1. Introduction

There is much scientific data regarding the positive effect of combined antiretroviral treatment (cART) on the evolution of HIV infection, with consistent increases in the survival time and quality of life in HIV infected individuals [

1,

2]. Antiretroviral medicines reduce the risk of viral transmission, including between a mother to her child during pregnancy, labor and breastfeeding. Nevertheless, concerns exist regarding the effects of antiretroviral drugs on the off-springs of treated HIV-infected women, more so if the maternal antiretroviral history include a high number of regimens and exposure during puberty. [

3,

4,

5]

The Romanian National Program for HIV Treatment and Prevention started in 2001 provides free of charge HIV testing for pregnant women, efficient antiretroviral regimen for all infected individuals and antiretroviral prophylaxis to all newborns from HIV infected women. Epidemiologic data from Romania published by the Department for monitoring and evaluation of HIV/AIDS infection in Romania show a constant downward trend of vertical transmission rate from 11% in 2010 to 4% in 2015 to 3% in 2024. [

6]

The efficacy of antiretroviral treatment in preventing HIV vertical transmission is reported by numerous clinical studies. A recent systematic review and meta- regression analysis published in September 2025 in Lancet HIV showed the dramatic decrease in HIV vertical transmission since 2013 when World Health Organization (WHO) issued the recommendation of combined antiretroviral treatment (cART) immediately, at any gestational age, during pregnancy and continue for life. [

7].

A systematic review published in 2025 estimated the risk of perinatal vertical transmission with no prophylactic measures at 33.4%, compared to 5.6% in women receiving cART in the last month of pregnancy and 0.3% in those started on cART before pregnancy. In the same time, the efficacy of HIV vertical transmission prevention was not significant different in regard with various antiretroviral regimens analyzed by the review. [

8].

While the crucial importance of antiretroviral drugs in mother to child HIV transmission is well establish, the negative impact on the pregnancy and offsprings is still debated. The panel of experts reviewing the USA approved guidelines for HIV infections updated in June 2025 the recommendations for HIV treatment during pregnancy, and they stated that despite of the fact that many studies assessed the association of antiretroviral drugs and undesirable birth outcomes, like premature delivery, low newborn weight at birth or stillbirth, the results are conflicting, so there is still need for more information in that matter. [

9]

Moreover, several large studies have shown contradictory results on the potential teratogenic effects of antiretrovirals (ARVs) used for prevention of HIV mother to child transmission (PMCT). A large French cohort study including more than 13,000 children exposed to ARVs, followed-up since 1994 showed an association between the use of zidovudine during the first trimester of pregnancy and the incidence of congenital heart defects as well as between the use of efavirenz and the appearance of neural tube defects. [

10]

Other studies, while not identifying any major teratogenic risks associated with the use of ARVs, before and during the pregnancy, signaled a higher risk of prematurity in newborns exposed

in utero to protease inhibitors (PIs). [

11,

12]

The rate of prematurity was also found to be higher in HIV infected pregnant women versus an uninfected group by researchers from Barcelona, although they did not observe a higher rate of complications associated with mitochondrial toxicity, suggesting that HIV by itself is a risk factor for preterm delivery [

13].

An Italian Cohort study from 2014, ICONA Study, found the rates of premature birth to be 11.9% in ARV naïve patients and 22,6% in ARV treated patients, but no association with duration of antiretroviral treatment or with protease inhibitors was observed. [

14]

Nevertheless, in a German Cohort of 183 mother–child pairs the risk of prematurity was 3.4 for PI-based cART exposure during pregnancy, compared with ARV monotherapy and congenital anomalies were found in 3.3% of births. [

15].

The epidemiology of HIV infection in Romania is characterized by the presence of a high number of perinatally infected patients with HIV-1 subtype F [

16,

17] who become sexually active and having their own children. The rate of vertical transmission in Romania remained low, less than 5%, and stable over the last 5 years, mainly due to a National Program for Prevention of Mother to Child HIV Transmission, in place from 2002, which consists of three ARVs, usually a backbone combination of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) with either a boosted protease inhibitor (PI/r) or a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) or an integrase inhibitor (INSTI) administered to the pregnant women from diagnosis, cesarean section delivery, avoidance of breastfeeding and antiretroviral prophylaxis of newborns for 6 weeks after birth. [

18]

The impact of antiretroviral drugs on the offspring from the Romanian cohort of multi-ARV experienced patients was assessed by several studies recently published. One study conducted in Galati County, including 114 in utero antiretroviral exposed newborns identified premature birth in 28.07%, 8.7% significant birth defects and 3 deaths, higher comparative to national or European registry, but similar with reported data in HIV pregnant women from other Romanian Centers Bucharest and Constanta, 19% and 31% respectively. [

19,

20]

In another Romanian study including 408 HIV exposed newborns in two centers Craiova and Constanta evoked high rates of fetal growth restrictions, similar in the studied centers around 50%, higher in HIV positive newborns 55-58% and lower in HIV negative ones 45- 50%. [

21]

The study presented in this paper was aimed to assess the association of preterm delivery and HIV RNA levels in mother at time of birth, the immune status and the duration of antiretroviral treatment at conception

A secondary objective was to identify if there is any correlation between preterm birth and low birth weight in full term babies and the use of antiretrovirals during maternal puberty. The study will add information to a field with limited and controversial data in a country with free access to antiretroviral treatment and free HIV testing for pregnant women. Moreover, this study assessed the risk of prematurity and low birth weight and de maternal antiretroviral history, including during childhood and puberty, aspects not studied yet to the best of our knowledge.

2. Materials and Methods

A retrospective observational study was performed on HIV infected women and their offsprings monitored in two of the largest regional centers for HIV infection in Romania, National Institute for Infectious Diseases “Prof. dr. Matei Bals” Bucharest and Clinical Hospital of Infectious Diseases Constanta.

Ethical Committee approved the study. The informed consent was signed by all the patients or the legal guardians of the patients.

Patients’ assessment conformed to the Romanian National HIV guideline at the moment of diagnosis. [

18] HIV infected women were diagnosed based on ELISA testing, confirmed with Western blot tests, plus a detectable level of HIV RNA prior to cART. Treatment during pregnancy for studied women and the medical care for children was conducted by infectious diseases specialists as individual case managers. [

18]

The final HIV status in HIV exposed children was recorded as HIV infection at first detectable HIV RNA level (viral load or viremia) during the follow up period of 18 months. The uninfected status in HIV exposed children was considered if at 18 months of age the viral load was undetectable without antiretroviral treatment and HIV antibodies tested negative using ELISA and Western Blot tests. The undetermined status was considered in HIV exposed children with no information about viral load at the end of follow up period, but with undetectable HIV RNA without antiretroviral treatment at the last available evaluation. Patients with no information about viral load, ELISA or Western blot results at the end of the study were registered as lost to follow up. All offspring of one mother were included, if they were born within the study period.

The information about the patients was retrieved from medical files, and reflected the common medical HIV care provided in Romania. Data collected included the gestational and maternal age at birth, treatment during pregnancy and duration of cART before pregnancy, as well as newborn gender, birth weight and antiretroviral prophylaxis.

