Submitted:

08 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Rationale

Mechanisms of Action

Mechanisms of Moxibustion Efficacy

- Local Vasodilation and Enhanced Perfusion: The heat from moxibustion (typically 40–50°C at the skin surface) induces vasodilation of arterioles and microvessels, increasing blood flow to targeted tissues. This facilitates the delivery of oxygen and nutrients while removing metabolic waste and inflammatory byproducts, promoting tissue repair and reducing edema (Gao et al., 2025). In conditions like knee osteoarthritis (KOA), this mechanism enhances synovial fluid circulation, reducing cartilage degradation and stiffness (Chen et al., 2025).

- Autonomic Nervous System Modulation: Moxibustion activates cutaneous thermoreceptors, triggering reflex responses via the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems. This can lead to distal vasoconstriction (e.g., in fingertips) Vand overall autonomic balance, which alleviates pain and stiffness in chronic low back pain (CLBP) by improving microcirculation (Wang et al., 2025).

- Suppression of Inflammatory Cytokines: Moxibustion downregulates pro-inflammatory mediators such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). In rheumatoid arthritis (RA) models, this reduces synovial inflammation, hyperemia, and edema, contributing to analgesia and symptom improvement (Li et al., 2025). Similarly, in cancer-related fatigue, it modulates Th1/Th2 cytokine balance and reduces interferon-γ/IL-4 ratios, enhancing immune function (Zhang et al., 2023).

- Inhibition of Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis: By scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) and activating antioxidant pathways, moxibustion mitigates oxidative damage. It also suppresses apoptosis through cell cycle modulation (e.g., via p53 and Bcl-2 pathways), which is particularly relevant in neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer's disease (AD) prevention (Deng & Shen, 2013).

- Induction of Heat Shock Proteins (HSPs) and Neurotrophins: Heat stress from moxibustion upregulates HSPs (e.g., HSP70) and neurotrophic factors like brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and nerve growth factor (NGF). These promote neuronal survival, synaptic plasticity, and cognitive function, as seen in animal models of cognitive impairment where moxibustion prevented amyloid-beta (Aβ) accumulation and tau hyperphosphorylation (Wang et al., 2025).

- Vagus Nerve Activation and Central Pain Modulation: Moxibustion stimulates vagal afferents, reducing central sensitization in neuropathic pain (e.g., postherpetic neuralgia). Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) studies show altered activation in pain-related cortical regions, such as the anterior cingulate cortex, supporting its role in chronic non-specific low back pain (CNLBP) (Wang et al., 2025).

- Beyond heat, volatile compounds in mugwort (e.g., α-thujone, camphor) provide anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects via transdermal absorption. These act synergistically with thermal stimulation to regulate growth factors like insulin-like growth factor (IGF) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), strengthening joint integrity in KOA (Chen et al., 2025).

- In TCM terms, moxibustion "warms the meridians, dispels cold and dampness," aligning with Western views of improved immunity and reduced nerve compression (Deng & Shen, 2013).

Comparison of Mechanisms: Moxibustion vs. Acupuncture

- Peripheral Sensitization and Local Effects: Needle insertion activates mechanosensitive Aδ and Aβ fibers at acupoints, triggering adenosine triphosphate (ATP) release and transient receptor potential vanilloid (TRPV) channels, which enhance local blood flow and reduce inflammation. This inhibits cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production, alleviating peripheral pain and edema (Lin et al., 2020). In allergic rhinitis models, it downregulates eosinophils (EOS) and interleukin-5 (IL-5), suppressing immune signaling (Wang et al., 2024).

- Central Nervous System (CNS) Modulation: Signals ascend via the spinal dorsal horn to the brainstem and thalamus, releasing endogenous opioids (e.g., β-endorphins), serotonin, norepinephrine, orexin, and endocannabinoids. This inhibits pain transmission in the periaqueductal gray (PAG) and modulates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis for stress-related analgesia (Lin et al., 2020).

