1. Introduction

Effective anesthesia and pain management are essential to ensure animal welfare and safety, as well as to minimize stress, risks, and complications. Each phase of anesthesia is crucial not only for animal well-being but also for the success of the procedure and the reliability of the resulting data. In orthopedic research, sheep are widely accepted as an in vivo model for investigating the biomechanical, biochemical, and histological processes of bone biology [

1,

2,

3]. This species shows a high degree of similarity to humans in terms of bone and joint structure, as well as bone remodeling processes [

4,

5], making it particularly suitable for studies involving bone healing and orthopedic interventions. However, anesthetic procedures in sheep can be associated with unexpected adverse events, including fermentation and ruminal bloating, regurgitation with the risk of aspiration, and pulmonary edema linked to the systemic use of α-2 adrenergic agonists [

6]. To reduce or prevent these complications, the implementation of a multimodal anesthesia protocol is strongly recommended. This approach ensures effective, procedure-specific pain management tailored to the individual animal, while simultaneously minimizing the incidence of anesthesia-related complications. In accordance with current legislation on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes (Directive 2010/63/EU), anesthesia is fundamental not only for ensuring animal welfare but also for adhering to the principles of the 3Rs: Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement. Within this context, spinal anesthesia has emerged as a valuable technique for orthopedic procedures — particularly those involving the hind limbs — due to its ability to provide reliable and targeted analgesia [

7,

8]. This procedure of regional anesthesia involves the direct injection of a local anesthetic into the subarachnoid space, a technique first introduced in the late 1800s. In small ruminants, the subarachnoid space is readily accessible via the lumbosacral intervertebral space (L6–S1), making spinal anesthesia a practical and effective technique in veterinary medicine [

9,

10]. Intrathecal administration of anesthetic and analgesic agents primarily acts at the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, modulating nociceptive transmission. Several drug classes can induce analgesia when administered intrathecally, including local anesthetics, opioids, α2-adrenergic agonists, and dissociative agents such as ketamine [

11,

12]. Among these, lidocaine is one of the most widely used local anesthetic for both epidural and subarachnoid anesthesia in small ruminants. It is routinely employed for procedures involving the lower flank, hind limbs, perineum, rectum, and tail. Its mechanism involves blocking voltage-gated Na⁺, Ca²⁺, and K⁺ channels in dorsal horn sensory neurons, resulting in a reversible blockade of sensory, sympathetic, and motor fibers, it has a quick onset and a mean duration of 60-120 minutes [

13,

14]. Spinal anesthesia has undergone significant refinement with the development of safer, more selective agents and optimized clinical protocols. The co-administration of adjuvants with local anesthetics has further improved analgesic efficacy and prolonged block duration, representing a notable advancement in perioperative pain management [

14]. Intrathecal α2-adrenergic agonists are commonly employed as adjuvants to local anesthetics, as they enhance anesthetic efficacy and consent to a reduction in the required dose of the primary agent [

15,

16]. Clonidine, a partial α2-adrenoreceptor agonist, has been extensively studied for intrathecal use and is associated with a favorable safety and efficacy profile [

17]. When combined with local anesthetics, clonidine significantly prolongs the duration of both sensory and motor spinal blockade [

15,

16,

18].

Dexmedetomidine, a highly selective α2-adrenoreceptor agonist used for intravenous sedation and analgesia enhancement, has been found to exhibit an α2/α1 selectivity ratio eight times greater than that of clonidine, suggesting that a potentially enhanced effect could be achieved when it is used intrathecally [

19].

The aim of this study is to compare the efficacy of clonidine and dexmedetomidine as adjuvants to lidocaine for spinal anesthesia. Our hypothesis is that dexmedetomidine could be more effective than clonidine in prolonging the sensory and motor blokade of lidocaine. To test our hypothesis, motor, sensory and analgesic effects were monitored in the postoperative period in sheep undergoing orthopedic surgery under spinal anesthesia.

2. Materials and Methods

This prospective, randomized, double-blind, experimental study involved 39 sheep undergoing experimental pelvic limb cartilage damage surgery for the application of an osteochondral scaffold and was approved by Ministerial Authorizations n°76/2023-PR and n°263/2023-PR. It was conducted at the Section of Veterinary Clinics and Animal Production of DiMePRe-J at University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, Italy. The sheep were adult females of the Gentile di Puglia breed, weighing 50 kg. They were fasted for 48 hours before surgery [

20]. After the application of an intravenous (IV) catheter in the auricular vein (DeltaVen 20G, Delta Med S.p.A., Viadana, Mn, Italy), sheep were sedated administering diazepam (0.4 mg kg

-1, Ziapam 5mg mL

-1, Ecuphar S.R.L., Milano, Italy) and buprenorphine (10 µ

-g Kg

1, Bupaq 0.3 mg mL

-1, Livisto, Modena, Italy) IV. They were positioned on the surgery table on lateral decubitus with the treated limb in dependent position for the execution of the lumbosacral spinal block. Meanwhile, the head was positioned on a pillow, and a sandbag was placed under the cervical region, to slightly elevate it and to allow saliva drainage. A towel was placed over their eyes to keep them calm. Animal were continuously supported with oxygen 100% delivered via face mask (12 L min

-1) and fluid therapy (Ringer Lactate, Baxter S.p.A., Rome, Italy) at a rate of 5-10 mL kg

-1 hour

-1. Pre-operative antibiotic and anti-inflammatory therapy were also guaranteed by administering benzilpenicillin+diidrostreptomicin by injection into muscle (5 mL, Repen 200.000 U.I. mL

-1+ 250 mg mL

-1, Fatro S.p.A., Italy) and flunixin (1 mg kg

-1, Emdofluxin 50 mg mL

-1) IV.

During the procedure the animals were gently restrained, and the depth of anesthesia was assessed using the intraoperative sedation scale, a numerical descriptive scale from 1 (calm and quiet patient requires no additional sedation or restraint) to 3 (patient agitated, moves and requires additional sedation) (

Table 1). A dose of 0.5 mg kg

-1 of propofol (Proposure 10 mg mL

-1; Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health Italia S.p.A., Italy) was given intravenously in cases where the score was 3, in order to ensure an adequate depth of sedation.

