1. Introduction

The Architecture, Engineering, and Construction sector currently faces a dichotomy: the urgent need for integrated project delivery versus the reality of deep technological isolation [

1]. This struggle is rooted in the widespread use of proprietary, specialised tools—such as CAD, FEM, and BIM —that operate on fixed procedural logic. While this fragmentation is problematic, it is sustained by the industry’s historical imperative for deterministic methods [

2], which provide the verifiable outcomes necessary for safety, regulatory compliance, and liability management [

3]. These factors converge to establish a foundational definition of our current toolkit: deterministic engineering software is inherently characterised by its reliance on predefined, immutable logic.

Unfortunately, this rigid characterisation creates operational friction. Because these systems force information to flow in a linear, sequential manner [

4], they lack the capacity for autonomous adaptation; consequently, any deviation or need for complex data interpretation necessitates significant, often manual, expert intervention [

3,

5]. Reliance on customised integration for specialised tools creates a brittle architecture, where complex logic demands high maintenance whenever systems change. Recognising this systemic fragility necessitates a fundamental evolution in traditional methodology. Therefore, the essential strategy requires orchestrating a cohesive, automated ecosystem that facilitates intelligent reasoning across core engineering platforms while strictly maintaining a ‘Human-in-the-Loop’ to guarantee process fidelity. This approach effectively eliminates the bottlenecks that currently delay civil engineering projects, establishing a robust foundation for advanced computational workflows.

To operationalise this cohesive link and transcend the limitations of linear workflows, the discipline must look beyond conventional tools. Consequently, the application of computational intelligence within Civil Engineering requires a rigorous distinction between conventional Machine Learning (ML) methodologies and the emerging paradigm of Agentic Artificial Intelligence (AI) [

6,

7]. This distinction characterises the autonomous agent not merely as a passive predictive model, but as a dynamic system interacting within its digital environment, capable of sensing conditions and executing goal-driven actions to influence specific outcomes. When this goal-oriented definition acts in concert with the advanced reasoning of foundational generative AI, it will enable these systems to operate with genuine autonomy, executing complex, multi-step tasks with proactive flexibility rather than merely responding to user prompts [

6].

However, the deployment of the proposed Agentic AI necessitates a “Human-in-the-loop” paradigm to bridge computational autonomy with professional accountability. By synthesising the capabilities for self-direction and reflection inherent in Large Language Models (LLMs) [

8], Agentic AI assumes the role of “Central Coordinator” within Multi-Agent Systems (MAS) frameworks [

9] ; yet, this agentic coordination is most effective when anchored by human oversight to ensure technical validity and ethical alignment. This symbiotic structure enables autonomous agents to augment intricate workflows and mitigating risk [

10], while preserving the engineer’s role as the ultimate arbiter. While this operational independence introduces the acute challenge of establishing clear safety criteria for agent failures [

11], the integration of Human-in-the-loop protocols confirms that Agentic AI constitutes the fundamental shift: moving the field from systems focused solely on prediction towards those capable of supervised, goal-directed management. (International Telecommunication Union 2025). While Large Language Models offer exceptional capabilities in natural language inference, their inherent reliance on static training data—characterised by fixed cut-off dates—often results in ‘hallucinations’ when processing fragmented or detailed queries. These constraints render unaugmented models insufficient for high-stakes engineering applications [

12]. To address this fundamental limitation, the field has adopted Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), defined as an integrative framework that couples the generative LLM with an efficient information retrieval system [

12,

13]. This architecture is specifically designed to augment the LLM’s internal knowledge base with external, current, and domain-specific data, enabling effective performance where pre-trained data is typically incomplete [

12]. By integrating authoritative documents from domain-specific repositories—such as seismic design codes [

14,

15,

16], historical ground motion records [

17], and experimental hysteresis data [

18]—before generating a response, the system effectively mitigates the critical risk of hallucinations. This synthesis of data augmentation and error mitigation underpins the current architectural transition toward

Agentic RAG systems; this shift reflects the reality that earthquake engineering workflows, such as performance-based assessments and non-linear analysis, require autonomous agents capable of complex planning and environmental interaction, extending far beyond simple text generation [

8]. However, given the catastrophic consequences of structural failure in seismically active regions, this autonomy must be governed by a ‘Human-in-the-loop’ protocol. In this paradigm, the structural engineer serves as the definitive validation node, anchoring the agent’s probabilistic reasoning to deterministic seismic provisions and ethical liability. Consequently, the most significant contribution of RAG in this context is its mechanism for factual grounding: by compelling the LLM to derive its outputs directly from specific regulatory clauses and validated spectral data, the framework drastically improves the accuracy and reliability of technical judgements compared to unaugmented generative models.

