Submitted:

09 December 2025

Posted:

10 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

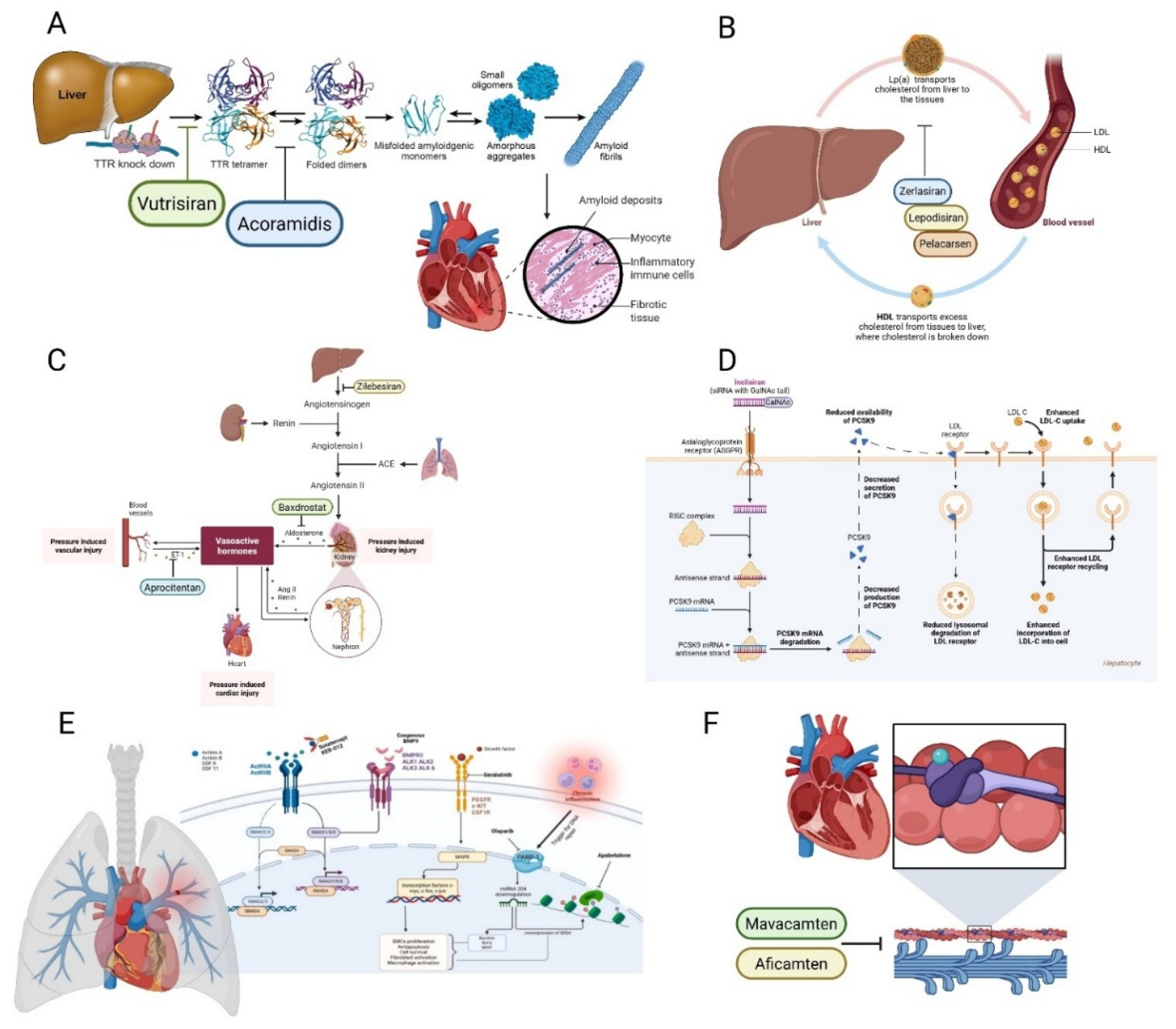

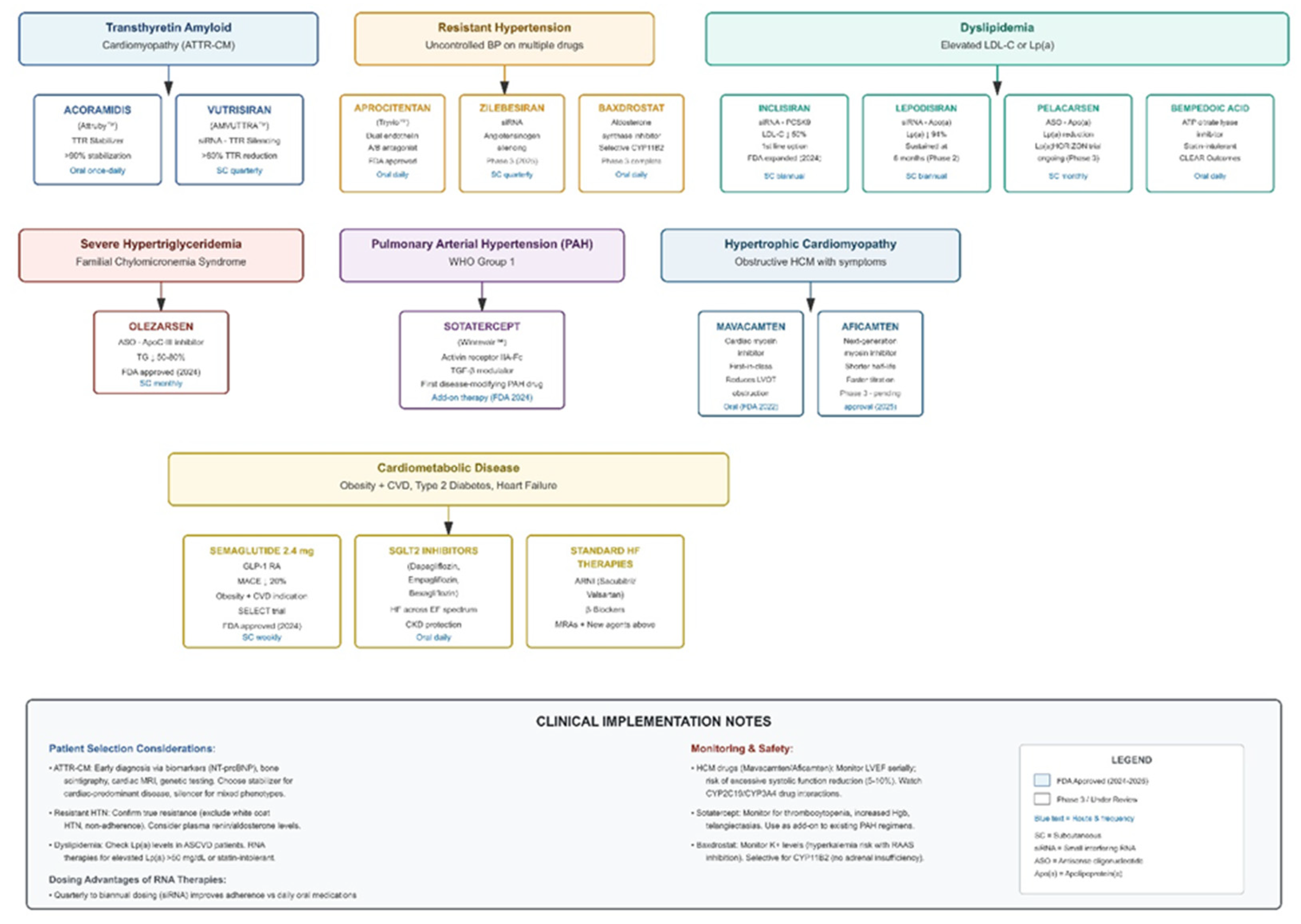

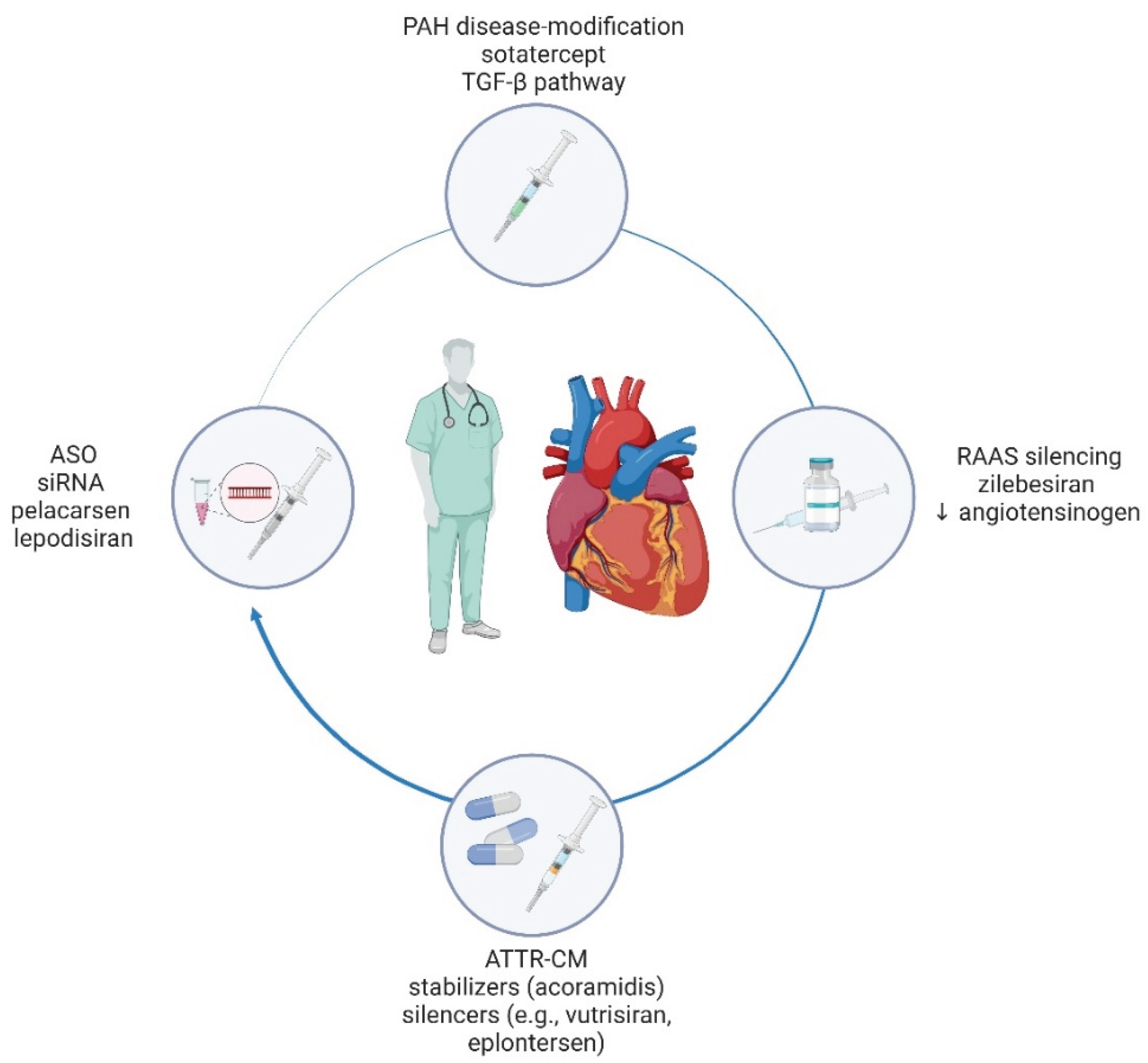

Background/Objectives: Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of global morbidity and mortality. Although substantial therapeutic advances have been made over the past decades, the years 2024–2025 mark a turning point characterized by the emergence of mechanistically innovative, disease-modifying therapies that go beyond conventional risk-factor control. This narrative review aims to synthesize transformative pharmacological and regulatory milestones reshaping contemporary cardiovascular practice and establishing a roadmap for precision medicine implementation. Methods: We conducted a comprehensive narrative review of pivotal clinical trials, regulatory approvals and mechanistic frameworks for emerging cardiovascular therapeutics approved or under investigation during 2024–2025. The analysis encompasses novel agents across multiple disease domains including transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM), resistant hypertension, dyslipidemia, pulmonary arterial hypertension, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and cardiometabolic disease, with emphasis on their molecular targets, clinical efficacy, and practice-changing implications. Results: Key therapeutic advances include acoramidis and vutrisiran for ATTR-CM demonstrating significant reductions in cardiovascular mortality and hospitalization; aprocitentan for resistant hypertension alongside investigational angiotensinogen silencers and aldosterone synthase inhibitors; RNA-based dyslipidemia therapies (inclisiran, lepodisiran, pelacarsen, olezarsen) enabling durable lipid control; sotatercept introducing disease modification in pulmonary arterial hypertension; cardiac myosin inhibitors (mavacamten, aficamten) transforming hypertrophic cardiomyopathy management; and GLP-1 receptor agonist semaglutide receiving FDA approval for cardiovascular risk reduction in obesity. These agents