- Neuroplasticity and Long-Term Effects: Electroacupuncture (EA) reverses maladaptive plasticity in chronic pain by modulating basal ganglia and limbic circuits, enhancing brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression for motor recovery in Parkinson's disease (PD) (Wang et al., 2024).

- Immune and Systemic Regulation: It balances Th1/Th2 cytokines (e.g., upregulates IFN-γ, downregulates IL-4/IgE) and microbiota via vagal pathways, aiding conditions like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (Wang et al., 2024).

- Thermal and Circulatory: Promotes perfusion and waste clearance via arteriolar dilation; activates HSP70 for cytoprotection (Deng & Shen, 2013).

- Anti-Inflammatory: Downregulates TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6; modulates Th1/Th2 balance more potently in fatigue (Zhang et al., 2023).

- Neuroprotective: Enhances BDNF/NGF via default mode network (DMN) regulation; vagal activation for emotional comfort (Wang et al., 2025).

- Metabolic: Influences amino acid pathways in IBD, broader than acupuncture (Wang et al., 2024).

Methods

Eligibility Criteria

- Population: Adults (>18 years) in rehabilitation for musculoskeletal/neurological pain (e.g., post-stroke, RA, TKA, MPS).

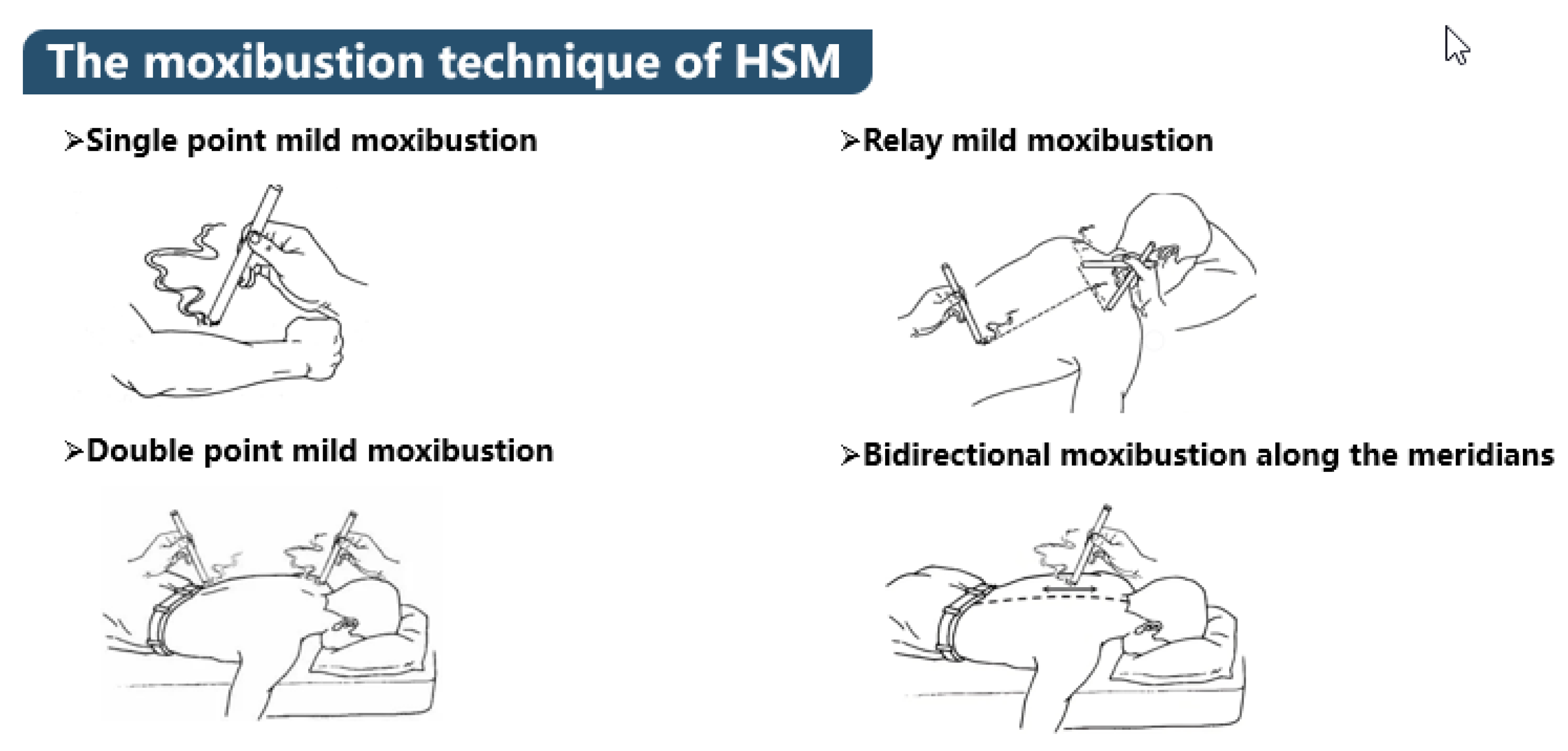

- Interventions: Moxibustion (heat moxibustion, needle-warming, electric moxa) alone or adjunctive to PT.

- Comparators: Conventional PT (e.g., quadriceps training, mobilization, rehabilitation nursing) or PT + sham/placebo.

-

Outcomes:

- ◦

- Primary: Pain (VAS/NPRS), functional mobility (FMA, BI).

- ◦

- Secondary: Quality of life (SF-36), adverse events, muscle strength.

- Study Designs: RCTs, controlled trials, systematic reviews/meta-analyses (if primary data extractable).

- Exclusions: Non-human studies, non-English abstracts, case reports without comparators.