All infants were evaluated at birth and at 3, 6, 12 and 18 months to determine their HIV status.

HIV viral load was determined using the commercial kit COBAS TaqMan HIV-1 Test Version 2.0, Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, NJ, USA; lower detection limit: 20 HIV RNA (viremia) copies/mL The viremia levels were stratify as virologic success less than 50 copies, 50-200 copies/ml, higher than 200 copies/ml. Lymphocytes CD4 levels were stratify as less than 200 cells/mm3, considered severe immunosuppressed, 200- 500 cells/mm3, moderate immunosuppressed and higher than 500 cells/mm3 not immunosuppressed.(7)

Gestational age (GA) was determined based on date of the last period and/or ultrasound measurements of the fetus. If these data were not available, the gestational age was determined using the Ballard scoring system. [

22,

23] It was considered a normal gestational period of 37 to 40 weeks as full term birth (FB) and normal birth weight (NBW) greater than 2500g. Premature birth (PB) was noted if delivery occurred before the end of 37 weeks of gestation or Ballard score was less than 35, low birth weight (LBW) if the new born weighed less than 2500g.

Maternal comorbidities assessed in this study were chronic HBV or HCV infection, illegal drug use, syphilis diagnosis during pregnancy. Type of delivery was stratified as vaginal, planned or necessary cesarean section.

The duration of cART in studied women prior to pregnancy was stratified as: greater than 120 months, 60 to 119 months, 12 to 59 months and less than 12 months. Stratification took into account the maternal mean age from our study and mean age of puberty. [

24]

The regimens used during pregnancy was stratified as NNRTI or PI based combination.

Statistical analysis was done using Epi Info 7 for Microsoft Windows Open Epi, Version 3, open-source calculator from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website at

https://www.openepi.com/Menu/OE_Menu.htm last accessed at 25 November 2025). The Pearson’s chi square test was used to assess the differences between sets of categorical variables and the Mann Whitney test for non-parametric variables. Statistical significance (p) was computed using Fisher test for categorical variables, Student t test and ANANOVA for means and it was considered statistically significant less than 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.1.1. Description of Studied Children

The number of children included in the study was 352. During the study period, 31 women out of 313 had two pregnancies and six out of 313 had three pregnancies. No death among studied women or newborns was recorded.

The characteristics of studied newborns showed balanced distribution by gender, 191 (54.2%) were boys.

The low birth rate in all studied newborns was 25,56% (90 cases out of 352), higher in preterm babies 75%(57 out of 76 cases) compare to full-term babies 12.26% (33 out of 269 cases) as expected.

