1. Introduction

Children of parents experiencing mental health challenges, such as anxiety and depression, are up to twice as likely to experience their own mental health difficulties, especially if families do not have adequate support [

1,

2]. Parental mental health challenges are linked with an increased likelihood of parenting difficulties, including reduced warmth and increased overcontrolling, harsh or inconsistent parenting [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. These parenting difficulties have been identified as a key mechanism in the intergenerational transmission of mental health issues [

8,

9,

10] and can worsen parent mental health, creating a vicious cycle of distress within families [

11,

12]. Fortunately, parenting is a modifiable factor, with evidence-based parenting interventions shown to improve parenting and child outcomes for parents with and without mental health challenges [

13,

14,

15]. However, access to parenting intervention for these parents can be limited and they are not consistently offered parenting support within mental health treatment pathways [

16,

17]. This is a missed opportunity given the well-established interrelationships between parenting, parental mental health and child outcomes [

18,

19].

Integrating parenting support into parent mental health care can offer holistic, family-focused care for families, while enhancing the recovery of parents [

11,

20]. Research shows that for parents with mental health issues, interventions targeting both parental mental health and parenting yield more wide-ranging benefits across parent symptoms, parenting and child outcomes compared to those targeting either issue alone [

21,

22]. Adult mental health services are well placed to provide a combined approach, as they can extend their support of parent mental health to address parenting as one aspect of the parent’s identity, functioning and wellbeing [

20,

23,

24]. There are several face-to-face interventions and initiatives that integrate parenting support within adult mental health services [

23,

25,

26,

27], for example Let’s Talk about Children [

28,

29] and the ParentingWell practice approach [

30,

31]. These have been found to be acceptable among parents and clinicians and to be effective in improving parent mental health, parenting and child outcomes as well as clinician confidence and skills in supporting parenting [

32,

33]. Despite this, implementation of family-focused support into mental health settings can be hindered by service barriers including lack of resources, training, time and clinician confidence to deliver parenting intervention alongside mental health care [

34,

35]. Additionally, parents experiencing mental health challenges often face barriers to accessing in-person support such as stigma, competing priorities, fluctuating mood, low energy, childcare demands and transportation difficulties [

36,

37,

38].

One promising approach is implementing technology-assisted parenting programs in existing mental health services, where parenting support is provided partially or entirely via technology [

39]. Technology has the potential to provide parents with accessible, flexible parenting support alongside mental health treatment, by minimising barriers such as stigma, lack of time and scheduling demands [

40,

41]. By reducing reliance on clinicians, this approach can also decrease service burden and costs and support feasible long-term implementation in resource-limited adult mental health services [

42,

43]. Importantly, evidence is emerging that technology-assisted parenting programs are acceptable and effective in improving parenting and child outcomes among parents with mental health challenges [

44,

45,

46]. However, to our knowledge these programs have not yet been embedded within adult mental health settings.

Partners in Parenting Kids (PiP Kids; formerly known as Parenting Resilient Kids or PaRK) is a digital parenting program that may be well suited for integration. PiP Kids is a fully online program that provides parents with evidence-based parenting strategies to reduce the risk of anxiety and depression in their primary school-aged children [

47,

48,

49]. The original program comprises a self-assessment of parenting practices, a tailored feedback report and self-guided online modules [

47]. In a randomised controlled trial, parents who received PiP Kids showed greater improvements in parenting behaviours compared to those receiving a factsheet intervention [

50]. This evidence of efficacy, together with the successful adaptation of PiP Kids to family services for parents of children experiencing adversity [

51], suggests its potential for integration within adult mental health treatment.

Yet, it remains unclear how well a digital parenting program such as PiP Kids will fit into the existing clinician and service practices at adult mental health services. Additionally, parents with mental health challenges have unique parenting needs, including talking with children about parental mental health, managing their mental health symptoms alongside parenting, and navigating increased parenting stress [

52,

53,

54]. These parents may also face unique barriers to engaging with parenting programs such as debilitating symptoms, low literacy, socioeconomic disadvantage and social isolation [

37,

38]. Generic or fully digital parenting programs such as PiP Kids may therefore not adequately address the specific needs or preferences of these parents [

23,

55]. This highlights the importance of adapting PiP Kids to ensure its acceptability and compatibility with existing service practices and family circumstances.

Co-design or collaboration with relevant stakeholders and end-users is an ideal approach for ensuring a thorough understanding and tailoring to the needs of parents and existing health services [

56]. Actively engaging parents in designing programs is needed to develop an intervention that meets their needs and preferences [

57,

58]. Similarly, service provider perspectives are crucial as they possess specialised knowledge of service practices, are instrumental in advocating for families and may also be key end users involved in program delivery [

51]. Research suggests that adapting programs to fit the context, procedures and workload of the existing health service, while retaining evidence-based content, helps ensure the program is relevant and successfully integrated [

31,

38].

The aim of this study was therefore to co-design and adapt an evidence-based digital parenting program (PiP Kids) for integrative implementation in an existing adult mental health service, to support parents seeking mental health care. Specifically, this study used co-design methods to: 1) identify design considerations for integrating technology-assisted parenting programs by exploring the needs and preferences of parents with lived experience of seeking mental health support and service providers who support these parents. This study then aimed to: 2) design, develop and refine an adapted prototype parenting program, and 3) deliver the online component of the prototype program to parents, to understand its acceptability and identify what further adaptations are needed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

This study was conducted as part of a larger research program, in partnership with a major provider of community health services in Victoria, Australia. As this study specifically focuses on parents seeking mental health support, the mental health services within this community health organisation (including therapeutic counselling for individuals experiencing mild-to-severe mental health challenges, gambling and alcohol and other drug use) were selected as the most appropriate setting for the study.

2.2. Recruitment

We aimed to recruit a small number of participants in this initial study to gain detailed insights into parent and service needs. Small sample sizes are generally considered acceptable in in-depth qualitative studies [

59]. Co-developing and piloting an initial prototype on a small-scale is considered a feasible and cost-effective way of designing and refining new interventions during the development stages [

60]. Findings from these initial iterations can then be used to guide larger-scale iterations and eventual implementation.

2.2.1. Service Providers

Service providers were clinicians and clinical leads employed at the collaborating mental health service, who spoke English and had experience providing mental health support to parents of children aged 5-11 years. All eligible service providers within the collaborating mental health service were invited to participate via an emailed flyer.

2.2.2. Parents

All parent participants were parents or primary caregivers of children aged 5-11 years who spoke English and lived in Australia. Parents were either 1) currently seeking mental health support at the collaborating community health service or 2) had received psychological support for their mental health in the community within the past year. Recruitment occurred via two methods. First, clinicians at the collaborating mental health service distributed flyers to potentially eligible parent clients. Second, flyers were distributed via websites, social media, waiting rooms and mailing lists of community organisations across Australia that support parents with mental health challenges.

2.3. Study Design and Procedure

The Double Diamond design process guided the co-design methods in this study [

61]. Each diamond represents a process of examining an issue broadly followed by taking focused action. As shown in

Figure 1, this study was conducted in three phases that align with the Double Diamond stages. Phase 1 involved workshops with parents and service providers to

discover needs and preferences and

define design considerations for integrating technology-assisted parenting programs into a mental health service. Phase 2 involved workshops with parents and service providers to

develop an initial prototype and validate and refine this design and the design considerations. Phase 3 involved

delivering the online component of the refined prototype to parents, and one-on-one interviews to explore acceptability and identify further adaptations for the next iteration. See

Supplementary Table S1 for a summary of the aims and methods. Due to the iterative nature of the study, further methodological details for each phase are provided within their respective Methods sections below, with each phase informed by findings from the previous one.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

All procedures were approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (approval numbers #35059 and #44564). Participants were provided with a plain language explanatory statement and the opportunity to ask questions prior to consenting. Parent participants were reimbursed with a $35 gift card for each hour spent engaging in a workshop or interview. Service provider participants were not financially compensated as research activities were conducted during their working hours.

Co-design workshops were conducted separately for each participant group to create a safe environment for open discussion and minimise the influence of power imbalances. To ensure parent participant wellbeing, all workshops and interviews were facilitated by a provisional psychologist (the first author) with formal training in mental health, under the supervision of a registered psychologist. Regardless of whether parent participants demonstrated distress, the first author contacted them within 24 hours of their workshop or interview to assess for distress and offer support and crisis resources.

