1. Introduction

Hydrogen, as an energy vector, offers a sustainable alternative to fossil fuels, addressing global challenges like climate change and rising energy demand [

1]. Its high gravimetric energy density, significantly higher than that of conventional fuels, makes it an attractive option for many practical applications. However, developing efficient storage systems remains critical for the widespread usage of hydrogen [2-4].

Hydrogen is mainly stored in three primary forms: as a compressed gas, cryogenic liquid, or solid-state material. Compressed and liquid hydrogen storage face challenges such as high pressure, cryogenic temperature, and high costs. Solid-state in the form of metal hydrides could potentially provide safe storage with high volumetric density under relatively mild temperature and pressure conditions [

2,

5,

6]. Solid-state storage involves the storage of hydrogen, either on the surface of solids through Van der Waals interactions or within solids, by forming chemical bonds with the metal atoms to form metal hydrides [

7,

8].

Among metal hydrides, TiFe-based alloys are promising materials for hydrogen storage due to their abundance, low cost, and good reversibility during hydrogen absorption and desorption [9-12]. The TiFe alloy is a well-known AB-type intermetallic compound capable of storing approximately 1.86 wt% of hydrogen, first reported by Reilly and Wiswall in 1974 [

13].

A major limitation of TiFe alloys is their first hydrogenation kinetics. During air exposure, a surface oxide layer is naturally formed which acts as a barrier for hydrogen diffusion into the alloy. As a result, when TiFe alloy is exposed to hydrogen, a certain time is needed for penetration of hydrogen into the alloy and reaction with metal atoms. This period is known as the incubation time. Once this barrier is overcome, the hydrogenation can proceed [

14,

15].

To break the oxide layer, and starting the hydrogen absorption reaction, Reilly and Wiswall used the method of heating the alloy to 400℃, followed by cooling and applying a high hydrogen pressure of approximately 60 bars [

13]. This process had to be repeated several times until the alloy could be fully hydrided. This method has since been widely used in numerous studies on TiFe alloys [

16,

17].

Adding transition elements such as Zr [

18,

19], Mn [20-22], Cr [

10,

20], and Y [

23] can significantly improve the first hydrogenation kinetics by promoting the formation of secondary phases that facilitate hydrogen diffusion. Mechanical deformation techniques like ball milling [

24,

25], cold rolling [

26,

27], and high-pressure torsion [

28] are also beneficial for improving first hydrogenation kinetics by creating grain boundaries and cracks, which act as pathways for hydrogen to penetrate the oxide layer. Furthermore, several studies have shown that powder processing methods like gas atomization could enhance the first hydrogenation properties of TiFe-based alloys by producing a finer microstructure [

27,

29,

30]. Ulate-Kolitsky et al. compared alloys synthesized by gas atomization and induction melting, concluding that gas atomization resulted in a much finer microstructure and a TiFe matrix with a more refined distribution of secondary phases [

27].

Previous research has indicated that the hydrogen absorption process generally follows an Arrhenius mechanism, and there have been attempts to calculate the activation energy of metal hydride formation in these alloys [22,31-34]. Bowman and Tadlock [

33] investigated the hydrogen diffusion rate in TiFeH phase using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) techniques, and the temperature dependence of the proton relaxation rate suggested Arrhenius behavior, leading to the calculation of activation energy as 31.8 kJ/mol. Chung and Lee [

34] demonstrated that hydrogen absorption kinetics of TiFe alloys improve with partial substitution of Mn and Ni for Fe. They found that the hydriding rate depends on the difference between the applied pressure and the equilibrium pressure, and from Arrhenius plots of the rate constants versus 1/T, they calculated the activation energies to be 33.5 kJ/mol for TiFe, 32.6 kJ/mol for TiFe₀.₈₅Mn₀.₁₅, and 31.8 kJ/mol for TiFe₀.₉Ni₀.₁.

The above-mentioned studies calculated the activation energy associated with hydrogen absorption after the alloy had already hydrogenated, and the incubation stage caused by the surface oxide layer was no longer present. However, the first hydrogenation where the oxide is broken is critical as it can significantly influence the cost and efficiency of metal hydride formation. In the present study, we systematically investigate the first hydrogenation behavior of a TiFe-based alloy (Ti₄₈.₈Fe₄₆.₀Mn₅.₂) produced by gas atomization. This composition was selected because Mn substitution could promote the formation of secondary phases that facilitate hydrogen diffusion [20-22]. Unlike previous works, which focused only on alloys that were already subjected to a few hydrogenation/dehydrogenation steps, this study focus on the first hydrogenation. The effects of temperature, constant driving force, and hydrogen pressure on the incubation time of the first hydrogenation was investigated. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic investigation of how working conditions influence the first hydrogenation of a TiFe-based alloy.

2. Materials and Methods

The gas-atomized alloy, with an atomic composition of 48.8 Ti, 46.0 Fe, and 5.2 Mn, was provided by GKN Hoeganaes Innovation Centre and Advanced Materials. Gas atomization was carried out by GKN under pure argon using a VIGA-type furnace equipped with a free-fall atomization ring set-up. Following synthesis, the powder was stored in the air.

The atomized powder was subjected to five cold rolling passes before hydrogenation. Cold rolling was performed vertically in the air using a modified Durston DRM 130 rolling mill (High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, UK). The powder was inserted between two 316 stainless steel plates to prevent contamination of the powder by the rollers.

