1. Introduction

The last decade has witnessed the introduction of four direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs): dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban. DOACs are prescribed to patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (AF) for the prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and to mitigate the risk of stroke and systemic embolism 1-5. DOACs were developed to overcome the limitations of vitamin K antagonists (VKAs), which had been the only effective oral anticoagulants for over five decades. DOACs, as opposed to VKAs, are intended for fixed-dose administration without requiring routine coagulation monitoring; they also exhibit a quicker onset of action and a reduced propensity for food-drug and drug-drug interactions (DDIs). Additionally, they have demonstrated no inferiority or even superiority to VKAs and are linked to reduced intracranial haemorrhage 1-3, 5. International guidelines have therefore indicated a preference for DOACs as opposed to VKAs 6-8. As a result, anticoagulation therapy underwent a paradigm shift, and DOACs surpassed VKAs in usage 9.

However, research show that DOACs are frequently prescribed inappropriately, which increases the risk of medicines-related harm 10, 11. Furthermore, individuals diagnosed with AF are usually older and present with comorbidities and polypharmacy 6. As a result, a diverse range of healthcare professionals provides care and follow-up for many of these patients. Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation patients is of paramount importance 12, hence anticoagulation must be prescribed appropriately, and the patient must adhere to their prescribed medication regimen 13. Assessing and enhancing the proper use of anticoagulants is crucial for optimal care of patients with atrial fibrillation, and this responsibility falls on several healthcare providers, including physicians and pharmacists 14, 15. The integrated management of patients undergoing anticoagulant therapy, which includes collaborative decision making and a structured multidisciplinary approach, is recommended by international guidelines 6. This integrated care approach in AF has been shown to be associated with decreased cardiovascular hospitalizations and all-cause mortality 16.

A previous review by Generalova et al. revealed that, despite the increasing usage of DOACs globally, there is a lack of evidence on clinicians' perspectives and experiences on DOAC use 17. However, such evidence is crucial, for instance, for the development and implementation of future healthcare strategies that assist various healthcare professionals in fulfilling their responsibility to optimize DOAC utilization. Research into clinicians' and pharmacists' experiences and perspectives on DOAC use in Saudi Arabia and the broader Middle Eastern area is limited. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the perspectives and experiences of physicians and pharmacists practicing in Saudi Arabia who prescribe DOACs and dispense DOAC therapy, respectively.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

A cross-sectional study was undertaken utilizing an online survey instrument. We collected data via Google Forms. Between June and July 2024, the study questionnaire was distributed to primary (community pharmacists, general practitioners [GPs]) and secondary (cardiologists, residents in internal medicine, and hospital pharmacists) healthcare professionals working in Saudi Arabia.

2.2. Study Tool

The survey was adopted from a previous study with slight revisions to improve relevance and comprehensiveness 18. A pilot sample of ten healthcare professionals was used to establish the face and content validity of the questionnaire's draft. Based on piloting feedback, we evaluated the questionnaire to make sure it was easy to read and complete. The goal is to complete it in ten minutes. The questionnaire was structured into four distinct sections. The first section, titled "Current Practice," delved into the respondents' existing practices regarding the use of DOACs. The second section, "Prescribing Behaviour," explored the respondents' habits and behaviours when prescribing DOACs. The third section, "Self-Perceived Knowledge About DOACs," aimed to gauge how respondents view their own understanding and knowledge of DOACs. The last section, "Views and Opinions About DOACs Vs. VKAs," captured the respondents' perspectives and opinions comparing DOACs with VKAs. The survey cover page included a brief information sheet for prospective study participants. All physicians (regardless of medical specialty) are authorized to prescribe DOACs in Saudi Arabia. DOACs are dispensed to hospitalized and ambulatory patients, respectively, by hospital pharmacists and community pharmacists; they are not authorized to prescribe DOACs.

2.3. Recruitment

An email invitation to participate in the online survey was distributed to the cardiology departments of hospitals in Saudi Arabia. Through their department heads, cardiologists were invited to participate in the online survey. The study team contacted the GPs and pharmacists in the following manner: initially, the researchers disseminated the survey link to individuals in their personal network, including friends, family members, coworkers, and neighbours, through popular social media platforms such as Facebook, LinkedIn Twitter, and WhatsApp. These participants were also requested to distribute this survey to colleagues through social media platforms. A reminder email was sent after one week.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

This research was initiated after the ethics approval. The completion of the survey was considered as implied consent.

2.5. Sample Size and Data Analysis

The Saudi Arabian Ministry of Health Portal data for the year 2020 indicated that the aggregate count of medical doctors and pharmacists in Saudi Arabia amounted to 122,865 19. A sample size of 383 was estimated using the Raosoft calculator, considering the population size, a 95% confidence level, and a 5% margin of error. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27. For continuous variables, the data was presented as mean ± standard deviation if they follow a normal distribution or as median (interquartile range) if they do not. Additionally, graphical representation was used to represent the different scenarios.

3. Results

A total of 313 healthcare professionals participated in the survey, including 146 physicians (40 cardiologists, 49 internal medicine residents, and 57 general practitioners) and 167 pharmacists (113 hospital pharmacists and 54 community pharmacists). All characteristics related to the utilisation of Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs) are presented in

Table 1. The results show clear disparities in prescribing and dispensing patterns. Among physicians, 35% of cardiologists, 16.3% of internal medicine residents, and 17.5% of general practitioners reported prescribing DOACs on a weekly basis. Similarly, 23.9% of hospital pharmacists and 16.7% of community pharmacists reported weekly dispensation of these medications.

Apixaban, followed by edoxaban and rivaroxaban, was the most frequently prescribed and dispensed DOAC across all groups, indicating consistent preference among both physicians and pharmacists. The reported frequency of prescribing or dispensing decreased at longer intervals (monthly and annually), particularly among community pharmacists. Furthermore, 98% of respondents reported reducing DOAC doses when clinically indicated, reflecting a high level of awareness regarding dose adjustment practices.

