Submitted:

09 December 2025

Posted:

11 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- titanium and aluminum alloys that are adherent to the cutting tool rake face;

-

composite material with an aluminum matrix reinforced with silicon carbide particles (SiCp/Al) that is widely used in the aerospace, optical, and electronics industries for:

- ○

- electronic chip packaging, including for microwave integrated circuits, power modules, and military radio frequency (RF) systems;

- ○

- satellite component manufacturing.

2. Geometry Features of Texturing of PCD Tools

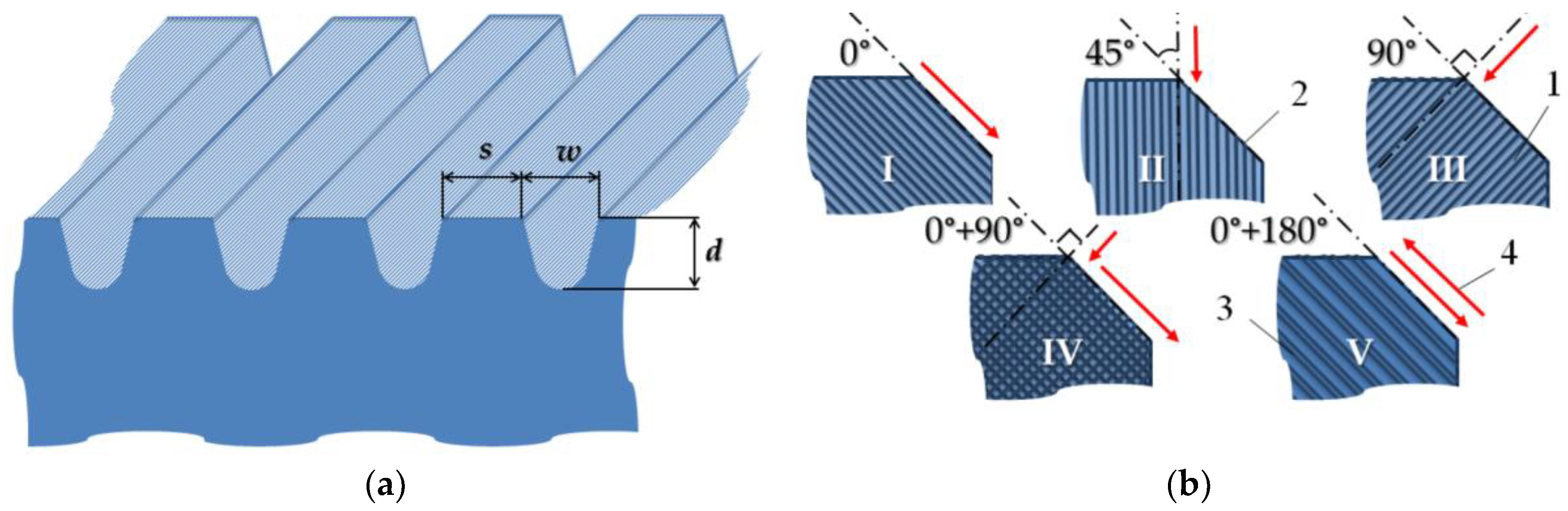

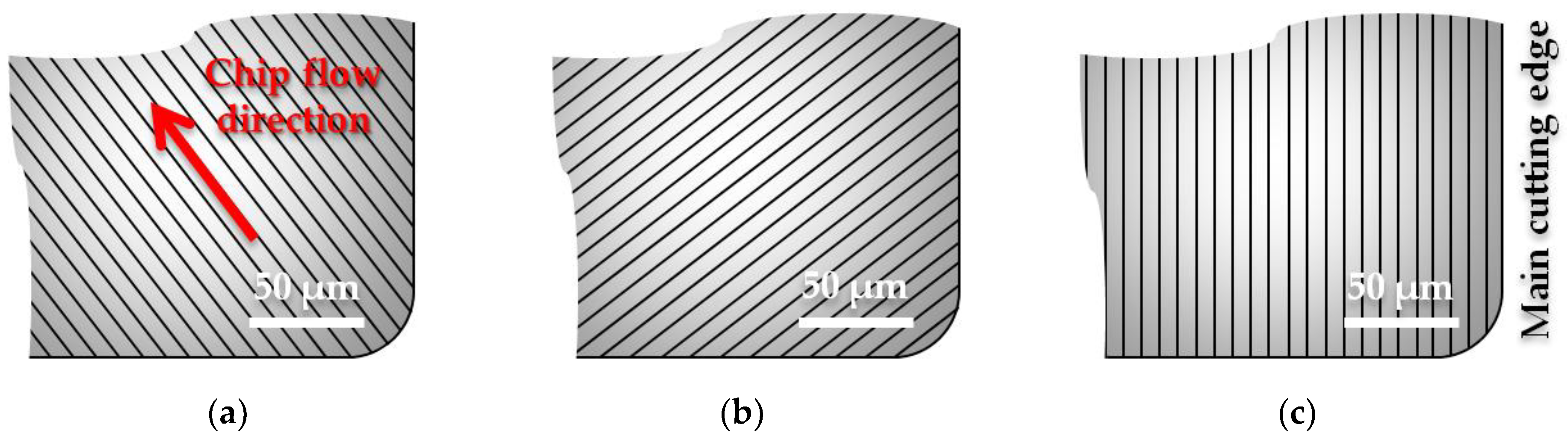

2.1. Influence of Microtexture Orientation on the Tool Performance

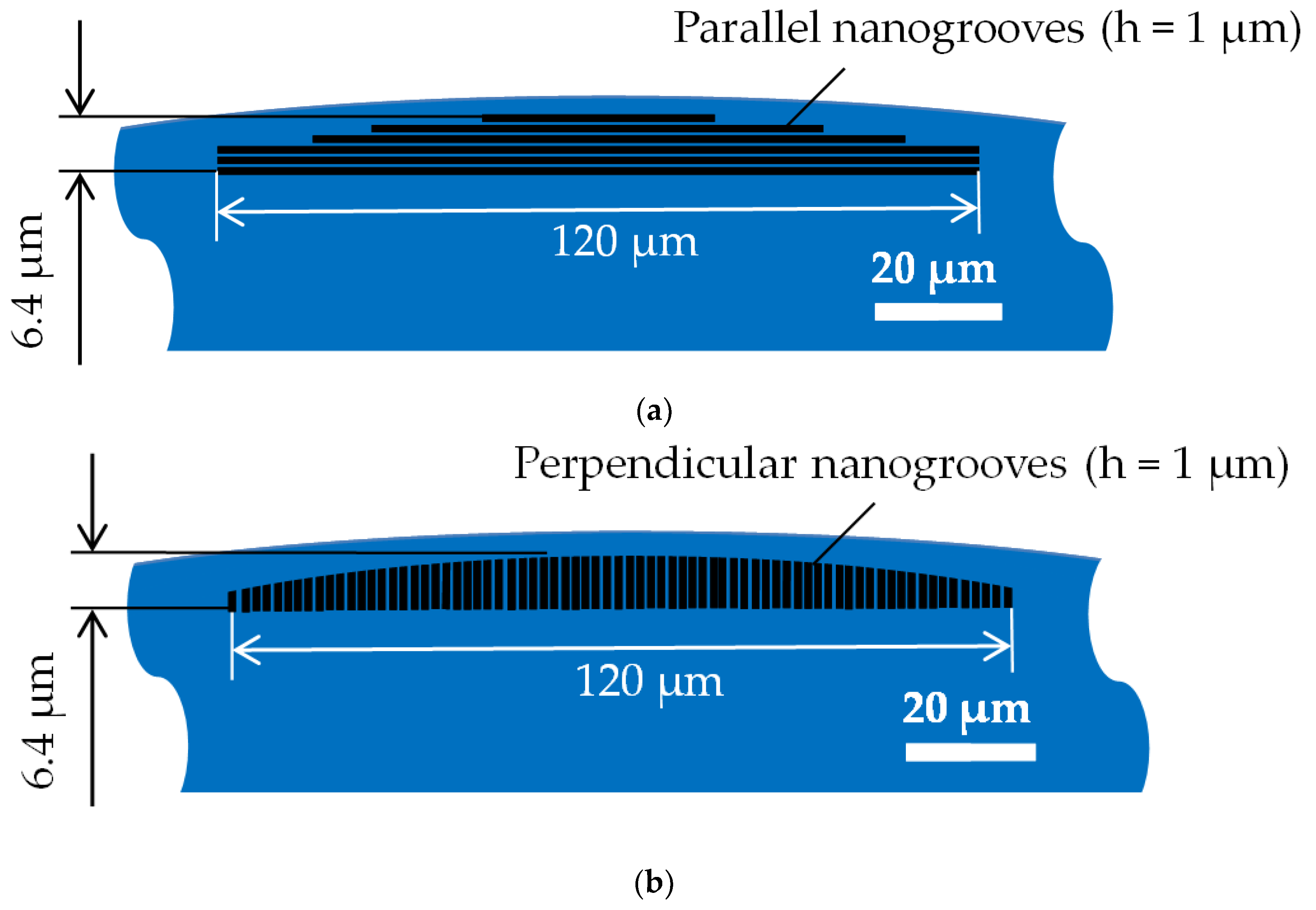

2.2. Influence of Nanotexture Orientation on the Tool Performance

2.3. Influence of Microtexture Profile and Shape on the PCD Tool Performance

