1. Introduction

In recent years, the textile industry has promoted sustainable solutions, minimized the usage of synthetic chemicals and explored the eco-friendly alternatives. As a result, there is now a lot of interest in investigating naturally occurring biomaterials, especially when it comes to creative use of biological resources such as insects, which have gained global interest as a potential major source of protein due to the current food scarcity scenario in many developing nations and the prospective challenges of feeding over 9 billion people by 2050 [

1].

Many insects are naturally feed on organic wastes and convert the biomass into nutrients which results in reduction in the amount of waste materials [

2]. Generally, two fly species like the house fly (Musca domestica L.) and the BSF are well known insects for biodegradation of organic waste. The BSF is an insect of the order Diptera belonging to the family Stratiomyidae. BSF has obtained significant recognition as an effective agent in the management of organic waste for its exceptional capacity to convert unused nutrients left in organic waste, such as food waste, animal manure, agricultural residues into their body mass made of lipids, proteins, and chitin [

3,

4,

5].

It is essential to comprehend the biology and life cycle of BSF in order to optimize its use in converting organic waste into valuable products. The duration of each stage varies based on temperature, humidity, and food supply, but BSF survive for 45–50 days [

6]. The BSF life cycle consists of four major stages i.e. eggs, larvae, pupae and adults. The female flies lay a cluster of 500-900 eggs (4-5 days) at a time [

7], laid near the decomposing organic waste. The eggs are further developed into tiny larvae (14-18 days) and which grows rapidly and increases in size [

8]. At this stage, BSF can be reduced up to 80% of the total volume of the organic waste [

9]. Once they reach to maturity, the turn into pupae (7-14 days), dark in color, loss in weight with capsule like in shape [

10]. After this stage, it turns into adult (5-8 days), shiny black and transparent wings and ready to mate and lay eggs for the next generation [

8,

11].

In this work proteins were extracted from BSF larvae, cocoons (the empty cocoons of the pupae) and flies and used as natural dyes for dyeing woolen fabrics. The extraction of BSF protein has typically been conducted using acids [

12], alkalis [

13], enzymatic hydrolysis [

14], and ultrasonication [

15,

16]. There are benefits and drawbacks associated with each of the approach strategies. Some drawbacks of the acid and alkali extraction processes include the use of toxic reagents and the necessity for additional purification procedures, handling challenges, high chemical costs, etc. Despite being a sustainable method, enzyme hydrolysis is not appropriate for industrial scale use due to its high cost and lengthy processing time. Ultra-sonication’s drawbacks include its high energy requirements, which hinder its commercial implementation, its lack of residual effects, and its need for temperature control [

15,

16]. In light of these constraints, this work introduces the utilization of superheated water hydrolysis for the production of protein hydrolysates from BSF. Water under pressure that lies between the atmospheric boiling point of 100 °C and the critical temperature of 374 °C is referred to as superheated water [

17] and it can be used as a green solvent in place of conventional solvents. Superheated water has found widespread application across a variety of industries, including the food, coffee, and waste treatment sectors, among others [

18,

19].

Furthermore, the extraction of natural dyes from BSF with superheated water represents a more sustainable alternative compared to traditional methods based on chemical alkaline agents. This process is able to exploit temperatures above 100 °C and a controlled pressure, making sure that the water acts as a solvent and allowing the selective recovery of a protein hydrolysate without the use of toxic substances [

20]. The advantages that this technology offers are multiple, starting from a greater energy efficiency, due to short times and low electricity consumption, the production of a hydrolysate in aqueous solvent which can be used directly without further purification and the material sterilization. Furthermore, the non-extracted products can be reused in agriculture as fertilizers and finally it guarantees a reduction in waste in terms of raw materials. The use of superheated water for the extraction of natural dyes not only improves production efficiency but also contributes to environmental protection, thus lowering the ecological impact of the entire process.

Wool dying is usually carried out in an aqueous bath at boiling temperature using synthetic dyes such as acid dyes, metal-complex dyes, chrome dyes, reactive dyes although some other more environmentally friendly dyeing methods have been studied [

21].

However, synthetic dyes are substances produced from non-renewable resources, such as oil, coal or natural gas. Despite their innumerable advantages such as low cost, wide range of shades, high resistance to environmental agents and availability, the growing environmental concerns related to their production and disposal has brought back to the fore the interest in natural alternatives, which can derive from plants, fruits, agricultural waste and insects [

22]. For a more sustainable future, the textile sector must continue to invest in sustainable alternatives, promoting a more responsible approach to fabric dyeing. The combination of conscious use of resources and technological innovation will be crucial to creating an eco-friendly production system. Natural alternatives extracted from plants, microbes, and insects are receiving more attention as a result of the growing need for sustainable and eco-friendly colors. Natural dyes have been widely used in dyeing fabrics for centuries, but with the advent of synthetic dyes their use has decreased dramatically. One of the main limitations of natural dyes is their poor affinity with textile fibers, which results in reduced resistance to washing and rubbing. To circumvent this problem and improve color fixation, metallic mordants made of iron and alum have been adopted [

23,

24]. In the context of textile dyeing applications, the protein fraction of BSF has the potential to be one of the choices that can be investigated as a potential natural dye source. In order to promote a more sustainable economy, the current study focuses on the effectiveness of BSF-derived proteins on wool fabric dyeing. One of the objectives of the present study is to evaluate the variations in the type and quantity of extract on color strength and its interaction with the wool fiber. No study has been reported until now on the application of hydrolyzed protein of BSF fractions (larvae, cocoons and flies) as a coloring agent of wool fabrics. The dyeing of wool fabrics was assessed by color strength, washing and rubbing fastness properties on both dry and wet bases, and morphological study by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and optical microscopy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

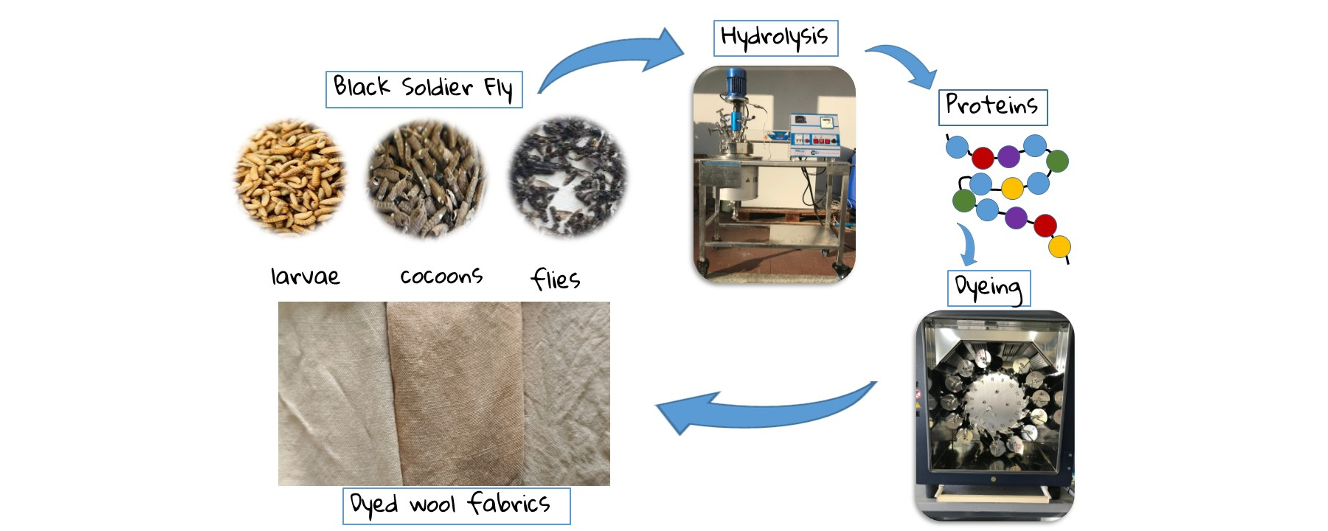

The larvae, cocoons and flies of BSF (

Figure 1) were supplied by the University of Turin, Department of Agricultural, Forest and Food Sciences, Italy. These insects were reared at the Tetto Frati Agrozootechnical Center in Carmagnola (Turin) in a climate-controlled chamber where temperature (29 ± 0.5 °C) and relative humidity (60 ± 5%) are precisely controlled and regulated. A ventilation system ensures a constant flow of air, thus avoiding stratification and ensuring adequate oxygenation and preventing overheating. Ammonia and carbon dioxide levels are also monitored to ensure an optimal environment.

