1. Introduction

With the widespread adoption of cloud computing, the migration of massive amounts of data to the cloud has become a mainstream trend. While this improves storage efficiency and flexibility, it also introduces significant challenges to data integrity and security. In multi-tenant shared environments, data tampering, forgery, and loss occur frequently, and traditional integrity verification methods based on plaintext inspection struggle to meet the dual requirements of privacy protection and remote verification. Establishing an efficient and trustworthy integrity verification mechanism for encrypted data has therefore become a core issue in cloud storage security. Leveraging the computability advantages of homomorphic encryption, it is possible to perform verification without decryption, expanding the usability of encrypted data and providing a theoretical and technical foundation for a tamper-resistant and auditable cloud data security system.

2. Design of Data Integrity Verification Model Based on Homomorphic Encryption

2.1. System Modeling

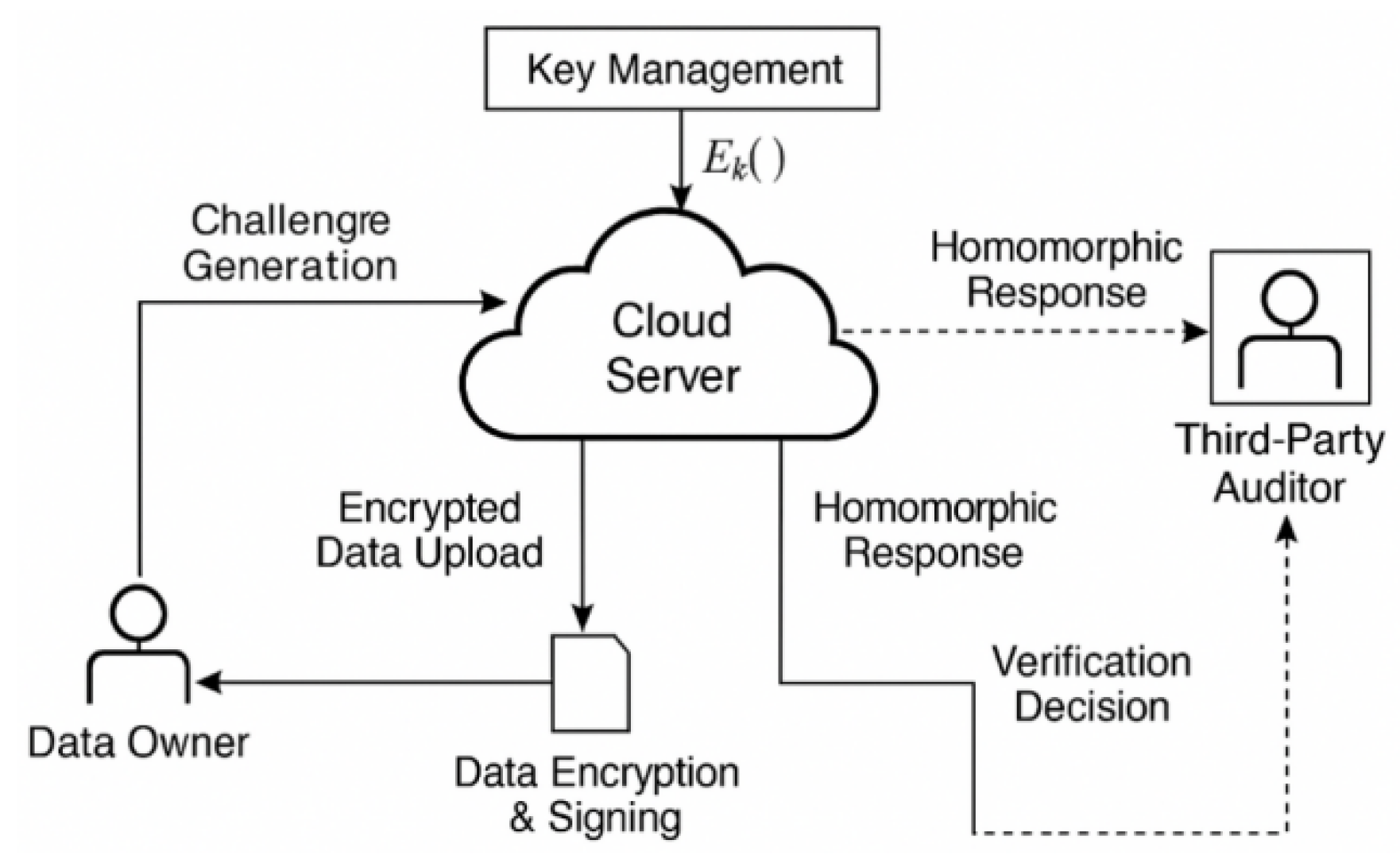

To construct a data integrity verification system based on homomorphic encryption in a cloud storage environment, the system architecture must first be designed hierarchically from the perspective of security and verifiability. The system model mainly involves three parties: the data owner, the cloud storage server, and a third-party authenticator (TPA), with the core objective of enabling efficient remote integrity verification while preserving data privacy through homomorphic encryption [

