1. Introduction

Floating offshore wind energy has become a reliable way to exploit the potential of the wind resource in deep waters, where more constant and intense winds make it a powerful asset. However, predicting and controlling the dynamic behavior of floating platforms issues an important challenge for marine engineering due to the combined action of waves, sea currents and wind. In this context, heave plates play a main role in improving the platform’s stability thanks to their damping effects both in heave and pitch [

1].

Bibliography shows many studies aimed to analyze and improve the design of heave plates in order to optimize their behavior and therefore obtain a better energetic efficiency [

2]. To do so, numerical methods such as Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) stand as vital tools that enable the study of the hydrodynamic impact of heave plates, aiming to predict their damping and added mass coefficients [

3,

4] . Nevertheless, computational models always need to be validated with experimental studies [

5].

In recent years, heave plate design has significantly evolved. From being employed firstly in oil platforms to reduce their heave response due to waves [

6] to their application in FOWTFs due to their ability to improve the dynamic stability and minimize non-desired oscillations [

7].

In this sense, recent configurations include circular, rectangular and perforated heave plates. In [

8] a combined experimental and numerical study proved that the size and shape of heave plates have a strong influence in the dynamic response of the platform. For example, in [

9] and [

10] it is shown that heave plates are crucial for the stability of spar platforms, whereas in [

11] a multi-plate design is achieved, which not only dampens the movement, but also generates energy. On the other hand, in [

2] the importance of the shape of the plates is discussed, and in [

12] it is concluded that the diameter of the plate has a direct impact in its damping ability.

In all studies, the ability of heave plates to improve the heave damping of floating structures is demonstrated and emphasized. This is achieved thanks to an improvement in the vortex-shedding process and a modification of the hydrodynamic properties of the floating body. Hydrodynamic forces are represented in their non-dimensional form via the hydrodynamic coefficients of added mass and damping, which are function of the amplitude (A) and frequency (f) of the movement [

13]. To determine these coefficients, as seen in the aforementioned studies, authors use forced oscillation tests, since they provide more simple analysis than free decay tests. These two magnitudes that rule the movement of heave plates are represented by two non-dimensional numbers: the Keulegan-Carpenter number

and the frequency parameter

, with D being the diameter of the disc and ν the kinematic viscosity of the fluid.

There are experimental studies of heave plates, such as [

14] and [

9], where the impact of wave conditions on the hydrodynamic coefficients of heave plates was studied. In [

14] it was observed that the added mass and damping can vary up to a 30\% in presence of superficial waves, so a modification in the calculation of the KC number was proposed to improve the estimation of these coefficients. Moreover, in [

9] was concluded that the influence of the position of the plate is significant when KC<0.75, but decreases when the oscillation frequency increases.

Simulation of heave plates via CFD has become of great importance in marine engineering, especially in the design and analysis of floating platforms. These simulations allow to better understand the hydrodynamic behavior of heave plates and their impact in the response of marine structures in order to improve their efficiency under wave conditions [

13]. Different simulation methods are used in this context in terms of their turbulence models, among which the Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) and Large Eddy Simulations (LES) methods are of especial importance.

The RANS method is based on averaging the Navier-Stokes equations, which allows an effective modelling of turbulent flows. In the bibliography, numerous CFD studies use this method for the study of heave plates. The study by Liu et al. [

15] is worth mentioning, since the impact of the structural design of floating semisubmersible platforms in their response under wave conditions was studied, concluding that increasing the number of floating columns in the platform translated to a reduction in the surge response. Moreover, in [

3], ANSYS Fluent was used to study the behavior of floating buoys, stating that their draft and the wave conditions have a significant influence on their potential for energy conversion. Other works such as [

16] and [

17] developed CFD models to study the damping produced by heave plates in spar platforms, observing that it was non-linear and depended on the diameter of the plate and their positioning along the column. Additionally, in [

18] and [

19], the effects of the damping caused by circular heave plates on floating platforms were studied experimentally and numerically, concluding that the increase in added mass and damping contributes to the stability of the platform. Moreover, in [

12], the effect of viscosity on the behavior of heave plates was analyzed via hydrodynamic coefficients, determining that quadratic damping models offer a better correlation with experimentation. Furthermore, in [

8], a CFD study of the flow around heave plates, along with the added mass and the damping of heave plates at different depths was carried out, concluding that the damping coefficient increases with proximity to the seabed, and has a non-linear behavior when related to the KC number.

On the other hand, LES models are used to better represent more complex fluid behavior along with more detailed turbulence phenomena. Although this method is more demanding in terms of computational cost, it allows for a more accurate representation of flows in comparison with the RANS method. In [

20], the LES method was used to analyze hydrodynamic coefficients of heave plates, validating the computational models with experimental results in a water tank. Furthermore, in [

21], this method was employed to study the impact of waves and flow interaction with floating structures equipped with heave plates, thus obtaining a better understanding of the hydrodynamic phenomena involved in these situations. Apart from these methods, potential flow has also been used to analyze heave plates, but it was shown to fall short of the experimental results, especially in cases with big amplitudes.

As shown in these previous studies, experimental results are a necessity when working with CFD models of heave plates in order to validate them, such as in [

15] and [

1]. To do so, different methodologies can be found in literature, where these elements are tested in a controlled environment. These experiments are mainly carried out in water canals and/or wave tanks via various forced oscillation and free decay tests that allow the study of the dynamic response of different geometrical configurations of heave plates even under wave conditions, such as in [

10]. Scale analysis also plays an important role in experimentation with heave plates, as can be seen in [

22,

23,

24]. In [

22], the effect of heave plates attached to spar platforms was analyzed, using 1:50 scale models and concluding that the size and location of the heave plates play an important role in the stability of the platform. In [

23] it was demonstrated that scale effects can induce errors in the upscaling of the results, and it was emphasized that viscous effects should be taken into account when experimenting. Additionally, in [

5] a Particle Image Velocimeter (PIV) was used in order to study the fluid dynamics around different scale-models of heave plates, observing similarities in vorticity and velocity patterns between different scales, thus indicating lesser scale effects in the hydrodynamic behavior. Furthermore, Medina et al. [

24] also carried out experimentation of scaled heave plates under different amplitudes and frequencies in forced oscillations and free decays, characterizing the hydrodynamic coefficients obtained and comparing them between both kinds of movements. A detailed uncertainty assessment was also carried out, and a correction to upscale the coefficients was proposed.

As previously stated, validation of the computational models is a critical step in research with CFD tools. Examples of this can be found in [

7,

17,

25], where CFD results were compared with their experimental counterparts to validate the forces and moments obtained in various models of heave plates. Moreover, in [

14], hydrodynamic coefficients were compared in forced oscillations and free decay tests, observing that CFD models tend to underestimate high-frequency coefficients. This suggests the necessity of improving numerical methods in order to better predict the real behavior of heave plates, thus being one of the main objectives of this paper. Some of the errors detected in literature when validating CFD models arise from the boundary conditions configuration, along with the meshing process and the turbulence representation, as shown in [

4], where a convergence analysis of the models is recommended, and so has been done in this paper.

The main objective of this paper is to develop a versatile enough CFD model of a heave plate that can be applied under extreme working conditions without any changes needed. The CFD technology used will be a Lattice-Boltzmann software with an LES turbulence model. The computational model should provide not only correct results in terms of added mass and damping, but also be able to correctly represent the hydrodynamic forces suffered by the heave plate. Once achieved, the model could be upscaled to simulate a complete floating platform. Results will be validated with the experimentation carried out by [

24] and in some instances compared with the ones obtained using a different CFD software.

