1. Introduction

Modern educational platforms use recommender systems to generate personalised learning experiences through automatic recommendations of suitable courses and learning materials for their users. The systems enhance user interaction through personalised content delivery that matches individual preferences and achievement levels. Da Silva et al. [

3] identify recommender systems as essential elements for contemporary educational technology systems. The analysis of large personal and behavioral data sets in recommender systems generates multiple security risks that affect user privacy. The storage of user information in centralised databases for traditional recommender systems generates two major security threats because it creates single points of failure and raises the risk of data breaches. Deschenes[

4]; Urdaneta-Ponteet al[

32]. The protection of user data through privacy systems has become essential because these systems need to preserve recommendation accuracy. The traditional recommendation systems use three main methods which include collaborative filtering and content-based filtering and their combination[

3]. The methods have achieved notable success in enhancing user interaction but they need extensive data collection through centralised systems. The centralised nature of these systems creates security risks because educational datasets contain sensitive student information including academic records and personal interests and behavioural data. do not stop users from being identified or their data from being misused. Federated learning operates The existing privacy protection strategies, such as data encryption and user anonymisation, do not fully ensure protection. They serve as encryption techniques that permit model training without revealing user information to centralised data storage systems. The training process occurs on user devices but the model parameters and update information get transmitted to a central server for consolidation[

31] The system architecture maintains user data within devices which protects privacy through reduced exposure to unauthorised access[

7]. The original mobile data protection purpose of FL at Google has led to successful deployments in healthcare and financial sectors which need strong privacy protection. The system protects user information effectively while achieving the best possible model performance[

32]. The educational recommender system domain requires extensive Learner information yet FL remains underutilised for this purpose. The deployment of FL technology for educational platforms faces multiple technical challenges which must be solved to achieve operational readiness. The distributed architecture of FL generates substantial computational requirements for client devices which makes model consolidation operations more complex[

16]. The scientific community has not found a solution to achieve identical model performance across different devices and network environments. The technical obstacles require additional research to develop FL-based frameworks which will preserve educational recommendation accuracy in restricted conditions and dynamic environments. The paper presents an FL-based recommender system which fulfills educational platform requirements through strong privacy protection mechanisms that preserve recommendation accuracy. The system stores user information on personal devices which reduces security threats while generating individualised recommendations with high accuracy. The research solution enables users to maintain their privacy rights while obtaining precise recommendations through its proposed solution. The research examines three vital elements of FL deployment in educational systems which evaluate performance against privacy tradeoffs and system deployment complexities and decentralised system benefits against centralised models.

The research develops a privacy-focused educational platform recommender system through federated learning which it evaluates for privacy and security and recommendation quality performance. The research evaluates the performance of the proposed federated model against traditional centralised recommender systems to establish their operational differences. The research findings will help developers construct educational platforms which safeguard user privacy for contemporary data-intensive educational settings.

The paper structure begins with Section two which reviews current research about recommender systems and privacy protection techniques. The system design section explains how federated learning technology operates in Section three. The experimental findings appear in Section four before Section five presents the analysis of results. The paper ends with Section six which presents future research paths and summarises the main research discoveries.

2. Literature Review

Digital systems across entertainment and e-commerce and educational domains heavily depend on Recommendfer Systems (RS) for their operations. Educational systems depend on RS to create individualised learning routes and suggest educational content which enhances student participation through data-driven analytical methods. The systems use user behavioral data including interaction records and performance statistics to generate preference forecasts for content delivery. The online learning platforms Coursera and edX and Udemy employ RS to show users relevant courses and materials which optimise both user satisfaction and system performance. Educational recommender systems primarily employ three main recommendation methods which include CF and content-based filtering and their combination through hybrid approaches. The implementation of these techniques leads to better personalisation and user interaction but their success rate depends on centralised data storage systems which create major privacy and security risks.

2.1. Privacy Concerns in Traditional Recommender Systems

All user information including personal details and learning records and performance metrics exists in centralised storage systems of traditional systems. The system provides simple data management but exposes users to major privacy and security threats because educational institutions handle sensitive information including student grades and demographic data. The centralised data collection method creates a security risk because it establishes a single entry point which hackers can use to gain access and steal data for illegal activities. The growing number of data protection laws including GDPR and FERPA requires developers to create new systems which protect user privacy while maintaining accurate personalisation results. The development of federated learning technology offers a solution to address privacy issues which centralised recommender systems create.

Federated Learning (FL) is a decentralised machine learning paradigm where models are trained locally on user devices rather than being centrally trained in data centers. Each device trains a model with its private data and communicates only the model updates (e.g., gradients) with a central aggregator to build the global model. In this paradigm, Hu et al.[

10] present a method that allows collaboration in learning while not transferring raw data, in turn providing much-enhanced privacy protection.

In educational applications, FL allows the development of recommendation models that are able to learn from distributed datasets (e.g., students’ learning history and performance) without needing direct sharing of data, as stated by Javeed et al.[

12]. The approach ensures that sensitive information, regarding academic performance and personal preferences, stays confined to users’ local environments. More recently, Jalalirad et al.[

11] have illustrated that FL allows one to perform training on decentralised, user-specific data in order to enhance collaborative filtering with high precision while preserving privacy. Besides, FL can be combined with other privacy-enhancing techniques, such as differential privacy, secure multi-party computation, and homomorphic encryption, to enhance data confidentiality. Such combinations make FL a strong candidate for privacy-aware recommender systems in compliance with privacy regulations including GDPR and FERPA.

2.2. Applications of Federated Learning in Educational Platforms

2.2.1. Personalised Learning and Course Recommendation

FL has been evidenced to support effective personalised education without privacy violations by generating customised learning recommendations. In fact, it enables federated recommender models to analyse learners’ behaviors locally to recommend courses or materials according to learners’ progress and preferences, keeping personal data undisclosed[

30].

2.2.2. Privacy-Preserving Educational Data Analytics

Federated learning has also facilitated privacy-preserving analytics across institutions. It allows the performance evaluation at scale without the need for centralizing sensitive academic data. Fachola et al.[

6] have underlined that local training on the institutional servers or student devices facilitates distributed analytics while mitigating risks of exposure. This is all the more significant as student data breaches regarding confidential personal and academic records are becoming frequent[

27].

2.2.3. Real World Implementations

Real-world examples further validate the potential of FL for privacy-conscious systems. Google Research demonstrated the effectiveness of FL in mobile keyboard personalisation, improving model performance with the typing data of millions of users without sharing raw inputs[

14,

24]. Similarly, Zhang et al.[

27] have shown that FL models estimate learner engagement and recommend courses in e-learning platforms while keeping confidential student records. These collectively establish that FL is an effective solution for preserving privacy and is adaptable to the educational context.

2.3. Technical Challenges and Limitations of Federated Learning

The technical implementation of federated learning faces multiple obstacles which affect its operation. The system performance and model convergence will suffer from device capability differences and network stability issues and data distribution patterns according to McMahan et al.[

33]. The system faces additional bandwidth constraints because model parameter exchanges between clients and servers need to happen more frequently in educational settings with limited bandwidth according to Kairouz et al.[

13].

