Submitted:

09 December 2025

Posted:

10 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

Data Analyses

Dietary Assessment

Dietary Indices

Environmental Impact Indicators

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Socio-Demographic, Lifestyle, and Dietary Factors

Food Group Intake and Environmental Impact Changes

The Association Between Environmental Sustainability and Students’ Characteristics and Lifestyle

| All | Krešić et al., 2009 |

Pavičić Žeželj et al., 2018 |

Kenđel Jovanović et al., 2025 |

p-value* | |||||

| mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | ||

| Nuts and peanuts (g/day) | 4.90 | 12.72 | 3.25 | 5.12 | 2.32 | 2.81 | 22.23 | 27.21 | <0.001 |

| Carbon footprint (g CO2 eqv.) | 5.84 | 13.49 | 3.24 | 5.10 | 2.76 | 3.09 | 23.77 | 29.39 | <0.001 |

| Water footprint (m3) | 35.86 | 90.55 | 23.36 | 36.76 | 22.98 | 2.76 | 158.72 | 194.17 | <0.001 |

| Ecological footprint (m2*year) | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 3.33 | 2.98 | 0.20 | 0.25 | <0.001 |

| Legumes (g/day) | 32.35 | 43.06 | 18.21 | 18.92 | 53.41 | 59.95 | 53.02 | 53.19 | <0.001 |

| Carbon footprint (g CO2 eqv.) | 12.93 | 16.08 | 14.23 | 18.27 | 11.06 | 12.35 | 10.92 | 10.96 | <0.001 |

| Water footprint (m3) | 5.84 | 9.67 | 1.76 | 2.07 | 5.93 | 7.32 | 5.78 | 6.82 | <0.001 |

| Ecological footprint (m2*year) | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Fruits (g/day) | 276.67 | 222.32 | 369.40 | 224.04 | 122.75 | 110.22 | 173.29 | 156.38 | <0.001 |

| Carbon footprint (g CO2 eqv.) | 412.49 | 451.75 | 650.94 | 446.10 | 53.39 | 46.66 | 72.06 | 63.55 | <0.001 |

| Water footprint (m3) | 61.63 | 66.98 | 39.58 | 35.08 | 84.71 | 75.99 | 113.63 | 102.80 | <0.001 |

| Ecological footprint (m2*year) | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.07 | <0.001 |

| Vegetables (g/day) | 228.67 | 165.33 | 278.68 | 174.64 | 125.14 | 94.23 | 214.60 | 132.54 | <0.001 |

| Carbon footprint (g CO2 eqv.) | 289.24 | 238.82 | 388.23 | 245.30 | 113.70 | 94.32 | 201.69 | 163.35 | <0.001 |

| Water footprint (m3) | 49.71 | 29.86 | 53.49 | 27.84 | 36.77 | 28.19 | 59.08 | 33.56 | <0.001 |

| Ecological footprint (m2*year) | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.11 | <0.001 |

| Whole grains (g/day) | 27.21 | 33.20 | 32.35 | 37.29 | 15.04 | 22.95 | 28.86 | 23.71 | <0.001 |

| Carbon footprint (g CO2 eqv.) | 58.59 | 59.17 | 51.66 | 55.34 | 65.54 | 61.53 | 75.57 | 65.77 | <0.001 |

| Water footprint (m3) | 51.73 | 52.17 | 46.02 | 50.46 | 57.27 | 51.99 | 66.09 | 56.18 | <0.001 |

| Ecological footprint (m2*year) | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.003 |

| Eggs (g/day) | 22.61 | 27.32 | 15.42 | 18.14 | 29.84 | 32.34 | 40.18 | 37.08 | <0.001 |

| Carbon footprint (g CO2 eqv.) | 83.07 | 100.50 | 56.71 | 66.71 | 109.42 | 119.03 | 147.78 | 136.37 | <0.001 |

| Water footprint (m3) | 94.28 | 114.07 | 64.36 | 75.71 | 124.19 | 135.10 | 167.73 | 154.79 | <0.001 |

| Ecological footprint (m2*year) | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.24 | <0.001 |

| Fish (g/day) | 47.07 | 43.02 | 49.88 | 40.94 | 40.75 | 45.82 | 47.34 | 45.05 | 0.001 |

| Carbon footprint (g CO2 eqv.) | 228.49 | 278.41 | 346.37 | 305.38 | 45.58 | 51.63 | 71.19 | 63.00 | <0.001 |

| Water footprint (m3) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | <0.001 |

| Ecological footprint (m2*year) | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | <0.001 |

| Tubers and potatoes (g/day) | 107.74 | 79.97 | 104.14 | 64.98 | 95.52 | 83.13 | 148.75 | 114.59 | <0.001 |

| Carbon footprint (g CO2 eqv.) | 47.69 | 37.20 | 57.93 | 38.72 | 25.93 | 22.56 | 45.93 | 34.84 | <0.001 |