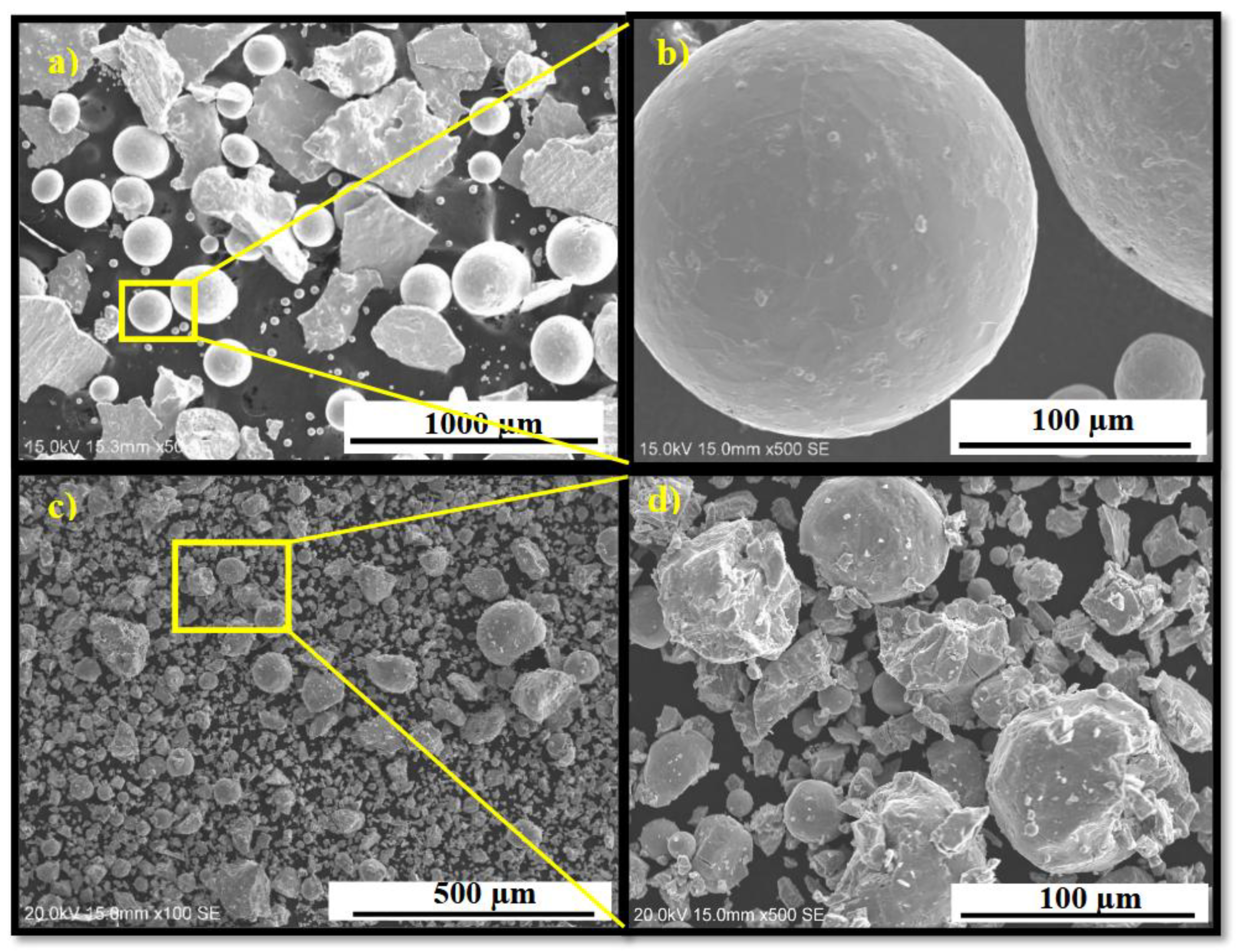

The powder morphology before and after cold rolling was examined using a Hitachi SU1510 scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Hitachi High-Tech Canada, Toronto, ON, Canada).

The hydrogenation tests were carried out using a homemade Sievert’s apparatus. The measurements were conducted under various pressures ranging from 15 bars to 50 bars at temperatures of 298 K, 308 K, 318 K, and 328 K. Each hydrogenation test was conducted on about one gram of fresh sample. The samples were evacuated for 15 minutes at room temperature prior to kinetic measurements. The volume of chamber was 44 cm3. The estimated error on the capacity was ±0.04 wt.%.

3. Results and Discussion

The microstructure, crystal structure, and first hydrogenation of Ti

48.8Fe

46.0Mn

5.2 alloy were reported in our earlier paper [

35]. It was found that the microstructure consisted of a main TiFe matrix and a filamentous Ti

2Fe-like phase. The main TiFe phase exhibited a BCC crystal structure with a lattice parameter of 2.9828 ± 0.0004 Å.

As reported in our previous study, the as-received atomized Ti48.8Fe46.0Mn5.2 alloy was unable to absorb hydrogen under two different test conditions: (i) at room temperature under 20 bars H₂ pressure, and (ii) at 363 K under 45 bars H₂. To activate the alloy, it was subjected to five passes of cold rolling (5CR) in the air. After cold rolling, the obtained flakes and powders were manually crushed in air into powder using a hardened steel mortar and pestle. The resulting powder had a particle size distribution ranging from 45 to 212 μm. This obtained powder was subsequently used for the hydrogenation tests. The 5CR alloy successfully absorbed hydrogen under both above-mentioned testing conditions. Given that cold rolling in air successfully activated the material, and considering industrial collaboration of the research and the practical convenience of cold rolling in air, all further cold rolling steps were conducted in air.

Figure 1 presents the morphology of the as-received and cold-rolled powders. A reduction in particle size is evident after cold rolling, along with the formation of cracks on the powder surfaces. As shown in

Figure 1-a, a combination of spherical and non-spherical particles was observed in the atomized powder. The spherical particles have a size distribution from 20 µm up to 300 µm, while non-spherical particles fall within the 100–400 µm range.

Figure 1-c shows that after five passes of cold rolling, the average particle size decreased significantly. Most particles were reduced to below 20 µm, although some larger particles (~100 µm) remained. In addition to the decrease in particle size, cold rolling introduced numerous cracks and surface defects which are clearly visible under the higher magnification of figure 1-d. These morphological changes, including particle size reduction and the formation of cracks and defects, enhance hydrogen diffusion and facilitate hydrogen absorption. This effect has been observed in other alloys such as TiFe [

27,

36,

37], LaNi

5 [

38], Mg [

39,

40], and high-entropy alloys [

41].

After finding that five passes of cold rolling effectively regenerate the Ti48.8Fe46.0Mn5.2 alloy for hydrogen absorption, the next step was to evaluate the first hydrogenation parameters systematically. Therefore, in the following sections, we investigate the effects of temperature, constant driving force, and hydrogen pressure on the first hydrogenation behavior. For preparing the alloy for hydrogen absorption, all kinetic experiments were conducted on samples subjected to 5 cold rolling passes prior to each test.