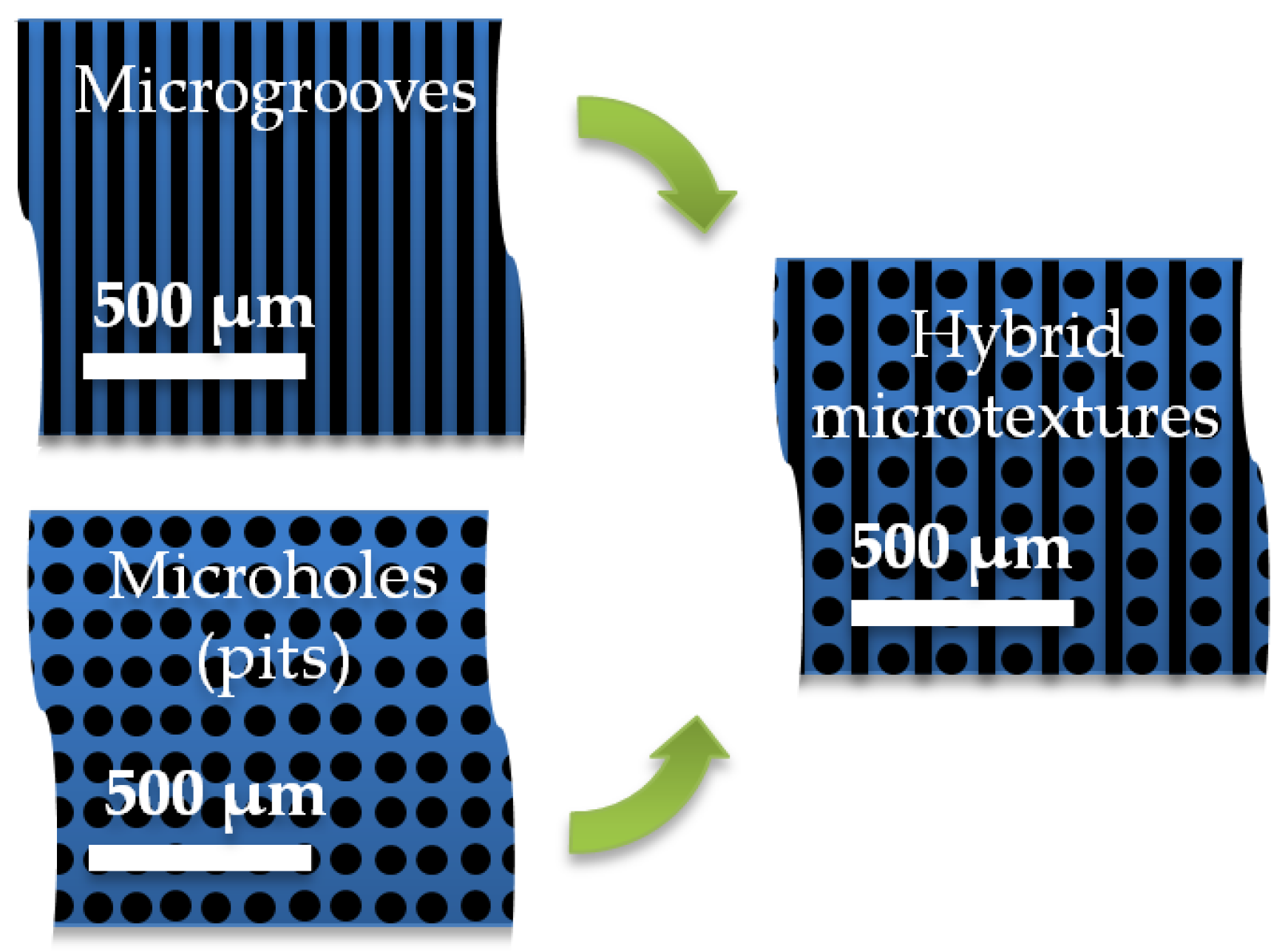

- the width (w) and spacing (s) were 15 μm and 50 μm for the grooves (there were researched three groove widths – 10, 15, 25 µm, where 15 µm have shown better tool performance);

- the diameter (d) and spacing (s) were 50 μm and 80 μm for the pit (there were researched two horizontal (s1 = 80, 100 µm) and two vertical spacings (s2 = 80, 120 µm), where spacing s1=s2=80 µm demonstrated better tool perfomance);

- the pit diameter (d) and groove width (w) were 50 μm and 15 μm, when the horizontal and vertical distance between textures (s1 and s2, respectively) was 70 μm for the hybrid microtextures.

3. Influence of Processing Factors on the Efficiency of Microtextures

3.1. Influence of Processing Factors on the Parameters of Microtextures

- the width (w) of 30 µm for the microgrooves at the power P=11W;

- the diameter (d) of 60 µm for the microholes (pits) at the power P=13W.