Hexane (C6H14), iron sulfate (FeSO4.7H2O), ECE detergent and sodium perborate (BNaO3·H2O) with a purity of >99% were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The wool fabric was purchased from Ausiliari Tessili Srl, (Cornaredo Milan). All of the chemicals were used as received from the supplier.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. BSF Collection and Preparation

Each BSF sample of larva, cocoon and fly were manually selected by eliminating impurities such as soil or any food scraps. Furthermore, care has been made to prevent picking BSF cocoons or flies when gathering BSF larvae. Each sample were washed three times with distilled water, and dried in an oven at 55 °C for 24 h. After cleaning, each BSF samples were ground coarsely with a home mixer (Bosch MSM66150 Immersion Mixer, 600 W) prior to further analysis and refining.

2.2.2. Moisture, Ash and Lipids Content of BSF

1 g of larvae, cocoons and flies were dried in a vented oven at 105 °C until it reached a consistent weight in order to evaluate the moisture content and the results were then computed using the below formula:

where A

i = initial weight of the BSF samples and A

f = final weight of the BSF samples.

For the ash content determination, 3 g of larvae, cocoons and flies of BSF were taken in the small platinum container and kept in a muffle oven at a temperature of 550 °C for 5 h + 5 h until complete mineralization. The ash content was calculated by using below formula:

where A

f = final weight of the ash and A

i = initial dry weight of the BSF powder sample.

A Soxhlet apparatus was used to extract the lipid content of each BSF sample, which included larvae, cocoons, and flies. Hexane was used as a solvent during the 4 h reflux of the dried BSF powder samples (20–30 g) in cellulose extraction thimbles. The amount of lipids recovered from BSF powder at the end of solvent extraction was estimated and reported to the original dry weight of the BSF powder sample using the formula:

where W

f = weight of the extracted lipids and W

i = initial dry weight of the BSF powder sample.

2.2.3. Superheated Water Hydrolysis of BSF Samples and Protein Amount Determination

The hydrolysis of each defatted BSF sample was conducted in a laboratory scale reactor (Amar Equipment, Mumbai, India, model number 1-T-A-CE) utilizing superheated water. Initially, the larva, cocoon and fly powder (50 g) of BSF after the lipid extraction was introduced into the reactor with one liter water. The experiment was conducted at 170 °C, under a pressure of 7 bar, 403 rpm of stirring speed with a reaction duration of 60 min. The hydrolysis process led in the uniform penetration of water within the BSF powder, followed by maximal protein solubility in water. Each hydrolysate was filtered through a wire mesh, and the protein-rich liquid was subsequently centrifuged 3 times at 8000 rpm for 15 min to eliminate precipitated solid material before being applied to wool fabric for protein hydrolysate coloring. To ascertain the protein hydrolysate concentration for wool fabric coloration, 10 ml from each liquid extract was dried in an oven at 105 °C for 4 h, and the resultant dry weight was recorded.

Moreover, the extraction yield was determined after calculating the final volume of each extract using the formula:

where: W

f: dry weight of hydrolyzed proteins. W

i: dry weight of defatted BSF before hydrolysis.

2.2.4. FTIR Spectroscopy

A Thermo Nicolet iZ10 spectrometer fitted with a Smart Endurance TM (diamond crystal) was used to obtain FTIR spectra in attenuated total reflectance mode. A total of 100 scans were performed with a resolution of 4 cm−1 and a gain of 8.0 in the range of 4000−650 cm−1. The current study examined FTIR spectra of original insect material, ashes and dry hydrolyzed proteins from larvae, cocoons and flies.

2.2.3. Wool Fabric Coloration

The protein hydrolysate obtained was used for wool fabric coloration. For coloration, previous optimized parameters [

17] such as temperature of 90 °C, material to liquor ration (MLR) of 1:40, processing time of 60 min were used. The pH of the dye bath was set to 4.5 which corresponds to the isoelectric point of the wool fiber. To investigate the effect of protein hydrolysate concentration on dyeing of wool fabrics, five sets of different protein hydrolysate concentrations i.e. 2%, 5%, 10%, 30% and 50% o.w.f. were used. The dying of wool fabric using protein hydrolysate was performed in a Datacolor Ahiba Nuance Top Speed II rotary dyeing machine. To enhance the dye uptake capacity of wool fiber, mordant of iron sulphate at a fixed quantity of 5% o.w.f. was used using a meta mordanting technique. After dyeing, fabric samples were washed with cold and hot water, then soaped with 2 g/L non ionic soap at 90-95 °C for 10 min, rinsed with cold water, and dried at room temperature.

2.2.4. Dyed Wool Fabric Characterization

A Data Color Spectro Flash SF 600X was used to assess the dyed samples’ color strength (K/S). The K/S values are derived from the Kubelka–Munk theory, in which the connection between the absorption coefficient (K), the scattering coefficient (S), and the fabric reflectance at maximum absorption (R) is defined by the equation shown below.

where: K = the absorption coefficient; S = the scattering coefficient; R = the reflectance of fabric at maximum absorption.

The dyed samples’ color fastness to washing was determined according to the UNI EN ISO 105 C06 standard (UNI EN ISO 105-C06: Textiles Tests for color fastness Part C06: Color fastness to domestic and commercial laundry). The UNI EN ISO 105-X12 standard (Textiles Tests for Color Fastness. Part X12: Color fastness to rubbing) was used to measure both dry and wet rubbing fastness.

A EVO 10 SEM (CarlZeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany) was used to perform morphological analyses on samples of wool fabric dyed with and without mordant at different concentrations of protein hydrolysate. The samples were compared to a reference original wool fabric. The following parameters were set: working distance of 30 mm, acceleration voltage of 15 kV, and current probe of 50 pA. Aluminium specimen stubs were used to mount the samples using double-sided adhesive tape. The samples were sputter-coated with a 20-30 nm thick gold layer in rarefied argon using a sputter coater at a current intensity of 20 mA for 4 min.

The internal structure and distribution of the dye into the fibers were visualized using a light microscope Leica DMLP in wool samples treated with the different protein hydrolysates of larvae, cocoons and flies for comparison with wool sample before dying.

The preparation of the fiber cross-sections was carried out by the use of a manual microtome for fibers, incorporated and held adhered with a collodion solution. Glycerin triacetate was used as dispersion reagent.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. BSF Composition

Table 1 shows the humidity, ash and lipid content of larvae, cocoons and flies of BSF. The amounts of ash determined in the larvae, cocoons and flies of 11.0%, 8.3% and 12.9% w/w respectively are in agreement with results obtained by other authors in the different stages of BSF development [

8,

20,

25].