2.5. Researcher Positionality and Reflexivity

The first author is a female clinical psychology PhD candidate and provisional psychologist with interests in mental health, parenting and evidence-based intervention. Other co-authors involved in data interpretation included two academics with expertise in co-design and qualitative research and one professor who is a parent and psychologist with 14 years’ experience working with parents, young people and service providers in co-designing and developing parenting interventions. The remaining co-authors who reviewed the findings and manuscript included professors with expertise in parental mental health, prevention and intervention in mental health, co-design and human computer interaction, as well as service providers with expertise in clinical service delivery and management, several of whom have lived experience of parenting themselves. The first author facilitated all workshops and interviews and kept a reflexive journal documenting her reflections following each activity. During analysis, a conscious effort was made to ensure a balanced integration of perspectives across all three participant groups (parents, clinician and clinical leads) when triangulating findings and identifying themes.

3. Phase 1 Methods and Results: Discover and Define Design Considerations

3.1. Phase 1 Methods

3.1.1. Participants

Parent participants (n=8) were all mothers aged 39-46 years (M=41.1). One was currently seeking mental health support at the collaborating health service and seven had recent lived experience of seeking mental health support in the community. Parents’ self-reported mental health challenges included high stress (n=7), anxiety (n=5), depression (n=4), trauma (n=3) and one each with psychosis, bipolar disorder and grief.

Service provider participants included clinicians (n=5) and clinical leads (n=2), all of whom were women. Clinicians were aged 25-50 years (M=37.8) and included counsellors (n=2) and social workers (n=3) who primarily worked with mild-to-severe mental health challenges (n=4) or gambling concerns (n=1). Clinical leads were aged 52-59 years (M=55.5) and included one team leader who was a psychologist and one service manager who was a social worker. Three clinicians were also mothers with lived experience of depression and/or anxiety, with many of their responses combining their personal and professional perspectives. Several of these instances are highlighted in the results below.

Supplementary Table S2 details further demographic characteristics of the Phase 1 participants.

3.1.2. Data Collection

Phase 1 workshops explored parent and service provider needs and preferences for any technology-assisted parenting program integrated into mental health care. Participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) [

62,

63], before taking part in workshops. Workshop focus and format were informed by relevant literature on co-design, parenting in the context of parental mental health challenges, parenting programs, program adaptation, real-world implementation and clinician experiences and training. All workshops were conducted via Zoom, with audio and video recording. Each workshop lasted 2 hours, including a 5–10-minute break.

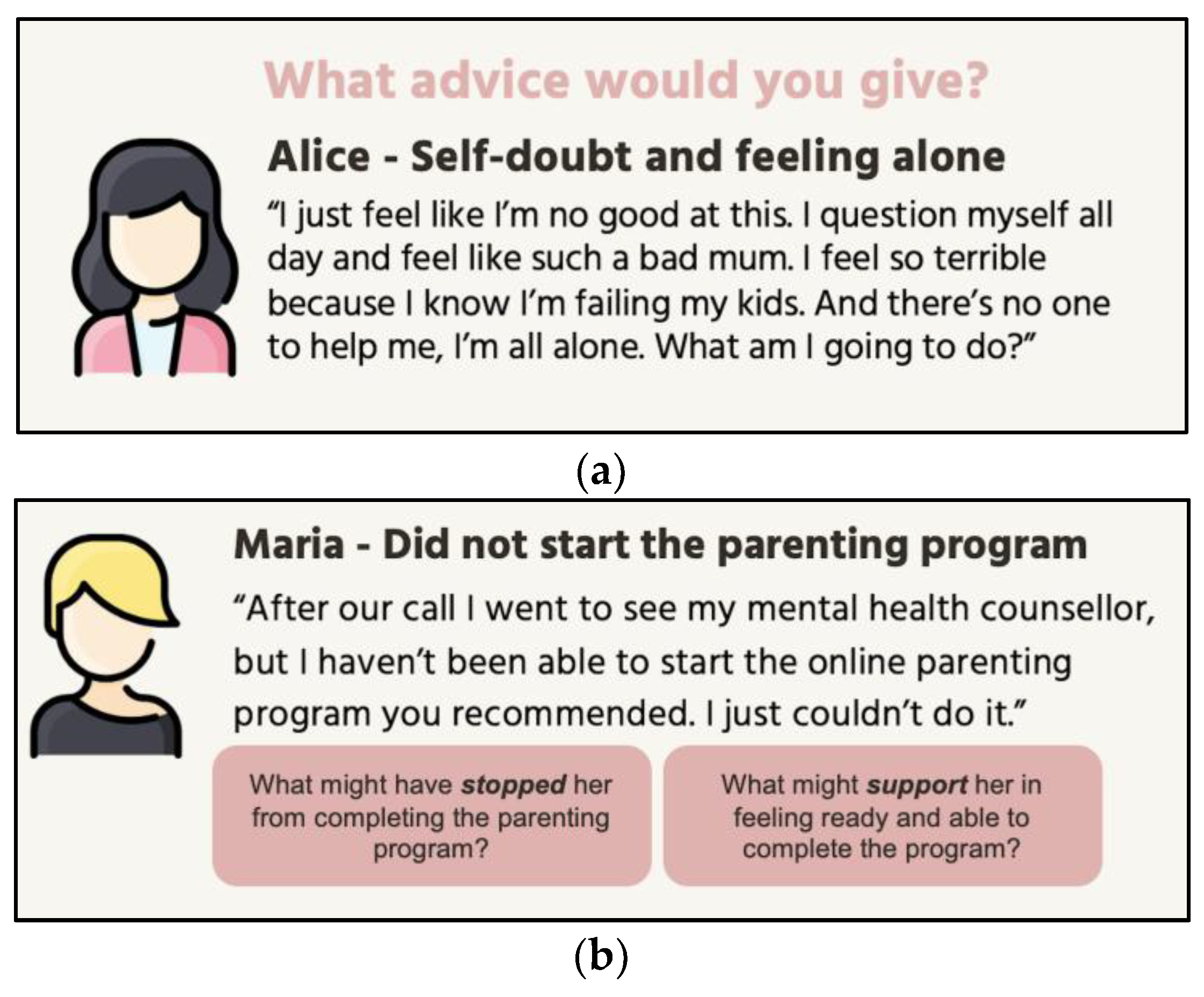

3.1.3. Parent Workshops

Each parent participated in one individual or group workshop during this phase. As parents with mental health challenges often describe feeling guilt, shame and helplessness [

64,

65], this workshop used case-vignettes to create psychological distance where parents can draw on their lived experience reflectively and empathetically without being overwhelmed [

66,

67]. In the vignettes, parent participants role-played as helpline workers providing advice to vignette parents. Activities explored challenges faced by parents in parenting, engaging with parenting programs and applying parenting knowledge as well as strategies to support parents in these areas.

Figure 2 provides examples of activities from the parent workshop.

