1. Introduction

The notion of resilience, initially proposed by Holling (1973), represents a shift toward alternative thinking about stability, adopting a systemic and holistic perspective that integrates social and ecological dimensions. This concept allows us to understand the internal and external configurations and dynamics of systems, facilitating the analysis of their behavior in the face of disturbances (Gunderson, 2000; Gunderson and Holling, 2002). Resilience is defined as the capacity of a system to absorb impacts and reorganize in the face of change, while maintaining its functionality (Holling, 1996; Walker et al., 2004).

In the socioeconomic context, resilience is key to explaining the internal effects of complex systems and to coping with adversities such as the COVID-19 pandemic, which profoundly transformed human activities in sectors such as education, politics, and the economy (Becken, 2013). In particular, the global health crisis underscored the importance of strengthening financial resilience (FR), understood as the ability of individuals to withstand and recover from economic shocks. This dimension is closely related to overall well-being, which connects directly with Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3: Good Health and Well-being (OECD, 2021). Furthermore, the drive toward financial inclusion, enhanced by the use of digital technologies, is a fundamental aspect of promoting effective financial education, which enables individuals to manage their resources responsibly. This need links financial resilience to SDG 4: Quality Education, by emphasizing the importance of inclusive and equitable education that prepares people to face economic challenges (Hamid et al., 2023; Flores et al., 2024). Furthermore, financial resilience is also related to SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth, as it strengthens individuals’ ability to maintain stable and productive employment and contribute to sustainable economic growth (Yadav and Shaikh, 2023). Data from the World Bank (2022) reveal that, although more than 1.2 billion adults accessed financial services between 2011 and 2017, approximately 1.7 billion remain excluded, primarily women in rural areas, highlighting the urgency of inclusive policies.

Recent research has demonstrated the importance of psychological and economic factors in financial resilience. For example, Kulshreshtha et al. (2023) show that financial and psychological resilience mediate the negative relationship between income shocks and financial well-being. Likewise, Mundi and Vashisht (2023) highlight that single mothers show higher levels of financial resilience, associated with their cognitive abilities. At the institutional level, the creation of the National Financial Resilience Index in the United States exemplifies the growing interest in measuring this variable to design effective public policies (Yao and Zhang, 2023).

In this context, this study focuses on characterizing financial resilience through the perceptions, experiences, and actions of university students, a key population for understanding how these capacities develop in a young, potentially vulnerable group. This research contributes to the global goals of improving overall health and well-being (SDG 3), ensuring quality education (SDG 4), and promoting economic growth with decent work (SDG 8), in line with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Financial resilience

Financial resilience has been conceptualized as the ability to withstand adverse financial situations. In other words, it could be understood as the capacity to face financial crises across contexts ranging from the global to the specific, whether at the individual, familial, or any other level at which people find themselves (BBVA, 2020). It is important to understand that while an individual’s capacity to confront certain economic events is crucial, financial inclusion must also be considered. Salignac

et al. (2019) point out that financial inclusion constitutes an important element for those included. Yet, criticism of this concept focuses on its practical aspects, overlooking its effects and roles in adverse situations. In line with this idea, Hamid

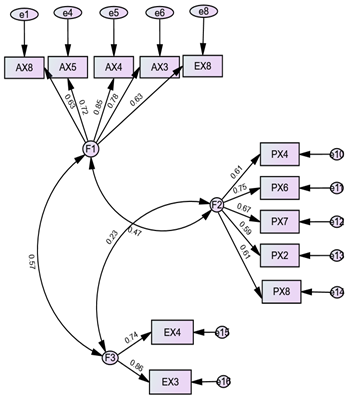

et al. (2023) propose a framework for measuring financial resilience and its relationship with sociodemographic variables, financial inclusion, financial literacy, and economic resources (

Figure 1).

Financial resilience is directly related to financial inclusion, as implementing certain actions to reverse some adverse economic situations is the moment when inclusion occurs. Hence, financial inclusion has become a policy priority for many countries. For example, Finland, Denmark, Sweden, and the Netherlands have introduced the right to a bank account for all; Belgium for the unbanked population; and France for those who have been denied a bank account (Gómez-Barroso and Marban-Flores, 2013). While financial inclusion is an important concept, it has been criticized for focusing on the delivery and practical aspects of financial products and services, ignoring the iterative effects and roles played by different actors to enable individuals to function effectively in adverse financial situations, the latter in relation to financial resilience (Salignac et al., 2016).

