Submitted:

05 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 81-10

1. Introduction

Motivation

2. Zitterbewegung Formulation

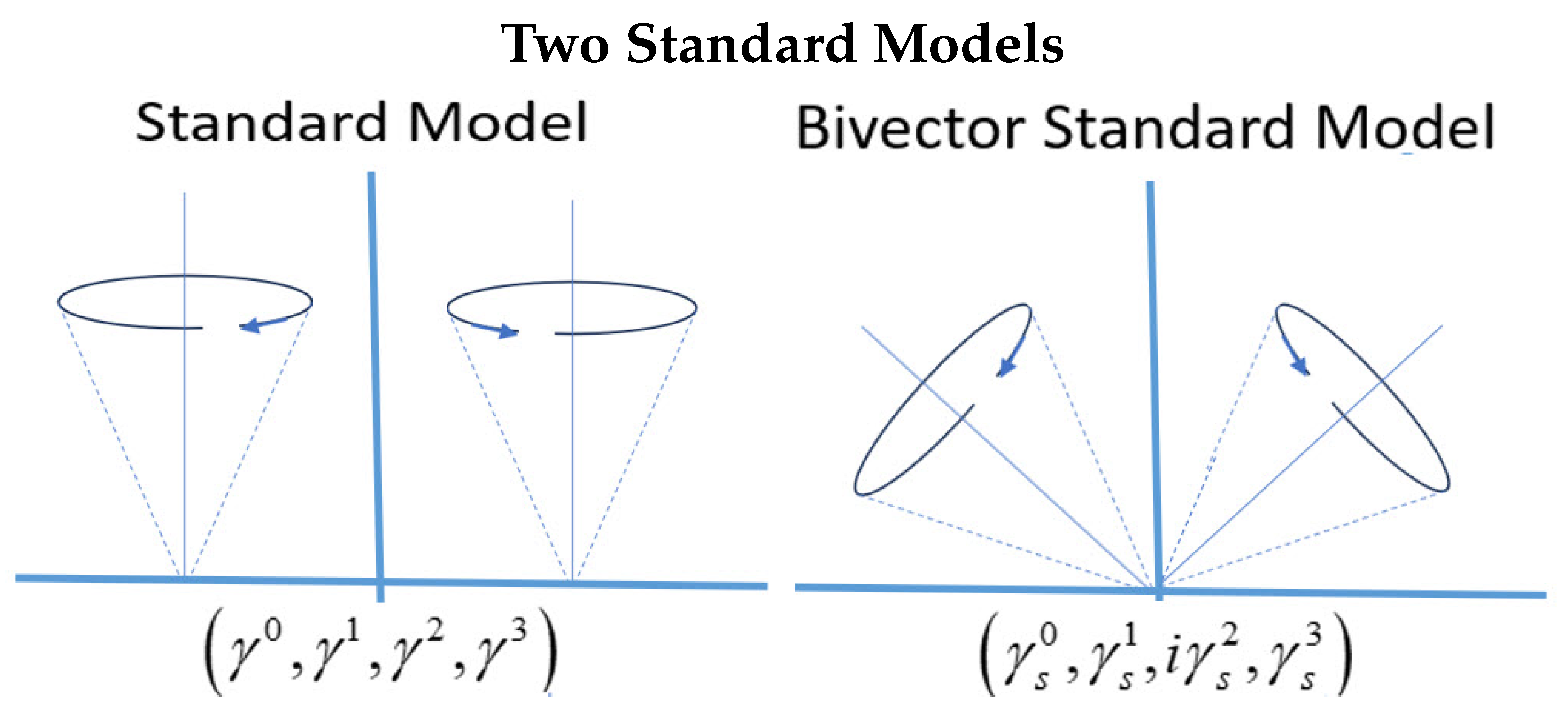

3. Bivector Dynamics

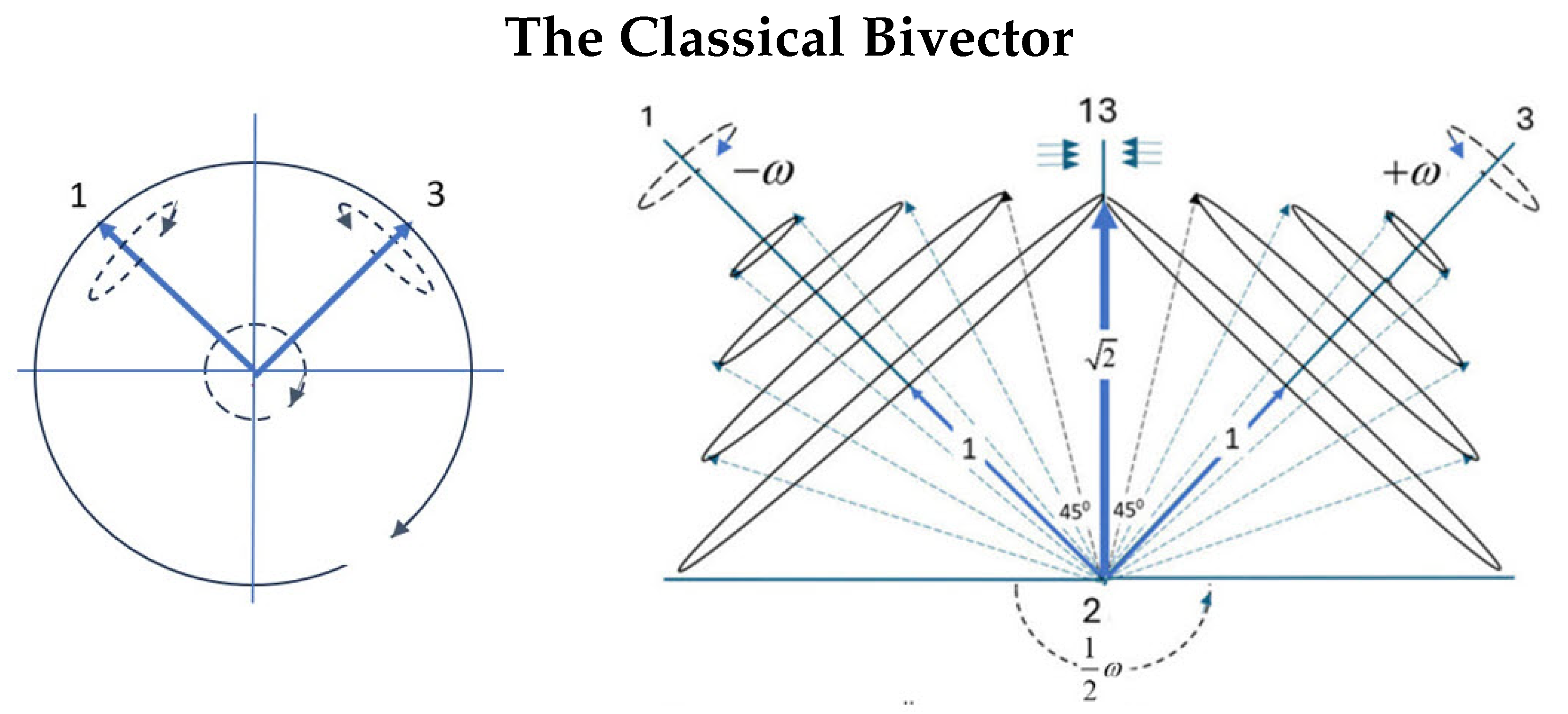

3.1. Classical Bivector Geometry

3.2. Parity

3.3. Internal Isotropy

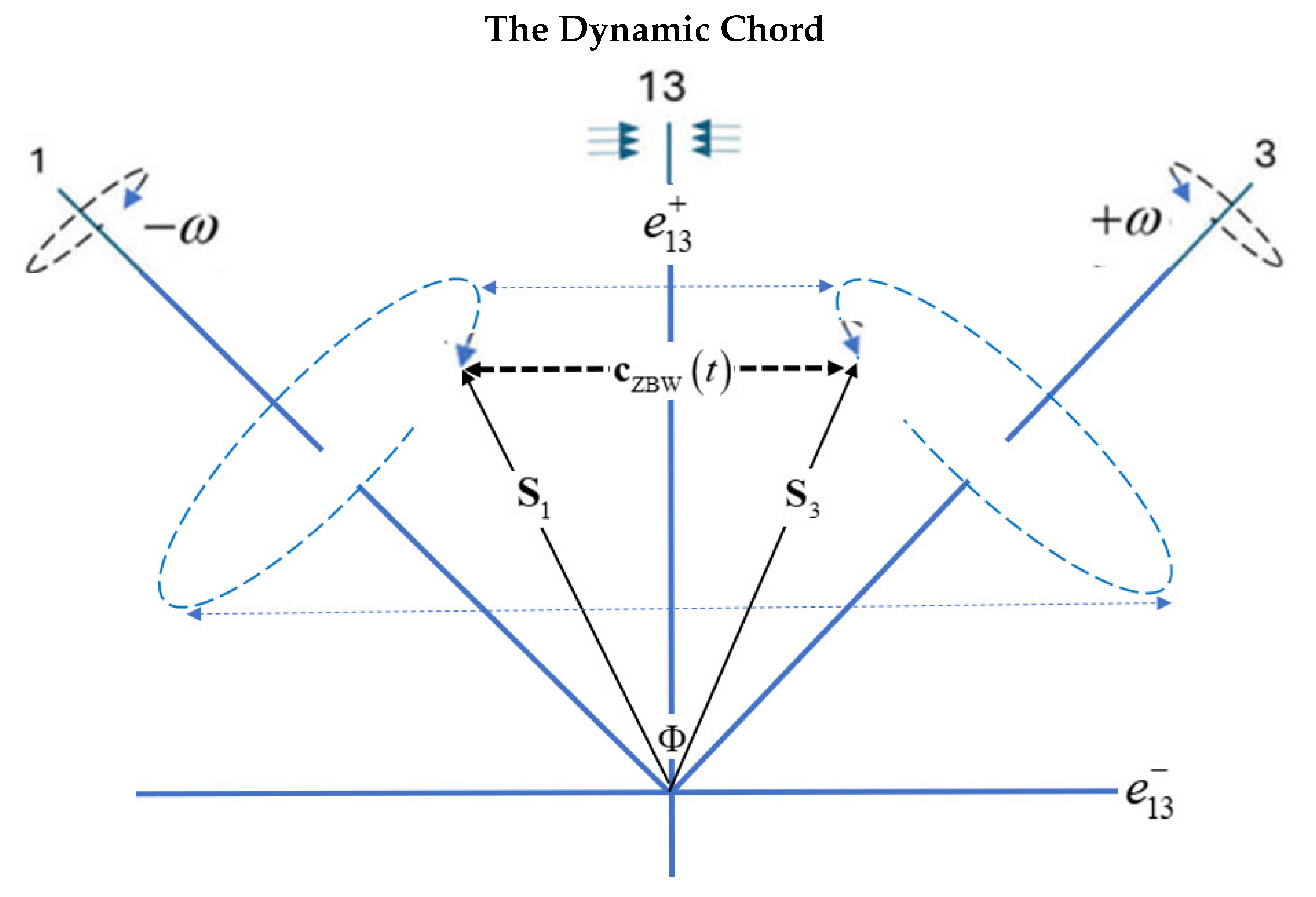

4. The ZBW Chord

4.1. The ZBW Origin

4.2. Double Cover and Projection to the LFF

4.3. Projection to the Laboratory Frame

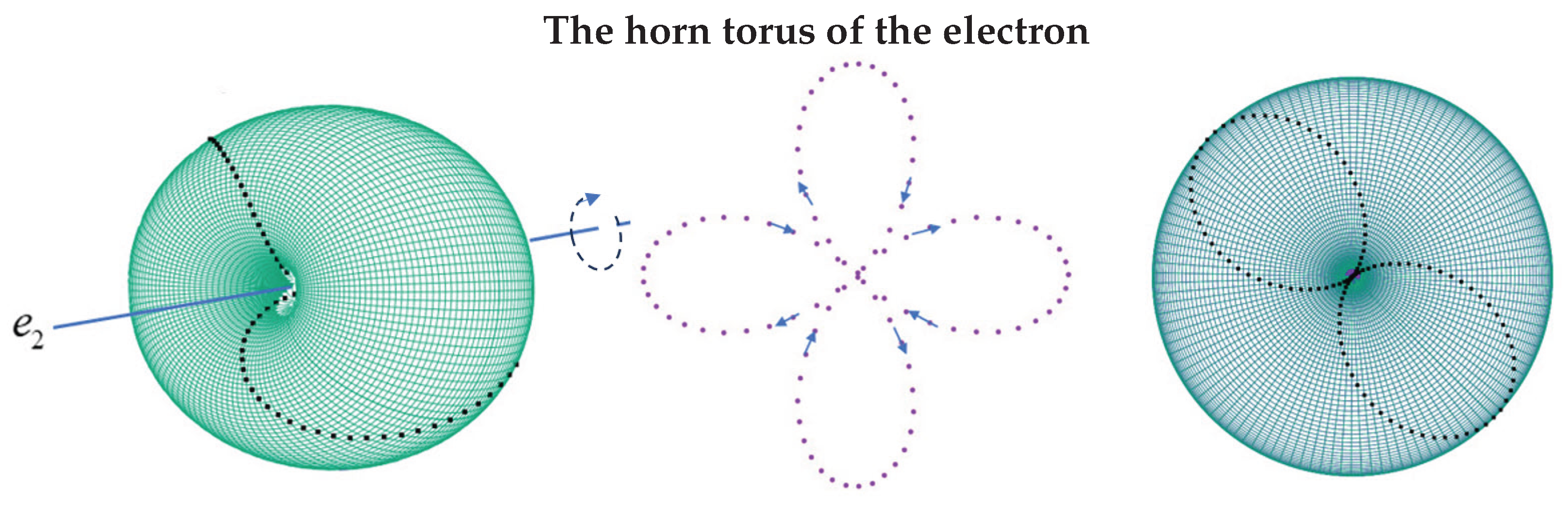

5. Toroidal Structure

Toroidal Models

6. The Internal Clock

de Broglie Wavelength

7. Discussion

Appendix A. Derivation of the Zitterbewegung

Appendix A.1. Dirac Equation and Hamiltonian Form

Appendix A.2. Velocity Operator

Appendix A.3. Evolution of the Velocity Operator

Appendix A.4. Position Operator and the ZBW

References

- Schrödinger, E. Über die kräftefreie Bewegung in der relativistischen Quantenmechanik. Sitzungsber. Preuss. Akad. Wiss 1930, 418–428. [Google Scholar]