Information Sources

Search Strategy

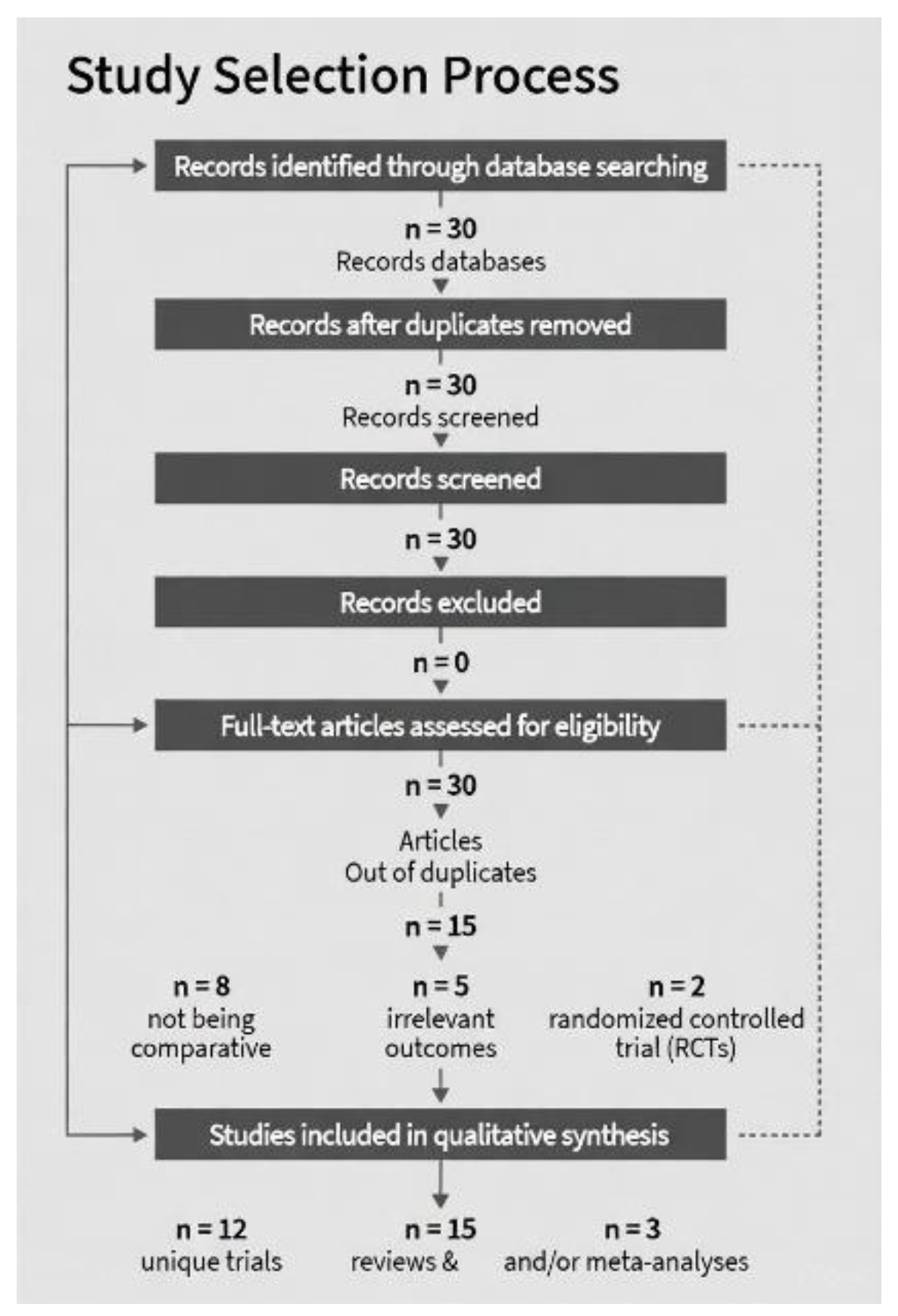

Selection Process

Data Collection Process

Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

Synthesis Methods

Results

Study Characteristics

Risk of Bias

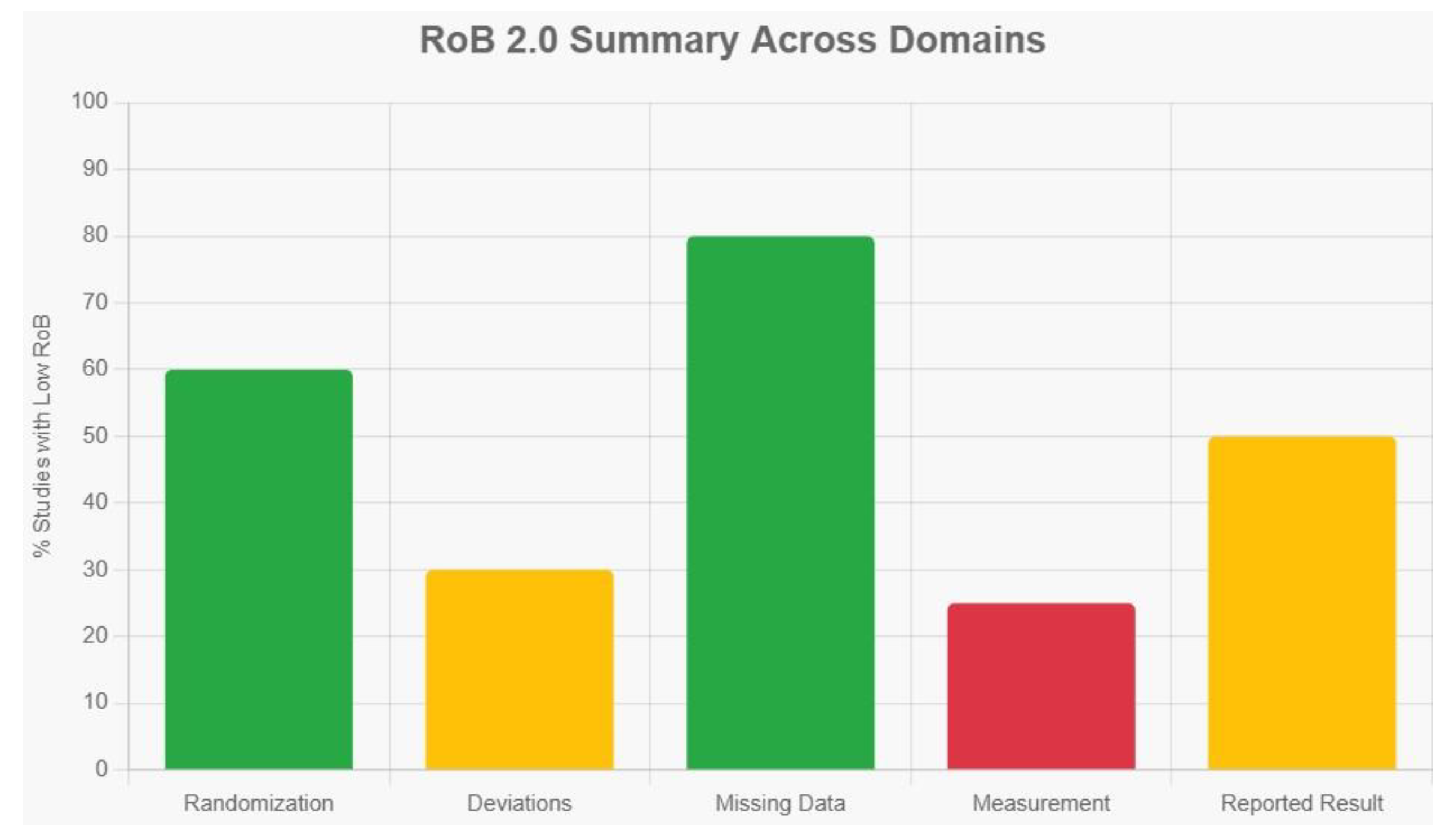

- Low: 6/15 (adequate randomization, blinding).

- Moderate: 7/15 (single-center, no blinding; heterogeneity in meta [Gao et al., 2025]).

- High: 2/15 (retrospective [Jeong et al., 2018]; small n [McLeod, 2007; Lee et al., 2011]). Common issues: Performance bias (non-blinded moxa); attrition <10% (Figure 3).

Results of Individual Studies

Results of Synthesis

- Pain: Moxa + PT > PT (VAS reductions: 1.5–3.0; consistent across conditions).

- Function: Enhanced mobility/recovery (e.g., post-TKA SLR time ↓24h; post-stroke FMA ↑15%).

- QoL: SF-36/BI improvements in RA/post-stroke (↑15–20%).

- Safety: Adverse events low (burns 1–2%; no serious in RCTs). Heterogeneity: High (protocols vary; I²=80% in meta [Gao et al., 2025]).

