Submitted:

05 December 2025

Posted:

05 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.2. Motivations

1.3. Contribution

- A profit-aware EV utilisation model (PAUM-EV-M1) is developed for charging location and optimal route selection for conventional EVs;

- A profit-aware EV utilisation model (PAUM-EV-M2) is developed charging–discharging location and optimal route selection for V2G-enabled EVs;

- Extended the PAUM-EV-M2 models (PAUM-EV-M2b) to work under the flexibility and uncertainty of demand-side resources.

2. Profit-Aware Electric Vehicle Utilisation Model (PAUM-EV)

2.1. Proposed PAUM Objective Function

2.2. PAUM Systems Modelling

2.2.1. EV System Model

2.2.2. PG System Model

2.2.3. CG System Model

2.3. PAUM-EV-M1: Profit-Aware Charging Location and Optimal Route Selection

2.4. PAUM-EV-M2: Profit-Aware Charging–Discharging Location and Optimal Route Selection

2.5. PAUM-EV-M2b: Extension of PAUM-EV-M2 Considering the Demand Flexibility

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Simulation Set-Up

- The EV arrival and departure time and energy level, battery capacity and efficiency information are availed from the dataset referred in [26].

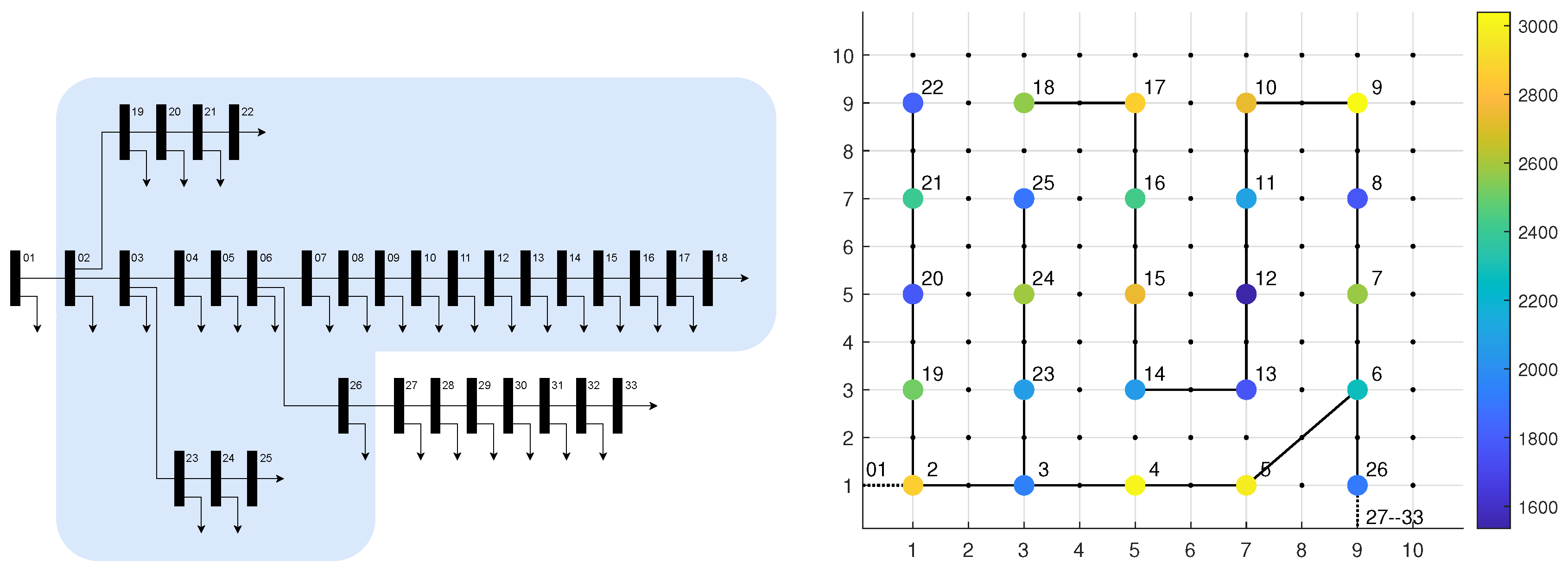

- Power grid system information, such as power generation, non-elastic load, and radial distribution line topology are collected from the IEEE 33 Bus system data [27].

