1. Introduction

Culture has been a central force in shaping communities, building consensus, and driving the evolution of civilization since antiquity. Today, China operates within a global political order composed of nation-states. The nation-state and the nation-state system originated in modern Europe and subsequently spread worldwide alongside the expansion of Western European powers. In the contemporary globalized context, competition among nation-states,still the primary units of political allegiance[

1], has fundamentally transformed. This competition now encompasses not only traditional forms of hard power, such as economic, scientific, technological, and military capabilities, but also soft power elements, including national spirit and social cohesion. Within the broader narrative of globalization, culture has moved from a peripheral position to a central one. As John Tomlinson observed, “Globalization lies at the heart of modern culture, and cultural practices lie at the heart of globalization.”[

2] Scholars such as Hans Morgenthau, Joseph Nye, and Raymond Cline have long underscored the importance of national soft power. They argue that national morale, character, and collective will constitute crucial “soft” components of comprehensive national power, and that their relationship with hard power is not merely additive but multiplicative. Today, international competition has, in many cases, shifted from contests of hard power to rivalries of soft power centered on cultural attraction, value appeal, and national cohesion. Xi Jinping has emphasized that “the prosperity of culture is the prosperity of the nation, and the strength of culture is the strength of the nation,” aptly capturing culture’s fundamental significance for national survival and rejuvenation. In the current era—defined by accelerating globalization and digitization—culture has become not only a core indicator of a country’s soft power but also a frontier arena of geopolitical competition and the final line of defense for sustaining national identity. Against this backdrop, it is of considerable theoretical and practical importance to examine the internal operating mechanisms of a country’s cultural system, particularly the ways in which macro-level national will and the micro-level lived experiences of citizens shape one another.

This study conceptualizes this dynamic through the dialectical interaction between two core concepts: national culture and civic culture. Drawing upon Gramscian thought, national culture is defined as a consciously constructed, top-down cultural ensemble promoted by state and elite actors. It is inherently strategic, aiming to cultivate a unified identity and legitimize the prevailing political and economic order within a sovereign territory. Conversely, informed by theories of cultural consumption and cultural memory, civic culture refers to the bottom-up, lived culture of the populace. It emerges from everyday practices, shared symbols, consumption patterns, and collective memories, representing the spontaneous and resilient web of meanings that constitute the life-world of citizens. The central tension examined in this paper lies in how the hegemonic project of national culture is continuously negotiated, filtered, and reshaped by the dynamic and often unpredictable forces of civic culture. In this framework, national culture and civic culture correspond to the cultural expressions of macro-level national will and micro-level daily life, respectively. National culture is not “ethnic culture” in the traditional sense based on kinship or locality; rather, it is a consciously crafted cultural formation of the modern nation-state, rooted in sovereign territory, ecological conditions, political-economic systems, and core identity structures. As a typical “other-value-oriented cultural form,” it aims to consolidate individual energies into collective national strength. In contrast, civic culture is grounded in the everyday life practices of the people. It constitutes the shared cultural system of the national community, expressed through specific lifestyles, behavioral norms, consumption habits, and values. With its multilayered structure encompassing artifacts, institutions, behaviors, and mentalities, civic culture is more micro-oriented, practical, and spontaneous. A complex dialectical relationship exists between national culture and civic culture: national culture seeks to shape and guide civic culture through various mechanisms to achieve political integration and value unity; meanwhile, civic culture—with its strong resilience and vitality—selects, filters, adapts to, and at times resists the inculcation of national culture, thereby exerting a reverse influence on its formation and trajectory. Therefore, the core questions guiding this study are as follows: What are the internal mechanisms through which national culture and civic culture mutually transform and influence one another? And what new features and challenges characterize these mechanisms in an era in which digitization and globalization are deeply intertwined?

To analyze this dialectical process, our framework integrates two key theoretical lenses: Antonio Gramsci’s cultural hegemony and Jan and Aleida Assmann’s cultural memory. Gramsci’s theory illuminates the underlying power dynamics, showing that national culture operates not only through coercive means but also by securing the “voluntary consent” of the governed, thereby shaping society’s “common sense.” From this perspective, civic culture becomes the arena in which such consent is secured, contested, or withdrawn. Meanwhile, the Assmanns’ theory offers a lens for understanding the substantive content of this struggle by distinguishing between the fluid, everyday communicative memory of the populace and the formalized, state-endorsed cultural memory that constitutes the canon of national culture. The interplay between these two forms of memory is central to the construction of collective identity. By combining these two theoretical traditions, we are able to examine both the mechanisms of power and the substantive processes of identity formation within the nation-state.

While existing scholarship has offered extensive analyses of national culture (Hofstede, 1990)[

3] and civic culture (Almond & Verba, 1963) as distinct domains, a significant theoretical gap remains concerning their dynamic interaction. Much of the literature treats the two as largely static constructs or focuses primarily on one-way state imposition. Few studies have investigated the dialectical mechanisms through which national culture and civic culture mutually transform one another—particularly in the digital age, when bottom-up cultural forces have become increasingly visible and influential. This paper addresses this gap by positioning itself as a conceptual inquiry. It proposes a theoretical framework that explains how national culture and civic culture shape each other through mechanisms of hegemony and memory, and it illustrates the applicability of this framework through the case of contemporary China.

2. Methodological Framework

This study adopts a conceptual research approach supported by illustrative case analysis. Rather than conducting a quantitative empirical investigation, it aims to construct a theoretical model capable of interpreting the complex interaction between national culture and civic culture. The methodological framework is grounded in a critical synthesis of two core theories: Antonio Gramsci’s cultural hegemony, which explains top-down cultural construction—and Jan Assmann’s cultural memory—which illuminates bottom-up cultural resilience.

To anchor these theoretical concepts in empirical reality, the study employs a qualitative case study method focusing on contemporary China. The data sources are primarily secondary, including official policy documents (e.g., reports from the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television), digital-platform data reports (e.g., the Douyin Intangible Cultural Heritage Report), and observed cultural phenomena (e.g., Guochao). These materials are not used for statistical regression but serve as narrative evidence that illustrates the plausibility of the proposed theoretical mechanisms.

In terms of research methods, this study employs four complementary approaches: literature review, theoretical analysis, case study, and data analysis. First, the literature review provides the foundation for the entire inquiry. By systematically examining both classical and contemporary research on national culture (e.g., Hofstede; Wang Baoguo) and civic culture (e.g., Qin Dejun; Zhao Lifen), the study establishes a theoretical baseline, clarifies the contributions and limitations of existing scholarship, and defines the core research questions and analytical trajectory. Secondly, the theoretical analysis offers a framework for interpreting the mechanisms of interaction. For national culture, the study draws on Gramsci’s cultural hegemony and Althusser’s concept of the ideological state apparatus to analyze the top-down construction and penetration of national culture and its role in contemporary social practice. At the same time, Bourdieu’s notions of habitus and distinction, Baudrillard’s theory of consumption, and Jan Assmann’s theory of cultural memory are employed to explain the bottom-up reproduction and feedback mechanisms that shape civic culture. Thirdly, the case study method integrates theoretical discussion with contemporary Chinese cultural practices. The digital transformation of online platforms, the rise of Guochao (China-chic), the culture of the fan circle and the "Qinglang" campaign, and online discourses surrounding "involution" and "lying flat" serve as typical cases through which the new forms and challenges of national–civic cultural interaction in the digital age are examined. Finally, the data analysis method provides quantitative support for the study. Data from the National Reading Survey, cable television subscription statistics, Internet user metrics, the scale of the digital creative industry, and Douyin’s intangible cultural heritage dissemination figures are used to demonstrate macro-level trends in cultural production, dissemination, and consumption.

Jan Assmann’s theory of cultural memory provides a foundational framework for understanding how collective pasts are constructed and preserved. Assmann draws a crucial distinction between communicative memory and cultural memory. The former is rooted in everyday interaction and oral transmission, typically limited to a shifting horizon of three to four generations. In contrast, cultural memory is defined as "objectivized culture," consisting of texts, images, rituals, architecture, and monuments that endure beyond the biological lifespan of individuals (Assmann, 1995). As Assmann (2011) notes, cultural memory functions as a "connective structure" that binds a society together. It does not simply record historical facts; rather, it reconstructs the past in ways that are continuously adapted to contemporary needs. Through these crystallized "figures of memory," a group cultivates a shared We-consciousness, thereby establishing its identity and continuity over time.

