1. INTRODUCTION

Thorium has emerged as one of the most promising alternatives to conventional uranium fuel cycles. Its potential applications extend to Molten Salt Reactors (MSR), Advanced Heavy Water Reactors (AHWR), and High Temperature Reactors (HTR) [

1,

2]. Together with U-233 assemblies, thorium has also been considered for use in Innovative Accelerator Driven Systems (ADS) operating within dual-layer fuel cycles [

3,

4,

5]. In the United States, research efforts produced a pressurized solid-fuel reactor channel design - initially patented as the Actively Cooled Fuel (EACF) concept and later developed into the Dual Fluid Reactor (DFR). This system employs ThO₂ as the primary fuel and a eutectic NaF-ZrF₄ salt mixture as coolant [

6]. Importantly, modular thorium reactor concepts have been developed to provide electrical outputs in the range of 100 to 3000 MW [

7,

8], underscoring their scalability and adaptability to the energy demands of nuclear producing countries.

The interest in thorium-based systems has been fueled by both their favorable nuclear properties and the limitations of conventional uranium cycles. Most commercial nuclear reactors in operation today rely on uranium fuel, predominantly within once-through cycles (OTC) [

9]. These systems, classified as Generation II reactors, continue to dominate the global nuclear fleet [

10].

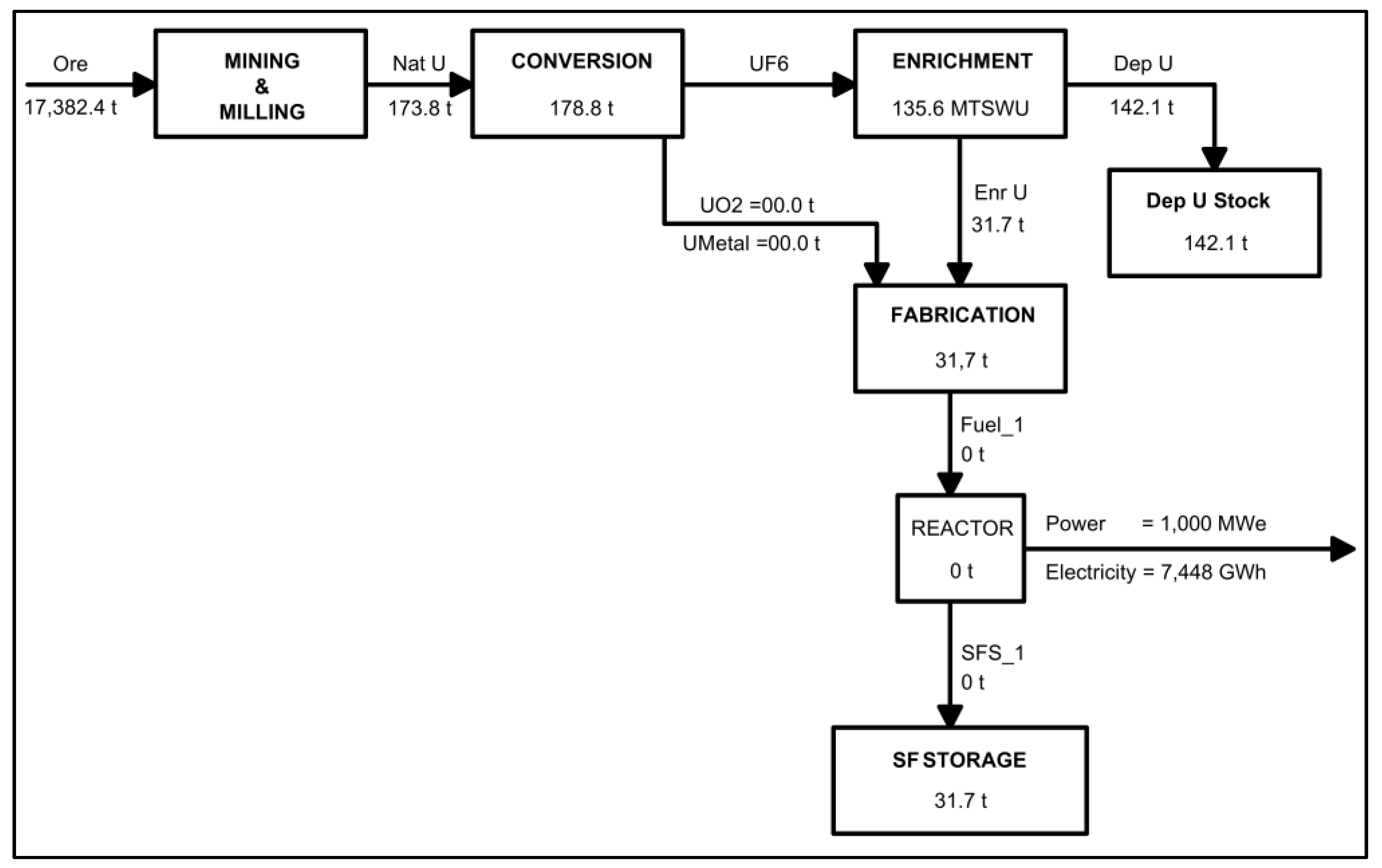

Figure 1 illustrates the mass balance for a typical Generation II PWR [

1].

The overall material flow in the uranium fuel cycle can be described by tracking nuclear materials through each process stage. A variety of fuel cycle models can be simulated, involving different reactor and fuel types, including hypothetical options such as minor actinide-containing fuels, provided the appropriate data libraries are available [

11,

12]. In [

13], several commercially relevant variants of the nuclear fuel cycle were modeled, including the once-through cycle and the recycling of U and Pu into LWRs in the form of MOX fuel.

Long-term reliance on uranium cycles has revealed structural challenges for the nuclear industry. Declining competitiveness, coupled with environmental risks linked to potential core meltdowns and persistent negative public perception after past accidents, has underscored the need for innovation [

16]. These challenges stimulated the development of advanced reactor concepts designed to integrate passive safety features, improve public acceptance, and maintain competitiveness in the national energy mix [

17,

18].

Reactors of this type, commonly referred to as Generation III, are now in advanced stages of development. Many are under construction, and some are already in operation. For example, construction of the European Pressurized Water Reactor (EPR) began in France in 2007, though it experienced major delays and cost overruns [

19]. Similar uncertainties remain regarding the Guangdong Taishan EPR-1 in China, which is not yet operational. Meanwhile, the EPR-2, under construction in China, is projected to deliver a standard output capacity of approximately 1770 MW [

20].

Against this background, the present study reviews the research and development of innovative modular thorium reactors in nuclear-producing countries, emphasizing their role in future nuclear fuel cycles and the prospects for integration into advanced PWR concepts [

21,

22,

23].