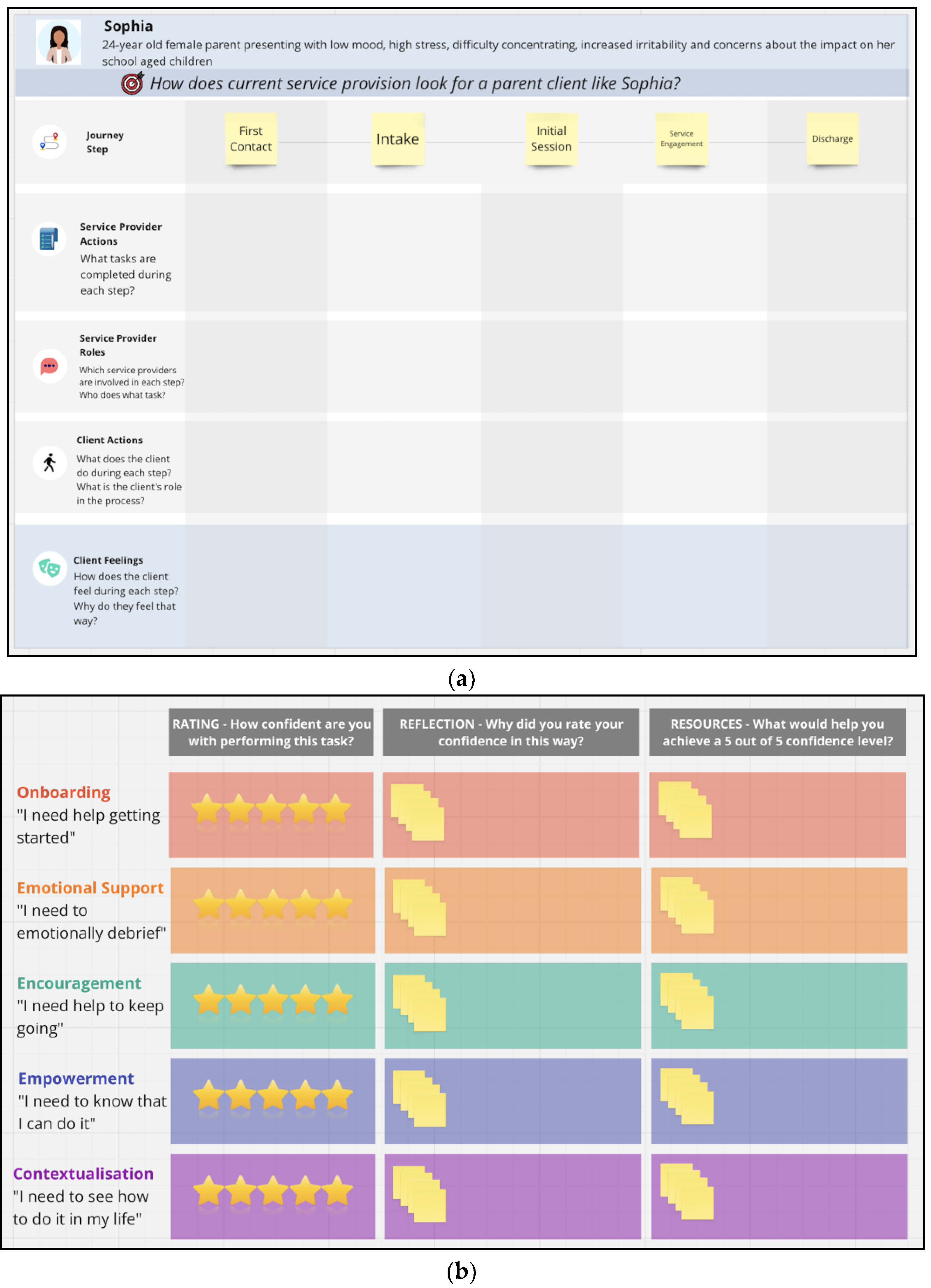

3.1.4. Service Provider Workshops

Service providers attended two rounds of workshops in this phase. The first round examined the service context, focusing on day-to-day service delivery for clinicians and on broader program integration and rganizational resources for clinical leads. This round also explored general challenges faced by parents in applying parenting knowledge and opportunities and barriers within the service to support them. The second round of workshops built on findings from prior workshops by first exploring service provider feedback on emerging themes. Findings from the first round of workshops with parents and clinicians indicated a clear need for clinicians to support parents in engaging with any digital parenting program. Consequently, this round of workshops focused on how to enable clinicians to provide this support. For clinicians, this involved identifying the resources and support they would need, while for clinical leads the focus was on determining what rganizational resources could be provided to address these needs.

Figure 3 presents example activities from these workshops.

3.1.5. Data Analysis

Recordings were transcribed verbatim by an automatic artificial intelligence transcription service (Descript) and corrected by the research team. Transcripts were analysed with the support of NVivo qualitative software, using Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis approach [

68,

69]. Data were coded inductively as the purpose of this phase was to broadly explore the needs and preferences of parents and service providers. We followed the six-phase process of reflexive thematic analysis: 1) data familiarisation, 2) iterative data coding, 3) initial theme generation, 4) theme development and review, 5) refining, defining and naming themes and 6) writing up the findings [

69,

70]. The development and refinement of themes was carried out by the first author in collaboration with the broader research team.

3.2. Phase 1 Results

Participants described five design considerations for adapting the parenting program to address parent and service provider needs and preferences, as identified in the following themes: 1) building parent and clinician readiness for parenting support, 2) emotional and social support for parents and clinicians, 3) practical and personalised parenting knowledge, 4) parent-led empowerment and 5) accessible and integrated support.

Supplementary Table S3 presents each theme and subtheme with additional indicative quotes.

3.2.1. Theme 1: Building Readiness for Parenting Support

Participants described foundational factors influencing parent and clinician readiness to engage in parenting-focused support.

Parental Wellbeing Foundations

All participants emphasised that parents’ mental health, safety and physical wellbeing are prerequisites for their capacity to parent effectively and engage with parenting support. Parent self-care, breaks from parenting and attention to physical health were highlighted as particularly important. Declining mental health, or risk concerns such as family conflict, suicide risk or child protection, were seen as needing stabilisation prior to parenting support. Service providers similarly emphasised the service’s primary focus on parental mental health, with parenting considered a secondary focus when relevant to parent wellbeing.

“They would talk about the difficulties they have with their young kids… but the main focus… the reason they came to me was because of their own mental health. That was the primary issue.” [Clinician 4]

Program Understanding and Confidence

Participants identified understanding the program and feeling confident about its value and use as essential prerequisites among parents and service providers. All groups highlighted their need for a detailed program introduction including its purpose, content, benefits and technology. Parents suggested a clinician could support their introduction and help overcome barriers such as program uncertainty, fear of change, and difficulty getting started. Some clinicians expressed low confidence in parenting issues and requested refresher training on child development, parenting and supporting parents.

“Not training on just the program but training on just working specifically with mums… low self-esteem, feelings of guilt, shame, all that stuff that comes along with being a mum.” [Clinician 5]

Clinical leads proposed that clinicians already possess this knowledge and that training should primarily focus on the program and building clinician confidence in applying their clinical skills to providing support on parenting.

3.2.2. Theme 2: Emotional and Social Support

Emotional support and social and peer connection were seen as crucial for both parents and clinicians.

Emotional Support and Validation

Participants (including clinicians with lived experience) highlighted the need to provide parents with non-judgmental emotional support that avoids criticising them for their mental health difficulties. Normalisation and validation of parent experiences were emphasised to remind parents they are not alone, acknowledge struggles as common, and foster hope. Participants stressed the need for parents to emotionally debrief with support people who listened with empathy and understanding. Strong therapeutic relationships with counsellors or psychologists built on trust, continuity and rapport were seen as essential for parents to safely engage in support.

“You don't often share what's in your mind for fear of judgment… and that is the independent source that is hopefully listening and not judging and giving empathy… Just someone to listen to you is extremely powerful.” [Parent 6]

Social and Peer Connection

Social support was seen as vital for parents and clinicians. Participants noted that connecting parents to family experiences or peers with lived experience of mental health challenges fostered support, belonging and joy, and reduced isolation and self-blame.

“It would be good for her to meet other mums… so you get to share experiences and… gets to hear that she's not alone… everyone goes through that same feeling that she's going through… just getting connected and being able to hear other mums, I think that would be good for her.” [Parent 3]

These connections were seen to provide practical support such as sharing strategies or help with housework and childcare, which was described as particularly crucial when parental mental health was poor. However, participants expressed how social connection, such as support groups, could have downsides including parents feeling shame or anxiety. Clinicians stressed their need for working in specialised, collaborative teams of peers to enhance confidence, shared learning and work quality.

“As a clinician and working in this particular area if it was kind of specific… working within a team where we're all on the same page and we're able to kind of help and support one another… that's how I'd build on my confidence.” [Clinician 1]

3.2.3. Theme 3: Practical and Personalised Knowledge

Participants expressed that parents need program content that extends beyond information to provide practical and personalised guidance.

Practical Knowledge

Participants, including clinicians drawing on personal experience, emphasised that parents would benefit from concrete examples of how to use strategies and plans, reminders and goal setting to translate knowledge into action. Practicing skills through role-playing with others and trying strategies with children was seen as essential. Participants highlighted that parents need practical steps and support in problem solving barriers. Parents and clinical leads suggested that this be supported by a clinician who could follow up on issues, answer questions and help parents consolidate and implement strategies.

“They might have read something and they were like, ‘I'm not really understanding how to put this into practice… I've read it, but I'm not sure how to implement it’. So maybe the clinician can assist with that.” [Clinical Lead 2]

Personalised Knowledge

Participants clarified that knowledge is effective only when tailored and contextualised to each parent, as every family is different. All participants described personalisation as requiring understanding of each parent’s unique context, mental health challenges and barriers, then adapting strategies to be relevant and useful. Parents suggested that clinicians could support this through recommending modules and customising strategies based on each parent’s changing needs.

