3.1. Plastic Nation

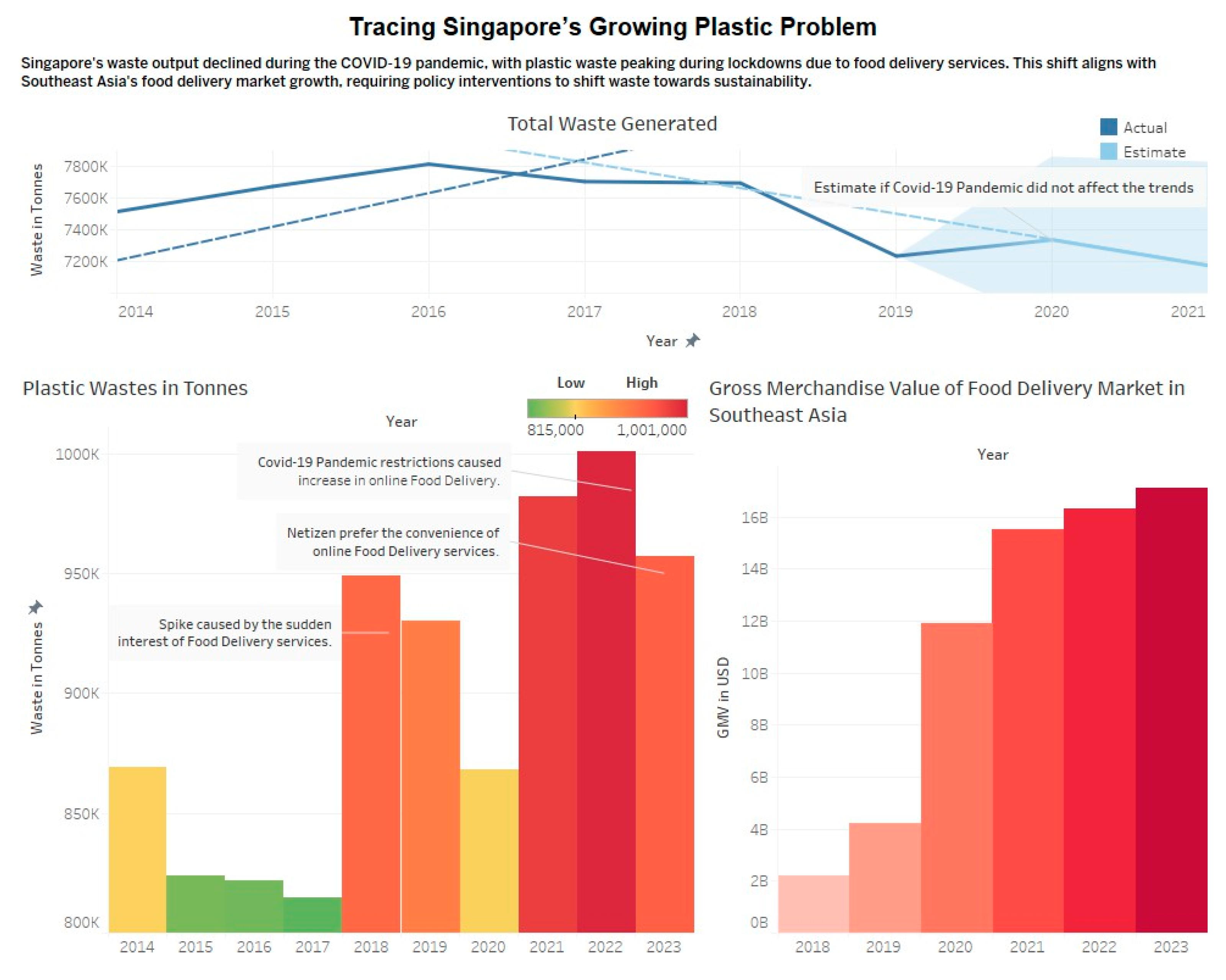

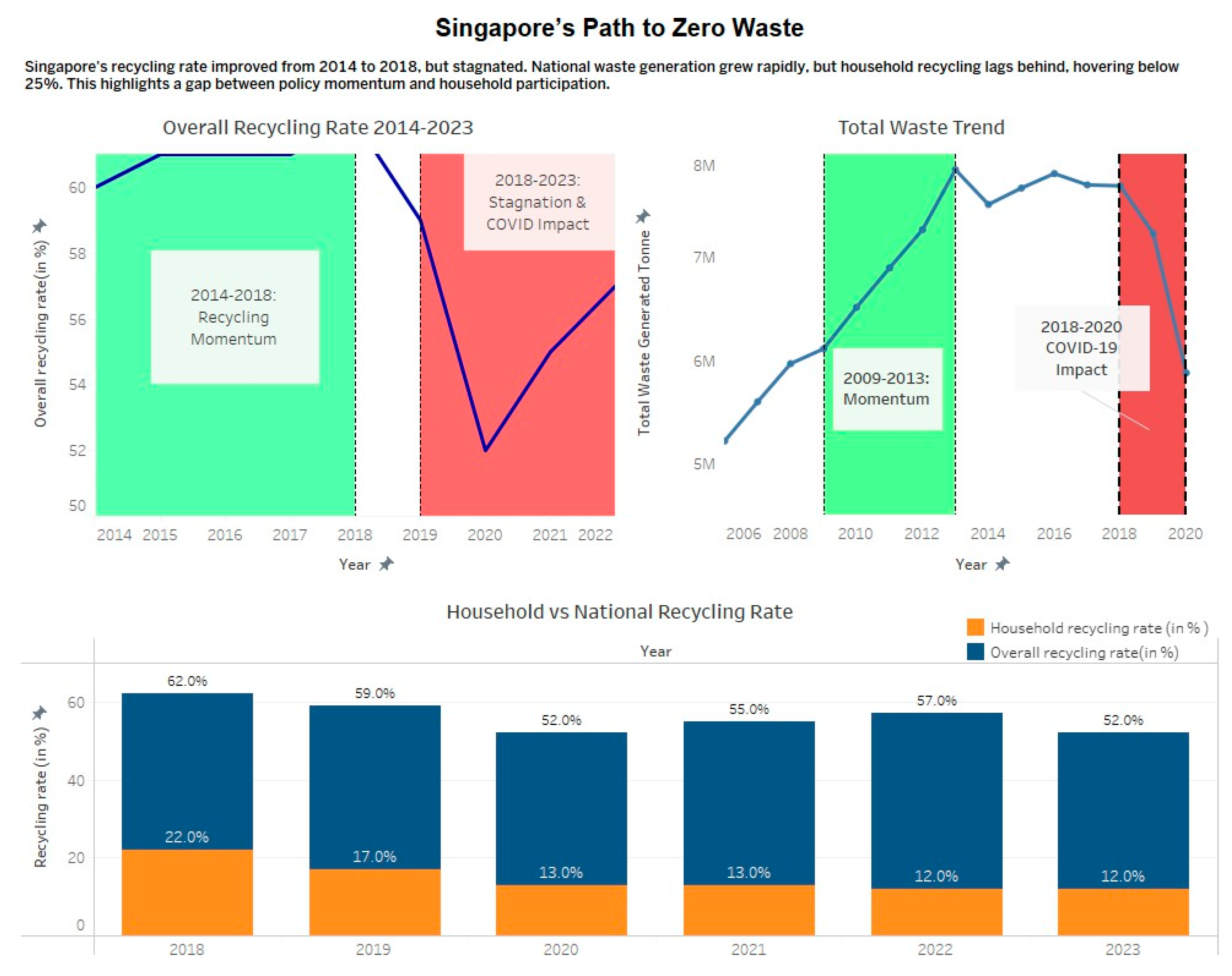

Singapore’s waste output declined during the COVID-19 pandemic, with plastic waste peaking during lockdowns due to food delivery services. This shift aligns with Southeast Asia’s food delivery market growth, requiring policy interventions to shift waste towards sustainability.

Figure 6.

Plastic Nation Story Point.

Figure 6.

Plastic Nation Story Point.

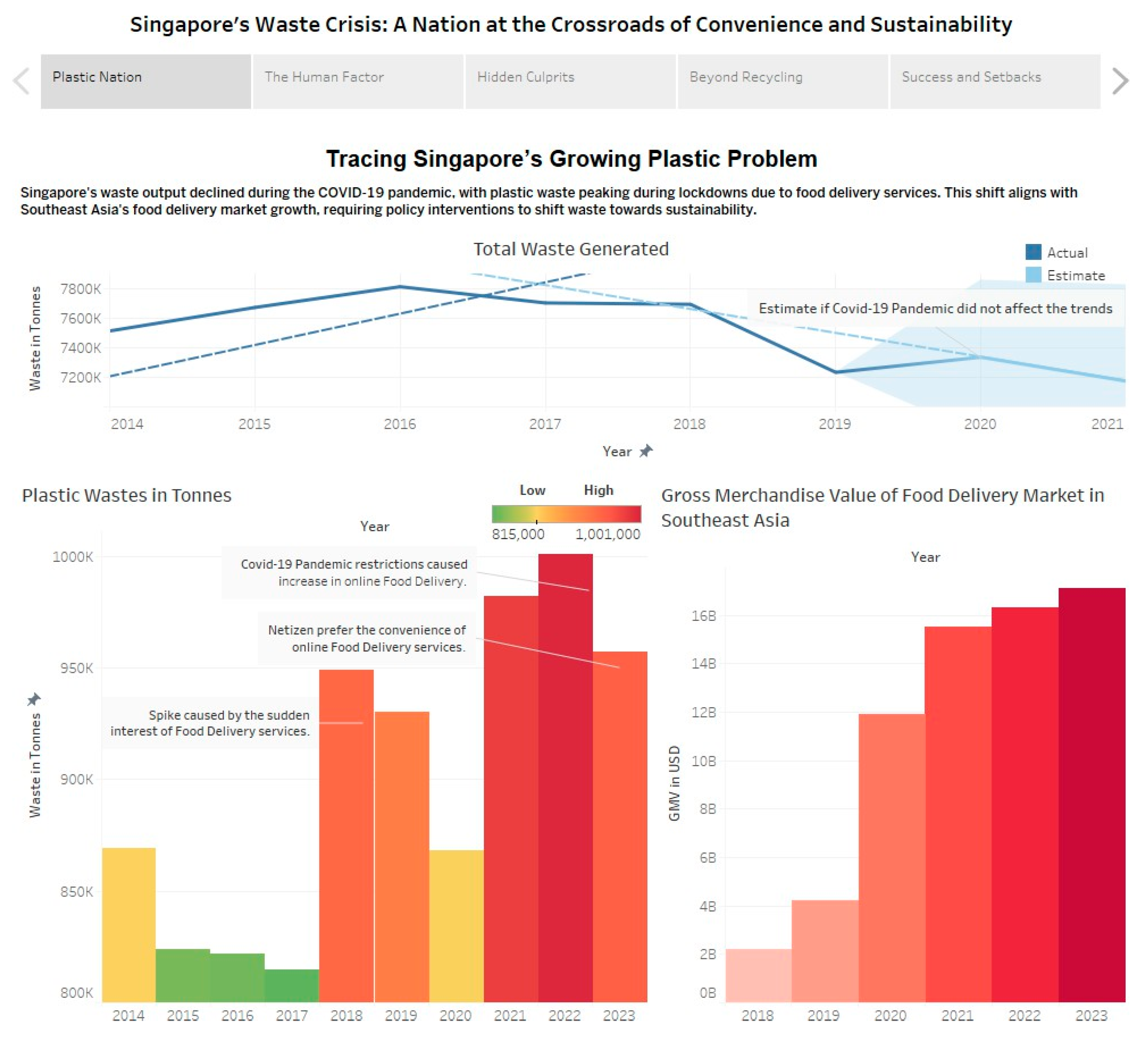

3.1.1. Pandemic Disruptions Alter Waste Trajectories

The top line graph illustrates Singapore's total garbage production from 2014 to 2021, comparing actual figures with projected trends with the assumption that the COVID-19 outbreak did not happen. The estimated data indicates that total garbage showed a consistent increase from 2014 to 2018. Beginning in 2019, real trash values significantly diverge from estimates, experiencing a considerable decline in 2020 and 2021.

Figure 7.

Total Waste Generated.

Figure 7.

Total Waste Generated.

This variation can be directly associated with the global pandemic, which modified economic activities and reduced specific kinds of industrial and commercial waste. However, the significant decline in total trash hides a critical trend which is the simultaneous increase in plastic waste associated with changes in consumer behaviour, especially within the food service industry.