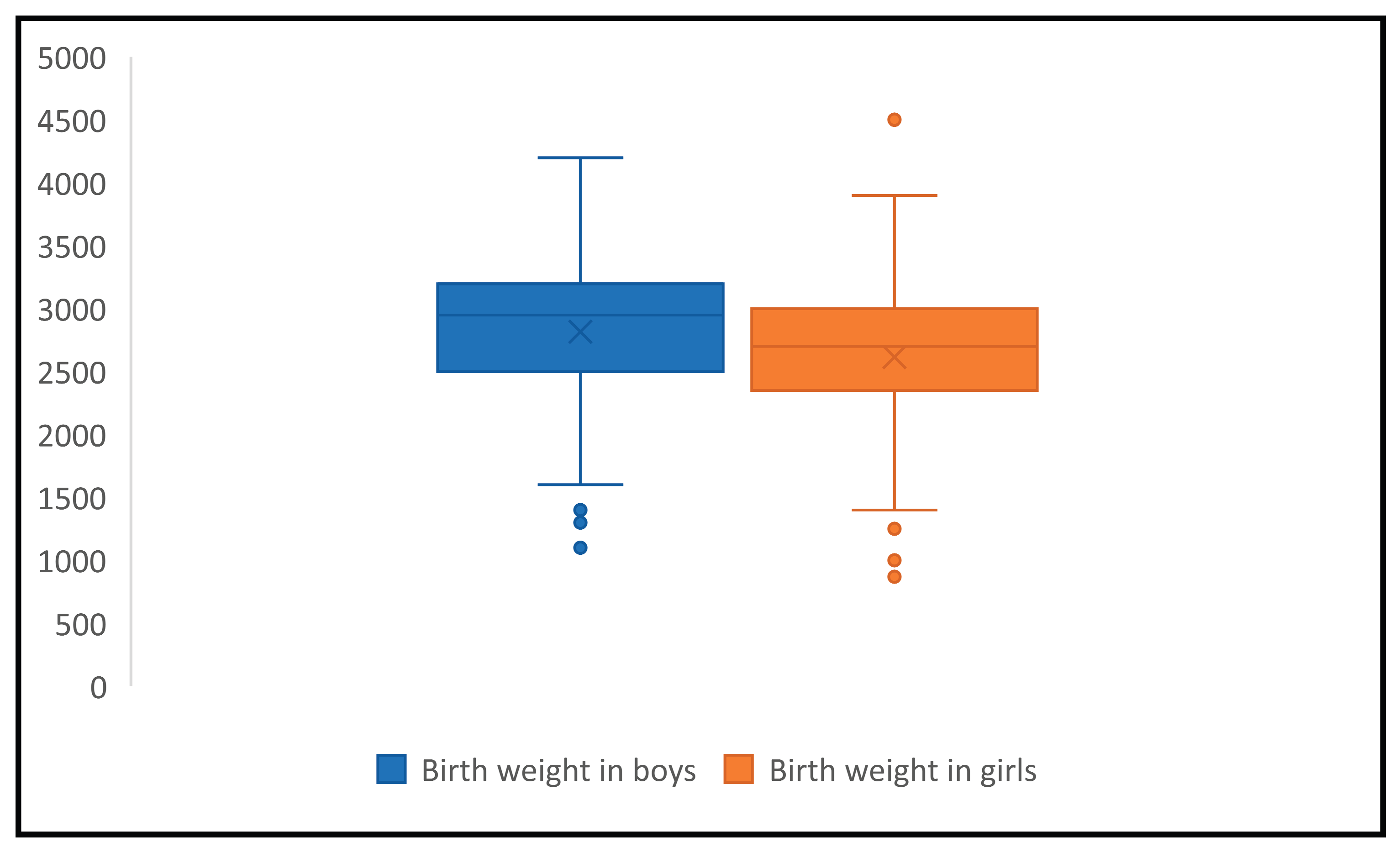

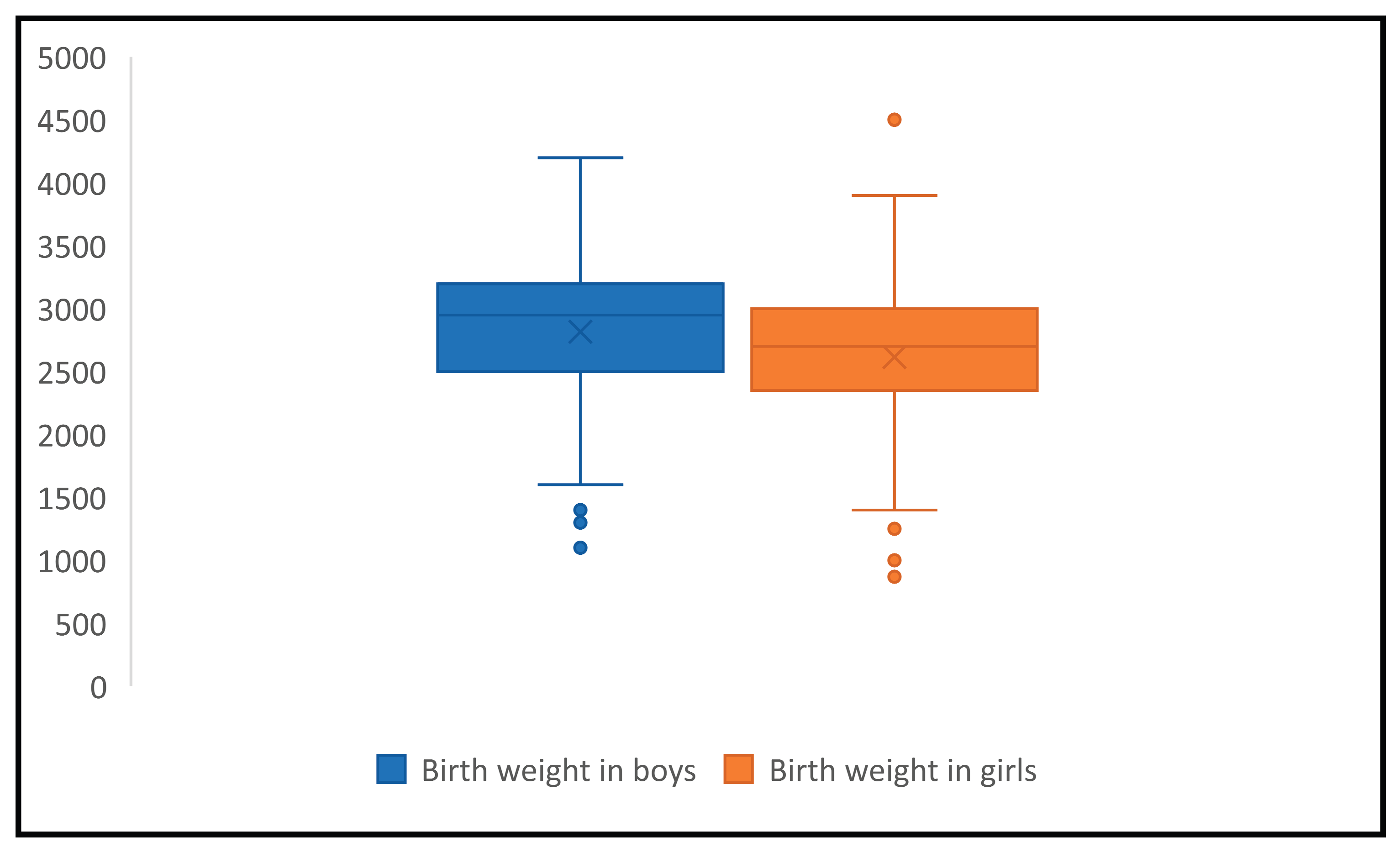

The mean birth weight was 2726g with a standard deviation of ±555g and 95% confidence interval was 2667.8-2784.2. The mean birth weight distribution by gender was 2615g (SD±525, 95% CI:2533.3-2696.7) in girls and 2817g (SD±562, 95% CI 2736.8-2897.2) in boys, the difference was statistically significant (p<0.001), showing that girls are more likely to have lower birth rates, consistent with normal biologic distribution by gender. (Figure 1)

The highest birth weight observed was 4500g in a HIV positive girl, delivered by C section at 40 weeks of gestation by a HIV positive mother diagnosed during delivery, with no comorbidities and no antiretroviral treatment during pregnancy. The lowest recorded birth weight was 870 g in a HIV negative girl delivered at 28 weeks of gestation by a HIV positive mother, diagnosed 5 years before conception, with viral load of 4 log in the last trimester, iv drug user and HCV coinfected, nonadherent to antiretrovirals.

Rate of HIV transmission among studied babies was 13.9%, namely 49 out of 352 enrolled children, but 39 (11%) HIV exposed infants were lost to follow up. Although these infants not evaluated at 18 months of age, had undetectable viral load at the last available determination.

Preterm delivery was recorded in 76 (21.59%) newborns and low birth weight in 91 (25.85%) newborns. Missing data about gestational age was noted in 7 cases (1.98%) and about birth weight in 14 babies (3.97%).

3.1.2. Description of Maternal Characteristics

The mean maternal age at delivery was 23.1 years (Standard Deviation ±4.4 years, 95% confidence interval 22.6-23.5). Most of the women enrolled in the study were diagnosed before conception, 219 out 352 (62.21%), and 185 out of 352 (52.55%) were on antiretroviral treatment before pregnancy.

The viral load in the last trimester of pregnancy was below 50 copies/ml in 81 out of 352 (23.01%) women, 51 to 200 copies/ml was found in 11(3.12%) women, 29 (8.23%) had HIV RNA level between 201 and 1000 copies, 129 (36.64%) had over 1000 copies/ml and in 102 (28.97%) no data about viremia was recorded.

Distribution of CD4 cells levels in the last trimester of gestation in studied women showed CD4 levels below 200 cell/mm3 in 46 out of 352 (13.06%), 123 (34.94%) had CD4 count 200- 500 cell/mm3, over 500 cell/mm3 118 (33.52%) cases, 65 (18.46%) cases had now data regarding CD4 levels in the last trimester of pregnancy.