A significant body of scientific literature focuses on catastrophic accidents involving pressurized water reactors (PWRs) and boiling water reactors (BWRs), which represent only part of the global reactor fleet [

16]. In order to achieve a more comprehensive understanding, researchers have increasingly extended their analysis to other reactor types, such as VVER, CANDU, and PHWR. Studying specific nuclear accidents across diverse reactor designs can reveal unforeseen vulnerabilities and provide valuable insights for future innovations. An OECD NEA review stresses thorium’s resource and safety advantages but concludes that immaturity of technologies, cost, and limited experience prevent it from competing with uranium cycles in the near term [

21].

In the aftermath of the atomic bomb, the use of nuclear energy was initially viewed with deep suspicion because it was primarily seen as a technology associated with destruction. When its military applications were determined to be far too catastrophic to pursue any further, attention gradually shifted to the possibility that it could be a peaceful and economical source of power [

19]. This transition marked the beginning of a period of intense creativity and innovation in nuclear science and technology, which was comparable to the momentum seen in other transformative fields of research [

24].

In 2006 a renewed wave of interest in nuclear power emerged, driven in part by the sharp rise in oil prices - first in the United States and subsequently in other industrialized nations - together with national programs to support the development of new reactor generations. In the late 1990s, complex reactor core designs for PWRs and VVERs became the focus of significant international investment, particularly in developing countries [

25,

26].

These projects often involved long-term financial commitments, as reactors were typically acquired through loans requiring repayment over several decades. In addition, ongoing guarantees of fuel supply were necessary, effectively narrowing the scope for alternative reactor deployment [

10]. While such arrangements imposed structural rigidity, they also provided stability: protecting both consumers and producers, mitigating risks of developer insolvency, and encouraging continuous innovation to ensure the recovery of initial investments [

16].

2. THOURIUM AS NUCLEAR FUEL

Thorium is now being reconsidered as a viable nuclear fuel option due to its abundance, favorable thermal characteristics, and its promise for advanced reactors. The evaluation has identified several challenges, such as the handling of U-233, existing technological gaps, and economic concerns [

19]. At Sweden’s Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, researchers have submitted numerous dissertations covering thorium reprocessing in reactors and approaches in nuclear physics pertinent to producing countries [

22]. Similar investigations are occurring in other regions, reflecting a growing commercial interest in thorium as a nuclear fuel [

1]. Thorium has long been ignored in the U.S. for commercial applications. Recently, however, government agencies, research organizations, and academic institutions have begun to recognize the importance of examining the potential benefits and obstacles of thorium reprocessing in currently operating reactors, along with the prospects for fourth-generation thorium-based power plants [

21].

Table 1.

Assessment of thorium reserves in the world (upper estimate) [

11].

Table 1.

Assessment of thorium reserves in the world (upper estimate) [

11].

| Country |

Th reserves (kt) |

Country |

Th reserves (kt) |

| Brazil |

1300 |

Canada |

172 |

| Turkey |

880 |

Russia |

155 |

| India |

846 |

South Africa |

148 |

| Australia |

521 |

China |

100 |

| US |

434 |

Greenland |

93 |

| Norway |

430 |

Kazakhstan |

50 |

| Egypt |

380 |

Other countries |

1781 |

| Venezuela |

300 |

Worldwide |

7590 |

Most naturally occurring thorium is Th-232, a conditionally fissile material. Although it cannot sustain a chain reaction on its own, it can contribute to energy production in specific reactor configurations, even with limited self-shutdown capability [

15]. Thorium resources are typically found as ThO₂, ThSiO₄, or within monazite sands [

27].

Thorium dioxide (ThO₂) possesses favorable thermal properties: it is chemically stable, has higher thermal conductivity than UO₂, and performs advantageously in PWR-type reactors [

7]. For a given power output, ThO₂ fuel achieves higher operating temperatures than UO₂, resulting in improved thermal efficiency. ThO₂ also exhibits lower thermal expansion coefficients than UO₂, reducing mechanical stress when paired with Zircaloy cladding [

20]. This compatibility minimizes the “pre-contact” gap and lowers the risk of cladding swelling during irradiation.

The United States possesses roughly one-third of the world’s reserves of monazite and other ores suitable for thorium extraction. Historically, large quantities of thorium were refined by industry alongside both pure and so-called “impure” uranium. This process yielded relatively small amounts of high-grade uranium which, when combined with industrial-grade thorium, produced an effective thorium product. Yet the use of thorium in the nuclear weapons program significantly delayed its commercial deployment, despite the accumulation of extensive expertise and technical knowledge in thorium processing [

26].

Thorium-232 is an actinide element (atomic number 90), a fertile material capable of absorbing thermal neutrons with variable behavior across the neutron spectrum [

16]. Because the formation of fissile nuclei from actinide isotopes often requires multiple neutron captures, and because actinides typically yield an average of one neutron per capture, neutron absorption does not always result in fission [

28].

The microstructure of ThO₂ fuel-including its face-centered cubic lattice, homogeneous particle distribution, and lamellar morphology - appears to hinder the formation and outward migration of oxide layers, thereby delaying stress corrosion cracking (SCC) [

6]. With a melting point significantly higher than that of UO₂ (about 330°C above), ThO₂ also enhances safety margins under accident scenarios such as unprotected loss-of-flow (ULOF) events in spent fuel pools [

10].

These advantages have been confirmed through comparative irradiation experiments dating back to the 1960s, where ThO₂-based fuels outperformed UO₂ under identical conditions [

13]. Recent tests further demonstrated that fuel rods with uniform, fine-grained ThO₂ structures exhibit superior performance [

22]. Burnup levels for thorium-based fuels have exceeded those of conventional UO₂: ~200 GWd/t for UO₂, ~500 GWd/t for (Th-U) O₂, and up to ~800 GWd/t for (Pu-U) O₂ [

19]. Although higher burnup can increase the risk of SCC in cladding, experimental data and modeling have shown that ThO₂ fuels retain favorable mechanical integrity [

1].

Extensive R&D, including prototype irradiation campaigns and computational studies, particularly within the Canadian CANDU program, has demonstrated the technical viability of ThO₂ fuels and provided a substantial body of experimental and theoretical evidence to support their use [

24].

Thorium itself is not fissile; it must be irradiated in a reactor to eventually produce uranium-233, which is fissile. However, the thorium fuel cycle also generates uranium-232, an isotope that complicates fuel handling and raises proliferation resistance due to its strong gamma emissions, especially from Tl-208 and Bi-212. These radiations pose significant challenges for both safety and materials management.

Fuel irradiation strategies for thorium therefore differ from those applied to uranium. While thorium cycles yield fewer minor actinides, the presence of uranium-232 improves proliferation resistance but requires additional safeguards and handling measures.

In light-water reactors - the backbone of global nuclear power - thorium reprocessing and fuel fabrication can produce materials unsuitable for direct use in nuclear weapons, thereby strengthening nonproliferation goals. Nevertheless, successful implementation requires several conditions: reliable mechanical performance of thorium fuels, mature manufacturing technologies, and only minimal modifications to existing reactor systems.