For the execution of the spinal block, sheep were randomly divided into three groups of 13 animals. Randomization was performed using a predefined Excel document (simple random allocation sequence generated with the chit method) based on a 1:1:1 randomization scheme. Spinal anesthesia solutions were prepared by combining drugs in a 10 mL syringe as follows: 10 mL of lidocaine (Lidor 20 mg mL

-1, Livisto, Modena, Italy) for the L group; 8.7 mL of lidocaine + 1.3 mL of clonidine (20 μg mL

-1; Catapresan 150 mcg mL

-1, Boehringer Ingelheim IT S.p.A., Italy) for the CL group; 9.98 mL of lidocaine + 0.02 mL of dexmedetomidine (1 μg mL

-1; Dexdomitor 0.5 mg mL

-1, Orion corporation, Finland) for the LD group. These solutions were prepared by a veterinarian who was solely aware of group allocation and did not participate in intraoperative or postoperative assessments. Prior to the block execution, the lumbosacral area was surgically prepared, and the hind limbs were displaced cranially in order to evidence the spine and make the lumbosacral space more evident. After the localization of the iliac crests and the lumbosacral space, the spinal needle (BD quinke point 20G – 0.9x90mm, GIMA S.p.A., Milan, Italy) was advanced midline halfway between the spinous process of the last lumbar vertebra (L6) and the sacrum (S1) until it penetrated the dura-subarachnoid membranes. Then, the stylet was taken out of the spinal needle, and the right placement was confirmed by the free flow of cerebrospinal fluid. At this point, the assigned spinal solution was administered slowly at a dose of 1 mL every 10 kg. The success of the block was assessed by the loss of the anal sphincter tone. The animals were kept in lateral decubitus with the treated limb in a dependent position for 10 minutes. After this time, they were positioned for surgery. During the procedure, heart rate (HR, beats min

-1), respiratory rate (RR, breaths min

-1) and non-invasive mean arterial blood pressure (MAP, mmHg) were continuously monitored throughout the procedure to assess nociceptive responses, with baseline values determined prior to the start of surgery. An increase of ≥ 20 % in two of these parameters was interpreted as indicative of nociception and prompted the administration of rescue analgesia (fentanyl 10 μg kg⁻¹ IV) [

21]. If the monitored variables did not return to within 20% of baseline values within 5 minutes following the initial bolus, a second dose was administered. The block was deemed unsuccessful if more than three rescue boluses were required. In such cases, the animal was withdrawn from the study and provided with alternative analgesic management consisting of a continuous intravenous fentanyl infusion at a rate of 10 μg kg⁻¹ hr⁻¹ [

22]. In this case, the sheep was intubated and switched to inhalational anesthesia. Temperature (T,

°C) was also monitored and a warmer device (BairHugger

TM, 3M, Italy) was used when necessary to keep it at around 38°C.

At the end of the procedure, the animals went to the recovery box and the times (minute) of recovery of anal sphincter tone (AS), the occurrence of the first spontaneous limb movements (FMov), the first attempts to stand (FAtt) and the time of standing (ToS) from the spinal block were recorded. Moreover, the recovery of sensibility (RoS) was evaluated by observing the occurrence of a response to limb pinching with a 25G needle. After the standing, animals were observed every 10 minutes for one hour and the degree of ataxia (ATA10, ATA20, ATA30, ATA40, ATA50, ATA60) was measured using a numerical descriptive scale (1=absent; 2=mild; 3=severe) (

Table 2).

Pain was also assessed using the Sheep Grimace Scale, with a score from 0 to 3 given for each point considering the orbital tightening, the head and ear position and the presence of flehmen [

23]. A Grimace value

> 4 was considered a cut-off to require a rescue consisting of IV buprenorphine (10 μg kg

-1), and the time of its administration (

1stR) from ToS was recorded.

Sheep received antibiotic and anti-inflammatory therapy during the subsequent days of hospitalization. Following the initial 24-hour period after the procedure, buprenorphine was administered in conjunction with the therapeutic regimen, solely as a rescue treatment if the Grimace values indicated this was required.

2.1. Statistics

The sample size was calculated a priori accepting an alpha risk of 0.05 and a power of 0.9 in a two-tailed test. Twelve subjects were required in each of the three groups to detect as statistically significant a difference > 80 minute in the time of the first rescue administration from the spinal block. The common standard deviation was assumed to be 60. The calculation was performed using the Granmo software, version 8.0 (Institut Municipal d’Investigació Mèdica, Barcelona, Spain). All data were analyzed using MedCalc (12.7.0.0 version) and Jamovi (2.3.28 version) software. The normal distribution of data was verified using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Intra-operative monitored values, RoS, AS, FMov, FAtt, ToS and 1stR were calculated as mean ± standard deviation; ATA as median and interquartile range (IQR; 25th-75th percentile).

Two-way ANOVA was used to compare the intra-operative monitored values and the time of RoS, AS, FAtt, FMov, ToS, and 1stR between groups. The post-hoc analysis was performed with the Tukey test. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare boluses of propofol and ATA values between groups. P < 0.05.

3. Results

The duration of the surgical procedures was 30.6 ± 10.9 minutes in the L group, 31.1 ± 13.1 minutes in the LD group, and 30.5 ± 11 minutes in the CL group. The median number of propofol boluses administered was 3 (IQR: 2–4) in the L group, 3 (2–4) in the LD group, and 3 (2–4) in the CL group. The spinal block technique was easy to perform, requiring a single attempt in all sheep, and none of the animals required additional intraoperative analgesia, confirming the success of the block. The recovery from the block was uneventful, all animals completed the study without complications, and none were excluded. Intraoperative measurements of HR, MAP, RR, T, and peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO₂) are summarized in

Table 3. No statistically significant differences were observed among the three groups for any of these parameters at corresponding time points during the procedure.

