1. Introduction

Bridges are central components of highway and local transportation networks, providing safe passage for people and freight across rivers, wetlands, rail lines, and low-lying coastal areas [

1,

2]. The United States has about 617,000 bridges, and the 2021 ASCE Infrastructure Report Card noted that 42 percent of them are at least 50 years old, while about 7.5 percent are in poor or structurally deficient condition, which confirms that age related deterioration is a system level issue rather than a few isolated cases [

3,

4].

Among bridge components, the deck most often shows distress first, because it is directly exposed to traffic abrasion, deicing salts, freezing thaw cycles, and wetting and drying, especially in cold or marine influenced regions [

5,

6,

7]. A primary driver of this deterioration is chloride-based deicing salts, essential for winter road safety, which significantly accelerates the deterioration of bridge decks through concrete degradation and reinforcement corrosion, leading to substantial economic costs from traffic disruptions and reconstruction. While direct data on salt application is scarce, climatic conditions can serve as exposure proxies [

8,

9]. This creates a critical challenge for agencies like the Delaware Department of Transportation (DelDOT), whose interstate bridge decks from the 1980s-90s are nearing the end of their typical 30-year lifespan. To optimize maintenance funding and extend service life, state agencies have developed bridge deterioration models to predict structural decline and guide proactive interventions [

10]. As bridges age, repeated traffic loading and exposure to chloride laden moisture increase the need for maintenance, repair, and replacement.

With the increased use of deicing salts for vehicular safety and the threat of increased saltwater encroachment, there is a critical need to accurately predict concrete bridge deck deterioration due to chloride exposure for effective maintenance planning. For decades, research has focused on steel reinforcement as the critical component when it comes to chloride-induced damage. For example, Demich [

11] investigated bridge deck deterioration caused by de-icing chemicals and observed that reinforcement in concrete bridge decks deteriorates significantly due to chloride ingress from de-icing salts, leading to corrosion and reduced structural integrity. Jia (2022) [

12] analyzed the effect of reducing the cross-sectional area of reinforcing bars due to corrosion on the flexural and shear strength of typical concrete bridge decks. The authors employed ground-penetrating radars to detect corrosion probability at the top reinforcement layer; they subsequently evaluated the structural performance under both flexural and shear failure modes. The study concluded that typical levels of reinforcement corrosion were not sufficient to cause bridge deck collapse under design loading. Hájková et al. (2018) [

13] present a chemo-mechanical model that links chloride ingress, corrosion initiation, cover cracking and spalling, and the resulting loss of reinforcement area in concrete structures. Applied to two existing chloride-exposed bridges, the model shows that even very small cracks can greatly shorten the predicted time to corrosion initiation, while the analyzed members still retain more than half of their original load-carrying capacity after long-term exposure. Qasim et al. [

14] investigated the effect of salinity on the mechanical properties of concrete, including compressive, splitting tensile and flexural strengths. Concrete specimens cured in NaCl solutions with salt contents between 0% and 5% by weight of water showed an overall reduction in 28-day strength with increasing salinity; for example, the 28-day cylinder compressive strength decreased from 30.0 MPa at 0% salt to 26.1 MPa at 5% salt. The authors attributed these reductions to the damaging action of dissolved salts and associated sulfate attack on the hardened cement paste. Penttala [

15] investigated concrete exposed to freeze–thaw in water and in a 3% NaCl solution and found that the water–cement ratio and air content largely control both surface scaling and internal damage. Concretes with lower water–cement ratios and sufficient air entrainment showed better resistance, while saline freeze–thaw at low water–binder ratios led to more internal damage and required higher air contents to limit it

Despite significant research on reinforcement bar corrosion-induced deterioration, many transportation agencies have increasingly adopted corrosion-resistant strategies, such as epoxy-coated reinforcement, reducing its role as the primary cause of deterioration [

16]. While this effectively delays steel deterioration [

17], it shifts the primary mode of failure and the concrete itself then becomes the critical component governing deck service life. This shift creates a fundamental gap in existing predictive models, since the traditional models [

17,

18] were developed and calibrated largely consider corrosion-based deterioration, as uncoated reinforcement will lead to spalling and cracking of concrete decks. They are therefore inadequate for predicting the long-term degradation of the concrete material, which is now the controlling factor in the service life of modern bridge decks. This shift means that future predictive models should place more weight on long term concrete material degradation and should define deterioration envelopes that include newer preservation practices and materials

While bridge deterioration models are important for optimizing maintenance planning and for allocating limited funds [

18], models that rely only on historical inspection data have a built-in limitation. In Delaware, for example, DelDOT’s model uses the National Bridge Inventory ratings to learn past deterioration patterns and to project future condition, which works well when the bridge stock and materials stay similar over time. Most of these datasets, however, reflect decks with uncoated reinforcement, so the forecast is driven mainly by corrosion induced spalling and cracking [

17]. Once epoxy coated reinforcement and other anticorrosion techniques became common in Delaware bridge construction in the 1970s, the steel component of deterioration was delayed [

19]. In that case, the concrete itself can become the governing limit on deck service life, not the reinforcement. This shift means that future predictive models should place more weight on long term concrete material degradation and should define deterioration envelopes that include newer preservation practices and materials.

The objective of this research is to evaluate the impact of salinity exposure on cementitious materials in terms of accelerated and projected long term structural performance and durability, and to develop deterioration envelopes for predicting concrete bridge deck deterioration due to chloride exposure. Accelerated laboratory tests in an environmental chamber at specified chloride concentrations and temperatures are combined with deterioration trends and existing condition state data to generate long term curves for chloride induced damage. Bridge deck cores taken from structures older than 50 years are used as a baseline for comparison and for validating the experimentally derived trends. The novelty of this work lies in the combined use of accelerated environmental chamber testing, multi parameter material characterization, and in-situ bridge deck cores to derive deterioration envelopes that are calibrated against field performance in high salinity conditions. The study examines the influence of cyclic wet/dry exposure and freeze/thaw cycles on the mechanical properties and durability of concrete, with a focus on the role of salt concentration in promoting microstructural degradation and loss of strength. Material degradation is quantified by measuring compressive strength, modulus of elasticity, Poisson’s ratio, and chloride penetration. The resulting predictive deterioration envelopes provide a clearer view of deterioration progression in concrete infrastructure and the resilience of concrete in harsh exposure. In the long term, the findings are intended to inform the degradation models used by the Delaware Department of Transportation (DelDOT), with particular focus on the performance of concrete bridge decks that utilize corrosion resistant steel reinforcement in high salinity environments, and to support preservation strategies and long-term durability assessments of critical transportation infrastructure.

5. Analysis and Discussion

The analysis is organized into four primary sections, which help inform the deterioration envelope: 1) Environmental Condition Trends, 2) Experimental Trends, 3) Predictive Models, and the 4) Durability Index. Each section builds upon the results to progressively connect short-term laboratory findings with long-term deterioration behavior.

5.1. Environmental Condition Trends

This section examines the environmental factors causing degradation of concrete bridge decks, such as chloride exposure, freeze-thaw cycling, and wet-dry exposure. These exposures were simulated in laboratory testing to model real exposure conditions prevalent in Delaware and similar climates. The resulting information illuminates the effect of environmental stressors on the type and rate of degradation, forming the basis for evaluating long-term bridge deck performance.

Freeze-Thaw Predictions

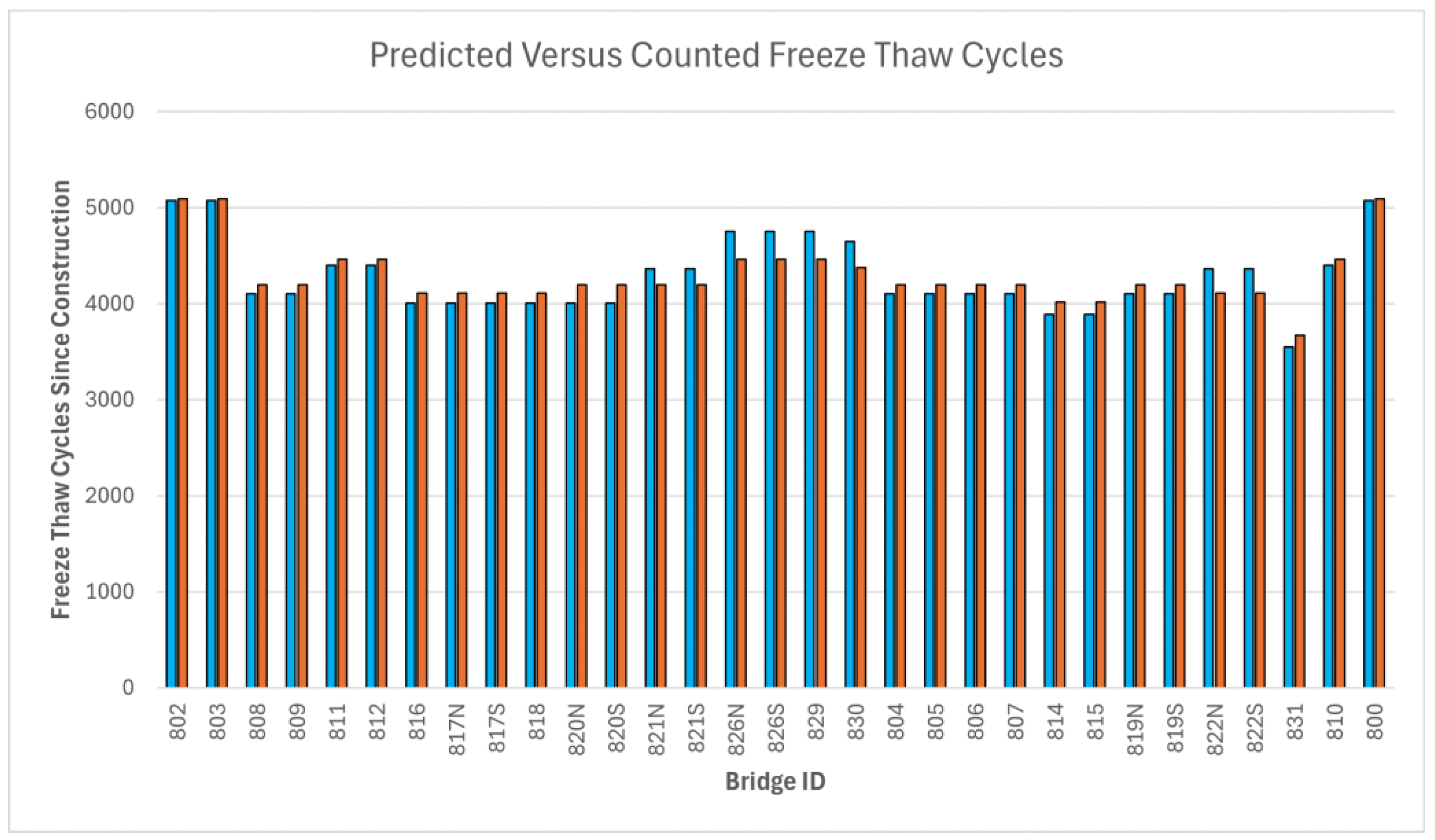

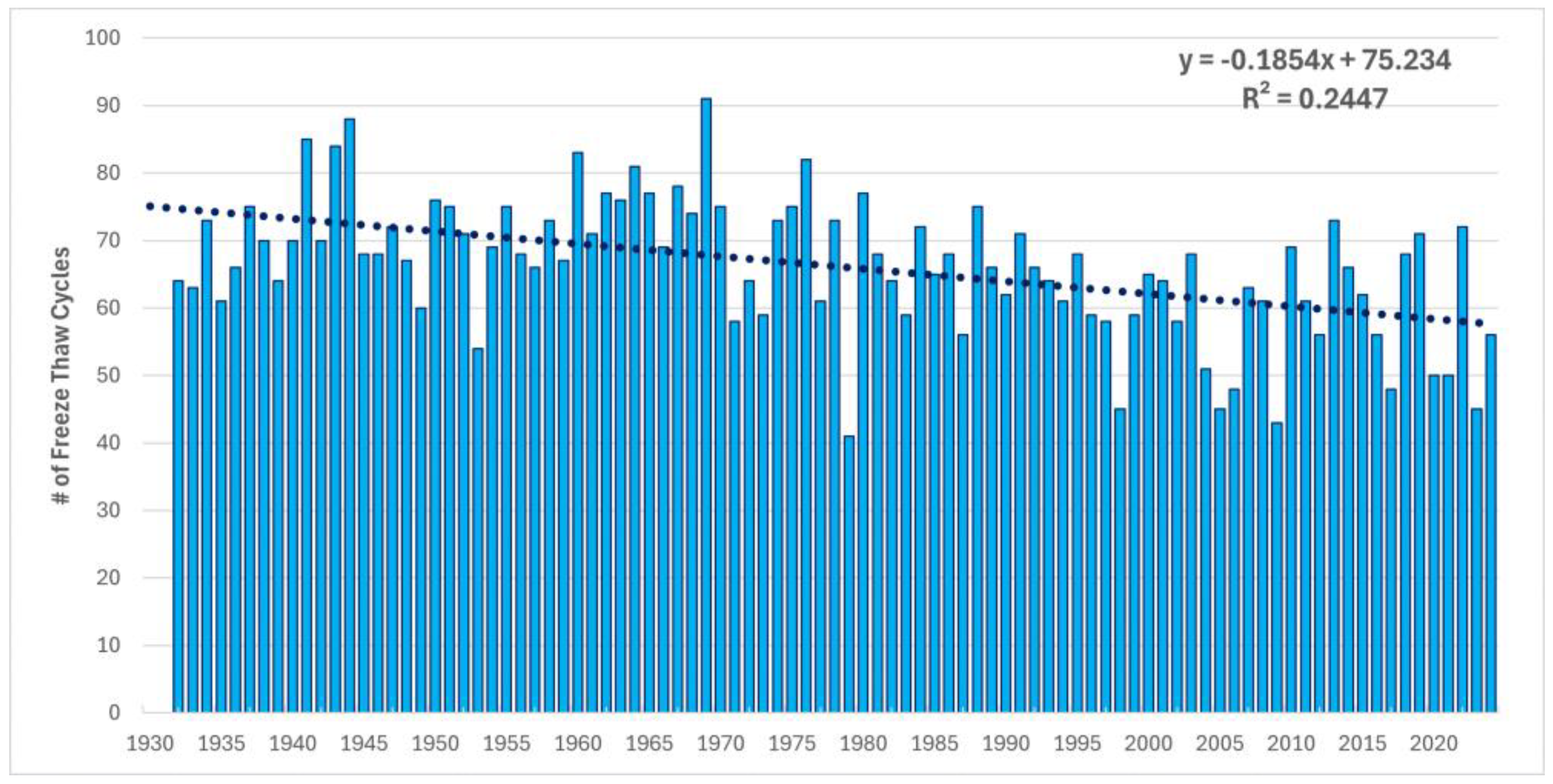

The trends used for freeze-thaw cycle predictions were derived from historical weather, obtained from the NOAA weather station based in Wilmington, Delaware. An empirical relationship, represented by Equation 1, was established using this dataset and subsequently plotted against the freeze-thaw cycle counts reported in InfoBridge™, as shown in

Figure 21. The resulting correlation was used to estimate annual freeze-thaw frequencies, which were then incorporated into the deterioration modeling presented later in this analysis. The number of freeze thaw cycles since construction is given by:

(1)

(2)

Where: ̶ Number of Freeze-Thaw cycles since construction

T - Years since construction

Tc - Current year

Ti - Year of construction

This equation was derived from the linear trend as shown in

Figure 22. The equation presented in the figure was integrated over the interval from 0 to T (where T represents the number of years since construction) to derive an empirical relationship linking the area's climate data with the structure's age.