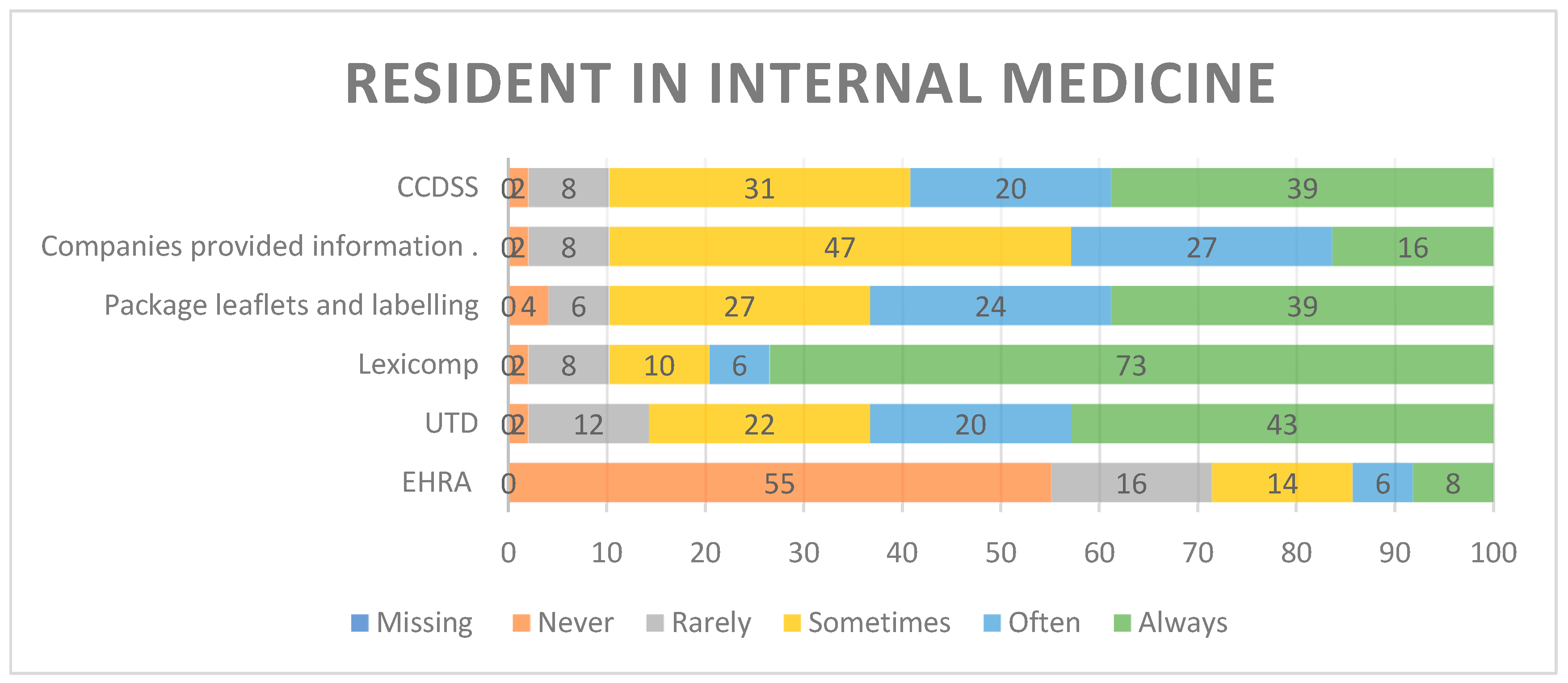

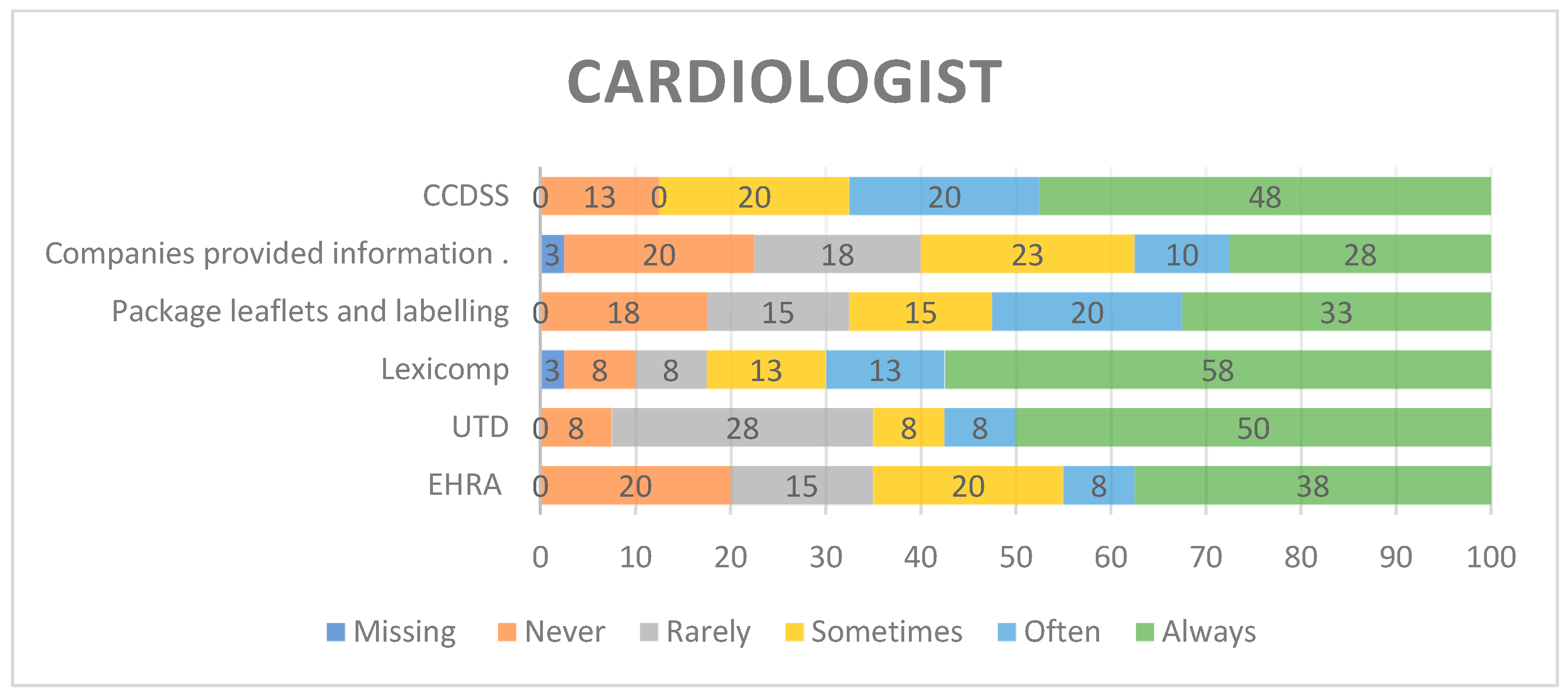

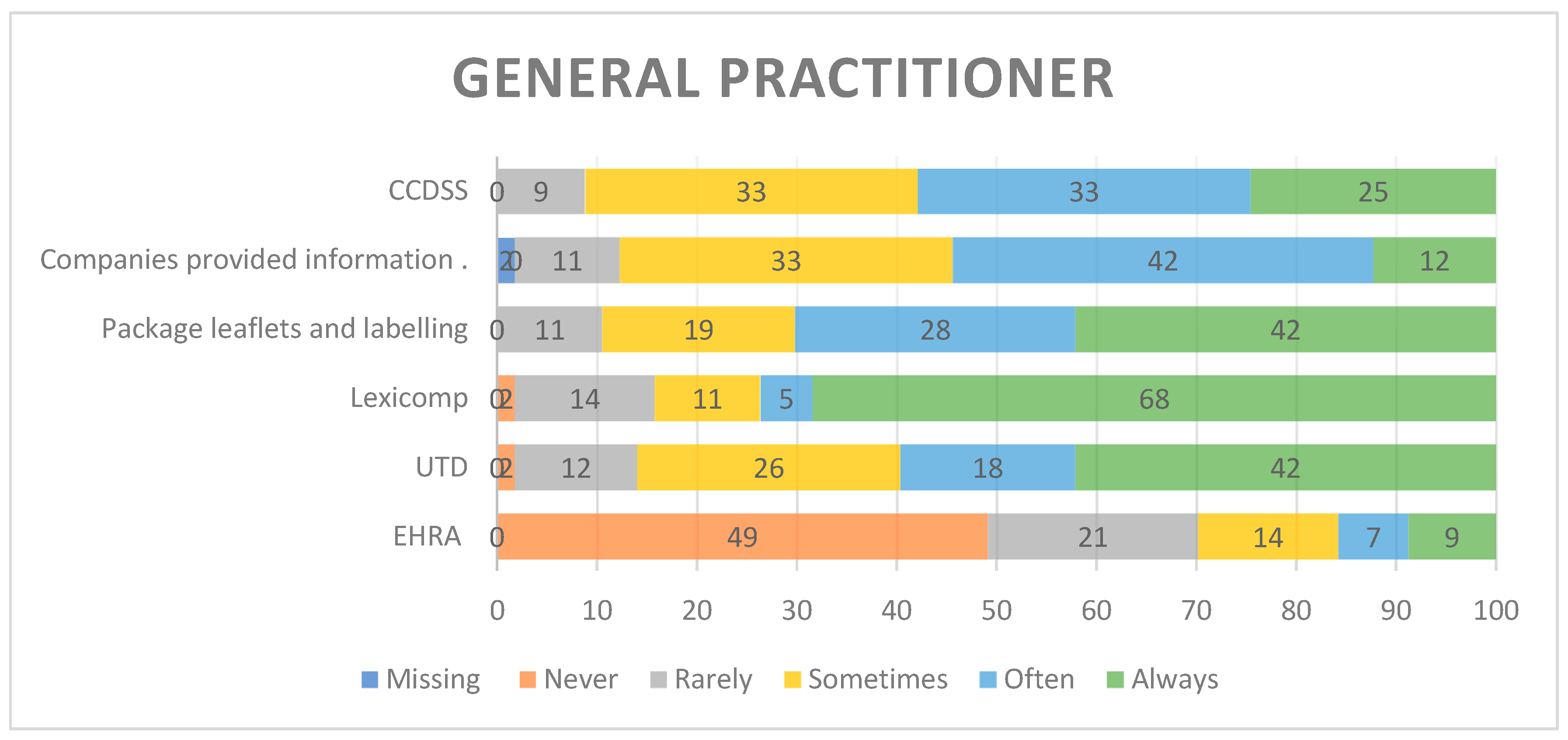

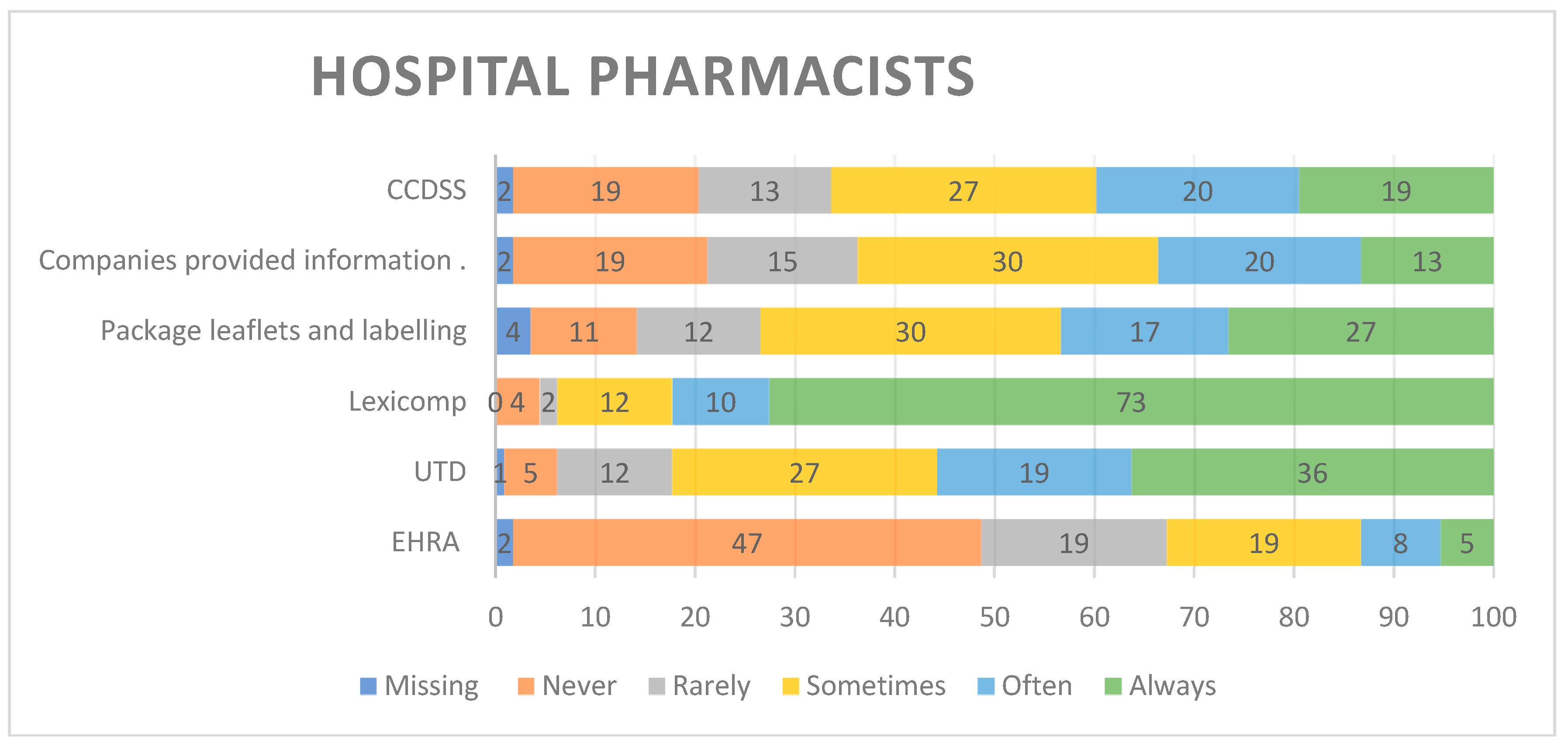

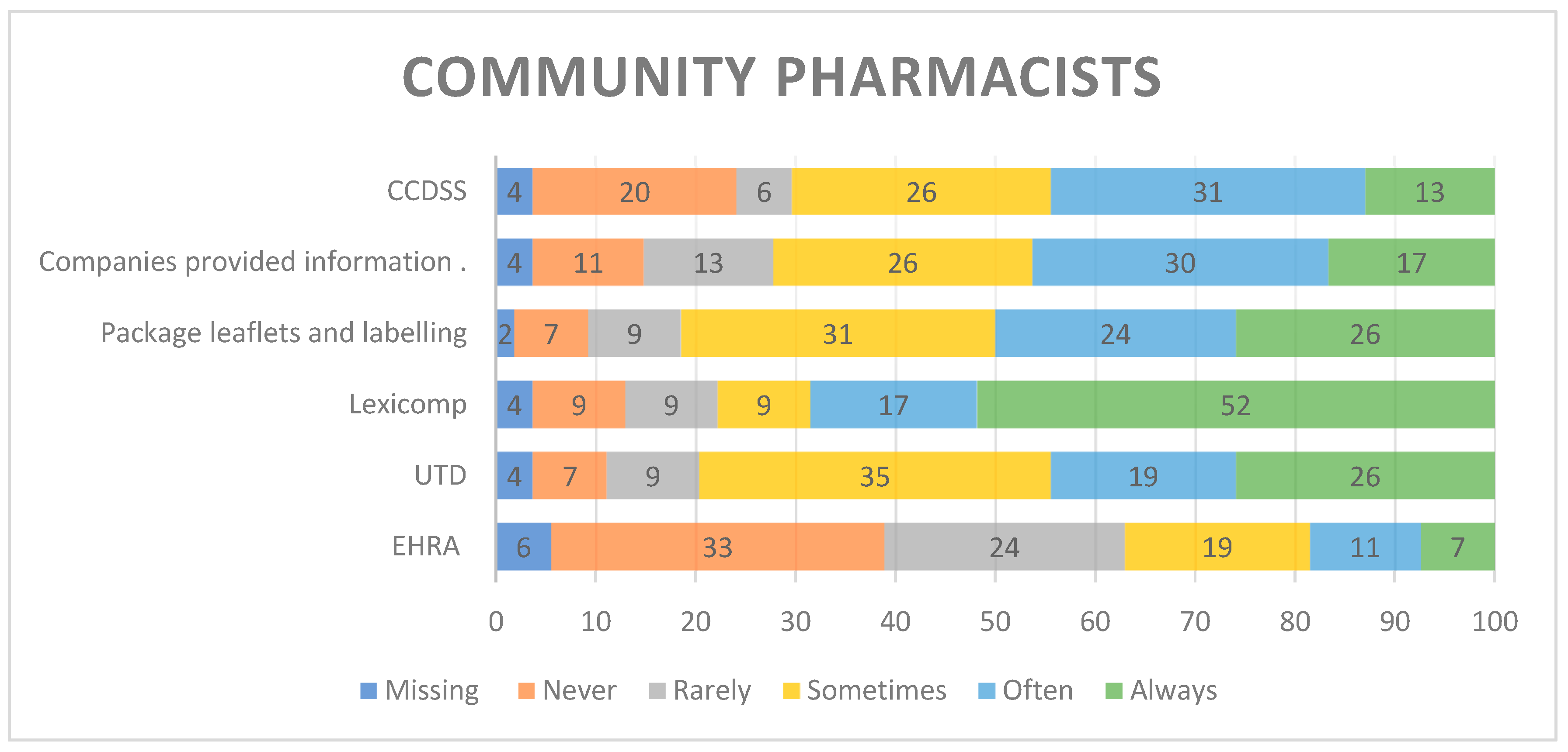

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 illustrates the frequency of respondents' utilisation of various guidelines and resources in the processes of prescribing and dispensing. The recent statistics indicate that cardiologist Lexicomp consistently accounts for 57.5%. Residents in internal medicine consistently utilised Lexicomp at a rate of 73.5%. Likewise, general practitioners consistently choose Lexicomp (68.42%). A similar trend is observed among hospital pharmacists and community pharmacists, at 72.6% and 52%, respectively.