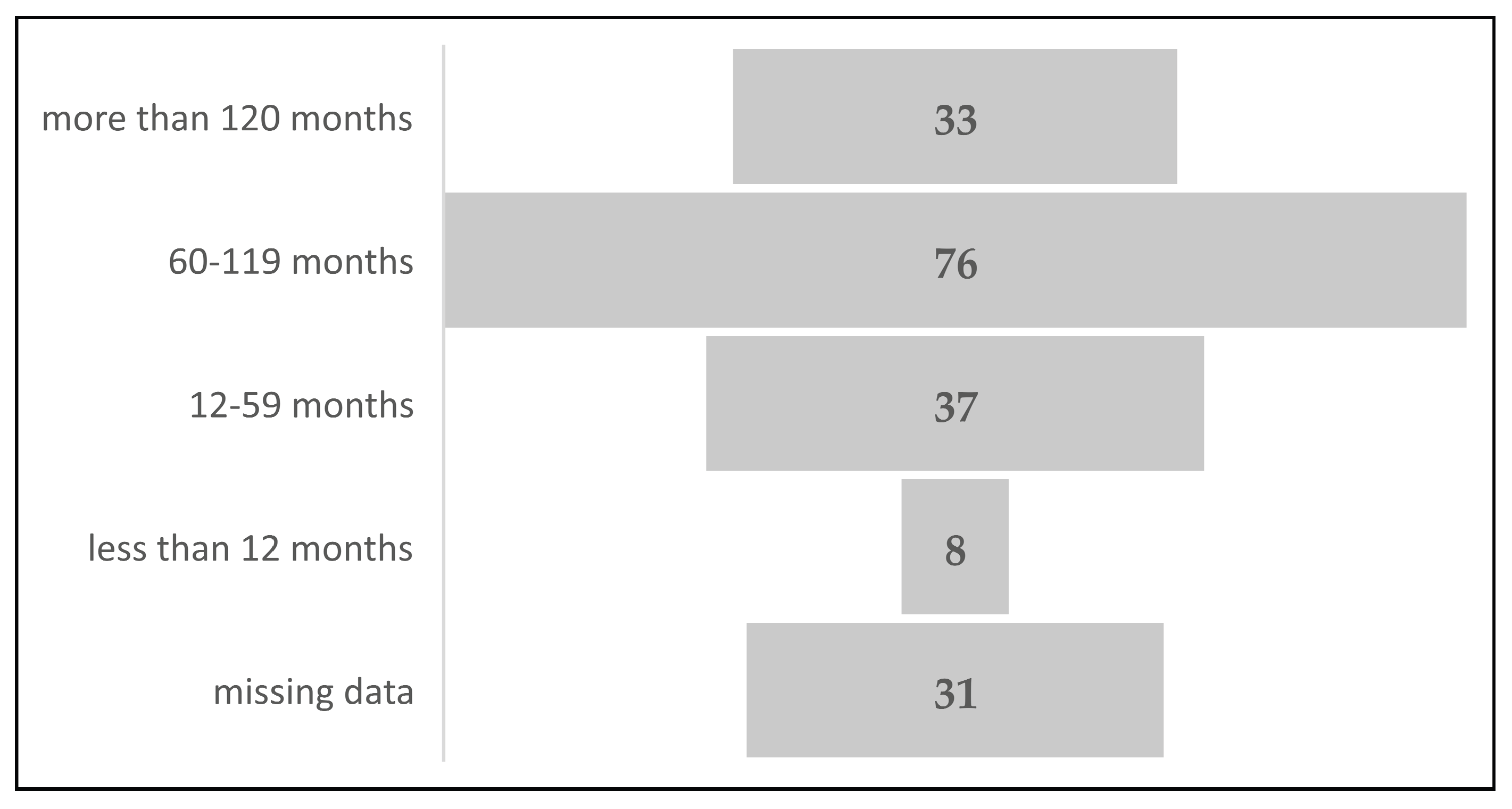

Distribution of maternal cases by cART duration before pregnancy showed that most of the studied women, 76 out of 185 (41.08%), initiated cART between 60 and 119 months before conception, 33 out of 185 (17.83%) had therapy for more than 120 months before conception, 37 (20%) were treated between 12 and 59 months before pregnancy and 8 (4.32%) less than one year before conception. In 31 (16.75%) maternal cases there were no recorded data about timing of cART initiation. (

Figure 2). The longest duration of antiretroviral therapy prior conception was 176 months (almost 15 years), and the shortest was two months.

The mean number of regimens in pretreated studied women was 3 (Standard deviation= SD= 1.376, 95% Confidence interval =95%CI =2.807-3.192, p=0.00614), in overall studied maternal population the mean was 1 (SD= 1.62, 95%CI=0.82 – 1.162 p=0.0062). The highest number of antiretroviral regimens recorded in studied women was seven.

In studied cases, 58 (16.47%) pregnant women started therapy after conception. The total number of newborns exposed newborns being exposed to antiretrovirals in utero was 239 out of 352 (67.89%), and 183 out of 239 (76.56%) from the first trimester. Distribution of the antiretroviral regimen type used during pregnancy in studied patients revealed a predominance of protease inhibitor-based combination, 221 (92.46%) out of 239 cases, only 9 out 239 (3.76%) were non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors- based regimen and 9 out of 239 (3.76%) were combination of PI and NNRTI. In three cases there were two PI used due to switching therapy during pregnancy, from saquinavir to lopinavir (two cases) and darunavir (one case). Finaly, there were 224 exposures to PI and 18 NNRTI.

Analyzing the type of molecules used, in PI class the most used was boosted lopinavir, 165 out of 224 (73.66% ), 12 (5.35%) nelfinavir, 38 (16.96%) cases boosted saquinavir, seven (3.12%) cases boosted darunavir, two (0.89%) cases boosted atazanavir.

The studied newborns were exposed to NNRTI molecules as follows: efavirenz 8 out of 18 (44.44%) cases, nevirapine and etravirine 5 (27.78%) cases each.

The backbone regimens were represented by combination of nucleotide/nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, namely zidovudine plus lamivudine 189 out of 239 (79.07%) cases, abacavir plus lamivudine 25 (10.46%) cases, tenofovir plus lamivudine 5 cases (2.09%), abacavir plus didanosine 8 (3.34%) cases, other combinations 12 (5.02%) cases.

3.1.3. Prematurity Risk Assessment

Univariate analysis was performed to assess the association of prematurity with newborn characteristics, gender and final HIV status, and maternal characteristics: mean age, comorbidities, type of delivery, virologic and immunologic markers, namely HIV RNA and CD4 lymphocytes levels during the last trimester of pregnancy, antiretroviral exposure during pregnancy, duration of maternal antiretroviral treatment before conception, type of antiretrovirals used and timing of cART during gestation. In seven children information about gestational age was missing. The data is presented in

Table 1.

Preterm birth distribution was similar between genders (

X2 (2,352) = 2.081,

p = 0.35) (

Table 1). The final HIV status of the infants was correlated with prematurity,

X2 (4,

N =352) = 18.07,

p = 0.001), meaning that a HIV infected newborn was more likely to be delivered prematurely in studied patients.

In this study, premature newborns were more likely to be associated with vaginal delivery. Otherwise, full - term birth was more likely to be found in cases of planned C section and vaginal delivery (X2 (6, N =352) = 127.3, p < 0.0000001).

Univariate analysis of prematurity association with maternal characteristics revealed that premature delivery was more likely to be found in pregnant women with HIV RNA over 1000 copies/ml in the 3rd trimester of gestation (X2 (8, N =352) =22.13, p =0.004). Timing of HIV maternal antiretroviral therapy before, during pregnancy, at or after birth showed an uneven distribution in studied groups driven by the missing data, so the results did not permit a valid interpretation (X2 (6, N =352) =17.76, p = 0.007).

In studied patients there was no association between prematurity rate and timing of maternal HIV diagnosis, before or after the conception (X2 (4, N =352) =5.25, p = 0.26), maternal immunity status stratified by CD4 count levels (X2 (6, N =352) =11.196, p = 0.08), antiretroviral exposure during first trimester (X2 (6, N =352) =7.16, p = 0.30) or number of antiretroviral regimens in treated studied women (X2 (10, N =352) =9.33, p = 0.50) or maternal comorbidities, namely chronic HBV infection (X2 (2, N =352) =0.51, p = 0.77), chronic HCV infection (X2 (2, N =352) =2.55, p = 0.27), illegal drug use (X2 (2, N =352) =1.02, p = 0.60) or syphilis diagnosis during pregnancy (X2 (2, N =352) =4.25, p = 0.11). Obstetrical complications were noted in two cases of premature delivery and none in full-term delivery group, reveling a statistically significant difference explained by medical plausible association between obstetrical complication and premature birth.