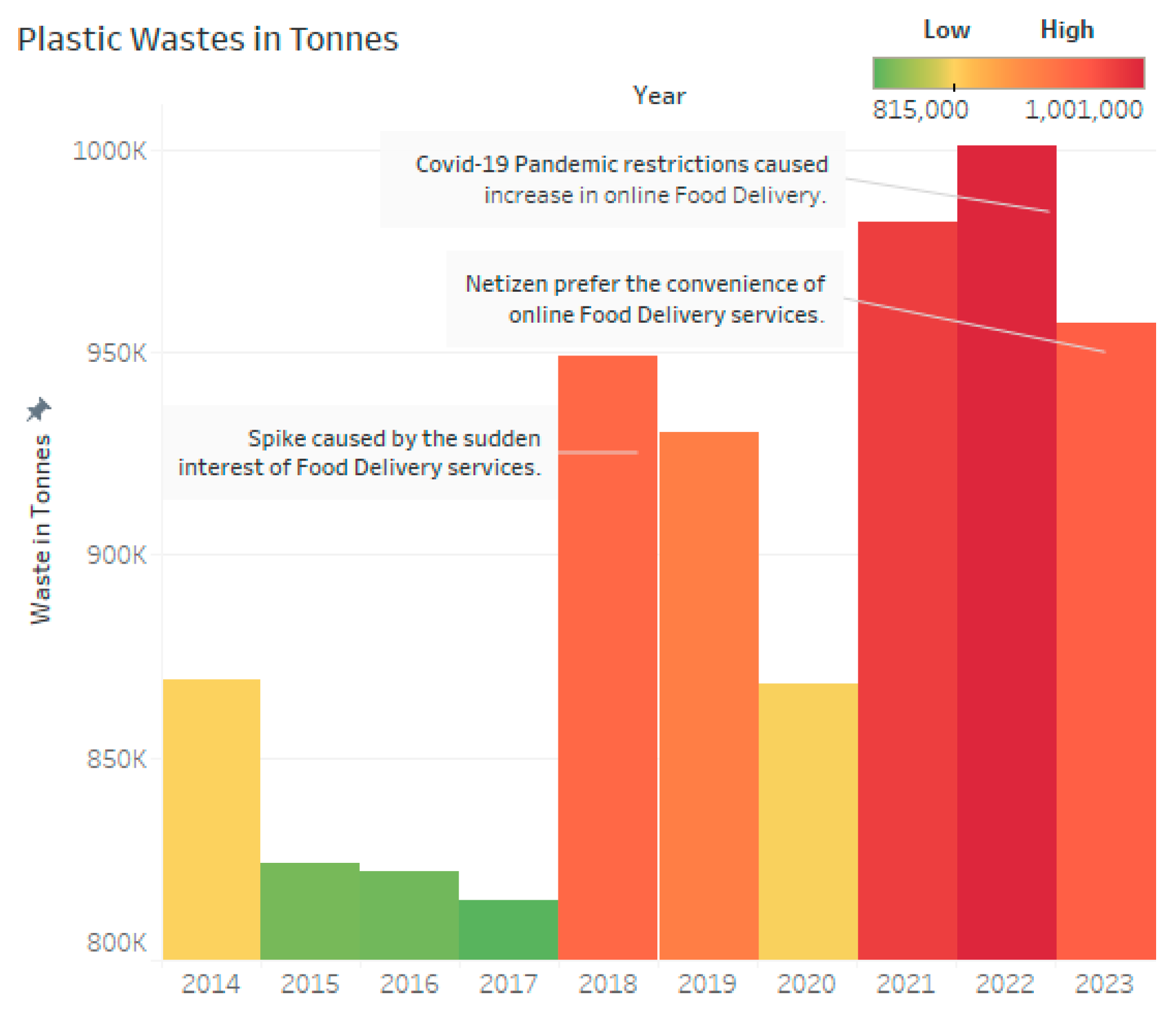

3.1.2. Plastic Waste Peaks with Food Delivery Boom

The second picture, a bar graph entitled Singapore Plastic Waste in Tonnes, highlights the divergence of plastic-specific waste from the overall drop. Although overall trash decreased, plastic waste surged to abnormal levels in 2021 and 2022 which corresponds with pandemic-induced lockdowns and a significant increase in online food delivery services.

Figure 8.

Plastic Wastes in Tonnes.

Figure 8.

Plastic Wastes in Tonnes.

Plastic garbage increased from under 950,000 tons in 2018 to over 1,000,000 tonnes in 2022, indicating a significant rise. In spite of the removal of restrictions in later years, plastic trash persisted at high levels, demonstrating a behavioural change among consumers who continue to prefer meal delivery services despite the reintroduction of dine-in alternatives.

This tendency indicates a prolonged alteration in consumer behaviours, extending the environmental impact of the pandemic beyond its economic and health-related consequences. The graph suggests prospective reductions in 2023, likely attributable to plastic-reduction initiatives. However, the levels remain above pre-2019 baselines, indicating ongoing pressure on waste systems.

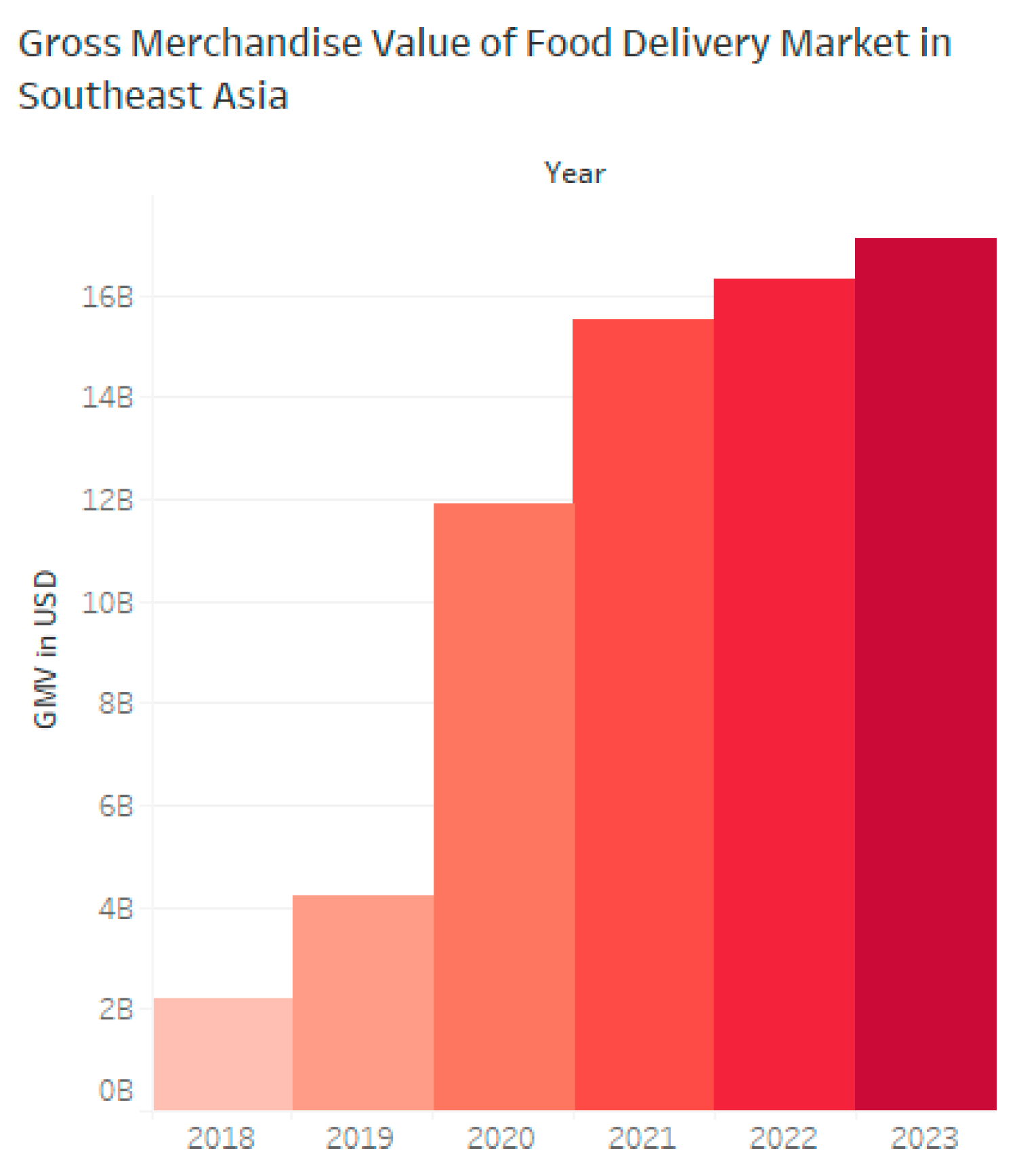

3.1.3. Food Delivery Market Fuels Environmental Strain

The final chart shows the Gross Merchandise Value (GMV) of the Food Delivery Market in Southeast Asia and it offers critical context. Between 2018 and 2023, the gross merchandise volume of the food delivery business doubled, indicating persistent regional demand. The value increased from under USD 4 billion in 2018 to more than USD 16 billion in 2023, closely correlating with the timeline of Singapore's plastic waste growth.

Figure 9.

Gross Merchandise Value of Food Delivery Market in Southeast Asia.

Figure 9.

Gross Merchandise Value of Food Delivery Market in Southeast Asia.

This indicates that Singapore's plastic trash problem is not unique but rather part of a wider trend throughout Southeast Asia. As regional economies embraced digital consumption, waste systems faced growing pressure from single-use packaging associated with meals, groceries, and beverages.

3.1.4. Redefining Responsibility in Post-Pandemic Waste Policy

The study shows a significant discrepancy between behavioural patterns and waste management policies. While the overall waste volume decreased due to reduced economic activity, the rise in plastic waste disproves the assumptions of environmental issues that have lessened during the pandemic. Environmental pressures eased during the pandemic. New consumption patterns, especially food delivery, have generated substantial volumes of waste that are difficult to recycle.

Singapore must expand its waste management policies to address this issue. Plastic consumption regulations, which are focused on restricting conventional packaging and straws, should be broadened to cover takeaway and delivery services. Additionally, public campaigns must target convenience-driven habits and encourage consumers to acknowledge the hidden waste expenses associated with seemingly harmless digital transactions.