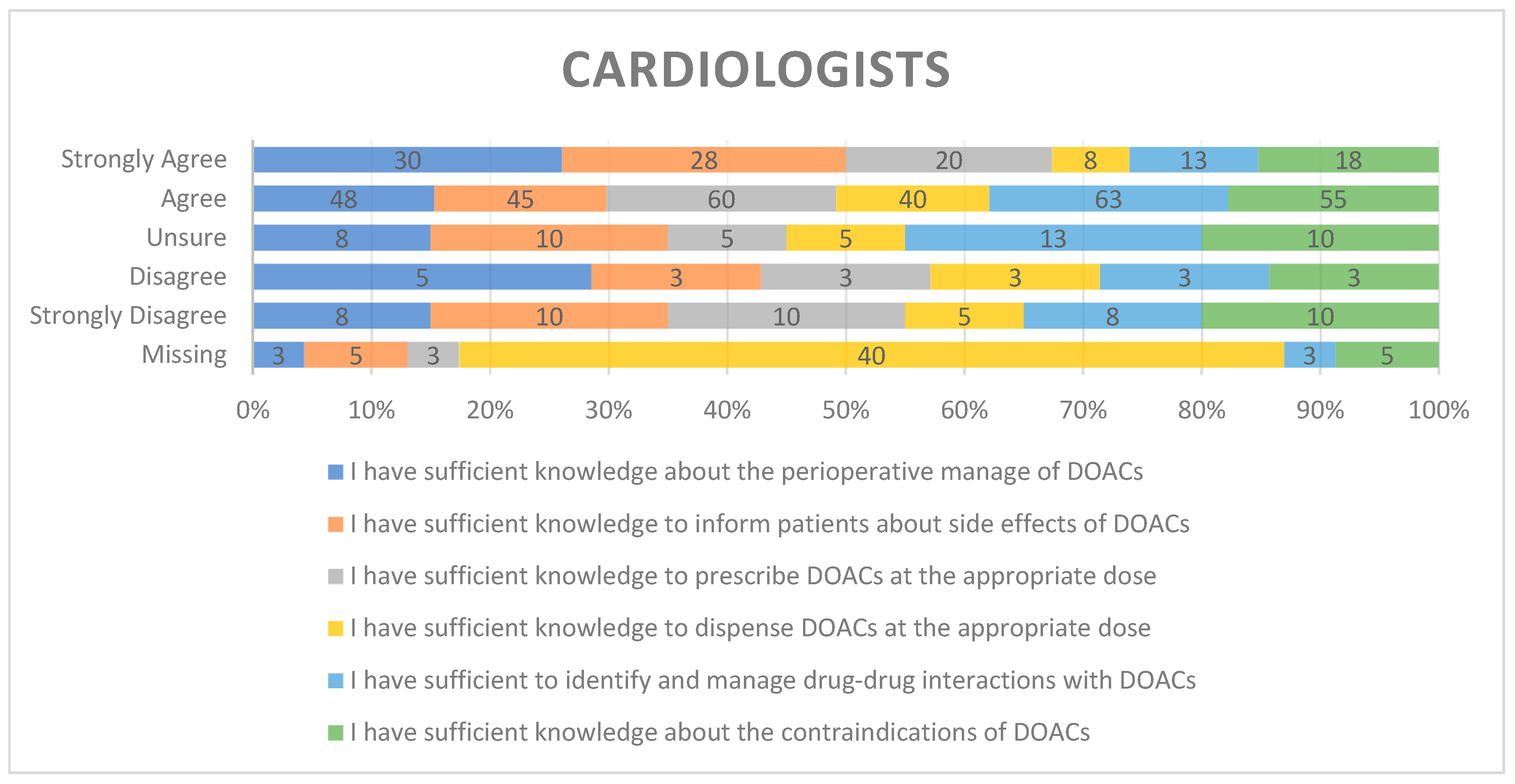

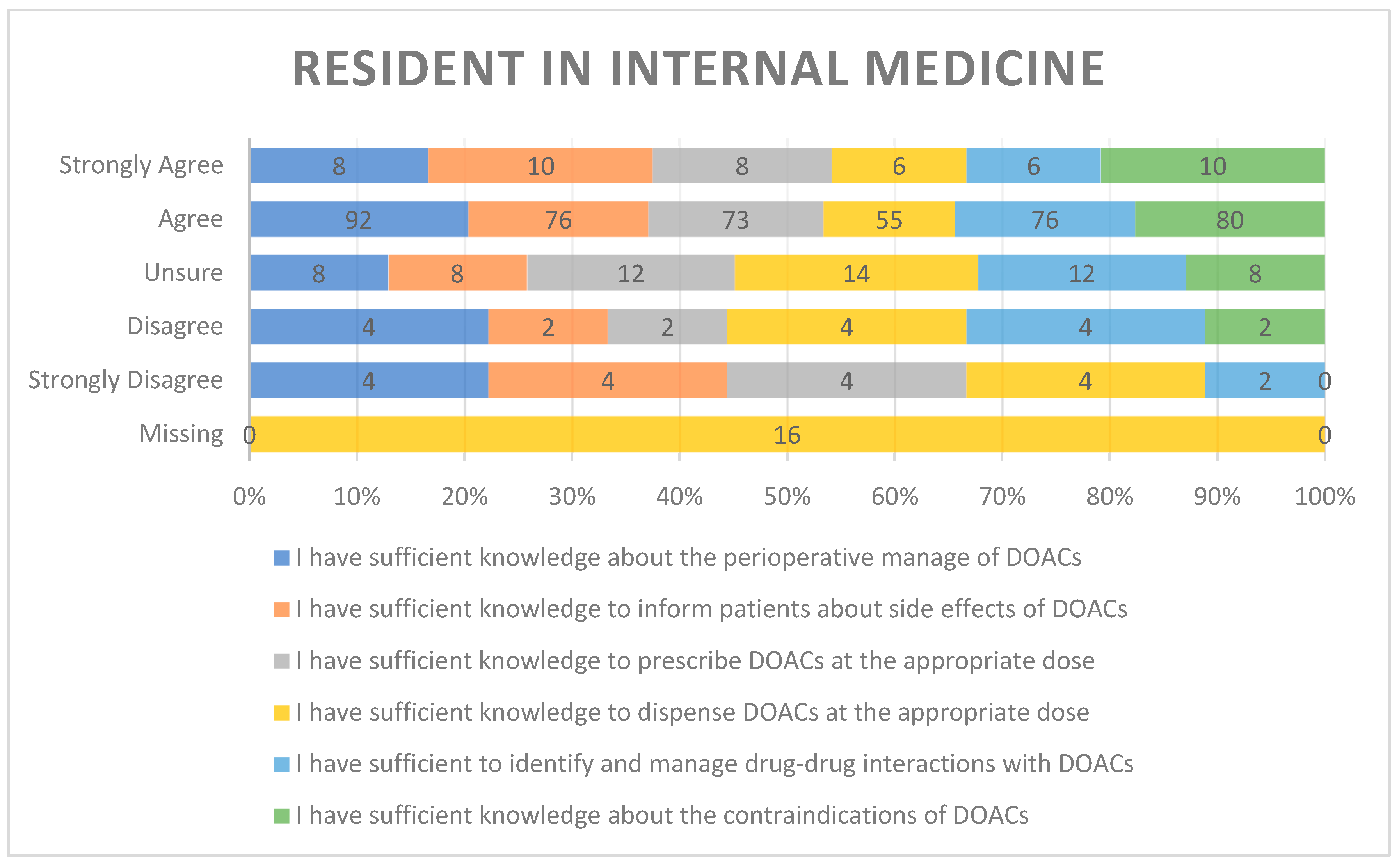

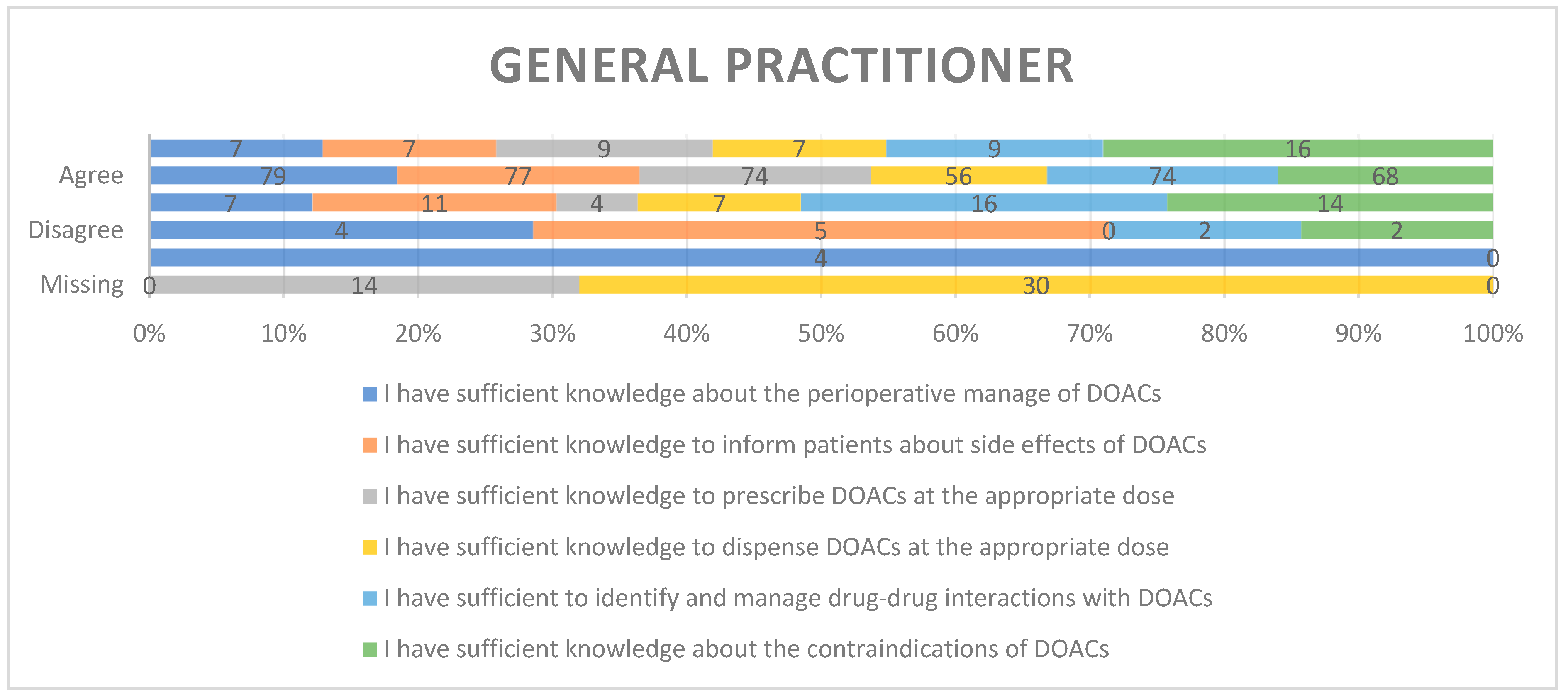

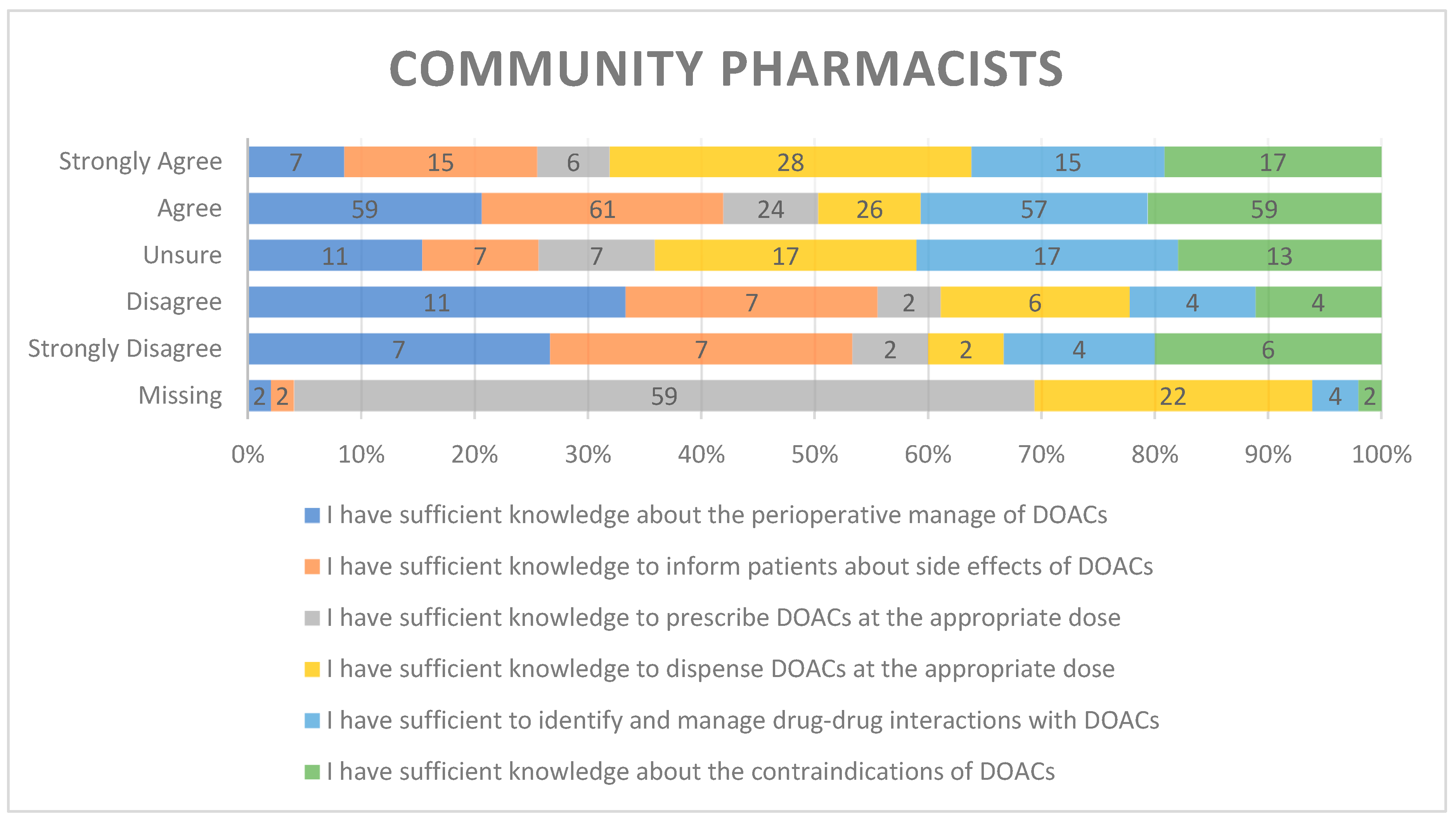

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 illustrates the respondents' self-assessed knowledge of the prescription or dispensing of DOACs. The graphical representation generally emphasized the understanding of preoperative management, educating patients on side effects, prescribing and dispensing suitable doses of DOACs, as well as knowledge regarding the identification and management of drug-drug interactions with DOACs and awareness of contraindications. The results demonstrated that pharmacists have complied with the requisite understanding of preoperative management (CP= 59%, HP= 68%), dispensing (CP= 26%, HP= 50%), and educating patients of drug adverse effects (CP= 61%, HP= 66%). The physicians indicated agreement regarding their knowledge in preoperative management (Cardiology= 48%, Internal Medicine Residents= 92%, General Practitioners= 79%), prescribing (Cardiology= 60%, Internal Medicine Residents= 73%, General Practitioners= 74%), drug interactions with DOACs (Cardiology= 63%, Internal Medicine Residents= 76%, General Practitioners= 74%), informing patients about drug side effects (Cardiology= 45%, Internal Medicine Residents= 76%, General Practitioners= 77%), and contraindications (Cardiology= 55%, Internal Medicine Residents= 80%, General Practitioners= 68%). Nevertheless, physicians exhibited proficient understanding of all the aforementioned fields.

4. Discussion

DOACs are a great step forward in the field of anticoagulation. VKAs have been replaced by DOACs in the guidelines for various indications requiring anticoagulations20. The current study aimed to explore prescribers’ and pharmacists’ perspectives and experiences in managing newer direct-acting oral anticoagulants in clinical practice in Saudi Arabia, along with their self-assessed knowledge on various aspects of these medicines.

