Submitted:

10 December 2025

Posted:

14 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

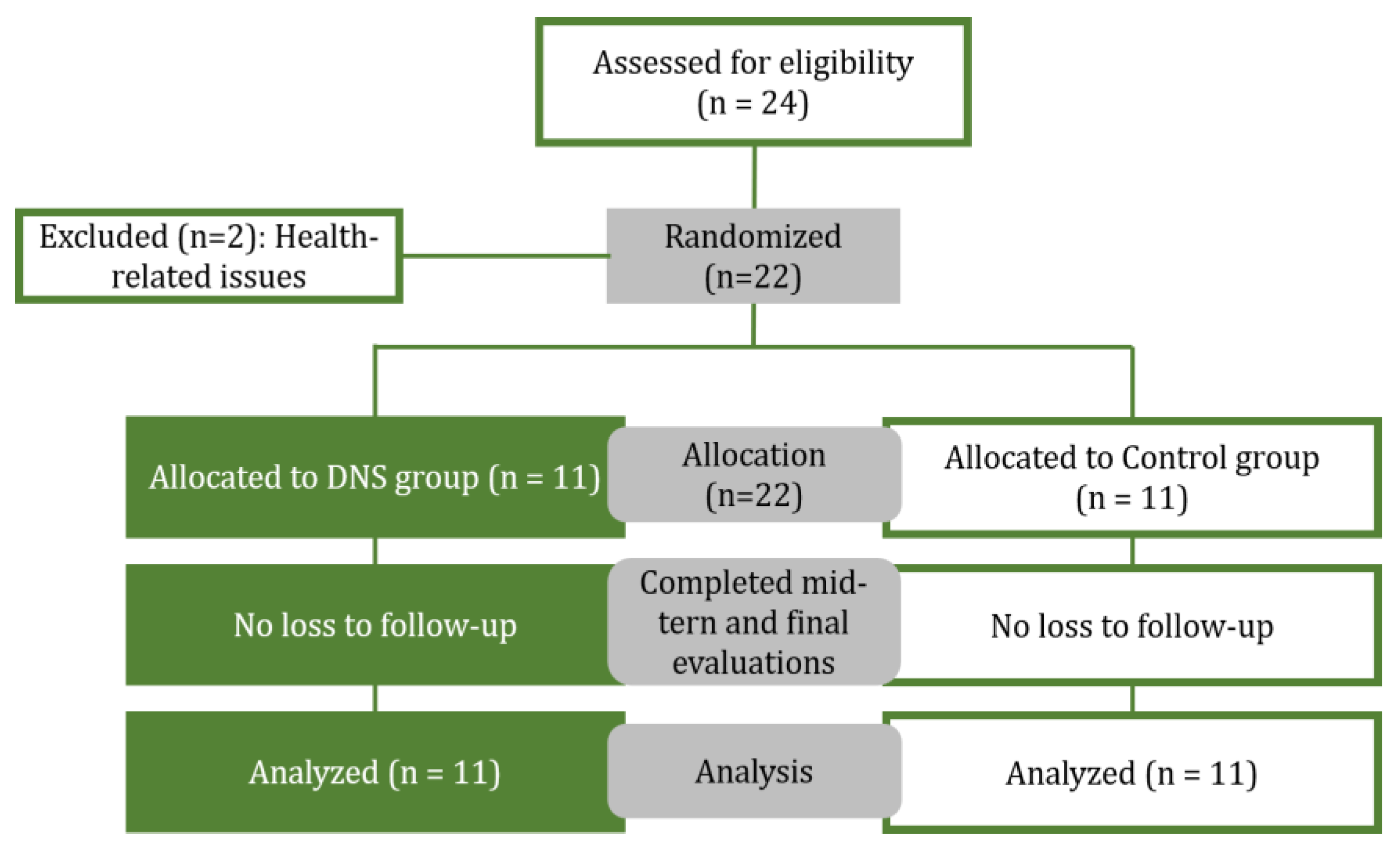

2.1. Participants

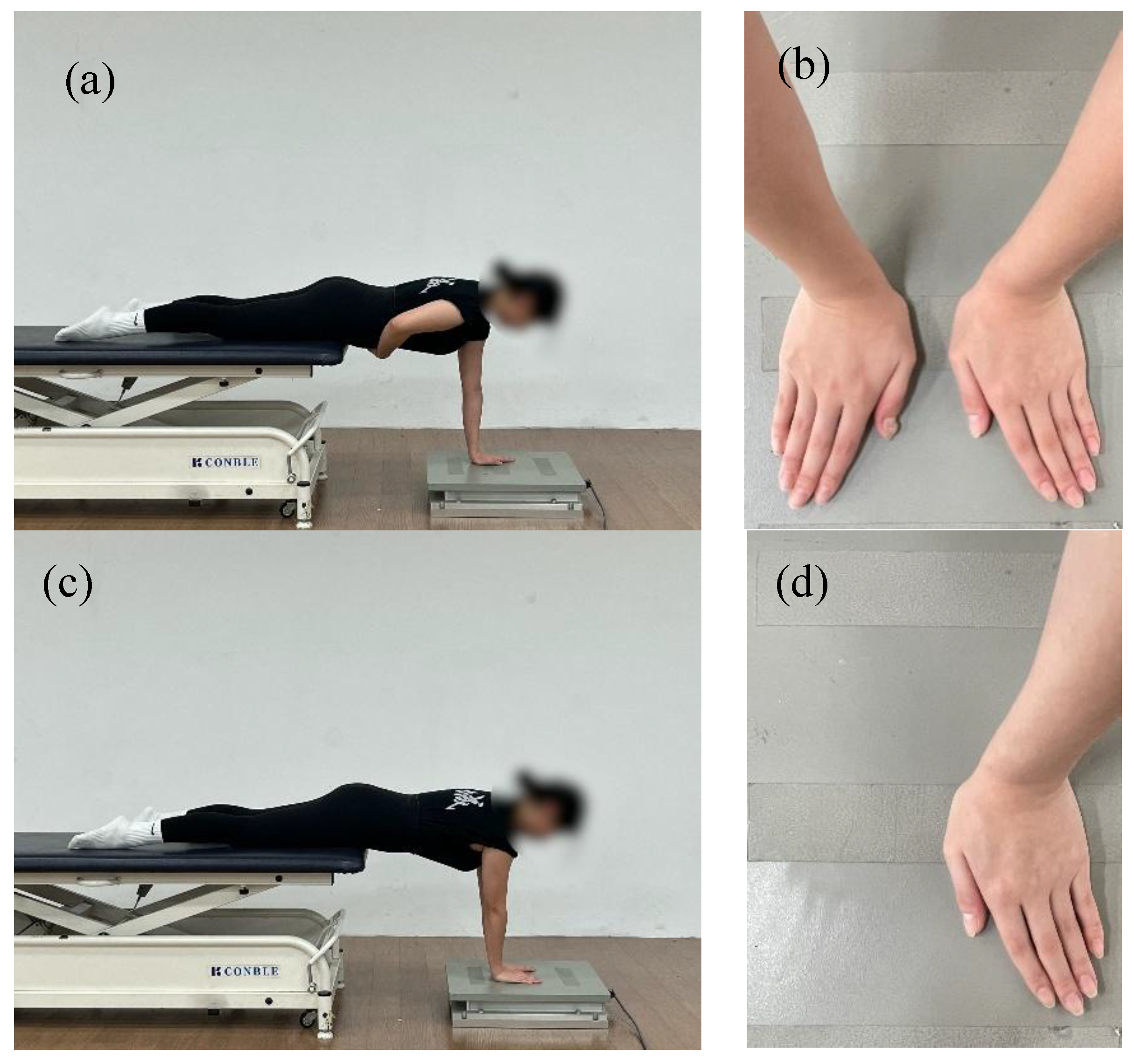

2.2. Assessment of COP and Data Acquisition

2.3. Evaluation of Pain Intensity (VAS)

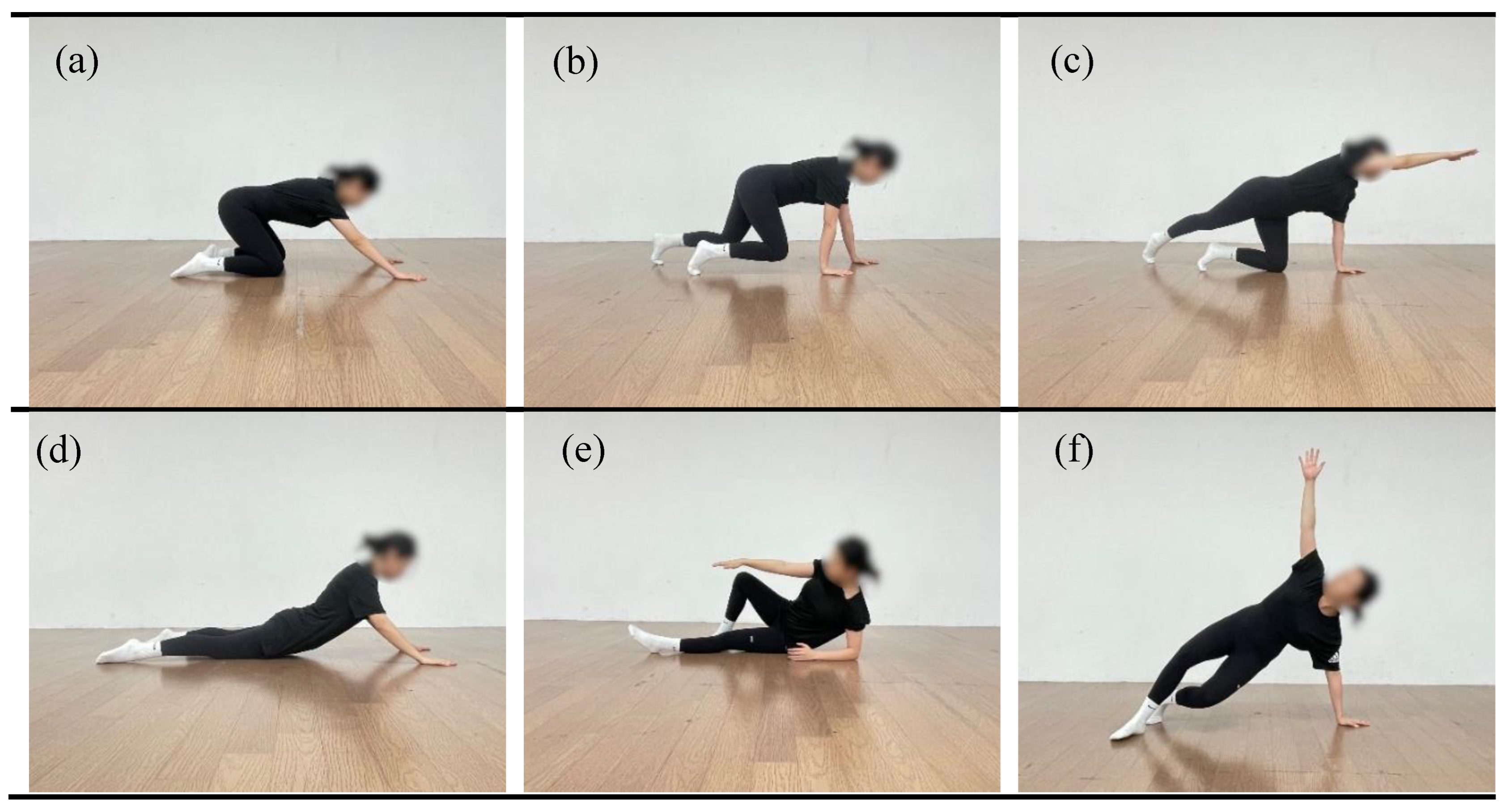

2.4. Exercise Intervention

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Changes in COP Under the Affected-Side Single-Hnad Support Condition

3.2. Changes in COP Under the Eyes-Open Bilateral Hand Support Condition

3.3. Changes in COP Under the Eyes-Closed Bilateral Hand Support,Condition

3.4. Changes in Pain Indicator (VAS)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Date, A.; Rahman, L. Frozen shoulder: Overview of clinical presentation and review of the current evidence base for management strategies. Future Sci. OA 2020, 6, FSO647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunker, T.D. Frozen shoulder: Unravelling the enigma. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 1997, 79, 210–213. [Google Scholar]