The properties of thorium have been extensively studied, and its limitations in the thermal spectrum are well recognized: breeding fissile material from natural thorium alone is not feasible under thermal neutron conditions. The literature provides a broad basis for continued investigation, covering not only technical issues such as waste disposal, U-233 management, and isotopic behavior, but also policy concerns related to nonproliferation.

Studies show that plutonium isotopes can be effectively conserved within thorium-based cycles. While the processing and disposal of U-233 present challenges, especially due to the accumulation of long-lived daughter isotopes from U-232 decay (such as Th-228 and Ra-224), these challenges are considered manageable. Moreover, careful core design and fuel management strategies - such as employing seed-and-blanket configurations - can maximize the utility of U-233 bred in situ, improving both performance and fuel economy [

21].

3. DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS FOR THOURIUM REACTORS

Thorium has become increasingly recognized as a crucial component in the long-term energy strategies of several nations involved in nuclear reactor development [

21]. In this regard, various scenarios have been proposed to evaluate the thorium fuel cycle, covering aspects such as reactor design, production facilities, and reprocessing capabilities. Numerous thorium fuel cycle systems have been designed, especially in countries that operate both pressurized water reactors (PWRs) and fleets of combined PWR-heavy water reactors (HWRs), where the use of thorium has been suggested as a means to prolong reactor lifespans. The selection of reactor designs is shaped not only by the fertile characteristics of thorium and the associated fuel technologies, but also by a wider range of considerations, including the type of reactor, the scale of the installation, and the surrounding political and strategic context. Thorium has frequently been regarded as a fertile and reliable candidate for implementation in large-scale light water reactor (LWR) cycles. Several designs of PWRs have been constructed that can be adapted for the recycling of thorium. In Canada, CANDU-type reactors continue to be central to the nuclear program, transitioning from conventional single-cycle fuels based on uranium enrichment to self-sustaining thorium fuel cycles, a change facilitated through modifications to the fuel channels. Meanwhile, in Japan, a number of thorium-compatible designs, including high-temperature gas-cooled reactors, have been proposed.

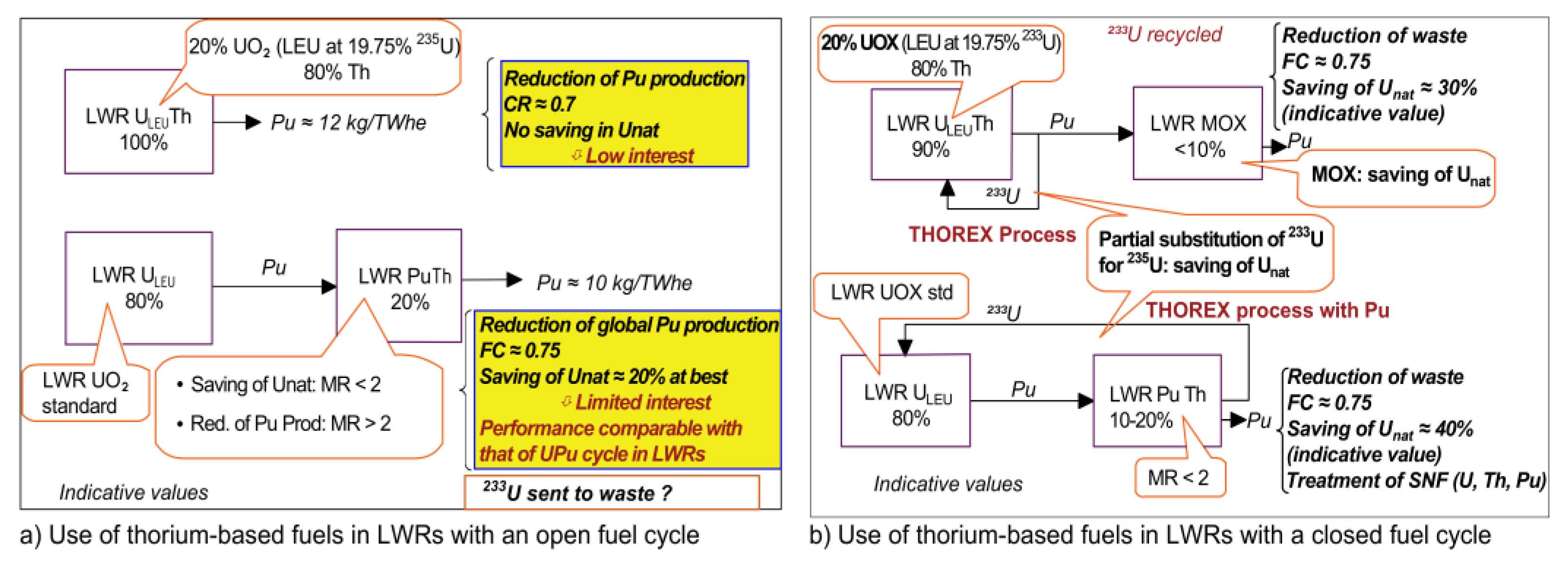

Figure 2.1.

Thorium-based fuels in Light Water Reactors: (a) open fuel cycle; (b) closed fuel cycle with THOREX reprocessing [

14].

Figure 2.1.

Thorium-based fuels in Light Water Reactors: (a) open fuel cycle; (b) closed fuel cycle with THOREX reprocessing [

14].

A. Reactor Types: Solid-Fuel, Liquid-Salt, and Accelerator Systems

The complementary approaches for incorporating thorium into LWRs are illustrated in

Figure 2.1a and 2.1b. In the open fuel cycle (a), thorium dioxide acts as a partial substitute for uranium, which not only reduces the generation of plutonium but also delivers modest improvements in fuel utilization. A comparable fuel strategy has been successfully employed in HWRs, using mixtures containing approximately 5% low-enriched uranium (19.75% ²³⁵U) and around 95% thorium. Though this approach offers significant benefits, the overall reduction in the demand for natural uranium remains limited. In contrast, in the closed cycle (b), reprocessing through the THOREX method enables partial recycling of ²³³U. This process permits a greater degree of uranium replacement, contributes to waste minimization, and can achieve savings of up to 40% in natural uranium compared to standard UOX cycles. The production of plutonium is also further curtailed, although the extent of these advantages is highly dependent on the maturity of the reprocessing technologies deployed. Together, these two strategies illustrate a pathway that progresses from relatively straightforward substitution schemes to more sophisticated closed cycles characterized by elevated efficiency at increased technical complexity.