Regarding exposure to antiretrovirals during pregnancy, the statistical analysis showed a significant difference in distribution among studied newborns with no data about gestational age, precluding a meaningful interpretation of the results (

X2 (4,

N =352) =9.77,

p = 0.04). (

Table 1).

In studied women treated before conception (185 cases), there was no association of premature delivery and duration of antiretroviral therapy before pregnancy, stratified as follows: more than 120 months, 60 to 199 months, 12 to 59 months and less than 12 months (X2 (8, N =185) = 7.91, p = 0.44).

The mean duration of maternal treatment before pregnancy in those treated for more than 120 months was 145± 15.6 (95%CI: 138.7-151.2) months in full term babies and 137.9 ±11.8 months (95%CI: 129.1-146.6) in preterm babies, and the difference was not statistically significant (p= 0.19). In a univariate analysis, antiretroviral exposure (stratified as more and less than 120 months) had no impact on prematurity rate (p=0.52,OR 2.6638, Risk Ration1.08, Risk difference 1.77)

The antiretroviral used in pregnancy were stratified in two types of regimens, PI based and NNRTI -based, showing 224 newborn cases exposed to PI and 18 to NNRTI. Data details about therapy were missing in eight cases and in seven cases there was no gestational date recorded. A total of 105 newborns were not exposed to antiretrovirals

in utero. (

Table 2).

The distribution of third antiretroviral drug among studied groups differed significantly, mainly due to missing data about gestational age group, so the results were not interpretable under the chosen model (X2 (6, N =352) = 14.23, p = 0.02).

Further analysis of different PI molecules distribution among studied groups showed no statistically significant difference (

X2 (6,224)= 10.77, p=0.09) (

Table 2). In cases treated with NNRTI based regimens (

X2 (2,15) = 1.2, p=0.54) no relationship of any molecule and preterm birth was found. Regarding the backbone combinations used in cART during pregnancy, no statistically significant difference between preterm and full-term delivery was observed (

X2 (10, 352) = 17.52,

p = 0.06).

3.1.4. Low Birth Weight Risk Assessment in Full- Term Newborns

The body weight at birth was known in 263 out of 269 full term newborns, and 33 newborns ( 12.26%) were small for gestational age and in six cases (2.5%) data about birth weight was missing. The characteristics of patients are detailed in

Table 4.

Low birth weight distribution in full term babies was similar between genders, X2 (2, 269) = 2.78, p = 0.24).

Mean maternal age in overall studied women (269) was 23 years (SD = 4.3916, 95% CI=22.4728-23.5272). In the group of women who have given birth to low birth weight in full term babies was also 23 years( SD = 4.75737, 95%CI = 21.3131-24.6869), as in the groups with normal birth weight in full term babies 23 years (SD = 4.3713, 95%CI = 22.4321 - 23.5679). Overlapping 95%CI in mean maternal age showed no significant differences among means in studied groups confirmed by the t test for variance results, p = 0.67.

In a univariate analysis, low birth weight in full term infants was associated with HIV positive final status (X2 (4, 269) = 11.23, p = 0.02) and lack of maternal cART during pregnancy (X2 (4, 269) = 9.84, p = 0.04). (Table 3)

Maternal chronic HBV infection rate uneven distribution was due to high rate in group with missing data about gestational age, precluding an interpretable conclusion (

X2 (2, 269) = 7.89,

p = 0.01). The other studied maternal comorbidities, chronic HCV infection (

X2 (2, 269) = 1.05,

p = 0.59), illegal drug use (

X2 (2, 269) = 0.77,

p = 0.67) or syphilis diagnosis during pregnancy (

X2 (2, 269) = 2.06,

p = 0.35) were not associated with low nor normal birth weight in studied patients (

Table 4).

The type of delivery, namely vaginal delivery and planned or necessary cesarean section, revealed no significant association with low nor normal birth weight in full-term babies (X2 (6,269) = 9.51, p = 0.14).

The other analyzed variables revealed no statistically significant differences, presented in

Table 4. Maternal HIV diagnosis timing stratified as preconception, during pregnancy and during or after birth computed Pearson

X2 was 1.79, (4, 269),

p = 0.77).

Maternal antiretroviral initiation timing, stratified as preconception, during pregnancy and during or after birth computed Pearson X2 was (6, 269) = 7.55, p = 0.47. Statistical analysis for maternal HIV RNA levels and CD4 count levels found no association with low birth weight in full term delivery (X2 (8, 269) = 6.1, p = 0.63; X2 (6.269)=4.72, p=0.57). Data regarding maternal antiretroviral treatment before conception in terms of duration and number of regimens showed not statistically significant differences among studied groups (low and normal birth weight babies) (X2 (10, 269) = 7.63, p = 0.66 and X2 (10,269)=17.12, p=0.07 respectively).

The mean number of antiretroviral regimens before conception differed significantly among studied groups (test for variance chi square = 21.16, p = 0.00002). This indicated that higher number of regimens before conception was associated with higher likelihood of normal birth weight in full term gestation in studied patients.

Exposure to antiretrovirals during the first trimester of pregnancy was not statistically significant associated with low birth weight (X2 (6, 269) = 5.56, p = 0.27).

Table 5.

Distribution of Type of Antiretroviral Therapy used in Full term babies by birth weight.

Table 5.

Distribution of Type of Antiretroviral Therapy used in Full term babies by birth weight.

| Type of Antiretroviral drug used in pregnancy |

Low Birth Weight

(N=33, 12.26%) |

Normal Birth weight

(N=230, 85.5%) |

Mising birth weight data

(N=6,2.5%) |

Statistical

significance |

Antiretroviral classes of 3rd

drug

PI

NNRTI

Other

None

Total |

21(63.63%)

3(9.09%)

1(3.03%)

8(24.24%)

33(100%) |

145(63.04%)

12(5.21%)

8(3.47%)

65(28.26%)

230(100%) |

2(33.33%)

0(%)

0(%)

4(66.66%)

6(100%) |

0.48

|

Type of PI

Lopinavir/ritonavir

Saquinavir/ritonavir

Nelfinavir

Other PI

Total |

15(65.21%)

2(8.69%)

2(8.69%)

2(8.69%)

23(100%) |

107(73.79%)

8(5.51%)

24(16.55%)

6(4.13%)

145(100%) |

1(16.66%)

1(16.66%)

0(%)

0(%)

2(100%) |

0.19

|

Type of NNRTI

Efavirenz

Nevirapine

Etravirine

Total |

1(33.33%)

1(33%)

1(%)

3(100%) |

3(25%)

6(50%)

3(25%)

12(100%) |

0

0

0

0 |

0.87 |

Type of Backbone

AZT+3TC

ABC+3TC

TDF + 3TC

Other

No

Missing

Total |

18(54.54%)

4(12.12%)

1(3.03%)

2(6.06%)

8(24.24%)

0

33(100%) |

123(53.47%)

18(7.82%)

2(0.86%)

18(7.82%)

66(28.69%)

3(1.30%)

230(100%) |

2(33.33%)

0(%)

0(%)

0(%)

4(66.66%)

0

6(100%) |

0.70

|

PI and NNRTI had similar distribution among studied babies with low and normal birth weight, both classes had same likelihood to be associated with low or normal birth weight ((X2 (6, 269) = 5.442, p = 0.48). A similar result yielded in statistical analysis regarding specific PI molecules (boosted lopinavir, boosted saquinavir, nelfinavir) (X2 (6,168) = 8.56, p = 0.19) or NNRTI molecules ( nevirapine, efavirenz, etravirine) (X2 (2,15) = 0.2679, p = 0.87) or backbone combinations (X2 (10,269) = 7.17, p = 0.70).