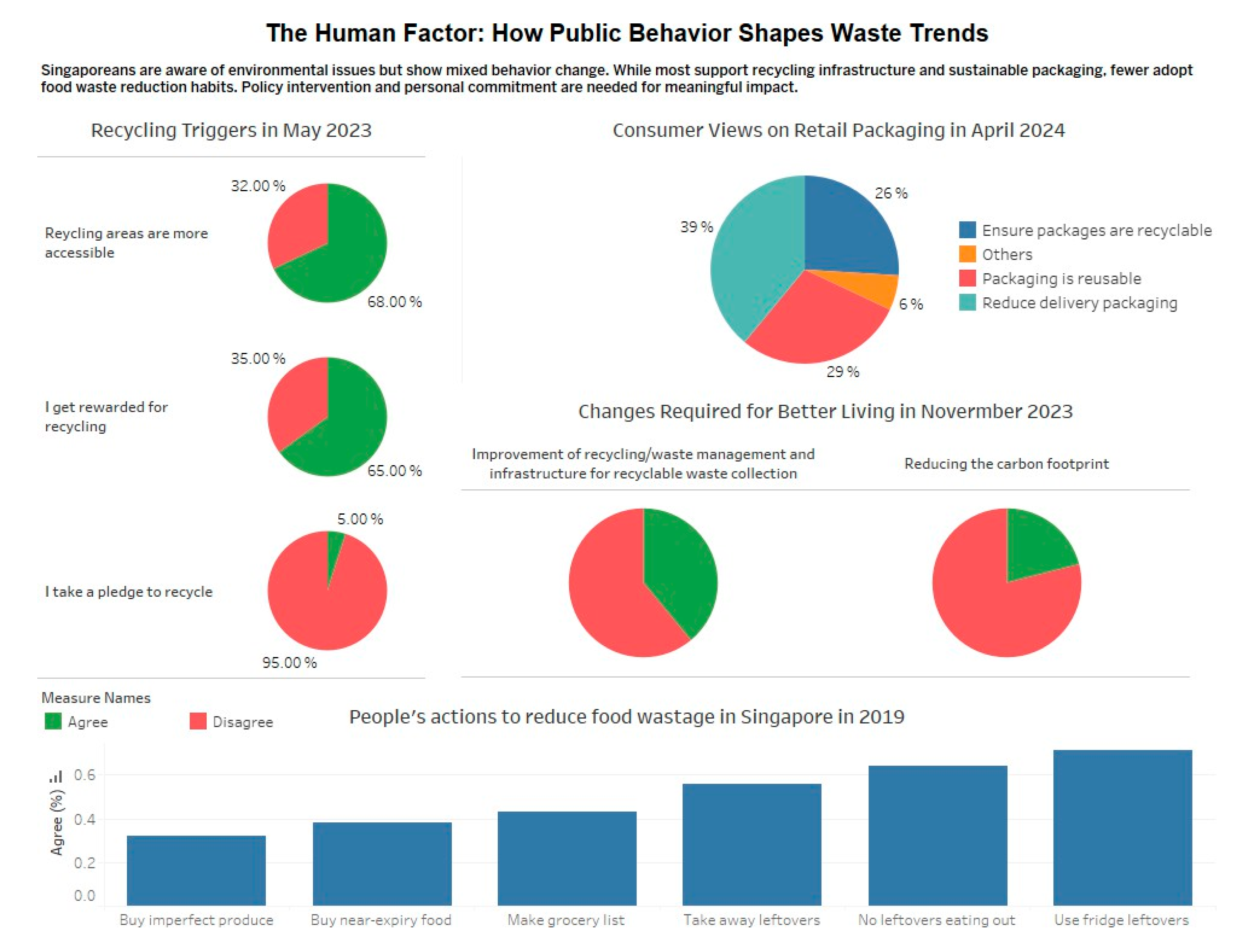

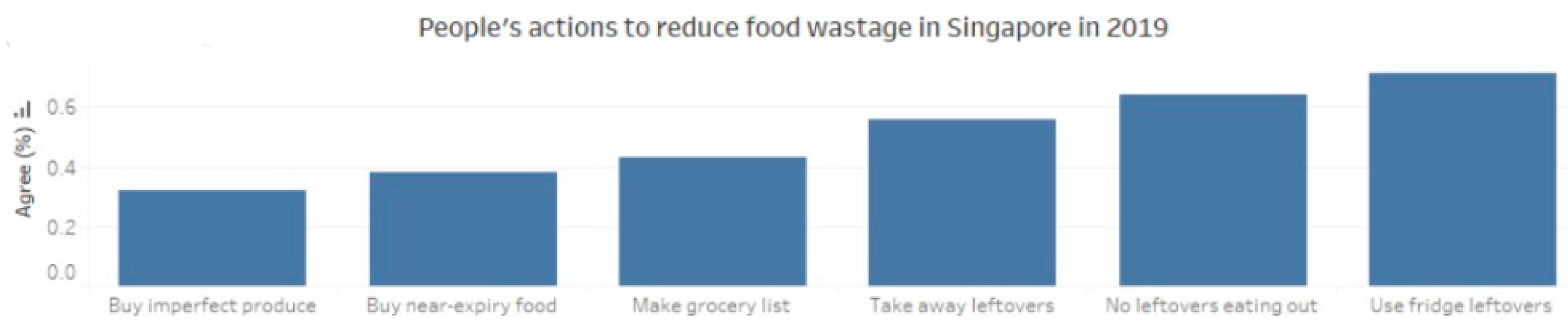

3.2. The Human Factor

The waste landscape in Singapore is shaped by individual choices and daily habits far more than is acknowledged. While infrastructure and industrial contributions remain crucial, this dashboard underscores how public behaviour through recycling practices, packaging preferences, and approaches to food waste plays a pivotal role in driving or mitigating waste trends. Despite the widespread environmental awareness, discrepancies between intention and actual practice highlight an urgent necessity to better align personal motivations with sustainable outcomes. Addressing Singapore’s waste crisis thus requires not only structural solutions but also a reexamination of how everyday behaviours collectively influence the nation’s waste burden.

Figure 10.

The Human Factor Story Point.

Figure 10.

The Human Factor Story Point.

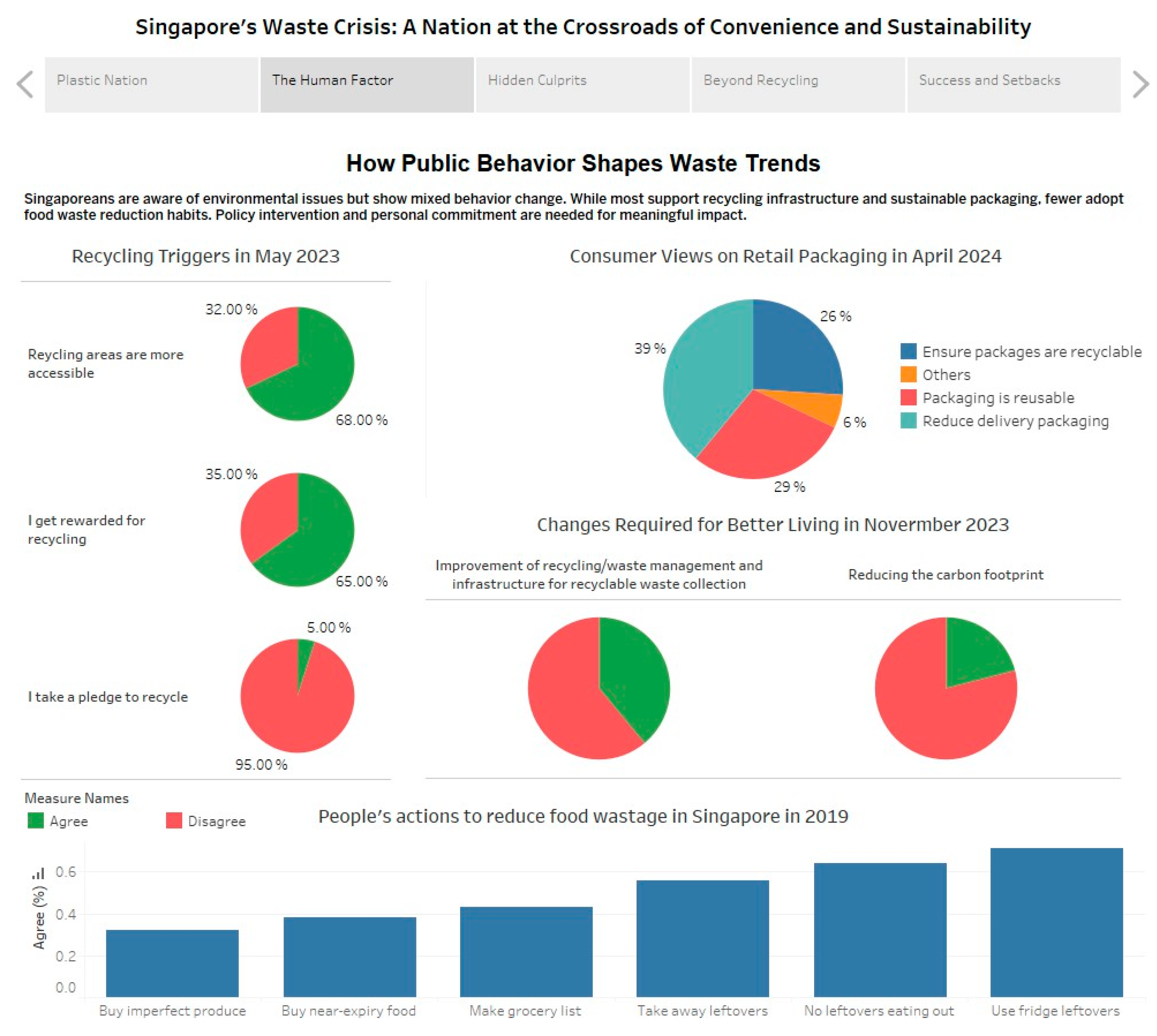

3.2.1. Motivation over Moral Obligation: Recycling Behaviour

The first set of visuals which was extracted from the survey conducted in 2023 demonstrates that Singaporeans largely recycle when it is convenient or personally rewarding. A significant majority highlight that more accessible recycling areas and tangible incentives would motivate the individuals to recycle more regularly. On the other hand, a minimal number of individuals express willingness to make a pledge purely out of environmental responsibility. This indicates that a behavioural ecosystem in which logistical convenience and individual benefit outweigh fundamental environmental responsibility. (Milieu Insight, 2023)

Figure 11.

Recycling Triggers in May 2023.

Figure 11.

Recycling Triggers in May 2023.

Such trends suggest that while people intellectually support recycling, habitual practices hinge on external factors such as accessible bins, financial incentives, or institutional nudges rather than a profound commitment to sustainability. This behavioural insight is essential for shaping future recycling campaigns and infrastructure planning.

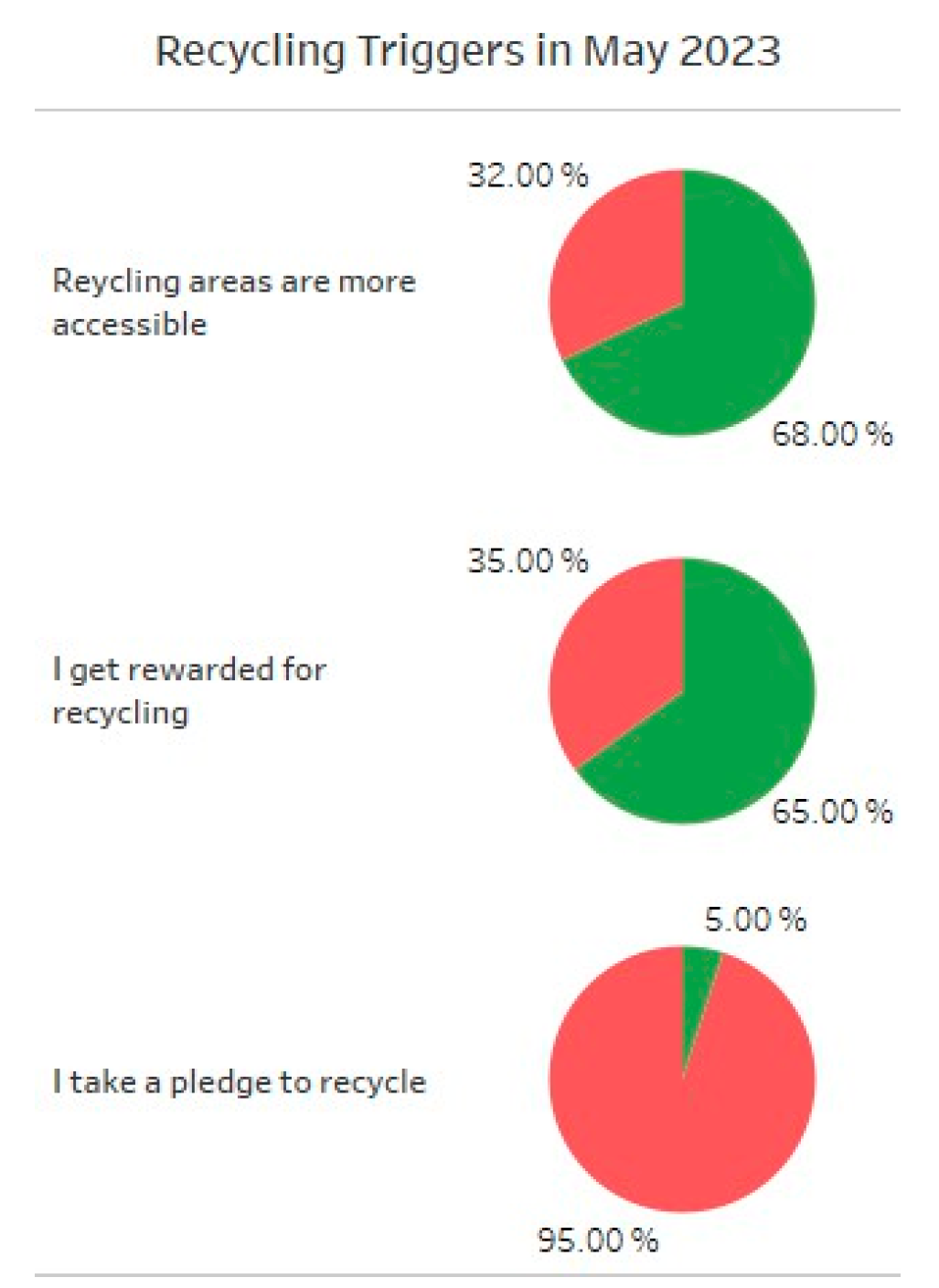

3.2.2. Packaging Preferences Signal Evolving Expectations

The dashboard also explores consumer perceptions toward retail packaging. While there is a distinct preference for environmentally responsible options, the data reveals important nuances that 39% of consumers favour reducing delivery packaging altogether, 29% prefer packaging that is reusable, and 26% look specifically for recyclable packaging.

Figure 12.

Consumer Views on Retail Packaging in April 2024.

Figure 12.

Consumer Views on Retail Packaging in April 2024.

This shows that although a sizeable proportion of shoppers value packaging sustainability, these views represent an evolving expectation rather than a universally held demand. A substantial number of customers persist in prioritising alternative factors, underscoring the ongoing evolution of consumption standards.(Amazon & OnePoll, 2024) These patterns indicate that while environmental factors are progressively influencing purchasing decisions, they remain non-determinative. Retailers and policymakers have an opportunity to accelerate this transition by embedding eco-friendly packaging as the standard rather than the alternative.

