Submitted:

10 December 2025

Posted:

12 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

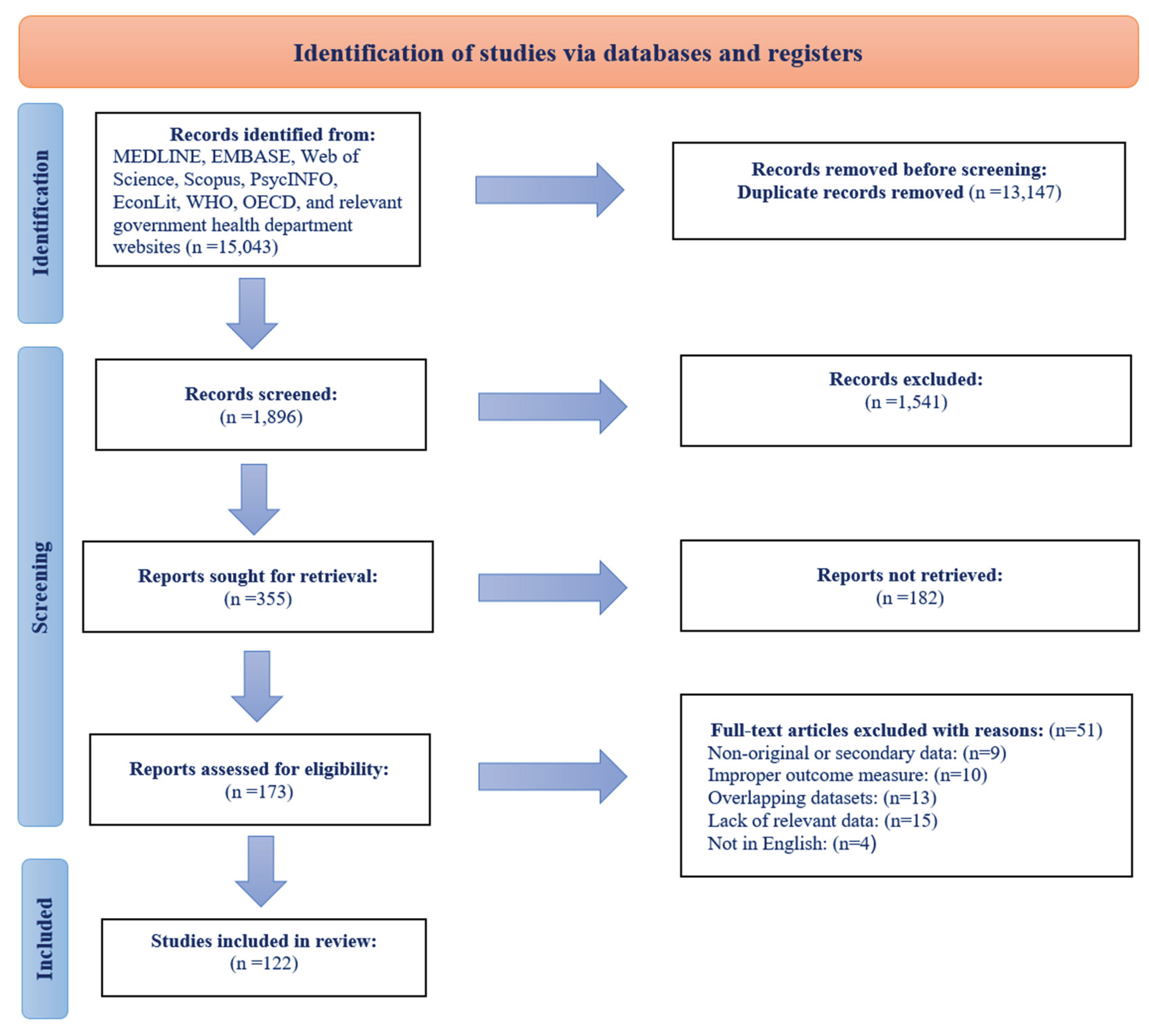

2. Methodology

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection Process

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Software and Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.2.1. Study Designs

3.2.2. Geographic Distribution of the Studies

3.2.3. Population/Participants

3.3. Key Topics and Exposures

3.3.1. Suicide Mortality

3.3.2. Suicidal Ideation, Attempts, and Self-Harm

3.3.3. Depression, Psychological Distress, and Poor Mental Health

3.3.4. Utilization of Mental Health Services and Medications

3.3.5. Other Mental and Behavioral Outcomes

3.3.6. Moderating and Protective Factors

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Funding

Ethics Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amiri, S. Unemployment associated with major depression disorder and depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2022a, 28, 2080–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amiri, S. Smoking and alcohol use in unemployed populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Addict. Dis. 2022b, 40, 254–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arinaminpathy, N.; Dye, C. Health in financial crises: economic recession and tuberculosis in Central and Eastern Europe. J. R. Soc. Interface 2010, 7, 1559–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ásgeirsdóttir, H.G.; Ásgeirsdóttir, T.L.; Nyberg, U.; Thorsteinsdottir, T.K.; Mogensen, B.; Matthiasson, P.; Lund, S.H.; Valdimarsdottir, U.A.; Hauksdóttir, A. Suicide attempts and self-harm during a dramatic national economic transition: a population-based study in Iceland. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, B.; Taylor-Robinson, D.; Scott-Samuel, A.; McKee, M.; Stuckler, D. Suicides associated with the 2008-10 economic recession in England: time trend analysis. Bmj 2012, 345, e5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berend, I.T. A restructured economy: From the oil crisis to the financial crisis, 1973--2009. 2012.

