Submitted:

05 December 2025

Posted:

08 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Literature Review

1.2.1. Overview of Studies in China

1.2.2. Overview of International Research

1.3. Research Objectives and Questions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.2. Research Methodology

2.2.1. Literature-Analysis Method

2.2.2. Field-Survey Method

2.2.3. Inductive and Comparison Methods

2.2.4. Case-Analysis Method

2.2.5. Phenomenology Method

3. Results

3.1. Design Rules of Chinese Pavilions: The Unity of Natural Scenery and Cultural Symbols

3.1.1. The Formal Characteristics of Chinese Pavilions

- A square pavilion

- 1)

- Qingquan Pavilion

- 2)

- Nanyang Pavilion

- 3)

- Haoshang Pavilion

- 4)

- Yangwu Pavilion

- 2.

- Hexagonal pavilion

- 1)

- The Jingsi Pavilion

- 2)

- Shiji Pavilion

- 3)

- Octagonal pavilion

3.1.2. Cultural Symbols of Chinese Pavilions

- 1

- Chinese pavilions are cultural symbols that express the beauty of nature

- 1)

- The meaning of Qingquan Pavilion: Clear spring water

- 2)

- The meaning of Aixiao Pavilion: Love the morning, love college days

- 2.

- Chinese pavilions are cultural symbols that express people's moral cultivation

- 1)

- The meaning of Jingsi pavilion: to encourage people to think quietly

- 2)

- The meaning of Yangwu Pavilion: to nurture a person's integrity of justice

- 3)

- The meaning of the Haoshang Pavilion: To be a wise and kind person

- 3.

- Chinese pavilions are cultural symbols that encourage people to contribute to society

- 1)

- The meaning of the Nanyang Pavilion: to enhance morality and learning and to establish achievements for the country

- 2)

