Submitted:

09 December 2025

Posted:

10 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

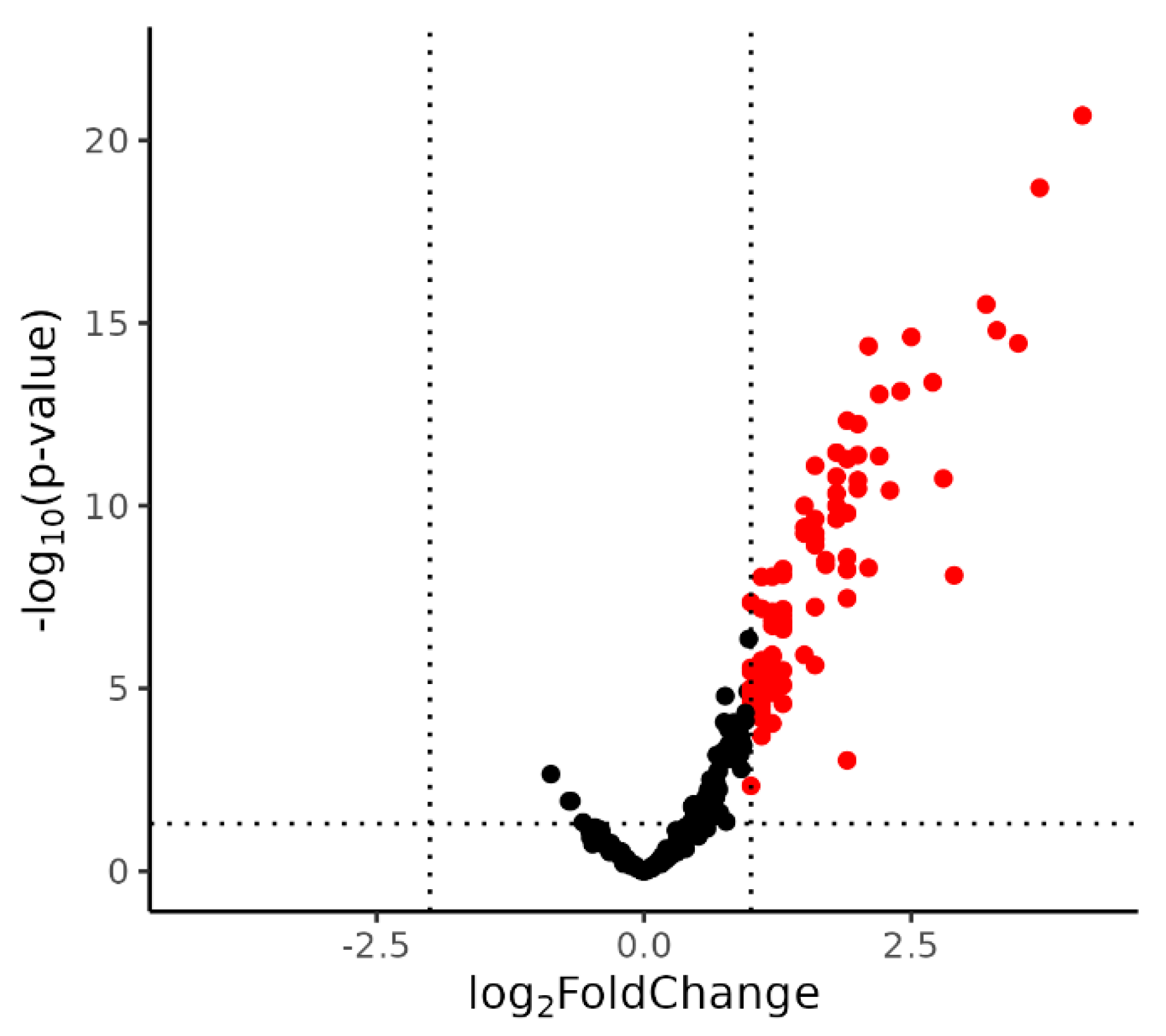

2.1. Identification of DE miRNA

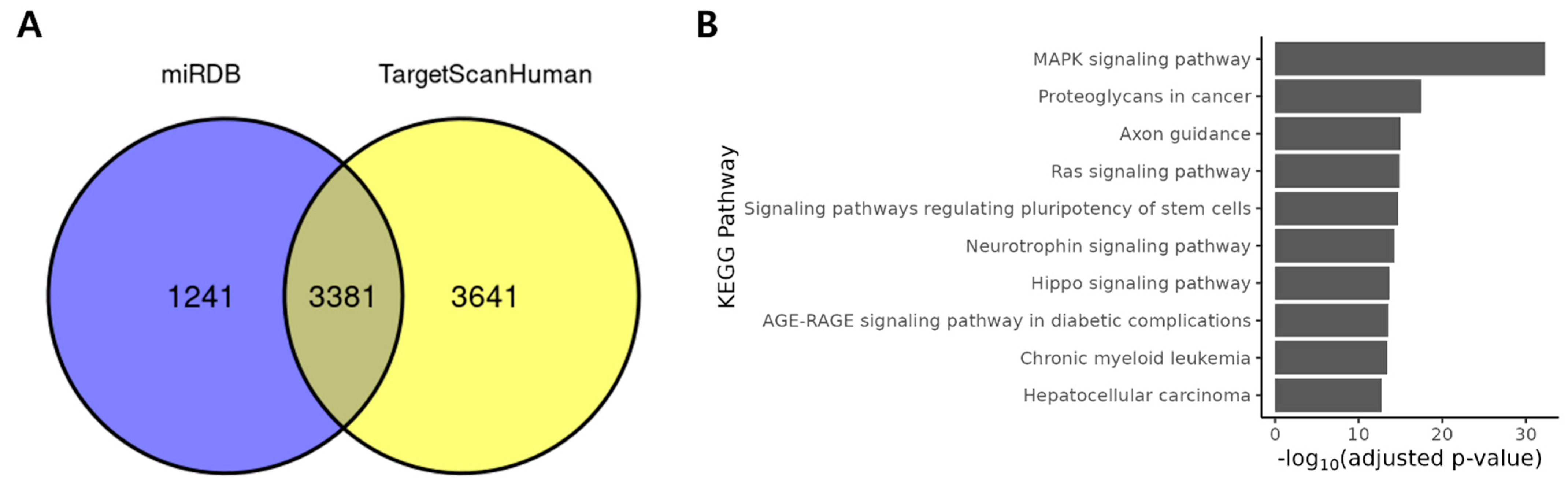

2.2. DE miRNAs Regulates Cancer Related Pathways

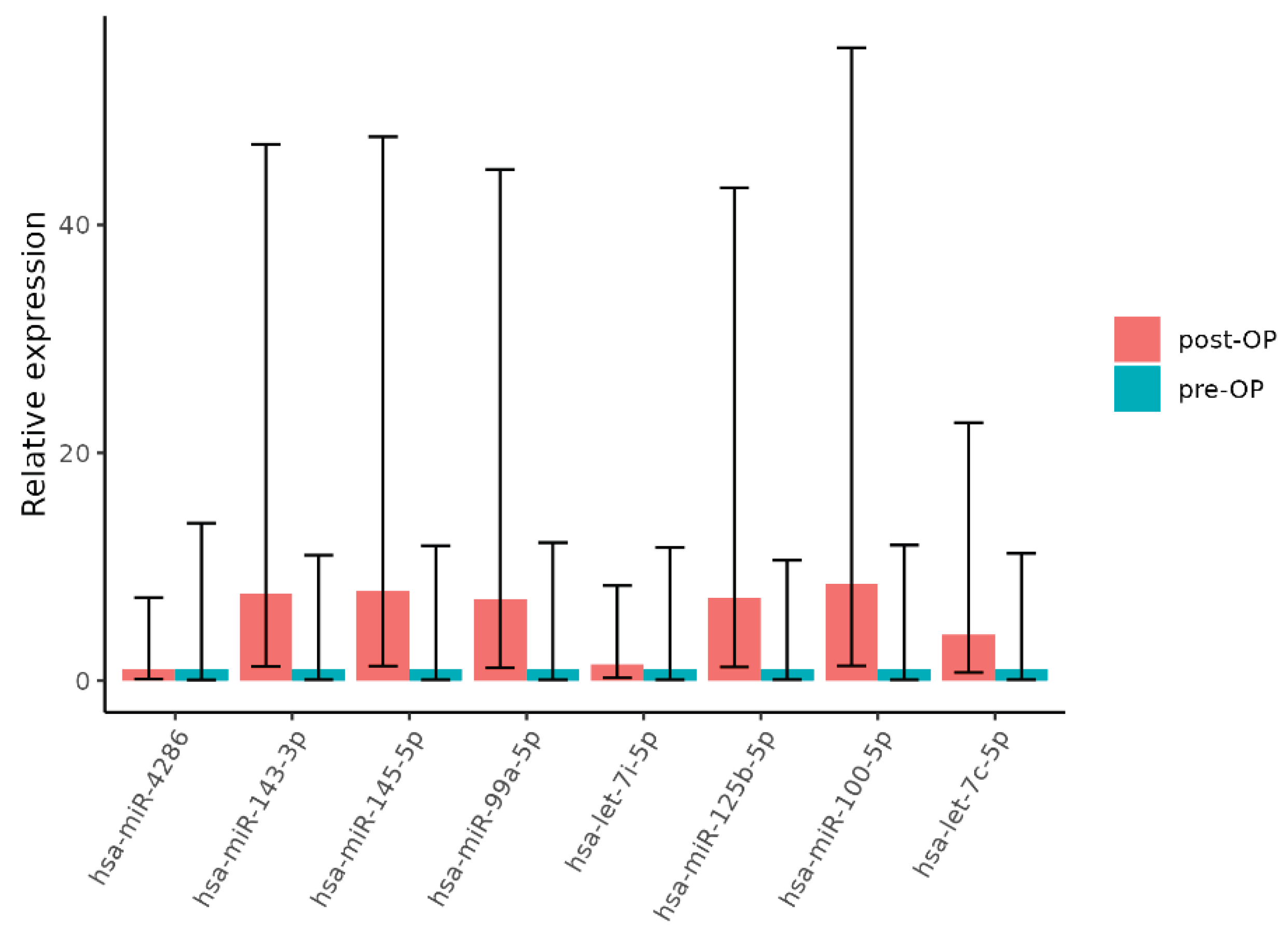

2.3. Validation of miRNA Expression

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients

4.2. RNA Extraction and Quantification

4.3. miRNA Microarray Expression by NanoString

4.4. miRNA Expression Analysis

4.5. Functional Analysis

4.6. qRT-PCR Validation

4.7. Validation of miRNA Using qRT-PCR

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin 2025, 75(1), 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.H. Cancer Statistics in Korea: Incidence, Mortality, Survival, and Prevalence in 2021. Cancer Res Treat 2024, 56(2), 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmeiner, W.H. Recent Advances in Therapeutic Strategies to Improve Colorectal Cancer Treatment. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maida, M. Screening of colorectal cancer: present and future. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2017, 17(12), 1131–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreuders, E.H. Colorectal cancer screening: a global overview of existing programmes. Gut 2015, 64(10), 1637-49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franke, A.J. Total Neoadjuvant Therapy: A Shifting Paradigm in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer Management. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2018, 17(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasi, A. Total Neoadjuvant Therapy vs Standard Therapy in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2020, 3(12), e2030097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C. The Effects of Neoadjuvant Treatment on the Tumor Microenvironment in Rectal Cancer: Implications for Immune Activation and Therapy Response. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2020, 19(4), e164–e180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W. Tumor microenvironment remodeling after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in local advanced rectal cancer revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. J Transl Med 2024, 22(1), 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayshetye, P. Tumor Microenvironment before and after Chemoradiation in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer: Beyond PD-L1. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 15(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasui, K. Effect of preoperative chemoradiotherapy on the immunological status of rectal cancer patients. J Radiat Res 2020, 61(5), 766–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartel, D.P. Metazoan MicroRNAs. Cell 2018, 173(1), 20–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004, 116(2), 281-97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qureshi, A. VIRmiRNA: a comprehensive resource for experimentally validated viral miRNAs and their targets.; Database (Oxford), 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, S.; Izaurralde, E. Towards a molecular understanding of microRNA-mediated gene silencing. Nat Rev Genet 2015, 16(7), 421-33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Current status of surgical treatment of rectal cancer in China. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020, 133(22), 2703–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H. MicroRNA: function, detection, and bioanalysis. Chem Rev 2013, 113(8), 6207-33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inui, M.; Martello, G.; Piccolo, S. MicroRNA control of signal transduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2010, 11(4), 252-63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El Fattah, Y.K. CCDC144NL-AS1/hsa-miR-143-3p/HMGA2 interaction: In-silico and clinically implicated in CRC progression, correlated to tumor stage and size in case-controlled study; step toward ncRNA precision. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 253 Pt 2, 126739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakob, M. MicroRNA expression patterns in oral squamous cell carcinoma: hsa-mir-99b-3p and hsa-mir-100-5p as novel prognostic markers for oral cancer. Head Neck 2019, 41(10), 3499–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. Screening of MicroRNA Related to Irradiation Response and the Regulation Mechanism of miRNA-96-5p in Rectal Cancer Cells. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 699475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, I.P. MicroRNAs as Predictive Biomarkers in Patients with Colorectal Cancer Receiving Chemotherapy or Chemoradiotherapy: A Narrative Literature Review. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losurdo, P. microRNAs combined to radiomic features as a predictor of complete clinical response after neoadjuvant radio-chemotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: a preliminary study. Surg Endosc 2023, 37(5), 3676–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asghariazar, V. MicroRNA-143 act as a tumor suppressor microRNA in human lung cancer cells by inhibiting cell proliferation, invasion, and migration. Mol Biol Rep 2022, 49(8), 7637–7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y. miR-145-5p inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition via the JNK signaling pathway