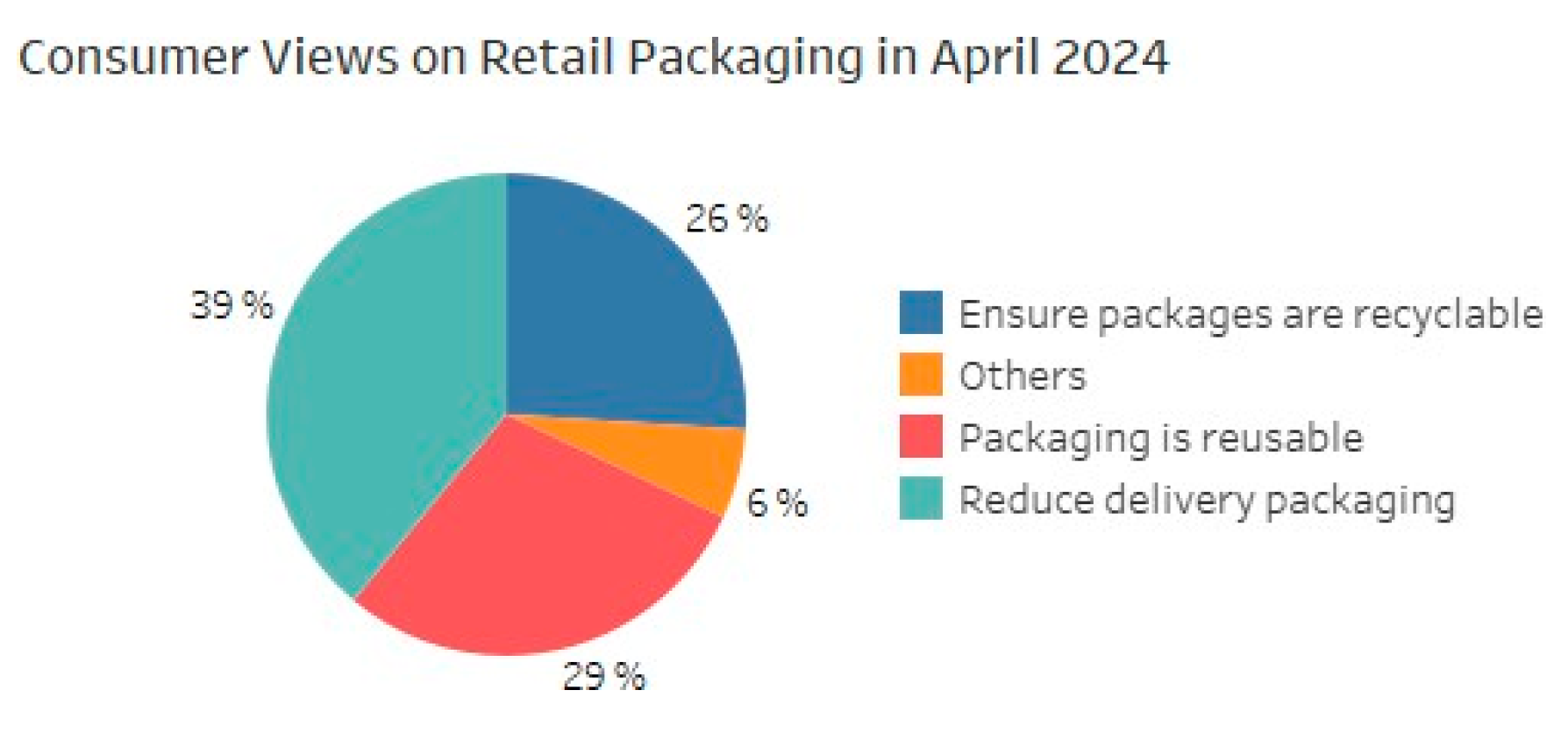

3.2.3. Food Waste: A Mixed Commitment

The chart depicts a disjointed strategy for minimising food waste. A A significant number of Singaporeans are comfortable consuming leftovers and utilising refrigeration to prolong food longevity, demonstrating a pragmatic approach to waste reduction. However, fewer individuals adopt proactive habits like planning grocery lists or buying imperfect or near-expiry items which are simple yet powerful measures that could significantly reduce waste at its source.(National Environment Agency, 2019)

Figure 13.

People’s Actions to Reduce Food Wastage in Singapore in 2019.

Figure 13.

People’s Actions to Reduce Food Wastage in Singapore in 2019.

This indicates that while there is acceptance of waste reduction when it fits seamlessly into existing routines, more deliberate actions that require forethought or a departure from aesthetic norms are less widely embraced. It also emphasises the requirement for both cultural shifts and practical tools like meal planning apps or retail incentives for “imperfect” produce to broaden commitment.

3.2.4. Rethinking Intervention: From Awareness to Behaviour Change

Collectively, all these insights highlight that the population in Singapore acknowledges the significance of sustainability, yet displays a lack of consistent behaviour. People tend to respond more to convenience and incentives than to abstract environmental ideals. This pattern indicates a realistic approach where campaigns and policies should extend beyond mere awareness to actively reform systems and attitudes that facilitate sustainable choices as the most accessible and rewarding alternatives.

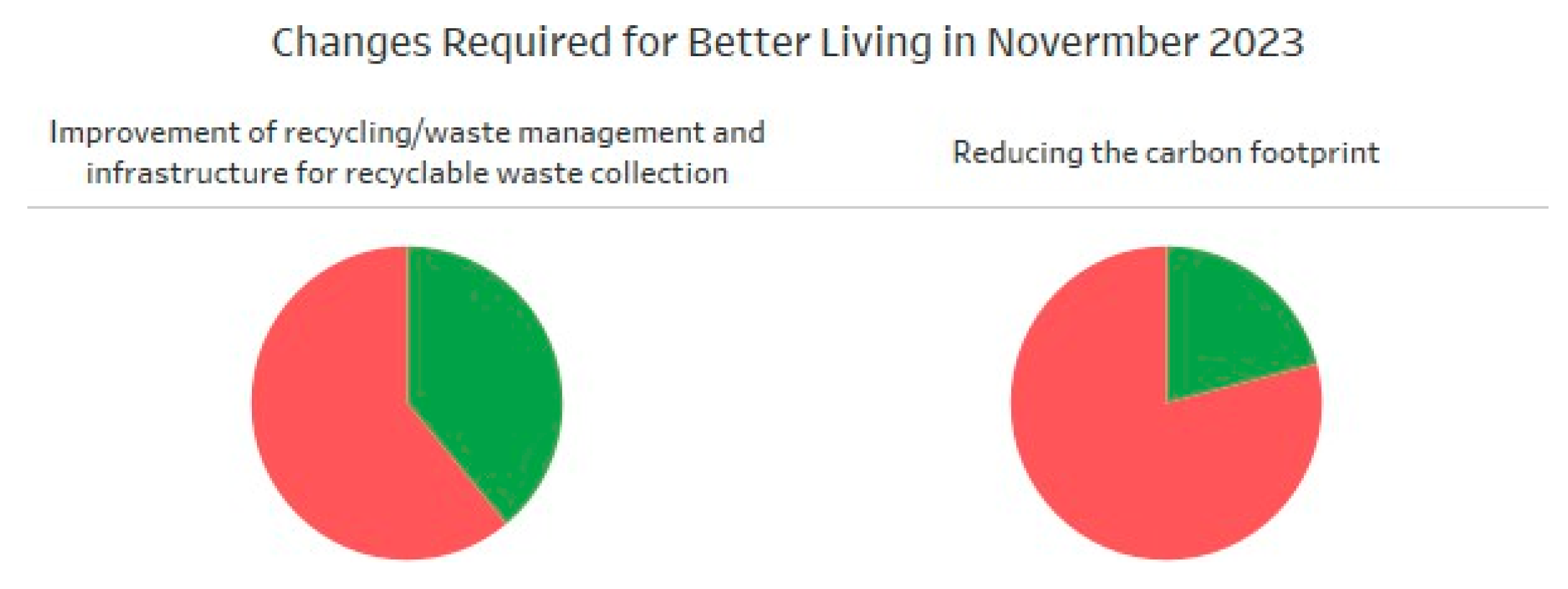

Figure 14.

Changes Required for Better Living in November 2023.

Figure 14.

Changes Required for Better Living in November 2023.

To effectively transform the waste trajectory, Singapore requires continuous community involvement, behavioural incentives, and infrastructural enhancements that tackle these psychological and logistical factors. Only by closing the gap between intention and action can public behaviour evolve from passive awareness to an active force in shaping a low-waste future.