(Ahmad 2025)Despite the remarkable advances in AI, the core challenge of LLMs in engineering remains a lack of inherent physics-based knowledge, leading to what is termed “Recursive Hallucination” and “Structural Distortion” [

19]. Essentially, LLMs can generate plausible-looking, yet structurally unsound, designs. To address this gap, a fundamental methodological reorganisation was proposed in late 2024 with the introduction of the Model Context Protocol (MCP), an open standard designed to harmonise the interface between LLMs and external, domain-specific data sources [

20]. This protocol functions as a universal “socket”—analogous to a USB-C port for AI—enabling autonomous agents to dynamically discover and execute workflows, read resources, and utilise tools across disparate computational systems [

21].

It is important to understand that the literature defines MCP not as a proprietary application, but as a communication protocol that standardises the interaction between an “AI Host” and the external world. This architecture is structurally underpinned by a client-host-server model, facilitating a standardised information exchange via JSON-RPC 2.0 messages [

22]. This tripartite structure is fundamentally critical, as it effectively decouples the abstract reasoning capabilities of the AI from the domain-specific, immutable logic of engineering tools.

A recent study, supported by a dedicated dataset for validation, successfully demonstrated that MCP is a feasible and robust method of connection between an LLM and an external engineering API, specifically OPENSEESPY, enabling complex structural analysis via a structured CIDI prompt [

23,

24]. Therefore, the MCP represents a foundational structure and systemic definition of Civil Engineering applications, moving beyond mere generative capacity to verifiable, physics-informed execution.

While the individual utility of these technologies is recognised, the current state-of-the-art—as synthesised in recent reviews by Elsisi (2025) [

25]—remains constrained by a ‘linear pipeline’ architecture. In this prevailing paradigm, AI functions primarily as a ‘Copilot’ or task-specific assistant, where the Model Context Protocol is utilised largely as a connectivity interface to facilitate conversation. Crucially, these existing frameworks rely heavily on post-hoc ‘Human-in-the-Loop’ validation to mitigate inevitable hallucinations. However, it is argued that relying on human oversight to police stochastic errors is insufficient for the strict liability requirements of seismic infrastructure.

To transcend these limitations, this paper proposes a unified orchestration framework that synthesises three critical technologies into a cohesive cognitive architecture. We argue that Agentic AI must operationalise the predictive and generative capabilities of LLMs, elevating them to a “Central Coordinator” role that provides intent and strategic planning. Simultaneously, Retrieval-Augmented Generation must be integrated to enforce strict regulatory grounding, mitigating hallucinations. Crucially, we introduce the Model Context Protocol as the foundational “USB-C for AI”—a standardised interface that decouples abstract reasoning from the immutable logic of engineering tools. By harmonising these elements, the framework moves the discipline from static, linear workflows to dynamic, physics-informed execution, effectively closing the validation gap required for autonomous civil infrastructure.

