1. Introduction

In addition to the severity and complexity characteristics of stage III periodontitis, patients with Stage IV periodontitis often present with esthetic and functional issues, such as tooth elongation, tilting, flaring, diastema, and missing teeth, warranting interdisciplinary orthodontic treatment and oral rehabilitation [

1]. Obtaining proper orthodontic anchorage is often challenging in these patients owing to partial edentulism and reduced periodontal support [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

Osseointegrated titanium implants are widely used to replace missing teeth in patients with partial edentulism during oral reconstruction [

12]. These prosthetic implants have also been proposed for orthodontic anchorage, particularly in cases in which the periodontally compromised or mutilated dentition lacks sufficient anchorage for effective tooth movement [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. In such scenarios, dental implants may initially serve as orthodontic anchorage, and subsequently function as prosthetic abutments, contributing to long-term stability, function, and comfort [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

Experimental animal studies have shown that dental implants subjected to orthodontic forces maintain their stability and effectively address a wide range of orthodontic and prosthetic challenges [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Clinical use in humans has also revealed that dental implants as orthodontic anchorage can support various types of tooth movement [

3,

4,

5]. Roberts et al. [

18] used a two-stage endosseous implant in the retromolar region of the mandible to provide rigid anchorage, successfully translating two molars 10–12 mm mesially into an atrophic edentulous ridge. In a prospective study by Higuchi and Slack [

19], titanium implants were placed in the posterior mandible of seven patients following the Brånemark protocol. These implants were used to either protract the entire dentition in the maxilla and mandible or retract and correct Class III anterior crossbite malocclusions in patients with missing molars. Except for one implant, all implants were placed in the retromolar areas and were not intended for prosthetic use.

Studies by Odman et al. [

20], Kokich, and others [

3] have demonstrated that dental implants can serve as reliable alternatives to orthodontic anchorage in partially edentulous patients. Despite numerous reviews on the topic [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11], information on patients with Stage IV periodontitis remains limited. In addition, studies directly comparing the marginal bone level (MBL) in dental implants used for orthodontic anchorage versus those used solely for prosthetic purposes are limited [

21,

22,

23,

24]. Research focusing on the long-term outcomes and risk factors of dual-purpose implants is scarce.

This retrospective case-control study, with over 17 years of follow-up, aimed to evaluate the clinical and radiographic outcomes and identify the risk factors associated with the use of dental implants as orthodontic anchorage in patients with Stage IV periodontitis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All medically healthy patients with Stage IV periodontitis who were referred for periodontal, implant, and interdisciplinary therapy to the Department of Dentistry, Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital, between 2007 and 2016, were retrospectively enrolled in this long-term case-control study. Patients who had received at least one implant for orthodontic anchorage and at least one implant solely for prosthetic support were eligible for inclusion.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital (IRB No. 13-IRB 76). The study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and all participants provided written informed consent for both the treatment plan and surgical procedures. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines, as outlined in the Supplementary File.

Exclusion criteria included a history of alcohol or drug abuse, uncontrolled diabetes (glycated hemoglobin [HbA1c] > 8.5%), heavy smoking (> 10 cigarettes per day), or any systemic disease that could compromise periodontal or orthodontic therapy. Treatment planning was patient-centered and based on individual health, function, and esthetic needs. Each patient provided written informed consent for the interdisciplinary treatment plan and associated surgical interventions. Periodontal therapy was performed according to evidence-based guideline on the interdisciplinary treatment of stage IV periodontitis [

1]. Basic periodontal treatment, including patient education, oral hygiene instructions, and scaling and root planing, was performed to control periodontal infection. Periodontitis patients received first complete thorough periodontal treatment to achieve disease stability, defined by low levels of bleeding on probing, shallow probing depths, and absence of suppuration, before proceeding with implant placement [

2,

3,

4,

5].

2.2. Periodontal and Implant Surgical Procedures and Postsurgical Care

All surgeries were performed by one of the authors (SD), a clinician with over 20 years of experience in periodontal and implant surgeries (for detailed information, see Dung [

26]).

Open flap debridement or regenerative periodontal surgeries were conducted to thoroughly debride diseased root surfaces or regenerate lost periodontal tissues. An implant bed was prepared to optimize primary implant stability. Horizontal ridge deficiencies or the lateral wall of the maxillary sinus were augmented using biphasic calcium phosphate bone grafts (MBCP™, Biomatlante, France) and covered with collagen membranes (Neomem®, Citagenix, Laval, QC, Canada or EZ Cure™, Biomatlante, France). The flap was coronally repositioned and secured using resorbable Vicryl sutures (Ethicon J&J, Taipei, Taiwan) to promote primary wound healing.

Postoperatively, the patients were instructed to continue Augmentin 1,000 mg twice daily to prevent infection. In addition, they were advised to use a 0.12% chlorhexidine mouthwash (Beauteeth Co., New Taipei City, Taiwan) twice daily for 2 weeks. Patients were instructed to avoid tooth brushing and chewing in the surgical area for 4 weeks. The sutures were removed 2 weeks postoperatively, and supragingival mechanical plaque control was performed. Follow-up wound care was provided 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks postoperatively. SPC was administered every 3 months after the orthodontic treatment completion.