Discussion

Summary of Evidence

Clinical Integration and Implications

Limitations

- Evidence Quality: High heterogeneity (I² >75%) across moxibustion modalities (e.g., indirect vs. electronic) and PT comparators (e.g., TDP irradiation vs. mobilization) precluded formal meta-analysis, limiting pooled effect size estimates and subgroup analyses. Many included RCTs were single-center with moderate overall risk of bias, as assessed via the simplified RoB 2.0 tool, which evaluates domains including randomization process, deviations from interventions, missing data, outcome measurement, and selective reporting (Sterne et al., 2019). Specifically, low risk was common in randomization (e.g., via random number tables in ~60% of studies) and attrition bias (<10% dropout rates), reflecting adequate allocation and data completeness (Gao et al., 2025; Chen et al., 2025).

- Scope: Reliance on a curated corpus introduces potential publication bias toward positive Asian studies, as the majority of TCM RCTs (e.g., 96.64% in some topics) are published exclusively in Chinese-language journals and databases like CNKI, often inaccessible without bilingual expertise, leading to selection bias in English-only searches (Wu et al., 2013). This language bias is compounded by geographic skew, with over 40% of acupuncture/moxibustion trials originating from China and the Western Pacific region, creating an uneven global distribution that underrepresents Western, African, and Southeast Asian contexts (Lai et al., 2025). Consequently, these biases inflate effect sizes in included studies—Chinese-language trials show larger treatment effects (pooled ROR 0.51, 95% CI 0.29–0.91) and higher risks of bias in blinding (97% vs. 51% in non-Chinese trials)—compromising the review's internal validity and long-term data (>12 weeks) remain sparse, limiting insights into sustained effects.