- Branas, C.C.; Kastanaki, A.E.; Michalodimitrakis, M.; Tzougas, J.; Kranioti, E.F.; Theodorakis, P.N.; Carr, B.G.; Wiebe, D.J. The impact of economic austerity and prosperity events on suicide in Greece: a 30-year interrupted time-series analysis. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e005619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, P.; Thomson, R.; Kopasker, D.; McCartney, G.; Meier, P.; Richiardi, M.; McKee, M.; Katikireddi, S.V. The public health implications of the cost-of-living crisis: outlining mechanisms and modelling consequences. Lancet Reg. Heal. 2023, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, R.; Goldman-Mellor, S.; Saxton, K.; Margerison-Zilko, C.; Subbaraman, M.; LeWinn, K.; Anderson, E. The health effects of economic decline. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2011, 32, 431–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-S.; Gunnell, D.; Sterne, J.A.C.; Lu, T.-H.; Cheng, A.T.A. Was the economic crisis 1997--1998 responsible for rising suicide rates in East/Southeast Asia? A time--trend analysis for Japan, Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Thailand. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 1322–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-S.; Stuckler, D.; Yip, P.; Gunnell, D. Impact of 2008 global economic crisis on suicide: time trend study in 54 countries. Bmj 2013, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.; Chung, H.; Muntaner, C. Social selection in historical time: The case of tuberculosis in South Korea after the East Asian financial crisis. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0217055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clech, L.; Meister, S.; Belloiseau, M.; Benmarhnia, T.; Bonnet, E.; Casseus, A.; Cloos, P.; Dagenais, C.; De Allegri, M.; Du Loû, A.D.; et al. Healthcare system resilience in Bangladesh and Haiti in times of global changes (climate-related events, migration and Covid-19): an interdisciplinary mixed method research protocol. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, C.; Hawton, K.; Geulayov, G.; Waters, K.; Ness, J.; Rehman, M.; Townsend, E.; Appleby, L.; Kapur, N. Self-harm in midlife: analysis using data from the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England. Br. J. Psychiatry 2019, 215, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, W.M.; Gfroerer, J.; Conway, K.P.; Finger, M.S. Unemployment and substance outcomes in the United States 2002--2010. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014, 142, 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdoba-Doña, J.A.; San Sebastián, M.; Escolar-Pujolar, A.; Mart\’\inez-Faure, J.E.; Gustafsson, P.E. Economic crisis and suicidal behaviour: the role of unemployment, sex and age in Andalusia, southern Spain. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, D.M.; Sportiche, N. Economic crises and mental health: Effects of the great recession on older Americans. 2022.

- De Goeij, M.C.M.; Suhrcke, M.; Toffolutti, V.; van de Mheen, D.; Schoenmakers, T.M.; Kunst, A.E. How economic crises affect alcohol consumption and alcohol-related health problems: a realist systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 131, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, L.J.; Han, B.; Dowd, W.N.; Cowell, A.J.; Forman-Hoffman, V.L.; Davies, M.C.; Colpe, L.J. Behavioral health outcomes among adults: associations with individual and community-level economic conditions. Psychiatr. Serv. 2016, 67, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbogen, E.B.; Lanier, M.; Montgomery, A.E.; Strickland, S.; Wagner, H.R.; Tsai, J. Financial strain and suicide attempts in a nationally representative sample of US adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 189, 1266–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Health inequalities, the financial crisis, and infectious disease in Europe; ECDC: Stockholm, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Falagas, M.E.; Vouloumanou, E.K.; Mavros, M.N.; Karageorgopoulos, D.E. Economic crises and mortality: a review of the literature. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2009, 63, 1128–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feghali, R.; El-Hachem, C.; Bakhos, G.; Zarzour, M.; Khalil, R.B. The impact of economic crisis on the mental health of children and adolescents: a systematic review. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2025, 104613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferry, F.; Kent, L.; Rosato, M.; Curran, E.; Leavey, G. Trends in psychotropic medication across occupation types before and during the Covid-19 pandemic: a linked administrative data study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbes, M.K.; Krueger, R.F. The great recession and mental health in the United States. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 7, 900–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, Z.; Ebrahimi, P.; Yazdani, S.; Aryankhesal, A.; Heydari, M.; Maleki, M. Analysis for health system resilience against the economic crisis: a best-fit framework synthesis. Heal. Res. Policy Syst. 2025, 23, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountoulakis, K.N.; Grammatikopoulos, I.A.; Koupidis, S.A.; Siamouli, M.; Theodorakis, P.N. Health and the financial crisis in Greece. Lancet 2012, 379, 1001–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountoulakis, K.N.; Siamouli, M.; Grammatikopoulos, I.A.; Koupidis, S.A.; Siapera, M.; Theodorakis, P.N. Economic crisis-related increased suicidality in Greece and Italy: a premature overinterpretation. J Epidemiol Community Heal. 2013, 67, 379–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasquilho, D.; Matos, M.G.; Salonna, F.; Guerreiro, D.; Storti, C.C.; Gaspar, T.; Caldas-de-Almeida, J.M. Mental health outcomes in times of economic recession: a systematic literature review. BMC Public Health 2015, 16, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcy, A.M.; Vågerö, D. Unemployment and suicide during and after a deep recession: a longitudinal study of 3.4 million Swedish men and women. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 1031–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gili, M.; Roca, M.; Basu, S.; McKee, M.; Stuckler, D. The mental health risks of economic crisis in Spain: evidence from primary care centres, 2006 and 2010. Eur. J. Public Health 2013, 23, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golberstein, E.; Gonzales, G.; Meara, E. How do economic downturns affect the mental health of children? Evidence from the National Health Interview Survey. Health Econ. 2019, 28, 955–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodell, J.W. COVID-19 and finance: Agendas for future research. Financ. Res. Lett. 2020, 35, 101512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra, O.; Eboreime, E. The impact of economic recessions on depression, anxiety, and trauma-related disorders and illness outcomes—a scoping review. Behav. Sci. (Basel) 2021, 11, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnell, D.; Harbord, R.; Singleton, N.; Jenkins, R.; Lewis, G. Factors influencing the development and amelioration of suicidal thoughts in the general population: Cohort study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2004, 185, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J.D. Historical oil shocks. In Routledge Handbook of Major Events in Economic History; Routledge, 2013; pp. 239–265. [Google Scholar]

