Submitted:

04 December 2025

Posted:

08 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Alloy Preparation

2.2. Microstructural Characterization

2.3. Soft Magnetic Properties

2.4. Mechanical Properties

3. Results and Discussion

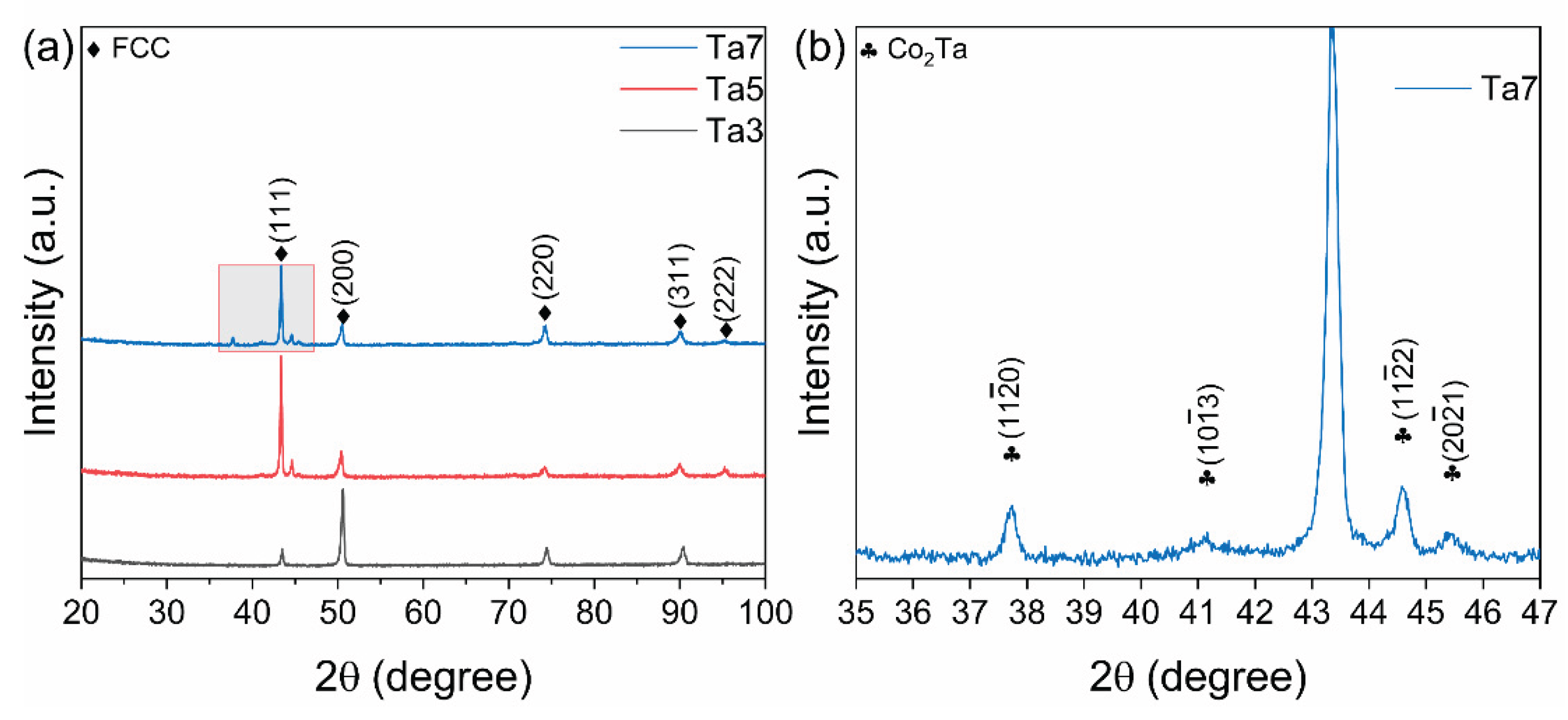