- The significance of the Grand Records Pavilion: Creating great literary works

3.2. Poetic and Moral Experience of the "Fourfold" of Chinese Pavilions

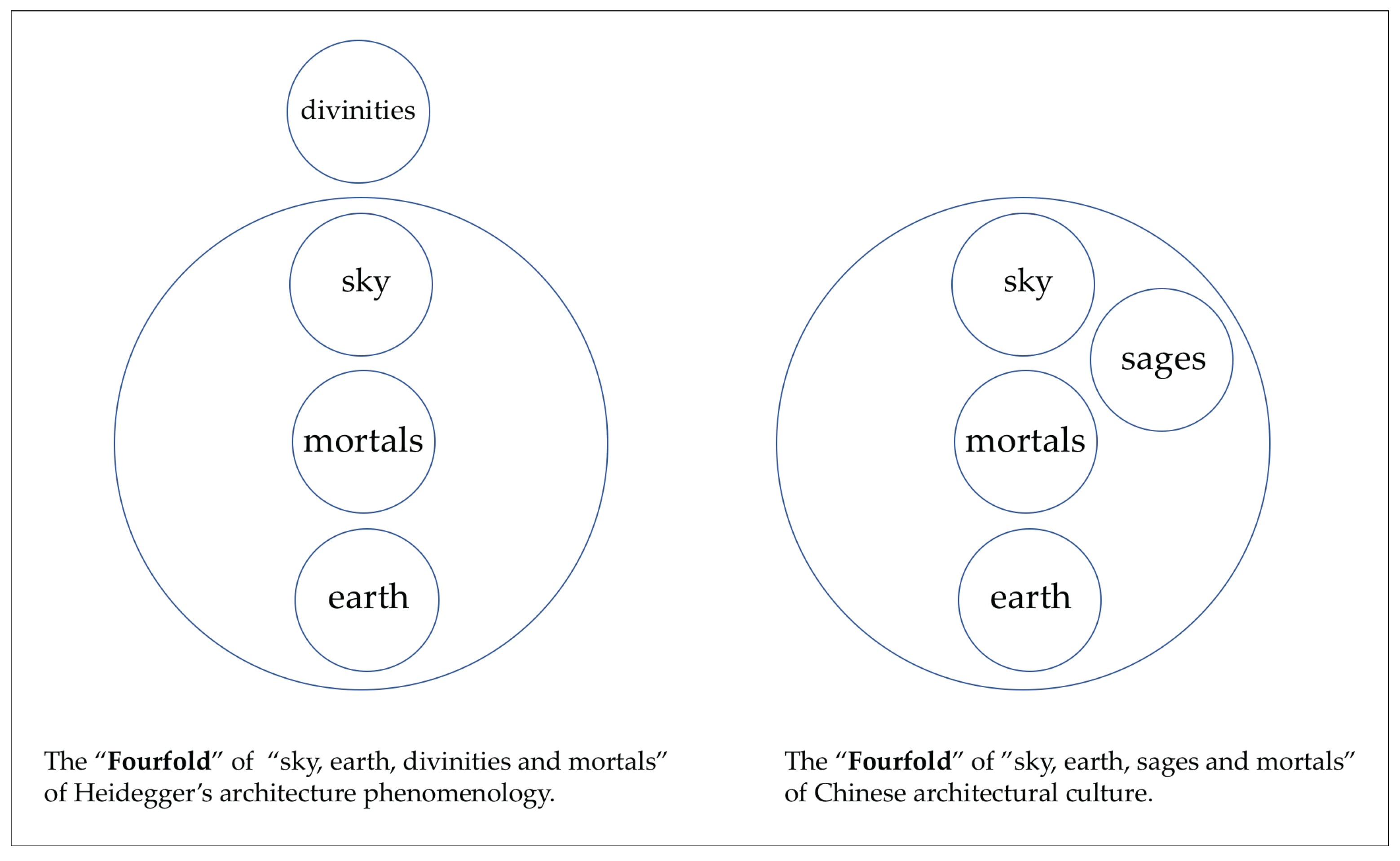

3.2.1. The Difference Between the "Fourfold" of the Chinese Pavilion and Heidegger's "Fourfold"

3.2.2. A Phenomenological Description of the "Fourfold" Living Experience of Chinese Pavilions

- The natural experience of Chinese pavilions: There is both distinction and integration between man and nature

- 2.

- Cultural Experience of Chinese pavilions: mortals and sages can engage in free dialogue beyond time and space

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- 1)

- The architectural attributes of Chinese pavilions are manifested as the unity of natural scenery and cultural symbols. Its architectural design concept reflects the Chinese people's pursuit of natural beauty and noble morality, and is a reflection of Chinese aesthetic and ethical concepts.

- 2)

- The spiritual attributes of the Chinese pavilion are manifested in the "Fourfold" structure of sky, earth, sages and mortals. This is its architectural cultural code. Chinese pavilions blend secular life with human beliefs, providing the mortal with a lofty spiritual experience.

- 3)

- The Chinese pavilion is not just a standalone building, but an integrated space that is organically combined with the natural environment. The Chinese pavilion must be surrounded by "three elements" - trees, water and mountains. This is a typical manifestation of the artistic consistency between Chinese landscape painting and Chinese architecture.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, Z. On the Aesthetic Connotation of Pavilion Imagery in Ancient Chinese Literary Texts. Social Sciences in Yunnan 2012, 1, 156–160. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J; Zhang, Y. On the Pavilion Stories among Occult and Mysterious Fictions during Han - Wei Period. Journal of Nankai University (Philosophy, Literature and Social) 2008, 3, 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z. The spatial consciousness and expression of poetry and prose in ancient pavilions and pavilions. Literature and Art Criticism 2015, 2, 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T. The Cultural Signification of Caotang and Kongting in theNarrative Structure of Ancient Chinese Landscape Paintings. Art Magazine 2020, 4, 114–119. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, C. The New Space and Time of “Qu Shui Liu Shang”: The Patterns and Moral Direction in Wen Zhengming's Lanting Painting. Art Research 2014, 2, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L. A Study on the Cultural Function of Landscape in Gardens of Intelectuals in the Song Dynasty. Journal of Ocean University of China (Social Sciences) 2017, 1, 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y; Teng, M. A Study of pavilion on relief stones during the Han Dynasty. Archaeology and Cultural Relics 2015, 2, 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J; Zeng, Y; Chen, T. Analysis of construction technology on Wangyue Pavilion of Golden Phoenix Temple in Ya'an. Building Structure 2014, 44(09), 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J; Mo, F. Quantitative analyses of the acoustic effect of the pavilion stage in traditional Chinese theatres. Applied Acoustics 2013, 32((04), 290–294. [Google Scholar]

