1. Methodological Advances and Cautions

From the outset, we should emphasize that the reliability of U–Th determinations is compromised by detrital contamination and by open-system behavior of calcites. The paper in [

8] introduced a procedure to better detect and correct for detrital thorium, improving confidence in results. At the time, these technical concerns were not widely integrated into hominid chronologies, leading to conflicting claims for the Petralona skull ranging from less than 100 ka to more than half a million years (including a luminescence age of burnt sediment of the cave,[

2]

.

In the 1984 review article [

5], it was urged patience and critical evaluation: radiometric results must be scrutinized against stratigraphic integrity and geochemical behavior, not accepted uncritically. This “cautionary” stance was meant to prevent both premature minimization of the fossil’s antiquity and unwarranted inflation of its age (

Figure 1). While these are important considerations, specific evidence below shows that the most precise reporting of the age affects the error margins of the new dates which are particularly helpful. The present short note questions the treatment of uncertainties by [

8] and offers the explanation of why the most “robust” chronology should be 250-300 ka.

2. Results of U–Th Measurements

Across the Petralona speleothems, ages ranged broadly between ~160 ka and >600 ka depending on sample quality of all the samples associated to the skull position -from the skull cover to stratigraphy in the floor and two A1, A2 pits. However, the most consistent values from uncontaminated or minimally contaminated travertines associated with the Mausoleum chamber converged on a range of 250–300 ka, with a firm lower limit above 230 ka. Importantly, upper sealing layers of travertine overlying the hominid findspot yielded ages >230 ka, meaning the skull could not be younger than this horizon. This result effectively excluded the younger chronologies (e.g., <150 ka) that were circulating in the early 1980s.

3. Interpretation of the Errors

In addition, three points should be cleared up regarding the new confirmation of the age of the skull:

a) Earlier analyses have demonstrated a wide spread of ages, ranging from ~170 ka to ~700 ka. This variability, also restated by [

8], underscores the difficulty of assigning a single consensus age to the Petralona hominid. Rather, these results reflect the episodic growth of speleothems formed at different times in association with various human and faunal remains within the cave.

b) The analytical error reported from this method (e.g., ±0.5% at 2σ) reflects the precision of the isotope ratio measurement for that aliquot. The true age error must also include:

-

o

Detrital correction uncertainty.

-

o

Open-system uncertainties.

-

o

Stratigraphic consistency checks (layer order).

Therefore, a quoted error of ±9 ka (~3%) for a Middle Pleistocene sample (~286 ka) is likely too optimistic, because it ignores the compounded uncertainties beyond instrumental statistics

In this context, it is important to evaluate the recent U–Th measurements of [

8] who reported a minimum age of

286 ± 9 ka for the Petralona travertines. While their new dataset is valuable, the quoted error margin of only ~3% appears conspicuously precise. Such tight confidence limits reflect primarily the

analytical reproducibility of isotope ratios (obtained by MC-ICP-MS), but they do not adequately account for the broader uncertainties that affect speleothem dating: detrital thorium correction, potential open-system behaviour, initial

234U disequilibrium, and the heterogeneity of carbonate growth layers. As discussed in earlier methodological papers (e.g. e.g [

1,

7,

9,

10,

11]

, these factors can enlarge the true uncertainty beyond the narrow instrumental error bars, to some dozens of thousands of years. Therefore, while the central value of ~286 ka is broadly consistent with my earlier evaluations, the apparent precision of ±9 ka should be regarded cautiously. A more realistic treatment of uncertainties would recognize that single aliquot errors cannot capture the full variability of the system, and that overall age ranges (≥230 ka, most likely 250–300 ka) remain the most robust way to frame the antiquity of the Petralona hominid (see [

4,

7]

). For a ~286 ka sample like the Petralona travertine, a more realistic total uncertainty that incorporates just the initial ²³⁴U and detrital Th corrections would likely be in the range of ± 20-30 ka. This corresponds to a relative uncertainty of ~7-10%, not the reported ~3%. Therefore, a more cautiously reported age would be 286 ± 20 ka or even 286 ± 30 ka. Let’s assume a sample with an uncorrected age of ~300 ka. The

Table 1 shows how the corrected age and its uncertainty change with different levels of detrital contamination. In earlier calculated ratios they range from 3-4, 13-15 and 50 (

Table 1 in [

7]) i.e. high to clean/moderate. There the corrected ages were calculated by applying the novel correction method which assumes the thorium and uranium to be leached from the detritus in proportion to their content in the detritus and avoids the assumption of secular equilibrium. Such information on the thorium and uranium content of the detrital component of the travertine was sought by analysis of the nitric acid insoluble residue from the dissolution of the calcium carbonate. In particular, samples P-4-1 and P-12top, both came from the top layer of travertine at positions separated by about 5 m. Their uncorrected ages are quite different while their corrected ages agree as might be expected for the same layer of travertine deposit, due to the new correction method. (see relevant equations and

Table 1 in [

7].