In summary, not everything has stemmed from the pandemic; it can also be triggered by job loss and health issues, among other factors, all of which can affect a family’s economy. However, there are ways to minimize the impact of these setbacks on financial health: saving, controlling debt, having an emergency fund, and good financial education (Flores et al., 2024). Therefore, household financial resilience, according to McKnight and Rucci (2020), is a dynamic concept referring to how households can quickly recover from financial crises. These crises are tackled through savings, loans from financial institutions or family and friends. Thus, financial resilience is the ability to adapt or persevere through predictable or unpredictable financial decisions, difficulties, or life impacts. Financial resilience enables individuals to recover from negative financial events.

Regarding financial resilience, interesting findings have been reported, such as the work of Salignac et al. (2019), who conducted a study in Australia, estimating that over two million adults showed high levels of financial vulnerability in 2015. The authors also identified that while respondents show good management of financial products and services, they have low levels of financial knowledge and behavior. Moreover, high levels in the financial products and services component indicate low dissatisfaction with basic financial products such as bank accounts, credit, and insurance. On the other hand, findings suggest that having employment does not necessarily lead to financial resilience, as part-time jobs and similar incomes are insufficient to cover people’s needs.

Similarly, financial resilience has been linked to life satisfaction or well-being, once again utilizing the moderating role of non-impulsive behavior and financial satisfaction (Tahir et al., 2022). This study demonstrated complete mediation between financial resilience and life satisfaction through financial well-being. Financial resilience and non-impulsive behavior have a positive influence on financial satisfaction, which undoubtedly relates to life satisfaction.

People with high levels of financial vulnerability face greater difficulties in obtaining funds in an emergency, limited access to financial services, poor financial knowledge and behavior, increased reliance on marginal and informal products, and social isolation (Salignac

et al., 2019). This is where the role of financial education plays an important role in strengthening financial resilience, especially in middle-aged individuals; conversely, in older individuals (>65), resilience tends to decrease (Bialowolski

et al., 2022). Achieving financial resilience requires the development of various programs. These programs need to reduce costs and increase insurance coverage, innovate credit mechanisms to invest in risk-mitigating technology, implement behavioral design to strengthen savings (such as self-insurance or investment), and utilize digital tools to facilitate government and social responses to crises (IPA, 2019)

1.

Principio del formulario

In addition to examining financial resilience in individuals and households, there is literature that has studied the effectiveness of innovation and financial resilience, now specifically in businesses, particularly in financial institutions. In one study, they combine the characteristics of the company, innovation, and financial resilience in financial institutions, significantly enhancing the survival prospects of such institutions (Nkundabanyanga et al., 2020). In another study related to financial institutions, the authors examine the mediating role of financial capability (FC), financial literacy (FL), and financial well-being (FW), to determine if future non-impulsive behavior moderates these associations. Again, the findings provide information regarding financial services, where there is limited literature explaining this phenomenon. Financial planners help improve consumer behavior in financial matters (Tahir et al., 2021).

Hussain et al. (2019) conducted research in Bangladesh and found that people with financial accounts had greater resilience than those without accounts. A significant relationship was established between gender and financial resilience, where men showed higher resilience. Additionally, the findings confirm the positive impact of education on financial knowledge regarding the need for financial sustainability. It was recommended to establish policies to achieve financial inclusion in rural areas, low-income individuals, women who are the primary breadwinners of households, and people with low levels of education. Financial fragility also appeared with greater impact among specific groups such as African Americans and low-income households (Lusardi et al., 2021).

Later, Ahrens and Ferry (2020), who analyzed the financial resilience of the government of England in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic, conducted another study. Their findings indicate that institutional capacity to absorb the shock of events like Covid-19 and adapt services was diminished during austerity in local governments. Hence, any model of financial resilience should consider absorption and adaptation during crises. Funds distributed to local governments are not subject to a framework considering need, deprivation, financial reserves of the authority, and local demographics, among other factors.

In this idea, McKnight and Rucci (2020) conducted a study involving 22 countries, analyzing data from each to differentiate variables and indicators of financial resilience. It was found that there are variations in financial resilience indicators among countries, possibly due to differences in financial institutions, social assistance, and cultural norms. The study classified countries according to four indicators: financially insecure (having savings of less than three months’ income), financially secure (having six months’ income saved), overindebted (having debts equal to or greater than three months’ income), severely indebted (having debts greater than six months’ income). In 15 out of 22 countries, it was found that fewer than half of households had sufficient savings to cover three months’ required income, and many not only lacked savings but were also in debt.