The model update exchange process in FL systems exposes privacy information to indirect leaks even though it protects against centralised data breaches. The addition of secure aggregation and differential privacy features would enhance privacy protection but these mechanisms would require additional computational resources and result in reduced model performance. The actual implementation of FL in under-resourced educational facilities faces barriers because of insufficient hardware resources and insufficient technical expertise and inadequate infrastructure.

2.4. Comparative Analysis and Research Gap

The evaluation between traditional and federated recommender systems reveals fundamental distinctions regarding data management practices and privacy protection and system scalability. Traditional systems maintain better computational performance and operational control yet their centralised data storage makes them susceptible to security breaches. The decentralised approach of federated systems protects user privacy better than traditional systems because it distributes data processing tasks which results in enhanced compliance with data protection regulations. The system requires optimization to achieve optimal performance because decentralization leads to reduced computational speed and increased communication requirements.

The FL framework has achieved success in healthcare and finance and distributed systems but there is limited research about its application in educational recommender systems. The current research focuses on either technical aspects of FL or educational RS without uniting these two fields. The current research lacks a complete framework which assesses the three essential factors of FL suitability and system performance and privacy protection mechanisms in educational networks.

The research requires development of a privacy-protecting federated recommender system which serves educational needs to achieve equilibrium between privacy protection and system scalability and recommendation quality. The development of privacy-focused personalised learning systems enables educational institutions to build secure digital frameworks that respect data privacy.

3. Methodology

This paper proposes a methodology for effective performance of FL in an educational recommender system, while ensuring robust data privacy. It combines theoretical insights and practical implementation to derive an answer to the following core research question:

RQ: How can FL be effectively applied in educational recommender systems while guaranteeing data privacy?

It was done by following a deductive approach, where established principles of FL and privacy-preserving computation were extended to the educational domain. The specific methodology entailed a series of successive steps: literature review, design of system architecture, data collection and preprocessing, implementation of the model, integration with a recommender system, and system evaluation. The systematic approach transforms theoretical principles into operational methods which generate protected recommendations that maintain privacy and deliver precise results.

The initial phase requires evaluation of existing FL research together with privacy protection methods including DP and SMC and educational recommender systems from Hu et al.[

10] and Javeed et al.[

12]. The review process will enable system design by showing the benefits and weaknesses and unaddressed issues of using FL with protected educational information. The evaluation process will benefit from this knowledge because it will determine which models to use and which privacy methods to implement and which performance indicators to measure.

3.1. System Design and Implementation

The system development will follow a modular structure which includes four essential parts: system architecture and data collection and preprocessing and model implementation and collaborative filtering recommender engine integration. The system components follow a design that protects privacy

while preserving recommendation accuracy and ensuring operational suitability for educational settings.

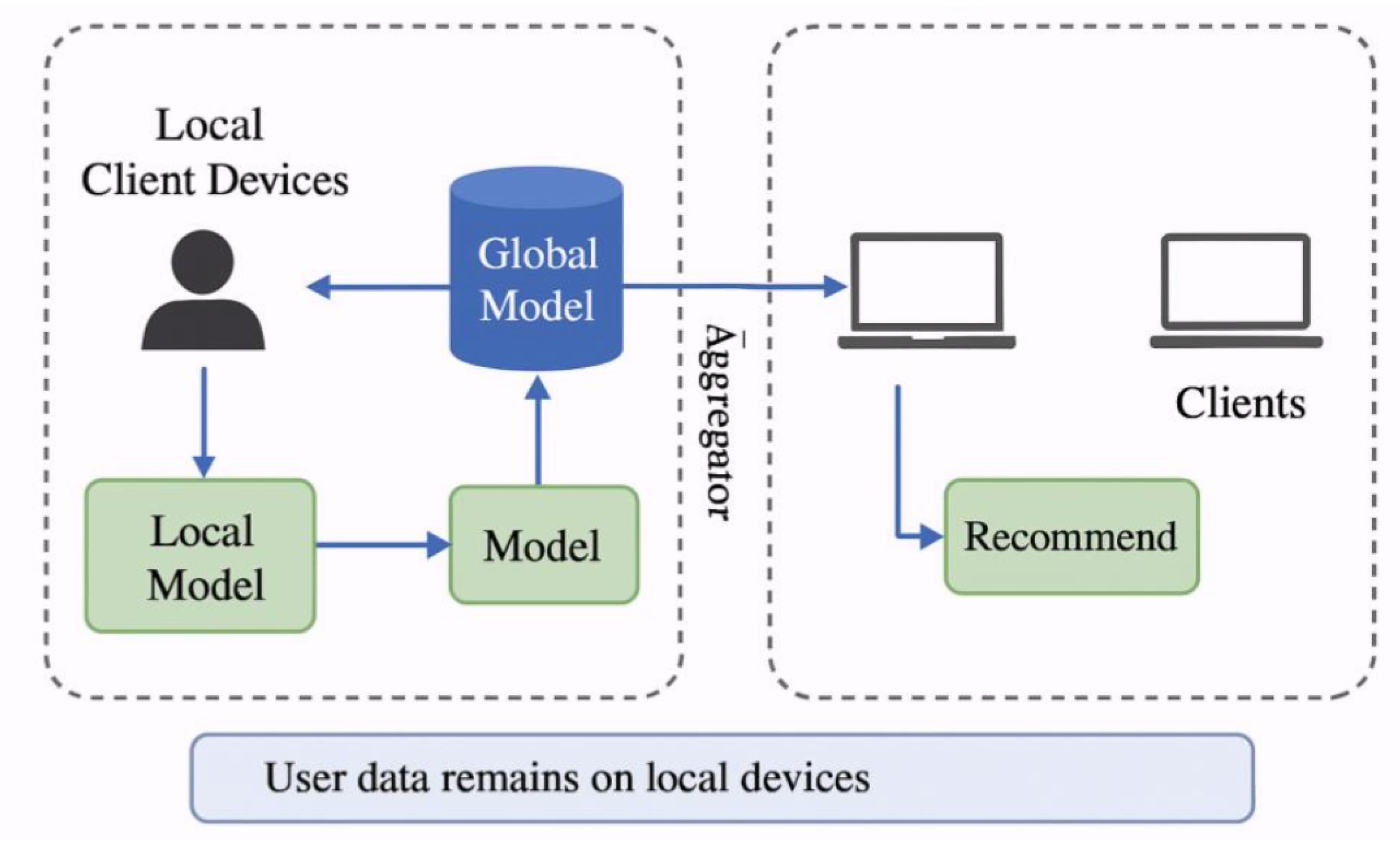

3.1.1. System Architecture

Figure 1 shows our system design. It follows Federated Learning principles because it keeps all user data locally on devices while sending only model weight updates to a central server for global model creation. The system protects user privacy through decentralised computation according to Hu et al.[

10] because it uses both encryption and anonymization methods. The system design achieves both excellent privacy protection and effective recommendation performance through its optimised client-side computation requirements..

The framework demonstrates a federated learning system which enables local client devices to train recommendation models independently from their user data. The central aggregator receives model weight updates from clients to create an enhanced global model. The global model update gets distributed to all participating devices which use it to create individualised recommendations through local processing without revealing user information. The recommendation process maintains privacy through all stages because user data remains protected.