2.3. Implant Provisional Restoration and Orthodontic Treatment

Implant provisional restorations were fabricated and loaded at the appropriate time after implant placement. Self-ligating orthodontic brackets (Damon Q, Ormco, Orange, CA, USA) were used, and Damon orthodontic arch wires (Cu-Ni-Ti, 0.014” round wire) were inserted. Active orthodontic treatment was initiated immediately after the delivery of the provisional implant restorations, with adjustments performed every 1–2 months. The archwire sequence was: .014 NiTi, .016 NiTi, .014x.025 NiTi, .016x.025 NiTi. The implants used as anchorage were submitted to sliding, compression and traction forces by means of power chain and open coil springs. Dental implants used for orthodontic anchorage were under forces ranging from 100 to 200 g. SPC was provided at each orthodontic visit.

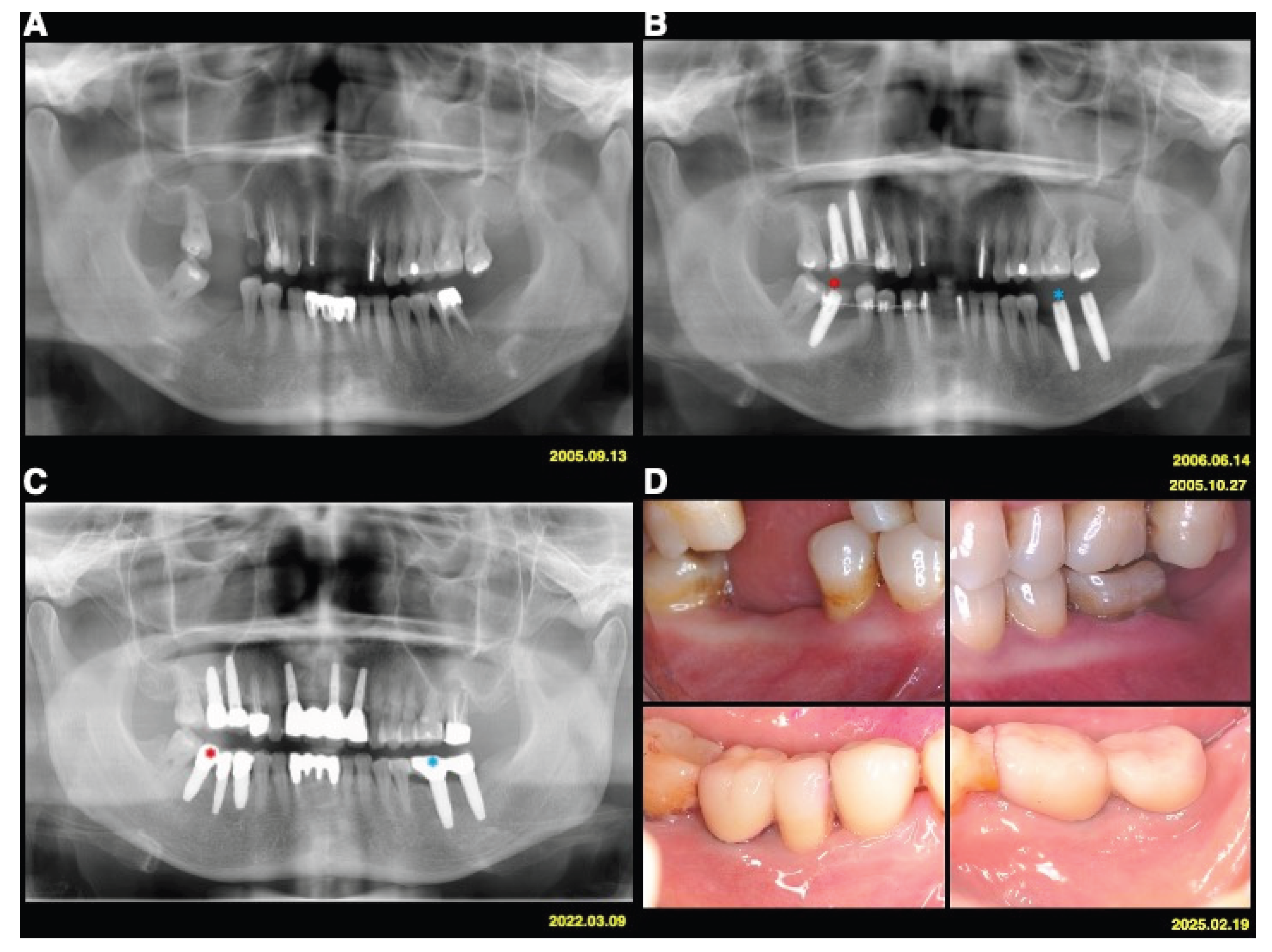

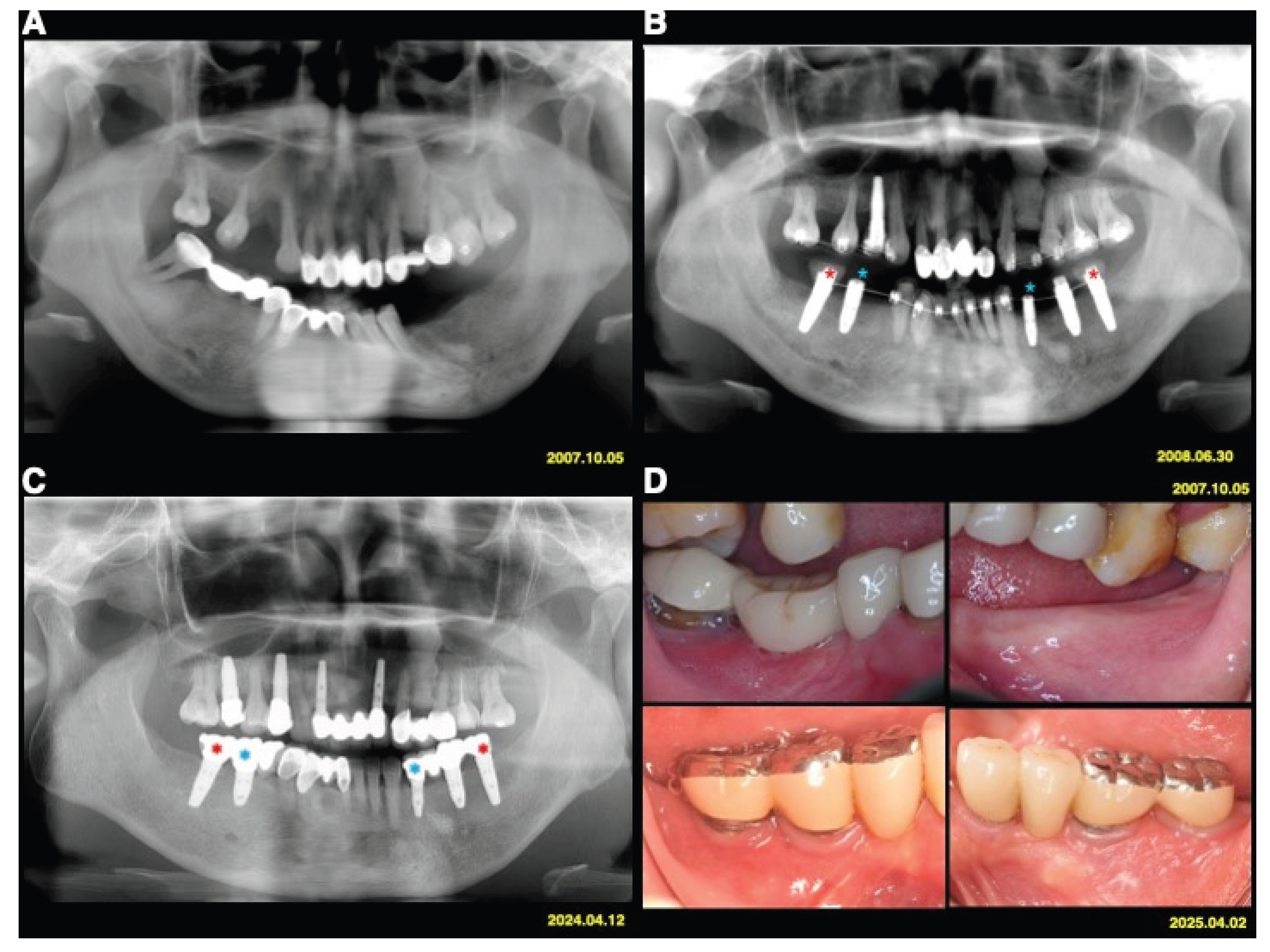

The test implants served as absolute orthodontic anchorages to facilitate molar uprighting, tooth retraction and realignment, or implant site development, whereas implants used exclusively for prosthetic purposes served as controls (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The use of implant anchorage significantly supported orthodontic treatment in patients with periodontally compromised dentition. A key advantage of this combined orthodontic-prosthetic approach was that the implants play a dual role, providing both anchorage and functional rehabilitation.

All the implants remained stable throughout the entire duration of orthodontic treatment. Orthodontic treatment period varied between 7 and 29 months. Upon completion of active orthodontic therapy, the appliances were removed and definitive cement-retained fixed implant prostheses were delivered. All the patients received fixed retainers to prevent relapses. SPC was continued every 3 months to maintain periodontal and peri-implant health.

2.4. Clinical and Radiographic Evaluation

Clinical examinations and standardized periapical and panoramic radiographs were obtained at the initial assessment, during orthodontic therapy, at the time of implant restoration, and at the final follow-up. The clinical parameters evaluated included the plaque score, bleeding on probing, probing depth, marginal tissue recession, and width of the keratinized mucosa (KM). Midfacial marginal tissue recession (MTR) was defined as the distance from the crown margin to the mucosal margin. The number of SPC per year was recorded.

