Submitted:

03 December 2025

Posted:

04 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Energy Inefficiency in Buildings

1.2. Impact of Residential Lighting on Health

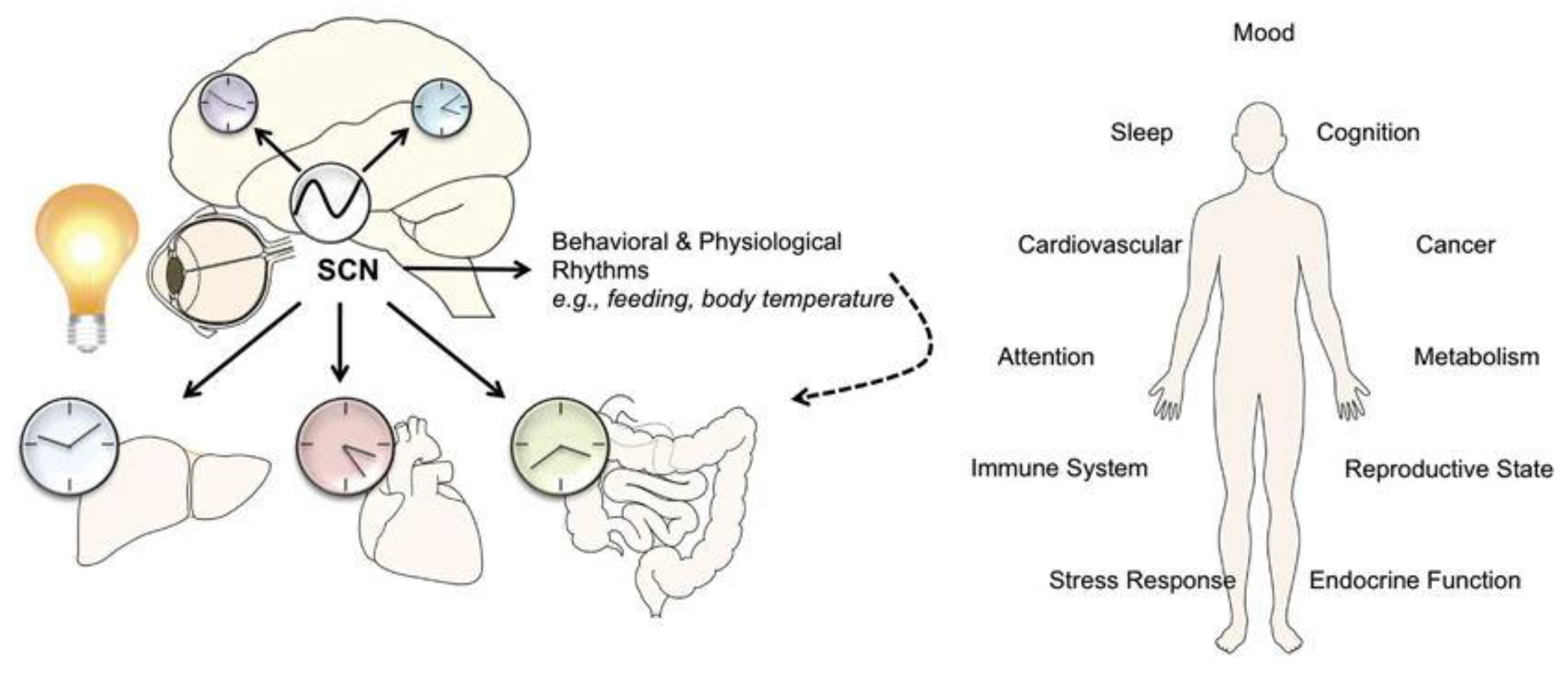

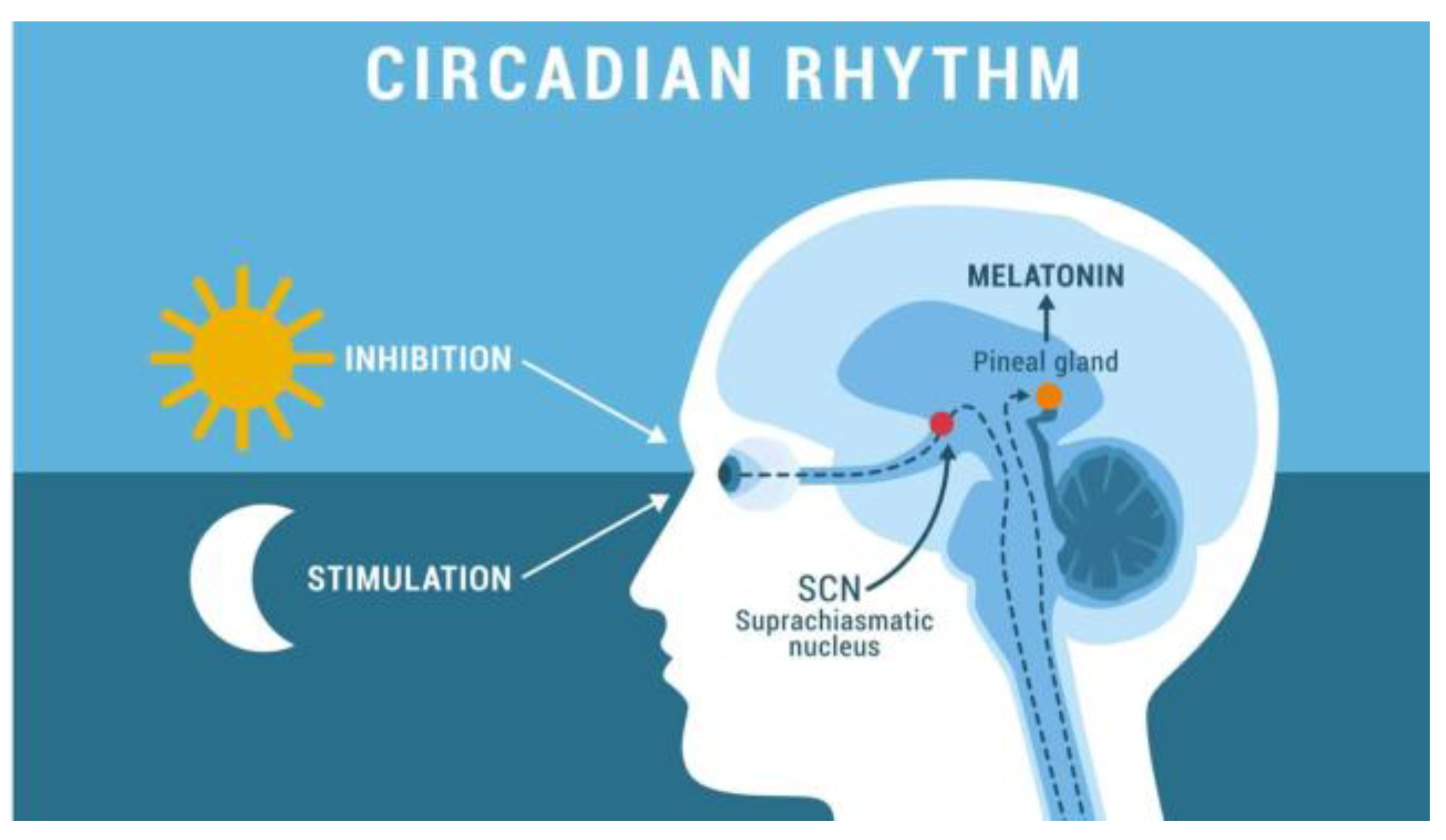

1.2.1. The Circadian Rhythm

1.2.2. Impact of Artificial Lighting on Human Health

1.3. Lighting Quality Metrics and Performance Factors

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Sampling Strategy

2.3. Data Collection

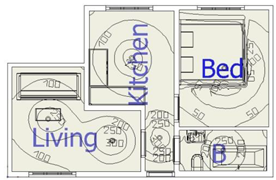

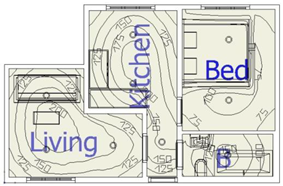

2.4. Simulation Protocol

- Model 1: Recreated the existing manual lighting design based on original specifications.

- Model 2: Proposed an optimized design incorporating circadian and biophilic principles, LED luminaires, and dynamic smart controls.