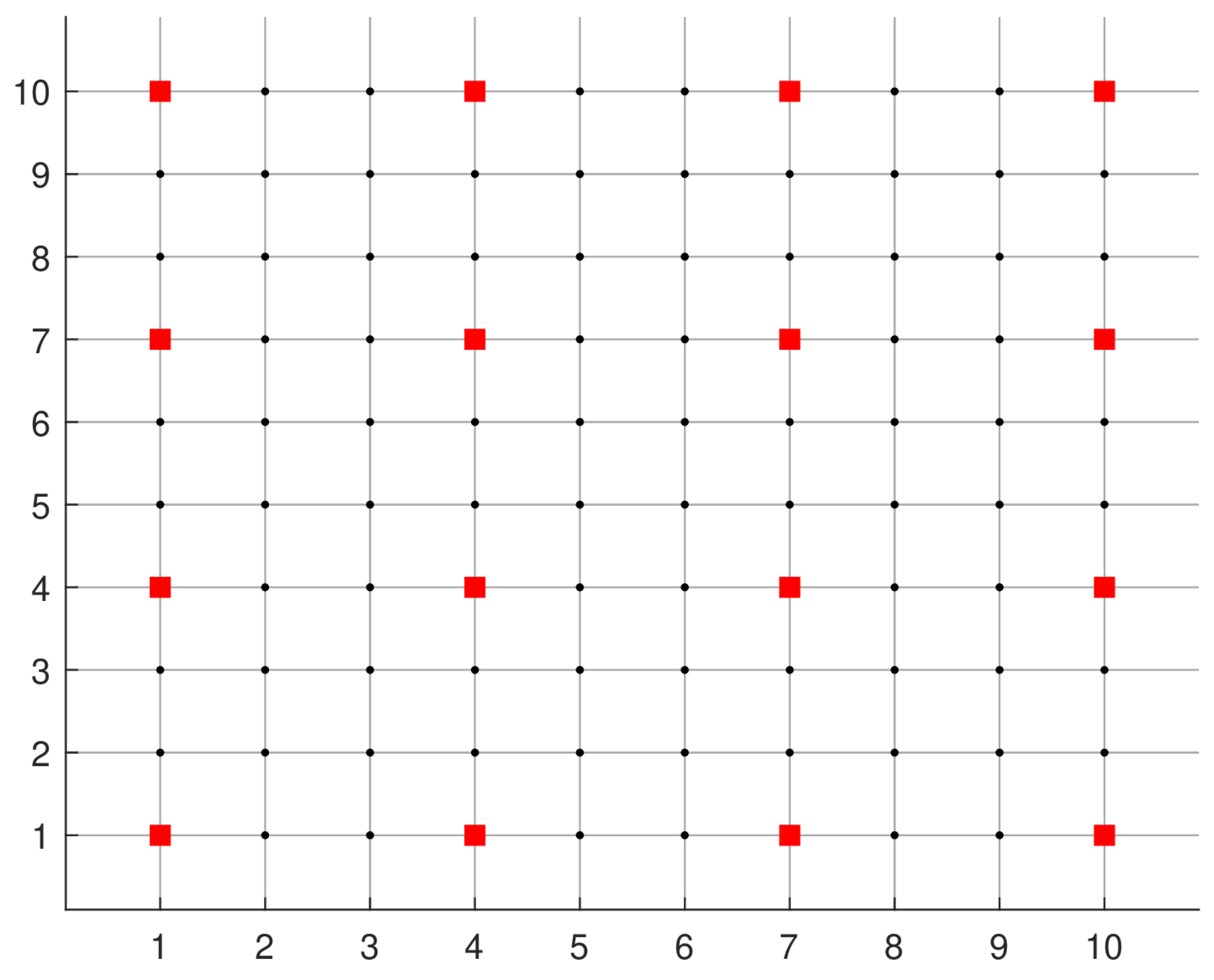

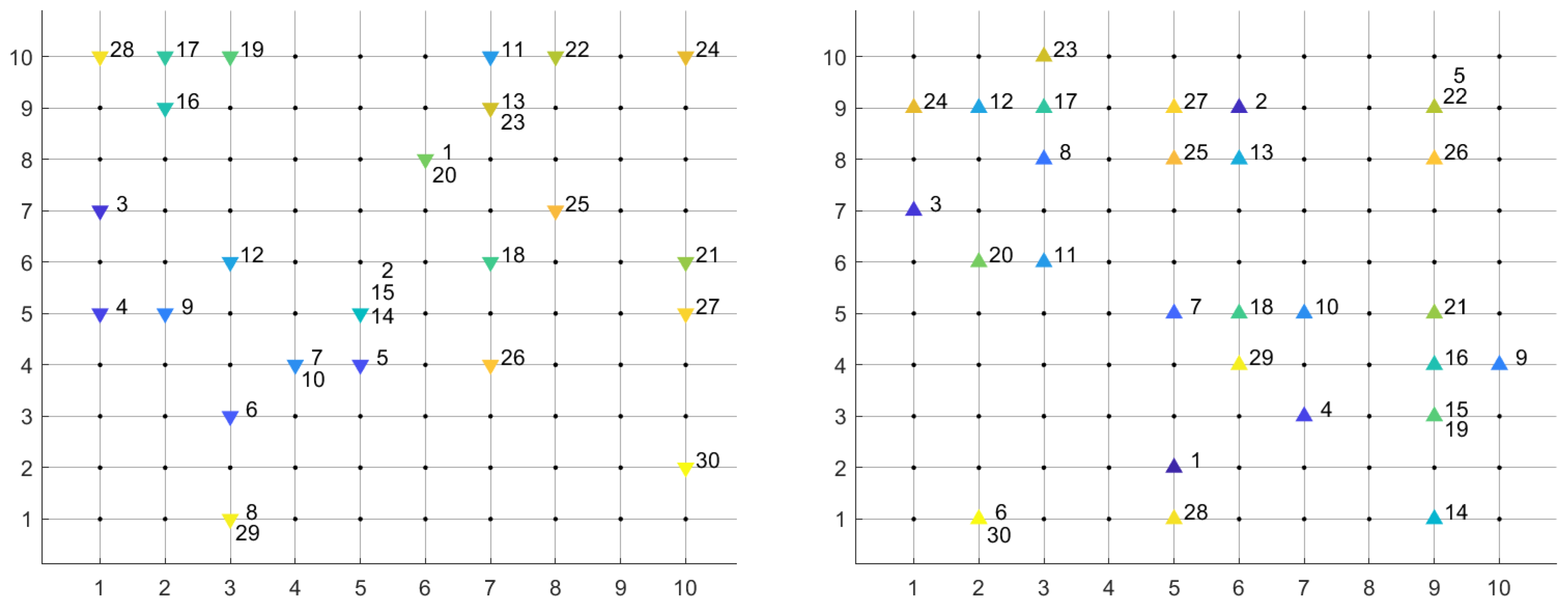

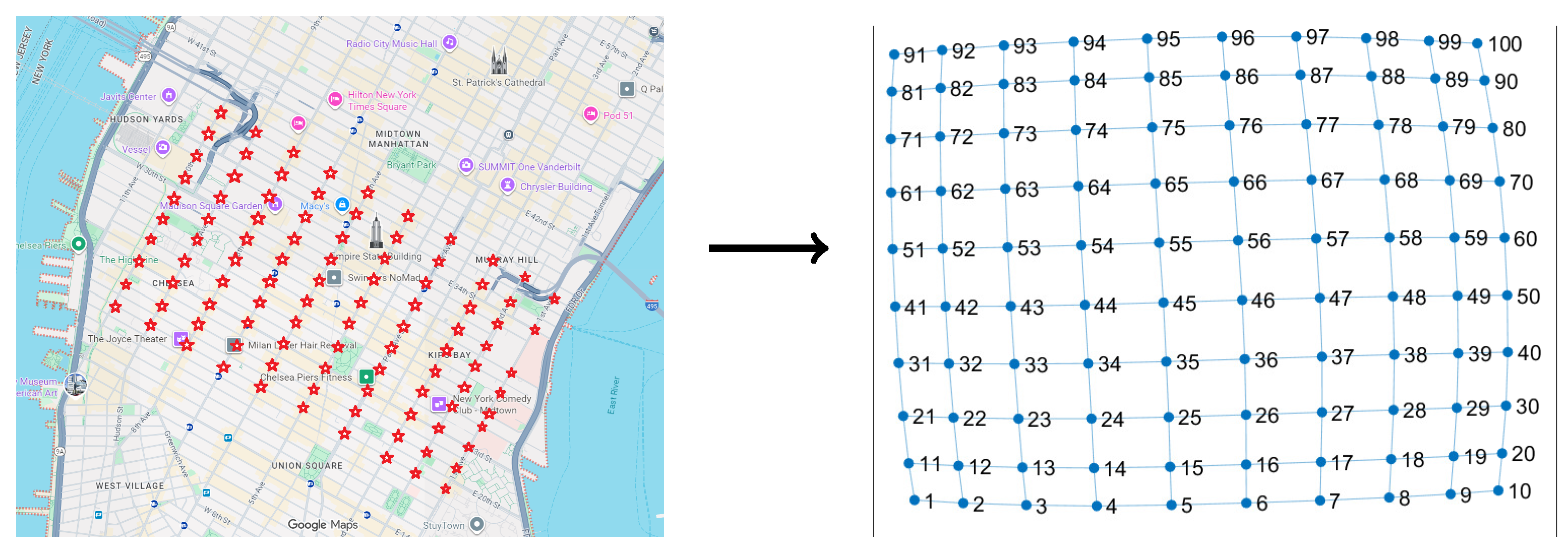

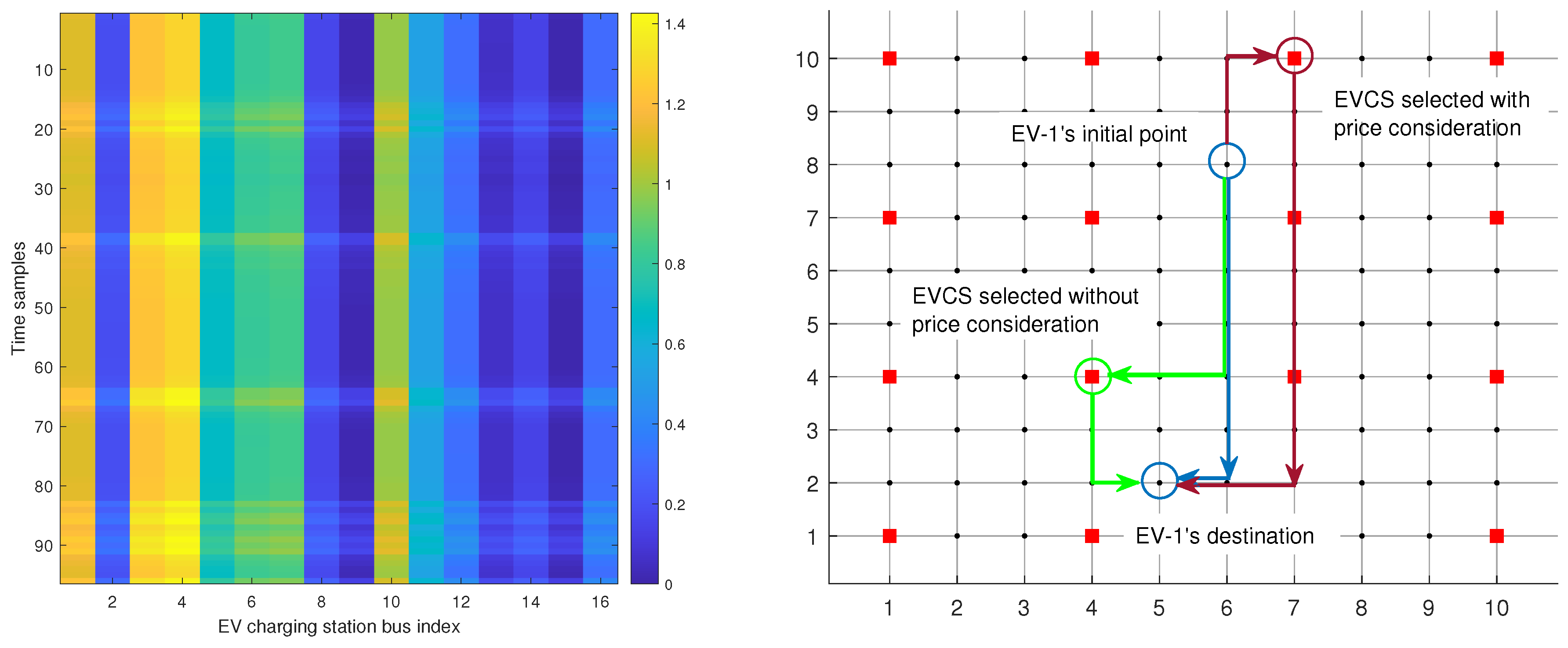

- City’s road grid information is derived from an check-board pattern city, like Manhattan in New York, where each junction (graph vertices) is approximately equidistantly placed. In the present study, the graph edge weight is assumed to be 5km uniformly, shown in Figure 1. It can easily be extended to non-uniform weights as shown in Figure 3.