- Generalizability: Predominantly Asian cohorts (e.g., 84 RCTs in shoulder meta-analysis) may not fully translate to diverse populations, as regional differences in clinical practices, patient demographics, and cultural TCM interpretations hinder cross-cultural applicability; few direct head-to-head comparisons exist, with most evidence adjunctive, further exacerbating the risk of overestimating benefits in non-Asian settings (Zhang et al., 2025; Li et al., 2023).

- Comparators: Variability in "conventional PT" (e.g., TDP irradiation vs. mobilization) dilutes precision, and adverse event reporting is inconsistent across reviews.

Future Directions

Conclusions

References

- Chen, R.; Kang, M.; He, W.; Huang, G.; Fang, M. Moxibustion on heat-sensitive acupoints for treatment of myofascial pain syndrome: A multi-central randomized controlled trial. Chinese Acupuncture & Moxibustion 2008, 28(6), 401–404. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Han, W.; Sun, S. Impacts of the combined treatment of Tongdu Tiaoshen moxibustion and rehabilitation training on the motor function recovery of the upper limbs in the patients with apoplectic hemiplegia. World Journal of Acupuncture-Moxibustion 2020, 30(2), 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; et al. Efficacy and safety of moxibustion for knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice 58 2025, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, H.; Shen, X. The mechanism of moxibustion: Ancient theory and modern research. In Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2013; 2013; p. 379291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freiwald, J.; Magni, A.; Fanlo-Mazas, P.; Rodemund, S.; Steinmetz, P. A role for superficial heat therapy in the management of non-specific, mild-to-moderate low back pain in current clinical practice: A narrative review. Life 2021, 11(8), 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Li, Z.; Chen, W.; Shen, F.; Lü, Y. Effectiveness of acupuncture and moxibustion combined with rehabilitation training for post-stroke shoulder-hand syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Neurology 16 2025, 1576595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, X.; Wu, L.; Wang, M.; Xue, D.; Tian, F. The effect of electronic moxibustion combined with rehabilitation nursing on the lumbar pain and stiffness of ankylosing spondylitis patients. American Journal of Translational Research 2021, 13(5), 5452–5459. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, H. G.; et al. Effect of Korean medicine combined with electric moxibustion in patients with traffic accident-induced lumbago. Journal of Acupuncture Research 2018, 35(4), 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, C.-J.; Zhou, X.; Dong, C.-C.; Lin, L.-Q.; Liu, H.-N.; Hou, Y. Clinical observation of warm moxibustion therapy to improve quadriceps weakness after total knee arthroplasty. Chinese Acupuncture & Moxibustion 2019, 39(3), 276–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-W.; Kim, J.; Lee, N.; Choi, W.-H. Evaluation of the muscle fatigue recovery effect by indirect moxibustion treatment. Journal of Acupuncture and Meridian Studies 2011, 4(1), 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; et al. Comparing moxibustion strategies in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medical Sciences 2025, 12(1), 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; et al. Comparison of the effects of 10.6-μm infrared laser and traditional moxibustion in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Lasers in Medical Science 2020, 35(4), 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGorm, H.; et al. Turning up the heat: An evaluation of the evidence for heating to promote exercise recovery, muscle rehabilitation and adaptation. Sports Medicine 2018, 48(6), 1311–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeod, P. A. Treatment of a grade two sprain of the anterior talofibular ligament with acupuncture and moxibustion. Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association 2007, 51(1), 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J.; McKenzie, J. E.; Bossuyt, P. M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T. C.; Mulrow, C. D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J. M.; Akl, E. A.; Brennan, S. E.; Chou, R.; Glanville, J.; Grimshaw, J. M.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Lalu, M. M.; Li, T.; Loder, E. W.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; McDonald, S.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372 2021, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qahtani, T.; Ladnah, L. M.; Alamri, S.; et al. Evaluating the impact of moxibustion on pain management in rheumatoid arthritis patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Medicine in Developing Countries 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J. A. C.; Savović, J.; Page, M. J.; Elbers, R. G.; Blencowe, N. S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C. J.; Cartes, A. G.; Coburn, M.; Elliot, J.; Gamble, C.; Gates, S.; Graziotto, P.; Harhay, M. O.; Jüni, P.; Kahlert, Y.; Krommes, T.; Lasch, K. E.; Li, T.; Higgins, J. P. T. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 366 2019, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; et al. Effect of traditional moxibustion in assisting the rehabilitation of stroke patients. Clinical Trials and Clinical Research 2023, 2(5). [Google Scholar]