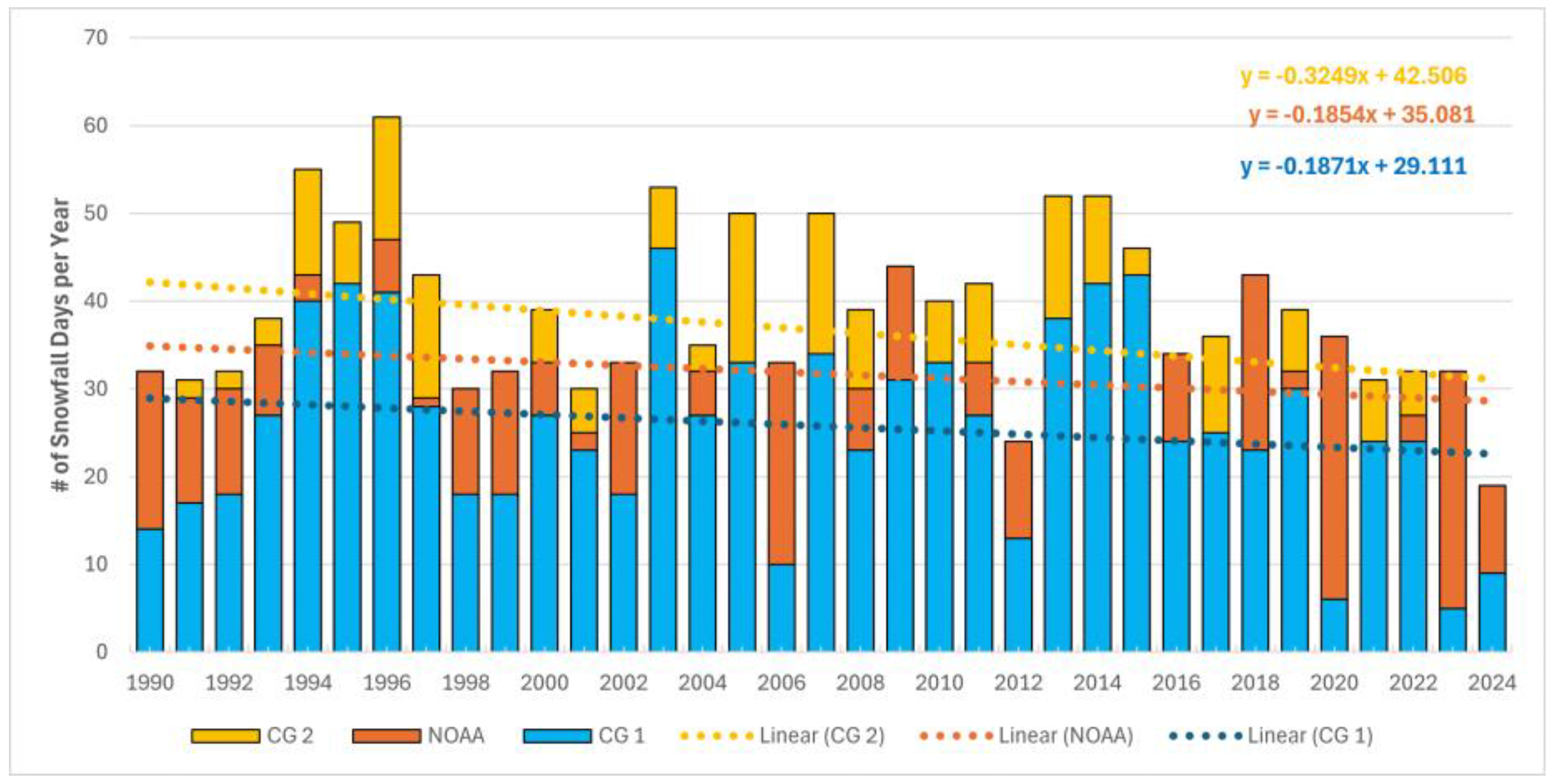

Snow Day Predictions

Snow day predictions were developed using historical weather data presented in

Figure 23, obtained from InfoBridge™ for the bridges located along the I-495 viaduct in Wilmington, Delaware. An empirical relationship, represented by Equation 3, was derived from this dataset, and the resulting correlation was used to estimate the frequency of annual snow days. These estimates were subsequently incorporated into the deterioration modeling presented later in this analysis. Snow day frequency served as a key variable in estimating long-term chloride accumulation, as deicing salt application during snow events represents a primary source of chloride ingress in bridge decks. Number of Snow Fall Days Since Construction is given by:

(3)

(4)

Where:

NSD Number of Snow Days since construction

T Years Since Construction

TC Current Year

Ti Year of Construction

This equation was derived from the linear trend as shown in

Figure 22. The equation presented in the figure was integrated over the interval from 0 to T (where T represents the number of years since construction) to derive an empirical relationship linking the area's climate data with the structure's age.

5.1.3. Wet-Dry Cycles Predictions

Wet-dry cycle predictions were developed using historical climate data presented in Figure 22, sourced from InfoBridge™ regional precipitation records relevant to the I-495 Viaduct in Wilmington, Delaware. An empirical relationship, expressed as Equation 5, was established to estimate the frequency of wet-dry cycling based on precipitation patterns and drying intervals. This correlation was used to determine annual wet-dry cycle counts, which were then integrated into the deterioration modeling presented later in this analysis. The frequency of wet-dry cycles plays a critical role in the transport of chlorides into concrete and the progressive breakdown of material integrity over time. Number of wet-dry cycles since construction is given as:

(5)

NWDCycles Number of Wet-Dry Cycles since construction

5.2. Experimental Trends

This section presents the trends observed from accelerated laboratory testing of concrete specimens. Key physical and mechanical properties, including compressive strength, modulus of elasticity, resonance frequency, and chloride penetration, were monitored over time. The data highlights the material’s degradation behavior under different environmental conditions and helps establish baseline patterns necessary for predictive modeling.

Resonance Frequency Trends

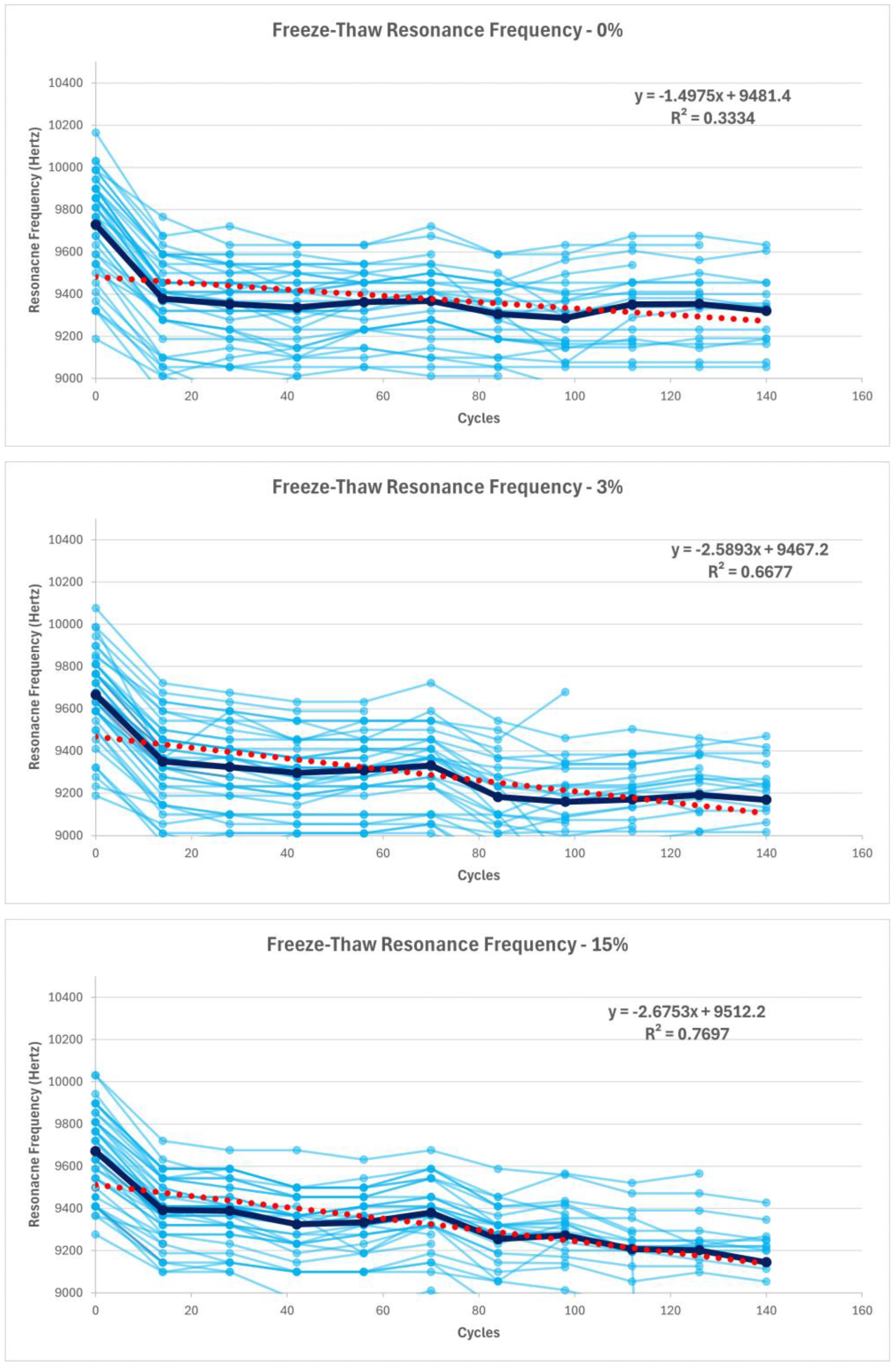

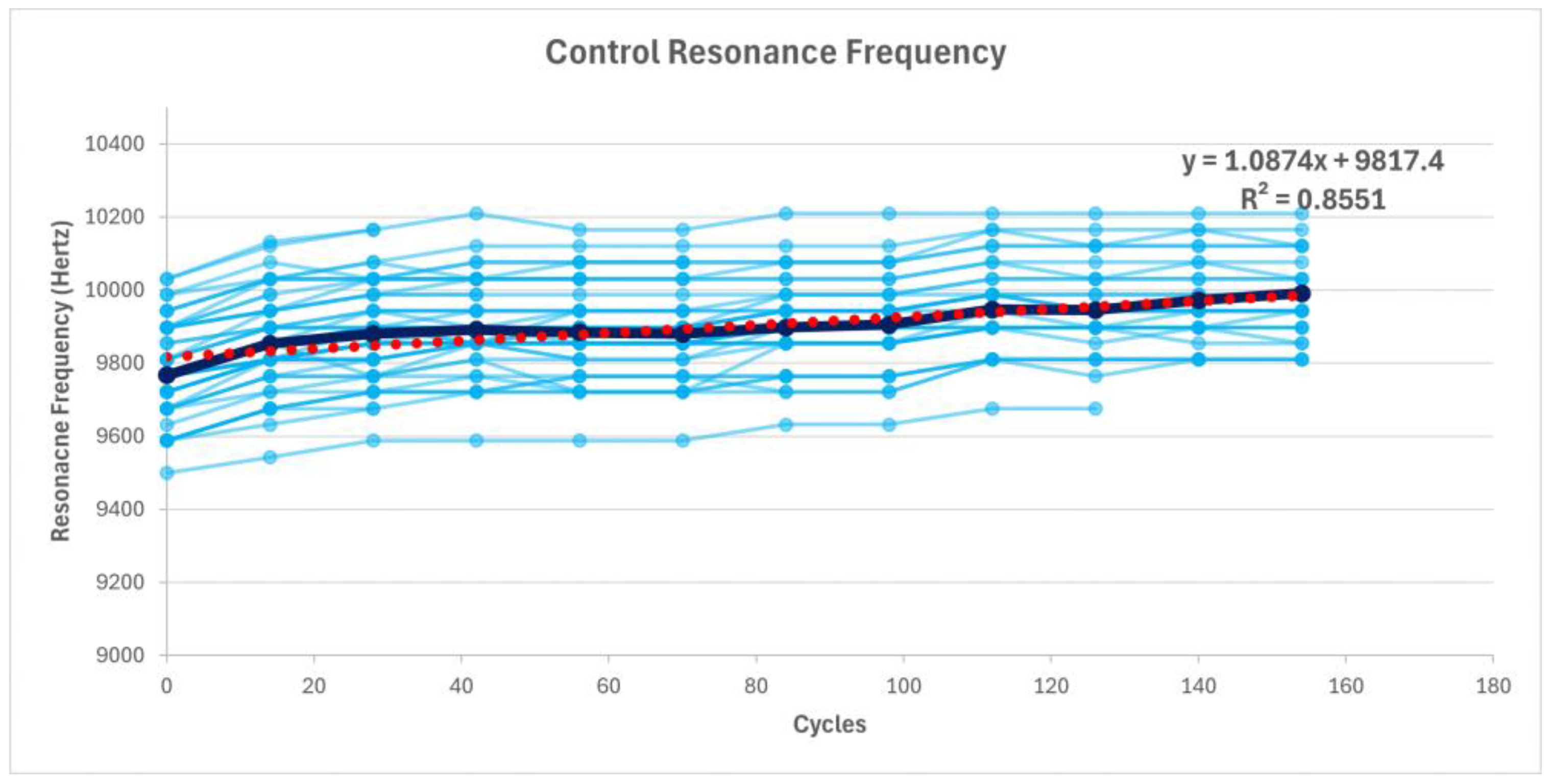

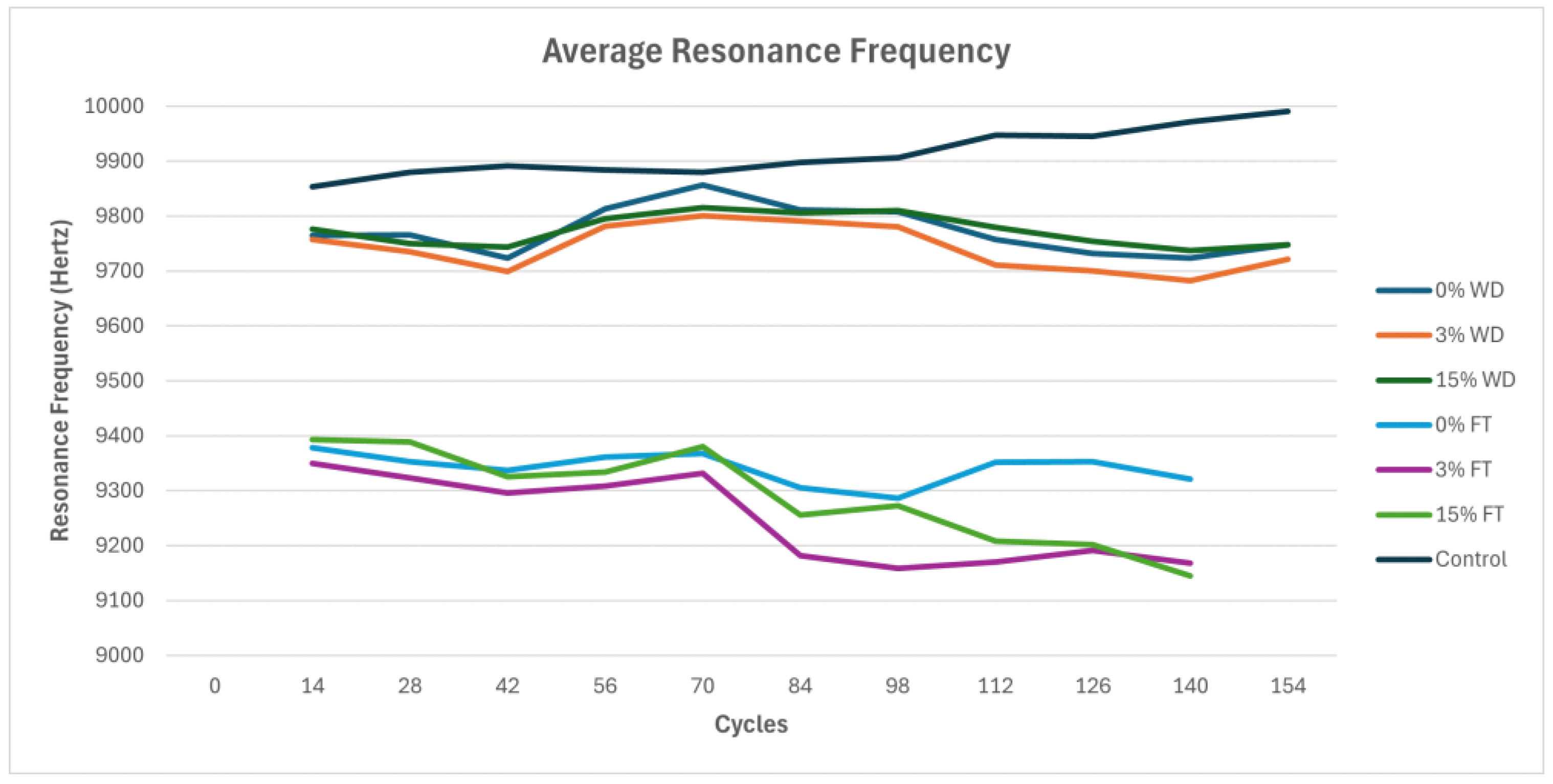

As the resonance frequency data represented the most extensive dataset collected during the experimental phase of this study, its trends were identified as the most significant and consistent indicators of long-term strength loss due to environmental cycling. As shown in

