Submitted:

05 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Inclusion & Exclusion Criteria

- Population: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and other sexual/gender minority (LGBT+) students enrolled in U.S. engineering or closely related programs at the undergraduate or graduate level. Studies may focus on any subset of this population (e.g., gay men, queer women, transgender or nonbinary students), and all racial/ethnic or other intersecting identities are included (the review considers such intersectional factors but not limit inclusion based on them).

- Phenomenon of Interest: Students’ experiences of identity negotiation and navigation of identity in the engineering education context, particularly as related to their sense of belonging (or lack thereof). This can encompass coming-out decisions, strategies for managing or disclosing one’s LGBT+ identity in academic settings, experiences of inclusion/exclusion, climate perceptions, and identity-related coping or support-seeking within the engineering program. Both subjective (qualitative reports of identity management, feelings of belonging) and objective measures (e.g., belongingness scales, persistence/attrition rates linked to identity) are of interest, with a primary emphasis on qualitative insights into identity negotiation.

- Context: Higher education engineering environments in the United States. This includes colleges of engineering, engineering departments within universities, and comparable settings (e.g., computer science or technical programs, if situated within an engineering or STEM faculty) in the U.S. Studies focusing on workplace experiences or K-12 settings were excluded unless they directly tie into college engineering programs (for instance, a study of an internship as part of an engineering curriculum could be included). The rationale is to capture the academic program context where sense of belonging is developed.

- Study Types: All types of empirical studies and credible reports were considered. This encompasses peer-reviewed research (qualitative studies, quantitative surveys, mixed-methods, longitudinal studies, etc.), conference papers, theses and dissertations, technical reports, and other gray literature that present data on the population of interest. Including gray literature is essential to minimize publication bias and capture the full scope of evidence (Systematic reviews: Search strategy). There was no date restriction – literature from any publication year was included to allow a comprehensive historical to present-day view. The only language limitation is that reports should be in English (since the focus is U.S. programs).

Search Strategy

- Database Searching: I have searched a broad range of scholarly databases covering education, engineering, and social sciences: Scopus, Web of Science, Engineering Village (Compendex), IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, ERIC (Education Resources Information Center), and SocINDEX, on top of other sociology/psychology databases that index studies on identity and education. Each database is searched from its earliest records through the present (with no year limit).

- Search Terms: A carefully constructed search string was be used, incorporating various synonyms and keywords for the core concepts of (a) LGBT+ identity, (b) engineering/STEM context, and (c) education. For example, the query includes a block of LGBT-related terms (e.g., LGBT, LGBTQ, LGBTQIA+, queer, sexual minority, transgender, gay, lesbian, bisexual, trans), combined with a block of terms for engineering education context (e.g., engineering, STEM, science, technology, technical, higher education, university, college). Boolean operators join these terms. An illustrative example (adapted to a multi-database search) is:

- Gray Literature: To capture dissertations, technical reports, and other gray literature, I searched ‘ProQuest Dissertations & Theses’ for any dissertations or theses on LGBT students in engineering. I also searched relevant conference proceedings (e.g., ASEE and FIE conference paper databases) and organizational reports. For instance, the ASEE (American Society for Engineering Education) conference paper database and ASEE PEER repository was searched with similar keywords, as several known studies in this area have been published in conference format. I used Google Scholar and general Google searches to find reports or white papers by advocacy or professional groups (such as National Center for Engineering Pathways to Inclusion or Pride in STEM reports, if any). Including these sources is important to reduce publication bias; in fact, the inclusion of grey literature in the search is recommended to help minimize publication bias and ensure comprehensive results (Systematic reviews: Search strategy).

- ○

-

Google and Google Scholar Searches

- ■

- Search strings used:

- “LGBT engineering students”

- “queer engineering education”

- “LGBT in STEM undergraduate experiences”

-

“LGBTQ engineering climate survey”

- ■

- For each search, I screened the first 100 results, consistent with recommendations for systematized grey-literature searches.

- ■

- Inclusion was based on title/abstract relevance to the Population–Interest–Context (PICo) framework.

- ○

-

Conference Archives and Repositories

- ■

- Search strings used:

- ■

- I manually searched:

- ASEE PEER repository (using the internal search function with “LGBT,” “queer,” “diversity,” “STEM identity,” “engineering climate”).

-

Frontiers in Education (FIE) Conference Proceedings (search terms: “LGBT,” “queer,” and “marginalized students”).

- ■

- All available years were included.

- ■

- Results were screened at the abstract level.

- ○

-

Advocacy Group Publications

- ■

- The archives of LGBTQ-in-STEM organizations (e.g., oSTEM, LGBTQ+ Physicists, and Pride in STEM) were searched using each site’s built-in search or annual report listings.

- ■

- Only documents containing empirical data or climate findings relevant to engineering or STEM were retained.