- Haw, C.; Hawton, K.; Gunnell, D.; Platt, S. Economic recession and suicidal behaviour: Possible mechanisms and ameliorating factors. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2015, 61, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawton, K.; Bergen, H.; Geulayov, G.; Waters, K.; Ness, J.; Cooper, J.; Kapur, N. Impact of the recent recession on self-harm: longitudinal ecological and patient-level investigation from the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 191, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heggebø, K.; Tøge, A.G.; Dahl, E.; Berg, J.E. Socioeconomic inequalities in health during the great recession: a scoping review of the research literature. Scand. J. Public Health 2019, 47, 635–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henkel, D. Unemployment and substance use: a review of the literature (1990-2010). Curr. Drug Abuse Rev. 2011, 4, 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houle, J.N.; Light, M.T. The home foreclosure crisis and rising suicide rates, 2005 to 2010. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 1073–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarroch, R.; Tajik, B.; Tuomainen, T.-P.; Kauhanen, J. Economic Recession and the Long Term Risk of Psychiatric Disorders and Alcohol Related Diseases—A Cohort Study From Eastern Finland. Front. psychiatry 2022, 13, 794888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanikolos, M.; Mladovsky, P.; Cylus, J.; Thomson, S.; Basu, S.; Stuckler, D.; Mackenbach, J.P.; McKee, M. Financial crisis, austerity, and health in Europe. Lancet 2013, 381, 1323–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kentikelenis, A.; Papanicolas, I. Economic crisis, austerity and the Greek public health system. Eur. J. Public Health 2012, 22, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khramov, M.V.; Lee, M.J.R. The Economic Performance Index (EPI): an intuitive indicator for assessing a country’s economic performance dynamics in an historical perspective. International Monetary Fund 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopasker, D.; Montagna, C.; Bender, K.A. Economic insecurity: A socioeconomic determinant of mental health. SSM-population Heal. 2018, 6, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langthorne, M.; Bambra, C. Health inequalities in the Great Depression: a case study of Stockton on Tees, North-East England in the 1930s. J. Public Health (Bangkok) 2020, 42, e126–e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaropoulos, L. Greek economic crisis: not a tragedy for health. Bmj 2012, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llosa, J.A.; Menéndez-Espina, S.; Agulló-Tomás, E.; Rodr\’\iguez-Suárez, J. Job insecurity and mental health: A meta-analytical review of the consequences of precarious work in clinical disorders. 2018.

- Maresso, A.; Mladovsky, P.; Thomson, S.; Sagan, A.; Karanikolos, M.; Richardson, E.; Cylus, J.; Evetovits, T.; Jowett, M.; Figueras, J.; et al. Economic crisis, health systems and health in Europe; Copenhagen WHO, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Matsubayashi, T.; Sekijima, K.; Ueda, M. Government spending, recession, and suicide: evidence from Japan. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maynou, L.; Saez, M. Economic crisis and health inequalities: evidence from the European Union. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, H.; Bebbington, P.; Brugha, T.; Jenkins, R.; McManus, S.; Stansfeld, S. Job insecurity, socio-economic circumstances and depression. Psychol. Med. 2010, 40, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, A.; Page, A.; LaMontagne, A.D. Cause and effect in studies on unemployment, mental health and suicide: a meta-analytic and conceptual review. Psychol. Med. 2014, 44, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minelli, L.; Pigini, C.; Chiavarini, M.; Bartolucci, F. Employment status and perceived health condition: longitudinal data from Italy. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modrek, S.; Hamad, R.; Cullen, M.R. Psychological well-being during the great recession: changes in mental health care utilization in an occupational cohort. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, E.V. The Great Depression, 1873-96. In The Theory and Practice of Central Banking, 1797–1913; Cambridge University Press, 2013; pp. 187–208. [Google Scholar]