It is worth highlighting the high lipid content of larvae and flies (22.47% w/w and 21.21% w/w respectively) which can be considered excellent sources of fats for the biodiesel production [

25,

26] while the lipids amount in cocoons is much lower (4.39% w/w) in accordance with results obtained by Frike et al. [

27].

3.2. Extraction Yield of Hydrolyzed Proteins

In

Table 2 protein hydrolysate concentration and extraction yield of different materials of BSF are shown. The concentration of protein hydrolysate in water after superheated water hydrolysis is used to calculate the amount of hydrolysate to be placed as a dye in the dye baths. The extraction yield of proteins after lipid extraction shows that high amounts of protein extractable with superheated water are present in larvae and flies as already evidenced in other works [

28]. In defatted cocoons, however, the extraction yield of the protein hydrolysate is much more limited in accordance with the results obtained by Fricke et al. [

27].

3.3. FTIR Analysis

In order to obtain biochemical information of the BSF insect material samples, the FTIR analysis was applied to the initial sample of larvae, cocoons, and flies of BSF. The FTIR analysis give solid information about molecular composition starting from the absorptions from the functional groups in the mid-infrared spectrum, which can help to direct towards different technological applications.

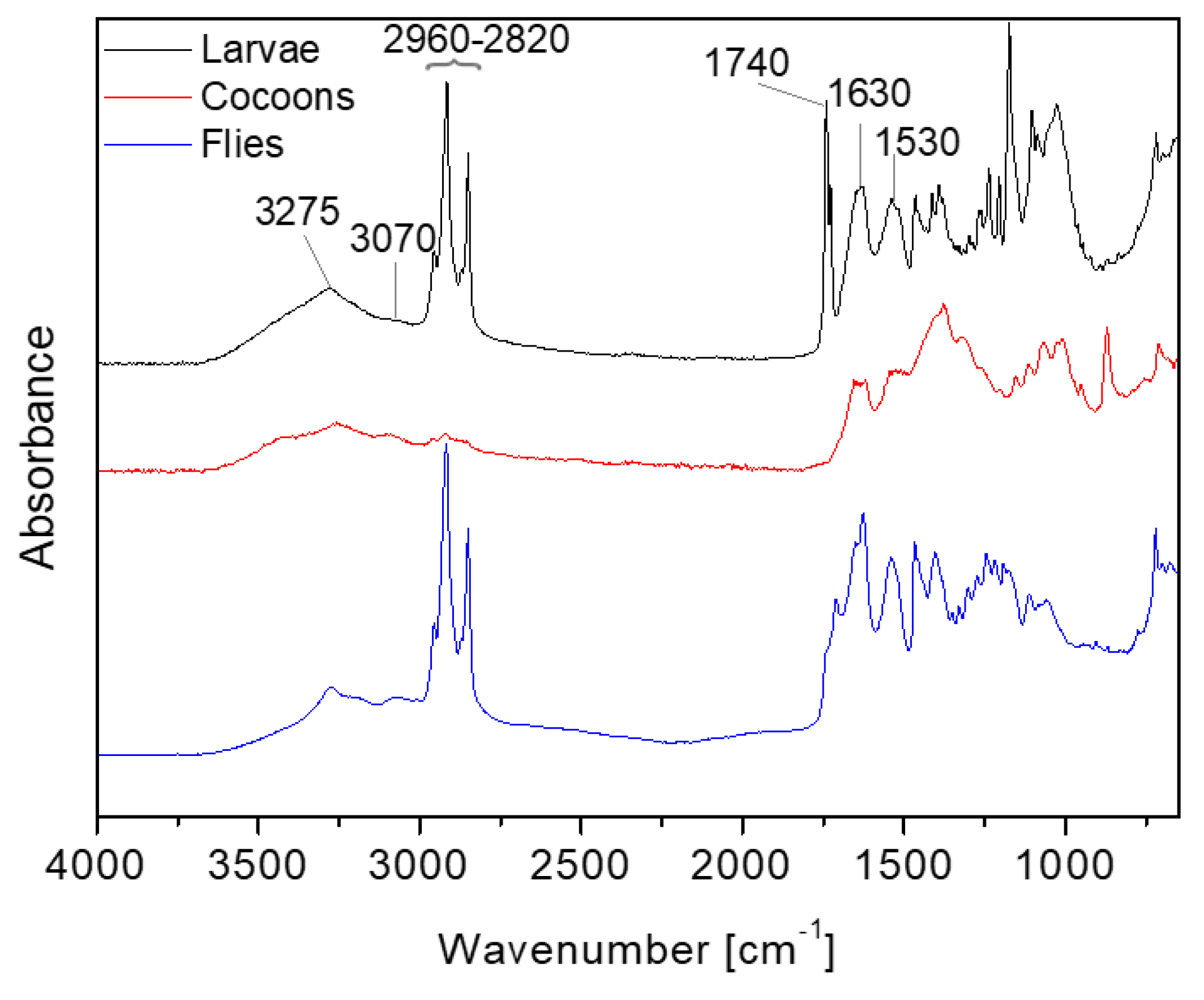

Results obtained are depicted in

Figure 2 where the different compositions of the BSF are clearly visible in the different insect materials. In larvae and flies, the peaks of amides (Amide A at 3275 cm

-1, Amide B at 3070 cm

-1, Amide I at 1630 cm

-1 and Amide II at 1530 cm

-1) attributable to the presence of proteins and the absorption peaks of the -CH

2 and -CH

3 from lipids in the range 2960-2820 cm

-1 appear evident. In cocoons, lipid absorptions are less evident while protein amide absorptions overlap with chitin amide peaks [

29] confirming the low amount of proteins and lipids present in cocoons.

Moreover in the FTIR spectra of the larvae the presence of the strong absorption at 1740 cm-1 attributable to the stretching of the C=O carbonyl group indicates the presence of the ester group in triglycerides.

To better investigate the chemical composition of the different stages of BSF, the spectra of ash, lipids and proteins were acquired.