4. Discussion

The rate of HIV vertical transmission noted in this study, of 13.9%, was higher than reported mother to child transmission for the same period at national level around 9% and discordant with data reported from other Romanian center, with a rate of vertical transmission ranging from 5.4% to 6.97%.[

18,

25] These discrepancies could be explain by the study design and selection criteria, the addressability to study sites and regional differences in patients access to National Program for mother to child HIV transmission prevention. [

20]

The rate of preterm birth in our study population was 21.5%, 2.2 times comparative with European and Romanian average data (around 10%) in general population in the same time period.[

26] This suggests the need for more efficient strategies to improve the medical and nursing care of HIV pregnant women to be able to assist this type of patient. Similarly high rates of premature birth have been reported in other HIV cohorts: Italian Cohort- 22.6% versus 11.9 % in uninfected women- data published in 2014 and in a US based cohort of 1869 newborns the rate of premature delivery was 18,6% where it was associated with use of protease inhibitors-based cART. [

12,

14]

In this study, in univariate analysis the preterm birth rate was associated with HIV transmission in studied newborns and with high levels of maternal HIV RNA in last trimester suggesting, suggesting that lack of viral replication control was a predictor factor for preterm delivery.

The role of HIV replication and advanced HIV diseases in birth outcomes, like prematurity and low birth weight has been noted in previous studies. Schulte and collaborators assessed trends of prematurity and low birth weight in 11231 infants during five years, 1998-2004, showing a decrease of low birth weight’s rate in infants from 35% to 21% and prematurity rate from 35% to 22%, while the use of antiretrovirals in pregnant women increased from 2% to 97%. They concluded that maternal use of illegal drugs, unknown maternal HIV status before delivery, symptomatic maternal infection before delivery and HIV infection in infants was associated with low births weight and prematurity. Those results were similar with data observed in our study. [

27]

In the above-mentioned study prematurity was associated with lack of cART during pregnancy and the use of protease inhibitor regimen, while our results found no relationship with any antiretroviral regimen. This discordance in the results can be explained by the study design, retrospective versus longitudinal, selection criteria, patients addressing to two major centers, comparative to pediatric consortium covering multiple sites number of studied patients, 358 versus 11321 and study period six years (2006-2012) versus 14 years (1989 till 2004). [

27]

A study published in 2014 by Slyker and colleagues found similar results with our study, showing a correlation between detectable maternal HIV RNA levels and prematurity risk, with odds ratio (OR) of 1.8. In the same tine this study showed an increased prematurity rate of 3.3 times associated with less than 15% CD4 percent, while in our study the data showed no relationship with CD4 levels. Those differences can be explained by the differences in inclusion criteria, namely HIV infected infants were included in our study, but excluded in Slyker’s study. [

28]

Our study was the first to assess the impact on birth outcome in women exposed to antiretrovirals since childhood, including during puberty.

Nevertheless, duration of therapy prior pregnancy or class of ARV, protease inhibitors nor NNRTI, used in our country during pregnancy, were not associated with higher rate of preterm delivery or low birth weight in newborns exposed to maternal cART. A study of the Swiss Cohort comprising 1180 pregnancies, with a rate of preterm birth of 15.8% before 1994 and 28% after 1998 also showed no relationship between the duration before delivery and rate of premature birth, but the mean age of studied women was 29 years, comparatively higher than our study population.[

29]

Another study included 183 women of mean age of 28 years; the prevalence of babies small for gestational age was 31.2% at the 10th and 12.6% at the 3rd percentile and was not associated with starting treatment before pregnancy.[

30]

More recent studies carried out in France published in 2021 found preterm birth around 14% in INSTI treated pregnant women.[

31] Comparing those results to median European of preterm birth rate around 5% (5 moderate and late preterm birth in 100 live births), ranging from 4% to7.65%, the rate was still two times higher in French HIV cohort, even with newer antiretroviral drugs, INSTI.[

32]

Similar data as in French cohort was published in AIDS in 2022 from a study conducted in South African Republic including 991 pregnant women, showing a rate of 14.% preterm birth in HIV exposed but noninfected newborns comparing to 9.8% in HIV negative pregnant women.[

33] In the same time, in the South African study, the low birth weight’s rate was higher in HIV exposed compare to unexposed infants, 14.3% versus 11.4%, the difference being more important in very low birth weight, 3.7% versus 1.57%.

A metanalysis published in 2023 showed uncertainties in connection with preterm delivery and relation to antiretrovirals, despite the fact that relation to protease inhibitors exposure, mainly lopinavir/ritonavir during pregnancy was proved by many studies. Newer protease inhibitors, like darunavir- ritonavir, had limited data regarding the safety during pregnancy. The same issues were found by the beforementioned metanalysis for timing of the cART initiation and relation with premature birth and low birth weight. [

34] The authors conclude that there was not clear association between different antiretroviral regimens, including the newer one based on integrase inhibitors, and prematurity and low birth weight, clinicians should continue to monitor and report any adverse events in HIV pregnant women.

In our study, the rate of low birth weight in HIV exposed children was 12.26% in full-term newborns. In univariate analysis, low birth weight rate in studied patients was associated with HIV positive final status and lack of maternal antiretroviral treatment during pregnancy, suggesting the same important impact of HIV on fetal growth. These results are similar with those mentioned before, published by Shulte and collaborators. [

27]

The impact of antiretroviral drugs on birth outcome and birth weight was found to be less important than the impact of HIV infection on maternal health. In the same time, low birth weight in full term newborns was not associated with HCV coinfection and illegal drug use in pregnant women. Our results differed from a metanalysis and systematic review published in 2022 in Lancet by Cowdell and collaborators showing that PI based regimens were associated with high risk of small for gestational age (SGA). The different results could be explained by the retrospective design of our study and inclusion criteria of the patients and possible regional particularities, matanalisys included numerous studies from different geographical regions. [

35]

The underlying mechanism implicated in explaining the excess of premature birth in treated pregnant women is the impact of antiretroviral drugs on mitochondrial DNA and immunomodulation. The results of a study on mitochondrial DNA (mitDNA) in exposed infants showed surprising data. Levels of mitDNA from peripheral monocytes (PBMC) were higher in ARV exposed versus ARV unexposed children. [

36] Immunomodulation associated antiretroviral treatment is characterized by increased production of IL2, which is favorable for controlling the HIV disease but unfavorable for pregnancy maintenance. [

37]

The factors implicated is preterm birth in HIV treated women are probably more complex and further randomized and large studies are needed for a better description of those mechanisms.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that in pregnant women that have lived with HIV from their early childhood and are multi - drug experienced, prematurity was mainly associated with the level of viral replication during the last trimester of pregnancy and HIV vertical transmission. Low birth weight in newborns was associated with lack of antiretroviral treatment during pregnancy and HIV transmission. The study results suggest that HIV itself plays a greater role in birth outcome in comparison with antiretroviral therapy, irrespective of the treatment duration and number of regimens before conception, nor exposure throughout puberty in future mothers.