2. Materials and Methods

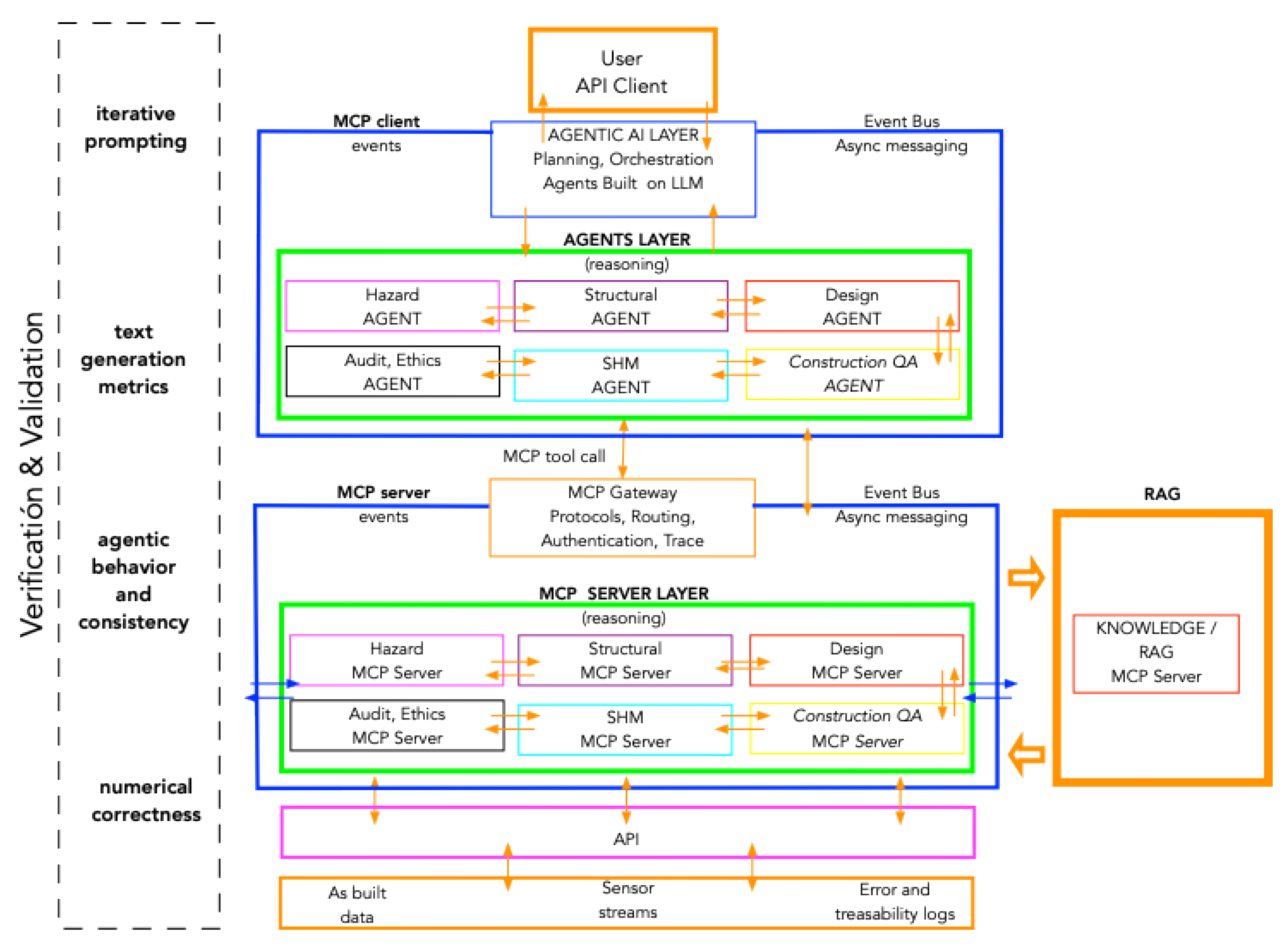

The system integrates seven layers organised according to the Model Context Protocol (

Figure 1). At the top, the User & Interface Layer captures engineering intent and delivers results and explanations. The Agentic AI Layer interprets user goals (given in natural language, simplifying the user-machine interactions) and orchestrates multi-step workflows across domain agents. The Agents Layer, comprising specialised MCP clients (Hazard, Structural, Design, Quality Assurance, SHM, and Audit & Ethics Agents), translates high-level plans into structured tool calls and interprets computational responses. Communication with deterministic numerical engines is mediated by the MCP Gateway Layer, which ensures schema consistency, authentication, and routing, and by the Event Bus Layer, which broadcasts asynchronous events enabling reactive and concurrent operations. The MCP Server Layer contains the deterministic computational engines responsible for hazard analysis, structural simulation, code-compliant design, construction quality verification, structural health monitoring, and audit functions. At the bottom, the External Data Input Layer ingests as-built geometry, sensor streams, and traceability logs, supporting continuous life-cycle updates to models and decisions.

2.1. The Model Context Protocol Paradigm

The proposed framework adopts the Model Context Protocol to address the fundamental incompatibility between stochastic Large Language Model reasoning and the rigorous determinism required in seismic engineering. By enforcing a standardised client–server paradigm, the architecture strictly segregates cognitive planning from numerical execution, ensuring that the system functions as a reliable engineering tool rather than an uncontrolled generative model.

