Submitted:

08 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fingerprint-Based Machine Learning Models

2.2. Graph Neural Network

- L represents the base loss function (MSE in the current implementation);

- σ2 denotes the predicted variance;

- λ ∈ [0,1] is a hyperparameter that balances the standard prediction loss and the uncertainty calibration term (λ = 1 in the current implementation);

- denotes the expectation over the training samples.

2.3. Performance Metrics

- is the number of observations;

- represents the observed value for the i-th sample;

- represents the predicted value for the i-th sample;

- is the mean of the observed values: .

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Dataset Preparation

3.1.1. General

- Chemical structure canonicalization. SMILES were canonicalized using the canonicalize method of MoleculeContainer from Chython library. Separately canonicalization using “canonicalize” and “clean_stereo” methods was performed for inspecting different stereoisomers. Generally, stereoisomers from a single source were kept, while stereoisomers from different sources were considered unreliable and data points from a single source were kept while others were dropped.

- Identifying and resolving of structure – temperature – log CMC duplicates. For entries with identical surfactant structures and log CMC values but differing measurement temperatures, temperature values were averaged if the difference was ≤ 2 °C; otherwise, the entries were excluded to avoid ambiguity. Conversely, for entries with the same surfactant structure and measurement temperature but differing log CMC values, the log CMC values were averaged if the range (Δlog CMC) between the maximum and minimum values was ≤ 0.3; entries exceeding this threshold were removed to ensure data consistency and reliability. Finally, exact duplicates – defined as identical SMILES, temperature and log CMC values – were removed to prevent overrepresentation in the dataset.

- Verification of data accuracy through original source. For duplicate entries – defined as identical SMILES and temperature values – present across multiple datasets with conflicting log CMC values, the original cited sources were consulted to verify and select the most accurate and consistent values, ensuring fidelity to the primary experimental data.

- Manual inspection of molecular structures. A final visual audit of all structures was conducted to detect anomalies; any suspicious entries were verified and corrected by consulting the original source literature. Unresolved cases were excluded to ensure structural accuracy and dataset integrity.

