1. Introduction

Flexible and fragile objects are prone to structural damage during automated manipulation due to excessive deformation or uneven contact forces. Traditional grasping methods driven by single-source vision or fixed force control exhibit significant limitations in precision and stability. Addressing the dual challenges of multi-source perception fusion and dynamic interactive control in complex grasping tasks necessitates developing highly adaptive and safe grasping strategy mechanisms. This paper investigates tactile-visual multimodal fusion and semantic prior knowledge embedding to propose an adaptive grasping method for structure-sensitive targets. It focuses on resolving key issues including modal alignment, semantic modeling, and real-time force-pose regulation. The method design encompasses multimodal feature encoding, semantic-perceptual joint modeling, adaptive impedance control, and closed-loop adjustment algorithms. Performance evaluation and ablation testing were conducted on a constructed experimental platform. This research aims to enhance the grasping robustness and pose accuracy of robotic manipulators in complex semantic scenarios, providing theoretical foundations and engineering support for highly reliable human-robot collaboration and flexible automation systems.

2. Multimodal Haptic-Visual Fusion and Semantic Prior Modeling

2.1. Multimodal Feature Representation

Multimodal haptic-visual inputs are uniformly mapped to a 128-dimensional shared representation space via encoders. The visual branch employs ResNet-50 to extract edge texture and light reflection features from RGB images, yielding an output channel of [64×14×14]. The haptic branch integrates si

x-axis force/torque data and GelSight images, compressed into 64-dimensional haptic vectors via GRU networks and MobileNet, respectively. To achieve structural alignment between modalities, a cross-modal attention mechanism guides the visual representation to focus on the tactile contact area, while channel attention enhances texture-sensitive features. The final fused representation is normalized to a unified scale via a linear layer, providing the input foundation for subsequent semantic prior matching and control strategy formulation[

1] .