On the other hand, women heading households are more financially insecure in the majority of the 22 countries, except for Estonia, Slovenia, and Slovakia. Households with a lower-educated head are more financially insecure. Regarding housing, homeowners are less financially insecure. However, except for Canada, Greece, and Malta, homeowners with mortgages are less financially secure than renters. Regarding the labor market, retirees and self-employed workers tend to have greater financial security. Overall, individuals with higher incomes have less financial insecurity, but there is no linear relationship in the countries under study (McKnight and Rucci, 2020).

Recently, Kass-Hanna et al., (2021) conducted a study in countries in South Asia and Africa, which focused on investigating the relationship between digital and financial literacy, as well as behavior in financial resilience, including saving, borrowing, and risk management. Findings indicate that both digital and financial literacy are key factors in building inclusivity and financial resilience. It is also emphasized that financial literacy should be redefined to include digital literacy, thereby enhancing long-term financial resilience in households.

In summary, financial resilience has been analyzed with increased interest following the recent pandemic crisis (Yadav and Shaikh, 2023). The variables contributing to understanding this phenomenon relate to financial well-being, with financial and psychological resilience as mediating variables (Kulshreshtha et al., 2023). Additionally, financial resilience has been studied to comprehend how consumers in emerging markets perceive the present and future, and its relationship with public policies (Yadav and Shaikh, 2023). Similarly, financial resilience has been evaluated based on cognitive capacities with demographic control variables such as age, gender, education, and employment status, with results demonstrating influence on financial resilience in single fathers but not in single mothers, as the latter exhibit higher levels of financial resilience, along with cognitive capacities (Mundi and Vashisht, 2023). It is evident that financial resilience has become a concern for policymakers worldwide (Klapper and Lusardi, 2019; Bialowolski et al., 2022; Erdem and Rojahn, 2022; Yadav and Shaikh, 2023).

Financial Resilience and its alignment with the SDGs

Financial resilience is a topic that has increasingly captured the attention of scholars, as it has a direct impact on general well-being, inclusive education, and sustainable economic development. Several studies have been conducted in the literature that analyze everything from financial knowledge and behavior to individual skills. This study provides evidence on how university students view financial resilience, based on their perceptions, experiences, and the actions they have taken to address difficult financial situations in recent times. Thus, it contributes to SDG 3, promoting economic and psychological well-being; to SDG 4, strengthening financial education as an essential element of quality education; and to SDG 8, facilitating the development of skills for decent work and inclusive and sustainable economic growth.

Goal 3, which focuses on health and well-being, aims to ensure that everyone, regardless of age, can lead healthy lives and enjoy comprehensive well-being. This is a challenge that encompasses both physical and psychosocial aspects. Financial resilience is fundamental to this SDG, as economic well-being is closely linked to people’s emotional and psychological stability. According to the World Health Organization (World Health Organization, 2020), financial stress and economic insecurity are factors that can negatively affect mental and physical health, creating a vicious cycle that makes it difficult to adapt to difficult situations. This study aligns with SDG 3 by examining how university students manage their financial resilience in the face of economic crises, which has a direct impact on their overall well-being. The ability to cope with economic challenges not only improves financial health but also strengthens emotional and physical health, contributing to a more balanced and healthy life (OECD, 2021).

Goal 4, on quality education, seeks to ensure that everyone has access to inclusive, equitable, and high-quality education and promotes lifelong learning opportunities. Financial education plays a crucial role in this goal, empowering people to make informed economic decisions, manage their resources effectively, and successfully confront economic challenges. Without adequate financial education, opportunities for personal and professional growth are limited, which can lead to social and economic exclusion (United Nations, 2015). This study focuses on how financial education affects the resilience of university students, helping them cope with economic crises. By analyzing students’ perceptions, experiences, and actions in the face of financial hardship, it becomes clear how financial education impacts their ability to adapt and thrive in times of economic uncertainty. Thus, this study aligns perfectly with SDG 4, underscoring the importance of a comprehensive education that includes both academic knowledge and financial skills (OECD, 2021).

Goal 8 seeks to foster sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth, as well as ensuring full and productive employment and decent work for all. Financial resilience plays a fundamental role in this goal, as people who have a greater ability to adapt to economic crises are more likely to remain in the labor market and contribute to economic growth. The analysis of financial resilience among university students is closely related to SDG 8, given that young people are a group vulnerable to economic and social changes. Students’ ability to manage their personal finances, make informed decisions, and adapt to constantly changing work environments translates into better professional performance and, therefore, a greater contribution to the economic growth of their communities and countries (United Nations, 2015). By focusing the analysis on university students, this study aligns with SDG 8 by strengthening the skills necessary for decent work and creating an inclusive and sustainable economic environment through financial education.