3.1.2. Temperature

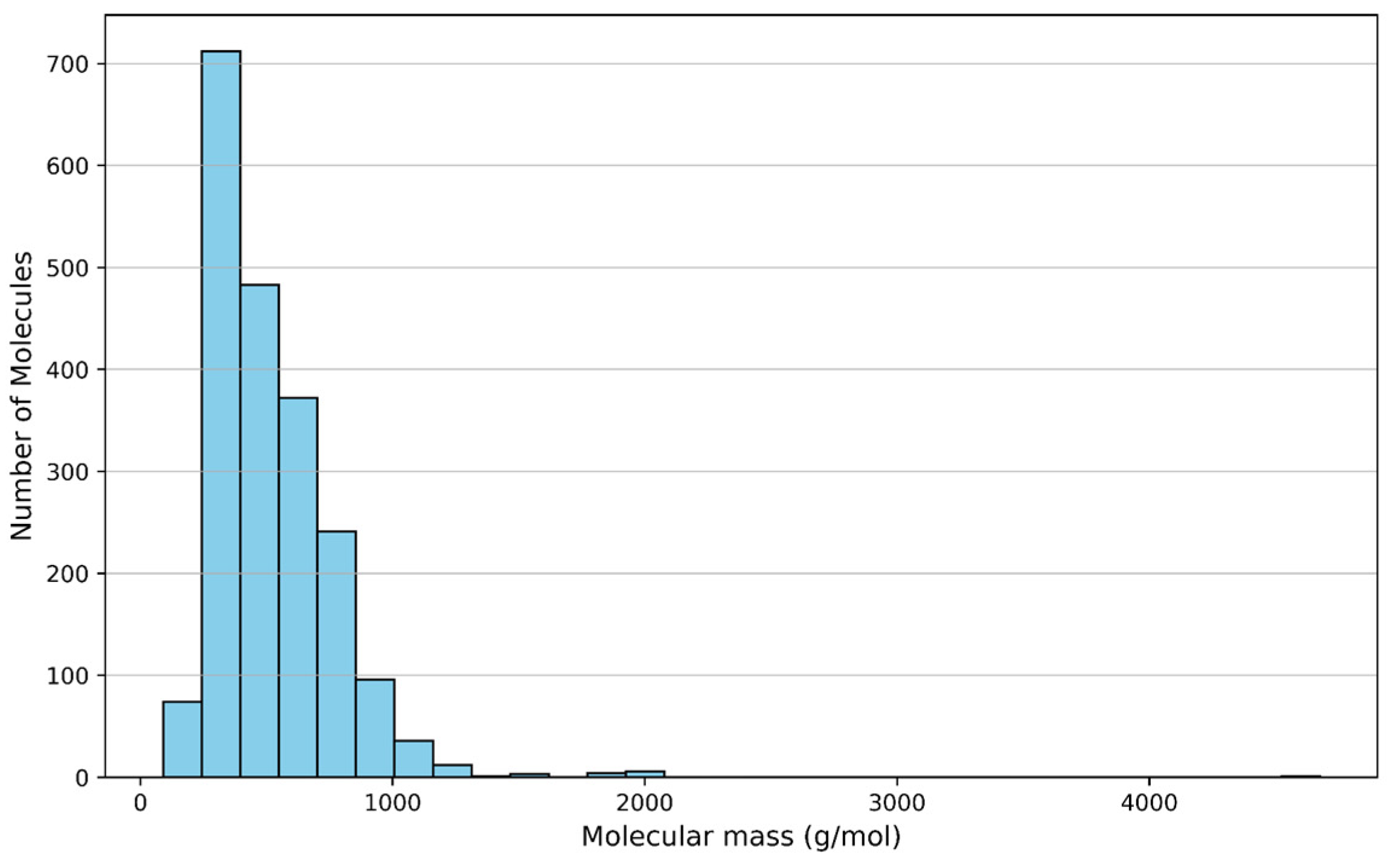

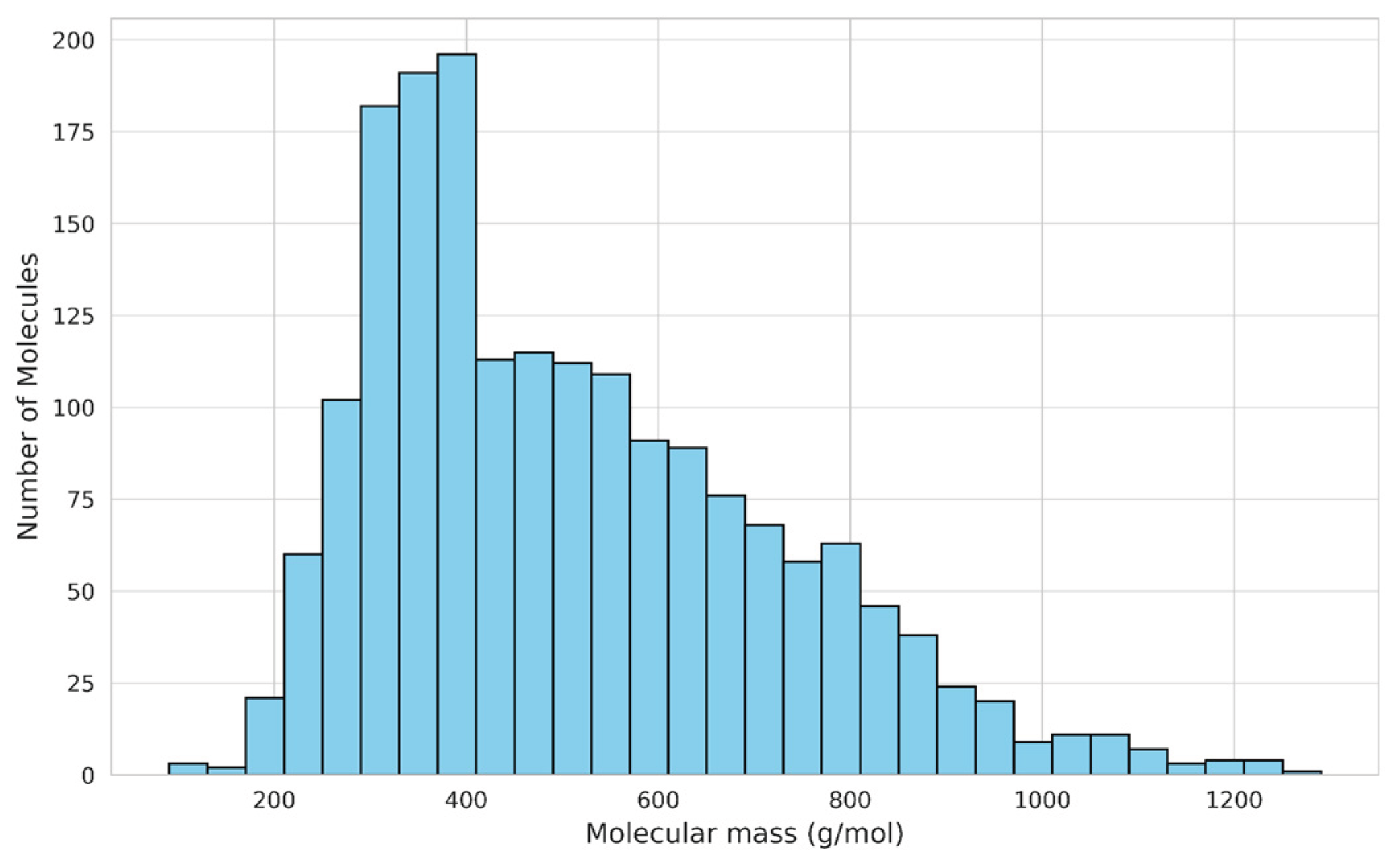

3.1.3. Molecular Mass

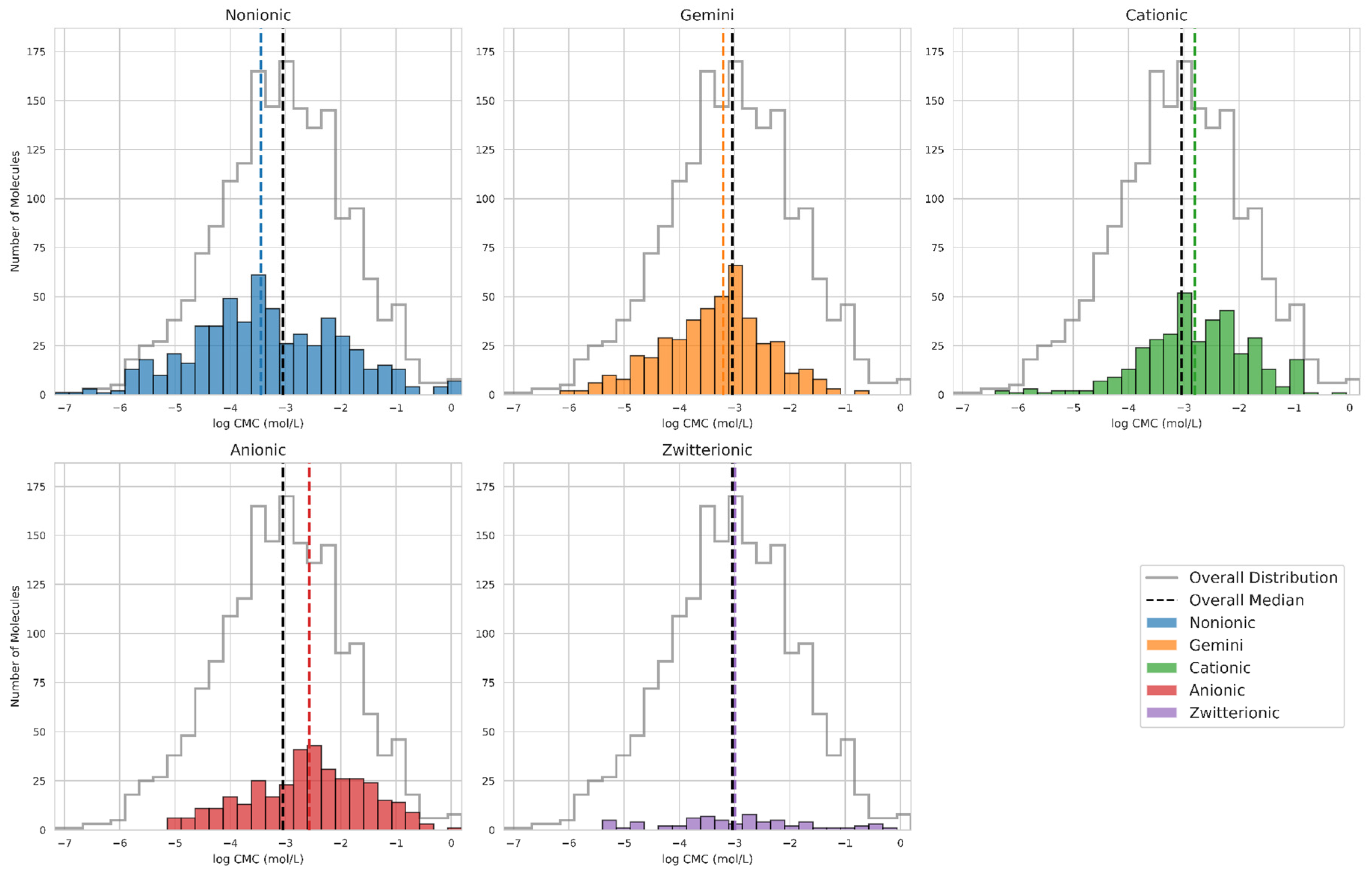

3.1.4. Surfactants Type

3.2. Training and Test Sets Preparation

3.3. Modeling

3.3.1. Fingerprint-Based Machine Learning Models

- max_features features fractional (0.1-0.5) and heuristic ("sqrt", "log2");