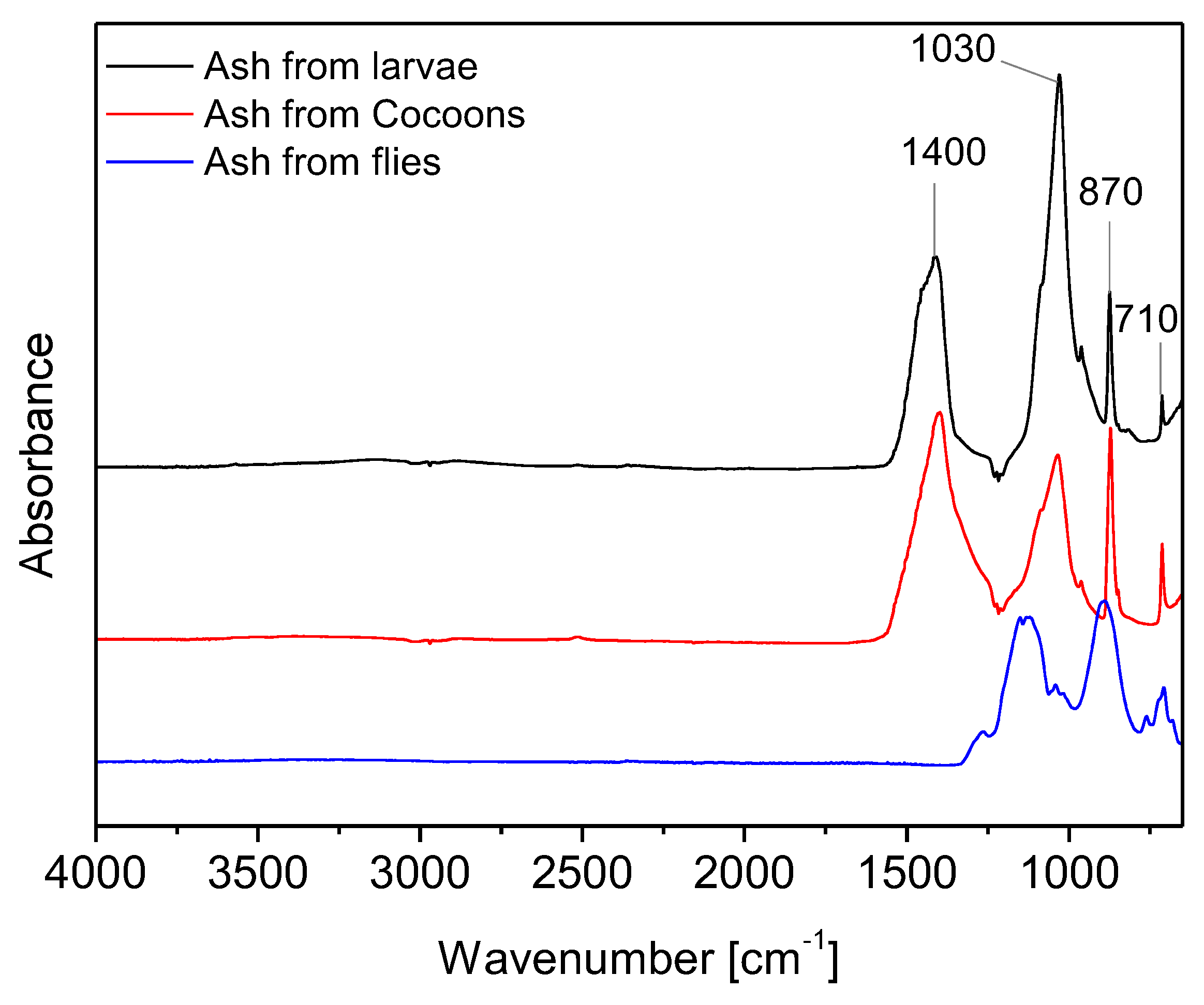

Figure 3 shows the ash spectrum in larva, cocoon and fly samples. Although the different insect material shows quite similar ash content values the spectra of ash in larvae and cocoons are different from ash spectrum in flies. Ash spectra of larvae and cocoons show the peaks characteristic of calcite [

20,

30]. In particular, the peak at 1400 cm⁻¹ is attributed to the asymmetric CO₃ stretching band, while the band at 1030 cm⁻¹ is attributed to the symmetric CO₃ stretching band. Additionally, the band at 870 cm⁻¹ is attributed to the out-plane bending of CaO, and the band at 710 cm⁻¹ is attributed to the in-plane bending of CaO [

31]. In adult flies a different mineral composition is detected as highlighted by other authors which assert that BSF flies contain very little Ca since Ca remains concentrated in the cocoons [

8].

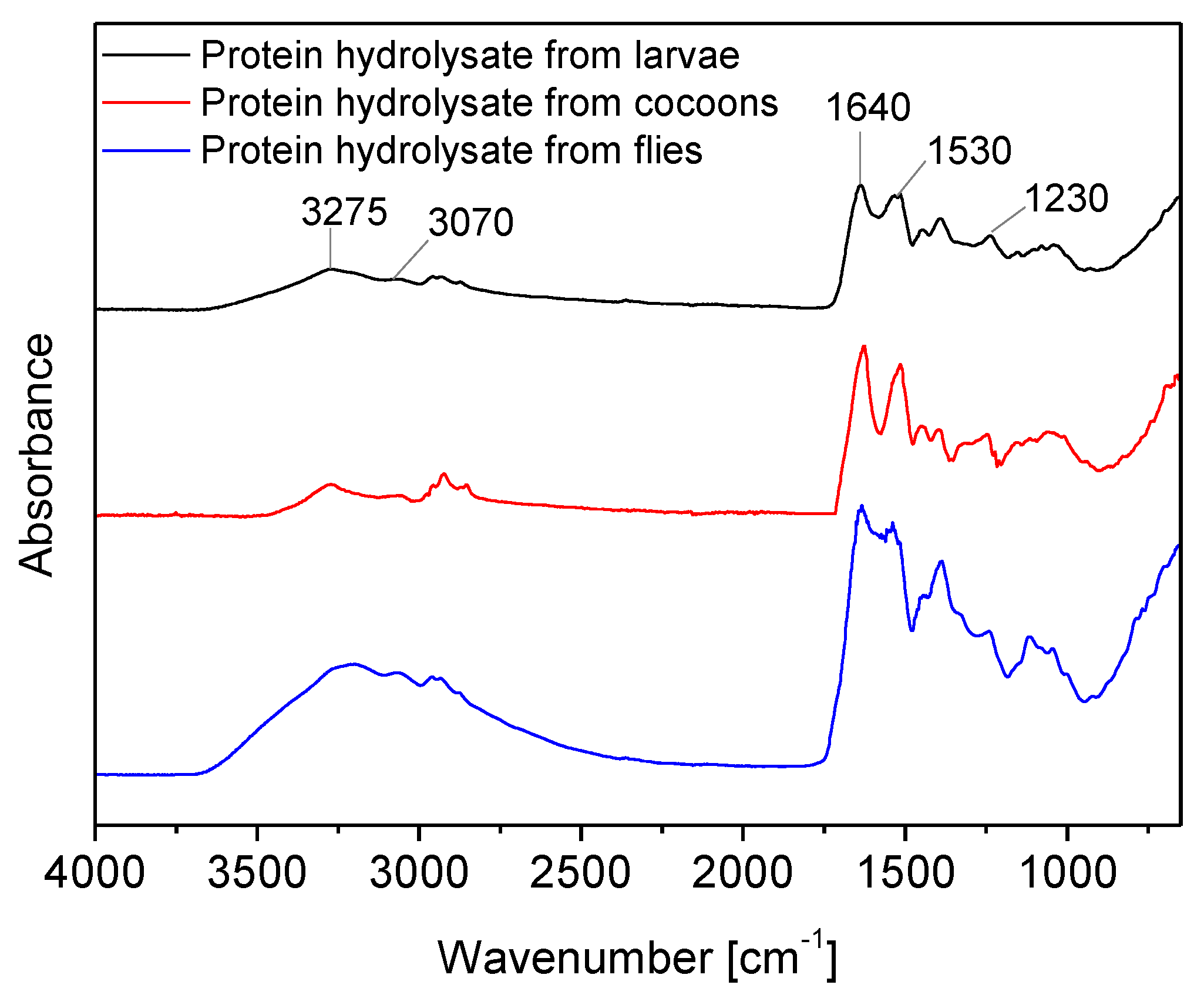

Finally, the FTIR spectra of hydrolysates with superheated water after drying by BSF larvae, cocoons and flies are quite similar and confirm their prevalent protein composition.

From the

Figure 4, it is clearly indicated that distinct FTIR spectra regions can be identified corresponding to the amide group due to the presence of peptide bonds between amino acids. These characteristics bands correspond to the Amide I at 1640 cm

−1 (C=O stretching), Amide II at 1530 cm

−1 (C=N stretching and N-H bending), and Amide III at 1230 cm

−1 (C-N stretching and N-H bending). Moreover, the Amide A band identified at 3275 cm⁻¹ and Amide B at 3070 cm⁻¹, which are caused by the N-H stretching and C-H stretching, respectively, are also visible [

28,

32].