When comparing prescribers based on their medical specialty, a higher proportion of cardiologists (35%) prescribe DOACs, compared to internal medicine trainees and general practitioners. The current finding is in line with a report from Belgium by Capiau et al. where majority of cardiologists report prescription of DOACs on weekly base versus internal medicine trainees and general practioners21. This can be explained by the fact that DOACs is used to treat conditions such as thromboprophylaxis following major orthopedic surgery, the treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE), and the prevention of stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. (NVAF)22—all of which are closely related to the cardiac system. Therefore, it is not surprising to see cardiologists play a crucial role in the management of these conditions, contributing significantly to the prescription of DAOA.

Prescribers and pharmacists were also asked to rate, on a 5-point Likert scale, how often they prescribed or dispensed a reduced dose of DOACs. The average scores for prescribers of different specialities ranged (4.75 ± 3.22 - 4.04 ± 2.25). This suggests that dose reduction is a common practice when prescribing DOACs. This conclusion is further supported by the similar scores reported by pharmacists who dispensed reduced dose of the medicines (4.58 ± 2.69 for HP and 3.85 ± 2.78 for CP). These findings align with reports from Belgium, where cardiologists, as well as internal medicine residents and general practitioners, believed that 25% and 33% of their patients were prescribed a reduced dose of the medicines21. This is likely because patients who require these medications are often multimorbid, and a significant proportion of them may meet the dose reduction criteria outlined in the guidelines23.