- Citation Snowballing: In addition to database searches, I employed backward and forward citation tracking (also known as snowballing). For backward citation chasing, reference lists of all included studies and key relevant papers were reviewed to identify earlier studies that my searches might have missed (Marosi, Avraamidou, & López, 2024). For forward citation chasing, I used Google Scholar or Scopus to see if the key studies (e.g., known foundational papers like Trenshaw et al. 2013 on LGBT engineering students) have been cited by more recent publications. This “pearl growing” approach (starting from known important studies and expanding) helps ensure I capture seminal pieces and any very recent studies that might not yet be indexed in databases (Marosi, Avraamidou, & López, 2024).

- Search Documentation: I recorded the search process in detail, noting the date of each search, the exact search strings used for each database, and the number of results retrieved. For transparency and reproducibility, a search log table was created (as suggested by PRISMA Item 6) documenting each information source, the date searched, and any limits used.

Screening Process

- Deduplication: First, all references retrieved from different sources are merged, and duplicate records are removed. Automatic de-duplication tools in the reference manager are used, supplemented by a manual check to ensure no duplicates remain. For example, if the same conference paper was found via IEEE Xplore and also via Scopus, it was counted only once.

- Title/Abstract Screening: In the first round of screening (Round 1), I screened the titles and abstracts of all unique records to assess their relevance to the review topic. I applied the inclusion criteria liberally at this stage (i.e., “wide net” approach) – any study that potentially involves LGBT+ students in engineering and identity/belonging is marked for full-text review. Studies clearly not meeting criteria (e.g., those about “LGBT in STEM” but focusing on faculty, or an unrelated health study) are excluded at this stage. To ensure reliability, each record’s title/abstract is checked (Page, et al., 2021). I used a screening form with quick yes/no/eliminate options based on key criteria. Where the reviewer is unsure, the reference was advanced to the next stage (to err on the side of inclusion). The number of records excluded in this round (with general reasons like “out of scope” or “irrelevant”) is recorded.

- Full-Text Screening: All studies that passed the initial screen underwent full-text review (Round 2). The full publications were retrieved and read in full. Using a pre-defined full-text screening checklist (based on the inclusion criteria), the reviewer determined whether each study should be included. Reasons for exclusion were documented for each study excluded at this stage (e.g., “Population not in engineering,” “No relevant outcome data,” or “Not empirical data”). I expected common exclusion reasons might be context mismatch (e.g., study is about LGBT students in general higher education with no engineering-specific analysis) or insufficient focus on identity negotiation (e.g., the study mentions LGBT students but only in passing).