Figure 24, the average resonance frequency for each environmental condition has been plotted to illustrate the overall trend in material degradation over the course of the experimental study. These trends provide valuable insight into the progressive loss of structural integrity in concrete specimens subjected to repeated freeze-thaw and wet-dry cycles

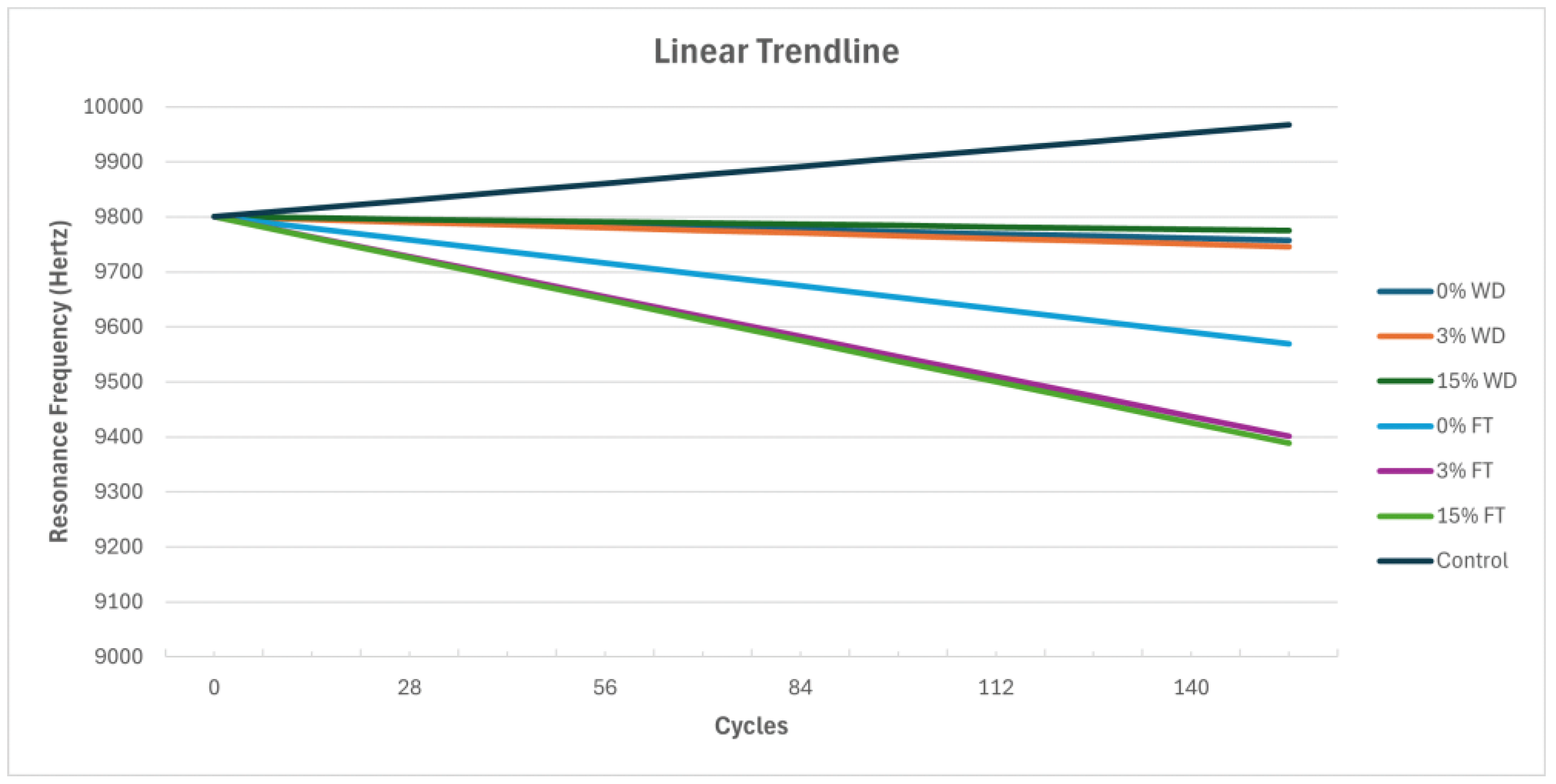

To generate reliable long-term predictions, it was necessary to first establish clear trends from experimental data. The linear trendlines were ultimately deemed more appropriate for representing long-term strength loss due to environmental cycling as seen in

Figure 25, offering a more stable and realistic basis for predictive modeling which the equations for each cycling conditions can be seen in Equations (6-12).

The resonance frequency trends equations given are as follows:

For wet-dry resonance trends

(6)

Number of Wet-Dry cycles since construction

Resonance Frequency (Hz) after N number of Wet-Dry Cycles in 0% salinity solution

(7)

Resonance Frequency (Hz) after N number of Wet-Dry Cycles in 3% salinity solution

(8)

Resonance Frequency (Hz) after N number of Wet-Dry Cycles in 15% salinity solution

For freeze-thaw resonance trends it is given as:

Number of Freeze-Thaw cycles since construction

(9)

Resonance Frequency (Hz) after N number of Freeze-Thaw Cycles in 0% salinity solution

(10)

Resonance Frequency (Hz) after N number of Freeze-Thaw Cycles in 3% salinity solution

(11)

Resonance Frequency (Hz) after N number of Freeze-Thaw Cycles in 15% salinity solution

For controlled conditions resonance trends is given as:

(12)

Resonance Frequency (Hz) after T days curing in Control Conditions

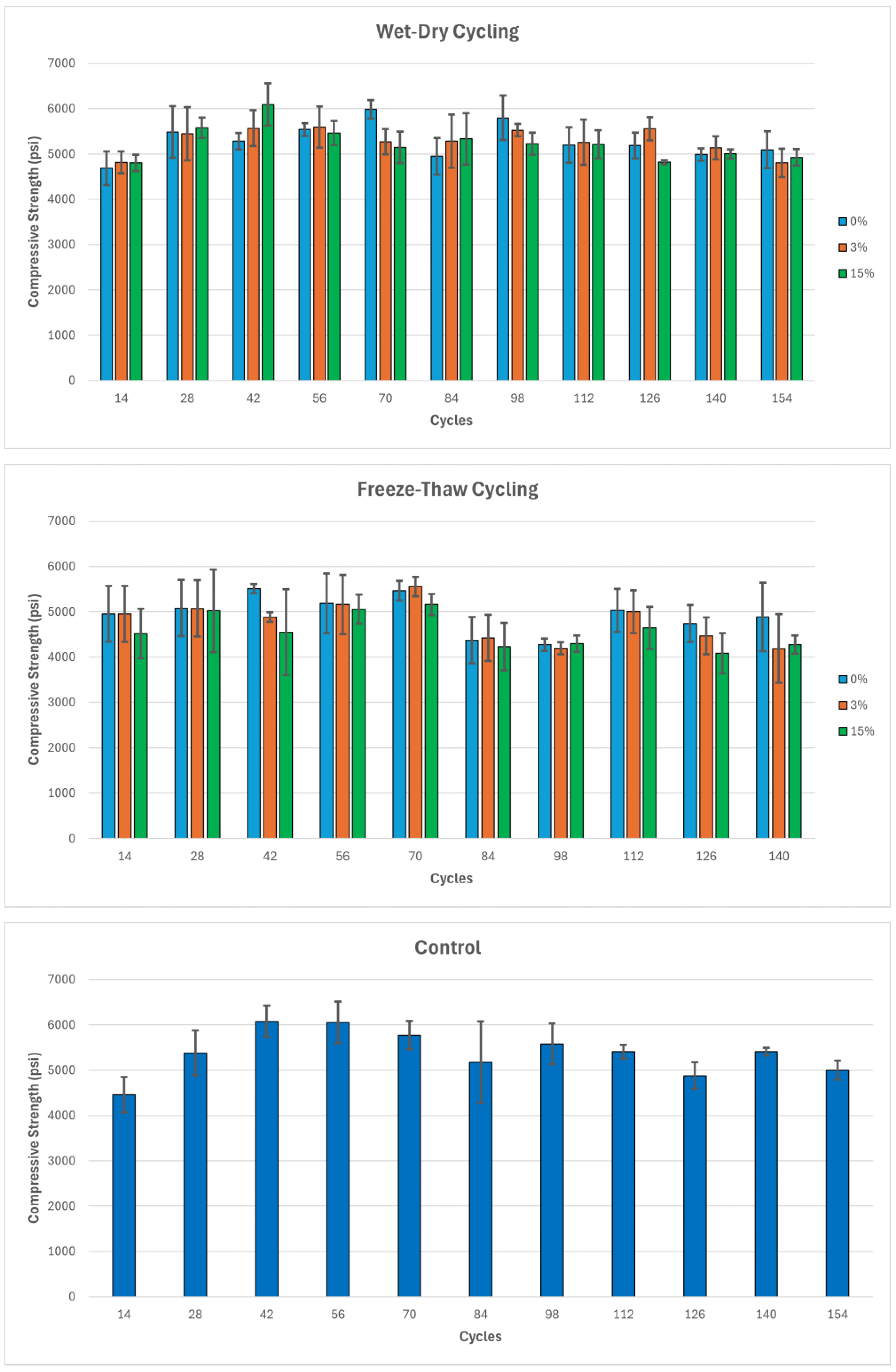

Compressive Strength Trends

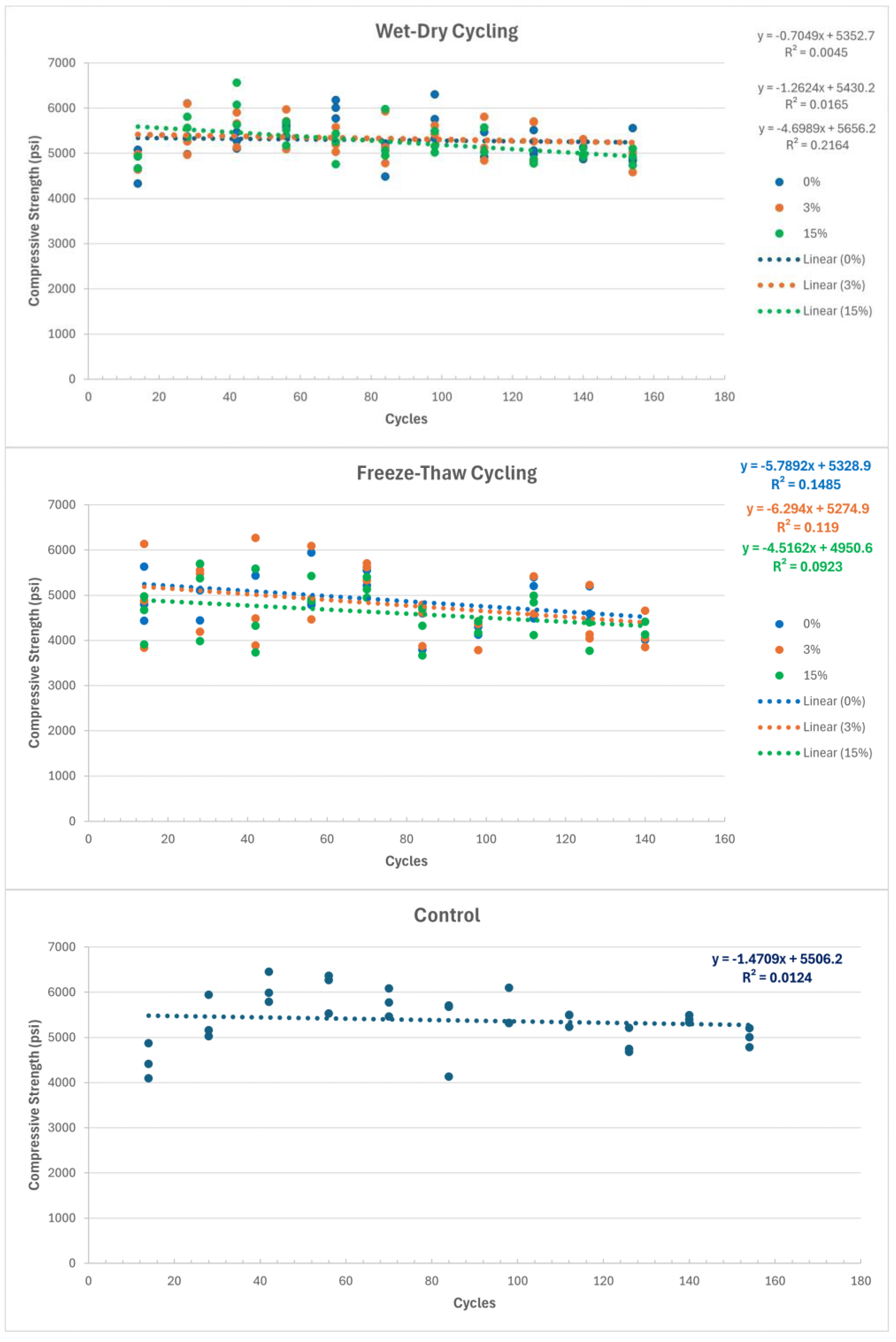

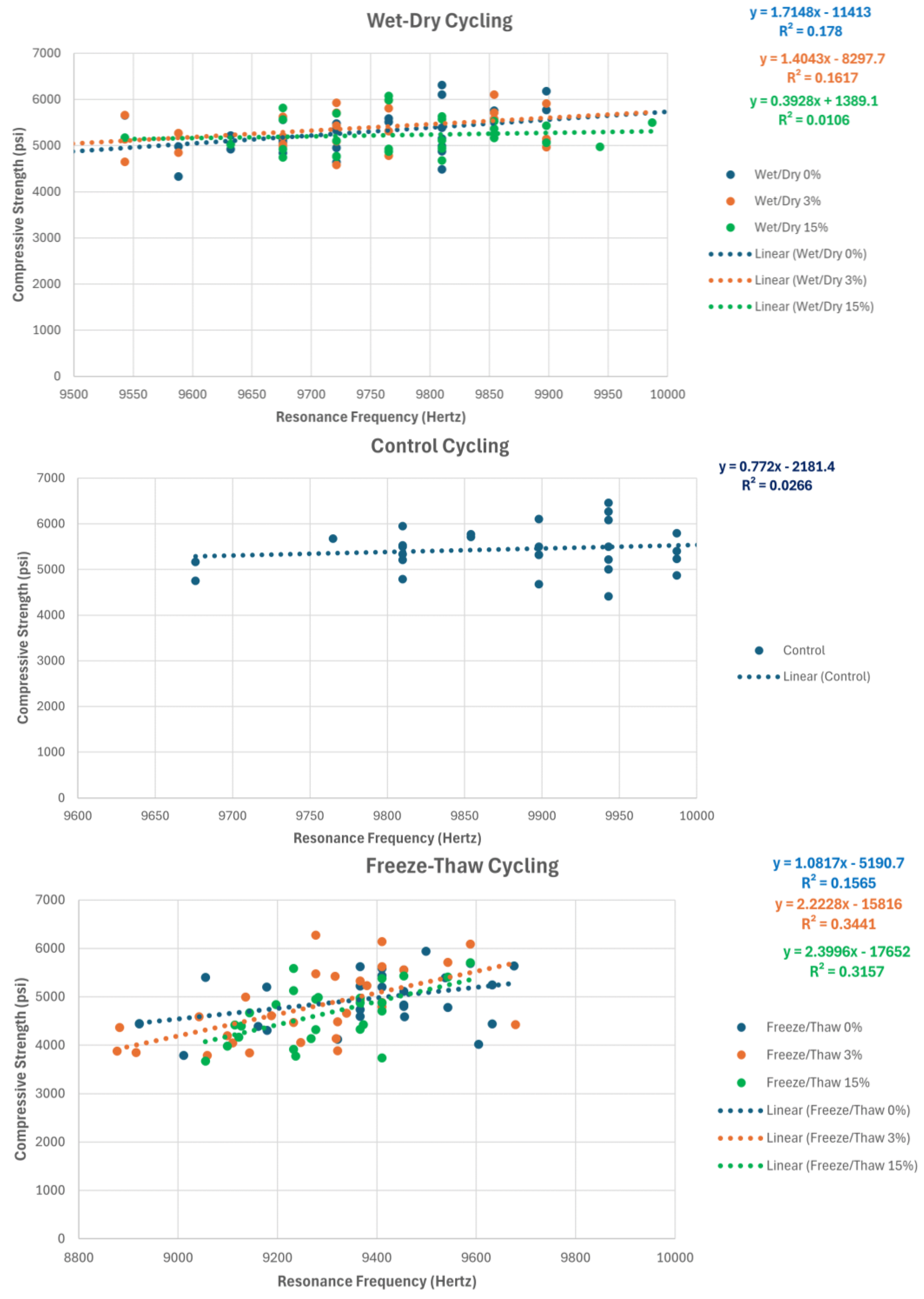

Although compressive strength was the primary performance indicator targeted for mapping deterioration over the course of environmental cycling, the high degree of variability in the experimental outcomes presented challenges for generating reliable long-term forecasts. As illustrated in