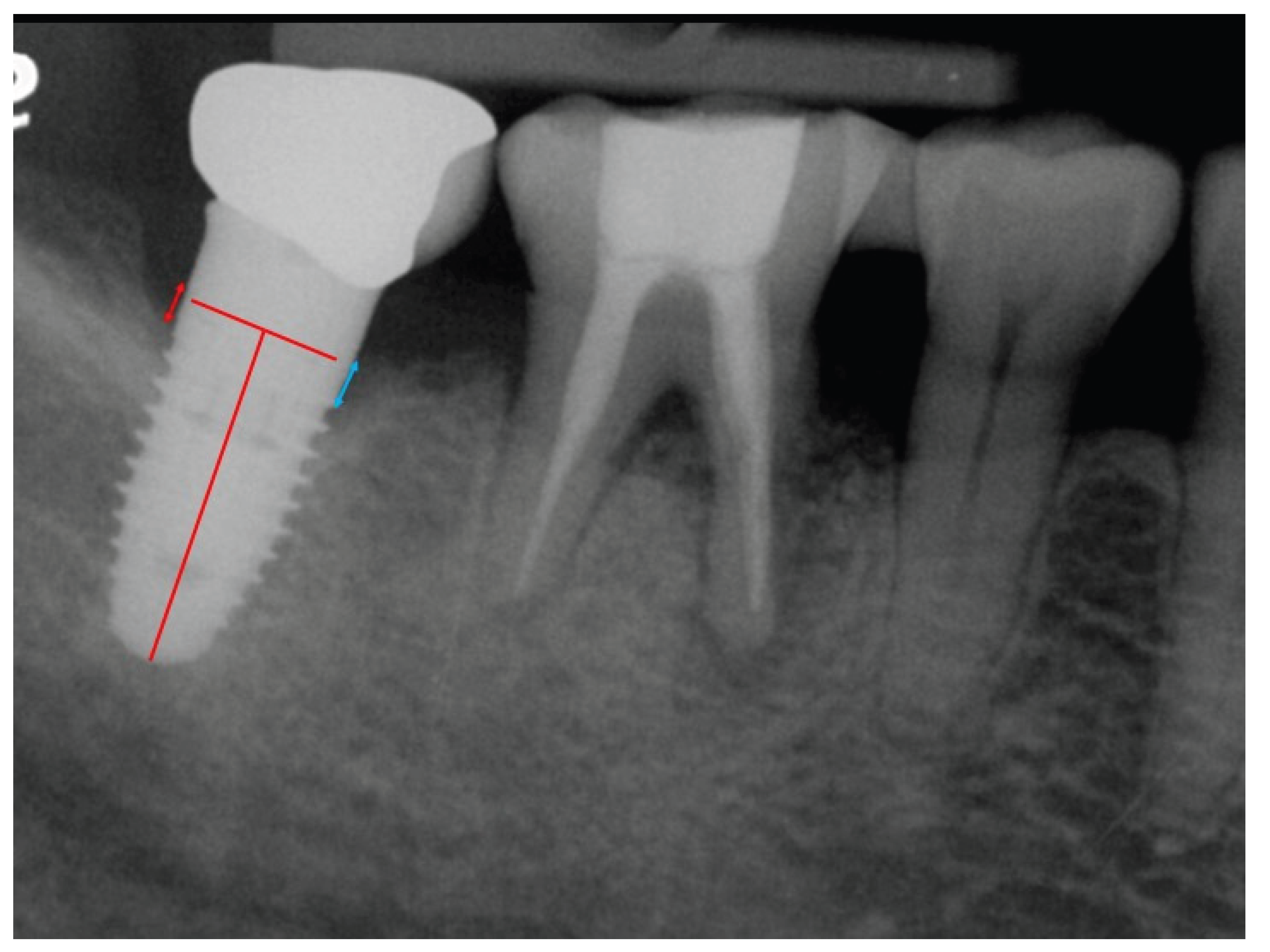

Baseline periapical radiographs were obtained at the initiation of orthodontic therapy with implants as reference for the MBL measurements. Radiographic assessments of the MBLs around the implants were conducted using digital imaging software (Infinitt Radiology PACS, Taipei, Taiwan). The MBL was measured from the crown margin to the alveolar bone crest (

Figure 3). Both the mesial and distal bone levels were measured at the time of crown delivery (points a and b) and at the final follow-up (points c and d). The mean bone level for each implant was calculated as the mean of the mesial and distal measurements. The distortion ratio was used to adjust radiographic assessments for a coefficient derived from the true implant length/radiographic implant length ratio to account for radiographic distortion and magnification. Total bone loss was calculated by subtracting the baseline average bone level (a+b)/2 from the final follow-up average bone level (c+d)/2.

Following implantation and orthodontic therapy, the patients were recalled for clinical and radiographic evaluations at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year, and annually thereafter for up to 17 years. During each follow-up visit, SPC was performed and occlusion was reassessed. Implant survival and success were evaluated according to the established criteria [

27,

28,

29].