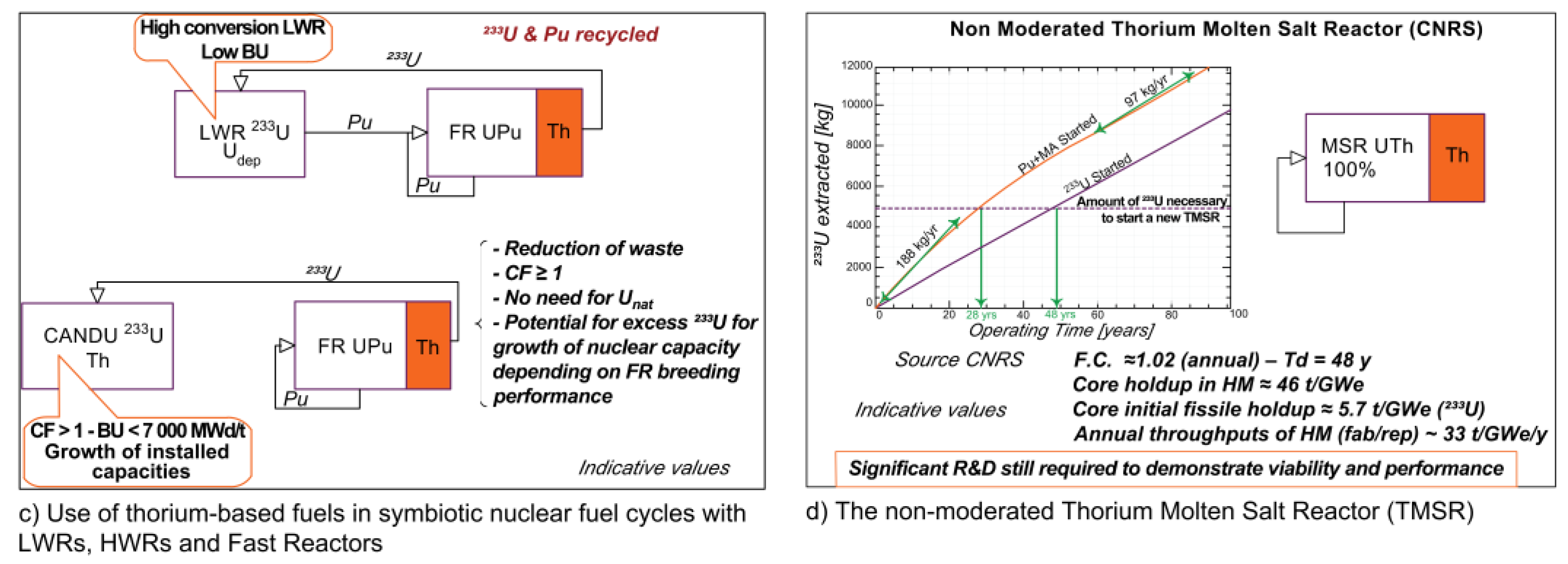

Figure 2.2c and 2.2d present advanced thorium strategies extending beyond conventional LWR cycles. In the symbiotic configuration (c), Fast Reactors (FRs) and HWRs are coupled to recycle both ²³³U and plutonium, thereby ensuring continuous fuel sustainability while reducing the need for additional natural uranium. This cycle can also generate excess ²³³U to support growth in nuclear capacity, emphasizing thorium’s role as a fertile material of long-term significance.

Figure 2.2.

Advanced thorium fuel cycles: (c) symbiotic FR-HWR system; (d) non-moderated Thorium Molten Salt Reactor (TMSR) [

8].

Figure 2.2.

Advanced thorium fuel cycles: (c) symbiotic FR-HWR system; (d) non-moderated Thorium Molten Salt Reactor (TMSR) [

8].

The molten salt reactor (MSR) concept (d), especially the non-moderated design proposed by CNRS, illustrates a more innovative application of thorium. By utilizing liquid thorium fuel, MSRs enable continuous reprocessing and effective actinide management, with conversion ratios above unity and substantial fissile retention. However, extensive R&D is still required to validate technical feasibility and ensure safety. Together, these designs reflect recent advances in thorium fuel cycle research, combining system-level sustainability with transformative reactor concepts. The CNRS report highlights molten salt reactors with thorium fuel as a promising option for safety and sustainability, but also notes unresolved challenges in materials science, reprocessing, and large-scale deployment [

26].

The global effort to transition toward low-carbon energy and reduce greenhouse gas emissions has intensified interest in advanced nuclear technologies, including thorium reactors, high-temperature systems, and hybrid concepts [

13,

21]. While thorium provides advantageous physicochemical properties, significant challenges persist, including the need for progress in nuclear science, development of supporting infrastructure, and training of specialized personnel. For developing countries, the construction and safe operation of thorium reactors represent substantial barriers. A critical evaluation is required to identify feasible and cost-effective pathways while maintaining strict safety standards. Current thorium reactor concepts concentrate on solid-fuel, liquid-salt, and accelerator-driven systems. Within this framework, neutronic simulations using tools such as SCALE-6.0 and MATLAB provide essential insights for design optimization.

B. Molten Salt Reactors

Molten Salt Reactors (MSRs) constitute a distinct class of advanced nuclear systems in which the fissile and fertile nuclides are dissolved in a high-temperature molten salt that simultaneously serves as fuel carrier and primary heat-transfer medium. Typical carrier salts for thermal-spectrum MSR concepts include fluoride mixtures such as LiF-BeF₂ (FLiBe) and LiF-NaF-KF (FLiNaK), while chloride salts have been investigated for fast-spectrum variants due to their favorable neutronic properties and higher solubility for actinides [

29].

MSRs’ liquid-fuel architecture enables continuous on-line chemical processing - volatile and noble fission products can be removed (e.g., by gas sparging and off-gas systems) and certain transmutation/cleanup steps (notably timed separation of protactinium-233 in thorium cycles) can be performed to improve breeding performance and neutron economy, thereby reducing the accumulation of long-lived minor actinides relative to many solid-fuel cycles [

30].

Because fuel and heat transport occur in a single phase, MSRs operate at elevated outlet temperatures (typical design ranges 600-800 °C for thermal concepts and higher for some advanced designs) while remaining at near-atmospheric or modest pressures, which increases thermodynamic efficiency and lowers mechanical and containment loading compared with high-pressure water reactors [

31]. From a safety standpoint, many MSR concepts incorporate favorable reactivity feedbacks and passive features (for example, freeze-plug drain tanks that passively drain fuel salt into subcritical storage in case of off-normal conditions), but these passive traits coexist with distinctive technological challenges.

Figure 3.

A schematic representation of a thorium ADS [

21,

14].

Figure 3.

A schematic representation of a thorium ADS [

21,

14].

Among the principal technical barriers are high-temperature corrosion and mass-transfer phenomena in fluoride/chloride environments and the consequent need for qualified structural materials (historically Hastelloy-N and other nickel-based alloys, and more recently modified Ni-Mo alloys, ODS steels and protective coatings are under study), as well as issues of radiation damage, tritium production and containment, and the engineering of reliable online chemical processing and off-gas systems [

32].

The Molten-Salt Reactor Experiment (MSRE) at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in the 1960s remains the canonical experimental dataset for circulating salt behavior, freeze-seal drainage, and basic neutronic/thermal performance, and its operational experience continues to inform modern design choices and safety analyses [

33]. Finally, renewed international interest has driven a broad portfolio of demonstration and pilot efforts -ranging from academic and national-lab studies to national programs (notably the Chinese TMSR program and prototype chains) and industrial proposals - focused on validating materials, fuel-processing flowsheets, and licensing approaches needed to transition MSRs from demonstrators toward commercial deployment [

34].