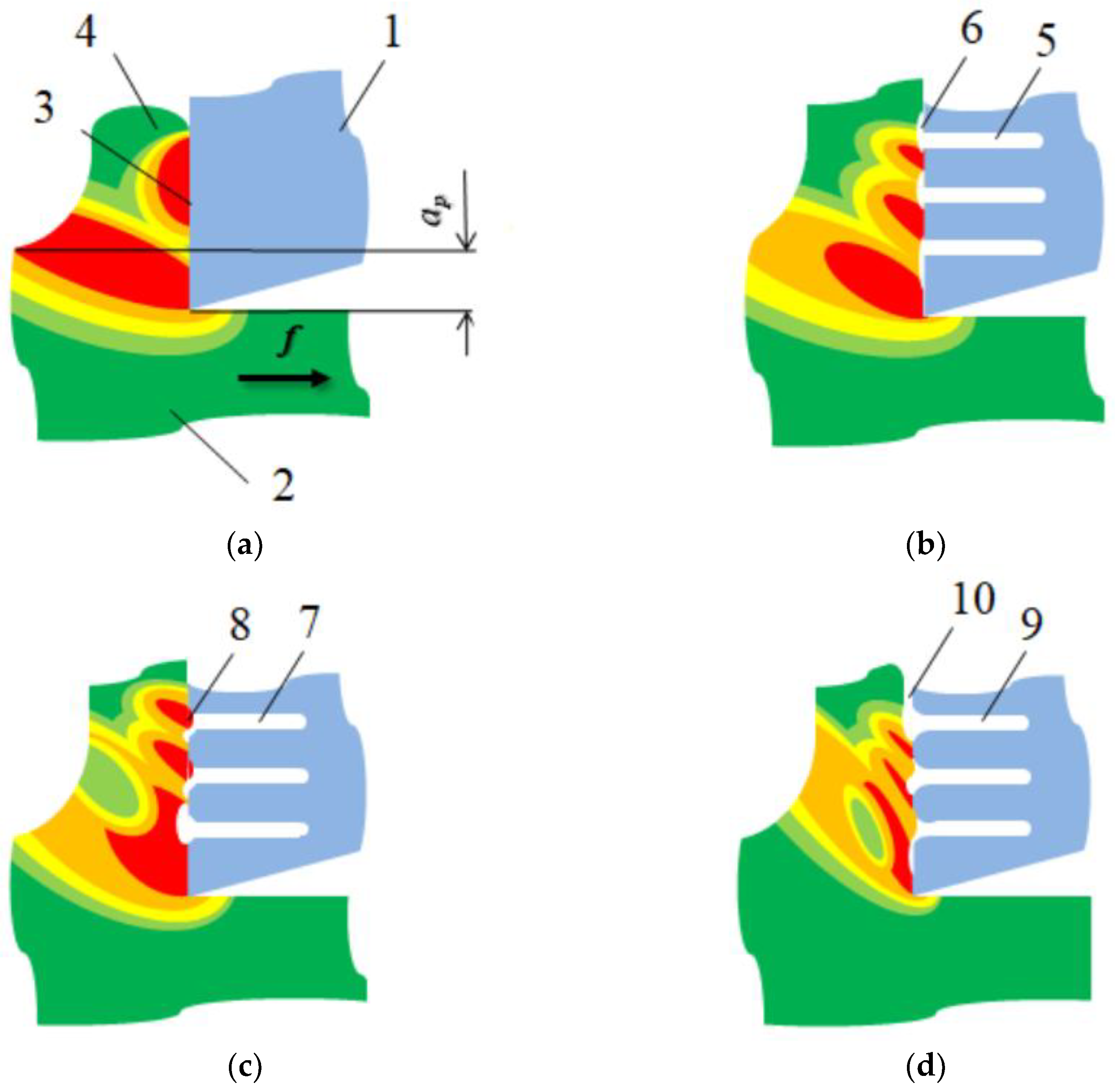

3.2. Influence of Microtexture Area on the Tribological Characteristics of a PCD Tool

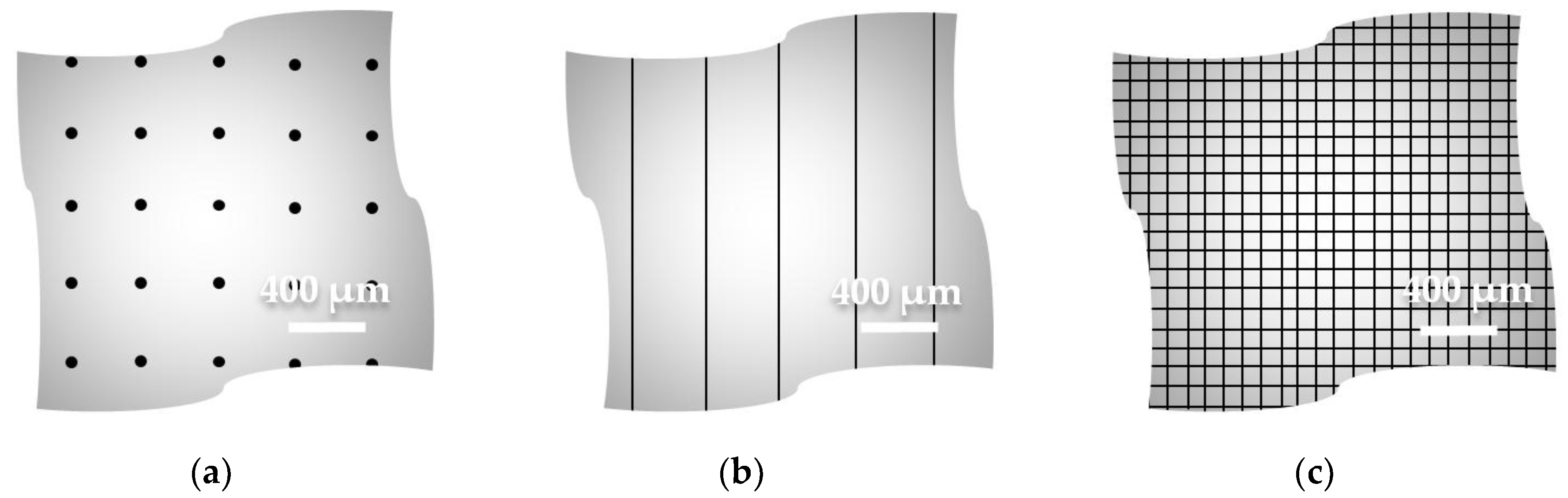

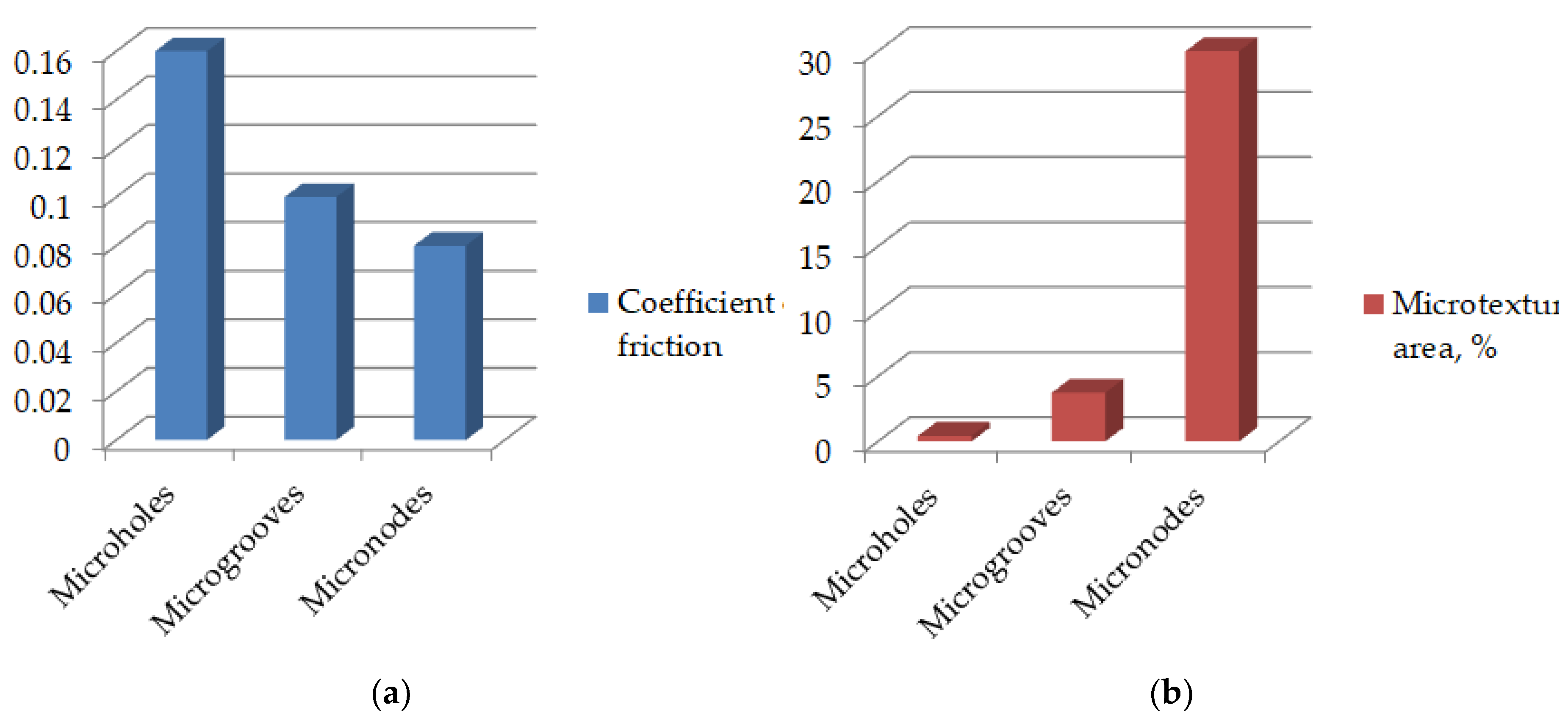

- Microhole diameter (d) was ~21 µm, and the spacing (s) was 400 µm in both directions;

- Microgroove and micronode width (w) was ~15 µm, and the spacing (s) was 400 µm for the microgrooves and 100 µm for the micronodes.