3.2. Data Collection and Preprocessing

The training of models uses publicly accessible educational data from Kaggle (

https://www.kaggle.com) while evaluation data comes from four major online learning platforms which include edX and Skillshare and Udemy and Coursera. The datasets contain user interaction records and course information and preference signals and academic achievement metrics.

The training process starts by eliminating all records that contain missing or corrupted information while maintaining data privacy through standard anonymization protocols. The preprocessing pipeline performs data cleaning followed by normalization and missing value imputation and feature engineering to convert categorical data into numerical formats for federated model training.

The virtual client nodes distribute the datasets to create separate learning platform representations which mimic distributed learning environments.

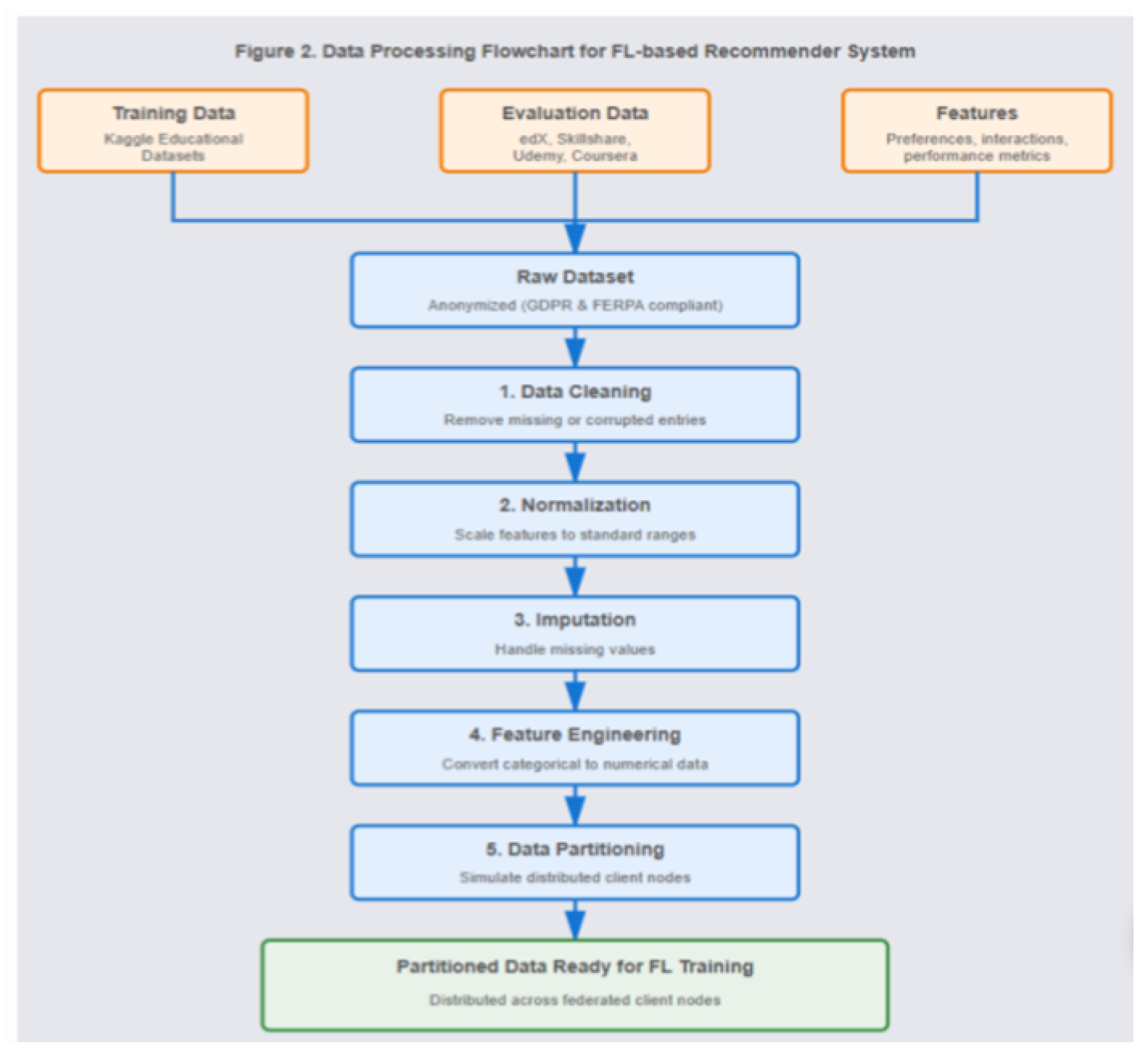

Figure 2.

Data Preprocessing flowchart for FL-based recmmender system.

Figure 2.

Data Preprocessing flowchart for FL-based recmmender system.

The figure demonstrates the automated data processing sequence which educational datasets must undergo before federated learning becomes operational. Thea while simultaneously gathering user information through their preferences and their interactions with courses and their academic achievement records. system collects training data from Kaggle and evaluation data from edX, Skillshare, Udemy and Courser The raw dataset undergoes five consecutive preprocessing operations which start with data cleaning to eliminate faulty records followed by normalization for feature scale standardization and imputation for missing value handling and feature engineering for categorical to numerical conversions and end with data partitioning for client node simulation. The datasets undergo anonymization to fulfill GDPR and FERPA privacy requirements. The processed information gets distributed between federated clients for independent model training operations.

3.3. Model Implementation

Model development is performed in Python using the TensorFlow Federated (TFF) framework, supporting the training of models across client devices in a distributed manner without requiring the centralization of user data. Consequently, each client device will independently perform model training, yielding model weight updates that the clients securely transfer to a central server. The server combines these model weight updates to obtain the globally updated model, where personally identifiable information is never disclosed throughout this entire process.

3.3.1. Integration with the Recommender System

After deployment, the federated model consistently develops personalised course recommendations through a recommendation system based on Collaborative Filtering. CF works based on user-item similarities, and it can be especially useful in educational domains because learning is much influenced by peers. See TEM Journal, May 2024, pp. 1352–1361.

We employ matrix factorization using SVD on the sparse matrix of user-item interactions. This is achieved by decomposing a sparse user-item interaction matrix into two lower-dimensional latent factor matrices of user and item features. In the federated setting, this factorization is run locally on each client device, while only model parameters aggregated across the different devices are transmitted to the server. In particular, this design preserves data privacy while allowing high-quality recommendations.

3.4. Evaluation and Testing

The system’s effectiveness is assessed along two primary dimensions: recommendation accuracy and privacy preservation.

3.4.1. Performance Evaluation

Model evaluation is done using Mean Squared Error (MSE) and R-squared (R2) metrics

MSE basically measures the average of the squared deviation between the predicted and observed values, hence it yields a measure of the predictive accuracy for variables like course ratings.

R2 describes the proportion of variation accounted for by the model and thus indicates overall fit.

For recommendation quality, precision, recall, and F1-score are computed:

Precision is the ratio of recommended courses that are relevant.

It determines the ratio of relevant courses retrieved.

F1-score provides a balanced measure of performance by calculating the harmonic mean of precision and recall.