| Water footprint (m3) | 57.91 | 47.73 | 48.51 | 31.44 | 59.96 | 52.17 | 95.92 | 73.07 | <0.001 |

| Ecological footprint (m2*year) | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Milk and dairy (g/day) | 390.25 | 224.13 | 404.55 | 222.66 | 358.90 | 188.87 | 389.78 | 283.52 | 0.002 |

| Carbon footprint (g CO2 eqv.) | 808.52 | 499.94 | 844.45 | 409.66 | 689.08 | 382.10 | 889.92 | 889.88 | <0.001 |

| Water footprint (m3) | 544.67 | 347.46 | 542.28 | 298.42 | 498.47 | 271.11 | 649.20 | 587.54 | <0.001 |

| Ecological footprint (m2*year) | 0.75 | 0.56 | 0.74 | 0.39 | 0.65 | 0.39 | 0.96 | 1.12 | <0.001 |

| Vegetable oils (g/day) | 20.33 | 18.80 | 12.65 | 6.57 | 26.83 | 23.51 | 41.57 | 23.31 | <0.001 |

| Carbon footprint (g CO2 eqv.) | 15.50 | 12.51 | 15.58 | 9.91 | 10.13 | 8.93 | 26.05 | 20.17 | <0.001 |

| Water footprint (m3) | 74.33 | 71.31 | 90.41 | 49.38 | 42.37 | 1.97 | 148.29 | 100.81 | <0.001 |

| Ecological footprint (m2*year) | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.25 | 0.14 | <0.001 |

| Red meat and products (g/day) | 95.69 | 87.45 | 95.99 | 61.40 | 64.26 | 79.77 | 158.19 | 147.83 | <0.001 |

| Carbon footprint (g CO2 eqv.) | 2574.74 | 1874.21 | 2736.51 | 1772.55 | 2243.22 | 1912.85 | 2522.32 | 2137.84 | <0.001 |

| Water footprint (m3) | 867.16 | 878.09 | 637.85 | 395.24 | 908.74 | 858.13 | 1811.52 | 1574.89 | <0.001 |

| Ecological footprint (m2*year) | 3.70 | 3.10 | 3.15 | 1.69 | 3.63 | 3.33 | 6.34 | 5.37 | <0.001 |

| Poultry and substitutes (g/day) | 62.54 | 53.04 | 71.03 | 51.33 | 31.79 | 37.29 | 86.88 | 60.77 | <0.001 |

| Carbon footprint (g CO2 eqv.) | 360.56 | 326.43 | 295.75 | 205.00 | 319.93 | 217.67 | 733.91 | 596.85 | <0.001 |

| Water footprint (m3) | 267.05 | 272.11 | 157.41 | 118.11 | 344.57 | 234.44 | 601.49 | 453.11 | <0.001 |

| Ecological footprint (m2*year) | 1.02 | 1.00 | 0.65 | 0.47 | 1.24 | 0.85 | 2.23 | 1.70 | <0.001 |

| Animal fats (g/day) | 11.65 | 5.58 | 11.43 | 4.13 | 11.55 | 6.10 | 12.86 | 8.98 | 0.002 |

| Carbon footprint (g CO2 eqv.) | 2.06 | 2.74 | 2.38 | 3.11 | 1.53 | 1.30 | 1.67 | 2.86 | <0.001 |

| Water footprint (m3) | 1.45 | 2.14 | 1.86 | 2.43 | 0.62 | 0.58 | 1.30 | 2.23 | <0.001 |

| Ecological footprint (m2*year) | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Added sugars (g/day) | 22.92 | 23.27 | 22.48 | 15.87 | 12.28 | 11.89 | 46.48 | 43.32 | <0.001 |

| Carbon footprint (g CO2 eqv.) | 251.85 | 217.66 | 299.07 | 237.18 | 207.80 | 177.02 | 129.49 | 106.93 | <0.001 |

| Water footprint (m3) | 237.95 | 268.69 | 141.80 | 134.01 | 389.16 | 338.80 | 362.18 | 355.67 | <0.001 |

| Ecological footprint (m2*year) | 0.59 | 0.73 | 0.34 | 0.24 | 1.20 | 1.11 | 0.51 | 0.46 | <0.001 |

| 2009 study (Krešić et al.) | 2018 study (Pavičić Žeželj et al.) | 2025 Kenđel Jovanović et al. | ||||||||||

| β | 95% CI | p-value | β | 95% CI | p-value | β | 95% CI | p-value | ||||

| Age (1 ≤ 21 years; 2 > 22 years) | -37.97 | 84.78 | -160.72 | 0.544 | -13.64 | 190.91 | -218.19 | 0.896 | -99.91 | 238.73 | -438.55 | 0.564 |

| Gender (1 men; 2 women) | -462.65 | -127.49 | -797.82 | 0.007 | -987.98 | -511.38 | -1464.57 | <0.001 | -1778.82 | -940.44 | -2617.20 | <0.001 |