4. Specific Features of Microtexturing of PCD Tool and Performance

4.1. Comparison of the Effects of Microtextured Tools and Cryogen Lubrication on Flank Wear

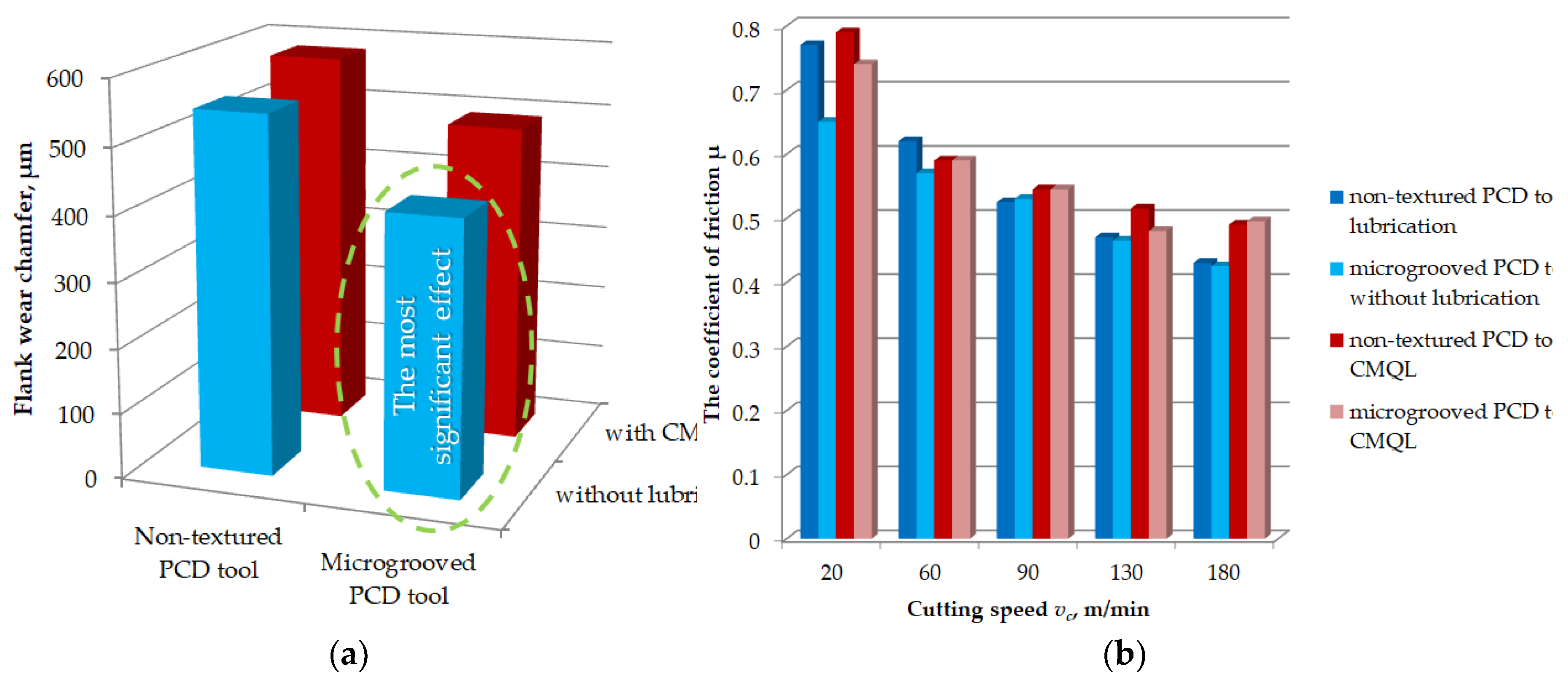

- 547 µm for non-textured PCD tool without lubrication,

- 582 µm for non-textured PCD tool with CMQL,

- 418 µm for microgrooved PCD tool without lubrication,

- and 491 µm for microgrooved PCD tool with CMQL.

4.2. Influence of Lyophobic Wettability of Microtextures on the Tool Performance

4.3. Summarizing the Effect of Microtexturing on the PCD Tool Performance

- The effect of microgrooves perpendicular to the chip flow direction, microholes, micropits, microdimples, and hybrid textures may achieve ~60% and mainly depend on the microtexture area to the area of the contact pad on the rake face rather than on the shape of textures;

- The microgroove’s orientation is preferably perpendicular to the chip flow direction;

- The effect of microtextures achieves ~20% when the effect of nanotextures does not exceed 5% for the improvement of surface quality parameters of the final product;

- The distance from the main cutting edge (tip) of the PCD tool to the texture should be in the range of 30–300 µm to achieve an effect of up to 20% and more for the flank wear and adhesion reduction, prolongation of the operational life of the tool, and improvement of the surface quality parameters for the final product.

5. Conclusions

- The effect of textures on the rake face of the PCD tool mainly depends on the textured area to provide a smaller contact pad between the tool and workpiece;

- There are no specific differences between the microgrooves perpendicular to the chip flow direction, microholes, micronodes, cross-chevron, and hybrid textures, and the effect may achieve ~60%;

- The microgroove’s orientation is preferably perpendicular to the chip flow direction for providing better tool performance;

- The effect of microtextures is at least 5 times more significant than the effect of nanotextures on the surface quality parameters of the final product;

- The distance from the main cutting edge (tip) of the PCD tool to the texture plays one of the key roles and should be in the range of 30–300 µm to achieve the effect of up to 20% and more for the flank wear and adhesion reduction, prolongation of the operational life of the tool, and improvement of the surface quality parameters for the final product;

- The dip-based lyophobic wettability coatings play a significant role in improving the effect of the textures, the effect created by the use of the textured PCD tool on the machined surface;

- The depth of the textures should be around 100–300 µm to provide a remarkable effect in reducing cutting forces by ~60%, when the effect of smaller texture depth (10–70 µm) is less significant (around 20%);