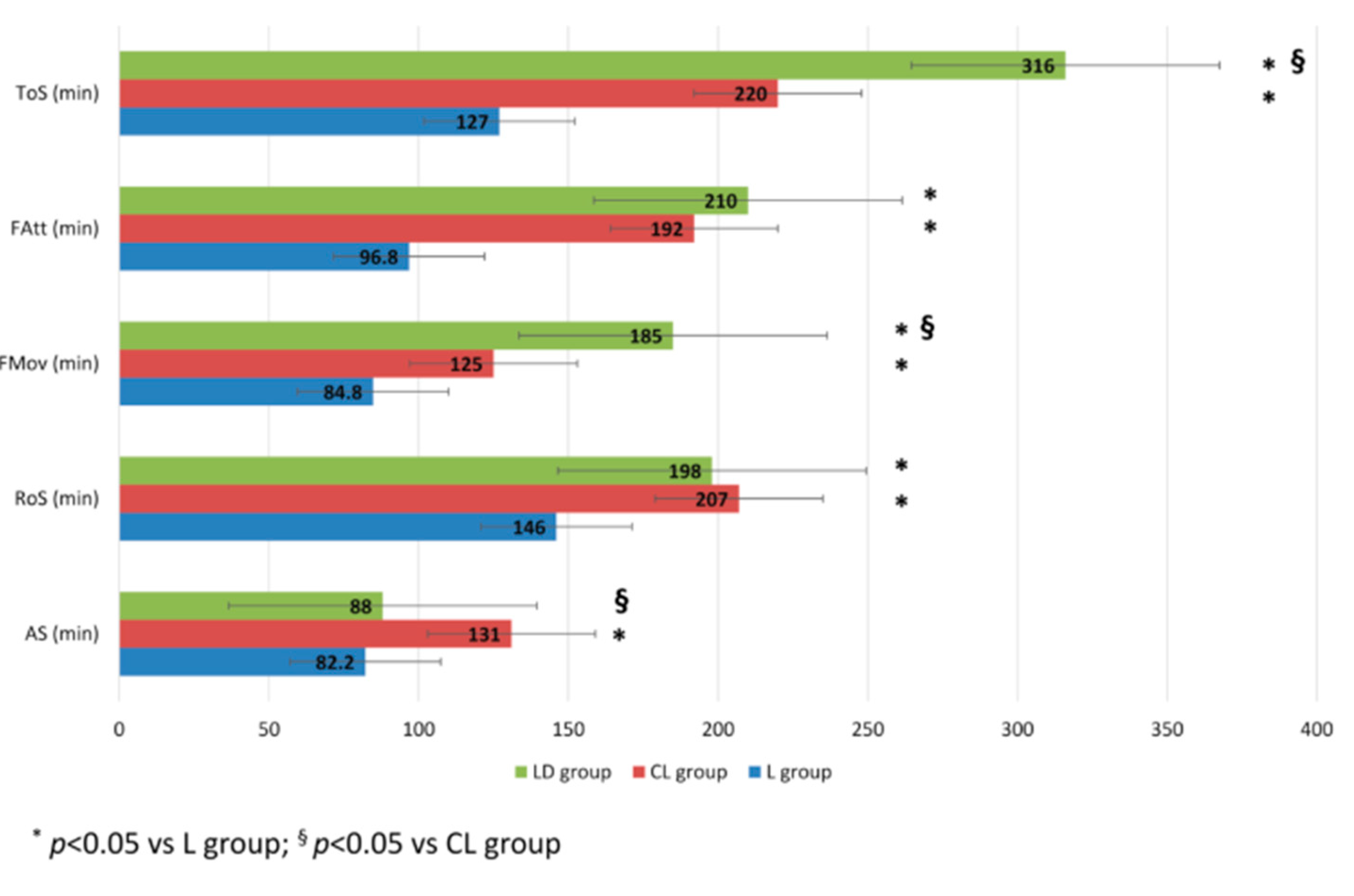

The recovery time of AS from the spinal block was 82.2 ± 15.1 minutes in L group, 131 ± 28 minutes in CL group and 88 ± 51.5 minutes in LD group. A statistically significant difference was observed between CL group and both L group (p < 0.001) and LD group (p = 0.015). The times of FMov were 84.8 ± 29 minutes in L group, 125 ± 14.6 minutes in CL group and 185 ± 63 minutes in LD group. Statistically significant differences were found among groups (p < 0.001 for L group vs CL group and LD group; p = 0.03 for CL group vs LD group). The times of FAtt were 96.8 ± 27.9 minutes in L group, 192 ± 44.2 minutes in CL group and 210 ± 60.1 minutes in LD group, with statistically significant differences between L group and both CL group and LD group (p < 0.001). The ToS occurred at 127 ± 25.2 minutes in L group, 220 ± 35.7 minutes in CL group and 316 ± 80.3 minutes in LD group. A statistically significant difference was found among the three groups (p < 0.001). The RoS from the spinal block was 146 ± 21.8 minutes in L group, 207 ± 27.1 minutes in CL group and 198 ± 60.4 minutes in LD group, with a statistically significant difference for L group compared to the other two groups (p < 0.001 for L group vs CL group and p < 0.008 for L group vs LD group). These data are presented in

Table 4 and illustrated in

Figure 1.

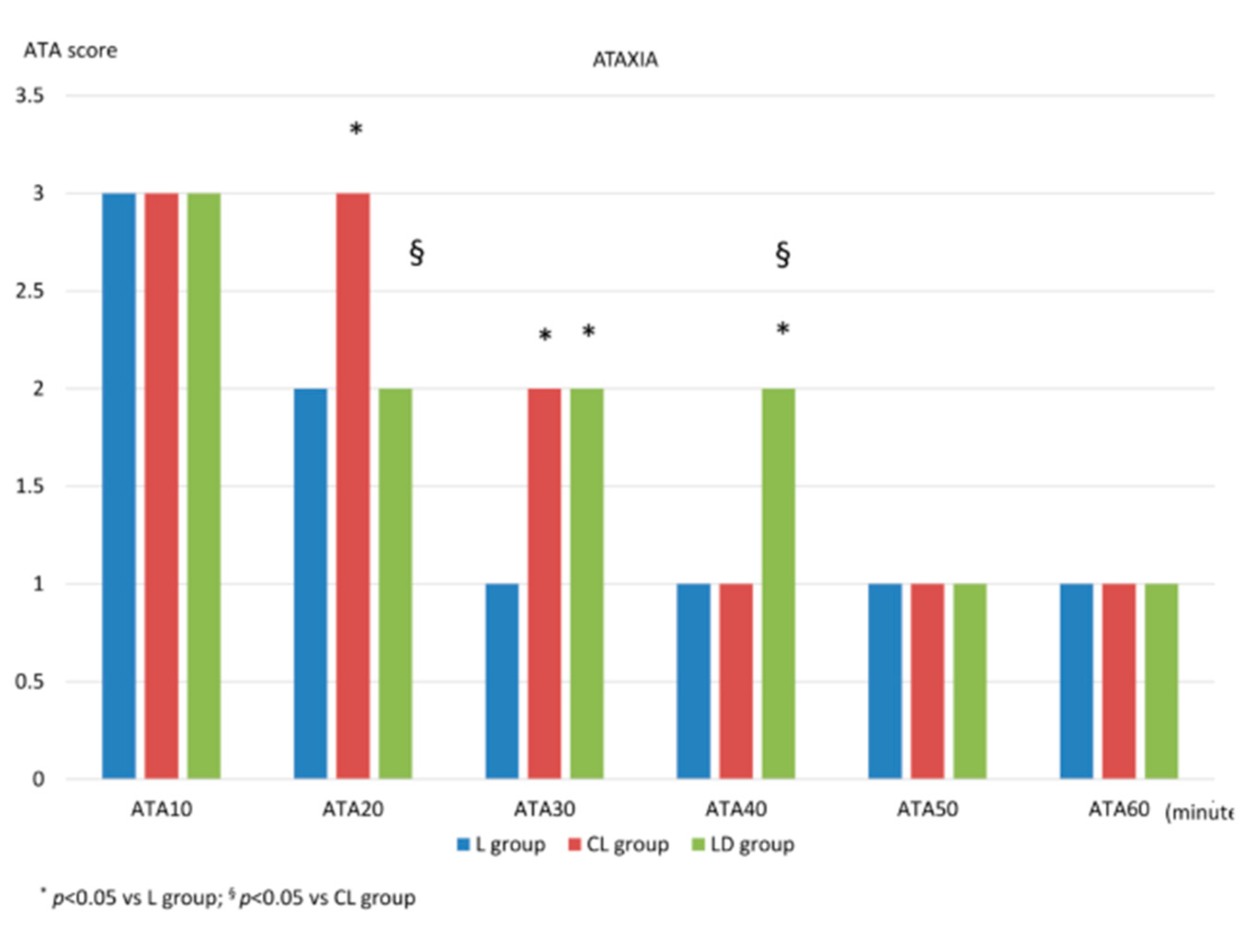

After standing, at ATA10 all the three groups exhibited severe ataxia, with a score of 3, and no statistically significant differences were observed among the groups. At ATA20, the score was 2 (2-1) for L group, 3 (3-2) for CL group and 2 (2-2) for LD group, with a statistically significant difference for CL group compared to both L group (p < 0.001) and LD group (p = 0.02). At ATA30, the score was 1 (2-1) for L group, 2 (3-2) for CL group and 2 (2-2) for LD group. At this time point, a statistically significant difference was found between L group and the other two groups (p < 0.001 vs CL group; p = 0.004 vs LD group). At ATA40, the score was 1 (1-1) for L group, 1 (2-1) for CL group and 2 (2-2) for LD group, with a statistically significant difference observed for LD group compared to the other two groups (p < 0.001). At ATA50 and ATA60 all groups reached a score of 1 (1-1), with no statistically significant differences among them. These data are presented in

Table 4 and illustrated in

Figure 2.