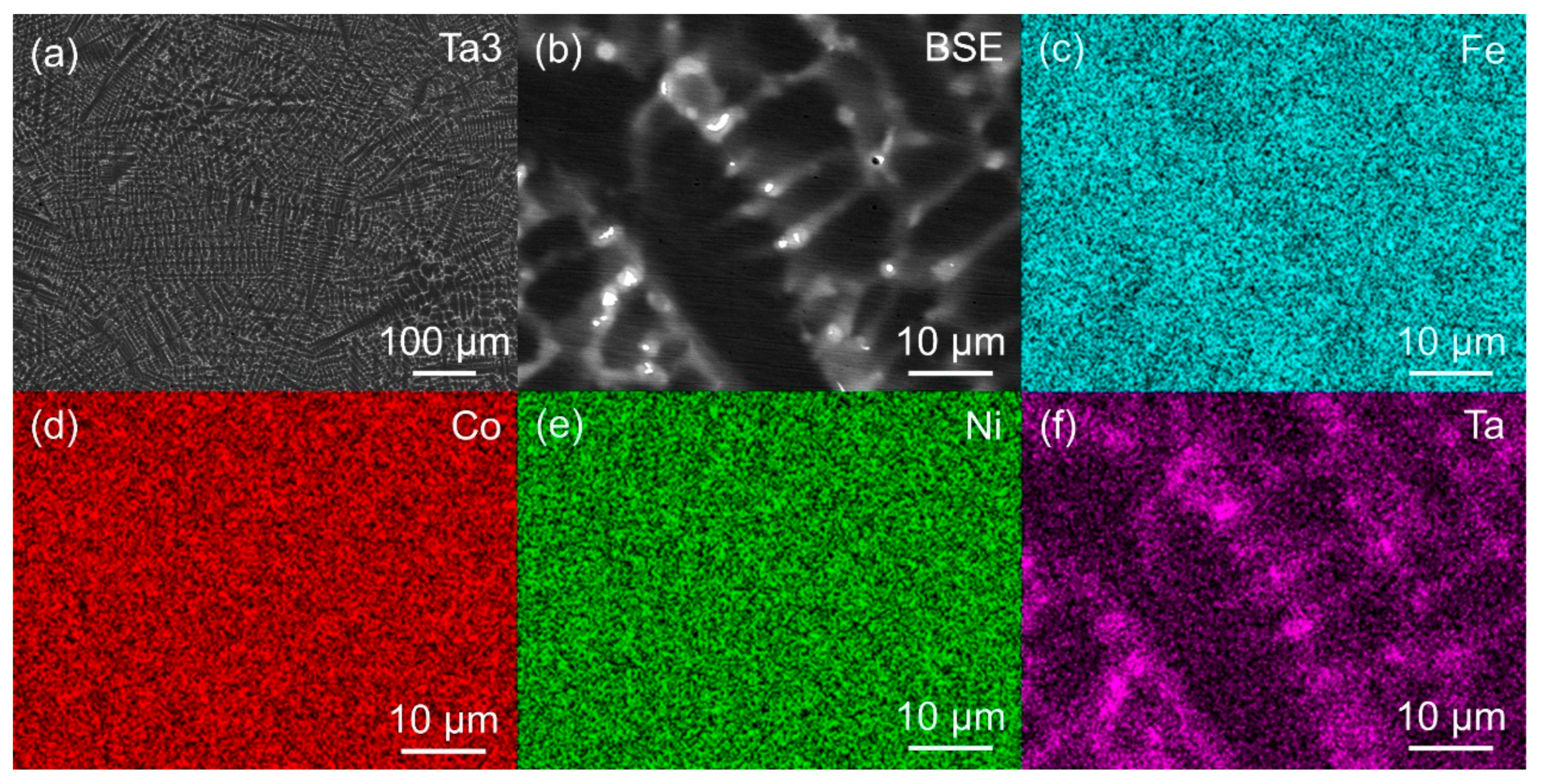

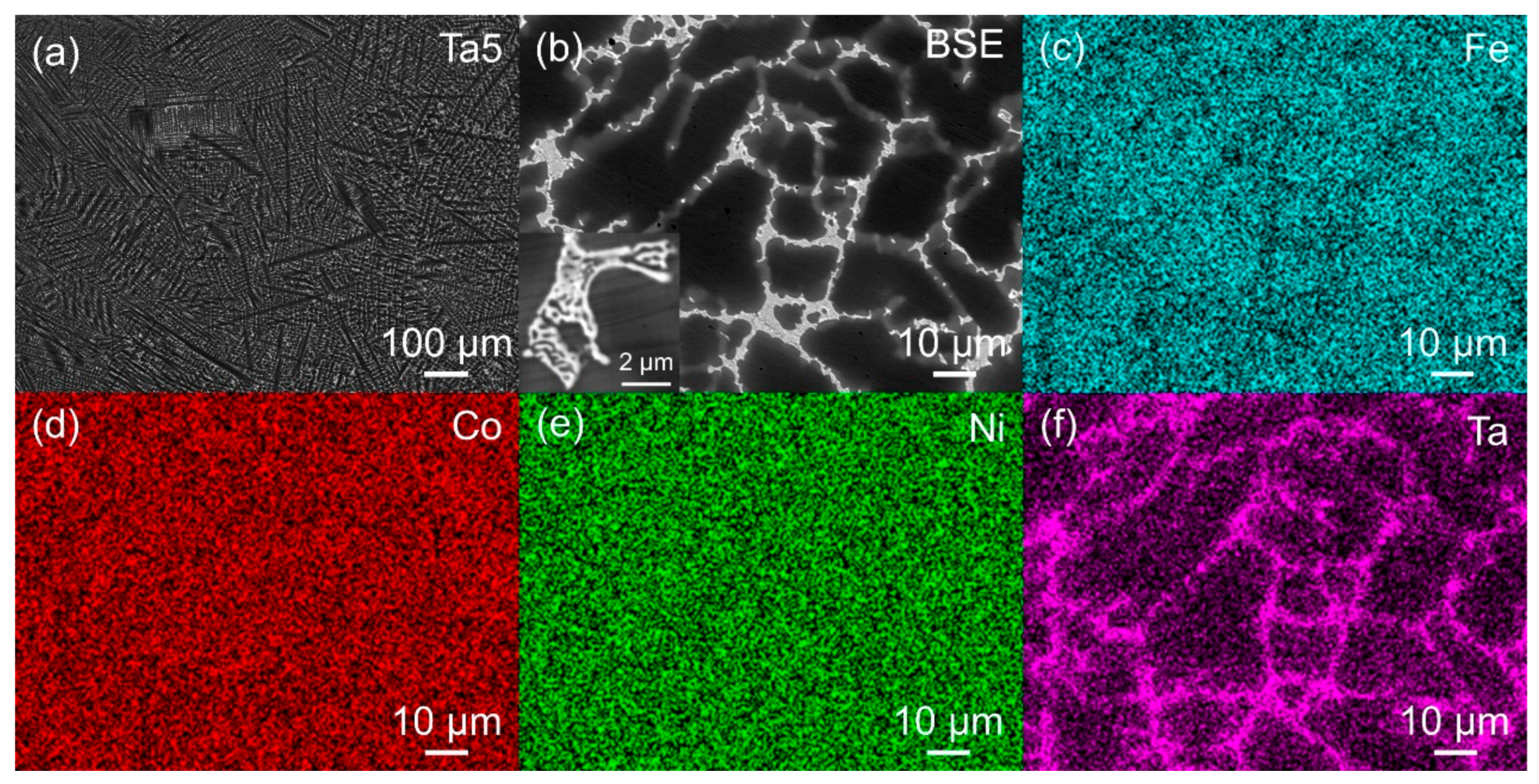

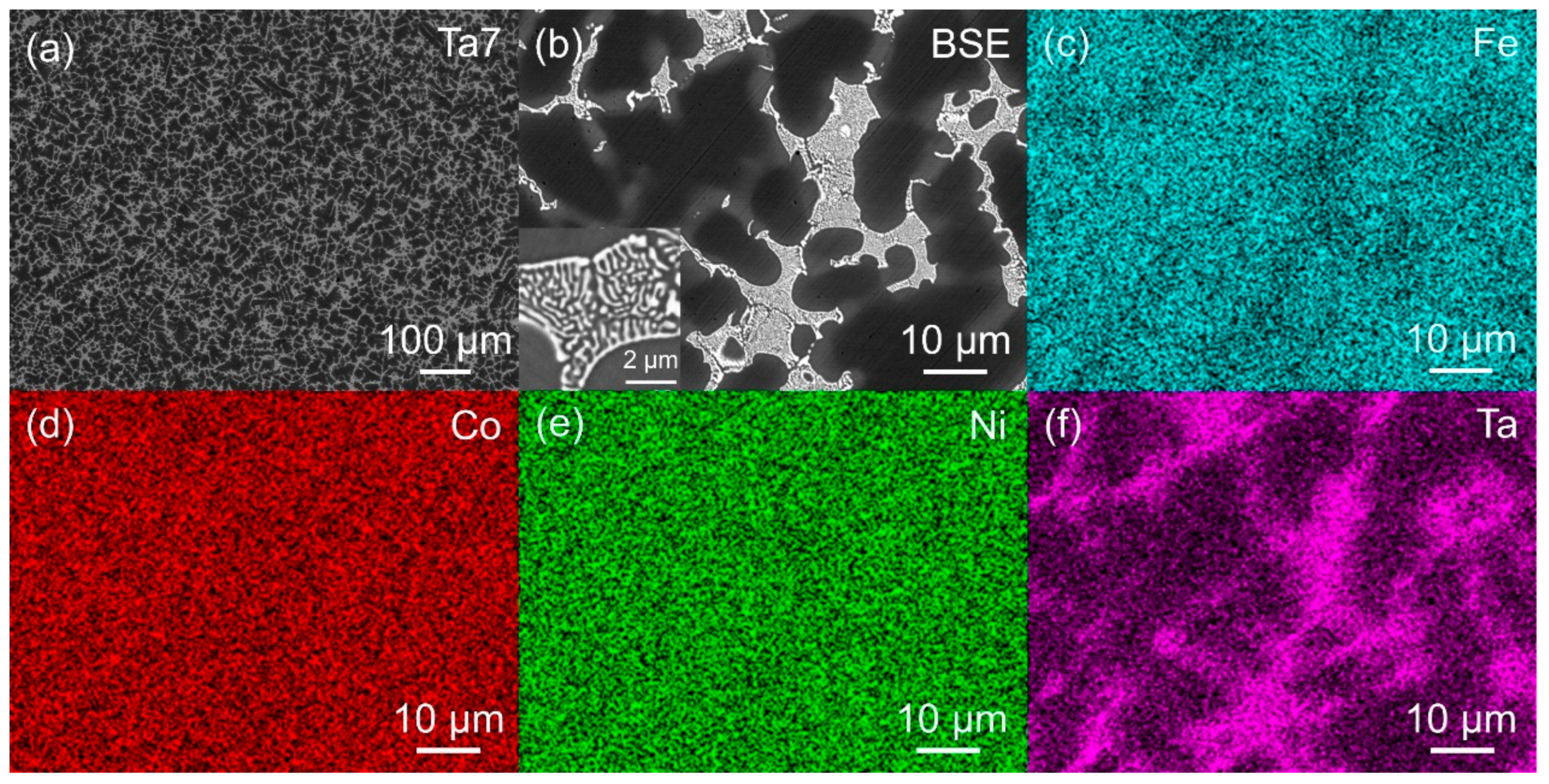

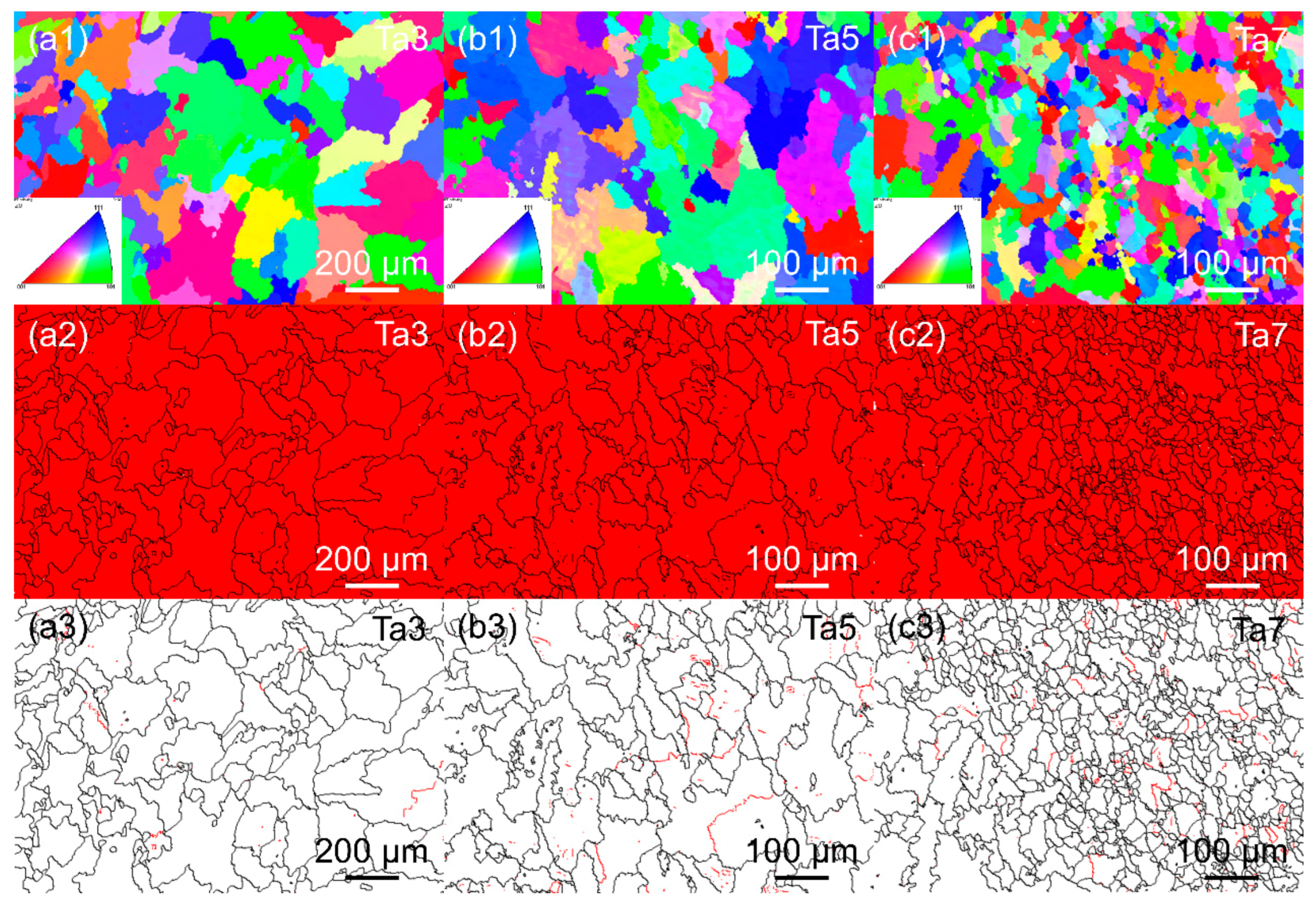