“That kind of personalised process… to understand what a parenting program means to her... Or maybe… she doesn't have the time, so maybe the counsellor can help her prioritise… that would be hard for [parent] to do on her own, and it's probably not a component of the parenting program itself.” [Parent 5]

Parents and service providers also highlighted the need for content that is culturally inclusive and specific to parenting with mental health challenges, to ensure parents can see their family context in the program.

3.2.4. Theme 4: Parent-Led Empowerment

All participants emphasised the importance of supporting parent empowerment and autonomy through helping parents feel more capable, confident and in control.

Guided Autonomy

Participants identified autonomy as central to empowering parents in their mental health and parenting, whilst acknowledging that parents would need professionals to support this autonomy through guidance and encouragement. It was seen as essential that this support was collaborative to help parents feel in control and guided rather than directed. Online and clinician support was viewed as most powerful when it respected parent ideas and helped them reflect, build on existing knowledge and generate their own solutions. Participants stressed the need for clinicians to adopt a parent-centred approach led by parent preferences and priorities, consistent with the service’s client-led model.

“Sometimes people, they know what's the best to do, but… don't have the capacity. So I definitely agree with… not to tell her what to do. I would like to ask her… what do you think we can do in this situation… what's your suggestion?” [Parent 4]

Parent Self-Efficacy and Self-Worth

All participants, including clinicians with lived experience, emphasised the need to support parent self-efficacy and self-esteem to counter feelings of guilt, shame, inadequacy and self-blame. Encouraging parents to embrace ‘good enough’ parenting, set realistic goals and approach tasks one step at a time were viewed as crucial for building self-worth and a sense of achievement. Participants described the value of reinforcing parents’ existing strengths and acknowledging incremental progress to boost parent confidence and motivation to keep going. Clinicians were identified as playing a key role in this.

“Helping the parents to look… at the positives first… working within the strength-based model. And helping parents to identify their own character strengths so they can use that to… build on their parenting.” [Clinician 3]

3.2.5. Theme 5: Accessible and Integrated Support

Parents and service providers emphasised that program delivery must be accessible, flexible, and seamlessly embedded into everyday life and clinical practice

Low-Burden Accessibility

All participants valued a simple, engaging and adaptable program to maximise usability. A mix of written, visual and interactive delivery was perceived as important for maintaining parent engagement and catering to different learning styles. Participants asked for easy to follow, plain language content to accommodate parents with diverse literacy levels or reduced cognitive functioning. They also recommended minimising burden for parents with limited time and fluctuating symptoms by dividing the program into short sections with breaks, providing reminders and ensuring flexibility to access the program at any time of day and to pause and re-engage as needed.

“It can't be too long… parents might have things they need to organise for the kids… Breaking it down into smaller portions so that it's achievable… because they could be tired and they may not be able to concentrate for too long.” [Parent 8]

Participants highlighted the importance of the program being low cost and offering user-friendly technology accessible across devices, to suit parents with different income and technology resources as well as parents and clinicians with varying digital skills.

Seamless Integration

Participants highlighted that effective program delivery depends on seamless integration into routine clinical practice, reflecting their view that mental health and parenting are closely intertwined. A self-directed program complemented by clinician check-ins during existing sessions was suggested to minimise clinician burden, leverage existing clinician skills and extend support beyond limited clinician contact.

“Can kind of check in with people during that session… if it's within… that timeframe, yes. But outside of that, it might be a challenge because of the other demands of clients.” [Clinician 1]

Service providers emphasised the need to use case-coordination, secondary consultation or referrals to specialists when parent needs exceed expertise or service scope, which parents also valued. Clinician training was recommended to be brief and flexible including ensuring staff can learn at their own pace, revisit content and access optional extra resources to accommodate diverse clinician needs and schedules. While clinicians suggested supervision from parenting specialists, clinical leads considered this infeasible and proposed that this support be provided by existing supervisors instead.

3.2.6. Intervention Design

The research team synthesised the above findings and translated the design considerations into relevant design features for the intended adapted parenting program. Features were designed and refined iteratively, drawing on relevant literature, features from the original PiP Kids program and multidisciplinary meetings with psychology and human-computer interaction researchers from the team. For example, the subtheme ‘Parent self-efficacy and self-worth’ was conceptualised as including strengths-based and encouraging language, achievable strategies and progress indicators within each module, among other features. All concretised features are presented in

Supplementary Table S4 alongside the theme and subtheme they were designed to address. Broadly, the adapted parenting program, named ‘Partners in Parenting Kids Parental Mental Health (PiP Kids PMH; herein ‘the program’), is intended to include four key components and a clinician training package. See

Table 1 for a description of the main components of the program.

4. Phase 2 Methods and Results: Develop and Validate the Initial Prototype Design

4.1. Phase 2 Methods

4.1.1. Participants

Participants included the same parents (n=8) and all service providers from Phase 1, except one social worker clinician who had left the collaborating service (n=2 clinical leads; n=4 clinicians).

4.1.2. Data Collection

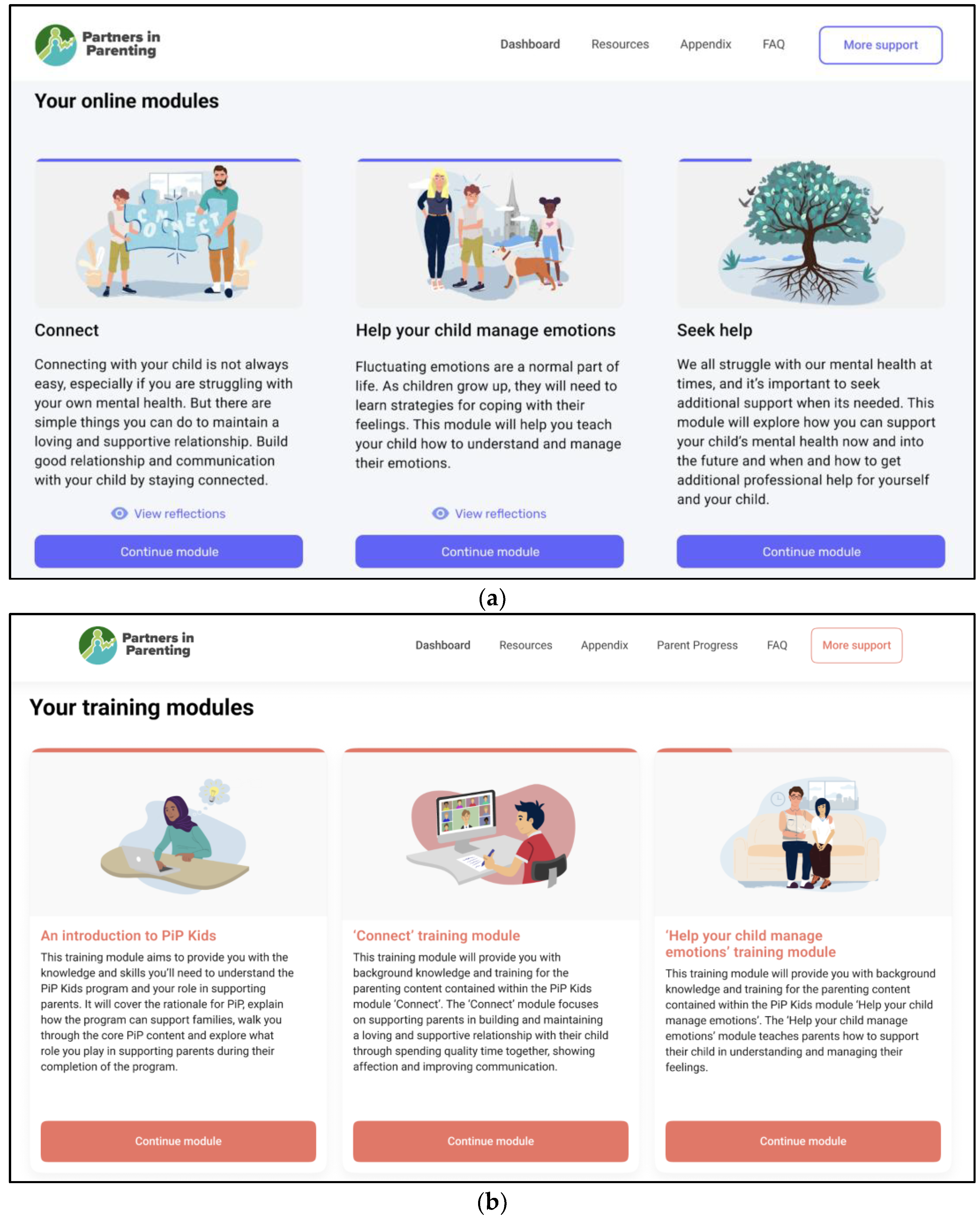

Based on Phase 1 findings, the research team developed an initial prototype of the adapted parenting program and associated clinician training, each demonstrating the dashboard and two example modules.