collectively demonstrate mechanistic targeting, genetic precision, and disease modification beyond traditional risk-factor management. Conclusions: Cardiovascular medicine is transitioning from symptomatic palliation toward an era defined by molecular pathway targeting, individualized therapy, and durable disease control, establishing a new paradigm for precision cardiovascular care.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Literature Search

3. Results

3.1. Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM): Stabilizers and Silencers

3.2. Lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] Targeting: Antisense and siRNA

3.3. Hypertension: Upstream Modulation of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS) Axis

3.4. Heart Failure: Consolidation and Refinement

3.5. Lipid and Triglyceride Modulation Beyond Statins

3.6. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH): A First-In-Class TGF-β Superfamily Modulator

3.7. Cardiometabolic Therapies with Cardiovascular Outcome Benefits

3.8. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM): Cardiac Myosin Inhibition

4. Discussion

4.1. Challenges, Open Questions, and Future Directions

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 6MWD | 6-minute walk distance |

| ACE | Angiotensin-converting enzyme |

| ANGPTL3 | Angiopoietin-like protein 3 |

| ARB | Angiotensin receptor blocker |

| ARNI | Angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor |

| ASCVD | Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease |

| ASO | Antisense oligonucleotide |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| ATTR-CM | Transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy |

| Apo(a) | Apolipoprotein(a) |

| ApoC-III | Apolipoprotein C-III |

| BMPR2 | Bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2 |

| BP | Blood pressure |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| CRISPR | Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats |

| CV | Cardiovascular |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| CYP11B1 | Cytochrome P450 family 11 subfamily B member 1 |