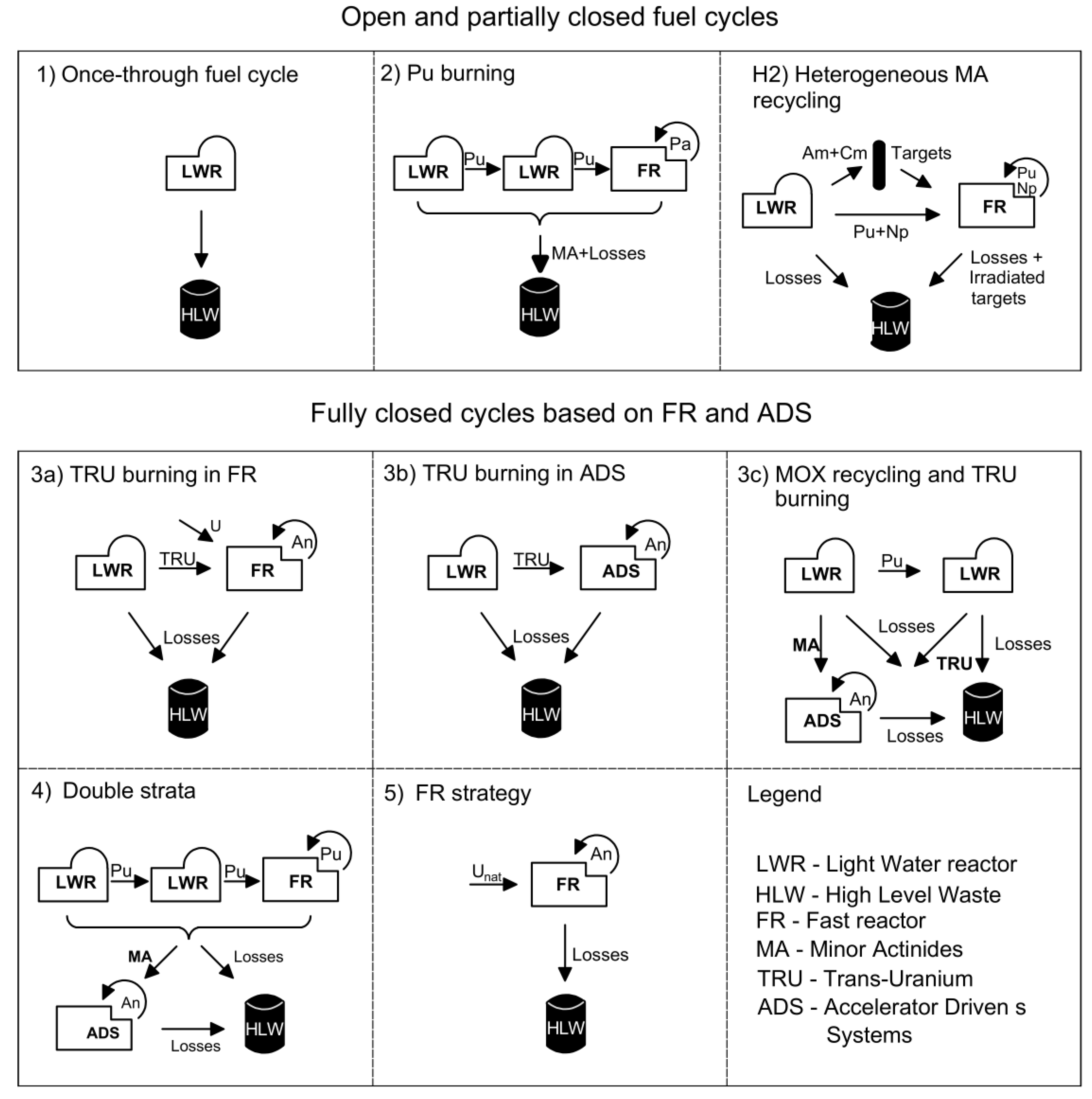

C. Fuel cycle and recycling methods

Light-water reactors (LWRs), commissioned during the 1970s and 1980s in several advanced nuclear-manufacturing countries, expanded rapidly but have now reached a plateau of saturation. Some developing countries are only beginning to initiate nuclear power plant (NPP) projects, while industrialized nations are re-examining their nuclear strategies to address issues such as high capital costs, extended construction timelines, and nonproliferation requirements. Furthermore, as many LWRs approach decommissioning, these nations face the necessity of a comprehensive reassessment of advanced fuel cycles. One promising avenue is the transmutation of minor actinides (MA).

Figure 3 presents the concept of accelerator-driven systems (ADS), while

Figure 4 illustrates the potential of closed fuel cycles that integrate fast reactors and ADS [13, 8].

Practical solutions from a nuclear physics perspective have been proposed, including the use of depleted uranium (DU) in advanced PWR designs that can incorporate thorium as fuel, thereby reducing dependence on natural uranium. In this context, the natural uranium equivalent (NUE) concept is applied to represent differences in fissile fuel utilization. The design also features enlarged fuel rod dimensions to extend refueling intervals and achieve higher burnup.

In terms of reactor core configurations, selected conventional assemblies are replaced with two types of assemblies, a seed and a blanket. This arrangement helps to conserve fissile material before significant breeding occurs. Additionally, dry reprocessing methods have been proposed to avoid plutonium separation, as well as the use of zirconium alloys modified for improved cladding performance.

In the fuel industry, U-Pu-Zr alloy fuel is fabricated as mini-tablets enclosed in seamless cladding produced from advanced zirconium alloys. Irradiation testing evaluates temperature distribution in fuel assemblies during initial thorium loading and assesses thermohydraulic behavior in a multiplying core [

13].

4. NUCLEAR FUEL PARAMETERS

The essential parameters of nuclear fuel are outlined when the fuel is natural or depleted uranium, whether or not it contains thorium. For each component, a specific parameter for natural uranium fuel (Uranium; pure ThO₂) and a corresponding deviation from its value are identified. The foundational description of an Advanced Heavy Water (AHD) or CANDU reactor using conventional uranium fuel is provided.

For UO₂ fuels, these parameters encompass burnout-dependent swelling, which influences the fuel's thermal conductivity and its capacity to sustain stable heat transfer during operation. This swelling is crucial as it not only affects thermal conductivity but also the mechanical contact between fission fragments and the fuel gas, impacting fuel integrity throughout the cycle. Indeed, UO₂ and other conventional fuels exhibit significant burnout-dependent swelling that directly affects the assemblies' structural and mechanical behavior. All conventional nuclear fuels also grapple with excessive power density in regions of high local heat flux. Besides incorporating a safe-class neutron absorber into the fuel, the primary effective strategy for mitigating this excessive power density is to lower the peak heat release rate [

5]. Throughout the years, numerous methods have been proposed to address these limitations for new fuels; this section focuses specifically on approaches directly tied to the fuel's intrinsic properties.