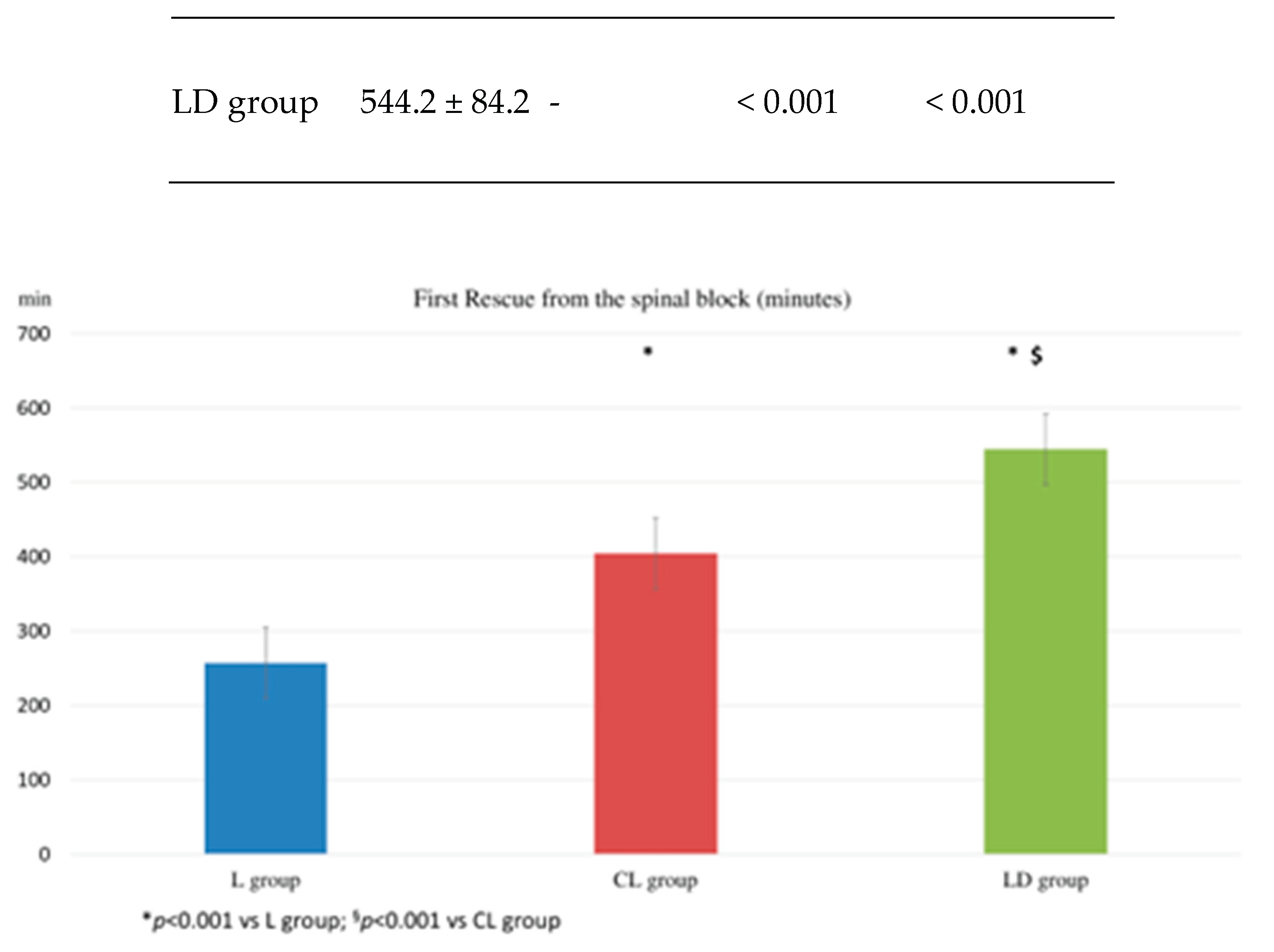

The first analgesic administration (

1stR) after the spinal block was 257.2 ± 65.7 minutes in L group, 404.2 ± 47.7 in CL group and 544.2 ± 84.2 minutes in LD group (p <.001). These data are presented in

Table 5 and illustrated in

Figure 3.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that spinal anesthesia, whether performed with lidocaine alone or in combination with the adjuvants clonidine or dexmedetomidine, can be considered an effective and reliable analgesic strategy for experimental orthopedic surgeries involving the hind limbs. Across all three treatment groups, intraoperative hemodynamic parameters remained stable, and none of the animals required additional intraoperative analgesia, confirming the success of the spinal block.

In the postoperative phase, animals in LD group exhibited a longer recovery of the motor function and a prolonged ataxic phase compared to those in L and CL groups. Notably, LD group also showed a delayed onset of pain following standing and consequently required rescue analgesia at a later time point compared to the other groups.

The most relevant outcome of this study concerns the analgesic effect, which was of longer duration in the groups receiving α2-agonist adjuvants. These findings are consistent with other studies in sheep and other species, showing that the analgesic effect of α2-agonists is related to both a direct action on the spinal cord and an “indirect” synergistic effect with the local anesthetic. Several studies in human medicine have evaluated dexmedetomidine and clonidine as adjuvants in spinal blocks with various local anesthetics, reporting that dexmedetomidine significantly prolongs the duration of motor and sensory blockade and delays the time to first analgesic request [

24,

25,

26]. Multiple mechanisms may underlie the analgesic action of these agents, including direct stimulation of α2-adrenoreceptors in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, which inhibits substance P and other nociceptive neurotransmitters, modulation of cholinergic pathways, alteration of nociceptive impulse transmission, and both direct local anesthetic–like effects and potentiation of co-administered local anesthetics [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. The longer duration of both sensory and motor blockade observed in the LD group compared to the CL group may be explained by the differing pharmacological profiles of dexmedetomidine and clonidine. Clonidine, a partial α2-adrenoreceptor agonist, provides analgesia primarily through inhibition of C-fiber neurotransmitter release and hyperpolarization of postsynaptic neurons in the dorsal horn [

27]. In contrast, dexmedetomidine is a second-generation, highly selective α2A-adrenoceptor agonist, which provides greater analgesic potency at lower doses due to its higher receptor selectivity—approximately eightfold that of clonidine [

32,

33,

34]. This difference was further reflected in the postoperative phase. In addition, studies in other veterinary species have highlighted the synergistic effect of dexmedetomidine with local anesthetics, not only when administered at the site of local anesthetic injection, but also systemically via intramuscular or intravenous routes [

35,

36].