Building on the methodology outlined above, this study develops a multi-level and multi-type system of research materials. The first category consists of academic writings and journal articles, which form the basis of the study’s theoretical construction. These include both Chinese and international classics such as Hofstede’s Culture and Organization, Said’s Culture and Imperialism, and Sun Longji’s The Deep Structure of Chinese Culture, alongside recent empirical findings published in leading journals on national culture, innovation capacity, national psychology, and network society. The second category comprises policies, regulations, and official statistics. Legal texts such as the Constitution, the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Promotion of the Film Industry, and the Cybersecurity Law define the institutional norms governing cultural activity. Meanwhile, annual reports and data issued by agencies such as the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television (SARFT) and the China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC) provide authoritative sources for understanding macro-level patterns in the cultural sector. The third category consists of materials derived from online platforms and cultural practices themselves, which offer the most immediate insight into the dynamics of civic culture. These include examples such as the Guochao (China-chic) consumption phenomenon, online buzzwords, short-form dramas, online literature and its adaptations, and expressions of online nationalist sentiment, together with associated platform data (e.g., the 2025 Douyin Intangible Cultural Heritage Report). Such materials vividly illustrate the creative vitality of civic culture and its dynamic tension with national culturee.

In conclusion, through the combination of qualitative theories and quantitative data, and the corroboration of macroscopic investigation and micro cases, this study has formed a methodological combination that can effectively deal with the complex interaction between the "nation-citizen"culture. The research material on which the study is based combines theoretical depth, policy orientation and vividness of reality, providing solid support for the in-depth argumentation.

3. Connotation and Structure of National culture and Civic Culture

To examine the dialectical relationship between national culture and civic culture, it is first essential to clarify the connotations, constituent elements, and functional positioning of these two core concepts within the broader social system. They do not exist in isolation, but are two distinct and closely related levels in a unified social and cultural ecology.

3.1. Connotation, Function, and Structure of National culture

National culture is not an enduring category that has existed since antiquity; rather, it is a product of the construction of the modern nation-state, marked by purposiveness, strategic intent, and deliberate design.

National culture is an ensemble of cultural forms advocated, shaped, and promoted by dominant political, economic, and cultural elites within a country’s political boundaries, with the maintenance and enhancement of national interests as its core value orientation. It comprises a set of shared norms, values, historical narratives, and collective priorities aimed at providing citizens with a unified “blueprint for lifestyle design” and fostering a national identity that transcends region, ethnicity, and class—an overarching identity situated at the level of the nation-state.

Consequently, national culture carries strong constructive and instrumental attributes. It represents a typical other-value-oriented cultural form, whose evaluative criterion lies not in the “authenticity” of the culture itself but in its “effectiveness” in consolidating national power.

From the perspective of generative logic, national culture is both a necessary requirement and an inevitable outcome of modern nation-state formation. As Charles Tilly revealed in his analysis of state formation in Western Europe, the modernizing state must integrate institutions and culture to establish a rationalized system of power capable of effectively mobilizing, managing, and supervising society. In pre-modern societies, individuals’ loyalties were often tied to local lords, clans, or religious communities. With the emergence of the modern state, however, it became necessary to cultivate a new form of loyalty oriented toward the abstract entity of the “state.” Thus, the primary political function of national culture is to serve this objective. As Edward Said also emphasized, culture constitutes an arena in which political and ideological forces struggle for dominance; it is far from a purely aesthetic or spiritual domain.[

7]

Structurally, national culture can be understood as an interdependent cultural ecosystem composed of five subsystems. First is the sovereign territory system, which serves as the physical and spatial carrier of national culture. It includes not only land, territorial waters, and airspace but also functions as a salient cultural symbol. National borders delineate both physical and psychological boundaries between “us” and “them,” materially embodying national sovereignty. Second is the ecological environment system, which provides the material foundation for the survival and development of national culture. A country’s natural endowments, species resources, and climatic conditions not only determine its economic formation, whether agrarian, pastoral, or maritime—but also profoundly shape its myths, philosophical traditions, and artistic styles. The ecological environment may thus be regarded as the earliest “engraving plate” of cultural genes.Third, the political-economic system constitutes the social infrastructure of national culture and reflects the organic integration of political institutions and economic models. Representative governments and free-market economies tend to foster cultures that emphasize individual rights, free competition, and procedural justice, whereas authoritarian governments and state-directed economies are more likely to cultivate cultural orientations prioritizing collective interests, social order, and state authority. Through mechanisms such as resource allocation, social stratification, and legal norms, the political-economic system establishes the fundamental developmental trajectory of national culture. Fourth, the identity system represents the most central yet most concealed component of national culture—the spiritual core that binds the preceding material and institutional systems together. Its primary function is to redirect and consolidate people’s loyalties away from traditional bases such as family, clan, locality, or religion toward the political community of the modern nation-state. This identity system is woven from multiple sub-identities, including cultural identity derived from shared historical memory and cultural traditions, political identity grounded in recognition of the national political system and citizenship, and ethnic identity concerning relations among diverse groups within the national territory. The state actively cultivates this identity system by constructing a unified national historical narrative, establishing national heroes, promoting a national common language, and shaping shared memories of “national shame” and “national glory”. Fifth, the cultural sector system consists of the public cultural service system and the cultural industry system. Public cultural service refers to non-profit activities that organize cultural production and provide cultural resources to meet citizens’ spiritual and intellectual needs, such as entertainment, leisure, fitness, knowledge, aesthetics, and communication. By contrast, the cultural industry encompasses profit-oriented sectors engaged in cultural production and the provision of cultural services. Together, these two components form a relatively comprehensive system of cultural mobilization and constitute key channels through which national culture and civic culture continuously transform and influence one another.

These five systems are interdependent and mutually constitutive, collectively forming the macro-structure of national culture. Sovereign territory and the ecological environment constitute its natural foundation; the political-economic system and the cultural sector system provide its institutional skeleton and substantive body; and the identity system serves as its animating soul.

3.2. Connotation, Function, and Structure of Civic Culture

In contrast to the grand, macro-level narrative of national culture, civic culture is the “living” culture that circulates through the social atmosphere and is embodied in the everyday words and actions of millions of citizens. It is not designed by any authoritative institution; rather, it is a spontaneously generated web of meanings that has accumulated over long periods of history and is continually reproduced through daily interactions.

Civic culture consists of a set of psychological elements, values, and behavioral patterns shared across a population—a “coagulation of the common psychological elements of citizens.” It functions as a cultural gene deeply embedded within each member of an ethnic community, transmitted across generations and expressed through concrete material forms and behavioral practices. From a semiotic perspective, civic culture is an expansive and intricate symbolic system. Any seemingly ordinary object—a bowl of rice, a cup of tea, a bow, or a festival—within a specific cultural context ceases to be merely a physical entity and becomes a symbol saturated with rich cultural connotations. Through persistent use across historical and social practices, the meanings attached to these symbols are continuously enriched and reinforced, eventually condensing into symbols that carry profound collective memories and shared values, their cultural significance far exceeding their physical attributes. The process of growing up as a citizen is therefore one of continuously learning, interpreting, and internalizing this symbolic system and, ultimately, becoming a cultural “native.” Through the use of shared symbols, individuals communicate smoothly and affirm their collective identity as “us.” This “symbolic field,” composed of countless such symbols, constitutes the basic domain of civic culture.