- max_depth explicitly included None (unconstrained trees) and values between 10 and 50 to evaluate depth necessity;

- min_samples_split (2-20);

- min_samples_leaf (1-15);

- n_estimators used log-scale sampling (100-1000);

- bootstrap parameters (max_samples, 0.5-1.0) were conditionally optimized only with enabled bootstrap.

- max_depth was restricted to values between 3 and 10 to model chemical relationships without overfitting;

- colsample_bytree (0.3-0.7) and subsample (0.6-0.95) mitigated feature redundancy;

- reg_alpha and reg_lambda were explored over 10-8 to 10.0 with log-uniform sampling, ensuring robust exploration of orders-of-magnitude effects;

- tree_method "hist" ensured computational efficiency for large feature spaces.

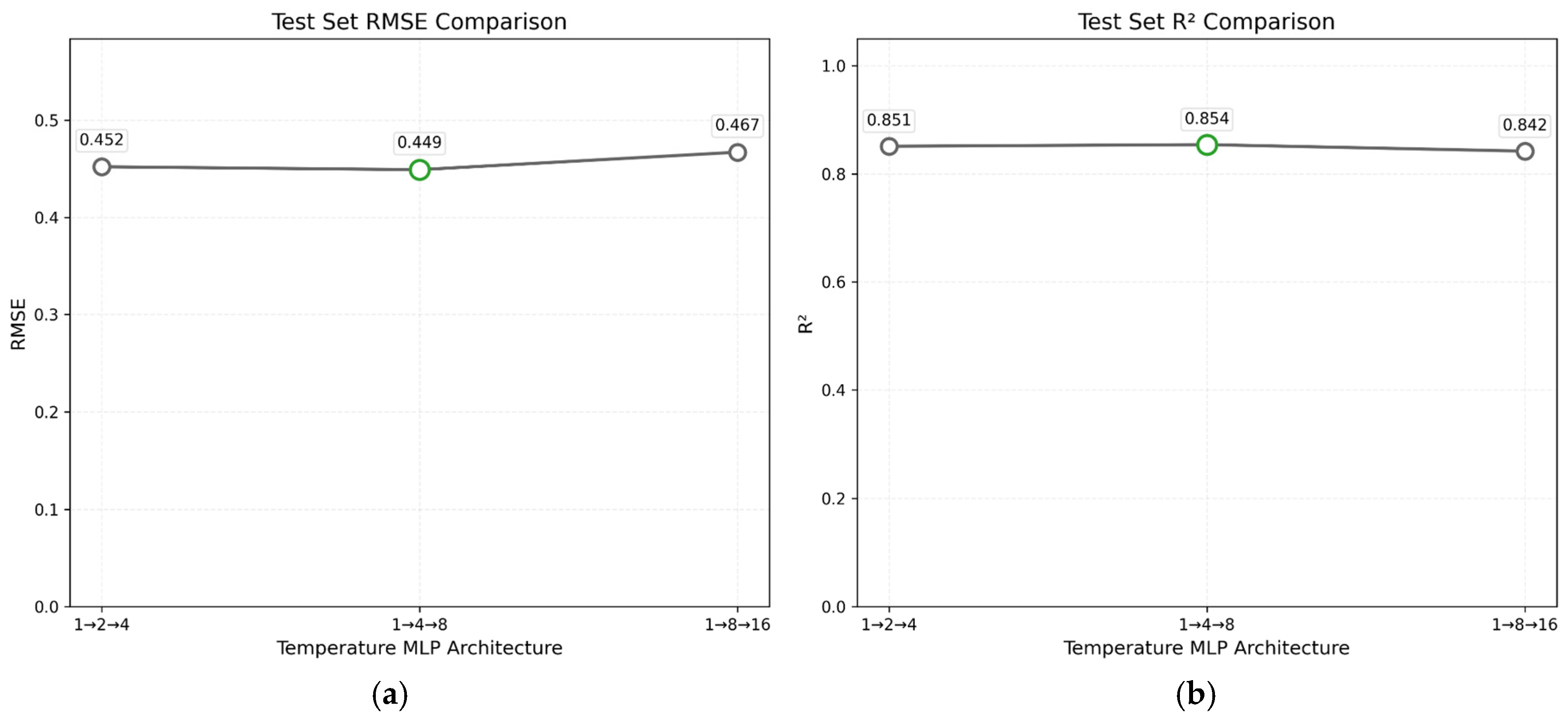