Bradycardia and hypotension have been reported as side effects following intrathecal administration of α2-agonists in humans [

37,

38]. In the present study, none of the treatment groups exhibited these hemodynamic alterations. Eisenach and Tong (1991) investigated the hemodynamic effects of clonidine administered intrathecally at different spinal levels (cervical, thoracic, and lumbar) in sheep [

39]. Their results showed that the most pronounced hypotensive effects occurred following cervical and thoracic administration, whereas lumbar administration caused only a mild decrease in heart rate. Moreover, they observed a dose-dependent relationship, with more significant hemodynamic changes at higher doses of clonidine. Eisenach et al. (1994) reported hypotension following intrathecal administration of 100 μg of dexmedetomidine; in contrast, our study used a dose of 5 μg per sheep [

40]. These differences in dosage, along with the lumbar site of injection, may explain the hemodynamic stability observed in our study when using clonidine and dexmedetomidine as adjuvants.

Regarding motor blockade, the time of standing was prolonged in groups receiving α2-agonists, which was associated with more severe ataxia. Several studies on intrathecal administration of α2-agonists in sheep and goats have reported prolonged sternal recumbency and persistent ataxia in animals receiving α2-agonists combined with local anesthetics [

41,

42]. This phenomenon has been attributed to secondary central effects on the locus coeruleus, likely due to systemic absorption through vascular and lymphatic pathways. These effects include sedation and muscle relaxation, in addition to the primary local anesthetic action at the spinal level [

41]. The findings of the present study are consistent with these observations.

It is important to note that prolonged recovery, characterized by extended sternal recumbency and persistent ataxia, may pose significant risks. Potential complications include myopathies, neuropathies, excessive ruminal fermentation, or trauma during the ataxic phase, especially if the animals are not adequately restrained [

43].

Furthermore, based on the findings of this study, the selection of clonidine or dexmedetomidine as intrathecal adjuvants could be more effectively tailored to the nature and the expected duration of the surgical procedure. Dexmedetomidine could be the drug of choice for extended surgeries, but its administration demands close postoperative monitoring to manage the risk related to prolonged ataxia. In contrast, when minimizing motor impairment and facilitating recovery are priorities, clonidine could represent a more appropriate option, while still providing satisfactory postoperative analgesia.

5. Conclusions

Spinal anesthesia proved to be an effective technique for experimental orthopedic procedures in sheep, with lidocaine alone being effective for short procedures, lasting around 30 minutes. Additionally, clonidine and dexmedetomidine were found to be effective intrathecal adjuvants in prolonging motor and sensory blockade, as well as enhancing postoperative analgesia. However, their different pharmacodynamic profiles may influence clinical decision-making. Dexmedetomidine could be more suitable for longer procedures due to its prolonged effects, though it may require closer postoperative monitoring to manage extended ataxia and recumbency. In contrast, clonidine could offer a safer alternative when faster recovery and reduced motor impairment are desired, without compromising postoperative analgesia. These findings highlight the importance of tailoring adjuvant selection to the specific surgical context and recovery needs. Moreover, the use of these α-2 agonists as adjuvants may contribute to the refinement of spinal anesthesia protocols, enhancing the balance between anesthetic efficacy, animal welfare, and postoperative management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P. and F.S.; Methodology, C.P., C.V. and F.S.; Software, C.P.; Validation, C.P., C.V., M.S. and F.S.; Formal Analysis, C.P.; Investigation, C.P., C.V., R.P. and M.S.; Resources, A.M.C., M.G., L.L. and F.S.; Data Curation, C.P., C.V. and M.S.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, C.P.; Writing – Review & Editing, C.P., C.V. and F.S; Visualization, C.P.; Supervision, F.S.; Project Administration, A.M.C., M.G., L.L. and F.S.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by Ministerial Authorizations n°76/2023-PR and n°263/2023-PR.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of Agata Fraccascia, Simeone Iurlo and Nicola Filipponio. Their contributions during the experimental procedures were essential to the successful completion of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| L group |

Lidocaine group |

| CL group |

Lidocaine + clonidine group |

| LD group |

Lidocaine + dexmedetomidine group |

| AS |

Return of the anal sphincter tone |

| RoS |

Recovery of senstbility |

| FMov |

First limb movements |

| ToS |

Time of standing |

| ATA |

Ataxia |

| IV |

Intravenous |

| HR |

Heart rate |

| RR |

Respiratory rate |

| MAP |

Mean arterial blood pressure |

| T |

Temperature |

| FAtt |

First attempt to stand |

|

1stR |

First rescue analgesia administration |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of Variance |

| IQR |

Interquartile range |

| SpO2

|

Peripheral oxygen saturation |

| PREMED |

premedication |

References

- Martini, L.; Fini, M.; Giavaresi, G.; Giardino, R. Sheep model in orthopedic research: a literature review. Comp Med. 2001, 51(4), 292–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pearce, A.I.; Richards, R.G.; Milz, S.; Schneider, E.; Pearce, S.G. Animal models for implant biomaterial research in bone: a review. Eur Cell Mater. 2007, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potes, J.C.; Reis, J.; Capela e Silva, F.; Relvas, C.; Cabrita, A.; Simoes, J. The sheep as an animal model in orthopaedic research. Exp. Pathol. Health Sci. 2015, 2008 2, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, I.R.; Camassa, J.A.; Bordelo, J.A.; Babo, P.S.; Viegas, C.A.; Dourado, N.; Reis, R.L.; Gomes, M.E. Preclinical and Translational Studies in Small Ruminants (Sheep and Goat) as Models for Osteoporosis Research. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2018, 16(2), 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarrinkalam, M.R.; Beard, H.; Schultz, C.G.; Moore, R.J. Validation of the sheep as a large animal model for the study of vertebral osteoporosis. Eur Spine J. 2009, 18(2), 244–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.C.; Tyler, J.W.; Wallace, S.S.; Thurmon, J.C.; Wolfe, D.F. Telazol and xylazine anesthesia in sheep. Cornell Vet. 1993, 83(2), 117–24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Staffieri, F.; Driessen, B.; Lacitignola, L.; Crovace, A. A comparison of subarachnoid buprenorphine or xylazine as an adjunct to lidocaine for analgesia in goats. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2009, 36(5), 502–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch, N.B.; Darrith, B.; Hansen, D.C.; Wells, A.; Sanders, S.; Berger, R.A. Single-dose lidocaine spinal anesthesia in hip and knee arthroplasty. Arthroplast Today. 2018, 4(2), 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Crovace, A.; Di Bello A.; Boscia, D.; Mastronardi, A. Rachianestesia lombosacrale negli ovini. In Summa VI.I, 1989; pp. 49-51.

- Skarda, R.T.; Tranquilli, W.J.; Lumb.