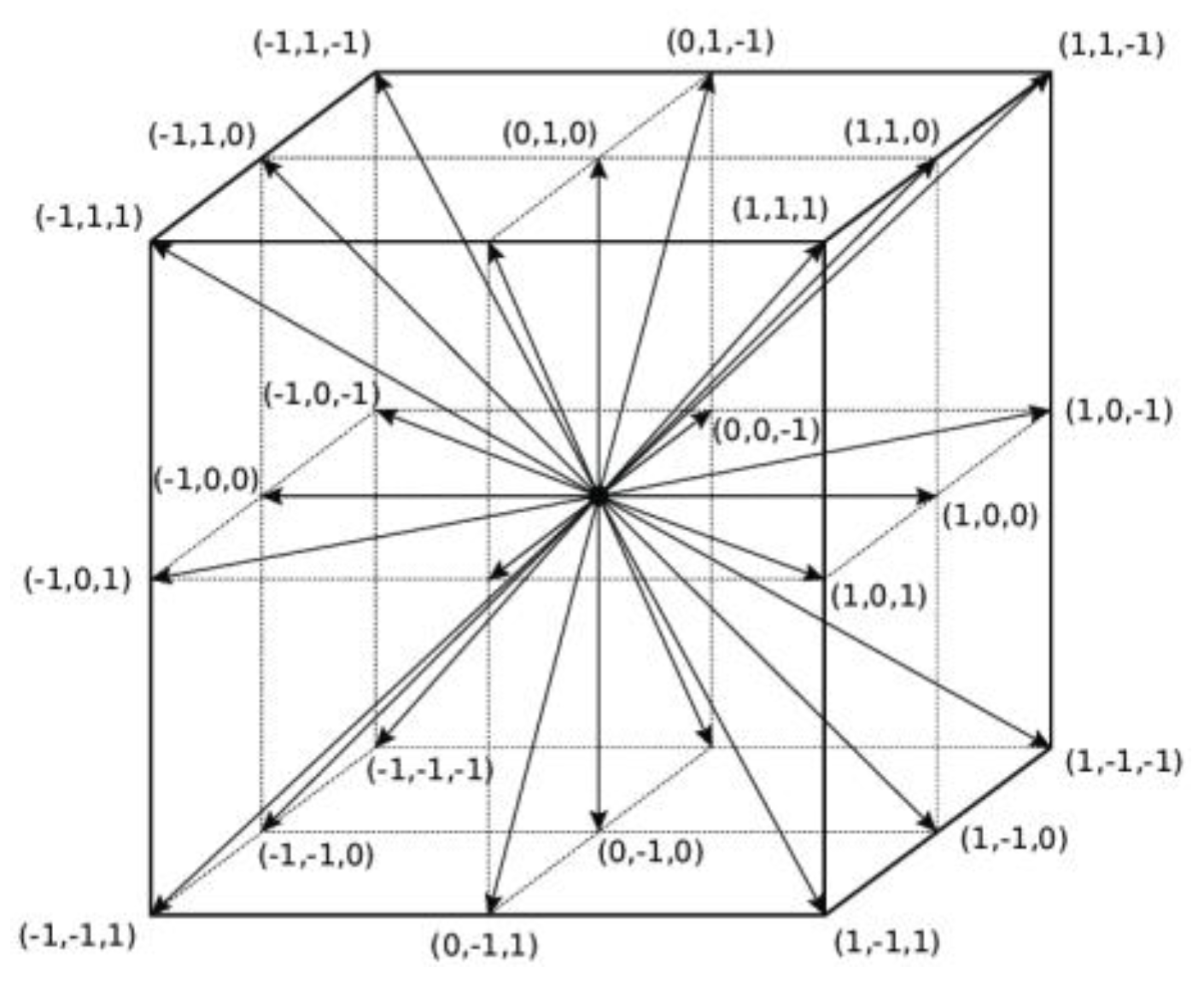

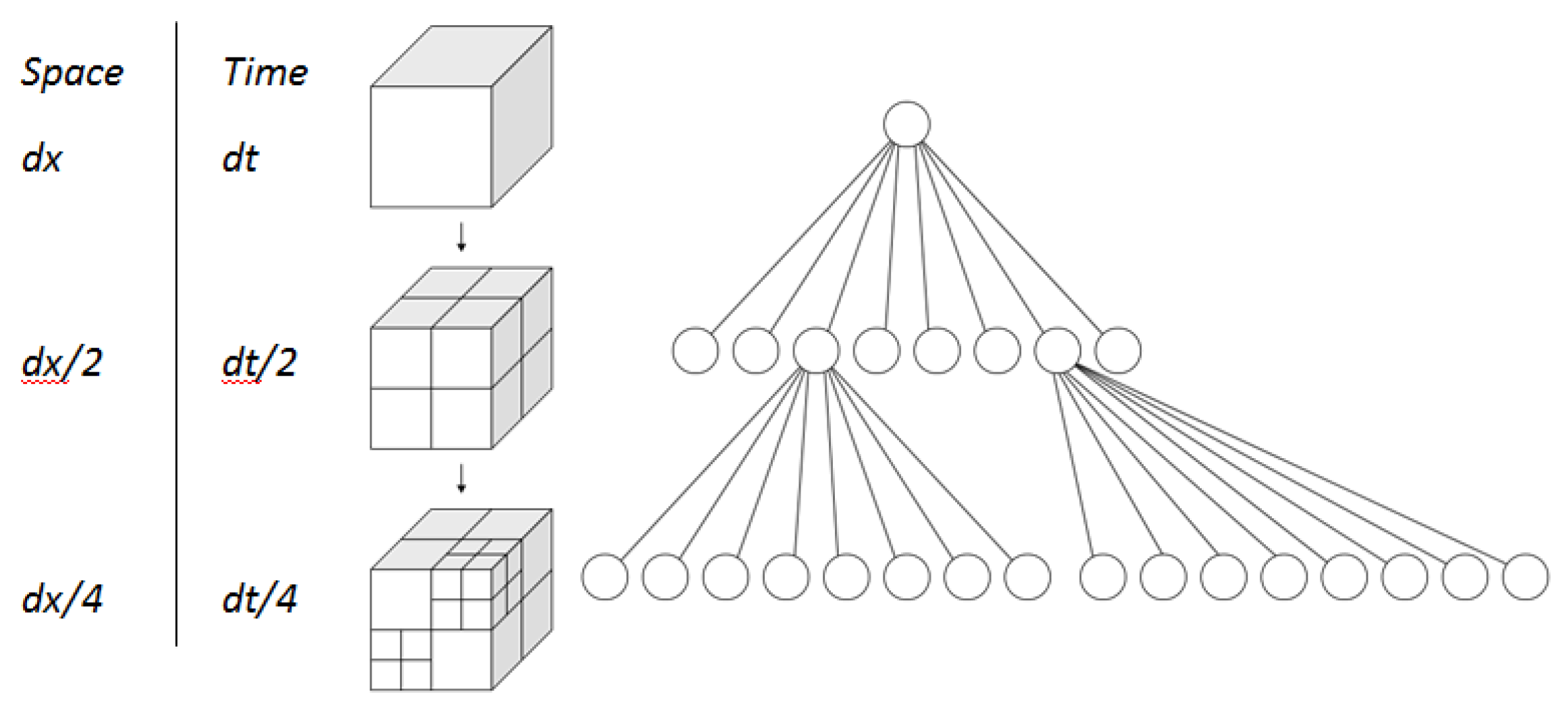

Instead of the usual finite-volume or finite differences used in the common commercial or open software, which also refer to an Eulerian approach, a Lattice-Boltzmann software has been used, which takes a Lagrangian approach. There are very few studies carried out with this technology, which generally aim for a more precise turbulence representation. In [

25], the application of LB to a multiphase flow is studied, simulating breaking waves. In [

26], different NACA hydrofoils are studied and characterized. Studies closer to the present simulate the flow around floating cylinders, such as in [

27,

28,

29,

30]. In [

27], the cylinder is coupled to a mooring system and its influence in the hydrodynamic forces is analyzed. In [

28] the cylinder is floating freely and its movement and the height evolution of the free surfaced is characterized. Alam and Cheng [

29] study the influence of the roughness of a fixed cylinder in the behavior of the flow, and [

30] introduce the interference of two cylinders -one fixed and the other oscillating- in the flow between them. Moreover, Bogner and Rüde [

31] simulate freely floating boxes and study their behavior until equilibrium is achieved.