- The smother edges of the textures play a positive role in the chip flow convergence, while the sharp edges and chamfers hamper it; thus, the defocusing of the laser spot by –0.5 to –1.0 µm in laser engraving and ablation is strongly recommended.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benedicto, E.; Rubio, E.M.; Carou, D.; Santacruz, C. The Role of Surfactant Structure on the Development of a Sustainable and Effective Cutting Fluid for Machining Titanium Alloys. Metals 2020, 10, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, G.; Markopoulos, A.P. Tribological Aspects of Slide Friction Diamond Burnishing Process. Materials 2025, 18, 4500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzzone, A.A.G.; Costa, H.L.; Lonardo, P.M.; Lucca, D.A. Advances in engineered surfaces for functional performance. CIRP Ann. 2008, 57, 750–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, S.N.; Volosova, M.A.; Fedorov, S.V.; Migranov, M.S.; Mosyanov, M.; Gusev, A.; Okunkova, A.A. The Effectiveness of Diamond-like Carbon a-C:H:Si Coatings in Increasing the Cutting Capability of Radius End Mills When Machining Heat-Resistant Nickel Alloys. Coatings 2022, 12, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metel, A.S.; Grigoriev, S.N.; Tarasova, T.V.; Filatova, A.A.; Sundukov, S.K.; Volosova, M.A.; Okunkova, A.A.; Melnik, Y.A.; Podrabinnik, P.A. Influence of Postprocessing on Wear Resistance of Aerospace Steel Parts Produced by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Technologies 2020, 8, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.-L.; Xing, Y.; K. F.; Ehmann, B.-F.; Ju. Ultrasonic elliptical vibration texturing of the rake face of carbide cutting tools for adhesion reduction. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, vol. 85(no. 9–12), 2669–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Wang, D.; Zheng, M.; Li, Q.; Mu, H.; Liu, C.; Xia, Y.; Jiang, H.; Wang, F.; Hu, Q. Study on Cutting Performance and Wear Resistance of Biomimetic Micro-Textured Composite Cutting Tools. Metals 2025, 15, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, A.; Hegab, H.; Kishawy, H.A. Experimental Investigation of the Derivative Cutting When Machining AISI 1045 with Micro-Textured Cutting Tools. Metals 2023, 13, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volosova, M.A.; Okunkova, A.A.; Hamdy, K.; Malakhinsky, A.P.; Gkhashim, K.I. Simulation of Mechanical and Thermal Loads and Microtexturing of Ceramic Cutting Inserts in Turning a Nickel-Based Alloy. Metals 2023, 13, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratap, A; Patra, K. Combined effects of tool surface texturing, cutting parameters and minimum quantity lubrication (MQL) pressure on micro-grinding of BK7 glass. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 54, 374–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Yang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, M. Study of the Cutting Performance of Ti-6Al-4 V Alloys with Tools Fabricated with Different Microgroove Parameters. Materials 2025, 18, 4312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Tong, X.; Wang, B. Research on the Friction Prediction Method of Micro-Textured Cemented Carbide–Titanium Alloy Based on the Noise Signal. Coatings 2025, 15, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Wang, D.; Zheng, M.; Li, Q.; Mu, H.; Liu, C.; Xia, Y.; Jiang, H.; Wang, F.; Hu, Q. Study on Cutting Performance and Wear Resistance of Biomimetic Micro-Textured Composite Cutting Tools. Metals 2025, 15, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.V.; Jarosz, K.; Özel, T. Physics-Based Simulations of Chip Flow over Micro-Textured Cutting Tool in Orthogonal Cutting of Alloy Steel. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2021, 5, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Liu, X.; Yu, S. Anti-Friction and Anti-Wear Mechanisms of Micro Textures and Optimal Area Proportion in the End Milling of Ti6Al4V Alloy. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2019, 3, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, G.; Jia, F.; Jiang, X.; Jiang, N.; Wang, C.; Lin, Z. Improvements in Wettability and Tribological Behavior of Zirconia Artificial Teeth Using Surface Micro-Textures. Materials 2025, 18, 3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Z.; Zhu, H.; He, Y.; Shao, B.; Sheng, Z.; Wang, S. Tribological Effects of Surface Biomimetic Micro–Nano Textures on Metal Cutting Tools: A Review. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, P.; Liu, B.; Guo, C.; Cui, P.; Hou, Z.; Jin, F.; Zhang, J.; Guo, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, W. Study on Effect of Surface Micro-Texture of Cemented Carbide on Tribological Properties of Bovine Cortical Bone. Micromachines 2024, 15, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumalai Kumaran, S.; Ko, T. J.; Uthayakumar, M.; Adam Khan, M.; Niemczewska-Wójcik, M. Surface texturing by dimple formation in TiAlSiZr alloy using μ-EDM. J. Aust. Ceram. Soc. 2017, 53, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, S.N.; Okunkova, A.A.; Volosova, M.A.; Hamdy, K.; Metel, A.S. Electrical Discharge Machining of Al2O3 Using Copper Tape and TiO2 Powder-Mixed Water Medium. Technologies 2022, 10, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Pérez, M.; Hernández-Castellano, P.M.; Salguero-Gómez, J.; Sánchez-Morales, C.J. Improved Design of Electroforming Equipment for the Manufacture of Sinker Electrical Discharge Machining Electrodes with Microtextured Surfaces. Materials 2025, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volosova, M.A.; Okunkova, A.A.; Kropotkina, E.Y.; Mustafaev, E.S.; Gkhashim, K.I. Wear Resistance of Ceramic Cutting Inserts Using Nitride Coatings and Microtexturing by Electrical Discharge Machining. Eng 2025, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas, J.; Lopes, H.; Guimarães, B.; Piloto, P.A.G.; Miranda, G.; Silva, F.S.; Paiva, O.C. Influence of Micro-Textures on Cutting Insert Heat Dissipation. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Wang, B. Study on the Optimization of Textured Coating Tool Parameters Under Thermal Assisted Process Conditions. Coatings 2025, 15, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Yang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, M. Study of the Cutting Performance of Ti-6Al-4 V Alloys with Tools Fabricated with Different Microgroove Parameters. Materials 2025, 18, 4312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picard, Y.N.; Adams, D.P.; Vasile, M.J.; Ritchey, M.B. Focused ion beam-shaped microtools for ultra-precision machining of cylindrical components. Precision Engineering 2003, 27, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chayeuski, V.; Zhylinski, V.; Kazachenko, V.; Tarasevich, A.; Taleb, A. Structural and Mechanical Properties of DLC/TiN Coatings on Carbide for Wood-Cutting Applications. Coatings 2023, 13, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, SN; Volosova, MA; Okunkova, AA; Fedorov, SV; Hamdy, K; Podrabinnik, PA. Elemental and Thermochemical Analyses of Materials after Electrical Discharge Machining in Water: Focus on Ni and Zn. Materials 2021, 14, 3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, S.N.; Volosova, M.A.; Okunkova, A.A.; Fedorov, S.V.; Hamdy, K.; Podrabinnik, P.A. Sub-Microstructure of Surface and Subsurface Layers after Electrical Discharge Machining Structural Materials in Water. Metals 2021, 11, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigor’ev, S.N.; Fedorov, S.V.; Pavlov, M.D.; Okun’kova, A.A.; So, Ye Min. Complex surface modification of carbide tool by Nb plus Hf plus Ti alloying followed by hardfacing (Ti plus Al)N. Journal of Friction and Wear 2013, 34, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, S.N.; Volosova, M.A.; Okunkova, A.A.; Fedorov, S.V.; Hamdy, K.; Podrabinnik, P.A.; Pivkin, P.M.; Kozochkin, M.P.; Porvatov, A.N. Wire Tool Electrode Behavior and Wear under Discharge Pulses. Technologies 2020, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumalai Kumaran, S.; Ko, T.J.; Uthayakumar, M.; Adam Khan, M.; Niemczewska-Wójcik, M. Surface texturing by dimple formation in TiAlSiZr alloy using μ-EDM. J. Aust. Ceram. Soc. 2017, 53, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, C.M.; Rao, S.S.; Herbert, M.A. Development of novel cutting tool with a micro-hole pattern on PCD insert in machining of titanium alloy. J. Manuf. Process. 2018, 36, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Lucio, P.; Villarón-Osorno, I.; Pereira Neto, O.; Ukar, E.; López de Lacalle, L.N.; Gil del Val, A. Effects of laser-textured on rake face in turning PCD tools for Ti6Al4V. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 15, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, G.; Zhong, X. Cutting mechanism and performance of high-speed machining of a titanium alloy using a super-hard textured tool. J. Manuf. Process. 2018, 34, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; et al. Evaluation of the cutting performance of micro-groove-textured PCD tool on SiCp/Al composites. Ceram. Int. 2021, 48, 32389–32398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakthivel, G.; Sathiya Narayanan, N.; Vedha Hari, B. N.; Sriraman, N.; AanandhaManikandan, G.; Suraj Nanduru, V.S.P. Performance of surface textured PCD inserts with wettability chemical solutions for machining operation. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 8283–8287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhang, N.; Peng, W.; Sun, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Z. A novel hybrid micro-texture for improving the wear resistance of PCD tools on cutting SiCp/Al composites. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 101, 930–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Cui, W.; Li, L.; Li, H.; Khan, A. M.; He, N. Cutting performance of textured polycrystalline diamond tools with composite lyophilic/lyophobic wettabilities. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2018, 260, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P.; Pacella, M. Effect of laser texturing on the performance of ultra-hard single-point cutting tools. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 106, 2635–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Li, L.; He, N.; Zhao, W. Experimental study of fiber laser surface texturing of polycrystalline diamond tools. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2014, 45, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeng, S.; Min, S. Dry Ultra-Precision Machining of Tungsten Carbide with Patterned nano PCD Tool. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 48, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, S.N.; Metel, A.S.; Tarasova, T.V.; Filatova, A.A.; Sundukov, S.K.; Volosova, M.A.; Okunkova, A.A.; Melnik, Y.A.; Podrabinnik, P.A. Effect of Cavitation Erosion Wear, Vibration Tumbling, and Heat Treatment on Additively Manufactured Surface Quality and Properties. Metals 2020, 10, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigor’ev, S.N.; Fedorov, S.V.; Pavlov, M.D.; Okun’kova, A.A.; So, Y.M. Complex surface modification of carbide tool by Nb + Hf + Ti alloying followed by hardfacing (Ti + Al)N. J. Frict. Wear 2013, 34, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momma, C; Nolte, S; Chichkov, BN; Alvensleben, FV; Tünnermann, A. Precise laser ablation with ultrashort pulses. Appl Surf Sci 1997, 109–110, 15–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chichkov, B.N.; Momma, C.; Nolte, S.; Von Alvensleben, F.; Tünnermann, A. Femtosecond, picosecond and nanosecond laser ablation of solids. Appl Phys A Mater Sci Process 1996, 63, 109–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Popov, V.L.; Yu, Z.; Li, Y.; Xu, J.; Li, Q.; Yu, H. Preparation of Micro-Pit-Textured PCD Tools and Micro-Turning Experiment on SiCp/Al Composites. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, Y.; Yu, Z.; Xu, J.; Yu, H. Micro-hole texture prepared on PCD tool by nanosecond laser. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 147, 107615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Klein, S. Surface structuring of polycrystalline diamond (PCD) using ultrashort pulse laser and the study of force conditions. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2019, 84, 105036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusarov, A.V.; Okun’kova, A.A.; Peretyagin, P.Y.; et al. Means of Optical Diagnostics of Selective Laser Melting with Non-Gaussian Beams. Meas Tech 2015, 58, 872–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okunkova, A.A.; Shekhtman, S.R.; Metel, A.S.; Suhova, N.A.; Fedorov, S.V.; Volosova, M.A.; Grigoriev, S.N. On Defect Minimization Caused by Oxide Phase Formation in Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Metals 2022, 12, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okunkova, A.; Peretyagin, P.; Vladimirov, Yu.; et al. Laser-beam modulation to improve efficiency of selecting laser melting for metal powders. Proc. SPIE 2014, 9135, 913524. [Google Scholar]