| Nutrition status (1 underweight; 2 normal weight; 3 overweight; 4 obesity) | -144.37 | 164.29 | -453.02 | 0.360 | 253.84 | 643.12 | -135.43 | 0.202 | -223.13 | 432.07 | -878.33 | 0.505 |

| Physical activity level (1 low; 2 moderate; 3 high) | 84.81 | 280.65 | -111.03 | 0.396 | 116.66 | 359.37 | -126.04 | 0.347 | -174.58 | 487.79 | -836.95 | 0.606 |

| Smoking habits (1 no; 2 yes) | 50.79 | 337.65 | -236.07 | 0.729 | 266.10 | 673.43 | -141.23 | 0.201 | -84.16 | 831.91 | -1000.23 | 0.857 |

| Study level (1 undergraduate; 2 graduate) | 120.15 | 559.91 | -319.62 | 0.592 | -448.82 | 464.66 | -1362.29 | 0.336 | -394.48 | 1106.39 | -1895.35 | 0.607 |

| PHDI quartiles (1 Q1; 2Q2; 3Q3; 4 Q4) | 83.27 | 222.09 | -55.56 | 0.240 | 193.39 | 372.11 | 14.67 | 0.034 | -568.02 | -130.05 | -1005.99 | 0.012 |

| MDS adherence (1 low; 2 moderate; 3 high) | 444.31 | 700.23 | 188.38 | 0.001 | 194.39 | 531.89 | -143.12 | 0.260 | 270.95 | 994.99 | -453.08 | 0.464 |

| DII inflammation potential (1 proinflammatory; 2 anti-inflammatory) |

1906.08 | 2208.89 | 1603.26 | <0.001 | 2106.11 | 2845.46 | 1366.76 | <0.001 | 3271.46 | 4340.60 | 2202.32 | <0.001 |

| 2009 study (Krešić et al.) | 2018 study (Pavičić Žeželj et al.) | 2025 Kenđel Jovanović et al. | ||||||||||

| β | 95% CI | p-value | β | 95% CI | p-value | β | 95% CI | p-value | ||||

| Age (1 ≤ 21 years; 2 > 22 years) | -20.47 | –61.07 | 20.13 | 0.323 | -28.38 | 86.40 | -143.17 | 0.628 | -58.06 | 194.91 | -311.02 | 0.653 |

| Gender (1 men; 2 women) | -141.97 | –252.82 | –31.12 | 0.012 | -610.70 | -343.26 | -878.14 | <0.001 | -1302.98 | -676.71 | -1929.25 | <0.001 |

| Nutrition status (1 underweight; 2 normal weight; 3 overweight; 4 obesity) | -17.63 | –119.71 | 84.45 | 0.735 | 110.01 | 328.45 | -108.43 | 0.324 | -146.26 | 343.18 | -635.70 | 0.559 |

| Physical activity level (1 low; 2 moderate; 3 high) | 6.74 | –58.03 | 71.50 | 0.839 | 39.42 | 175.61 | -96.78 | 0.571 | -58.27 | 436.52 | -553.06 | 0.818 |

| Smoking habits (1 no; 2 yes) | 127.80 | 32.93 | 222.66 | 0.008 | 89.12 | 317.69 | -139.45 | 0.445 | -176.56 | 507.75 | -860.88 | 0.614 |

| Study level (1 undergraduate; 2 graduate) | -61.05 | –206.50 | 84.40 | 0.411 | -148.96 | 363.63 | -661.56 | 0.569 | -369.00 | 752.16 | -1490.16 | 0.520 |

| PHDI quartiles (1 Q1; 2Q2; 3Q3; 4 Q4) | -132.05 | –177.97 | –86.13 | <0.001 | 57.53 | 157.82 | -42.76 | 0.261 | -427.29 | -100.13 | -754.45 | 0.011 |

| MDS adherence (1 low; 2 moderate; 3 high) | 148.85 | 64.20 | 233.50 | 0.001 | 122.89 | 312.28 | -66.50 | 0.204 | 311.26 | 852.12 | -229.61 | 0.261 |

| DII inflammation potential (1 proinflammatory; 2 anti-inflammatory) | 525.94 | 425.78 | 626.10 | <0.001 | 1206.90 | 1621.79 | 792.02 | <0.001 | 2564.66 | 3363.31 | 1766.00 | <0.001 |

| 2009 study (Krešić et al.) | 2018 study (Pavičić Žeželj et al.) | 2025Kenđel Jovanović et al. | ||||||||||

| β | 95% CI | p-value | β | 95% CI | p-value | β | 95% CI | p-value | ||||

| Age (1 ≤ 21 years; 2 > 22 years) | -0.04 | 0.08 | -0.16 | 0.520 | -0.07 | 0.31 | -0.46 | 0.702 | -0.18 | 0.37 | -0.74 | 0.519 |