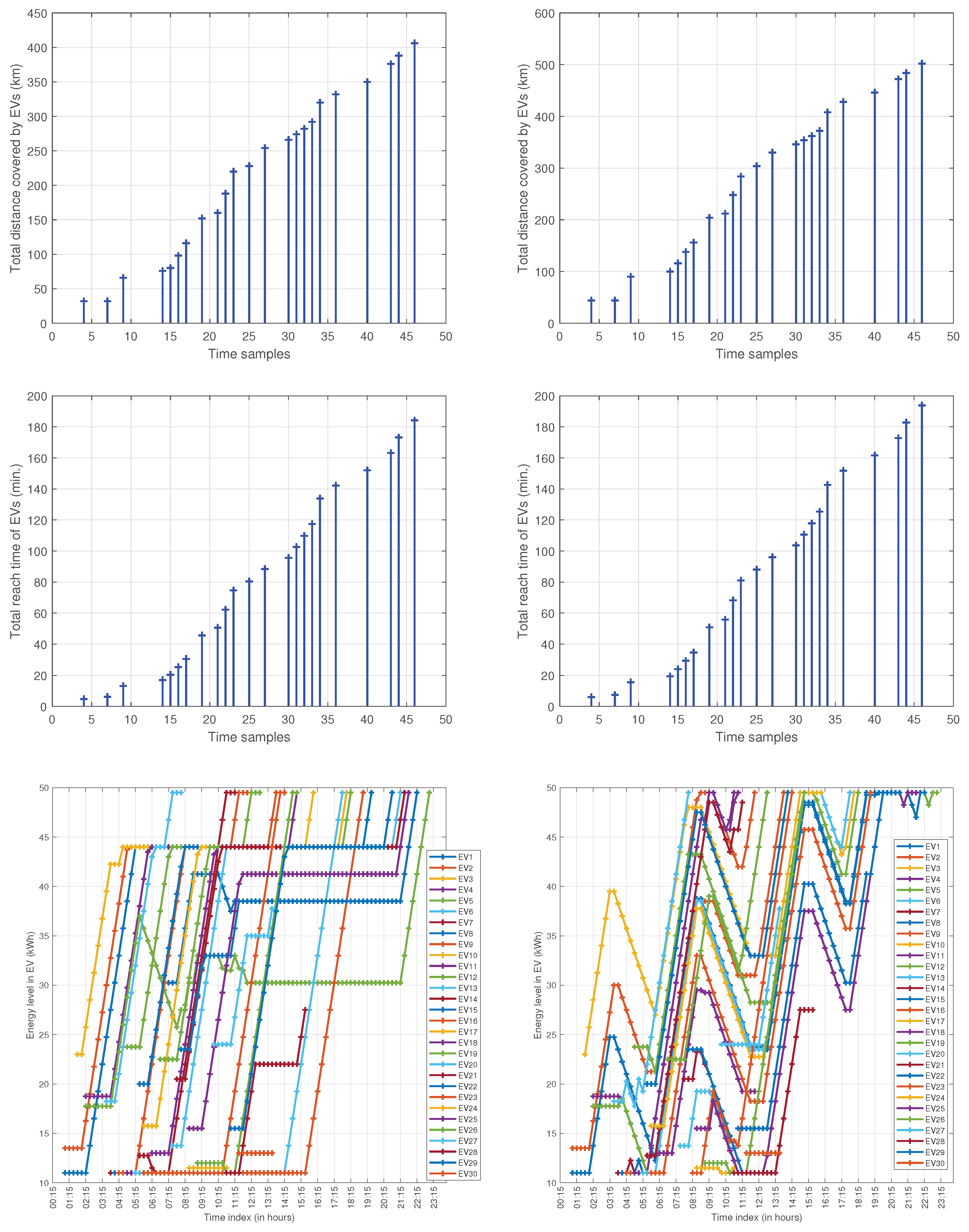

3.2. Case-1: Charging Schedule of EV, EVCS Location and Route Selection

3.4. Case-3: Charging and Discharging Schedules Along with Demand Management

4. Conclusions and Future Works

- Both M1 and M2 can yield more profit for EVs compared to their traditional counterparts, e.g. $260 and $390 in this case, while doing a minimum re-routing of the EVs. M2 is capable of obtaining better financial benefits than M1 (around $80), but it is subjected to technical feasibility at the EV and EVCS end.