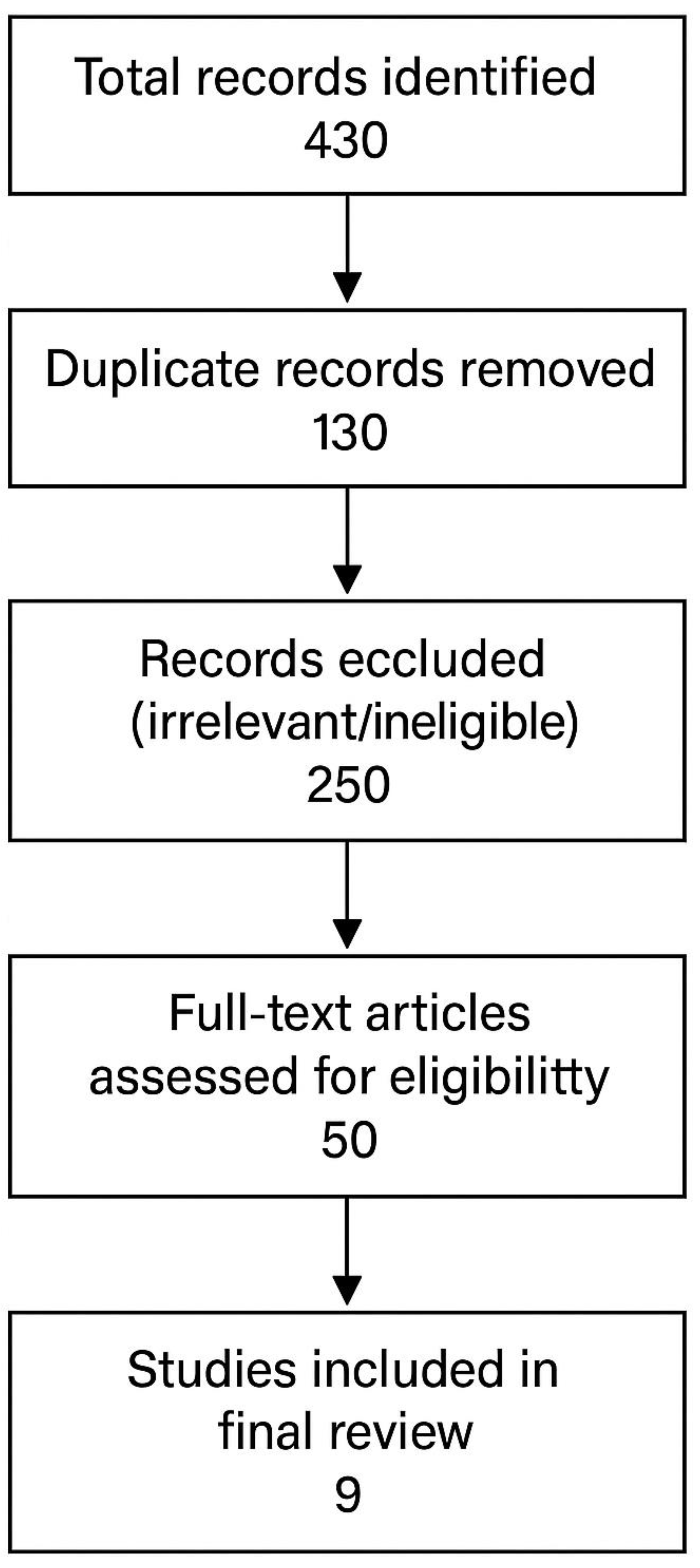

- PRISMA Flow Diagram: I compiled a PRISMA 2020 flow diagram- Figure 1, to record the study selection process (Page, et al., 2021). The diagram detailed the number of records identified, how many were excluded at each stage (with brief reasons for full-text exclusions), and the final number of studies included. This transparent reporting follows the PRISMA standard and allows readers to see how I arrived at my sample.

Final Articles

Quality Assessment of Included Studies

Primary Research Questions and Sub-Questions

- What are the experiences of identity negotiation and sense of belonging among LGBT+ undergraduate and graduate students within U.S. engineering education programs?

- Sub-question: How do transgender and nonbinary engineering students, in particular, experience identity negotiation and belonging, and what unique challenges do they face in seeking acceptance within their programs?

- Sub-question: What strategies do LGBT+ engineering students use to navigate or manage their identities (e.g., engaging in “covering” behaviors or selective disclosure of their sexual orientation/gender identity), and how do these strategies impact their sense of authenticity and belonging?

- 2.

- How do institutional and cultural factors in U.S. engineering programs influence the inclusion, climate, and sense of belonging of LGBT+ students?

- Sub-question: To what extent do engineering curricula and faculty training or teaching practices promote LGBT+ inclusion, and how do such academic practices affect LGBT+ students’ classroom experiences and comfort in lab or classroom settings?

- Sub-question: What role do peer networks and LGBT+-focused student organizations (e.g., campus engineering pride groups or oSTEM chapters) play in building community and support for LGBT+ students in engineering, and how do these co-curricular spaces contribute to students’ sense of belonging?

- Sub-question: What challenges to inclusion do LGBT+ students encounter in the culture of engineering education (e.g., heteronormativity, cisnormativity, discrimination, or lack of visible role models), and what opportunities or strategies have been identified to address these challenges and foster a more inclusive environment?

- 3.

- In what ways do LGBT+ students’ experiences in engineering – regarding identity negotiation, campus climate, and belonging – influence key outcomes such as academic engagement and performance, retention in engineering programs, and mental health and well-being?

- Engineering schools are “notoriously inhospitable” to LGBT+ students; the emotional toll of being an LGBT+ engineer, whether closeted or out, can push them out of the field (Maloy, Kwapisz, & Hughes, 2022).

- LGBT+ engineering students describe a chilly, heteronormative climate with a culture of silence; many conceal their identities as a survival mechanism, although having an “out” mentor or inclusive faculty can encourage them to persist (Cross, Farrell, & Hughes, 2022).

- Transgender and gender-nonconforming students continued in STEM at ~10% lower rates than cisgender students; those who more frequently sought counseling were 21% less likely to stay, suggesting that mental health stresses and lack of support contribute to higher attrition (Cech & Waidzunas, 2011).

- Reported hostile or exclusionary incidents and a “chilly” climate in engineering for LGBT+ individuals, underscoring challenges that inform my review questions (Cross, Farrell, & Hughes, 2022).

- Suggested that heteronormativity in engineering require LGBT+ students to downplay their identities – a form of covering – to be seen as “professional,” aligning with my interest in identity negotiation strategies (Cech & Waidzunas, 2011).

Data Extraction

| Stage | Records (n) |

| Identification | |

| Scopus | 120 |

| Web of Science | 90 |

| Engineering Village (Compendex) | 80 |

| IEEE Xplore | 30 |

| ACM Digital Library | 20 |

| ERIC | 50 |

| SocINDEX | 40 |

| Total records identified | 430 |

| Duplicate records removed | 130 |

| Screening | |

| Records screened (title & abstract) | 300 |

| Records excluded (irrelevant/ineligible) | 250 |

| Eligibility | |

| Full-text articles assessed for eligibility | 50 |

| Full-text articles excluded | 41 |

| Included | |

| Studies included in final review | 9 |

|

Study |

Study Type | Population & Context | Relevance to Identity/Belonging |

| (Cech & Waidzunas, 2011) | Qualitative (interviews) | LGB undergraduate engineering students (U.S. universities) | Explores how LGB students cope within a chilly, heteronormative engineering climate by “passing” as straight or downplaying their identity. Highlights identity management tactics used to navigate engineering culture and the impact on students’ sense of inclusion. |