- Sanctuary, B. Quaternion Spin. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanctuary, B. The Fine-Structure Constant in the Bivector Standard Model. Axioms 2025, 14, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirac, P.A.M. The quantum theory of the electron. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Contain. Pap. A Math. Phys. Character 1928, 117, 610–624. [Google Scholar]

- Dirac, P.A.M. A Theory of Electrons and Protons. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1930, 126, 360–365. [Google Scholar]

- Peskin, M.; Schroeder, D.V. An Introduction To Quantum Field Theory; Frontiers in Physics: Boulder, CO, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Doran, C.; Lasenby, J. Geometric Algebra for Physicists; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- David, G.; Cserti, J. General theory of ZBW. Physical Review B—Condensed Matter and Materials Physics 2010, 81(12), 121417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaller, B. The dirac equation; Springer Science & Business Media, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Greiner, W. Relativistic quantum mechanics; Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1990; Vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Bjorken, J. D.; Drell, S. D.; Mansfield, J. E. Relativistic quantum mechanics; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Schrödinger, E. Collected Papers on Wave Mechanics; Blackie & Son, London, 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Foldy, L. L.; Wouthuysen, S. A. On the Dirac theory of spin 1/2 particles and its non-relativistic limit. Physical Review 1950, 78(1), 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barut, A. O.; Zanghi, N. Classical model of the Dirac electron. Physical Review Letters 1984, 52(23). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, W. A., Jr.; Vaz, J., Jr.; Recami, E.; Salesi, G. About zitterbewegung and electron structure. Physics Letters B 1993, 318(4), 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hestenes, D. Spacetime physics with geometric algebra. American Journal of Physics 2003, 71(7), 691–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hestenes, D. The zitterbewegung interpretation of quantum mechanics. Found. Phys. 1990, 20, 1213–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerritsma, R. Quantum simulation of the Dirac equation. Nature 2010, 463, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatt, M.; Roos, R.C. F. Quantum simulations with trapped ions. Nature Physics 2012, 8(4), 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Arrazola, I.; Pedernales, J. S.; Lamata, L.; Solano, E. Digital-analog quantum simulation of spin models in trapped ions. Scientific reports 2016, 6(1), 30534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreisow, F.; Heinrich, M.; Keil, R.; Tünnermann, A.; Nolte, S.; Longhi, S.; Szameit, A. Classical simulation of relativistic Zitterbewegung in photonic lattices. Physical Review Letters 2010, 105(14), 143902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insulators, T. Dirac Dynamics in Waveguide Arrays: From Zitterbewegung to Photonic. Quantum Simulations with Photons and Polaritons: Merging Quantum Optics with Condensed Matter Physics 2017, 181. [Google Scholar]