Within the civic culture system, the perceptible parts ("signifant" or "representamen"), such as food, clothing, and architecture, gradually accumulate cultural meanings through human experience and memory. In this process, perceptible concrete objects and the historical-traditional experiences of the nation (textual meanings) continually overlap and merge, and the form and meaning of civic cultural symbols ("signified" or "objects") are continuously strengthened (symbolized). For example, the sundial was a relatively common timekeeping instrument in ancient China, primarily used to determine the time of day or moment through the position of the sun's shadow. Initially, it held little symbolic meaning or cultural connotation. However, after long historical and cultural sedimentation, the sundial, beyond its practical value, increasingly carries additional symbolic meanings and values, such as representing the inheritance of ancient Chinese scientific and technological culture and the virtue of cherishing time. It has transformed from a purely practical perceptible object into a representative symbol of Chinese civic culture through historical symbolization. Of course, this weakening of the signifier and strengthening of the signified does not mean that the perceptible object in civic cultural symbols is unimportant; on the contrary, it is a crucial carrier of cultural symbolic meaning. Within the framework of the civic culture system, the associations and imaginations evoked by citizens ("the recipients") within the specific holistic system of civic cultural symbols lead to their own understanding and cognition of the perceptible parts, endowing civic cultural symbols with cultural symbolic meaning and shared memory. The German sociologist Angela Kepler discussed this: "Social memory requires certain crystallization points upon which recollections can be anchored, such as certain dates and festivals, names and documents, symbols and monuments, even everyday objects, etc. Such practices of recollection make an important contribution to the realistic self-understanding of many cultures, collectives, and their members in a given period."[

8] From the perspective of Jan Assmann's cultural memory theory, this is also the process where communicative memory continually transforms and overlaps into cultural memory. Civic culture is not only symbols shared by people in the "present" but also "congealed time" from the "past," transmitted through careful selection and ritualized inheritance. Jan Assmann emphasizes: "Thoughts can only become objects of memory and enter memory by becoming concretely perceptible; in this process, concepts and images merge."[

9] From this viewpoint, the core of civic culture is precisely a nation's cultural memory, which endows the entire socio-cultural sign field with temporal depth and normative power.

Structurally, civic culture can be understood as a concentric system composed of four interrelated layers arranged from the inside outward. First, the artifact layer: This is the most visible and material manifestation of civic culture, the “hardware” of culture. It includes items of daily life such as food, clothing, architecture, and modes of transportation. As the outermost layer, it is the most susceptible to change under the influence of foreign cultures, as seen in the widespread adoption of Western food and clothing in China. Yet even as appearances change, underlying production techniques, usage habits, and aesthetic preferences often retain deep cultural genes. Second, the institution layer: Positioned between formal state laws and informal customs, this layer constitutes the “software” that regulates social behavior, translating abstract values into operable social norms. It serves as a critical link between the artifact layer and the deeper behavior and mentality layers. It includes forms of social organization, family structures, marriage systems, interpersonal norms, and the cultural ethos underlying business contracts. The institution layer defines the roles, rights, and obligations of social members across different contexts, providing the cultural script for the orderly functioning of society. Third, the behavior layer: This consists of relatively stable behavioral patterns and customs shaped through long-term socialization. It includes verbal and nonverbal communication styles (e.g., honorific use, interpersonal distance), conceptions of time (linear vs. cyclical), consumption patterns, leisure practices, and life-cycle rituals such as weddings, funerals, and festival celebrations. Although more flexible and spontaneous than the institution layer, behavioral patterns still follow culturally established norms. For instance, citizens of different countries display notable differences in expressing gratitude, managing conflict, and interacting with elders. Fourth, the mentality layer: This is the core and soul of civic culture—the deep motivational structure underlying the three external layers. It consists of relatively stable systems of values, cognitive styles, aesthetic sensibilities, religious beliefs, and national character formed through long-term historical and cultural accumulation. Although the most concealed and slowest to change, it ultimately determines the essential features of a culture, forms the root of distinctions among civic cultures, and shapes the fundamental ways citizens perceive the world, evaluate situations, and make decisions.

These four layers form an organic whole. The mentality layer radiates outward, deeply influencing the institutional, behavioral, and material dimensions of civic life. Conversely, changes in the outer three layers, through contact with external cultures or modernization—gradually permeate inward and reshape the core mentality layer over time.

In summary, national culture is a macro-strategic cultural construction centered on state power and national interests, characterized by a five-component ecological structure. Civic culture, by contrast, is a micro-practice system centered on shared meanings and symbols, composed of a psychologically oriented four-layer concentric structure. Although they differ fundamentally in origin, logic, and function, they do not exist in isolation. Rather, they penetrate and shape each other continuously within a shared social space.

4. The Infiltration of National Culture into Civic Culture and the Reaction of Civic Culture to National Culture

The nation-state is not only a political entity defined by territory and population but also a stable human community unified by a shared language and culture. The homogeneity of civic culture reflects the convergence of these two dimensions.[

10] Within the nation-state system, civic culture—through prolonged historical evolution—gradually becomes consolidated, accumulates substantial cultural resources, and ultimately attains the position of mainstream culture. Once the state succeeds in unifying the political nation under the banner of civic culture, it inevitably begins to exert gradual and profound influence on both ethnic cultures and civic culture itself in accordance with national interests.

The relationship between national culture and civic culture is a continuous, two-way dynamic interaction. State power attempts to shape civic culture from the top down in order to achieve political and social objectives. Meanwhile, the resilient civic culture, through processes of acceptance, filtration, and adaptation, exerts bottom-up reactive influence on national cultural agendas.

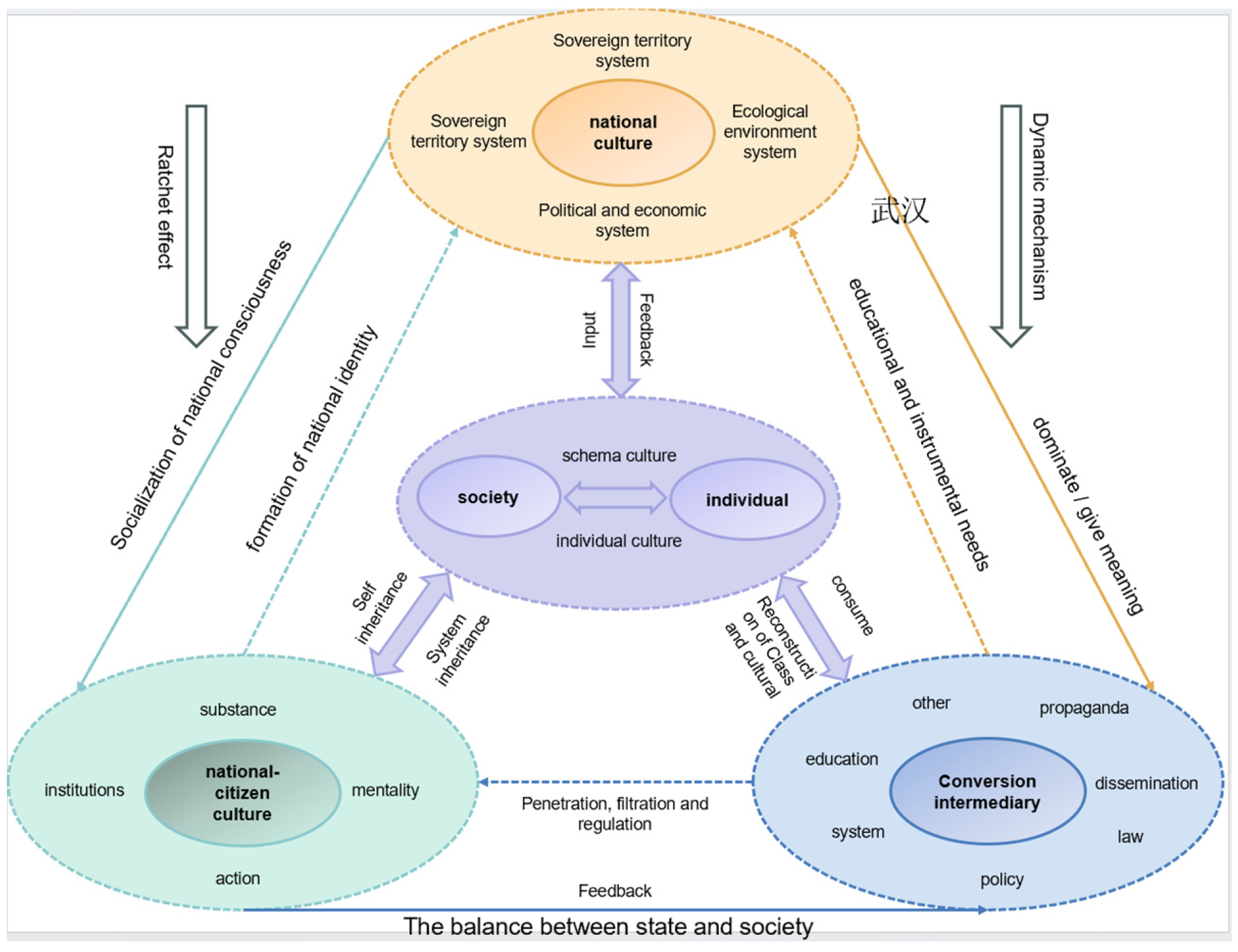

Figure 1.

