Submitted:

04 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Regulatory Perspectives on Function Allocation (FA)

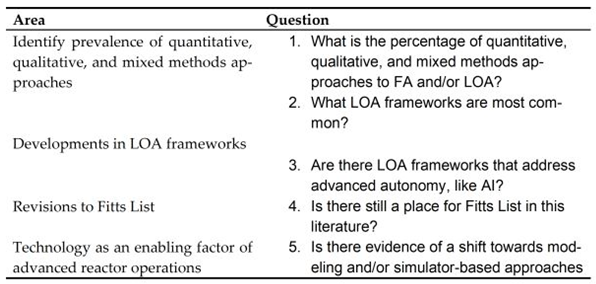

1.3. Review Objectives

2. Methodology

2.1. Systematic Literature Review Definition

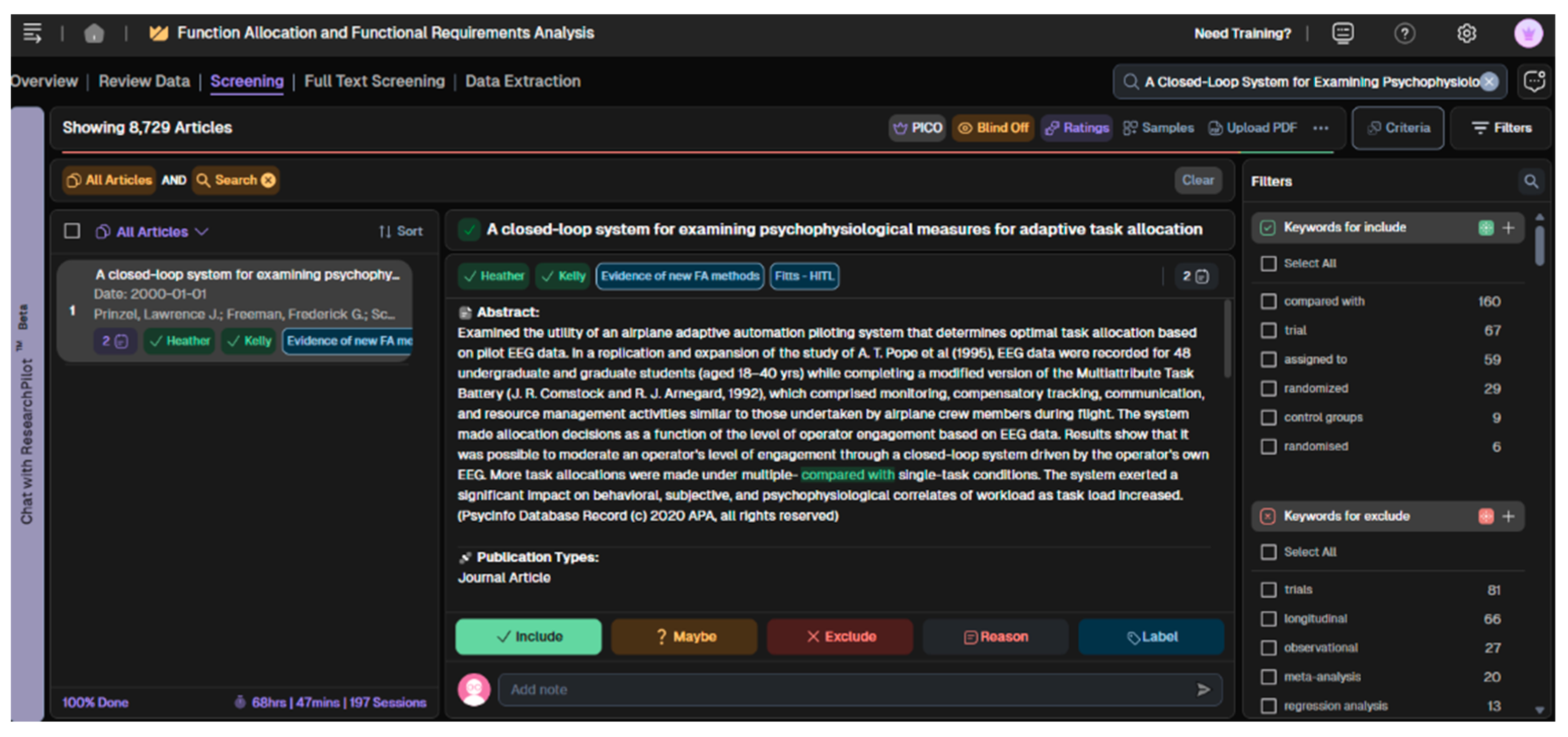

2.2. SLR Software

2.3. Procedures

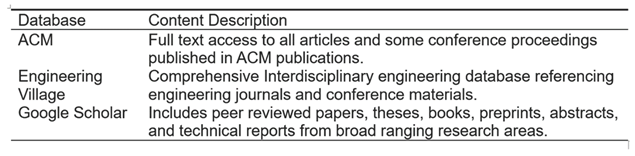

2.4. Database Selection

2.5. Definition of Search Criteria

2.6. Keyword mapping

2.7. Extraction and Storage of Citation Data

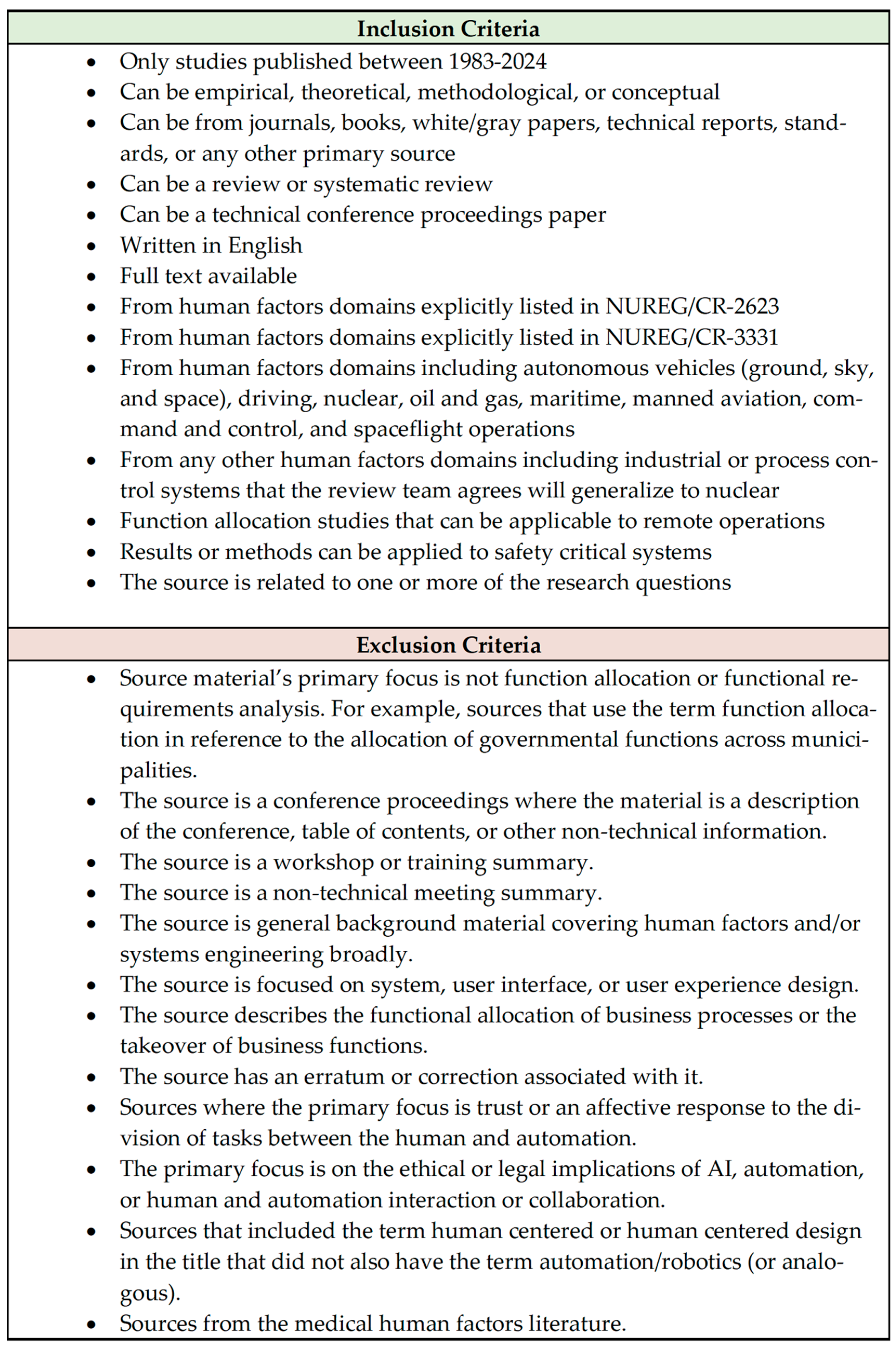

2.7.1. Screening Process

2.7.2. Title-Level Screening

2.7.3. Abstract-Level Screening

2.7.4. Full-Text Screening

2.7.5. Final Screening

2.7.6. Backwards Forwards Search

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Literature Characteristics

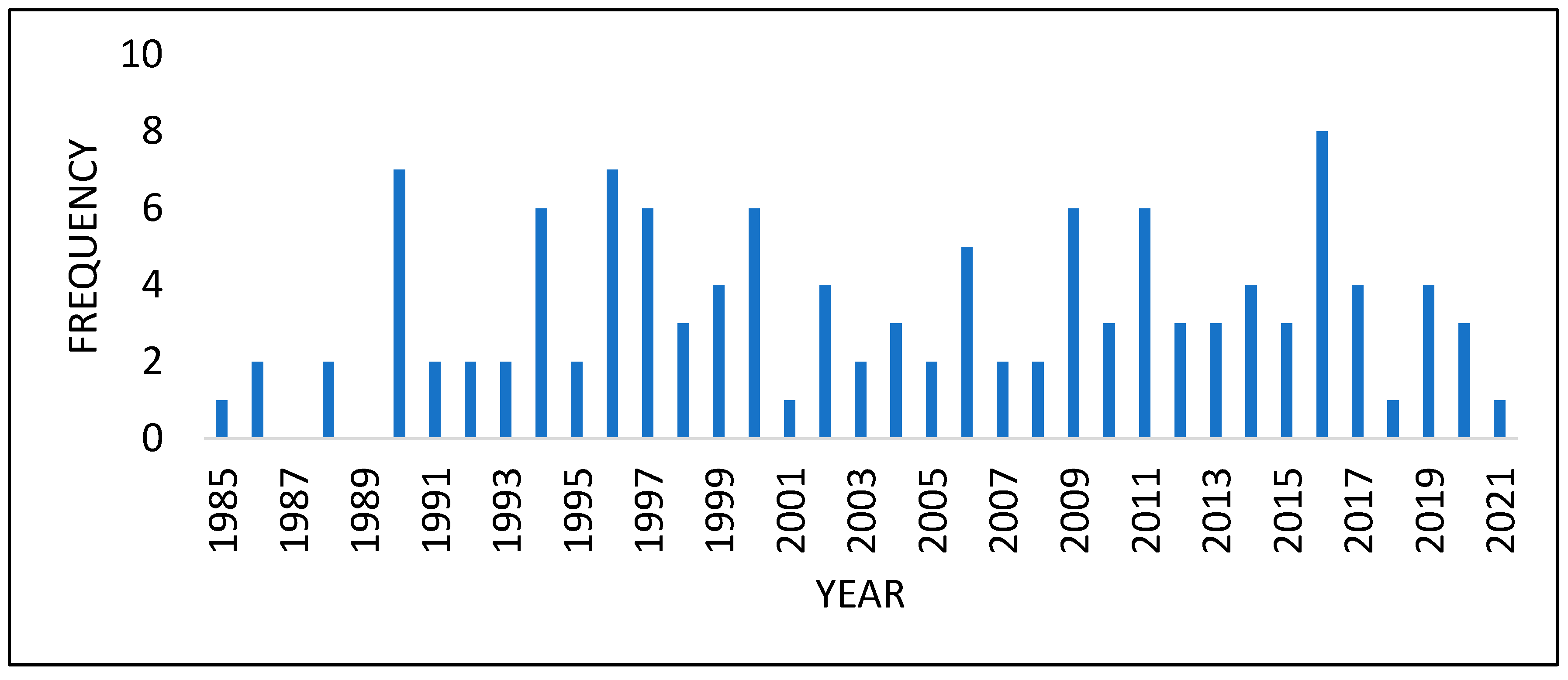

3.2. Publications by Year

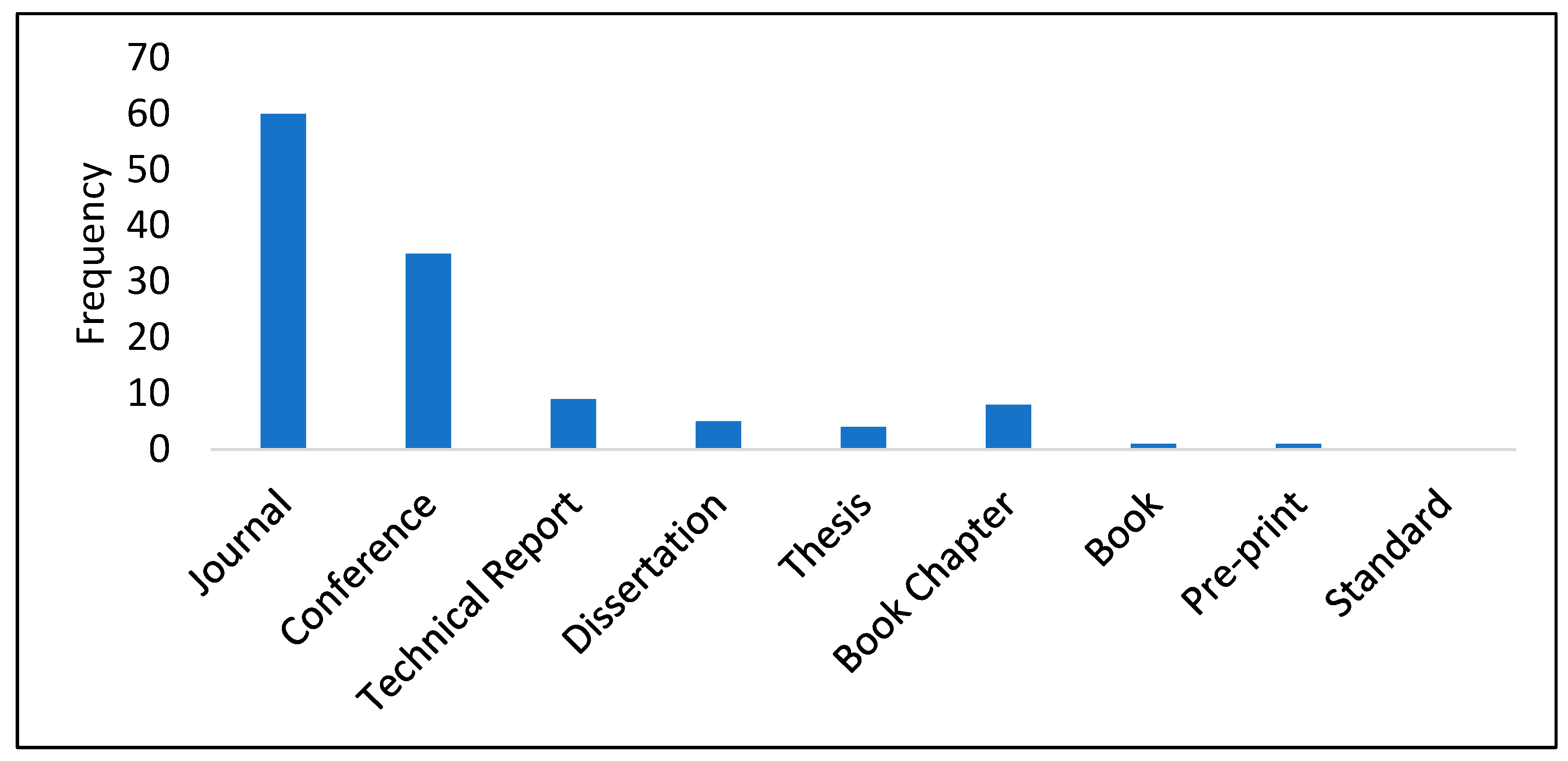

3.3. Publication Types

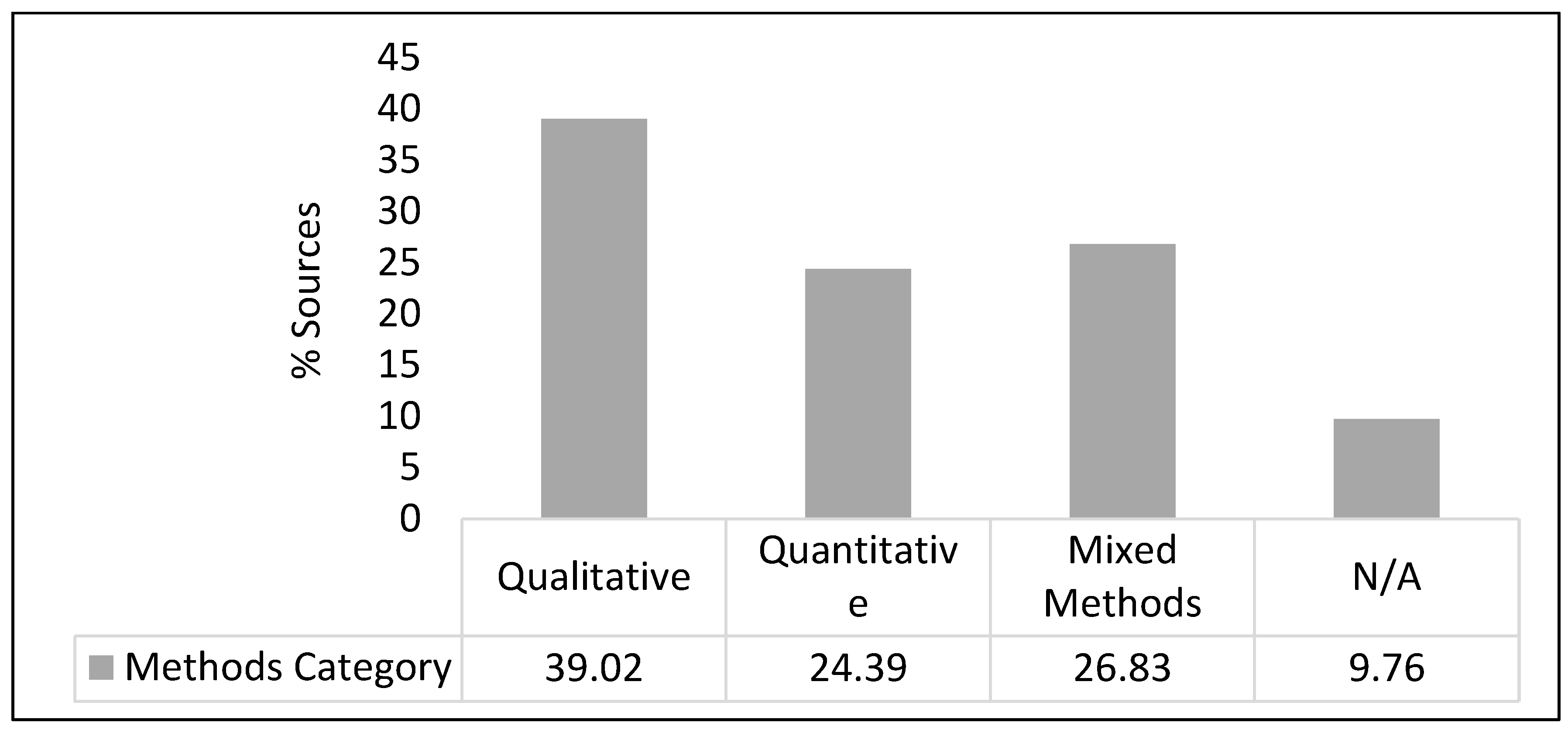

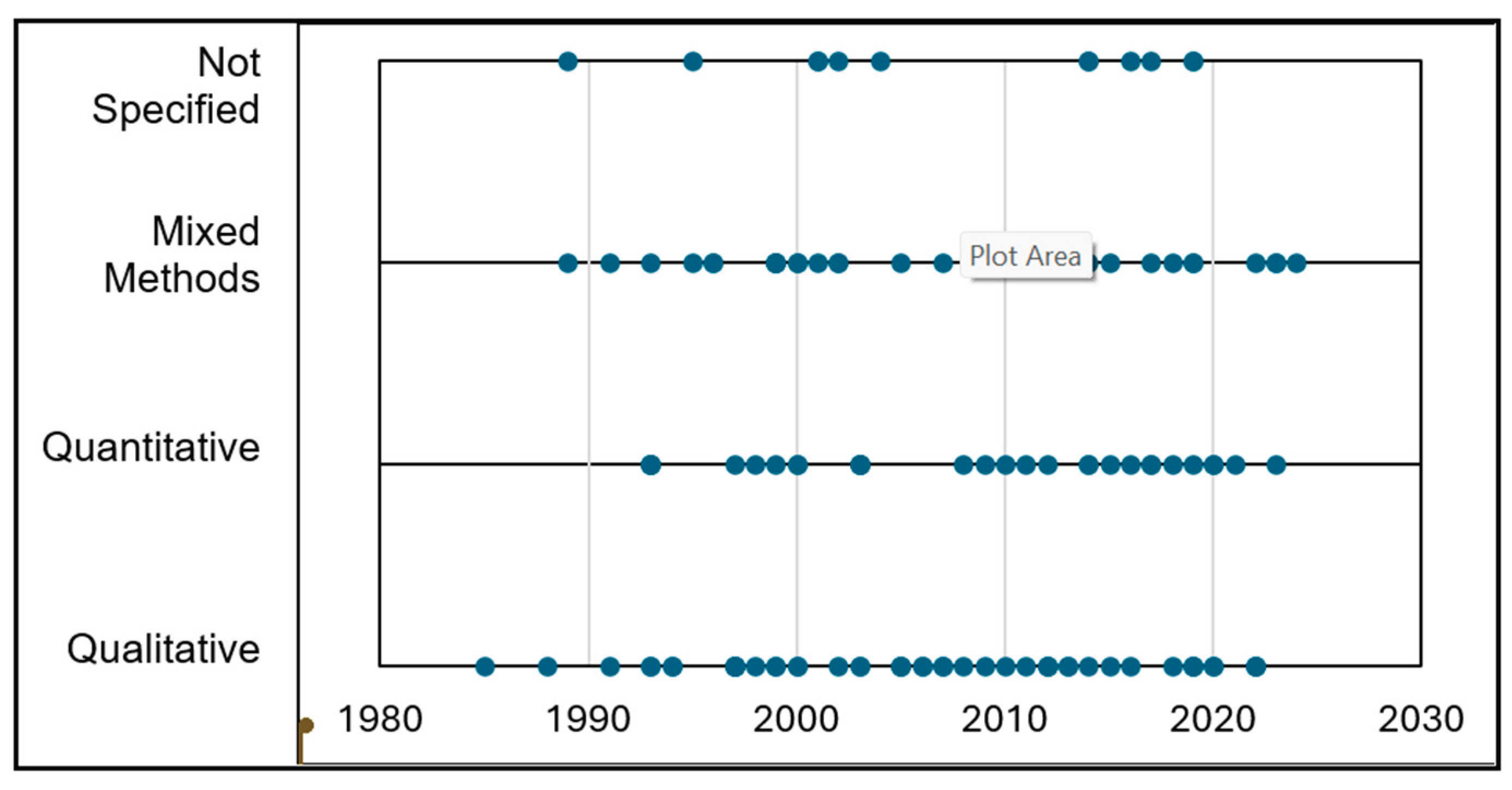

3.4. Representation of Methodological Approaches

3.5. Are Quantitative Approaches Newer?

3.6. Benefits and Drawbacks of Different Types of Frameworks

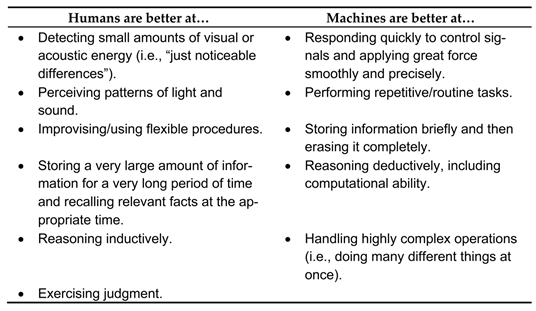

3.7. What is the Role of Fitts List in Contemporary Function Allocation (FA)

3.8. How Do Improvements in AI Change Perspectives on Function Allocation (FA)?

3.9. Keeping the Human in the Loop

4. Conclusions

4.1. Data-Driven and Simulator-Based Approaches

4.2. Function Allocation Pre- and Post-1983: New Challenges for Long Standing Frameworks