2.1.1. Client–Server Dichotomy

The architecture is defined by a strict functional separation between two layers:

The Client (Reasoning Layer): The “Agents Layer” operates as the MCP client, comprising domain-specific agents (e.g., Hazard, Structural, Design) driven by LLM reasoning (

Figure 1). These agents function as the system’s orchestrators and are the sole initiators of requests. They utilise high-level cognition to decompose complex objectives and determine

when to execute specific tasks—such as deciding to run a spectral analysis—without performing the calculations themselves.

The Server (Computational Layer): The “MCP Server Layer” consists of stateless, deterministic engines that expose validated engineering tools (e.g., run_response_spectrum, check_aci318). These servers lack agency and reasoning capabilities; they strictly execute algorithms upon request and return structured, machine-interpretable outputs.

2.1.2. Safety and Determinism

This separation provides a robust mechanism for preventing “hallucinations” in safety-critical workflows. By routing all computations through the MCP Gateway to deterministic servers, the framework ensures that every structural demand, capacity check, or safety decision originates exclusively from validated physics-based algorithms. Consequently, the agents reason about the engineering process using textual logic, but the numerical ground truth is never generated by the LLM, thereby guaranteeing traceability and reproducibility.

2.2. Multi-Layer Architectural Topology

The proposed framework (

Figure 1) establishes a hierarchical topology comprising seven distinct strata, rigorously organised under the Model Context Protocol to decouple stochastic LLM reasoning from deterministic engineering verification.

At the summit, the User & Interface Layer (Layer 1: Human-in-the-Loop Oversight) defines the regulatory boundary, capturing high-level engineering intent whilst serving as the definitive approval gate for design alternatives and explainable outputs. Directly beneath, the Agentic AI Layer (Layer 2: Executive Planning & Orchestration) acts as the system’s cognitive core. This layer decomposes complex, multi-stage workflows—spanning hazard assessment to structural health monitoring—managing cross-domain dependencies, based on AI reasoning, without executing direct computations.

Operational logic is delegated to the Agents Layer (Layer 3: Domain-Specific MCP Clients). Comprising specialised agents for Hazard, Structural Analysis, Design, Quality Assurance (QA), SHM, and Audit, this layer translates the orchestrator’s natural language plans into structured MCP tool schemas. To ensure protocol integrity, the MCP Gateway (Layer 4: Secure Middleware & Routing) mediates all traffic between clients and servers. It enforces strict authentication and schema validation, guaranteeing that stochastic agent requests adhere to the rigid input requirements of the numerical engines.

Simultaneously, the Event Bus (Layer 5: Asynchronous Reactive Backbone) employs a publish-subscribe model to broadcast system-wide triggers—such as hazard.cms.ready or qa.deviation.alert—enabling real-time cross-domain reactivity. The computational foundation resides in the MCP Server Layer (Layer 6: Deterministic Computational Engines). This suite executes validated physics-based algorithms (e.g., PSHA, FEM, Code Checks) and strictly excludes hallucination. Crucially, this layer integrates a Knowledge/RAG Server, which retrieves contextual regulatory data (e.g., ACI 318-25 clauses) to support decision-making without altering numerical results. Finally, the External Data Input Layer (Layer 7: Lifecycle Data Ingestion) anchors the digital twin in physical reality by feeding as-built BIM models, sensor streams, and construction logs into the upstream servers.

2.3. Integration of Controlled Retrieval-Augmented Generation

The framework integrates RAG technology by encapsulating it within a dedicated Knowledge MCP Server, strictly adhering to the client–server architecture defined by the Model Context Protocol. Rather than functioning as an unchecked generative layer, this server is implemented as a deterministic endpoint that exposes specific tools—such as search_codes, search_qa_guidelines, and search_projects—which agents invoke via the MCP Gateway.

Technically, this integration relies on the MCP Gateway to enforce schema validation on all retrieval requests, ensuring that queries for regulatory clauses (e.g., ACI 318, ASCE 7) or historical project data are structured and secure. Upon invocation, the Knowledge Server queries a vectorised knowledge corpus and returns structured JSON containing ranked passages and source metadata, explicitly avoiding free-form conversational outputs.

This architecture establishes a rigorous Contextual vs. Computational Separation. The RAG-driven Knowledge Server is solely responsible for providing textual justification and interpretive context, while physics-based computations—such as Finite Element Method (FEM) and Probabilistic Seismic Hazard Analysis (PSHA)—are executed by isolated, stateless MCP servers. This separation prevents LLM hallucinations from corrupting numerical workflows while ensuring that every engineering decision is traceable to a specific, immutable document within the vector store.

