Submitted:

05 December 2025

Posted:

08 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments and Variables

2.2.1. Assessment of Falls

2.2.2. Skeletal Muscle Mass

2.2.3. Handgrip Strength

2.2.4. Lower Limb Strength and Power

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CI | Confidence intervals |

| 5xSTS | Five Times Sit-to-Stand Test |

| HGS | Handgrip strength |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| SPPB | Short Physical Performance Battery |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SMM | Skeletal muscle mass |

| W | Sit-to-stand Power |

References

- Reider, N.; Gaul, C. Fall risk screening in the elderly: A comparison of the minimal chair height standing ability test and 5-repetition sit-to-stand test. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 2016, 65, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, S.R.; Cruz-Montecinos, C.; Ratel, S.; Pinto, R.S. Powerpenia Should be Considered a Biomarker of Healthy Aging. Sports Med Open 2024, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, F.; Liperoti, R.; Russo, A.; Giovannini, S.; Tosato, M.; Capoluongo, E.; Bernabei, R.; Onder, G. Sarcopenia as a risk factor for falls in elderly individuals: Results from the ilSIRENTE study. Clinical Nutrition 2012, 31, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreland, J.D.; Richardson, J.A.; Goldsmith, C.H.; Clase, C.M. Muscle Weakness and Falls in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2004, 52, 1121–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, N.; Darvishi, N.; Ahmadipanah, M.; Shohaimi, S.; Mohammadi, M. Global prevalence of falls in the older adults: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 2022, 17, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampaio, F.; Nogueira, P.; Ascenção, R.; Henriques, A.; Costa, A. The epidemiology of falls in Portugal: An analysis of hospital admission data. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0261456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S.L.; Lucchesi, L.R.; Bisignano, C.; Castle, C.D.; Dingels, Z.V.; Fox, J.T.; Hamilton, E.B.; Henry, N.J.; Krohn, K.J.; Liu, Z.; et al. The global burden of falls: global, regional and national estimates of morbidity and mortality from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Injury Prevention 2020, 26, i3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-H.; Liu, C.-Y.; Huang, C.-C.; Rong, J.-R. Frailty and Quality of Life among Older Adults in Communities: The Mediation Effects of Daily Physical Activity and Healthy Life Self-Efficacy. Geriatrics 2022, 7, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Odasso, M.; van der Velde, N.; Martin, F.C.; Petrovic, M.; Tan, M.P.; Ryg, J.; Aguilar-Navarro, S.; Alexander, N.B.; Becker, C.; Blain, H.; et al. World guidelines for falls prevention and management for older adults: a global initiative. Age and Ageing 2022, 51 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, A.; Kamaruzzaman, S.B.; Tan, M.P. Polypharmacy and falls in older people: Balancing evidence-based medicine against falls risk. Postgrad Med 2015, 127, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, T.; Akishita, M.; Nakamura, T.; Nomura, K.; Ogawa, S.; Iijima, K.; Eto, M.; Ouchi, Y. Polypharmacy as a risk for fall occurrence in geriatric outpatients. Geriatrics & Gerontology International 2012, 12, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, I.H. Summary comments: Epidemiological and methodological problems in determining nutritional status of older persons. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1989, 50, 1231–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, K.F.; Fielding, R.A. Skeletal Muscle Power: A Critical Determinant of Physical Functioning in Older Adults. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews 2012, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivunen, K.; Sillanpää, E.; von Bonsdorff, M.; Sakari, R.; Törmäkangas, T.; Rantanen, T. Mortality Risk Among Older People Who Did Versus Did Not Sustain a Fracture: Baseline Prefracture Strength and Gait Speed as Predictors in a 15-Year Follow-Up. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A 2019, 75, 1996–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, J.F.; Leveille, S.G.; Kiely, D.K.; Bandinelli, S.; Guralnik, J.M.; Ferrucci, L. A Comparison of Leg Power and Leg Strength Within the InCHIANTI Study: Which Influences Mobility More? The Journals of Gerontology: Series A 2003, 58, M728–M733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcazar, J.; Rodriguez-Lopez, C.; Ara, I.; Alfaro-Acha, A.; Rodríguez-Gómez, I.; Navarro-Cruz, R.; Losa-Reyna, J.; García-García, F.J.; Alegre, L.M. Force-velocity profiling in older adults: An adequate tool for the management of functional trajectories with aging. Exp Gerontol 2018, 108, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, S.S.Y.; Reijnierse, E.M.; Pham, V.K.; Trappenburg, M.C.; Lim, W.K.; Meskers, C.G.M.; Maier, A.B. Sarcopenia and its association with falls and fractures in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019, 10, 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Rekeneire, N.; Visser, M.; Peila, R.; Nevitt, M.C.; Cauley, J.A.; Tylavsky, F.A.; Simonsick, E.M.; Harris, T.B. Is a fall just a fall: correlates of falling in healthy older persons. The Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003, 51, 841–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srikanthan, P.; Karlamangla, A.S. Muscle Mass Index As a Predictor of Longevity in Older Adults. The American Journal of Medicine 2014, 127, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, E.; Pin, F.; Gorini, S.; Pontecorvo, L.; Ferri, A.; Mollace, V.; Costelli, P.; Rosano, G. Improvement of skeletal muscle performance in ageing by the metabolic modulator Trimetazidine. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2016, 7, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdijk, L.B.; Koopman, R.; Schaart, G.; Meijer, K.; Savelberg, H.H.C.M.; van Loon, L.J.C. Satellite cell content is specifically reduced in type II skeletal muscle fibers in the elderly. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 2007, 292, E151–E157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashida, I.; Tanimoto, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Kusabiraki, T.; Tamaki, J. Correlation between Muscle Strength and Muscle Mass, and Their Association with Walking Speed, in Community-Dwelling Elderly Japanese Individuals. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e111810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, F.; Domingos, C.; Monteiro, D.; Morouço, P. A Review on Aging, Sarcopenia, Falls, and Resistance Training in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. International journal of environmental research and public health 2022, 19, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, C.; Ogata, S.; Okano, T.; Toyoda, H.; Mashino, S. Long-term participation in community group exercise improves lower extremity muscle strength and delays age-related declines in walking speed and physical function in older adults. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act 2021, 18, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrington, C.; Fairhall, N.J.; Wallbank, G.K.; Tiedemann, A.; Michaleff, Z.A.; Howard, K.; Clemson, L.; Hopewell, S.; Lamb, S.E. Exercise for preventing falls in older people living in the community. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, W.J.S.; Lopes, A.D.; Nogueira, E.; Candido, V.; de Moraes, S.A.; Perracini, M.R. Physical Activity Level and Risk of Falling in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Aging Phys Act 2018, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannini, S.; Brau, F.; Galluzzo, V.; Santagada, D.A.; Loreti, C.; Biscotti, L.; Laudisio, A.; Zuccalà, G.; Bernabei, R. Falls among Older Adults: Screening, Identification, Rehabilitation, and Management. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 7934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelton, D.A.; Becker, C.; Lamb, S.E.; Close, J.C.T.; Zijlstra, W.; Yardley, L.; Todd, C.J. Prevention of Falls Network Europe: a thematic network aimed at introducing good practice in effective falls prevention across Europe. Eur J Ageing 2004, 1, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marconcin, P.; São Martinho, E.; Serpa, J.; Honório, S.; Loureiro, V.; Nascimento, M.d.M.; Flôres, F.; Santos, V. Grip Strength, Fall Efficacy, and Balance Confidence as Associated Factors with Fall Risk in Middle-Aged and Older Adults Living in the Community. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 7617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society, A.G.; Society, G.; Of, A.A. On Falls Prevention, O.S.P. Guideline for the Prevention of Falls in Older Persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2001, 49, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.C.; Wang, Z.; Heo, M.; Ross, R.; Janssen, I.; Heymsfield, S.B. Total-body skeletal muscle mass: development and cross-validation of anthropometric prediction models123. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2000, 72, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlüssel, M.M.; dos Anjos, L.A.; de Vasconcellos, M.T.; Kac, G. Reference values of handgrip dynamometry of healthy adults: a population-based study. Clin Nutr 2008, 27, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guralnik, J.M.; Simonsick, E.M.; Ferrucci, L.; Glynn, R.J.; Berkman, L.F.; Blazer, D.G.; Scherr, P.A.; Wallace, R.B. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol 1994, 49, M85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences; routledge, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Youden, W.J. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer 1950, 3, 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bartosch, P.S.; Kristensson, J.; McGuigan, F.E.; Akesson, K.E. Frailty and prediction of recurrent falls over 10 years in a community cohort of 75-year-old women. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research 2020, 32, 2241–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riviati, N.; Indra, B. Relationship between muscle mass and muscle strength with physical performance in older adults: A systematic review. SAGE Open Med 2023, 11, 20503121231214650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buatois, S.; Perret-Guillaume, C.; Gueguen, R.; Miget, P.; Vançon, G.; Perrin, P.; Benetos, A. A Simple Clinical Scale to Stratify Risk of Recurrent Falls in Community-Dwelling Adults Aged 65 Years and Older. Physical Therapy 2010, 90, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albalwi, A.A.; Alharbi, A.A. Optimal procedure and characteristics in using five times sit to stand test among older adults: A systematic review. Medicine 2023, 102, e34160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Vélez, R.; Izquierdo, M.; García-Hermoso, A.; Ordoñez-Mora, L.T.; Cano-Gutierrez, C.; Campo-Lucumí, F.; Pérez-Sousa, M.Á. Sit to stand muscle power reference values and their association with adverse events in Colombian older adults. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 11820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, Y.; Won, C.W. Sex differences in impact of sarcopenia on falls in community-dwelling Korean older adults. BMC Geriatrics 2021, 21, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, M.; Kim, D.H.; Cho, I.; Ham, O.K. Age and Gender Differences in Fall-Related Factors Affecting Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Journal of Nursing Research 2023, 31, e270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Total (n = 280) | Male (n = 69) | Female (n = 211) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 71.88 ± 5.35 | 73.07 ± 6.10 | 71.49 ± 5.04 | 0.055 |