3.4.2. Privacy Evaluation

Controlled privacy attack simulations are conducted to detect potential vulnerabilities during model training and aggregation to assess the system’s robustness in terms of privacy. Comparing the proposed work to classical, centralised recommender systems through experiments, their resistance to data leakage is measured quantitatively. The refinements of the model parameters are done based on empirical results for better privacy protection with high accuracy and recommendation quality.

4. Result

4.1. Dataset Overview

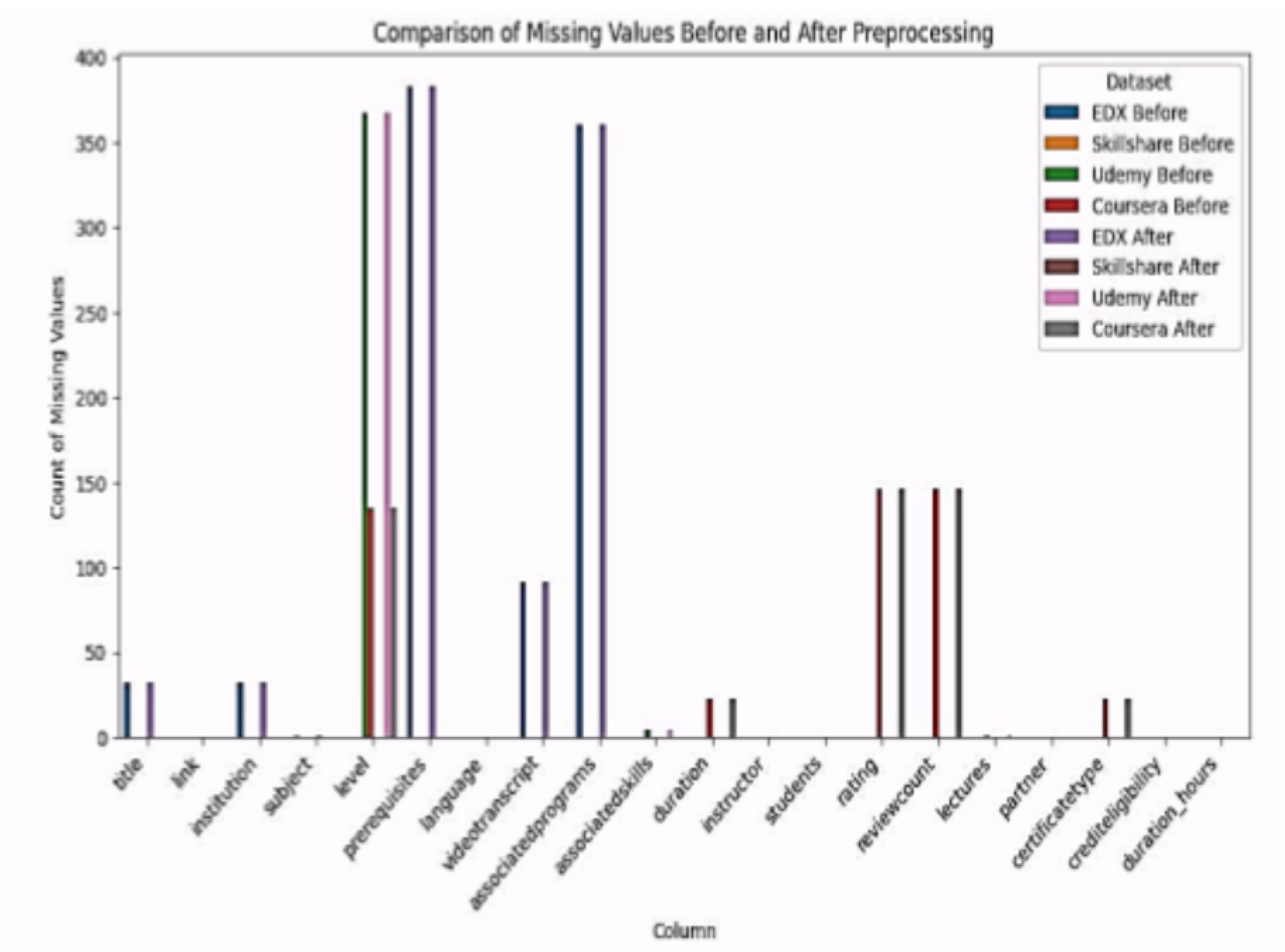

The datasets used in this paper are from four leading online learning platforms: edX, Skillshare, Udemy, and Coursera. The data mainly consists of course interactions, user ratings, and their corresponding skills. After preprocessing, the final number of entries in the dataset was 42,461. Plot

Figure 3 displays a comparison of the dataset before and after preprocessing to show the decrease in missing and invalid values.

4.2. Federated Learning Model Performance

The federated learning model was evaluated for its ability to predict course durations while keeping user data local. As presented in

Table 1, the model produced a MSE of 94.78, indicating a substantial deviation between predicted and actual course durations. The R

2 value was -0.688, suggesting that the model explained very little of the variance in course durations and performed worse than a simple baseline predicting the mean.

4.3. Collaborative Filtering Performance

Table 2 shows the performance of the CF recommender system. The precision of 1.0 indicates that all courses recommended to users were relevant. However, the extremely low recall and F1 score suggest that the system failed to recommend relevant courses for the majority of users. In other words, the recommendations it did make were very accurate, but the system covered only a small portion of all the courses that could be relevant, hence the low overall coverage of recommendations.