1]. In the proposed trust model, the cloud storage server is assumed to be semi-honest: it executes protocols correctly but may attempt to infer sensitive information or delete/modify stored data. The Third-Party Authenticator (TPA), acting as a Trusted Third Party (TTP), is assumed to be fully trusted and is responsible for initiating challenge–response verification procedures, validating consistency proofs, and ensuring data integrity without accessing plaintext content. The data owner retains full trust status and is responsible for encryption, key management, and local tag generation. In real-world multi-user scenarios, users interact with the cloud server asynchronously, and the TTP verifies integrity on behalf of multiple data owners without compromising individual keys or metadata. The system uses unique labels and time-bound challenge vectors to isolate operations and prevent replay attacks across tenants. Access control policies and audit mechanisms ensure that actions are securely logged and traceable across multiple users while preserving data locality and privacy. The system’s communication interaction flow and entity functional relationships are shown in

Figure 1, illustrating the role division and data flow paths of each component during data writing, encrypted uploading, challenge response, and result verification. The model also introduces a metadata index structure supporting dynamic data operations to ensure correct and efficient validation when data blocks are inserted, deleted, or modified [

2]. Additionally, the system initialization phase incorporates a key negotiation mechanism and encryption parameter release process, providing a secure foundation for the subsequent design of verification protocols.

2.2. Authentication Protocol Design

Based on the architecture described previously, the authentication protocol is further specified using the Paillier additive homomorphic encryption scheme, a probabilistic asymmetric algorithm that allows algebraic operations directly on ciphertexts. The Paillier scheme satisfies the following homomorphic property:

where

denotes encryption under public key k, and N is a large composite modulus derived from two large primes. Each data block

is independently encrypted as

,where

is a random value chosen per encryption to ensure semantic security.

In the verification initialization phase, the third-party authenticator (TPA) selects a random challenge vector

and transmits it to the cloud server. The server computes the homomorphic response without decryption as:

exploiting the additive homomorphic property of the Paillier encryption. The response R is then returned to the TPA.

For consistency verification, the TPA computes the linear combination ∑vi⋅mi in the plaintext domain using the locally held hash tags σi bound to each data block. It decrypts the homomorphic response RRR and compares the result with the locally computed linear checksum. Any inconsistency indicates potential data modification or corruption. To ensure non-replayability and resistance to chosen-plaintext attacks, each challenge vector v is derived using a combination of a timestamp ttt and a pseudo-random function seeded with a session nonce. Additionally, a lightweight label verification mechanism is embedded to avoid full data download.

Table 1 summarizes the computational complexity of each protocol phase, maintaining scalability at O(n) in most cases.

