1. Introduction

The Standard Model (SM) [

1,

2] of particle physics has been remarkably successful in describing the fundamental particles and their interactions, including the mechanism by which they acquire mass [

3,

4]. It has been well tested by several collider experiments. Despite its success, the SM is widely recognized as an incomplete theory because there are still some phenomena that can not be explained by SM. For instance, it does not explain the origin of tiny neutrino masses [

5] or the nature of dark matter (DM) [

6]. The former has been established by the discovery of neutrino oscillation [

7], which imply that neutrinos have masses below the eV scale. The latter has been indicated by a variety of evidence, such as the galactic rotation curve [

8], galaxy cluster, and the large-scale structure of the universe [

9]. These issues strongly suggest the need for physics beyond the SM (BSM). Extensions of the SM are therefore required to solve these outstanding issues, including the missing description of DM [

6] and neutrino oscillation [

5,

7].

DM accounts for about

of the total matter density of the Universe. It does not interact via the strong or electromagnetic interaction, and its presence so far can be inferred only through gravitational effect. Therefore, the nature of DM remains unknown. Experimental information on DM is needed to explain recent astrophysical observations, including the velocity profiles of galactic rotation curve [

8] and the fundamental characteristics of our Universe [

9]. A dynamical mechanism, baryogenesis, has been recently proposed for GeV-scale DM carrying baryon number, offering an attractive framework for simultaneously addressing the sources of DM and the matter–antimatter asymmetry of the Universe [

10]. Additionally, the presence of DM particles may enhance the branching fraction of flavor-changing neutral-current (FCNC) processes [

11], which are highly suppressed by the Glashow–Iliopoulos–Maiani mechanism [

2], making them accessible to the current generation of collider experiments.

An extension of the SM is needed to accommodate the DM. One of the most popular scenarios is a dark sector (or “hidden sector”) that arises from several well-motivated theories, including string-inspired models [

12], supersymmetry (SUSY) [

13], and extensions featuring extra

symmetries [

14]. In these scenarios, dark sector fields interact only feebly with the SM particles, often through renormalizable operators or high-dimension Wilson coefficient operators [

15]. According to this hidden sector, the DM may couplue to the SM particles via these portals: vector, axion, Higgs, and neutrino [

17]. The corresponding portals predict new-physics particles that are categorized as dark photon, axion-like particle, light Higgs boson, and sterile neutrinos. If the masses of these particles lie in the MeV–GeV range, they can be probed at high-intensity

collider experiments, such as BaBar [

18], Belle/Belle II [

16], and BESIII [

19]. Complementary efforts are ongoing and planned at future colliders, including the Circular Electron–Positron Collider (CEPC) [

20] and the Super Tau–Charm Factory (STCF) [

21] in China, which promise to substantially extend the current sensitivity to rare and invisible decays.

This report reviews recent progress in searches for new physics at collider experiments, with an emphasis on portal-based scenarios. It outlines the theoretical motivations for these models, summarizes the experimental results from both existing and planned experiments, and discusses future prospects. These studies represent a cornerstone of the ongoing effort to uncover the nature of dark matter and other phenomena beyond the SM.

2. Vector Portal

The vector portal introduces a new abelian

gauge boson, commonly referred to as a dark photon (

or

) [

22], which shares similarities with the ordinary photon but may possess mass and interact with dark matter particles [

17]. In this framework, dark matter particles can annihilate into a pair of dark photon, which subsequently decay into SM particles, satisfying the constraints of recent astrophysical observations [

9]. Dark photons are broadly categorized into two distinct types: massive dark photon, which arises when the additional

gauge symmetry is spontaneously broken, and massless dark photon, where the symmetry remains unbroken [

23,

24]. Each category exhibits unique phenomenological signatures and is probed through different experimental approaches.

2.1. Massive Dark Photon

The dark photon can acquire mass through a hidden mechanism, such as the Stückelberg mechanism [

25] or a dark Higgs mechanism [

26], where spontaneous symmetry breaking of the

gauge group introduces a dark Higgs boson

. The corresponding Lagrangian for the minimal dark sector is given by [

27]:

where

and

represent the field strength tensors for the SM photon and dark photon, respectively. The parameter

quantifies the kinetic mixing between the SM and dark sector photons, while

denotes the dark photon mass. The dark current

describes interactions with dark sector fermions or scalars, and

includes terms related to mass generation and possible spontaneous symmetry-breaking effects.

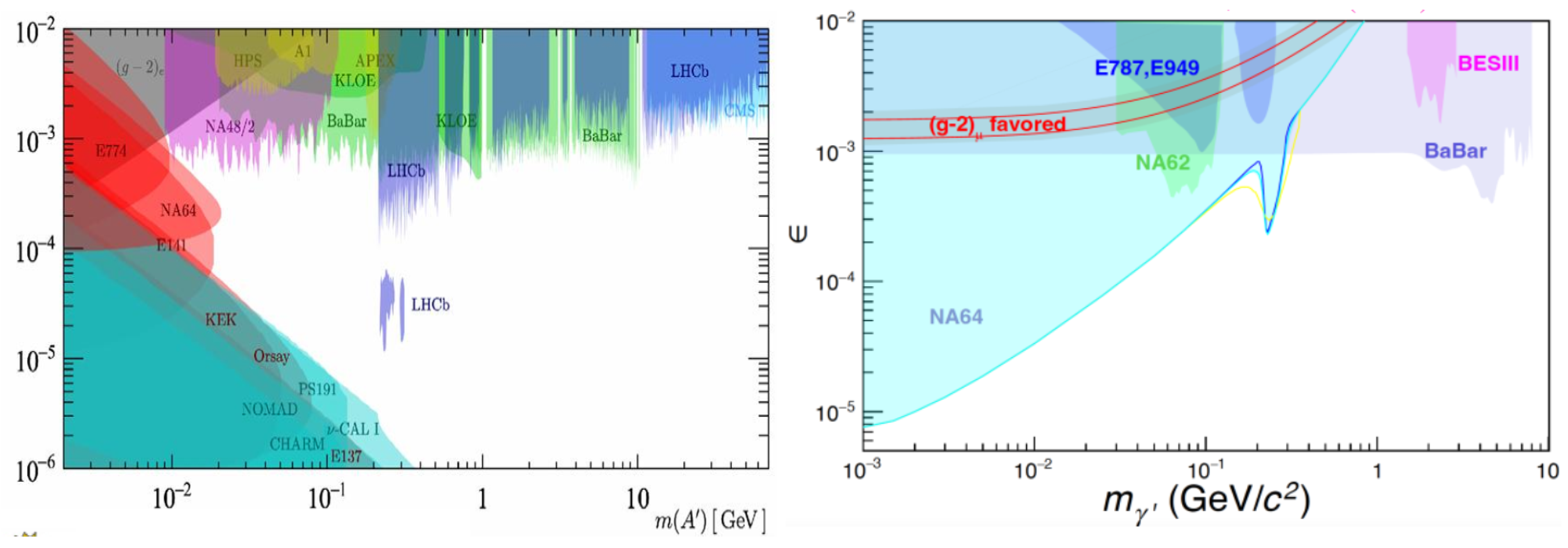

2.1.1. Abelian Dark Photon

The spontaneous breaking of an Abelian

gauge group generates mass for the dark photon

[

22]. The effective coupling strength between the massive dark photon and SM photon is given by