Mechanism Diagram of the Interaction Between National Culture and Civic Culture.

Figure 1.

Mechanism Diagram of the Interaction Between National Culture and Civic Culture.

4.1. Mechanisms of National Culture’s Penetration into Civic Culture

Drawing strictly on Gramsci's framework, this section analyzes how state apparatuses seek to transform "political force" into "cultural consent".For national culture to transition from blueprint to reality, it must find effective pathways to internalize its values, behavioral norms, and grand narratives into the conscious awareness and daily practices of the people. This process does not always rely on coercive force but is more frequently achieved through a more subtle form of cultural hegemony aimed at "winning consent." Gramsci pointed out that stable rule depends not only on the coercion of the state apparatus (e.g., the military, police, courts, etc., within "political society") but, more crucially, on establishing hegemony within "civil society" (e.g., schools, churches, media, trade unions, and other non-governmental organizations), thereby gaining the consent of the people. Cultural hegemony refers to the process by which the worldview, values, and moral standards of the ruling class are successfully shaped into the "common sense" of the entire society, leading other social strata to voluntarily accept the existing order ideologically and culturally. This process is "capillary" in nature, subtle, pervasive, and omnipresent. The permeation of national culture into Civic Culture vividly illustrates this logic. Its main pathways include:

4.1.1. Propaganda, Dissemination, and Ideological Socialization Discipline and Guidance through Laws, Institutions, and Policies

This is the most direct and fundamental means of establishing cultural hegemony. By controlling or exerting substantial influence over key channels of ideological production and dissemination, the state systematically instills its core values and official historical narratives into citizens—especially younger generations.

Within the realm of propaganda and dissemination, the most important mechanism is the national education system. Promoting the official language, standardizing curricula, and regulating history textbooks constitute the most fundamental and enduring means by which a modern state shapes a homogeneous civic culture. Althusser identified the education system as the most significant “ideological state apparatus.” Through standardized curricula, teacher training, and examination systems, the state embeds narratives of national origin, state history, heroic figures, civic duties, and political legitimacy into the minds of successive generations. In this way, cultural hegemony is consolidated in a seemingly natural and non-coercive manner through intergenerational transmission.

Mass media networks also play a crucial role in enabling the state to permeate civic culture through agenda-setting and framing. By establishing official media outlets or influencing commercial media through regulatory, financial, and personnel mechanisms, the state guides public attention by determining which issues are highlighted, marginalized, or ignored, and by providing officially sanctioned interpretive frameworks. Through repeated internal propaganda about development achievements and moral exemplars, as well as through the external construction of specific international images (both friendly and adversarial), mass media provide powerful emotional and cognitive support for national narratives.

Furthermore, national symbols and rituals serve as daily performances of national culture. By promoting visual and auditory symbols such as the national flag, anthem, and emblem, and embedding them into everyday settings, the state continually activates national consciousness. Large-scale national celebrations, military parades, and commemorative events generate intense emotional resonance and collective identity through highly ritualized performances at specific temporal and spatial nodes, transforming the abstract notion of the nation into a perceptible and emotionally compelling experience.

4.1.2. Discipline and Guidance Through Laws, Institutions, and Policies

If propaganda and dissemination represent “soft” influence, then laws and policies constitute the “hard” disciplinary mechanisms of cultural governance. Through a set of institutional arrangements, the state establishes clear boundaries within the cultural domain, implements reward and punishment mechanisms, and guides cultural production and consumption toward directions aligned with its strategic objectives.

First is the boundary-setting function of relevant laws and regulations in the cultural domain. The state enacts provisions on cultural rights and obligations in the Constitution, along with a series of specific laws such as the Publication Law, Regulations on Radio and Television Administration, Film Industry Promotion Law, and Cybersecurity Law, to comprehensively regulate the production, dissemination, consumption, import, and export of cultural content. These laws clearly define what constitutes lawful and encouraged cultural activities versus what is restricted or prohibited, establishing insurmountable "red lines" and "bottom lines" for the entire cultural market.

Beyond formal legal norms, the state also assumes a “gatekeeper” role through censorship and licensing systems. These systems include film approval mechanisms, book-publishing licenses, game-license management, and internet-content review procedures. They scrutinize cultural products before they enter the market, filtering out content considered politically sensitive, sexually explicit, excessively violent, historically nihilistic, or inconsistent with mainstream social values. Through these “valves,” the state ensures that cultural products entering public circulation broadly conform to the cultural direction it seeks to promote.

Finally, through the establishment of special cultural-industry funds, financial subsidies, tax incentives, and preferential credit policies, the state can selectively support cultural enterprises and projects aligned with its ideological orientation and industrial development strategies. Such targeted industrial policies effectively reshape the supply structure of the cultural market, increasing the accessibility and visibility of the cultural products the state intends citizens to consume.

4.1.3. Popularization and Acculturation Through the Public Cultural Service System

In addition to direct propaganda and regulatory measures, the state also builds an extensive public cultural service system to provide mainstream value–aligned cultural products and services to citizens on a continuous, free, or low-cost basis, thereby achieving a “silent influence” of gradual acculturation.

For instance, libraries, museums, art galleries, cultural centers, science and technology museums, and comprehensive cultural service centers found in both urban and rural areas, form a "capillary network" through which national culture extends to the grassroots. Through their collections, exhibitions, lectures, training sessions, and other activities, these institutions systematically disseminate scientific and cultural knowledge, historical traditions, and mainstream arts to the public. This not only enhances the cultural literacy of citizens but also subtly shapes their cultural tastes and value identifications.

Furthermore, national theaters, symphony orchestras, ballet companies, film studios, and similar institutions are tasked with producing “classical works” that embody the highest artistic standards and value aspirations of the nation. Through national tours, television broadcasts, and art festivals, these works establish benchmarks for cultural and artistic creation across society, exerting a profound influence on the aesthetic standards of the public.

In conclusion, through propaganda and education, legal regulation, and public cultural services, national culture constructs a multidimensional network of influence that seeks to incorporate citizens’ cognition, emotions, tastes, and behaviors into the framework of its cultural hegemony.

4.2. The Dynamic Influence of Civic Culture on National Culture

Here, we apply Assmann’s distinction between “communicative memory” and “cultural memory” to explain how citizens selectively filter and reinterpret national narratives. Although national culture influences citizens through propaganda, legislation, and institutional mechanisms, citizens are not passive “cultural sponges” that simply absorb ideological directives. Rather, they are active, creative, and critical agents of cultural practice. Rooted in the complexities of everyday life, civic culture—endowed with strong resilience and vitality—exerts a profound and diversified counterforce on the top-down construction of national culture. This bottom-up influence constitutes an indispensable dimension in the dialectical interaction between national culture and civic culture. Understanding this process requires engaging with theories of cultural consumption and cultural-psychological structures.

From the 1970s onward, theorists such as Pierre Bourdieu and Jean Baudrillard challenged the traditional assumption that consumers are passive recipients of cultural manipulation. Bourdieu’s concepts of Habitus and Taste emphasize that cultural consumption choices are shaped by durable dispositions internalized through one’s social class and educational background. Consumption thus becomes an act of distinction, demarcating social boundaries and articulating identity. Baudrillard further argued that in postmodern societies, individuals increasingly consume the “symbolic value” of goods rather than their material utility. Stuart Hall’s influential encoding/decoding theory adds another layer of complexity. While cultural producers “encode” messages aligned with dominant ideology, audiences do not necessarily accept these messages uncritically. Instead, they may adopt one of three decoding positions: a dominant-hegemonic reading (fully accepting the encoded meaning), a negotiated reading (partially accepting the dominant meaning while modifying it according to personal experiences), or an oppositional reading (rejecting and subverting the encoded meaning). This interpretive agency introduces significant uncertainty into the dissemination of national culture. Together, these theories demonstrate that cultural consumption and reception are active processes of meaning-making, wherein individuals select, adapt, and recreate meanings through daily practices, continuously testing and reshaping national culture.