Figure 26, the degradation trends for compressive strength exhibited relatively low R

2 values across most environmental conditions, suggesting a weak correlation and reducing their suitability for predictive modeling. This variability is likely due to minor inconsistencies in specimen fabrication, curing conditions, or environmental exposure during testing. As a result, compressive strength data was not used directly in the formulation of deterioration forecasting models. Nevertheless, it served an important role in the validation process, offering a comparative reference to verify the accuracy of other predictive indicators, particularly resonance frequency. Additionally, compressive strength results contributed to the identification and calibration of deterioration factors, helping to shape the overall modeling approach used in this study.

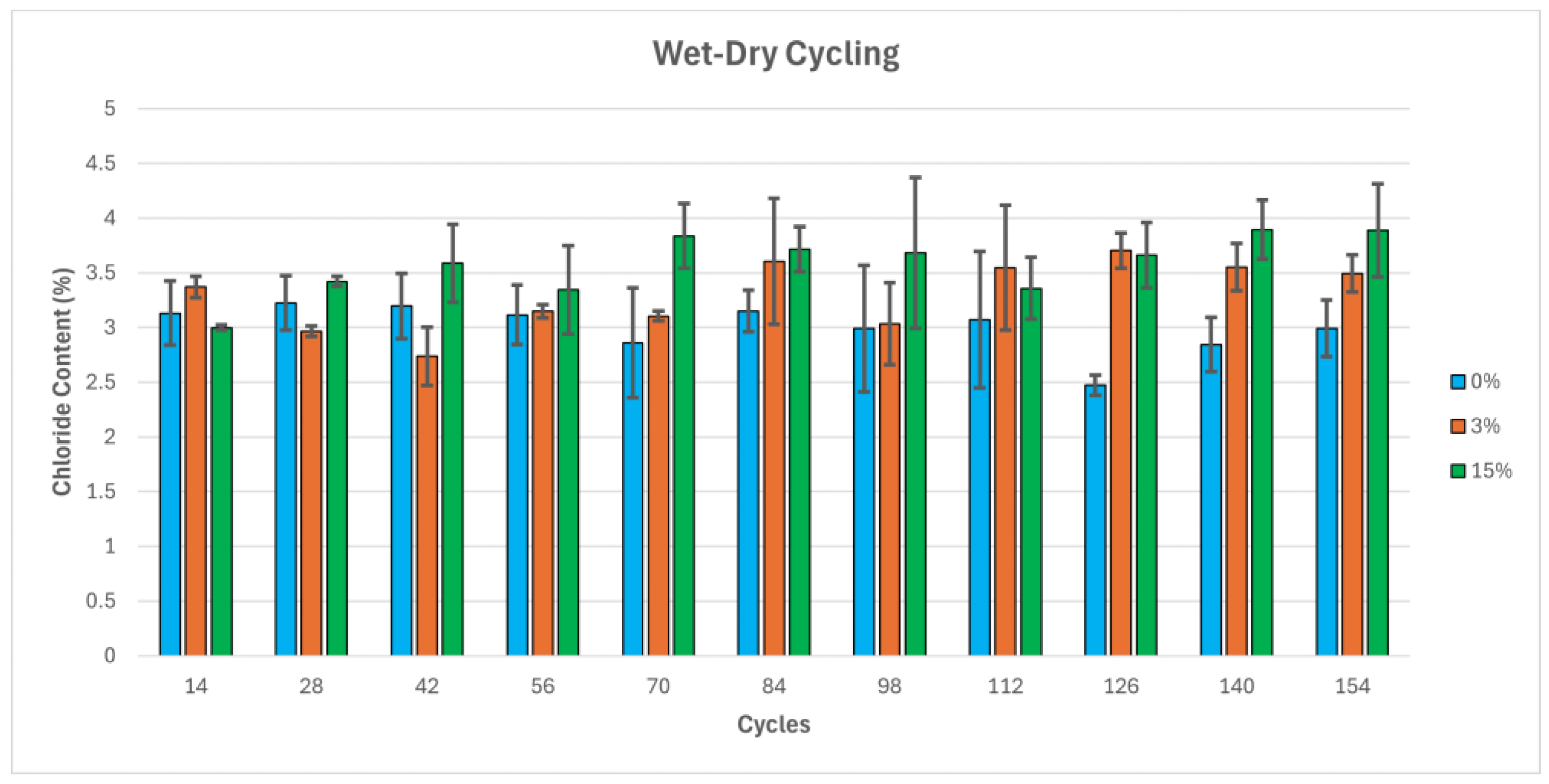

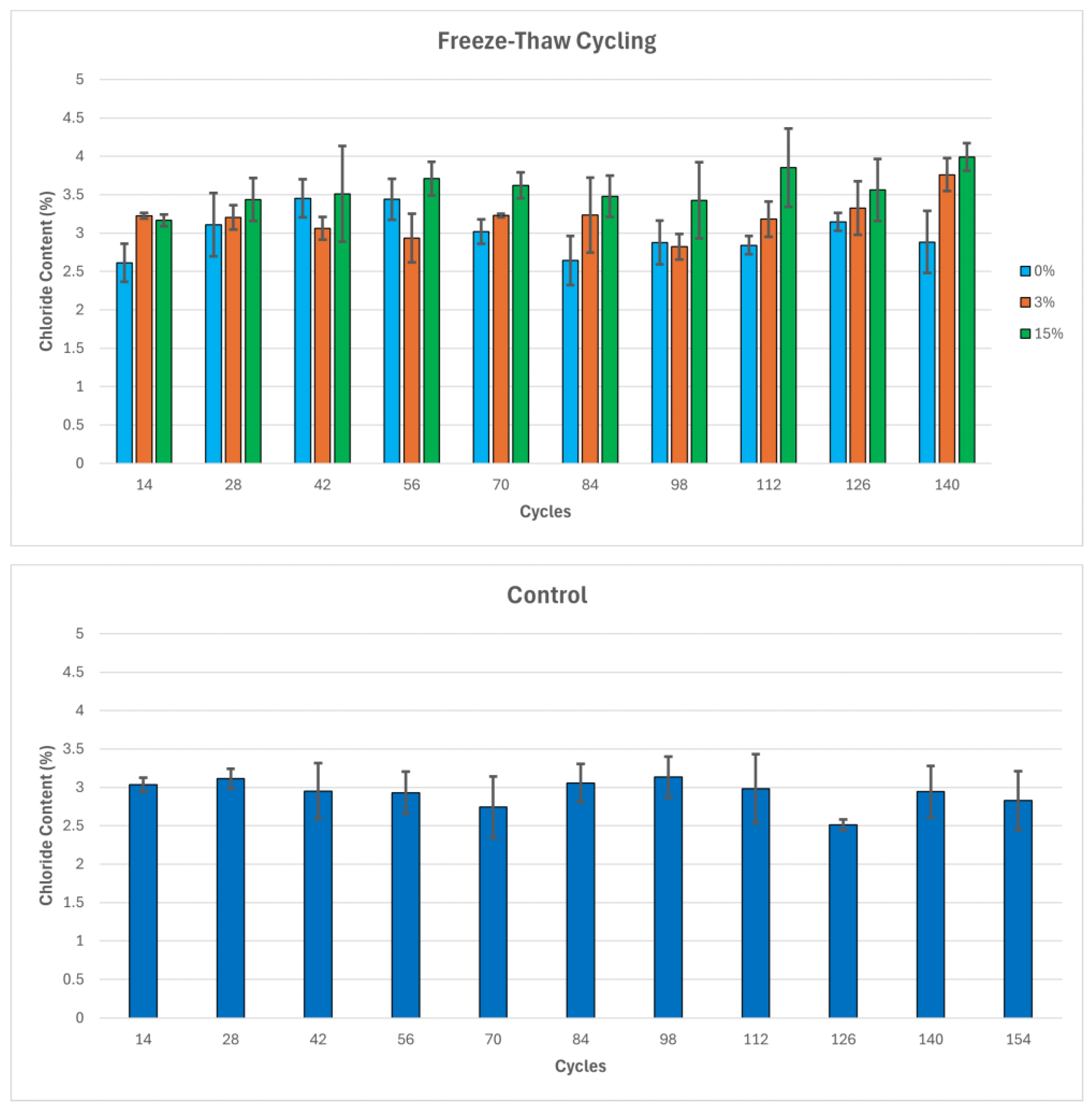

Chloride Trends

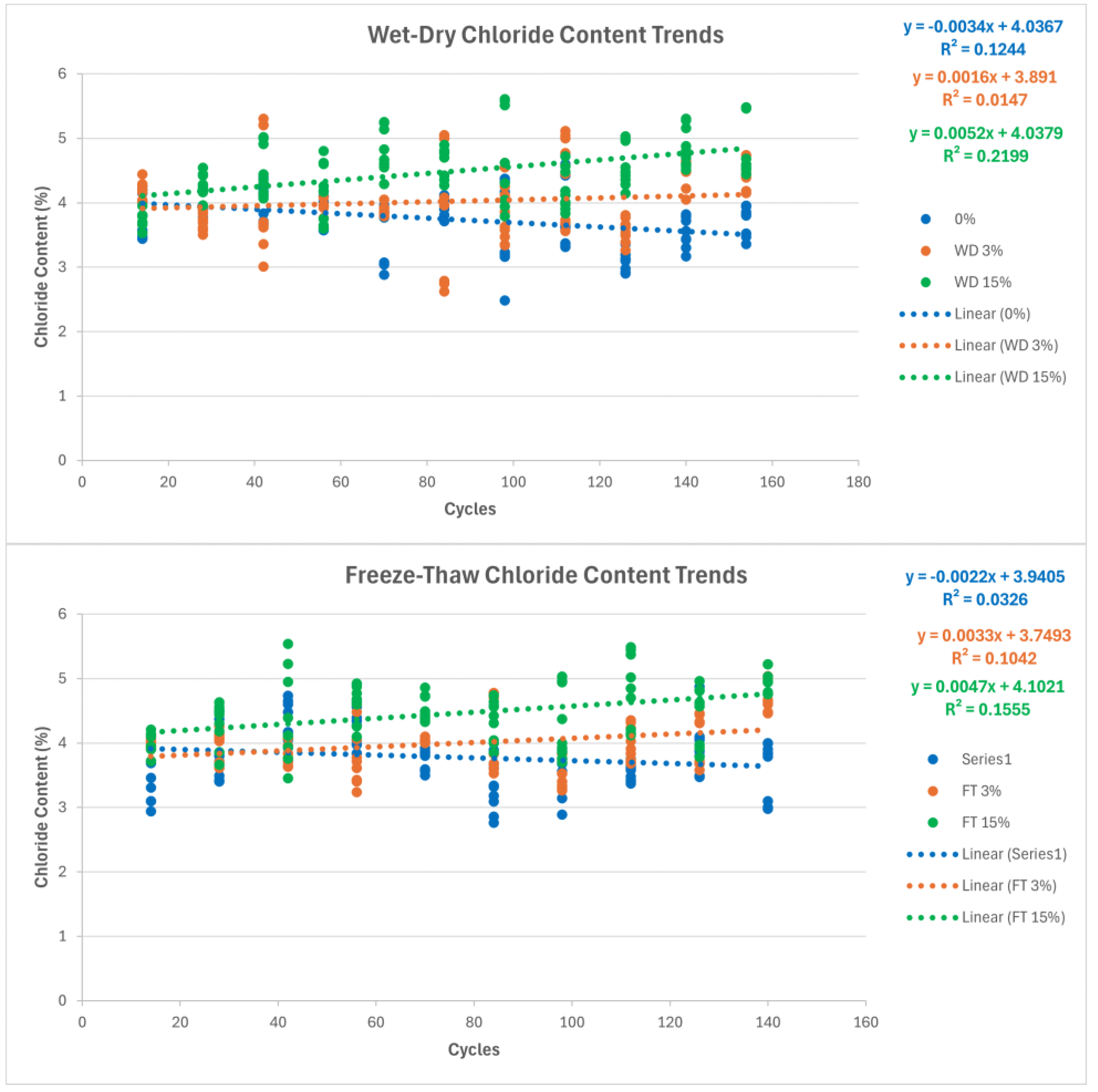

As chloride-induced deterioration formed the central focus of this research, collecting a robust and comprehensive dataset was essential for drawing meaningful conclusions and identifying reliable trends. The progression of chloride intrusion directly influences the long-term durability of concrete, particularly under repeated environmental cycling. As shown in

Figure 27, the average chloride content for each environmental condition has been plotted to illustrate the overall trend in chloride accumulation over the course of the experimental study. These trends provide valuable insight into the rate of chloride ingress under varying exposure scenarios and serve as a foundational input for the development of predictive deterioration models used later in this analysis. While there are more accurate methods like Fick’s second law for one-dimensional diffusion [

31], for this study the selected samples being fully submerged leads to a potential conflict with this equation. It could have been proven useful if the samples were removed from a testing slab instead of cast shapes, but this is a concept that can be explored more in future work.

The graphs shown also reveal the presence of naturally occurring chloride concentrations characteristic of concrete as a material. Such inherent concentrations are embodied by the y-intercepts of the trendline equations derived from the experimental results. However, for the purpose of deterioration modeling, it was deemed that the slope of every trendline, representing the rate of chloride ingress over time, formed the most critical information. Thus, the y-intercepts were removed from further calculation, and the trendlines were reset to begin at zero for application in Equation 13. This provided a more realistic portrayal of chloride accumulation that is strictly a function of environmental exposure, as opposed to original material variability. Although this remains one of the least developed aspects of the study, it must be mentioned that chloride ingress is a highly complex process that does not undergo strict linear movement through the concrete matrix. Variability in pore structure, variability in moisture content, and variability in exposure conditions all result in non-linear penetration of chloride. Nonetheless, because this research primarily examines the link between chloride exposure and deterioration of concrete strength, a simple methodology was adopted for modeling. The need for a more extensive exploration of the mechanisms of chloride transport, especially non-linear diffusion characteristics and binding interactions, is identified and noted for future work.