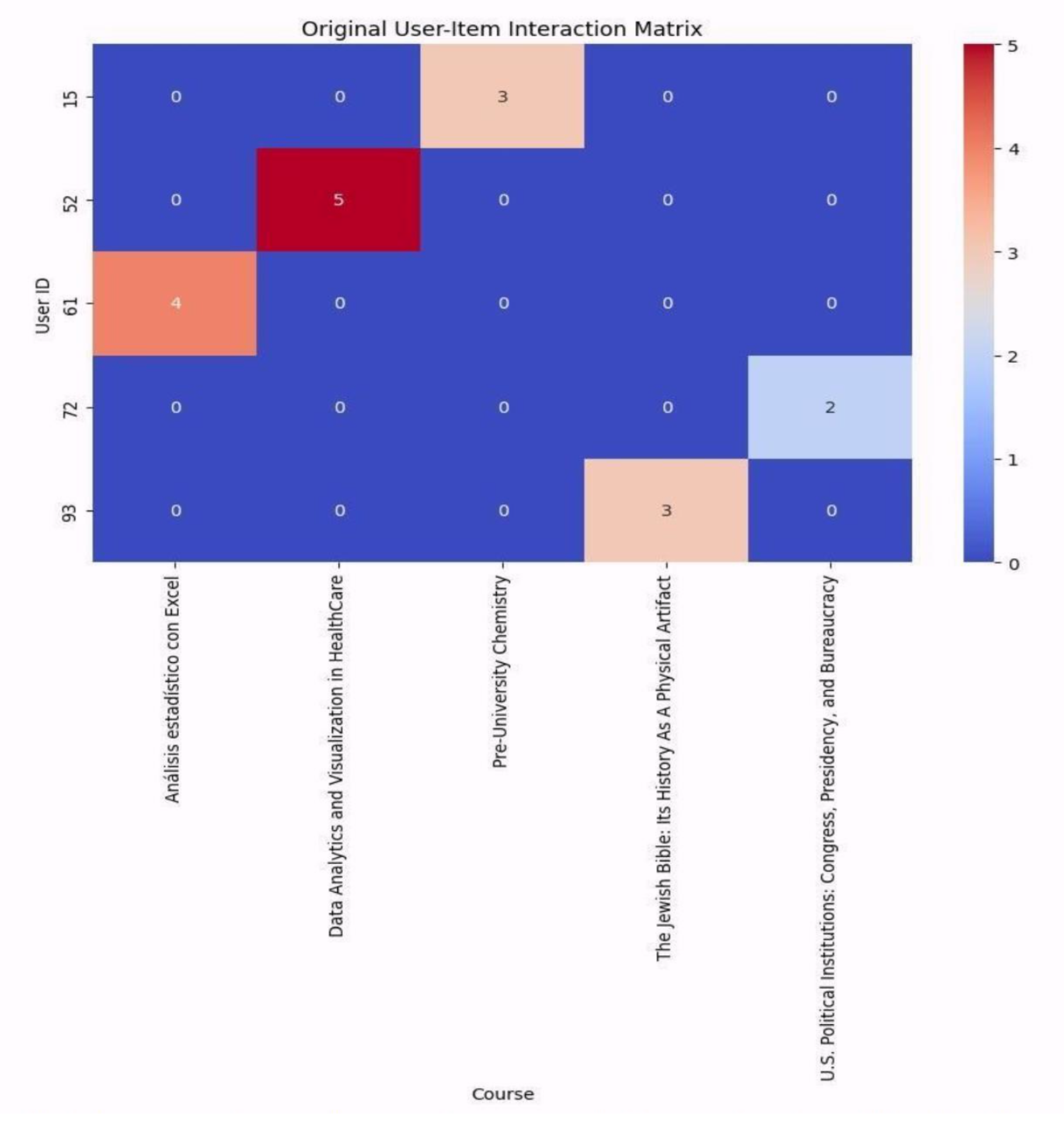

4.4. Visualization of User-Item Interaction Matrix

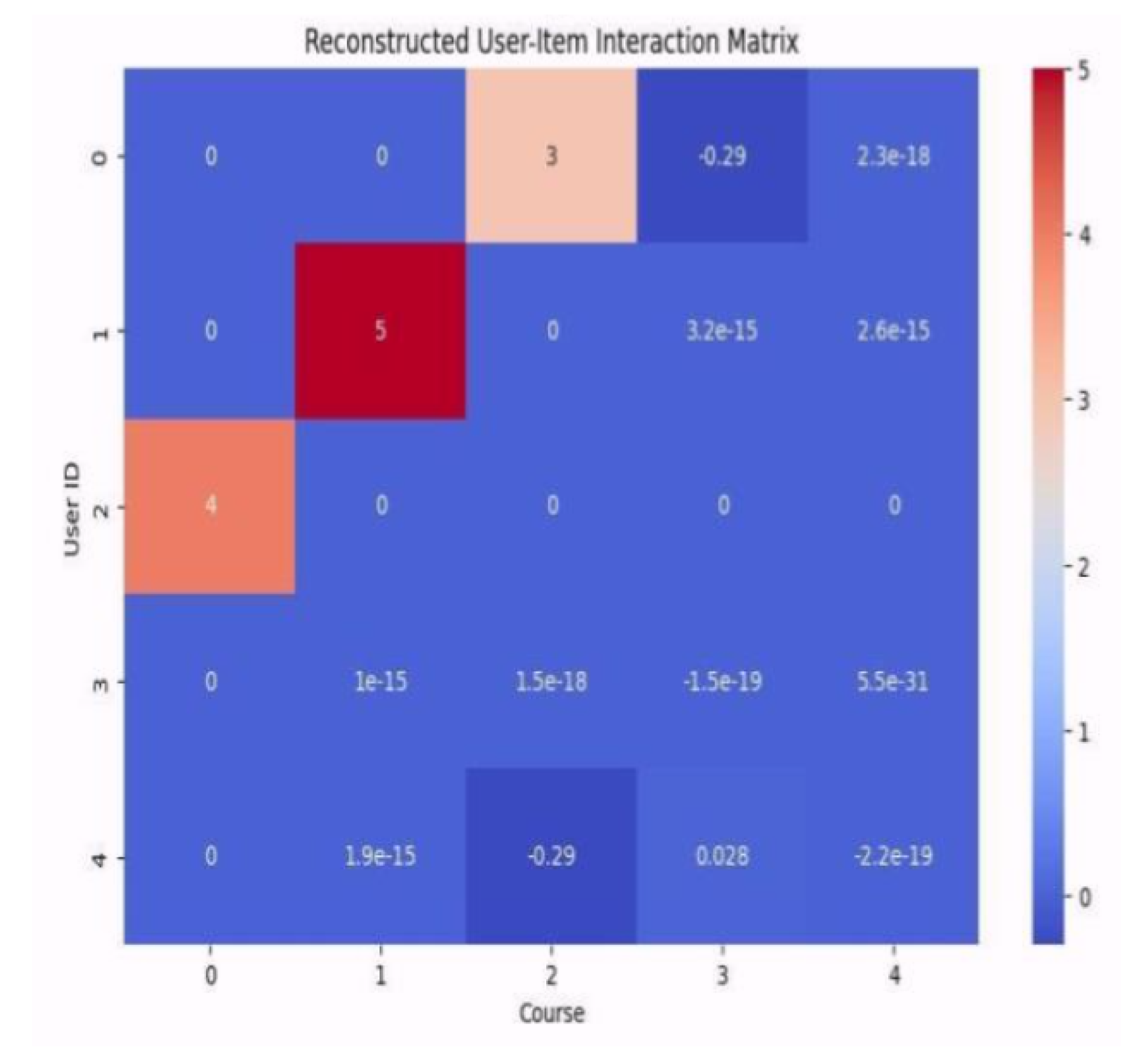

Figure 4 demonstrates the classical user-item interaction matrix is depicted, showcasing the original ratings of users for available courses. Each row represents one user, every column corresponds to one course, and each entry in the matrix denotes the extent of user engagement or preference.

Figure 5 demonstrates our reconstructed matrix after matrix factorization. This heatmap shows how collaborative filtering algorithms fill in missing data based on latent features of users and items, predicting preferences for unobserved interactions.