3.4. Wool Fabric Dyeing

The dyeing of wool fabrics using proteins extracted from various stages of BSF, i.e. larvae, cocoons, and flies, as a dyes was studied and the fabric color strength and color fastness were measured by varying the concentration of the dye (2%, 5%, 10% 30% and 50% o.w.f.) with and without ferrous sulphate used as mordant. Morphological characterizations of dyed fabrics have also been performed.

3.4.1. Color Strength

Results from color strength (K/S value) of dyed wool fabrics without mordant were shown in

Table 3.

It is clearly observed that as the proteins dye concentration increases from 2% to 50% (o.w.f.), the color strength (K/S value) of dyed wool fabrics also increases from 0.32 to 1.44 when the fabrics are treated with mordant-free protein hydrolysate derived from larvae, indicating a direct relationship between protein concentration and wool fabric color strength. Hydrolysates from cocoons and flies also show a similar trend, but their K/S values are higher than the K/S values of wool fabrics dyed with protein larvae-extracted dye at all concentration (

Figure 5).

The maximum K/S value of 2.78 was obtained using cocoons protein hydrolysate, while the maximum K/S value of 2.00 was obtained using protein fly hydrolysate, both without the use of mordant. The coloration obtained could be due to two main factors: (1) melanin pigment, which is widely present in flies and cocoons [

33], and (2) the Maillard process, a well-known browning reaction that occurs when amino acids and reducing sugars are heated, resulting in the creation of brown chemicals [

34]. The lower melanin content of the larvae most likely explains the lower color strength compared to other biomass sources. The color strength of wool fabrics dyed with protein hydrolysates derived from BSF biomass is in the order protein hydrolysate from cocoons > flies > larvae when no mordant is used (

Figure 6).

When iron sulfate is used in the dyeing bath as a mordant at the concentration of 5% o.w.f. it is highlighted a decreasing trend in K/ S value from 3.0 to 1.79 in wool fabrics treated whit the dye extracted from larvae with an increase in hydrolysate concentration from 2% to 50% o.w.f. (

Table 4). Similar trends were observed for wool fabrics dyed with protein hydrolysate from cocoons and flies. The color strength of wool fabrics dyed with protein hydrolysate from cocoons initially decreased from 2.73 to 2.05 as the protein hydrolysate concentration increased from 2% to 10%. However, with a further increase in the hydrolysate concentration from 30% to 50%, the color strength of the wool fabrics increased from 2.28 to 2.71 (

Figure 7). Similarly, the K/S value of fly protein hydrolysate dyed tissues initially decreases from 2.31 to 1.67 when the protein hydrolysate concentration increases from 2% to 10% and then increases to 1.98% with increasing protein hydrolysate concentration at 50%. It is important to keep in mind that ferrous sulfate used as a mordant has the effect of fixing natural dyes on textile fibers and altering their hues, making the colors darker. High K/S values with mordant at low protein concentration may be due to the ferrous sufate, which anchor the dye to the fabric and also darken the shades. Overall, the results show the effectiveness of protein hydrolysate and mordant in dyeing wool, and that the protein hydrolysate from cocoons showed the highest K/S values.

3.4.2. Color Fastness to Washing

The grades of the color fastness to washing of dyed wool fabrics for 50% o.w.f. protein hydrolysate concentration from larvae, cocoons, and flies with and without mordant have been given in

Table 5. From the table it can be seen that the color fastness to washing is good (grade 4) for wool fabrics dyed using protein hydrolysates from larvae and cocoons in the absence of mordant and lower for protein hydrolysates from flies probably due to the presence of melanin in the extracted color which does not interact with the wool fibers. Furthermore, there were no discharges of dye on synthetic fibers and wool (where the grades recorded were 5 or 4/5) and an acceptable discharge on cotton fabrics. The presence of ferrous sulfate as mordant in the dyeing recipe does not seem to improve the results obtained.

3.4.3. Color Fastness to Rubbing

Dry and wet rubbing of wool fabrics dyed with BSF protein hydrolysate was studied to understand the resistance of a dyed fabric to fading or discoloration under rubbing. The results are shown in

Table 6.

Color dry rubbing fastness was found in the range 4-5, therefore from good to very good for wool fabrics dyed without mordant. The presence of ferrous sulfate seems not to improve the results obtained. The wet rubbing fastness values are slightly lower than values obtained from dry rubbing as expected [

21]. Overall, good to medium color fastness to dry and wet rubbing was achieved with this natural dye.

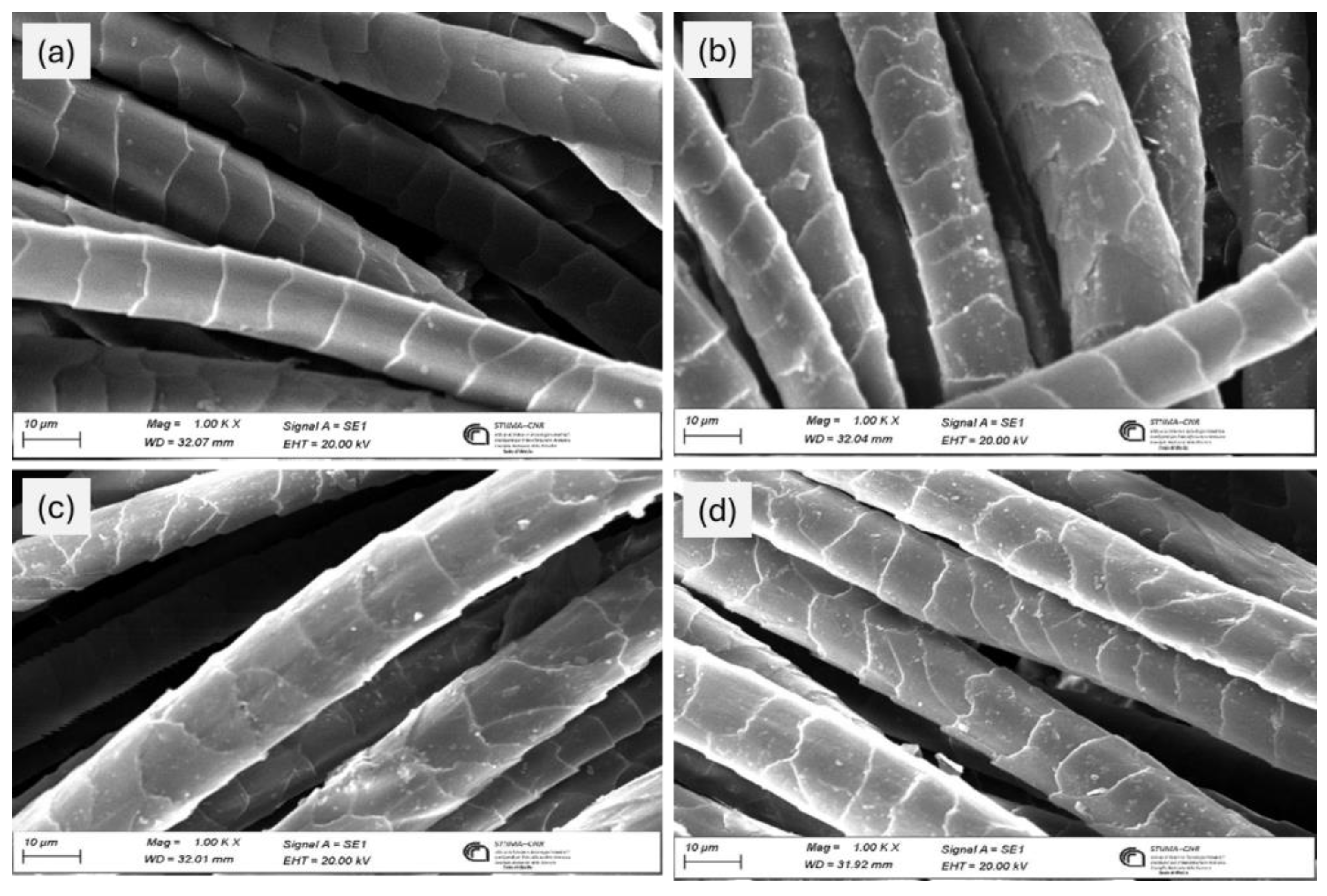

3.5. Morphological Characterization of Dyed Wool Fabrics

Wool fabric samples dyed with protein hydrolysate from BSF were characterized using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) at 1000x magnification to evaluate the fiber surface morphology (see