| (Trenshaw, 2013) | Quantitative (campus climate survey – preliminary results) | LGBT engineering undergraduates at a large Midwestern university (UIUC) | Found that LGBT students reported a chillier climate in engineering – “more situations of exclusion within engineering than in other areas of campus.” Students called for greater visibility of LGBT people in engineering and mentoring support to improve belonging. |

| (Development, 2017) | Qualitative (narrative interviews & focus group) | 7 openly gay male engineering undergraduates (single U.S. campus) | Examines how gay students make sense of and reconcile their engineering identity with their sexual identity. Found that engineering’s masculine, heteronormative culture led students to downplay or compartmentalize their gay identity (“manage by not managing”) to fit in. This identity negotiation was driven by a desire to belong in the engineering program. |

| (Hughes, 2018) | Quantitative (national longitudinal survey) | ~4,000 STEM undergraduates in the U.S. (incl. engineering; 8% identified LGBQ) | Demonstrates a persistence gap: LGBQ STEM students were significantly more likely to leave STEM majors than heterosexual peers. Notably, students who were “out” about their LGBTQ identity had different retention outcomes than those not out. Highlights how a non-inclusive academic climate and lower sense of belonging may contribute to higher attrition of sexual minority students in engineering/STEM. |

| (Cech & Rothwell, 2018) | Quantitative (survey study) | 1,729 engineering undergraduates across 8 U.S. universities (141 LGBTQ identified). | Large-scale study showing LGBTQ engineering students experience significantly more marginalization and devaluation in their programs than non-LGBTQ peers. They also reported lower social “fit” and sense of acceptance, and more negative health outcomes, largely mediated by the chilly climate. Suggests that a widespread heteronormative culture in engineering undermines LGBTQ students’ sense of belonging. |

| (Linley, Renn, & Woodford, 2018) | Qualitative (grounded theory interviews) | 15 LGBTQ undergraduate STEM majors (incl. engineering) in U.S. colleges. | Investigates LGBTQ students’ experiences through an ecological systems lens (interpersonal, institutional, societal factors). Identified multilevel stressors – e.g. lack of belonging and visibility in their departments and curriculum – that negatively impact LGBTQ students. Students navigated identity disclosure on campus carefully, seeking out affirming micro-environments while feeling “invisible” in engineering spaces. Offers insights into how campus climate, peers, and faculty influence LGBTQ students’ sense of inclusion. |

| (Yang, Sherard, Julien, & Borrego, 2021) | Qualitative (interviews & narrative analysis). | LGBTQ+ engineering undergraduates (multiple U.S. institutions; study by UT Austin researchers) | Focuses on how LGBTQ engineering students actively resist marginalization and build affirming communities. Participants described tactics of “queer resistance” to heteronormativity in their programs and the creation of peer support networks as a means to foster belonging. Despite hostile climates, many found resilience through LGBTQ student groups or alliances, using community-building to affirm their identities and improve their engineering experience. |

| (Pradell L. R., Parmenter, Galliher, Berke, & Rowley, 2024) | Qualitative (phenomenological interviews) | 10 LGBTQ+ engineering students (undergrad & grad) at U.S. universities | Explores how LGBTQ+ students navigate engineering education and how engineering culture affects their well-being. Found a pervasive norm of avoiding LGBTQ identity expression – a culture of “minimal tolerance” that effectively silences students. This forced invisibility led to feelings of isolation and identity conflict, undermining students’ sense of safety and belonging in engineering. Calls attention to the need for more affirming, openly inclusive engineering environments to support LGBTQ student well-being. |

| (Pradell L. R., Parmenter, Galliher, & Berke, 2024) | Qualitative (thematic analysis of interviews) | 10 LGBTQ+ engineering students (same sample as above, U.S.) | Centers on students’ own recommendations to improve inclusion and belonging. Participants emphasized increasing feelings of safety in engineering programs – e.g. implementing visible ally training, integrating LGBTQ-inclusive content, and fostering supportive classroom norms. They identified invisibility and isolation as root problems and urged campuses to proactively address these to enhance LGBTQ students’ sense of belonging. The study highlights student-driven strategies for creating a more welcoming engineering culture. |

| Study | Clear Research Aims | Appropriate Methodology/Design | Data Collection & Context | Data Analysis Rigor | Validity / Trustworthiness | Conclusions Supported by Evidence | Overall |