Chloride Content (CC) Prediction for Light and Harsh conditions

(13)

(14)

5.3. Predictive Model

Building on the experimental trends, this section introduces the predictive models developed to estimate long-term bridge deck deterioration. Using deterioration envelopes derived from laboratory data and environmental exposure variables, these models project performance outcomes across various scenarios. The objective is to enhance forecasting accuracy for material degradation, ultimately informing more strategic maintenance planning.

In

Figure 28, the general correlation between resonance frequency and compressive strength demonstrates positive relationships, where higher resonance frequencies correspond to greater compressive strengths. Linear trendlines representing the reduction in resonance frequency and compressive strength are plotted on opposing axes to effectively illustrate this relationship through their slopes. Despite the similar overall trends, the resonance frequency exhibits a more gradual decline, aligning closely with anticipated outcomes based on in situ laboratory observations.

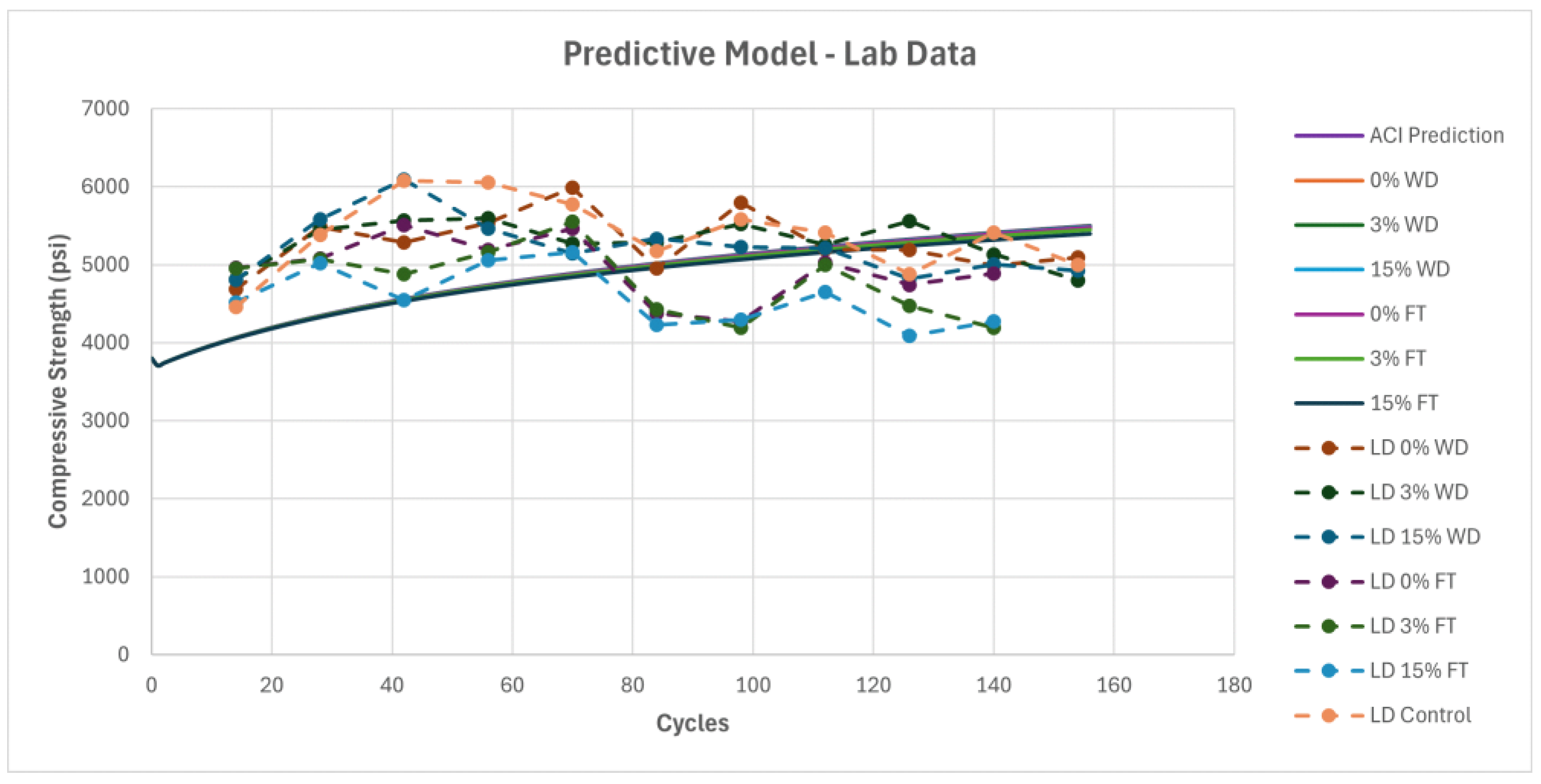

The observed resonance frequency trends were subsequently converted into corresponding compressive strength trends. Since the deterioration equations derived from this study represent a linear decline in compressive strength over time, it was necessary to account for the early-age strength gain typically seen in concrete. To do so, the compressive strength development behavior described in Washa’s Fifty Year Properties of Concrete was incorporated into the model. The resulting combined equation, presented in Equations (22-27) , integrates both the initial curing-related strength gain and the long-term environmental deterioration observed during laboratory testing. This composite model was then compared to the experimental results to evaluate its accuracy and predictive capability, with the comparison graphically displayed in

Figure 29.

Predicted Concrete Strength Gain equation is given by:

(15)

Where:

Predicted Concrete Strength Gain

Concrete Strength at 28 days

T = Number of days cured

Compressive Strength Loss Rates equation is given by:

Wet-Dry Strength Loss Rates Equations

(16)

= Strength Loss rate due to Wet-Dry Cycling in 0% Saline Solution

(17)

= Strength Loss rate due to Wet-Dry Cycling in 3% Saline Solution

(18)

= Strength Loss rate due to Wet-Dry Cycling in 15% Saline Solution

Freeze-Thaw Strength Loss Rates Equations

(19)

= Strength Loss rate due to Freeze-That Cycling in 0% Saline Solution

(20)

= Strength Loss rate due to Freeze-That Cycling in 3% Saline Solution

(21)

= Strength Loss rate due to Freeze-That Cycling in 15% Saline Solution

The strength loss of concrete after deterioration cycles is given as:

Wet-Dry Strength Loss Equations

(22)

(23)

(24)

Freeze-Thaw Strength Loss Equations

(25)

(26)

(27)

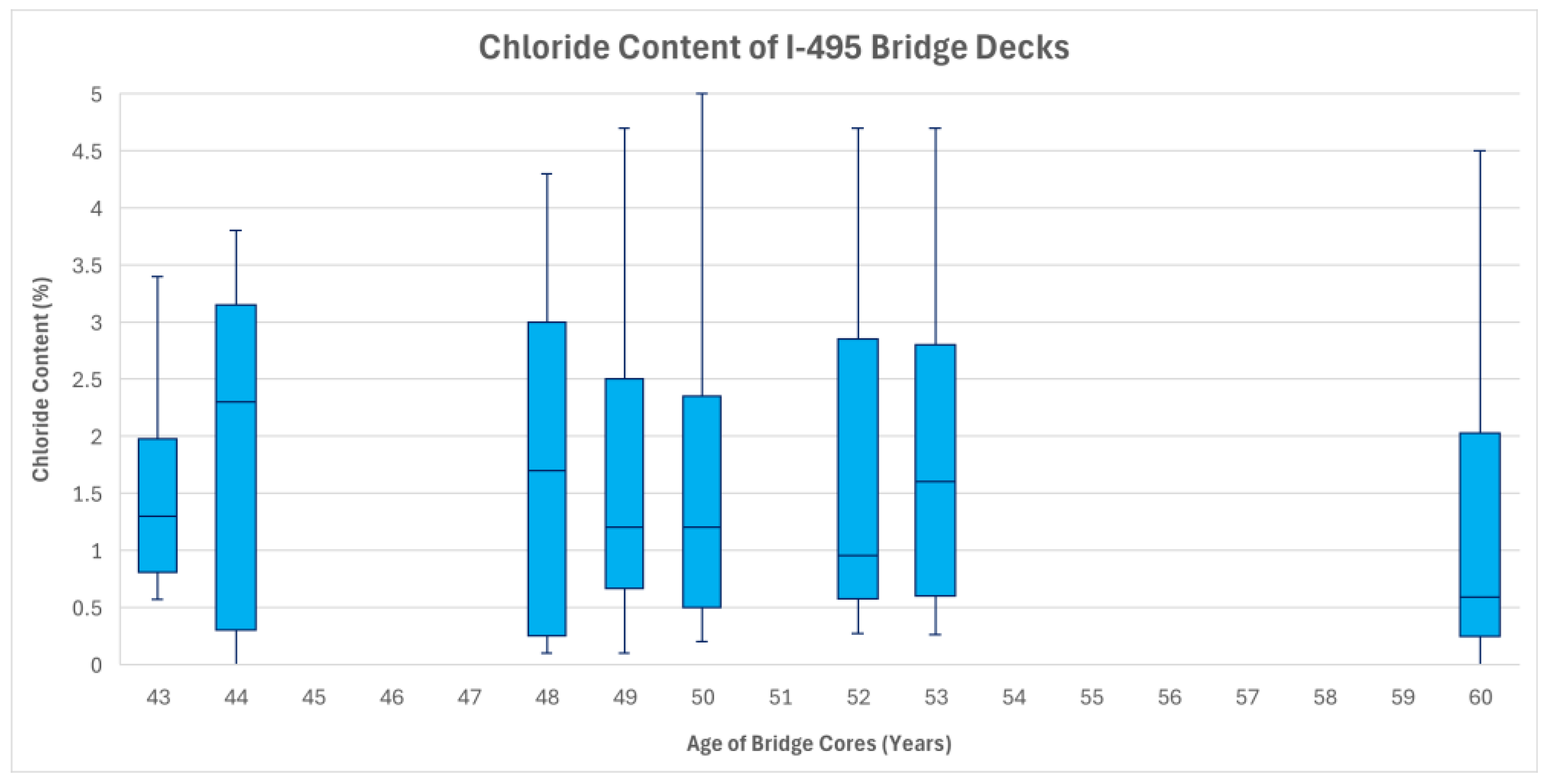

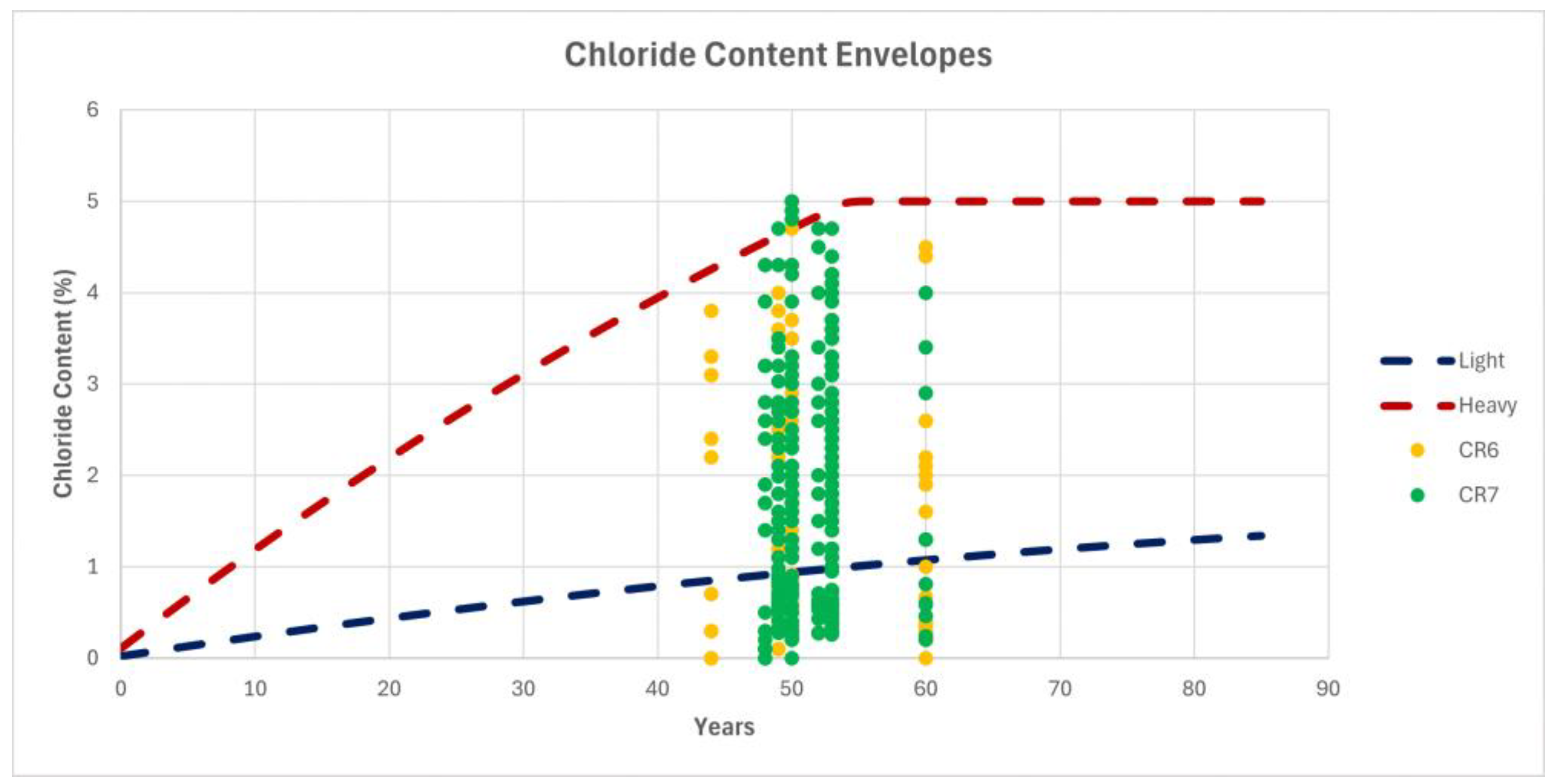

The chloride trends derived from Equation 6.5 were adjusted by reducing the calculated rates by half to better reflect in-situ chloride exposure conditions. The original trends were based on continuous soaking in high-salinity solutions, resulting in artificially elevated rates of chloride ingress that do not accurately represent real-world bridge deck conditions. By scaling down these trends, the revised model provides a more realistic estimate of chloride accumulation over time. These refined trends, alongside data from in-situ bridge core samples, have been plotted in

Figure 30 to illustrate the relationship between predicted and observed chloride concentrations. Additionally, an artificial cap of 5 % chloride concentration was applied to represent the maximum expected chloride saturation in the concrete matrix. As it was not possible to verify the chloride reports examined in the study, the chloride contents above 5% were not examined. This assumption was based on the concrete used in bridge deck construction having an air content between 5% and 7%, consistent with the parameters employed in the experimental phase of this study. If the air content exceeds this range, chloride accumulation from NaCl exposure would no longer be the sole factor influencing deterioration. This threshold acknowledges the physical limitations on chloride storage within concrete’s pore structure, as indefinite chloride accumulation is impractical due to the finite capacity available for ion absorption and binding.

The chart also illustrates the initial relationship between condition state and chloride content. However, no significant variation is observed, as the investigated bridge decks fall exclusively within Condition States 6 and 7. This limited range restricts broader comparisons across condition states and highlights the need for additional data from earlier deterioration stages to fully understand the progression of chloride-induced damage over time.