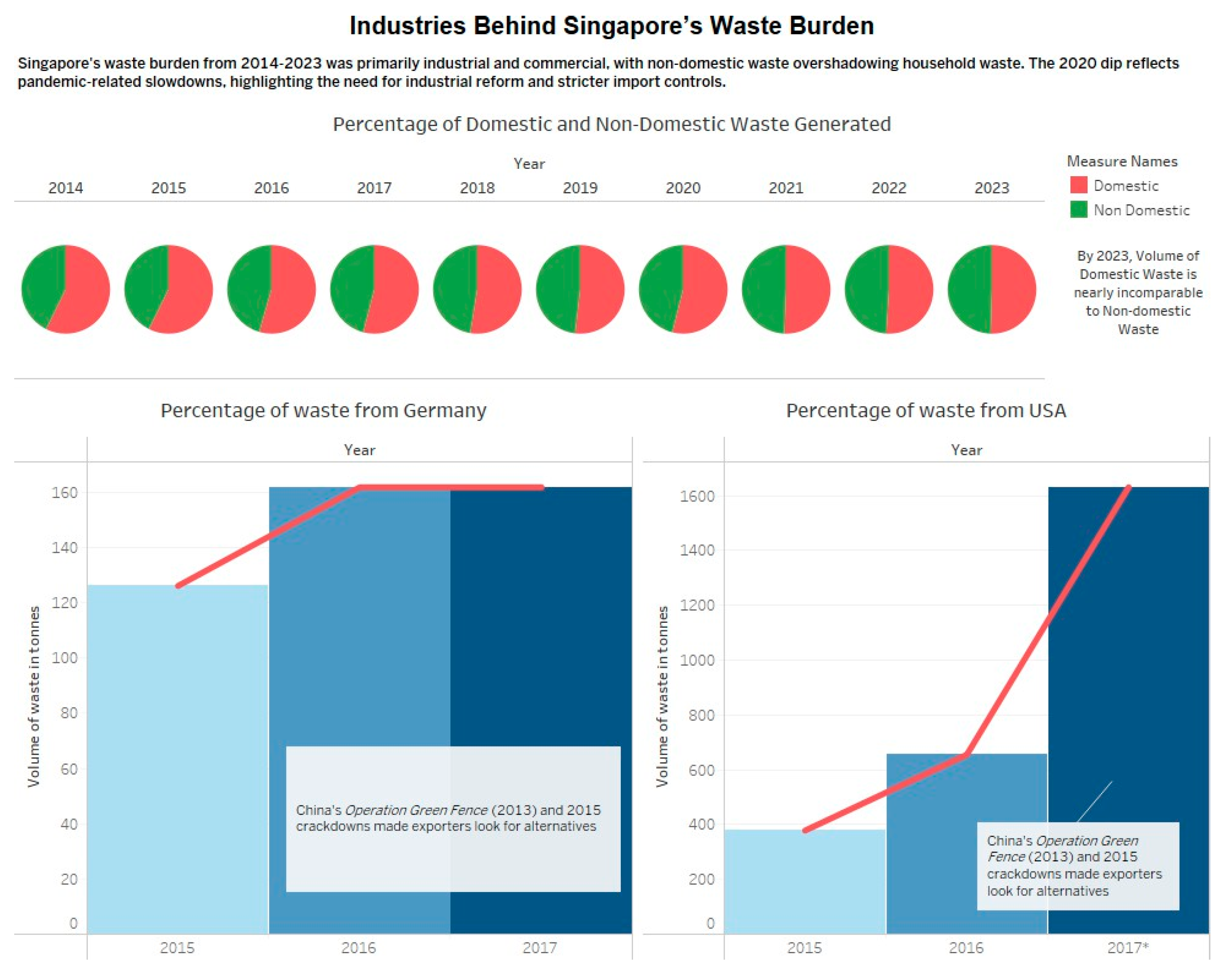

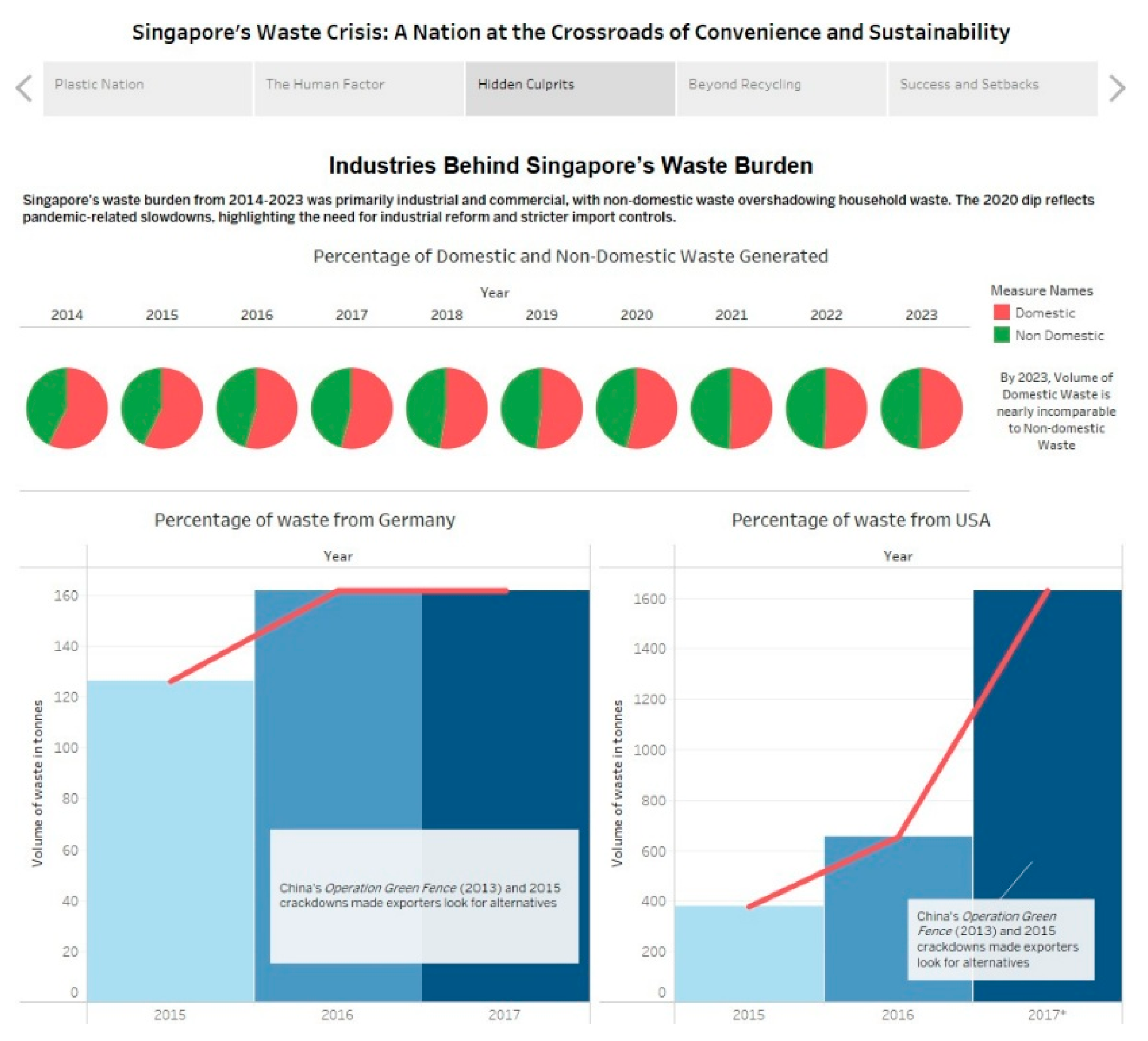

3.3. Hidden Culprits

The waste load in Singapore is mostly influenced by industrial and commercial activities, whereas public discussions often focus on individual recycling practices. Annually, non-domestic sources including industries, enterprises, construction, and institutions, produce the majority of Singapore’s solid trash, far surpassing household contributions. This disparity has persisted over the previous decade, highlighting a fundamental issue: while families are encouraged to recycle and minimise trash, the predominant portion of garbage originates from economic sectors upstream. This exemplifies the phenomenon of "hidden culprits" where sectors and organisations whose waste impacts are less apparent in public discourse, despite evidence indicating they are the primary contributors to the nation's waste volume.

Figure 15.

Hidden Culprits Story Point.

Figure 15.

Hidden Culprits Story Point.

To effectively address Singapore's waste challenge, we must shift the narrative and policy emphasis towards the structural origins of waste, rather than disproportionately highlighting individual consumer responsibility.

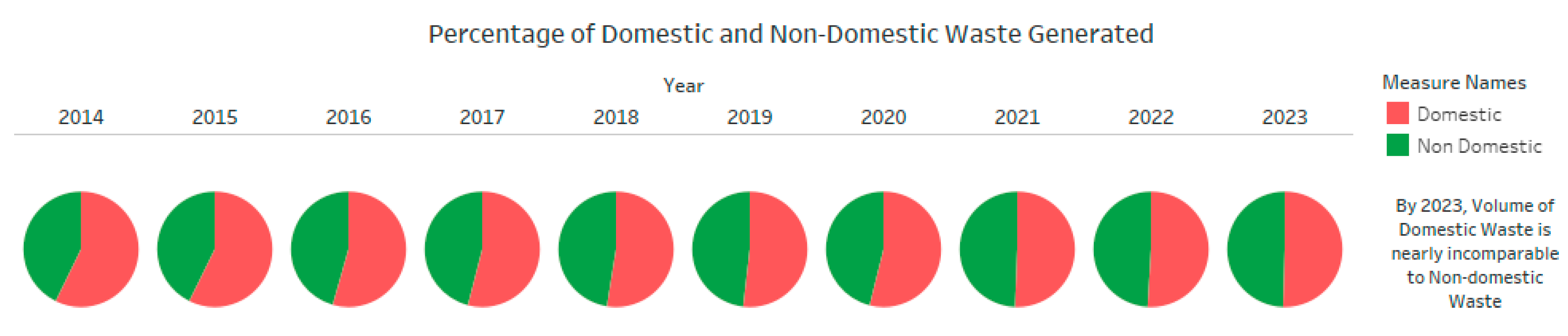

3.3.1. Non-Domestic Waste Is the Dominant Source

The visual analysis of trash volume by source indicates that non-domestic wastes are growing to constitute the majority of Singapore's total waste annually. The pie chart shows that the green section (indicating non-domestic sources) surpasses the red (domestic sources), with the green segments continuously prevailing, irrespective of the year. The evidence is unequivocal: industrial and commercial sectors generate far more garbage than individual homes.

Figure 16.

- Percentage of Domestic and Non-Domestic Waste Generated.

Figure 16.

- Percentage of Domestic and Non-Domestic Waste Generated.

In 2020, despite a decrease in overall waste volume owing to COVID-19 lockdowns, the ratio of domestic to non-domestic garbage remained relatively unchanged. This stability corroborates the assertion that the nation's waste burden is fundamentally linked to non-domestic activities. In contrast, households exert a diminished influence on the overall trajectory of trash generation. (Singapore Department of Statistics, 2024)

3.3.2. Economic Activity Drives Waste Output

The significant decline in 2020, followed by a complete recovery in 2021 and 2022, illustrates the close correlation between Singapore's trash production and its economic development. During the lockdowns, the closure of enterprises and the deceleration of industrial activities led to a significant reduction in non-domestic waste quantities. Nevertheless, with the resumption of business and building operations, waste levels rebounded with equal rapidity.

Figure 17.

Percentage of Waste from Germany.

Figure 17.

Percentage of Waste from Germany.

This tendency indicates that variations in national trash production are mostly influenced by alterations in company practices rather than modifications in consumer behaviour. Although home awareness programs may impact recycling on a minor scale, their influence on national trash volume is negligible compared to choices made in businesses, factories, and commercial kitchens.

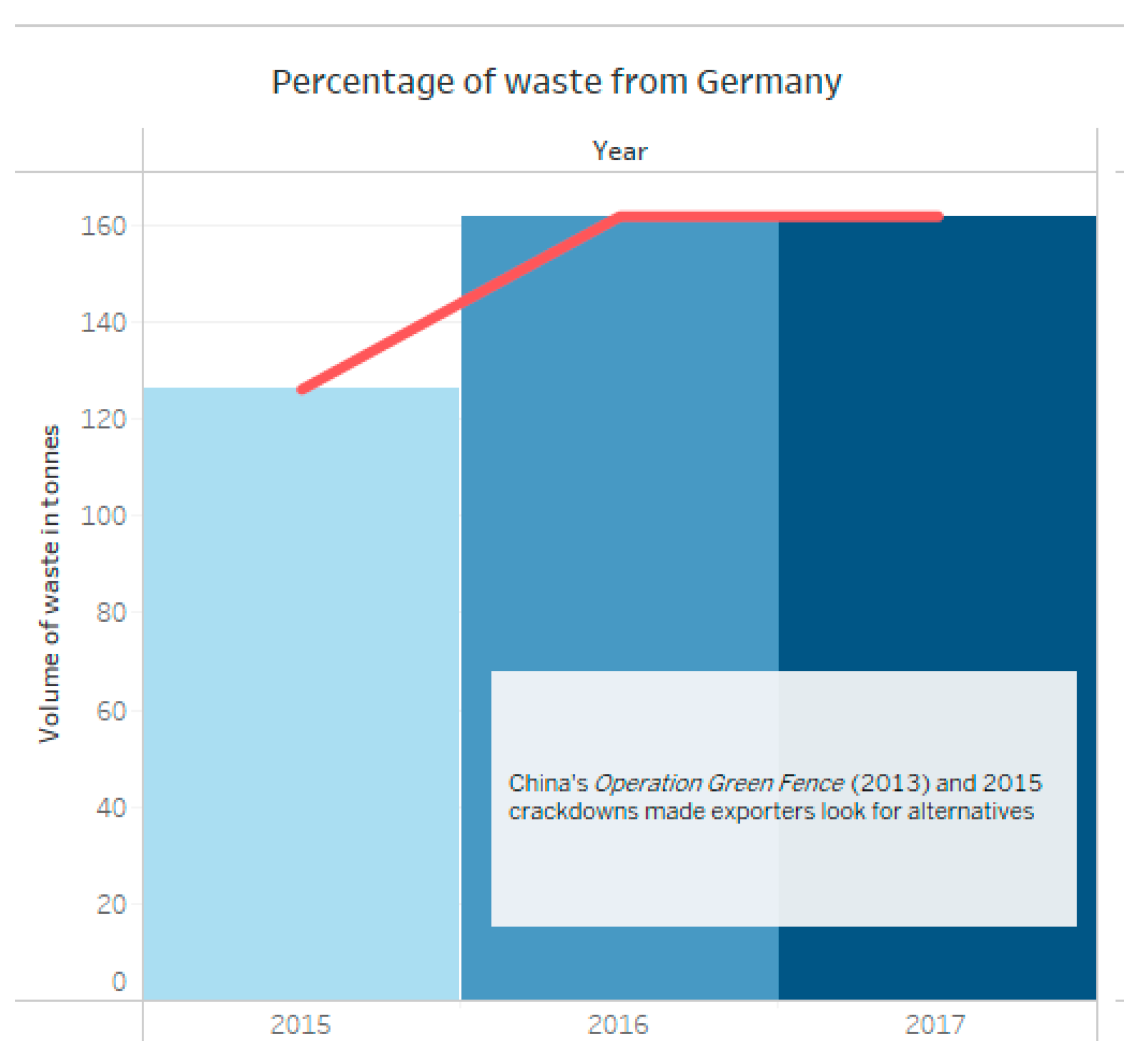

3.3.3. External Pressure Adds to the Burden

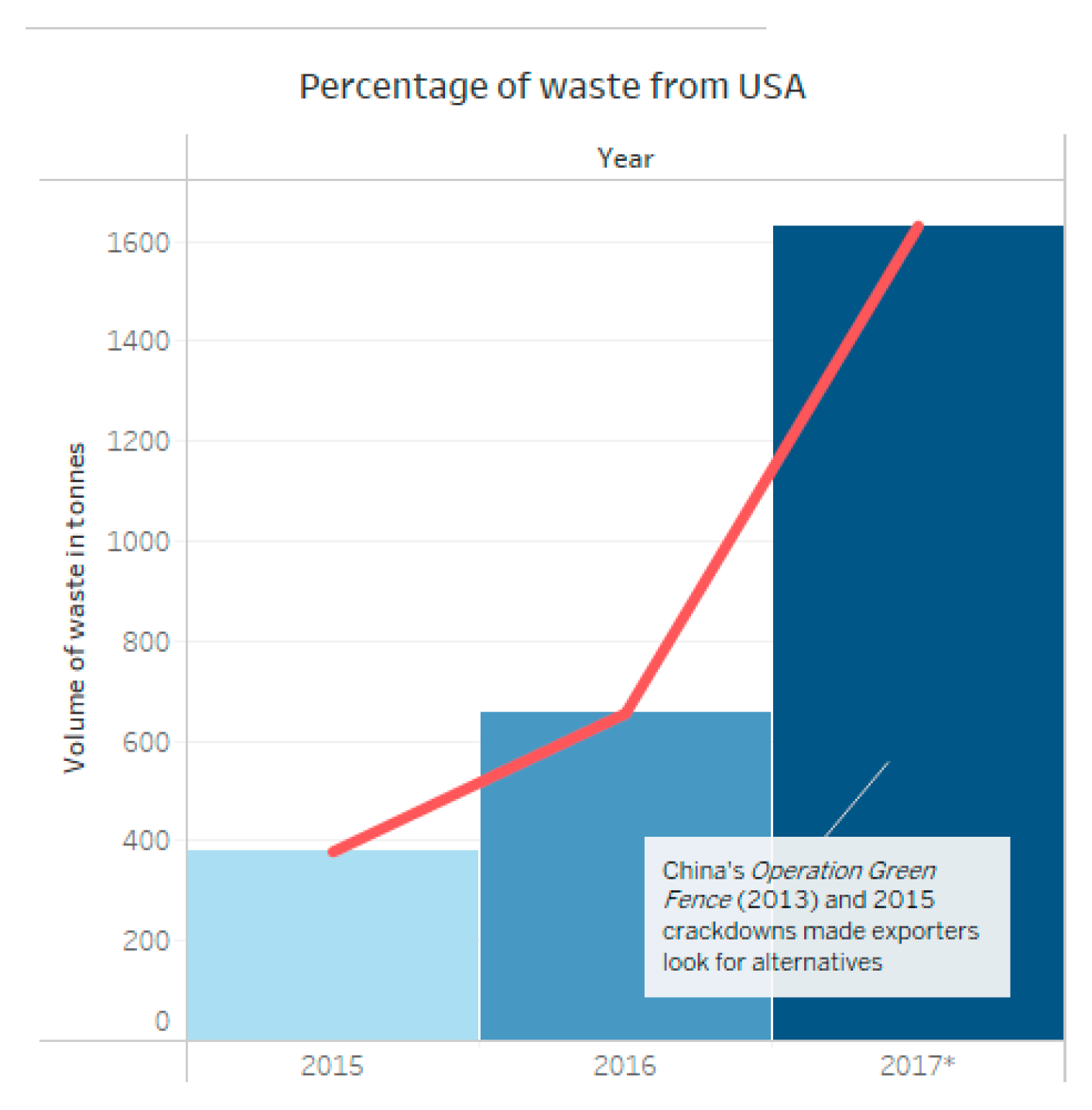

The increase in trash imports from Germany and the USA from 2015 to 2017, seen in the lower two figures, adds an additional aspect to Singapore’s industrial waste profile. These rises corresponded with China's implementation of Operation Green Fence, which imposed stricter regulations on recyclable imports. Consequently, some garbage that was once sent to China has been rerouted to alternative nations, like Singapore. (UN Comtrade, 2019a) (UN Comtrade, 2019b)

Figure 18.