- Le, H.V.; Lee, S.J.; Nazarian, A.; Rodriguez, E.K. Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: Review of pathophysiology and current clinical treatments. Shoulder & Elbow 2017, 9, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePalma, A.F. Loss of scapulohumeral motion (frozen shoulder). Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2008, 466, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neviaser, A.S.; Hannafin, J.A. Adhesive capsulitis: A review of current treatment. Am. J. Sports Med. 2010, 38, 2346–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-M.; Cho, E.-Y.; Lee, B.-H. Effects of dynamic stretching combined with manual therapy on pain, ROM, function, and quality of life of adhesive capsulitis. Healthcare 2024, 12, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulwani, A.H. A Study to Find Out the Effect of Scapular Stabilization Exercises on Shoulder ROM and Functional Outcome in Diabetic Patients with Stage 2 Adhesive Capsulitis of the Shoulder Joint—An Interventional Study. Int. J. Sci. Healthc. Res. 2020, 5, 320–333. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, B.C.; Laakkonen, E.K.; Lowe, D.A. Aging of the musculoskeletal system: How the loss of estrogen impacts muscle strength. Bone 2019, 123, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Chen, Y.; Lv, Y. The effect of housework, psychosocial stress and residential environment on musculoskeletal disorders for Chinese women. SSM Popul. Health 2023, 23, 101545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leclerc, A.; Chastang, J.-F.; Niedhammer, I.; Landre, M.-F.; Roquelaure, Y. Incidence of shoulder pain in repetitive work. Occup. Environ. Med. 2004, 61, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pehkonen, I.; Miranda, H.; Haukka, E.; Luukkonen, R.; Takala, E.-P.; Ketola, R.; Leino-Arjas, P.; Riihimäki, H.; Viikari-Juntura, E. Prospective study on shoulder symptoms among kitchen workers in relation to self-perceived and observed work load. Occup. Environ. Med. 2009, 66, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, J.E.; Blasier, R.B.; Pellizzon, G.G. The effects of muscle fatigue on shoulder joint position sense. Am. J. Sports Med. 1998, 26, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfaya, F.F.; Reddy, R.S.; Alkhamis, B.A.; Kandakurti, P.K.; Mukherjee, D. Shoulder proprioception and its correlation with pain intensity and functional disability in individuals with subacromial impingement syndrome—A cross-sectional study. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balci, N.C.; Yuruk, Z.O.; Zeybek, A.; Gulsen, M.; Tekindal, M.A. Acute effect of scapular proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) techniques and classic exercises in adhesive capsulitis: A randomized controlled trial. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2016, 28, 1219–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). IASP revises its definition of pain for the first time since 1979. Available online: https://www.iasp-pain.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/revised-definition-flysheet_R2-1-1-1.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Mallick-Searle, T.; Sharma, K.; Toal, P.; Gutman, A. Pain and function in chronic musculoskeletal pain—Treating the whole person. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2021, 14, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, U.G.; Facchinetti, G.; Marchetti, A.; Candela, V.; Risi Ambrogioni, L.; Faldetta, A.; De Marinis, M.G.; Denaro, V. Sleep Disturbance and Rotator Cuff Tears: A Systematic Review. Medicina 2019, 55, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, F.; Sole, G.; Wassinger, C.A.; Osborne, H.; Beilmann, M.; Mercier, C.; Campeau-Lecours, A.; Bouyer, L.J.; Roy, J.-S. The Impact of Experimental Pain on Shoulder Movement during an Arm Elevated Reaching Task in a Virtual Reality Environment. Physiol. Rep. 2021, 9, e15025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, M.; Jull, G.; Wright, A. The effect of musculoskeletal pain on motor activity and control. The Journal of Pain 2001, 2(3), 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamai, K.; Hamada, J.; Nagase, Y.; Morishige, M.; Naito, M.; Asai, H.; Tanaka, S. Frozen shoulder: An overview of pathology and biology with hopes to novel drug therapies. Mod. Rheumatol. 2024, 34, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaeyen, J.W.S. Learning to predict and control harmful events: Chronic pain and conditioning. Pain 2015, 156, S86–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falla, D.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Farina, D. The pain-induced change in relative activation of upper trapezius muscle regions is independent of the site of noxious stimulation. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2008, 119, 2433–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinnis, K.; Snyder-Mackler, L.; Flowers, P.; Zeni, J. Dynamic joint stiffness and co-contraction in subjects after total knee arthroplasty. Clin. Biomech. 2013, 28, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ager, A.L.; Borms, D.; Deschepper, L.; Dhooghe, R.; Dijkhuis, J.; Roy, J.-S.; Cools, A. Proprioception: How is it affected by shoulder pain? A systematic review. J. Hand Ther. 2019, xxx, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hei, P.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, J.; Lan, C.; Wang, X.; Jing, X.; Chen, X.; Wu, Z. The effect of dynamic neuromuscular stabilization technique combined with Kinesio taping on neuromuscular function and pain self-efficacy in individuals with chronic nonspecific low back pain: A randomized trial. Medicine 2025, 104, e41265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakinepoor, A.; Mazidi, M. Neck stabilization exercise and dynamic neuromuscular stabilization reduce pain intensity, forward head angle and muscle activity of employees with chronic nonspecific neck pain: A retrospective study. J. Exp. Orthop. 2025, 12, e70188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, C.; Kobesova, A.; Kolar, P. Dynamic neuromuscular stabilization & sports rehabilitation. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2013, 8, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kobesova, A.; Kolar, P. Developmental kinesiology: Three levels of motor control in the assessment and treatment of the motor system. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2014, 18, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabieezadeh, A.; Mahdavinejad, R.; Sedehi, M.; Adimi, M. The effects of an 8-week dynamic neuromuscular stabilization exercise on pain, functional disability, and quality of life in individuals with non-specific chronic low back pain: A randomized clinical trial with a two-month follow-up study. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2024, 16, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Xie, H.; Zhang, G.; Xiao, W.; Ge, L.; Chen, S.