- Mucci, N.; Giorgi, G.; Roncaioli, M.; Fiz Perez, J.; Arcangeli, G. The correlation between stress and economic crisis: a systematic review. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2016, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nour, S.; Labonté, R.; Bancej, C. Impact of the 2008 global financial crisis on the health of Canadians: repeated cross-sectional analysis of the Canadian Community Health Survey, 2007--2013. J Epidemiol Community Heal. 2017, 71, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olfson, M.; Wang, S.; Wall, M.; Marcus, S.C.; Blanco, C. Trends in serious psychological distress and outpatient mental health care of US adults. JAMA psychiatry 2019, 76, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, D.; Stavropoulou, C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. Health outcomes during the 2008 financial crisis in Europe: systematic literature review. Bmj 2016, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, K.I.; Moser, K. Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta-analyses. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 74, 264–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaglio, G.; Karapiperis, T.; Van Woensel, L.; Arnold, E.; McDaid, D. Austerity and health in Europe. Health Policy (New York) 2013, 113, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachiotis, G.; Stuckler, D.; McKee, M.; Hadjichristodoulou, C. What has happened to suicides during the Greek economic crisis? Findings from an ecological study of suicides and their determinants (2003--2012). BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, A.; Basu, S.; McKee, M.; Marmot, M.; Stuckler, D. Austere or not? UK coalition government budgets and health inequalities. J. R. Soc. Med. 2013, 106, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, A.; McKee, M.; Stuckler, D. Economic suicides in the great recession in Europe and North America. Br. J. Psychiatry 2014, 205, 246–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regidor, E.; Vallejo, F.; Granados, J.A.T.; Viciana-Fernández, F.J.; de la Fuente, L.; Barrio, G. Mortality decrease according to socioeconomic groups during the economic crisis in Spain: a cohort study of 36 million people. Lancet 2016, 388, 2642–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.; Loureiro, A.; Cardoso, G. Social determinants of mental health: a review of the evidence. Eur. J. Psychiatry 2016, 30, 259–292. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.; Resurrección, D.M.; Antunes, A.; Frasquilho, D.; Cardoso, G. Impact of economic crises on mental health care: a systematic review. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinyor, M.; Silverman, M.; Pirkis, J.; Hawton, K. The effect of economic downturn, financial hardship, unemployment, and relevant government responses on suicide. Lancet Public Heal. 2024, 9, e802–e806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterud, T.; Lunde, L.-K.; Berg, R.; Proper, K.I.; Aanesen, F. Mental health effects of unemployment and re-employment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Occup. Environ. Med. 2025, 82, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuckler, D.; Basu, S.; Suhrcke, M.; Coutts, A.; McKee, M. The public health effect of economic crises and alternative policy responses in Europe: an empirical analysis. Lancet 2009, 374, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suhrcke, M.; Stuckler, D.; Suk, J.E.; Desai, M.; Senek, M.; McKee, M.; Tsolova, S.; Basu, S.; Abubakar, I.; Hunter, P.; et al. The impact of economic crises on communicable disease transmission and control: a systematic review of the evidence. PLoS One 2011, 6, e20724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapia Granados, J.A.; Diez Roux, A.V. Life and death during the Great Depression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009, 106, 17290–17295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uutela, A. Economic crisis and mental health. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2010, 23, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gool, K.; Pearson, M. Health, austerity and economic crisis: Assessing the short-term impact in OECD countries. 2014.

- Van Hal, G. The true cost of the economic crisis on psychological well-being: a review. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2015, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderoost, F.; van der Wielen, S.; van Nunen, K.; Van Hal, G. Employment loss during economic crisis and suicidal thoughts in Belgium: a survey in general practice. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2013, 63, e691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgolino, A.; Costa, J.; Santos, O.; Pereira, M.E.; Antunes, R.; Ambrosio, S.; Heitor, M.J.; Vaz Carneiro, A. Lost in transition: a systematic review of the association between unemployment and mental health. J. Ment. Heal. 2022, 31, 432–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wade, R. Essays on global financial crisis: The crisis as opportunity. Cambridge J. Econ. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, L.R. Financial strain and mental health among older adults during the great recession. Journals Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2016, 71, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No | Study | Country/Region | Study Design | Mental Disorder Type | Key Findings/Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ostamo & Lönnqvist (2001) | Finland | Repeated cross-sectional | Suicide | Male attempted suicide rates decreased significantly during severe recession |

| 2 | Solantaus et al. (2004) | Finland | Cohort | Child Mental Health | Family economic stress creates risk for child mental health through family processes |

| 3 | Munne (2005) | Argentina | Cross-sectional | Substance Use | Economic crisis led to drinking more at home, shifting to cheaper alcohol |