2.5. Analytical Framework

- Electrical energy consumption (kWh)

- Average illuminance (lux)

- Luminous efficacy (lm/W)

3. Results

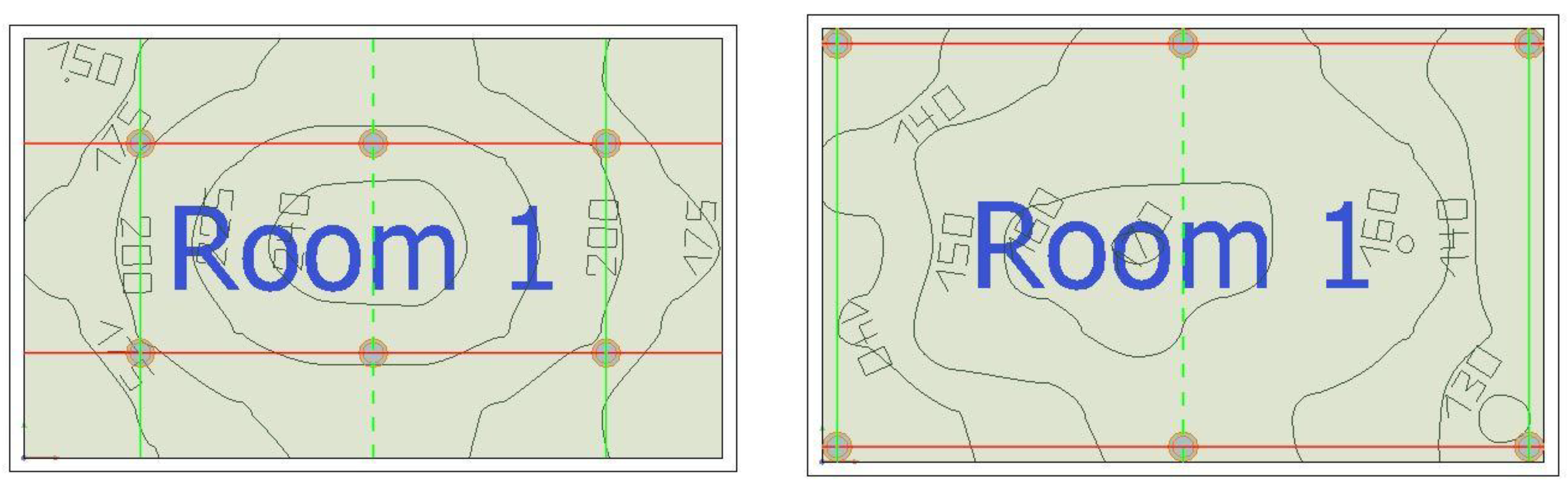

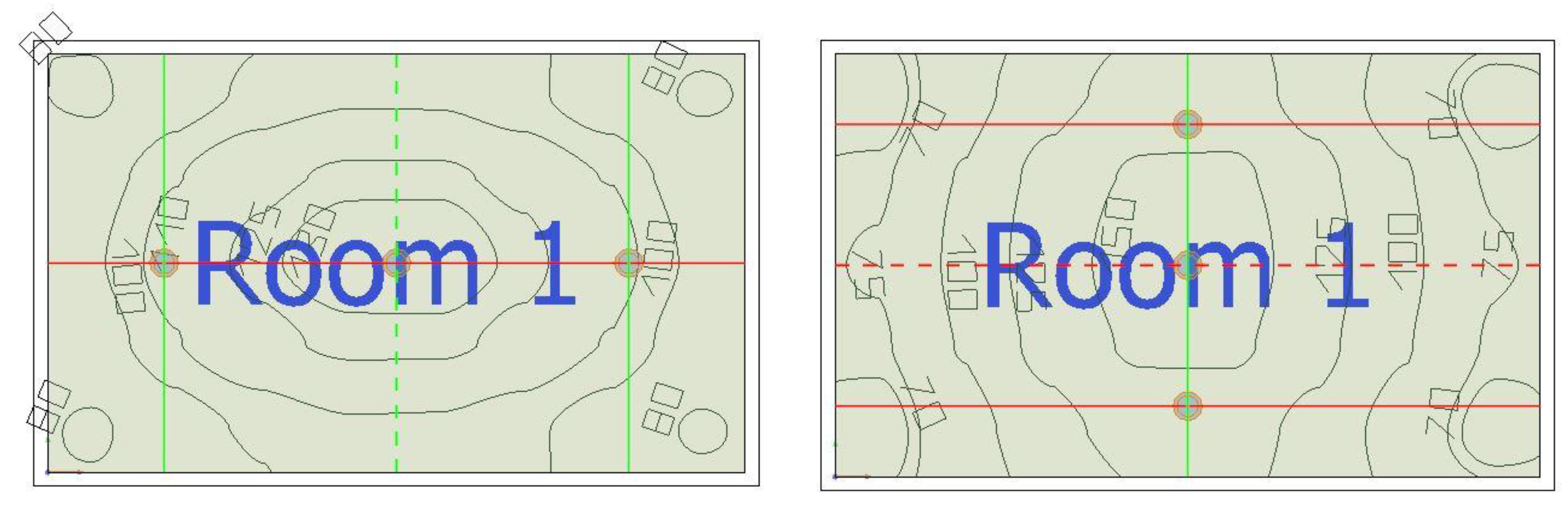

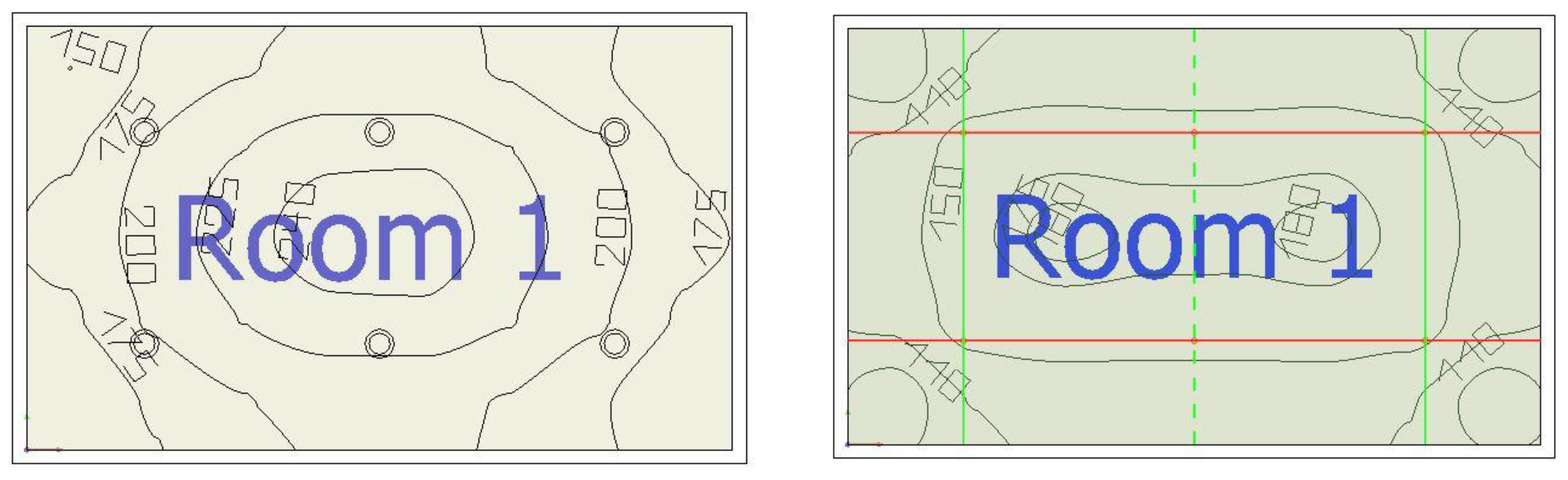

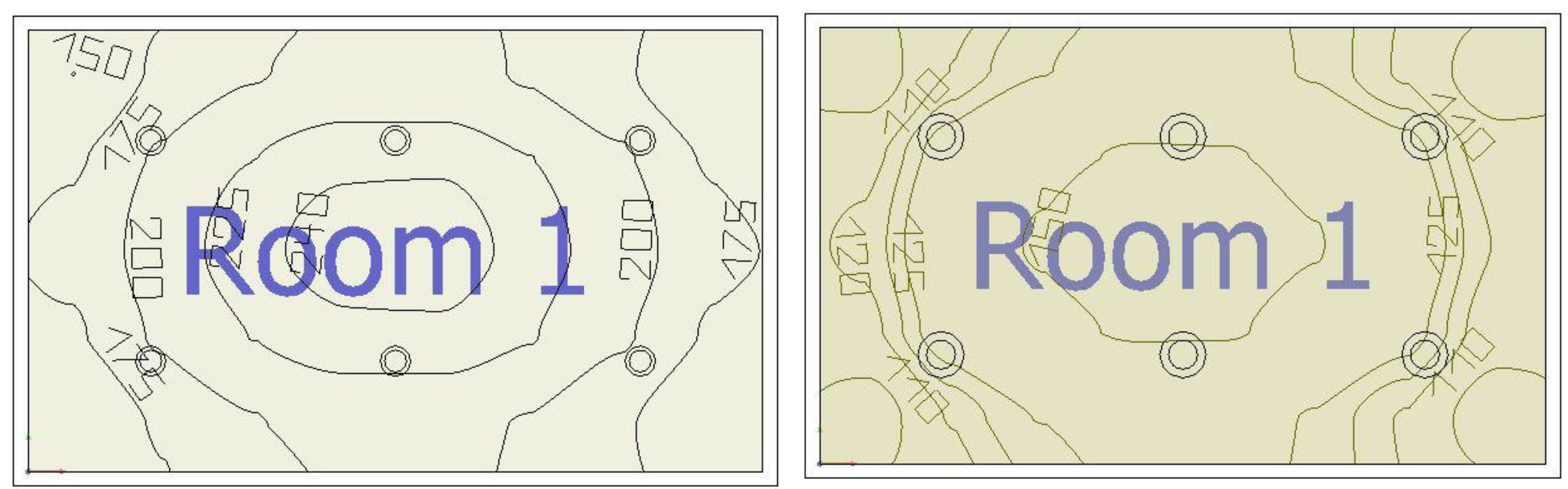

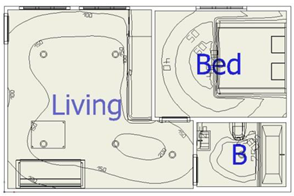

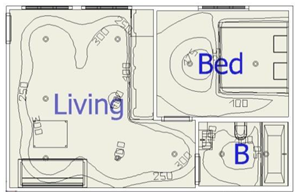

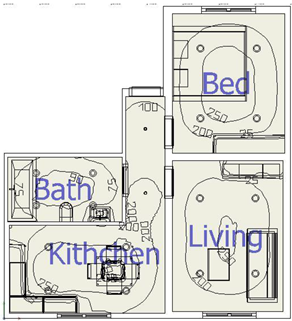

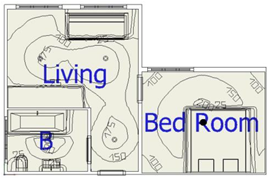

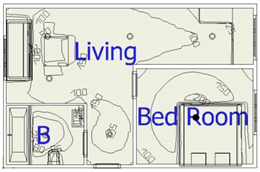

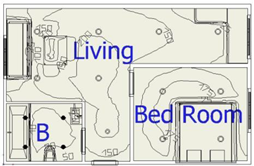

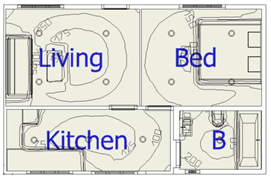

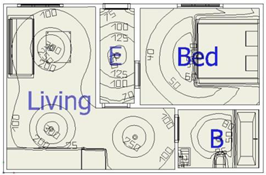

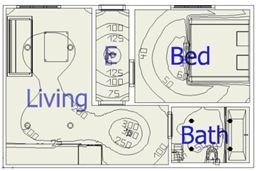

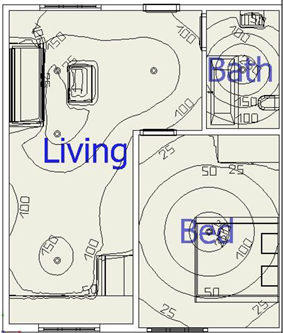

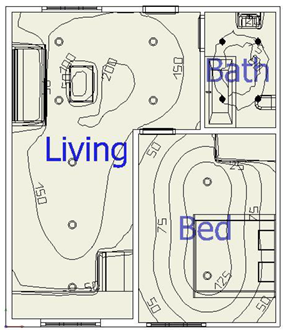

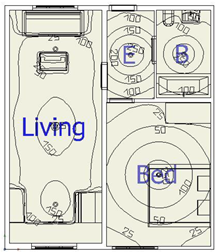

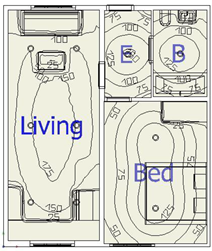

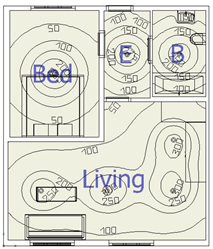

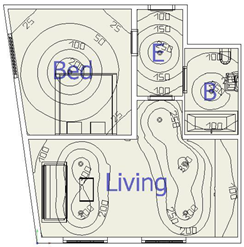

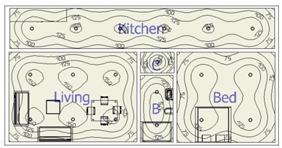

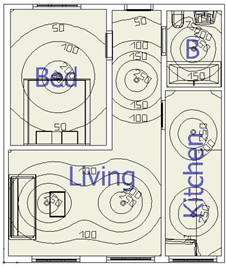

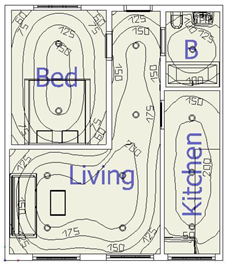

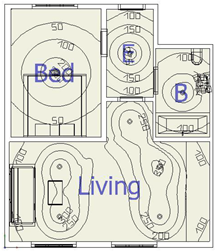

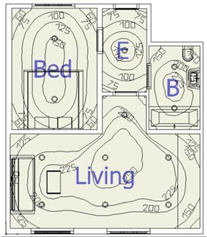

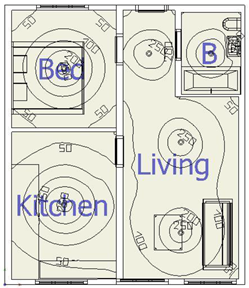

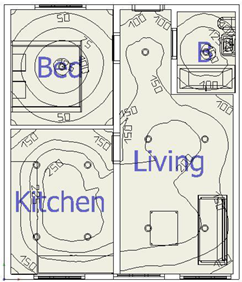

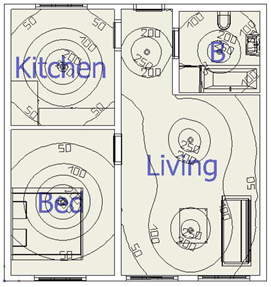

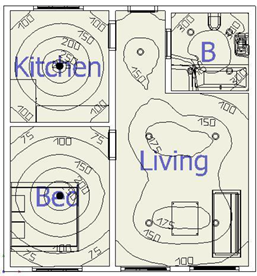

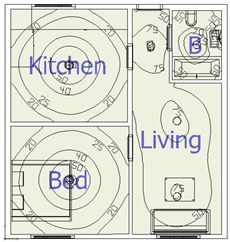

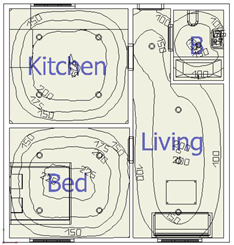

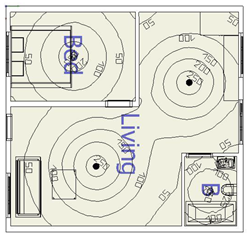

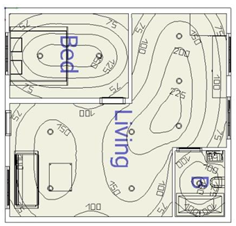

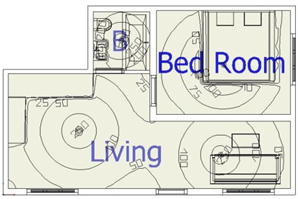

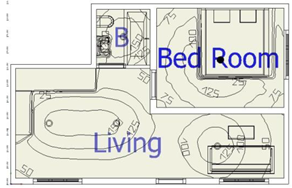

3.1. Development of Simulation Models Using DIALux

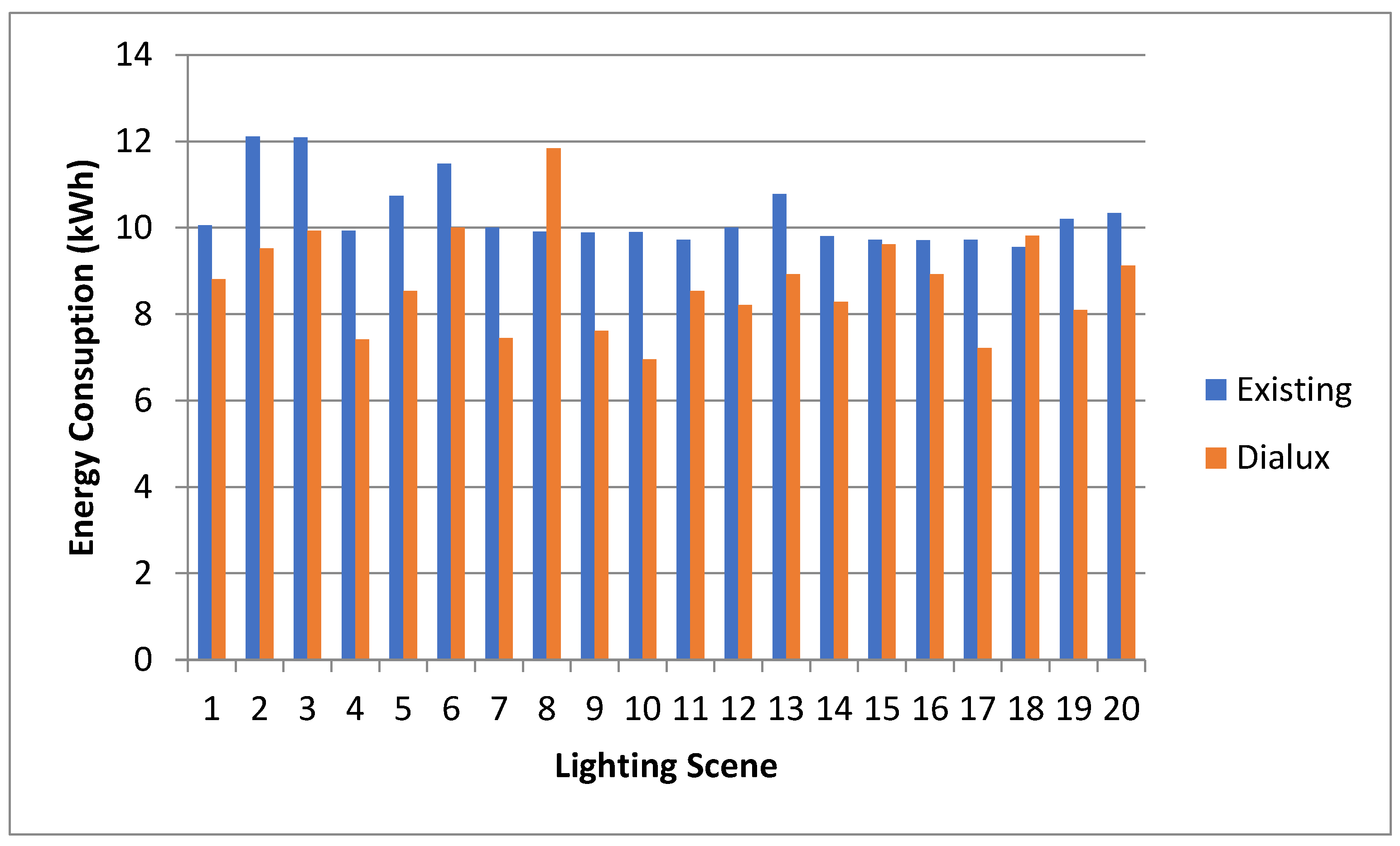

3.2. Energy Consumption Comparison

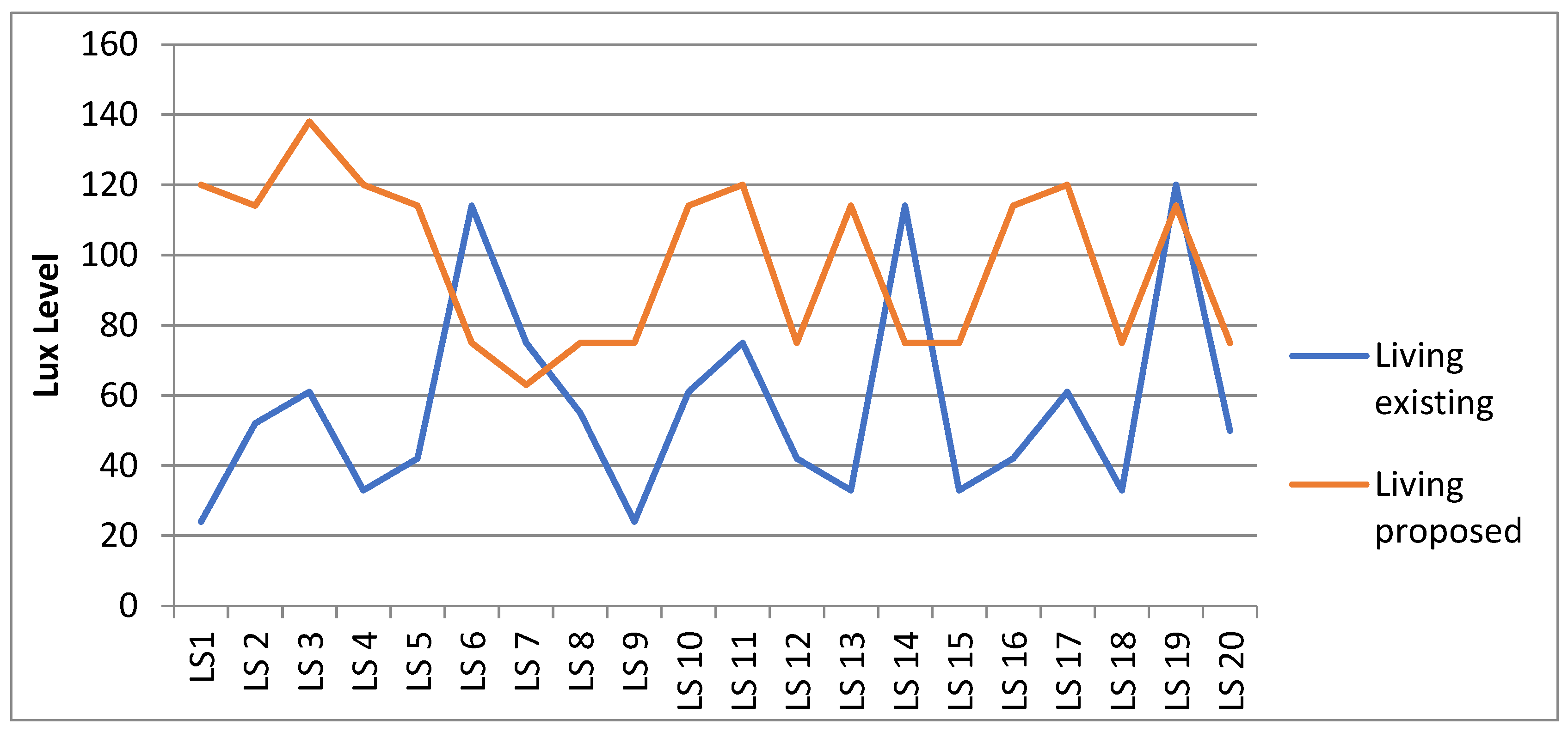

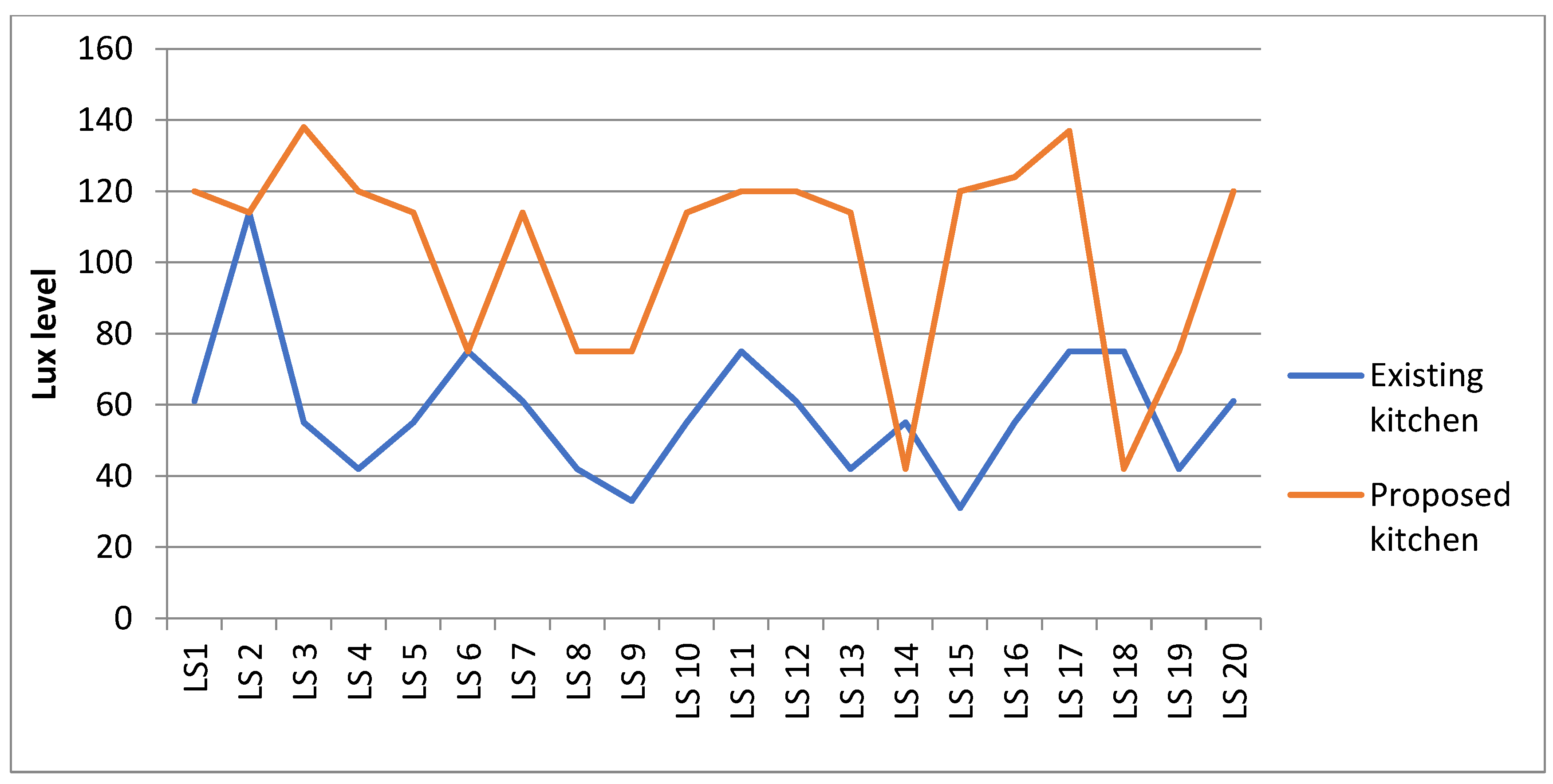

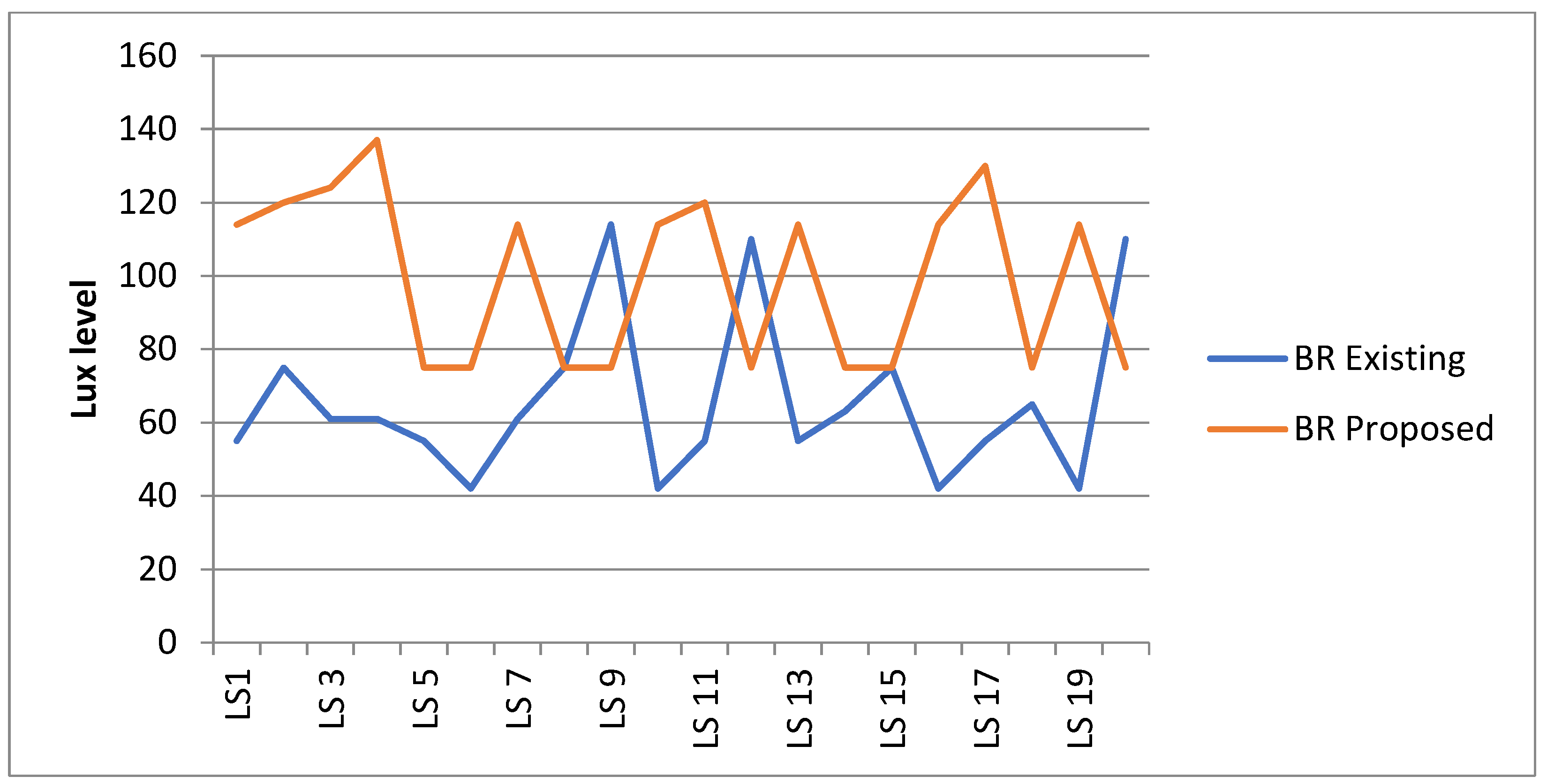

3.3. Comparison of Illuminance Levels Between Existing and Proposed Designs

| Area | Average lux levels | |||

| Living | Kitchen | Bed Room | Bathroom | |

| Lighting scene 1 | 72 | 123 | 89 | 70 |

| Lighting scene 2 | 92 | 110 | 76 | 90 |

| Lighting Scene 3 | 80 | 124 | 98 | 78 |