| Gender (1 men; 2 women) | -0.66 | -0.34 | -0.98 | <0.001 | -2.16 | -1.27 | -3.05 | 0.000 | -3.39 | -2.02 | -4.76 | <0.001 |

| Nutrition status (1 underweight; 2 normal weight; 3 overweight; 4 obesity) | -0.33 | -0.04 | -0.63 | 0.027 | 0.50 | 1.23 | -0.23 | 0.179 | 0.08 | 1.15 | -0.99 | 0.885 |

| Physical activity level (1 low; 2 moderate; 3 high) | 0.05 | 0.24 | -0.13 | 0.580 | 0.23 | 0.68 | -0.23 | 0.329 | -0.31 | 0.77 | -1.39 | 0.576 |

| Smoking habits (1 no; 2 yes) | 0.10 | 0.37 | -0.18 | 0.489 | 0.46 | 1.22 | -0.30 | 0.237 | -1.82 | -0.33 | -3.32 | 0.018 |

| Study level (1 undergraduate; 2 graduate) | -0.05 | 0.37 | -0.47 | 0.822 | -0.84 | 0.87 | -2.54 | 0.336 | -0.74 | 1.71 | -3.19 | 0.554 |

| PHDI quartiles (1 Q1; 2Q2; 3Q3; 4 Q4) | -0.29 | -0.16 | -0.42 | <0.001 | 0.15 | 0.49 | -0.18 | 0.368 | -0.87 | -0.15 | -1.58 | 0.018 |

| MDS adherence (1 low; 2 moderate; 3 high) | 0.53 | 0.77 | 0.28 | <0.001 | 0.38 | 1.01 | -0.25 | 0.243 | 1.05 | 2.24 | -0.13 | 0.082 |

| DII inflammation potential (1 proinflammatory; 2 anti-inflammatory) | 1.72 | 2.01 | 1.43 | <0.001 | 3.51 | 4.89 | 2.13 | <0.001 | 7.36 | 9.10 | 5.61 | <0.001 |