- Jouini, N.; Yaqoob, S.; Ghani, J.A.; Mehrez, S. Tool Wear Effect on Machinability and Surface Integrity in MQL and Cryogenic Hard Turning of AISI 4340. Materials 2025, 18, 5423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, M. Influence of Cooling Strategies on Surface Integrity After Milling of NiTi Alloy. Materials 2025, 18, 5472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudill, J.; Sarvesha, R.; Chen, G.; Jawahir, I.S. An Investigation of the Effects of Cutting Edge Geometry and Cooling/Lubrication on Surface Integrity in Machining of Ti-6Al-4V Alloy. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2024, 8, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaynak, Y.; Gharibi, A. Progressive Tool Wear in Cryogenic Machining: The Effect of Liquid Nitrogen and Carbon Dioxide. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2018, 2, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Microtexturing | Parameters of microtextures, µm | Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

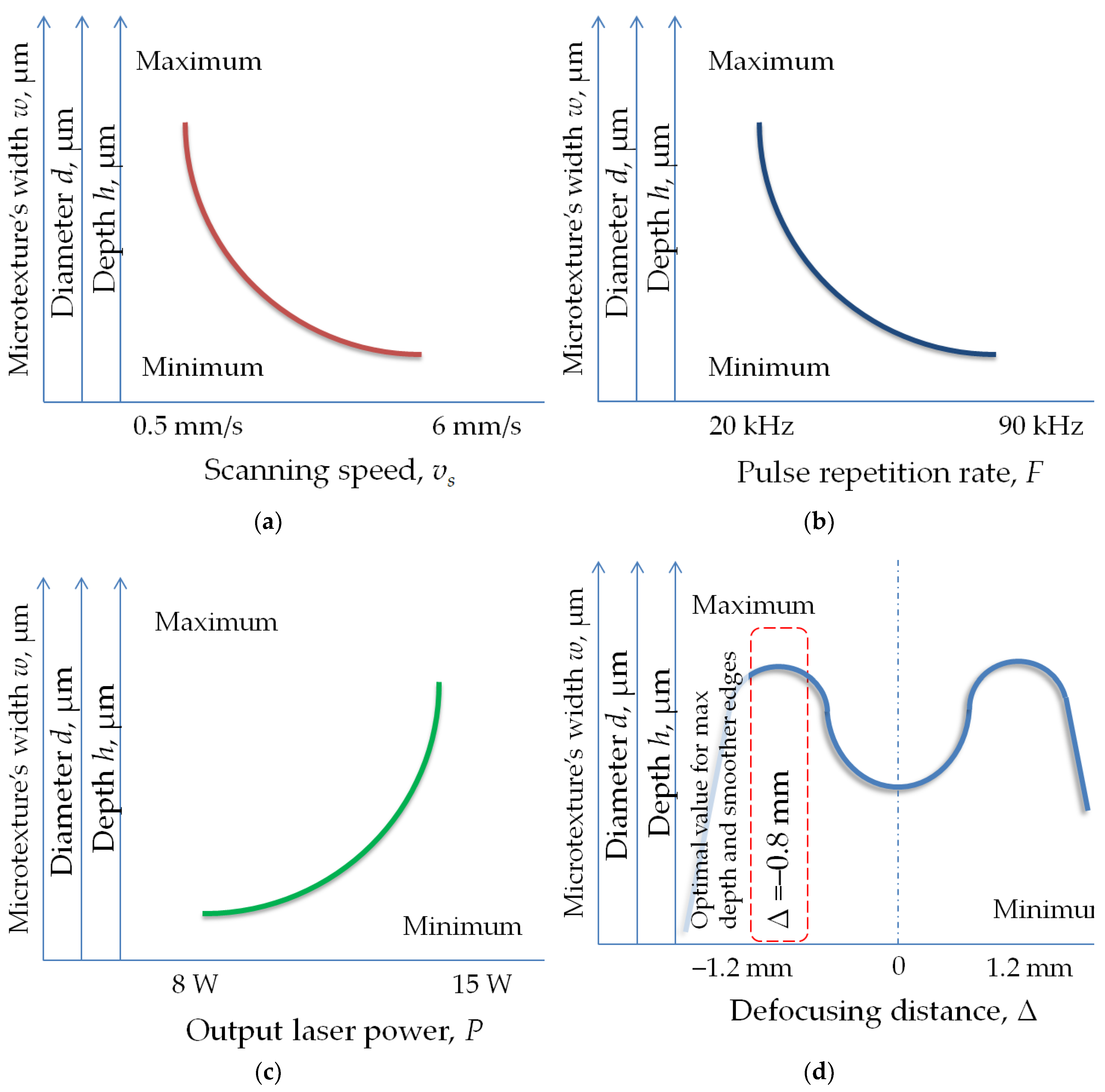

| Technology | Factors | |||

| [41] | Fiber laser | P=8–15 W, vs=0.5–6 mm/s, F=20–90 kHz, Δ=0.5–1.2 mm | Microgrooves and microholes: w= 30 µm, h=55 µm for the microgrooves and d=60 µm, h=73 µm for the microholes | The width, diameter, and depth of the microtextures are reduced with a higher scanning speed and pulse repetition rate and a lower average output power; the maximum depth (h) and smoother edges were achieved when Δ=–0.8 mm |