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, H. Effects of dynamic neuromuscular stabilization training on the core muscle contractility and standing postural control in patients with chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2025, 26, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karartı, C.; Özsoy, İ.; Özyurt, F.; Basat, H.Ç.; Özsoy, G.; Özüdoğru, A. The effects of dynamic neuromuscular stabilization approach on clinical outcomes in older patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain: A randomized, controlled clinical trial. Somatosens. Mot. Res. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobesova, A.; Nørgaard, I.; Kolar, P. Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization – DNS Neurorehab Chapter. Unpublished educational document, 2014. Available online: https://rehabps.com/DATA/DNS_Neurorehab_Chapter.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Teng, Y.-L.; Chen, C.-L.; Lou, S.-Z.; Wang, W.-T.; Wu, J.-Y.; Ma, H.-I.; Chen, V.C.-H. Postural stability of patients with schizophrenia during challenging sensory conditions: Implication of sensory integration for postural control. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Martel, V.; Santuz, A.; Ekizos, A.; Arampatzis, A. Neuromuscular organisation and robustness of postural control in the presence of perturbations. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quijoux, F.; Nicolaï, A.; Chairi, I.; Bargiotas, I.; Ricard, D.; Yelnik, A.; Oudre, L.; Bertin-Hugault, F.; Vidal, P.-P.; Vayatis, N.; Buffat, S.; Audiffren, J. A review of center of pressure (COP) variables to quantify standing balance in elderly people: Algorithms and open-access code. Physiol. Rep. 2021, 9, e15067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Seol, H.; Nussbaum, M.A.; Madigan, M.L. Reliability of COP-based postural sway measures and age-related differences. Gait Posture 2008, 28, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edouard, P.; Gasq, D.; Calmels, P.; Ducrot, S.; Degache, F. Shoulder Sensorimotor Control Assessment by Force Platform: Feasibility and Reliability. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2012, 32, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Park, I.; Ha, M.-S. Effect of dynamic neuromuscular stabilization training using the inertial load of water on functional movement and postural sway in middle-aged women: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Womens Health 2024, 24, 2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, K.; Yadav, A. Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Health Sci. Res. 2020, 10(9), 221–231. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Ishii, K. Effects of Static Stretching for 30 Seconds and Dynamic Stretching on Leg Extension Power. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2005, 19(3), 677–683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kerwin, D.G.; Trewartha, G. Strategies for Maintaining a Handstand in the Anterior–Posterior Direction. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2001, 33, 1182–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, E.; Lewis, J.S.; Halaki, M.; Ginn, K.; Yeowell, G.; Gibson, J.; Morgan, C. Role of the Kinetic Chain in Shoulder Rehabilitation: Does Incorporating the Trunk and Lower Limb into Shoulder Exercise Regimes Influence Shoulder Muscle Recruitment Patterns? A Systematic Review of Electromyography Studies. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2020, 6, e000683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sozzi, S.; Ghai, S.; Schieppati, M. The ‘Postural Rhythm’ of the Ground Reaction Force during Upright Stance and Its Conversion to Body Sway—The Effect of Vision, Support Surface and Adaptation to Repeated Trials. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.E.; Sigward, S.M. Subtle Alterations in Whole Body Mechanics during Gait Following Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Gait Posture 2019, 68, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, D.A. Human balance and posture control during standing and walking. Gait Posture 1995, 3, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lephart, S. M.; Henry, T. J. The physiological basis for open and closed kinetic chain rehabilitation for the upper extremity. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation 1996, 5(1), 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasluosta, C.F.; Steib, S.; Klamroth, S.; Gaßner, H.; Goßler, J.; Hannink, J.; von Tscharner, V.; Pfeifer, K.; Winkler, J.; Klucken, J.; Eskofier, B.M. Acute neuromuscular adaptations in the postural control of patients with Parkinson’s disease after perturbed walking. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleksy, Ł.; Mika, A.; Kuchciak, M.; Bril, G.; Sopa, M.; Adamska, O.; Kielnar, R.; Zyznawska, J.; Dzi˛ecioł-Anikiej, Z.; Stolarczyk, A.; Witkowski, J.; Deszczy´nski, J.M. Reliability study of weight-bearing upper extremity sway test performed on a force plate in the one-handed plank position. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, D.; Carpes, F.P.; Milani, T.L.; Germano, A.M.C. Different visual manipulations have similar effects on quasi-static and dynamic balance responses of young and older people. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertsen, I.M.; Ghédira, M.; Gracies, J.-M.; Hutin, É. Postural stability in young healthy subjects: Impact of reduced base of support, visual deprivation, dual tasking. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2017, 33, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontillo, M.; Orishimo, K.F.; Kremenic, I.J.; McHugh, M.P.; Mullaney, M.J.; Tyler, T. Shoulder musculature activity and stabilization during upper extremity weight-bearing activities. N. Am. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2007, 2(2), 90–96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Craig, C.E.; Goble, D.J.; Doumas, M. Proprioceptive acuity predicts muscle co-contraction of the tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius medialis in older adults’ dynamic postural control. Neuroscience 2016, 322, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konrad, A.; Nakamura, M.; Sardroodian, M.; Aboozari, N.; Anvar, S.H.; Behm, D.G. The effects of chronic stretch training on musculoskeletal pain. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2025, 125, 2037–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Støve, M.P.; Thomsen, J.L.; Magnusson, S.P.; Riis, A. The effect of six-week regular stretching exercises on regional and distant pain sensitivity: An experimental longitudinal study on healthy adults. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2024, 16, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| DNSG (n = 11) | CG (n = 11) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 54.63 ± 4.27 | 60.09 ± 2.34 |