In nearly all analyses conducted thus far on using thorium in fission reactors, a conclusion has emerged: a higher degree of uranium enrichment than the standard 5% is necessary. This stems from the thorium fuel cycle's requirement for an external fissile driver, rendering enrichment beyond common thresholds relevant. Even in the most advanced nuclear countries, the maximum enrichment degree typically reaches only around 4%, and given uranium's abundant natural availability, procuring enriched uranium containing approximately 4% ²³⁵U is usually feasible. This option offers a critical advantage over higher enrichment requirements.

In producing countries, allowable uranium enrichment levels in autoclaves remain relatively low, subsequently affecting fuel assembly operation. Such fuel assemblies are expected to function for 3-4 years, during which the effective uranium enrichment in the blocks diminishes. At these comparatively low enrichment levels, thorium's application in fission reactors appears more viable, particularly in PWR reactors that demonstrate stable performance under such conditions.

Figure 4.

The possibility of implementing a closed fuel cycle in the case of Fast Reactors and ADS (Accelerator Driven Systems) [

21,

13].

Figure 4.

The possibility of implementing a closed fuel cycle in the case of Fast Reactors and ADS (Accelerator Driven Systems) [

21,

13].

CANDU reactors present a distinct advantage over LWRs by enabling online refueling. As the CANDU reactor slows neutrons and utilizes heavy water for cooling, the plutonium generated within the reactor produces fissile uranium through neutron capture. The reproduction of fissile isotopes in this context occurs via two pathways when employing this new reactor fuel type. The initial fissionable cycle relies on the reproduction of ²³⁸U → ²³⁹Pu, complemented by approximately 4% PuO₂ that forms directly within the reactor. The second reproduction cycle encompasses the production of ²³²Th → ²³³U, multiplied by the internal ²³⁸U present in the dissolver reactor fuel. If the average lifetime of neutrons in these fissile assemblies can be extended by roughly one-sixth compared to current configurations, significant improvements in neutron economy and breeding performance of the considered fuel grid will be achieved.

Thorium is more abundant in nature than uranium, possesses a higher energy content per unit mass, and is easier to exploit in large deposits, collectively facilitating widespread deployment of nuclear power based on this fuel. A recent paper provides a thorough overview of developed schemes and ongoing research endeavors in this domain. Notably, the author extends the investigation to pressurized heavy water reactors (PHWRs), underscoring their potential as promising candidates for thorium utilization.

Section 2 of that study presents a detailed technical description of the PHWR, outlining its structural layout and operating principles while emphasizing the nuclear and physical constraints placed on fuel burnout and the possibility of incorporating thorium into various reactor configurations.

Section 3 further explores the commercialization of PHWR technology, indicating that while several countries currently enhancing their nuclear capacity are still contemplating the adoption of PHWRs, established nuclear-producing nations generally do not prioritize this option.

Section 4 subsequently examines, based on the previously provided technical description, the specific restrictions required for fuel and reactor design. In these configurations, the fuel bundle is sealed within a stainless steel vessel filled with high-purity helium gas that circulates through the central channel of the fuel rod. The central core itself contains a carefully mixed composition of thorium and uranium. Control rods are situated in the primary channels, and four calendared tubes support operation -two filled with a deuterium moderator and two functioning as transverse shielding tubes. All major components are constructed from stainless steel, which inevitably undergoes irradiation embrittlement over time, necessitating periodic replacement. The PHWR design incorporates a heavy-water moderator, while the remainder of the reactor resides within the end deflector. Movable shielding plugs are employed to secure the spent fuel bundles after their discharge from the reactor, ensuring safety and facilitating handling.

5. FEASIBILITY STUDIES OF THORIUM-BASED MOLTEN SALT REACTOR SYSTEMS

Feasibility studies for thorium-based and molten-salt reactor (MSR/TMSR) concepts must adopt an integrated, multi-disciplinary approach that couples advanced neutronic and multi-physics thermal-hydraulic modelling with targeted experimental campaigns, materials qualification, and detailed systems-level engineering of primary and secondary salt circuits and auxiliary systems [

34]. At the core of technical feasibility are (i) validated multiphysics calculations that resolve coupled neutronics-thermal hydraulics-chemistry behavior for proposed core and salt-processing layouts; (ii) corrosion and radiation-damage testing of candidate structural alloys under representative salt chemistry, temperature and neutron flux conditions; and (iii) demonstration of reliable online salt chemistry control, off-gas handling and fission-product removal flowsheets that permit predictable reactivity management and acceptable waste streams [

36]. From an economic and deployment perspective, independent studies consistently identify FOAK capital expenditure, materials qualification costs, and the cost and schedule of fuel-processing facilities as the dominant drivers of leveled cost of electricity (LCOE) and investor risk, with wide LCOE sensitivity to assumptions on cost of capital, modular manufacturing learning rates and commercialization schedules. Practical feasibility assessments therefore combine probabilistic cost-risk analyses and learning-curve scenarios with site-specific market studies; these assessments show that while favorable scenarios can place MSR/TMSR LCOE in a competitive range, such outcomes remain conditional on demonstrable reductions in FOAK premiums and verified manufacturing scale-up [

35]. Important near-term demonstration pathways identified across the literature include niche or hybrid applications (Mo-99 and other medical radioisotope production, high-temperature process heat, and hydrogen cogeneration), which can reduce market risk and accelerate accumulation of operational experience before large-scale electricity deployment [

37]. On fuel-cycle and safeguards issues, sensitivity and modelling studies underline that effective Th-U breeding in liquid-salt systems depends critically on protactinium-233 management (timely chemical separation or isolation) and on efficient removal of key fission products; these process steps improve breeding performance but introduce additional chemical-engineering and safeguards requirements that must be validated in demonstration facilities [

19].

Finally, authoritative reviews and international roadmaps advocate that credible feasibility programs must integrate (a) high-fidelity multi-physics simulation, (b) representative loop-scale materials and chemistry testing, (c) small-scale pilot/demonstration reactors (building on MSRE operational lessons), and (d) early, sustained engagement with regulatory authorities to develop licensing pathways and independent cost validation - only such a combined program can realistically quantify technical risk, schedule, and total lifecycle cost prior to commercial roll-out. In practical engineering applications, bleed air has been introduced into the outlet gas of the core to maintain constant total pressure. To analyze such designs, heat exchanger models were implemented using dedicated simulation software. As thermophysical databases improved, additional models were created that excluded “pure salt” pretreatment systems and relied on updated salt-property libraries. These models were subsequently applied to evaluate the feasibility of heat exchangers, their geometric dimensions, and their integration into the reactor system. Notably, the results directly influenced key design considerations. At full capacity, approximately 500 MW of thermal energy is removed from the FHR primary circuit by a tertiary salt-based loop. This energy is transferred through intermediate heat exchangers (IHX) to heat air flows up to ~1200 °C before controlled discharge into the environment, ensuring both efficiency and safety.