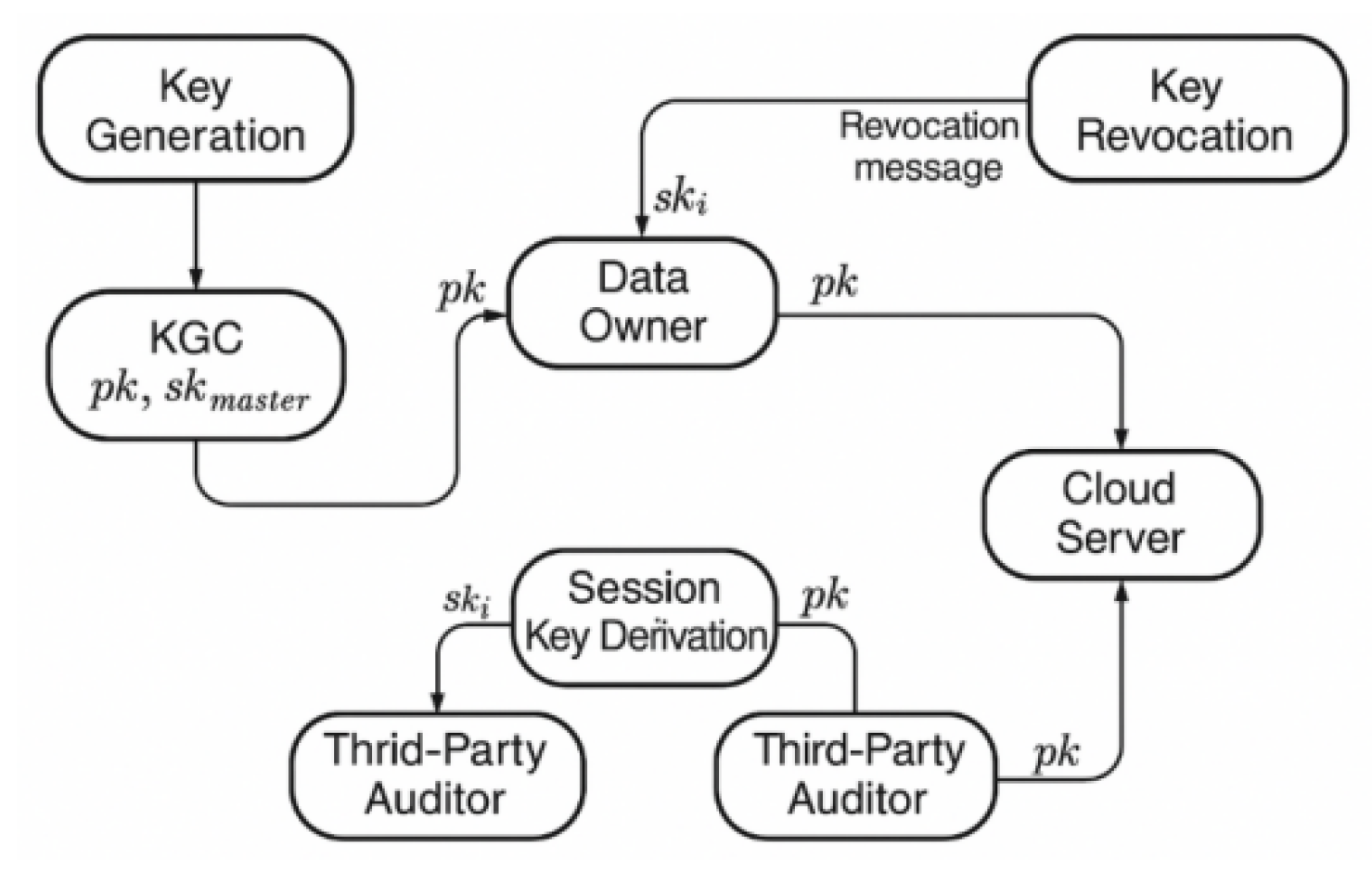

2.3. Key Management Program

To ensure that the homomorphic encryption-based authentication protocol maintains sustainable security during multi-round interactions and dynamic data operations, the system must implement a key management scheme supporting fine-grained privilege separation, revocability, and key updates. In this model, the Key Generation Center (KGC) is responsible for initializing the system security parameters, using RSA or elliptic curve parameters to generate the public key pk and the master private key sk, where pk is widely distributed for data encryption and tag validation, and sk is restricted for use only by the owner or a trusted key escrow module. The key is periodically updated using a time window strategy: let each round of verification period be Δt, then the key pair is valid at time ti, and after expiration, the system derives a new session key,

, ensure forward security and resistance to key leakage [

4].

Figure 2 shows the generation, distribution, update and revocation processes in a key lifecycle. To support privilege isolation between the user side and the authentication side, an attribute-based key distribution mechanism (ABE-KM) is introduced in the system design and bound to the data labels to construct a flexible and controllable access structure. The relationship between key-role mapping and function division is shown in

Table 2.

2.4. Mechanisms for Dynamic Updating of Data

In order to realize verifiable dynamic update of encrypted data during storage in the cloud, this system design introduces a label indexing mechanism that supports homomorphic structure maintenance and a nested system of verifiable data structures (VDS) to ensure that the data block still maintains the verification continuity and label consistency after insertion, deletion, and modification operations. In each update operation, the data owner first re-encrypts the to-be-altered plaintext data block mi’

and generates a new verified label

, where IDi denotes the data block identity and t is the operation timestamp. All encrypted blocks and their corresponding labels are logically organized as an extended authentication index based on a Merkle Hash Tree (MHT). Each update operation triggers a local reconstruction and a synchronized update of the root hash value, serving as the authentication basis [

5]. The update process includes three basic operations: Append (end-of-block append), Modify (in-block replacement), and Delete (logical removal), with their security-checking overheads and complexity summarized in

Table 3. The system mitigates the risk of replay attacks on the same data block at different times through a version-number binding mechanism and encapsulates each update request into a structured request packet. This packet is used by the cloud service to perform data remapping and label replacement, ensuring protocol-level consistency and tamper resistance.