2.5. Case Definitions of Peri-Implantitis

Case definitions of peri-implantitis were based on the consensus report of Workgroup 4 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-implant Diseases and Conditions [

30]

. Peri-implantitis was defined as the presence of bleeding on probing and/or suppuration upon gentle probing, increased probing depth compared with previous examinations, and bone loss beyond the expected crestal bone-level changes associated with initial bone remodeling. In this long-term study, peri-implantitis was defined as MBL > 1 mm, accounting for a probing measurement error of approximately 0.8 mm.

2.6. Risk Factors for MBL and Peri-Implantitis

Possible patient- and implant-related risk factors were evaluated, including oral hygiene (OH), compliance with SPC, timing of orthodontic loading, lack of KM (defined as KM < 2 mm), MTR, and duration of follow-up.

Compliance was assessed based on the average number of periodontal maintenance visits per year after surgery. Patients were categorized as highly compliant if they attended more than three visits per year, moderately compliant if they attended two visits per year, and poorly compliant if they attended only 0–1 visits per year. OH at the follow-up visits was evaluated using the O’Leary’s Plaque Score (PS) [

31]. OH status was classified as good (PS < 20%), moderate (20% ≤ PS < 50%), or poor (PS ≥ 50%).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Potential patient- and implant-related risk factors associated with MBL and peri-implantitis in implants used for orthodontic anchorage were analyzed. Pair t test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test were used to analyze the impact of implants as orthodontic anchorage and implant type on changes of MBL. Univariate analyses were performed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables in more than two groups. Multiple regression analysis was used to identify the predictors of MBL among the significant risk factors. All statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.3.3), with a significance level set at 5% (α = 0.05).

3. Results

This study included clinical and radiographic evaluations of 58 implants placed in 29 patients, with a mean age of 49.03 ± 9.30 years. The mean follow-up period was 11.95 ± 3.68 years (range: 5–17 years).

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive characteristics of the patient- and implant-related risk factors. Among the study population, 27.6% demonstrated good OH and approximately 60.3% received SPC at least twice per year. All implants were restored using fixed crown and bridge prostheses. Only five teeth from five patients were lost during the follow-up period. Two teeth were lost due to periodontitis, one due to dental caries, and two due to tooth fractures.

Of the 58 implants, 36 (62.1%) and 22 (37.9%) were two-piece bone-level cylindrical implants (Replace® system) and one-piece implants (Nobel Direct®), respectively. Seventeen implants (58.6%) were subjected to orthodontic loading within 3 months of placement. A total of 17.2% of the implants demonstrated an MBL greater than 1 mm, and 51.7% had a KM width of less than 2 mm. Notably, 81% of the patients had follow-up periods longer than 7 years, and 62.1% of the implants revealed no tissue recession with follow-up exceeding 10 years.

Table 2 presents the relationship between implant anchorage type and changes in MBL. The mean MBL was 0.43 ± 0.95 mm for anchorage implants and 0.28 ± 1.10 mm for non-anchorage implants. Both the t-test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test indicated no statistically significant association between the MBL and orthodontic anchorage or implant type (

p > 0.05).

Univariate analysis of patient- and implant-related risk factors for MBL is shown in

Table 3. Among these factors, low compliance with the SPC was significantly associated with increased MBL (

p = 0.004).

The baseline characteristics stratified by the presence of peri-implantitis are shown in

Table 4. Of all the risk factors, OH and implant type demonstrated a moderate association with peri-implantitis, with borderline statistical significance (

p = 0.05). Other variables, including compliance, timing of implant loading, KG < 2 mm, tissue recession, and duration of follow-up, were not significantly associated with peri-implantitis.

Table 5 lists the variables affecting peri-implantitis. In a univariate logistic regression analysis using the generalized estimating equations method, implants with KM < 2 mm were significantly associated with a higher risk of peri-implantitis (odds ratio = 6.92;

p = 0.015). Poor OH (

p = 0.05) had a moderate risk of peri-implantitis (odds ratio = 5.98;

p = 0.05).

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first long-term case-control study to demonstrate no significant difference in the MBL between dental implants used for orthodontic anchorage and those used solely for prosthetic purposes.

Specific studies directly comparing the MBL and survival rates of dental implants used for orthodontic anchorage versus those used solely for prosthetic support are limited [

22,

23,

24]. In a 1- to 6-year case series involving 43 roughened-surface implants in 11 patients, Kato and Kato [

22] also found that all implants used for orthodontic anchorage maintained osseointegration and continued to function effectively. There were no significant differences in the MBL or implant survival between implants used as orthodontic anchors and those used exclusively for prosthetics. Marta and Carlos [

23] evaluated 93 implants used for orthodontic anchorage under forces ranging from 100 to 200 g in 38 partially edentulous patients. The results demonstrated that the implants could withstand orthodontic forces and maintain osseointegration without significant changes in the bone levels.

Marins et al. compared the MBL of osseointegrated implants subjected to orthodontic forces with that of implants used solely for prosthetic loading after 3 years of functional use [

24]. Twenty-six implants were used for orthodontic anchorage, and 24 served as controls for prosthetic support only. These findings indicate that using implants for intraoral orthodontic anchorage does not compromise peri-implant tissue health or implant longevity. However, factors such as force magnitude and direction, implant location, and patient-specific characteristics (e.g., bone density and OH) may influence the outcomes. Additional high-quality, randomized, long-term studies are warranted to confirm these findings.