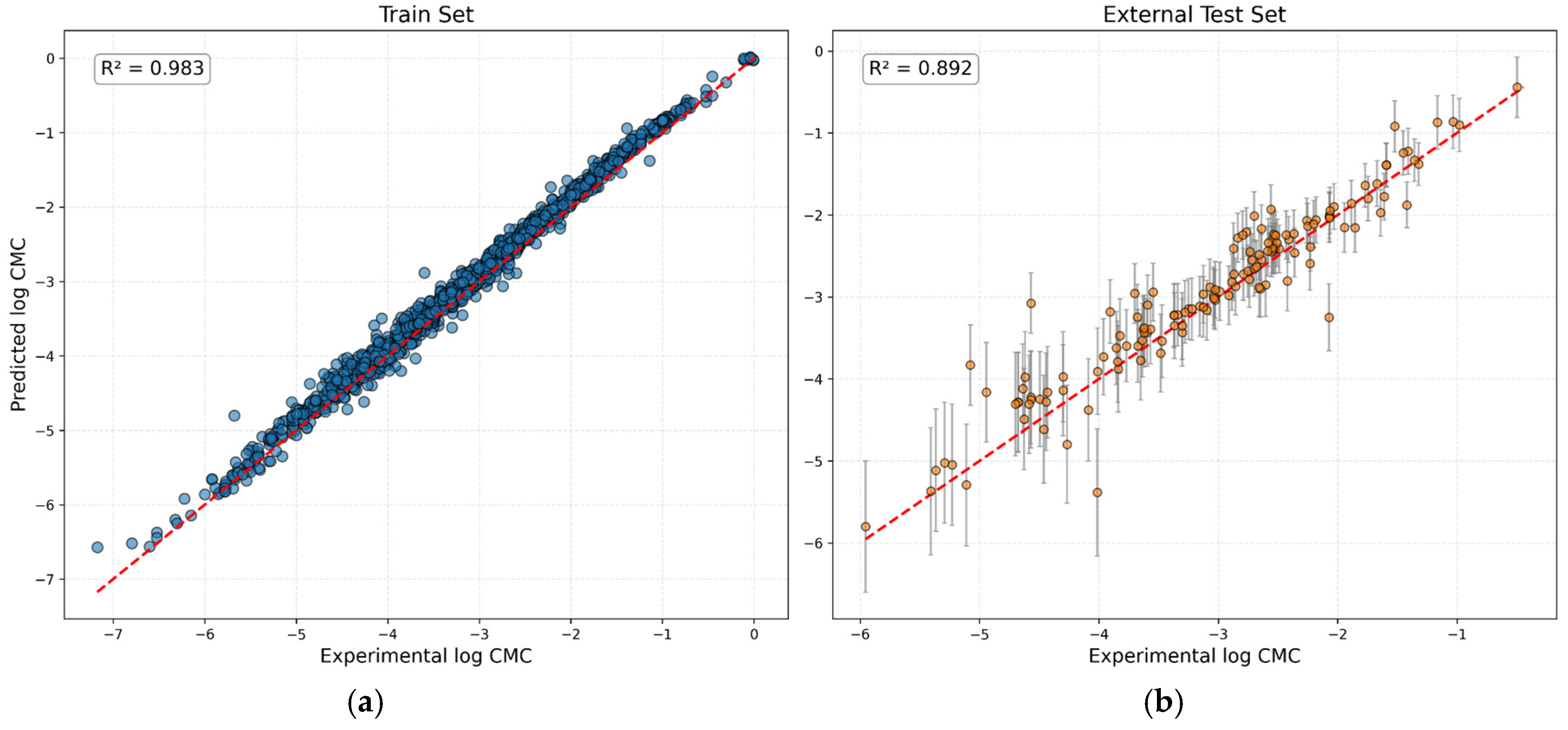

3.3.2. Graph Neural Network

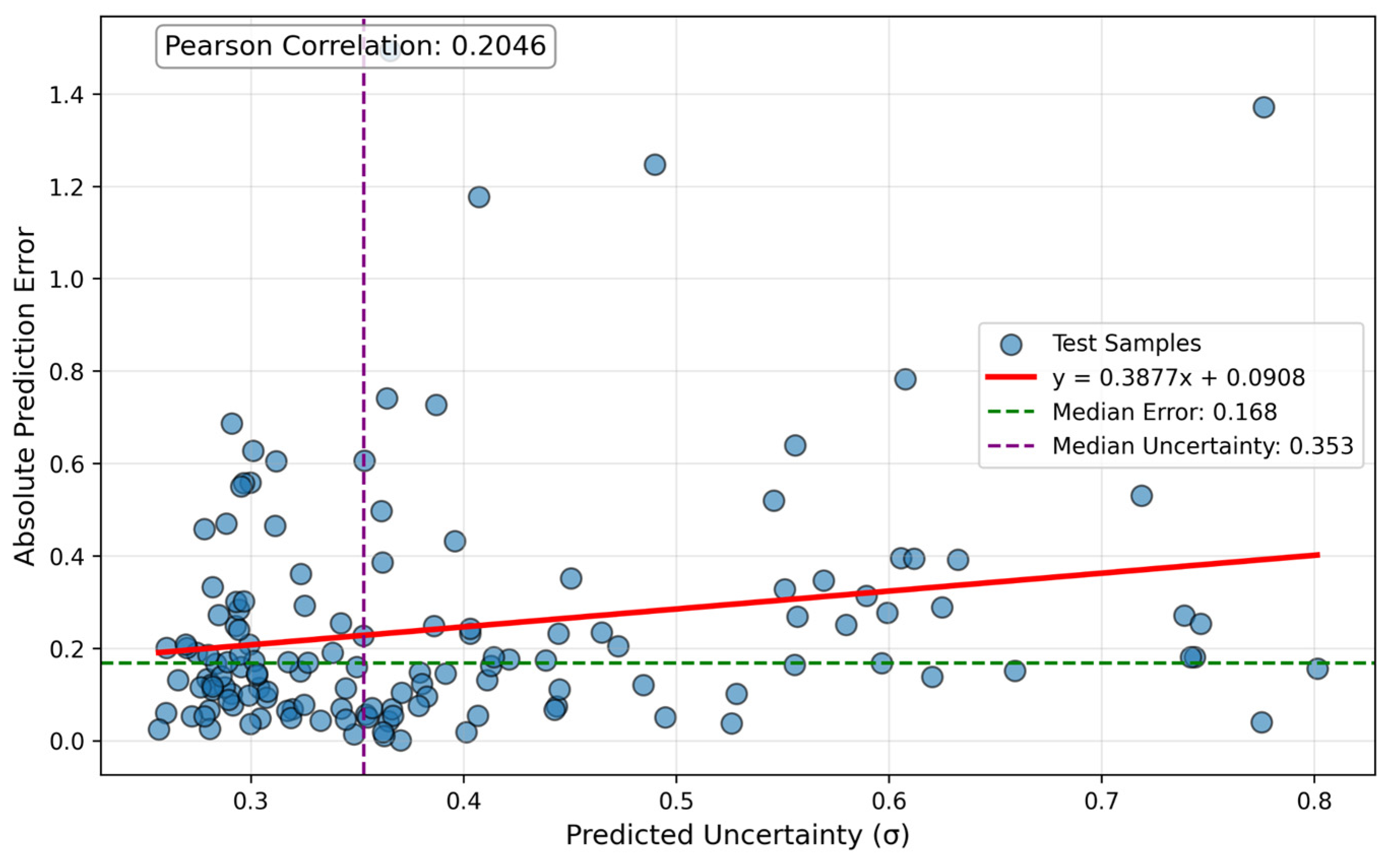

4. GNN Model Uncertainty Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CMC | Critical micelle concentration |

| GNN | Graph neural network |

| RMSE | Root mean squared error |

| MSE | Mean squared error |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