Appendix A

- Abbass, H. A. (2019). Social integration of artificial intelligence: functions, automation allocation logic and human-autonomy trust. Cognitive Computation, 11(2), 159-171.

- Andersson, J., & Osvalder, A. L. (2007). Automation inflicted differences on operator performance in nuclear power plant control rooms (No. NKS--152). Nordisk Kernesikkerhedsforskning, Roskilde (Denmark).

- Baird, I. C. (2019). The development of the human-automation behavioral interaction task (HABIT) analysis framework [Master’s thesis, Wright State University].

- Beevis, D. (Ed.). (1999). Analysis techniques for human-machine systems design: A report produced under the auspices of NATO defence research group panel 8. Crew Systems Ergonomics/Human Systems Technology Information Analysis Center.

- Beevis, D., Essens, P., & Schuffel, H. (1996). Improving function allocation for integrated systems design (No. CSERIACSOAR9601). Crew System Ergonomics Information Analysis Center.

- Behymer, K. J., & Flach, J. M. (2016). From autonomous systems to sociotechnical systems: Designing effective collaborations. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation, 2(2), 105-114.

- Bevacqua, G., Cacace, J., Finzi, A., & Lippiello, V. (2015, April). Mixed-initiative planning and execution for multiple drones in search and rescue missions. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Automated Planning and Scheduling (Vol. 25, pp. 315-323).

- Bilimoria, K.D., Johnson, W.W., & Schutte, P.C\. (2014). Conceptual framework for single pilot operations. Proceedings of the International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction in Aerospace.