Several studies have suggested that in motivated and compliant patients with stably treated stage IV periodontitis, orthodontic tooth movement demonstrated no significant impact on the periodontal outcomes [

32,

33,

34]. However, there is limited evidence regarding the treatment outcomes and risk factors of implants for orthodontic anchorage in patients with stage IV periodontitis. Univariate analysis of all patient- and implant-related risk factors in this study revealed that low compliance was the only factor significantly associated with a greater MBL (

p = 0.004).

This long-term case-control study may be the first to evaluate the risk factors for peri-implantitis in prosthetic implants used for orthodontic anchorage. Among the identified risk factors, the use of one-piece implants and poor OH were moderately associated with the development of peri-implantitis. Previous studies have also shown that one-piece implants (e.g., NobelDirect), while eliminating the microgap, exhibit greater early MBL [

35,

36]. Immediate loading, the use of the implant for multiunit construction, flapless surgery, and other factors may also contribute to the observed bone loss in NobelDirect implants. The reason why one-piece implants used for orthodontic anchorage demonstrated a higher risk of peri-implantitis in this study remains unclear, warranting further investigation.

Berglundh et al. [

37] reported that patients with a history of periodontitis, particularly those with poor plaque control and irregular maintenance during follow-up, exhibited an increased risk of developing peri-implantitis. In the context of orthodontic anchorage, poor OH may significantly increase the risk of peri-implantitis owing to the combined effects of bacterial biofilm accumulation, mechanical loading, and soft tissue stress, ultimately leading to accelerated MBL. Poor OH for implants used as orthodontic anchorage may accelerate tissue breakdown, especially in patients with a thin mucosal biotype, KM < 2 mm, and a history of periodontal disease, and deserves further evaluation.

The present study is the first to show that orthodontic anchorage implants with KM < 2 mm exhibited a significantly higher risk of peri-implantitis. The need for KM around implants for maintaining tissue health and stability is debatable [

38,

39,

40,

41]. The impact of KM < 2 mm on implants used for orthodontic anchorage is unclear and may be associated with peri-implantitis owing to higher plaque accumulation, reduced patient comfort and hygiene, increased MBL, and soft tissue recession.

Several studies have evaluated the impact of loading forces on the performance of implant anchorage [

42,

43,

44,

45]. However, the optimal time interval and loading forces for dental implant stability sufficient for orthodontic movement remain debatable. The timing of implant loading as orthodontic anchorage was not significantly associated with peri-implantitis. The effect of the loading timing on the performance of implant anchorages has been evaluated in several studies [

46,

47,

48]. Immediate or early loading protocols, in which orthodontic forces are applied shortly after implant placement, can be effective if carefully managed. This approach reduces the treatment time and may enhance patient satisfaction. Delayed loading (>3 months) is considered safer for compromised sites. Careful planning, appropriate loading time and forces, highly compliant, closely monitoring in a specialist setting, and frequent SPC are warranted to avoid compromising the osseointegration.

Although this retrospective case-control study has some strengths, it also has certain limitations, such as recall and selection bias, incomplete data, small sample sizes, and uncontrolled confounding factors. In this study, the small cohort size, combined with subgroup and risk modeling, undermines the statistical power and broad applicability. Further long-term randomized studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to validate these findings. Another limitation is sparse data bias in certain covariate strata. When events or covariate patterns are rare, the penalized approach may produce unstable estimates with wide confidence intervals, particularly in subgroup analyses, potentially masking clinically meaningful associations [

49].

5. Conclusions

The findings of this long-term case-control study suggest that neither orthodontic anchorage nor implant type are significantly associated with MBL. However, poor patient compliance is a significant predictor of increased MBL in implants used for orthodontic anchorage. Poor OH and use of one-piece implants were moderately associated with a higher risk of peri-implantitis. Notably, implants used for orthodontic anchorage with poor OH and KM < 2 mm demonstrated a significantly increased risk of peri-implantitis. Within the limitations of this study, dental implants were able to withstand both orthodontic and occlusal forces while maintaining long-term osseointegration in patients with Stage IV periodontitis.

Author Contributions

S-Z Dung: Data collection; formal analysis; visualization; investigation; writing–original draft; writing–review and editing. I-S Tzeng: Data analysis; supervision; review and editing. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript, and they have agreed to take responsibility for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This study was supported by grant from Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation. (TCRD-TPE-114-54).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975 and the 2013 revised version. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital (Protocol No. 13-IRB076).

Informed Consent Statement

The patients gave consent to publish their radiographic images.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Drs. Kim-Chey Luo, Nie-Shiuh Chang, and Jing-Jong Lin for their mentorship and critiques in interdisciplinary treatment planning.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests related to this work.