| Lighting Scene 4 | 96 | 110 | 75 | 67 |

| Lighting Scene 5 | 89 | 95 | 89 | 80 |

| Lighting Scene 6 | 74 | 169 | 94 | 72 |

| Lighting Scene 7 | 96 | 118 | 97 | 95 |

| Lighting Scene 8 | 105 | 132 | 82 | 79 |

| Lighting Scene 9 | 79 | 96 | 101 | 74 |

| Lighting Scene 10 | 96 | 116 | 93 | 89 |

| Lighting Scene 11 | 109 | 99 | 81 | 75 |

| Lighting Scene 12 | 78 | 97 | 70 | 79 |

| Lighting Scene 13 | 93 | 102 | 75 | 90 |

| Lighting Scene 14 | 98 | 121 | 80 | 98 |

| Lighting Scene 15 | 101 | 118 | 98 | 75 |

| Lighting Scene 16 | 74 | 93 | 110 | 97 |

| Lighting Scene 17 | 96 | 149 | 89 | 85 |

| Lighting Scene 18 | 79 | 117 | 83 | 73 |

| Lighting Scene 19 | 82 | 131 | 82 | 86 |

| Lighting Scene 20 | 121 | 112 | 104 | 89 |

| Area | Average lux levels | |||

| Living | Kitchen | Bed Room | Bathroom | |

| Lighting scene 1 | 74 | 123 | 93 | 65 |

| Lighting scene 2 | 94 | 121 | 89 | 82 |

| Lighting Scene 3 | 82 | 136 | 132 | 96 |

| Lighting Scene 4 | 110 | 126 | 89 | 110 |

| Lighting Scene 5 | 99 | 115 | 96 | 122 |

| Lighting Scene 6 | 84 | 171 | 132 | 89 |

| Lighting Scene 7 | 126 | 128 | 121 | 90 |

| Lighting Scene 8 | 115 | 142 | 106 | 89 |

| Lighting Scene 9 | 89 | 138 | 131 | 95 |

| Lighting Scene 10 | 136 | 126 | 136 | 112 |

| Lighting Scene 11 | 122 | 135 | 131 | 96 |

| Lighting Scene 12 | 112 | 122 | 99 | 88 |

| Lighting Scene 13 | 99 | 112 | 145 | 114 |

| Lighting Scene 14 | 125 | 131 | 135 | 94 |

| Lighting Scene 15 | 121 | 142 | 102 | 83 |

| Lighting Scene 16 | 174 | 129 | 135 | 119 |

| Lighting Scene 17 | 132 | 151 | 124 | 132 |

| Lighting Scene 18 | 129 | 131 | 93 | 124 |

| Lighting Scene 19 | 165 | 124 | 102 | 91 |

| Lighting Scene 20 | 126 | 132 | 136 | 82 |

3.4. Comparison of Luminous Efficiency

4. Discussion

4.1. Energy Efficiency and Performance Outcomes

4.2. Illuminance and Visual Comfort

4.3. Luminous Efficiency and Technological Integration

4.4. Comparative Insights and Practical Implications

4.5. Role of Daylight Harvesting and Future Directions

4.6. Lighting Quality Considerations