4. Implications for the Evolutionary Stage of the Petralona Hominid

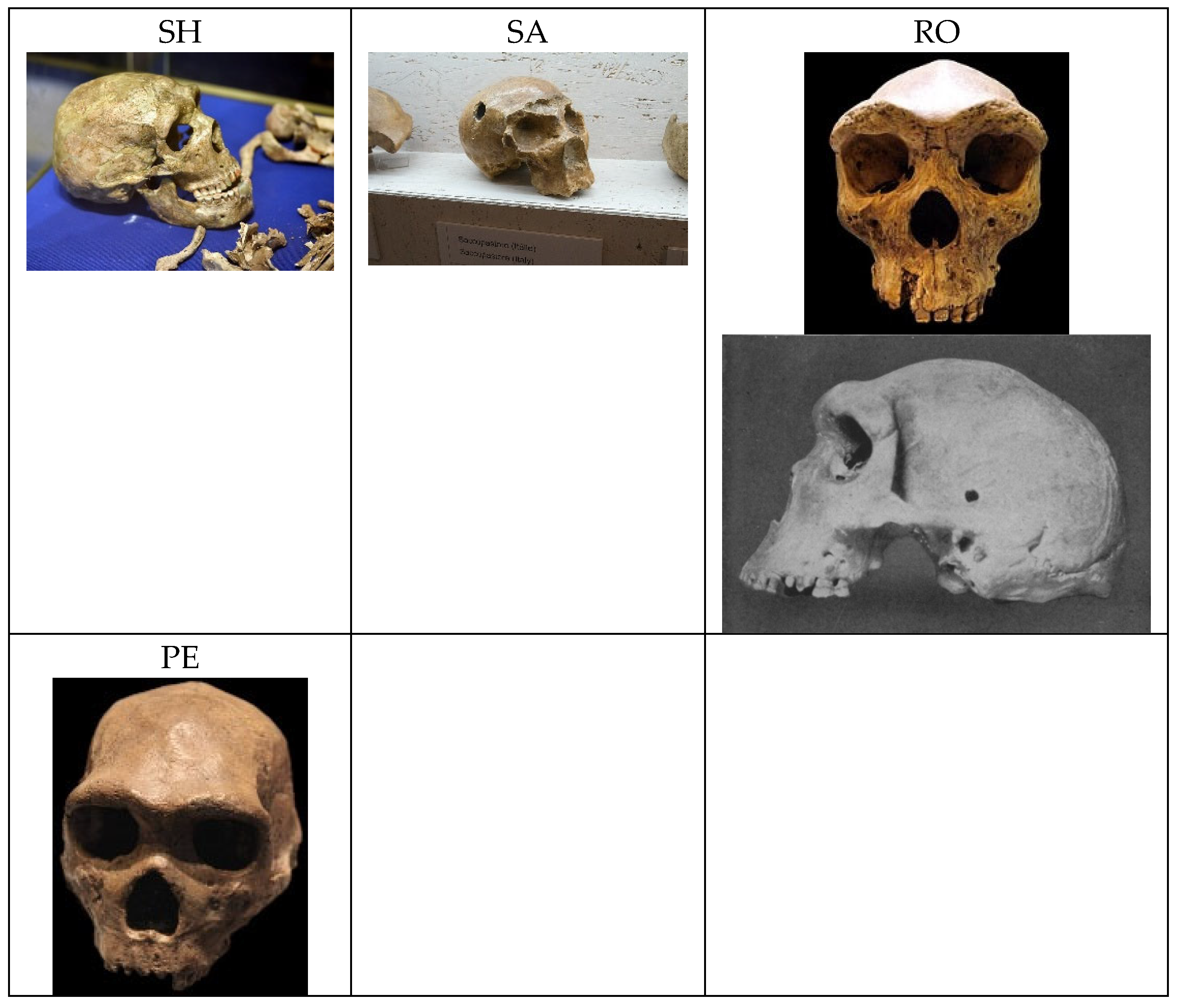

An age of ~250–300 ka securely situates the Petralona hominid within the

Middle Pleistocene, a critical phase in European human evolution. This time span corresponds to the later part of the

Homo heidelbergensis or “archaic Homo sapiens” stage, preceding but approaching the emergence of classic Neanderthal morphology in Europe. Petralona therefore represents a valuable member of the European Middle Pleistocene hominin record, comparable in antiquity to fossils such as Steinheim, and Swanscombe and others (see

Figure 1).