Abbreviations

| BOP |

Bleeding on probing |

| CBCT |

Cone beam computed tomography |

| GEE |

Generalized estimating equation |

| KM |

Keratinized mucosa |

| MBCP |

Macroporous biphasic calcium phosphate |

| MBL |

Marginal bone level |

| MTR |

Midfacial mucosal tissue recession |

| OH |

Oral Hygiene |

| PS |

Plaque score |

| SPC |

Supportive periodontal and peri-implant care |

References

- Herrera D, Sanz M, Kebschull M, et al. EFP Workshop Participants and Methodological Consultant. Treatment of stage IV periodontitis: The EFP S3 level clinical practice guideline. J Clin Periodontol. 2022;49 Suppl 24:4-71.

- Smalley WM. Implants for tooth movement: Determining implant location and orientation. J Esthet Dent. 1995;7(2):62-72.

- Kokich VG. Managing complex orthodontic problems: The use of implants for anchorage. Semin Orthod. 1996;2:153-60.

- Kokich, V. G. (2000) Comprehensive management of implant anchorage in the multidisciplinary patient. In: K. W. Higushi (Ed) Orthodontic applications of osseointegrated implants (pp.21-32). Quintessence Publications.

- Huang LH, Shotwell JL, Wang HL. Dental implants for orthodontic anchorage. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;127(6):713-22.

- Goodacre CJ, Brown DT, Roberts WE, Jeiroudi MT. Prosthodontic considerations when using implants for orthodontic anchorage. J Prosthet Dent. 1997;77(2):162-70.

- Labanauskaite B, Jankauskas G, Vasiliauskas A, Haffar N. Implants for orthodontic anchorage. Meta-analysis. Stomatologija. 2005;7(4):128-32.

- Lee TC, Leung MT, Wong RW, Rabie AB. Versatility of skeletal anchorage in orthodontics. World J Orthod. 2008;9(3):221-32.

- Zheng X, Sun Y, Zhang Y, Cai T, Sun F, Lin J. Implants for Orthodontic Anchorage: An overview. Medicine. (Baltimore) 2018;97(13):e0232.

- Blanco-Jauset P, Polis-Yanes C, Oliver-Puigdomenech C, Domingo-Mesegué M, López-López J, Marí-Roig A. Osseointegrated dental implants as an anchorage method. A systematic review. Scientific Archives Dental Sci. 2020:3:1-9.

- Pinho T, Neves M, Alves C. Multidisciplinary management including periodontics, orthodontics, implants, and prosthetics for an adult. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2012;142(2):235-45.

- Lang NP. Oral Implants: The Paradigm shift in restorative dentistry. J Dent Res. 2019;98(12):1287-93.

- Gray JB, Steen ME, King GJ, Clark AE. Studies on the efficacy of implants as orthodontic anchorage. Am J Orthod. 1983;83(4):311-7.

- Roberts WE, Smith RK, Zilberman Y, Mozsary PG, Smith RS. Osseous adaptation to continuous loading of rigid endosseous implants. Am J Orthod. 1984;86(2):95-111.

- Turley PK, Kean C, Schur J, Stefanac J, Gray J, Hennes J, et al. Orthodontic force application to titanium endosseous implants. Angle Orthod. 1988;58(2):151-62.

- Linder-Aronson S, Nordenram A, Anneroth G. Titanium implant anchorage in orthodontic treatment an experimental investigation in monkeys. Eur J Orthod. 1990;12(4):414-9.

- Wehrbein H, Diedrich P. Endosseous titanium implants during and after orthodontic load- An experimental study in the dog. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1993;4(2):76-82.

- Roberts WE, Marshall KJ, Mozsary PG. Rigid endosseous implant utilized as anchorage to protract molars and close an atrophic extraction site. Angle Orthod. 1990;60(2):135-52.

- Higuchi KW, Slack JM. The use of titanium fixtures for intraoral anchorage to facilitate orthodontic tooth movement. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1991;6(3):338-44.

- Odman J, Lekholm U, Jemt T, Thilander B. Osseointegrated implants as orthodontic anchorage in the treatment of partially edentulous adult patients. Eur J Orthod. 1994;16(3):187-201.

- Blanco Carrión J, Ramos Barbosa I, Pérez López J. Osseointegrated implants as orthodontic anchorage and restorative abutments in the treatment of partially edentulous adult patients. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2009;29(3):333-40.

- Kato S, Kato M. Moderately roughened- and roughened-surface implants used as rigid orthodontic anchorage: A case series. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2006;8(2):87-94.

- de Cravero Marta R, Carlos IJ. Assessing double Acid-etched implants submitted to orthodontic forces and used as prosthetic anchorages in partially edentulous patients. Open Dent J. 2008;2:30-7.

- Marins BR, Pramiu SE, Busato MCA, Marchi LC, Togashi AY. Peri-implant evaluation of osseointegrated implants subjected to orthodontic forces: Results after three years of functional loading. Dental Press J Orthod. 2016;21(2):73-80.

- Wang HL, Avila-Ortiz G, Monje A, Kumar P, Calatrava J, Aghaloo T, et al. AO/AAP Consensus Participants; Rosen PS. AO/AAP consensus on prevention and management of peri-implant diseases and conditions: Summary report. J Periodontol. 2025;96(6):519-41.