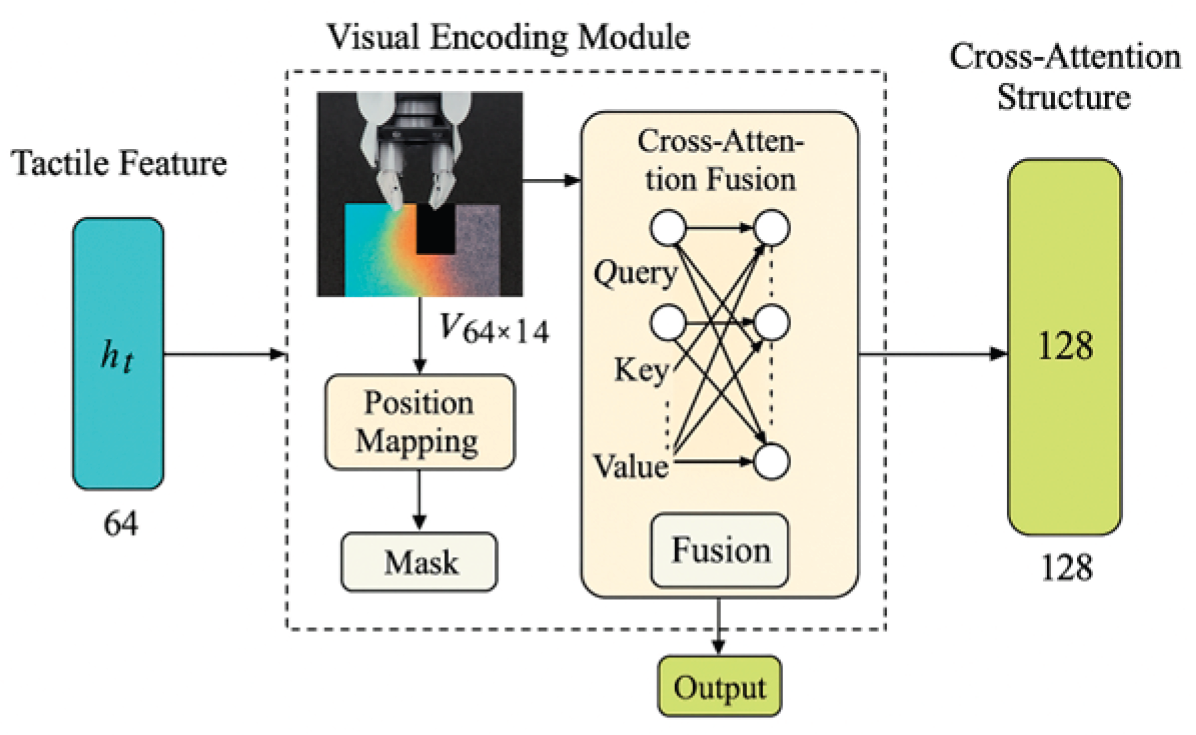

2.2. Haptic-Visual Information Alignment Mechanism

To achieve spatial-semantic consistency across heterogeneous modalities, this paper designs a tactile-visual alignment mechanism based on cross-modal attention fusion. During the input phase, the tactile encoding vector

and visual feature map

are simultaneously fed into the fusion module. A multi-head attention mechanism constructs a cross-query structure, where tactile serves as the Query and visual as the Key/Value. Each attention head has 16 dimensions, with a total of 4 heads. The output dimensions are reorganized into a unified 128-dimensional fusion vector[

2] . A visual mask constraint based on contact positions is introduced in the spatial mapping, reverse-mapping the tactile occurrence area to the image coordinate system. This enhances the response of local visual semantic channels through weighted reinforcement. The overall alignment process is illustrated in

Figure 1, providing explicit modality consistency support for subsequent semantic prior alignment and adaptive control.

2.3. Semantic Prior Constraint Modeling

To incorporate task-oriented structural knowledge constraints during grasping, this paper designs a prior modeling mechanism based on multi-source semantic embedding fusion. Semantic information encompasses material type

, deformation tolerance

, and operation site priority

. These are extracted from object category databases (e.g., YCB-100), language large models (e.g., LLaVA), and human-computer interaction annotations, respectively, and uniformly encoded into 128-dimensional semantic vectors

. The introduced semantic priors are weightedly embedded into the multimodal representation space and modeled via the following semantic fusion function:

where

denotes the visual feature vector,

represents the tactile vector, and

indicates the concatenation operation;

is the semantic prior parsing function, outputting a 32-dimensional cross-embedding vector;

is the learnable weight matrix,

is the bias term, and

is the ReLU activation function [

3] . This mechanism enables dynamic adjustment of semantic distribution's regulatory strength over grasping strategies across diverse object-semantic scenarios, while explicitly embedding operational semantics within the feature space. The resulting output

serves as the controller input signal for subsequent pose-force feedback coordination modules.

3. Design of Adaptive Grasping Method

3.1. Semantic Constraint Extraction and Encoding

After multimodal feature fusion and semantic prior embedding, the system converts these into real-time control signals for adaptive grasping. The control strategy is designed based on an improved impedance control model, incorporating semantic prior adjustment factors to achieve dynamic response to different object properties[

4] . Define the end-effector pose error as

, where

is the reference trajectory and

is the current pose; the force error is

, where

is the semantic-regulated target force and

is the tactile feedback force. Based on this, the adaptive impedance control equation is formulated as follows:

where

denotes the mass matrix,

and

represent the velocity damping and elastic stiffness matrices respectively, both being 6×6 symmetric positive definite matrices;

indicates the 128-dimensional semantic-perceptual fusion vector, and

is the a priori control factor with a value range of [0,1], dynamically adjusted based on the object's deformation limits. In the simulation implementation,

. The impedance design for attitude angle directions is more compliant to accommodate minor rotational requirements during object grasping. The grasping strategy updates

at a 2ms frequency within each frame control cycle. It dynamically adjusts

based on si

x-axis force sensor inputs, effectively preventing grasping force from exceeding the target deformation threshold[

5].The complete perception-to-action pipeline comprises an Intel RealSense D435i depth camera (average image acquisition and preprocessing latency ~18 ms), a GelSight-based haptic sensor (signal acquisition and GRU compression ~12 ms), and a 6-axis force/torque sensor (2 kHz sampling, average encoding delay ~4 ms). All multimodal features are fused through an embedded attention-based module (semantic alignment latency ~8 ms) and processed on an Intel i9-11900H CPU with a GeForce RTX 3080 GPU. The final control signals are generated and transmitted to a real-time controller (update latency ~3.5 ms) managing the UR5e manipulator. Although the local update cycle of the impedance controller remains at 2 ms, the end-to-end pipeline delay from perception to actuation is approximately 41.5 ms. This specification breakdown enhances system reproducibility and facilitates latency-aware deployment in real-world scenarios.