| 4 | Lindstrom (2005) | Sweden | Cross-sectional | Psychological Distress | Unemployed: OR=5.81 (6.43-7.79) for psychological distress |

| 5 | Savarovalci et al. (2005) | Brazil | Cross-sectional | Depression/Anxiety | Strong association between unemployment and depression/anxiety in men |

| 6 | Reinhardt Pedersen et al. (2005) | Denmark/Sweden | Cross-sectional | Child Psychosomatic | Children with unemployed parents: OR=1.52-3.20 for psychosomatic symptoms |

| 7 | Sleskova et al. (2006) | Slovakia | Cross-sectional | Adolescent Health | Parental unemployment negatively associated with adolescent health |

| 8 | Newman & Bland (2007) | Canada | Case-control | Suicide | Association between unemployment and parasuicide: OR=12.0 (6.0-23.9) |

| 9 | Thomas et al. (2007) | UK | Cohort | Psychological Distress | Job loss increased risk of distress: OR men=3.15 (2.50-3.98) |

| 10 | Taylor et al. (2007) | UK | Cohort | Psychological Distress | Housing payment problems and debts have detrimental effects on mental wellbeing |

| 11 | Meltzer et al. (2007) | UK | Cross-sectional | Suicide | Those in debt twice as likely to think about suicide |

| 12 | Kondo et al. (2008) | Japan | Repeated cross-sectional | Self-Rated Health | OR for poor self-rated health increased from 1.02 to 1.14 after crisis |

| 13 | Charles & Decicca (2008) | USA | Repeated cross-sectional | Psychological Distress | 1% unemployment → 3.4% point increase in sadness |

| 14 | Stuckler et al. (2009) | 26 EU countries | Ecological | Suicide | 1% unemployment increase → 0.79% increase in suicide <65 years |

| 15 | Carter et al. (2009) | New Zealand | Cohort | Psychological Distress | Lowest wealth quintile: RR=3.06 (2.63-3.50) for psychological distress |

| 16 | Molarius et al. (2009) | Sweden | Cross-sectional | Depression/Anxiety | Unemployment (OR=2.9) and financial strain strongly related to anxiety/depression |

| 17 | Chang et al. (2009) | Japan; Hong Kong; South Korea | Time-trend analysis (Japan; Hong Kong; South Korea) | Suicide | Suicide rate in men: RR=1.387 (1.358-1.417) after Asian crisis | Suicide rate in men: RR=1.443 (1.263-1.649) | Suicide rate in men: RR=1.446 (1.387-1.507) |

| 18 | Wang et al. (2010) | Canada | Cross-sectional | Depression | 12-month MDD prevalence increased from 5.1% to 7.6% post-crisis |

| 19 | Lee et al. (2010) | Hong Kong | Repeated cross-sectional | Depression | MDE prevalence increased from 8.5% (2007) to 17.25% (2009) |

| 20 | Ford et al. (2010) | England | Cross-sectional | Common Mental Disorders | Risk of common mental disorders greater in unemployed individuals |

| 21 | Meltzer et al. (2010) | UK | Cross-sectional | Depression | Job insecurity (OR=1.58) and debt (OR=2.17) associated with depression |

| 22 | Borges et al. (2010) | 21 countries | Cross-sectional | Suicide | Unemployment strong risk factor for suicidal ideation and attempts |

| 23 | Stuckler et al. (2011) | Multiple EU countries | Ecological time-series | Suicide | Suicide increased ~7% in old EU countries after 2008 recession |

| 24 | Madianos et al. (2011) | Greece | Repeated cross-sectional | Depression | Major depression prevalence: 6.8% (2008) vs 3.3% (2009) |

| 25 | Davalos & French (2011) | USA | Cohort | General Mental Health | State unemployment worsens individuals’ mental HRQoL |

| 26 | Strandh et al. (2011) | Sweden | Cohort | Psychological Distress | Negative effects of unemployment rate on mental health of unemployed |

| 27 | Economou et al. (2011) | Greece | Repeated cross-sectional | Suicide | High economic distress associated with suicide attempts (p<0.001) |

| 28 | Hong et al. (2011) | South Korea | Repeated cross-sectional | Suicide | Income gradient-related suicide behavior increased post-recession |

| 29 | Karjalainen et al. (2011) | Finland | Case-control | Substance Use | Unemployment strong predictor of driving under influence of drugs |

| 30 | Jefferis et al. (2011) | EU countries /Chile | Cohort | Depression | Job loss → RR=1.58 (0.76-3.27) for depression |

| 31 | Freyer-Adam et al. (2011) | Germany | Cross-sectional | Substance Use | 84.8% of long-term unemployed young men were smokers |

| 32 | Sareen et al. (2011) | USA | Cohort | Mood/Anxiety/Substance | Income decrease → RR=1.30 (1.06-1.60) for mood/anxiety/substance disorders |

| 33 | Sargent-Cox et al. (2011) | Australia | Cohort | Depression/Anxiety | Economic distress linked to depression/anxiety in older adults |

| 34 | Borges et al. (2011) | Portugal | Cross-sectional | Adolescent Health | Parental unemployment negatively impacts adolescent health perceptions |