4. Discussion

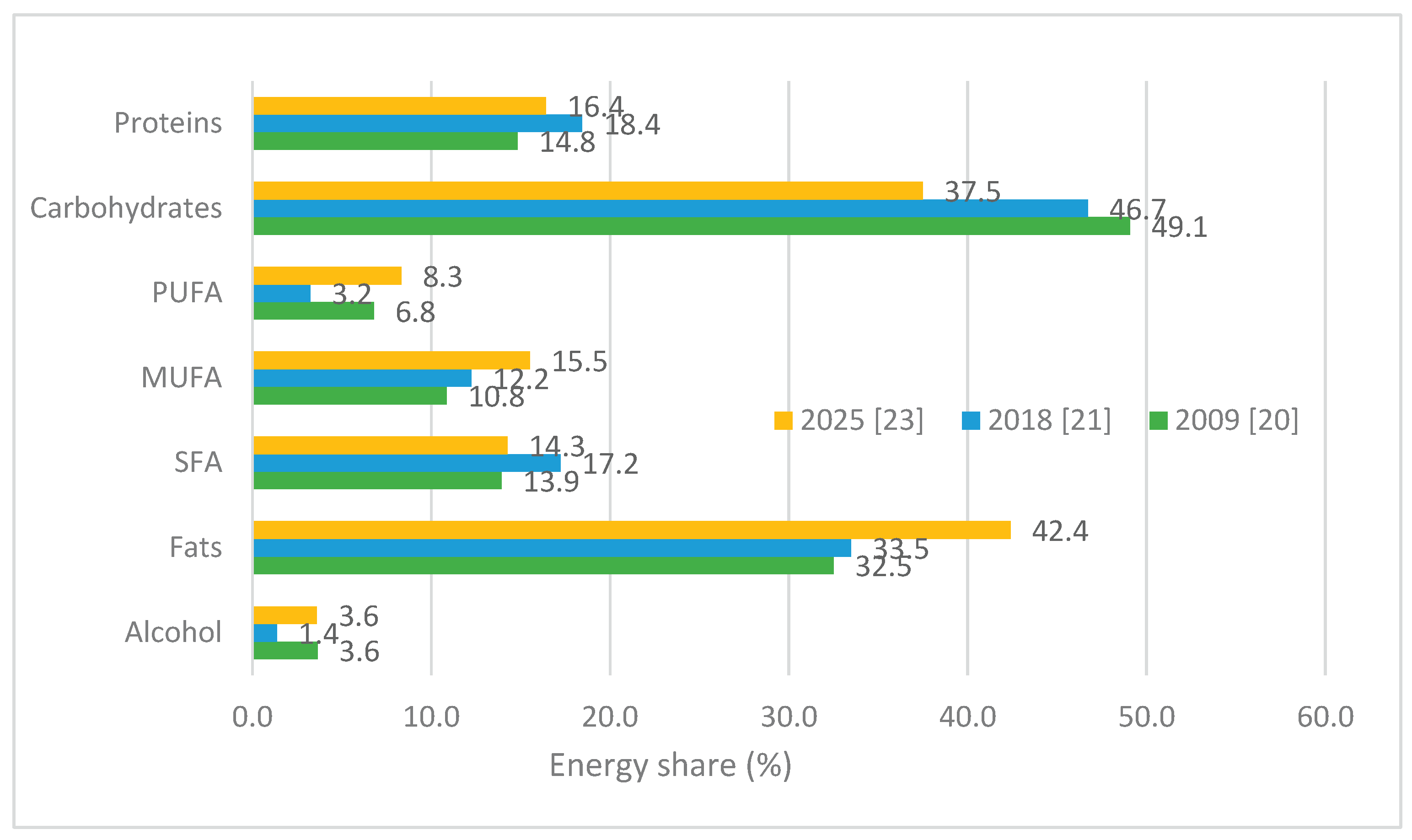

Change in Dietary Patterns/Nutrition Transition

Environmental Impact of the Diet

Implications for Policy and Future Research

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FFQ | Food Frequency Questionnaire |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| PHDI | Planetary Health Diet Index |

| MDS | Mediterranean Diet Score |

| DII | Dietary Inflammatory Index |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

References

- Clark, M.A.; Springmann, M.; Hill, J.; Tilman, D. Multiple health and environmental impacts of foods. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2019, 116(46), 23357–23362. [CrossRef]

- Fernqvist, F.; Spendrup, S.; Tellström, R. Understanding food choice: A systematic review of reviews. Heliyon 2024, 10(12), e32492. Published 2024 Jun 5. [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Angell, S.Y.; Lang, T.; Rivera, J.A. Role of government policy in nutrition—barriers to and opportunities for healthier eating. BMJ 2018, 361, k2426. Published 2018 Jun 13. [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M.; Ng, S.W. The nutrition transition to a stage of high obesity and noncommunicable disease prevalence dominated by ultra-processed foods is not inevitable. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23(1), e13366. [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, K.; Steffen, W.; Lucht, W.; et al. Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9(37), eadh2458. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, R.F.; Garcia, L.; Dagless, S.; et al. The emerging syndemic of climate change and non-communicable diseases. Lancet Planet. Health 2024, 8(7), e430–e431. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO); Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Sustainable healthy diets: guiding principles. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241516648 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Norwood, P.; Cleland, E.; McNamee, P. Exploring attitudes towards healthy and sustainable diets: A Q-methodology study. Cleaner Responsible Consumption 2025, 18, 100308.

- Swinburn, B.A.; Kraak, V.I.; Allender, S.; et al. The Global Syndemic of Obesity, Undernutrition, and Climate Change: The Lancet Commission report. Lancet 2019, 393(10173), 791–846. [CrossRef]

- Gulis, G.; Zidkova, R.; Meier, Z. Changes in disease burden and epidemiological transitions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15(1), 8961. Published 2025 Mar 15. [CrossRef]

- Deksne, J.; Lonska, J.; Litavniece, L.; Tambovceva, T. Shaping sustainability through food consumption: A conceptual perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17(15), 7138. [CrossRef]

- Biganzoli, F.; Caldeira, C.; Dias, J.; De Laurentiis, V.; Leite, J.; Wollgast, J.; Sala, S. Towards healthy and sustainable diets: Understanding food consumption trends in the EU. Foods 2025, 14(16), 2798. [CrossRef]

- Raghoebar, S.; Mesch, A.; Gulikers, J.; Winkens, L.H.H.; Wesselink, R.; Haveman-Nies, A. Experts’ perceptions on motivators and barriers of healthy and sustainable dietary behaviors among adolescents: The SWITCH project. Appetite 2024, 194, 107196. [CrossRef]

- Jurado-Gonzalez, P.; López-Toledo, S.; Bach-Faig, A.; Medina, F.-X. Barriers and enablers of healthy eating among university students in Oaxaca de Juarez: A mixed-methods study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1263. [CrossRef]

- Almoraie, N.M.; Alothmani, N.M.; Alomari, W.D.; Al-Amoudi, A.H. Addressing nutritional issues and eating behaviours among university students: A narrative review. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2025, 38, 53–68. [CrossRef]

- Elliott, P.S.; Devine, L.D.; Gibney, E.R.; O'Sullivan, A.M. What factors influence sustainable and healthy diet consumption? A review and synthesis of literature within the university setting and beyond. Nutr. Res. 2024, 126, 23–45. [CrossRef]

- Šatalić, Z.; Colić Barić, I.; Keser, I.; Marić, B. Evaluation of diet quality with the Mediterranean dietary quality index in university students. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2004, 55(8), 589–595.

- Šatalić, Z.; Barić, I.C.; Keser, I. Diet quality in Croatian university students: Energy, macronutrient and micronutrient intakes according to gender. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2007, 58(5), 398–410. [CrossRef]

- Kresić, G.; Kendel Jovanović, G.; Pavicić Zezel, S.; Cvijanović, O.; Ivezić, G. The effect of nutrition knowledge on dietary intake among Croatian university students. Coll. Antropol. 2009, 33(4), 1047–1056. Available online: https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/78762.