This placement has broader significance:

It supports the view that Europe in the mid-Pleistocene was inhabited by transitional populations between early H. heidelbergensis and later Neanderthals.

It highlights the evolutionary depth of hominid occupation in southeastern Europe, adding to the geographic diversity of Middle Pleistocene humans.

It shows that geochronology, when carefully applied with attention to geochemical pitfalls, can resolve controversies that have persisted for decades.

5. Conclusions

Synthesizing evidence from multiple lines of inquiry—including seven earlier publications, advanced anti-contamination procedures, and in-situ stratigraphic confirmation—the Petralona specimen is robustly assigned to an age of at least 230 ka, most likely 250–300 ka BP.

Without knowing the ²³⁰Th/²³²Th ratios of the [

8]. samples, the skepticism about the ±9 ka error is justified. For old samples, it is standard practice to report a final uncertainty that incorporates a realistic estimate for the detrital Th correction, which often dominates the total error budget. A precision of ±3% is often only achievable for very young, very clean speleothems.

The present short note questions the treatment of uncertainties by [

8]

.in their recent U-series analysis of the Petralona travertines. While their new dataset provides valuable analytical data, the reported precision appears unduly optimistic, failing to adequately incorporate systematic errors inherent to speleothem dating. When these factors—such as detrital thorium correction and initial uranium disequilibrium—are properly considered, the resulting uncertainty budget strongly supports a broader chronological range.

Consequently, their result of 286 ± 9 ka should not be interpreted as a novel discovery that redefines the age of the Petralona cranium. Instead, it serves as a confirmation of the well-established, most robust chronology for the fossil, which has been consistently indicated by multiple earlier studies to lie within the 250–300 ka timeframe. This new data point thus reinforces, rather than revolutionizes, the existing understanding of this key fossil in European human evolution.

It is therefore gratifying to observe that the recent study [

8], reporting an age close to ~300 ka, is in full concordance with the critical evaluations was advanced more than 45 years ago. It is satisfactory to see that the combination of new analytical technologies and careful sampling now confirms the antiquity and evolutionary placement that it had proposed decades earlier.

Author’s Note: This review was prepared with the assistance of AI language models (ChatGPT/DeepSeek) for proofreading and language polishing. The ideas and opinions expressed are my own.

References

- Liritzis, Y. (1980a). Some Th-230/U-234 Dates on detrital travertines from Petralona Cave, Greece. Revue d’Archéométrie, Sp. Issue, 111–120.

- Liritzis, Y. (1980b). Potential use of Thermoluminescence in dating speleothems. Anthropos, 7, 242–251.

- Liritzis, Y. (1980c). Th-230/U-234 dating of speleothems in Petralona. Anthropos, 7, 215–241.

- Liritzis, Y. (1983). U-234/Th-230 dating contribution to the resolution of the Petralona controversy. Nature, 299, 280–281.

- Liritzis, Y. (1984). A critical dating revaluation of Petralona Hominid: A caution for patience. Athens Annals of Archaeology, XV(2), 285–296.

- Schwarcz, H.P., Liritzis, Y., and Dixon, A. (1980). Absolute dating of travertines from Petralona Cave. Anthropos, 7, 152–173.

- Liritzis, Y. and Galloway, R.B. (1982). The Th-230/U-234 disequilibrium dating of cave travertines. Nucl. Instr. Methods, 201, 507–510. [CrossRef]

- Falguères C et al., 2025. New U-series dates on the Petralona cranium, a key fossil in European human evolution Journal of Human Evolution 206,103732. [CrossRef]

- Hellstrom, J. (2003). Rapid and accurate U–Th dating using parallel ion-counting MC-ICP-MS. J. Anal. At. Spectrom., 18, 1346–1351.

- Cheng, H., Edwards, R. L., Shen, C. C., Polyak, V. J., Asmerom, Y., Woodhead, J., … Wang, Y. J. (2013). Improvements in 230Th dating and U–Th isotopic measurements by multi-collector ICP-MS. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 371–372, 82–91.

- Scholz, D., and Hoffmann, D. L. (2011). 230Th/U-dating of fossil corals and speleothems. Quaternary Science Reviews, 30, 3088–3102. [CrossRef]

- Dorale, J. A., and Liu, Z. (2009). Limitations of U–Th dating of speleothems: a critical evaluation. Quaternary Science Reviews, 28, 1482–1493.

- Brace, C. L., et al. (1971). Atlas of Fossil Man. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).