Participants in the current study referred to various resources for clinical decision-making while prescribing or dispensing the medicines. These included UpToDate, the European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide (EHRA), and the Clinical Decision Support System (CDSS). Among these resources, LexiDrug was the most frequently used reference, with utilization rates of 73.5% for internal medicine residents, 68.4% for general practitioners, and 57.5% for cardiologists. In contrast, a study from Belgium found that the EHRA was the most frequently used resource for consultation by cardiologists, with a utilization rate of 67.9%21. Difference in selection of utilization of resource for consultation may be attributable to physicians’ preference and familiarity and differences in complexity of the patient factors.

Patient preference was the most frequently cited factor influencing the prescription of a specific DOAC across all three specialties of prescribers, followed by the side effect profile, renal function, weight, and individual drug characteristics.

The current study also examined the perceived knowledge of prescribers towards direct acting oral anticoagulants across various medical specialties, including cardiologists, internal medicine residents, and general practitioners, as well as hospital and community pharmacists. Accordingly, 68% to 85% of participants across each specialty are confident in their knowledge of using DOACs for perioperative management, either agreeing or strongly agreeing that they have sufficient expertise in this area. This finding aligns with a study by Alnemari R et al. from Saudi Arabia, where many participants (67.2% of prescribers) were knowledgeable about the use of these medicines, and around 70% were aware of the information that should be provided to patients24. It is good that more than two-third of participants in each department perceived that they have the necessary knowledge to use the medicines. However, a notable proportion of the study participants—12.7% of cardiologists, 6.7% of internal medicine residents, and 7.9% of general practitioners—either disagreed or strongly disagreed when asked about their knowledge of using these medicines. This highlights the need for ongoing training to keep healthcare providers updated on the clinical use of these medications.