- Pavičić Žeželj, S.; Dragaš Zubalj, N.; Fantina, D.; Krešić, G.; Kenđel Jovanović, G. Adherence to Mediterranean diet in University of Rijeka students. Paediatria Croatica 2019, 63(1), 31. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, D.; Rešetar, J.; Czlapka-Matyasik, M.; et al. Changes in diet quality and its association with students' mental state during two COVID-19 lockdowns in Croatia. Nutr. Health 2024, 30(4), 797–806. [CrossRef]

- Kenđel Jovanović, G.; Krešić, G.; Dujmić, E.; Pavičić Žeželj, S. Adherence to the Planetary Health Diet and its association with diet quality and environmental outcomes in Croatian university students: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients 2025, 17(11), 1850. [CrossRef]

- Vujačić, V.; Podovšovnik, E.; Planinc, S.; Krešić, G.; Kukanja, M. Bridging knowledge and adherence: A cross-national study of the Mediterranean diet among tourism students in Slovenia, Croatia, and Montenegro. Sustainability 2025, 17(12), 5440. [CrossRef]

- Abreu, F.; Hernando, A.; Goulão, L.F.; et al. Mediterranean diet adherence and nutritional literacy: An observational cross-sectional study of the reality of university students in a COVID-19 pandemic context. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health 2023, 6(2), 221–230. [CrossRef]

- Grant, F.; Aureli, V.; Di Veroli, J.N.; Rossi, L. Mapping of the adherence to the planetary health diet in 11 European countries: Comparison of different diet quality indices as a result of the PLAN'EAT project. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1645824. Published 2025 Sep 17. [CrossRef]

- Kaić-Rak, A.; Antonić, K. Tablice o sastavu namirnica i pića; Zavod za Zaštitu Zdravlja SR Hrvatske: Zagreb, Croatia, 1990.

- Sofi, F.; Cesari, F.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and health status: Meta-analysis. BMJ 2020, 337, a1344. doi.org:10.1136/bmj.a1344.

- Serra-Majem, L.; Román-Viñas, B.; Sanchez-Villegas, A.; Guasch-Ferré, M.; Corella, D.; La Vecchia, C. Benefits of the Mediterranean diet: Epidemiological and molecular aspects. Molecular Aspects of Medicine 2019, 67, 1–55. [CrossRef]

- Cacau, L.T.; De Carli, E.; de Carvalho, A.M.; et al. Development and validation of an index based on EAT-Lancet recommendations: The Planetary Health Diet Index. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1698. [CrossRef]

- Marx, W.; Veronese, N.; Kelly, J.T.; et al. The dietary inflammatory index and human health: An umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12(5), 1681–1690. [CrossRef]

- Shivappa, N.; Steck, S.E.; Hurley, T.G.; Hussey, J.R.; Hébert, J.R. Designing and developing a literature-derived, population-based dietary inflammatory index. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17(8), 1689–1696. [CrossRef]

- National Food Institute, Technical University of Denmark. Food data (Version 4.2); Technical University of Denmark: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022. Available online: https://frida.fooddata.dk/index.php?lang=en (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. FoodData Central; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/ (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Mertens, E.; Kaptijn, G.; Kuijsten, A.; van Zanten, H.H.E.; Geleijnse, J.M.; van 't Veer, P. SHARP Indicators Database (Version 697 2) [Dataset]. DANS Data Station Life Sciences, 2019. (accessed on 18 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Petersson, T.; Secondi, L.; Magnani, A.; Antonelli, M.; Dembska, K.; Valentini, R.; Varotto, A.; Castaldi, S. SU-EATABLE LIFE: A comprehensive database of carbon and water footprints of food commodities [Dataset]. figshare 2021. (accessed on 18 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Laine, J.E.; Huybrechts, I.; Gunter, M.J.; et al. Co-benefits from sustainable dietary shifts for population and environmental health: An assessment from a large European cohort study. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5(11), e786–e796. [CrossRef]

- Muszalska, A.; Wiecanowska, J.; Michałowska, J.; et al. The role of the planetary diet in managing metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease: A narrative review. Nutrients 2025, 17(5), 862. [CrossRef]

- Dokova, K.G.; Pancheva, R.Z.; Usheva, N.V.; et al. Nutrition transition in Europe: East–West dimensions in the last 30 years—A narrative review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 919112. [CrossRef]

- Perrone, P.; Landriani, L.; Patalano, R.; Meccariello, R.; D’Angelo, S. The Mediterranean diet as a model of sustainability: Evidence-based insights into health, environment, and culture. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22(11), 1658. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Pu, H.; Voss, M. Overview of anti-inflammatory diets and their promising effects on non-communicable diseases. Br. J. Nutr. 2024, 132(7), 898–918. [CrossRef]