, where

and

represent the fine structure constants of the SM and dark sectors, respectively [

28,

29]. Astrophysical constraints typically restrict the massive dark photon mass to the sub-GeV to few-GeV range [

29,

30]. Constraints on

have been placed on visible

decays by beam-dump [

31], fixed-target [

32,

33],

colliders [

34,

35,

36], rare-meson decay [

36], and LHCb [

38] experiments. The most stringent limits on

, especially below

, mainly come from NA48 experiment in the

range of

MeV, KLOE-2 experiment [

36] in the

mass region, BaBar experiment [

34] in

and LHCb experiment [

38] in the high mass region, as seen in

Figure 1 (left). BESIII has extended these searches to lower mass regions (

) [

35]. For invisibly decaying dark photons, constraints on

appear from kaon decays [

39], missing energy events in electron-nuclues scattering [

40] and

collider experiments [

41,

42]. BaBar’s result [

41] is more stringent in the higher mass region, as seen in

Figure 1 (right).

2.1.2. Non-Abelian Dark Sector

An extended theory featuring a non-Abelian

gauge group introduces four gauge bosons:

(

),

,

, and

[

29]. The mass hierarchy among these particles is unconstrained, allowing for light gauge bosons and potentially a light dark Higgs boson. This scenario enables probing of such a light dark matter particles at low-energy

colliders and fixed-target experiments through signatures including

(mediated by a virtual

) and

, along with a Higgs-strahlung process that may yield missing energy. BaBar has conducted searches for a narrow di-lepton resonance in four-lepton final states using 536 fb

−1 of data. No significant signal events are observed, yielding

CL upper limits on production cross sections:

ab,

ab, and

ab for

masses between 0.24 and 5.3 GeV/

[

43]. Under the assumption of equal

coupling to electrons and muons, a combined upper limit of

ab was established.

2.2. Massless Dark Photon

A massless dark photon (

) can couple to the SM fermions through a higher-dimensional operator. Reference [

44] introduces a dimension-six operator enabling an effective coupling between the dark photon field strength and SM fermions, leading to FCNC processes. Unlike the massive case, this coupling arises from a term proportional to

, where

represents the new-physics scale, rather than through kinetic mixing.

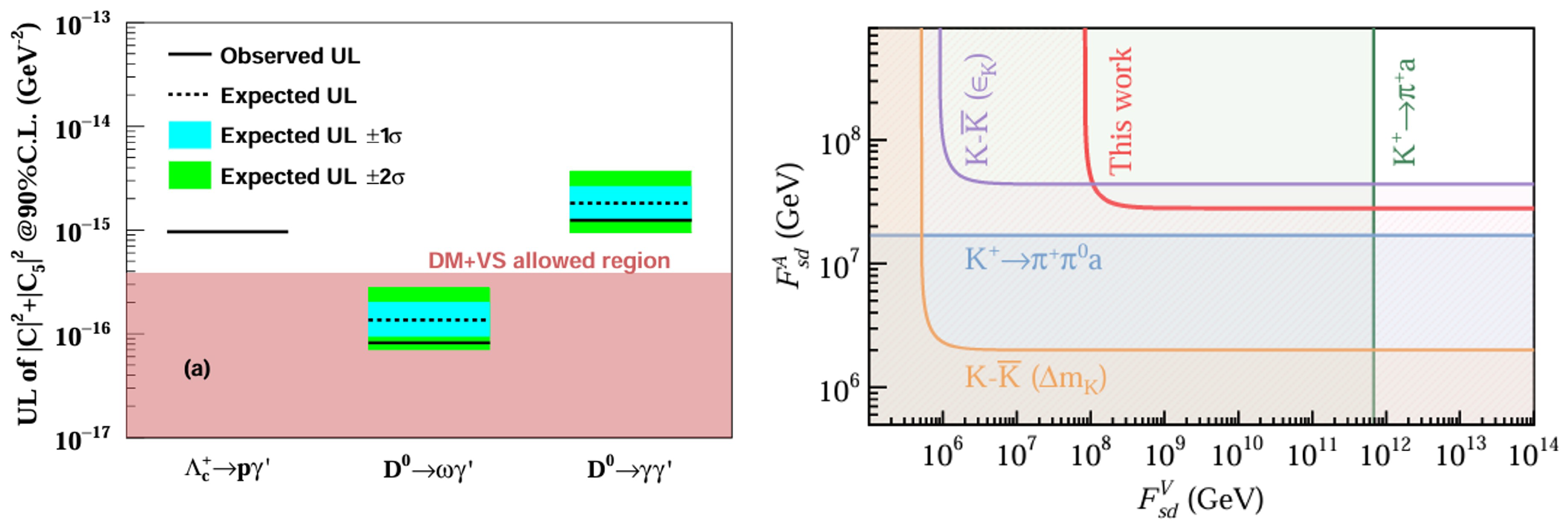

BESIII has recently conducted searches for massless dark photon in the following decay channels:

via

using 10 billion

events [

45].

through

using 4.5 fb

−1 of data at

GeV [

46].

and

using 7.9 fb

−1 of

data [

47].

These analyses employed a double tag technique [

48], where one baryon or meson is reconstructed in its dominant hadronic decay modes while the partner decays to the signal channel of interest. No significant signal events are observed, establishing 90% CL upper limits of

[

45],

[

46],

, and

[

47]. These results improve constraints on the effective coupling parameter to

[

47], reaching regions allowed by DM and vacuum stability considerations and surpassing previous

limits by an order of magnitude (

Figure 2, left). The

limit improves constraints on the axial–vector coupling

beyond bounds from kaon-mixing and CP-violation measurements [

45] (

Figure 2, right).

3. Higgs Portal

In the last decade, both the ATLAS and CMS experiments confirmed the Higgs mechanism [

3], which provides masses to SM particles via spontaneous breaking of electroweak symmetry [

4]. Both experiments have also been able to map out its properties in detail and find consistency with the assumption that the Higgs couples to SM particles proportionally to their mass. Nevertheless, the origin of the majority of mass in the universe remains a mystery, because it is not in the form of known particles but in a completely new form called DM [

6]. If DM is composed of elementary particles, we can hope to detect these particles in the laboratory or infer their properties from astrophysical observations [

9]. A similar Higgs mechanism [

26] may give mass to a dark matter candidate and to the gauge boson mediating its interactions, such as a dark photon. An extended sector beyond the SM may also be required to solve the little hierarchy problem of the SM [

49]. At low-energy

collider experiments, the following scenarios related to BSM Higgs or spin-0 scalar searches are well motivated and explored.