4.6.1. Effect of Position and Orientation of Fixtures

4.6.2. Effect of Spacing and Layout of Fixtures

4.6.3. Effect of Beam Angle and Light Distribution

4.6.4. Effect of Fixture Height and Mounting Position

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| REF | Distribution board for existing design | |||||||||

| HOUSE NUMBER | 1 | |||||||||

| NO. OF WAYS | 10 | |||||||||

| VOLTAGE | 230V/50Hz/1Ph | |||||||||

| Cct. | MCB | Cable | Earth | DESCRIPTION | ||||||

| Ref | (A) | (mm2) | (mm2) | DETAIL | Nr. | W | Nr. | W | R | |

| 1 | 10 | 2.5 | 2.5 | Lighting circuit 1 | 10 | 35 | 3 | 3 | 359 | |

| 2 | 10 | Spare | 0 | |||||||

| 3 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 1 | 3 | 200 | 600 | |||

| 4 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 2 | 4 | 200 | 800 | |||

| 5 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Water Heater | 1 | 1500 | 1500 | |||

| 6 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Space Heater | 1 | 3000 | 3000 | |||

| 7 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 8 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 9 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 10 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 6259 | ||||||||||

| TOTAL CONNECTED LOAD | (W) | 6259 | ||||||||

| DIVERSITY FACTOR | % | 0.30 | ||||||||

| DIVERSIFIED LOAD | (kW) | 1.88 | ||||||||

| REF | Distribution board for proposed design | |||||||||

| HOUSE NUMBER | 1 | |||||||||

| NO. OF WAYS | 10 | |||||||||

| VOLTAGE | 230V/50Hz/1Ph | |||||||||

| Cct. | MCB | Cable | Earth | DESCRIPTION | ||||||

| Ref | (A) | (mm2) | (mm2) | DETAIL | Nr. | W | Nr. | W | R | |

| 1 | 10 | 2.5 | 2.5 | Lighting circuit 1 | 12 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 66 | |

| 2 | 10 | Spare | 0 | |||||||

| 3 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 1 | 3 | 200 | 600 | |||

| 4 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 2 | 4 | 200 | 800 | |||

| 5 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Water Heater | 1 | 1500 | 1500 | |||

| 6 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Space Heater | 1 | 3000 | 3000 | |||