- Ventriglia, G.; Franco, M.; Magni, A.; et al. Treatment algorithms for continuous low-level heat wrap therapy for the management of musculoskeletal pain: An Italian position paper. Journal of Pain Research 17 2024, 452661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; et al. Acupuncture and moxibustion for inflammatory bowel disease: A metabolomics study. American Journal of Chinese Medicine 2024, 52(7), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; et al. Effectiveness and mechanism of moxibustion in treating chronic non-specific low back pain: Protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Medicine 12 2025, 1664326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Huang, M.; Zeng, L.; Huang, Z.; Zheng, J. Needle-warming moxibustion plus multirehabilitation training to improve quality of life and functional mobility of patients with rheumatoid arthritis after medication. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2022 2022, 5833280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Kang, M.; Xiong, P. Clinical randomized controlled trials of treatment of neck-back myofascial pain syndrome by acupuncture of Ashi-points combined with moxibustion of heat-sensitive points. Acupuncture Research 2011, 36(2), 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin-hu, H. Effect of moxibustion plus rehabilitation on post-stroke lower-limb spasticity. Shanghai Journal of Acupuncture and Moxibustion 2014, 33(1), 105–107. [Google Scholar]

- Zanoli, G.; Albarova-Corral, I.; Ancona, M.; et al. Current indications and future direction in heat therapy for musculoskeletal pain: A narrative review. Muscles 2024, 3(3), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of moxibustion for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Medicine 2023, 102(50), e36412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. Comparative effectiveness of acupuncture-related therapies for shoulder pain: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Frontiers in Medicine 12 2025, 1673193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; et al. The effects of integrated traditional Chinese and western medicine on stroke rehabilitation: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2025, 20(1), e0318535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aspect | Acupuncture | Moxibustion | Clinical Implications |

| Stimulation Type | Mechanical/electrical (Aβ/Aδ fibers); quick, precise onset (Lin et al., 2020). | Thermal (C fibers); gradual, warming penetration (Gao et al., 2025). | Acupuncture for acute pain/visceral hypersensitivity (e.g., IBS); moxibustion for chronic cold/damp conditions (e.g., fatigue, arthritis) (Wang et al., 2024). |

| Autonomic Effects | Stronger vagal activation (parasympathetic dominance, HR reduction) (Lin et al., 2020). | Sympathetic modulation + vagal; promotes relaxation via DMN (Wang et al., 2025). | Acupuncture better for anxiety/depression; moxibustion for fatigue/stress urinary incontinence (SUI) (Zhang et al., 2023). |

| CNS Networks | Homeostatic afferent processing (thalamus-limbic); reverses plasticity (Lin et al., 2020). | DMN regulation (internal monitoring); emotional comfort (Wang et al., 2025). | Acupuncture for motor/neurological recovery (e.g., PD); moxibustion for cognitive/emotional balance (Wang et al., 2024). |

| Inflammatory/Immune | Cytokine balance via HPA; targeted (e.g., IL-5 in AR) (Wang et al., 2024). | Broader metabolic pathways (e.g., amino acids in IBD); HSP induction (Wang et al., 2024). | Combined for IBD/RA; moxibustion superior in metabolic disorders (Chen et al., 2025). |

| Efficacy Duration | Rapid but shorter-term (e.g., VAS drop in sessions) (Lin et al., 2020). | Sustained warming (e.g., better long-term in KOA) (Chen et al., 2025). | Moxibustion edges in chronic pain (e.g., fire-needle variant SMD -0.56 vs. acupuncture) (Chen et al., 2025). |

| Study | Condition | Design (n) | Intervention | Comparator | Key Outcomes |

| Chen et al. (2008) | MPS | RCT (120) | Heat moxa on acupoints | Acupuncture/PT | Cure rate 86% vs. 60%; VAS ↓2.5 (p<0.01) |