Molten-salt coolants have therefore been investigated as alternatives, offering favorable neutronic and thermal properties. Programs such as the Molten Salt Reactor Experiment (MSRE) tested uranium-fueled systems with salt coolants and provided valuable insights into liquid-salt thermodynamics. Current studies extend this work to thorium-fueled assemblies, analyzing neutron balance by calculating homogenized cross-sections across relevant density, temperature, and energy groups. These calculations characterize the neutron multiplication of heavy nuclei in fast and resonance ranges and inform predictions of reactor core criticality under operating conditions.

6. NEUTRON SOURCES IN THORIUM REACTORS

Accelerator-driven subcritical (ADS) systems can employ two principal categories of neutron sources. The first consists of compact external sources, such as UF₄ block matrices irradiated by pulsed proton beams from electrostatic accelerators located outside the target zone. The second type involves volumetric fission sources, such as heavy tantalum or lead reflector-target assemblies, in which spiral proton beams are directed perpendicularly to the vertical axis of the subcritical core.

The neutron intensity of fission sources can be significantly enhanced, more than doubling, by surrounding the tantalum target with a paraboloid-shaped lead reflector. This configuration also allows for the separation of moderator and reflector zones, reducing neutron intensity losses typical of cylindrical-shell chambers. In this design, repeated neutron reflections yield a sufficiently large high-density neutron volume, improving the efficiency of the subcritical system [

21].

Alternative conceptual designs suggest hybrid reactor cores, incorporating separate uranium and thorium zones, to optimize criticality and ensure stability. Monte Carlo simulations remain essential for evaluating these designs, while experimental verification is necessary for eventual deployment.

Parallel developments in ARC-class fusion neutron sources demonstrate their potential for transmuting transuranics (TRU) and producing tritium. These sources are designed for modest thermal powers of ~2 GW but involve complex requirements for blanket materials enriched with ⁶Li. Calculations indicate that tritium breeding ratios above 0.8 are necessary, implying ⁶Li enrichment levels exceeding 85%. While such enrichment enhances breeding, it also raises proliferation and safety challenges [

22].

7. CONCLUSION

Compact square-core reactors, although preferred by industry for their structural efficiency, exhibit limitations regarding control rod performance. Small gap areas in the corners of control rod placements influence reactivity behavior, increasing values in ways that can compromise safety. For instance, TRIGA reactors using cylindrical fuel cells reveal that current control rod designs fail to achieve optimal reactivity with sufficient safety margins.

One proposed solution involves mixing ²³²Th with ²³⁵U to reduce reactivity excursions and shorten emergency release durations. An equally important consideration concerns the reprocessing of discharged thorium-based fuel.

With the global demand for light-water reactors continuing to rise, safer and more cost-effective reactor concepts are attracting increased attention. While Gen I and Gen II PWRs still dominate, new Gen III+ systems such as the EPR, designed by the French company Areva, are projected to spread internationally by 2030. These advanced systems typically feature underground siting and multi-layer containment barriers. Many Gen I and Gen II technologies remain codified in IAEA standards, while the EPR represents a benchmark in advanced PWR design.

The present study seeks to outline the feasibility of fast thorium reactors for medium-term power generation. ThO₂ fuel systems are widely recognized for their strategic advantages, especially in advanced actinide fuel fabrication, which opens new industrial opportunities.

The production of (Th-U)O₂ fuel assemblies is considered within this framework, presenting challenges but also a strong rationale for continued development. Two main industrial approaches are under discussion: closed-chain reprocessing of direct cores and the use of inert matrix fuels (e.g., Zr-based) for actinide burning. Each pathway raises distinct nuclear-physics issues, necessitating coordinated technical, political, and sociological strategies for managing spent fuel, promoting nuclear development, and enhancing proliferation resilience.

Advancing the development of innovative modular thorium reactors in nuclear producing countries requires targeted efforts that address both technical and organizational challenges. Priority should be given to resolving critical nuclear-physics problems associated with thorium fuel cycles and to strengthening the training of highly qualified specialists in reactor physics and nuclear engineering. Educational programs must be closely linked with the development and verification of advanced computer codes for simulating modular thorium systems and fast-spectrum research reactors, thereby ensuring reliable tools for design and safety assessment.

International cooperation, including joint initiatives such as TWSFR, would significantly enhance the capacity of producing countries to evaluate complex reactor projects. Equally important is the application of rigorous statistical methods in nuclear calculations and the systematic validation of results through experimental studies. Particular attention should be paid to the development of online diagnostic systems capable of monitoring fuel and blanket conditions under irradiation, as well as environmental impacts and nonproliferation requirements.

By combining computational modeling, field research, and coordinated training, producing countries will be better prepared to implement innovative modular thorium reactors as a viable element of their future energy strategies.

Author Contributions

Z. Insepov: Supervision, Project administration, Writing - Original draft preparation; A. Hassanein: Project administration, Resources; Z.A. Mansurov: Validation, Formal analysis; A. Gajimuradova: Software, Formal analysis; Zh. Alsar: Investigation, Resources. The final manuscript was read and approved by all authors.

Funding

The work was funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (PTF No. BR24993225).

Acknowledgments

This study was carried out as part of the implementation of the scientific program of the IRN BR24993225 for program-targeted financing of the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2024-2026.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in relation to this research, whether financial, personal, authorship or otherwise, that could affect the research and its results presented in this paper.

References

- J. R. Maiorino, F. D’Auria, and A. J. Reza, “An overview of thorium utilization in nuclear reactors and fuel cycle,” Proc. 12th Int. Conf. Croatian Nucl. Soc., pp. 1–15, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://arpi.unipi.it/handle/11568/941628.

- R. Dwijayanto, A. Putra, F. Miftasani, and A. W. Harto, “Assessing the benefit of thorium fuel in a once-through molten salt reactor,” Prog. Nucl. Energy, vol. 176, Art. no. 105369, 2024.

- A. Rummana, “Spallation neutron source for an accelerator driven subcritical reactor,” Ph.D. dissertation, Univ. Huddersfield, 2019. Available: https://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/35075/.

- R. K. Jyothi et al., “An overview of thorium as a prospective natural resource for future energy,” Front. Energy Res., vol. 11, Art. no. 1132611, 2023.

- A. Rummana, R. J. Barlow, and S. M. Saad, “Calculations of neutron fluxes and isotope conversion rates in a thorium-fuelled MYRRHA reactor, using GEANT4 and MCNPX,” Nucl. Eng. Des., vol. 388, Art. no. 111629, 2022.

- B. Hombourger, “Conceptual design of a sustainable waste burning molten salt reactor,” Ph.D. dissertation, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, 2018. Available: https://infoscience.epfl.ch/entities/publication/19d9a7cb-ad3a-44cf-be60-7c655e60deb4.