3.1. Effect of Temperature on First Hydrogenation of Ti48.8Fe46.0Mn5.2 -5CR

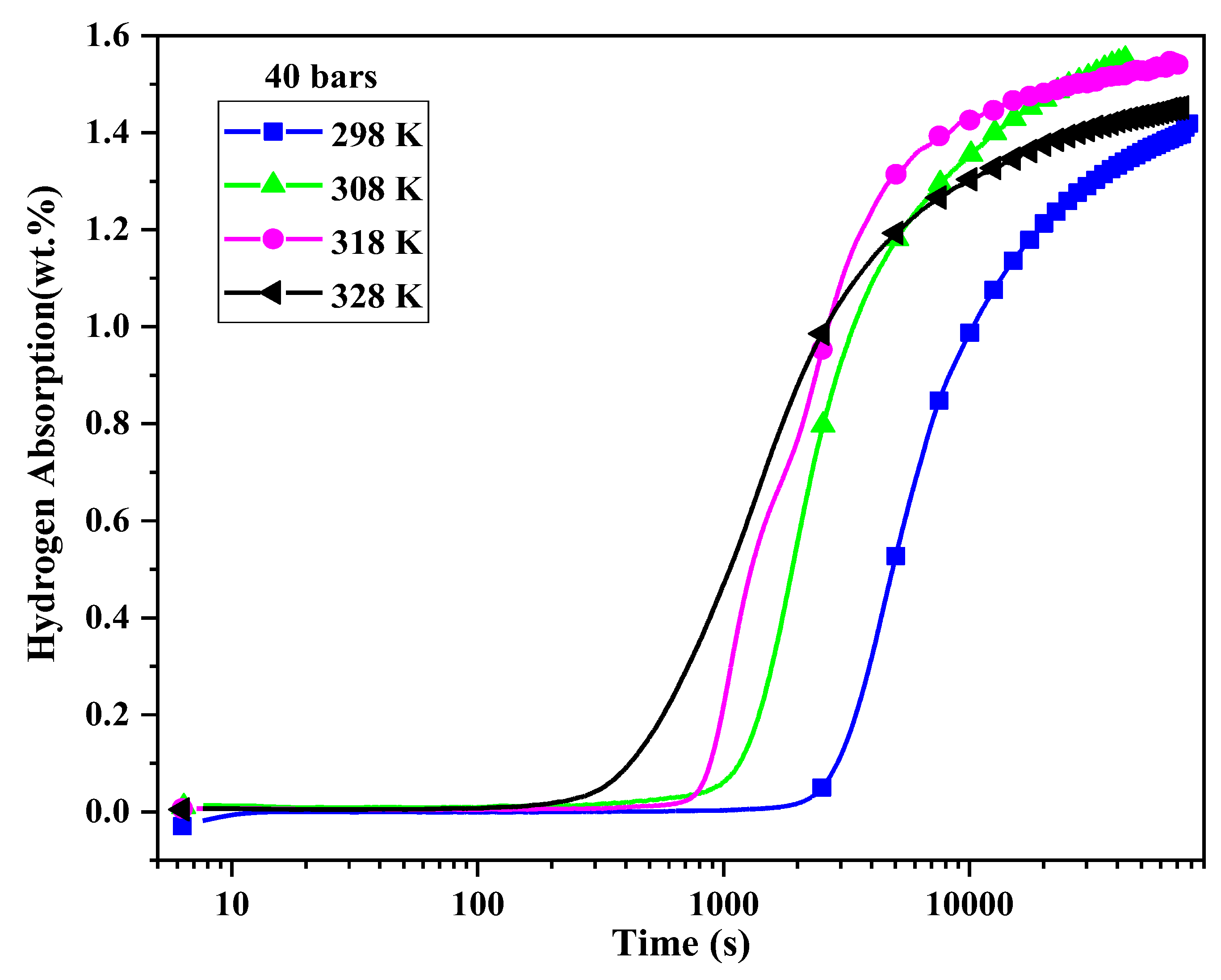

The effect of temperature on the first hydrogenation was investigated by measuring the incubation time at 298 K, 308 K, 318 K, and 328 K under a hydrogen pressure of 40 bars.

Figure 2 shows the first hydrogenation kinetics of the of Ti

48.8Fe

46.0Mn

5.2 -5CR alloy at different temperatures under a hydrogen pressure of 40 bars. We see that the incubation time decreases with increasing temperature from approximately 3000 s at 298 K to 330 s at 328 K.

The fact that incubation time varies with temperature indicates that the process may follow an Arrhenius-type behavior. The Arrhenius equation describes the relationship between the rate of a chemical reaction and temperature, and is expressed as:

Where:

k is the rate constant of the chemical reaction,

A is the pre-exponential factor or Arrhenius factor, a constant related to the frequency of collisions of reacting molecules (s-1),

Ea is the activation energy for the reaction (J/mol),

R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J/(mol K)),

T is the absolute temperature (K).

Since incubation time (t) is inversely proportional to the rate constant:

Then, equation (1) could be written as:

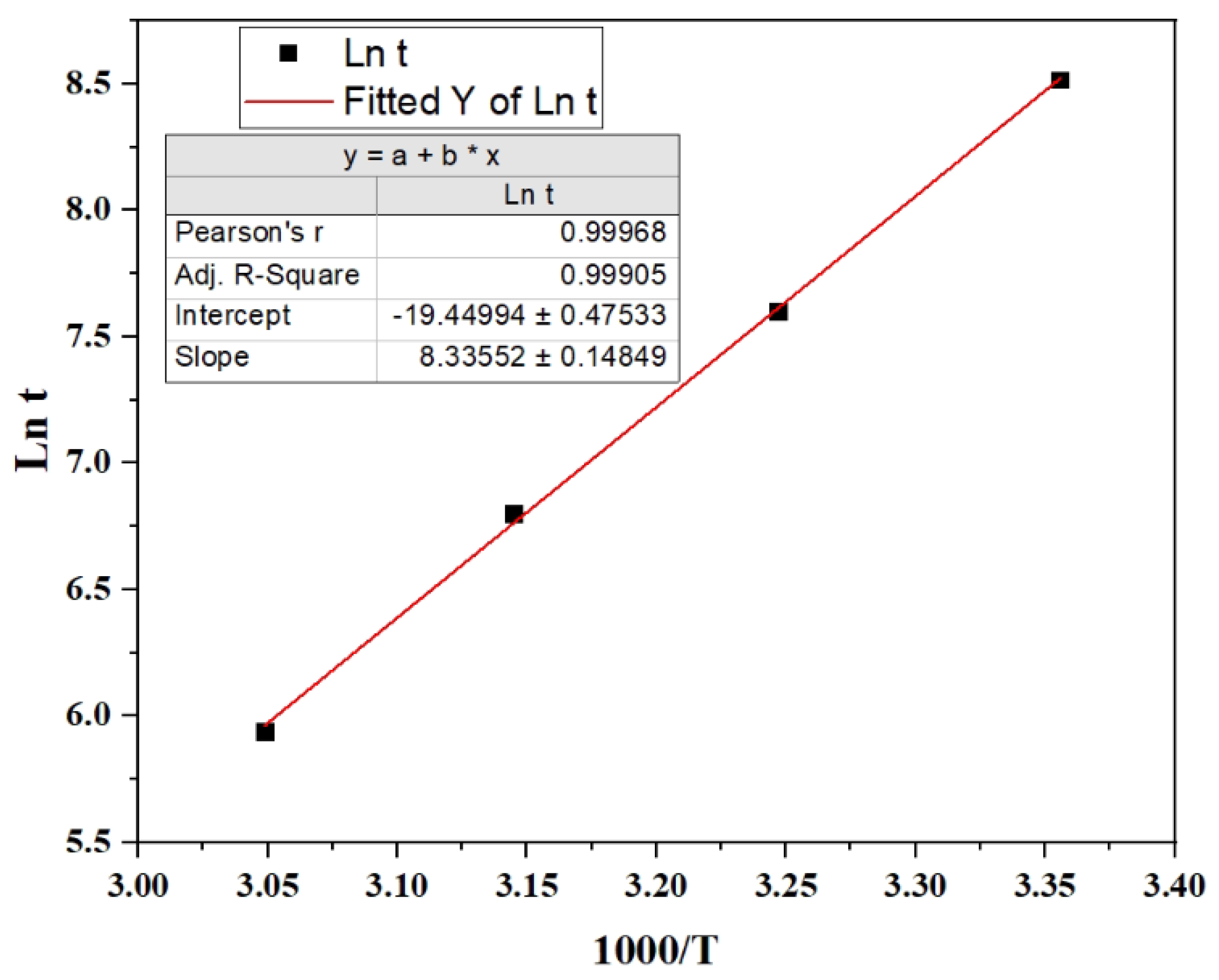

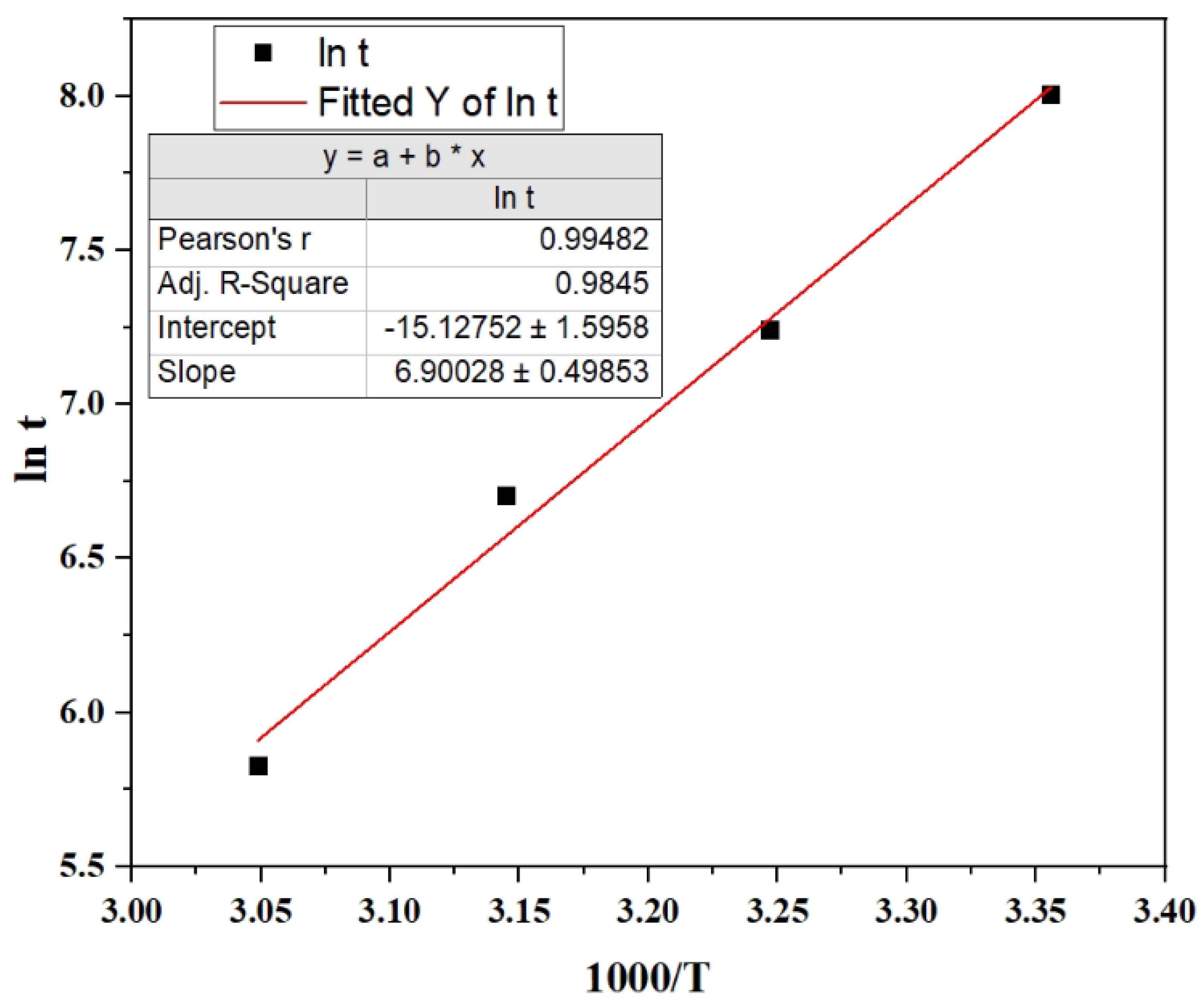

In

Figure 3, ln t is plotted as a function of 1000/T. From the slope of the fitted line, the activation energy is calculated to be E

a = 69 ± 1 kJ/mol H

2. Additionally, from the intercept, A is 2.6 × 10

8 s⁻¹ with a range from 1.6 × 10

8 to 4.2 × 10

8 s

-1.

3.2. First Hydrogenation Behavior Under a Constant Driving Force

In hydrogen absorption reactions, the difference between the applied pressure and the hydrogenation equilibrium pressure is defined as the driving force, which controls the reaction rate. Driving force can be characterized using the Rudman’s expression [

42]:

Where c is the driving force, T is the temperature, P is the applied pressure, and Pe is the equilibrium pressure of the reaction. For the calculation we used the literature thermodynamic values of the closely related composition Ti

1Fe

0.9Mn

0.1 [

43].

