E. Evaluating the efficacy of targeted traffic management interventions: A novel methodology for determining the composition of particulate matter in urban air pollution hotspots. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasopolos, A.T.; Hopke, P.K.; Sofowote, U.M.; Mooibroek, D.; Zhang, J.J.Y.; Rouleau, M.; et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of low-sulphur marine fuel regulations at improving urban ambient PM2.5 air quality: Source apportionment of PM2.5 at Canadian Atlantic and Pacific coast cities with implementation of the North American Emissions Control Area. Science of the Total Environment 2023, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez, O.; Gutiérrez-Ulloa, C.; Zarate, L.; Carrión, A.M.; Hernandez Guzman, A.; de la Rosa, J. Impact of urbanization and industrialization on PM10 in municipalities near megacities: A case study from an Andean Region, Latin America. Urban Clim. 2025, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pollutant | Period | M (SD) | Mdn | Range | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM₁₀ | Pre-Pandemic | 50.93 (17.38) | 48.11 | 4.56–92.28 | 53 |

| PM₁₀ | Strict Lockdown | 53.04 (18.31) | 51.43 | 22.57–94.73 | 39 |

| PM₁₀ | Phase 1 | 43.90 (14.41) | 41.79 | 15.66–75.32 | 32 |

| PM₁₀ | Phase 2 | 50.00 (17.60) | 46.33 | 28.40–96.36 | 26 |

| PM₁₀ | Phase 3 | 35.07 (9.90) | 33.63 | 14.18–85.62 | 88 |

| PM₁₀ | Phase 4 | 42.74 (18.18) | 38.43 | 15.74–182.48 | 96 |

| PM2.5 | Pre-Pandemic | 12.60 (4.36) | 12.39 | 0.71–21.71 | 53 |

| PM2.5 | Strict Lockdown | 14.51 (4.70) | 14.23 | 7.33–28.42 | 49 |

| PM2.5 | Phase 1 | 16.91 (6.14) | 16.57 | 4.58–33.65 | 32 |

| PM2.5 | Phase 2 | 15.04 (4.06) | 14.61 | 7.74–23.96 | 26 |

| PM2.5 | Phase 3 | 10.91 (3.44) | 10.31 | 4.19–23.72 | 88 |

| PM2.5 | Phase 4 | 11.96 (4.40) | 11.48 | 5.08–44.13 | 96 |

| NO₂ | Pre-Pandemic | 5.81 (1.00) | 5.67 | 4.31–10.02 | 56 |

| NO₂ | Strict Lockdown | 4.77 (0.71) | 4.61 | 3.64–7.34 | 49 |

| NO₂ | Phase 1 | 4.81 (0.78) | 4.56 | 3.58–6.91 | 32 |

| NO₂ | Phase 2 | 4.88 (0.74) | 4.90 | 3.86–6.82 | 26 |

| NO₂ | Phase 3 | 4.73 (0.74) | 4.47 | 3.72–6.96 | 88 |

| NO₂ | Phase 4 | 5.06 (0.75) | 4.93 | 3.49–7.91 | 96 |

| O₃ | Pre-Pandemic | 14.59 (4.23) | 15.31 | 7.21–22.19 | 56 |

| O₃ | Strict Lockdown | 16.18 (3.38) | 15.44 | 12.03–26.45 | 49 |

| O₃ | Phase 1 | 21.15 (4.79) | 19.70 | 14.23–31.69 | 32 |

| O₃ | Phase 2 | 26.09 (4.75) | 27.25 | 15.98–33.09 | 26 |

| O₃ | Phase 3 | 30.31 (5.47) | 30.37 | 13.96–43.20 | 88 |

| O₃ | Phase 4 | 25.47 (3.56) | 25.80 | 19.02–32.40 | 19 |

| SO₂ | Pre-Pandemic | 25.57 (20.59) | 19.05 | 7.91–129.88 | 56 |

| SO₂ | Strict Lockdown | 24.17 (12.74) | 20.67 | 7.71–66.55 | 49 |

| SO₂ | Phase 1 | 18.90 (9.46) | 17.78 | 7.24–40.18 | 32 |

| SO₂ | Phase 2 | 14.00 (5.64) | 12.41 | 7.68–30.54 | 26 |

| SO₂ | Phase 3 | 10.18 (7.41) | 8.83 | 7.10–55.30 | 79 |

| SO₂ | Phase 4 | 8.85 (0.83) | 8.73 | 8.17–10.91 | 9 |

| Pollutant | n | R² | R² Meteo | R² COVID | % Meteo | % COVID | F (5, df₂) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM₁₀ | 334 | 0.193 | 0.165 | 0.029 | 85.3 | 14.7 | 2.30 | 0.045 |