| (Cech & Waidzunas, 2011) | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| (Trenshaw, 2013) | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| (Development, 2017) | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| (Hughes, 2018) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| (Cech & Rothwell, 2018) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| (Linley, Renn, & Woodford, 2018) | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| (Yang, Sherard, Julien, & Borrego, 2021) | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| (Pradell L. R., Parmenter, Galliher, Berke, & Rowley, 2024) | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| (Pradell L. R., Parmenter, Galliher, & Berke, 2024) | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| Study | Trans/Nonbinary Students’ Identity Negotiation & Belonging | Identity Management Strategies & Impact on Authenticity/Belonging |

| (Cech & Waidzunas, 2011) | Focused focused on LGB students; although one genderfluid participant was included, trans/nonbinary experiences were not analyzed separately, and heteronormative culture likely heightened their sense of otherness. | LGB students felt only tolerated and coped by concealing or downplaying identity, which eroded authenticity and belonging. |

| (Trenshaw, 2013) | Included one genderfluid student but no trans-specific issues; heteronormative culture and lack of initiatives constrained belonging for all LGBTQ participants, including trans/NB students. | LGBT students used selective disclosure and covering to avoid conflict in a straight male-dominated culture, leaving them invisible and inauthentic. |

| (Development, 2017) | Focused only on cisgender gay men, excluding trans/NB voices; findings cannot be generalized, though heteronormative contexts would likely heighten challenges for gender-diverse students. | Gay students ‘managed by not managing,’ staying out only to friends while avoiding faculty disclosure, which kept them invisible and limited belonging. |

| (Hughes, 2018) | Examined LGBQ students only, so trans/NB experiences were outside scope; focus was on coming out as a factor in engagement rather than gender identity negotiation. | Sexual minority students often stayed closeted or selectively out to avoid bias, a strategy that reduced authenticity and belonging compared to peers who were openly out.” |

| [3] | Trans/NB students were included but not analyzed separately; results noted transphobia as linked to homophobia, implying a hostile climate that likely hindered their belonging. | LGBTQ students used passing, covering, and compartmentalization to cope in devaluing spaces, but these tactics added emotional burden and isolation, undermining authenticity and belonging. |

| (Linley, Renn, & Woodford, 2018) | Included LGBTQ STEM students broadly; while trans/NB voices weren’t singled out, the male-centered ‘dude culture’ and silence around LGBTQ identities likely made their identity negotiation especially difficult. | LGBTQ STEM majors compartmentalized—hiding identity in engineering while expressing it elsewhere—allowing survival but leaving them inauthentic and strained in belonging. |

| (Yang, Sherard, Julien, & Borrego, 2021) | Sample likely included trans/NB students but gave no separate analysis; all faced a heteronormative culture, with trans/NB students—like LGB peers—relying on community-building to find belonging while remaining marginalized in formal spaces. | LGBT+ students resisted exclusion by forming peer networks and mentoring ties, creating spaces to be authentic and belong despite an unwelcoming culture. |

| (Pradell L. R., Parmenter, Galliher, Berke, & Rowley, 2024) | Explicitly included trans/NB students, who—like peers—faced a culture of ‘minimal tolerance’ that silenced difference, leaving them invisible and struggling to feel they belonged. | Students felt pressured to silence LGBT+ identity to appear ‘professional,’ a strategy that shielded them from backlash but caused isolation and loss of authenticity. |

| (Pradell L. R., Parmenter, Galliher, & Berke, 2024) | Using the same sample, recommendations—though not identity-specific—highlighted that greater LGBT+ visibility and inclusive policies are needed for trans/NB students to feel genuinely accepted. | Students survived by staying invisible or seeking support outside, but urged programs to boost LGBT+ visibility so future peers needn’t hide, linking openness to greater authenticity and belonging. |

| Study | Inclusive Curricula & Faculty Practices (Classroom Inclusion) | Peer Networks & Student Organizations (Community Support) | Cultural Challenges (Heteronormativity, Discrimination) & Strategies for Inclusion |

| (Cech & Waidzunas, 2011) | Engineering courses ignored LGBT+ issues, with no diversity discourse or faculty acknowledgment, leaving queer students invisible in class. | With no in-engineering support groups and weak ties to campus LGBT+ resources, queer students felt isolated and lacked peer networks in their field. | Engineering’s heteronormative culture left LGBT+ students merely tolerated; they urged more visibility and mentorship from out faculty/grad students to improve climate. |

| (Trenshaw, 2013) | Engineering classes never addressed LGBT+ issues, and untrained faculty offered no inclusion efforts, forcing students to separate identity from academics. | LGBT+ groups had little visibility in engineering, leaving students unaware of resources and alienated without an engineering-specific network.” | Students faced more exclusion in engineering than elsewhere on campus, prompting calls for LGBT+ visibility and mentoring programs to counter bias and foster inclusion. |

| (Development, 2017) | Programs operated under a ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ norm where orientation was deemed irrelevant; faculty avoided inclusion, though Safe Space training and ally signals were recommended. | Lacking in-department groups, students leaned on campus LGBT centers or informal friends for support, underscoring the need for dedicated engineering networks. | A culture of silence and hegemonic masculinity left LGBT+ students unwelcome; Hughes urged Safe Zone training, inclusive policies, and visible allyship to break this norm. |