by targeting MAP3K1 in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Oncol Lett 2017, 14(6), 6923–6928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozen, M. Overexpression of miR-145-5p inhibits proliferation of prostate cancer cells and reduces SOX2 expression. Cancer Invest 2015, 33(6), 251-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R. miR-145 inhibits tumor growth and metastasis by targeting metadherin in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Oncotarget 2014, 5(21), 10816-29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Effects of hsa-mir-145-5p on the Regulation of msln Expression in Colorectal Adenocarcinoma. Anal Cell Pathol (Amst) 2022, 2022, 5587084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamai, M. microRNA-99a-5p induces cellular senescence in gemcitabine-resistant bladder cancer by targeting SMARCD1. Mol Oncol 2022, 16(6), 1329–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, A.; Bao, X. MiR-99a-5p Constrains Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition of Cervical Squamous Cell Carcinoma Via Targeting CDC25A/IL6. Mol Biotechnol 2022, 64(11), 1234–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, D.; Sharifi, M. Antiproliferative effect of upregulation of hsa-let-7c-5p in human acute erythroleukemia cells. Cytotechnology 2018, 70(6), 1509–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L. Delivery of MicroRNA-let-7c-5p by Biodegradable Silica Nanoparticles Suppresses Human Cervical Carcinoma Cell Proliferation and Migration. J Biomed Nanotechnol 2020, 16(11), 1600–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozammel, N. The Simultaneous Effects of miR-145-5p and hsa-let-7a-3p on Colorectal Tumorigenesis: In Vitro Evidence. Adv Pharm Bull 2024, 14(1), 231–240. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.; Zhao, X.; Ma, L. Downregulation of microRNA-100 correlates with tumor progression and poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cell Biochem 2013, 383(1-2), 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D. miR-100 induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition but suppresses tumorigenesis, migration and invasion. PLoS Genet 2014, 10(2), e1004177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, W. microRNA-100 functions as a tumor suppressor in non-small cell lung cancer via regulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition and Wnt/beta-catenin by targeting HOXA1. Thorac Cancer 2020, 11(6), 1679–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.D. Role of miR-100 in the radioresistance of colorectal cancer cells. Am J Cancer Res 2015, 5(2), 545-59. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, S. MiR-125b-5p Targets MTFP1 to Inhibit Cell Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion and Facilitate Cell Apoptosis in Endometrial Carcinoma. Mol Biotechnol 2023, 65(6), 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.L. The lncRNA XIST/miR-125b-2-3p axis modulates cell proliferation and chemotherapeutic sensitivity via targeting Wee1 in colorectal cancer. Cancer Med 2021, 10(7), 2423–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, N. MicroRNA miR-125b is a prognostic marker in human colorectal cancer. Int J Oncol 2011, 38(5), 1437-43. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. Radiotherapy remodels the tumor microenvironment for enhancing immunotherapeutic sensitivity. Cell Death Dis 2023, 14(10), 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzanakakis, G. Proteoglycans and Immunobiology of Cancer-Therapeutic Implications. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.Y. Potential Predictive Value of TP53 and KRAS Mutation Status for Response to PD-1 Blockade Immunotherapy in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2017, 23(12), 3012–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demaria, S. Radiation dose and fraction in immunotherapy: one-size regimen does not fit all settings, so how does one choose? J Immunother Cancer 2021, 9(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, D. Somatic Mutations and Immune Alternation in Rectal Cancer Following Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy. Cancer Immunol Res 2018, 6(11), 1401–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H. Neoadjuvant therapy alters the immune microenvironment in pancreatic cancer. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 956984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakih, M. High PD-L1 expression and high CD8+T-cell infiltration identifies a new subpopulation of colorectal cancer with high risk of relapse and poor outcome. Annals of Oncology 2017, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Class, C.A. Easy NanoString nCounter data analysis with the NanoTube. Bioinformatics 2023, 39(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, V. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. Elife 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, X. miRDB: an online database for prediction of functional microRNA targets. Nucleic Acids Res 2020, 48(D1), D127–D131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, B.T. DAVID: a web server for functional enrichment analysis and functional annotation of gene lists (2021 update). Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50(W1), W216–W221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| miRNA | Log2FC | T | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|