3.1. Light Higgs Boson

A light Higgs boson is predicted by many models beyond the SM, such as the Next-to-Minimal Supersymmetric Standard Model (NMSSM) [

50], which extends the Higgs sector of the SM to include additional Higgs fields. The Higgs sector of the NMSSM contains three

-even, two

-odd, and two charged Higgs bosons. The mass of the lightest

-odd Higgs boson,

, could be smaller than twice the mass of the bottom or charm quark, thus making it accessible via radiative decays of

(

) or

[

51]. The couplings of the Higgs field to up- and down-type quark pairs are proportional to

and

, respectively, where

represents the ratio of the vacuum expectation values of the up- and down-type Higgs doublets. The branching fractions of

and

are predicted to be in the ranges of

–

and

–

, respectively, depending on

,

, and other NMSSM parameters [

52].

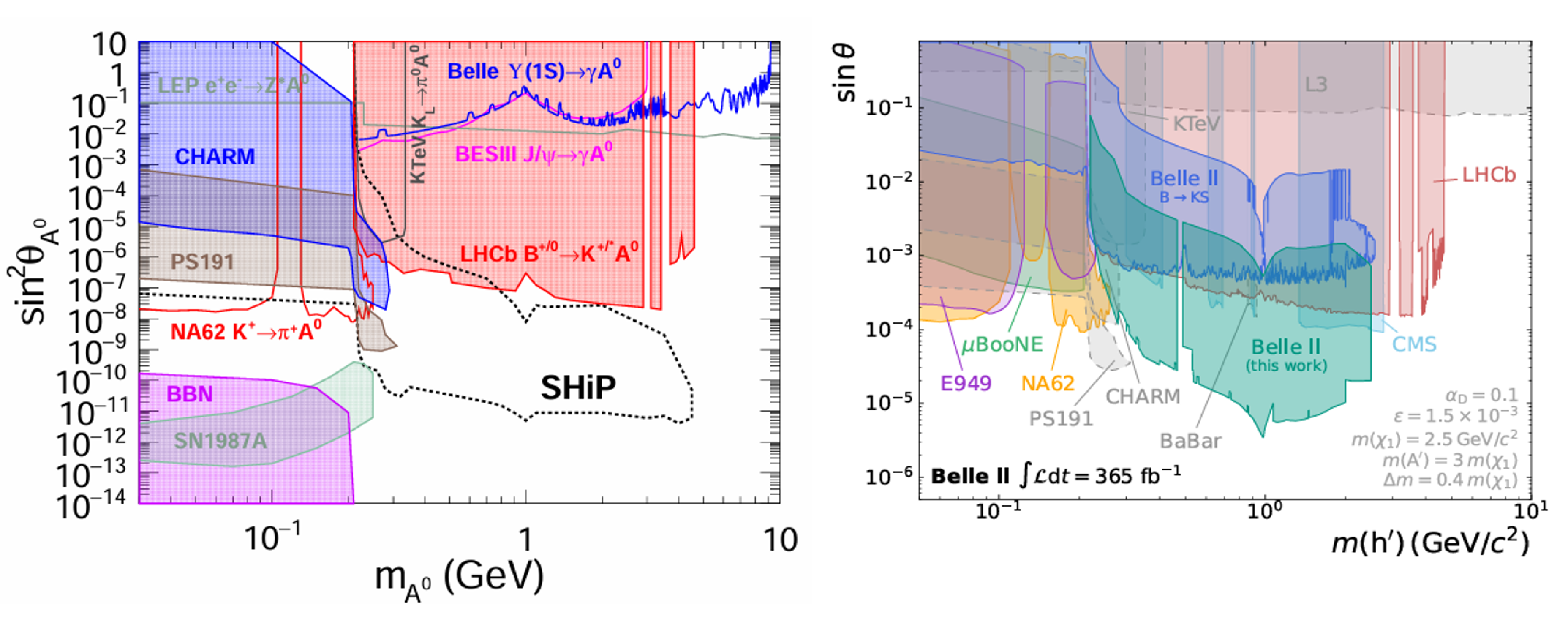

The branching fractions of

are related to the Yukawa coupling of

to down- or up-type quarks

, as described by the formula in Eq. (1) of Ref. [

53]. Searches for a light Higgs boson decaying to various fermion-pair final states in radiative

have been performed by various

B-factory related experiments, such as BaBar [

54] and Belle [

55] experiments. Though these experiments have reported null results, but, their results have placed strong exclusion limits on the effective Yukawa coupling of the Higgs field to bottom-type quark pairs (

). According to Ref. [

56], BaBar’s results for

are much more sensitive than those for hadronic, di-tau, and invisible decays of

. The exclusion limits on

, on the other hand, have been set by BESIII experiment, which has performed searches for

decaying to invisible final states and muon pairs. The BESIII measurement [

53,

57] is comparable to those from BaBar [

54] and Belle [

55] measurements in the low-mass region, as seen in

Figure 3 (left) of exclusion limits on the mixing angle (

) as a function of

mass.

3.2. Dark Higgs Boson

In a minimal model, dark force carriers such as the dark photon acquire their masses via the Higgs mechanism, introducing a dark Higgs boson

to the theory [

26]. The mass hierarchy between

and dark force carriers is not constrained, and the dark Higgs boson could be light as well. Searches for the dark Higgs boson have been performed by BaBar [

58], Belle [

59], and KLOE-2 [

60] experiments via the Higgs-strahlung process

. There are three main cases: (a)

, where

is long-lived and decays into lepton pairs or hadrons; (b)

, where

decays into two dark photons that subsequently decay into lepton pairs; and (c)

, where

. Here

and

are the masses of the dark Higgs and dark photon, respectively. No evidence of dark Higgs production has been found, and

CL upper limits on

have been set as a function of

for various values of

. The upper limits on

range from

to

, depending on

and

[

58,

59,

60].

Inelastic dark matter models that feature two dark matter particles and a massive dark photon can reproduce the observed relic dark matter density without violating cosmological limits [

9]. The mass splitting between the two dark matter particles is induced by a dark Higgs field and its corresponding dark Higgs boson

. Belle II has recently performed a search for the dark Higgs boson produced in association with inelastic dark matter using a 365 fb

−1 data sample [

61]. Belle II uses events with up to two displaced vertices and missing energy, produced in

collisions via

, where

indicates

,

, or

. The search for a signal is performed by looking for a narrow enhancement in the

distribution. The remaining events in data after selection are 0, 8, and 1 for

,

, and

final states, respectively. The

CL upper limits on the mixing angle between the SM Higgs and

, as shown in

Figure 3 (right), as well as on the dimensionless variable

y, are set as functions of

and

, respectively [

61].