The authors have only been able to identify one research in which the Lattice-Bolztmann method has been used to study heave plates. It was developed by Cong et al. [

32] and they used an in-house LB code to simulate and study square heave plates with different perforations. However, the maximum Reynolds number simulated was Re=411, which is low for industrial applications. They also used a Direct Numerical Simulation turbulence calculation, which is very costly in computational terms and not feasible for industrial applications. In fact, Cong et al. [

32] suggested that simulations with an LES model would be interesting. Thus, the present paper constitutes -to the authors’ knowledge- the first study of heave plates using a LB software with an LES approach and under industrial applicability, with Re numbers between 2.6x10

4 and 2.5x10

5. This also represents an opportunity to analyze the employability of LB and LES when simulating more complex geometries such as heave plates and how it fares when compared with a finite-volume software.

2. Dimensional Analysis and Scaling

The hydrodynamic model of the behaviour of a floating body in the heave direction, follows eq.(1), as stated in McCormick [

33]:

Where a

wz represents the added mass, b

rz and b

vz represent the radiation, viscous and damping coefficients respectively and b

pz the power take-off coefficient. A

wp is the waterplane area when the body is at rest and N and k

s are the number of mooring lines attached to the body and their elastic coefficient. For this work, assuming forced oscillations with no mooring system, the model has been reduced and compacted to eq. (2):

Where A33 is the added mass, B33 the equivalent linear damping, C33 the static restoring in heave motion and Fext the actuator force. This is the notation that will be used from now on.

Since the heave plate will only be performing forced oscillations, the added mass and damping can be defined as in [

6] after undergoing a harmonic analysis, extracting the phase and counterphase components of the hydrodynamic force, eqs.(3) and (4):

Finally, to non-dimensionalise these coefficients along with the hydrodynamic forces measured, the same method as Medina et al.[

24] has been used and is presented in eqs.(5-7):

Where A

33,th is the theoretical added mass, which follows the correction proposed by Tao et al. [

34], as presented in eq.(8), where

with D

d and D

c being the diameters of the disc and column respectively. The term (

) gives the maximum velocity of the oscillatory movement and S

ref is the area of the disc perpendicular to the movement.

The heave plate used is based on the one from the HiPRWind project. Since the experimentation was already performed by Medina et al.[

24], using a 1:20 scaled model.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Convergence and Symmetry Study

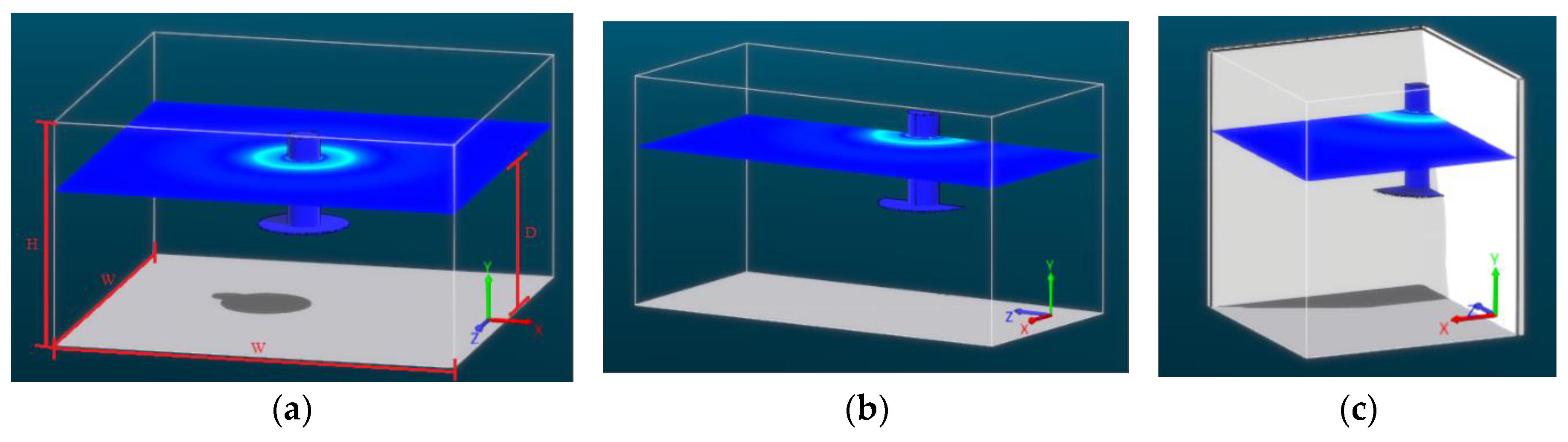

As previously stated, simulations of an oscillatory movement of A=50 mm and T=1.5 s have been carried out under different time step and lattice size conditions and their hydrodynamic force results studied to obtain a converged model. Convergence simulations were carried out with the entire heave plate model, using 16 and 32-core simulation clusters with 128 GB of RAM (Intel E5-26220 v4). The proposed lattices are shown in

Table 2:

As introduced in

Section 3.3, various parameters of the models have been taken into account in order to choose a convergence model: its stability parameter, its hydrodynamic force mean error w.r.t. the experimental results and also its Signal to Noise Ratio (SNR) to assess the quality of the obtained force signal. Moreover, the computational cost of the models was taken into account in order to select a model that balanced both precision and computational cost, since LES models are usually more costly than their RANS counterparts.

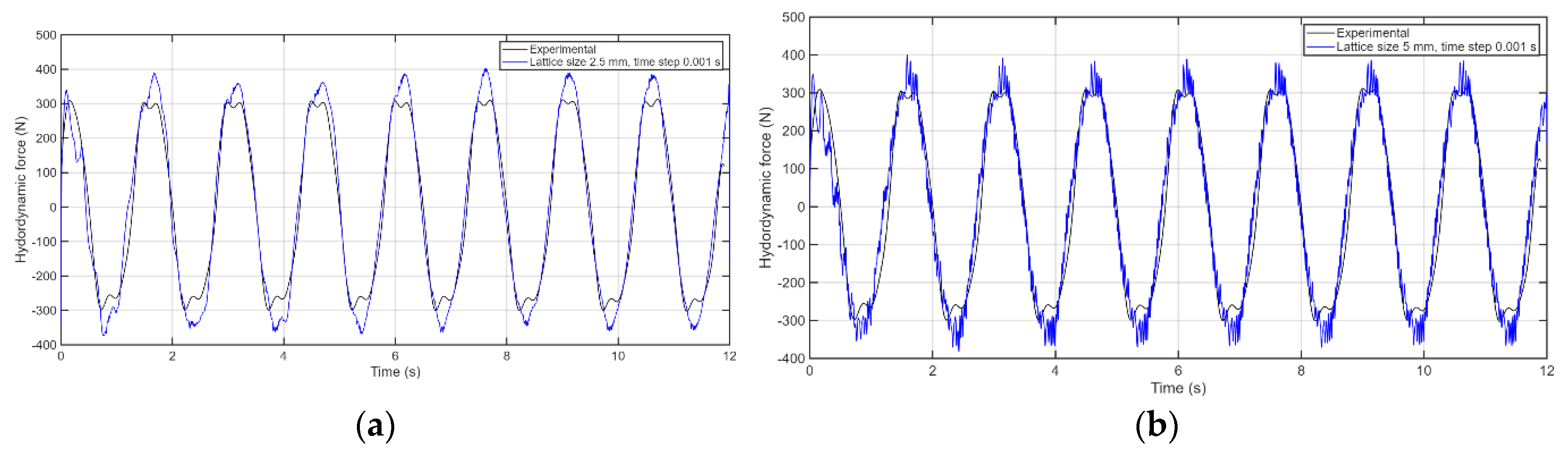

Models of time step 0.002 s were discarded due to poor stability, and the remaining candidates are presented in

Table 3:

Observing the results, it can be seen that the model with a lattice size of 5 mm and time step 0.001 s has better results in terms of mean error than its 2.5 mm counterpart. However, there is a 61% difference in the SNR parameter. This means that, although the mean error might indicate a valid model, the actual results present a higher degree of noise. By employing the SNR as a convergence analysis factor, it is possible to eliminate these false positives.