- Bindewald, J. M., Miller, M. E., & Peterson, G. L. (2014). A function-to-task process model for adaptive automation system design. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 72(12), 822-834.

- Bloch, M., Eitrheim, M., Mackay, A., & Sousa, E. (2023). Connected, Cooperative and Automated Driving: Stepping away from dynamic function allocation towards human-machine collaboration. Transportation research procedia, 72, 431-438.

- Bost, J.R., Malone, T.B., Baker, C.C., & Williams, C.D. (1996). Human systems integration (HSI) in navy ship manpower reduction. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting.

- Boy, G. A. (2019). FlexTech: From Rigid to Flexible Human–Systems Integration. Systems Engineering in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, 465-481.

- Boy, G.A. (1998). Cognitive function analysis for human-centered automation of safety-critical systems. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

- Bye, A., Hollnagel, E., Hoffmann, M., & Miberg, A.B. (1999). Analysing automation degree and information exchange in joint cognitive systems: FAME, an analytical approach. IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics.

- Byeon, S., Choi, J., & Hwang, I. (2023). A computational framework for optimal adaptive function allocation in a human-autonomy teaming scenario. IEEE Open Journal of Control Systems, 3, 32-44.

- Caldwell, B. S., Nyre-Yu, M., & Hill, J. R. (2019). Advances in human-automation collaboration, coordination and dynamic function allocation. In Transdisciplinary Engineering for Complex Socio-technical Systems (pp. 348-359). IOS Press.

- Clamann, M. P., & Kaber, D. B. (2003). Authority in adaptive automation applied to various stages of human-machine system information processing. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting (Vol. 47, No. 3, pp. 543-547). SAGE Publications.

- Clegg, C., Ravden, S., Corbett, M., & Johnson, G. (1989). Allocating functions in computer integrated manufacturing: a review and a new method. Behaviour & Information Technology, 8(3), 175-190.

- Cook, C., Corbridge, C., Morgan, C., & Turpin, E. (1999). Investigating methods of dynamic function allocation for Naval command and control. International Conference on People in Control (Human Interfaces in Control Rooms, Cockpits and Command Centres) .

- Crouser, R. J., Ottley, A., & Chang, R. (2013). Balancing human and machine contributions in human computation systems. In P. Michelucci (Ed.), Handbook of Human Computation (pp. 615-623). Springer.

- Cummings M.L., How J.P., Whitten A., & Toupet O. (2012). The Impact of Human, Automation Collaboration in Decentralized Multiple Unmanned Vehicle Control. Proceedings of the IEEE.

- Cummings, M. M. (2014). Man versus machine or man+ machine?. IEEE Intelligent Systems, 29(5), 62-69.

- De Greef, T. & Arciszewski, H. (2009). Triggering adaptive automation in naval command and control. In S. Cong (Ed.), Frontiers in Adaptive Control (pp. 165-188). INTECH Open Access Publisher.