| 35 | Barr et al. (2012) | England | Time-trend analysis | Suicide | Excess suicides in men: RR~1.036 (1.02-1.052) |

| 36 | Katikireddi et al. (2012) | England | Repeat cross-sectional | Psychological Distress | GHQ caseness in men: OR=1.53 (1.26-1.86) in 2009 vs 2008 |

| 37 | Gill et al. (2012) | Spain | Repeated cross-sectional | Depression | Major depression increased by 194% from pre-crisis period |

| 38 | Reeves et al. (2012) | USA | Ecological | Suicide | 1% unemployment rise → 0.59% increase in suicide rate |

| 39 | Berchick et al. (2012) | USA | Cohort | Depression | Job loss linked with depressive symptoms: coeff=0.333 (SE=0.108) |

| 40 | Butterworth et al. (2012) | Australia | Cohort | General Mental Health | 19.1% with poor mental health experienced subsequent unemployment |

| 41 | Bellis et al. (2012) | UK | Cross-sectional | Life Satisfaction | Most deprived: 17.1% low life satisfaction vs 8.9% most affluent |

| 42 | McLaughlin et al. (2012) | USA | Cohort | Depression | Foreclosure → IDR=2.4 (1.6-3.6) for major depression |

| 43 | Redonnet et al. (2012) | France | Cohort | Substance Use | Low SES linked with higher rates of tobacco (OR=2.11) and cannabis use |

| 44 | Sirvio et al. (2012) | Finland | Cohort | Psychological Distress | Precarious workers have more distress symptoms vs permanent workers |

| 45 | Chang et al. (2013) | 54 countries | Time-trend analysis | Suicide | Suicide rate in men: RR=1.033 (1.027-1.039) after 2008 crisis |

| 46 | Garcy & Vägerö (2013) | Sweden | Longitudinal Cohort | Suicide | Suicide mortality in men post-recession: HR=1.43 (1.31-1.56) |

| 47 | Vanderoost et al. (2013) | Belgium | Cross-sectional survey | Suicide | Employment loss → OR=8.8 (2-39.3) for suicidal thoughts |

| 48 | Bartoll et al. (2013) | Spain | Repeated cross-sectional | General Mental Health | Poor mental health in men: PR=1.15 (1.04-1.26) during crisis |

| 49 | De Vogli et al. (2013) | Italy | Ecological time-series | Mental Disorder Mortality | 1% unemployment increase → RR=1.074 (1.032-1.117) for mental disorder mortality |

| 50 | Modrek (2013) | USA | Longitudinal Industrial Cohort | Hypertension | High-layoff plant work → OR=1.6 (1.04-2.48) for hypertension |

| 51 | Zavras et al. (2013) | Greece | Repeated cross-sectional | Self-Rated Health | Self-reported good health deteriorated from 71% (2006) to 68.8% (2011) |

| 52 | Vandoros et al. (2013) | Greece/Poland | Repeated cross-sectional | General Health | Greece: OR=1.16 (1.04-1.29) for poor health vs control population |

| 53 | Hauksdottir et al. (2013) | Iceland | Cohort | Stress | High stress levels increased only among women during crisis |

| 54 | Gili et al. (2013) | Spain | Repeated cross-sectional | Depression | Risk of depression during crisis almost 3× higher than before |

| 55 | Bor et al. (2013) | USA | Cohort | Substance Use | Binge drinking increased from 4.8% (2006-07) to 5.1% (2008-09) |

| 56 | Lopez Bernal et al. (2013) | Spain | Ecological | Suicide | 8.0% increase in suicide rate above trend since financial crisis |

| 57 | Flint et al. (2013) | UK | Cohort | Psychological Distress | Mental distress among unemployed 2.20× (1.98-2.40) higher than employed |

| 58 | Eichhorn (2013) | 40 European societies | Ecological | Life Satisfaction | Unemployment lowers life satisfaction by 0.5-0.785 points |

| 59 | Evans-Lacko et al. (2013) | Europe (27 countries) | Repeated cross-sectional | General Mental Health | People with mental health problems more vulnerable to job loss: OR=1.12 (1.03-1.34) |

| 60 | Fountoulakis et al. (2013) | Greece | Ecological | Suicide | No correlation found between suicide rates and unemployment |

| 61 | Sauma et al. (2013) | England | Ecological | Suicide | Unemployment-suicide association significant at regional level only |

| 62 | Shin & Choi (2013) | South Korea | Ecological | Substance Use | 20× higher alcohol-attributable deaths in unemployed |

| 63 | Olesen et al. (2013) | Australia | Cohort | General Mental Health | Negative correlation (r=-0.16) between unemployment and mental health |

| 64 | Kan (2013) | Japan | Cohort | General Mental Health | Job loss decreases mental health by 12.0 points (MHI-5) |

| 65 | Pinto-Meza et al. (2013) | EU countries | Cross-sectional | Depression/Anxiety | Unemployed showed highest prevalence of mood/anxiety disorders |

| 66 | Snoradottir et al. (2013) | Iceland | Cross-sectional | Psychological Distress | Downsizing associated with increased psychological distress |