| hsa-miR-4286 | 4.1 | 12 | 2.1×10-21 |

| hsa-miR-99a-5p | 3.7 | 11 | 2×10-19 |

| hsa-miR-143-3p | 3.5 | 9.1 | 3.6×10-15 |

| hsa-miR-145-5p | 3.3 | 9.3 | 1.6×10-15 |

| hsa-miR-125b-5p | 3.2 | 9.6 | 3.1×10-16 |

| hsa-let-7i-5p | 2.9 | 6.2 | 8×10-9 |

| hsa-miR-1-3p | 2.8 | 7.5 | 1.8×10-11 |

| hsa-miR-100-5p | 2.7 | 8.6 | 4.2×10-14 |

| hsa-miR-199a-5p | 2.5 | 9.2 | 2.4×10-15 |

| hsa-let-7c-5p | 2.4 | 8.5 | 7.4×10-14 |

| miRNA | Estimate | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| hsa-miR-4286 | -0.72111 | 0.39571 |

| hsa-miR-143-3p | -2.90002 | 0.027714 |

| hsa-miR-145-5p | -3.10603 | 0.015049 |

| hsa-miR-99a-5p | -2.85 | 0.015861 |

| hsa-let-7i-5p | -0.20001 | 0.816826 |

| hsa-miR-125b-5p | -2.69999 | 0.009722 |

| hsa-miR-100-5p | -3.25 | 0.002985 |

| hsa-let-7c-5p | -2 | 0.038708 |

| Groups | pre-OP (n=36) | post-OP (n=43) | p-Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 0.277 | ||