Figure 5 clearly shows the difference:

Thus, the selected model was that of a 2.5 mm lattice size and a 0.001 s time step.

After selecting the convergence model, a symmetry study of a half and a quarter of the model was proposed in order to reduce the computational cost of the simulations.

Table 4 shows the obtained results, also including the mean error of each symmetry model with respect to the entire heave plate model and the improvement in computational cost:

It can be seen that both symmetry models have differences smaller than 10\% with the original computational model and provide better computational costs. However, the quarter-symmetry model differs 13% from the original computational model.

Finally, since the computational cost was reduced, a convergence study of both half- and quarter-heave plate was proposed with a smaller minimum lattice size of 1.67 mm. This finer lattice size would have been unaffordable for models of an entire heave plate in terms of computational cost, but the symmetry models enabled the possibility to test it, with the objective of improving the accuracy of the model. Models were tested for 0.001 and 0.0005 s time steps and results can be seen in

Table 5:

It can be seen that no model improves the mean error relative to the experimental values, and the computational cost greatly increases. A smaller time step would be required to reduce the error, but it would make no sense since the models are non-competitive in terms of computational cost.

After the convergence and symmetry study, the optimal selected model to carry out this work was the half-symmetry model of 2.5 mm lattice size and 0.001 s time step. This model increases the error w.r.t. the experimental values 10% but supposes a 21.4\% improvement in computational cost.

4.2. XFlow Model Tests Under Extreme Cases

Once the time step and mesh convergence were both achieved, the computational model was tested under extreme cases of amplitudes and frequencies, as previously shown in

Table 1. These cases correspond to the highest and lowest KCs and β in Medina et al.[

24] that present the least uncertainties, thus ensuring the accuracy of the validation. Additionally, data from Cases 1 (KC=0.078, β=1108376) and 3 (KC=0.754, β=249138) will be compared with the results obtained by Zhang et al.[

35] by using OpenFOAM, a finite-volume method CFD software. In the referenced study, simulations were carried out using a SA-DDES (Spallart-Almaras Delayed Dettached Eddy Simulation) turbulence model, which allows for a transition from a RANS to a LES approach to better capture hydrodynamic phenomena related to vertices, since it was proven that a pure RANS model was not precise enough [

35].

Firstly, the unfiltered force coefficient time-series (following eq.7) of each case has been reflected in

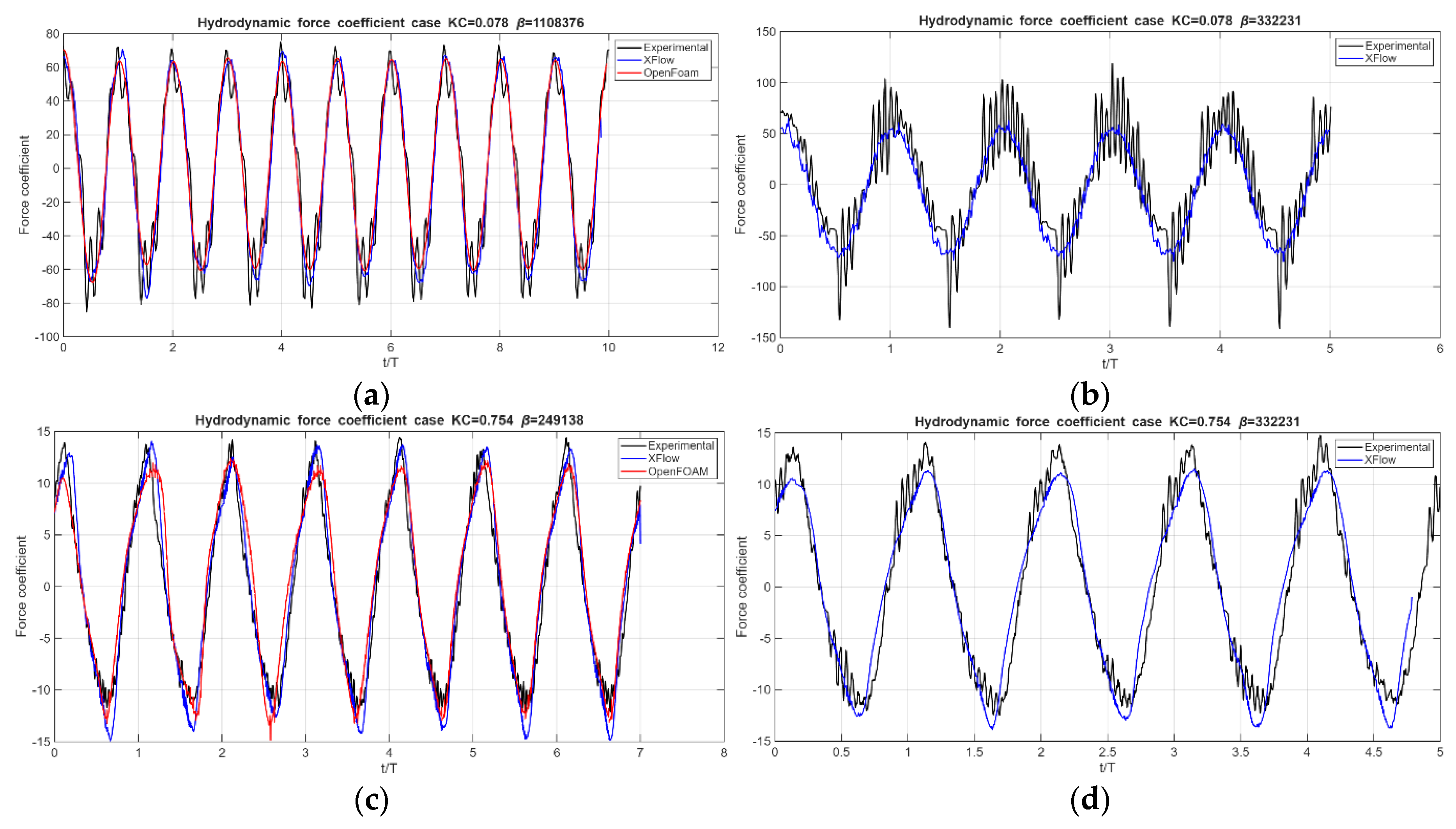

Figure 6:

As can be observed, there is a good correlation between the numerical and experimental results, meaning that the XFlow model can represent the real forces with accuracy. It can be seen that the numerical signals obtained via Xflow tend to be more symmetric in terms of values than their experimental counterparts, whose lower values are usually higher and present more noise. Nevertheless, numerical results tend to acquire negative peaks which are of greater magnitude than the values achieved by the positive peaks, as would be expected given the non-symmetric nature of the heave plate in its heave motion. Apart from uncertainties from the experimentation and the computational noise that can be seen in the numerical signals, the main differences between experimentation and simulation with Xflow come from lattice limitations: the minimum lattice size employed which, although precise enough, could provide better results when lowered and paired with an also lower time step. That would be an ideal case which is unaffordable in terms of computational cost as it has been proved in the convergence study, in which the model with the smallest mesh size and time step implies a 211% increase in the computational cost, demanding also to use 32 cores instead of the 16 that the current model uses. Another cause for deviations is the symmetry model used of half of the heave plate, which has a 0.5% higher mean error than the complete model, that is however compensated by the 27.2% decrease in computational cost. Finally, comparing Cases 1 (KC=0.078, β=1108376) and 3 (KC=0.754, β =249138) with the OpenFOAM results, it can be seen that results also correlate satisfactorily. For Case 1, differences are small, mainly located in the lower peaks, which appear underestimated by OpenFOAM. For Case 3, differences between the software maintain the same tendency, although in this case being greater due to the case being one of lower forces, which allows for a magnification of deviations due to mesh limitations in both programs. Xflow appears to better represent the higher peaks in the force coefficient, whereas OpenFOAM correlates better in the lower ones.

The case of KC=0.078 and β =332231 presents a strong noise component in the experimental results, which is due to the low magnitude of the forces measured. The load cell used in the experiment had a range up to 500 N, and the measured forces go up to a maximum of 20 N (4% of the load cell range), so in this case any vibration reflects significantly in the obtained signal. Moreover, the actuator has its own time step when inducing the movement, that also results in added noise, especially in the lower peaks of the force. This noise is less significant when the magnitude of the measured forces increases and approaches 50% of the measuring range of the load cell. This also affects positively to the correlation with the numerical results. Following this reasoning, cases of KC=0.078, β =1108376 and KC=0.754, β =249138 present the best correlation (both around 200 N of amplitude, 40% of the measuring range). Case of KC=0.754, β=332231 achieves amplitudes of 300 N (60% of the range) and presents an increase in the noise of the signal.

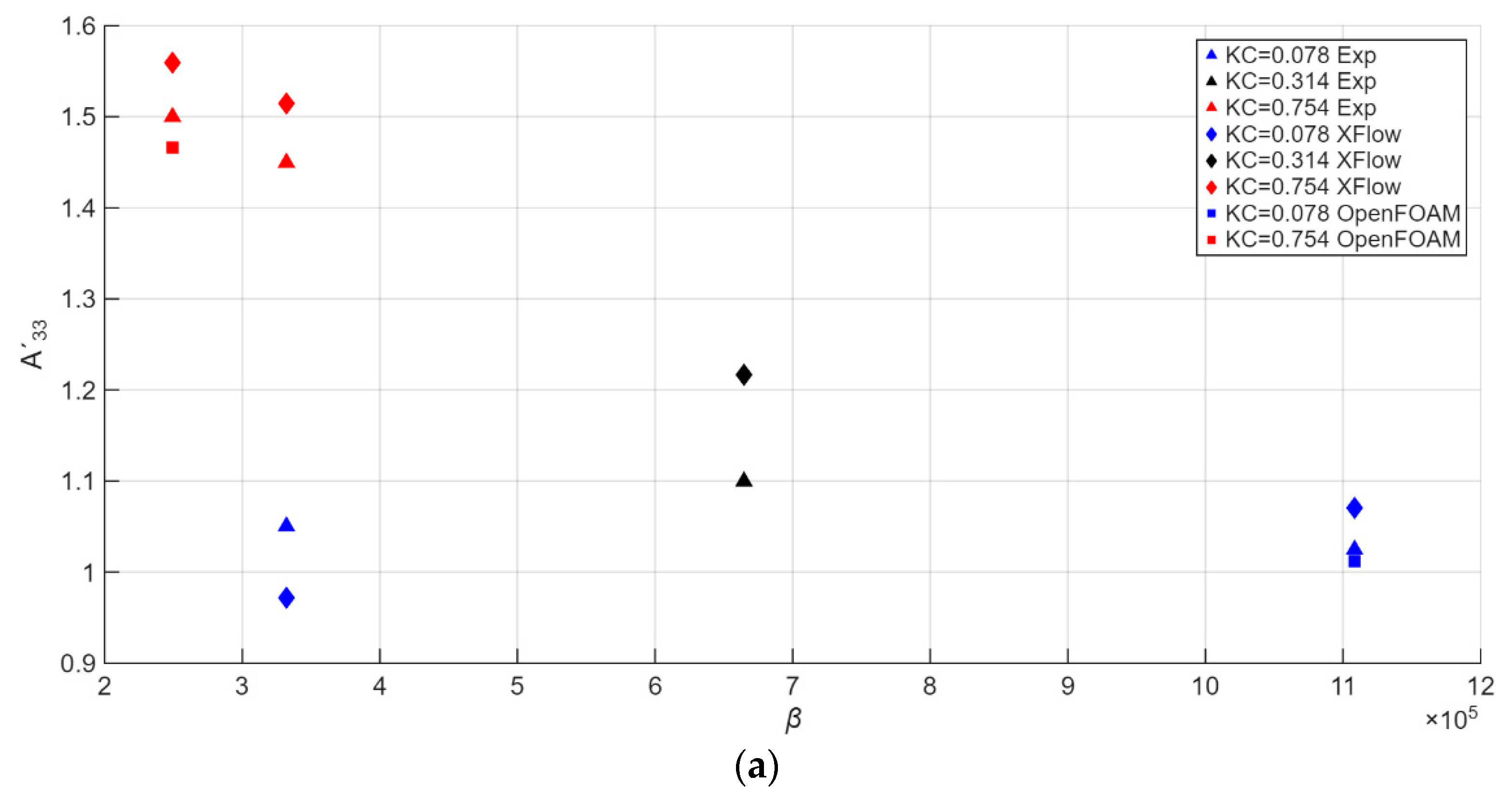

Once the forces have been studied, the hydrodynamic coefficients of added mass A’

33 and damping B’

33 have been obtained. Non-dimensional results are shown in

Figure 7 and compared with the ones obtained in Medina et al.[

24]. Furthermore,

Table 6 compares numerically the differences between numerical and experimental results.

Differences in the added mass coefficients are under 10% for the extreme test cases, with a mean value of a 5% difference. The central case presents a larger difference, thus proving the proposition by Medina et al.[

24] that the correct experimental value should be higher. The differences follow the same tendency described in the analysis of the obtained forces: the lowest values are obtained for the cases of KC=0.078, β=1108376 and KC=0.754, β=332231, whereas the biggest difference occurs in the most difficult case to measure (KC=0.078, β=332231).

For the damping coefficients the same tendency applies, but for higher values in the difference. Moreover, as per Medina et al.[

24], experimental tests had their results corrected by also performing no-load tests, which explains why all the experimental damping coefficients are slightly lower than the numerical ones, and also why differences are also higher than the ones obtained in the added mass coefficients.

Regarding the comparison with OpenFOAM, results for both coefficients are very similar, with OpenFOAM providing lesser errors in the added mass coefficient (1.3% and 2.3% in comparison to XFlow’s 4.4% and 3.9% for cases of KC=0.078, β=1108376 and KC=0.754 and β=249138 respectively). For the damping coefficients, XFlow has a lesser error than OpenFOAM in the case of KC=0.078, β=1108376, which suggests a better representation in cases of higher hydrodynamic loads. Nevertheless, such low differences can be attributed to the computational noise of each mesh.