Therefore, this study focuses on how university students view and manage economic crises through financial resilience. Emphasis is placed on their perceptions, lived experiences, and the actions they take to address these situations. In this sense, it relates to SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), SDG 4 (Quality Education), and SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth). It provides empirical evidence showing how financial resilience not only helps maintain stability but also helps to achieve a sustainable future.

4. Discussion

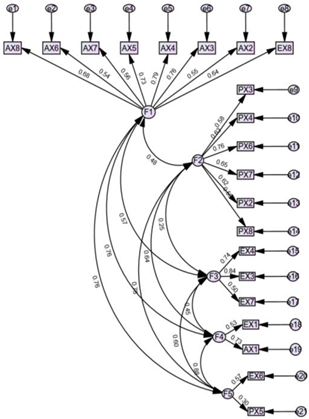

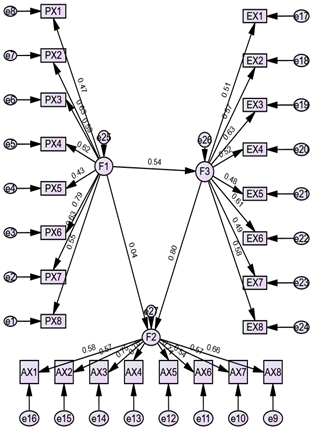

As we can see, the summary of the models with SEM shows a three-factor model with better fit. In relation to the number of factors, it agrees with the model proposed by Flores et al. (2024), however, the indices of goodness of fit, structural adjustment and parsimony of the final measurement model, exclude indicators that did not provide significant factor weights. This result constitutes a finding that adds to the state of the art. The behavior of the respondents perceives the financial health indicators of the scale used differently. Furthermore, the experiences lived and the actions they took in the face of an adverse financial situation are different from the population studied by Flores et al. (2024), which undoubtedly contributes to the empirical evidence on the topic. The eight indicators of financial well-being are related to savings, spending, credit history, debt payment and financial health insurance proposed by the Center for Education and Financial Capabilities of BBVA and the Center for Financial Services Innovation (CFSI) (BBVA, 2020).

In relation to factor 1, about actions carried out

In this eight-item factor, the actions taken by participants in response to certain financial crisis are measured. The topics include saving, spending, credit history, debt repayment, and insurance. The results indicate that only five of the eight items showed significant factorial weights. This allows us to understand that the participants in the study implemented a strategy to plan their expenses in the present and in the short term (ax8). Additionally, they have defined a strategy that enables them to sustainably manage their debts and pay them when required (ax5). To do this, they adopted some measures that allowed them to have enough savings and long-term assets to face the crisis they experienced (ax4), all of this derived from the plan they implemented to increase their savings in liquid financial products, with due anticipation (ax3). These actions allowed them to face the adverse financial situation they experienced regarding their expenses, which caused them to plan the expenses they will have in the short term and in the immediate future (ex8).

Factor 2, perception toward financial health indicators

This factor collects the opinion of the participants in six of the eight indicators of financial well-being. On the other hand, they say that it is advisable to have enough savings in liquid financial products (px3), in addition to having enough savings or long-term assets (px4). Additionally, they have a healthy credit history (px6) since they consider it important to have insurance appropriate to their needs (px7). Likewise, they agree that invoices must be paid on time and in full (px2), which is why it is important to plan expenses for the future (px8).

Factor 3 on lived experiences in relation to financial health indicators

Respondents indicate that they carried out actions to have sufficient savings or assets for the long term prior to the adverse financial situation, they experienced (ex4). Furthermore, this led them to implement a plan to increase their savings in liquid financial products (ex3). These actions seem to be limited to savings, whereas it would be convenient to strengthen other areas of personal finances such as insurance, credit history, budget control for proper management of personal finances. This result is not in concordance with the proposal of Flores et al. (2024), concerning the necessary and sufficient resources to face adverse situations. This result partially coincides with the proposal of Hamid et al. (2023), based on the conceptualization they make of the variables that are directly related to financial resilience, in this specific case, that of economic resources to face crises.

The result differs from the model proposed by Flores et al., (2024). For the perception factor, only six of the eight indicators of financial well-being, were validated. The factors of experiences lived in a financial crisis validated two of the eight indicators and finally for the actions they carried out to face the adverse financial situation, only four of the eight indicators. The variability in the results could indicate how complex it is to evaluate individuals; however, this is due to other factors that could be related to the models used, the control variables, and the cultural and social traits of the people who participate in the study, just to name a few.