| 67 | Murphy et al. (2013) | USA | Cross-sectional | Substance Use | Housing instability associated with alcohol dependence symptoms |

| 68 | Fone et al. (2013) | Wales, UK | Cross-sectional | General Mental Health | Income inequality at regional level associated with poorer mental health |

| 69 | Saurina et al. (2013) | England | Longitudinal | Suicide | Unemployment increase → coeff=0.384 for male suicide in South West |

| 70 | Economou et al. (2013) | Greece; Greece | Repeated cross-sectional (Greece) | Depression/Suicide | Major depression odds greater in 2011 vs 2008: OR=10.0 (1.97-3.43) | Suicidal ideation increased from 5.2% (2009) to 6.7% (2011) |

| 71 | Minelli et al. (2014) | Italy | Longitudinal Panel | General Health | First-job seekers vs permanent workers: OR=0.65 for worse health |

| 72 | Iglesias García et al. (2014) | Spain | Ecological Time-Series | Mental Health Care Use | Unemployment rate negatively correlated with mental health care demand |

| 73 | Antonakakis & Collins (2014) | Greece | Time-Series | Suicide | 1% decrease in govt expenditure → semi-elasticity=-0.0043 for male suicide |

| 74 | Drydakis (2014) | Greece | Longitudinal panel | General Mental Health | Unemployment (2008-2013) → β=0.0318 for worse mental health |

| 75 | Korhonen et al. (2014) | Finland | Time Series Analysis | Suicide | Economic hardship → coeff=4.12 for suicide rate (1970-2010) |

| 76 | Ásgeirsdóttir et al. (2014) | Iceland | Population-based cohort | Suicide | Economic collapse → RR=0.85 (0.76-0.96) for male suicide attempts |

| 77 | Bartoll et al. (2014) | Spain | Repeated cross-sectional | General Mental Health | Poor mental health among men: PR=1.15 (1.04-1.26) during crisis |

| 78 | Blomqvist et al. (2014) | Sweden | Repeated cross-sectional | Psychological Distress | Mental distress increased among women, especially unemployed |

| 79 | Alameda-Palacios et al. (2014) | Spain | Ecological | Suicide | Suicide rates increased in young people (15-44) at 1.21% annually |

| 80 | Pompili et al. (2014) | Italy | Ecological | Suicide | Suicide rate for men in labor force increased 12% (2006-2010) |

| 81 | Coope et al. (2014) | England/Wales | Ecological | Suicide | Downward trend in male suicide rates stopped/reversed after 2008 |

| 82 | Reeves et al. (2014) | EU countries /Canada/USA | Ecological | Suicide | Suicide rose: EU +6.5%, Canada +4.5%, USA +4.8% |

| 83 | Breuer (2014) | 26 EU countries | Ecological | Suicide | 1% unemployment increase → 0.79% increase in suicide <65 years |

| 84 | Toffolutti & Suhrcke (2014) | 23 EU countries | Ecological | Suicide | 1% unemployment increase → 34.1% increase in suicide rates |

| 85 | Baumbach & Gulis (2014) | 8 EU countries | Ecological | Suicide | Suicide increases: Germany +5.3%, Poland +19.3% with unemployment rise |

| 86 | Moheenich-Enaghlou (2014) | USA | Ecological | Suicide | Positive correlation between unemployment and suicide in prime-age workers |

| 87 | Phillips & Nugent (2014) | USA | Ecological | Suicide | Strong positive association between unemployment and suicide rates |

| 88 | Cylus et al. (2014) | USA | Ecological | Suicide | 1% unemployment → 0.16 more suicide deaths per 100,000 |

| 89 | Chan et al. (2014) | South Korea | Ecological | Suicide | Unemployment rate positively associated with suicide rates |

| 90 | Madianos et al. (2014) | Greece | Ecological | Suicide | Suicide rates correlated with public debt/GDP and unemployment |

| 91 | Fountoulakis et al. (2014) | Hungary | Ecological | Suicide | Unemployment associated with suicidality after 3-5 year lag |

| 92 | Houle & Light (2014) | USA | Ecological | General Mental Health | Foreclosure rate contributed to increased suicides (b=0.04, p<0.1) |

| 93 | Mattei et al. (2014) | Italy | Ecological | General Mental Health | GDP decrease associated with male suicides due to financial problems |

| 94 | McKenzie et al. (2014) | New Zealand | Cohort | Psychological Wellbeing | Job loss decreased mental health by 1.34 points (SF-36) |

| 95 | Milner et al. (2014) | Australia | Cohort | Depression | Unemployed: -1.64 points mental health vs employed |

| 96 | Aslund et al. (2014) | Sweden | Cross-sectional | Substance Use | Unemployed: OR=2.11 (1.79-2.50) for poor psychological wellbeing |

| 97 | Riumallo-Herl et al. (2014) | EU countries /USA | Cohort | Suicide | Unemployment associated with 42% increase in depressive symptoms (USA) |

| 98 | Gfroerer et al. (2014) | USA | Repeated cross-sectional | Suicide | Unemployed show higher prevalence of substance use disorders |