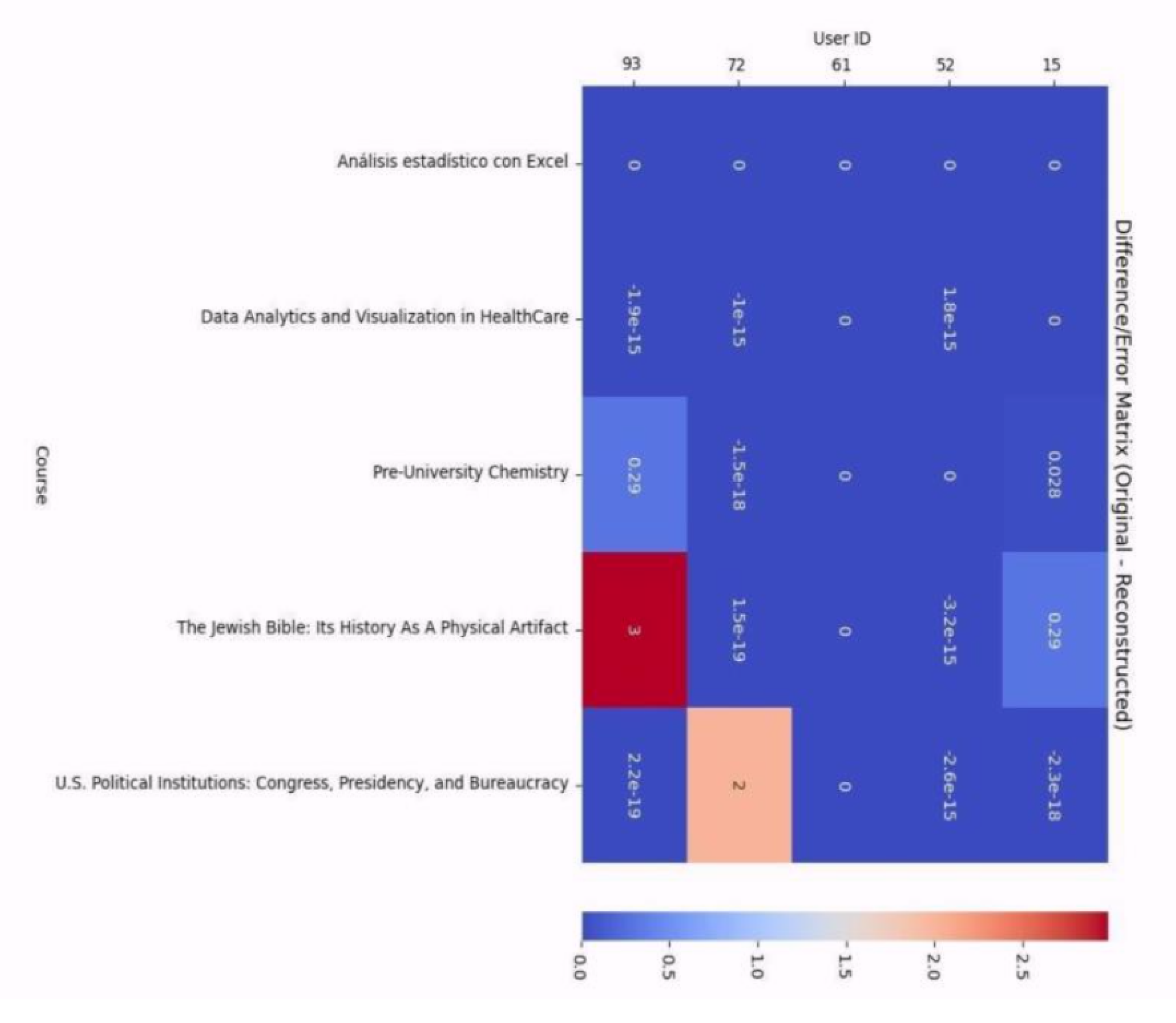

Figure 6 displays the error matrix, or the difference between the original and reconstructed matrices. Darker shades in this heat map correspond to larger prediction errors in user-item interactions, thus showing areas where the estimates of the model are furthest from the actual interactions.

These visualizations together give an insight into the performance of the collaborative filtering model, both in capturing the underlying patterns of user preference and the limitations in reconstructing all interactions accurately.

4.5. Recommendation Evaluation

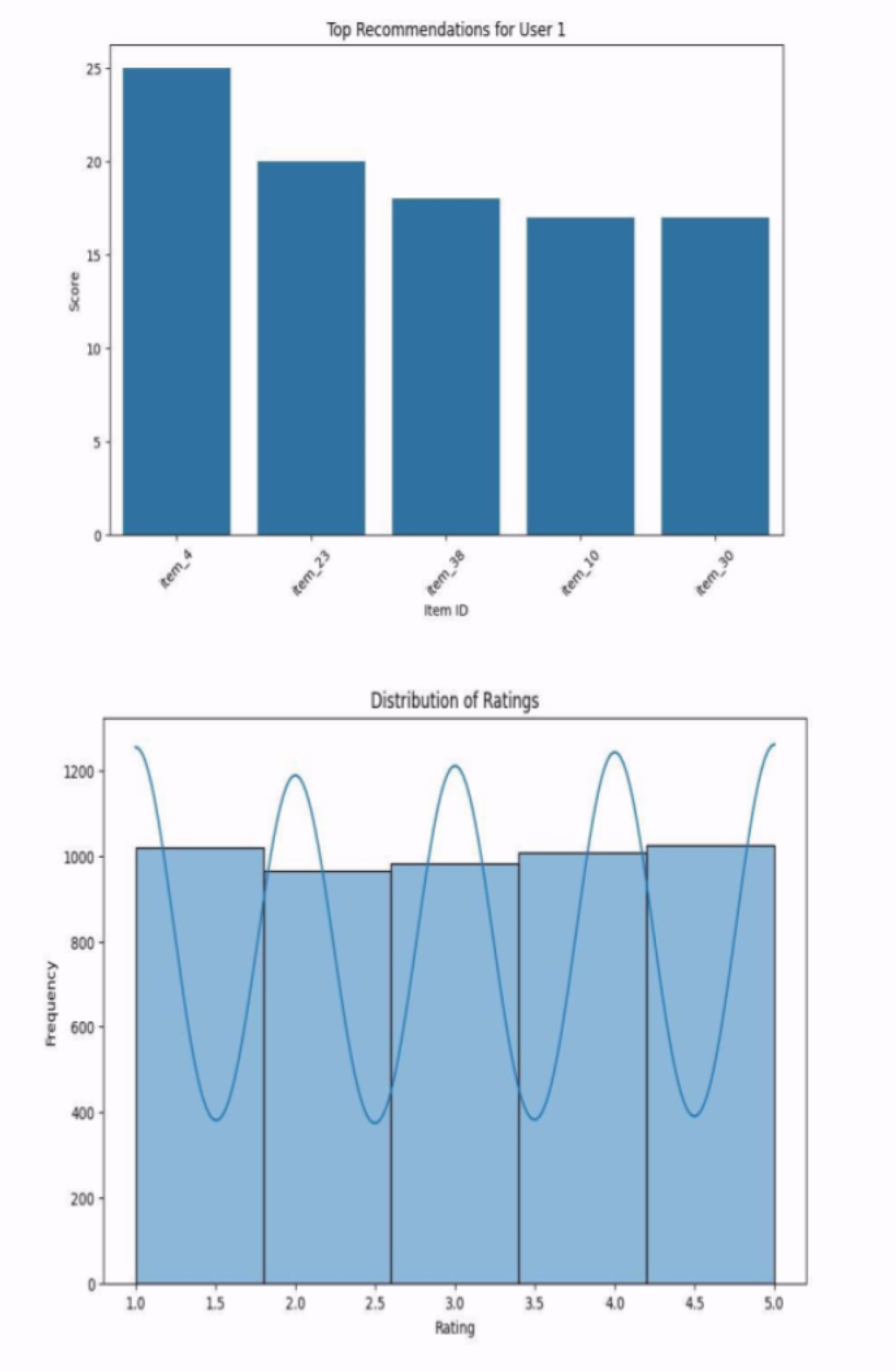

The system recommendation quality assessment included an evaluation of personalised course suggestions which the system generated for individual users. Plot

Figure 7 shows the system’s ability to identify user preferences through its selection of top courses for a particular user. The system demonstrated strong prediction abilities through its effective course recommendation process according to the bar plot. The system produced highly relevant suggestions but the precision and recall and F1 score metrics revealed that some users received restricted recommendations which could lead to future algorithm enhancement work.