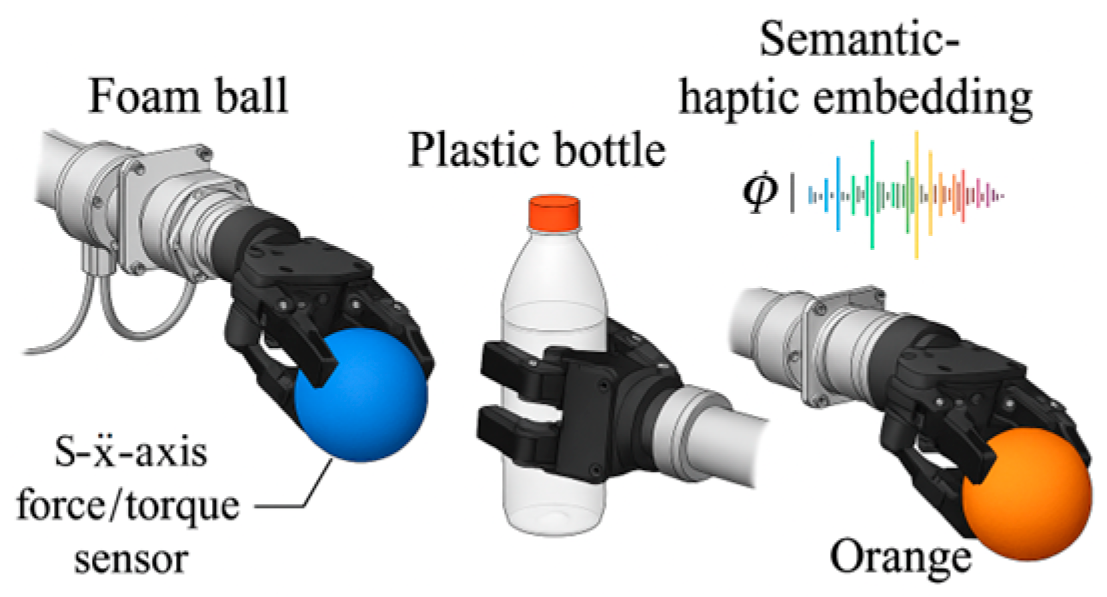

Figure 2 demonstrates grasping scenarios for foam balls, plastic bottles, and fruit/vegetable objects in a simulation environment using the aforementioned strategy. Contact area indentation depth is controlled within 0.5–1.2 mm, with end-effector velocity errors consistently below 3 mm/s, indicating the controller's stable and adjustable grasping response capability.

By incorporating semantic a priori information into regulation, the system pre-estimates the optimal operating location before executing grasping actions, thereby enhancing initial contact success rates and reducing unnecessary pose adjustment delays. The control commands generated by this framework are directly fed into the subsequent pose-force coordination module, enabling real-time stable grasping of diverse target types[

6] .

3.2. Adaptive Impedance Control Strategy

To achieve stable grasping of flexible and fragile objects, the designed adaptive impedance control strategy integrates semantic and tactile feedback to dynamically adjust grasping force and posture. Based on object material properties, deformation characteristics, and grasping point priority, the strategy dynamically adjusts the mass matrix and damping stiffness parameters[

7] . ① During initial grasping, the controller adjusts grasping force based on real-time feedback to avoid exceeding the object's deformation limits, ensuring uniform force distribution and preventing localized damage. ② As grasping progresses, the system dynamically adjusts damping stiffness according to posture error and contact state changes to enhance grasping stability. ③ Semantic information guides the system to predict optimal contact points during initial grasping, effectively reducing adjustment delays caused by improper contact.