| (Hughes, 2018) | STEM curricula assumed heterosexuality, reinforcing bias; Hughes urged faculty to use inclusive practices and trainings so LGBT+ students feel recognized. | Groups like oSTEM were seen as vital, offering community, mentorship, and visibility that countered isolation and strengthened belonging. | Heterosexist stereotypes and a chilly climate pushed LGBT+ students to hide; Hughes recommended Safe Zone training, role models, and student orgs to foster inclusion. |

| [3] | Engineering programs lacked LGBT+-inclusive content or training; authors recommended Safe Zone education, inclusive language, pronoun use, and zero-tolerance policies to foster welcoming classrooms. | Authors urged programs to partner with oSTEM and LGBT centers, boost visibility of LGBT+ engineers, and support student orgs to build affirming peer communities. | Anti-LGBT+ bias and systemic heteronormativity marginalized students; Cech & Rothwell urged nondiscrimination policies, gender-neutral facilities, and visible celebration of LGBT+ engineers to foster inclusion. |

| (Linley, Renn, & Woodford, 2018) | Engineering curricula stayed strictly technical, ignoring gender/sexuality and signaling irrelevance of LGBT+ topics; more inclusive content could improve climate. | With few engineering peer networks, many sought community in other fields; authors stressed that in-department groups like oSTEM could greatly improve well-being and belonging. | Engineering’s entrenched ‘dude culture’ centered cis-het male norms, reducing LGBT+ belonging; authors urged diversity policies, identity dialogue, and challenging bro culture to improve climate. |

| (Yang, Sherard, Julien, & Borrego, 2021) | Curricula ignored LGBT+ perspectives, leaving inclusivity to student-led efforts; participants urged faculty and administrators to integrate inclusion into teaching and practices. | Without formal support, LGBT+ students built grassroots networks and safe spaces, which became vital for solidarity, support, and belonging in isolating programs. | Students faced hetero- and cis-normative bias but resisted through openness and peer support, creating micro-climates of inclusion; authors urged structural changes so the burden isn’t only on students. |

| (Pradell L. R., Parmenter, Galliher, Berke, & Rowley, 2024) | Engineering curricula and faculty upheld a ‘culture of silence’ on LGBT+ issues, signaling low tolerance; authors urged training and curriculum changes to normalize inclusion. | Participants lacked in-department community and felt isolated; authors called for visible, well-supported LGBT+ groups to provide affirming peer networks. | Engineering norms silenced LGBT+ expression, leaving students unsafe, conflicted, and isolated; authors urged safe environments, open dialogue, and supportive communities to shift culture. |

| (Pradell L. R., Parmenter, Galliher, & Berke, 2024) | Students urged greater LGBT+ visibility in curriculum, faculty DEI training, and explicit support from professors to replace invisibility with acknowledgment. | Students urged programs to support oSTEM, events, and mentorship networks, seeing visible LGBT+ groups as crucial to reduce isolation and foster belonging.” | Persistent hetero/cisnormativity and lack of role models sustained exclusion; students urged DEI leadership, visibility of LGBT+ engineers, and explicit support policies to move from tolerance to true inclusion. |

| Study | Academic Engagement & Performance (Effect on involvement, academic success) | Retention in Engineering Programs (Persistence or departure rates) | Mental Health & Well-Being (Psychological stress, isolation, confidence) |

| (Cech & Waidzunas, 2011) | Marginalization left LGB students feeling only tolerated, reducing confidence, draining energy through hiding, and undermining academic focus and integration. | Hostile climate and weak integration made LGB students feel they didn’t belong, increasing risk of leaving engineering for more accepting fields. | Heteronormative climate forced exhausting coping and suppression, leaving LGB students stressed, isolated, and at risk of anxiety or burnout. |

| (Trenshaw, 2013) | Frequent exclusion and lack of LGBT+ content reduced students’ engagement, collaboration, and self-efficacy, as energy was diverted from academics to coping. | Though retention data weren’t collected, Minority Stress Theory and prior work suggest exclusionary climates reduce LGBT+ commitment and heighten attrition risk. | Isolation and hostility left LGBT+ students alienated and fatigued, with anxiety, low self-esteem, and the constant mental burden of self-censorship. |

| (Development, 2017) | Gay students maintained strong engineering identity and high performance, but stigma limited authenticity in class and mentoring, adding pressure despite success. | Participants persisted due to strong engineering identity, but Hughes warned the silent climate could mask retention risks and influence future career choices. | Constant vigilance caused unease and stress for gay students, risking anxiety and low worth; small peer support and pride in engineering offered some resilience. |

| (Hughes, 2018) | LGBQ students showed high engagement, even exceeding peers in research, yet retention lagged—implying climate, not performance, hindered persistence. | LGBQ STEM students were ~8% less likely than peers to persist after four years, showing a climate-driven retention gap unrelated to ability or interest. | Hostile climates pushed LGBQ students to hide, causing stress, anxiety, and isolation that harmed well-being and drove some out of STEM; supportive communities were noted as protective. |