- Rusin, K.; Zawadzki, T. M.W. Zitterbewegung (Trembling Motion) of Electrons in Graphene. In Graphene Simulation. IntechOpen; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens, S.; Zhu, S. Y.; Jiang, J.; Sun, Y. Simulation of Zitterbewegung by modelling the Dirac equation in metamaterials. New Journal of Physics 2015, 17(11), 113021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R. L.; Chou, Y. J.; Hwang, R. R. Photonic surface Dirac cones in reciprocal magnetoelectric metamaterials. Journal of Applied Physics 2025, 138(20). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, L. J.; Beeler, M. C.; Jimenez-Garcia, K.; Perry, A. R.; Sugawa, S.; Williams, R. A.; Spielman, I. B. Direct observation of zitterbewegung in a Bose–Einstein condensate. New Journal of Physics 2013, 15(7), 073011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, H. Classical Mechanics; Addison-Wesley Publishing Compangy, Inc.: Reading, MA, USA, 1950; ISBN 0-201-02510-8. [Google Scholar]

- Do Carmo, M. P. Differential geometry of curves and surfaces: revised and updated second edition; Courier Dover Publications, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Parson, A. L. A magneton theory of the structure of the atom. In Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections; 1915; Volume 65. [Google Scholar]

- Consa, O. Helical solenoid model of the electron. Progress in Physics 2018, 14(2), 80–89. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos, C. A.; Fleury, M. J. A simple electromagnetic model of the electron. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.22384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, J. G.; Van der Mark, M. B. Is the electron a photon with toroidal topology. In Annales de la Fondation Louis de Broglie; Fondation Louis de Broglie, January 1997; Vol. 22, No. 2, p. 133. [Google Scholar]

- Fleury, M. J.; Rousselle, O. Critical Review of Zitterbewegung Electron Models. Symmetry 2025, 17(3), 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R. D.; Prasad, N. R.; Prasad, N.; Prasad, S. R.; Prasad, R. S.; Prasad, R. B.; Shaikh, A. D. A Review on Scattering Techniques for Analysis of Nanomaterials and Biomaterials. Engineered Science 2024, 33, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, G. Structure determination by low-energy electron diffraction—A roadmap to the future. Surface Science 2025, 754, 122696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, X.; Bittencourt, C.; Van Tendeloo, G. Possibilities and limitations of advanced transmission electron microscopy for carbon-based nanomaterials. Beilstein journal of nanotechnology 2015, 6(1), 1541–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egerton, R. F.; Watanabe, M. Spatial resolution in transmission electron microscopy. Micron 2022, 160, 103304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noether, E. Invariante Variations probleme. Gott. Nachr 1918, 235–257. [Google Scholar]

- Sanctuary, B. Spin Helicity and the Disproof of Bell’s Theorem. Quantum Rep. 2024, 6, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanctuary, B. EPR Correlations Using Quaternion Spin. Quantum Rep. 2024, 6, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.S. On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen paradox. Phys. Phys. Fiz. 1964, 1, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).