| CYP11B2 | Cytochrome P450 family 11 subfamily B member 2 (aldosterone synthase) |

| CYP2C19 | Cytochrome P450 2C19 |

| CYP3A4 | Cytochrome P450 3A4 |

| EF | Ejection fraction |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| FCS | Familial chylomicronemia syndrome |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration (United States) |

| GDF | Growth differentiation factor |

| GDMT | Guideline-directed medical therapy |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| GLP-1 RA | Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist |

| GalNAc | N-acetylgalactosamine |

| HCM | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| HF | Heart failure |

| HFpEF | Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| HFrEF | Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction |

| HMG-CoA | Hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A |

| HTN | Hypertension |

| Hgb | Hemoglobin |

| HoFH | Homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia |

| K⁺ | Potassium |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| LDL-C | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| LNP | Lipid nanoparticle |

| LVEF | Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| LVOT | Left ventricular outflow tract |

| Lp(a) | Lipoprotein(a) |

| MACE | Major adverse cardiovascular events |

| MI | Myocardial infarction |

| MRA | Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| MSC | Mesenchymal stem cell |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide |

| NYHA | New York Heart Association |

| PAH | Pulmonary arterial hypertension |

| PCSK9 | Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 |

| PDE5 | Phosphodiesterase type 5 |

| RAAS | Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| SANRA | Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

| SC | Subcutaneous |

| SGLT2 | Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 |

| TG | Triglyceride |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-beta |

| TTR | Transthyretin |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| cGMP | Cyclic guanosine monophosphate |