The study also highlighted that prescribers and pharmacists generally had a positive self-perception of their knowledge in key areas, including appropriate dosing, patient education, identifying and managing drug-drug interactions, and contraindications. The majority of participants—over two-thirds—believed they possessed sufficient knowledge in these aspects. A lack of knowledge in these areas can lead to medication errors. A previous cross-sectional cohort study conducted in Saudi Arabia highlighted several issues with newer anticoagulants. These included incorrect initial doses, inappropriate maintenance doses, and potentially significant drug-drug interactions, among other concerns25. A knowledge gap regarding the use of OACS was identified as one of the contributing factors in a qualitative study involving prescribers in Saudi Arabia26. Consistent with this, a systematic review and meta-analysis on contributory factors related to medication errors in this group of medicines identified knowledge gaps as one of the primary factors27. This finding underscores the importance of assessing the actual knowledge levels of practitioners and implementing appropriate educational interventions accordingly.

4.1. Study Limitations

As we utilized an online survey as our methodology, it may be subject to social desirability bias, where respondents tend to provide more favourable answers to knowledge-based questions. Consequently, the reported results may not accurately reflect their actual level of knowledge.

5. Conclusions

This study revealed that most participants preferred newer oral anticoagulants over warfarin and demonstrated a fairly good level of self-perceived knowledge regarding various aspects of the clinical use of DOACs. The study findings highlight the importance of focused training initiatives to standardize the use of DOACs, boost trust among community pharmacists and GPs, and ensure the safe and effective patient care. Qualitative research is recommended to ascertain the factors affecting HCPs' adherence to DOAC guidelines, particularly those with lower self-reported confidence levels.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of conflicting interests

None of the authors has any conflicts of interest to declare.

Data availability

All data are available in the manuscript file.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the use of ChatGPT 5.1 (OpenAI), an AI-based language tool, for the enhancement of clarity and readability of the manuscript.

References

- Connolly, SJ; Ezekowitz, MD; Yusuf, S; Eikelboom, J; Oldgren, J; Parekh, A; et al. Dabigatran versus Warfarin in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. New England Journal of Medicine 2009, 361(12), 1139–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giugliano, RP; Ruff, CT; Braunwald, E; Murphy, SA; Wiviott, SD; Halperin, JL; et al. Edoxaban versus Warfarin in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. New England Journal of Medicine 2013, 369(22), 2093–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, CB; Alexander, JH; McMurray, JJV; Lopes, RD; Hylek, EM; Hanna, M; et al. Apixaban versus Warfarin in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. New England Journal of Medicine 2011, 365(11), 981–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearon, C; Akl, EA; Ornelas, J; Blaivas, A; Jimenez, D; Bounameaux, H; et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest 2016, 149(2), 315–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, MR; Mahaffey, KW; Garg, J; Pan, G; Singer, DE; Hacke, W; et al. Rivaroxaban versus Warfarin in Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation. New England Journal of Medicine 2011, 365(10), 883–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindricks, G; Potpara, T; Dagres, N; Arbelo, E; Bax, JJ; Blomström-Lundqvist, C; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. European Heart Journal 2020, 42(5), 373–498. [Google Scholar]

- January, CT; Wann, LS; Calkins, H; Chen, LY; Cigarroa, JE; Cleveland, JC; et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society in Collaboration With the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation 2019, 140(2), e125–e51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lip, GYH; Banerjee, A; Boriani, G; Chiang, Ce; Fargo, R; Freedman, B; et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest 2018, 154(5), 1121–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camm, AJ; Accetta, G; Ambrosio, G; Atar, D; Bassand, J-P; Berge, E; et al. Evolving antithrombotic treatment patterns for patients with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation. Heart 2017, 103(4), 307–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capiau, A; De Backer, T; Grymonprez, M; Lahousse, L; Van Tongelen, I; Mehuys, E; et al. Appropriateness of direct oral anticoagulant dosing in patients with atrial fibrillation according to the drug labelling and the EHRA Practical Guide. International Journal of Cardiology 2021, 328, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanghai, S; Wong, C; Wang, Z; Clive, P; Tran, W; Waring, M; et al. Rates of Potentially Inappropriate Dosing of Direct-Acting Oral Anticoagulants and Associations With Geriatric Conditions Among Older Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: The SAGE-AF Study. Journal of the American Heart Association 2020, 9(6), e014108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruff, CT; Giugliano, RP; Braunwald, E; Hoffman, EB; Deenadayalu, N; Ezekowitz, MD; et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. The Lancet 2014, 383(9921), 955–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capiau, A; Mehuys, E; Van Tongelen, I; Christiaens, T; De Sutter, A; Steurbaut, S; et al. Community pharmacy-based study of adherence to non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants. Heart 2020, 106(22), 1740–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, J; Gallagher, C; Nyfort-Hansen, K; Lau, D; Sanders, P. Adherence to anticoagulation therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation: is a tailored team-based approach warranted? Heart 2020, 106(22), 1710–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffel, J; Verhamme, P; Potpara, TS; Albaladejo, P; Antz, M; Desteghe, L; et al. The 2018 European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. European Heart Journal. 2018, 39(16), 1330–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, C; Elliott, AD; Wong, CX; Rangnekar, G; Middeldorp, ME; Mahajan, R; et al. Integrated care in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart 2017, 103(24), 1947–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Generalova, D; Cunningham, S; Leslie, SJ; Rushworth, GF; McIver, L; Stewart, D. A systematic review of clinicians' views and experiences of direct-acting oral anticoagulants in the management of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2018, 84(12), 2692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capiau, A; Mehuys, E; Dhondt, E; De Backer, T; Boussery, K. Physicians' and pharmacists' views and experiences regarding use of direct oral anticoagulants in clinical practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022, 88(4), 1856–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. 2020 Health Indicators 2020. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/Statistics/Indicator/Pages/Indicator-2020.aspx.

- Abdelnabi, M; Benjanuwattra, J; Okasha, O; Almaghraby, A; Saleh, Y; Gerges, F. Switching from warfarin to direct-acting oral anticoagulants: it is time to move forward! The Egyptian Heart Journal 2022, 74(1), 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capiau, A; Mehuys, E; Dhondt, E; De Backer, T; Boussery, K. Physicians' and pharmacists' views and experiences regarding use of direct oral anticoagulants in clinical practice. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2022, 88(4), 1856–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McRae, HL; Militello, L; Refaai, MA. Updates in anticoagulation therapy monitoring. Biomedicines 2021, 9(3), 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A; Stecker, E; A. Warden, B. Direct oral anticoagulant use: a practical guide to common clinical challenges. Journal of the American Heart Association 2020, 9(13), e017559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnemari, R; Banheem, A; Mullaniazee, N; Alghamdi, S; Rajkhan, A; Basfar, O; Basnawi, M. Knowledge, attitude and practice of physicians towards oral anti-coagulants in Taif city, Saudi Arabia. Int J Adv Med 2018, 5(5), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, H; AlNasser, M; Assiri, A; Tawhari, F; Bakkari, A; Mustafa, M; Alotaibi, W; Asiri, A; Khudari, A; Alshreem, A; Ayoub, M. Utilization of direct oral anticoagulants in a Saudi tertiary hospital: a retrospective cohort study. European Review for Medical & Pharmacological Sciences 2023, 27(20). [Google Scholar]

- Al Rowily, A; Aloudah, N; Jalal, Z; Abutaleb, MH; Paudyal, V. Views, experiences and contributory factors related to medication errors associated with direct oral anticoagulants: a qualitative study with physicians and nurses. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy 2022, 44(4), 1057–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Rowily, A; Jalal, Z; Price, MJ; Abutaleb, MH; Almodiaemgh, H; Al Ammari, M; Paudyal, V. Prevalence, contributory factors and severity of medication errors associated with direct-acting oral anticoagulants in adult patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European journal of clinical pharmacology 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Percentage of use of different guidelines/ resources when prescribing or dispensing DOACs on a 5-point Likert scale. CCDSS: Clinical Decision Support System, UTD: Up to Date, EHRA: European Heart Rhythm Association.