| 99 | Miret et al. (2014) | Spain | Cross-sectional | Suicide | Unemployment associated with suicidal ideation in 18-49 year olds |

| 100 | Rhodes et al. (2014) | Canada | Cohort | Adolescent Health | Downward trend in adolescent suicidal behavior stopped after recession |

| 101 | Gassman-Pines et al. (2014) | USA | Repeated cross-sectional | Life Satisfaction | State job loss increased girls’ suicidal ideation and plans |

| 102 | Pförtner et al. (2014) | 31 countries | Cross-sectional | Depression | Ireland/Portugal: 9-17% rise in adolescent health complaints with unemployment |

| 103 | Klanšček et al. (2014) | Slovenia | Cross-sectional | Suicide | Low SES adolescents: 4× higher odds of low life satisfaction |

| 104 | Cagney et al. (2014) | USA | Cohort | Mental Health Care Use | Foreclosure → OR=1.75 (1.14-2.67) for depression in older adults |

| 105 | Córdoba-Doña et al. (2014) | Spain; Spain | Ecological time-series (Spain) | Suicide | 1% unemployment increase → 1.08 increase in suicide attempt rate | 8.6% more suicide attempts (2017 in men, 2972 in women) 2008-2012 |

| 106 | Modrek et al. (2015) | USA | Longitudinal Panel | Suicide | Post-2009 trend: β=0.0192 (0.0115-0.0269) for outpatient MH visits |

| 107 | Reeves et al. (2015) | 20 EU countries | Cross-national panel | Suicide | 1% male unemployment increase → 0.94% increase in male suicide |

| 108 | Branas et al. (2015) | Greece | Interrupted Time Series | Suicide | Austerity measures → 35.7% increase in total suicides |

| 109 | Rachiotis et al. (2015) | Greece | Ecological Study | Stress/General Mental Health | Austerity period (2011-2012) → RR=1.34 for total suicide rate |

| 110 | Norstrom & Gronqvist (2015) | 30 countries | Ecological | Mental Health Care Use | Unemployment detrimental to suicide, especially in less protected countries |

| 111 | Giorgi et al. (2015) | Italy | Cross-sectional | Suicide | Job stress mediates relationship between fear of crisis and mental health |

| 112 | Dunlap et al. (2016) | USA | Cross-sectional (NSDUH) | General Mental Health | County unemployment (Q4 vs Q1) → RR=0.58 (0.46-0.74) for MH service use |

| 113 | Ásgeirsdóttir et al. (2016) | Iceland | Population-based cohort | Mental Health Care Use | Economic collapse → RR=0.86 (0.79-0.92) for female suicide attempts |

| 114 | Nour et al. (2016) | Canada | Repeated cross-sectional | Depression | Austerity period → OR=1.26 (1.17-1.34) for poor mental health |

| 115 | Buffel et al. (2016) | Europe (27 countries) | Repeated cross-sectional | Depression | High unemployment → OR=1.031 for contacting GP for MH (employed men) |

| 116 | Sicras-Mainar & Navarro-Artieda (2016) | Spain | Retrospective observational | Mental Health Care Use | MDD prevalence increased 0.081 (0.074-0.088) during crisis |

| 117 | Lee et al. (2017) | Taiwan | Interrupted time series | Depression | Low-income men: 18% increase in depression hospitalizations post-2008 |

| 118 | Petrou (2017) | Cyprus | Interrupted time-series | Suicide | Co-payment introduction non-significant effect on MH service visits |

| 119 | Forbes & Krueger (2019) | USA | Longitudinal cohort | Suicide | Financial hardship → OR=1.3 (1.23-1.42) for depression symptoms |

| 120 | Elbogen et al. (2020) | USA | Longitudinal Cohort | Depression | Cumulative financial strain → OR=1.53 (1.32-1.77) for suicide attempt |

| 121 | Meda et al. (2022) | 175 countries | Ecological | Suicide | 1% unemployment increase → RR=1.03 (1.02-1.03) for male suicide (30-59) |

| 122 | Bracone et al. (2024) | Italy | Prospective cohort | Child Mental Health | High economic hardship → OR=1.84 (1.26-2.7) for depression increase |

| Group | Key Findings |

|---|---|

| Unemployed individuals |

Higher risk of depression, anxiety, distress, and suicide. Longer unemployment = worse mental health outcomes. |

| Precarious/Insecure workers |

Job insecurity and temporary work linked to mental distress. Fear of crisis worsened mental health among workers. |

| Individuals in debt / Financial hardship |

Debt and housing payment problems associated with depression and suicidal ideation. Low wealth linked to high psychological distress. |

| Families and children |

Parental unemployment negatively affected children’s mental health. Family economic stress mediated child psychological outcomes. |

| Adolescents and young adults |

Recession linked to increased psychological complaints and suicidal behaviors in adolescents. Parental job loss affected adolescent well-being. |

| Older adults |

Economic distress and foreclosure linked to depression in older adults. Financial insecurity worsened mental health in aging populations. |

| People with pre-existing mental illness |

More vulnerable to job loss during recession. Faced increased discrimination and isolation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).