| Height (cm) | 161.42 ± 6.08 | 156.20 ± 3.19 |

| Weight (kg) | 56.66 ± 3.87 | 57.99 ± 12.97 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 21.82 ± 2.28 | 23.73 ± 5.03 |

| Training | DNSG | CG | Time/Reps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Warm-up | 1. Supine breathing 2. Supine cross-pattern activation |

1. Standing shoulder circles 2. Arm swing (forward/backward & lateral) 3. Upper thoracic extension stretch (wall-supported) 4. Shoulder internal rotation stretch 5. Cross-body posterior capsule stretch |

10min /8reps |

| Exercise | 1. Side-lying rolling 2. Prone & quadruped rocking 3. Prone position with head and chest elevation 4. Contralateral hip extension in quadruped 5. Transition from quadruped to oblique sitting via lower extremity loading 6. 3-Point transition to tall kneeling with contralateral reach 7. Quadruped Locomotion Pattern 8. Transition from Quadruped to High Side Support 9. Bear 10. Bear with alternating upper limb unloading |

1. Shoulder external & internal rotation (standing / supine) 2. Scapular retraction exercise 3. Scapular protraction/elevation control (“Y” & “T”) 4. Quadruped push-up plus ("Camel") 5. Lawn mower pull (bodyweight version) 6. Doorway pectoral stretch 7. Supine cane flexion (without equipment) 8. Cross-body shoulder stretch |

35min /6reps -8 reps |

| Cool-down | 1. Resting position for deep stabilization 2. Prone resting with diaphragmatic control |