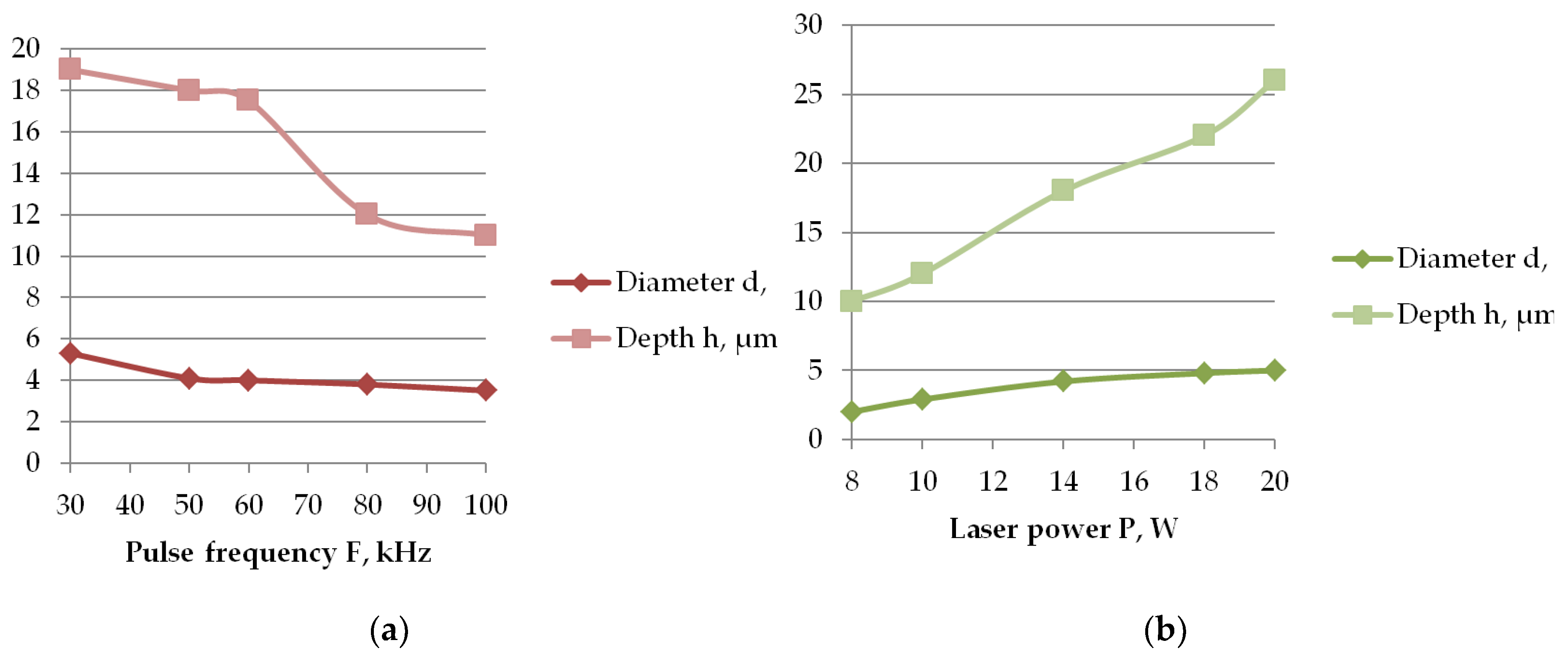

| [48] | Nano-second laser | P=8–20 W, F=20–100 kHz, Δ=4 μm, λ=1064 nm, τ=100 ns, E=1 mJ (for 20W and 20 kHz), d0=1.265 µm (emission diameter = 6.5 mm), M2<1.4 |

Microholes d=2–10 µm | High laser power, low pulse frequency, and large positive defocus are used to process the PCD surface to obtain a large diameter. The vase-shaped micro-holes occur under circumstances of positive defocusing amount, low pulse frequency, and high power. |

| [49] | Femto-second laser | τ=150 fs, λ=800 nm, F= 1000 Hz, w0=8 mm, Δ=100 mm,E=600 μJ |

Microgrooves, microholes, micronodes (cross-hatching) | The coefficient of friction for micronodes was 0.08, CoF was 0.10 for microgrooves, and CoF was 0.16 for microholes |

| Ref. | Workpiece material | Microtexturing | Parameters of microtextures, µm | Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technology | Factors | ||||

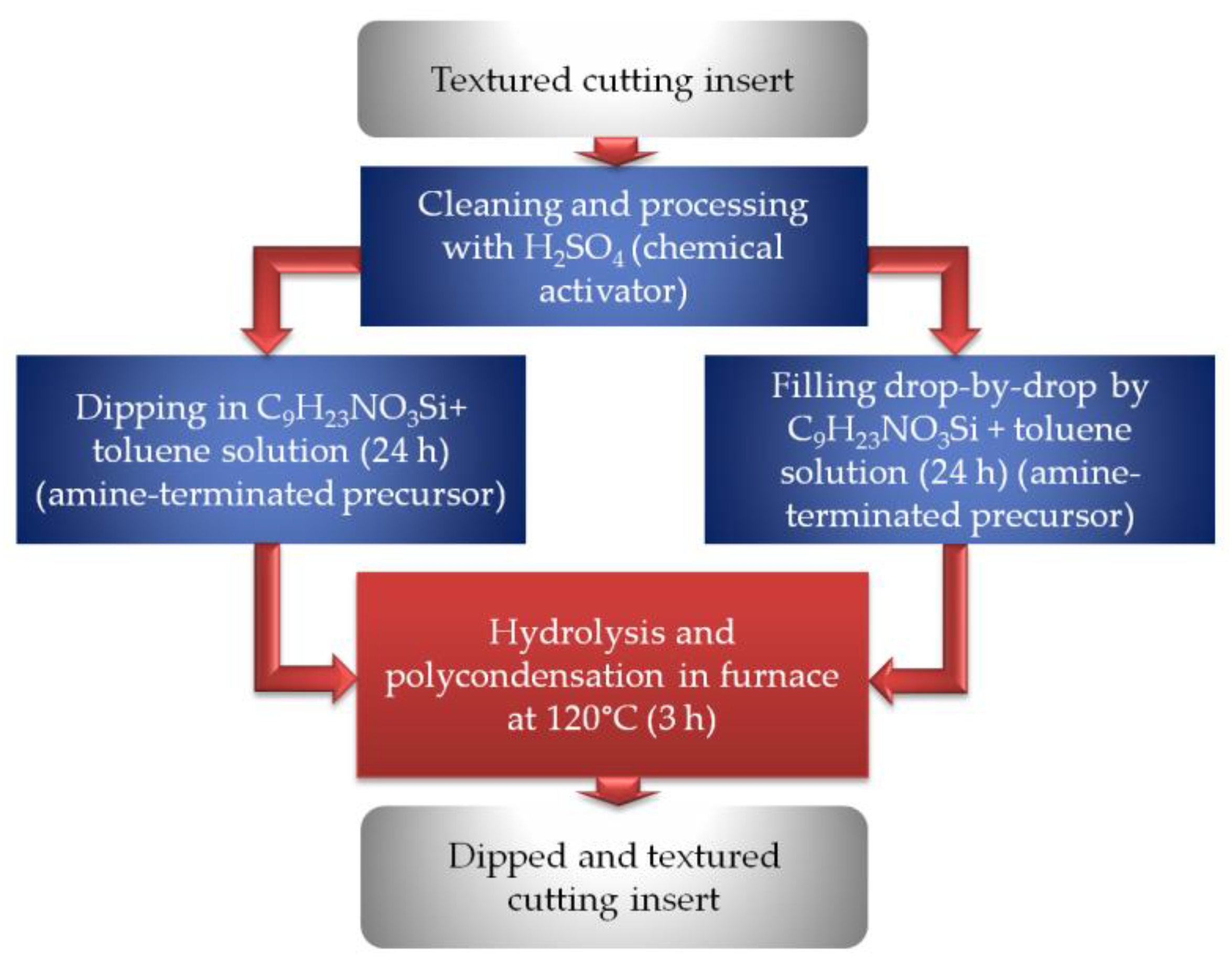

| [37] | Al 6061-T6 alloy | ND: YAG laser graving | Dip-coating method: fluoroalkyl silane solution for 24 h + oven at 120 °C for 3 h; Drop-coating method: fluoroalkyl silane solution drop-by-drop + oven at 120 °C for 3 h |

Cross-chevron textures + dip- and drop-based lyophobic wettability coatings: l=1.5 mm, wt=1.5 mm, w=80 µm, angle=40°, h=200 µm | Reduction was by 60–65% for cutting force and 60–62% for thrust force comparing the dip-based lyophobic wettability inserts with cross-chevron textures and non-textured cutting inserts |