| Ju et al. (2019) | TKA | RCT (60) | Warm moxa + quad training | PT alone | Strength ↑15% (p<0.05); VAS ↓1.8; earlier SLR (12h) |

| Gao et al. (2025) | Post-stroke SHS | Meta (27 RCTs, ~1,000) | Moxa + rehab | Rehab alone | FMA ↑12% (p<0.001); VAS ↓2.0; BI ↑10% |

| Wu et al. (2022) | RA | RCT (80) | Needle-warm moxa + multi-rehab | Medication/PT | FMA ↑18%; SF-36 ↑20% (p<0.01); anxiety ↓ |

| Chen et al. (2020) | Post-stroke hemiplegia | RCT (50) | Tongdu moxa + rehab | Rehab alone | FMA ↑15% at 8w (p<0.05); ARAT ↑12% |

| Wu et al. (2011) | Neck-back MPS | RCT (90) | Heat moxa + Ashi acupuncture | Acupuncture + TDP | Pain ↓3.0 VAS (p<0.01) vs. 1.5 |

| Huan et al. (2021) | Ankylosing spondylitis | RCT (60) | Electric moxa + nursing | Nursing/PT alone | VAS ↓2.2; mobility ↑25% (p<0.05) |

| Jeong et al. (2018) | Traffic-accident lumbago | Retrospective (120) | Electric moxa + Korean med/PT | PT alone | Pain ↓ faster (p<0.05); QoL ↑15% |

| Qahtani et al. (2025) | RA | Meta (10 studies) | Moxa | PT/medication | Pain intensity ↓1.5; DAS28 ↓0.8 (p<0.05) |

| Ventriglia et al. (2024) | Musculoskeletal pain | Position paper (review) | Heat wrap/moxa + PT | PT alone | Stiffness ↓; strength ↑ (narrative) |

| Zanoli et al. (2024) | Knee/sports pain | Narrative review | Superficial heat/moxa | PT | Circulation ↑; pain relief (mechanism-focused) |

| Freiwald et al. (2021) | Low back pain | Narrative review | Heat therapy/moxa | PT | Function ↑ (mild-moderate evidence) |

| McLeod (2007) | Ankle sprain | Case series (1) | Heat moxa + rehab | PT | Recovery in 2 weeks (descriptive) |

| Lee et al. (2011) | Muscle fatigue | RCT (20) | Indirect moxa | No stim/PT | Torque recovery ↑20% (p<0.05) |

| Xin-hu (2014) | Post-stroke spasticity | RCT (60) | Moxa + rehab | Rehab alone | CSI ↓; FMA ↑10% (p<0.01) |

| Outcome | Studies (n) | VAS Reductions (per Study) | Certainty of Evidence (GRADE) | Justification |

| Pain Reduction | 12 RCTs | Chen et al. (2008): ↓2.5 Ju et al. (2019): ↓1.8 Gao et al. (2025): ↓2.0 Wu et al. (2011): ↓3.0 Huan et al. (2021): ↓2.2 Qahtani et al. (n.d.): ↓1.5 (Aggregated MD -1.8; 95% CI -2.5 to -1.0) | Moderate | Downgraded for inconsistency (I²=75%); no serious imprecision or indirectness; low publication bias risk. |

| Functional Mobility (FMA) | 13 RCTs | N/A (FMA-focused; e.g., Gao et al. (2025): ↑12; Wu et al. (2022): ↑18) | Low | Downgraded for inconsistency (I²>80%) and risk of bias (blinding issues); upgraded for large effect size. |

| QoL (SF-36/BI) | 8 RCTs | N/A (QoL-focused; e.g., Wu et al. (2022): ↑20; Jeong et al. (2018): ↑15) | Moderate | Downgraded for risk of bias (subjective measures); no serious inconsistency. |

| Adverse Events | 15 RCTs | N/A (Low incidence; e.g., burns <2% across trials) | High | No downgrades; precise, consistent, low bias. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).