| PM2.5 | 344 | 0.227 | 0.119 | 0.108 | 52.3 | 47.7 | 9.40 | 0.001 |

| NO₂ | 347 | 0.257 | 0.146 | 0.110 | 57.0 | 43.0 | 10.02 | 0.001 |

| O₃ | 271 | 0.812 | 0.800 | 0.013 | 98.5 | 1.5 | 3.49 | 0.005 |

| SO₂ | 251 | 0.225 | 0.209 | 0.015 | 93.1 | 6.9 | 0.96 | 0.440 |

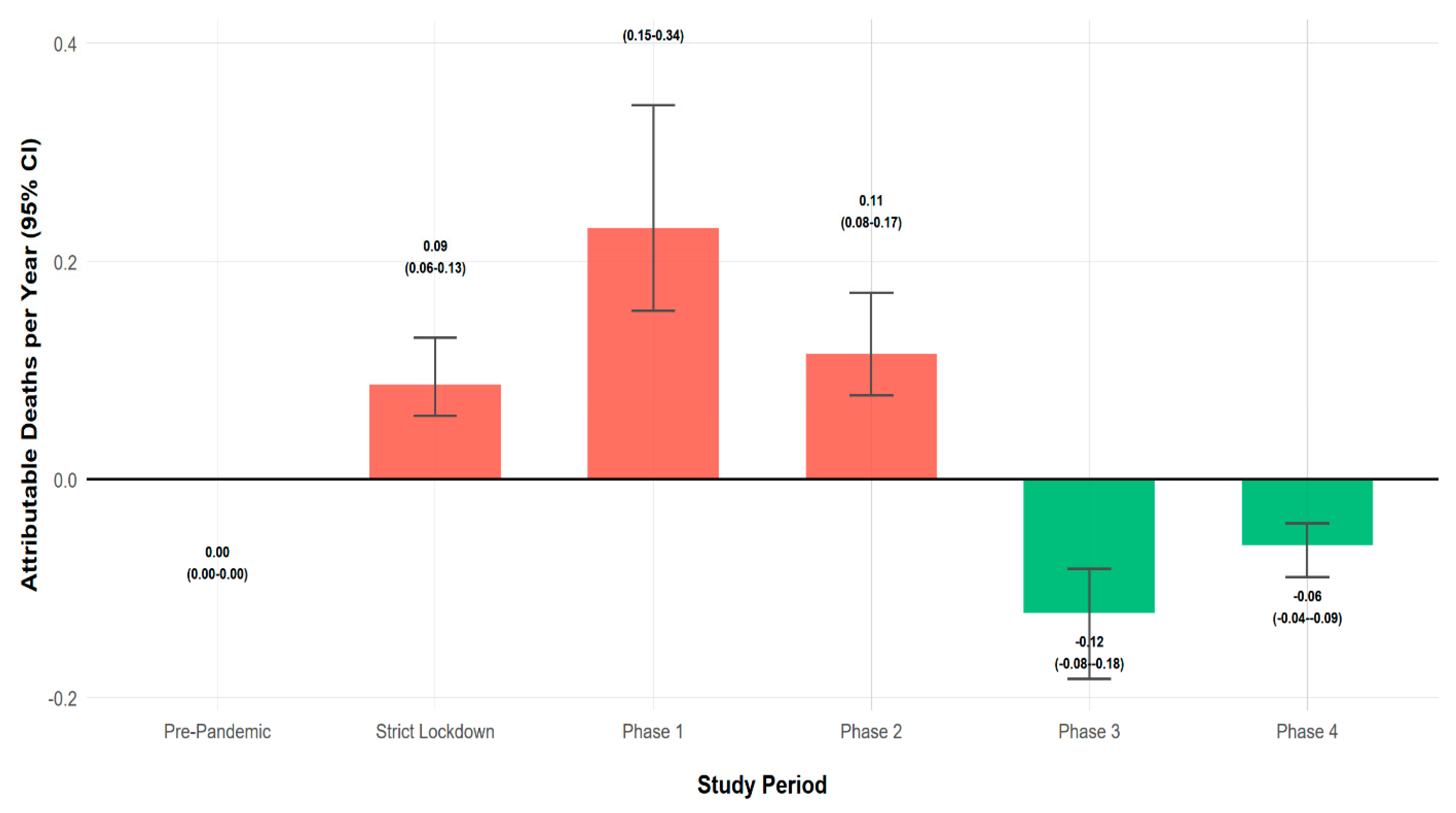

| Period | PM2.5 (μg/m³) | Δ PM2.5 (µg/m³) | % Change | RR (95% CI) |

Deaths (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Pandemic | 12.60 ± 4.36 | 0 | 0 | 1.000 (1.000-1.000) | 0.00 (0.00-0.00) |

| Strict Lockdown | 14.51 ± 4.70 | 1.91 | 15.2 | 1.001 (1.001-1.001) | 0.09 (0.06-0.13) |

| Phase 1 | 16.91 ± 6.14 | 4.31 | 34.2 | 1.003 (1.002-1.003) | 0.23 (0.15-0.34) |

| Phase 2 | 15.04 ± 4.06 | 2.45 | 19.4 | 1.001 (1.001-1.002) | 0.11 (0.08-0.17) |

| Phase 3 | 10.91 ± 3.44 | - 1.69 | -13.4 | 0.998 (0.999-0.998) | -0.12 (-0.08--0.18) |

| Phase 4 | 11.96 ± 4.40 | - 0.63 | -5.0 | 0.999 (0.999-0.999) | -0.06 (-0.04--0.09) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).