| MD | Molecular dynamics |

| QSPR | Quantitative structure-property relationship |

| COSMO-RS | Conductor-like screening model for realistic solvation |

| ML | Machine learning |

| MLR | Multiple linear regression |

| PLS | Partial least squares |

| ANN | Artificial neural network |

| SVR | Support vector regression |

| GNN/GP | GNN model augmented with Gaussian processes |

| FP | (Molecular) Fingerprint |

| RF | Random forest regressor |

| XGB | XGBoost regressor |

| MLP | Multilayer perceptron |

| SMILES | Simplified molecular input line entry system |

| CV | Cross-validation |

References

- Turchi, M.; Karcz, A.P.; Andersson, M.P. First-Principles Prediction of Critical Micellar Concentrations for Ionic and Nonionic Surfactants. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2022, 606, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas, H.; Kamrul-Bahrin, M.A.H.; Seddon, D.; Othman, J.; Cabral, J.T.; Mejía, A.; Shahruddin, S.; Matar, O.K.; Müller, E.A. Determining Interfacial Tension and Critical Micelle Concentrations of Surfactants from Atomistic Molecular Simulations. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2024, 674, 1071–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattei, M.; Kontogeorgis, G.M.; Gani, R. Modeling of the Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) of Nonionic Surfactants with an Extended Group-Contribution Method. [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Lu, J.R.; Thomas, R.K.; Tucker, I.M.; Webster, J.R.P.; Campana, M. Markov Chain Modeling of Surfactant Critical Micelle Concentration and Surface Composition. Langmuir 2019, 35, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Lengeling, B.; Aspuru-Guzik, A. Inverse Molecular Design Using Machine Learning: Generative Models for Matter Engineering. Science 2018, 361, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonina, V.A.; Mazitov, D.A.; Nurmukhametova, A.; Shevelev, M.D.; Khasanova, D.A.; Nugmanov, R.I.; Burilov, V.A.; Madzhidov, T.I.; Varnek, A. Prediction of Optimal Conditions of Hydrogenation Reaction Using the Likelihood Ranking Approach. IJMS 2021, 23, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrijawi, M.T.; Alhajj, R. LSTM-Driven Drug Design Using SELFIES for Target-Focused de Novo Generation of HIV-1 Protease Inhibitor Candidates for AIDS Treatment. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bushuev, K.R.; Lobanov, I.S. Machine Learning Method for Computation of Optimal Transitions in Magnetic Nanosystems. [CrossRef]

- Huibers, P.D.T.; Lobanov, V.S.; Katritzky, A.R.; Shah, D.O.; Karelson, M. Prediction of Critical Micelle Concentration Using a Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship Approach. In Nonionic Surfactants; Volume 1.

- Huibers, P.D.T.; Lobanov, V.S.; Katritzky, A.R.; Shah, D.O.; Karelson, M. Prediction of Critical Micelle Concentration Using a Quantitative Structure–Property Relationship Approach. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 1997, 187, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, G.; Dong, J.; Zhou, X.; Yan, X.; Luo, M. Estimation of Critical Micelle Concentration of Anionic Surfactants with QSPR Approach. Journal of Molecular Structure: THEOCHEM 2004, 710, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Huang, D.; Gong, S.; Li, G. Prediction on Critical Micelle Concentration of Nonionic Surfactants in Aqueous Solution: Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship Approach. Chin. J. Chem. 2003, 21, 1573–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katritzky, A.R.; Pacureanu, L.; Dobchev, D.; Karelson, M. QSPR Study of Critical Micelle Concentration of Anionic Surfactants Using Computational Molecular Descriptors. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2007, 47, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Wang, Y.; Qu, L.; Xue, Z.; Ge, Y.; Liu, H.; Lei, B.; Gao, Q.; Li, M. Hologram QSAR Study on the Critical Micelle Concentration of Gemini Surfactants. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2020, 586, 124226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creton, B.; Barraud, E.; Nieto-Draghi, C. Prediction of Critical Micelle Concentration for Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances. SAR and QSAR in Environmental Research 2024, 35, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anoune, N.; Nouiri, M.; Berrah, Y.; Gauvrit, J.; Lanteri, P. Critical Micelle Concentrations of Different Classes of Surfactants: A Quantitative Structure Property Relationship Study. J Surfact & Detergents 2002, 5, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahal, S.; Hadidi, N.; Hamadache, M. In Silico Prediction of Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) of Classic and Extended Anionic Surfactants from Their Molecular Structural Descriptors. Arab J Sci Eng 2020, 45, 7445–7454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidi, M.; Abdallah, E.; Si-Moussa, C.; Benkortebi, O.; Hentabli, M.; Hanini, S. CMC of Diverse Gemini Surfactants Modelling Using a Hybrid Approach Combining SVR-DA. CI&CEQ 2021, 27, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria-Lopez, A.; García-Martí, M.; Barreiro, E.; Mejuto, J.C. Ionic Surfactants Critical Micelle Concentration Prediction in Water/Organic Solvent Mixtures by Artificial Neural Network. Tenside Surfactants Detergents 2024, 61, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukelkal, N.; Rahal, S.; Rebhi, R.; Hamadache, M. QSPR for the Prediction of Critical Micelle Concentration of Different Classes of Surfactants Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Journal of Molecular Graphics and Modelling 2024, 129, 108757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, S.; Jin, T.; Lehn, R.C.V.; Zavala, V.M. Predicting Critical Micelle Concentrations for Surfactants Using Graph Convolutional Neural Networks. [CrossRef]

- Moriarty, A.; Kobayashi, T.; Salvalaglio, M.; Striolo, A.; McRobbie, I. Analyzing the Accuracy of Critical Micelle Concentration Predictions Using Deep Learning. [CrossRef]

- Theis Marchan, G.; Balogun, T.O.; Territo, K.; Olayiwola, T.; Kumar, R.; Romagnoli, J.A. Harnessing Graph Learning for Surfactant Chemistry: PharmHGT, GCN, and GAT in LogCMC Prediction 2025.