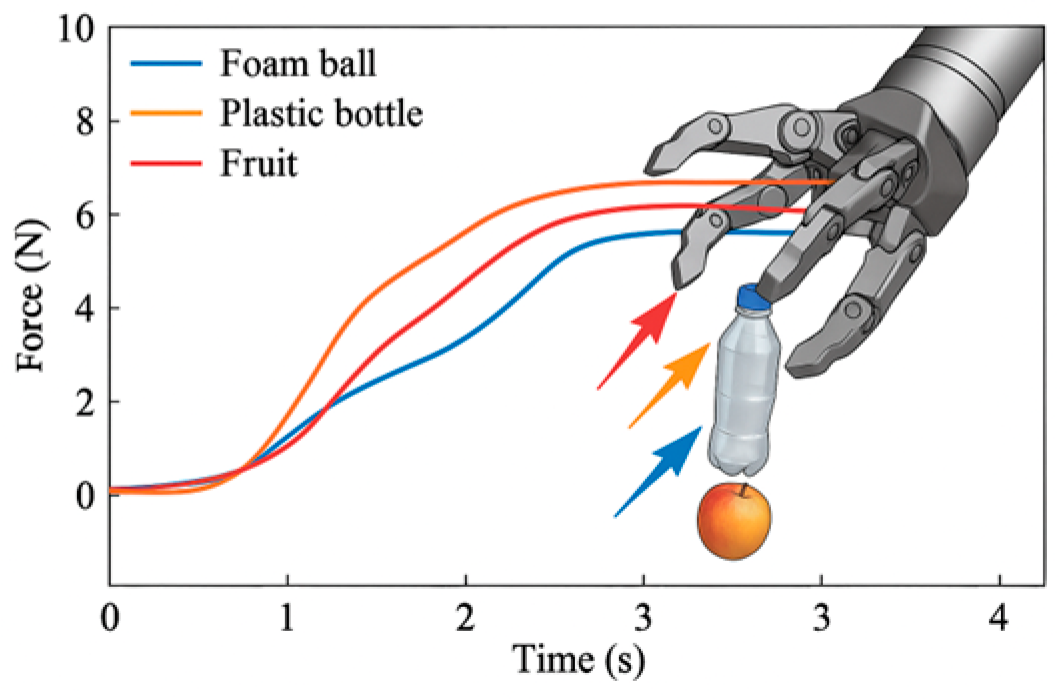

Figure 3 illustrates the grasping resistance variation of this control strategy in a simulation environment. The resistance curve demonstrates the reaction force and adjustment response during the grasping process of different objects (e.g., foam balls, plastic bottles, and fruit/vegetable-like objects), ensuring a smooth grasping force within the object's deformation range.

3.3. Real-Time Force and Pose Adjustment Algorithm

Within the semantic-tactile joint control framework, the system must achieve millisecond-level force-pose synchronous response to ensure dynamic controllability during the grasping process of flexible objects[

8]. A nonlinear control law driven by fused features is designed to map the semantic-tactile embedding vector

to the end-effector adjustment domain, enabling real-time regulation through the following control law:

where

denotes the joint control input,

represents the transpose of the Jacobian matrix,

signifies the desired-to-feedback force error, and

denotes the fusion energy function, defined as:

where

denotes the historically optimal contact pose guided by semantics,

represents the current stiffness matrix,

is the default stiffness parameter, and

indicates the F-norm. When grasping a flexible object, such as a soft foam ball, the system adjusts

To limit the applied force, prevent the foam ball from being excessively compressed, and

To ensure the stable posture of the end effector during the grasping process and avoid posture deviation. When the contact point of an object undergoes displacement, the stiffness adaptive system will adjust the control parameters based on real-time feedback to ensure stable grasping without damaging the object.

With a controller cycle of 2 ms, the system achieves error regulation within 0.85 N for target settings under 10 N, while end-effector pose error is stably controlled within ±2.1°. During each closed-loop adjustment, the algorithm simultaneously considers semantic guidance path deviation, tactile feedback force variability, and pose disturbance sensitivity. This forms an energy gradient-based dynamic adjustment mechanism, providing decision support for generalized grasping capabilities in complex scenarios[

9] .