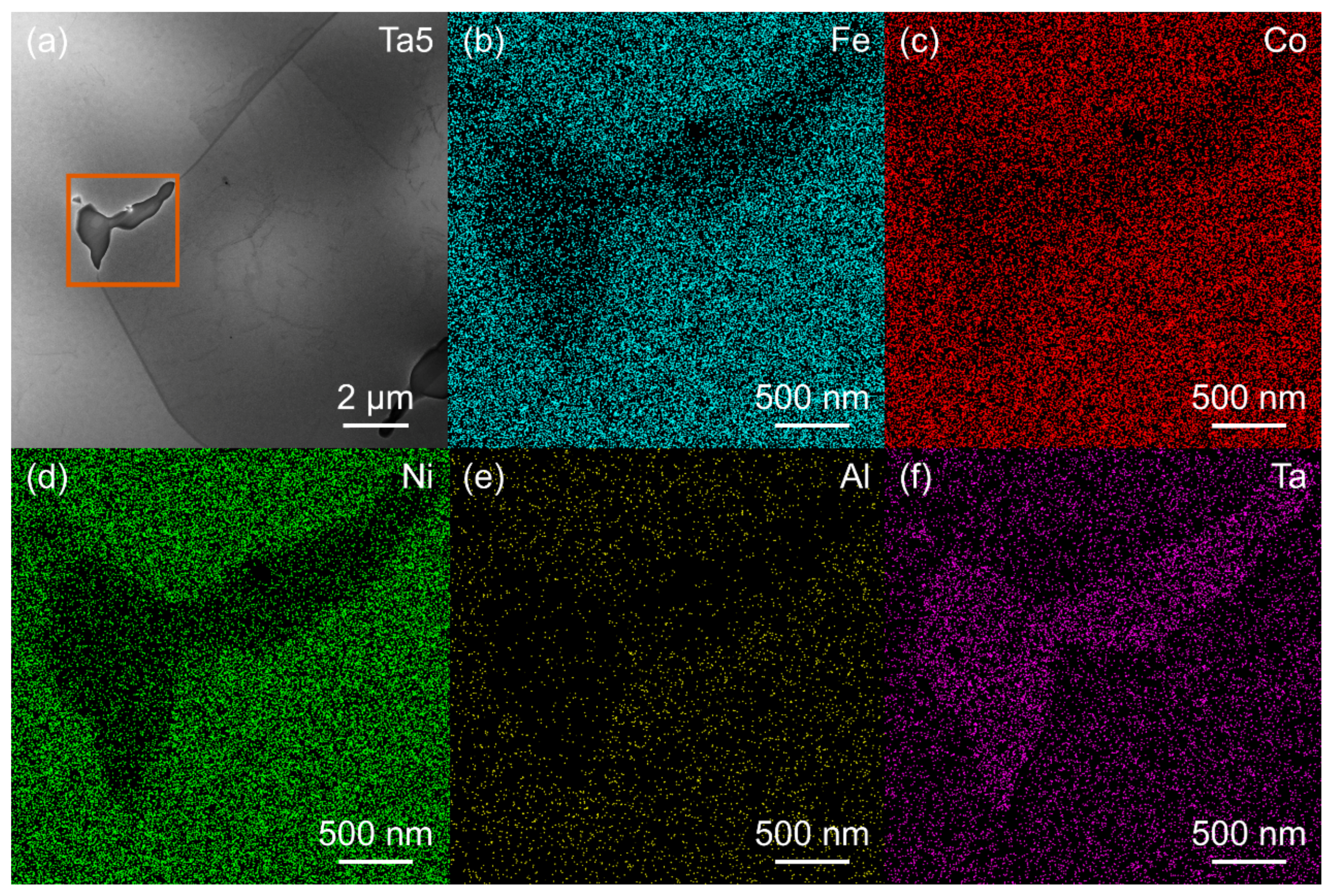

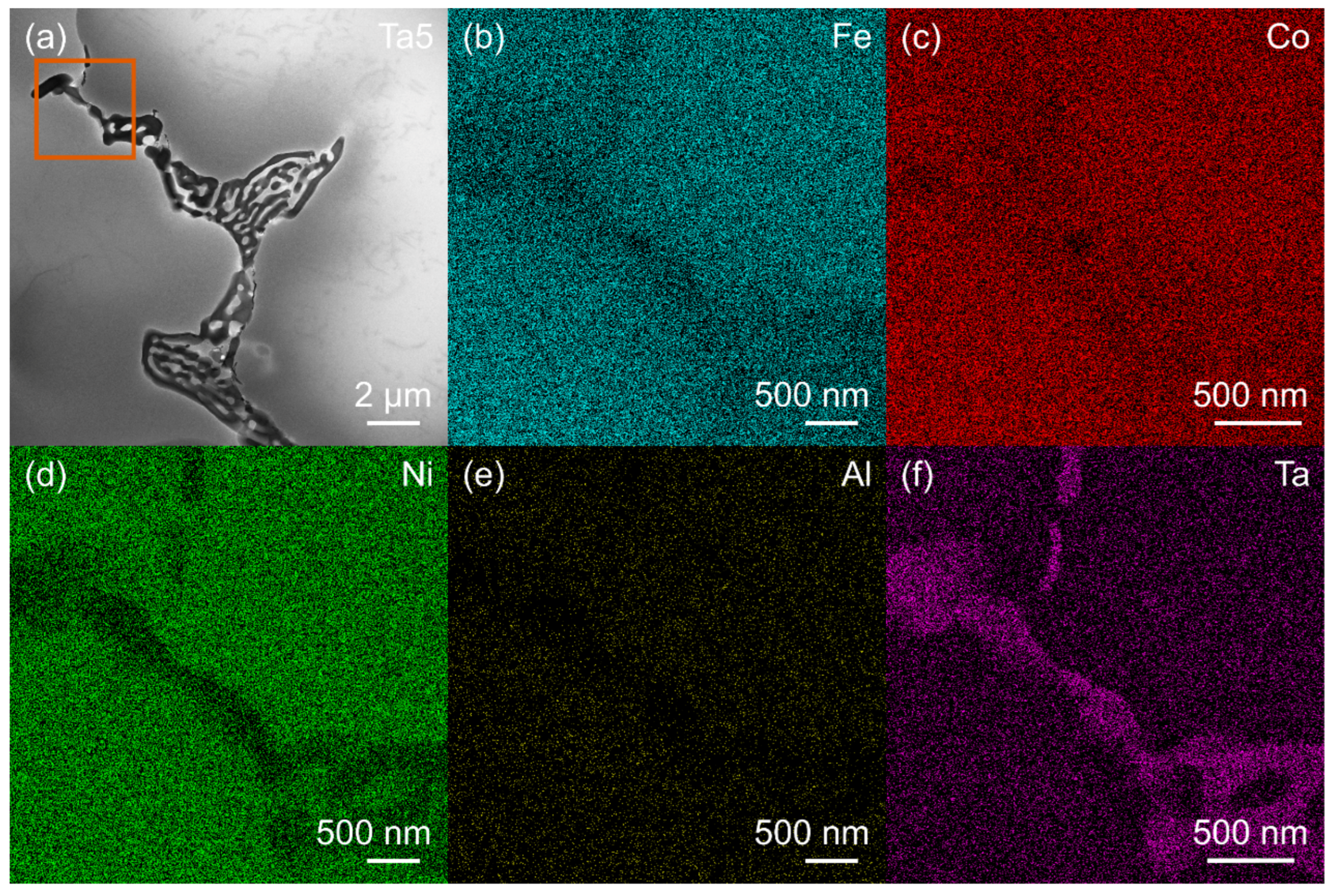

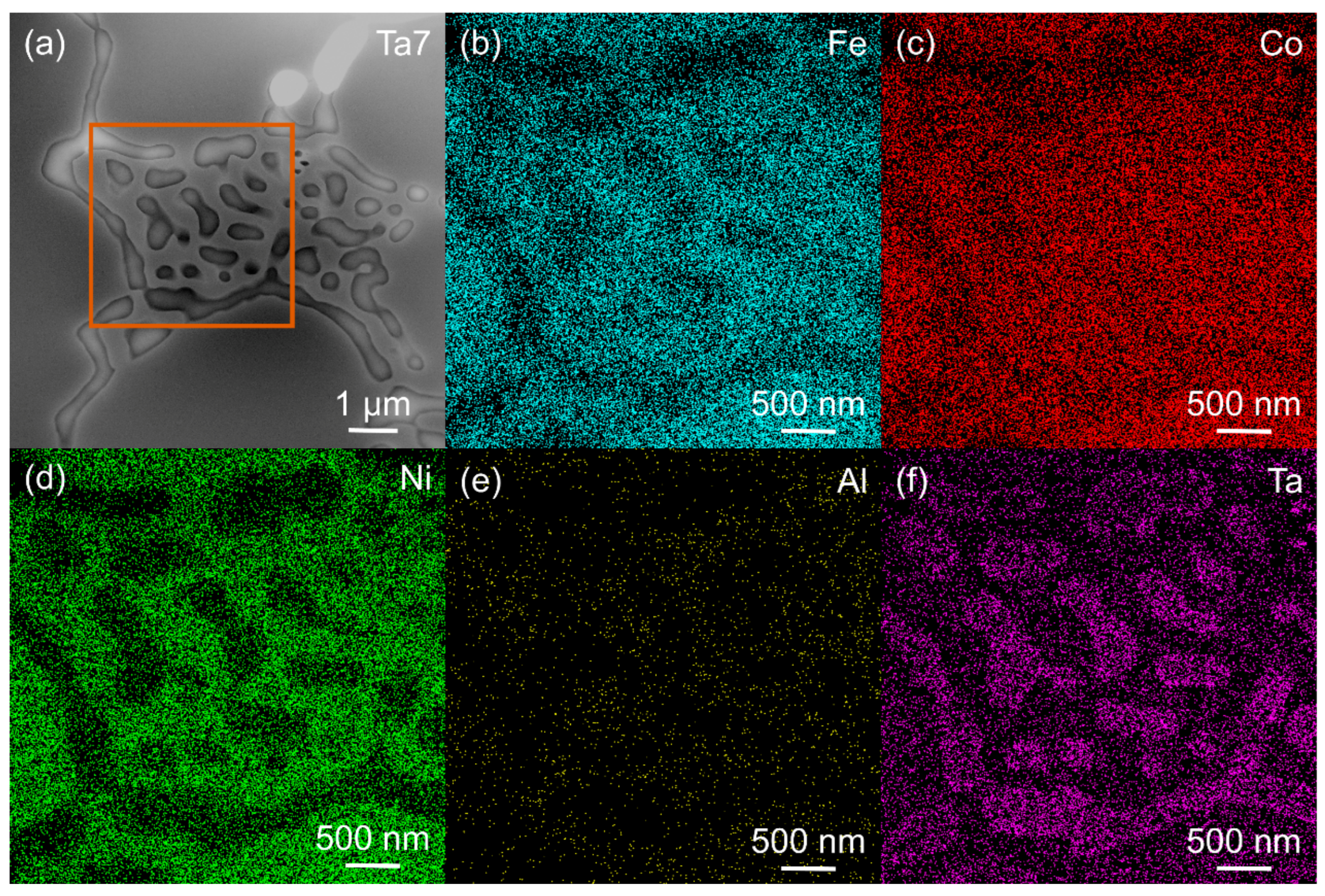