3. Tamper-Resistant Mechanism Implementation

3.1. Data Tampering Detection Methods

To address the risk of unauthorized modification, deletion, or forgery of data in a homomorphic encryption environment, the system implements a data tampering detection method based on a dual mechanism of tag verification and index integrity. The method is based on the verifiable data index constructed by Merkle Hash Tree (MHT), and utilizes the difference between the encrypted tag

generated by the data owner, and the response value returned from the cloud to construct the tamper detection path [

6]. In each round of verification, the system generates a homomorphic aggregated response

based on the challenge vector v and the set of encrypted data {ci}, and at the same time requests the cloud to provide the corresponding path hash proof Π={hpath} in order to verify that the index structure has not been tampered with. If any data block or intermediate hash node is maliciously replaced, it will cause the root hash value

h′root to be inconsistent with the locally computed value, i.e., triggering a tamper warning. In order to further improve the detection granularity and localization capability, the block number and timestamp binding mechanism is introduced. See the data field format definitions listed in

Table 4.

3.2. Data Recovery Mechanisms

In a homomorphic encryption-based data integrity assurance system, merely marking tampering behavior is insufficient to meet security fault-tolerance requirements. Therefore, the system implements a verifiable recovery mechanism based on error correction techniques and label versioning, designed to ensure data availability in adversarial environments. Specifically, Reed–Solomon (RS) codes are employed to segment each original data block mi into k redundant fragments {f1,f2,...,fk}, each bound to a unique encryption tag and timestamp before cloud storage. The recovery level—defined as the number of tolerable corrupted fragments—can be adjusted by modifying the n:kn:kn:k encoding ratio. However, higher recovery capabilities (e.g., 4:2 instead of 3:2 RS code) inevitably increase both the storage footprint and computational complexity for reconstruction [

7]. For instance, each additional redundant fragment raises storage overhead by k/1, while decoding latency grows nearly linearly with the number of fragments involved in the inverse matrix reconstruction process. To balance this trade-off, the system adopts a dynamic encoding strategy—configuring the redundancy ratio based on risk level and access frequency. Frequently accessed or mission-critical data blocks are assigned higher redundancy, whereas cold data segments use minimal coding to reduce cost. During recovery, only the minimal qualified subset of fragments is homomorphically reassembled using R(Ck)=Ek(mi), minimizing unnecessary recomputation.

3.3. Access Control and Audit Trail

After completing the detection and recovery of data tampering, to achieve system-level integrity assurance, it is necessary to construct an access control and audit-tracking mechanism with fine-grained authority control and accountability.In addition to access control based on attribute encryption, each data access operation is recorded on a block-based audit trail (Audit Chain), which logs user identity, data reference, timestamp, and action details [

8]. The audit chain is implemented on a permissioned blockchain (e.g., Hyperledger Fabric), which provides a balance between performance, scalability, and trust assurance. Compared to public blockchains, the permissioned model reduces consensus latency by restricting node participation to authorized entities, enabling faster log confirmation (<200 ms) and low communication cost in a multi-tenant cloud setting [

9]. Moreover, by maintaining a private membership structure, data owners retain control over who participates in the consensus, aligning with the cloud’s semi-trusted architecture. From a trust perspective, the use of a permissioned ledger ensures tamper-evidence while preserving data locality and GDPR compliance. It also facilitates external regulatory audit by exposing selective hash paths to designated verifiers without revealing plaintext or access metadata. To enhance auditing granularity and log classification, the system defines a mapping between access event types and hash audit fields, as shown in

Table 5. Events such as authorized reads (AUTH_READ), unauthorized access attempts (UNAUTH_ACCESS), or tampering alerts (TAMPER_ALERT) are indexed with unique identifiers and cryptographic digests. This structure supports fast log indexing, enables trigger-based policy reconfiguration, and allows for high-efficiency traceability under regulatory review.