Figure 4 shows the online dashboard pages from the initial parenting program prototype and the accompanying training modules. Phase 2 workshops aimed to validate and refine the program design with parents and service providers. Each parent and service provider participated in one workshop during this phase. All parents attended individual workshops due to difficulties scheduling group workshops and service providers participated in either individual or group sessions. Workshops were conducted via Zoom with audio and video recording and lasted 2 hours (with a 5–10-minute break).

Workshops explored parent and service provider feedback on the preliminary Phase 1 design considerations to sense-check whether these reflected their needs and preferences. Feedback was then sought on the broad program design, including its four main components. Parents and service providers were then given access to the online component of the initial program prototype and encouraged to share their feedback aloud. Service providers were also provided with access to a prototype of the online component of the clinician training in this way. Follow up questions explored participant preferences (e.g., what they liked, what they would change and how design features should be structured and delivered) and how well the program addressed the design considerations.

4.1.3. Data Analysis

Interviews were transcribed automatically via Zoom or by a third-party transcription service and checked by the first author for accuracy. Transcribed data were coded with the support of NVivo software, using Braun and Clarke’s six-phase reflexive thematic analysis approach [

68,

69]. Data were analysed deductively using the five design considerations from Phase 1, as the purpose of this phase was to sense-check these themes and validate if and how the initial prototype met these needs. Additional themes were identified inductively to capture novel insights beyond these pre-defined themes.

4.2. Phase 2 Results

Participants frequently reiterated findings from Phase 1, confirming the relevance of these for the program. For this reason, a summary of how well the initial prototype met the design considerations is provided in Supplementary File S5, with illustrative quotes. A novel theme was also developed highlighting the program’s role in facilitating communication between parents and clinicians, and considerations for how this could occur. Results below outline this new theme as well as suggestions for improvement according to each design consideration.

4.2.1. Building Readiness for Parenting Support

Suggestions for the next program iteration included: a quick exit button for family violence, extra mental health resources and embedding helpline numbers directly within module pages for immediate support. Participants also suggested more clearly specifying for parents the program’s purpose, better highlighting the benefits of parent and clinician reflection questions and introducing the program in terms of its potential benefits to parental mental health.

4.2.2. Emotional and Social Support

Suggestions for the next program iteration included: more explicitly acknowledging parenting is difficult, additional 24/7 support options, more lived experience examples, additional prompts to reach out to support networks and opportunities for parents to connect with their peers. Clinicians suggested that training should include ongoing group supervision, and clearly specify that clinician reflections are designed to be shared with other clinicians in the peer workshop.

4.2.3. Practical and Personalised Knowledge

Suggestions for the next program iteration included: pictures of real people, space for parents to note personalised goals and answer goal prompts and more examples of how to apply strategies. Participants also recommended more goal options, a search function, a personalised dashboard picture, and extra opportunities for parents to indicate strategies relevant to them. Other suggestions included adding more instances of contextualising content to parenting with mental health challenges, more examples for fathers and ensuring images include a balanced representation of different cultures.

4.2.4. Parent-Led Empowerment

Suggestions for the next program iteration included: space for parents to note extra comments or record their existing skills, while also ensuring parents have control over whether they share goals and reflections with clinicians. Participants recommended increasing and bolding encouraging and self-compassionate language, removing some language that may be deficit focused, framing quizzes as low-pressure and providing more obvious progress indicators including opportunities to track incremental goal progress.

4.2.5. Accessible and Integrated Support

Suggestions for the next program iteration included: improving readability and digestibility of content, minimising open text responses, more audio including the option for text to be read aloud, versions in other languages and encouraging parents to download content pages. They also suggested making the program more interesting by including videos and more images, colours and activities. Parents recommended providing estimates of how long modules and goals might take and acknowledging financial concerns as a potential challenge faced by parents. Clinical leads recommended parents be given a timeframe for program completion to increase likelihood of finishing. Clinicians also asked for a supervisor with parenting expertise and the option to contact parents to check-in on their progress between sessions.

4.2.6. Emergent Theme: Bridge for Communication

Participants described how the program was able to facilitate communication between parents and clinicians. The end-of-module reflection questions were seen as helpful for starting and guiding sessions by communicating parent needs to clinicians. This feature was seen as an efficient way for parents to express priorities or sensitive issues that might be difficult to say aloud, though it was noted that these should not replace therapeutic conversation. Participants described the benefit of parents completing reflections while they were in the mindset of the program to help them think through their needs and record points to discuss in sessions. Parents and clinicians appreciated clinicians having direct dashboard access to parent progress and reflections to facilitate easy communication, and clinicians’ ability to review these in advance for session preparation.

“Some people still find it hard to talk face-to-face… so I feel like this is really good because you're getting this information to them. It's like, when you fill out a questionnaire, and you almost feel anonymous… cause you're not saying it. It's another way of communicating without having to speak.” [Parent 7]

Suggestions for the next iteration of the program included: more frequent reminders within content to speak with clinicians and extra space for parents to note comments or questions to share. Clinical leads raised issues with clinicians having their own dashboard access to parent progress and reflections including concerns about confidentiality, data security if a clinician or parent leaves the service and added administrative burden. They concluded that parents should instead share their progress and reflections with clinicians directly unless logistical issues with the clinician dashboard can be resolved.

4.2.7. Intervention Refinements

The research team refined the design of the initial prototype based on the Phase 2 findings. For example, sharing each module’s goals and reflection responses was made optional to give parents control over if and when they share this information with their clinician or other support people.

Supplementary Table S6 provides a full outline of all prototype refinements as well as additional considerations for future iterations of the program beyond the scope of the current study.

As only a limited number of modules could be developed for this first iteration, the topics

‘Talking with children about parental mental health’ and

‘Showing affection and acceptance’ were chosen, with information on self-care and help seeking integrated throughout these modules. These topics were informed by Phase 1 and 2 findings, our systematic review comparing parental factors between parents with and without anxiety and/or depression, [

53] and a broader literature review of parenting domains linked to parental mental health and child outcomes [

5,

49,

52,

71,

72,

73].

Evidence-based content for the

‘Showing affection and acceptance’ module was retained from the original PiP Kids program, with features and wording adapted for contextualisation to parenting with mental health challenges. Content for the

‘Talking with children about parental mental health’ topic was divided into two modules 1)

Getting ready for conversations and 2)

Having conversations, to keep each module manageable for parents. This new content was developed by reviewing existing resources on the topic [

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79]. The content and its presentation were comprehensively reviewed by research team members with expertise in psychology, parenting and parental mental health. Modules were initially designed to take 10-15 minutes to complete, however, incorporating all design considerations while including evidence-based content required extending the duration of modules to approximately 15-25 minutes. Supplementary File S7 provides images of the refined parenting program prototype, including the dashboard and selected module pages.

5. Phase 3 Methods and Results: Deliver the Refined Prototype

5.1. Phase 3 Methods

5.1.1. Participants

Recruitment followed the same methods as Phase 1 and parents from earlier phases were also invited to participate. Six parents expressed interest, including four from Phases 1 and 2. Five parents consented, including one newly recruited parent and the four returning participants. One of the returning participants withdrew due to competing life circumstances and another was lost to follow up after partially completing the prototype.

In total, three parents completed all three prototype modules and the interview, and their data were included for analysis. Parents were mothers (n=2) and a grandmother (n=1) aged 41-56 years (M=47). The newly recruited parent was seeking mental health support at the collaborating health service, while the other two parents had lived experience of accessing support in the broader community within the past six months. Parents’ self-reported mental health challenges included high stress (n=3), anxiety (n=2), trauma (n=2) and depression (n=1).

Supplementary Table S8 presents further demographic characteristics of the Phase 3 parent participants.

5.1.2. Data Collection

Phase 3 focused on piloting the refined prototype with parents to explore its acceptability. For this study, only the online module component of the refined prototype was piloted, not the clinician-support component or clinician training. A staged approach was considered valuable given the newly co-designed content and program features. This online-only trial served as a logical first step in evaluating the modules before integrating them with clinician support.