- J. R. Maiorino, F. D’Auria, G. L. Stefani, and R. Akbari, “The utilization of thorium-232 in advanced PWR—from small to big reactors,” Proc. V Int. Sci. Tech. Conf. Innovative Designs and Technologies of Nuclear Power, pp. 219–233, 2018. Available: https://arpi.unipi.it/handle/11568/941759.

- D. Hejazi et al., “The small modular molten salt reactor potential and opportunity in Saudi Arabia,” Nucl. Eng. Technol., vol. 57, no. 2, Art. no. 103203, 2025.

- R. Gao et al., “Performance modeling and analysis of spent nuclear fuel recycling,” Int. J. Energy Res., vol. 39, no. 15, pp. 1981–1993, 2015.

- E. Parent, Nuclear Fuel Cycles for Mid-Century Development, M.S. thesis, Massachusetts Inst. Technol., 2003. Available: http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/17027.

- J. R. Maiorino and J. M. Moreira, “Recycling and transmutation of spent fuel as a sustainable option for nuclear energy development,” J. Energy Power Eng., vol. 8, no. 10, pp. 1505–1510, 2014.

- V. Sobolev et al., “Modelling the behavior of oxide fuels containing minor actinides with urania, thoria and zirconia matrices in an accelerator-driven system,” J. Nucl. Mater., vol. 319, pp. 131–141, 2003.

- Gen IV Int. Forum, “Use of thorium in the nuclear fuel cycle: How should thorium be considered in the GIF?,” OECD, Dec. 22, 2010. Available: https://www.gen-4.org/gif/upload/docs/application/pdf/2013-10/gif_egthoriumpaperfinal.pdf.

- IAEA, Nuclear Fuel Cycle Simulation System (VISTA), IAEA-TECDOC-1535, 2007. Available: https://www-pub.iaea.org/MTCD/Publications/PDF/te_1535_web.pdf.

- E. R. Johnson and R. E. Best, Systems Analysis of an Advanced Nuclear Fuel Cycle Based on a Modified UREX+ 3c Process, Rep. DOE/ID/14922, JAI Corp., 2009.

- F. D’Auria, “Nuclear fission: From E. Fermi to Adm. Rickover, to industrial exploitation, to nowadays challenges,” Adv. Sci. Eng. Res., vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 17–30, 2019.

- J. Ball, E. Peterson, R. Kemp, and S. Ferry, “Assessing the risk of proliferation via fissile material breeding in ARC-class fusion reactors,” Nucl. Fusion, vol. 65, no. 3, 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. C. Renteria, J. A. Schwartz, and J. D. Jenkins, “Evaluating advanced nuclear fission technologies for future decarbonized power grids,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.15491, 2024.

- A. Chroneos, I. Goulatis, A. Daskalopulu, and L. H. Tsoukalas, “Thorium fuel revisited,” Prog. Nucl. Energy, vol. 164, Art. no. 104839, 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Travis, “An effective methodology for thermal-hydraulics analysis of a VHTR core and fuel elements,” Ph.D. dissertation, Univ. New Mexico, 2013. Available: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ne_etds/30.

- OECD Nuclear Energy Agency, Introduction of Thorium in the Nuclear Fuel Cycle: Short- to Long-Term Considerations, NEA No. 7224, OECD Publishing, 2015.

- A. A. Kalybay, B. Kurbanova, Z. A. Mansurov, A. Hassanein, Z. Alsar, and Z. Insepov, “Mathematical models of the active zone of a thorium reactor,” Combust. Plasma Chem., vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 279–295, 2024. [CrossRef]

- U. E. Humphrey and M. U. Khandaker, “Viability of thorium-based nuclear fuel cycle for the next generation nuclear reactor: Issues and prospects,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 97, pp. 259–275, 2018.

- CNRS, Thorium Cycle—Molten Salt Reactors: The CNRS Research Program on the Thorium Cycle and the Molten Salt Reactors, CNRS, 2008.

- A. Ghasemi, A. Pirouzmand, and S. Kamyab, “Investigation of core meltdown phenomena and radioactive materials release in VVER-1000/V446 nuclear reactor at severe accident condition due to LBLOCA along SBO,” Int. J. Energy Res., vol. 44, no. 10, pp. 8113–8124, 2020.

- S. Şahín, K. Yıldız, M. Şahin, and A. Acır, “Investigation of CANDU reactors as a thorium burner,” Energy Convers. Manage., vol. 47, nos. 13–14, pp. 1661–1675, 2006.

- M. Popović, M. Bolind, C. Cionea, and P. Hosemann, “Liquid lead-bismuth eutectic as a coolant in generation IV nuclear reactors and in high temperature solar concentrator applications: Characteristics, challenges, issues,” Contemp. Mater., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 20–34, 2015. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321397668.

- Z. Insepov, A. A. Kalybay, Z. A. Mansurov, B. T. Lesbaev, A. Hassanein, and J. Alsar, “Nuclear-chemical characteristics of subcritical thorium reactors with an external neutron source: A review,” Combust. Plasma Chem., vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 297–308, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Wu et al., “A review of molten salt reactor multi-physics coupling models and development prospects,” Energies, vol. 15, no. 21, Art. no. 8296, 2022; R. Roper et al., “Molten salt for advanced energy applications: A review,” Ann. Nucl. Energy, vol. 169, Art. no. 108924, 2022.

- H. B. Andrews et al., “Review of molten salt reactor off-gas management considerations,” Nucl. Eng. Des., vol. 385, Art. no. 111529, 2021.

- A. Ho et al., “Exploring the benefits of molten salt reactors: An analysis of flexibility and safety features using dynamic simulation,” Digit. Chem. Eng., vol. 7, Art. no. 100091, 2023.

- K. K. Sandhi and J. Szpunar, “Analysis of corrosion of Hastelloy-N, Alloy X750, SS316 and SS304 in molten salt high-temperature environment,” Energies, vol. 14, no. 3, Art. no. 543, 2021.

- P. N. Haubenreich and J. R. Engel, “Experience with the molten-salt reactor experiment,” Nucl. Appl. Technol., vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 118–136, 1970.

- Y. Liu et al., “Sensitivity/uncertainty comparison and similarity analysis between TMSR-LF1 and MSR models,” Prog. Nucl. Energy, vol. 122, Art. no. 103289, 2020.

- B. Mignacca and G. Locatelli, “Economics and finance of molten salt reactors,” Prog. Nucl. Energy, vol. 129, Art. no. 103503, 2020.

- V. Davis et al., Modeling 233Pa Generation in Thorium-Fueled Reactors for Safeguards, Argonne Nat. Lab., Rep. ANL/SSS-21/16, 2021.

- G. Zheng et al., “Feasibility study of thorium-fueled molten salt reactor with application in radioisotope production,” Ann. Nucl. Energy, vol. 135, Art. no. 106980, 2020.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).