| Median (range) | 66 (18-80) | 67 (44-84) | |

| Gender | 0.403 | ||

| Male: Female | 21(58.3): 15 (41.7) | 28 (65.1): 15 (34.9) | |

| Clinical stage at initial diagnosis (cT) | 0.93 | ||

| 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 2 | 3 (8.3) | 3 (7) | |

| 3 | 22 (61.1) | 28 (65.1) | |

| 4a/4b | 11 (30.6) | 12 (27.9) | |

| Clinical stage at initial diagnosis (cN) | 0.907 | ||

| 0 | 4 (11.1) | 5 (11.6) | |

| 1a/1b/1c | 24 (66.7) | 27 (62.8) | |

| 2a/2b | 8 (22.2) | 11 (25.6) | |

| Response to preoperative CRT | 0.986 | ||

| CR/PR | 21 (58.3) | 25 (58.1) | |

| SD/PD | 15 (41.7) | 18 (41.9) | |

| Pathological stage after surgery (ypT) | 0.827 | ||

| 0/Tis | 7 (19.4) | 4 (9.3) | |

| 1 | 3 (8.3) | 4 (9.3) | |

| 2 | 9 (25) | 15 (34.9) | |

| 3 | 15 (41.7) | 18 (41.9) | |

| 4a/4b | 2 (5.6) | 2 (4.6) | |

| Pathological stage after surgery (ypN) | 0.892 | ||

| 0 | 27 (75) | 35 (81.4) | |

| 1a/1b/1c | 6 (16.7) | 5 (11.6) | |

| 2a/2b | 3 (8.3) | 3 (7) | |

| Total RT dose (Gy) | 0.99 | ||

| Median (range) | 50.4 (50.4-60) | 50.4 (50.4-60) | |

| Chemotherapy regimen | 0.986 | ||

| Capecitabine: 5-FU/Leucovorin | 23 (63.9): 13 (36.1) | 25 (58.1): 18 (41.9) |

| Groups | pre-OP (n=8) | post-OP (n=12) | p-Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 0.171 | ||

| Median (range) | 64 (44-76) | 73 (50-77) | |

| Gender | 0.356 | ||

| Male: Female | 4 (50):4 (50) | 9 (75): 3 (25) | |

| Clinical stage at initial diagnosis (cT) | 0.454 | ||

| 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 2 | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0) | |

| 3 | 4 (50) | 7 (58.3) | |

| 4a/4b | 3 (37.5) | 5 (41.7) | |

| Clinical stage at initial diagnosis (cN) | 0.53 | ||

| 0 | 6 (75) | 2 (16.7) | |

| 1a/1b/1c | 1 (12.5) | 7 (58.3) | |

| 2a/2b | 1 (12.5) | 3 (25) | |

| Response to preoperative CRT | 1 | ||

| CR/PR | 4 (50) | 9 (75) | |

| SD/PD | 4 (50) | 3 (25) | |

| Pathological stage after surgery (ypT) | 0.771 | ||

| 0/Tis | 1 (12.5) | 1 (8.3) | |

| 1 | 1 (12.5) | 2 (16.7) | |

| 2 | 3 (37.5) | 6 (50) | |

| 3 | 3 (37.5) | 2 (16.7) | |

| 4a/4b | 0 (0) | 1 (8.3) | |

| Pathological stage after surgery (ypN) | 0.4 | ||

| 0 | 6 (75) | 9 (75) | |

| 1a/1b/1c | 1 (12.5) | 3 (25) | |

| 2a/2b | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Total RT dose (Gy) | 0.613 | ||

| Median (range) | 50.4 (50.4-55.8) | 50.4 (50.4-55.8) | |

| Chemotherapy regimen | 0.648 | ||

| Capecitabine: 5-FU/Leucovorin | 4 (50): 4 (50) | 8 (66.7): 4 (33.3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).