4. Program Performance Evaluation and Analysis

4.1. Experimental Environment Construction

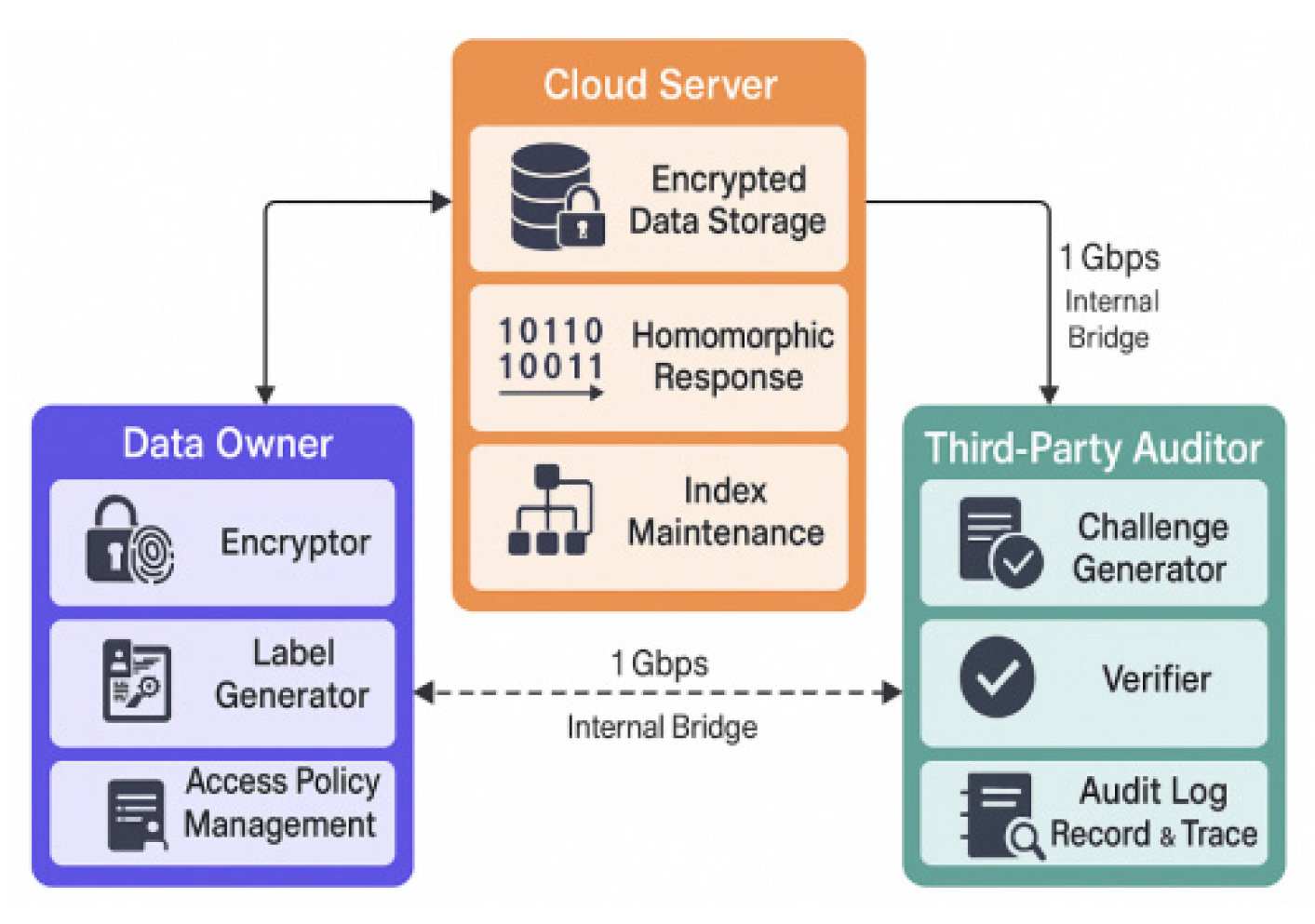

To comprehensively evaluate the operational efficiency and system scalability of the proposed homomorphic encryption-based data integrity verification and anti-tampering mechanism, an experimental test platform is constructed in a simulated cloud computing environment, and the main functional modules are deployed and initialized. The experimental environment uses a VMware vSphere virtual cluster to build a three-tier deployment architecture, including data owner nodes, cloud storage nodes, and third-party verifier nodes, running on physical hosts with 8-core Intel Xeon E5-2630 processors, 32 GB RAM, and Ubuntu 20.04 LTS, with network communication simulated via an internal bridge at 1 Gbps bandwidth. The system backend employs Python 3.10 with the GMP library to implement the Paillier homomorphic encryption module; Merkle Hash Tree index construction is implemented using a C++ custom memory-mapping structure; and the log chaining and access control modules are deployed through MySQL 8.0 integrated with the Python Flask framework [

10].