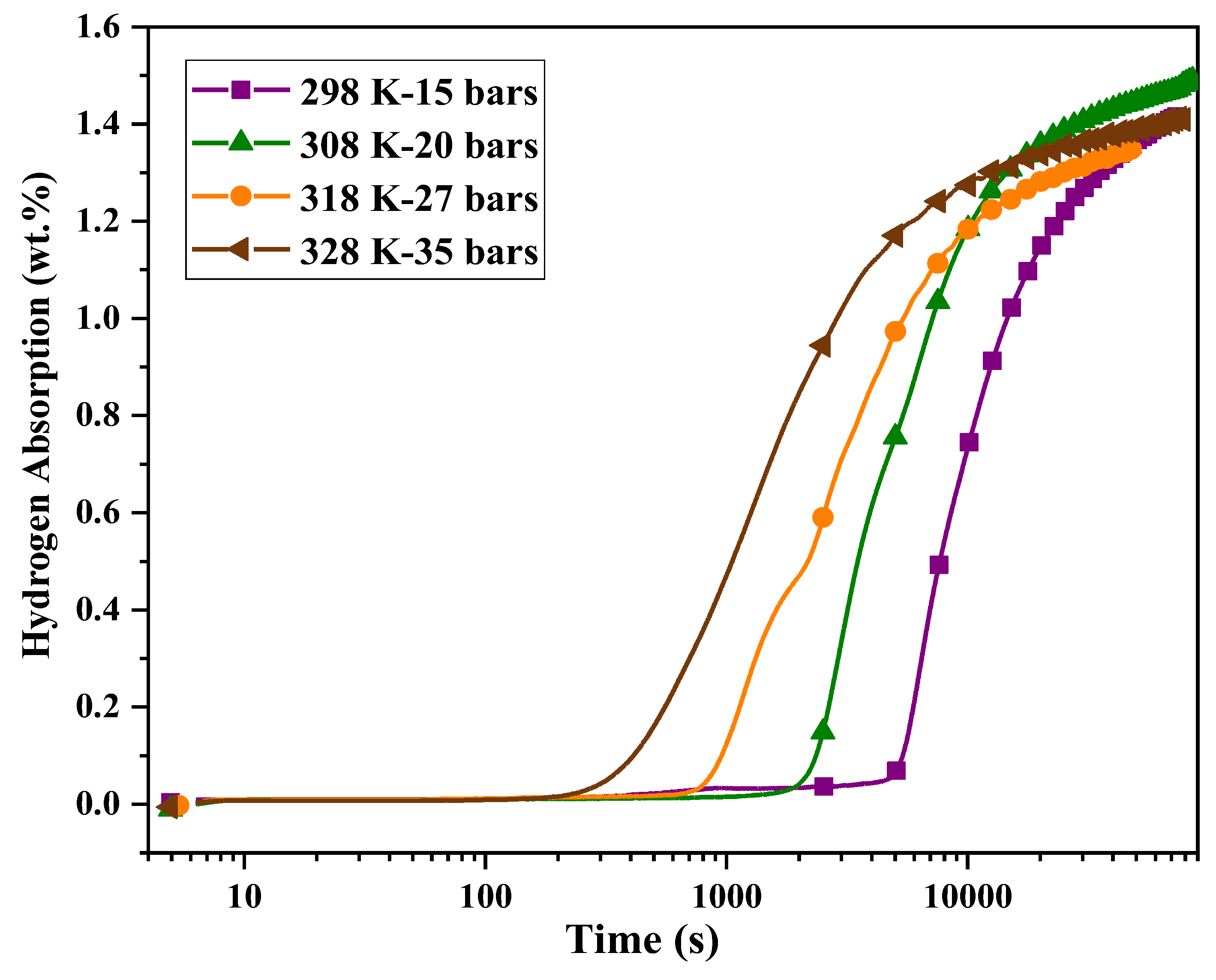

A higher C value indicates a stronger driving force for the hydrogen absorption reaction. In these experiments, the driving force was maintained constant as C=175, and the hydrogen absorption tests were carried out at 298, 308, 318, and 328 K. The corresponding pressures were calculated as 15, 20, 27 and 35 bars, respectively. The results are shown in

Figure 4.

As the applied pressures in these experiments are lower than the 40 bars used in the previous experiment (

Figure 2), the incubation times are correspondingly longer. The incubation time is plotted as a function of 1000/T in

Figure 5 to determine whether the Arrhenius mechanism is still applicable. The linear fit demonstrates that the incubation time still obeys an Arrhenius law. The fitted slope yields an activation energy of E

a = 57 ± 4 kJ/mol H

2. The intercept reveals the pre-exponential factor (A) as 3.6×10

6 s

-1, with a range from 7.3×10

5 to 1.8×10

7 s

-1.

The activation energies obtained under constant pressure and constant driving force conditions are different. In the constant pressure case, as the temperature increases, the equilibrium pressure (Pe) also increases, which reduces the driving force. Therefore, both temperature and driving force vary simultaneously, which may lead to an overestimation of the activation energy. In contrast, When the driving force is kept constant (C = 175), the applied pressure is adjusted at each temperature to compensate for changes in Pe. As a result, the thermodynamic effect is removed, and the changes in incubation time come only from the intrinsic kinetics.

Regarding the pre-exponential factor (A), it represents the number of interactions per second, and obviously, this is pressure dependent. For practical applications, it is important to have the pressure dependence of this factor because it will give the range of pressures required to have a reasonable incubation time. In a previous investigation on LaNi

5 alloy, we have confirmed that the pre-exponential factor is pressure-dependent [

44].

The dependency of A on pressure can be expressed as:

Here, A₀ and x are constants, P represents the applied hydrogen pressure, and P₀=1 bar.