- Barber, T.M.; Kabisch, S.; Pfeiffer, A.F.H.; Weickert, M.O. The effects of the Mediterranean diet on health and gut microbiota. Nutrients. 2023;15(9):2150. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chaudhary, A.; Mathys, A. Dietary change and global sustainable development goals. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 771041. [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, E.M.; Mollborn, S.; Hummer, R.A. Health lifestyles across the transition to adulthood: Implications for health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 193, 23–32. [CrossRef]

- Kankaanpää, A.; Tolvanen, A.; Heikkinen, A.; Kaprio, J.; Ollikainen, M.; Sillanpää, E. The role of adolescent lifestyle habits in biological aging: A prospective twin study. eLife 2022, 11, e80729. [CrossRef]

- Nichifor, B.; Zait, L.; Timiras, L. Drivers, barriers, and innovations in sustainable food consumption: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2025, 17(5), 2233. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Martínez, J.; Cussó-Parcerisas, I.; Carrillo-Álvarez, E. Exploring the barriers and facilitators for following a sustainable diet: A holistic and contextual scoping review. Sustainable Prod. Consum. 2024, 46, 476–490. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Sharma, P.; Shu, S.; et al. Global greenhouse gas emissions from animal-based foods are twice those of plant-based foods. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 724–732. [CrossRef]

- Daas, M.C.; Vellinga, R.E.; Pinho, M.G.M.; et al. The role of ultra-processed foods in plant-based diets: Associations with human health and environmental sustainability. Eur. J. Nutr. 2024, 63, 2957–2973. [CrossRef]

- García, S.; Pastor, R.; Monserrat-Mesquida, M.; et al. Ultra-processed foods consumption as a promoting factor of greenhouse gas emissions, water, energy, and land use: A longitudinal assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 891, 164417. [CrossRef]

- Mandouri, J.; Onat, N.C.; Kucukvar, M.; Jabbar, R.; Al-Quradaghi, S.; Al-Thani, S.; Kazançoğlu, Y. Carbon footprint of food production: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15(1), 35630. [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.P.; Chadwick, D.; Saget, S.; et al. Representing crop rotations in life cycle assessment: A review of legume LCA studies. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 1942–1956. [CrossRef]

- Magkos, F.; Tetens, I.; Bügel, S.; Felby, C.; Schacht, S.R.; Hill, J.O.; Ravussin, E.; Astrup, A. A perspective on the transition to plant-based diets: A diet change may attenuate climate change, but can it also attenuate obesity and chronic disease risk? Adv. Nutr. 2020, 1;11(1):1-9. [CrossRef]

- Kalmpourtzidou, A.; Biasini, B.; Rosi, A.; Scazzina, F. Environmental impact of current diets and alternative dietary scenarios worldwide: A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2025, 83(9), 1678–1710. [CrossRef]

- Meier, T.; Christen, O. Gender as a factor in an environmental assessment of the consumption of animal and plant-based foods in Germany. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2012, 17, 550–564. [CrossRef]

- Ridoutt, B.G.; Baird, D.; Hendrie, G.A. Diets within planetary boundaries: What is the potential of dietary change alone? Sustainable Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 802–810. [CrossRef]

- Hallström, E.; Davis, J.; Håkansson, N.; Ahlgren, S.; Åkesson, A.; Wolk, A.; Sonesson, U. Dietary environmental impacts relative to planetary boundaries for six environmental indicators: A population-based study. J. Clean Prod. 2022, 373, 133949. [CrossRef]

- Sundin, N.; Rosell, M.; Eriksson, M.; Jensen, C.; Bianchi, M. The climate impact of excess food intake—An avoidable environmental burden. Resources, Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 174, 105777. [CrossRef]

- Bôto, J.M.; Rocha, A.; Miguéis, V.; Meireles, M.; Neto, B. Sustainability dimensions of the Mediterranean diet: A systematic review of the indicators used and its results. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13(5), 2015–2038. [CrossRef]

| All | Krešić et al., 2009 [20] |

Pavičić Žeželj et al., 2018 [21] |

Kenđel Jovanović et al., 2025 [23] |

p-valueb | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Number | 1684 | 100 | 1005 | 60 | 455 | 27 | 224 | 13 | <0.001 |

| Men | 504 | 30 | 264 | 26 | 119 | 26 | 121 | 54 | <0.001 |

| Women | 1180 | 70 | 741 | 74 | 336 | 74 | 103 | 46 | |

| Agea | 21.95 | 1.89 | 21.97 | 1.74 | 21.60 | 1.94 | 22.67 | 2.19 | <0.001 |

| ≤ 21 years | 754 | 45 | 383 | 38 | 288 | 63 | 83 | 37 | <0.001 |

| > 22 years | 930 | 55 | 622 | 62 | 167 | 37 | 141 | 63 | |

| Study level | |||||||||

| Undergraduate | 843 | 50 | 383 | 38 | 342 | 75 | 118 | 53 | <0.001 |

| Graduate | 841 | 50 | 622 | 62 | 113 | 25 | 106 | 47 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)a | 22.45 | 3.13 | 22.08 | 2.87 | 22.43 | 3.33 | 24.11 | 3.50 | <0.001 |