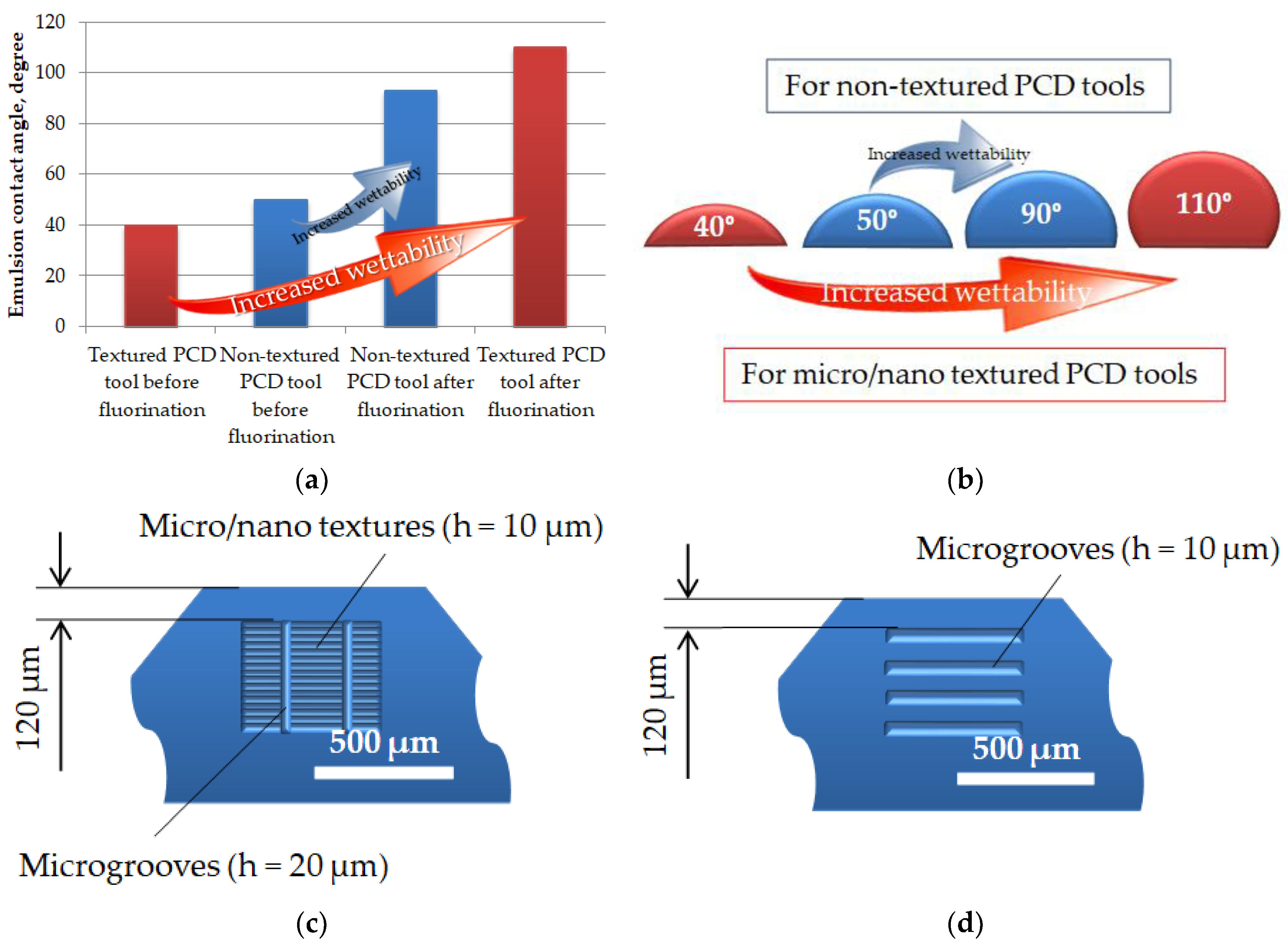

| [39] | Ti6Al4V alloy | Fiber laser graving (1) + fluorination (2) + fiber laser graving (3) | Step 1 and 3: τ=100 ns, λ=1064 nm, Δ=210 mm, E = 0.25 mJ and 0.27 mJ, vs = 80 mm/s and 200 mm/s, laser scanning times β = 2 and 1; Step 2: 0.8% fluoroalkyl silane solution for 24 h + oven at 140 °C for 120 min |

Micro/nano textures: m=120µm, w=30 µm, (1) s=30 μm, h=20 µm for textures with the peaks of 10 µm; (3) h=20 µm for microgrooves |

The coefficient of friction for fluorinated textured tools decreased by 11–12%, the flank wear was reduced by 22.3%, reduction in cutting forces by 4–6% |

| Ref. | Cutting technology | Cutting tool | Workpiece material | Microtexturing | Parameters of microtextures, µm | Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technology | Factors | ||||||

| [33] | Turning | PCD cutting insert | Ti6Al4V alloy | Electrical discharge machining | Copper wires with diameters of 0.4 mm and 0.6 mm + Deionized water | Microholes with tunnels | Tool flank wear reductions by 40–62% |

| [34] | Turning | PCD cutting insert | Ti6Al4V alloy | Laser micro graving | τ=250 ns, F=30–50 Hz, vs=300–500 mm/s | Microgrooves: m=100 µm, w=50 µm, s=50 µm, d=10 µm, r=0.02–0.05 mm; h=10 µm | Helical chip shape at 0° and 45°, no reduction in cutting forces, insignificant reduction in roughness |

| [35] | Turning | PCD tool | Ti6Al4V alloy | Fiber laser graving | λ=1055–1070 nm, τ=100 ns, vs= 2 mm/s F=20 kHz, P=12 W; Δ=–0.6 mm, β=50 times, production time=1500 s | Microgrooves: m=300 µm; l=1500 µm, w=60 µm, h=~60–63 µm, s=85 µm | The microgrooved tool reduced the flank wear by 23.6%; the coefficient of friction μ for the microgrooved tool without lubrication was 3%–18% less than that for the non-textured PCD tool with cryogenic lubrication |

| [36] | Micro–cutting | PCD tool | SiCp/Al composite | Infrared nanosecond pulsed laser ablation | Pause p=100 ns, F=20kHz, λ=1064 nm, D0=6.5 mm | Microgrooves: m=25–45 µm, w=16 µm, s=40–80 µm, l=1000 µm, d=70 µm, h=70 µm | Microgrooves with m=35 µm and s=40 µm – reduction in cutting forces by 4–20% and Ra by 22% |

| [38] | Milling | Hard alloy tool inlaid with PCD | SiCp/Al composite | Femtosecond laser ablation | U=100 mW 1, vs=0.5 mm/s | Hybrid: d = 50 µm, w = 15 µm, s1 = s2 =70 µm | The operational life was improved by 2.13 times, the flank wear was reduced by 54%; Ra was 1.4 µm |

| [40] | Turning | PCD cutting insert | Al 6082 alloy | Fiber laser | Fiber laser: P=70W, λ = 1064 nm, τ = 260 ns, F=70 kHz | Microgrooves: h=260 nm, w=7 μm, s=20 μm | Parallel-to-chip-flow-direction grooves reduced the cutting forces by 12%, adhesion by 59%, and the coefficient of friction by 14% |

| [42] | Ultra-precision machining | PCD tool | Tungsten carbide | Fused ion beam | Accelerating voltage of 30KeV, beam size of 600 pA, ions of Gallium, incident angle of 0°, ion dose of 20 nC/μm2 | Nanogrooves: m=2 µm; l=35–120 µm, w=0.8 µm, h=1 µm, s=1 µm |

The coefficient of friction of parallelly and perpendicularly nano-textured tools to the cutting direction of nano-textured tools was improved by 7% and 10%, respectively, Ra parameter was improved by 3–5% for parallelly textured tools. Perpendicularly textured tools have shown no effect |

| [47] | Turning | PCD tool | SiCp/Al composite | Nano-second laser | P=20 W, λ=1064 nm, τ=100 ns, F=20 kHz, D0=6.5 mm | Micropits: m=35 μm, s=60 μm. | The cutting forces were reduced by 22%; the black wear scratching, tool wear, and adhesion were reduced |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).