| Body Weight (kg) | 68.56 ± 11.32 | 75.19 ± 10.84 | 66.40 ± 10.64 | < 0.001 |

| Height (m) | 1.58 ± 0.07 | 1.66 ± 0.06 | 1.55 ± 0.05 | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.29 ± 4.02 | 27.21 ± 3.93 | 27.32 ± 4.06 | 0.840 |

| Nº Medications | 3.35 ± 2.55 | 3.79 ± 2.61 | 3.20 ± 2.53 | 0.105 |

| Nº Comorbidities | 2.45 ± 1.73 | 2.66 ± 2.03 | 2.33 ± 1.62 | 0.216 |

| SMM (kg) | 20.36 ± 5.03 | 27.47 ± 3.02 | 18.03 ± 2.96 | < 0.001 |

| HGS (kgf) | 24.80 ± 7.18 | 33.43 ± 7.38 | 21.97 ± 4.29 | < 0.001 |

| LLS (s) | 8.80 ± 1.60 | 8.54 ± 1.44 | 8.89 ± 1.65 | 0.087 |

| Power (W) | 258.51 ± 76.36 | 323.31 ± 83.34 | 237.33 ± 60.56 | < 0.001 |

| Variables | Total (n=280) | Male (n=69) | Female (n=211) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nº Falls in the last 12 months, M (±SD) | 0.52 ± 1.25 | 0.26 ± 0.61 | 0.61 ± 1.38 |

| Falls in the last 12 months, n (%) Yes No |

74 (26.4) 206 (73.6) |

13 (18.8) 56 (81.2) |

61 (28.9) 150 (71.1) |

| Require intervention, n (%) Yes No |

21 (7.5) 259 (92.5) |

6 (8.7) 63 (91.3) |

15 (7.1) 196 (92.9) |

| Have balance/gait problems, n (%) Yes No |

116 (41.4) 164 (58.6) |

21 (30.4) 48 (69.6%) |

95 (45.0) 116 (55.0) |

| Variables | Non-Fallers (n=206) | Fallers (n=74) | t | p-Value | Cohen´s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMM (kg) | 20.53 ± 5.05 | 19.89 ± 4.98 | 0.93 | 0.353 | 0.126 |

| HGS (kgf) | 25.39 ± 7.34 | 23.15 ± 6.49 | 2.31 | 0.022 | 0.313 |

| LLS (s) | 8.65 ± 1.53 | 9.24 ± 1.72 | -2.73 | 0.007 | -0.371 |

| Power (W) | 261.98 ± 71.89 | 248.88 ± 87.42 | 1.26 | 0.206 | 0.172 |

| Variables | Crude OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted OR¹ (95% CI) | p-Value | Final Model² OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMM (kg) | 0.97 (0.92 – 1.02) | 0.975 | 1.07 (0.97 – 1.18) | 0.168 | 0.77 (0.51 – 1.16) | 0.219 |

| HGS (kgf) | 0.95 (0.91- 0.99) | 0.023 | 0.96 (0.91 – 1.01) | 0.161 | 0.94 (0.88 – 1.01) | 0.119 |

| LLS (s) | 1.24 (1.05 – 1.47) | 0.008 | 1.21 (1.03 – 1.43) | 0.019 | 1.78 (1.11 – 2.85) | 0.016 |

| Power (W) | 0.99 (0.99 – 1.00) | 0.207 | 1.00 (0.99 – 1.00) | 0.882 | 1.01 (0.99 – 1.03) | 0.062 |