Figure 8). From the figure, it can be easily observed that the untreated reference wool fabric (

Figure 8a) has a smooth, intact surface with distinct cuticular cells, characteristic of the natural morphology of wool [

35]. However, after dyeing with BSF-derived protein hydrolysates with and without mordant, slight alterations were found in the cuticle region: wool fibers appeared partially rough with deposits on the surface which can be attributed to fragments of BSF-derived hydrolyzed proteins and the residual ferrous sulfate mordant.

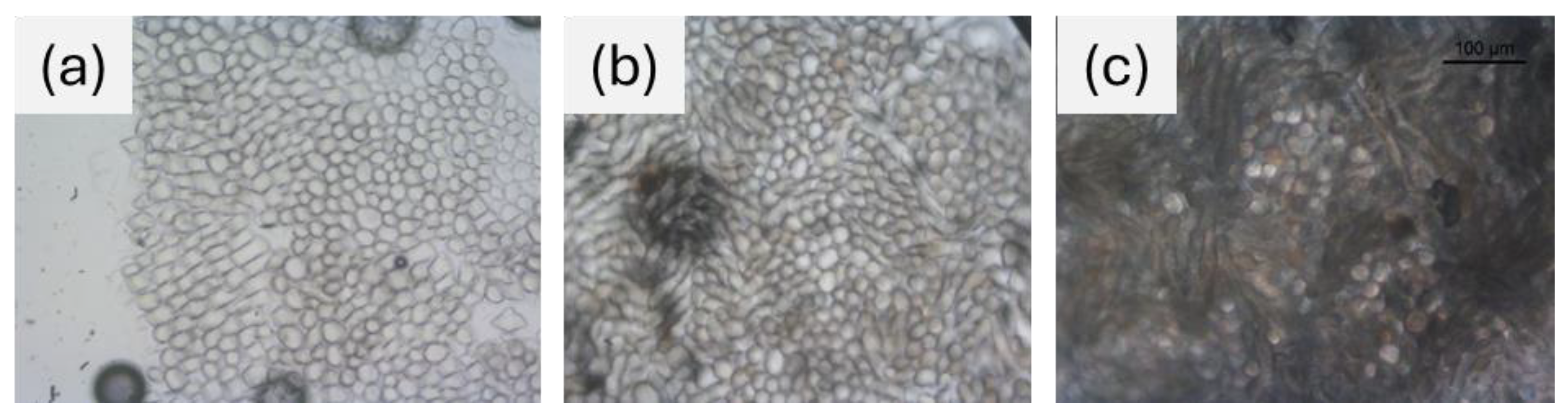

Cross-sections of dyed wool fabrics for comparison with undyed reference fabric were examined under the light microscope, as shown in

Figure 9. The pictures revealed that the internal part of the dyed wool fibers appeared visibly darker than the untreated wool fiber, both with and without mordant. This highlights that the dye and mordant have penetrated the internal matrix of the fiber, through the amorphous regions that allow molecular diffusion [

36].

4. Conclusions

The present work clearly demonstrates that the protein hydrolysates derived from BSF larvae, cocoons and flies can be used as natural colors for wool dyeing. The process was combined by the economically viable use of superheated water hydrolysis to extract protein hydrolysate from BSF biomass. Different insect materials i.e. larvae, cocoons and flies were characterized for moisture (7.3%, 9.2% and 9.8% respectively), ash (11.0%, 8.3% and 12.9%) and lipid content (22.47%, 4.39%, and 21.21%). The highest protein yield was observed to be 47.6%, from larvae, followed by a slightly lower protein yield of 47.4% in flies and the lowest protein yield was 19.3%, obtained in cocoons. Protein hydrolysate concentrations ranging from 2% to 50% o.w,f. with and without a 5% iron sulfate fixed mordant were applied for dyeing wool fabrics. Fabrics treated with protein hydrolysate from larvae without mordant show an increase in K/S values from 0.32 to 1.44 as the dye concentration increases from 2% to 50%. Fabrics dyed with protein hydrolysates from cocoons and flies show a similar pattern, but their K/S values are higher at all concentrations than the K/S values of wool fabrics dyed with protein hydrolysates extracted from larvae.

Furthermore, it has been highlighted that the mordant is more effective at lower concentrations of dye. High K/S values with mordant may be due to dye anchoring or ferrous sulfate, which darkens the shades. The color fastness to washing tests gave good to poor results as a color change on dyed fabrics and good to excellent grades as a color release on the other fabrics, particularly on wool and man-made fibers. The dry and wet rubbing color fastness tests showed variable degrees of color discharge on the reference abrading fabric. Scanning electron microscope analysis of the fabrics showed deposits of dye and mordant on the dyed wool fabrics, while optical microscope analysis of the dyed wool fiber cross-section confirmed that the dye entered the fibers through the amorphous regions and spread homogeneously within the fibers. Overall, the protein fraction of BSF was found to be an efficient and sustainable coloring agent. The described technique helps replace synthetic chemical dyes in production with renewable and biodegradable alternatives, which not only encourages the valorization of insect biomass but also is obtained from insects that are used for the disposal of organic waste.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z, P.B. and S.D.V.; methodology, A.V.M. and P.B.; software, G.D.F..; validation, A.V.M., and M.A.; formal analysis, M.A. and G.D.F; investigation, A.V.M. and M.A.; resources, G.D.F.; data curation, A.V.M.; writing – original draft preparation, A.V.M. and M.A.; writing – review & editing, M.Z and S.D.V.; visualization, G.D.F.; supervision, M.Z. and S.D.V.; project administration, M.Z.; funding acquisition, M.Z.

Funding

The authors thank for the financial support of the project HI-Tech “Hermetia illucens biofactory: from waste to high value technological products” (PRIN 2022 20229T94FL ¬ D.D. MUR n.104 02/02/2022, Italy).