3.1. Microstructure of MPEAs

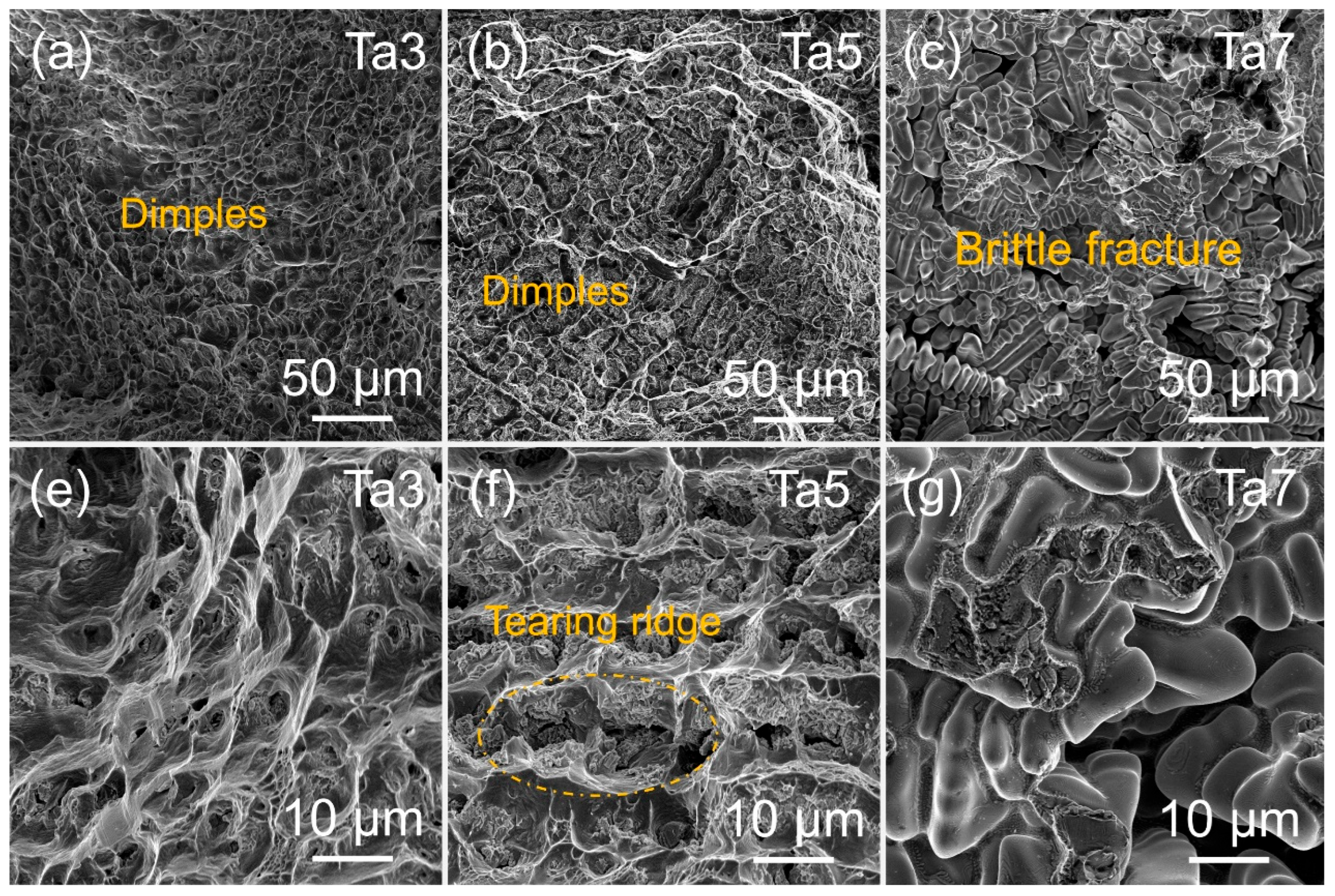

3.2. Magnetic and Mechanical Properties

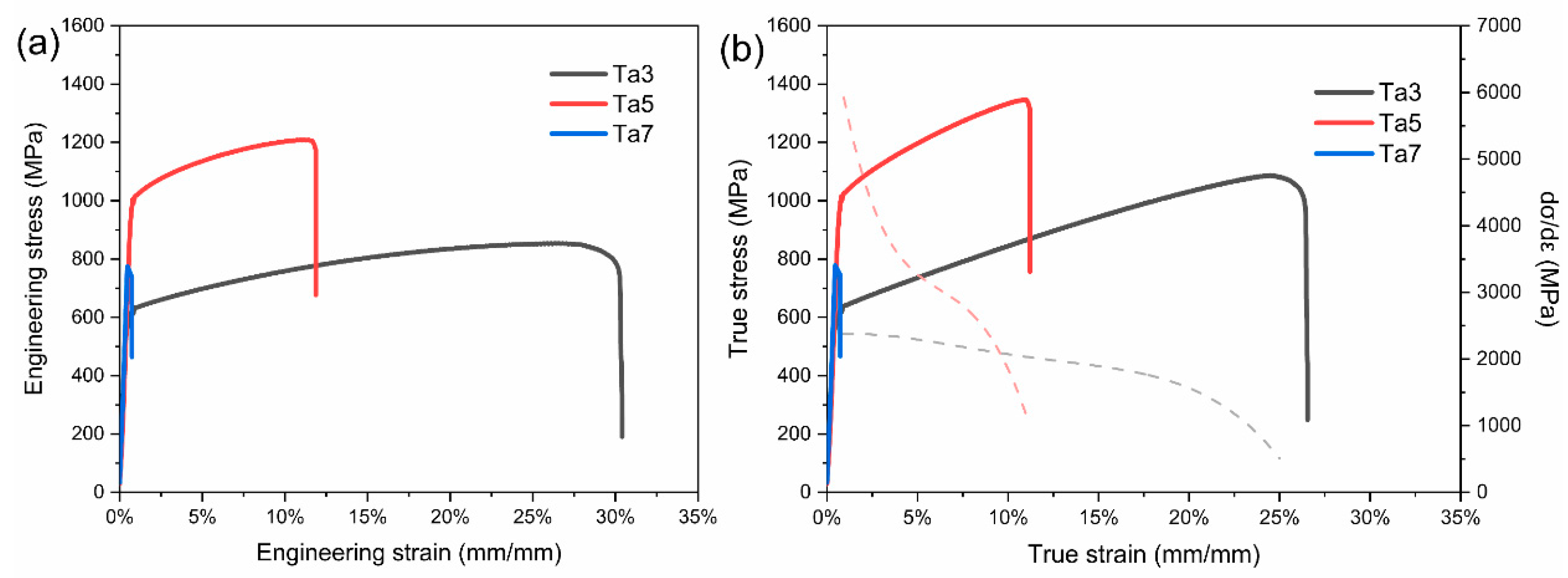

| Alloy | σs (MPa) | σUTS (MPa) | TE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ta3 | 595 ± 26 | 849 ± 38 | 29.3 ± 3.8 |