Percentage of Waste from USA.

Figure 18.

Percentage of Waste from USA.

Singapore's capacity to manage or assimilate a portion of this misdirected trash illustrates its function within the global waste ecosystem. Nonetheless, it imposes additional strain on home garbage systems, particularly when incoming volumes include industrial recyclables such as plastics, paper, and metals. The visualisations depict imported garbage as a singular component, although their correlation with global policy shifts, highlights the impact of both local and international variables on Singapore's non-domestic waste burden.

3.3.4. Shifting the Narrative: Homes to Industries

Considering these results, public awareness and trash reduction campaigns should continue to emphasise individual recycling practices. Initiatives encourage households to categorise their recyclables and minimise food waste domestically. However, as the statistics illustrate, domestic contributions are minimal and largely constant, while non-domestic waste propels the total trend.

To achieve significant change, Singapore must realign its narrative and policy initiatives towards the sectors identified as having the most substantial influence. The industrial, commercial, and institutional entities responsible for the green segments in the charts must be held more accountable for the garbage they generate.

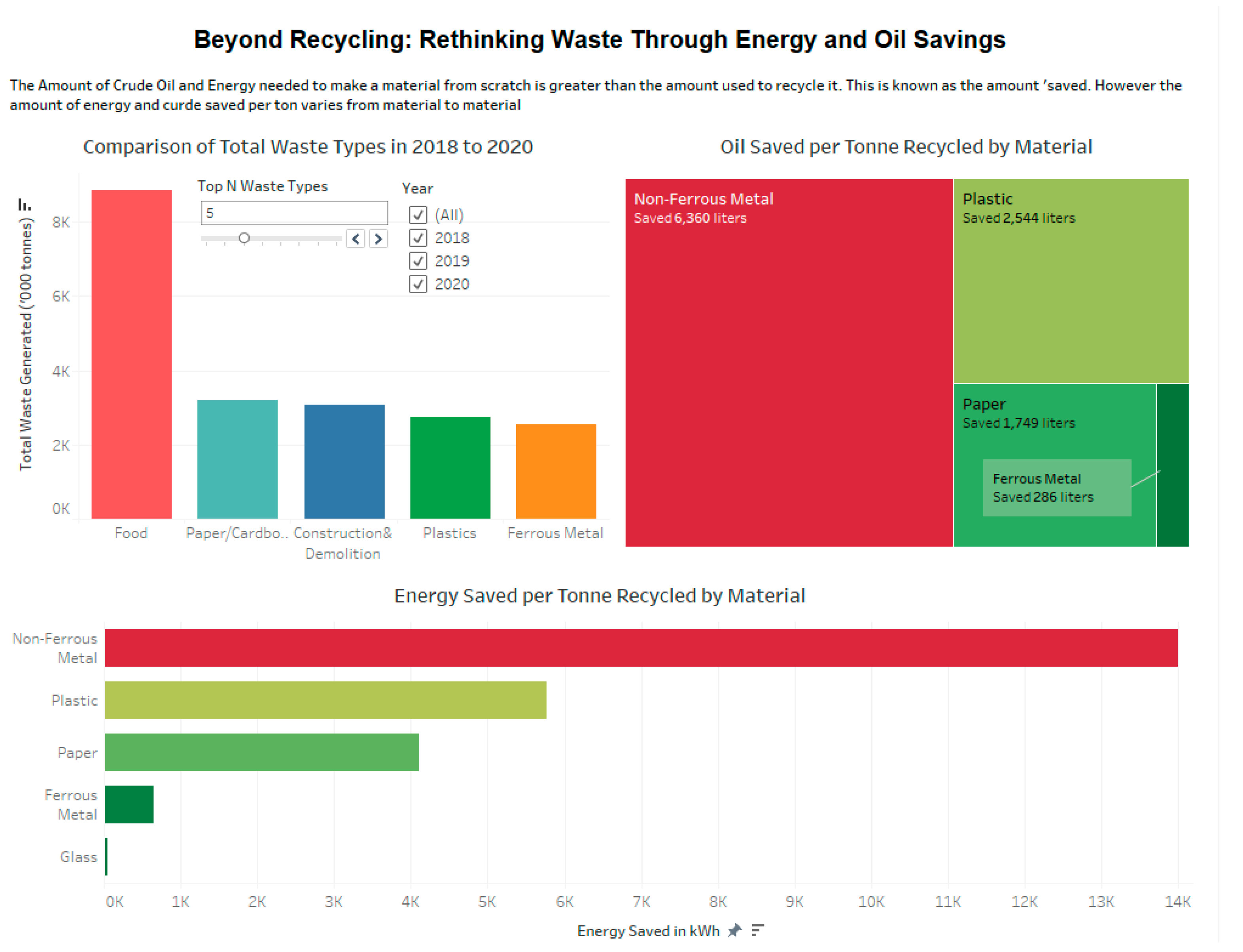

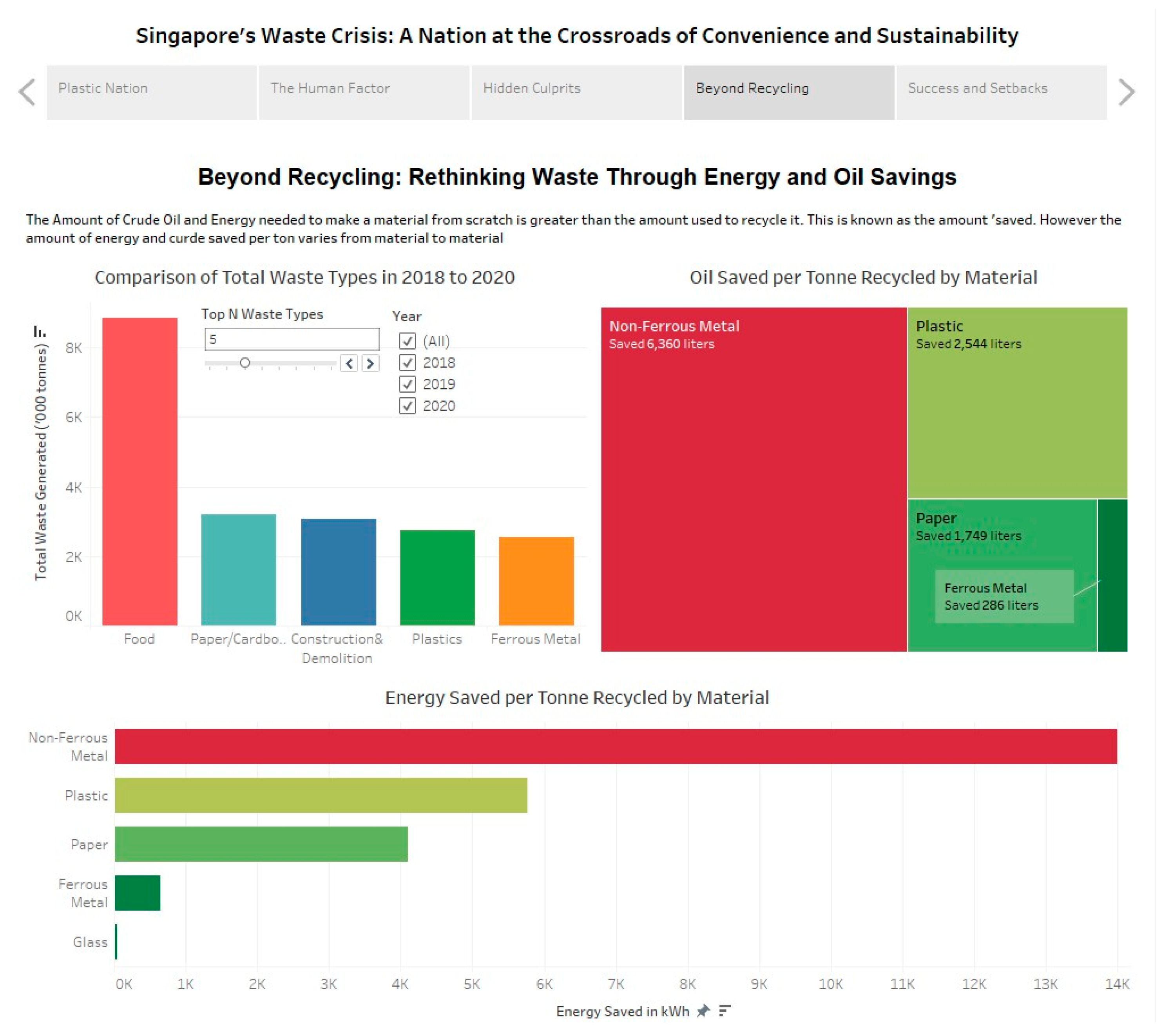

3.4. Beyond Recycling

Singapore’s waste production can be divided into categories for a better understanding. The categories are named after the materials they consist of i.e. Plastic, Paper, Non-Ferrous Metal, etc. While it is indeed crucial to reduce, reuse and recycle (apply the 3 R’s) as much as possible when it comes to waste management, an important factor that often gets ignored is the use of fossil fuels ,i.e. crude oil in Singapore’s case to be exact, and energy in waste management. Despite widespread awareness of the fact that recycling waste conserves crude oil and energy ,in this case electricity to be exact, not many people are aware of the raw details of which materials conserve how much energy and oil. It is necessary that this issue be examined in detail for a better understanding of the problem in order to reduce the pressure on the country’s energy and financial resources.

Figure 19.

Beyond Recycling Story Point.

Figure 19.

Beyond Recycling Story Point.