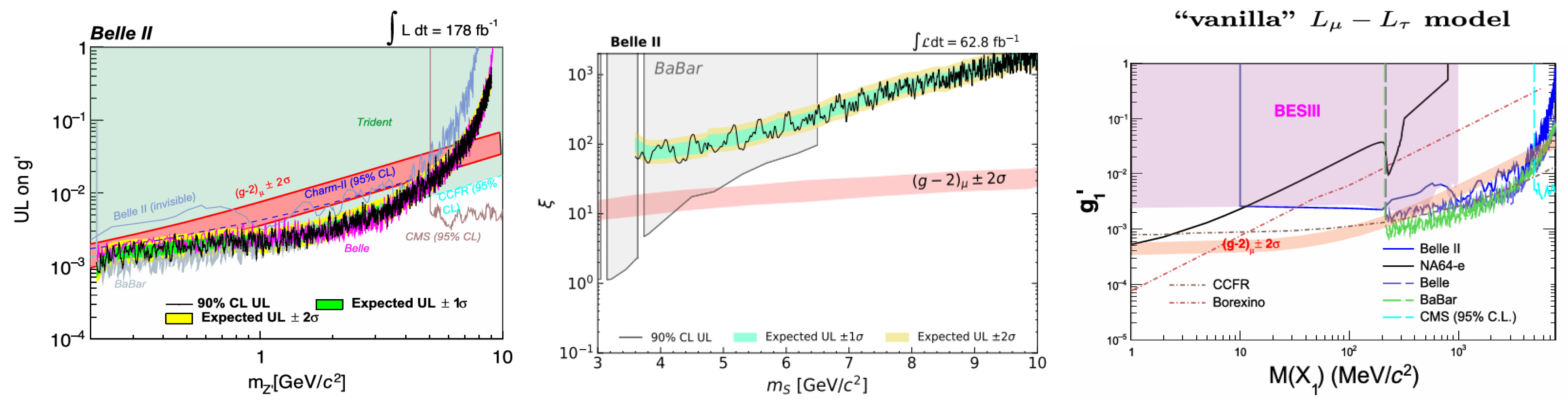

3.2.1. Muon-Philic Scalar or Vector Bosons

A new type of

extension of the SM is desirable to resolve the long-standing muon anomalous magnetic moment [

62], the tensions in flavor observables reported by B-factory experiments [

63], and to explain the dark matter phenomena and the relic abundance of dark matter [

64]. This model gauges the difference between the muon and the

-lepton number through the introduction of new massive vector (

) or leptophilic scalar (

) or pseudocalar bosons [

65]. The

could also mediate the interactions between the SM and the dark sector. They couple exclusively to second- and third-generation leptons (

) with coupling strengths

. Experimentally, the searches for

decaying to a pair of muons have been reported by the BaBar [

66], CMS [

67], and Belle II [

68] experiments. The BaBar [

66] measurement is more stringent in the low-mass region, as seen in

Figure 4 (left).

The leptophilic scalar decaying into electrons and muons is constrained by Belle up to masses of approximately 6.5 GeV/

[

69], and above this, the leptophilic scalar decaying into a

-pair is constrained by Belle II in

events [

70], as seen in

Figure 4 (middle). Searches for a light muon-philic scalar

or vector

have been performed via

with

decaying to invisible final states using 10 billion

events, and reported null results [

71]. The obtained limits are more stringent than the Belle II measurement in the mass range of 200–860 MeV/

[

71], as seen in

Figure 4 (right).

3.3. Search for Dark Baryon

The baryon asymmetry of the Universe (BAU) implies the need for baryogenesis [

10]. Baryogenesis requires the Sakharov conditions [

72]: baryon-number violation, violation of charge conjugation

C and charge-parity

, and a departure from thermal equilibrium. These conditions are, in principle, compatible with the SM, but current measurements show that the SM does not provide sufficient baryogenesis to explain the observed BAU. The similarity between the dark matter and baryonic energy densities,

, suggests a possible connection between their origins, motivating scenarios in which dark matter carries non-zero baryon number [

73,

74]. A baryonic dark sector is further motivated by the long-standing discrepancy between neutron-lifetime measurements in beam and bottle experiments, which could be resolved if the neutron decays into dark-matter states carrying baryon number with a branching fraction of order

[

75].

The

B-mesogenesis mechanism can simultaneously explain both the visible baryon asymmetry and the origin of dark matter [

76]. Dark-sector antibaryons have been searched for in

B-meson decays at the BaBar experiment [

77] and, more recently, in invisible decays of the

baryon [

78] as well as

oscillation [

79] at BESIII. Complementary to these searches, hyperon decays offer an additional opportunity to probe baryonic dark matter through final states containing dark baryons, which would manifest as missing energy in the detector.

More recently, a search for baryogenesis and dark matter in

was performed using

of data collected at the

resonance by the BaBar experiment [

77]. The signal was inferred from the distributions of the beam-constrained mass and the invariant mass of the

system. No evidence for dark-baryon production

was found, and upper limits on

were set at the

confidence level as a function of the

mass in the range

.

A search for a dark baryon

in the two-body decay

has recently been performed using approximately

events from

decays, based on the

events collected by the BESIII detector [

80]. In this process, the

is studied by tagging the recoil

, reconstructed via

. The dark baryon

is treated as an invisible particle, and the search is performed for assumed masses of 1.07, 1.10,

, 1.13, and 1.16 GeV/

, where

is the

-baryon mass. No significant signal is observed, and

(

) CL upper limits on

are set. The corresponding

CL limits on the left- and right-handed effective operators, parameterized by the Wilson coefficients

and

, are found to be

and

, which are more stringent than previous constraints from LHC searches for colored mediators.

4. Axion Portal

An axion is a pseudoscalar Goldstone boson originally introduced through the spontaneous breaking of the Peccei-Quinn symmetry to solve the strong CP problem in QCD [

81]. Many models beyond the SM also predict axion-like particles (ALPs) [

82,

83]. The spin-parity of these ALPs is the same as that of the QCD axion, but they have arbitrary masses and couplings to SM particles. ALPs are also considered candidates for cold DM and can act as mediators between the SM and DM candidates. Their interactions with SM gauge bosons are typically described using an effective field theory (EFT), where the leading coupling at dimension-5 involves the ALP field

a and the gauge field strengths.