5. Discussion

The research examined how federated learning operates with educational recommendation systems, while studying the potential for private recommendation delivery. The study reveals essential factors which affect the real-world implementation of federated methods for this specific application.

5.1. Performance-Privacy Trade-Offs

The experimental findings demonstrate that user data privacy remains protected through federated learning yet this protection results in decreased predictive accuracy. The model produces a Mean Squared Error of 94.78 and a negative R-squared value of -0.688. The data show that course duration prediction faces an extremely challenging task. The decentralised system design protects user data through local device storage, yet it causes model convergence to slow down and produces higher prediction errors when working with limited or unrepresentative user data. The research findings of Kairouz et al[

13] support this statement. The research by Papadopoulos et al.[

18] demonstrates that federated models perform worse than centralised models when using identical experimental conditions.

The accuracy of centralised recommenders exceeds that of decentralised systems because they use complete user population data to build models from uniform and extensive datasets[

8]. The method exposes users to major privacy risks because it needs them to share their personal learning preferences and behavioral data. The educational data processing needs of student information make federated learning an attractive solution for educational platforms. The trade-off between accuracy and privacy protection seems acceptable because our results show better privacy protection even though they perform worse than centralised models.

5.2. Precision, Recall, and Coverage Limitations

The collaborative filtering system achieved perfect precision at 1.0 but it generated recommendations for only 0.015% of users while maintaining an F1 score of 0.0296. The system generates highly relevant recommendations but it only recommends items to a tiny percentage of users. The system faces a problem with recommendation coverage instead of recommendation quality. The system observes individual device data through sparse user-item interaction matrices which exist in federated environments. The system fails to recognize patterns between users because of sparse data which results in poor F1 scores and recall performance. Mishra et al.[

17] established that federated collaborative filtering faces a core problem because each client node can only access restricted data. The system produces restricted recommendations which lack diversity because it fails to understand the preferences of its active users. The system requires improved algorithms which focus on handling unbalanced data distribution between different nodes in the network. Research should focus on developing methods to extract knowledge from limited local data while maintaining user privacy protection.

5.3. Comparison with Centralised Approaches

The federated learning system we implemented demonstrates lower overall accuracy compared to centralised recommender systems. The complete data access of centralised architectures enables models to learn from richer and more homogeneous datasets which results in more accurate recommendations according to Symeonidis et al.[

22]. The privacy-focused design of federated learning maintains user data on local devices but this approach limits model access to complete dataset information which results in reduced predictive accuracy. The inability to access complete user interaction history affects recommendation quality for specific educational content.

The performance difference becomes more pronounced because federated data distribution between clients creates non-independent and identically distributed data which results in slower model convergence and reduced accuracy[

5]. The experimental results which show high MSE values and negative R-squared values match theoretical predictions about federated learning performance so we verify that federated systems experience actual performance limitations when compared to centralised systems

5.4. Privacy Preservation in Practice

The research demonstrates that educational recommender systems can protect user privacy through federated learning methods. The system protects user privacy because data stays on client devices while only aggregated model updates are shared. The training process of our system maintained privacy protection according to Saha et al.[

21] who demonstrated that federated learning can distribute functional models while keeping user information private.

The research community has dedicated extensive effort to this problem but developers still face difficulties in achieving satisfactory results with privacy protection enabled. The system maintained user confidentiality through its operation but this achievement required a trade-off in reduced prediction accuracy. Future research should explore two potential solutions to enhance learning efficiency through advanced aggregation methods and differential privacy mechanisms which would provide stronger privacy protection with minimal performance impact[

9].

5.5. Scalability Considerations

Another practical challenge in the federated recommender system is scalability. With increasing user and item counts, each client processes increasingly smaller partitions of data, which may slow convergence and reduce learning efficiency. These limitations are typically found in scalability; sparse user-item interaction matrices are shown in our study.

With growing online educational technology platforms, scalability issues become sharper. According to Thapaliya et al.[

23], improved aggregation techniques such as advanced federated averaging algorithms may improve scalability without significantly sacrificing the preservation of privacy. Such approaches need to be investigated in educational contexts, where user bases can grow rapidly and unpredictably.

5.6. Broader Software Engineering Implications

While demonstrated in educational contexts, this research contributes fundamental insights to software engineering practice across privacy-sensitive domains. The federated learning architecture represents a generalizable design pattern applicable to healthcare systems requiring HIPAA compliance, financial services implementing distributed fraud detection, IoT ecosystems processing sensor data at edge devices, and enterprise SaaS platforms maintaining multi-tenant data isolation.

The documented performance trade-offs (MSE of 94.78 and negative R-squared values) provide critical benchmarks for software engineers evaluating distributed versus centralized architectures. These metrics quantify the inherent tension between data privacy and system performance, mirroring challenges in distributed databases, microservices, and edge computing where distribution introduces latency and complexity. The findings establish empirical baselines for assessing whether federated approaches suit specific use cases beyond education. The research addresses core software engineering challenges, including privacy-by-design architecture, where privacy is embedded at the system level rather than added retrospectively. The hybrid architecture approach provides flexible frameworks for balancing competing requirements, particularly when designing systems that must coexist with regulatory compliance, user trust, and performance. The data sparsity challenges identified translate directly to any distributed personalisation system, ranging from e-commerce recommendations to personalised healthcare interventions.

From a software engineering perspective, this work highlights the need for reusable federated learning middleware that abstracts implementation complexity, standardized protocols for model aggregation and secure communication, and robust testing methodologies for distributed machine learning systems. The implementation experiences inform DevOps practices for managing heterogeneous client environments, version control across distributed nodes, and monitoring strategies for federated deployments.

Ultimately, this research establishes federated learning as a proven architectural pattern with quantified costs and benefits, empowering software engineers to make informed design decisions when building privacy-preserving systems across domains. The findings contribute to emerging privacy engineering practices where data protection is a foundational architectural principle rather than merely a regulatory requirement.

5.7. Future Directions

Hybrid architectures that combine centralised and federated elements offer a promising direction, enabling organisations to access aggregated data when privacy standards are relaxed or when model performance benefits from limited centralisation.

The implementation of differential privacy presents another future path, providing mathematical privacy assurances while aiming to minimise performance degradation. The collaborative filtering method also requires further improvement through content-based filtering or advanced matrix factorization techniques to address user-item interaction matrix sparsity and achieve better recommendation results in federated systems.

Continued research should focus on developing improved algorithms that can preserve recommendation quality at appropriate levels while maintaining strong privacy protections in distributed learning environments.