4.2.1. Selection, Resistance and Forcing by Marketized Consumption

In today’s context, where the market economy plays a major role in allocating cultural resources, consumers’ “voting with their feet” and “voting with their money” have become the most direct and powerful mechanisms through which civic culture reacts upon national culture. Market data such as box office earnings, television ratings, book sales, and online click-through rates constitute the most direct test of cultural products. A work that is ideologically and artistically excellent but detached from the public and rejected by the market will ultimately have limited influence. In contrast, a commercial work that strikes a chord and resonates widely with the public may gain enormous social traction, even without official backing, eventually forcing official media and critics to pay attention and offer positive interpretations. Such market signals directly affect the flow of cultural capital, forcing producers, including state-owned cultural enterprises, to carefully study and cater to the aesthetic tastes and entertainment needs of the nation while conveying mainstream values.

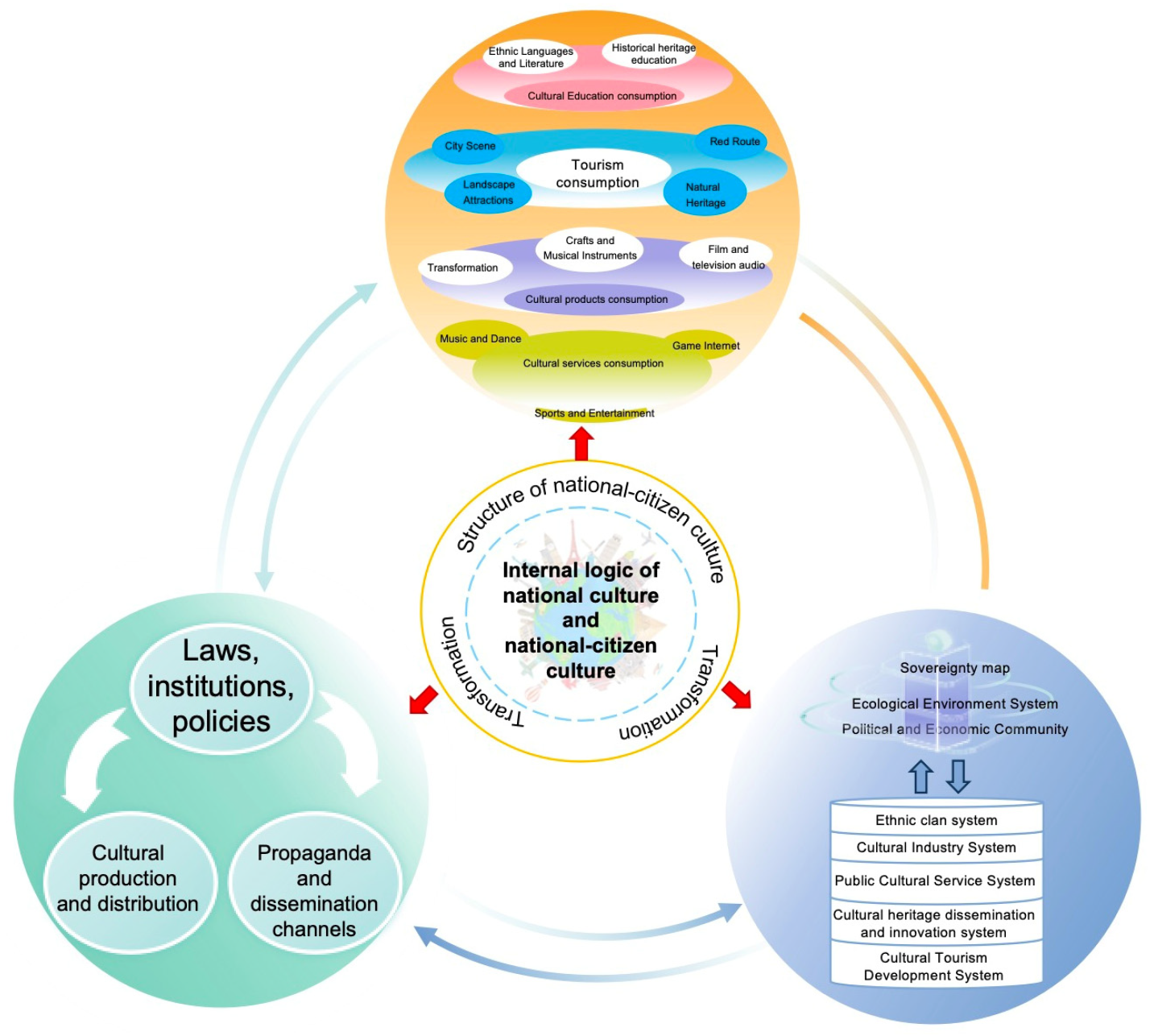

Figure 2.

Internal Logic of National Culture and Civic Culture.

Figure 2.

Internal Logic of National Culture and Civic Culture.

In the current digital and mobile internet era, the logic behind the emergence of cultural hotspots has fundamentally changed. An online drama, a viral song, or an internet buzzword can rapidly gain traction through social media and become a cultural phenomenon in a very short time. These bottom-up, grassroots trends often disrupt the agenda-setting of official media, forcing state cultural institutions to respond, interpret, or even co-opt them. For example, the sudden fame of Ding Zhen, an ordinary individual from a remote area, turned him into an unofficial ambassador for national tourism and poverty alleviation campaigns—an unexpected fusion of folk aesthetic appeal and state narrative.

When people are dissatisfied with certain state policies or cultural products, they may also engage in “soft” resistance through consumer behavior. For instance, audiences respond to overly didactic or plot-implausible film and TV works by giving low ratings on review sites and “roasting” (criticizing) them on social media, creating negative word-of-mouth that affects market performance. This kind of collective criticism, mediated by consumption, constitutes a kind of effective supervision and pressure on nationalized production.

4.2.2 Filtering, Adaptation, and Reshaping by the Cultural-Psychological Structure

Beyond the direct feedback generated through cultural consumption, the interaction between national culture and civic culture is even more profound at the psychological level. A nation’s “cultural-psychological structure,” formed through millennia of historical experience and embedded in the collective subconscious, functions as an invisible yet powerful “filter” that processes top-down cultural inputs in highly complex ways.

When national culture is introduced as external information, people first attempt to “assimilate” it using existing cultural-psychological structures (“schema”). If the information is highly consistent with existing schemata (e.g., the state propaganda emphasizing collectivism in a society with a Confucian cultural background), it is easily accepted. If the information seriously conflicts with established schemata, it may be rejected, or people may adapt its interpretation to “accommodate” it within their cognitive framework.

Although the state endeavors to construct a unified, official collective memory, this narrative coexists with a vibrant and diverse array of family memories, local memories, and folk narratives transmitted across generations. These unofficial memories often carry greater emotional resonance and lived texture, enabling them to supplement, modify, or even challenge official grand narratives. When state narratives clash with individuals’ personal experiences or inherited folk memories, their persuasive power is significantly weakened.

Even when people accept grand concepts promoted by the state, they often “recode” them using their own life wisdom and local knowledge. The broad notion of the ‘Chinese Dream’ is often translated by ordinary people into everyday aspirations such as purchasing a home or ensuring their children’s education. Solemn political discourse may be deconstructed and disseminated in entertaining ways by netizens through “memes” and “emoticon packs.” This “creative misinterpretation,” on the one hand, makes national culture more relatable and communicable; on the other hand, it may also dilute or transform its original serious meaning.

In addition, societies at particular historical moments may develop a pervasive collective mood, such as anxiety, optimism, nostalgia, or confusion. This collective sentiment can temporarily become the most dynamic element of the cultural-psychological structure, profoundly shaping how the public interprets national cultural messages. When social anxiety prevails, “healing-style” cultural products tend to gain significant popularity, while propaganda emphasizing “struggle” may elicit only lukewarm responses. The ebb and flow of collective sentiment constitute the “pulse of the people,” which cultural policymakers must attentively perceive and respond to; even the most sophisticated cultural products will fail to resonate if this sentiment is ignored.