1. Repeat upper thoracic stretch 2. Arm and shoulder swing |

5min /8reps |

| Task | Variables | Group | 0 Weeks | 4 Weeks | 8 Weeks | Source | p | ηp2 | Post Hoc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EO-AH | AP-Distance (mm) | DNSG | 86.62±14.08 | 66.59±11.36 | 49.44±8.96 | Group × Time | 0.048 | 0.160 | 0–4weeks: 0.013 |

| 4–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| CG | 86.84±10.16 | 61.39±5.45 | 58.75±7.79 | Time | 0.000 | 0.799 | 0–4weeks: 0.000 |

||

| 4–8weeks: 0.555 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| AP-velocity (mm/s) | DNSG | 2.88±0.46 | 2.21±0.37 | 1.71±0.28 | Group × Time | 0.041 | 0.168 | 0–4weeks: 0.013 |

|

| 4–8weeks: 0.001 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| CG | 2.83±0.39 | 1.96±0.37 | 1.97±0.32 | Time | 0.000 | 0.770 | 0–4weeks: 0.001 |

||

| 4–8weeks: 1.000 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.001 | |||||||||

| AP-RMS (mm) | DNSG | 0.21±0.02 | 0.15±0.01 | 0.12±0.01 | Group × Time | 0.233 | 0.071 | 0–4weeks: 0.001 |

|

| 4–8weeks: 0.005 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| CG | 0.21±0.05 | 0.14±0.02 | 0.14±0.04 | Time | 0.000 | 0.742 | 0–4weeks: 0.001 |

||

| 4–8weeks: 1.000 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.003 | |||||||||

| ML-Distance (mm) | DNSG | 87.24±13.57 | 69.55±10.65 | 57.81±13.82 | Group × Time | 0.238 | 0.069 | 0–4weeks: 0.016 |

|

| 4–8weeks: 0.002 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.002 | |||||||||

| CG | 84.75±20.41 | 58.96±11.58 | 57.59±12.38 | Time | 0.000 | 0.688 | 0–4weeks: 0.001 |

||

| 4–8weeks: 1.000 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| ML-velocity (mm/s) | DNSG | 2.90±0.45 | 2.31±0.35 | 1.91±0.30 | Group × Time | 0.030 | 0.161 | 0–4weeks: 0.016 |

|

| 4–8weeks: 0.020 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| CG | 2.82±0.31 | 2.02±0.33 | 2.12±0.15 | Time | 0.000 | 0.706 | 0–4weeks: 0.000 |

||

| 4–8weeks: 0.947 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| ML-RMS (mm) | DNSG | 0.20±0.03 | 0.17±0.03 | 0.13±0.02 | Group × Time | 0.009 | 0.208 | 0–4weeks: 0.000 |

|

| 4–8weeks: 0.002 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| CG | 0.20±0.02 | 0.16±0.01 | 0.15±0.02 | Time | 0.000 | 0.840 | 0–4weeks: 0.000 |

||

| 4–8weeks: 0.081 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 |

| Task | Variables | Group | 0 Weeks | 4 Weeks | 8 Weeks | Source | p | ηp2 | Post Hoc |

| EO-BH | AP-Distance (mm) | DNSG | 58.32±9.14 | 49.65±8.24 | 40.35±7.04 | Group × Time | 0.730 | 0.016 | 0–4weeks: 0.103 |

| 4–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.001 | |||||||||

| CG | 57.87±13.51 | 46.13±11.86 | 38.95±5.88 | Time | 0.000 | 0.688 | 0–4weeks: 0.001 |

||

| 4–8weeks: 0.116 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| AP-velocity (mm/s) | DNSG | 1.94±0.30 | 1.58±0.21 | 1.23±0.18 | Group × Time | 0.029 | 0.189 | 0–4weeks: 0.010 |

|

| 4–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| CG | 1.89±0.52 | 1.55±0.36 | 1.56±0.26 | Time | 0.000 | 0.601 | 0–4weeks: 0.001 |

||

| 4–8weeks: 0.942 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.001 | |||||||||

| AP-RMS (mm) | DNSG | 0.17±0.03 | 0.12±0.02 | 0.09±0.01 | Group × Time | 0.590 | 0.026 | 0–4weeks: 0.009 |

|

| 4–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| CG | 0.20±0.04 | 0.14±0.04 | 0.13±0.02 | Time | 0.000 | 0.697 | 0–4weeks: 0.001 |

||

| 4–8weeks: 0.936 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.001 | |||||||||

| ML-Distance (mm) | DNSG | 65.19±13.62 | 45.25±6.79 | 37.86±4.30 | Group × Time | 0.754 | 0.010 | 0–4weeks: 0.003 |

|

| 4–8weeks: 0.001 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| CG | 67.20±11.37 | 45.31±8.75 | 40.83±3.60 | Time | 0.000 | 0.782 | 0–4weeks: 0.000 |