- He, J. The Spatial Poetic with Stone & Bamboo Architectural & Landscape Reconstruction of an Old Tea Mill. Architectural Journal 2021, 5, 51–53. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y; Liu, M. A Study of The Materials and Techniques Used in The Polychrome Ceiling Decoration of The Linxi Pavilion in The Garden of The Cining Palace. Palace Museum Journal 2018, 6, 45–63+159. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S; Liu, X. Landscape Art of Jade Island’s Pavilions in Beihai Park. ZHAUNGSHI 2018, 1, 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B; Guo, W. Research on the Westernization of Chinese Pavilions in China and Europe in 18th Century: Case Study on Cassan Park Pavilion and Wanhuazhen Pavilion. ZHUANGSHI 2019, 3, 98–101. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J; Zhang, H. Smoke Waves Chasing Water Moon Language Pavilion:A Brief Analysis of the Cultural Expressions in the Historical Evolution of Jiujiang Yanshui Pavilion. Cultural Relics in Southern China 2020, 6, 283–285+301. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y. Lyrical Presence and Absence: Social Interactions and Emotions in the Pavilion. Art Observation 2022, 10, 54–57. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y; Wang, J. The Joy of "Yuyan Pavilion": Wu Kuan's Garden Pavilion for Friendship and Writing. New Arts 2023, 44(05), 77–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, M; Wei, X. The Subjectivity Consciousness in the Garden Poems and Proses of Song Dynasty. Journal of Shanxi University ( Philosophy & Social Science) 2023, 46(03), 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T. The Sacred Land in the Mountains: The Spatial Narrative of “Pavilion” in Traditional Chinese Landscape Painting. Theoretical Studies in Literature and Art 2023, 43(06), 163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y; Xu, C. A Study of the Album of the Humble Administrator’s Garden: Focusing on the Huaiyu Pavilion. Heritage Architecture 2023, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C; Bai, Y; Wang, C. Born from Water, Transformed by Environment: Evolution of the Baihe Pavilion at Jinci Temple in Taiyuan, Shanxi Province. Heritage Architecture 2025, 2, 98–105. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, S; Yan, M; Li, Z; Cheng, G; Yang, X. Study on the Spatial Restoration and Gardening Characteristics of Wu's Garden Pavilion in Xiuning in Song Dynasty. Chinese Landscape Architecture 2024, 40(02), 138–144. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z; Yan, X; Ren, C. Digital Translation of Traditional Structure: A Case Study Based on Parametric Design and the Construction of Mortise and Tenon Timber Pavilions. South Architecture 2024, 5, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y; Yuan, X. The Flow of "Lanting": Garden Experience of Guangzhou Intellectuals through Purification Ceremonies during Late Qing Period. Chinese Landscape Architecture 2025, 41(07), 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L; Zhang, Z. Rethinking the End of Chinoiserie: A Case Study of the Chinese Pavilion at Pillnitz Palace in Dresden. Art Magazine 2025, (10), 138–147. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. The Hills Surrounding Chuzhou: A Study on The Old Drunkard’s Arbour from the Perspective of Heideger’s Concept of Befindlichkeit. Journal of Tongji University(Social Science Edition) 2025, 2, 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Christian Norberg‐Schulz. Genius Loci: Towards A Phenomenology of Architecture. Translated by Shi, Z. Huazhong University of Science and Technology Press: Wuhan, China, 2017; pp. 3‐4.

- Deng, B. Heidegger's Philosophy of Architecture and Its inspiration. Studies in Dialectics of Nature 2003, 12, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X. Exploring Western Philosophy: Selected Works by Deng Xiaomang; Shanghai Literature and Art Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2014; p. 326. [Google Scholar]

- Ivashko, Y.; Kus ́nierz-Krupa, D.; Chang, P. History of origin and development, compositional and morphological features of park pavilions in Ancient China. Landsc. Archit. Sci. J. Latv. Univ. Agric. 2019, 15, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Song, T.; Milani, G.; Abruzzese, D.; Yuan, J. An iterative rectification procedure analysis for historical timber frames: Application to a cultural heritage Chinese Pavilion. Eng. Struct. 2021, 227, 111415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, C.; Hu, C. Kiln–House Isomorphism and Cultural Isomerism in the Pavilions of the Yuci Area: The Xiang-Ming Pavilion as an Example. Buildings 2024, 14, 3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Shape | Side length | Height |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qingquan Pavilion | Square | 3.77 m | 3.62 m |

| Nanyang Pavilion | Square | 4.00 m | 4.15 m |

| Haoshang Pavilion | Square | 4.37 m | 4.22 m |

| Yangwu Pavilion | Square | 8.81 m | 6.13 m |

| Jingsi Pavilion | Hexagonal | 1.80 m | 2.83 m |

| Shiji Pavilion | Hexagonal | 2.65 m | 4.31 m |

| Aixiao Pavilion | Octagonal | 4.00 m | 7.12 m |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).