5. Conclusion

The study uses structural equation models to understand the financial well-being of the population. A three-factor model that aligns with a previous proposal is identified. However, the validation process excludes indicators that do not contribute significantly; hence, it is pertinent to think that the perception of financial health differs between individuals. Actions taken in the face of financial crises focus on expense planning, debt management and long-term savings. Positive perception towards financial health includes aspects such as liquid savings, credit history and adequate insurance. The experiences lived are mainly related to savings, but the need to strengthen other financial areas is suggested. These findings contrast with previous proposals and show the complexity of evaluating financial well-being due to various factors such as control variables and cultural differences.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

The theoretical and practical implications of financial resilience are truly important and encompass many aspects. Individual financial resilience has a significant theoretical impact in areas such as psychology, behavioral economics, and financial planning. These implications help us better understand how financial experiences influence people’s behavior, well-being, and development over time. Based on the findings of this study, some of these implications are presented, which are aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), SDG 4 (Quality Education), and SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth).

Theoretical Implications

Human Capital Theory highlights how people’s knowledge, skills, and resources influence their ability to generate income and manage their finances. This directly connects to SDG 4 (Quality Education). This theory emphasizes the need for sound financial education that empowers people to make informed decisions about their economic well-being. Promoting comprehensive financial education in universities and other educational settings, especially among young people, not only strengthens their human capital but also helps them face economic challenges. This contributes to SDG 4, ensuring inclusive, equitable, and quality education for all. Financial Life Cycle Theory, meanwhile, shows us the different stages of a person’s economic life, from youth to retirement. This theory highlights how financial resilience allows people to adapt to changes in their income and needs over time. Furthermore, it is closely related to SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), as good financial management throughout life helps maintain economic stability and reduce the stress caused by financial insecurity. By fostering people’s ability to adapt and manage their resources effectively, financial resilience contributes to a healthier life, both physically and emotionally. Finally, Behavioral Financial Theory delves into how psychological and emotional factors affect our financial decisions and is closely related to SDG 8, which focuses on decent work and economic growth. Making well-informed and rational financial decisions can help people become more resilient in times of economic crisis, which not only supports their job stability but also contributes to a more inclusive economic environment. Fostering an understanding of these factors can open the door to decent work and ensure sustainable economic growth, empowering people to make financial decisions that benefit both their professional and personal development.

Practical Implications

Risk management and SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being) are key issues that go hand in hand. Strategies such as insurance, emergency savings, and income diversification are essential to strengthening the financial resilience of individuals and their families. These practices not only offer a safety net in the face of economic crises, but are also closely related to SDG 3. Good financial management can reduce the stress and anxiety that arise from unexpected situations, which in turn promotes better emotional and physical health. Thus, by fostering financial resilience through risk management, we are contributing to creating healthier and stronger communities. Long-term financial planning is key to strengthening our economic resilience. Setting financial goals, creating realistic budgets, saving for the future, and diversifying investments are strategies that help individuals and families ensure their economic stability. This relates to SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), as it enables people to access resources to start or obtain decent jobs, thus encouraging their active participation in economic growth. Furthermore, good financial planning promotes self-reliance and economic security, which is essential for a sustainable work environment.

Financial education is a fundamental tool for strengthening our economic resilience. By equipping people with the knowledge and skills needed to make informed decisions about their finances, SDG 4 (Quality Education) is supported. Good financial education enables individuals to better manage their resources, maximize their savings, and make wise choices about investments and retirement planning. Promote financial education at all levels.

Ethics statement.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Code of Ethics of Universidad Cristóbal Colón. The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Division of Graduate Studies and Research, in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) established in the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. All students provided their informed consent to participate in the study.

Conflicts of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding.

This research received no external funding.

Authors’ contributions

Author 1 was responsible for conceptualization, methodology, and formal analysis.

Author 2 was responsible for writing, revising, and editing the manuscript.

Author 3 was responsible for project administration, supervision, and validation.

Author 4 was responsible for data collection and curation.

Diagramm 1. Factorial solutionChi-square = 420.027; Degrees of freedom = 179; Probability level = .000

Diagramm 1. Factorial solutionChi-square = 420.027; Degrees of freedom = 179; Probability level = .000 Applying the tridimensional model, we have the next representation (Flores et al., 2024)

Applying the tridimensional model, we have the next representation (Flores et al., 2024)