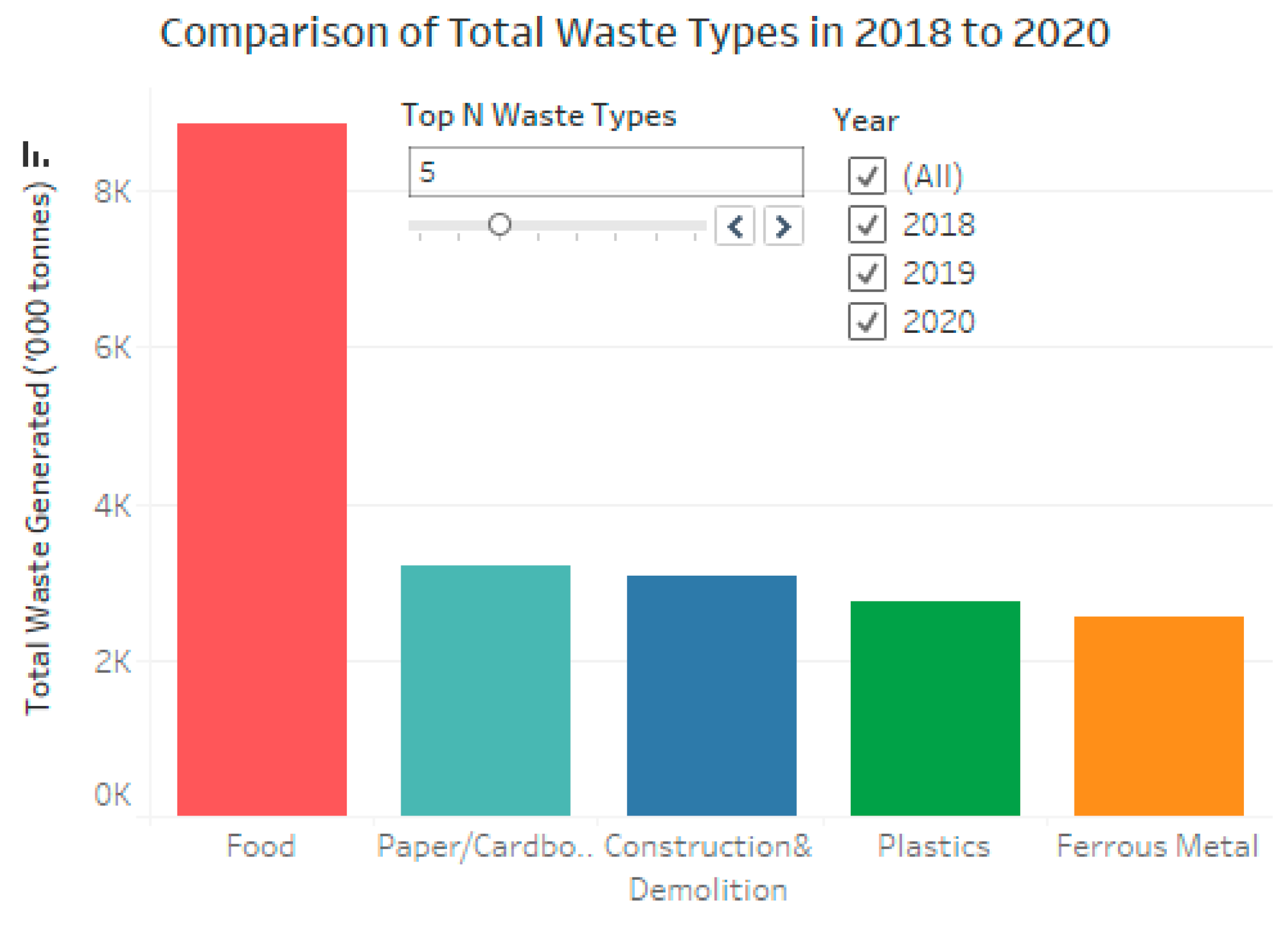

3.4.1. Food Dominates Waste but Lacks Recycling Incentive

The first set of visuals is a vertical bar chart depicting the quantity of total waste generated in kilo metric tons in SIngapore in the years 2018-2020. As can be observed, the trend remains constant throughout the three years. It demonstrates that from the Top 5 leading waste categories, Food waste was the leading one with more than 8,000 kilo metric tons (Singapore Department of Statistics, 2025). However despite this Food does not appear in any of the visualizations about recycling. In fact the leading saver of crude oil and energy in the visuals is Non-Ferrous Metal.

This trend suggests that Food lacks recyclability benefits in terms of crude oil and energy conservation which in turn suggests that a better approach to food waste management will be to reduce the amount of food waste generated as that will be a much more reliable option compared to recycling food waste as it lacks benefits the aforementioned oil and energy returns.

Figure 20.

Comparison of Total Waste Types in 2018 to 2020.

Figure 20.

Comparison of Total Waste Types in 2018 to 2020.

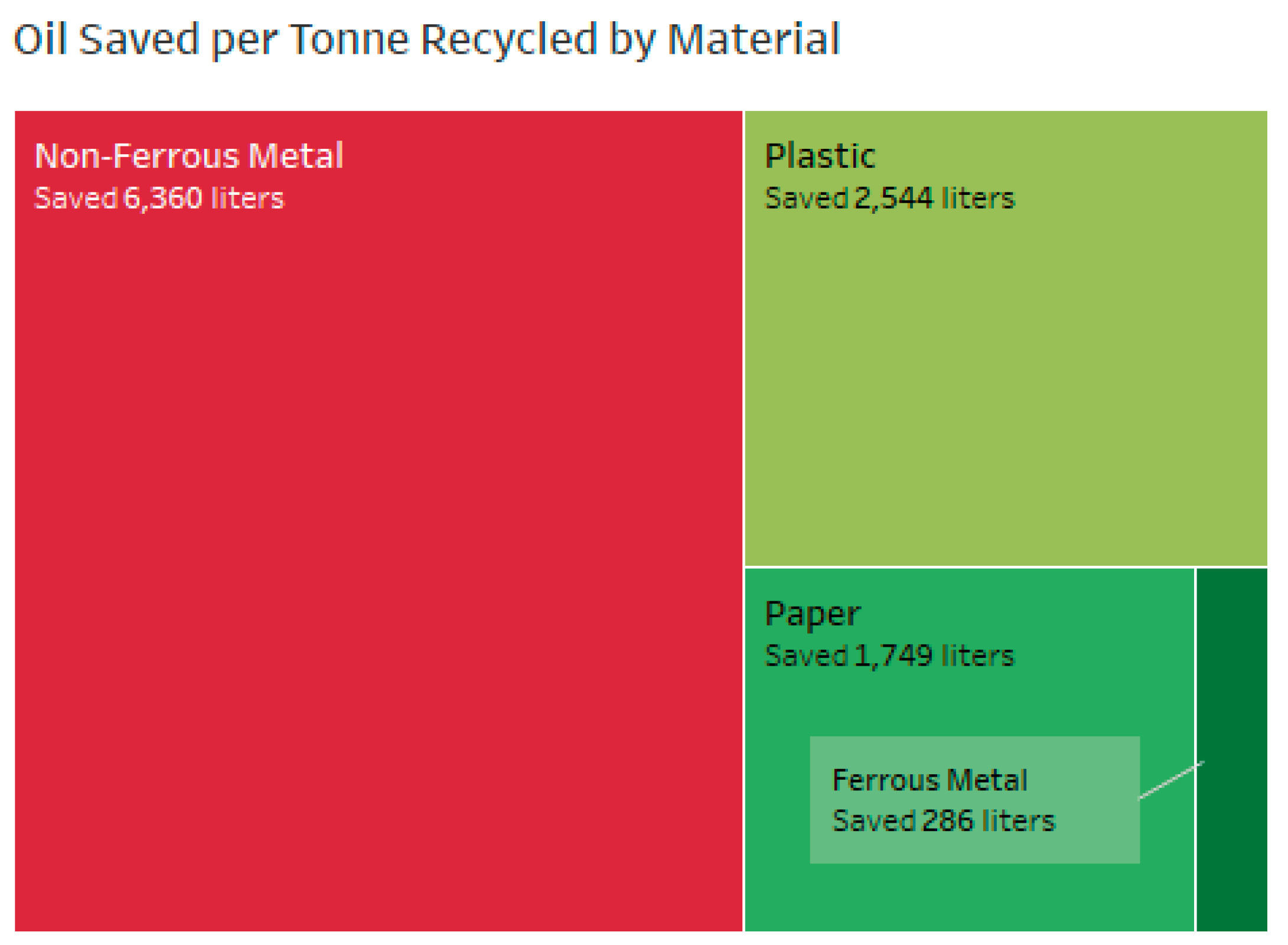

3.4.2. Non-Ferrous Metals Dominate: Crude Oil, Plastic & Paper Rebound

The second visual is a treemap chart which demonstrates the quantity of crude oil (in litres) conserved in recycling the top most Oil-conserving waste materials namely Non-Ferrous Metal, Plastic, Paper and Ferrous Metal. As is demonstrated above, Non-Ferrous metals saved the most crude oil in the years 2018-2020 at 6,360 liters followed by Plastic (2,544 litres) and Paper (at 1,749 litres). Ferrous Metal came in fourth position saving 286 litres (Awan, 2021). The key takeaway from this visualization is that there is a massive incentive in terms of crude oil and energy conservation to recycle Non-Ferrous Metal, Plastic and Paper. Government policymakers should utilize this incentive to promote recycling these materials as priority as it saves the country money on energy and oil imports.

Figure 21.

Oil Saved per Tonne Recycled by Material.

Figure 21.

Oil Saved per Tonne Recycled by Material.

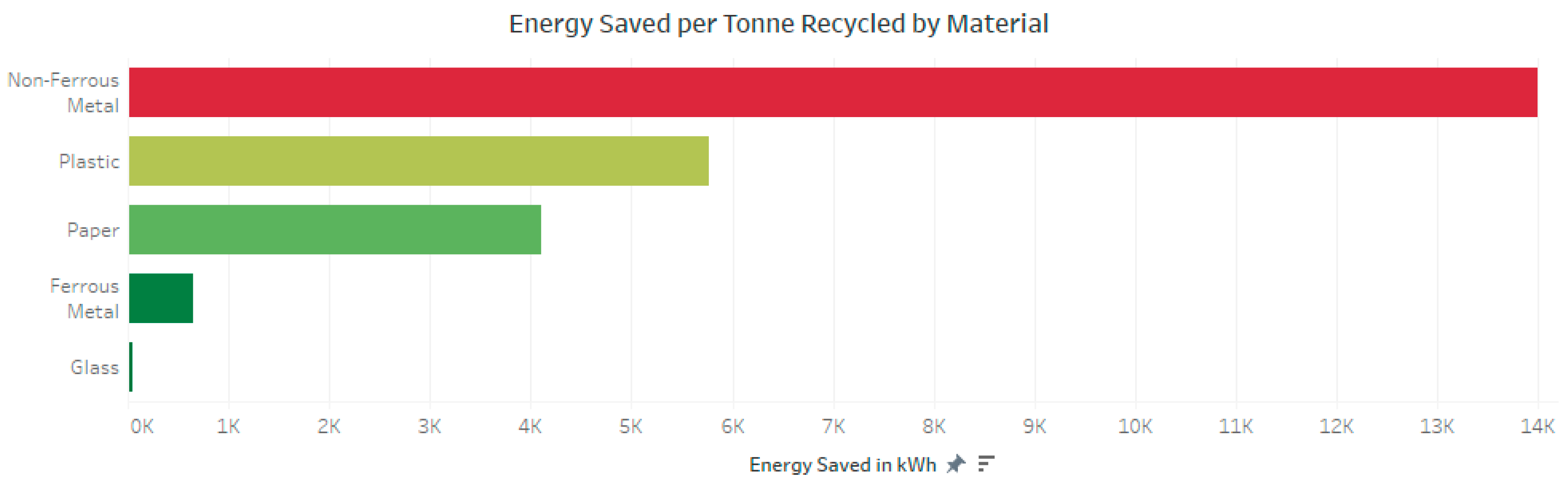

3.4.3. Glass Returns Lesser than Expected

The third and last visual is a horizontal bar chart which demonstrates the amount of energy (in kWh) conserved in recycling the top most Energy-conserving materials namely Non-Ferrous Metals (14,000 kWh), Plastic (5,800 kWh), Paper (4,100 kWh), Ferrous Metal (600 kWh), and Glass with less than 500 kWh (nearly 100 kWh). This demonstrates that Glass conserves very little energy when recycled in comparison to the other materials.

Figure 22.

Energy Saved per Tonne Recycled by Material.

Figure 22.

Energy Saved per Tonne Recycled by Material.

The key takeaway from this insight is that although recycling glass can be beneficial in terms of the fact that it reduce landfill space and therefore reduces pollution but it does not provide the incentive of conserving energy when recycled so the government should subsidize it’s recycling to ensure it does not get abandoned but at the same time should promote policies to support the recycling of Non-Ferrous Metals, Plastic, Paper, and Ferrous Metal as they conserve much more significant amount of energy when recycled.

3.4.4. The Way Forward: Suggested Policies

Considering the aforementioned results, food was the leading category of waste produced but also the least recycled so the government policymakers should come up with ways to reduce food waste as there is no incentive to recycle it in terms of crude oil and energy conserving (Singapore Department of Statistics, 2025).

Non-Ferrous Metals, Plastic, and Paper saved the most amount of crude oil with the top runner being Ferrous Metals (Awan, 2021). The government should implement policies to prioritise the recycling of these materials as they save the government a lot of money on oil imports and this saved money can be reinvested into other waste management initiatives.

Glass, to many people’s surprise, saves much less energy in kWh than expected (Awan, 2021). As a result, there is no incentive in terms of conserving crude oil and energy when it comes to recycling glass. However, the government can still subsidize glass recycling to reduce landfill space and protect the environment in the long run.

To conclude, the aforementioned policy measures can be implemented by the government policymakers to maximize the conservation of crude oil and energy via recycling waste while also saving financial and natural resources for the country which can be put for use on other initiatives in the future.