Figure 3 illustrates the deployment topology of the system test environment. This experimental architecture provides stable support for subsequent performance evaluation under different data sizes and access intensities and establishes a verifiable environment for indicator collection and comparative analysis.

4.2. Analysis of Experimental Results

Under the constructed experimental environment, the proposed mechanism was comprehensively evaluated and compared against two widely-used state-of-the-art schemes: the Provable Data Possession (PDP) protocol and the Proof of Retrievability (POR) model. The evaluation was conducted across three primary metrics: tag generation latency, verification delay, and update overhead, under both static and dynamic data conditions, as well as varying user concurrency levels. For tag generation, we evaluated 1000 data blocks (block size: 4 KB) with individual label computation. Our mechanism, leveraging lightweight Paillier-based hashes, achieved an average tag generation time of 4.3 ms/block, outperforming POR (6.5 ms/block) and PDP (5.2 ms/block). Under dynamic updates (append and modify operations), our mechanism maintained index adjustment latency under O(log n) due to the embedded Merkle Hash Tree structure, as shown in

Table 6. In contrast, the PDP scheme, which lacks efficient support for dynamic metadata, suffered 23% higher re-indexing latency, while POR’s encoding-based update process introduced notable communication overhead (≈38% more data exchange) for label re-generation under similar workloads.