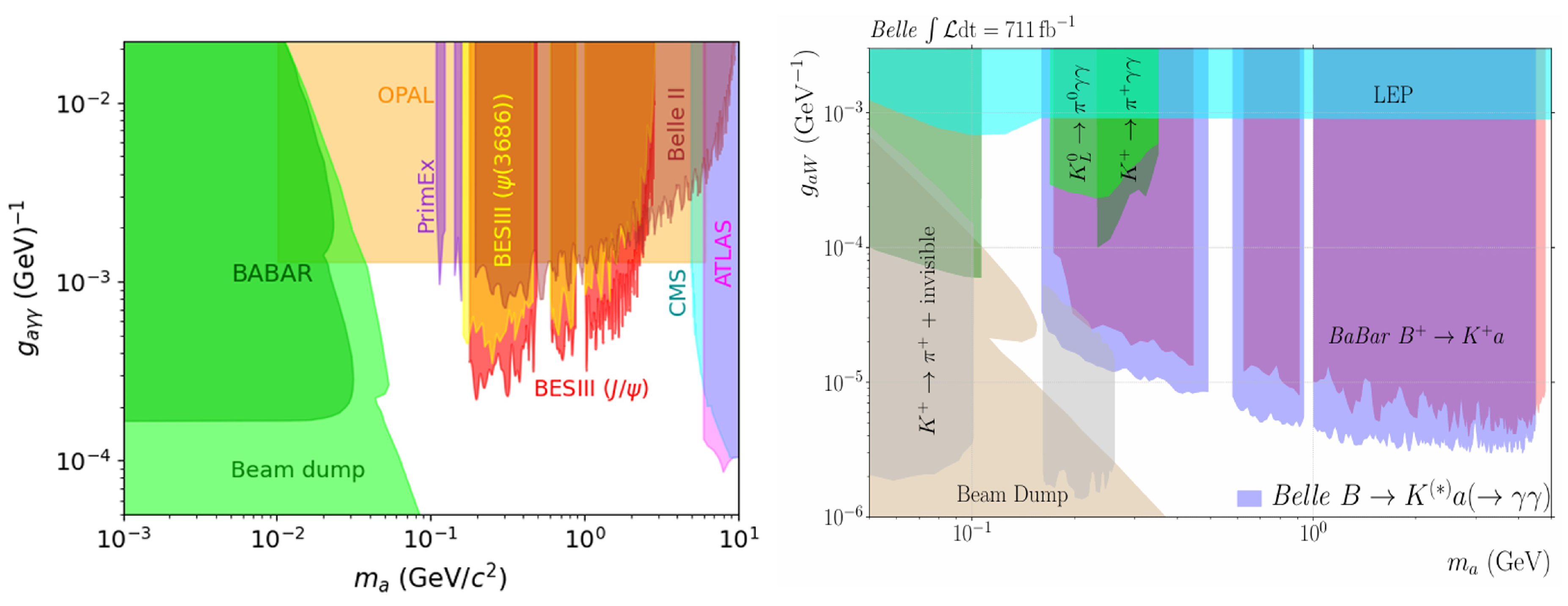

4.1. Coupling to Photon Pairs

The interaction of an ALP with two photons is given by the effective Lagrangian term:

where

is the electromagnetic field-strength tensor and

is its dual. The coupling

can be measured at

collider experiments via either the ALP-Strahlung process or radiative

V meson decays

with (

). The coupling

in the sub-GeV mass range, especially for ALP masses between 0.1 and 5 GeV, is less constrained compared to other regions. In this mass region, the Belle II and OPAL experiments have performed searches for ALPs via the ALP-Strahlung process

, while BESIII has performed a search via radiative

decays using 10 billion

events and 2.7 billion

events [

84]. The

data sample contains about a

contribution from the ALP-Strahlung process

and a

contribution from radiative

decay, along with the dominant SM background from

(

) decays. The search for signal events from the ALP

a was conducted by performing a series of fits to the combined di-photon spectrum after removing the backgrounds from

. No significant signal was found, and BESIII has set one of the most stringent upper limits on

in the mass range of

GeV [

84], as seen in

Figure 5 (left).

4.2. Coupling to W Bosons

ALPs can also couple to electroweak gauge bosons through the

field-strength tensor:

where

is the

field-strength tensor,

i labels the weak isospin components, and

is the ALP-W boson coupling. After electroweak symmetry breaking, this operator induces interactions of the ALP with the physical

bosons. This coupling leads to the production of ALPs at one loop in the process

, where the ALP is emitted from an internal

boson. Electroweak symmetry breaking and the resulting gauge-boson mixing also generate an effective ALP coupling to a pair of photons. In specific models, the branching fraction of

can be nearly

for

(to avoid other decays) or under specific assumptions, but it is model-dependent. The BaBar and Belle experiments have searched for ALPs in the reactions

and

, respectively, using their data samples collected at the

resonance, and reported null results. The Belle limits on the coupling to the

boson,

, which range from

GeV

−1 to

GeV

−1, are more stringent than the BaBar limits [

85], as seen in

Figure 5 (right).

4.3. ALP Signature with Invisible Final State

An ALP may also be involved in charged lepton–flavor–violating (CLFV) decays, such as

(

) [

86], where

corresponds to an ALP. The CLFV processes can occur in extended SM frameworks that include right-handed neutrinos. Their predicted branching fractions are expected to be at the level of

. The contribution of ALPs in such CLFV decays may enhance their decay rates up to the level of current experimental sensitivity. The search for an invisible signature of

in

has recently been performed by Belle II using 61.8 fb

−1 of data at the

resonance, resulting in a null observation [

87]. The reported

CL upper limits on the branching fractions

as a function of the

mass are the most stringent to date, as detailed in Ref. [

87]. A signature for an ALP with invisible final state in the decay

has also been explored by the BESIII experiment, with a null results [

88].

5. Neutrino Portal

The neutrino portal refers to interactions mediated by gauge-singlet fermions, commonly known as sterile neutrinos, right-handed neutrinos, or heavy neutral leptons (HNLs). The portal interaction is represented by

where

L is the lepton doublet,

H is the Higgs doublet,

is a right-handed (sterile) neutrino, and

is the Yukawa coupling.