Data Availability Statement

All the data will be made available on specific request.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Prof. Laura Gasco from the University of Turin for supplying the larvae, cocoons and flies of BSF used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BSF |

Black Soldier Fly |

| o.w.f. |

on weight fibers |

| SEM |

Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| rpm |

rotation per minute |

| FTIR |

Fourier Transform InfraRed |

| MLR |

Material to Liquor Ratio |

| UNI |

Italian Standard Body |

| ISO |

International Organization for Standardization |

References

- Aguilar-Toalá, J.E.; Vidal-Limón, A.M.; Liceaga, A.M. Advancing Food Security with Farmed Edible Insects: Economic, Social, and Environmental Aspects. Insects 2025, 16, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Harahap, I.A.; Osei-Owusu, J.; Saikia, T.; Wu, Y.S.; Fernando, I.; Perestrelo, R.; Câmara, J.S. Bioconversion of organic waste by insects – A comprehensive review. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 187, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poveda, J. Insect frass in the development of sustainable agriculture. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 41, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Tafi, E.; Paul, A.; Salvia, R.; Falabella, P.; Zibek, S. Current state of chitin purification and chitosan production from insects. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2020, 95, 2775–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainol Abidin, N.A.; Kormin, F.; Zainol Abidin, N.A.; Mohamed Anuar, N.A.F.; Abu Bakar, M.F. The Potential of Insects as Alternative Sources of Chitin: An Overview on the Chemical Method of Extraction from Various Sources. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, M.; Shahzadi, A.; Zheng, H.; Alam, F.; Nabi, G.; Dezhi, S.; Ullah, W.; Ammara, S.; Ali, N.; Bilal, M. Effect of different environmental conditions on the growth and development of Black Soldier Fly Larvae and its utilization in solid waste management and pollution mitigation. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 28, 102649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, D.C.; Tomberlin, J.K.; Joyce, J.A.; Kiser, B.C.; Sumner, S.M. Rearing Methods for the Black Soldier Fly (Diptera: Stratiomyidae). J. Med. Entomol 2002, 39, 695–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragan-Fonseca, K.B.; Dicke, M.; van Loon, J.J.A. Nutritional value of the black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens L.) and its suitability as animal feed – a review. J. Insects as Food Feed 2017, 3, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, S.; Zurbrügg, C.; Tockner, K. Conversion of organic material by black soldier fly larvae: establishing optimal feeding rates. Waste Manag. Res. J. a Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2009, 27, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesan, A.R.; Mohan, K.; Kandasamy, S.; Surendran, R.P.; Kumar, R.; Rajan, D.K.; Rajarajeswaran, J. Food waste-derived black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) larval resource recovery: A circular bioeconomy approach. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 184, 170–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedalmoosavi, M.M.; Mielenz, M.; Veldkamp, T.; Daş, G.; Metges, C.C. Growth efficiency, intestinal biology, and nutrient utilization and requirements of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) larvae compared to monogastric livestock species: a review. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 13, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longvah, T.; Mangthya, K.; Ramulu, P. Nutrient composition and protein quality evaluation of eri silkworm (Samia ricinii) prepupae and pupae. Food Chem. 2011, 128, 400–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, J.A.; Guo, X.; Pichner, R.; Aganovic, K.; Heinz, V.; Hollah, C.; Miert, S.V.; Verheyen, G.R.; Juadjur, A.; Rehman, K.U. Evaluation of nutritional and techno-functional aspects of black soldier fly high-protein extracts in different developmental stages. animal 2025, 19, 101463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouithys-Mickalad, A.; Schmitt, E.; Dalim, M.; Franck, T.; Tome, N.M.; van Spankeren, M.; Serteyn, D.; Paul, A. Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) Larvae Protein Derivatives: Potential to Promote Animal Health. Animals 2020, 10, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xiao, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, B.; Cai, Y.; Hu, W. Comparative study of the effects of ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction on black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) larvae protein: Nutritional, structural, and functional properties. Ultrason. Sonochem 2023, 101, 106662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Queiroz, L.S.; Marie, R.; Nascimento, L.G.L.; Mohammadifar, M.A.; de Carvalho, A.F.; Brouzes, C.M.C.; Fallquist, H.; Fraihi, W.; Casanova, F. Gelling properties of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) larvae protein after ultrasound treatment. Food Chem. 2022, 386, 132826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavsar, P.; Dalla Fontana, G.; Tonin, C.; Patrucco, A.; Zoccola, M. Superheated water hydrolyses of waste silkworm pupae protein hydrolysate: A novel application for natural dyeing of silk fabric. Dye. Pigment. 2020, 183, 108678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chindapan, N.; Soydok, S.; Devahastin, S. Roasting Kinetics and Chemical Composition Changes of Robusta Coffee Beans During Hot Air and Superheated Steam Roasting. J. Food Sci. 2019, 84, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhaliwal, H.K.; Sonkar, S.; V, P.; Puente, L.; Roopesh, M.S. Process Technologies for Disinfection of Food-Contact Surfaces in the Dry Food Industry: A Review. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhavsar, P.S.; Dalla Fontana, G.; Zoccola, M. Sustainable Superheated Water Hydrolysis of Black Soldier Fly Exuviae for Chitin Extraction and Use of the Obtained Chitosan in the Textile Field. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 8884–8893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavsar, P.S.; Zoccola, M.; Patrucco, A.; Montarsolo, A.; Mossotti, R.; Giansetti, M.; Rovero, G.; Maier, S.S.; Muresan, A.; Tonin, C. Superheated Water Hydrolyzed Keratin: A New Application as a Foaming Agent in Foam Dyeing of Cotton and Wool Fabrics. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 9150–9159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegbe, E.O.; Uthman, T.O. A review of history, properties, classification, applications and challenges of natural and synthetic dyes. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulo, B.; De Somer, T.; Phan, K.; Roosen, M.; Githaiga, J.; Raes, K.; De Meester, S. Evaluating the potential of natural dyes from nutshell wastes: Sustainable colouration and functional finishing of wool fabric. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2022, 34, e00518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahmoradi Ghaheh, F.; Moghaddam, M.K.; Tehrani, M. Comparison of the effect of metal mordants and bio-mordants on the colorimetric and antibacterial properties of natural dyes on cotton fabric. Color. Technol. 2021, 137, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smets, R.; Goos, P.; Claes, J.; Van Der Borght, M. Optimisation of the lipid extraction of fresh black soldier fly larvae (Hermetia illucens) with 2-methyltetrahydrofuran by response surface methodology. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 258, 118040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, C.; Le, T.M.; Pham, C.D.; Duong, Y.; Le, P.T.K.; Tran, T.V. Valorization of Black Soldier Flies at Different Life Cycle Stages. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2022, 97, 139–144 SE-Research Articles. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, E.; Saborowski, R.; Slater, M.J. Utility of by-products of black soldier fly larvae ( Hermetia illucens ) production as feed ingredients for Pacific Whiteleg shrimp ( Litopenaeus vannamei ). J. World Aquac. Soc. 2024, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pasquale, A.; Zoccola, M.; Mohod, A.; Dalla Fontana, G.; Anceschi, A.; Dalle Vacche, S. From Waste to Technological Products: Bioplastics Production from Proteins Extracted from the Black Soldier Fly. Polymers (Basel) 2025, 17, 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Sun, J.; Yu, L.; Zhang, C.; Bi, J.; Zhu, F.; Qu, M.; Jiang, C.; Yang, Q. Extraction and Characterization of Chitin from the Beetle Holotrichia parallela Motschulsky. Molecules 2012, 17, 4604–4611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebora, M.; Salerno, G.; Piersanti, S.; Saitta, V.; Morelli Venturi, D.; Li, C.; Gorb, S. The armoured cuticle of the black soldier fly Hermetia illucens. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinti, A.; Tugnoli, V.; Bonora, S.; Francioso, O. Recent applications of vibrational mid-Infrared (IR) spectroscopy for studying soil components: a review. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2015, 16, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, L.S.; Regnard, M.; Jessen, F.; Mohammadifar, M.A.; Sloth, J.J.; Petersen, H.O.; Ajalloueian, F.; Brouzes, C.M.C.; Fraihi, W.; Fallquist, H.; et al. Physico-chemical and colloidal properties of protein extracted from black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) larvae. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 186, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ushakova, N.; Dontsov, A.; Sakina, N.; Bastrakov, A.; Ostrovsky, M. Antioxidative Properties of Melanins and Ommochromes from Black Soldier Fly Hermetia illucens. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Hosry, L.; Elias, V.; Chamoun, V.; Halawi, M.; Cayot, P.; Nehme, A.; Bou-Maroun, E. Maillard Reaction: Mechanism, Influencing Parameters, Advantages, Disadvantages, and Food Industrial Applications: A Review. Foods 2025, 14, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoccola, M.; Bhavsar, P.; Anceschi, A.; Patrucco, A. Analytical Methods for the Identification and Quantitative Determination of Wool and Fine Animal Fibers: A Review. Fibers 2023, 11, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Wang, W.; Gong, K.; Hurren, C.J.; Li, Q. Ultrasonic scouring as a pretreatment of wool and its application in low-temperature dyeing. Text. Res. J. 2019, 89, 1975–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Different BSF insect materials.