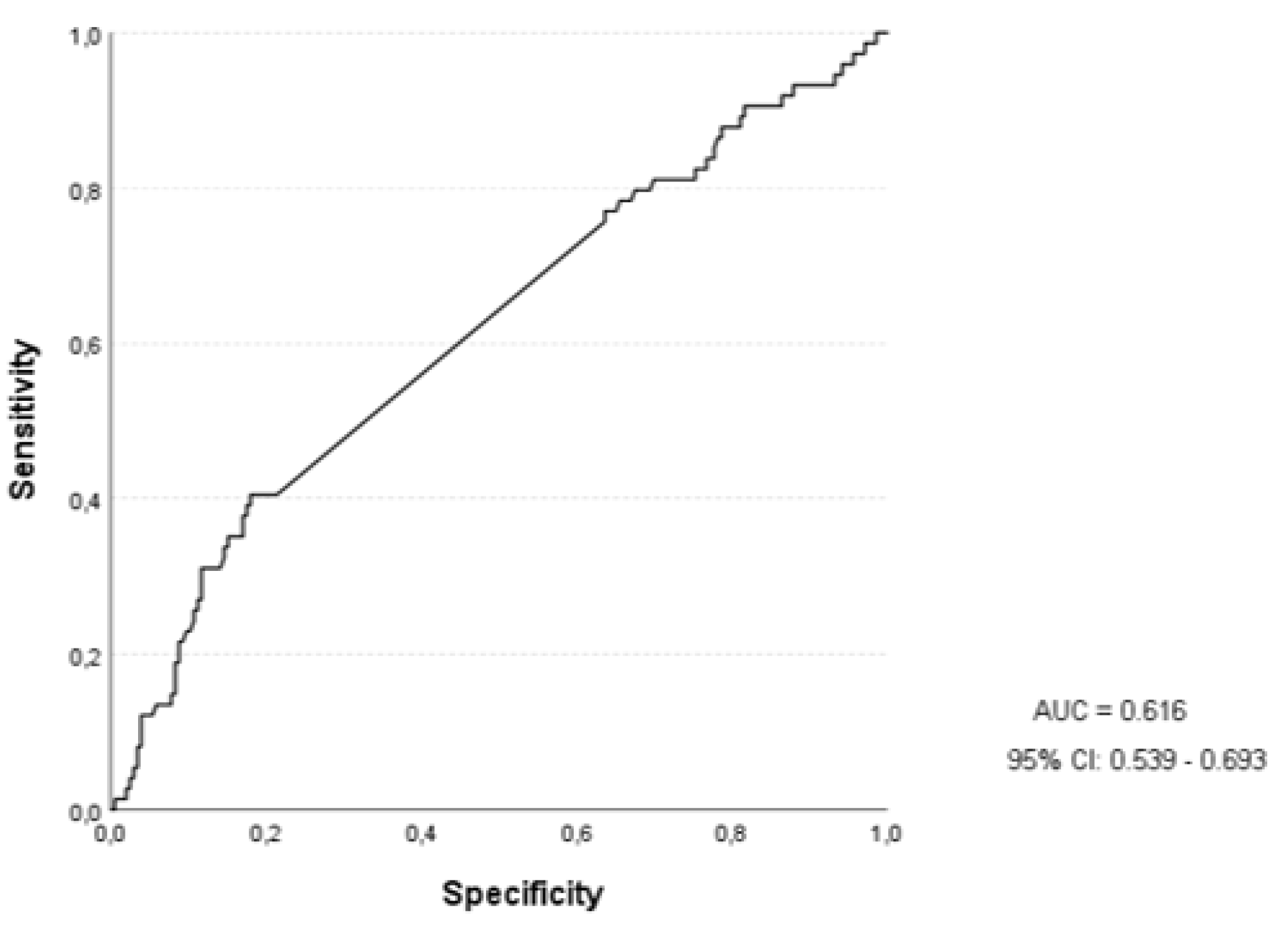

| Variables | AUC | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMM (kg) | 0.470 | 0.393 – 0.547 | 0.393 |

| HGS (kgf) | 0.397 | 0.320 – 0.474 | 0.009 |

| LLS (s) | 0.616 | 0.539 – 0.693 | 0.003 |

| Power (W) | 0.424 | 0.346 – 0.503 | 0.054 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).