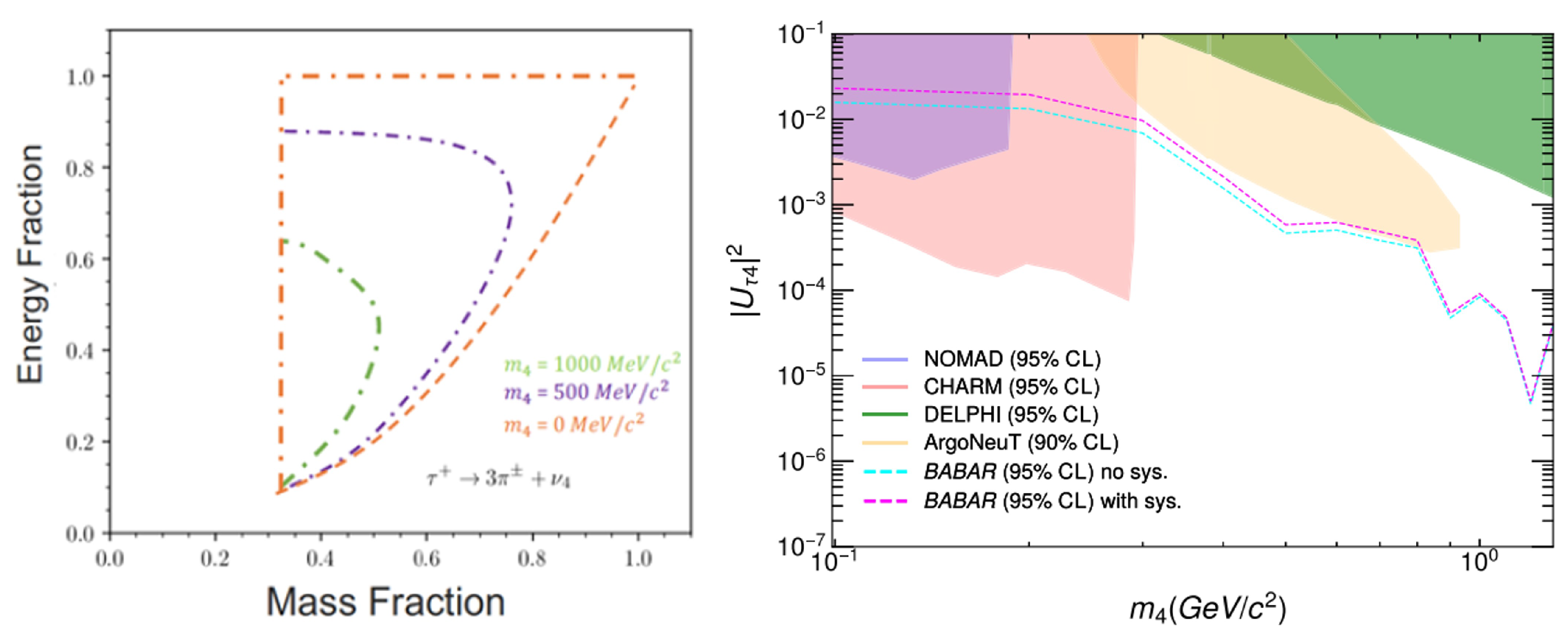

HNLs are additional neutrino states that are massive but neutral under all SM gauge interactions. In the MSM, introducing three sterile, right-handed Majorana HNLs to the SM can simultaneously explain neutrino oscillations, the origin of the baryon asymmetry of the Universe, and provide a dark-matter candidate. Two of these HNLs typically have masses in the MeV to GeV range, while the third—acting as a dark matter candidate—has a mass at the keV scale. The HNLs in the MeV–GeV mass range can be produced in semi-leptonic B decays, lepton-number violating (LNV) D decays, hadronic decays and quaorkonium decays, leading to possible deviations from SM expectations. Mixing between an HNL mass eigenstate and active neutrinos can be parametrized by an extended Pontecorvo–Maki–Nakagawa–Sakata (PMNS) matrix, with an additional element , where ℓ denotes the SM flavor state e, , or .

Experimental constraints on the mixing strength between the lepton sector and HNLs in the electron and muon sectors primarily come from LHC experiments in the higher HNL mass region. In the low-mass region, the exclusion limits on

mainly come from LNV decays

[

89], semi-leptonic

B decays [

90] and hadronic

decays [

91]. More recently, the BaBar experiment performed a search for an HNL that mixes with the SM

neutrino, characterized by the mixing parameter

(the absolute square of the corresponding extended PMNS matrix element), using a data sample of 424 fb

−1. BaBar conducted this study via the process

, where one

lepton is tagged through

, and the other decays via

[

92]. This channel allows sensitivity to HNL masses in the range

. In the decay

, the HNL

can mix with the SM neutrino. The mass of the missing neutrino

determines the two-dimensional distribution of the hadronic energy

versus the invariant mass of the hadronic system, as described in

Figure 6 (left).

The observed kinematic phase-space distributions of the hadronic system can be interpreted as a superposition of two components: one corresponding to decays mediated by the HNL (weighted by

), and one corresponding to SM neutrino decays (weighted by

). For a hypothetical mixing with the

lepton, the total differential decay rate becomes

No significant signal is observed, and upper limits on

at the 95% confidence level are set, depending on the HNL mass hypothesis shown in

Figure 6 (right). These limits range from

within the mass range

, representing the most stringent constraints to date [

92].

5.1. Invisible Decays

In the SM, neutrinos are invisible to particle detectors because they interact only via the weak force with extremely small cross sections. Their presence can be inferred only through the missing four-momentum in a decay. A quarkonium state, composed of a quark (

q) and its corresponding antiquark (

), may annihilate into a neutrino pair via a virtual

boson, but such processes are highly suppressed. The branching fractions of these rare decays could be enhanced in the presence of light dark matter (LDM) particles. Estimates of invisible quarkonium decays often assume a connection between the cross sections of the time-reversed processes,

, where

denotes a generic dark-matter particle. Exclusion limits on invisible decays of

[

93],

[

94],

/

[

95],

[

96],

[

97],

[

98],

[

99] mesons, and the

[

78] baryon have been reported by several collider experiments. A feasibility study of invisible decays of light vector mesons (

) by the STCF experiment has revealed that the

CL upper limits on the branching fractions of these decays could reach the level of

. The sensitivity could further reach the level of

using a deep-learning–based optimization technique, allowing tighter constraints on the parameter space of LDM scenarios [

100].

More recently, BESIII has reported a search for the FCNC decay

, which can proceed via the

transition. This decay is extremely suppressed due to angular-momentum constraints and remains so even if neutrinos have mass, because the required helicity configuration is unfavorable. The SM prediction for

is below

[

101]. Therefore, this decay provides a highly sensitive test of the SM. Several new physics scenarios predict enhancements: for example, models such as the Two-Higgs-Doublet Model (2HDM) may raise the branching fraction to the

level [

101], while mirror-matter theories—which postulate a parallel mirror sector—predict invisible branching fractions at the order of

[

102]. Invisible

decays also offer valuable input for tests of charge, parity, and time-reversal (CPT) symmetry, since the Bell–Steinberger relation connects possible CPT violation to the amplitudes of all kaon decay channels, assuming no invisible decay mode exists [

103].

The first direct search for invisible decays of the

meson has been performed by the BESIII Collaboration using

events [

103]. The

candidates are reconstructed from the decay

, which benefits from low background contamination because the decay

is forbidden by

C-parity conservation. No significant signal is observed, and an upper limit on the branching fraction,

, is set at the 90% confidence level for the first time.