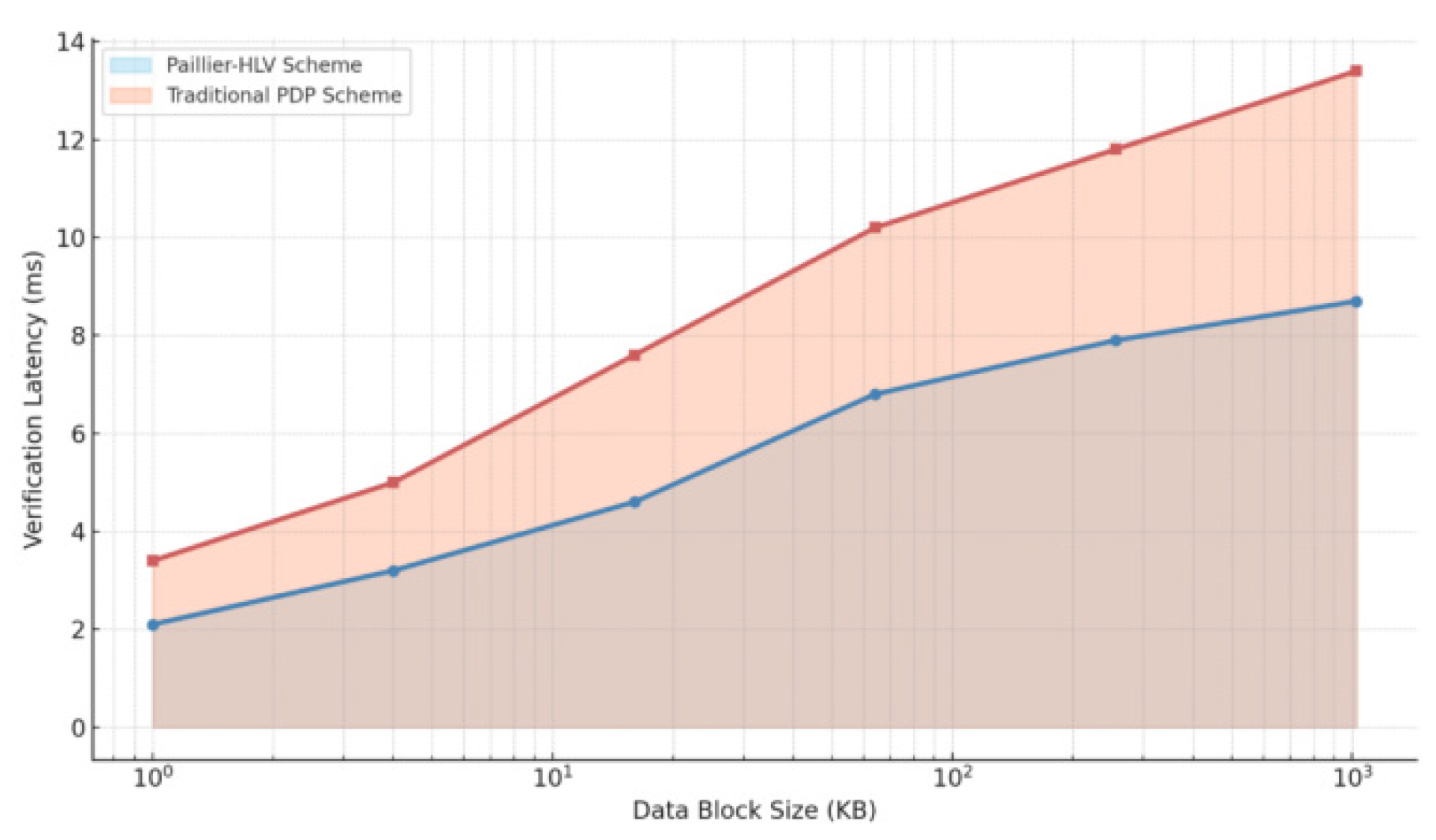

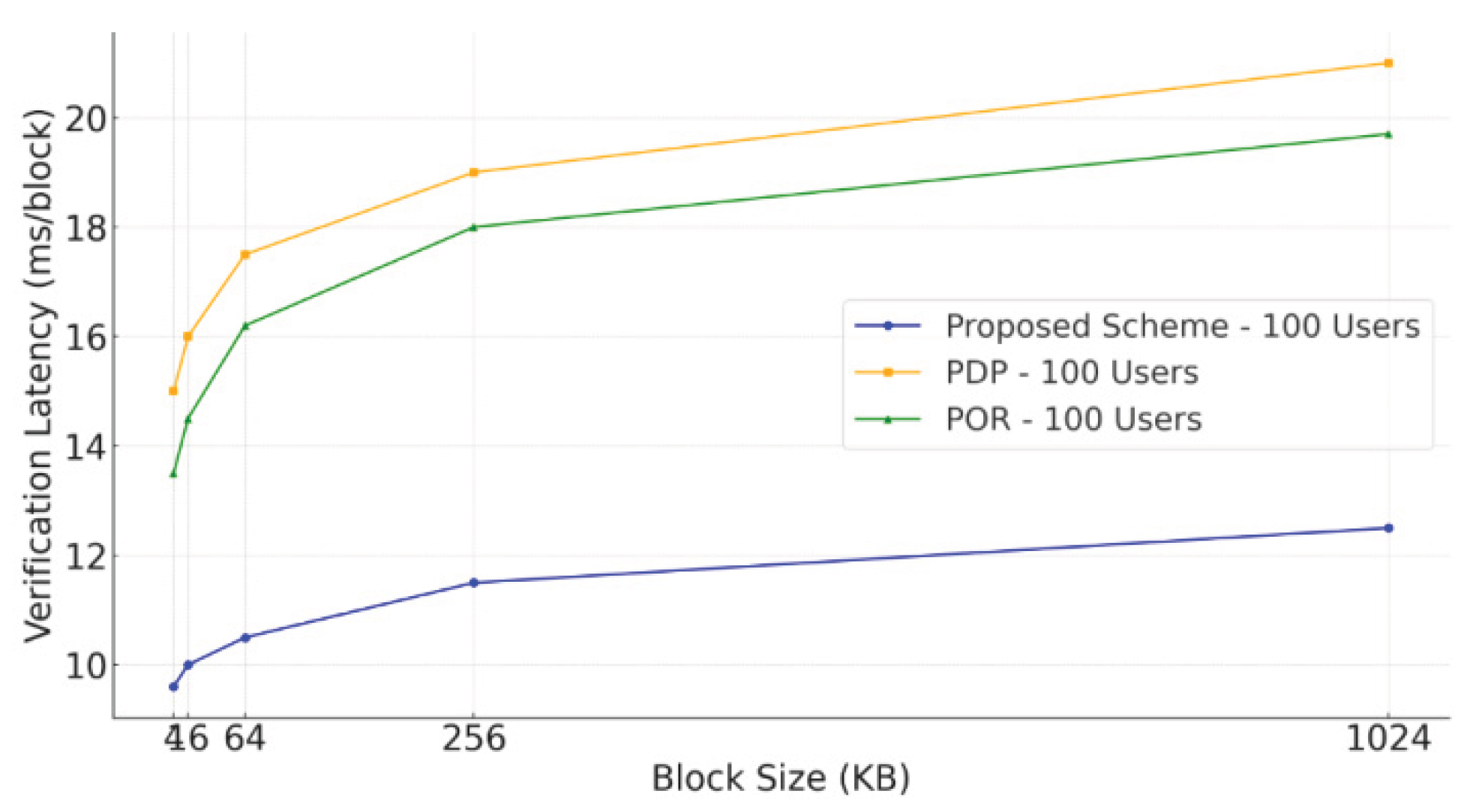

Regarding verification latency,

Figure 4 illustrates a comparison under increasing block sizes. Our mechanism achieved a mean response time of 8.7 ms/block, whereas PDP averaged at 13.4 ms/block, and POR at 11.9 ms/block. The homomorphic response model allows linear ciphertext aggregation without needing block-by-block downloads, thus reducing communication cost by approximately 30% compared to POR.

Figure 5 presents the latency breakdown in relation to block sizes and concurrent request rates (1 to 200 users).

In multi-user scenarios, we simulated concurrent verification requests across 10–200 users. As shown in

Table 7, our approach retained sub-linear scalability with only marginal increases in average latency, demonstrating robustness under high-load conditions. POR exhibited verification delays exceeding 30 ms/block under 200 users due to sequential integrity proof calculations, while PDP suffered from bottlenecks in metadata access and challenge response aggregation.

These results collectively confirm that the proposed mechanism not only preserves cryptographic soundness but also achieves significant practical advantages in performance, especially under real-world constraints involving dynamic data and multi-tenant cloud storage.

5. Conclusions

The proposed integrity verification and tamper-resistant mechanism for cloud storage establishes a security verification system that balances privacy protection and efficiency by incorporating additive homomorphic encryption, lightweight label indexing, and multi-level auditing strategies. The model enables remote verification of dynamic data without exposing plaintext and implements a closed-loop mechanism for data tampering detection, recovery, and access control. Its structural design integrates a Merkle tree with correction and deletion coding, enhancing system scalability and fault tolerance. However, under high-frequency dynamic operations, label index updates and key rotations may introduce additional overhead. Future research can focus on optimizing the computational efficiency of homomorphic responses and exploring the integration of quantum-resistant cryptographic algorithms with blockchain consensus mechanisms to improve adaptability in large-scale distributed environments and ensure long-term security.

References