4.3. Vorticity Field Analysis

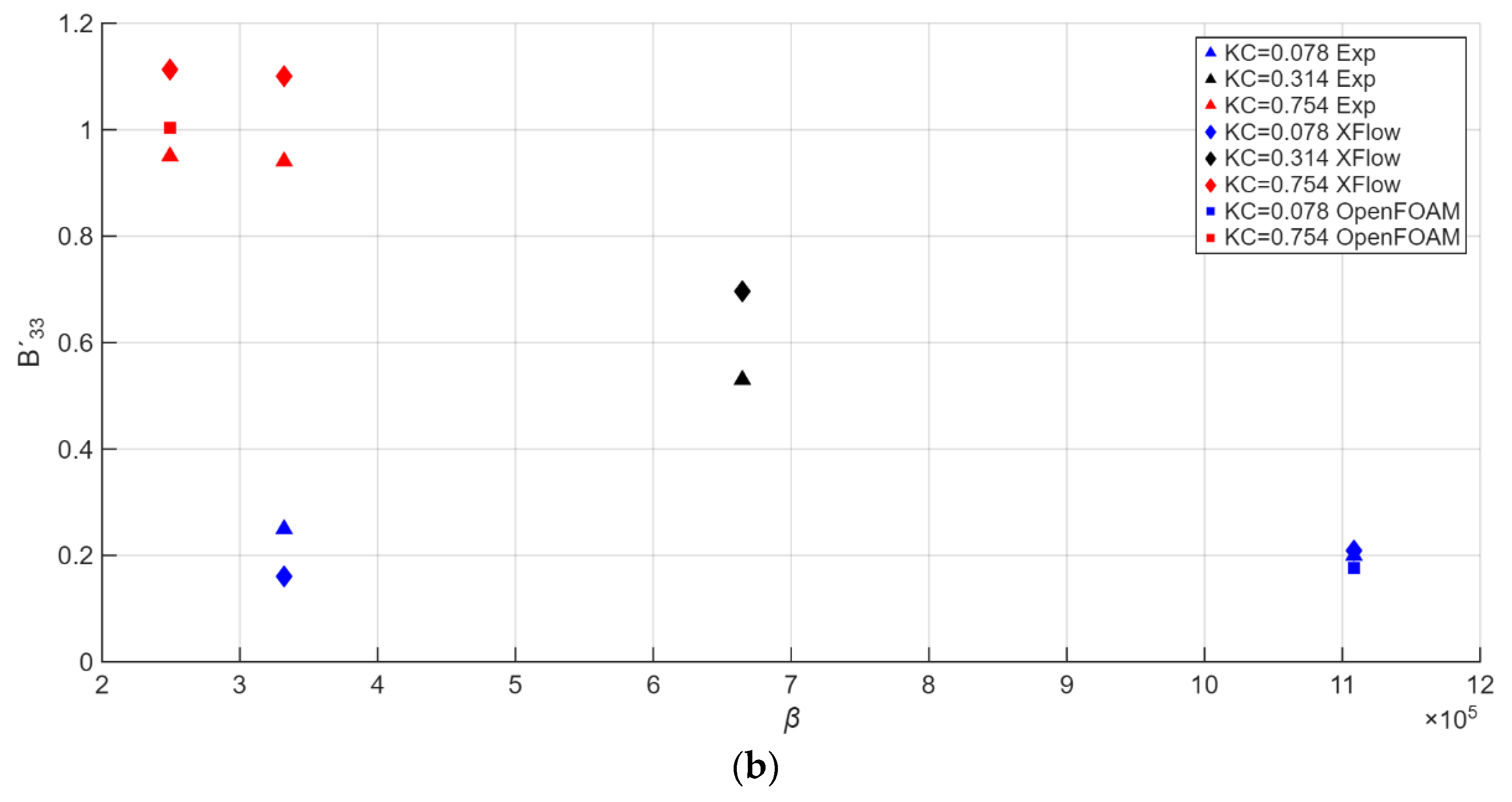

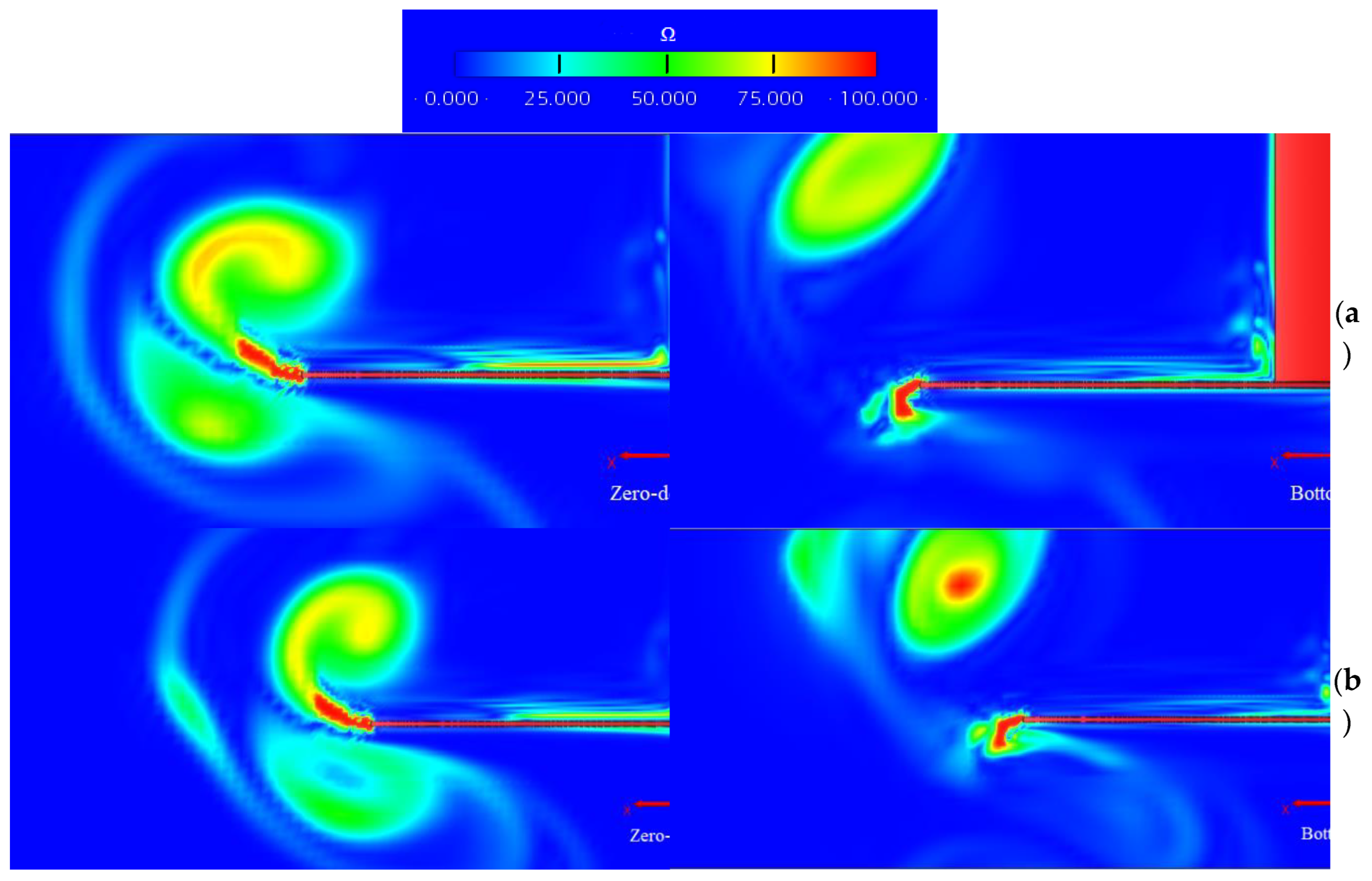

Finally, the non-dimensional vorticity fields obtained for each of the extreme cases and in two different positions (the lowest amplitude of the motion and the zero-position going downwards) are presented in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9. The norm of the vorticity has been nondimensionalized using the oscillation frequency of each case following eq.11:

It can be seen that the vortices produced are of greater size when the KC increases, which comes from an increase in the amplitude of the movement and means greater force values, as previously seen. However, for the same KC the magnitude of the vorticity is greater for cases of greater β, which correlates to the higher forces obtained for those cases when compared with their same KC counterparts. That translates to the cases of KC=0.754, β=332231 and KC=0.078 and β=1108376 having the highest values of vorticity.