Local and regional anesthetics and analgesic techniques: ruminants and swine

. In Jones’ Veterinary Anesthesia and Analgesia, 4th edn; Blackwell Publishing: Ames, IA, USA, 2007; pp. 643–681. [Google Scholar]

- Chiari, A.; Eisenach, J.C. Spinal anesthesia: mechanisms, agents, methods, and safety. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 1998, 23(4), 357–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linderoth, B.; Foreman, R.D. Physiology of spinal cord stimulation: review and update. Neuromodulation. 1999, 2(3), 150–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olschewski, A.; Schnoebel-Ehehalt, R.; Li, Y.; Tang, B.; Bräu, M.E.; Wolff, M. Mexiletine and lidocaine suppress the excitability of dorsal horn neurons. Anesth Analg. 2009, 109(1), 258–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierson, D.; Certoma, R.; Hobbs, J.; Cong, X.; Li, J. A Narrative Review on Multimodal Spinal Anesthesia: Old Technique and New Use. J Anesth Transl Med.;Epub 2025, 4(1), 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- De Kock, M.; Gautier, P.; Fanard, L.; Hody, J.L.; Lavand'homme, P. Intrathecal ropivacaine and clonidine for ambulatory knee arthroscopy: a dose-response study. Anesthesiology 2001, 94(4), 574–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrydnjov, I.; Axelsson, K.; Samarütel, J.; Holmström, B. Postoperative pain relief following intrathecal bupivacaine combined with intrathecal or oral clonidine. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2002, 46(7), 806–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heydinger, G.; Bayer, E.E.; Roth, C.; Kitio, S.A.Y.; Jayanthi, V.R.; Thung, A.; Tobias, J.D.; Veneziano, G. Safety of Intrathecal Clonidine as an Adjuvant to Spinal Anesthesia in Infants and Children. Paediatr Anaesth 2025, 35(5), 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dobrydnjov, I.; Axelsson, K.; Thörn, S.E.; Matthiesen, P.; Klockhoff, H.; Holmström, B.; Gupta, A. Clonidine combined with small-dose bupivacaine during spinal anesthesia for inguinal herniorrhaphy: a randomized double-blinded study. Anesth Analg. 2003, 96(5), 1496–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coursin, D.B.; Coursin, D.B.; Maccioli, G.A. Dexmedetomidine. Curr Opin Crit Care 2001, 7(4), 221–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trimmel, N.E.; Hierweger, M.M.; Jucker, S.; Windhofer, L.; Weisskopf, M. Physiologic Effects of Prolonged Terminal Anesthesia in Sheep (Ovis gmelini aries). Comp Med 2022, 72(4), 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stenger, V.; Zeiter, S.; Buchholz, T.; Arens, D.; Spadavecchia, C.; Schüpbach-Regula, G.; Rohrbach, H. Is a Block of the Femoral and Sciatic Nerves an Alternative to Epidural Analgesia in Sheep Undergoing Orthopaedic Hind Limb Surgery? A Prospective, Randomized, Double Blinded Experimental Trial. Animals (Basel) 2021, 11(9), 2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Funes, F.J.; Granados Mdel, M.; Morgaz, J.; Navarrete, R.; Fernández-Sarmiento, A.; Gómez-Villamandos, R.; Muñoz, P.; Quirós, S.; Carrillo, J.M.; López-Villalba, I.; Dominguez, J.M. Anaesthetic and cardiorespiratory effects of a constant rate infusion of fentanyl in isoflurane-anaesthetized sheep. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2015, 42(2), 157–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häger, C.; Biernot, S.; Buettner, M.; Glage, S.; Keubler, L.M.; Held, N.; Bleich, E.M.; Otto, K.; Müller, C.W.; Decker, S.; Talbot, S.R.; Bleich, A. The Sheep Grimace Scale as an indicator of post-operative distress and pain in laboratory sheep. PLoS One 2017, 12(4), e0175839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ganesh, M.; Krishnamurthy, D. A Comparative Study of Dexmedetomidine and Clonidine as an Adjuvant to Intrathecal Bupivacaine in Lower Abdominal Surgeries. Anesth Essays Res. 2018, 12(2), 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, S.; Zhao, P.; Cui, Y.; Lu, C.; Ji, M.; Liu, W.; Jiang, W.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, Q. Effect of 5-μg Dose of Dexmedetomidine in Combination With Intrathecal Bupivacaine on Spinal Anesthesia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Ther. 2020, 42(4), 676–690.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoharan, M.M.; Paneer, M.; Elavarasan, K.; Kannappan Punniyakoti, K. Dexmedetomidine Versus Clonidine as Additives for Spinal Anesthesia: A Comparative Study. Anesth Pain Med. 2023, 13(4), e138274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Eisenach, J.C.; De Kock, M; Klimscha, W. alpha(2)-adrenergic agonists for regional anesthesia. A clinical review of clonidine (1984-1995). Anesthesiology 1996, 85(3), 655–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, J.C.; Thurmon, J.C.; Benson, J.G.; Tranquilli, W.J.; Olson, W.A. Evaluation of analgesia induced by epidural injection of detomidine or xylazine in swine. J Vet Anaesth. 1992, 19, 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Paqueron, X.; Li, X.; Bantel, C.; Tobin, J.R.; Voytko, M.L.; Eisenach, J.C. An obligatory role for spinal cholinergic neurons in the antiallodynic effects of clonidine after peripheral nerve injury. Anesthesiology. 2001, 94(6), 1074–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeRossi, R.; Junqueira, A.L.; Beretta, M.P. Analgesic and systemic effects of ketamine, xylazine, and lidocaine after subarachnoid administration in goats. Am J Vet Res 2003, 64(1), 51–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murrell, J.C.; Hellebrekers, L.J. Medetomidine and dexmedetomidine: a review of cardiovascular effects and antinociceptive properties in the dog. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2005, 32(3), 117–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenach, J.C.; De Kock, M.; Klimscha, W. alpha(2)-adrenergic agonists for regional anesthesia. A clinical review of clonidine (1984-1995). Anesthesiology 1996, 85(3), 655–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanazi, G.E.; Aouad, M.T.; Jabbour-Khoury, S.I.; Al Jazzar, M.D.; Alameddine, M.M.; Al-Yaman, R.; Bulbul, M.; Baraka, A.S. Effect of low-dose dexmedetomidine or clonidine on the characteristics of bupivacaine spinal block. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006, 50(2), 222–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratiwi, D.S.; I Made, A.K.; Senapathi, T.G.A. Dexmedetomidine Versus Clonidine as Adjuvants in Epidural Analgesia in Gynecological Laparotomy: Case Series. Bali J Anesthesiology. 2021, 5. 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquafredda, C.; Stabile, M.; Lacitignola, L.; Centonze, P.; Di Bella, C.; Crovace, A.; Fiorentino, M.; Staffieri, F. Clinical efficacy of dexmedetomidine combined with lidocaine for femoral and sciatic nerve blocks in dogs undergoing stifle surgery. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2021, 48(6), 962–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stabile, M.; Lacitignola, L.; Acquafredda, C.; Scardia, A.; Crovace, A.; Staffieri, F. Evaluation of a constant rate intravenous infusion of dexmedetomidine on the duration of a femoral and sciatic nerve block using lidocaine in dogs. Front Vet Sci. 2023, 9, 1061605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sarma, J.; Narayana, P.S.; Ganapathi, P.; Shivakumar, M.C. A comparative study of intrathecal clonidine and dexmedetomidine on characteristics of bupivacaine spinal block for lower limb surgeries. Anesth Essays Res. 2015, 9(2), 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shaikh, S.I.; Revur, L.R.; Mallappa, M. Comparison of Epidural Clonidine and Dexmedetomidine for Perioperative Analgesia in Combined Spinal Epidural Anesthesia with Intrathecal Levobupivacaine: A Randomized Controlled Double-blind Study. Anesth Essays Res. 2017, 11(2), 503–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Eisenach, J.C.; Tong, C.Y. Site of hemodynamic effects of intrathecal alpha 2-adrenergic agonists. Anesthesiology 1991, 74(4), 766–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenach, J.C.; Shafer, S.L.; Bucklin, B.A.; Jackson, C.; Kallio, A. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of intraspinal dexmedetomidine in sheep. Anesthesiology. 1994, 80(6), 1349–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeRossi, R.; Righetto, F.R.; Almeida, R.G.; Medeiros, U., Jr.; Frazílio, F.O. Clinical evaluation of clonidine added to lidocaine solution for subarachnoid analgesia in sheep. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 2006, 29(2), 113–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staffieri, F.; Driessen, B.; Lacitignola, L.; Crovace, A. A comparison of subarachnoid buprenorphine or xylazine as an adjunct to lidocaine for analgesia in goats. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2009, 36(5), 502–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costea, R.; Iancu, T.; Duțulescu, A.; Nicolae, C.; Leau, F.; Pavel, R. Critical key points for anesthesia in experimental research involving sheep (Ovis aries). Open Vet J.;Epub 2024, 14(9), 2129–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Figure 1.