| 7 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 8 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 9 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 10 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 5966 | ||||||||||

| TOTAL CONNECTED LOAD | (W) | 5966 | ||||||||

| DIVERSITY FACTOR | % | 0.30 | ||||||||

| DIVERSIFIED LOAD | (kW) | 1.79 | ||||||||

| EF | Distribution board for existing design | |||||||||

| HOUSE NUMBER | 2 | |||||||||

| NO. OF WAYS | 10 | |||||||||

| VOLTAGE | 230V/50Hz/1Ph | |||||||||

| Cct. | MCB | Cable | Earth | DESCRIPTION | ||||||

| Ref | (A) | (mm2) | (mm2) | DETAIL | Nr. | W | Nr. | W | R | |

| 1 | 10 | 2.5 | 2.5 | Lighting circuit 1 | 8 | 24 | 3 | 3 | 201 | |

| 2 | 10 | Spare | 0 | |||||||

| 3 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 1 | 3 | 200 | 600 | |||

| 4 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 2 | 4 | 200 | 800 | |||

| 5 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Water Heater | 1 | 1500 | 1500 | |||

| 6 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Space Heater | 1 | 3000 | 3000 | |||

| 7 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 8 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 9 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 10 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 6101 | ||||||||||

| TOTAL CONNECTED LOAD | (W) | 6101 | ||||||||

| DIVERSITY FACTOR | % | 0.30 | ||||||||

| DIVERSIFIED LOAD | (kW) | 1.83 | ||||||||

| REF | Distribution board for proposed design | |||||||||

| HOUSE NUMBER | 2 | |||||||||

| NO. OF WAYS | 10 | |||||||||

| VOLTAGE | 230V/50Hz/1Ph | |||||||||

| Cct. | MCB | Cable | Earth | DESCRIPTION | ||||||

| Ref | (A) | (mm2) | (mm2) | DETAIL | Nr. | W | Nr. | W | R | |

| 1 | 10 | 2.5 | 2.5 | Lighting circuit 1 | 12 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 90 | |

| 2 | 10 | Spare | 0 | |||||||

| 3 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 1 | 3 | 200 | 600 | |||

| 4 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 2 | 4 | 200 | 800 | |||