- Brozos, C.; Rittig, J.G.; Bhattacharya, S.; Akanny, E.; Kohlmann, C.; Mitsos, A. Predicting the Temperature Dependence of Surfactant CMCs Using Graph Neural Networks. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2024, 20, 5695–5707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hödl, S.L.; Hermans, L.; Dankloff, P.F.J.; Piruska, A.; Huck, W.T.S.; Robinson, W.E. SurfPro – a Curated Database and Predictive Model of Experimental Properties of Surfactants. Digital Discovery 2025, 4, 1176–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hou, L.; Nan, J.; Ni, B.; Dai, W.; Ge, X. Prediction of Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) of Surfactants Based on Structural Differentiation Using Machine Learning. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2024, 703, 135276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, G.D.; Striolo, A. Machine Learning Prediction of Critical Micellar Concentration Using Electrostatic and Structural Properties as Descriptors. [CrossRef]

- Nugmanov, R.; Dyubankova, N.; Gedich, A.; Wegner, J.K. Bidirectional Graphormer for Reactivity Understanding: Neural Network Trained to Reaction Atom-to-Atom Mapping Task. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 3307–3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallani, A.; Nugmanov, R.; Arjona-Medina, J.; Wegner, J.K.; Tkatchenko, A.; Chernichenko, K. Pretraining Graph Transformers with Atom-in-a-Molecule Quantum Properties for Improved ADMET Modeling 2024.

- Arjona-Medina, J.; Nugmanov, R. Analysis of Atom-Level Pretraining with Quantum Mechanics (QM) Data for Graph Neural Networks Molecular Property Models. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifullin, E.R.; Gimadiev, T.R.; Khakimova, A.A.; Varfolomeev, M.A. Game Changer in Chemical Reagents Design for Upstream Applications: From Long-Term Laboratory Studies to Digital Factory Based On AI. 2024, D031S088R006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RDKit. Available online: https://www.rdkit.org/ (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Pedregosa, F.; Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Varoquaux, G.; Org, N.; Gramfort, A.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Michel, V.; Fr, L.; et al. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. In MACHINE LEARNING IN PYTHON.

- XGBoost Python Package — Xgboost 3.0.5 Documentation. Available online: https://xgboost.readthedocs.io/en/release_3.0.0/python/index.html (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Kwon, Y. Uncertainty-Aware Prediction of Chemical Reaction Yields with Graph Neural Networks. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chython/Chython. Available online: https://github.com/chython/chython (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Chython/Chytorch. Available online: https://github.com/chython/chytorch (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Chython/Chytorch-Rxnmap. Available online: https://github.com/chython/chytorch-rxnmap (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Mukerjee, P.; Mysels, K. NBS NSRDS 36Critical Micelle Concentrations of Aqueous Surfactant Systems, 0 ed.; National Bureau of Standards: Gaithersburg, MD, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Akiba, T.; Sano, S.; Yanase, T.; Ohta, T.; Koyama, M. Optuna: A Next-Generation Hyperparameter Optimization Framework 2019.

| Models | Parameters | R2 | MAE | MSE | RMSE |

| RF | minPath=2, maxPath=12, fpSize=4096 | 0,756 | 0,363 | 0,280 | 0,529 |

| XGB | minPath=2, maxPath=12, fpSize=4096 | 0,764 | 0,372 | 0,271 | 0,520 |

| Models | Parameters | R2 | MAE | MSE | RMSE |

| Hodl et al. model (SurfPro, 2025) | Training set: 1395 points Test set: 140 points Model: single property AttentiveFP GNN Temperature range: 20-40 °C MM limit: 4672 g/mol (≥2000) |

– | 0,241 | – | 0,365 |

| Our GNN Model | Training set: 1829 points Test set: 140 points Model: GNN (log CMC&uncertainty output) Temperature range: 5-85 °C MM limit: 1300 g/mol |

0,892 | 0,244 | 0,124 | 0,352 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).