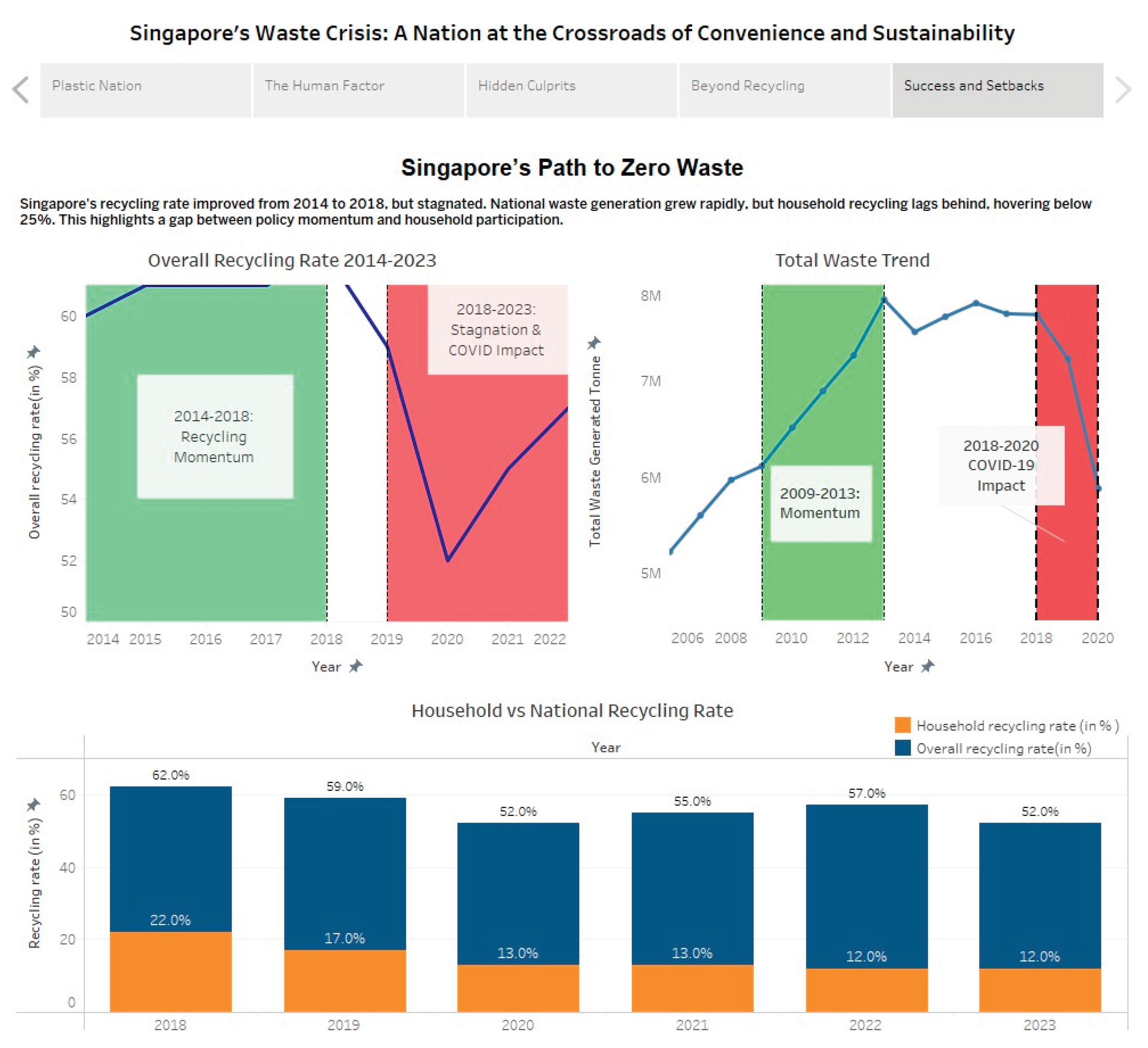

3.5. Success and Setbacks

The images of the Singaporean model of achieving zero waste narrate the story of a promising start that is being clouded by current stagnation and a growing divide in terms of involvement. Chronologically, the rate of recycling in the country has been on an upward trend since the year 2014, where the rate exceeded 60% until the year 2018, at which point it flatlined due to policy fatigue and the emerging impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The second chart shows that overall waste generation increased almost twice by 2014, but it stopped at eight million tonnes, although it had started on a high note. The third graph reveals the household system disjuncture as individual recycling rates stand only at 12%-22%, whereas the national average is above 50%. In their combination, these images highlight the idea that although top-down programs may be efficient to achieve meaningful change, in the long term, the policy-realization gap will need to be bridged by including all households in the pathway of zero waste.

Figure 23.

Success and Setbacks Story Point.

Figure 23.

Success and Setbacks Story Point.

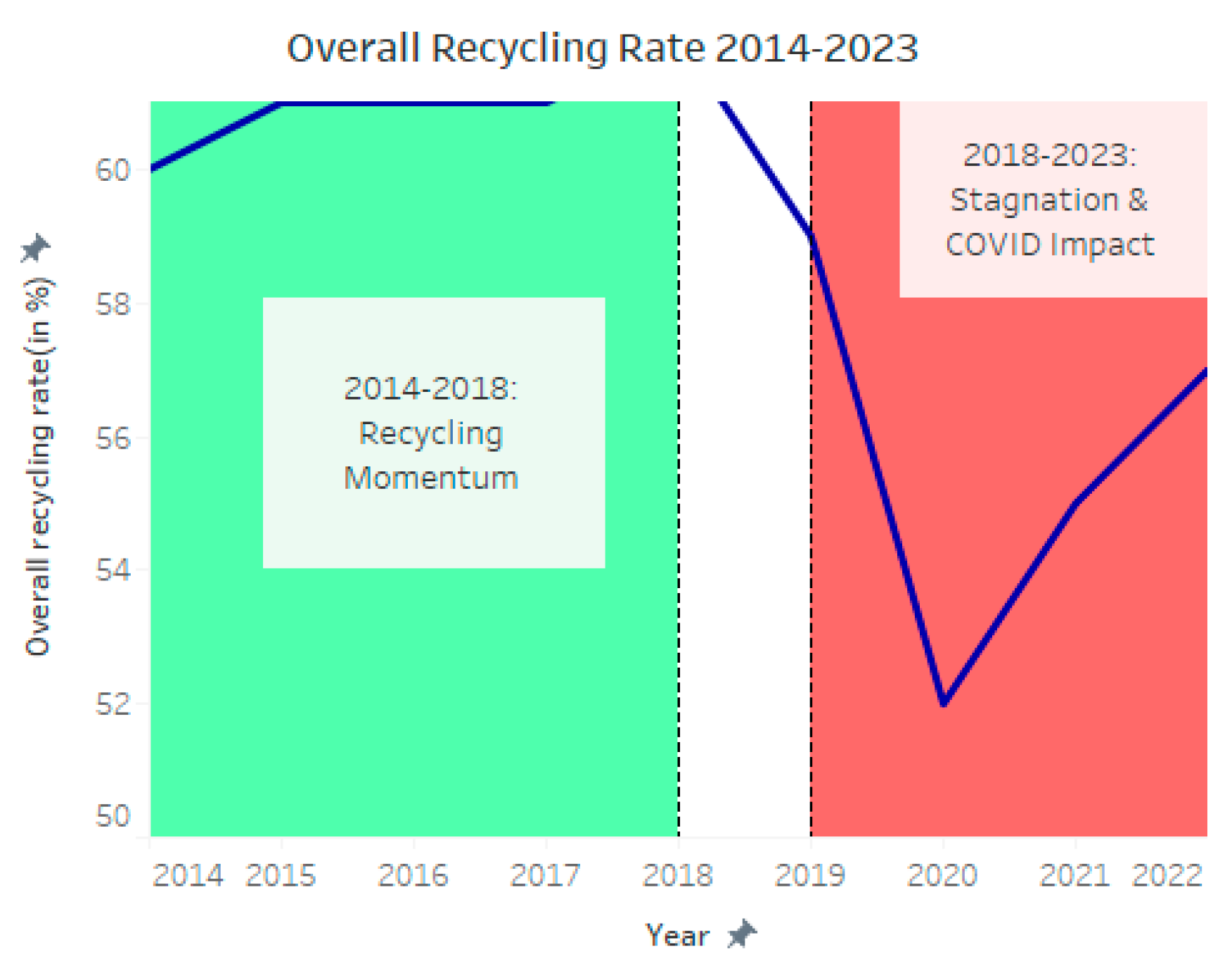

3.5.1. First Wave in Recycling Expansion (2014 2018)

Recycling rates in Singapore have been gradually increasing since 2014, when the rates were about 58%, rising to above 62% in 2018, due to successful recycling initiatives like the National Recycling Programme and an increased number of collection infrastructures (NEA, 2022 ). Approximately in 2013, these critical drop phases of momentum are reflected by the green focus band on the Overall Recycling Rate line chart and the callout of “Recycling Momentum,” reflecting their close match with specific policy initiatives, investments, and enabling the activities of national public and private partners.

Figure 24.

Figure 24. Success and Setbacks Story Point.

Figure 24.

Figure 24. Success and Setbacks Story Point.

3.5.2. Pandemic and Stagnation (2018-2023)

The recycling trend stalled after 2018 and plummeted in 2020 before rebounding somewhat within the red band on the same graph, indicating the stagnation effect due to various factors, including lucrative importation levels and the COVID-19 impact. There is a similar trend in the Total Waste Trend line, as it reveals that after creating only 5.2 million tonnes in 2003, total waste generation began to skyrocket to almost 8 million tonnes by the year 2014 and now hovers around the eight million tonne mark without any obvious decrease (NEA, 2023). Despite the fact that COVID-19 restrictions had temporarily decreased the volume of waste, it returned immediately after the restart of economic activity, meaning that external shocks do not lead to lasting progress without the reintroduction of policy innovation (NEA, 2022).

Figure 25.

Total Waste Trend.

Figure 25.

Total Waste Trend.

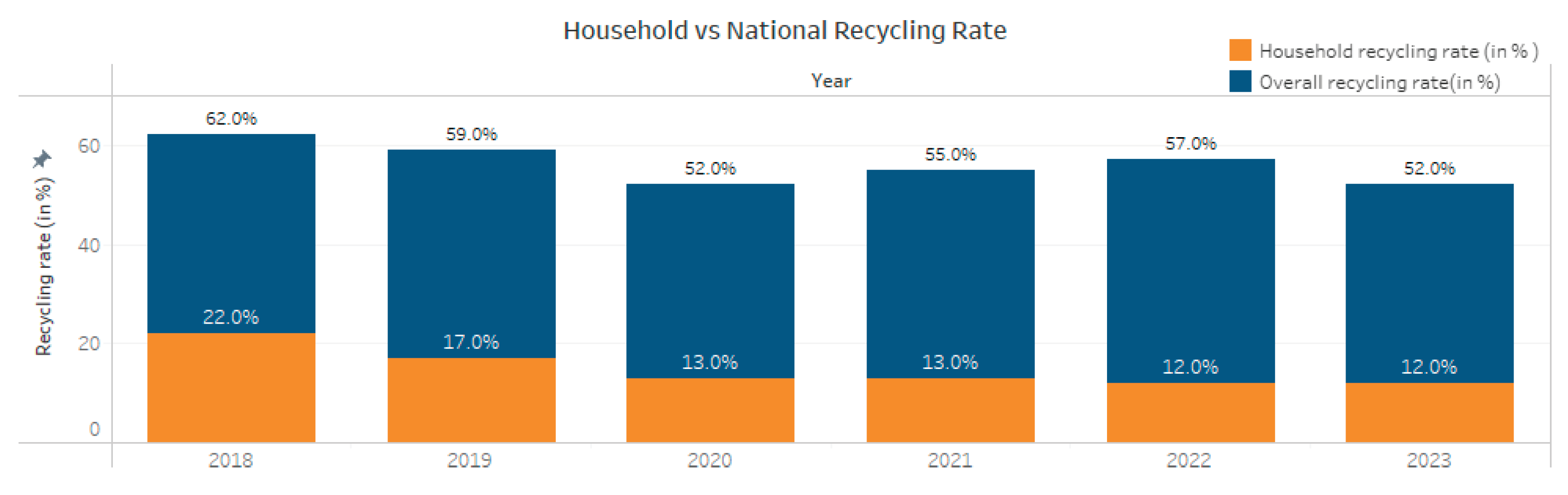

3.5.3. The Gap in Household Participation (2018-2023)

Household recycling rates were stuck at a relatively lower figure of between 12% and 22%, with the highest peak in 2018, and gradually declining since then displayed on the Household vs National Recycling Rate stacked bars, whereas the national ones were between 52% and 57%. The studies have been able to bear out the importance of convenience and subjective effort as the barriers to household engagement, even in a highly urbanized environment such as Singapore (Muniandy et al., 2021).

Figure 26.

Household vs National Recycling Rate.

Figure 26.

Household vs National Recycling Rate.

3.5.4. Policy to Practice: A Way Forward

All three of these images narrate a story about initial success followed by stagnation and a gap between system performance and the action of individuals. In a bid to reach its target of a Zero Waste by 2035, Singapore should re-energize the wave of the mid-2010s by combining upstream, systemic policies, including obligatory food-waste segregation, extended producer responsibility, and focused, household-level programs. The identified behavioral barriers of the recent studies can be overcome by firmly increasing convenience by facilitating the large availability of food waste bins, real-time recycling feedback apps, and community reward systems (Muniandy et al., 2021). By matching the national policy with the daily practice, Singapore will only bridge the gap between the policy momentum and participation in households.