4.2.3. Negotiation, distinction and Identity Construction of Subcultures

In the context of globalization and digitalization, civic culture has become increasingly fragmented, giving rise to numerous subcultural communities organized around shared interests, identities, and values. Each subculture possesses its own symbolic system, jargon, and behavioral norms, and maintains a complex, negotiated relationship with the state-promoted mainstream culture that aims for ideological and cultural uniformity.

Members of subcultures employ distinctive clothing styles, music genres, linguistic expressions, and online vernacular to construct group boundaries and articulate their difference from other communities. Through this symbolic differentiation, they achieve a heightened sense of identity and belonging. For many young people, identification with a subcultural community may, in certain contexts, outweigh their broader identity as citizens.

This pluralization of identities challenges the state’s efforts to construct a singular, homogeneous national identity. Some subcultures, particularly interest-based online communities—can also become sites for expressing dissent or enacting symbolic resistance. Through parody, spoofing, and satire, subcultures may deconstruct and contest the authority of mainstream discourse. Dick Hebdige’s classic study of punk culture demonstrates that subcultural groups often create distinctive “styles” through bricolage, that is, by appropriating ordinary objects from mainstream society and endowing them with new, subversive meanings. In doing so, they symbolically articulate resistance to or alienation from the dominant social order.

Of course, subcultures do not always stand in direct opposition to mainstream culture; more commonly, the relationship involves negotiation and strategic interaction. For example, certain non-mainstream subcultures such as rap, once brought to public attention through variety shows, have been required to modify their content—removing references to violence or drugs and integrating more “positive energy.” At the same time, the musical aesthetics and fashion associated with hip-hop have significantly shaped the broader landscape of mainstream pop culture. This dynamic reflects a process of mutual incorporation and transformation.

With the development of society, “identity politics” based on dimensions such as gender, ethnicity, and sexual orientation has become increasingly prominent. Through social movements and cultural expressions, these groups have demanded that the State recognize their unique cultural identities and correct any differences and prejudices that may exist in the national culture. For example, the feminist movement has challenged the patriarchal notions entrenched in the national culture, while the cultural revival of ethnic minorities has demanded a place in the national narrative. These demands compel national culture to continually adapt, moving from a singular, homogeneous model toward greater diversity and inclusivity.

In sum, civic culture—through consumer choice, deep psychological dynamics, and subcultural negotiation—generates a powerful bottom-up counterforce to national culture. This sustained tension transforms cultural construction into a dynamic process of ongoing dialogue and negotiation rather than a one-directional project of indoctrination. It is through this dialectical process of mutual penetration and reciprocal shaping that national culture and civic culture co-evolve and advance together.

5. Challenges and Integration in the Age of Digitization: Practice and Reflection in Contemporary China

The theoretical framework established in the previous sections—characterizing the interaction as a dialectical tension between hegemonic construction and grassroots memory—finds a compelling testing ground in contemporary China. This section applies the proposed model to analyze how digitization has disrupted and reconfigured the mechanisms shown in

Figure 1, specifically examining the shift from one-way transmission to multi-directional negotiation. National culture and civic culture are not static formations. Rather, they constitute a dialectical whole that continually shapes a nation’s spiritual outlook through tension, interaction, and integration. Entering the twenty-first century, this dialectical relationship has encountered a transformative new variable: digitization. Digital technologies, represented by the Internet, big data, and artificial intelligence, which are not simply new tools; they constitute a “new field” that restructures social relations, redistributes symbolic power, and reshapes the cultural ecosystem. With unprecedented speed and magnitude, digitization has altered the context of dialogue, the channels of transmission, the modes of cultural production, and the ultimate equilibrium between national culture and civic culture.

5.1. Reconstruction and Challenges of China's National Culture in the Digitalized Field

In the traditional era of one-way communication, national culture was primarily inculcated and shaped from the top down through centralized and authoritative channels such as textbooks, official media, and state-owned cultural and artistic troupes. However, the advent of digitization has completely disrupted this communication pattern, and the influence of traditional media is undergoing a structural decline. From 2017 to 2021, the number of cable TV subscribers in China continued to decline, with the average annual decrease in revenue reaching as high as 9.65%[

11]. Meanwhile, the newspapers readership dropped from 55.1% in 2014 to 22.5% in 2024[

12]. At the same time, both the number of Internet users and the Internet usage rate have been continuously rising. According to data from the China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC), as of June 2025, the number of Internet users in China had reached 1.123 billion[

13]. The deep penetration of mobile Internet means that nearly every citizen has become a potential information publisher and cultural producer. Behind these data lies a profound shift in information-dissemination power. The Internet, especially mobile Internet, has dismantled the monopoly of information and empowered people with the unprecedented agency to select information and create discourse, thus posing a serious challenge to the traditional way of constructing national culture. The efficacy of the "broadcast-style" one-way inculcation channels that national culture previously relied on has sharply diminished. The main battlefield for the contest over cultural hegemony has irreversibly shifted to the digital cyberspace characterized by social media, short-video platforms, and algorithmic recommendations. On this new battlefield, every netizen has become a potential "decoder" and "re-encoder," and the flow of information has assumed a complex "many-to-many" pattern. This presents an unprecedented challenge to agenda-setting in the construction of national culture. In response to this structural transformation, China has undertaken a series of profound strategic adaptations at the level of national cultural construction, attempting to reshape its cultural hegemony within this new digital "field."

With the rapid development of big data and AI, the interaction between China's national culture and its civic culture has taken on a series of new characteristics and practical forms. The UGC (User-Generated Content) and PGC (Professional Generated Content) models that preceded AIGC (AI-Generated Content) significantly lowered the barrier to cultural creation. In 2024, the number of newly established enterprises in China’s digital creative industry reached 192,300; the revenue of the online literature market amounted to 38.9 billion yuan, and the market size of its IP adaptations exceeded 250 billion yuan[

14]. The micro-drama market grew at a high rate of 267% in 2023[

15] . The rise of forms such as short videos, live streaming, online literature, and podcasts has enabled ordinary people to participate in the production of cultural content, giving rise to a massive amount of cultural creativity originating from the public. This has led to an unprecedented enrichment and diversification of the content supply of civic culture, releasing its vitality and creativity to a great extent. At the same time, the "ubiquitous media" trend of platform technologies are systematically undermining the legitimacy of traditional public cultural institutions. For example, the Douyin platform has demonstrated astonishing capacity in disseminating intangible cultural heritage—

the 2025 Douyin Intangible Cultural Heritage Report shows that over the past year, Douyin added more than 200 million videos related to national-level intangible cultural heritage, with cumulative views reaching 749.9 billion. On average, 65,000 live broadcasts related to intangible cultural heritage were held daily[

16]. This has, in fact, surpassed the communication effectiveness of the vast majority of official cultural institutions. This "bottom-up" cultural productivity constitutes the most dynamic component of civic culture in the digital era. It enriches the cultural ecosystem while simultaneously presenting national culture with a massive amount of new content that requires guidance or discipline. At the same time, algorithmic recommendation technology, while providing users with personalized content, also intensifies the formation of "information cocoons" and cultural circles. People are increasingly inclined to consume content that interests them and aligns with their own values, forming relatively closed cultural "circle-layer" or "digital tribes." These circle-layers possess a highly unified "jargon," value system, and behavioral norms internally, exhibiting extremely strong cohesion. As a result, the unified cultural narrative that the state attempts to construct for all citizens faces the risk of being filtered, refracted, or even blocked by various circle-layers during dissemination.

Facing the challenges brought by digitization, China has not stuck to traditional models in its national cultural construction but has actively pursued strategic adaptation and digital transformation, seeking to reshape and consolidate its cultural hegemony in the new media environment.

First, discursive innovation has occurred at the level of top-level design. The introduction of the core concept of "cultural confidence" is, to a certain extent, a sophisticated strategic response to the numerous challenges faced by national cultural development in the new era. It no longer merely emphasizes adherence to a specific ideology but grounds its discourse in the more inclusive and historically profound excellent traditional Chinese culture, revolutionary culture, and advanced socialist culture, aiming to evoke a deeper sense of cultural pride and identity among the people.