Time of recovery from the spinal block. The times (minute) of recovery of the anal sphincter tone (AS), the recovery of sensibility (RoS), the occurrence of the first spontaneous limb movements (FMov), the first attempts to stand (FAtt) and the time of standing (ToS) recorded from the spinal block. (Lgroup: spinal lidocaine, CLgroup: spinal lidocaine+clonidine, LDgroup: spinal lidocaine+dexmedetomidine). *p < 0.05 vs Lgroup; §p < 0.05 vs CLgroup.

Figure 1.

Time of recovery from the spinal block. The times (minute) of recovery of the anal sphincter tone (AS), the recovery of sensibility (RoS), the occurrence of the first spontaneous limb movements (FMov), the first attempts to stand (FAtt) and the time of standing (ToS) recorded from the spinal block. (Lgroup: spinal lidocaine, CLgroup: spinal lidocaine+clonidine, LDgroup: spinal lidocaine+dexmedetomidine). *p < 0.05 vs Lgroup; §p < 0.05 vs CLgroup.

Figure 2.

Ataxia score after the standing. After the standing, the degree of ataxia was measured using a numerical descriptive scale: 1=absent; 2=mild; 3=severe, every 10 minutes for one hour (ATA10, ATA20, ATA30, ATA40, ATA50, ATA60). Lgroup: spinal lidocaine, CLgroup: spinal lidocaine+clonidine, LDgroup: spinal lidocaine+dexmedetomidine. *p < 0.05 vs Lgroup; §p < 0.05 vs CLgroup.

Figure 2.

Ataxia score after the standing. After the standing, the degree of ataxia was measured using a numerical descriptive scale: 1=absent; 2=mild; 3=severe, every 10 minutes for one hour (ATA10, ATA20, ATA30, ATA40, ATA50, ATA60). Lgroup: spinal lidocaine, CLgroup: spinal lidocaine+clonidine, LDgroup: spinal lidocaine+dexmedetomidine. *p < 0.05 vs Lgroup; §p < 0.05 vs CLgroup.

Figure 3.

First rescue administration from the spinal block. The time (minute) of the first rescue analgesia administration from the spinal block. (Lgroup: spinal lidocaine, CLgroup: spinal lidocaine+clonidine, LDgroup: spinal lidocaine+dexmedetomidine.) *p < 0.001 vs Lgroup; §p < 0.001 vs CLgroup.

Figure 3.

First rescue administration from the spinal block. The time (minute) of the first rescue analgesia administration from the spinal block. (Lgroup: spinal lidocaine, CLgroup: spinal lidocaine+clonidine, LDgroup: spinal lidocaine+dexmedetomidine.) *p < 0.001 vs Lgroup; §p < 0.001 vs CLgroup.

Table 1.

Intraoperative sedation score. Score used to evaluate the degree of sedation of the animals during the procedure. A bolus of propofol at a dose of 0.5 mg kg-1 was administered when the score was 3.

Table 1.

Intraoperative sedation score. Score used to evaluate the degree of sedation of the animals during the procedure. A bolus of propofol at a dose of 0.5 mg kg-1 was administered when the score was 3.

| Score |

Description |

| 1 |

calm and quiet patient requires no additional sedation or restraint |

| 2 |

patient requiring minimum phisical restraint |

| 3 |

patient agitated, moves and requires additional sedation |

Table 2.

Ataxia Score (ATA). The numerical descriptive scale used to assess the degree of ataxia after the standing.

Table 2.

Ataxia Score (ATA). The numerical descriptive scale used to assess the degree of ataxia after the standing.

| Score |

Description |

| 1 |

absent, when the patient could easily maintain the quadrupedal position and load weight on all four limbs |

| 2 |

mild, if the patient maintained the station, presented weakness in the hind limbs, could walk but staggering noticeably |

| 3 |

severe, if the patient had severe weakness in their hind limbs, could hold the standing position for a few minutes before falling backwards |

Table 3.

Physiological values recorded during anesthesia. Mean ± standard deviation of heart rate (HR, bpm), respiratory rate (RR, brpm), mean arterial pressure (MAP, mmHg), peripheral arterial blood oxygen saturation (SpO2, %), temperature (T, °C) recorded from premedication (PREMED) to the end of the procedure every 10 minutes for each group (Lgroup: spinal lidocaine, CLgroup: spinal lidocaine+clonidine, LDgroup: spinal lidocaine+dexmedetomidine).

Table 3.