| [3] | LGBT+ students felt their contributions devalued, which reduced confidence, participation, and opportunities, indirectly harming engagement and performance. | Though attrition wasn’t measured, widespread bias and marginalization across schools likely threaten LGBT+ retention, aligning with evidence of higher STEM dropout rates. | LGBT+ students reported worse wellness than peers—stress, burnout, and depressive symptoms—directly tied to marginalization and devaluation in engineering. |

| (Linley, Renn, & Woodford, 2018) | Exclusionary culture reduced LGBT+ engagement in engineering, but affirming microsystems boosted participation and performance, showing inclusion fosters academic growth. | Findings suggest STEM loses LGBT+ talent through attrition or self-selection, as unfriendly climates drive students to other fields or away from long-term commitment. | Non-affirming engineering climates forced identity suppression, causing stress, anxiety, and low belonging; affirming communities served as protective factors. |

| (Yang, Sherard, Julien, & Borrego, 2021) | Resistance and peer community-building enhanced learning and performance, while lacking such support led to disengagement and emotional strain that hurt academics. | Community-building acted as a retention aid, giving LGBT+ students allies and purpose; without such networks, isolation might have pushed them to leave. | Heteronormative culture strained mental health, but community-building offered affirmation and resilience, even as daily resistance remained taxing. |

| (Pradell L. R., Parmenter, Galliher, Berke, & Rowley, 2024) | A culture of silence kept LGBT+ students guarded in class and groups, limiting collaboration and opportunities; lack of safety hindered engagement and long-term development. | Though many stayed, enduring an inequitable culture meant questioning their place; such precarious persistence risks burnout, dropout, or avoiding further engineering study. | Engineering culture left LGBT+ students isolated and invisible, fueling stress, anxiety, and low self-worth; authors urged affirming communities to ease these burdens. |

| (Pradell L. R., Parmenter, Galliher, & Berke, 2024) | Students linked poor inclusion to stress and lower confidence, reducing engagement; supportive faculty and inclusive classrooms boosted participation and academic success. | Students stressed that improving culture, curriculum, and community is key to retaining LGBT+ peers, as hostile climates drive many to quietly endure or leave. | Lack of safety and inclusion caused stress, alienation, and anxiety for LGBT+ students; participants urged visibility, culture change, and community to improve well-being. |

Results and Discussion

Results

Identity Negotiation in Engineering Programs

Impacts on Sense of Belonging

Support Systems for LGBT+ Inclusion in Engineering

Discussion

Implications for Engineering Education

Recommendations for Practice

- Implement LGBT+ training for faculty and staff: Invest in comprehensive professional development on LGBT+ inclusion for engineering instructors and TAs. Training should cover respectful communication (e.g., using correct pronouns and inclusive language) and equip faculty to recognize and interrupt bias or harassment in classrooms. Building faculty competence and allyship in these areas is critical to reducing the invisible biases that often go unchecked in engineering courses.

- Cultivate inclusive classroom practices: Instructors can take proactive steps to signal that all students are welcome. For example, adding a diversity & inclusion statement to syllabi (and emphasizing it on day one) sets a tone of respect. Professors should invite students to share their preferred names and pronouns privately, to avoid misgendering. It is also important to immediately address any discriminatory comments or jokes in class as teachable moments that reinforce professional norms of respect. By normalizing discussions of diversity in engineering (for instance, mentioning contributions of LGBT+ engineers in lectures or examples), educators can help dispel the notion that sexual orientation or gender identity are irrelevant in STEM. Such inclusive pedagogical practices benefit LGBT+ students’ sense of belonging and encourage all students to develop cultural competency.

- Strengthen LGBT+ student networks and mentoring: Engineering colleges should actively support LGBT+-focused student organizations (like oSTEM chapters or queer-in-STEM groups) and related peer networks. Providing faculty advisors, funding, and space for these clubs – and recognizing their events as valued parts of the community – helps build visible support systems on campus. Research shows that the presence of affinity groups correlates with reduced victimization and greater safety for LGBT+ students. Schools can also facilitate peer mentoring or “buddy” programs that connect incoming LGBT+ students with more senior LGBT+ or ally peers, helping newcomers navigate the engineering culture with guidance from someone who shares similar experiences. Additionally, creating physical and virtual safe spaces (e.g., a dedicated diversity lounge or regular meet-ups) where sexual and gender minority students can find community is important for combating isolation. By bolstering these peer support structures, institutions can foster a stronger sense of belonging among LGBT+ engineering students.