- Ansari, M D; Gunjan, V K; Rashid, E. On security and data integrity framework for cloud computing using tamper-proofing[C]//ICCCE 2020: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Communications and Cyber Physical Engineering. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, 2020: 1919-1427. 3rd International Conference on Communications and Cyber Physical Engineering. Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2020; 1419–1427. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, P C; Wang, D; Zhao, Y; et al. Blockchain data-based cloud data integrity protection mechanism[J]. Future Generation Computer Systems 2020, 102, 902–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M; Zhang, Y; Zhu, Y; et al. DIVRS: Data integrity verification based on ring signature in cloud storage[J]. Computers & Security 2023, 124, 103002. [Google Scholar]

- Medileh, S; Laouid, A; Hammoudeh, M; et al. A multi-key with partially homomorphic encryption scheme for low-end devices ensuring data integrity[J]. Information 2023, 14, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z; Ahmad, M N; Jin, Y; et al. Unleashing Trustworthy Cloud Storage: Harnessing Blockchain for Cloud Data Integrity Verification[C]//International Visual Informatics Conference; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp. 443–452. [Google Scholar]

- Goswami, P; Faujdar, N; Debnath, S; et al. Investigation on storage level data integrity strategies in cloud computing: classification, security obstructions, challenges and vulnerability[J]. Journal of Cloud Computing 2024, 13, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangadevi, K; Devi, R R. A survey on data integrity verification schemes using blockchain technology in Cloud Computing Environment[C]. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2021, 1110, 012011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavanya, M; Kavitha, V. Secure tamper-resistant electronic health record transaction in cloud system via blockchain[J]. Wireless Personal Communications, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S; Zhang, W; Liang, W; et al. Blockchain-based secure and verifiable storage scheme for IPFS-assisted IoT with homomorphic encryption[J]. Computing 2025, 107, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y; Geng, H; Su, L; et al. A blockchain-based efficient data integrity verification scheme in multi-cloud storage[J]. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 105920–105929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).