Antiretroviral therapy represents the corner stone of prevention for HIV vertical transmission by effectively suppressing viral replication; long term exposure to ARV does not influence the birth outcomes.

Monitoring the pregnancy and good access to HIV prevention program are the main issues that have to be address in Romania. The rate of very low birth weight in studied patients, must be a concern, but the solution is to improve the quality of medical care for HIV infected women at fertile age.

Several limitations of this study have to be taken into account: the design as a retrospective observational study, the relatively low number of patients studied, the absence of information concerning other maternal conditions that can impact on birth outcome like tobacco and alcohol use.

Nevertheless, these results provide useful information from real world settings, in an aria of medical care still on debate, making difficult to develop of appropriate guidelines for Romania, and other countries with similar epidemics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.T and S.C.C.; methodology, A.M.T, S.C.C., C.T.; formal analysis, A.M.T, S.C.C., L.M.S and C.T.; investigation, A.M.T., S.C.C., C.A.V; resources, A.M.T, S.C.C., L.M.S., C.T., C.A.V.; data curation, A.M.T, S.C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.T., S.C.C, S.M.R; writing—review and editing, A.M.T., S.C.C, V.A., S.M.R.; visualization, V.A., S.M.R.; supervision, S.M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Ethic Committee of our Hospital approved access to patients’ data. Since our research is an observational retrospective study, we did not need a special agreement from Ethic Board.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting our research published here are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The paper is published with support from the program” Publish not Perish” run by the University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Carol Davila”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Boulle A, Schomaker M, May MT, et al. Mortality in Patients with HIV-1 Infection Starting Antiretroviral Therapy in South Africa, Europe, or North America: A Collaborative Analysis of Prospective Studies. Binagwaho A, ed. PLoS Medicine. 2014;11(9): e1001718. [CrossRef]

- Trickey, A., Zhang, L., Gill, M. J., Bonnet, F., Burkholder, G., Castagna, A., Cavasini, M., Circhon, P., Crane, H., Domingo, P., Grabar, S., Guest, J., Obel, N., Psichogiou, M., Rava, M., Reiss, P., Rentsch C.T., Riers, M., Schhuettfort, G., Silverberg, M.J., Smith, C., Stecher, M., Sterling, T.R., Ingle, S.M., Sabin, C.A., Sterne, J. A. (2022). Associations of modern initial antiretroviral drug regimens with all-cause mortality in adults with HIV in Europe and North America: a cohort study. The Lancet HIV, 9(6), e404-e413.

- Cohen, M. S., McCauley, M., & Gamble, T. R. (2012). HIV treatment as prevention and HPTN 052. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS, 7(2), 99-105.) ( Njom Nlend, A. E. (2022). Mother-to-child transmission of HIV through breastfeeding improving awareness and education: a short narrative review. International journal of women's health, 697-703.

- Hampanda, K., Pelowich, K., Chi, B. H., Darbes, L. A., Turan, J. M., Mutale, W., & Abuogi, L. (2022). A systematic review of behavioral couples-based interventions targeting prevention of mother-to-child transmission in low-and middle-income countries. AIDS and Behavior, 26(2), 443-456.) WHO. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT): situation and trends. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

- Mofenson LM, Lambert JS, Stiehm ER, et al. Risk factors for perinatal transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in women treated with zidovudine. Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study 185 Team. N Engl J Med. Aug 5 1999;341(6):385-393.

- Märdärescu, M.; Cibea, A.; Petre, C.; Neagu-Drãghicenoiu, R.; Ungurianu, R.; Petrea, S.; Tudor, A. M.; Vlad, D.; Matei, C.; Alexandra, M. ART management in children perinatally infected with HIV from mothers who experience behavioural changes in Romania. Journal of the International AIDS Society 2014, 17 4 Suppl 3, 19700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach June 2013. In Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach June 2013; 2013; pp. 272–272. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, M. K.; Bulterys, M. A.; Barry, M.; Hicks, S.; Richey, A.; Sabin, M.; Louden, D.; Mahy, M.; Stover, J.; Glaubius, R.; Kyu, H. H.; Boily, M. C.; Mofenson, L.; Powis, K.; Imai-Eaton, J. W. Probability of vertical HIV transmission: a systematic review and meta-regression. The lancet. HIV 2025, 12(9), e638–e648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinicalinfo. HIV.gov Recommendations for the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs During Pregnancy and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States. Available online: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/perinatal/recommendations-arv-drugs-pregnancy-regimens-maternal-neonatal-outcomes (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Sibiude, J.; Mandelbrot, L.; Blanche, S.; Le Chenadec, J.; Boullag-Bonnet, N.; Faye, A.; Dollfus, C.; Tubiana, R.; Bonnet, D.; Lelong, N.; Khoshnood, B.; Warszawski, J. Association between prenatal exposure to antiretroviral therapy and birth defects: an analysis of the French perinatal cohort study (ANRS CO1/CO11). PLoS medicine 2014, 11(4), e1001635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, C. L.; Cortina-Borja, M.; Peckham, C. S.; de Ruiter, A.; Lyall, H.; Tookey, P. A. Low rates of mother-to-child transmission of HIV following effective pregnancy interventions in the United Kingdom and Ireland, 2000-2006. AIDS (London, England) 2008, 22(8), 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, D. H.; Williams, P. L.; Kacanek, D.; Griner, R.; Rich, K.; Hazra, R.; Mofeson, L.; Mendez, H.A. for the Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study Combination antiretroviral use and preterm birth. The Journal of infectious diseases 2013, 207(4), 612–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, S.; Moren, C.; Lopez, M.; Coll, O.; Cardellach, F.; Gratacos, E.; Oscar, M.; Garrabou, G. Perinatal outcomes, mitochondrial toxicity and apoptosis in HIV-treated pregnant women and in-utero-exposed newborn. Aids 2012, 26(4), 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- d'Arminio Monforte, A; Galli, L; Lo Caputo, S; Lichtner, M; Pinnetti, C; Bobbio, N; Francisci, D; Costantini, A; Cingolani, A; Castelli, F; Girardi, E; Castagna, A. ICONA Foundation Study Group. Pregnancy outcomes among ART-naive and ART-experienced HIV-positive women: data from the ICONA foundation study group, years 1997-2013. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014, 67(3), 258–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosch-Woerner, I.; Puch, K.; Maier, R.; Niehues, T.; Notheis, G.; Patel, D.; Casteleyn, S.; Feiterna-Sperling, C.; Groeger, S.; Zaknun, D. and for the Multicenter Interdisciplinary Study Group Germany/Austria (2008), Increased rate of prematurity associated with antenatal antiretroviral therapy in a German/Austrian cohort of HIV-1-infected women. HIV Medicine 9, 6–13. [CrossRef]