- Enforce inclusive policies and leadership support: At the institutional level, ensure that nondiscrimination policies explicitly protect sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression, and that these policies are visibly communicated and rigorously enforced. There should be confidential, effective mechanisms for reporting any bias or harassment, signaling that such behavior will not be tolerated. Universities and engineering colleges should also provide inclusive facilities – for example, all-gender restrooms and locker rooms in engineering buildings – and adopt administrative practices that respect students’ identities (allowing use of affirmed names/pronouns on class rosters, email, and ID systems). High-level leadership should regularly voice support for LGBT+ inclusion as a core value of the college. When deans and department heads publicly champion diversity and hold faculty accountable for maintaining an inclusive climate, it legitimizes LGBT+ issues within engineering culture and empowers others to act. In summary, strong institutional policies and visible commitment from leadership are necessary to create an environment where LGBT+ engineering students can fully participate and thrive.

Conclusion

Declarations

Author Contributions

Funding

Availability of data and material

Code availability

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

References

- Bakka, B., Bouchard, T., Chou, V.X.-w., & Borrego, M. (2023). Modeled Professionalism, Identity Concealment, and Silence: The Role of Heteronormativity in Shaping Climate for LGBTQ+ Engineering Undergraduates. ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition. Baltimore, MD.

- Bilimoria, D., & Stewart, A. (2009). " Don't Ask, Don't Tell": The Academic Climate for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Faculty in Science and Engineering. NWSA Journal, 21(2), 85-103.

- Boudreau, K. e. (2018). Exploring Inclusive Spaces for LGBTQ Engineering Students. CoNECD Conference.

- Bramer, W.M., Giustini, D., de Jonge, G.B., Holland, L., & Bekhuis, T. (2016). De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 104(3), 240-243. [CrossRef]

- Browning, J.W., Bustard, J., & Anderson, N. (2024). Queering Software Engineering Education: Integrative Approaches and Student Experiences. 21st International Conference on Information Technology Based Higher Education and Training (ITHET), (pp. 1-8). Paris, France. [CrossRef]

- Cech, E.A., & Rothwell, W.R. (2018). LGBTQ inequality in engineering education. Journal of Engineering Education, 107(4), 583–610. [CrossRef]

- Cech, E.A., & Waidzunas, T.J. (2021). Systemic inequalities for LGBTQ professionals in STEM. Science Advances, 7(3). [CrossRef]

- Cech, E., & Waidzunas, T. (2011). Navigating the heteronormativity of engineering: the experiences of lesbian, gay, and bisexual students. Engineering Studies, 3(1), 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Cross, K.J., Farrell, S., & Hughes, B.E. (2022). Queering STEM Culture in US Higher Education: Navigating Experiences of Exclusion in the Academy. (K. J. Cross, S. Farrell, & B. E. Hughes, Eds.) New York, NY, USA: Taylor & Francis. [CrossRef]

- Development, J. o. (2017). ‘Managing by Not Managing’: How gay engineering students manage sexual orientation identity. 58(3), 385–40. [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91-108. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, B.E. (2018). Coming out in STEM: Factors affecting retention of sexual minority STEM students. Science Advances, 4(6). [CrossRef]

- Linley, J., Renn, K., & Woodford, M. (2018). Examining the ecological systems of LGBTQ STEM majors. Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering, 24(1), 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Maloy, J., Kwapisz, M.B., & Hughes, B.E. (2022). Factors Influencing Retention of Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Students in Undergraduate STEM Majors. Life Sciences Education, 21(1). [CrossRef]

- Marosi, N., Avraamidou, L., & López, M.L. (2024). Queer individuals’ experiences in STEM learning and working environments. Studies in Science Education. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.M. (2003). Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J., McKenzie, J.E., Bossuyt, P.M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T., Mulrow, C.D., . . . al, e. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372(71). [CrossRef]

- Pradell, L.R., Parmenter, J.G., Galliher, R.V., & Berke, R. (2024). LGBTQ+ engineering students’ recommendations for sustaining and supporting diversity in STEM. International Journal of LGBTQ+ Youth Studies, 22(31), 361-391. [CrossRef]

- Pradell, L.R., Parmenter, J.G., Galliher, R.V., Berke, R.B., & Rowley, L. (2024). The identity-related experiences of LGBTQ+ students in engineering spaces. International J.ournal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 37(8), 2267–2287. [CrossRef]

- Rankin, S., Schoenberg, R., & Sanlo, R.L. (2002). Our Place on Campus: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender Services and Programs in Higher Education. Greenwood Press.

- Systematic reviews: Search strategy. (n.d.). Duke Medical Center Library & Archives, Duke University. Retrieved from https://guides.mclibrary.duke.edu/sysreview/search.

- Trenshaw, K. e. (2013). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender students in engineering: Climate and perceptions. Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), (pp. 1238–1240). [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.A., Sherard, M.K., Julien, C., & Borrego, M. (2021). Resistance and community-building in LGBTQ+ engineering students. Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering, 27(4), 1-33. [CrossRef]

- Yoder, J.B., & Mattheis, A. (2016). Queer in STEM: Workplace Experiences Reported in a National Survey of LGBTQA Individuals in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Careers. Journal of Homosexuality, 63(1), 1-27.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).