- De Greef, T., van Dongen, K., Grootjen, M., & Lindenberg, J. (2007). Augmenting cognition: reviewing the symbiotic relation between man and machine. In International Conference on Foundations of Augmented Cognition (pp. 439-448). Springer

- Dearden, A., Harrison, M., & Wright, P. (2000). Allocation of function: scenarios, context and the economics of effort. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 52(2), 289-318.

- Dekker, S. W., & Woods, D. D. (2002). MABA-MABA or abracadabra? Progress on human–automation co-ordination. Cognition, Technology & Work, 4(4), 240-244.

- Di Nocera, F., Lorenz, B., & Parasuraman, R. (2005). Consequences of shifting from one level of automation to another: main effects and their stability. Human factors in design, safety, and management, 363-376.

- Eraslan, E., Yildiz, Y., & Annaswamy, A. M. (2020). Shared control between pilots and autopilots: An illustration of a cyberphysical human system. IEEE Control Systems Magazine, 40(6), 77-97.

- Feigh, K. M., Dorneich, M. C., & Hayes, C. C. (2012). Toward a characterization of adaptive systems: A framework for researchers and system designers. Human factors, 54(6), 1008-1024.

- Fereidunian, A., Lucas, C., Lesani, H., Lehtonen, M., Nordman, M. (2007). Challenges in implementation of human-automation interaction models. 2007 Mediterranean Conference on Control & Automation.

- Frohm, J., Lindström, V., Stahre, J., & Winroth, M. (2008). Levels of automation in manufacturing. Ergonomia-an International journal of ergonomics and human factors, 30(3).

- Gregoriades, A., & Sutcliffe, A. G. (2006). Automated assistance for human factors analysis in complex systems. Ergonomics, 49(12-13), 1265-1287.

- Hancock, P.A. & Chignell, M.H. (1993). Adaptive Function Allocation by Intelligent Interfaces. Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces.

- Hardman, N. S. (2009). An empirical methodology for engineering human systems integration. Air Force Institute of Technology.

- Hardman, N., & Colombi, J. (2012). An empirical methodology for human integration in the SE technical processes. Systems Engineering, 15(2), 172-190.

- Harris, W. C., Hancock, P. A., & Arthur, E. J. (1993). The effect of taskload projection on automation use, performance, and workload. The Adaptive Function allocation for Intelligent Cockpits.

- Hilburn, B., Molloy, R., Wong, D., & Parasuraman, R. (1993). Operator versus computer control of adaptive automation. Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Aviation Psychology.

- Hoc, J. M., & Chauvin, C. (2011). Cooperative implications of the allocation of functions to humans and machines. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Hollnagel, E. (1997). Control versus dependence: Striking the balance in function allocation. In HCI (2) (pp. 243-246).

- IJtsma, M., Ma, L. M., Pritchett, A. R., & Feigh, K. M. (2019). Computational methodology for the allocation of work and interaction in human-robot teams. Journal of Cognitive Engineering and Decision Making, 13(4), 221-241.

- Ijtsma, M., Ma, L.M., Pritchett, A.R., & Feigh, K.M. (2017). Work dynamics of task work and teamwork in function allocation for manned spaceflight operations. 19th International Symposium on aviation psychology.

- Inagaki, T. (2000). Situation-Adaptive Autonomy Dynamic Trading of Authority between Human and Automation. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting.

- Inagaki, T. (2003). Adaptive automation: design of authority for system safety. IFAC Proceedings Volumes, 36(14), 13-22.

- Inagaki, T. (2003). Adaptive automation: Sharing and trading of control. In E. Hollnagel (Ed.), Handbook of cognitive task design (pp. 147–169). CRC Press.

- Janssen, C. P., Donker, S. F., Brumby, D. P., & Kun, A. L. (2019). History and future of human-automation interaction. International journal of human-computer studies, 131, 99-107.

- Jiang, X., Kaewkuekool, S., Khasawneh, M.T., Bowling, S.R., Gramopadhye, A.K., & Melloy, B.J. (2003). Communication between Humans and Machines in a Hybrid Inspection System. IIE Annual Conference. Proceedings.

- Johnson, M., Bradshaw, J. M., & Feltovich, P. J. (2018). Tomorrow’s human–machine design tools: From levels of automation to interdependencies. Journal of Cognitive Engineering and Decision Making, 12(1), 77-82.

- Johnson, P., Harrison, M., & Wright, P. (2001). An evaluation of two function allocation methods. The Second International Conference on Human Interfaces in Control Rooms, Cockpits and Command Centres.

- Jung, C. H., Kim, J. T., & Kwon, K. C. (1997). An integrated approach for integrated intelligent instrumentation and control system. (No. IAEA-TECDOC-952). International Atomic Energy Agency.

- Kaber, D. B., & Endsley, M. R. (1997). The Combined Effect of Level of Automation and Adaptive Automation on Human Performance with Complex, Dynamic Control Systems. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting.

- Kaber, D. B., & Riley, J. M. (1999). Adaptive automation of a dynamic control task based on secondary task workload measurement. International journal of cognitive ergonomics, 3(3), 169-187.

- Kaber, D. B., Onal, E., & Endsley, M. R. (2000). Design of automation for telerobots and the effect on performance, operator situation awareness, and subjective workload. Human factors and ergonomics in manufacturing & service industries, 10(4), 409-430.

- Kaber, D. B., Riley, J. M., Tan, K. W., & Endsley, M. R. (2001). On the design of adaptive automation for complex systems. International Journal of Cognitive Ergonomics, 5(1), 37-57.

- Kaber, D. B., Segall, N., Green, R. S., Entzian, K., & Junginger, S. (2006). Using multiple cognitive task analysis methods for supervisory control interface design in high-throughput biological screening processes. Cognition, technology & work, 8(4), 237-252.

- Kaber, D.B. (2013). Adaptive automation. In J.D. Lee and A. Kirlik (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Cognitive Engineering (pp. 865-872). Oxford University Press.

- Kidwell, B., Calhoun, G.L., Ruff, H.A., & Parasuraman, R. (2012). Adaptable and Adaptive Automation for Supervisory Control of Multiple Autonomous Vehicles. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting

- Kim, S.Y., Feigh, K., Lee, S.M., & Johnson, E. (2009). A Task Decomposition Method for Function Allocation. AIAA Infotech@ Aerospace Conference and AIAA Unmanned… Unlimited Conference.

- Klein, G., Feltovich, P. J., Bradshaw, J. M., & Woods, D. D. (2005). Common ground and coordination in joint activity. Organizational simulation, 53, 139-184.

- Knee, H. E., & Schryver, J. C. (1989). Operator role definition and human system integration (No. CONF-890555-8). Oak Ridge National Lab.(ORNL), Oak Ridge, TN (United States).

- Knisely, B. M., & Vaughn-Cooke, M. (2022). Accessibility Versus Feasibility: Optimizing Function Allocation for Accommodation of Heterogeneous Populations. Journal of Mechanical Design, 144(3).

- Kovesdi, C. R. (2022). Addressing function allocation for the digital transformation of existing nuclear power plants. Human Factors in Energy: Oil, Gas, Nuclear and Electric Power, 54.

- Kovesdi, C. R., Spangler, R. M., Mohon, J. D., & Murray, P. (2024). Development of human and technology integration guidance for work optimization and effective use of information (No. INL/RPT-24-77684-Rev000). Idaho National Laboratory (INL), Idaho Falls, ID (United States).