Figure 1.

Different BSF insect materials.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of BSF larvae, cocoons and flies.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of BSF larvae, cocoons and flies.

Figure 3.

FTIR spectra of ash from BSF larvae, cocoons and flies.

Figure 3.

FTIR spectra of ash from BSF larvae, cocoons and flies.

Figure 4.

FT-IR spectra of the BSF protein hydrolysate from larvae, cocoons and flies.

Figure 4.

FT-IR spectra of the BSF protein hydrolysate from larvae, cocoons and flies.

Figure 5.

Wool fabric dyed with protein hydrolysate from BSF cocoons without mordant; dye protein concentration 2%, 5%, 10%, 30%, 50% w/w o.w.f. from left to right.

Figure 5.

Wool fabric dyed with protein hydrolysate from BSF cocoons without mordant; dye protein concentration 2%, 5%, 10%, 30%, 50% w/w o.w.f. from left to right.

Figure 6.

Wool fabrics dyed with protein hydrolysate at the 50% o.w.f. concentration without mordant obtained from larvae, cocoons and flies from left to right.

Figure 6.

Wool fabrics dyed with protein hydrolysate at the 50% o.w.f. concentration without mordant obtained from larvae, cocoons and flies from left to right.

Figure 7.

Wool fabric dyed with protein hydrolysate from BSF cocoons with 5% o.w.f. mordant; dye protein concentration 2%, 5%, 10%, 30%, 50% w/w o.w.f. from left to right.

Figure 7.

Wool fabric dyed with protein hydrolysate from BSF cocoons with 5% o.w.f. mordant; dye protein concentration 2%, 5%, 10%, 30%, 50% w/w o.w.f. from left to right.

Figure 8.

SEM pictures of (a) untreated wool fabric, (b) fabric treated with larva protein hydrolysate, (c) fabric treated with cocoon protein hydrolysate, (d) fabric treated with fly protein hydrolysate and mordant.

Figure 8.

SEM pictures of (a) untreated wool fabric, (b) fabric treated with larva protein hydrolysate, (c) fabric treated with cocoon protein hydrolysate, (d) fabric treated with fly protein hydrolysate and mordant.

Figure 9.

Optical microscopy picture of cross-section of (a) undyed reference wool, (b) wool dyed with 50% protein hydrolysate, without mordant, (c) wool dyed with protein hydrolysate with mordant (100 x).

Figure 9.

Optical microscopy picture of cross-section of (a) undyed reference wool, (b) wool dyed with 50% protein hydrolysate, without mordant, (c) wool dyed with protein hydrolysate with mordant (100 x).

Table 1.

Moisture, ash and lipid content of BSF insect material.

Table 1.

Moisture, ash and lipid content of BSF insect material.

| Sample |

Moisture

(% w/w) |

Ash

(% w/w) |

Lipid

(% w/w) |

| Larvae |

7.3±0.46 |

11.0±0.44 |

22.47±0.52 |

| Cocoons |

9.2±0.55 |

8.3±0.33 |

4.39±0.32 |

| Flies |

9.8±0.35 |

12.9±0.58 |

21.21±0.23 |

Table 2.

Protein hydrolysate concentration and extraction yield.

Table 2.

Protein hydrolysate concentration and extraction yield.

| |

Larvae |

Cocoons |

Flies |

| Protein hydrolysate concentration (g/L) |

22.05 |

14.5 |

26.4 |

| Extraction yield (% w/w) |

47.6 |

19.3 |

47.4 |

Table 3.

Color strength of wool fabrics dyed with protein hydrolysates obtained from BSF without mordant.

Table 3.

Color strength of wool fabrics dyed with protein hydrolysates obtained from BSF without mordant.

Protein

concentration (%) |

K/S |

| Larvae |

Cocoons |

Flies |

| 2 |

0.32 |

0.43 |

0.40 |

| 5 |

0.53 |

0.83 |

0.6 |

| 10 |

0.90 |

1.29 |

0.95 |

| 30 |

1.18 |

2.25 |

1.69 |

| 50 |

1.44 |

2.78 |

2.00 |

Table 4.

Color strength of wool fabrics dyed with protein hydrolysates obtained from BSF with 5% o.w.f. mordant.

Table 4.

Color strength of wool fabrics dyed with protein hydrolysates obtained from BSF with 5% o.w.f. mordant.

Protein

concentration (%) |

K/S |

| Larvae |

Cocoons |

Flies |

| 2 |

3.00 |

2.73 |

2.31 |

| 5 |

2.57 |

2.24 |

1.83 |

| 10 |

2.11 |

2.05 |

1.67 |

| 30 |

1.86 |

2.28 |

1.79 |

| 50 |

1.79 |

2.71 |

1.98 |

Table 5.

Color fastness to washing of wool fabrics dyed with 50% o.w.f. protein hydrolysate from larvae, cocoons and flies with and without mordant.

Table 5.

Color fastness to washing of wool fabrics dyed with 50% o.w.f. protein hydrolysate from larvae, cocoons and flies with and without mordant.

| Protein hydrolysates from sample |

Mordant (%) |

Colour change |

Acetate |

Cotton |

Polyamide |

Polyester |

Acrylic |

Wool |

| Larvae |

5 |

3 |

5 |

3/4 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

4/5 |

| Cocoons |

5 |

1 |

5 |

3/4 |

4/5 |

5 |

5 |

4/5 |

| Flies |

5 |

2 |

5 |

3/4 |

4/5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| Larvae |

No |

4 |

4/5 |

3/4 |

4/5 |

4/5 |

4/5 |

4/5 |

| Cocoons |

No |

4 |

5 |

4/5 |

4/5 |

4/5 |

5 |

4/5 |

| Flies |

No |

2 |

5 |

4/5 |

4/5 |

4/5 |

5 |

5 |

Table 6.

Color fastness to dry and wet rubbing of wool fabrics dyed with 50% o.w.f. protein hydrolysate from larvae, cocoons and flies with and without mordant.

Table 6.

Color fastness to dry and wet rubbing of wool fabrics dyed with 50% o.w.f. protein hydrolysate from larvae, cocoons and flies with and without mordant.

| |

Grade |

| |

Without mordant |

With mordant |

| Color change |

Color from larvae |

Color from cocoons |

Color from

flies |

Color from larvae |

Color from cocoons |

Color from

flies |

| Dry |

4 |

4/5 |

5 |

4/5 |

3/4 |

4/5 |

| Wet |

3/4 |

3 |

4 |

3/4 |

4 |

4/5 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).