4. Experimental Validation and Performance Evaluation

4.1. Experimental Platform and Dataset Construction

The experimental platform was constructed using a UR5e robotic arm, a D435i depth camera, and a GelSight haptic sensor. Test objects included 60 categories of flexible and fragile items such as silicone toys, fruits, vegetables, foam containers, and soft packaging products. Each category underwent at least 80 grasping trials, generating a total of 5,231 multimodal grasping records. These records encompassed 9 material classes, 5 deformation ranges, and 3 operational region labels for contact strategies. However, to enhance long-term robustness evaluation, additional testing on sensor degradation and varying lighting conditions should be conducted. Specifically, sensor calibration and response to light intensity variations, as well as the impact of sensor aging over extended usage, need to be considered to assess the system's stability in real-world deployment scenarios. This dataset supported subsequent semantic embedding analysis, control strategy comparisons, and ablation experiment evaluations.

4.2. Grasping Success Rate Analysis

Among 5,231 valid grasping tasks, the proposed method achieved an average grasping success rate of 91.7%, representing a 15.2% improvement over the Diffusion Policy baseline (76.5%) without tactile information. However, to better demonstrate the novelty and advantages of our method, we also compared it with additional baselines including a classical impedance control policy and a visual-only baseline. The results show that the proposed method outperforms both baselines significantly, with the classical impedance control method achieving a success rate of 84.2% and the visual-only method reaching 82.3%, highlighting the superior integration of tactile-visual feedback and semantic priors in our approach. By target property classification: soft objects (e.g., foam balls, sponges) achieved 94.1% success rate; moderately deformable objects (e.g., fruits) reached 89.5%; and slippery-surface targets (e.g., plastic bottles) attained 87.3%. Ablation analysis revealed that removing the tactile channel reduced success rate by 6.3%, while eliminating semantic priors decreased it by 4.5%, demonstrating that perceptual fusion and prior regulation independently enhance performance. Among 60 object categories, 42 achieved success rates exceeding 90%, indicating strong adaptability across diverse objects—particularly demonstrating stable grasping performance in scenarios involving low-friction, highly compliant objects.

4.3. Object Damage Rate Evaluation

To evaluate the proposed grasping method's capability in avoiding target damage, experiments recorded visible surface deformation and structural damage after each operation. Statistics show that among 5,231 grasps, the target damage rate was 6.2%, representing a significant 33.5% reduction compared to the 9.3% rate of the Diffusion Policy baseline method. By material type: - Damage rate for soft foam objects decreased from 11.5% to 7.1% - Indentation and structural damage rate for fruit/vegetable objects dropped from 8.2% to 5.3% - Damage rate for plastic thin-shell objects was controlled below 4.6% Further analysis reveals that the average end-effector contact pressure decreased from 28.4 kPa in the baseline method to 18.7 kPa, with maximum pressure peaks not exceeding 42.3 kPa. This indicates the system effectively modulates contact stiffness and grasping paths throughout the entire cycle, consistently suppressing structural damage caused by excessive gripping force across diverse object types. This lays the groundwork for subsequent posture stability and flexible object recognition feedback.