- Dung S-Z. Long-term outcome of dental implants used as orthodontic anchorage in Stage IV periodontitis patients: Case series. J Periodontics Implant Dent. 2025;8(1):25-36.

- Albrektsson T, Zarb G, Worthington P, Eriksson AR. The long-term efficacy of currently used dental implants: a review and proposed criteria of success. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1986;1:11–25.

- Misch CE, Perel ML, Wang HL, et al. Implant success, survival, and failure: The International Congress of Oral Implantologists (ICOI) Pisa Consensus Conference. Implant Dent 2008;17:5-15.

- Herrera D, Berglundh T, Schwarz F, Chapple I, Jepsen S, Sculean A, et al. EFP workshop participants and methodological consultant. Prevention and treatment of peri-implant diseases- The EFP S3 level clinical practice guideline. J Clin Periodontol. 2023;50(Suppl 26):4-76.

- Berglundh T, Armitage G, Araujo MG, et al. Peri-implant diseases and conditions: consensus report of workgroup 4 of the 2017 World workshop on the classification of periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 20):S31–S38.

- O’Leary TJ, Drake RB, Naylor JE. The plaque control record. J Periodontol. 1972;43(1):38.

- Tietmann C, Bröseler F, Axelrad T, Jepsen K, Jepsen S. Regenerative periodontal surgery and orthodontic tooth movement in stage IV periodontitis: A retrospective practice-based cohort study. J Clin Periodontol. 2021;48(5):668-678.

- Garbo D, Aimetti M, Bongiovanni L, Vidotto C, Mariani GM, Baima G, et al. Periodontal and Orthodontic Synergy in the Management of Stage IV Periodontitis: Challenges, Indications and Limits. Life. (Basel) 2022;12(12):2131.

- Martin C, Celis B, Ambrosio N, Bollain J, Antonoglou GN, Figuero E. Effect of orthodontic therapy in periodontitis and non-periodontitis patients: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2022;49(Suppl 24):72-101.

- Sennerby L, Rocci A, Becker W, Jonsson L, Johansson LA, Albrektsson T. Short-term clinical results of Nobel Direct implants: A retrospective multicentre analysis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2008;19:219-26.

- Van de Velde T, Thevissen E, Persson GR, Johansson C, De Bruyn H. Two-year outcome with Nobel Direct implants: A retrospective radiographic and microbiologic study in 10 patients. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2009;11:183-93.

- Berglundh T, Mombelli A, Schwarz F, Derks J. Etiology, pathogenesis and treatment of peri-implantitis: A European perspective. Periodontol 2000. 2024 Feb 2. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Lin GH, Chan HL, Wang HL. The significance of keratinized mucosa on implant health: A systematic review. J Periodontol. 2013;84(12):1755-67.

- Wennström JL, Derks J. Is there a need for keratinized mucosa around implants to maintain health and tissue stability? Clin Oral Implants Res. 2012;23(Suppl 6):136-46.

- Ramanauskaite A, Schwarz F, Sader R. Influence of width of keratinized tissue on the prevalence of peri-implant diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2022;33(Suppl 23):8-31.

- Thoma DS, Naenni N, Figuero E, Hämmerle CHF, Schwarz F, Jung RE, Sanz-Sánchez I. Effects of soft tissue augmentation procedures on peri-implant health or disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2018;29 (Suppl 15):32-49.

- Chen J, Chen K, Garetto LP, Roberts WE. Mechanical response to functional and therapeutic loading of a retromolar endosseous implant used for orthodontic anchorage to mesially translate mandibular molars. Implant Dent. 1995;4(4):246-58.

- Akin-Nergiz N, Nergiz I, Schulz A, Arpak N, Niedermeier W. Reactions of peri-implant tissues to continuous loading of osseointegrated implants. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998;114(3):292-8.

- Yavuz U, Kirtiloglu T, Acikgoz G, Turk T, Trisi P. Bone response to early orthodontic loading of endosseous implants. J Oral Implantol. 2011;37(Spec):87-95.

- Hsieh YD, Su CM, Yang YH, Fu E, Chen HL, Kung S. Evaluation on the movement of endosseous titanium implants under continuous orthodontic forces: An experimental study in the dog. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2008;19(6):618-23.

- Trisi P, Rebaudi A. Progressive bone adaptation of titanium implants during and after orthodontic load in humans. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2002;22(1):31-43.

- Majzoub Z, Finotti M, Miotti F, Giardino R, Aldini NN, Cordioli G. Bone response to orthodontic loading of endosseous implants in the rabbit calvaria: Early continuous distalizing forces. Eur J Orthod. 1999;21(3):223-30.

- Palagi LM, Sabrosa CE, Gava EC, Baccetti T, Miguel JA. Long-term follow-up of dental single implants under immediate orthodontic load. Angle Orthod. 2010;80(5):807-11.

- Tzeng IS. To handle the inflation of odds ratios in a retrospective study with a profile penalized log-likelihood approach. J Clin Lab Anal. 2021;35(7):e23849.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).