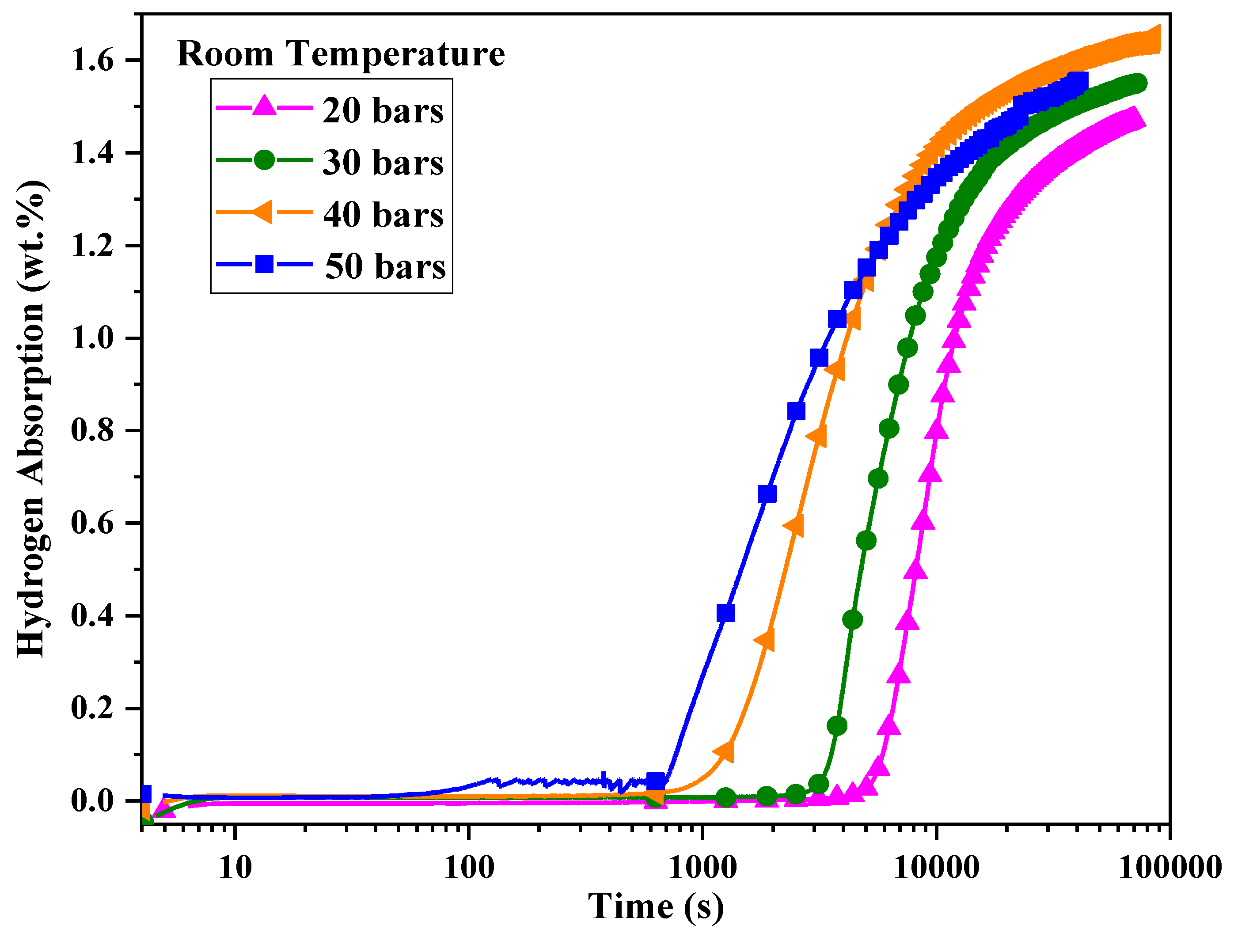

3.3. Effect of Pressure on First Hydrogenation Behavior

To study the effect of pressure on the pre-exponential factor, the first hydrogenation was performed at 298 K under 20, 30, 40, and 50 bars of hydrogen pressure. The hydrogenation curves are shown in

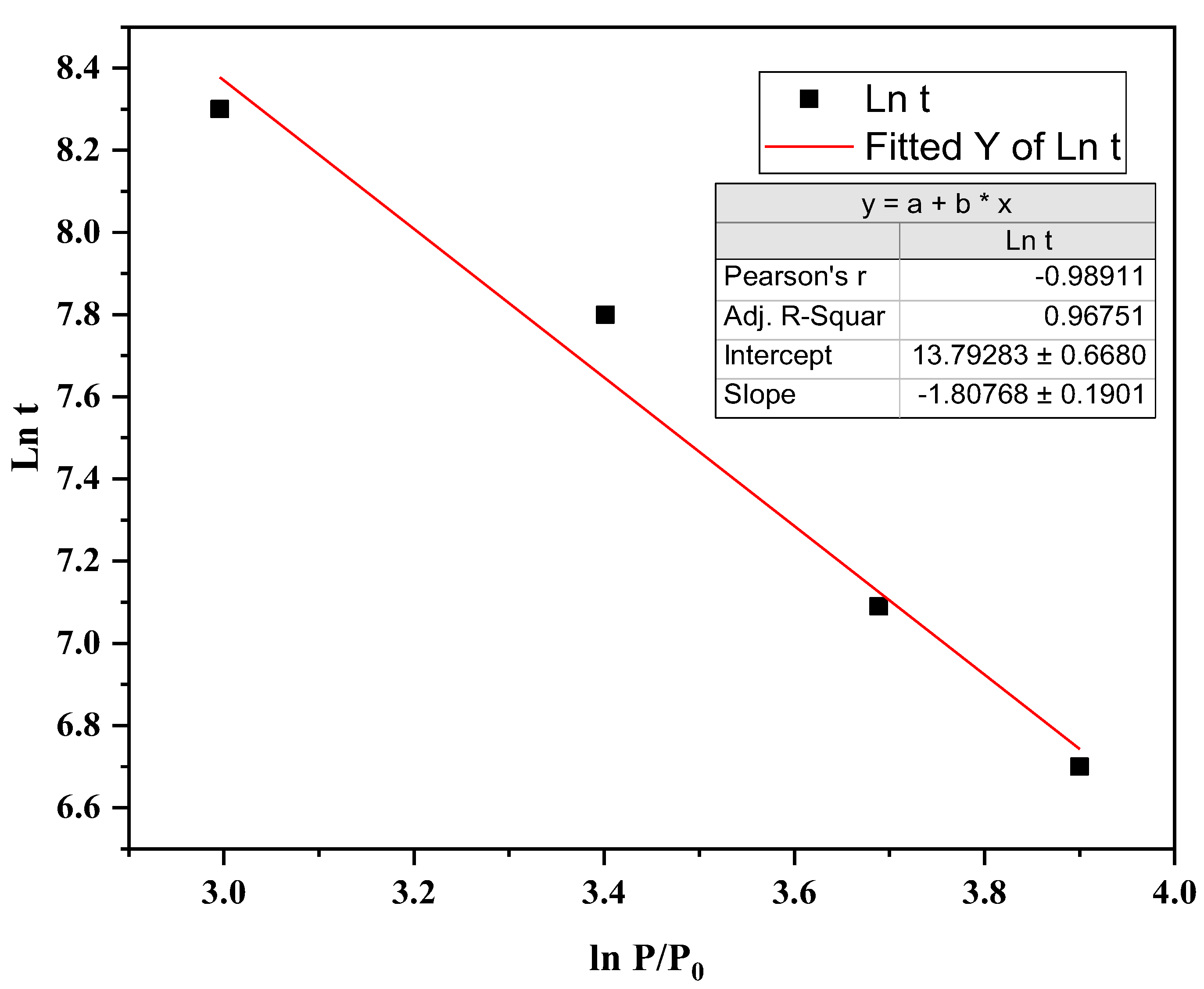

Figure 6. With increasing pressure, the incubation time decreased. The variation of ln t as a function of ln P/P₀ is shown in

Figure 7.

Considering equation 5, equation 3 can be written as:

From the fitted slope of

Figure 7, x = 1.8 ± 0.2, and from the intercept value:

Taking the activation energy as 57 kJ/mol, A₀ is calculated to be 1.0 × 10

4 s⁻¹. Therefore, the pre-exponential factor A can be expressed as:

By comparison, in the previous research on LaNi

5 alloy, the pressure exponent x was found to be 1.6, indicating a similar but slightly weaker pressure dependence [

44].

The activation energy reported in the literature have been on samples that were subjected to many hydrogenation/dehydrogenation cycles. To our knowledge, one of the first measurement was made by Jai-Young et al. [

45] who measured the activation energy of TiFe on a sample cycles 100 times at 294K. They measured activation energy of 3 kJ/mol., a value that is very low compared to the subsequent measurements.

Bowman and Tadlock [

33] prepared TiFeH by performing several hydriding–dehydriding cycles between room temperature and 400 °C. By using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) techniques, they observed that the proton relaxation rate exhibited Arrhenius-type temperature dependence. From the slope of their plot, they determined an activation energy of 31.8 kJ/mol, which is less than the activation energy found in our study. The activation energy reported by Bowman and Tadlock refers to the hydrogenation cycles after the material had been fully activated. Our study specifically focuses on the first hydrogenation process

, which includes both the activation energy for hydrogen absorption and the additional activation energy required for the incubation process.