2.4. System Dynamics and Lifecycle Integration

The proposed framework (

Figure 1) orchestrates system dynamics through a hybrid execution model that harmonises deterministic control with reactive agility, ensuring robust performance across the engineering lifecycle.

2.4.1. Synchronous Execution

The core operational mechanism relies on a standard synchronous request-response cycle managed by the MCP Gateway. In this phase, domain agents (MCP clients) initiate tool calls—such as struct-server.run_response_spectrum or design-server.check_aci318—which the Gateway validates for schema consistency before routing to the appropriate deterministic MCP server. This strict mediation ensures that all safety-critical calculations remain reproducible, authorised, and strictly isolated from potential reasoning errors inherent in the LLM layer.

2.4.2. Asynchronous Reactivity

To accommodate dynamic inputs, the architecture employs an Event Bus Layer that establishes event-driven loops distinct from the linear request cycle. This mechanism broadcasts asynchronous state changes, such as qa.deviation.alert during construction or shm.alert.damage during operation, allowing the Agentic AI to react concurrently to emerging hazards without blocking ongoing computations.

2.4.3. Lifecycle Continuity

The convergence of deterministic tool execution and reactive, event-driven monitoring unifies the project lifecycle through a shared digital thread. By ingesting as-built geometry, sensor streams, and traceability logs via the External Data Input Layer, the system links initial design assumptions with real-world Quality Assurance verification and long-term Structural Health Monitoring. This integration transforms static engineering models into a continuous, closed-loop ecosystem capable of dynamically updating assessments in response to physical degradation or seismic events.

2.5. Systemic Mitigation of Stochastic Variance in Autonomous Engineering Agents

The integration of a dedicated Validation and Verification layer is not merely an architectural enhancement but a fundamental imperative for the safe deployment of Agentic AI in structural engineering. While the proposed architecture leverages the reasoning power of LLMs, it is required to recognised that these components are inherently probabilistic. Unlike the deterministic solvers in the MCP Server Layer—which provide mathematically guaranteed results for hazard curves and spectral response—agentic outputs are susceptible to “hallucinations,” omissions, and misalignment with physics-based ground truths.

Therefore, the Validation and Verification layer is essential as an independent “meta-evaluator” to bridge this reliability gap. By systematically benchmarking agentic explanations against deterministic data using established NLP metrics and “LLM-as-a-Judge” paradigms, it can be ensured textual accuracy. Furthermore, this layer is critical for validating agentic behaviour itself, verifying that autonomous agents strictly adhere to engineering workflows and safety constraints. Consequently, to transform stochastic AI reasoning into a robust professional tool, the Validation layer provides the necessary continuous monitoring and regression testing required to mitigate risk and ensure that the rigour of structural safety standards is never compromised by the fluidity of generative models.

4. Conclusion

The integration of the Model Context Protocol constitutes the critical enabler for the proposed agentic AI architecture in structural seismic engineering. Given that seismic design mandates absolute determinism, traceability, and strict regulatory compliance—standards that traditional LLMs cannot independently guarantee—MCP provides the essential secure, standardised client–server foundation. By isolating domain-specific computations, such as probabilistic seismic hazard analysis and nonlinear dynamic assessments, within validated MCP servers, the framework strictly segregates reasoning from calculation. This architectural separation effectively precludes LLM hallucination from compromising numerical workflows, ensuring that all safety decisions remain grounded in deterministic algorithms. Simultaneously, MCP empowers the agentic layer to operate safely within an event-driven, closed-loop ecosystem, where the MCP Gateway and Event Bus manage asynchronous updates ranging from hazard readiness to structural health monitoring. Consequently, MCP transcends the role of an auxiliary component to function as the foundational mechanism that transforms agentic AI from a mere conversational interface into a trustworthy, auditable, and lifecycle-aware computational system indispensable for safety-critical infrastructure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Carlos Avila; Formal analysis, Carlos Avila and David Rivera; Investigation, Carlos Avila and David Rivera; Methodology, Carlos Avila; Supervision, Carlos Avila; Writing – original draft, David Rivera; Writing – review & editing, Carlos Avila and David Rivera.

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding”.

Data Availability Statement

“No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.”.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”.