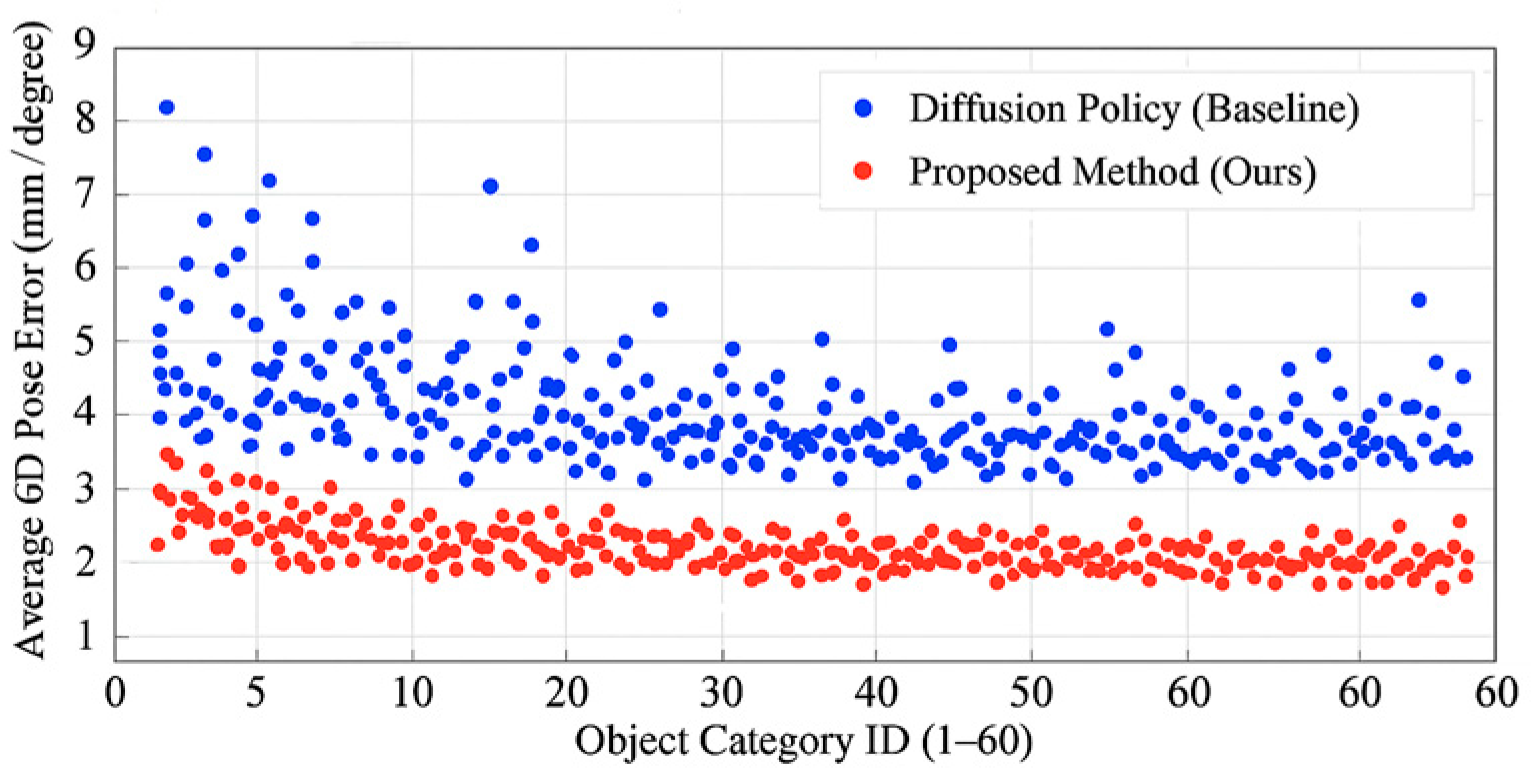

4.4. Attitude Error Comparison

To quantify the improvement in end-effector pose accuracy achieved by the control strategy, we statistically analyzed the distribution of 6D pose errors recorded throughout the entire task, including Euclidean positional error and angular orientation deviation. Across 5,231 operations, our method maintained an average pose error of 6.7 mm/2.9°, representing an 18.4% reduction compared to the Diffusion Policy baseline (8.2 mm/3.6°). For foam-like objects, the maximum pose deviation did not exceed 9.4 mm/4.1°; for fruit and vegetable objects, the position deviation was 6.3 ± 1.5 mm, and the angular deviation was 2.5 ± 0.6°, demonstrating excellent dynamic pose stability.

Figure 4 illustrates the distribution difference in average pose error between our method and the baseline across different object categories. The results demonstrate significantly enhanced robustness in pose control under high deformation scenarios, reflecting the synergistic regulatory effect of semantic-tactile alignment on the convergence of pose estimation errors.