||

| 4–8weeks: 0.371 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| ML-velocity (mm/s) | DNSG | 2.17±0.45 | 1.50±0.22 | 1.33±0.22 | Group × Time | 0.557 | 0.029 | 0–4weeks: 0.003 |

|

| 4–8weeks: 0.189 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| CG | 2.22±0.74 | 1.35±0.34 | 1.23±0.24 | Time | 0.000 | 0.719 | 0–4weeks: 0.001 |

||

| 4–8weeks: 0.889 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.001 | |||||||||

| ML-RMS (mm) | DNSG | 0.18±0.03 | 0.15±0.04 | 0.09±0.00 | Group × Time | 0.000 | 0.326 | 0–4weeks: 0.127 |

|

| 4–8weeks: 0.001 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| CG | 0.17±0.03 | 0.12±0.02 | 0.12±0.02 | Time | 0.000 | 0.737 | 0–4weeks: 0.000 |

||

| 4–8weeks: 1.000 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 |

| Task | Variables | Group | 0 Weeks | 4 Weeks | 8 Weeks | Source | p | ηp2 | Post Hoc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC-BH | AP-Distance (mm) | DNSG | 59.25±9.00 | 50.88±8.38 | 42.04±6.98 | Group × Time | 0.562 | 0.028 | 0–4weeks: 0.157 |

| 4–8weeks: 0.008 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| CG | 57.10±6.05 | 46.25±8.41 | 41.64±6.44 | Time | 0.000 | 0.636 | 0–4weeks: 0.002 |

||

| 4–8weeks: 0.453 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| AP-velocity (mm/s) | DNSG | 1.97±0.30 | 1.62±0.31 | 1.33±0.21 | Group × Time | 0.040 | 0.166 | 0–4weeks: 0.024 |

|

| 4–8weeks: 0.002 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| CG | 1.96±0.30 | 1.54±0.36 | 1.53±0.26 | Time | 0.000 | 0.736 | 0–4weeks: 0.001 |

||

| 4–8weeks: 1.000 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| AP-RMS (mm) | DNSG | 0.15±0.02 | 0.12±0.01 | 0.10±0.02 | Group × Time | 0.382 | 0.047 | 0–4weeks: 0.007 |

|

| 4–8weeks: 0.012 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| CG | 0.18±0.03 | 0.14±0.01 | 0.12±0.01 | Time | 0.000 | 0.688 | 0–4weeks: 0.003 |

||

| 4–8weeks: 0.090 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.002 | |||||||||

| ML-Distance (mm) | DNSG | 65.97±9.61 | 45.27±6.48 | 39.53±6.35 | Group × Time | 0.877 | 0.007 | 0–4weeks: 0.000 |

|

| 4–8weeks: 0.015 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| CG | 67.70±8.67 | 45.07±9.68 | 40.94±8.07 | Time | 0.000 | 0.832 | 0–4weeks: 0.000 |

||

| 4–8weeks: 0.588 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| ML-velocity (mm/s) | DNSG | 2.25±0.20 | 1.51±0.20 | 1.12±0.15 | Group × Time | 0.045 | 0.164 | 0–4weeks: 0.000 |

|

| 4–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| CG | 2.24±0.51 | 1.53±0.41 | 1.55±0.34 | Time | 0.000 | 0.829 | 0–4weeks: 0.001 |

||

| 4–8weeks: 1.000 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.001 | |||||||||

| ML-RMS (mm) | DNSG | 0.16±0.02 | 0.13±0.03 | 0.09±0.01 | Group × Time | 0.002 | 0.273 | 0–4weeks: 0.001 |

|

| 4–8weeks: 0.001 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.000 | |||||||||

| CG | 0.15±0.02 | 0.13±0.03 | 0.13±0.04 | Time | 0.000 | 0.584 | 0–4weeks: 0.317 |

||

| 4–8weeks: 1.000 | |||||||||

| 0–8weeks: 0.214 |

| Task | Group | 0 Weeks | 4 Weeks | 8 Weeks | Source | p | ηp2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AH | DNSG | 6.27±1.42 | 3.63±1.62 | 1.90±1.37 | Group × Time | 0.186 | 0.081 |

| CG | 5.36±0.80 | 3.72±1.00 | 2.18±1.60 | Time | 0.000 | 0.756 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).