Second, the core of national culture lies in its discourse system. In recent years, the state has vigorously promoted the deep integration and development of traditional and emerging media, establishing a number of new mainstream media platforms such as "Yangshipin" (CCTV Video) and "Xuexi Qiangguo" (Study the Great Nation). In the mobile internet era, traditional top-down and didactic propaganda methods have proven ineffective. Government agencies, official media, and even the military and judicial departments have opened social media accounts, directly entering the public opinion arena, participating in hot topic discussions, releasing authoritative information, conducting live web broadcasts, proactively setting agendas, and interacting with netizens. National mainstream media and official institutions have sought to make their discourse more “youth-oriented” and “personalized.” They are actively establishing a presence on platforms such as Bilibili and Douyin (TikTok China), using internet buzzwords and memes to "dialogue" with the younger generation of netizens, and employing online language and vivid cases to interpret national policies, striving to resonate with young internet users. This shift in strategy is a positive response and "adaptation" to the new forms of civic culture, aiming to embed the national narrative into the daily cultural consumption of young people in a more acceptable manner. It also signifies a transformation in the state's approach from traditional "management" thinking to actively "guiding" and "competing" in the digital sphere.

In terms of external communication and internal consensus building, China has also increasingly emphasized the use of digital methods/tools. On the one hand, it has supported a series of high-tech science fiction films such as the "Wandering Earth" series, as well as a series of well-produced historical dramas and animated films, packaging and disseminating Chinese values in industrialized film and television language and in a narrative style that suits contemporary aesthetics and has gained a greater influence in Southeast Asia and other overseas regions. On the other hand, China has actively utilized overseas social media (e.g., Twitter, Facebook, YouTube) to tell the Chinese story to the world in the form of short videos, documentaries, live broadcasts, etc., through CGTN and other external communication media, as well as through the work of popular netizens (e.g., ishowspeed, the globally renowned influencer, came to China and visited the mainland China with the netizen director who is influential among young people in the Taiwan region, etc.). In the area of public cultural service system, China's public cultural service system has been strengthened by a number of initiatives, in an attempt to break the discourse monopoly of mainstream Western media.

In terms of the public cultural service system, the Chinese government is also promoting digital transformation. National digital libraries, public culture cloud platforms, and online exhibitions in museums have made it possible for high-quality cultural resources to break through time and space constraints and reach a wider audience. This is not only a manifestation of cultural benefit to the people, but also a way to popularize mainstream culture and cultivate national literacy in the digital space.

To a certain extent, these measures and strategic adjustments have achieved positive results; however, they still face profound challenges inherent in the digital realm itself. The trend towards "media ubiquity" of platform technologies is systematically undermining the legitimacy of traditional public cultural institutions. For example, the Douyin platform has demonstrated an astonishing energy in the dissemination of intangible cultural heritage - according to the "2025 Douyin Intangible Cultural Heritage Data Report", in the past year Douyin has added more than 200 million new national intangible cultural heritage-related videos, with a cumulative total of 749.9 billion plays - which in fact exceeds the dissemination effectiveness of most official cultural institutions.

5.2. New Forms of Civic Culture and Their Profound Impacts

In the new era, technological iteration has provided an unprecedentedly broad stage for the expression and creation of civic culture. The vitality of China’s civic culture has been stimulated like never before, giving rise to a series of new phenomena that profoundly influence social mentality and cultural trends. Yet, this vitality is also accompanied by new contradictions and tensions, making the manifestation of civic culture in digital space extremely complex.

From the perspective of market consumption, the rise of guochao (China-chic) in recent years represents a paradigmatic case of civic culture exerting influence on national culture. Originating from younger consumers' renewed identification with domestic brands such as Li Ning and Anta, and their enthusiasm for products infused with traditional aesthetics—such as cultural-creative merchandise from the Palace Museum and Chinese-style cosmetics—guochao reflects a market-driven expression of cultural confidence emerging from the grassroots. This consumer-driven trend has not only reshaped the domestic market landscape but, more importantly, has provided vivid and compelling public support for the official grand narrative of “cultural confidence.” In this domain, national cultural agendas and popular consumption preferences have achieved a notable resonance.

Beyond relatively positive phenomena such as guochao, the integration of cultural consumption and digitalization has also generated new and complex challenges—most notably, the rise of the fan-circle (fandom culture). Centered on idol worship, these communities exhibit remarkable organizational and mobilizational capacities in the digital age. They are capable of executing highly efficient collective actions such as coordinated data-boosting, comment manipulation, public opinion steering, and organized philanthropic campaigns. This organizational strength can be mobilized for positive purposes, amplifying patriotic sentiment; yet it can also produce serious social controversy, challenging legal and ethical boundaries through irrational idol worship, cyber aggression, and encroachment upon public interests. Moreover, fandom dynamics have expanded beyond entertainment into sports, digital products, automobiles, and even cities and historical narratives. The subsequent state intervention—exemplified most prominently by the Qinglang (“Clean and Bright”) campaign—cannot be understood merely as a regulatory effort to correct market disorder. Rather, it reflects the cyclical interaction between subcultural autonomy and the reassertion of state hegemony. Fan-circles, with their ability to rapidly mobilize and shape online discourse, constituted an emerging civic force largely outside state control. In this sense, Qinglang can be interpreted as a strategic disciplinary intervention aimed at re-establishing state authority over youth values and the digital public sphere. The challenges posed by such digitally native communities will continue to test the adaptability and resilience of national cultural governance in the digital age.

The widespread diffusion of mobile Internet and social media has also accelerated the circulation and amplification of collective emotions. Sentiments surrounding particular issues can now spread rapidly, becoming part of the temporary national collective memory. For instance, the popularity of online buzzwords such as “involution” and “lying flat” has captured—and amplified—the fatigue, anxiety, and sense of powerlessness felt by many young people facing intense social competition. Circulating widely through humorous and self-deprecating memes, these expressions constitute a form of soft resistance and a counter-discourse to the mainstream values of “struggle” and “hard work” promoted by the state. Their widespread dissemination has sparked broad public debate on youth development, social mobility, and distributional fairness, effectively compelling mainstream media and policymakers to acknowledge and respond to the deeper structural issues underlying these sentiments. This vividly demonstrates how the cultural-psychological structure of civic culture filters, negotiates, and reshapes national grand narratives within digital space.

Digitization has also fueled the rise of vocal online nationalist sentiments. Although such digital nationalism is a global phenomenon, it is particularly prominent in China. Large numbers of young netizens have shown strong willingness to participate in online defense of national sovereignty and ethnic dignity, often spontaneously “marching” into domestic and international cyberspace to safeguard China’s image. This bottom-up nationalism partially aligns with the objectives of national cultural construction and can even exceed official rhetoric in its assertiveness. However, it also tends toward emotional overreaction, irrationality, and instances of cyber violence, sometimes surpassing the bounds of official control. This suggests that even when civic culture aligns with national culture on certain issues, it may produce unexpected “resonance amplification” effects that introduce new governance dilemmas.

5.3. Towards a New Dynamic Balance: Negotiation, Guidance, and Integration

Contemporary Chinese practice demonstrates that in the digital age, the relationship between national culture and civic culture has already transcended the simplistic dichotomies of “control vs. being controlled” or “conflict vs. confrontation.” Instead, the two now constitute a more dynamic, interactive, and continuously negotiated cultural relationship. Effective national cultural construction must thus shift from the past model of one-way, top-down “propaganda and inculcation” toward a model grounded in two-way “dialogue and guidance.” This requires the state not only to uphold the direction of mainstream values but also to listen to, understand, and absorb the creative vitality and genuine social sentiments emerging from the populace. Only by integrating grand national narratives with content that resonates at the level of individual lived experience—and with market-recognized, socially meaningful cultural products—can cultural hegemony be effectively consolidated in the new era.

A vibrant civic culture, while fostering individuality and creative expression, must also find constructive points of connection with the broader goals of national development and societal well-being. Benefiting from the conveniences of digitalization, civic actors must cultivate rational civic consciousness, critical thinking, and a sense of social responsibility, in order to avoid drifting into the isolation of information cocoons or the emotionalism and venting characteristic of digital populism.