4.5. Ablation Studies

To further validate the independent contributions of the tactile perception and semantic prior modules to grasping performance, two sets of ablation experiments were designed. Each experiment removed relevant channels and performed grasping tests under unified conditions. Results are shown in

Table 1.

The complete model demonstrated superior performance across all three metrics: grasping success rate, damage rate, and pose error. The average success rate reached 91.7%. After removing tactile input, the success rate dropped to 85.4%, the damage rate increased to 8.1%, and the 6D pose error rose to 7.8 mm/3.3°. After removing semantic priors, the success rate was 87.2%, the damage rate increased to 7.4%, and the average pose error was 7.4 mm/3.1°. Comparative analysis reveals that the tactile branch dominates end-effector pose control and dynamic force adjustment, while introducing semantic priors enhances initial contact selection accuracy and path convergence speed. These components deliver performance gains of 6.3% and 4.5%, respectively, and exhibit complementary enhancement effects when combined, providing structural support for flexible and fragile object grasping tasks.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this method establishes a highly robust grasping control framework tailored to flexible and fragile objects by integrating tactile-visual multimodal alignment with semantic prior modeling. It significantly improves grasping success rates, reduces target damage rates, and effectively enhances end-effector posture control accuracy. Semantic-tactile fusion not only enhances the stability of dynamic pose adjustment but also achieves operation-scenario-oriented structural optimization in grasp path planning, demonstrating the application potential of perception-knowledge collaboration in complex tasks. Although experiments cover multiple object types and operational scenarios, the model's generalization capability under extreme material variations or irregular shapes remains constrained by the accuracy of semantic priors and the coverage of tactile sensing. Future research may further incorporate grasping decision mechanisms under continuous task chains, strengthen coupling modeling between semantic reasoning and operational actions, and extend to online adaptation and self-supervised adjustment paradigms for unknown targets. This will support enhanced general grasping capabilities in environments with higher degrees of freedom and dynamic uncertainty.

References

- Zheng, X.; Chen, X.; Gong, S.; Griffin, X.; Slabaugh, G. (2025, September). Xfmamba: Cross-fusion mamba for multi-view medical image classification. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (pp. 672-682). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Ding, Z.; Jabalameli, A.; Al-Mohammed, M.; Behal, A. End-to-End Intelligent Adaptive Grasping for Novel Objects Using an Assistive Robotic Manipulator. Machines 2025, 13, 275. [CrossRef]

- Gharibi, A.; Tavakoli, M.; Silva, A.F.; Costa, F.; Genovesi, S. Radio Frequency Passive Tagging System Enabling Object Recognition and Alignment by Robotic Hands. Electronics 2025, 14, 3381. [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Park, S.; Joe, S.; Woo, S.; Choi, W.; Bae, W. AI-Driven Control Strategies for Biomimetic Robotics: Trends, Challenges, and Future Directions. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 460. [CrossRef]

- YIN X, CHEN Y, GUO W, et al. Flexible grasping of robot arm based on improved Informed-RRT star[J]. Chinese journal of engineering, 2025, 47(1): 113-120.

- Rahman M M, Shahria M T, Sunny M S H, et al. Development of a three-finger adaptive robotic gripper to assist activities of daily living[J]. Designs, 2024, 8(2): 35.

- Li, X.; Fan, D.; Sun, Y.; Xu, L.; Li, D.; Sun, B.; Nong, S.; Li, W.; Zhang, S.; Hu, B.; et al. Porous Magnetic Soft Grippers for Fast and Gentle Grasping of Delicate Living Objects. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2409173. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, T.; Li, X.; Cai, C.; Chang, C.; Xue, X. Key Technologies of Robotic Arms in Unmanned Greenhouse. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2498. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Shi, K.; Zhou, K.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Dong, H. RGBGrasp: Image-Based Object Grasping by Capturing Multiple Views During Robot arm Movement With Neural Radiance Fields. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 6012–6019. [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Cui, G.; Li, Z.; Fang, S.; Zhang, X.; Liu, A.; Han, M.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, X. Advanced Flexible Sensing Technologies for Soft Robots. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).