| 5 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Water Heater | 1 | 1500 | 1500 | |||

| 6 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Space Heater | 1 | 3000 | 3000 | |||

| 7 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 8 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 9 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 10 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 5990 | ||||||||||

| TOTAL CONNECTED LOAD | (W) | 5990 | ||||||||

| DIVERSITY FACTOR | % | 0.30 | ||||||||

| DIVERSIFIED LOAD | (kW) | 1.80 | ||||||||

| REF | Distribution board for existing design | |||||||||

| HOUSE NUMBER | 3 | |||||||||

| NO. OF WAYS | 10 | |||||||||

| VOLTAGE | 230V/50Hz/1Ph | |||||||||

| Cct. | MCB | Cable | Earth | DESCRIPTION | ||||||

| Ref | (A) | (mm2) | (mm2) | DETAIL | Nr. | W | Nr. | W | R | |

| 1 | 10 | 2.5 | 2.5 | Lighting circuit 1 | 8 | 24 | 3 | 3 | 201 | |

| 2 | 10 | Spare | 0 | |||||||

| 3 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 1 | 3 | 200 | 600 | |||

| 4 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 2 | 4 | 200 | 800 | |||

| 5 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Water Heater | 1 | 1500 | 1500 | |||

| 6 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Space Heater | 1 | 3000 | 3000 | |||

| 7 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 8 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 9 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 10 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 6101 | ||||||||||

| TOTAL CONNECTED LOAD | (W) | 6101 | ||||||||

| DIVERSITY FACTOR | % | 0.30 | ||||||||

| DIVERSIFIED LOAD | (kW) | 1.83 | ||||||||

| REF | Distribution board for proposed design | |||||||||

| HOUSE NUMBER | 3 | |||||||||

| NO. OF WAYS | 10 | |||||||||

| VOLTAGE | 230V/50Hz/1Ph | |||||||||

| Cct. | MCB | Cable | Earth | DESCRIPTION | ||||||

| Ref | (A) | (mm2) | (mm2) | DETAIL | Nr. | W | Nr. | W | R | |

| 1 | 10 | 2.5 | 2.5 | Lighting circuit 1 | 10 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 76 | |