Parents completed a demographic questionnaire via REDCap before commencing the refined prototype. Parents were encouraged to complete one module per week, with the first author monitoring progress and sending weekly, personalised reminder emails based on each parent’s goals and progress. Approximately one month after commencing the prototype, parents completed a 1-hour semi-structured feedback interview. Interviews were conducted using a guide adapted from prior related research [

51,

80,

81] to explore prototype acceptability and adaptations for the next iteration of the program. The interview schedule (Supplementary File S9) was adapted from the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability (TFA) questionnaire, a theory-informed approach to evaluating acceptability of healthcare interventions [

82,

83]. Open questions asking parents for their perspectives on a clinician-support component were also included. Interviews were conducted one-on-one via Zoom with audio recording. Parents were reimbursed with a

$35 gift card for the interview and an additional

$10 for each online parenting module completed.

5.1.3. Data Analysis

Interview recordings were automatically transcribed by Zoom and manually cleaned by the research team. Parents were invited to review their transcript for alignment with their experience of the interview [

84], however, no parents chose to review their transcript. Transcripts were analysed with the support of NVivo using a reflexive thematic analysis approach [

68,

69]. Themes were identified deductively using the seven constructs of the TFA [

82,

83], with subthemes developed inductively, including those not covered by the TFA but still relevant to acceptability.

5.2. Phase 3 Results

Themes reflecting acceptability of the refined prototype were developed using the seven TFA constructs, with subthemes capturing specific contributors to acceptability and suggestions for improvement.

Table 2 defines the TFA constructs and presents the subthemes with illustrative quotes.

5.2.1. Affective Attitude

Parents expressed a positive experience with the program including its self-directed, evidence-based content and optional further reading. They found it accessible and user-friendly with clear language, summaries, audio and images to support understanding. The simple technology was appreciated, but parents recommended adding the ability to enlarge text and easily return to previous pages. Parents found the program engaging and interactive due to its varied text and visuals, clickable boxes and quizzes. However, they mentioned that some audio recordings were delivered in an unnatural tone and that interactive boxes could be more clearly indicated. The program was described as supportive through non-judgmental and non-directive language, calming colours, encouraging statements, and progress indicators, but parents suggested adding encouraging music when parents’ complete goals or quizzes.

5.2.2. Intervention Coherence

While parents generally had a good understanding of the program, they were occasionally uncertain about program instructions such as whether some sections were information or required a response. They suggested including a video to introduce how to use the program as written instructions may not be accessible for everyone. There was also some uncertainty about the program’s scope and users as some parents expected extra modules and were unsure about who the program was for and how it would be accessed.

5.2.3. Perceived Effectiveness

Parents reported that the program was effective in strengthening their self-efficacy and self-belief by reinforcing their existing strengths. Regarding improving parenting, parents said that reflective activities and practical suggestions prompted them to think about their parenting and make small adjustments. However, they stated that the end-of-module reflection questions did not effectively encourage them to seek additional support as intended. Parents described the content as familiar, noting that while it included some new information, its main value was in reminding them of what they already knew. Although this provided some helpful tips, parents suggested it may be more beneficial for new parents or those less familiar with the content. To further support reflection and practice, parents suggested including more topics, space for open reflection and more quizzes.

5.2.4. Ethicality

Parents appreciated the program’s personalisation features, such as being able to select strategies relevant and achievable for them, though they noted some limitations. They mentioned that content was not always catered to individual circumstances such as low literacy, neurodivergence or unique family contexts. Parents suggested ways to further tailor the program such as uploading their own avatar, including space to note reflections specific to their situation, and adding content on co-parenting and financial concerns. Parents also valued that the program was inclusive and represented diverse cultures in images, but they recommended depicting a broader range of family types and incorporating parenting examples from other cultures.

5.2.5. Burden

Parents had different experiences with the time and cognitive effort required for the program. They mentioned that it took around an hour to finish a module which was longer than intended. Some found this manageable as they appreciated the available resources, but others found the text heavy content demanding of their limited time and energy. Reading was described as particularly difficult when struggling with mental health and all parents preferred audio or video options. Parents recommended shorter modules, less information displayed at once and faster page transitions. Although the self-directed modules allowed parents to fit the program flexibly around competing demands, they said that busy schedules still interrupted progress. Parents appreciated that all modules were available at once to allow them to complete content when it suited them. They found email reminders helpful but suggested adding optional text message reminders.

5.2.6. Opportunity Costs

All parents reported that participating in the program was worthwhile and required no sacrifices beyond time and internet access. However, one parent noted that internet access might be a challenge for some families.

5.2.7. Self-Efficacy in Completing Program

Parents reported feeling confident they would complete the program, although uncertain how long it might take. Open activities, such as some end-of-module questions were perceived as difficult due to the need to put responses into words. Parents suggested more tick boxes or multiple-choice activities to make completion easier. Goals were seen as helpful and achievable but applying them in daily life could be challenging given the need to problem solve. Parents appreciated the reminders to complete goals but suggested extra reminders and the ability to track goals on the dashboard.

5.2.8. Additional Acceptability Sub-Themes

Parents valued that the program normalised parenting and mental health challenges and emphasised that no parent is perfect. They reinforced the importance of incorporating human support and connection, noting the benefit of flexible access to a clinician for debriefing, accountability, encouragement, tailoring and problem solving. Peer based social opportunities, directly clickable helpline numbers and a quick enquiry box were also suggested. One parent suggested incorporating opportunities for parents to receive feedback from their children on their parenting.

6. Discussion

This co-design study aimed to adapt an evidence-based digital parenting program (PiP Kids) for implementation in an existing adult mental health service, to support parents seeking mental health care. Triangulation of findings across parents, clinicians and clinical leads provided a multifaceted understanding of end-user needs, strengthened by the lived experience of several clinicians. The main findings identified from Phase 1 and reinforced in Phase 2 underpinned design considerations regarding the needs and preferences of parents and service providers. These design considerations are discussed in detail below with reference to existing literature and future research directions. Acceptability findings from Phase 3 are integrated into the themes where relevant.

6.1. Building Parent and Clinician Readiness for Parenting Support

The first design consideration identified several factors impacting parent and clinician readiness for parenting support, including parent wellbeing and safety, clinician training, and both groups understanding the purpose and value of the program. The findings regarding building parents’ readiness align with prior research emphasising that the immediate wellbeing of families should be addressed before they can engage in parenting support, particularly in contexts involving risk, safety concerns or family violence [

37]. Managing parental mental and physical health and engaging in self-care have also been identified as foundational for parenting capacity [

18,

85]. Consistent with prior research, participants viewed mental health treatment as the main role of the adult mental health service, with clinicians extending to parenting when it helped support the parent’s mental health goals or after acute concerns were addressed [

26,

31]. This suggests that parenting programs integrated within adult mental health services should prioritise parental mental health first, either by allowing treatment before the program begins or by supporting the parent’s mental health goals directly.

Additionally, our results suggest that a thorough introduction to the program, such as via an initial video, may be particularly valuable for parents with mental health challenges, as this was expressed across all three phases. This has also been found in previous research, with suggestions that setting clear expectations and describing benefits of programs can help ease parent anxiety, support engagement, create stability and minimise uncertainty that has occurred across this and other programs for parents with mental health challenges [

25,

37]. We also found that parents may benefit from clinicians supporting this introduction, similar to prior research [

37].

Findings regarding clinician readiness suggested that clinicians appreciated that the program provided them with not just program training but also brief refreshers on parenting content and how their existing skills translate to parenting support. Since practitioner confidence and skills related to parenting are key factors in the likelihood of family-focused practice [

86], this approach may support successful implementation into a range of settings, since it does not require extensive parenting specific training [

31]. Together, these findings suggest that integration of parenting support into adult mental health care should begin with a period of building readiness and addressing foundational factors with both parents and clinicians.

6.2. Facilitating Emotional, Social and Peer Support for Parents and Clinicians

The second design consideration suggested that for parents, normalising, non-judgmental emotional support and social connection is crucial, whereas for clinicians, professional peer support is required. In particular, acceptability feedback from parents indicated that they found the supportive, non-judgmental language of the program helpful. Consistent with existing literature, parenting was described as a potentially sensitive topic especially for parents with mental health challenges who often fear being judged as incompetent, which can act as a barrier to help-seeking [

85,

87]. This highlighted the importance of validating program content and empathetic emotional support from clinicians [

65,

88]. Specifically, participants emphasised that parenting-related emotional support provided in an existing parent-clinician relationship would be particularly beneficial. This aligns with research suggesting the importance of establishing a trusting relationship prior to introducing parenting programs, to create a safe, non-critical, reflective environment for parents [

37,

89].