| Ta5 | 993 ± 12 | 1210 ± 83 | 10.3 ± 3.1 |

| Ta7 | -- | 799 ± 153 | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krings, A.; Boglietti, A.; Cavagnino, A. Soft magnetic material status and trends in electric machines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 2405–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, M.A.; Loh, J.Y.; Joshi, S.C. Magnetic loading of soft magnetic material selection implications for embedded machines in more electric engines. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2016, 52, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutfleisch, O.; Willard, M.A.; Brück, E. Magnetic Materials and Devices for the 21st Century: Stronger, Lighter, and More Energy Efficient. Adv. Mater. 2010, 23, 821–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Hou, D.W.; Dai, S.F. Achieving superior mechanical and magnetic properties in non-oriented electrical steel with high coherent nanoprecipitation. Mater. Res. Lett. 2025, 13, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Liang, Y.; Han, C. High-strength low-iron-loss electrical steel accomplished by Cu-rich nanoprecipitates. Mater. Lett. 2021, 296, 129917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, A.J. Energy efficient electrical steels: Magnetic performance prediction and optimization. Scr. Mater. 2012, 67, 560–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgamli, E.; Anayi, F. Advancements in Electrical Steels: A Comprehensive Review of Microstructure, Loss Analysis, Magnetic Properties, Alloying Elements, and the Influence of Coatings. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Hou, D.W.; Dai, S.F. Achieving superior mechanical and magnetic properties in non-oriented electrical steel with high coherent nanoprecipitation. Mater. Res. Lett. 2025, 13, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinca, T.F.; Sule, A.I.; Hirian, R. Al-Permalloy (Ni71.25Fe23.75Al5) obtained by mechanical alloying. The influence of the processing parameters on structural, microstructural, thermal, and magnetic characteristics. Adv. Powder Technol. 2022, 33, 103642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waeckerlé, T.; Demier, A.; Godard, F. Evolution and recent developments of 80%Ni permalloys. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2020, 505, 166635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Zhao, X.; Sun, X. Microstructure evolution and strengthening mechanism of FeCo-1.5V0.5Nb0.4W soft magnetic alloy rolled strip with high yield strength and low coercivity. Acta. Mater. 2024, 268, 119793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.D.; Xin, S.W.; Sun, B.R. Low power loss in Fe65.5Cr4Mo4Ga4P12B5.5C5 bulk metallic glasses. J. Alloy. Compd. 2016, 658, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, I.; Nitomi, H.; Imanishi, K. Application of High-Strength Nonoriented Electrical Steel to Interior Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2013, 49, 2997–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, K.; Ishikawa, K.; Ohguchi, H. Magnetic Property Investigation of High-Strength Electrical Steel Sheet Applied to Interior Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors Considering Multiaxial Stress Caused by Centrifugal Force. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2023, 59, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H. New design of electric vehicle motor based on high-strength soft magnetic materials. Compel 2022, 42, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Zhuang, Z.M.; Ding, F. Plasticity and brittleness of Fe-based amorphous alloy strips assessed via a single abrasive impact method. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 35, 105637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.X.; Li, W.; Shen, F.H. Plastic deformation behavior of a novel Fe-based metallic glass under different mechanical testing techniques. J. Non-cryst Solids 2018, 499, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Hu, Y.J.; Taylor, A. A lightweight single-phase AlTiVCr compositionally complex alloy. Acta. Mater. 2017, 123, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Jha, S.R.; Gurao, N.P. An odyssey from high entropy alloys to complex concentrated alloys. New Horizons Metall. Mater. Manuf. 2022, 159–180. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, J.W. Physical Metallurgy of High-Entropy Alloys. J. Met. 2015, 67, 2254–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, B.; Chang, I.T.H.; Knight, P. Microstructural development in equiatomic multicomponent alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng.A 2004, 375-377 213-218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.W. Alloy Design Strategies and Future Trends in High-Entropy Alloys. J. Met. 2013, 65, 1759–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.L.; Tsai, C.W.; Yeh, A.C. Clarifying the four core effects of high-entropy materials. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2024, 8, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Xie, D.; Li, D. Mechanical behavior of high-entropy alloys. Prog. Mater Sci. 2021, 118, 100777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.; Gupta, A.K.; Mishra, R.K. A Comprehensive Review: Recent Progress on Magnetic High Entropy Alloys and Oxides. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2022, 554, 169142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zuo, T.T.; Tang, Z. Microstructures and properties of high-entropy alloys. Prog. Mater Sci. 2014, 61, 1–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Y.; Qiu, Y.; Birbilis, N. On the corrosion of a nano-oxide dispersion strengthened CoCrNi medium entropy alloy prepared by laser powder bed fusion. Corros. Sci. 2025, 257, 113341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Y.; Qiu, Y.; Shi, X. Nano-dispersion strengthened and twinning-mediated CoCrNi medium entropy alloy with excellent strength and ductility prepared by laser powder bed fusion. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1005, 176103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Ren, Y.; Zeng, Y. Recent progress in high-entropy alloys: A focused review of preparation processes and properties. J. Mater Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 2689–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Zhang, C.; Gao, M.C. High-throughput design of high-performance lightweight high-entropy alloys. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Thomas, S.; Gibson, M.A. Microstructure and corrosion properties of the low-density single-phase compositionally complex alloy AlTiVCr. Corros. Sci. 2018, 133, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Li, Y.; Qi, Y. Review on Preparation Technology and Properties of Refractory High Entropy Alloys. Materials 2022, 15, 2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senkov, O.N.; Wilks, G.B.; Scott, J.M. Mechanical properties of Nb25Mo25Ta25W25 and V20Nb20Mo20Ta20W20 refractory high entropy alloys. Intermetallics 2011, 19, 698–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senkov, O.N.; Wilks, G.B.; Miracle, D.B. Refractory high-entropy alloys. Intermetallics 2010, 18, 1758–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Atwani, O.; Li, N.; Li, M. Outstanding radiation resistance of tungsten-based high-entropy alloys. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanzhulov, B.; Ivanov, I.; Uglov, V. Composition and Structure of NiCoFeCr and NiCoFeCrMn High-Entropy Alloys Irradiated by Helium Ions. Materials 2023, 16, 3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savvotin, I.; Berdonosova, E.; Korol, A. Evaluation of hydrogen storage performance of Ti0.25Zr0.25V0.15Nb0.15Ta0.2 high-entropy alloy using calorimetric technique. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1005, 176022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, S.; Bhatt, D.; Satheesh, D. High entropy alloys: A comprehensive review of synthesis, properties, and characterization for electrochemical energy conversion and storage applications. J. Mater Chem A 2025, 13, 37663–37699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.B.; Fu, Z.Y.; Zhang, J.Y. Annealing on the structure and properties evolution of the CoCrFeNiCuAl high-entropy alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 502, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, M.S.; Mauger, L.; Muñoz, J.A. Magnetic and vibrational properties of high-entropy alloys. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 109, 07E307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Tang, Y.; Tan, Y. Correlation between microstructure and soft magnetic parameters of Fe-Co-Ni-Al medium-entropy alloys with FCC phase and BCC phase. Intermetallics 2020, 126, 106898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; He, T.; Andreoli, A.F. The origin of good mechanical and soft magnetic properties in a CoFeNi-based high-entropy alloy with hierarchical structure. Mater. Charact. 2024, 215, 114237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Tang, Y.; Tan, Y. Effect of grain boundary character distribution on soft magnetic property of face-centered cubic FeCoNiAl0.2 medium-entropy alloy. Mater. Charact. 2020, 159, 110028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Z.; Ponge, D.; Körmann, F. Invar effects in FeNiCo medium entropy alloys: From an Invar treasure map to alloy design. Intermetallics 2019, 111, 106520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zuo, T.; Cheng, Y. High-entropy Alloys with High Saturation Magnetization, Electrical Resistivity and Malleability. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T.-T.; Ren, S.-B.; Liaw, P.K. Processing effects on the magnetic and mechanical properties of FeCoNiAl0.2Si0.2 high entropy alloy. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2013, 20, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.X.; Sun, B.R.; Liu, G.Y. FeCoNiAlSi high entropy alloys with exceptional fundamental and application-oriented magnetism. Intermetallics 2020, 122, 106801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Rao, Z.; Souza Filho, I.R. Ultrastrong and Ductile Soft Magnetic High--Entropy Alloys via Coherent Ordered Nanoprecipitates. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2102139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, L.; Maccari, F.; Souza Filho, I.R. A mechanically strong and ductile soft magnet with extremely low coercivity. Nature 2022, 608, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.L.; Peter, N.J.; Maccari, F. Two-gigapascal-strong ductile soft magnets. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, P.; Huang, L.; Yang, Q. Mechanical and magnetic properties of nonequiatomic Fe33Co28Ni28Ta5Al6 high entropy alloy by laser melting deposition. Vacuum 2024, 220, 112854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Dong, Y.; Jia, X. Novel CoFeAlMn high-entropy alloys with excellent soft magnetic properties and high thermal stability. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 153, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T.; Gao, M.C.; Ouyang, L. Tailoring magnetic behavior of CoFeMnNiX (X = Al, Cr, Ga, and Sn) high entropy alloys by metal doping. Acta. Mater. 2017, 130, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wang, A.; Liu, C.T. Composition dependence of structure, physical and mechanical properties of FeCoNi(MnAl)x high entropy alloys. Intermetallics 2017, 87, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Dong, Y.; Ma, Y. Effects of structural transformation on magnetic properties of AlCoFeCr high-entropy soft magnetic powder cores by adjusting Co/Fe ratio. Mater. Des. 2023, 225, 111537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, X. A Novel Soft--Magnetic B2--Based Multiprincipal--Element Alloy with a Uniform Distribution of Coherent Body--Centered--Cubic Nanoprecipitates. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2006723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yuan, J.; Wang, Q. Developing novel high-temperature soft-magnetic B2-based multi-principal-element alloys with coherent body-centered-cubic nanoprecipitates. Acta. Mater. 2024, 266, 119686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.L.; Lin, P.H. Influences of Ta content and mechanical alloying on synthesis and characteristics of CoCrNiFeTax high entropy alloys. Intermetallics 2024, 172, 108362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Lu, Y.; Cao, Z. Effects of Ta Addition on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of CoCu0.5FeNi High-Entropy Alloy. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2019, 28, 7642–7648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragsdorf, R.D.; Foreing, W.D. The intermetallic phases in the cobalt-tantalum system. Acta. Crystallogr. 1962, 15, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Großwendt, F.; Rajkowski, M. Formation of an ordered phase in hcp precipitates during aging of bcc HfNbTaTiZr high-entropy alloy. Scr. Mater. 2025, 262, 116634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, C.; Laplanche, G. Effect of grain size on critical twinning stress and work hardening behavior in the equiatomic CrMnFeCoNi high-entropy alloy. Int. J. Plast. 2023, 166, 103651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Cong, H.; Li, H. Nanoscale core-shell particles enhance the mechanical property of additively manufactured high-entropy alloys. Mater. Charact. 2025, 230, 115791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuh, B.; Mendez-Martin, F.; Völker, B. Mechanical properties, microstructure and thermal stability of a nanocrystalline CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy after severe plastic deformation. Acta. Mater. 2015, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.M.; Zhou, B.C.; Qiu, S. Achieving ultrahigh strength and ductility in high-entropy alloys via dual precipitation. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 166, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Alloy | Fe (wt. %) | Co (wt. %) | Ni (wt. %) | Ta (wt. %) | Al (wt. %) | ρ (g/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Fe7Co6Ni6)90Ta3Al7 | 31.25 | 28.26 | 28.15 | 9.16 | 3.19 | 8.29 |

| (Fe7Co6Ni6)88Ta5Al7 | 29.33 | 26.53 | 26.42 | 14.66 | 3.06 | 8.54 |

| (Fe7Co6Ni6)86Ta7Al7 | 27.56 | 24.93 | 24.83 | 19.73 | 2.94 | 8.78 |

| Alloy | Ms (emu/g) | Hc (Oe) | Hc (A/m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ta3 | 108.22 | 3.49 | 277.73 |

| Ta5 | 92.88 | 5.61 | 446.43 |

| Ta7 | 76.28 | 11.05 | 879.33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).