| hsCRP | High-sensitivity C-reactive protein |

| mRNA | Messenger ribonucleic acid |

| pVO₂ | Peak oxygen consumption |

| sGC | Soluble guanylate cyclase |

| siRNA | Small interfering RNA |

References

- Townsend, N.; Kazakiewicz, D.; Lucy Wright, F.; Timmis, A.; Huculeci, R.; Torbica, A.; Gale, C.P.; Achenbach, S.; Weidinger, F.; Vardas, P. Epidemiology of Cardiovascular Disease in Europe. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2022, 19, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenzuela, P.L.; Carrera-Bastos, P.; Castillo-García, A.; Lieberman, D.E.; Santos-Lozano, A.; Lucia, A. Obesity and the Risk of Cardiometabolic Diseases. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A. Acoramidis: First Approval. Drugs 2025, 85, 833–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judge, D.P.; Gillmore, J.D.; Alexander, K.M.; Ambardekar, A.V.; Cappelli, F.; Fontana, M.; García-Pavía, P.; Grodin, J.L.; Grogan, M.; Hanna, M.; et al. Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Acoramidis in ATTR-CM: Initial Report From the Open-Label Extension of the ATTRibute-CM Trial. Circulation 2025, 151, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, S. Aprocitentan: First Approval. Drugs 2024, 84, 841–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaich, M.P.; Bellet, M.; Weber, M.A.; Danaietash, P.; Bakris, G.L.; Flack, J.M.; Dreier, R.F.; Sassi-Sayadi, M.; Haskell, L.P.; Narkiewicz, K.; et al. Dual Endothelin Antagonist Aprocitentan for Resistant Hypertension (PRECISION): A Multicentre, Blinded, Randomised, Parallel-Group, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2022, 400, 1927–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commissioner, O. of the FDA Approves First Treatment to Reduce Risk of Serious Heart Problems Specifically in Adults with Obesity or Overweight. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-treatment-reduce-risk-serious-heart-problems-specifically-adults-obesity-or (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Vogel, J.; Carpinteiro, A.; Luedike, P.; Buehning, F.; Wernhart, S.; Rassaf, T.; Michel, L. Current Therapies and Future Horizons in Cardiac Amyloidosis Treatment. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2024, 21, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, G.B.; Dhaun, N. Endothelin Antagonism: A New Era for Resistant Hypertension? Hypertens Dallas Tex 2025, 82, 611–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarade, C.; Zolotarova, T.; Moiz, A.; Eisenberg, M.J. GLP-1-Based Therapies for the Treatment of Resistant Hypertension in Individuals with Overweight or Obesity: A Review. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 75, 102789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baethge, C.; Goldbeck-Wood, S.; Mertens, S. SANRA-a Scale for the Quality Assessment of Narrative Review Articles. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2019, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costabel, J.P.; Suárez, L.L.; Rochlani, Y.; Masri, A.; Slipczuk, L.; Berrios, E. Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy: Evolving Therapies, Expanding Hope. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillmore, J.D.; Judge, D.P.; Cappelli, F.; Fontana, M.; Garcia-Pavia, P.; Gibbs, S.; Grogan, M.; Hanna, M.; Hoffman, J.; Masri, A.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Acoramidis in Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judge, D.P.; Alexander, K.M.; Cappelli, F.; Fontana, M.; Garcia-Pavia, P.; Gibbs, S.D.J.; Grogan, M.; Hanna, M.; Masri, A.; Maurer, M.S.; et al. Efficacy of Acoramidis on All-Cause Mortality and Cardiovascular Hospitalization in Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025, 85, 1003–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Pavia, P.; Grogan, M.; Kale, P.; Berk, J.L.; Maurer, M.S.; Conceição, I.; Di Carli, M.; Solomon, S.D.; Chen, C.; Yureneva, E.; et al. Impact of Vutrisiran on Exploratory Cardiac Parameters in Hereditary Transthyretin-Mediated Amyloidosis with Polyneuropathy. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2024, 26, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, M.; Berk, J.L.; Gillmore, J.D.; Witteles, R.M.; Grogan, M.; Drachman, B.; Damy, T.; Garcia-Pavia, P.; Taubel, J.; Solomon, S.D.; et al. Vutrisiran in Patients with Transthyretin Amyloidosis with Cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciffone, N.; McNeal, C.J.; McGowan, M.P.; Ferdinand, K.C. Lipoprotein(a): An Important Piece of the ASCVD Risk Factor Puzzle across Diverse Populations. Am. Heart Hournal Plus Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2023, 38, 100350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anchouche, K.; Thanassoulis, G. Lp(a): A Rapidly Evolving Therapeutic Landscape. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2024, 27, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, H.S.; Bajaj, A.; Goonewardena, S.N.; Moriarty, P.M. Pelacarsen: Mechanism of Action and Lp(a)-Lowering Effect. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2025, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepodisiran - A Long-Duration Small Interfering RNA Targeting Lipoprotein(a) - PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40162643/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Cho, L.; Nicholls, S.J.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Landmesser, U.; Tsimikas, S.; Blaha, M.J.; Leitersdorf, E.; Lincoff, A.M.; Lesogor, A.; Manning, B.; et al. Design and Rationale of Lp(a)HORIZON Trial: Assessing the Effect of Lipoprotein(a) Lowering With Pelacarsen on Major Cardiovascular Events in Patients With CVD and Elevated Lp(a). Am. Heart J. 2025, 287, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanbay, M.; Ozbek, L.; Guldan, M.; Yilmaz, Z.Y.; Ortiz, A.; Mallamaci, F.; Zoccali, C. siRNA-Based Therapeutics for Lipoprotein (a) Lowering: A Path toward Precision Cardiovascular Medicine. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2025, 55, e70079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakris, G.L.; Saxena, M.; Gupta, A.; Chalhoub, F.; Lee, J.; Stiglitz, D.; Makarova, N.; Goyal, N.; Guo, W.; Zappe, D.; et al. RNA Interference With Zilebesiran for Mild to Moderate Hypertension: The KARDIA-1 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2024, 331, 740–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, E.; Siddiqui, A.H.; Moeed, A.; Laique, F.; Najeeb, H.; Al Hasibuzzaman, M. Advancing Hypertension Management: The Role of Zilebesiran as an siRNA Therapeutic Agent. Ann. Med. Surg. 2025, 87, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, S.; Frishman, W.H.; Aronow, W.S. Baxdrostat: An Aldosterone Synthase Inhibitor for the Treatment of Systemic Hypertension. Cardiol. Rev. 2025, 33, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flack, J.M.; Azizi, M.; Brown, J.M.; Dwyer, J.P.; Fronczek, J.; Jones, E.S.W.; Olsson, D.S.; Perl, S.; Shibata, H.; Wang, J.-G.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Baxdrostat in Uncontrolled and Resistant Hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 393, 1363–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapelli, M.; Rubbo, F.M.; Costantino, S.; Amelotti, N.; Agostoni, P. Pharmacological Therapy of HFrEF in 2025: Navigating New Advances and Old Unmet Needs in An Eternal Balance Between Progress and Perplexities. Card. Fail. Rev. 2025, 11, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, O.T.F.; Ahmed, Z.T.; Dairi, A.W.; Zain Al-Abeden, M.S.; Alkahlot, M.H.; Alkahlot, R.H.; Al Jowf, G.I.; Eijssen, L.M.T.; Haider, K.H. The Inconclusive Superiority Debate of Allogeneic versus Autologous MSCs in Treating Patients with HFrEF: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of RCTs. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalil, J.E.; Gabrielli, L.; Ocaranza, M.P.; MacNab, P.; Fernández, R.; Grassi, B.; Jofré, P.; Verdejo, H.; Acevedo, M.; Cordova, S.; et al. New Mechanisms to Prevent Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction Using Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonism (GLP-1 RA) in Metabolic Syndrome and in Type 2 Diabetes: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfioli, G.B.; Rodella, L.; Metra, M.; Vizzardi, E. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists as Promising Anti-Inflammatory Agents in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Heart Fail. Rev. 2025, 30, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunham, L.R.; Lonn, E.; Mehta, S.R. Dyslipidemia and the Current State of Cardiovascular Disease: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Effect of Lipid Lowering. Can. J. Cardiol. 2024, 40, S4–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basit, J.; Ahmed, M.; Singh, P.; Ahsan, A.; Zulfiqar, E.; Iqbal, J.; Fatima, M.; Upreti, P.; Hamza, M.; Alraies, M.C. Safety and Efficacy of Inclisiran in Hyperlipidemia: An Updated Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2025, 8, e70039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkas, F.; Ray, K. An Update on Inclisiran for the Treatment of Elevated LDL Cholesterol. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2024, 25, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revaiah, P.C.; Serruys, P.W.; Onuma, Y.; Andreini, D.; Budoff, M.J.; Sharif, F.; Chernofsky, A.; Vikarunnessa, S.; Wiethoff, A.J.; Yates, D.; et al. Design and Rationale of a Randomized Clinical Trial Assessing the Effect of Inclisiran on Atherosclerotic Plaque in Individuals without Previous Cardiovascular Event and without Flow- Limiting Lesions Identified in an in-Hospital Screening: The VICTORION-PLAQUE Primary Prevention Trial. Am. Heart J. 2026, 291, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholls, S.J.; Nelson, A.J.; Lincoff, A.M.; Brennan, D.; Ray, K.K.; Cho, L.; Menon, V.; Li, N.; Bloedon, L.; Nissen, S.E. Impact of Bempedoic Acid on Total Cardiovascular Events: A Prespecified Analysis of the CLEAR Outcomes Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2024, 9, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parhofer, K.G.; Aguiar, C.; Banach, M.; Drexel, H.; Gouni-Berthold, I.; Pérez de Isla, L.; Rietzschel, E.; Zambon, A.; Ray, K.K. Expert Opinion on the Integration of Combination Therapy into the Treatment Algorithm for the Management of Dyslipidaemia: The Integration of Ezetimibe and Bempedoic Acid May Enhance Goal Attainment. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2025, 11, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, Y.Y. Olezarsen: First Approval. Drugs 2025, 85, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroes, E.S.G.; Alexander, V.J.; Karwatowska-Prokopczuk, E.; Hegele, R.A.; Arca, M.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Soran, H.; Prohaska, T.A.; Xia, S.; Ginsberg, H.N.; et al. Olezarsen, Acute Pancreatitis, and Familial Chylomicronemia Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 1781–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegele, R.A. Inhibiting Angiopoietin-like Protein 3: Clear Skies or Clouds on the Horizon? Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 722–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudet, D.; Gonciarz, M.; Shen, X.; Leohr, J.K.; Beyer, T.P.; Day, J.W.; Mullins, G.R.; Zhen, E.Y.; Hartley, M.; Larouche, M.; et al. Targeting the Angiopoietin-like Protein 3/8 Complex with a Monoclonal Antibody in Patients with Mixed Hyperlipidemia: A Phase 1 Trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 2632–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghofrani, H.-A.; Gomberg-Maitland, M.; Zhao, L.; Grimminger, F. Mechanisms and Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2025, 22, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, J.; Wade, J.; Torres, A.; Hale, G.; Pham, H. Sotatercept: The First FDA-Approved Activin A Receptor IIA Inhibitor Used in the Management of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs Drugs Devices Interv. 2025, 25, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.C.; Furqan, M.; Tonelli, A.R.; Brady, D.; Levine, A.; Rosenzweig, E.B.; Frishman, W.H.; Aronow, W.S.; Lanier, G.M. Sotatercept: A New Era in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Cardiol. Rev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeper, M.M.; Gomberg-Maitland, M.; Badesch, D.B.; Gibbs, J.S.R.; Grünig, E.; Kopeć, G.; McLaughlin, V.V.; Meyer, G.; Olsson, K.M.; Preston, I.R.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of the Activin Signalling Inhibitor, Sotatercept, in a Pooled Analysis of PULSAR and STELLAR Studies. Eur. Respir. J. 2025, 65, 2401424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waxman, A.B.; Systrom, D.M.; Manimaran, S.; de Oliveira Pena, J.; Lu, J.; Rischard, F.P. SPECTRA Phase 2b Study: Impact of Sotatercept on Exercise Tolerance and Right Ventricular Function in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Circ. Heart Fail. 2024, 17, e011227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, D.H.; Lingvay, I.; Colhoun, H.M.; Deanfield, J.; Emerson, S.S.; Kahn, S.E.; Kushner, R.F.; Marso, S.; Plutzky, J.; Brown-Frandsen, K.; et al. Semaglutide Effects on Cardiovascular Outcomes in People With Overweight or Obesity (SELECT) Rationale and Design. Am. Heart J. 2020, 229, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, J.B.; Glover, L.; Soneji, S.; Granger, C.B.; O’Brien, E.; Pagidipati, N. Cardiovascular Event Reduction among a US Population Eligible for Semaglutide per the SELECT Trial. Am. Heart J. 2024, 276, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanna, M.G.; Doan, Q.V.; Fabricatore, A.; Faurby, M.; Henry, A.D.; Houshmand-Oeregaard, A.; Levine, A.; Navar, A.M.; Scassellati Sforzolini, T.; Toliver, J.C. Population-Level Impact of Semaglutide 2.4 Mg in Patients with Obesity or Overweight and Cardiovascular Disease: A Modelling Study Based on the SELECT Trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 3442–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llongueras-Espí, P.; García-Romero, E.; Comín-Colet, J.; González-Costello, J. Role of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists (GLP-1RAs) in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulsin, G.S.; Graham-Brown, M.P.M.; Squire, I.B.; Davies, M.J.; McCann, G.P. Benefits of Sodium Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors across the Spectrum of Cardiovascular Diseases. Heart Br. Card. Soc. 2022, 108, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Ferreira, J.P.; Bocchi, E.; Böhm, M.; Brunner-La Rocca, H.-P.; Choi, D.-J.; Chopra, V.; Chuquiure-Valenzuela, E.; et al. Empagliflozin in Heart Failure with a Preserved Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1451–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasoni, D.; Fonarow, G.C.; Adamo, M.; Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Coats, A.J.S.; Filippatos, G.; Greene, S.J.; McDonagh, T.A.; Ponikowski, P.; et al. Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporter 2 Inhibitors as an Early, First-Line Therapy in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2022, 24, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrington, W.G.; Staplin, N.; Wanner, C.; Green, J.B.; Hauske, S.J.; Emberson, J.R.; Preiss, D.; Judge, P.; Mayne, K.J.; et al.; The EMPA-KIDNEY Collaborative Group Empagliflozin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usman, M.S.; Siddiqi, T.J.; Anker, S.D.; Bakris, G.L.; Bhatt, D.L.; Filippatos, G.; Fonarow, G.C.; Greene, S.J.; Januzzi, J.L.; Khan, M.S.; et al. Effect of SGLT2 Inhibitors on Cardiovascular Outcomes Across Various Patient Populations. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 81, 2377–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frąk, W.; Hajdys, J.; Radzioch, E.; Szlagor, M.; Młynarska, E.; Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B. Cardiovascular Diseases: Therapeutic Potential of SGLT-2 Inhibitors. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, L.R.; Ho, C.Y.; Elliott, P.M. Genetics of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Established and Emerging Implications for Clinical Practice. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 2727–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy Kalluru, P.K.; Siddenthi, S.M.; Valisekka, S.S.; Suddapalli, S.K.; Juturu, U.T.; Chagam Reddy, S.; Matturi, A.; Reddy Yartha, S.G.; Kuchi, D.; Batchu, V.R.; et al. A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials on Mavacamten in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Heart Int. 2025, 19, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, M.T.; Olivotto, I.; Elliott, P.M.; Saberi, S.; Owens, A.T.; Maurer, M.S.; Masri, A.; Sehnert, A.J.; Edelberg, J.M.; Chen, Y.-M.; et al. Effects of Mavacamten on Measures of Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing Beyond Peak Oxygen Consumption: A Secondary Analysis of the EXPLORER-HCM Randomized Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2023, 8, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, M.Y.; Owens, A.; Wolski, K.; Geske, J.B.; Saberi, S.; Wang, A.; Sherrid, M.; Cremer, P.C.; Lakdawala, N.K.; Tower-Rader, A.; et al. Mavacamten in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Referred for Septal Reduction: Week 56 Results From the VALOR-HCM Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2023, 8, 968–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, S.; Abraham, T.P.; Choudhury, L.; Barriales-Villa, R.; Elliott, P.M.; Nassif, M.E.; Oreziak, A.; Owens, A.T.; Tower-Rader, A.; Rader, F.; et al. Aficamten Treatment for Symptomatic Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: 48-Week Results From FOREST-HCM. JACC Heart Fail. 2025, 13, 102496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Divanji, P.; Griffith, A.; Sukhun, R.; Cheplo, K.; Li, J.; German, P. Pharmacokinetics, Disposition, and Biotransformation of the Cardiac Myosin Inhibitor Aficamten in Humans. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2024, 12, e70006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.; Wang, A.; Naidu, S.S.; Frishman, W.H.; Aronow, W.S. Aficamten-A Second in Class Cardiac Myosin Inhibitor for Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Cardiol. Rev. 2025, 33, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maron, M.S.; Masri, A.; Nassif, M.E.; Barriales-Villa, R.; Arad, M.; Cardim, N.; Choudhury, L.; Claggett, B.; Coats, C.J.; Düngen, H.-D.; et al. Aficamten for Symptomatic Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 1849–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madero, M.; Chertow, G.M.; Mark, P.B. SGLT2 Inhibitor Use in Chronic Kidney Disease: Supporting Cardiovascular, Kidney, and Metabolic Health. Kidney Med. 2024, 6, 100851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalibala, J.; Pechère-Bertschi, A.; Desmeules, J. Gender Differences in Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy-the Example of Hypertension: A Mini Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regitz-Zagrosek, V.; Kararigas, G. Mechanistic Pathways of Sex Differences in Cardiovascular Disease. Physiol. Rev. 2017, 97, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucker, I.; Prendergast, B.J. Sex Differences in Pharmacokinetics Predict Adverse Drug Reactions in Women. Biol. Sex Differ. 2020, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varrassi, G.; Pergolizzi, J.V.; Farì, G.; Al-Alwany, A.A.; Leoni, M.L. Advancements in cardiovascular pharmacology. Adv. Health Res. 2025, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alla, S.S.M.; Shah, D.J.; Meyur, S.; Agarwal, P.; Alla, D.; Moraboina, S.L.; Ghadvaje, G.V.; Bayeh, R.G.; Malireddi, A.; Shajan, T.; et al. Small Interfering RNA (siRNA) in Dyslipidemia: A Systematic Review on Safety and Efficacy of siRNA. J. Exp. Pharmacol. 2025, 17, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, I.; Eells, K.; Hudson, I. A Comparison of Currently Approved Small Interfering RNA (siRNA) Medications to Alternative Treatments by Costs, Indications, and Medicaid Coverage. Pharm. Basel Switz. 2024, 12, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, Q.D. Gene Editing Therapy as a Therapeutic Approach for Cardiovascular Diseases in Animal Models: A Scoping Review. PloS One 2025, 20, e0325330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Du, Z.; Chen, R.; Liu, X.; Li, D. Gene- and Cell-Based Therapy in Cardiovascular Diseases. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2025, 86, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epelde, F. The Role of the Gut Microbiota in Heart Failure: Pathophysiological Insights and Future Perspectives. Medicina (Mex.) 2025, 61, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matacchione, G.; Piacenza, F.; Pimpini, L.; Rosati, Y.; Marcozzi, S. The Role of the Gut Microbiota in the Onset and Progression of Heart Failure: Insights into Epigenetic Mechanisms and Aging. Clin. Epigenetics 2024, 16, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yang, Y.; Chen, W.; Hu, J.; Jin, Z.; Wu, C.; Li, Y. Role of Gut Microbiota and Derived Metabolites in Cardiovascular Diseases. iScience 2025, 28, 113247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaritei, O.; Mierlan, O.L.; Dinu, C.A.; Chiscop, I.; Matei, M.N.; Gutu, C.; Gurau, G. TMAO and Cardiovascular Disease: Exploring Its Potential as a Biomarker. Medicina (Mex.) 2025, 61, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantino-Jonapa, L.A.; Espinoza-Palacios, Y.; Escalona-Montaño, A.R.; Hernández-Ruiz, P.; Amezcua-Guerra, L.M.; Amedei, A.; Aguirre-García, M.M. Contribution of Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) to Chronic Inflammatory and Degenerative Diseases. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; He, X.; Fang, Q.; Yin, X. Gut Microbe-Generated Metabolite Trimethylamine-N-Oxide and Ischemic Stroke. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Gregory, J.C.; Org, E.; Buffa, J.A.; Gupta, N.; Wang, Z.; Li, L.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Mehrabian, M.; et al. Gut Microbial Metabolite TMAO Enhances Platelet Hyperreactivity and Thrombosis Risk. Cell 2016, 165, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Therapeutic Area | Drug/Agent | Mechanism of Action | Key Clinical Findings | FDA Status/Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM) | Acoramidis (Attruby™) | Near-complete TTR stabilizer preventing misfolding and amyloid fibril deposition | ATTRibute-CM: Significant reductions in CV death and CV hospitalizations; sustained improvements in functional capacity (6MWD) and quality of life | FDA approved late 2024 for wild-type and hereditary ATTR-CM |