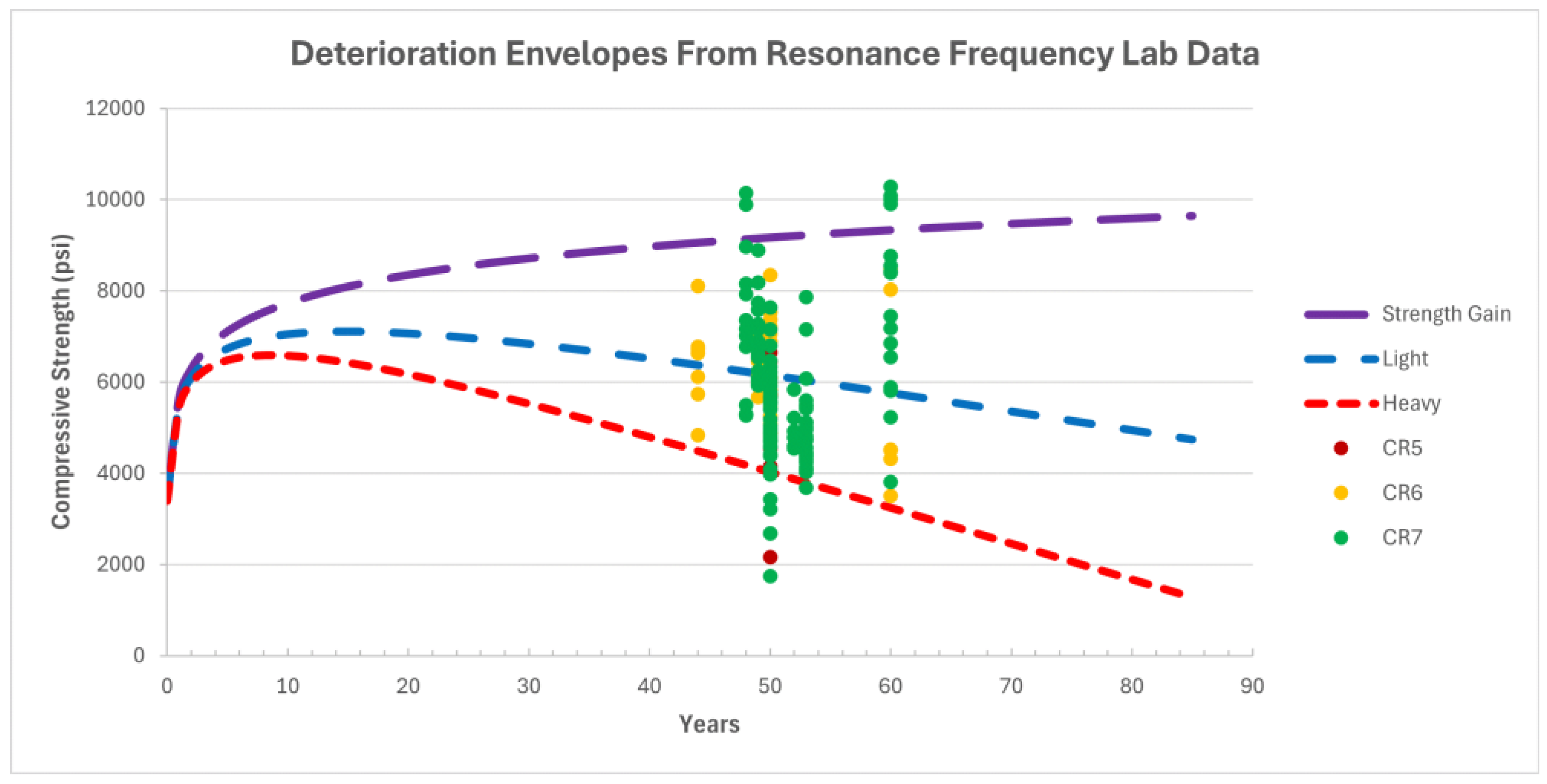

5.4. Durability Envelope

At the core of this research is the development of a durability envelope designed to predict the strength loss of concrete bridge decks as a function of chloride content over their expected service life. The predictive equations, outlined as Equations (28-29), represent a synthesis of the various environmental and material factors discussed throughout this chapter. These models are graphically illustrated across a bridge's lifespan in

Figure 31. Included in the figure is the standard ACI concrete strength projection derived from Washa’s long-term study [

28], represented by Equation 15, which serves as a baseline for undisturbed concrete performance.

To account for varying environmental exposure conditions, three deterioration mechanisms were modeled. The light deterioration mechanism is based on the trends observed in specimens subjected to 0% wet-dry and 0% freeze-thaw cycling and is represented by Equations (28-29). The moderate deterioration mechanism draws on trends from the 3% wet-dry and 3% freeze-thaw conditions, shown in Equation 6.9. Finally, the heavy deterioration mechanism reflects trends from the 15% wet-dry and 15% freeze-thaw scenarios. Each of these models begins with the ACI-predicted strength gain and then subtracts projected losses due to environmental cycling, adjusted for the age of the structure. Collectively, these equations form the durability envelope, offering a practical framework for forecasting bridge deck performance under various levels of environmental stress.

Equation 5.9: Deterioration Curve Equations

(28)

(29)

Strength Gain Prediction

Strength Loss due to Wet-Dry Cycling in

Strength Loss due to Freeze-Thaw Cycling

To illustrate the relationship between the developed deterioration envelope and real-world conditions, the compressive strengths and corresponding condition ratings of the in-situ bridge core samples have been plotted alongside the model in

Figure 31. This comparison allows for a preliminary validation of the model against actual field data. However, similar to the limitations observed in the salinity trend analysis, the narrow range of condition ratings, primarily limited to higher deterioration state, restricts the ability to draw meaningful correlations between condition rating and compressive strength loss. As a result, while the comparison provides some insight, the limited variability in condition states reduces the effectiveness of this dataset in fully validating the deterioration envelope across a broader spectrum of bridge performance stages.

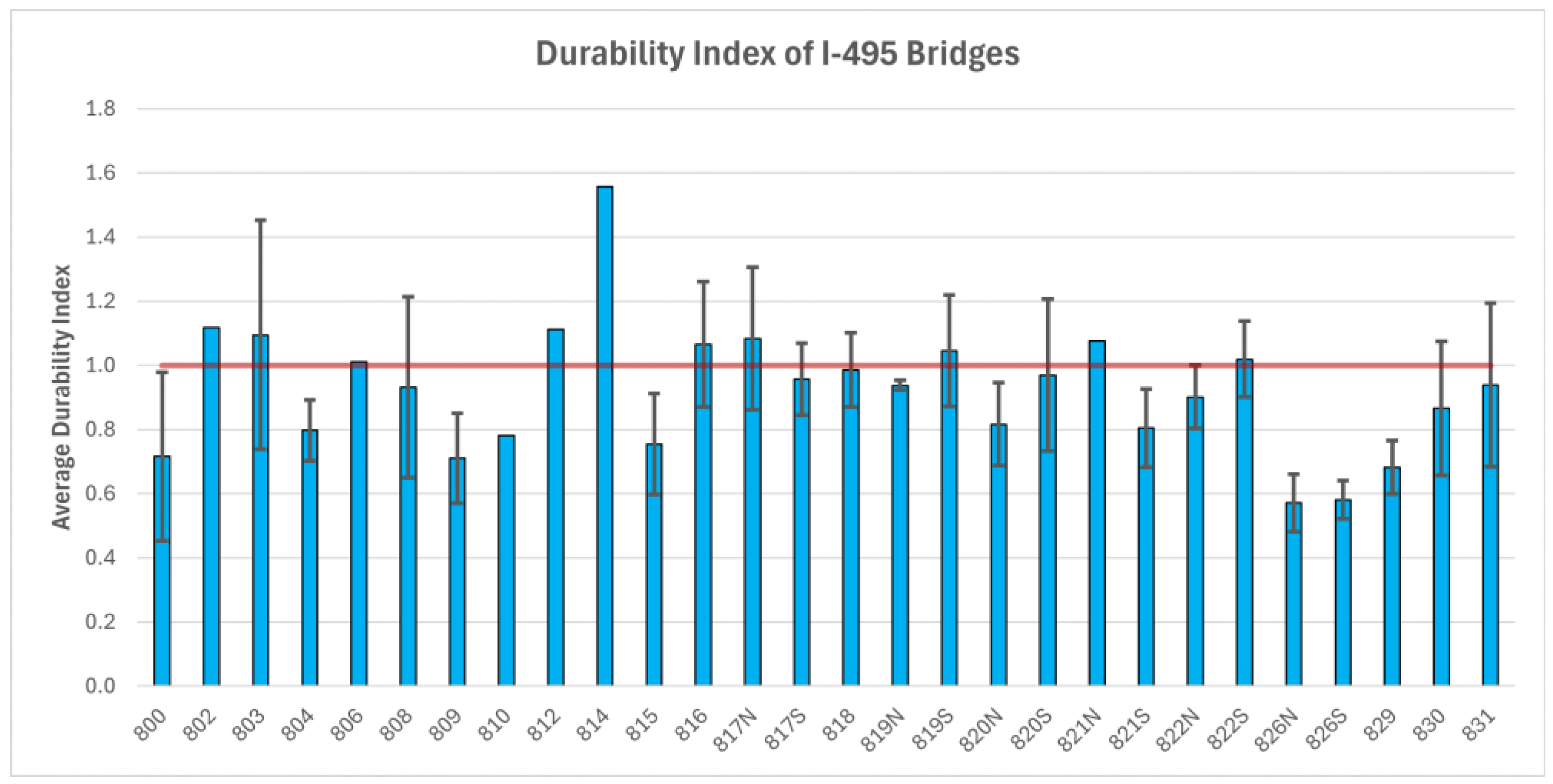

5.5. Durability Index

Simply plotting the compressive strengths of the bridge core samples on the deterioration envelope does not fully capture the condition of the bridge decks in relation to their predicted performance. To address this limitation, a Durability Index was developed using both laboratory data and field core sample results. This index serves as a comparative metric to evaluate the resilience of concrete bridge decks subjected to chloride-induced deterioration. The determination of the index is based on two key components: the measured chloride content of each bridge core, which is used to categorize the sample into one of the predefined deterioration mechanisms (light or heavy), and a comparison between the measured compressive strength and the predicted strength for that category. The resulting index provides a normalized representation of how well a given bridge deck is performing relative to its expected condition. This evaluation is graphically represented in Figure 32, offering a more nuanced understanding of in-situ bridge performance beyond basic strength measurements.

A Durability Index rating below 1 indicates that the measured compressive strength of a bridge core is lower than the predicted value for its corresponding deterioration mechanism. This suggests that additional factors, beyond those modeled, may be contributing to an accelerated loss in strength. These factors include overloading from large vehicles, improper maintenance, improper construction, or other environmental factors not considered in this study or defects in the materials used in construction. A rating of exactly 1 signifies that the measured strength equals the predicted value, indicating that the bridge deck is performing as expected under its environmental exposure conditions with this value being highlighted with the red line across the figure. A rating above 1 reflects a measured strength that exceeds the predicted value, which is the most desirable outcome, as it suggests the bridge deck is demonstrating greater resilience than anticipated.

6. Conclusions

This study produced several key insights into concrete deterioration mechanisms under wet-dry and freeze-thaw exposure with varying chloride concentrations. By combining nondestructive resonance frequency measurements with compressive strength, modulus of elasticity, Poisson’s ratio, and water-soluble chloride content, the work linked internal damage, stiffness loss, and chemical ingress for both laboratory specimens and in situ bridge cores from Delaware. The case study on Interstate 495 showed how these laboratories findings relate to actual bridge deck performance and current maintenance practice, supporting more informed planning of preservation and repair strategies. The following key findings summarize the most impactful outcomes:

Laboratory testing demonstrated that concrete specimens exposed to alternating environmental stressors, wet-dry and freeze-thaw cycles combined with varying chloride concentrations, underwent progressive degradation over time.

Among all measured properties, resonance frequency was the most sensitive and reliable indicator of internal damage. Resonance frequency measured in Hertz (Hz) consistently declined across all exposure conditions, signaling microstructural deterioration that preceded measurable strength loss. This makes resonance frequency a valuable early predictor of material degradation

Chloride concentration increased with exposure time, even when no surface deterioration was visible. This shows that significant internal damage can develop long before visual symptoms appear, so subsurface monitoring is necessary.

Core samples taken from bridges along Interstate 495 in Wilmington, DE showed good correlation with the laboratory findings. The cores covered a wide range of compressive strength and chloride content. Although these bridges were rated in “Good” condition according to National Bridge Inventory (NBI) standards, many samples already exhibited chloride accumulation and reduced strength, revealing the limitations of relying solely on surface-based inspection techniques.

The disconnect between visual condition ratings and measured material performance shows that traditional inspections can overlook critical internal damage. This supports the need to incorporate material-based and nondestructive testing methods into routine bridge assessments, including subsurface monitoring techniques such as ground penetrating radar (GPR).

A deterioration envelope framework was established, integrating laboratory results, field core data, and environmental exposure variables, including NOAA climate data and FHWA InfoBridge™ parameters (snow day frequency, freeze-thaw frequency, and time of wetness of bridge structures).

The resulting models demonstrated a new multifaced technique in estimating structural aging trends and service life under various environmental conditions. These tools support more proactive and data-driven maintenance strategies, enhancing long-term planning and management of concrete infrastructure.

As a practical implication for infrastructure asset management, this study provides actionable results for transportation agencies such as the Delaware Department of Transportation (DelDOT). It offers an alternative way to assess bridge deck deterioration beyond visual inspection frameworks like the National Bridge Inventory (NBI), which can miss internal damage, particularly in decks with corrosion resistant reinforcement. The work supports integrating quantitative material measurements, including repeated core sampling, non-destructive testing such as resonance frequency analysis, and chloride content profiling, into a single evidence-based assessment system. In addition, combining these material measurements with localized environmental information, regional freeze thaw activity, chloride exposure from deicing operations, and wetness duration allows a more complete assessment of deterioration risk than visual inspections alone.

Figure 1.

Sample preparation a) Measuring of the air entrainer admixture b) Concrete mixer c) Casting of Concrete Sample.

Figure 1.

Sample preparation a) Measuring of the air entrainer admixture b) Concrete mixer c) Casting of Concrete Sample.

Figure 2.

Conditioning samples a) Wet dry shelving b) Environmental chamber c) Samples in freeze thaw chamber.

Figure 2.

Conditioning samples a) Wet dry shelving b) Environmental chamber c) Samples in freeze thaw chamber.

Figure 3.

Bridge core samples a) bagged bridge core from DelDOT b) bridge cores before c) after capping d) Humboldt compression machine.

Figure 3.

Bridge core samples a) bagged bridge core from DelDOT b) bridge cores before c) after capping d) Humboldt compression machine.

Figure 4.

Resonance frequency testing: (a) experimental setup with concrete cylinder, accelerometer, and data acquisition system, (b) schematic diagram for longitudinal mode testing (After [

26]).

Figure 4.

Resonance frequency testing: (a) experimental setup with concrete cylinder, accelerometer, and data acquisition system, (b) schematic diagram for longitudinal mode testing (After [

26]).

Figure 5.

Broken sample after compression testing b) Bagged sample after compression testing.

Figure 5.

Broken sample after compression testing b) Bagged sample after compression testing.

Figure 6.

Humboldt Compressometer /Extensometer.

Figure 6.

Humboldt Compressometer /Extensometer.

Figure 7.

Resistivity test a) Rock crusher crushing concrete powder b) Weighing concrete powder c) Handheld salinity meter.

Figure 7.

Resistivity test a) Rock crusher crushing concrete powder b) Weighing concrete powder c) Handheld salinity meter.

Figure 8.

Wet-Dry Resonance Frequency Cycling – a) 0%, b) 3%, and c) 15%.

Figure 8.

Wet-Dry Resonance Frequency Cycling – a) 0%, b) 3%, and c) 15%.

Figure 9.

Freeze-Thaw Resonance Frequency Cycling – a) 0%, b) 3%, and c) 15%.

Figure 9.

Freeze-Thaw Resonance Frequency Cycling – a) 0%, b) 3%, and c) 15%.

Figure 10.

Control Resonance Frequency Cycling.

Figure 10.

Control Resonance Frequency Cycling.

Figure 11.

Compressive Strength Results – a) Wet-Dry Cycling, b) Freeze-Thaw Cycling, and c) Control.

Figure 11.

Compressive Strength Results – a) Wet-Dry Cycling, b) Freeze-Thaw Cycling, and c) Control.