| 2 | 10 | Spare | 0 | |||||||

| 3 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 1 | 3 | 200 | 600 | |||

| 4 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 2 | 4 | 200 | 800 | |||

| 5 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Water Heater | 1 | 1500 | 1500 | |||

| 6 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Space Heater | 1 | 3000 | 3000 | |||

| 7 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 8 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 9 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 10 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 5976 | ||||||||||

| TOTAL CONNECTED LOAD | (W) | 5976 | ||||||||

| DIVERSITY FACTOR | % | 0.30 | ||||||||

| DIVERSIFIED LOAD | (kW) | 1.79 | ||||||||

| REF | Distribution board for existing design | |||||||||

| HOUSE NUMBER | 4 | |||||||||

| NO. OF WAYS | 10 | |||||||||

| VOLTAGE | 230V/50Hz/1Ph | |||||||||

| Cct. | MCB | Cable | Earth | DESCRIPTION | ||||||

| Ref | (A) | (mm2) | (mm2) | DETAIL | Nr. | W | Nr. | W | R | |

| 1 | 10 | 2.5 | 2.5 | Lighting circuit 1 | 8 | 24 | 4 | 7 | 220 | |

| 2 | 10 | Spare | 0 | |||||||

| 3 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 1 | 3 | 200 | 600 | |||

| 4 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 2 | 4 | 200 | 800 | |||

| 5 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Water Heater | 1 | 1500 | 1500 | |||

| 6 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Space Heater | 1 | 3000 | 3000 | |||

| 7 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 8 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 9 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 10 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 6120 | ||||||||||

| TOTAL CONNECTED LOAD | (W) | 6120 | ||||||||

| DIVERSITY FACTOR | % | 0.30 | ||||||||

| DIVERSIFIED LOAD | (kW) | 1.84 | ||||||||

| REF | Distribution board for proposed design | |||||||||

| HOUSE NUMBER | 4 | |||||||||

| NO. OF WAYS | 10 | |||||||||

| VOLTAGE | 230V/50Hz/1Ph | |||||||||

| Cct. | MCB | Cable | Earth | DESCRIPTION | ||||||

| Ref | (A) | (mm2) | (mm2) | DETAIL | Nr. | W | Nr. | W | R | |

| 1 | 10 | 2.5 | 2.5 | Lighting circuit 1 | 10 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 80 | |

| 2 | 10 | Spare | 0 | |||||||

| 3 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 1 | 3 | 200 | 600 | |||

| 4 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 2 | 4 | 200 | 800 | |||

| 5 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Water Heater | 1 | 1500 | 1500 | |||

| 6 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Space Heater | 1 | 3000 | 3000 | |||

| 7 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 8 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 9 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 10 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 5980 | ||||||||||

| TOTAL CONNECTED LOAD | (W) | 5980 | ||||||||

| DIVERSITY FACTOR | % | 0.30 | ||||||||

| DIVERSIFIED LOAD | (kW) | 1.79 | ||||||||

| REF | Distribution board for existing design | |||||||||

| HOUSE NUMBER | 5 | |||||||||

| NO. OF WAYS | 10 | |||||||||

| VOLTAGE | 230V/50Hz/1Ph | |||||||||

| Cct. | MCB | Cable | Earth | DESCRIPTION | ||||||

| Ref | (A) | (mm2) | (mm2) | DETAIL | Nr. | W | Nr. | W | R | |

| 1 | 10 | 2.5 | 2.5 | Lighting circuit 1 | 12 | 24 | 4 | 5 | 308 | |

| 2 | 10 | Spare | 0 | |||||||

| 3 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 1 | 3 | 200 | 600 | |||

| 4 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 2 | 4 | 200 | 800 | |||

| 5 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Water Heater | 1 | 1500 | 1500 | |||

| 6 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Space Heater | 1 | 3000 | 3000 | |||

| 7 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 8 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 9 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 10 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 6208 | ||||||||||

| TOTAL CONNECTED LOAD | (W) | 6208 | ||||||||

| DIVERSITY FACTOR | % | 0.30 | ||||||||

| DIVERSIFIED LOAD | (kW) | 1.86 | ||||||||

| REF | Distribution board for proposed design | |||||||||

| HOUSE NUMBER | 5 | |||||||||

| NO. OF WAYS | 10 | |||||||||

| VOLTAGE | 230V/50Hz/1Ph | |||||||||

| Cct. | MCB | Cable | Earth | DESCRIPTION | ||||||

| Ref | (A) | (mm2) | (mm2) | DETAIL | Nr. | W | Nr. | W | R | |

| 1 | 10 | 2.5 | 2.5 | Lighting circuit 1 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 62 | |

| 2 | 10 | Spare | 0 | |||||||

| 3 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 1 | 3 | 200 | 600 | |||

| 4 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 2 | 4 | 200 | 800 | |||

| 5 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Water Heater | 1 | 1500 | 1500 | |||

| 6 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Space Heater | 1 | 3000 | 3000 | |||

| 7 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 8 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 9 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 10 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 5962 | ||||||||||

| TOTAL CONNECTED LOAD | (W) | 5962 | ||||||||

| DIVERSITY FACTOR | % | 0.30 | ||||||||

| DIVERSIFIED LOAD | (kW) | 1.79 | ||||||||

| REF | Distribution board for existing design | |||||||||

| HOUSE NUMBER | 6 | |||||||||

| NO. OF WAYS | 10 | |||||||||

| VOLTAGE | 230V/50Hz/1Ph | |||||||||

| Cct. | MCB | Cable | Earth | DESCRIPTION | ||||||

| Ref | (A) | (mm2) | (mm2) | DETAIL | Nr. | W | Nr. | W | R | |

| 1 | 10 | 2.5 | 2.5 | Lighting circuit 1 | 8 | 35 | 4 | 3 | 292 | |

| 2 | 10 | Spare | 0 | |||||||

| 3 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 1 | 3 | 200 | 600 | |||

| 4 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 2 | 4 | 200 | 800 | |||

| 5 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Water Heater | 1 | 1500 | 1500 | |||

| 6 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Space Heater | 1 | 3000 | 3000 | |||

| 7 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 8 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 9 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 10 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 6192 | ||||||||||

| TOTAL CONNECTED LOAD | (W) | 6192 | ||||||||

| DIVERSITY FACTOR | % | 0.30 | ||||||||

| DIVERSIFIED LOAD | (kW) | 1.86 | ||||||||

| REF | Distribution board for proposed design | |||||||||

| HOUSE NUMBER | 6 | |||||||||

| NO. OF WAYS | 10 | |||||||||

| VOLTAGE | 230V/50Hz/1Ph | |||||||||

| Cct. | MCB | Cable | Earth | DESCRIPTION | ||||||

| Ref | (A) | (mm2) | (mm2) | DETAIL | Nr. | W | Nr. | W | R | |

| 1 | 10 | 2.5 | 2.5 | Lighting circuit 1 | 10 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 90 | |

| 2 | 10 | Spare | 0 | |||||||

| 3 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 1 | 3 | 200 | 600 | |||

| 4 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 2 | 4 | 200 | 800 | |||

| 5 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Water Heater | 1 | 1500 | 1500 | |||

| 6 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Space Heater | 1 | 3000 | 3000 | |||

| 7 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 8 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 9 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 10 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 5990 | ||||||||||

| TOTAL CONNECTED LOAD | (W) | 5990 | ||||||||

| DIVERSITY FACTOR | % | 0.30 | ||||||||

| DIVERSIFIED LOAD | (kW) | 1.80 | ||||||||

| REF | Distribution board for existing design | |||||||||

| HOUSE NUMBER | 7 | |||||||||

| NO. OF WAYS | 10 | |||||||||

| VOLTAGE | 230V/50Hz/1Ph | |||||||||

| Cct. | MCB | Cable | Earth | DESCRIPTION | ||||||

| Ref | (A) | (mm2) | (mm2) | DETAIL | Nr. | W | Nr. | W | R | |

| 1 | 10 | 2.5 | 2.5 | Lighting circuit 1 | 8 | 24 | 5 | 12 | 252 | |

| 2 | 10 | Spare | 0 | |||||||

| 3 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 1 | 3 | 200 | 600 | |||