Figure 1.

Percentage of use of different guidelines/ resources when prescribing or dispensing DOACs on a 5-point Likert scale. CCDSS: Clinical Decision Support System, UTD: Up to Date, EHRA: European Heart Rhythm Association.

Figure 2.

Percentage of use of different guidelines/ resources when prescribing or dispensing DOACs on a 5-point Likert scale. CCDSS: Clinical Decision Support System, UTD: Up to Date, EHRA: European Heart Rhythm Association.

Figure 2.

Percentage of use of different guidelines/ resources when prescribing or dispensing DOACs on a 5-point Likert scale. CCDSS: Clinical Decision Support System, UTD: Up to Date, EHRA: European Heart Rhythm Association.

Figure 3.

Percentage of use of different guidelines/ resources when prescribing or dispensing DOACs on a 5-point Likert scale. CCDSS: Clinical Decision Support System, UTD: Up to Date, EHRA: European Heart Rhythm Association.

Figure 3.

Percentage of use of different guidelines/ resources when prescribing or dispensing DOACs on a 5-point Likert scale. CCDSS: Clinical Decision Support System, UTD: Up to Date, EHRA: European Heart Rhythm Association.

Figure 4.

Percentage of use of different guidelines/ resources when prescribing or dispensing DOACs on a 5-point Likert scale. CCDSS: Clinical Decision Support System, UTD: Up to Date, EHRA: European Heart Rhythm Association.

Figure 4.

Percentage of use of different guidelines/ resources when prescribing or dispensing DOACs on a 5-point Likert scale. CCDSS: Clinical Decision Support System, UTD: Up to Date, EHRA: European Heart Rhythm Association.

Figure 5.

Percentage of use of different guidelines/ resources when prescribing or dispensing DOACs on a 5-point Likert scale. CCDSS: Clinical Decision Support System, UTD: Up to Date, EHRA: European Heart Rhythm Association.

Figure 5.

Percentage of use of different guidelines/ resources when prescribing or dispensing DOACs on a 5-point Likert scale. CCDSS: Clinical Decision Support System, UTD: Up to Date, EHRA: European Heart Rhythm Association.

Figure 6.

Self-perceived knowledge about different topics concerning DOACs on a 5-point Likert scale.

Figure 6.

Self-perceived knowledge about different topics concerning DOACs on a 5-point Likert scale.

Figure 7.

Self-perceived knowledge about different topics concerning DOACs on a 5-point Likert scale.

Figure 7.

Self-perceived knowledge about different topics concerning DOACs on a 5-point Likert scale.

Figure 8.

Self-perceived knowledge about different topics concerning DOACs on a 5-point Likert scale.

Figure 8.

Self-perceived knowledge about different topics concerning DOACs on a 5-point Likert scale.

Figure 9.

Self-perceived knowledge about different topics concerning DOACs on a 5-point Likert scale.

Figure 9.

Self-perceived knowledge about different topics concerning DOACs on a 5-point Likert scale.

Figure 10.

Self-perceived knowledge about different topics concerning DOACs on a 5-point Likert scale.

Figure 10.

Self-perceived knowledge about different topics concerning DOACs on a 5-point Likert scale.

Table 1.

Frequency of DOAC Prescribing/Dispensing, Preferences, and Influencing Factors by Healthcare Professionals.

Table 1.

Frequency of DOAC Prescribing/Dispensing, Preferences, and Influencing Factors by Healthcare Professionals.

| Frequency of initiation/dispensing DOACs n% |

|---|

| |

Cardiologist

(n= 40) |

Resident in Internal Medicine

(n= 49) |

General Practitioner (GP)

(n= 57) |

Hospital Pharmacist (n= 113) |

Community Pharmacist

(n= 54) |

| Daily |

57.5 |

71.4 |

66.7 |

51.3 |

55.6 |

| Weekly |

35 |

16.3 |

17.5 |

23.9 |

16.7 |

| Monthly |

5 |

2 |

8.8 |

8.8 |

11.1 |

| Annually |

2.5 |

6.1 |

3.5 |

8 |

11.1’ |

| Never |

0 |

4.1 |

3.5 |

8 |

5.6 |

| Frequency of Specific DOAC Use (Mean ± SD) |

| Apixaban |

.80 ± .40 |

.86 ± .35 |

.93 ± .25 |

.84 ± .36 |

.70 ± .46 |

| Dabigatran |

.25 ± .43 |

.08 ± .27 |

.07 ± .25 |

.12 ± .33 |

.24 ± .43 |

| Edoxaban |

.35 ± .48 |

.55 ± .50 |

.40 ± .49 |

.16 ± .36 |

.39 ± .49 |

| Rivaroxaban |

.32 ± .47 |

.49 ± .50 |

.25 ± .43 |

.30 ± .46 |

.37 ± .48 |

| DOAC Dose Reduction (Mean ± SD) |

| % reduced dose |

4.75 ± 3.22 |

4.43 ± 1.94 |

4.04 ± 2.25 |

4.58 ± 2.69 |

3.85 ± 2.78 |

| Factors influencing DOAC prescribing behavior (Mean ± SD) |

| Patients’ characteristics (weight) |

3.43 ± 1.33 |

2.59 ± 1.30 |

2.46 ± 1.57 |

.84 ± 1.49 |

1.17 ± 1.62 |

| Renal function |

3.75 ± 1.21 |

3.76 ± 1.39 |

3.65 ± 1.62 |

1.03 ± 1.86 |

1.20 ± 1.80 |

| DOAC Molecule |

3.18 ± 1.21 |

2.18 ± 1.33 |

2.05 ± 1.30 |

.61 ± 1.27 |

.87 ± 1.38 |

| Side effect profile |

3.77 ± 1.16 |

3.98 ± 1.09 |

3.72 ± 1.57 |

.84 ± 1.69 |

1.24 ± 1.85 |

| Company’s information |

3.10 ± 1.19 |

3.37 ± 1.03 |

3.02 ± 1.40 |

.67 ± 1.43 |

.74 ± 1.37 |

| Patient’s preferences |

3.95 ± 1.03 |

3.94 ± .68 |

3.98 ± .85 |

3.82 ± .75 |

3.69 ± 1.02 |

| Perceptions of DOACs Relative to VKAs (Mean ± SD) |

| DOAC relative to VKA |

3.87 ± .88 |

3.90 ± .71 |

3.89 ± .88 |

3.79 ± .86 |

3.72 ± 1.01 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).