- Paraschiv, S.; Otelea, D.; Dinu, M.; Maxim, D.; Tinischi, M. Polymorphisms and resistance mutations in the protease and reverse transcriptase genes of HIV-1 F subtype Romanian strains. International journal of infectious diseases 2007, 11(2), 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojevic, M.; Alexiev, I.; Beshkov, D.; Gokengin, D.; Mezei, M.; Minarovits, J.; Otelea, D.; Paraschiv, S.; Poliak, M.; Zidovec-Lepej, S.; Paraskevis, D. HIV1 molecular epidemiology in the Balkans: a melting pot for high genetic diversity. AIDS Rev 2012, 14(1), 28–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Compartment for Monitoring and Evaluation of HIV/AIDS Infection in Romania INBI “Prof.Dr. M. Balş”. Available online: www.cnlas.ro (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Arbune, M.; Calin, A. M.; Iancu, A. V.; Dumitru, C. N.; Arbune, A. A. A Real-Life Action toward the End of HIV Pandemic: Surveillance of Mother-to-Child HIV Transmission in a Center from Southeast Romania. Journal of clinical medicine 2022, 11(17), 5020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor, A. M.; Mărdărescu, M.; Petre, C.; Drăghicenoiu, R. N.; Ungurianu, R.; Tilișcan, C.; Oțelea, D.; Cambrea, S. C.; Tănase, D. E.; Schweitzer, A. M.; Ruță, S. Birth Outcome in HIV Vertically Exposed Children in Two Romanian Centers. Germs 2015, 5(4), 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambrea, S. C.; Dumea, E.; Petcu, L. C.; Mihai, C. M.; Ghita, C.; Pazara, L.; Badiu, D.; Ionescu, C.; Cambrea, M. A.; Botnariu, E. G.; Dumitrescu, F. Fetal Growth Restriction and Clinical Parameters of Newborns from HIV-Infected Romanian Women. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania) 2023, 59(1), 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupea, I. Tratat de Neonatologie, ediţia a 4-a; Ed.Medicală Universitară “Iuliu Haţieganu”: Cluj-Napoca, 2005; p. 235. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard Score Calculator. Available online: https://perinatology.com/calculators/Ballard.htm (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Sadrzadeh, S; Klip, WAJ; Broekmans, FJ; Schats, R; Willemsen, WNP; Burger, CW; Van Leeuwen, FE; Lambalk, CB. Birth weight and age at menarche in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome or diminished ovarian reserve, in a retrospective cohort. Hum Reprod. 2003, 18, 2225–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambrea, S. C.; Marcu, E. A.; Cucli, E.; Badiu, D.; Penciu, R.; Petcu, C. L.; Dumea, E.; Halichidis, S.; Pazara, L.; Mihai, C. M.; Dumitrescu, F. Clinical and Biological Risk Factors Associated with Increased Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV in Two South-East HIV-AIDS Regional Centers in Romania. Medicina 2022, 58(2), 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeitlin J, Mohangoo AD, Delnord M, the EURO-PERISTAT Scientific Committee(2013); The second European Perinatal Health Report: documenting changes over 6 years in the health of mothers and babies in Europe J Epidemiol Community Health 2013;67:983-985. https://insp.gov.ro/download/cnepss/stare-de-sanatate/determinantii_starii_de_sanatate/siguranta_pacientului/Analiza-de-Situatie-Siguranta-Pacientului-2021.pdf.

- Schulte, J; Dominguez, K; Sukalac, T; Bohannon, B; Fowler, MG. Declines in low birth weight and preterm birth among infants who were born to HIV-infected women during an era of increased use of maternal antiretroviral drugs: pediatric spectrum of HIV disease, 1989–2004. Pediatrics 2007, 119(4), e900–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slyker, J.A.; Patterson, J.; Ambler, G.; et al. Correlates and outcomes of preterm birth, low birth weight, and small for gestational age in HIV-exposed uninfected infants. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudin, C.; Spaenhauer, A.; Keiser, O.; Rickenbach, M.; Kind, C.; Aebi-Popp, K.; Brinkhof, M. W. Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS), & Swiss Mother & Child HIV Cohort Study (MoCHiV) (2011). Antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy and premature birth: analysis of Swiss data. HIV medicine 12(4), 228–235. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aaron, Erika; Bonacquisti, Alexa; Mathew, Leny; Alleyne, Gregg; Bamford, Laura P.; Culhane, Jennifer F. Small-for-Gestational-Age Births in Pregnant Women with HIV, due to Severity of HIV Disease, Not Antiretroviral Therapy. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2012, 135030, 9 pages. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibiude, Jeannea,b; Le Chenadec, Jérômec; Mandelbrot, Laurenta,b; Dollfus, Catherined; Matheron, Sophieb,e; Lelong, Nathalief; Avettand-Fenoel, Véroniqueg,h,i; Brossard, Maudc; Frange, Pierrei,j; Reliquet, Véroniquek; Warszawski, Josianec,l,m; Tubiana, Rolandn,o. Risk of birth defects and perinatal outcomes in HIV-infected women exposed to integrase strand inhibitors during pregnancy. AIDS 35(2):p 219-226, February 2, 2021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, L.; Philibert, M.; Scott, S. Socio-Economic Inequalities in Stillbirth and Preterm Birth Rates Across Europe: A Population-Based Study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2025, 132(no. 13), 2168–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Kima; Kalk, Emmaa; Madlala, Hlengiwe P.b; Nyemba, Dorothy C.a.b; Kassanjee, Reshmaa; Jacob, Nishac; Slogrove, Amyd; Smith, Mariettea,e; Eley, Brian S.f; Cotton, Mark F.g; Muloiwa, Rudzanih; Spittal, Graemei; Kroon, Maxj; Boulle, Andrewa,c,e; Myer, Landonb; Davies, Mary-nna,c,e. Increased infectious-cause hospitalization among infants who are HIV-exposed uninfected compared with HIV-unexposed. AIDS 2021, 35(14), p 2327–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eke, A. C.; Mirochnick, M.; Lockman, S. Antiretroviral therapy and adverse pregnancy outcomes in people living with HIV. New England Journal of Medicine 2023, 388(4), 344–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowdell, I; Beck, K; Portwood, C; et al. Adverse perinatal outcomes associated with protease inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy in pregnant women living with HIV: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine Published 2022 Apr 6. 2022, 46, 101368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldrovandi, GM; Chu, C; Shearer, WT; et al. Antiretroviral Exposure and Lymphocyte mtDNA Content Among Uninfected Infants of HIV-1-Infected Women. Pediatrics 2009, 124(6), e1189–e1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiore, S.; Ferrazzi, E.; Newell, M.-L.; Trabattoni, D.; Clerici, M. Protease inhibitor-associated increased risk of preterm delivery is an immunological complication of therapy. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2007, 195(6), 914–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).