- The enhanced model M2b, flexible demand management can further contribute towards reducing the kW burden on the power grid across the city by optimally balancing the flxible loads subject to EV charging burden and price structure.

- Contrast to the traditional EV charging strategies, the proposed M1 and M2 model focuses on the both aspects of the price structure in the city, namely, the nodal variations and the temporal variations. This makes the proposed model more profit oriented compared to the traditional models, more grid requirement aware, and hence, a better alternative to accomplish the sustainable city goals.

Nomenclature

| Abbreviations | |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| CG | City Grid (System) |

| PG | Power Grid (System) |

| M. App | Mobile Application |

| RTP | Real-Time Pricing |

| PAUM | Profit-Aware Utilisation Model |

| PAUM-EV | Profit-Aware EV Utilisation Model |

| V2G | Vehicle-to-Grid |

| FDM | Flexible Demand Management |

References

- Reddy, K.; Kumar, M.; Mallick, T.; Sharon, H.; Lokeswaran, S. A review of Integration, Control, Communication and Metering (ICCM) of renewable energy based smart grid. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2014, 38, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouters, H.; Martinez, W. Bidirectional onboard chargers for electric vehicles: State-of-the-art and future trends. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics 2023, 39, 693–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astapov, V.; Shabbir, N.; Rosin, A.; Kütt, L.; Maask, V.; Tiismus, H. Review of technical solutions addressing voltage and operational challenges in a distribution grid with high penetration of intermittent RES. Energy Reports 2025, 14, 1738–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Yu, L.; Li, L. Smart transportation systems using learning method for urban mobility and management in modern cities. Sustainable Cities and Society 2024, 108, 105428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, P.; Rubino, G.; Rubino, L.; Capasso, C.; Veneri, O.; Motori, I. A case study of a DC-microgrid for the smart integration of renewable sources with the urban electric mobility. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Symposium on Power Electronics, Electrical Drives, Automation and Motion (SPEEDAM); IEEE, 2018; pp. 544–549. [Google Scholar]

- Calvillo, C.F.; Sánchez-Miralles, Á.; Villar, J. Synergies of electric urban transport systems and distributed energy resources in smart cities. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2017, 19, 2445–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastida-Molina, P.; Ribó-Pérez, D.; Gómez-Navarro, T.; Hurtado-Pérez, E. What is the problem? The obstacles to the electrification of urban mobility in Mediterranean cities. Case study of Valencia, Spain. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 166, 112649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, P.; Dutta, L.; Bordoloi, S.; Kalita, A.; Buragohain, P.; Bharali, S.; Azzopardi, B. Renewable energy integration with electric vehicle technology: A review of the existing smart charging approaches. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023, 183, 113518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, Z.; Ahmad, I.; Habibi, D.; Phung, Q.V. Smart Charging Strategy for Electric Vehicle Charging Stations. IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification 2018, 4, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Munkhammar, J.; Fachrizal, R.; Lovati, M.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y. Comparative studies of EV fleet smart charging approaches for demand response in solar-powered building communities. Sustainable cities and society 2022, 85, 104094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultanuddin, S.; Vibin, R.; Kumar, A.R.; Behera, N.R.; Pasha, M.J.; Baseer, K. Development of improved reinforcement learning smart charging strategy for electric vehicle fleet. Journal of Energy Storage 2023, 64, 106987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fachrizal, R.; Shepero, M.; Åberg, M.; Munkhammar, J. Optimal PV-EV sizing at solar powered workplace charging stations with smart charging schemes considering self-consumption and self-sufficiency balance. Applied Energy 2022, 307, 118139. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.q.; Yao, Y.p. Multi-objective capacity allocation optimization method of photovoltaic EV charging station considering V2G. Journal of Central South University 2021, 28, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Yan, S.; Pan, B.; Shi, Y. Two-stage optimization for efficient V2G coordination in distribution power system. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Communications, Control, and Computing Technologies for Smart Grids (SmartGridComm); IEEE, 2024; pp. 245–251. [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen, H.I.; Rashed, G.I.; Yang, B.; Yang, J. Optimal electric vehicle charging and discharging scheduling using metaheuristic algorithms: V2G approach for cost reduction and grid support. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 90, 111816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Peng, J.; Jiang, W.; Wang, J.; Du, L.; Zhang, J. Vehicle-To-Grid (V2G) Charging and Discharging Strategies of an Integrated Supply–Demand Mechanism and User Behavior: A Recurrent Proximal Policy Optimization Approach. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2024, 15, 514. [Google Scholar]