- Lee, J. D., & Seppelt, B. D. (2009). Human factors in automation design. In S.Y. Nof (Ed.), Springer handbook of automation (pp. 417-436). Springer.

- Li, H., Wickens, C. D., Sarter, N., & Sebok, A. (2014). Stages and levels of automation in support of space teleoperations. Human factors, 56(6), 1050-1061.

- Liu, J., Gardi, A., Ramasamy, S., Lim, Y., & Sabatini, R. (2016). Cognitive pilot-aircraft interface for single-pilot operations. Knowledge-based systems, 112, 37-53.

- Lorenz, B., Di Nocera, F., Rottger, S., & Parasuraman, R. (2001). The Effects of Level of Automation on the Out-of-the-Loop Unfamiliarity in a Complex Dynamic Fault-Management Task during Simulated Spaceflight Operations. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting.

- Malasky, J. S. (2005). Human machine collaborative decision making in a complex optimization system (Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology).

- McGuire, J. C., Zich, J. A., Goins, R. T., Erickson, J. B., Dwyer, J. P., Cody, W. J., & Rouse, W. B. (1991). An exploration of function analysis and function allocation in the commercial flight domain (No. NAS 1.26: 4374). NASA.

- Merat, N & Louw, T. (2020). Allocation of Function to Humans and Automation and the Transfer of Control. In D.L. Fisher, W.J. Horrey, J.D. Lee, and M.A. Regan (Eds.), Handbook of Human Factors for Automated, Connected, and Intelligent Vehicles (pp. 153-171). CRC Press.

- Milewski, A. E., & Lewis, S. H. (1997). Delegating to software agents. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 46(4), 485-500.

- Mital, A., Motorwala, A., Kulkarni, M., Sinclair, M., & Siemieniuch, C. (1994). Allocation of functions to human and machines in a manufacturing environment: Part I—Guidelines for the practitioner. International journal of industrial ergonomics, 14(1-2), 3-29.

- Mital, A., Motorwala, A., Kulkarni, M., Sinclair, M., & Siemieniuch, C. (1994). Allocation of functions to humans and machines in a manufacturing environment: Part II—The scientific basis (knowledge base) for the guide. International journal of industrial ergonomics, 14(1-2), 33-49.

- Morrison, J.G., Gluckman, J.P., & Deaton, J.E. (1991). Adaptive Function Allocation for Intelligent Cockpits. (Report No. NADC-91028-60). Office of Naval Technology.

- Mouloua, M., Parasuraman, R., & Molloy, R. (1993). Monitoring Automation Failures Effects of Single and Multi-Adaptive Function Allocation. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting.

- Naghiyev, A. Mount, J. Rice, A., & Sayce, C. (2020). Allocation of Function Method to support future nuclear reactor plant design. Contemporary Ergonomics and Human Factors 2020.

- Neerincx, M. A. (1995). Harmonizing tasks to human knowledge and capacities. [Thesis fully internal (DIV), University of Groningen].

- Older, M. T., Waterson, P. E., & Clegg, C. W. (1997). A critical assessment of task allocation methods and their applicability. Ergonomics, 40(2), 151-171.

- Papantonopoulos, S., & Salvendy, G. (2008). Analytic Cognitive Task Allocation: a decision model for cognitive task allocation. Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science, 9(2), 155-185.

- Parasuraman, R., Mouloua, M., Molloy, R., & Hilburn, B. (1993). Adaptive Function Allocation Reduces Performance Cost of Static Automation. 7th International Symposium on Aviation Psychology.

- Parasuraman, R., Sheridan, T. B., & Wickens, C. D. (2000). A model for types and levels of human interaction with automation. IEEE Transactions on systems, man, and cybernetics-Part A: Systems and Humans, 30(3), 286-297.

- Pattipati, K. R., Kleinman, D. L., & Ephrath, A. R. (2012). A dynamic decision model of human task selection performance. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, 13(2), 145-166.

- Prevot, T., Homola, J. R., Martin, L. H., Mercer, J. S., & Cabrall, C. D. (2012). Toward automated air traffic control—investigating a fundamental paradigm shift in human/systems interaction. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 28(2), 77-98.

- Prinzel, L. J., Freeman, F. G., Scerbo, M. W., Mikulka, P. J., & Pope, A. T. (2000). A closed-loop system for examining psychophysiological measures for adaptive task allocation. The International journal of aviation psychology, 10(4), 393-410.

- Pritchett, A. R., Kim, S. Y., & Feigh, K. M. (2014). Measuring human-automation function allocation. Journal of Cognitive Engineering and Decision Making, 8(1), 52-77.

- Pritchett, A. R., Kim, S. Y., & Feigh, K. M. (2014). Modeling human–automation function allocation. Journal of cognitive engineering and decision making, 8(1), 33-51.

- Pritchett, A.R. & Bhattacharyya, R.P. (2016). Modeling the monitoring inherent within aviation function allocations . Proceedings of the International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction in Aerospace.

- Proud, R. W., Hart, J. J., & Mrozinski, R. B. (2003). Methods for determining the level of autonomy to design into a human spaceflight vehicle: a function specific approach. (No. ADA515467). Defense Technical Information Center

- Pupa, A., Landi, C. T., Bertolani, M., & Secchi, C. (2021). A dynamic architecture for task assignment and scheduling for collaborative robotic cells. In International workshop on human-friendly robotics.

- Ranz, F., Hummel, V., & Sihn, W. (2017). Capability-based task allocation in human-robot collaboration. Procedia manufacturing, 9, 182-189.

- Rauffet,P., Chauvin, C., Morel, G., & Berruet, P. (2015). Designing sociotechnical systems: a CWA-based method for dynamic function allocation. Proceedings of the European Conference on Cognitive Ergonomics 2015.

- Rencken, W. D., & Durrant-Whyte, H. F. (1993). A quantitative model for adaptive task allocation in human-computer interfaces. IEEE transactions on systems, man, and cybernetics, 23(4), 1072-1090.

- Rognin, L., Salembier, P., & Zouinar, M. (2000). Cooperation, reliability of socio-technical systems and allocation of function. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 52(2), 357-379.

- Roth, E. M., Hanson, M. L., Hopkins, C., Mancuso, V., & Zacharias, G. L. (2004). Human in the Loop Evaluation of a Mixed-Initiative System for Planning and Control of Multiple UAV Teams. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting.

- Rouse, W. B. (1988). Adaptive aiding for human/computer control. Human factors, 30(4), 431-443.

- Rungta, N., Brat, G., Clancey, W.J., Linde, C., Raimondi, F., Seah, C., & Shafto, M. (2013). Aviation safety: modeling and analyzing complex interactions between humans and automated systems . Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Application and Theory of Automation in Command and Control Systems.

- S. Shoval, Y. Koren & J. Borenstein (1993). Optimal task allocation in task-agent-control state space. Proceedings of IEEE Systems Man and Cybernetics Conference - SMC.

- Sakakeeny, J., Idris, H. R., Jack, D., & Bulusu, V. (2022). A framework for dynamic architecture and functional allocations for increasing airspace autonomy. AIAA AVIATION 2022 Forum.

- Salunkhe, O., Stahre, J., Romero, D., Li, D., & Johansson, B. (2023). Specifying task allocation in automotive wire harness assembly stations for Human-Robot Collaboration. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 184, 109572.

- Sanchez, J. (2009). Conceptual model of human-automation interaction. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting.