The core of the integration path lies in "structural embedding" rather than "directive overlay." The state has already made relevant attempts in this regard. Regarding influential subcultures emerging in cyberspace, the state and capital often adopt a strategy of "co-option". For example, online novels and pop-up culture, once considered niche, are now widely accepted and utilized by the mainstream film and television industry and official media. By incorporating them into the commercialized cultural industry chain, the state, on the one hand, neutralizes their potential subversiveness and, on the other hand, leverages their vitality to enrich the expression of national culture, achieving the goal of integrating them into the broader framework of national cultural expression. For instance, rather than investing heavily in producing high-brow but inaccessible mainstream melody films, it is better to encourage works like The Longest Day in Chang'an and the short micro-drama Escape from the British Museum through policy guidance and financial support. These works not only conform to market rules but also naturally embody historical and cultural depth and feelings of family and country/national sentiment. This signifies that the function of national culture is evolving from direct production to strategic facilitation of high-quality content. Furthermore, through cooperation with platform companies and policy guidance, the state utilizes powerful algorithmic recommendation technologies to precisely push "positive energy" content (e.g., patriotic videos, scientific and technological achievements, traditional culture popularization) that aligns with mainstream values to massive numbers of users. This constitutes a more covert and efficient form of agenda-setting, subtly shaping the underlying tone of public opinion in cyberspace.

Simultaneously, the path of integration requires the establishment of a "two-way feedback" regulating mechanism rather than "one-way indoctrination". Mobile internet and digital technology have, on the one hand, broken the traditional channels of "one-way infusion" and, on the other hand, made it possible to establish a "two-way feedback" mechanism. Through big data, the state understands the demands, sentiments, and aesthetic evolution of civic culture and uses this as an important basis for cultural policy making.

At the same time, it is changing traditional subsidy methods and establishing a positive interaction incentive mechanism for cultural consumption between the state and individuals. For example, promoting models like "cultural consumption vouchers," where part of the financial subsidies is given directly to citizens, allowing them to choose cultural products autonomously. This model not only respects the market choice rights of civic culture but also provides the most direct market feedback to cultural suppliers (including state-owned troupes) through consumption flows, compelling them to reform and innovate, thereby bridging the boundary between cultural endeavors and cultural industries and realizing a virtuous cycle between state guidance and citizen choice.

Ultimately, the realization of this integrative path relies on forms of adaptive governance that are both intelligent and flexible. The vitality of the digital cultural industry stems from its creativity, fluidity, and grassroots nature; governance should therefore shift from restrictive control toward facilitative regulation that increases social and policy tolerance for new cultural forms. In the context of global cultural competition, China must also establish a more sophisticated global communication strategy. Although China ranks first globally in exports of creative commodities, its exports of high value-added creative services rank only fifth, indicating significant space for growth. The global popularity of Labubu in 2025 illustrates the potential of private-sector cultural creativity in driving China’s global cultural presence. Cultural products capable of forming emotional connections with global consumers in “transcultural contexts” can not only create export value but also enhance China’s discursive power internationally. It is a deeper dialectical integration: the ambitious goal of national cultural self-confidence is transformed into the empowerment and support of national cultural creativity, so that Chinese culture can truly integrate into the world in a more natural and diversified way.

It is foreseeable that under new technological conditions, national culture and civic culture will move towards a new dynamic balance. In this balance, the state will increasingly serve as a "platform builder", "guide of quality content" and "rule maintainer", while the citizens will participate as active "co-builders of culture." Although this process is fraught with challenges, its ultimate goal is to help build a truly modern Chinese civilization—one anchored in strong core values while energized by cultural diversity, creative vitality, and innovative dynamism.

6. Conclusion

This study offers concrete insights for policymakers. First, the construction of national culture in the digital era cannot rely solely on traditional top-down indoctrination. Policymakers must adopt a 'responsive governance' approach, integrating valid elements of civic subcultures into the national narrative to maintain cultural legitimacy. Second, for the cultural industry, the fusion of 'Guochao' demonstrates that commercial success lies in bridging the gap between national macro-narratives and the micro-experiences of citizens.National culture and civic culture are two indispensable dimensions that constitute a nation’s cultural life, existing in a dialectical relationship of unity and opposition as well as mutual interdependence. National culture provides the entire society with a framework of orientation, shared values, and identity; whereas civic culture provides national culture with a continuous foundation of legitimacy, a source of innovative vitality, and a grounding in reality. Neglecting either dimension can result in an imbalance in the cultural ecology: a national culture that consists only of grand narratives but is detached from people's lives will be hollow and fragile; a civic culture that has only spontaneous diversity but lacks the guidance of core values will easily become fragmented and cause disorientation.The interaction of the two is therefore a continuous and dynamic process of construction. Their virtuous cycle is an important indicator of the modernization of national governance capacity.

The effective embedding of national culture into civic culture depends on the synergistic functioning of multiple institutional mechanisms—education, media, law, and ritualized social practices. The success of this embedding lies in whether the grand national narrative can be translated into everyday experiences and emotional connections that citizens can perceive, comprehend, and internalize. At the same time, the healthy feedback of civic culture into national culture requires open channels of public expression, a tolerant environment for social innovation, and a state willing to recognize and incorporate popular wisdom into the cultural system. Establishing and maintaining such a virtuous cycle of two-way interaction is essential for achieving social integration and cultivating a shared sense of collective purpose.

In an era of intensifying globalization and geopolitical competition, the contest for national soft power has increasingly become a contest for cultural hegemony. Whether a country can construct a cultural system that is both cohesive and dynamic—one capable of effectively articulating and leading with core socialist values while remaining sufficiently open and inclusive to absorb new cultural demands emerging from civic life—directly concerns its long-term stability and developmental momentum. For individuals living within this system, understanding the co-constructive mechanisms between national culture and civic culture helps clarify the cultural environment they inhabit, enabling them to critically interpret the intentions embedded in different cultural messages and to cultivate reflective modern citizenship.

The digital age has fundamentally reshaped the field, modes, and rules governing the interaction between national culture and civic culture, introducing unprecedented complexity. Cyberspace is not only a new frontier for the efficient dissemination and innovative expression of national culture but also a "public sphere" where the vitality of civic culture flourishes and diverse opinions clash. While digital technologies empower individuals with unprecedented cultural agency, they also bring risks including information cocoons, cultural polarization, and online populism. Under these conditions, traditional top-down cultural governance models are increasingly unsustainable. Contemporary Chinese practice illustrates that the future of cultural governance must evolve toward a model that is more open, dialogical, refined, and intelligent. This model must uphold bottom-line principles while maximizing the cultural creativity of society as a whole, thereby seeking a new and higher-level dynamic balance between cultural guidance and cultural empowerment. Emerging disruptive technologies, such as artificial intelligence, the metaverse, and brain–computer interfaces, are poised to bring about even deeper transformations in cultural production, modes of interaction, and identity formation. As virtual and physical worlds become increasingly intertwined, new questions inevitably arise: How will the boundaries of national culture be redefined? How will the forms of civic culture evolve? And what unprecedented patterns of interaction will emerge between the two?? Regardless of how technology advances, the dialectical principle that national culture and civic culture are mutually dependent and mutually constitutive will remain the fundamental starting point from which we contemplate and construct a desirable cultural community for humanity in the uncertain future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C. Fu. and Q. Qi.; methodology, C.Fu.; formal analysis, C.Fu.; investigation, Q. Qi.; resources, C. Fu.; data curation, Y. Wang.; writing—original draft preparation, C. Fu., Y. Wang. and Q. Qi; writing—review and editing, Y. Wang.; visualization, Y. Wang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible through the provision of materials and investigative support from the National Institute for Cultural Development at Wuhan University and the School of Journalism and Communication at Wuhan University. Additional support was generously provided by the Hubei Provincial Federation of Social Sciences. We are deeply grateful for their assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Brzezinski, Z. Out of Control: Global Turmoil on the Eve of the Twenty-First Century, China Social Sciences Press: Beijing, 1994, p 235.

- Tomlinson, J., Globalization and Culture, translated by Guo Yingjian, Nanjing University Press: Nanjing, 2002, p 1.

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G. J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind 2nd edn, translated by Li Yuan, Sun Jianmin, China Renmin University Press: Beijing, 2010, p 224.

- Almond, Gabriel A., and Sidney Verba, eds. The Civic Culture Revisited. Boston: Little, Brown, 1980, pp 26–30.

- Assmann, J. Collective memory and cultural identity, New German Critique, (65), 1995,pp 125–133. [CrossRef]

- Assmann, J.Cultural memory and early civilization: Writing, remembrance, and political imagination, Cambridge University Press.