Parents also valued that the program encouraged social support from family and friends beyond the therapeutic alliance. This finding aligns with prior studies suggesting that parents benefit from social connection as it provides emotional support, shared parenting strategies, and support with practical parenting tasks [

18,

90]. Participants across all phases consistently reiterated the potential benefits of peer support from other parents with mental health challenges, which has been described by parents and clinicians previously [

23,

37,

91]. Likely benefits include reduced social isolation as well as normalisation, reassurance and learning from others in similar situations [

25,

87]. However, consistent with earlier findings [

87,

90], some participants described the potential negative effects of peer groups such as anxiety, shame or reluctance to share personal information. It may be beneficial for future studies to investigate how to leverage existing technology to design peer support communities that enable the benefits of peer support while minimising the concerns articulated by participants.

Peer support was also valued by clinicians as they highlighted the importance of connection with other clinicians delivering the program, similar to previous work [

37]. Clinicians suggested that ongoing group supervision would be more valuable than a one-off workshop, however, clinical leads indicated this may be challenging in their busy health service. Future studies could explore implementation options for feasible group supervision such as having a brief dedicated peer supervision or an embedded approach where parenting-related discussions are integrated within existing group supervision to reduce time demands on clinicians and services.

6.3. Providing Parents with Practical and Personalised Parenting Knowledge

The third design consideration highlighted the importance of providing parenting knowledge that is practical, relevant and tailored to each parent’s unique family, context and mental health challenges to help them implement strategies that work for them. This aligns with previous findings emphasising the benefit of practical strategies [

85], clinician modelling [

37], adapting content for each family [

18,

23], and support with problem solving implementation of strategies [

55,

92]. Goals were also valued for helping parents action changes, consistent with research identifying goal setting as a key process in both parenting and mental health recovery [

24]. The written summaries of each counselling session were highlighted as a particularly helpful aspect for supporting implementation of learned strategies, but the usefulness of this in practice will need to be trialled in future when piloting the clinician-support component. In Phase 3, parents reiterated the helpfulness of the program’s practical tips, but noted that much of the content felt familiar, suggesting we may have reached parents with relatively high parenting literacy. This acceptability data suggested that parents’ main challenges were less about gaining parenting information, but more in relation to applying the content to their unique circumstances and putting strategies into action in their life. Together, these findings suggest that even when content is easy to understand, making changes in parenting is the difficult part, especially for parents with mental health challenges [

23]. This indicates a need for applied and personalised support beyond what a fully self-directed program can provide. Findings echo the potential benefit of clinician-support provided by the parent’s mental health clinician who already has the context of the parent’s family and mental health challenges for tailoring strategies [

19]

Additionally, participants liked the program’s consistent focus specifically on parenting in the context of mental health issues, which has been shown to be crucial to program engagement and acceptability for these parents [

23,

54]. For example, we and other studies have found the need for parenting programs to support parents in talking with their children about parental mental health [

54,

93], given children’s desire to receive this information from their parents, and parents’ uncertainty about how to have these conversations [

58,

94]. These findings are consistent with past research which suggests that generic parenting programs that fail to address parental mental health may be insufficient for parents with mental health concerns [

23,

46]. Finally, participants highlighted the importance of ensuring content reflects diverse family types and cultures, consistent with prior calls for inclusive and culturally sensitive program design [

31,

55].

6.4. Encouraging Parent-Led Empowerment for Parents

The fourth design consideration demonstrated the importance of parents having autonomy and control while receiving the strengths-based support they need. Parents and service providers described the value of the program’s self-directed content for encouraging parent autonomy and independence, similar to prior work [

37]; but they also reinforced the need for adjunct clinician support of such autonomy. Specifically, our acceptability data indicated that fully self-directed programs may be less suitable for parents with mental health issues unless some degree of human support and encouragement is provided. These findings are consistent with emerging evidence suggesting that self-directed parenting programs may be acceptable for parents with mental health issues, but guidance is needed due to the potential impact of mental health symptoms on parents’ capacity to engage [

37,

55]. Incorporating clinician support to scaffold parents’ completion of an autonomous, self-directed program may not only enhance program engagement but also outcomes for parents and families. [

95]. Additionally, consistent with previous findings [

31,

85], we found the need for this clinician support to take a collaborative, parent-led approach to promote parent autonomy and empowerment. Parents have reported positive experiences when given the opportunity to participate in decisions about their care [

96], reinforcing the importance of this finding.

Participants also emphasised the value of strengths-based support that acknowledges parents’ existing parenting strengths and fosters confidence in their parenting abilities. This aligns with previous evidence suggesting the importance of working with parents to promote a positive identity related to parenting [

18,

54,

97]. To do this, findings echoed the need to promote self-compassion and acceptance of imperfection to help parents feel competent as parents and people [

18,

25]. Participants appreciated the role of clinicians in promoting parent confidence and encouraging them to make progress with the program, consistent with prior work [

37,

85]. This focus on empowerment seems especially important given that feelings of inadequacy are common among parents with mental health challenges [

90]. Acceptability data provided initial support that the program effectively targeted parental self-efficacy in parenting, similar to another study of a guided self-help parenting intervention [

55]. Importantly, promoting parents’ self-efficacy, positive sense of self, agency and independent problem-solving capacity have been identified as key influences on parenting changes [

98] and mental health recovery [

99], highlighting the value of interventions that target these aspects.

6.5. Embedding Accessible and Integrated Support into Existing Practices

The final design consideration highlighted that program delivery must be accessible and integrated into the everyday life of parents and clinicians. Flexibility for parents to disengage and re-engage was valued to accommodate fluctuating symptoms and competing life demands, similar to prior suggestions for parents with mental health challenges [

100]. Parents found features that reduced cognitive burden to be helpful, such as reminders, summaries and multiple-choice questions. This is not surprising, given the barriers parents with mental health challenges face when engaging with parenting programs including fluctuating mood, competing priorities and memory difficulties [

37]. Acceptability data suggested that parents generally found the program to be clear, engaging, user-friendly and interactive. However, our findings and those of others suggest that the accessibility of content could be improved by minimising text, presenting content visually or in videos, and making the program available in other languages [

37,

43,

55].

Parents in Phase 3 suggested making the modules shorter, similar to findings that brief interventions are particularly beneficial for parents facing social disadvantage [

39]. Notably, attempts were made to break the

‘Talking with children’ module into two parts to make it more cognitively manageable, however parents suggested that further breaking down modules into even smaller chunks would be ideal. Furthermore, parents stated that modules took them approximately one hour to complete, despite an intended design of 15-25 minutes, based on the original PiP Kids program. This discrepancy suggests that parents with mental health challenges may require additional time for module completion due to factors such as difficulties with mental health symptoms, reading comprehension, engagement or digital literacy. Parents reported confidence in their ability to complete modules eventually, however, many said that the largely self-directed program may not be appropriate for parents with low English proficiency, limited technology literacy or reading difficulties unless extra support is available to help with completing modules. Future iterations of the adapted program should explore ways to balance evidence-based PiP Kids content with parent preferences for brevity, such as by implementing suggestions including videos or bite-sized modules that were not feasible in the current project.

The need to embed the program into existing mental health practice was also emphasised, to ensure the program becomes a feasible and sustainable part of routine care. Our findings align with existing literature suggesting that parenting is closely intertwined with parent mental health recovery, providing challenging and positive experiences, hope and motivation [

65,

96]. Parenting is a central factor in the lives of many parents, suggesting the need for parenting support to be integrated within individual mental health care, not isolated in a separate service [

31,

85]. This is supported by evidence that parents experience positive outcomes when parenting is included in mental health treatment [

32,

96] and that interventions that integrate parenting with mental health support may best serve parents with mental health issues [

21]. Notably, parental mental health and parenting support are often delivered separately, with parents experiencing frustration when their parenting is not addressed by psychologists and they have to repeat themselves to multiple clinicians [

96,

101]. Our technology-assisted adaptation of PiP Kids helps address this gap by embedding digital parenting support within existing mental health service provision. This approach not only reduces the need for parents to engage with multiple providers but also allows clinicians to provide parenting support without delivering parenting content, unlike face-to-face parenting programs that often rely on clinician delivery [

23,

25]. A technology-assisted program such as this is thus likely to be appropriate in community mental health settings where clinicians often manage large caseloads, limited number of sessions and competing demands [

32,

38].