- Scallen, S. F. (1997). Performance and workload effects for full versus partial automation in a high-fidelity multi-task system. [Thesis, University of Minnesota].

- Scholtz, J. (2003). Theory and evaluation of human robot interactions. 36th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.

- Schurr, N. Picciano, P., & Marecki, J. (2010). Function allocation for NextGen airspace via agents. Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems: Industry Track.

- Schutte, P. (1999). Complementation: An alternative to automation. Journal of Information Technology Impact, 1(3), 113-118.

- Schutte, P., Goodrich, K., & Williams, R. (2016). Synergistic allocation of flight expertise on the flight deck (SAFEdeck): A design concept to combat mode confusion, complacency, and skill loss in the flight deck. In Advances in Human Aspects of Transportation, 899-911.

- Sebok, A., & Wickens, C. D. (2017). Implementing lumberjacks and black swans into model-based tools to support human–automation interaction. Human factors, 59(2), 189-203.

- Seger, J. (2019). Coagency of humans and artificial intelligence in sea rescue environments: A closer look at where artificial intelligence can help humans maintain and improve situational awareness in search and rescue operations. [Thesis, Linkoping University].

- Sherry, R. R., & Ritter, F. E. (2002). Dynamic task allocation: issues for implementing adaptive intelligent automation. Report no. ACS, 2.

- Skitka, L. J., Mosier, K. L., & Burdick, M. (1999). Does automation bias decision-making?. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 51(5), 991-1006.

- Strenzke, R. (2019). Cooperation of Human and Artificial Intelligence on the Planning and Execution of Manned-Unmanned Teaming Missions in the Military Helicopter Domain: Concept, Requirements, Design, Validation (Doctoral dissertation, Dissertation, Neubiberg, Universität der Bundeswehr München, 2019).

- Taylor, R.M. (2002). Capability, cognition and autonomy. Proceedings of RTO Human Factors and Medicine Panel (HFM) Symposium.

- Terveen, L. G. (1995). Overview of human-computer collaboration. Knowledge-Based Systems, 8(2-3), 67-81.

- van Wezel, W., Cegarra, J., & Hoc, J. M. (2010). Allocating functions to human and algorithm in scheduling. In Behavioral operations in planning and scheduling (pp. 339-370). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Vanderhaegen, F. (1999). Cooperative system organization and task allocation: illustration of task allocation in air traffic control. Le Travail Humain, 197-222.

- Wang, C., Wen, X., Niu, Y., Wu, L., Yin, D., & Li, J. (2018, November). Dynamic task allocation for heterogeneous manned-unmanned aerial vehicle teamwork. In 2018 Chinese Automation Congress (CAC) (pp. 3345-3349). IEEE.

- Waterson, P. E., Older Gray, M. T., & Clegg, C. W. (2002). A sociotechnical method for designing work systems. Human factors, 44(3), 376-391.

- Wei, Z. G., Macwan, A. P., & Wieringa, P. A. (1998). A quantitative measure for degree of automation and its relation to system performance and mental load. Human Factors, 40(2), 277-295.

- Wen, H. Y. (2011). Human-automation task allocation in lunar landing: simulation and experiments (Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology).

- Woods, D. D. (1985). Cognitive technologies: The design of joint human-machine cognitive systems. AI magazine, 6(4), 86-86.

- Wright, M. C., & Kaber, D. B. (2005). Effects of automation of information-processing functions on teamwork. Human Factors, 47(1), 50-66.

- Yang, F. (2022). A function allocation framework for the automation of railway maintenance practices (Doctoral dissertation, University of Birmingham).

- Yang, F., Steward, E., & Roberts, C. (2018). A Framework for Railway Maintenance Function Allocation. 2018 International Conference on Intelligent Rail Transportation (ICIRT).

- Zhang, G., Lei, X., Niu, Y., & Zhang, D. (2015). Architecture design and performance analysis of supervisory control system of multiple UAVs. Defense Science Journal, 65(2), 93.

- Zhe, Z., Yifeng, N., & Lincheng, S. (2020). Adaptive level of autonomy for human-UAVs collaborative surveillance using situated fuzzy cognitive maps. Chinese Journal of Aeronautics, 33(11), 2835-2850.

References

- Pulliam, R. Price, H., Bongarra, J., Sawyer, C and Kisner, R. A Methodology for Allocating Nuclear Power Plant Control Nuclear to Human or Automatic Control NUREG/CR-3331, U.S. NRC, Washington D.C., United States, ADAMS Accession No. ML20024E954. 1983.

- Fitts, P. M. Human engineering for an effective air-navigation and traffic-control system. National Research Council.1951.

- Price, H. E., Maisano, R. E., and Van Cott, H. P. The allocation of functions in man-machine systems: A perspective and literature review NUREG-CR-2623. Oak Ridge, TN: Oak Ridge National Laboratories. 1982.

- O’Hara, J. Higgins, J., Fleger, S. and Pieringer, P. Human Factors Engineering Program Review Model (NUREG-0711, Revision 3), U.S. NRC, Washington DC, United States, U.S. NRC Agencywide Document Access and Management System (ADAMS) Accession No. ML12324A013. 2012.

- International Atomic Energy Agency. Safety related terms for advanced nuclear plants (IAEA-TECDOC-626). International Atomic Energy Agency. 1991.

- Green, B., Buchanan, T., & D’Agostino, A. Assessing independence from human performance: Considerations for functional requirements analysis and function allocation. In Proceedings of the 14th Nuclear Plant Instrumentation, Control & Human-Machine Interface Technologies (NPIC&HMIT): Chicago, IL, 2025, 228-235. U.S.

- Morrow, S., Xing, J., & Hughes Green, N. Revisiting Functional Requirements Analysis and Function Allocation to Support Automation Decisions in Advanced Reactor Designs. In Proceedings of the 14th Nuclear Plant Instrumentation, Control & Human-Machine Interface Technologies (NPIC&HMIT): Chicago, IL, 2025, 228-235. U.S.

- O’Hara, J., & Higgins, J. Adaptive automation: Current status and challenges (RIL 2020-05). U.S. NRC, Washington DC, United States, U.S. NRC Agencywide Document Access and Management System (ADAMS) Accession No. ML20176A199. 2020.

- Higgins, J., O’Hara, J., & Hughes, N. Safety evaluations of adaptive automation: Suitability of existing review guidance (RIL 2020-06). U.S. NRC, Washington DC, United States, U.S. NRC Agencywide Document Access and Management System (ADAMS) Accession No. ML22006A020.2022.

- O’Hara, J., & Fleger, S. Human-system interface design review guidelines (NUREG-0700, Rev. 3). U.S. NRC, Washington DC, United States, U.S. NRC Agencywide Document Access and Management System (ADAMS) Accession No. ML20206A436. 2020.

- Elmagarmid, A. K., Fedorowicz, Z., Hammady, H., Ilyas, I. F., Khabsa, M., & Ouzzani, M. Rayyan: a systematic reviews web app for exploring and filtering searches for eligible studies for Cochrane Reviews. Available-online: https://www.rayyan.ai/ (accessed 2024-2025).

- Webster, J., & Watson, R. T. Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: Writing a literature review. MIS quarterly 2002, xiii-xxiii.

- Sheridan, T.B. & Verplank, W.L. Human and computer control of undersea teleoperators. DTIC N00014-77-C0256. 1978.

- Parasuraman, R., Sheridan, T. B., & Wickens, C. D. A model for types and levels of human interaction with automation. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, 2000 30(3), 286-297. [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, B. S., Nyre-Yu, M., & Hill, J. R. Advances in human-automation collaboration, coordination and dynamic function allocation. Transdisciplinary Engineering 2019, 348-359.