Physiological values recorded during anesthesia. Mean ± standard deviation of heart rate (HR, bpm), respiratory rate (RR, brpm), mean arterial pressure (MAP, mmHg), peripheral arterial blood oxygen saturation (SpO2, %), temperature (T, °C) recorded from premedication (PREMED) to the end of the procedure every 10 minutes for each group (Lgroup: spinal lidocaine, CLgroup: spinal lidocaine+clonidine, LDgroup: spinal lidocaine+dexmedetomidine).

| |

GROUP |

PREMED |

T10 (spinal)

|

T20

|

T30

|

T40

|

| HR |

Lgroup |

127.7 ± 37.9 |

125 ± 29.6 |

114.4 ± 25.2 |

113 ± 28.3 |

115.5 ± 24.8 |

| (bpm) |

CLgroup |

125.3 ± 20.9 |

123.2 ± 21.9 |

120.5 ± 15.5 |

112.4 ± 18.4 |

104.3 ± 14.9 |

| |

LDgroup |

128.5 ± 24.8 |

126.5 ± 19.7 |

111.7 ± 25.2 |

115 ± 20.3 |

111.1 ± 9.4 |

| MAP |

Lgroup |

92.5 ± 34.9 |

91.2 ± 21.8 |

97.2 ± 20.7 |

84.6 ± 16.6 |

91 ± 15 |

| (mmHg) |

CLgroup |

98.7 ± 7.2 |

100.6 ± 15.2 |

92.1 ± 6.2 |

96.3 ± 11.3 |

92.7 ± 7.3 |

| |

LDgroup |

77 ± 9.8 |

79.5 ± 13.9 |

87.2 ± 10.2 |

86.2 ± 8.9 |

78.2 ± 4.8 |

| Spo2 |

Lgroup |

95.6 ± 2.8 |

95.1 ± 2.5 |

95 ± 3.6 |

94.7 ± 2.9 |

95.5 ± 3.6 |

| (%) |

CLgroup |

92.6 ± 2.5 |

92.3 ± 2.3 |

92.9 ± 2.1 |

91.5 ± 4.1 |

93.8 ± 3.2 |

| |

LDgroup |

95.7 ± 4.6 |

95.6 ± 4 |

95.1 ± 3.9 |

94.3 ± 4.6 |

94.4 ± 6.1 |

| RR |

Lgroup |

22.6 ± 6.4 |

21.3 ± 7.3 |

20.5 ± 6.7 |

20.3 ± 6.5 |

21.7 ± 4.9 |

| (brpm) |

CLgroup |

26.3 ± 1.4 |

22.6 ± 4.2 |

22.4 ± 3.3 |

23.8 ± 2.9 |

23.4 ± 3.3 |

| |

LDgroup |

24.9 ± 6.3 |

21.8 ± 5.8 |

21.1 ± 4.3 |

20.9 ± 5.7 |

21.8 ± 7.9 |

| t |

Lgroup |

38.5 ± 0.4 |

38.3 ± 0.4 |

38.2 ± 0.25 |

38.2 ± 0.3 |

37.9 ± 0.1 |

| (° C) |

CLgroup |

38.9 ± 0.2 |

38.5 ± 0.5 |

38.5 ± 0.4 |

38.3 ± 0.5 |

38.1 ± 0.5 |

| |

LDgroup |

37.6 ± 0.6 |

38 |

38 |

37.7 ± 0.5 |

37.6 ± 0.6 |

Table 4.

Time of recovery from the spinal block and ataxia score from standing. Mean ± standard deviation of times (minute) of recovery of anal sphincter tone (AS), the recovery of sensibility (RoS), the occurrence of the first spontaneous limb movements (FMov), the first attempts to stand (FAtt) and the time of standing (ToS) recorded from the spinal block. After the standing, animals were observed every 10 minutes for one hour (ATA10, ATA20, ATA30, ATA40, ATA50, ATA60) and the degree of ataxia (median and interquartile range) was measured using a numerical descriptive scale: 1=absent; 2=mild; 3=severe. (Lgroup: spinal lidocaine, CLgroup: spinal lidocaine+clonidine, LDgroup: spinal lidocaine+dexmedetomidine).

Table 4.

Time of recovery from the spinal block and ataxia score from standing. Mean ± standard deviation of times (minute) of recovery of anal sphincter tone (AS), the recovery of sensibility (RoS), the occurrence of the first spontaneous limb movements (FMov), the first attempts to stand (FAtt) and the time of standing (ToS) recorded from the spinal block. After the standing, animals were observed every 10 minutes for one hour (ATA10, ATA20, ATA30, ATA40, ATA50, ATA60) and the degree of ataxia (median and interquartile range) was measured using a numerical descriptive scale: 1=absent; 2=mild; 3=severe. (Lgroup: spinal lidocaine, CLgroup: spinal lidocaine+clonidine, LDgroup: spinal lidocaine+dexmedetomidine).

| |

L group |

CL group |

LD group |

p L vs CL |

p L vs LD |

p CL vs LD |

|

| AS (minute) |

82.2 ± 15.1 |

131 ± 28 |

88 ± 51.5 |

< 0.001 |

0.6 |

0.015 |

|

| RoS |

146 ± 21.8 |

207 ± 27.1 |

198 ± 60.4 |

< 0.001 |

< 0.008 |

0.6 |

|

| (minute) |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FMov |

84.8 ± 29 |

125 ± 14.6 |

185 ± 63 |

< 0.001 |

< 0.001 |

0.003 |

|

| (minute) |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FAtt |

96.8 ± 27.9 |

192 ± 44.2 |

210 ± 60.1 |

< 0.001 |

< 0.001 |

0.38 |

|

| (minute) |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ToS |

127 ± 25.2 |

220 ± 35.7 |

316 ± 80.3 |

< 0.001 |

< 0.001 |

< 0.001 |

|

| (minute) |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ATA10 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

0.68 |

0.5 |

0.7 |

|

| (score) |

(3-2) |

(3-2) |

(3-3) |

|

| |

|

|

|

| ATA20 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

< 0.001 |

0.07 |

0.002 |

|

| (score) |

(2-1) |

(3-2) |

(2-2) |

|

| |

|

|

|

| ATA30 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

< 0.001 |

0.004 |

0.19 |

|

| (score) |

(2-1) |

(3-2) |

(2-2) |

|

| |

|

|

|

| ATA40 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0.65 |

< 0.001 |

< 0.001 |

|

| (score) |

(1-1) |

(2-1) |

(2-2) |

|

| |

|

|

|

| ATA50 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.16 |

|

| (score) |

(1-1) |

(1-1) |

(1-1) |

|

| |

|

|

|

| ATA60 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.16 |

|

| (score) |

(1-1) |

(1-1) |

(1-1) |

|

| |

|

|

|

Table 5.

Time of the first rescue analgesia administration from the spinal block. Mean ± standard deviation of the time (minute) of the first rescue analgesia administration (1stR) from the spinal block. (Lgroup: spinal lidocaine, CLgroup: spinal lidocaine+clonidine, LDgroup: spinal lidocaine+dexmedetomidine.).

Table 5.

Time of the first rescue analgesia administration from the spinal block. Mean ± standard deviation of the time (minute) of the first rescue analgesia administration (1stR) from the spinal block. (Lgroup: spinal lidocaine, CLgroup: spinal lidocaine+clonidine, LDgroup: spinal lidocaine+dexmedetomidine.).

| |

1stR

(min) |

p L vs CL |

p L vs LD |

p LD vs CL |

| L group |

257.2 ± 65.7 |

< 0.001 |

< 0.001 |

- |

| CL group |

404.2 ± 47.7 |

< 0.001 |

- |

< 0.001 |

| LD group |

544.2 ± 84.2 |

- |

< 0.001 |

< 0.001 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).