Submitted:

11 December 2025

Posted:

11 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

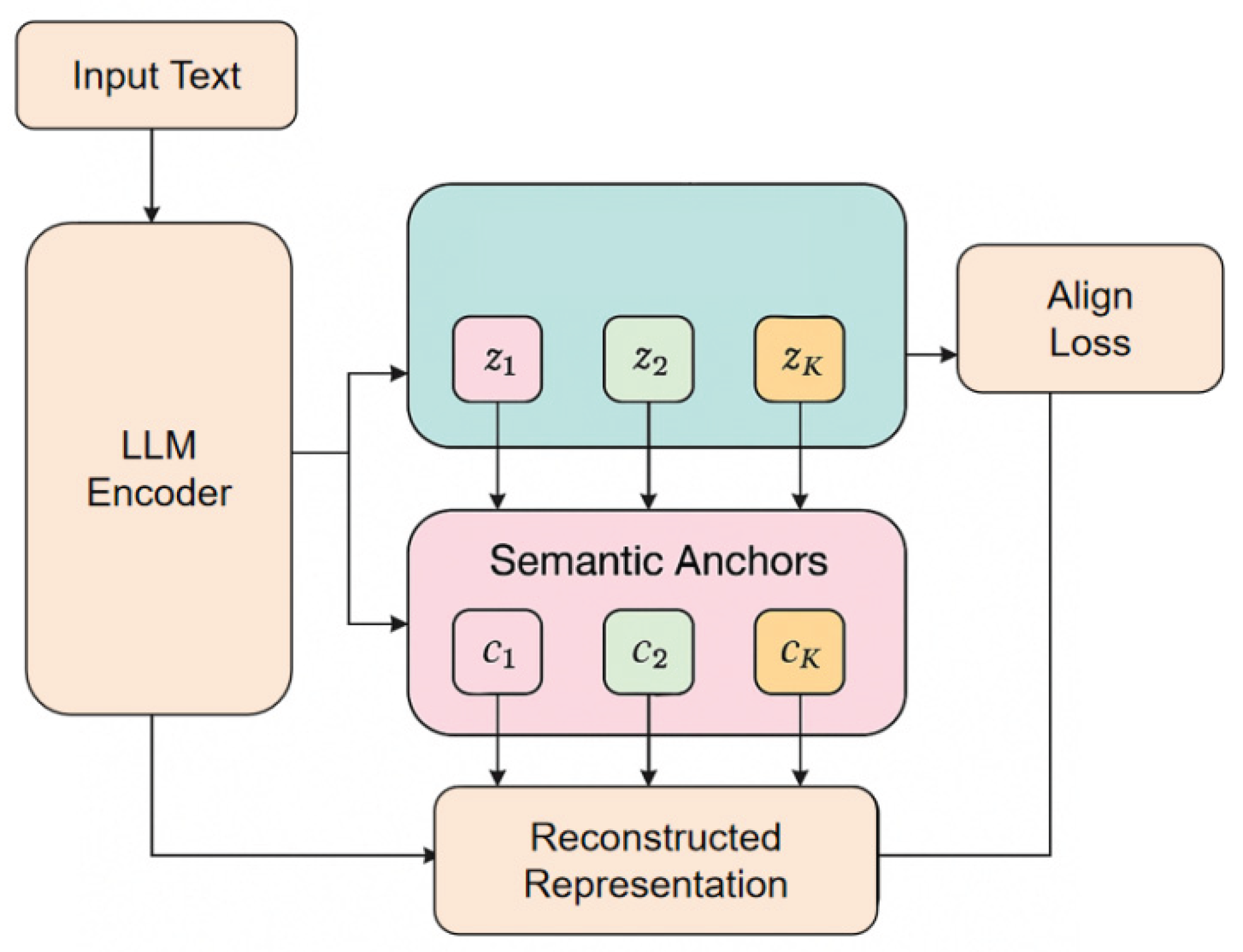

2. Proposed Framework

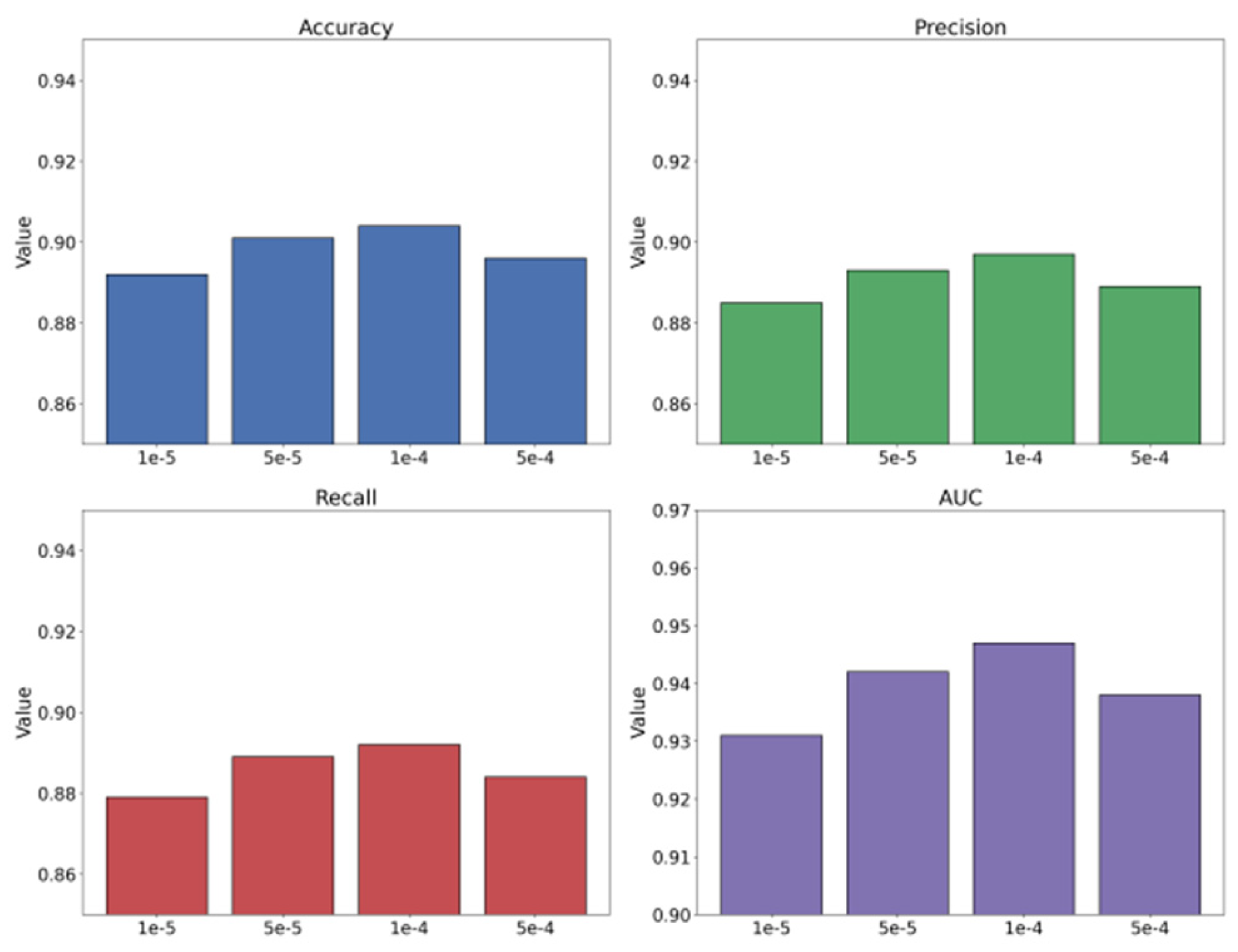

3. Experimental Analysis

3.1. Dataset

3.2. Experimental Results

4. Conclusions

References

- Zhong, Q.; Ding, L.; Liu, J.; et al. Knowledge graph augmented network towards multiview representation learning for aspect-based sentiment analysis. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2023, vol. 35(no. 10), 10098–10111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ding, L.; Zhong, Q.; et al. A contrastive cross-channel data augmentation framework for aspect-based sentiment analysis. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.07832. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Liu, W.; Wang, K. Research on sentiment analysis method of opinion mining based on multi-model fusion transfer learning. Journal of Big Data 2023, vol. 10(no. 1), 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhao, S.; Wang, X.; et al. Fine-grained disentangled representation learning for multimodal emotion recognition. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024 - 2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 2024; pp. 11051–11055. [Google Scholar]