Furthermore, Bowman and Tadlock’s study [

33] measured the activation energy of TiFe alloys without elemental substitution, whereas in our study, manganese (Mn) was partially substituted for iron (Fe). However, previous studies have shown that Mn substitution facilitates hydrogen absorption kinetics but does not significantly affect the activation energy [

22,

34]. Chung and Lee [

34] prepared TiFe and TiFe

0.85Mn

0.

15 alloys by arc melting and activated them through heat treatment at 400 °C under hydrogen atmosphere, followed by hydrogen absorption–desorption cycles at room temperature. They found that, for both alloys, the hydrogenation rate was proportional to the difference between the applied pressure and the equilibrium pressure, and it also followed an Arrhenius relationship. From their analysis, they measured activation energies of 33.5 kJ/mol for TiFe and 32.6 kJ/mol for TiFe

0.85Mn

0.15.

Similarly, Padhee et al. [

22] employed Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations to estimate the activation energy of TiFe and TiFe₀

.₈₇₅Mn₀

.₁₂₅, reporting values of 32.6 kJ/mol and 33.3 kJ/mol

, respectively. These results also show that Mn substitution causes minimal changes in the activation energy.

The consensus of the recent determination of the activation energy of TiFe and TiFe-based alloys is a value of around 32 kJ/mol. This is much lower than the value we measured. The reason is that they evaluated the activation energy of the hydrogen absorption reaction after the first hydrogenation had occurred. In contrast, our study measured the activation energy for both the incubation stage and hydrogen absorption. It is thus reasonable that the activation energy measured here is bigger than the activation energy reported in the literature, as it includes the activation energy needed to break the oxide layer on the particle’s surface plus the hydrogenation activation energy.

4. Conclusions

In this study, the first hydrogenation behavior of Ti48.8Fe46.0Mn5.2 alloy, synthesized via gas atomization, was investigated. The effects of temperature, constant driving force, and hydrogen pressure on the first hydrogenation were studied. It was observed that increasing the temperature and pressure reduced the incubation time required for hydrogen absorption. Analysis of the kinetic data confirmed that the first hydrogenation follows an Arrhenius-type mechanism, with activation energies determined to be 69 kJ/mol H₂ under constant pressure conditions and 57 kJ/mol H₂ under constant driving force conditions. These results suggest that constant driving force conditions may provide a more accurate estimate of activation energy because of the elimination of the influence of the changing driving force when the experiment is done under constant pressure. The effect of pressure on the pre-exponential factor (A) was found to vary as A=A₀(P/P₀)1.8, where A₀ equals 1.3 × 106 s⁻¹. These findings provide important insights for optimizing the first hydrogenation of TiFe-based alloys for hydrogen storage applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H. and J.H.; validation, S.H. and J.H.; formal analysis, S.H.; investigation, S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.H.; writing—review and editing, S.H., C.S. and J.H.; supervision, J.H.; project administration, J.H and C.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by GKN Hoeganaes Innovation Centre and Advanced Materials and MITACS.

Acknowledgments

Seyedehfaranak Hosseinigourajoubi acknowledges GKN Hoeganaes Innovation Centre and Advanced Materials and MITACS for the fellowship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lu, X.; Krutoff, A.-C.; Wappler, M.; Fischer, A. Key influencing factors on hydrogen storage and transportation costs: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 105, 308-325. [CrossRef]

- Bosu, S.; Rajamohan, N. Recent advancements in hydrogen storage-Comparative review on methods, operating conditions and challenges. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 352-370.

- Dincer, I. Renewable energy and sustainable development: a crucial review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2000, 4, 157-175. [CrossRef]

- Umar, A.A.; Hossain, M.M. Hydrogen storage via adsorption: A review of recent advances and challenges. Fuel 2025, 387, 134273. [CrossRef]

- Von Colbe, J.B.; Ares, J.-R.; Barale, J.; Baricco, M.; Buckley, C.; Capurso, G.; Gallandat, N.; Grant, D.M.; Guzik, M.N.; Jacob, I. Application of hydrides in hydrogen storage and compression: Achievements, outlook and perspectives. international journal of hydrogen energy 2019, 44, 7780-7808.

- Greene, D.L.; Ogden, J.M.; Lin, Z. Challenges in the designing, planning and deployment of hydrogen refueling infrastructure for fuel cell electric vehicles. eTransportation 2020, 6, 100086. [CrossRef]

- Abe, J.O.; Popoola, A.P.I.; Ajenifuja, E.; Popoola, O.M. Hydrogen energy, economy and storage: Review and recommendation. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 15072-15086. [CrossRef]

- Schlapbach, L. Technology: Hydrogen-fuelled vehicles. Nature 2009, 460, 809-811. [CrossRef]

- Rachidi, S.; El Kassaoui, M.; Tahiri, N.; Mounkachi, O.; Ez-Zahraouy, H. Understanding degradation mechanisms and hydrogenation kinetics of intrinsic γ-FeTiH2. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 104, 114571. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Guo, F.; Sunamoto, R.; Yin, C.; Miyaoka, H.; Ichikawa, T. Anti-oxidation effect of chromium addition for TiFe hydrogen storage alloys. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2024, 1008, 176634. [CrossRef]

- Schober, T.; Westlake, D.G. The activation of FeTi for hydrogen storage: A different view. Scripta Metallurgica 1981, 15, 913-918. [CrossRef]

- Lototsky, M.V.; Davids, M.W.; Fokin, V.N.; Fokina, E.E.; Tarasov, B.P. Hydrogen-Accumulating Materials Based on Titanium and Iron Alloys (Review). Thermal Engineering 2024, 71, 264-279. [CrossRef]

- Reilly, J.J.; Wiswall, R.H. Formation and properties of iron titanium hydride. Inorganic Chemistry 1974, 13, 218-222. [CrossRef]

- Sartori, S.; Amati, M.; Gregoratti, L.; Jensen, E.H.; Kudriashova, N.; Huot, J. Study of Phase Composition in TiFe+ 4 wt.% Zr Alloys by Scanning Photoemission Microscopy. Inorganics 2023, 11, 26.

- Miller, H.I.; Murray, J.; Laury, E.; Reinhardt, J.; Goudy, A.J. The hydriding and dehydriding kinetics of FeTi and Fe0.9TiMn0.1. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 1995, 231, 670-674. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wu, J.; Wang, Q. Reactivation behaviour of TiFe hydride. Journal of alloys and compounds 1994, 215, 91-95.

- Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Sun, P.; Zhou, C.; Liu, Y.; Fang, Z.Z. The mechanistic role of Ti4Fe2O1-x phases in the activation of TiFe alloys for hydrogen storage. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 32011-32024. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Gao, X.; Liu, B.; Wei, X.; Zhang, W.; Lan, Y.; Wang, H.; Yuan, Z. Effects of Zr doping on activation capability and hydrogen storage performances of TiFe-based alloy. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 2256-2270. [CrossRef]

- Lv, P.; Liu, Z.; Dixit, V. Improved hydrogen storage properties of TiFe alloy by doping (Zr+2V) additive and using mechanical deformation. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 27843-27852. [CrossRef]

- Park, K.B.; Ko, W.-S.; Fadonougbo, J.O.; Na, T.-W.; Im, H.-T.; Park, J.-Y.; Kang, J.-W.; Kang, H.-S.; Park, C.-S.; Park, H.-K. Effect of Fe substitution by Mn and Cr on first hydrogenation kinetics of air-exposed TiFe-based hydrogen storage alloy. Materials Characterization 2021, 178, 111246. [CrossRef]

- Dematteis, E.M.; Dreistadt, D.M.; Capurso, G.; Jepsen, J.; Cuevas, F.; Latroche, M. Fundamental hydrogen storage properties of TiFe-alloy with partial substitution of Fe by Ti and Mn. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2021, 874, 159925. [CrossRef]

- Padhee, S.P.; Roy, A.; Pati, S. Role of Mn-substitution towards the enhanced hydrogen storage performance in FeTi. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 9357-9371. [CrossRef]

- Gosselin, C.; Huot, J. First hydrogenation enhancement in TiFe alloys for hydrogen storage doped with yttrium. Metals 2019, 9, 242.

- Emami, H.; Edalati, K.; Matsuda, J.; Akiba, E.; Horita, Z. Hydrogen storage performance of TiFe after processing by ball milling. Acta Materialia 2015, 88, 190-195. [CrossRef]

- Falcão, R.B.; Dammann, E.D.C.C.; Rocha, C.J.; Durazzo, M.; Ichikawa, R.U.; Martinez, L.G.; Botta, W.J.; Leal Neto, R.M. An alternative route to produce easily activated nanocrystalline TiFe powder. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 16107-16116. [CrossRef]

- Vega, L.; Leiva, D.; Neto, R.L.; Silva, W.; Silva, R.; Ishikawa, T.; Kiminami, C.; Botta, W. Mechanical activation of TiFe for hydrogen storage by cold rolling under inert atmosphere. international journal of hydrogen energy 2018, 43, 2913-2918.

- Ulate-Kolitsky, E.; Tougas, B.; Neumann, B.; Schade, C.; Huot, J. First hydrogenation of mechanically processed TiFe-based alloy synthesized by gas atomization. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 7381-7389. [CrossRef]

- Edalati, K.; Matsuda, J.; Iwaoka, H.; Toh, S.; Akiba, E.; Horita, Z. High-pressure torsion of TiFe intermetallics for activation of hydrogen storage at room temperature with heterogeneous nanostructure. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 4622-4627. [CrossRef]

- Park, K.B.; Fadonougbo, J.O.; Na, T.-W.; Lee, T.W.; Kim, M.; Lee, D.H.; Kwon, H.G.; Park, C.-S.; Do Kim, Y.; Park, H.-K. On the first hydrogenation kinetics and mechanisms of a TiFe0.85Cr0.15 alloy produced by gas atomization. Materials Characterization 2022, 192, 112188. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Kwon, H.G.; Park, K.B.; Im, H.-T.; Kwak, R.H.; Sohn, S.S.; Park, H.-K.; Fadonougbo, J.O. Phase formation behavior and hydrogen sorption characteristics of TiFe0.8Mn0.2 powders prepared by gas atomization. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 27697-27709. [CrossRef]

- Nong, Z.-S.; Zhu, J.-C.; Yang, X.-W.; Cao, Y.; Lai, Z.-H.; Liu, Y. First-principles study of hydrogen storage and diffusion in B2 FeTi alloy. Computational Materials Science 2014, 81, 517-523. [CrossRef]

- Lebsanft, E.; Richter, D.; Topler, J. Investigation of the hydrogen diffusion in FeTiHx by means of quasielastic neutron scattering. Journal of Physics F: Metal Physics 1979, 9, 1057. [CrossRef]

- Bowman Jr, R.C.; Tadlock, W.E. Hydrogen diffusion in β-phase titanium iron hydride. Solid State Communications 1979, 32, 313-318.

- Chung, H.; Lee, J.-Y. Effect of partial substitution of Mn and Ni for Fe in FeTi on hydriding kinetics. International journal of hydrogen energy 1986, 11, 335-339.

- Hosseinigourajoubi, S.; Schade, C.; Huot, J. The Effect of Annealing on the First Hydrogenation Behavior of Atomized Ti48.8Fe46.0Mn5.2 Alloy. Metals 2025, 15, 251.

- Manna, J.; Tougas, B.; Huot, J. Mechanical activation of air exposed TiFe + 4 wt% Zr alloy for hydrogenation by cold rolling and ball milling. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 20795-20800. [CrossRef]

- Vega, L.E.R.; Leiva, D.R.; Leal Neto, R.M.; Silva, W.B.; Silva, R.A.; Ishikawa, T.T.; Kiminami, C.S.; Botta, W.J. Mechanical activation of TiFe for hydrogen storage by cold rolling under inert atmosphere. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 2913-2918. [CrossRef]

- Tousignant, M.; Huot, J. Hydrogen sorption enhancement in cold rolled LaNi5. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2014, 595, 22-27. [CrossRef]

- Lima, G.F.; Triques, M.R.M.; Kiminami, C.S.; Botta, W.J.; Jorge, A.M. Hydrogen storage properties of pure Mg after the combined processes of ECAP and cold-rolling. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2014, 586, S405-S408. [CrossRef]

- Floriano, R.; Leiva, D.R.; Carvalho, J.A.; Ishikawa, T.T.; Botta, W.J. Cold rolling under inert atmosphere: A powerful tool for Mg activation. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 4959-4965. [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Jimenez, J.; Cubero-Sesin, J.M.; Edalati, K.; Khajavi, S.; Huot, J. Effect of high-pressure torsion on first hydrogenation of Laves phase Ti0.5Zr0.5(Mn1-xFex)Cr1 (x = 0, 0.2 and 0.4) high entropy alloys. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2023, 969, 172243. [CrossRef]

- Rudman, P. Hydrogen-diffusion-rate-limited hydriding and dehydriding kinetics. Journal of Applied Physics 1979, 50, 7195-7199.

- Huston, E.L.; Sandrock, G.D. Engineering properties of metal hydrides. Journal of the Less Common Metals 1980, 74, 435-443. [CrossRef]

- Sleiman, S.; Shahgaldi, S.; Huot, J. Investigation of the First Hydrogenation of LaNi5. Reactions 2024, 5, 419-428.

- Jai-Young, L.; Park, C.N.; Pyun, S.M. The activation processes and hydriding kinetics of FeTi. Journal of the Less Common Metals 1983, 89, 163-168. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).