| Vutrisiran (Amvuttra™) | Subcutaneous siRNA suppressing hepatic TTR mRNA production (>80% reduction) | HELIOS-B: Clinically meaningful reductions in all-cause and CV mortality, fewer hospitalizations vs placebo; quarterly dosing | FDA indication expanded 2025 to include ATTR-CM | |

| Lipoprotein(a) Targeting | Lepodisiran | Small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting apolipoprotein(a) mRNA | ALPINE trial: ~94% sustained Lp(a) reduction at 6 months; well-tolerated with infrequent (quarterly to biannual) dosing | Phase 2 completed; Phase 3 ongoing |

| Pelacarsen | Antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) targeting apolipoprotein(a) | Lp(a)HORIZON Phase 3 outcomes trial evaluating MACE reduction in patients with elevated Lp(a) and established CVD | Phase 3 ongoing (>7,000 patients enrolled) | |

| RNA-Based Lipid Therapies | Inclisiran (Leqvio®) | siRNA targeting hepatic PCSK9 mRNA; induces sustained gene silencing via RNA interference pathway | ORION-10/11: 50-52% LDL-C reduction sustained with twice-yearly dosing; ORION-3: benefit maintained 4+ years; no immune-mediated reactions | FDA approved 2021; 2024 label update as potential first-line monotherapy |