4.3. Assessment of Pressure-Induced Forces

In addition, a method to test the influence of the pressure-induced forces is introduced. It is known that these forces dominate over their viscous counterparts at low KCs. Tao and Cai [

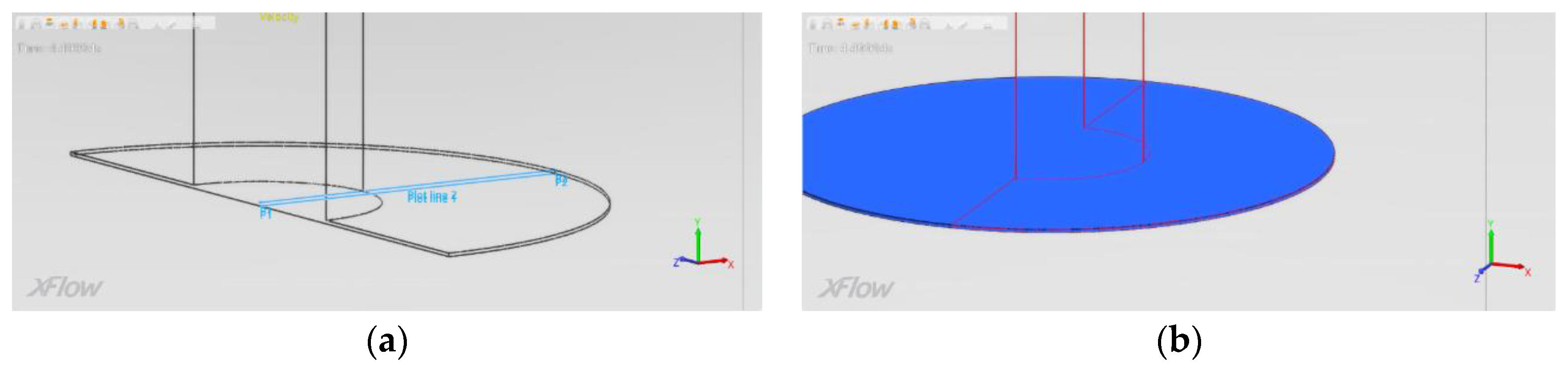

39] stated that this dominance happens for KC < 1. Since the cases tested in this work fulfil this condition, all of them have been studied. The total force (without inertial effects) was calculated via pressure integration and compared with the results provided by XFlow at four different instants: when the heave plate reaches its top and bottom positions, and when it passes through the zero position with upwards and downwards directions. The method was carried out with two different approaches, one assuming azimuthal symmetry and the other using tools provided by Xflow. For the first one, two radial lines were plotted in both the upper and lower surface of the plate, and the total pressure in the heave axis measured in 500 points (the number of elements that comprises the radius’ length). Afterwards, assuming azimuthal symmetry, the pressure difference was integrated. The second approach consisted in introducing a post-processing cylinder with the same dimensions as the plate, and the total pressure was integrated with Xflow’s surface integrals. The radial lines and the cylinder employed can be seen in

Figure 10. Results are reflected in

Table 7:

It can be seen that both calculation methods provide accurate results with acceptable differences with respect to the reference values. The surface integration method consistently provides better results, with absolute differences below 10%, while the azimuthal integration surpasses a 20% difference in some instances. This difference between approaches may come from the fact that, although symmetry in the heave plate’s behavior can safely be assumed, in reality there are small asymmetries that are revealed when integrating just a radial measurement. The measured position where the biggest differences for both approaches have been observed is the zero-downwards one. This is explained by the fact that this is a position of maximum acceleration, force, and vorticity, and also where the biggest mass of water is being displaced, which makes for a more difficult measurement. Nevertheless, both methods provide a good approximation and also demonstrate the importance of pressure-induced forces over viscous forces.