6. Discussion

The paper reviews the current experimental status of dark matter searches at various collider experiments. In the sub-GeV mass range, hidden dark-sector models allow the possibility that SM particles couple to dark matter through different portals. The corresponding new-physics particles include dark photons, ALPs, light Higgs bosons, and sterile neutrinos. These particles have been searched for by multiple collider experiments, but so far only null results have been observed. The resulting exclusion limits have constrained large portions of the parameter spaces of physics models beyond the SM.

Although Belle II has so far collected only about of its target integrated luminosity, many of its early results related to the dark sector are already more stringent than those from the preceding B-factory experiments, such as BaBar and Belle. Therefore, Belle II is expected to play a major role in either discovering or ruling out new-physics scenarios associated with dark-matter portals. The BESIII experiment has also played a major role in exploring dark-sector searches, and its results, particularly for light Higgs bosons and ALPs, remain among the most stringent to date. BESIII has additionally explored invisible decays of light mesons and baryons and reported strong exclusion limits in these channels. Its successor, the STCF, will be capable of either discovering or excluding light dark-matter scenarios in searches for invisible decays of light mesons. Overall, while no signals of dark matter have yet been observed, the collider program continues to play a central role in shaping theoretical expectations and guiding future experimental developments.

7. Conclusions

The hidden dark-sector model introduces various types of sub-GeV dark-matter particles that can mediate interactions between the SM and the dark sector. One of the main efforts of the current generation of collider experiments is to search for these new-physics particles. However, only null results have been obtained so far. The resulting exclusion limits already rule out a large fraction of the parameter space of many new-physics models beyond the SM. In the future, the data collected by Belle II and STCF will be able to either discover or exclude these dark-matter scenarios.

Author Contributions

Vindhyawasini Prasad is the sole author of this work. He prepared this manuscript based on published theoretical and experimental results related to dark-sector searches at collider experiments.

Funding

This research was funded by the Seed Funding of Jilin University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

This study is a review article. No new data were created or analyzed, and data sharing is not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges that the content of this manuscript is based on published theoretical and experimental results related to dark-sector searches.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- S. Weinberg, Phys. Rev. Lett. 19, 1264 (1967); A. Salam, in Elementary Particle The ory, edited by N. Svartholm (Almquist and Wiksells, Stockholm, 1969), p. 367; S. L. Glashow, Nucl. Phys. 22, 579 (1961).

- S. L. Glashow, J. Iliopoulos, and L. Maiani, Phys. Rev. D 2, 1285 (1970).

- P. W. Higgs, Phys. Lett. 12, 132 (1964); P. W. Higgs, Phys. Rev. Lett. 13, 508 (1964); P. W. Higgs, Phys. Rev. 145, 1156 (1966); F. Englert and R. Brout, Phys. Rev. Lett. 13, 321 (1964); G. S. Guralnik, C. R. Hagen and T. W. B. Kibble, Phys. Rev. Lett. 13, 585 (1964).

- G. Aad et al. (ATLAS Collaboration), Phys. Lett. B 716, 1 (2012); S. Chatrchyan et al. (CMS Collaboration), Phys. Lett. B 716, 30 (2012).

- S. Weinberg, Phys. Rev. Lett. 43, 1566 (1979).

- M. Pospelov, Phys. Rev. D 80, 095002 (2009).

- A. B. McDonald, Rev. Mod. Phys. 88, 030502 (2016); T. Kajita, Rev. Mod. Phys. 88, 030501 (2016).

- Y. Sofue and V. Rubin, Ann. Rev. Astron 39, 137 (2009).

- O. Adriani et al., Nature 458, 607-609 (2009); M. Aguilar et al. (AMS Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 141102 (2013); J. Chang et al., Nature (London) 456, 362 (2008); M. Ackermann et al. (Fermi LAT Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 011103 (2012); M. Aguilar et al. (AMS Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 141102 (2013).

- G. Elor, M. Escudero, and A. Nelson, Phys. Rev. D 99, 035031 (2019); G. Alonso-Álvarez, G. Elor, and M. Escudero, Phys. Rev. D 104, 035028 (2021).

- J. Y. Su, J. Tandean, Phys. Rev. D 101, 035044 (2020).

- M. Cicoli, J. P. Conlon and F. Quevedo, Phys. Rev. D 87, 043520 (2013).

- G. Cacciapaglia, A. Deandrea and W. Isnard, Phys. Rev. D 109, 015024 (2024).

- B. Holdom, Phys. Lett. B 166, 196 (1986).

- M. Battaglieri et al., US Cosmic Visions: New Ideas in Dark Matter 2017: Community Report, arXiv:1707.04591 [hep-ph] (2017).

- E. Kou et al. (Belle II Collaboration), The Belle II Physics Book, PTEP 2019, 123C01 (2019).

- R. Essig et al., arXiv:1311.0029 (2013). arXiv:1311.0029.

- B. Aubert et al. (BaBar Collaboration), The BaBar Detector, Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 479, 1 (2002).

- M. Ablikim et al. (BESIII Collaboration), Chin. Phys. C 44, 040001 (2020).

- J. G. D. Costa, Y. Gao, S. Jin, J. Qian, C. Tully and C. Young, CEPC Conceptual Design Report: Volume 2 - Physics & Detector, arXiv:1811.10545 (2018).

- M. Achasov et al., STCF Conceptual Design Report: Volume 1 – Physics @ Detector, Front. Phys. 19 (1), 14701 (2024).

- N. A. Hamed, D. P. Finkbeiner, T. R. Slatyer and N. Weiner, Phys. Rev. D 79, 015014 (2009).

- B. A. Dobrescu, Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 151802 (2005).

- J. Pan, M. He, X. He, and G. Li, Nucl. Phys. B 953, 114968 (2020).

- H. Ruegg and M. Ruiz-Altaba, Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 19, 3265 (2004).

- S. Li, J. M. Yang, M. Zhang. Y. Zhang, and R. Zhu, arXiv:2506.20208 (2025). arXiv:2506.20208.

- G. Lanfranchi, M. Pospelov, and P. Schuster, Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 71, 279 (2021).

- B. Batell, M. Pospelov and A. Ritz, Phys. Rev. D 79, 115008 (2009).

- R. Essig, P. Schuster and N. Toro, Phys. Rev. D 80, 015003 (2009).

- J. Liu, N. Weiner and W. Xue, JHEP 08, 050 (2015).

- E. Cortina Gil et al. (NA62 Collaboration), JHEP 02, 201 (2021).

- S. Abrahamyan et al. (APEX Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 191804 (2011).

- H. Merkel et al. (A1 Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 221802 (2014); Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 251802 (2011.

- J. P. Lees et al. (BaBar Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 201801 (2014).