Importantly, clinicians indicated that the co-designed program aligned with existing service practices, including using existing clinician skills and referring parents to other services when support needs fall outside scope. These referrals are likely to be especially important for parents with mental health issues who often present with complex needs, including child mental health problems and socioeconomic disadvantage [

102,

103]. Additionally, clinicians differed in their confidence levels regarding parenting, suggesting the need for clinician training that is flexible in not only timing but also content. Our self-directed clinician training with optional additional resources seemed to be well regarded for addressing these needs. Overall, these findings suggest the need for there to be clear compatibility between parenting programs and service needs for successful integration of programs into routine practice.

6.6. Creating a Bridge for Communication Between Parents and Clinicians

A novel finding of this study was the potential role of the program in facilitating communication between parents and clinicians. Previous research has shown that vignettes, written resources or other program components can be useful for starting difficult parenting conversations [

26,

32]. Our findings extend this by suggesting that a technology-assisted parenting program can serve as a structured communication mechanism embedded within the service model, allowing parents to regularly articulate their parenting needs and experiences. However, preliminary acceptability findings suggest that without integrated clinician support, the end-of-module reflection questions did not encourage parents to communicate their support needs to others. Future research might examine whether the program serves this communication function when clinician support is incorporated.

Moreover, the clinician dashboard, which allows clinicians to view parent progress and end-of-module reflections, was seen by parents and clinicians to have potential value for streamlining communication. However, clinical leads identified practical challenges for implementation including confidentiality concerns and logistical issues when clinicians or parents leave the service. While identifying design considerations and assessing initial acceptability is a critical early step in this research, only these two clinical leads discussed the real-world feasibility of implementing the integrated program design. Thus, future work is needed to further explore how suggestions such as the clinician dashboard could be integrated and to identify facilitators and barriers to implementation of the program in everyday practice.

6.7. Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, although parents had recent lived experience of seeking mental health care, several were not currently in treatment. This may have limited the study sample to parents with stable levels of mental health challenges, but not necessarily parents with current mental health challenges. It may therefore be helpful for future evaluations to trial the program with parents who are all currently accessing mental health support.

Second, recruitment difficulties and dropout affected sample size, consistent with prior research noting problems engaging parents with mental health issues, potentially due to stigma or low energy [

23,

54]. Due to recruitment difficulties, we engaged parents from all over Australia which may not reflect the demographics of the collaborating health service, potentially impacting external validity. Third, we were unable to recruit any fathers or alcohol and other drug (AOD) clinicians from the service, further restricting generalisability. Although the inclusion of only mothers is common in parenting research [

55], it is important to repeat this research with fathers.

Fourth, the collaborating health service already emphasises parenting within its model of care, consistent with the shift in Australia towards family-focused practice [

104]. However, this may not be reflective of other services, for example, less than half of adult mental health clinicians in a study in the United Kingdom worked on parenting with their parent clients [

16]. Future research should explore whether findings differ in countries or services with less family-orientated care.

Lastly, for feasibility reasons, Phase 3 piloted only the online component of the adapted program. Although this precluded exploration of the implementation of the whole program, Phase 3 nonetheless provided valuable preliminary insights into the acceptability of the online modules. Delivering the full intervention including the clinician-support component on a small-scale to assess implementation and clinical outcomes is thus a priority for the next phase of this research.

7. Conclusions

This study provides an in-depth exploration of the needs and preferences of parents seeking mental health support and the service providers who support them when it comes to technology-assisted parenting programs. The identified design considerations indicate the importance of readiness, support, personalisation, practical knowledge, empowerment, accessibility and integration for designing helpful technology-assisted parenting programs for this population. Findings also provide preliminary support for the potential value of adopting a more holistic, family-focused approach that integrates technology-assisted parenting support within adult mental health settings.

Although this study focused specifically on the PiP Kids program within one adult mental health service, the insights and design considerations may have broader implications for any technology-assisted parenting program aimed at supporting parents with mental health challenges. The results highlight the importance of co-designing these interventions with end users to ensure they are acceptable and accommodate parent and service needs. Researchers, clinicians and service developers seeking to design technology-assisted parenting programs for this population or implement interventions within existing mental health settings can consider our findings in their work.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Co-design methods and aims; Table S2: Demographics of Phase 1 participants; Table S3: Themes, subthemes and additional illustrative quotes for Phase 1; Table S4: Concrete features for the initial adapted parenting program; File S5: Summary of Phase 2 findings regarding how well the initial prototype met the design considerations; Table S6: Refinements made to the initial prototype and considerations for future iterations; File S7: Selected images of the refined parenting program prototype; Table S8: Demographics of Phase 3 participants; File S9: Phase 3 parent interview schedule.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B., L.W., J.P.S., P.O., A.R., A.F.J. and M.B.H.Y.; methodology, M.B., L.W., J.P.S., P.O., A.R., A.F.J. and M.B.H.Y.; software, J.P.S., M.L. and J.X.; formal analysis, M.B., L.W. and J.P.S.; investigation, M.B.; resources, S.G., H.V.; data curation, M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.; writing—review and editing, L.W., J.P.S., P.O., A.R., A.F.J., S.G., H.V., M.L., J.X. and M.B.H.Y.; visualization, M.B.; supervision, L.W., P.O., A.R., A.F.J. and M.B.H.Y.; project administration, M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project is affiliated with the Centre of Research Excellence (CRE) in Childhood Adversity and Mental Health, a five-year research program (2019-2023) co-funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and Beyond Blue. The first author is funded by a Research Training Program Scholarship (Monash University) and was awarded a top-up scholarship from the NHMRC Centres of Research Excellence Grant APP1153419 titled ‘Centre of Research Excellence in Childhood Adversity and Associated Depression and Anxiety’. This research was funded by these scholarships.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (ID #35059 approved 19/08/2022 and ID #44564 approved 20/09/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data from this study are not publicly available to protect participant privacy and anonymity. Deidentified summaries of the data are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The research team extend sincere thanks to the parents and service providers involved for generously contributing their time and lived experience. The team also gratefully acknowledges the community health service for supporting and promoting the study. The first author extends gratitude to Olivia Bruce and Sunita Bayyavarapu for co-facilitating workshops, and to the research interns on the team for their contribution to refining artificial intelligence (AI) generated transcripts.

Conflicts of Interest

M.B.H.Y. and A.F.J are co-authors of the Partners in Parenting Kids (PiP Kids) program, which forms the basis of the program examined in this research. They receive no financial benefits from the program or the current study. The authors declare no other conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PaRK |

Parenting Resilient Kids |

| PiP |

Partners in Parenting |

| PTSD |

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder |

| TFA |

Theoretical Framework of Acceptability |

References

- Wolicki, S.B.; Bitsko, R.H.; Cree, R.A.; Danielson, M.L.; Ko, J.Y.; Warner, L.; Robinson, L.R. Mental Health of Parents and Primary Caregivers by Sex and Associated Child Health Indicators. ADV RES SCI 2021, 2, 125–139. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.E.; Lawrence, D.; Perales, F.; Baxter, J.; Zubrick, S.R. Prevalence of Mental Disorders Among Children and Adolescents of Parents with Self-Reported Mental Health Problems. Community Ment Health J 2018, 54, 884–897. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, H.P.; Bilsky, S.A.; Luber, M.J. Parent Anxiety, Child Anxiety, Parental Beliefs about Anxiety, and Parenting Behaviors: Examining Direct and Indirect Associations. J Child Fam Stud 2023, 32, 3419–3429. [CrossRef]

- Vreeland, A.; Gruhn, M.A.; Watson, K.H.; Bettis, A.H.; Compas, B.E.; Forehand, R.; Sullivan, A.D. Parenting in Context: Associations of Parental Depression and Socioeconomic Factors with Parenting Behaviors. J Child Fam Stud 2019, 28, 1124–1133. [CrossRef]

- Christie, H.; Hamilton-Giachritsis, C.; Alves-Costa, F.; Tomlinson, M.; Halligan, S.L. The Impact of Parental Posttraumatic Stress Disorder on Parenting: A Systematic Review. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Engur, B. Parents with Psychosis: Impact on Parenting & Parent-Child Relationship- A Systematic Review. GJARM 2017, 1, 36-40. [CrossRef]