| Underweight | 85 | 5 | 49 | 5 | 30 | 7 | 6 | 3 | <0.001 |

| Normal weight | 1316 | 78 | 818 | 81 | 359 | 79 | 139 | 62 | |

| Overweight | 243 | 14 | 126 | 13 | 53 | 11 | 64 | 28 | |

| Obesity | 40 | 2 | 12 | 1 | 13 | 3 | 15 | 7 | |

| Physical activity level | |||||||||

| Low | 730 | 43 | 453 | 45 | 232 | 51 | 45 | 20 | <0.001 |

| Normal | 636 | 38 | 428 | 43 | 109 | 24 | 99 | 44 | |

| High | 318 | 19 | 124 | 12 | 114 | 25 | 80 | 36 | |

| Smoking (yes) | 575 | 34 | 340 | 34 | 179 | 39 | 56 | 25 | 0.001 |

| Mediterranean Diet Score (MDS)a | 4.78 | 1.40 | 5.45 | 0.92 | 3.70 | 1.36 | 4.00 | 1.47 | <0.001 |

| Low adherence | 306 | 18 | 24 | 2 | 204 | 45 | 78 | 35 | <0.001 |

| Moderate adherence | 820 | 49 | 489 | 49 | 218 | 48 | 113 | 50 | |

| High adherence | 558 | 33 | 492 | 49 | 33 | 7 | 33 | 15 | |

| Planetary Health Diet Index (PHDI)a | 61.98 | 13.09 | 67.84 | 9.94 | 52.21 | 11.72 | 55.54 | 13.30 | <0.001 |

| 1st quartile | 297 | 18 | 160 | 16 | 106 | 23 | 31 | 14 | <0.001 |

| 2nd quartile | 483 | 29 | 325 | 32 | 101 | 22 | 57 | 25 | |

| 3rd quartile | 330 | 20 | 180 | 18 | 82 | 18 | 68 | 30 | |

| 4th quartile | 574 | 34 | 340 | 34 | 166 | 36 | 68 | 30 | |

| Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII)a | 1.11 | 2.51 | 0.18 | 2.10 | 3.18 | 2.02 | 1.07 | 2.62 | <0.001 |

| Proinflammatory diet (DII > 0) | 1012 | 60 | 460 | 46 | 413 | 91 | 139 | 62 | <0.001 |

| Anti-inflammatory diet (DII < 0) | 672 | 40 | 545 | 54 | 42 | 9 | 85 | 38 | |

| Carbon footprint (kg CO2 eqv.)a | 5.93 | 2.81 | 6.80 | 2.43 | 4.20 | 2.34 | 5.52 | 3.52 | <0.001 |

| Water footprint (m3)a | 2768.49 | 1525.48 | 2380.93 | 768.22 | 2696.85 | 1310.68 | 4652.83 | 2674.74 | <0.001 |

| Ecological footprint (m2*year)a | 7.49 | 4.47 | 6.47 | 2.26 | 7.46 | 4.35 | 11.78 | 6.58 | <0.001 |

| Energy intake (MJ/day)a | 8.74 | 3.05 | 9.16 | 2.63 | 7.40 | 2.93 | 9.59 | 4.03 | <0.001 |

| Protein ratio (animal:vegetable)a | 2.19 | 1.25 | 1.76 | 0.77 | 2.91 | 1.41 | 2.66 | 1.70 | <0.001 |

| SFA : PUFA ratioa | 3.06 | 2.00 | 2.17 | 0.68 | 5.65 | 2.08 | 1.80 | 0.52 | <0.001 |

| Cholesterol (mg/day)a | 368.39 | 216.20 | 326.96 | 174.79 | 377.69 | 222.59 | 435.38 | 280.07 | <0.001 |

| Dietary fibers (g/day)a | 22.18 | 9.79 | 25.76 | 8.85 | 14.94 | 6.97 | 20.82 | 10.28 | <0.001 |

| Calcium (mg/day)a | 966.79 | 414.49 | 1083.90 | 371.27 | 695.58 | 358.90 | 992.26 | 448.54 | <0.001 |

| Iron (mg/day)a | 18.67 | 7.94 | 21.26 | 7.45 | 12.78 | 5.13 | 19.03 | 8.39 | <0.001 |

| Vitamin D (mcg/day)a | 6.61 | 6.92 | 6.60 | 10.53 | 6.84 | 4.06 | 3.66 | 2.45 | <0.001 |

| Folate (mcg/day)a | 253.80 | 153.79 | 289.32 | 152.90 | 150.35 | 82.81 | 304.56 | 170.83 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).