- M. Ablikim et al. (BESIII Collaboration), Phys. Lett. B 839, 137785 (2023); Phys. Rev. D 99, 012013 (2019); Phys. Rev. D 99, 012006 (2019) [Erratum: Phys. Rev. D 104, 099901 (2021)].

- A. Anastasi et al. (KLOE-2 Collaboration), Phys. Lett. B 757, 356 (2016).

- J. R. Batley et al. (NA48 Collaboration), Phys. Lett. B 746, 178 (2015).

- R. Asij et al. (LHCb Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 061801 (2018).

- M. Pospelov, Phys. Rev. D 80, 095002 (2009).

- Y. M. Andreev et al. (NA64 Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 161801 (2023).

- J. P. Lees et al. (BaBar Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 131804 (2017).

- M. Ablikim et al. (BESIII Collaboration), Phys. Lett. B 839, 137785 (2023).

- B. Aubert et al. (BaBar Collaboration), arXiv:0908.2821 (2009).

- B. A. Dobrescu, Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 151802 (2005).

- M. Ablikim et al. (BESIII Collaboration), Phys. Lett. B 852, 138614 (2024).

- M. Ablikim et al. (BESIII Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 106, 072008 (2022).

- M. Ablikim et al. (BESIII Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 111, L011103 (2025).

- R. M. Baltrusaitis et al. (MARK-III Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 56, 2140 (1986).

- A. Delgado, C. Kolda, and A. D. Puente, Phys. Lett. B 710, 460 (2012).

- M. Maniatis, Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 25, 3505-3602 (2010).

- F. Wilczek, Phys. Rev. Lett. 39, 1304 (1977).

- R. Dermisek, J. F. Gunion and B. McElrath, Phys. Rev. D 76, 051105 (2007).

- M. Ablikim et al. (BESIII Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 105, 012008 (2022).

- J. P. Lees et al. (BaBar Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 87, 031102(R) (2013).

- S. Jia et al. (Belle Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 081804 (2021).

-

https://indico.cern.ch/event/181298/contributions/309553/attachments/243619/340902/ichep12_kolomensky.pdf.

- M. Ablikim et al. (BESIII Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 85, 092012 (2012); Phys. Rev. D 93, 052005 (2016); Phys. Rev. D 101, 112005 (2020).

- J. P. Lees et al. (BaBar Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 211801 (2012).

- I. Jaegle et al. (Belle Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 211801 (2015).

- A. Anastasi et al. (KLOE-2 Collaboration), Phys. Lett. B 747, 365 (2015).

- I. Adachi et al. (Belle II Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 135, 131801 (2025).

- R. Aliberti et al. (White Paper WP25) Phys. Rept. 1143, 1 (2025).

- T. Czank et al. (Belle Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 106, 012003 (2022).

- P. Foldenauer, Phys. Rev. D 99, 035007 (2019).

- X. G. He, G. C. Joshi, H. Lew and R. R. Volkas, Phys. Rev. D 43, 22 (1991); Phys. Rev. D 44, 2118 (1991).

- J. P. Lees et al. (BaBar Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 94, 011102 (2016).

- A. M. Sirunyan et al. (CMS Collaboration), Phys. Lett. B 792, 345 (2019).

- T. Czank et al. (Belle Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 106, 012003 (2022); I. Adachi et al. (Belle II Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 109, 112015 (2024).

- D. Biswas et al. (Belle Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 109, 032002 (2024).

- I. Adachi et al. (Belle II Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 181801 (2020).

- M. Ablikim et al. (BESIII Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 109, L031102 (2024).

- A.D. Sakharov JETP Lett. 6, 24 (1967).

- K. Petraki and R. R. Volkas, Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 28, 1330028 (2013).

- K. M. Zurek, Phys. Rept. 537, 91 (2014).

- B. Fornal and B. Grinstein, Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 191801 (2018); [Erratum: Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 219901 (2020)].

- A. E. Nelson and H. Xiao, Phys. Rev. D 100, 075002 (2019); G. Alonso-Alvarez, G. Elor and M. Escudero, Phys. Rev. D 104, 035028 (2021).

- J. P. Lees et al. (BABAR Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 107, 092001 (2023); Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 201801 (2023); Phys. Rev. D 111, L031101 (2025).

- M. Ablikim et al. (BESIII Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 105, L071101 (2022).

- M. Ablikim et al. (BESIII Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 111, 052014 (2025); Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 082101 (2023).

- M. Ablikim et al. (BESIII Collaboration), arXiv:2505.22140 (2024). arXiv:2505.22140.

- S. Weinberg, Phys. Rev. Lett. 40, 223 (1978); F. Wilczek, Phys. Rev. Lett. 40, 279 (1978).

- G. C. Branco et al., Phys. Rept. 516, 1 (2012).

- A. Ringwald, J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 485, 012013 (2014).

- M. Ablikim et al. (BESIII Collaboration), Phys. Lett. B 838, 137698 (2023); Phys. Rev. D 110, L031101 (2023).

- I. Adachi et al. (Belle II Collaboration), arXiv:2507.01249 (2025).

- L. Calibbi, D. Redigolo, R. Ziegler, and J. Zupan, JHEP 09, 173 (2021).

- I. Adachi et al. (Belle II Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 181803 (2023).

- M. Ablikim et al. (BESIII Collaboration), Phys. Lett. B 135, 151804 (2025).

- M. Ablikim et al. (BESIII Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 99, 112002 (2019).

- D. Liventsev et al. (Belle Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 87, 071102 (2013).

- D. Liventsev et al. (Belle Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 211802 (2023).

- J. P. Lees et al. (BaBar Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 107, 052009 (2023).

- B. Aubert et al. (BaBar Collaboration), Search for Invisible Decays of the Υ(1S), Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 251801 (2009).

- M. Ablikim et al. (BES Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 192001 (2008).

- C. L. Hsu et al. (Belle Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 86, 032002 (2012); G. Alonso-Álvarez and M. E. Abenza, Eur. Phys. J. C 84, 553 (2024).

- M. Ablikim et al. (BESIII Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 87, 012009 (2013); M. Ablikim et al. (BES Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 202002 (2006).

- E. Cortina Gil et al. (NA62 Collaboration), JHEP 02, 201 (2021).

- Y. T. Lai et al. (Belle Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 95, 011102 (2018).

- M. Ablikim et al. (BESIII Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 98, 032001 (2018).

-

https://indico.pnp.ustc.edu.cn/event/4580/contributions/32042/attachments/11770/18351/Invisible_decays_of%20light_mesons.pdf.

- S.N. Gninenko, Phys. Rev. D 91, 015004 (2015).

- W. Tan, arXiv:2006.10746; R. N. Mohapatra, Entropy 26, 282 (2024). arXiv:2006.10746.

- M. Ablikim et al. (BESIII Collaboration), JHEP 92 (2025) 092.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).