- Pupa, A., Landi, C. T., Bertolani, M., & Secchi, C. A dynamic architecture for task assignment and scheduling for collaborative robotic cells. In International workshop on human-friendly robotics. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021, 74-88.

- Wang, G., Zhou, S., Zhang, S., Niu, Z., & Shen, X. SFC-based service provisioning for reconfigurable space-air-ground integrated networks. IEEE Selected Areas in Communications, 2020 38(7), 1478-1489. [CrossRef]

- Eraslan, E., Yildiz, Y., & Annaswamy, A. M. Shared control between pilots and autopilots: An illustration of a cyberphysical human system. IEEE Control Systems,2020 40(6), 77-97. [CrossRef]

- Sebok, A., & Wickens, C. D. Implementing lumberjacks and black swans into model-based tools to support human–automation interaction. Human Factors, 2017 59(2), 189-203. [CrossRef]

- Hilburn, B., Molloy, R., Wong, D., & Parasuraman, R. Operator versus computer control of adaptive automation. The adaptive function allocation for intelligent cockpits (AFAIC) program: Interim research and guidelines for the application of adaptive automation. DTIC, 1993, 31-36.

- Older, M. T., Waterson, P. E., & Clegg, C. W. A critical assessment of task allocation methods and their applicability. Ergonomics, 1997 40(2), 151-171. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F. (2022). A function allocation framework for the automation of railway maintenance practices. Doctoral dissertation, University of Birmingham. 2022 (May 2025).

- Waterson, P. E., Older Gray, M. T., & Clegg, C. W. A sociotechnical method for designing work systems. Human Factors, 2002 44(3), 376-391. [CrossRef]

- Rencken, W. D., & Durrant-Whyte, H. F. (1993). A quantitative model for adaptive task allocation in human-computer interfaces. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, 1993 23(4), 1072-1090. [CrossRef]

- Hancock, P.A. & Chignell, M.H. (1993). Adaptive Function Allocation by Intelligent Interfaces. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces. 1993.

- Morrison, J.G., Gluckman, J.P., & Deaton, J.E. Adaptive Function Allocation for Intelligent Cockpits. (Report No. NADC-91028-60). Office of Naval Technology. 1991.

- Parasuraman, R., Mouloua, M., Molloy, R., & Hilburn, B. Adaptive Function Allocation Reduces Performance Cost of Static Automation. 7th International Symposium on Aviation Psychology (1993).

- Clamann, M. P., & Kaber, D. B. Authority in adaptive automation applied to various stages of human-machine system information processing. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 47, (3). Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications (October 2003). [CrossRef]

- Feigh, K. M., Dorneich, M. C., & Hayes, C. C. Toward a characterization of adaptive systems: A framework for researchers and system designers. Human Factors, 2012 54(6), 1008-1024.

- Li, H., Wickens, C. D., Sarter, N., & Sebok, A. Stages and levels of automation in support of space teleoperations. Human Factors, 2014, 56(6), 1050-1061. [CrossRef]

- Boy, G.A. Cognitive function analysis for human-centered automation of safety-critical systems. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1998.

- Schwaninger, A. (2009, October). Why do airport security screeners sometimes fail in covert tests?. In 43rd Annual 2009 International Carnahan Conference on Security Technology, pp. 41-45, IEEE, (October, 2009).

- Hawley, J. K., & Mares, A. L. Developing effective adaptive missile crews and command and control teams for air and missile defense systems (No. ARLSR149). U.S. Army Research Laboratory, Washington D.C. 2007.

- Lew, R., Ulrich, T. A., Boring, R. L., & Werner, S. Applications of the rancor microworld nuclear power plant simulator. In 2017 Resilience Week (RWS) (pp. 143-149). IEEE, 2017.

- Park, J., Yang, T., Boring, R. L., Ulrich, T. A., & Kim, J. Analysis of human performance differences between students and operators when using the Rancor Microworld simulator. Annals of Nuclear Energy, 2023 180, 109502. [CrossRef]

- Park, J., Ulrich, T. A., Boring PhD, R. L., Kim, J., Lee, S., & Park, B. An empirical study on the use of the rancor microworld simulator to support full-scope data collection (No. INL/CON-20-57751-Rev000). Idaho National Laboratory (INL), Idaho Falls, ID (United States). 2020.

- Ulrich, T. A., Boring PhD, R. L., & Lew, R. Rancor-HUNTER: A Virtual Plant and Operator Environment for Predicting Human Performance (No. INL/MIS-24-76401-Rev001). Idaho National Laboratory (INL), Idaho Falls, ID (United States). 2024.

- Boring, R. L., Ulrich, T. A., & Lew, R. (2023). The Procedure Performance Predictor (P3): Application of the HUNTER Dynamic Human Reliability Analysis Software to Inform the Development of New Procedures. In Proceedings of the European Safety & Reliability Conference. 2023.

- Rasmussen, J. Skills, rules, and knowledge; signals, signs, and symbols, and other distinctions in human performance models. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics,1983, (3), 257-266. [CrossRef]

- Schreck, J., Matthews, G., Lin, J., Mondesire, S., Metcalf, D., Dickerson, K., & Grasso, J. Levels of Automation for a Computer-Based Procedure for Simulated Nuclear Power Plant Operation: Impacts on Workload and Trust. Safety, 2025, 11(1), 22. [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, T. A., Lew, R., Kim, J., Jurski, D., Gideon, O., Dickerson, K., ... & Boring, R. L A Tale of Two Simulators—A Comparative Human-in-the-Loop Nuclear Power Plant Operations Study on Thermal Power Dispatch for Hydrogen Production. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting (Vol. 68, No. 1, pp. 791-795). Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications (September, 2024). [CrossRef]

- Lin, J., Matthews, G., Schreck, J., Dickerson, K., & Green, N. H. Evolution of Workload Demands of the Control Room with Plant Technology. Human Factors and Simulation, 2023, 57.

- Kochunas, B., & Huan, X. Digital twin concepts with uncertainty for nuclear power applications. Energies, 2021, 14(14), 4235. [CrossRef]

- Wilsdon, K., Hansel, J., Kunz, M. R., & Browning, J. Autonomous control of heat pipes through digital twins: Application to fission batteries. Progress in Nuclear Energy, 2023, 163, 104813. [CrossRef]

- Wen, H. Y. (2011). Human-automation task allocation in lunar landing: simulation and experiments. Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (May, 2025).

- Jiang, X., Kaewkuekool, S., Khasawneh, M. T., Bowling, S. R., Gramopadhye, A. K., & Melloy, B. J. Communication between Humans and Machines in a Hybrid Inspection System. In IISE Annual Conference. In Proceedings (p. 1). Institute of Industrial and Systems Engineers (IISE). 2003.

- Prinzel, L. J., Freeman, F. G., Scerbo, M. W., Mikulka, P. J., & Pope, A. A closed-loop system for examining psychophysiological measures for adaptive task allocation. The International Journal of Aviation Psychology, 2000 10(4), 393-410. [CrossRef]

- Wright, M. C., & Kaber, D. B. Effects of automation of information-processing functions on teamwork. Human Factors, 2005, 47(1), 50-66. [CrossRef]

- Endsley, M. R. (2017). From here to autonomy: lessons learned from human–automation research. Human Factors, 2017, 59(1), 5-27.

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).