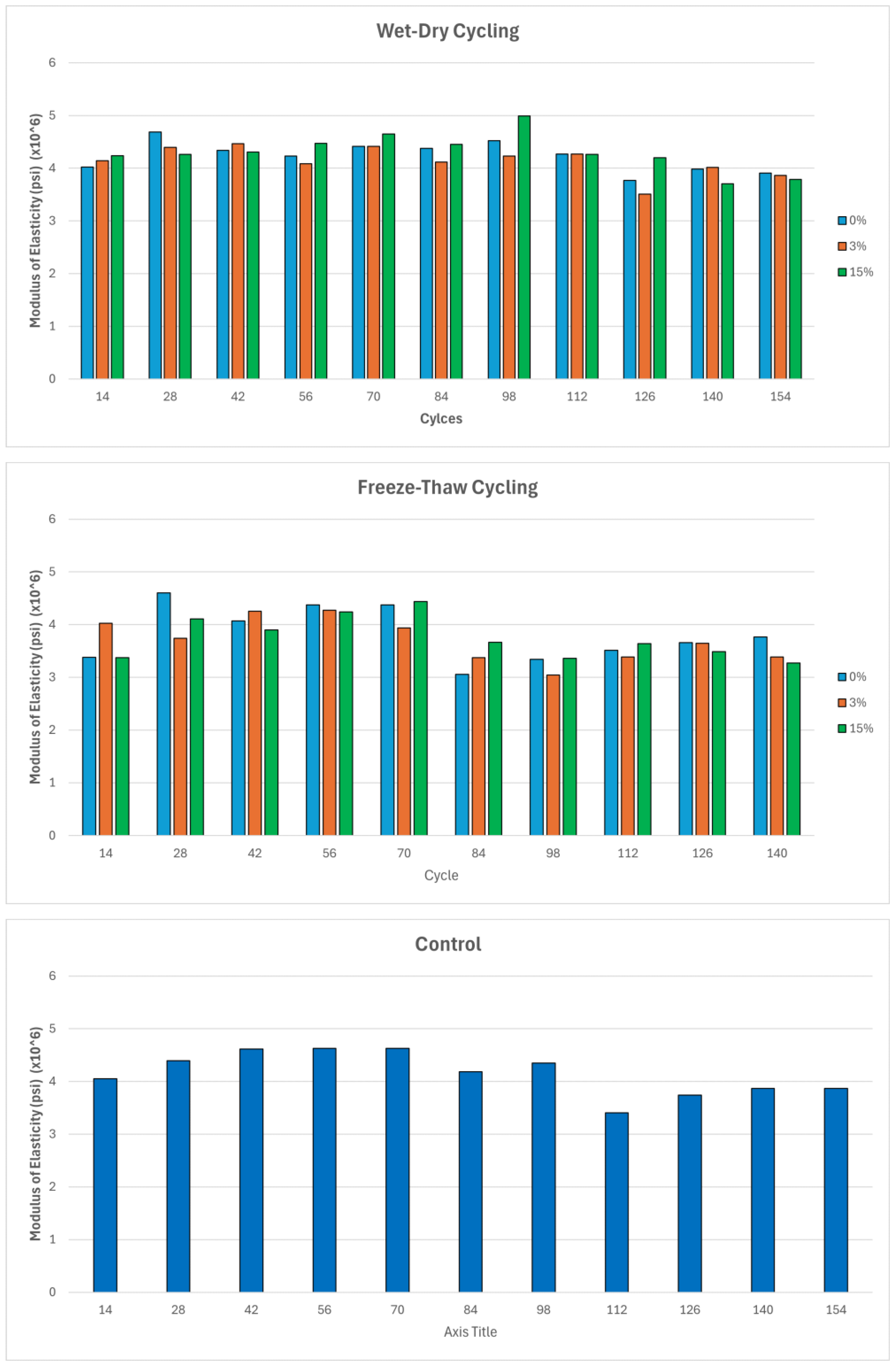

Figure 12.

Modulus of Elasticity Results – a) Wet-Dry Cycling, b) Freeze-Thaw Cycling, and c) Control.

Figure 12.

Modulus of Elasticity Results – a) Wet-Dry Cycling, b) Freeze-Thaw Cycling, and c) Control.

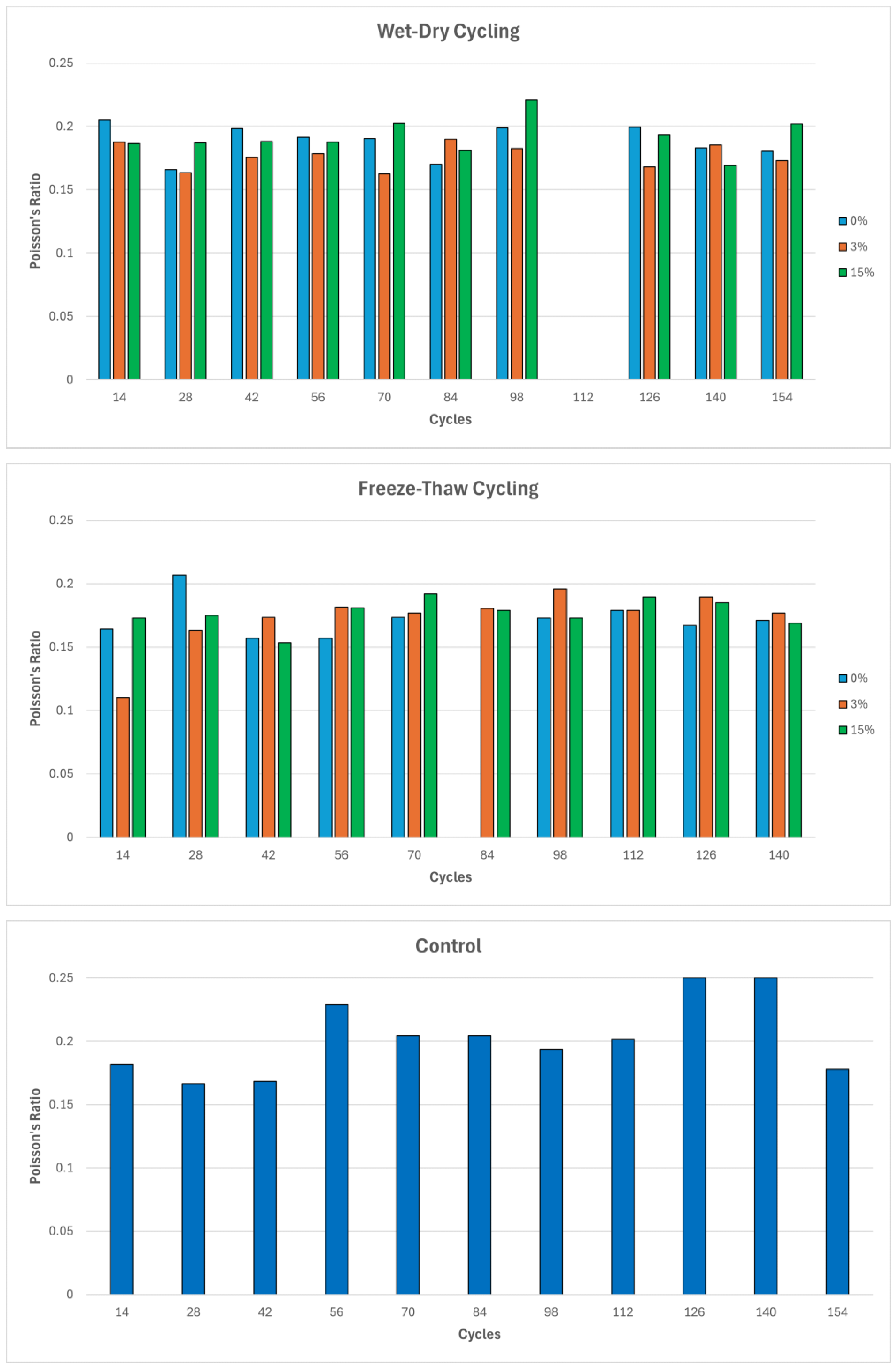

Figure 13.

Poisson's Ratio Results – a) Wet-Dry Cycling, b) Freeze-Thaw Cycling, and c) Control.

Figure 13.

Poisson's Ratio Results – a) Wet-Dry Cycling, b) Freeze-Thaw Cycling, and c) Control.

Figure 14.

Chloride Content Results – a) Wet-Dry Cycling, b) Freeze-Thaw Cycling, and c) Control.

Figure 14.

Chloride Content Results – a) Wet-Dry Cycling, b) Freeze-Thaw Cycling, and c) Control.

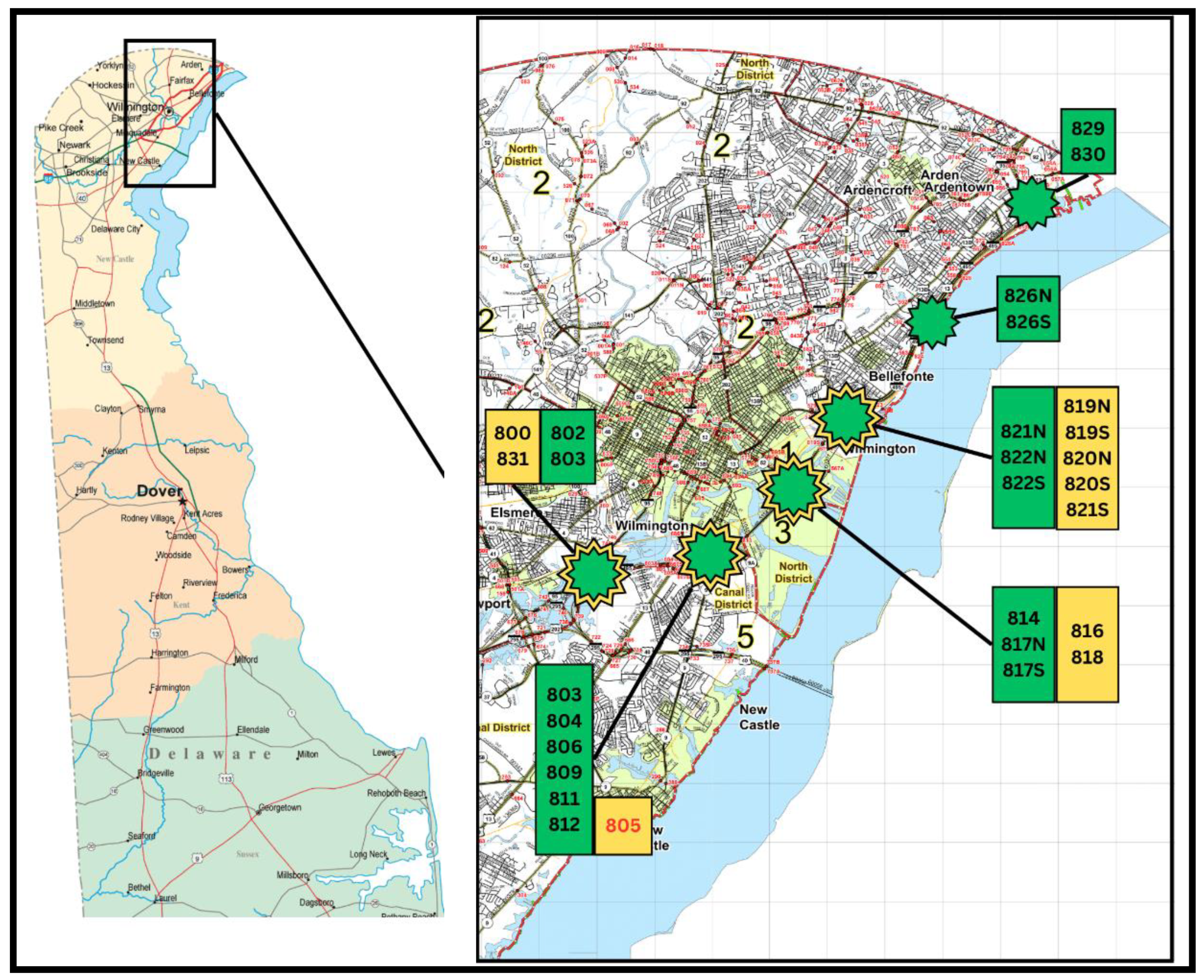

Figure 15.

I-495 Viaduct Bridge Locations.

Figure 15.

I-495 Viaduct Bridge Locations.

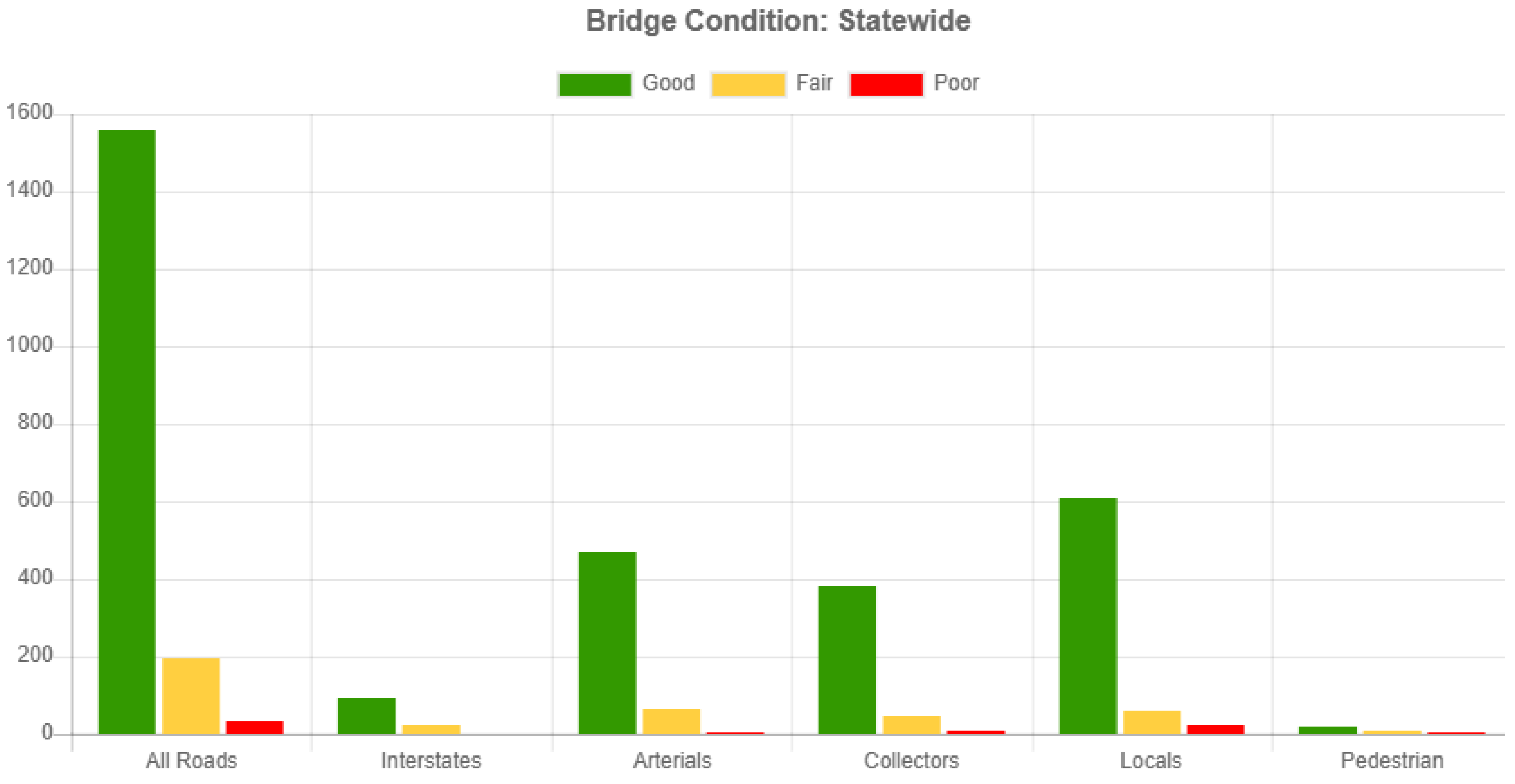

Figure 16.

DelDOT Bridge Condition Dashboard.

Figure 16.

DelDOT Bridge Condition Dashboard.