6. Conclusions

The research investigates how Federated Learning (FL) works for privacy-protecting education applications through recommender systems. The system operates as a decentralised data processing system to protect user information better while generating enhanced educational course suggestions. The system operates best for privacy-sensitive applications because it maintains data confidentiality through distributed processing. The model implementation achieved complete user privacy protection because researchers understood the essential role of data privacy in educational work with student information under GDPR regulations.

The project encountered multiple problems which emerged during the implementation of federated learning. The proposed model achieved subpar results compared to centralised models based on its MSE and R-squared performance metrics. The model produced suboptimal recommendations because its MSE reached 94.78 and R-squared reached -0.688. The research findings from another study about federated learning support this result because privacy enhancements lead to decreased Generalisation accuracy of machine learning models. The model becomes weaker because the learning process decentralization and local data-based model update proposal reduce the available training information.

The model failed to detect numerous unique user preferences because its precision and recall and F1 scores remained low while recall reached 0.015% and F1 reached 0.0296%. The system faces two major challenges because users interact with items at low rates and the federated structure limits data availability which results in insufficient training data from local devices. The problems encountered in this study match those found in other research about federated learning-based recommendation systems.

The project demonstrates that federated learning works for building privacy-focused recommender systems in sensitive online education environments based on its performance results. The implementation of federated learning for recommender systems requires additional development work to achieve optimal results. The development of model aggregation protocols and collaborative filtering algorithms and methods that unite both approaches represents potential ways to enhance the system. The research confirms privacy advantages of federated learning in educational recommender systems yet introduces potential future improvements for model precision and scalability to achieve better results in practical applications.

References

- Anastasakis, Z.; Bourou, S.; Velivasaki, T. H.; Voulkidis, A.; Skias, D. Analysis of privacy preservation enhancements in federated learning frameworks. River Publishers eBooks. Available online. 2023, pp. pp 117–133. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Asad, M.; others. A comprehensive survey on privacy-preserving techniques in federated recommendation systems. Appl. Sci. Available online. 2023, 13, 6201. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, F. L.; others. A systematic literature review on educational recommender systems for teaching and learning: Research trends, limitations and opportunities. Educ. Inf. Technol. Available online. 2022, 28, 3289–3328. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschênes, M. Recommender systems to support learners’ agency in a learning context: A systematic review. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. Available online. 2020, 17, 1. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efthymiadis, F.; Karras, A.; Karras, C.; Sioutas, S. Advanced optimization techniques for federated learning on non-IID data. Future Internet Available online. 2024, 16, 370. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fachola, C.; others. Federated learning for data analytics in education. Data Available online. 2023, 8, 43. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacks, C. Federated learning: A paradigm shift in data privacy and model training. Medium. 2 March 2024. Available online: https://medium.com/@cloudhacks_/federated-learning-a-paradigm-shift-in-data-privacy-and-model-training-a41519c5fd7e (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Harasic, M.; Keese, F.; Mattern, D.; Paschke, A. Recent advances and future challenges in federated recommender systems. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. Available online. 2023, 17, 337–357. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; others. An overview of implementing security and privacy in federated learning. Artif. Intell. Rev. Available online. 2024, 57, 8. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; others. Federated learning: A distributed shared machine learning method. Complexity. Available online. 2021, pp. 1–20. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Jalalirad, A.; Scavuzzo, M.; Capota, C.; Sprague, M. A simple and efficient federated recommender system. ResearchGate. Available online. 2019. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Javeed, D.; others. Federated learning-based personalised recommendation systems: An overview on security and privacy challenges. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. Available online. 2023, 1. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairouz, P.; others. Advances and open problems in federated learning. Available online. 2021. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Khan, Y.; Sánchez, D.; Domingo-Ferrer, J. Federated learning-based natural language processing: A systematic literature review. Artif. Intell. Rev. Available online. 2024, 57, 12. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ge, L.; Tian, L. Survey: Federated learning data security and privacy-preserving in edge-Internet of Things. Artif. Intell. Rev. Available online. 2024, 57, 5. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhan, D.; Li, X. Aligning model outputs for class imbalanced non-IID federated learning. Mach. Learn. Available online. 2022, 113, 1861–1884. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, K. N.; Mishra, A.; Barwal, P. N.; Lal, R. K. Natural language processing and machine learning-based solution of cold start problem using collaborative filtering approach. Electronics Available online. 2024, 13, 4331. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, C.; Kollias, K.; Fragulis, G. F. Recent advancements in federated learning: State of the art, fundamentals, principles, IoT applications and future trends. Future Internet Available online. 2024, 16, 415. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarsini, N. I.; Raja, G. Federated learning implementation with privacy leakage prevention for hand-written digit recognition. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. Syst. Available online. 2024, 15, 415–425. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, J. T. Federated learning: Machine learning that respects data privacy. Medium. 13 December 2021. Available online: https://medium.com/swlh/federated-learning-machine-learning-that-respects-data-privacy-77fbedd9ec71 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Saha, S.; Hota, A.; Chattopadhyay, A. K.; Nag, A.; Nandi, S. A multifaceted survey on privacy preservation of federated learning: Progress, challenges, and opportunities. Artif. Intell. Rev. Available online. 2024, 57, 7. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symeonidis, P.; Nanopoulos, A.; Papadopoulos, A. N.; Manolopoulos, Y. Nearest-biclusters collaborative filtering based on constant and coherent values. Inf. Retr. Available online. 2007, 11, 51–75. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapaliya, B.; others. Efficient federated learning for distributed neuroimaging data. Front. Neuroinform. Available online. 2024, 18. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Q.; Ding, Y.; Tang, S.; Wang, Y. Privacy-preserving federated learning based on partial low-quality data. J. Cloud Comput. Adv. Syst. Appl. Available online. 2024, 13, 1. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yağcı, M. Educational data mining: Prediction of students’ academic performance using machine learning algorithms. Smart Learn. Environ. Available online. 2022, 9, 1. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusubov, F.; Lee, K. A platform of federated learning management for enhanced mobile collaboration. Electronics Available online. 2024, 13, 4104. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; others. Enhancing dropout prediction in distributed educational data using learning pattern awareness: A federated learning approach. Mathematics Available online. 2023, 11, 4977. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; others. Federated learning-outcome prediction with multi-layer privacy protection. Front. Comput. Sci. Available online. 2023, 18, 6. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; others. Edge intelligence: Paving the last mile of artificial intelligence with edge computing. Proc. IEEE Available online. 2019, 107, 1738–1762. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Zhang, H.; Jin, Y. From federated learning to federated neural architecture search: A survey. Complex. Intell. Syst. Available online. 2021, 7, 639–657. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, K.M.J.; Ahmed, F.; Akhter, N.; Hasan, M.; Amin, R.; Aziz, K.E.; Islam, A.K.M.M.; Mukta, M.S.H.; Islam, A.K.M.N. Challenges, applications and design aspects of federated learning: A survey. IEEE Access Available online. 2021, 9, 124682–124700. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urdaneta-Ponte, M.C.; Mendez-Zorrilla, A.; Oleagordia-Ruiz, I. Recommendation systems for education: Systematic review. Electronics Available online. 2021, 10, 1611. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; Aguera y Arcas, B. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralised data. Proc. 20th Int. Conf. Artif. Intell. Stat. (AISTATS) Available online. 2017, 54, 1273–1282. (accessed on 12 November 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).