- Abiassaf, G.A.; Arkadan, A.A. Impact of EV charging, charging speed, and strategy on the distribution grid: a case study. IEEE Journal of Emerging and Selected Topics in Industrial Electronics 2024, 5, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.; Thakur, J.; Bhagavathy, S.M.; Topel, M. Impact of public and residential smart EV charging on distribution power grid equipped with storage. Sustainable Cities and Society 2024, 104, 105272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Habib, S.; Ali, M.; Shafiq, A.; ur Rehman, A.; Ahmed, E.M.; Khurshaid, T.; Kamel, S. The impact of V2G charging/discharging strategy on the microgrid environment considering stochastic methods. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Ilka, R.; He, J.; Liao, Y.; Cramer, A.M.; Mccann, J.; Delay, S.; Coley, S.; Geraghty, M.; Dahal, S. Impact of electric vehicle charging on power distribution systems: A case study of the grid in western kentucky. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 49002–49023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algafri, M.; Baroudi, U. Optimal charging/discharging management strategy for electric vehicles. Applied Energy 2024, 364, 123187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, C.; Victor, K.; Zurmühlen, S.; Sauer, D.U. Electric vehicle route planning using real-world charging infrastructure in Germany. ETransportation 2021, 10, 100143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Do Chung, B. Energy consumption optimization for the electric vehicle routing problem with state-of-charge-dependent discharging rates. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 385, 135703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahkamrani, A.; Askarian-abyaneh, H.; Nafisi, H.; Marzband, M. A framework for day-ahead optimal charging scheduling of electric vehicles providing route mapping: Kowloon case study. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 307, 127297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, E.W. A note on two problems in connexion with graphs. Numerische mathematik 1959, 1, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, S.; Trivedi, A.; Srinivasan, D. A Resource-Constrained V2V Optimisation Model for Commercial EV Fleet Operation. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference Europe (ISGT-Europe), October 2025. [Accepted].

- Baran, M.; Wu, F. Network reconfiguration in distribution systems for loss reduction and load balancing. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 1989, 4, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMM Lab. Systems Mappings and EVs energy and time information, 2025. Accessed: 2025-11-03.

- Energy Market Company Pte Ltd. NEMS Prices. https://www.nems.emcsg.com/nems-prices, 2024. Accessed: 2025-10-17.

| 1 |

| Bus no.: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No FDM: | 0 | 9.6 | 8.64 | 11.52 | 5.76 | 5.76 | 19.2 | 19.2 | 5.76 | 5.76 | 4.32 | 5.76 | 5.76 | 11.52 |

| FDM: | 0 | 9.3566 | 5.8518 | 9.1929 | 4.2996 | 4.4524 | 17.86 | 18.281 | 4.2345 | 4.2277 | 1.8671 | 3.3755 | 3.827 | 10.384 |

| Bus no.: | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| No FDM: | 5.76 | 5.76 | 5.76 | 8.64 | 8.64 | 8.64 | 8.64 | 8.64 | 8.64 | 40.32 | 40.32 | 5.76 | 5.76 | 5.76 |

| FDM: | 3.3253 | 4.1615 | 4.7078 | 5.823 | 6.0122 | 6.9895 | 6.7726 | 6.8789 | 8.0168 | 39.416 | 38.907 | 5.0685 | 3.2271 | 5.1757 |

| Bus no.: | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | |||||||||

| No FDM: | 11.52 | 19.2 | 14.4 | 20.16 | 5.76 | |||||||||

| FDM: | 10.842 | 18.688 | 14.4 | 20.16 | 5.76 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).