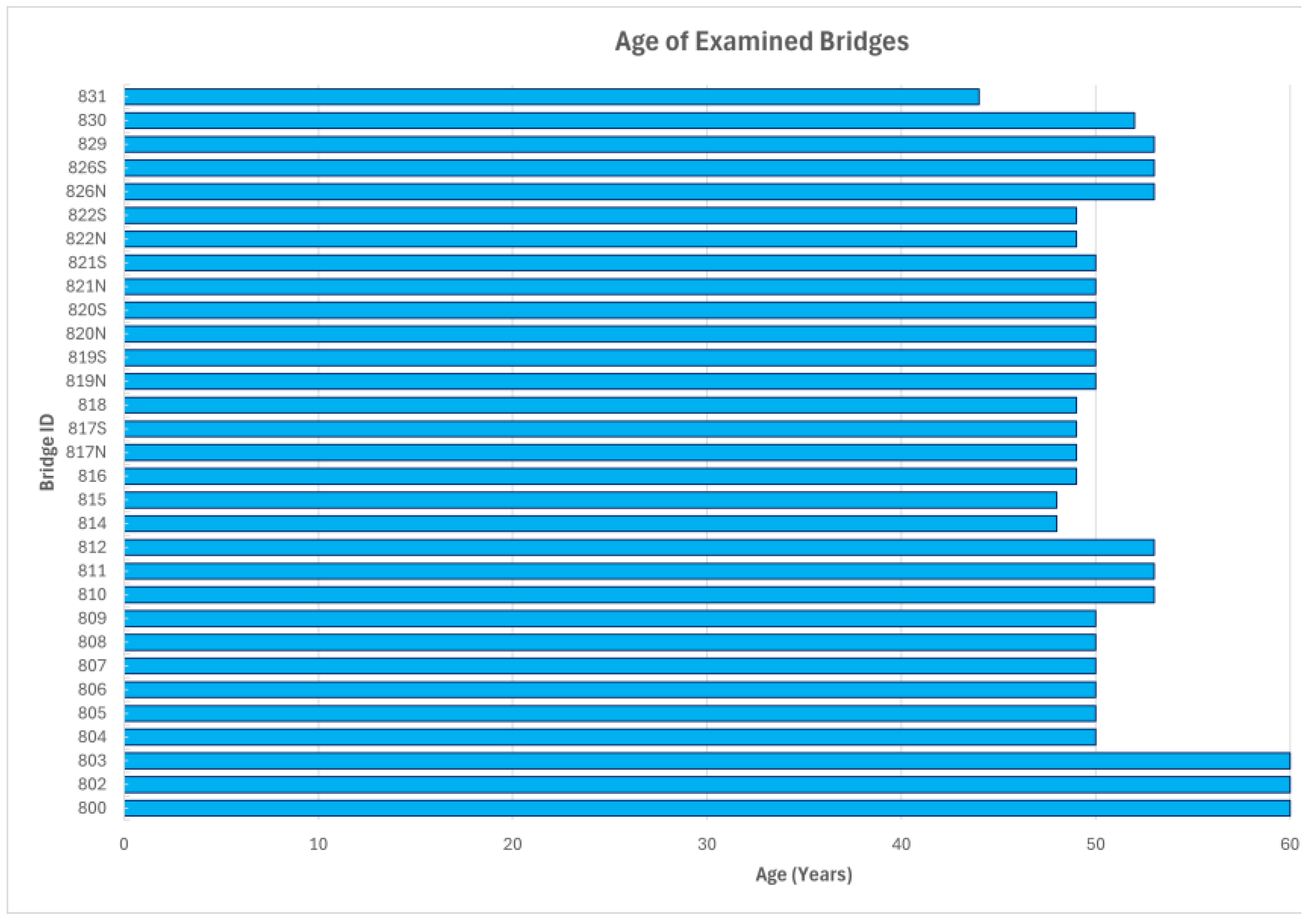

Figure 17.

Age of Bridges Examined.

Figure 17.

Age of Bridges Examined.

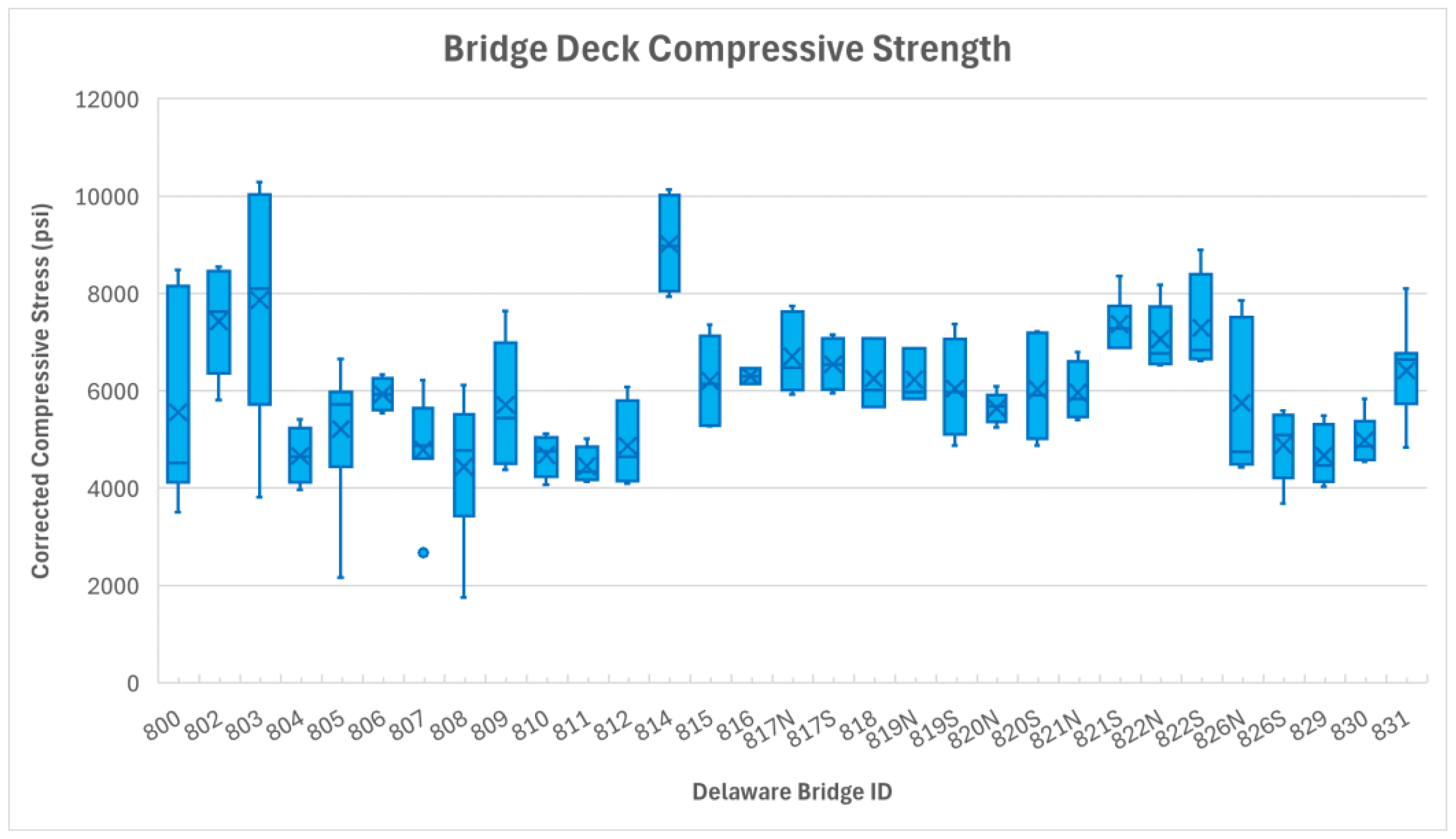

Figure 18.

Bridge Deck Core Compressive Strength.

Figure 18.

Bridge Deck Core Compressive Strength.

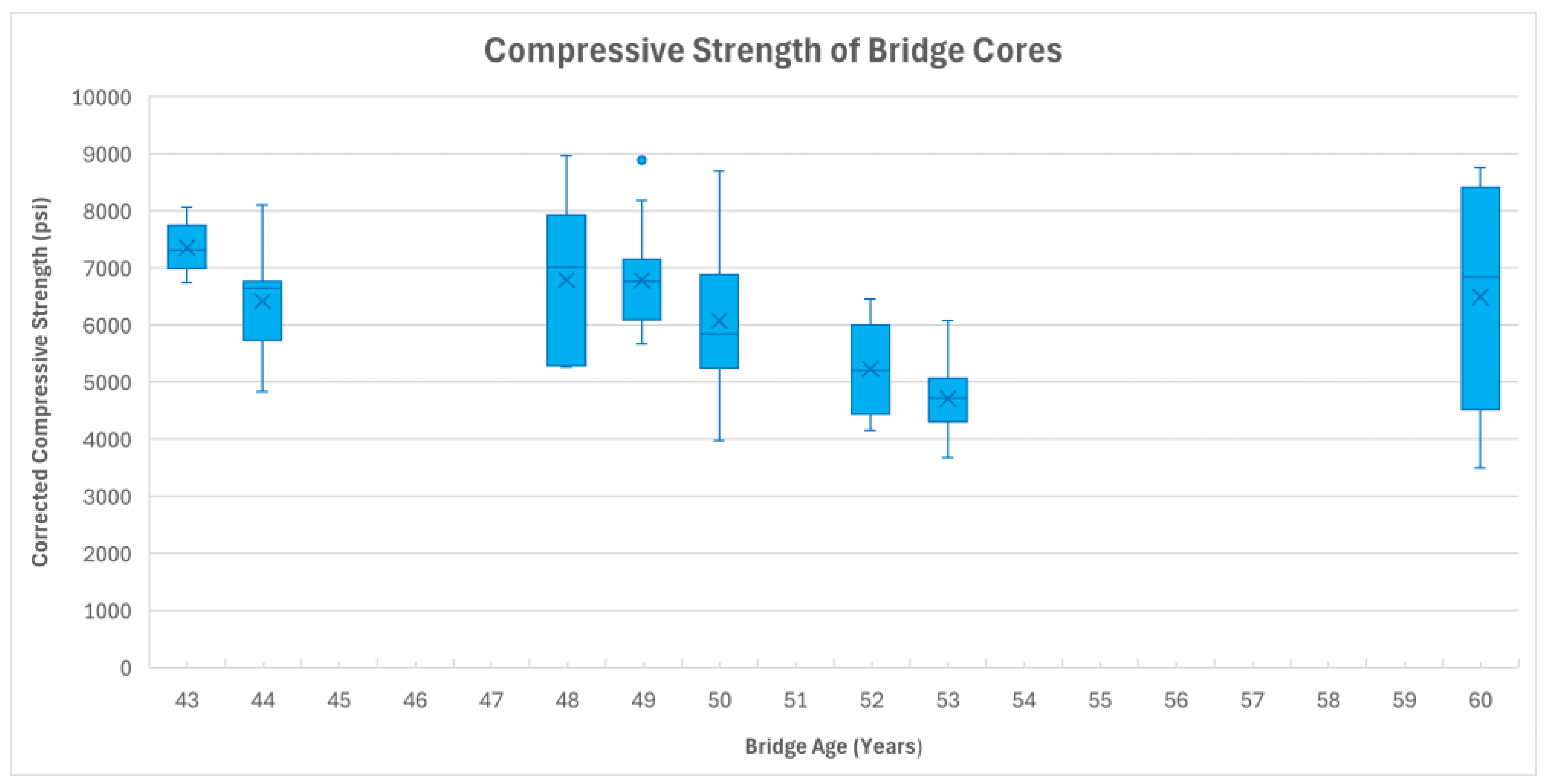

Figure 19.

Compressive Strength Breakdown by Age.

Figure 19.

Compressive Strength Breakdown by Age.

Figure 20.

Chloride Content Breakdown by Age.

Figure 20.

Chloride Content Breakdown by Age.

Figure 21.

Predicted Versus Counted Freeze Thaw Cycles.

Figure 21.

Predicted Versus Counted Freeze Thaw Cycles.

Figure 22.

92 Years of NOAA Weather Data for Wilmington, DE.

Figure 22.

92 Years of NOAA Weather Data for Wilmington, DE.

Figure 23.

Number of Snowfall Days per Year.

Figure 23.

Number of Snowfall Days per Year.

Figure 24.

Average Resonance Frequency of Lab Samples.

Figure 24.

Average Resonance Frequency of Lab Samples.

Figure 25.

Linear Trendline of Lab Samples.

Figure 25.

Linear Trendline of Lab Samples.

Figure 26.

Compressive Trends of Experimental Samples - a) Wet-Dry Cycling, b) Freeze-Thaw Cycling, and c) Control.

Figure 26.

Compressive Trends of Experimental Samples - a) Wet-Dry Cycling, b) Freeze-Thaw Cycling, and c) Control.

Figure 27.

Chloride Trends of Experimental Samples, a) Wet-Dry Cycling and b) Freeze-Thaw Cycling.

Figure 27.

Chloride Trends of Experimental Samples, a) Wet-Dry Cycling and b) Freeze-Thaw Cycling.

Figure 28.

Resonance Frequency and Compressive Trends Comparison - a) Wet-Dry Cycling, b) Freeze-Thaw Cycling, and c) Control.

Figure 28.

Resonance Frequency and Compressive Trends Comparison - a) Wet-Dry Cycling, b) Freeze-Thaw Cycling, and c) Control.

Figure 29.

Predictive Equations Compared Against Experimental Data.

Figure 29.

Predictive Equations Compared Against Experimental Data.

Figure 30.

Chloride Predictive Model With I-495 Bridge Core Concentrations.

Figure 30.

Chloride Predictive Model With I-495 Bridge Core Concentrations.

Figure 31.

Deterioration Envelope With I-495 Bridge Core Compressive Strengths.

Figure 31.

Deterioration Envelope With I-495 Bridge Core Compressive Strengths.

Figure 32.

Durability Index of I-495 Bridges.

Figure 32.

Durability Index of I-495 Bridges.

Table 1.

Concrete Mix Design for Historic Mix.

Table 1.

Concrete Mix Design for Historic Mix.

| Parameter |

Value |

Selection Rationale |

| Cement Specific Gravity |

3.15 |

Standard value |

| Coarse Aggregate Specific Gravity |

2.7 |

From documentation |

| Fine Agg Specific Gravity |

2.65 |

From lab testing of material |

| Coarse Agg Dry Unit Wt. (Unit) |

99.6 |

From lab testing of material |

| Coarse Agg Moisture Content (%) |

1 |

Found prior to batching |

| Fine Agg Moisture Content (%) |

1 |

Found prior to batching |

| Slump [mm.] |

127 |

Design Selection |

| Air Content (%) |

6 |

Design Selection |

| Compressive Strength [MPa] |

25 |

Design Selection |

| |

| Slump/max Aggregate |

305 |

|

| Compressive Strength w/c |

0.4 |

|

| Max Agg/Fine Mod |

0.6 |

|

| |

|

|

| Coarse Agg Volume [CBM] |

0.46 |

|

| Coarse Agg Weight [kg] |

732 |

Based on Dry Rodded Unit Weight |

| |

| Density of water [kg/m3] |

1000 |

At room temperature |

| Water Weight [kg] |

99.7 |

From w/c ratio |

| Volume of water [CBM] |

3.77 |

Calculated based on density |

| Cement Weight [kg] |

249.5 |

From w/c ratio |

| Volume of Cement [CBM] |

0.079 |

Calculated based on density |

| Volume of Coarse Agg [CBM] |

0.27 |

Calculated based on density |

| Air Volume [CBM] |

0.046 |

Calculated based on air content requirement |

| Total Volume [CBM] |

0.52 |

|

| |

| Fine Agg Volume [CBM] |

0.24 |

Calculated based on remaining volume in 1 cu. yd. |

| Fine Agg Weight [kg.] |

638.88 |

Calculated based on density |

| |

| |

|

|

| Stockpile [CBM] |

[kg/CBM] |

[kg/CBM] |

| Fine Agg Batch Weight [kg] |

645.27 |

60.53 |

| Coarse Agg Batch Weight [kg] |

739.2 |

69.35 |

| Cement Batch Weight [kg] |

249.5 |

23.4 |

| Water Batch Weight [kg] |

101.7 |

9.54 |

| Total Batch Weight [kg] |

1735.65 |

162.82 |