| Olezarsen (Tryngolza™) | ASO targeting apolipoprotein C-III (apoC-III) to enhance triglyceride clearance | BALANCE trial: 50-70% triglyceride reduction; prevents recurrent pancreatitis in familial chylomicronemia syndrome | FDA approved 2024 for FCS | |

| Evinacumab (Evkeeza™) | Monoclonal antibody inhibiting angiopoietin-like 3 (ANGPTL3) | Reductions in LDL-C, triglycerides, and Lp(a) in refractory homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia | FDA approved for homozygous FH | |

| Gene Editing | VERVE-101 | CRISPR base editor targeting hepatic PCSK9 gene; delivered via GalNAc-LNP for permanent gene modification | First-in-human trial (Phase 1b): Single-dose administration; preliminary evidence of PCSK9 reduction and LDL-C lowering in heterozygous FH | Phase 1b ongoing; first patient dosed 2022 |

| Resistant Hypertension | Zilebesiran | siRNA targeting hepatic angiotensinogen mRNA; upstream RAAS modulation | KARDIA-1: Sustained BP reductions (10-15 mmHg SBP) with quarterly or biannual dosing; benefits maintained 6+ months | Phase 2 completed; Phase 3 in development |

| Baxdrostat | Highly selective aldosterone synthase (CYP11B2) inhibitor | BaxHTN Phase 3: 9-10 mmHg placebo-adjusted SBP reduction; 36% achieved target BP goal vs 18% placebo; favorable safety | Phase 3 completed 2024; regulatory submissions expected 2025 | |

| Aprocitentan (Tryvio™) | Dual endothelin A/B receptor antagonist | PRECISION trial: 8 mmHg SBP reduction in resistant hypertension; well-tolerated | FDA approved 2024 | |

| Anti-Inflammatory Therapy | Canakinumab (Ilaris™) | Monoclonal antibody targeting interleukin-1β (IL-1β); selectively inhibits inflammatory pathway | CANTOS: 15% reduction in CV death/MI/stroke (150mg dose); 25% MACE reduction in hsCRP <2 mg/L responders; validates inflammatory hypothesis | Not approved for CV indication (cost/infection concerns) |

| Colchicine (generic) | Microtubule polymerization inhibitor; disrupts neutrophil chemotaxis and NLRP3 inflammasome activation | COLCOT: 23% MACE reduction post-MI; LoDoCo2: 31% reduction in CV death/MI/stroke/revascularization in chronic CAD; inexpensive, oral | FDA approved for gout/pericarditis; used off-label for CV prevention | |

| Heart Failure | Vericiguat (Verquvo™) | Oral soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) stimulator; restores NO-cGMP signaling independent of nitric oxide | VICTORIA: 10% reduction in CV death/HF hospitalization in high-risk HFrEF with recent decompensation; greatest benefit with NT-proBNP >4,000 | FDA approved 2021 as add-on therapy for chronic HFrEF |

| Sacubitril-valsartan (Entresto™) | Angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI); dual natriuretic peptide enhancement + angiotensin blockade | PARADIGM-HF: 20% reduction in CV death/HF hospitalization vs enalapril in HFrEF; evolution from omapatrilat avoiding angioedema | FDA approved; guideline-recommended first-line for HFrEF | |

| SGLT2 Inhibitors (dapagliflozin, empagliflozin) | Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibition; mechanisms include osmotic diuresis, metabolic shift, anti-fibrotic effects | Meta-analyses: 25-30% reduction in HF hospitalization across HFrEF and HFpEF; 12-14% CV death reduction; benefits within 30 days regardless of diabetes | FDA approved for HFrEF and HFpEF regardless of diabetes status | |

| Baroreflex Activation Therapy (BAT) | Implantable device delivering electrical stimulation to carotid baroreceptors; restores autonomic balance | BeAT-HF: Improved quality of life, 6-minute walk distance, and NT-proBNP in advanced HFrEF with persistent symptoms despite GDMT | Investigational device; ongoing trials | |

| Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension | Sotatercept (Winrevair™) | Activin receptor type IIA-Fc fusion protein; modulates TGF-β superfamily to promote vascular remodeling reversal | STELLAR: 40.8m improved 6MWD at 24 weeks; 84% reduction in clinical worsening events; first disease-modifying therapy targeting vascular remodeling | FDA approved March 2024 as add-on therapy for WHO Group 1 PAH |

| Cardiometabolic/Obesity | Semaglutide (Wegovy™) | GLP-1 receptor agonist; pleiotropic CV effects beyond glucose/weight control | SELECT: 20% relative MACE reduction (HR 0.80) in overweight/obesity without diabetes; first weight-loss medication with CV risk reduction indication | FDA indication 2024 for CV risk reduction |

| Tirzepatide (Zepbound™) | Dual GLP-1/GIP receptor agonist | Superior weight loss vs semaglutide (~22% at 72 weeks); CV outcomes trial (SURPASS-CVOT) ongoing | FDA approved for obesity; CV indication pending | |

| Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy | Mavacamten (Camzyos™) | First-in-class cardiac myosin inhibitor; reduces hypercontractility underlying LVOT obstruction | EXPLORER-HCM: Improved exercise capacity, NYHA class, LVOT gradient; first pharmacologic alternative to septal reduction therapy | FDA approved 2022 for symptomatic obstructive HCM |

| Aficamten | Next-generation cardiac myosin inhibitor; shorter half-life allows faster dose titration | SEQUOIA-HCM Phase 3: Improved LVOT gradients, exercise capacity, symptom burden; potentially favorable PK profile vs mavacamten | Under FDA review; approval anticipated 2025 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).