- Su, X. Forecasting asset returns with structured text factors and dynamic time windows. Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods 2024, vol. 4(no. 6). [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Han, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, M.; Meng, R. Collaborative evolution of intelligent agents in large-scale microservice systems. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.20508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, G.; Liu, H.; Dai, L. Multi-agent reinforcement learning for adaptive resource orchestration in cloud-native clusters. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.10253. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Y.; Qi, N.; Deng, Y.; Xue, Z.; Gong, M.; Zhang, W. Autonomous resource management in microservice systems via reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Computer Information Science and Application Technology (CISAT), July 2025; pp. 991–995. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, R.; Lyu, J.; Li, J.; Nie, C.; Chiang, C. Dynamic Portfolio Optimization with Data-Aware Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning and Adaptive Risk Control. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, W. C.; Dai, L.; Xu, T. Machine Learning Approaches to Clinical Risk Prediction: Multi-Scale Temporal Alignment in Electronic Health Records. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2511.21561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Gadgil, S. U.; Gao, K.; Hu, Y.; Nie, C. Deep Learning Approach to Anomaly Detection in Enterprise ETL Processes with Autoencoders. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2511.00462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, N.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, F. Multi-Objective Adaptive Rate Limiting in Microservices Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2511.03279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Yang, Z.; Shi, H.; et al. SDRS: Sentiment-aware disentangled representation shifting for multimodal sentiment analysis. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, 2025. 2025.

- Song, X.; Liu, Y.; Luan, Y.; Guo, J.; Guo, X. Controllable Abstraction in Summary Generation for Large Language Models via Prompt Engineering. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.15436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Peng, C.; Deng, H.; Yin, S. Information-Constrained Retrieval for Scientific Literature via Large Language Model Agents. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, R.; Meng, R.; Lian, L.; Wang, H.; Quan, X. Fusion-based retrieval-augmented generation for complex question answering with LLMs. In Proceedings of the 2025 8th International Conference on Computer Information Science and Application Technology (CISAT), July 2025; pp. 116–120. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Qin, Y.; Xu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Guo, X.; Xu, W. Integrating Knowledge Graph Reasoning with Pretrained Language Models for Structured Anomaly Detection. 2025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Soni, S.; Chouhan, S. S.; Rathore, S. S. TextConvoNet: a convolutional neural network based architecture for text classification. Applied Intelligence 2023, vol. 53(no. 11), 14249–14268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Jin, W.; Del Ser, J.; et al. ChatAgri: Exploring potentials of ChatGPT on cross-linguistic agricultural text classification. Neurocomputing 2023, vol. 557, Article 126708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, A.; Rossi, L.; Prati, A. AEDA: An easier data augmentation technique for text classification. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.13230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhan, J.; et al. Text FCG: Fusing contextual information via graph learning for text classification. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, vol. 219, 119658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, J.; Chi, J.; et al. Set-CNN: A text convolutional neural network based on semantic extension for short text classification. Knowledge-Based Systems 2022, vol. 257, 109948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.; O'Connor, J.; Andreas, J.; et al. Promptboosting: Black-box text classification with ten forward passes. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, 2023; pp. 13309–13324. [Google Scholar]

| Method | Acc | Precision | Recall | AUC |

| TextConvoNet [18] | 0.812 | 0.805 | 0.798 | 0.854 |

| ChatAgri [19] | 0.826 | 0.821 | 0.817 | 0.868 |

| AEDA [20] | 0.834 | 0.829 | 0.824 | 0.879 |

| Text FCG [21] | 0.848 | 0.842 | 0.839 | 0.892 |

| Set-CNN [22] | 0.857 | 0.851 | 0.846 | 0.905 |

| Promptboosting [23] | 0.871 | 0.866 | 0.861 | 0.919 |

| Ours | 0.904 | 0.897 | 0.892 | 0.947 |

| Optimizer | Acc | Precision | Recall | AUC |

| AdaGrad | 0.861 | 0.854 | 0.849 | 0.904 |

| Adam | 0.883 | 0.876 | 0.872 | 0.928 |

| SGD | 0.847 | 0.838 | 0.833 | 0.892 |

| AdamW | 0.904 | 0.897 | 0.892 | 0.947 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).