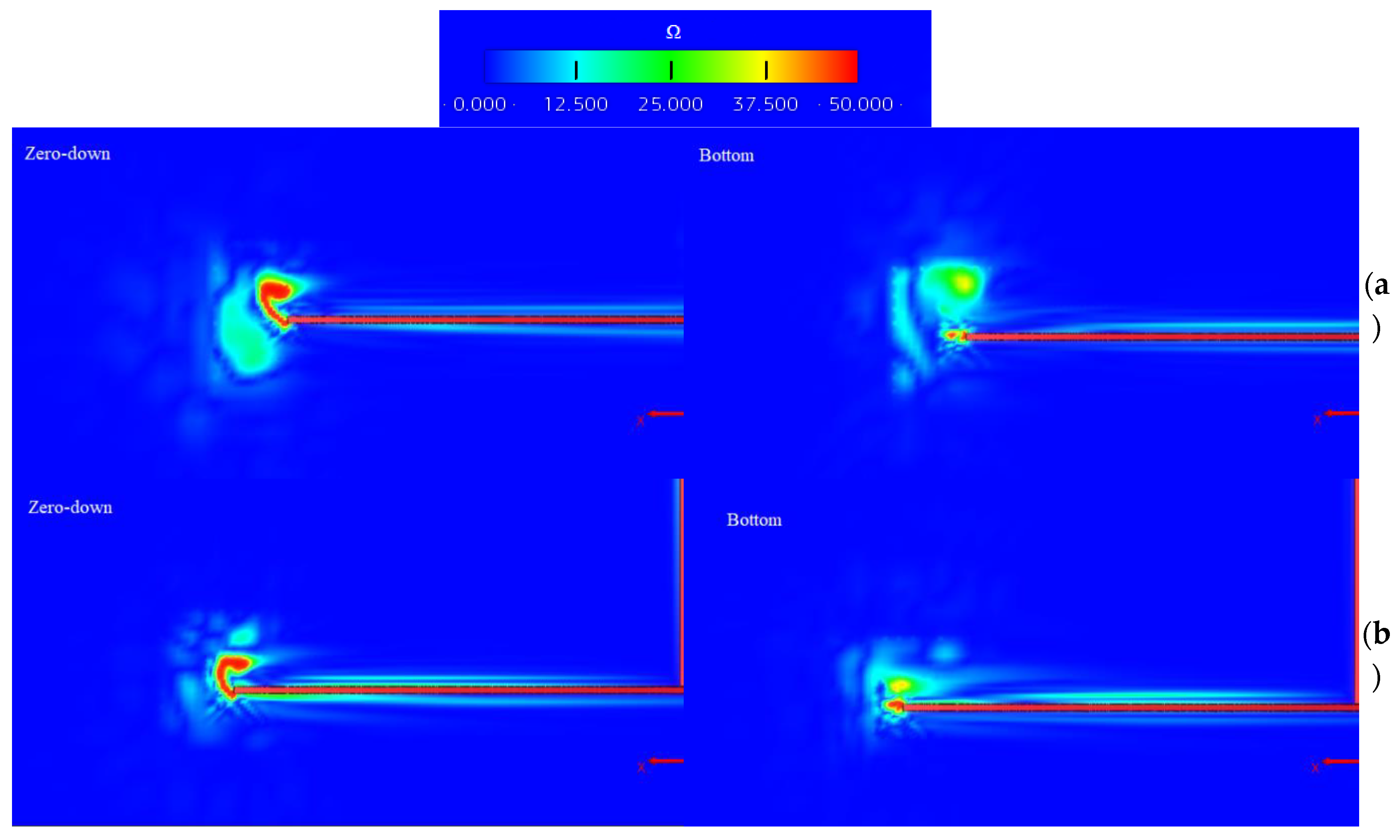

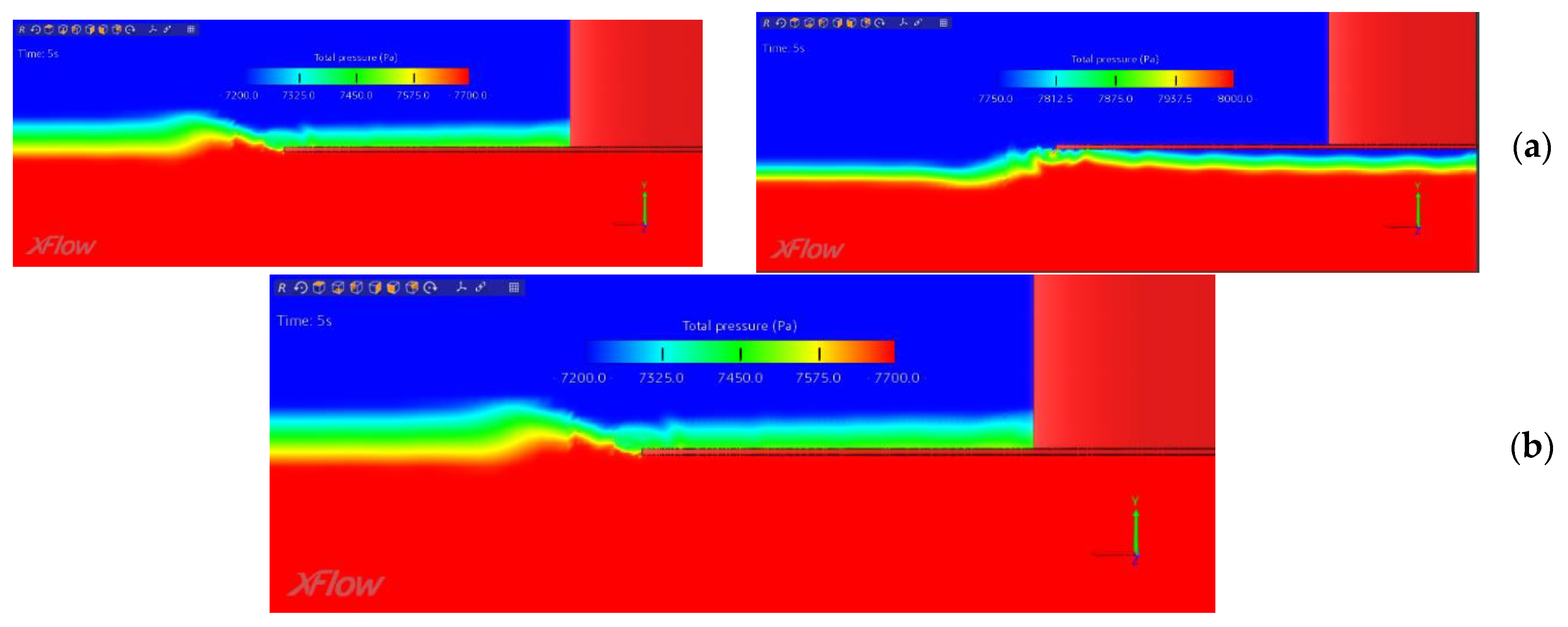

Finally,

Figure 11 illustrates the total pressure field for both upper and lower surfaces of the heave plate for case of KC=0.754 and β=332231 in the zero-downwards and bottom positions:

In the zero-down position a greater pressure difference can be seen between both the upper and lower surfaces of the heave plates. The pressure distribution on the lower surface of the heave plate is especially remarkable, since it follows a parabola-like curve, with the lowest values of pressure near the center of the heave plate, and the highest near the edge, where the turbulence breaks the uniformity of the pressure distribution. The upper surface presents a more constant distribution from the column to the edges, with the pressure slightly decreasing when approaching the edge. The total overall pressure values are higher on the lower surface than on the upper one, as could be expected. Finally, in the bottom position the measured force was lower than in the zero-downwards one, which translates to lower differences in pressure between both faces, as obtained.

5. Conclusions

In this work, the Lattice-Boltzmann, LES software XFlow has been used -for the first time to the best of the authors’ knowledge- to develop a 3D CFD model of a heave plate flexible enough to keep its accuracy under extreme conditions of amplitudes and frequencies under forced oscillations in heave, thus becoming the first model of its type to be used for industrial applications. The model has been validated with previous experimentation results from Medina et al.[

24] and with some simulation results obtained with a finite-volume software (OpenFOAM) using a SA-DDES software [

35]. To achieve this, the following milestones were reached:

Mesh and time-step convergence and symmetry study: to select an optimal model that balanced computational cost and accuracy, a convergence study was carried out with a case of medium amplitude and frequency (KC=0.314, β=664709). The stability parameter, mean error w.r.t. experimentation and Signal to Noise Ratio (SNR) were studied. It was concluded that the model of 2.5 mm minimum lattice size and 0.001 s time step was the optimal model. Afterwards, a symmetry study was conducted in order to assess the possibility of working with models of a quarter or a half of the heave plate to reduce the computational cost. Models provided a good behavior and a decrease in computational cost compared with the convergence case, and thus a new lattice size of 1.67 mm was tested to improve accuracy. However, errors did not improve, and computational cost was non-competitive. After both studies, the selected model was of half-symmetry and consisted of a minimum lattice size of 2.5 mm, a time step of 0.001 s and a computational cost of 23.5 days in a 16-core computational cluster.

Validation under extreme cases: the cases selected combined 2 different amplitudes and frequencies extracted from [

24]. A study of the force coefficient provided good correlation, especially in the cases of higher forces, with XFlow achieving greater values in the lower peaks of the force. A noise component in the experimental results was also observed, whose importance was reduced with the increase of the measured force. In addition, the added mass and damping coefficients were studied, obtaining a mean difference of 5% for the added mass coefficient, and greater differences in damping, which stem from the correction of results carried out by Medina et al.[

24] by conducting no-load tests of the heave plate. Moreover, the general differences were assessed to come from lattice limitations and the assumption of symmetry to reduce computational cost.

Comparison with OpenFOAM: two of the extreme cases were compared with results obtained by Zhang et al.[

35], with good correlation found between both software. In terms of force coefficient, XFlow tended to better represent the higher peaks of the force. In terms of added mass and damping coefficients, both software provided good results, with XFlow better representing the case of highest frequency studied.

Vorticity study: after validating the numerical results, a study of the dimensionless vorticity field was carried out in two different positions (bottom and zero-downwards) to better understand the behavior of the heave plate. It was observed that vortices increased when KC increased, and that for the same KC, lower frequencies produced higher vorticities, thus correlating with the higher forces obtained.

Pressure integration method: apart from the development of the model, a method to characterize and demonstrate the prevalence of pressure-induced forces over viscous forces at low KCs was proposed and validated for all cases. Two different approaches were taken: a mathematical integration of a radial pressure measurement and a surface integration tool provided by XFlow. Results for the surface integration approach showed better accuracy due to the non-symmetric nature of the real flow around the heave plate, with differences under 10% w.r.t. the measured forces. Moreover, the total pressure field was studied for the case of KC=0.754 and β=332231 in the bottom and zero-downwards position, with results that matched the numerical ones.