| 4 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 2 | 4 | 200 | 800 | |||

| 5 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Water Heater | 1 | 1500 | 1500 | |||

| 6 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Space Heater | 1 | 3000 | 3000 | |||

| 7 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 8 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 9 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 10 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 6152 | ||||||||||

| TOTAL CONNECTED LOAD | (W) | 6152 | ||||||||

| DIVERSITY FACTOR | % | 0.30 | ||||||||

| DIVERSIFIED LOAD | (kW) | 1.85 | ||||||||

| REF | Distribution board for proposed design | |||||||||

| HOUSE NUMBER | 7 | |||||||||

| NO. OF WAYS | 10 | |||||||||

| VOLTAGE | 230V/50Hz/1Ph | |||||||||

| Cct. | MCB | Cable | Earth | DESCRIPTION | ||||||

| Ref | (A) | (mm2) | (mm2) | DETAIL | Nr. | W | Nr. | W | R | |

| 1 | 10 | 2.5 | 2.5 | Lighting circuit 1 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 75 | |

| 2 | 10 | Spare | 0 | |||||||

| 3 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 1 | 3 | 200 | 600 | |||

| 4 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 2 | 4 | 200 | 800 | |||

| 5 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Water Heater | 1 | 1500 | 1500 | |||

| 6 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Space Heater | 1 | 3000 | 3000 | |||

| 7 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 8 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 9 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 10 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 5975 | ||||||||||

| TOTAL CONNECTED LOAD | (W) | 5975 | ||||||||

| DIVERSITY FACTOR | % | 0.30 | ||||||||

| DIVERSIFIED LOAD | (kW) | 1.79 | ||||||||

| REF | Distribution board for existing design | |||||||||

| HOUSE NUMBER | 8 | |||||||||

| NO. OF WAYS | 10 | |||||||||

| VOLTAGE | 230V/50Hz/1Ph | |||||||||

| Cct. | MCB | Cable | Earth | DESCRIPTION | ||||||

| Ref | (A) | (mm2) | (mm2) | DETAIL | Nr. | W | Nr. | W | R | |

| 1 | 10 | 2.5 | 2.5 | Lighting circuit 1 | 6 | 35 | 5 | 12 | 270 | |

| 2 | 10 | Spare | 0 | |||||||

| 3 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 1 | 3 | 200 | 600 | |||

| 4 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 2 | 4 | 200 | 800 | |||

| 5 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Water Heater | 1 | 1500 | 1500 | |||

| 6 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Space Heater | 1 | 3000 | 3000 | |||

| 7 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 8 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 9 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 10 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 6170 | ||||||||||

| TOTAL CONNECTED LOAD | (W) | 6170 | ||||||||

| DIVERSITY FACTOR | % | 0.30 | ||||||||

| DIVERSIFIED LOAD | (kW) | 1.85 | ||||||||

| REF | Distribution board for proposed design | |||||||||

| HOUSE NUMBER | 8 | |||||||||

| NO. OF WAYS | 10 | |||||||||

| VOLTAGE | 230V/50Hz/1Ph | |||||||||

| Cct. | MCB | Cable | Earth | DESCRIPTION | ||||||

| Ref | (A) | (mm2) | (mm2) | DETAIL | Nr. | W | Nr. | W | R | |

| 1 | 10 | 2.5 | 2.5 | Lighting circuit 1 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 7 | 86 | |

| 2 | 10 | Spare | 0 | |||||||

| 3 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 1 | 3 | 200 | 600 | |||

| 4 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 2 | 4 | 200 | 800 | |||

| 5 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Water Heater | 1 | 1500 | 1500 | |||

| 6 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Space Heater | 1 | 3000 | 3000 | |||

| 7 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 8 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 9 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 10 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 5986 | ||||||||||

| TOTAL CONNECTED LOAD | (W) | 5986 | ||||||||

| DIVERSITY FACTOR | % | 0.30 | ||||||||

| DIVERSIFIED LOAD | (kW) | 1.80 | ||||||||

| REF | Distribution board for existing design | |||||||||

| HOUSE NUMBER | 9 | |||||||||

| NO. OF WAYS | 10 | |||||||||

| VOLTAGE | 230V/50Hz/1Ph | |||||||||

| Cct. | MCB | Cable | Earth | DESCRIPTION | ||||||

| Ref | (A) | (mm2) | (mm2) | DETAIL | Nr. | W | Nr. | W | R | |

| 1 | 10 | 2.5 | 2.5 | Lighting circuit 1 | 8 | 24 | 6 | 13 | 270 | |

| 2 | 10 | Spare | 0 | |||||||

| 3 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 1 | 3 | 200 | 600 | |||

| 4 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 2 | 4 | 200 | 800 | |||

| 5 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Water Heater | 1 | 1500 | 1500 | |||

| 6 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Space Heater | 1 | 3000 | 3000 | |||

| 7 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 8 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 9 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 10 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 6170 | ||||||||||

| TOTAL CONNECTED LOAD | (W) | 6170 | ||||||||

| DIVERSITY FACTOR | % | 0.30 | ||||||||

| DIVERSIFIED LOAD | (kW) | 1.85 | ||||||||

| REF | Distribution board for proposed design | |||||||||

| HOUSE NUMBER | 9 | |||||||||

| NO. OF WAYS | 10 | |||||||||

| VOLTAGE | 230V/50Hz/1Ph | |||||||||

| Cct. | MCB | Cable | Earth | DESCRIPTION | ||||||

| Ref | (A) | (mm2) | (mm2) | DETAIL | Nr. | W | Nr. | W | R | |

| 1 | 10 | 2.5 | 2.5 | Lighting circuit 1 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 68 | |

| 2 | 10 | Spare | 0 | |||||||

| 3 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 1 | 3 | 200 | 600 | |||

| 4 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 2 | 4 | 200 | 800 | |||

| 5 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Water Heater | 1 | 1500 | 1500 | |||

| 6 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Space Heater | 1 | 3000 | 3000 | |||

| 7 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 8 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 9 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 10 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 5968 | ||||||||||

| TOTAL CONNECTED LOAD | (W) | 5968 | ||||||||

| DIVERSITY FACTOR | % | 0.30 | ||||||||

| DIVERSIFIED LOAD | (kW) | 1.79 | ||||||||

| REF | Distribution board for existing design | |||||||||

| HOUSE NUMBER | 10 | |||||||||

| NO. OF WAYS | 10 | |||||||||

| VOLTAGE | 230V/50Hz/1Ph | |||||||||

| Cct. | MCB | Cable | Earth | DESCRIPTION | ||||||

| Ref | (A) | (mm2) | (mm2) | DETAIL | Nr. | W | Nr. | W | R | |

| 1 | 10 | 2.5 | 2.5 | Lighting circuit 1 | 10 | 35 | 4 | 3 | 362 | |

| 2 | 10 | Spare | 0 | |||||||

| 3 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 1 | 3 | 200 | 600 | |||

| 4 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 2 | 4 | 200 | 800 | |||

| 5 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Water Heater | 1 | 1500 | 1500 | |||

| 6 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Space Heater | 1 | 3000 | 3000 | |||

| 7 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 8 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 9 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 10 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 6262 | ||||||||||

| TOTAL CONNECTED LOAD | (W) | 6262 | ||||||||

| DIVERSITY FACTOR | % | 0.30 | ||||||||

| DIVERSIFIED LOAD | (kW) | 1.88 | ||||||||

| REF | Distribution board for proposed design | |||||||||

| HOUSE NUMBER | 10 | |||||||||

| NO. OF WAYS | 10 | |||||||||

| VOLTAGE | 230V/50Hz/1Ph | |||||||||

| Cct. | MCB | Cable | Earth | DESCRIPTION | ||||||

| Ref | (A) | (mm2) | (mm2) | DETAIL | Nr. | W | Nr. | W | R | |

| 1 | 10 | 2.5 | 2.5 | Lighting circuit 1 | 12 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 75 | |

| 2 | 10 | Spare | 0 | |||||||

| 3 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 1 | 3 | 200 | 600 | |||

| 4 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Power circuit 2 | 4 | 200 | 800 | |||

| 5 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Water Heater | 1 | 1500 | 1500 | |||

| 6 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Space Heater | 1 | 3000 | 3000 | |||

| 7 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 8 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 9 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 10 | 20 | Spare | ||||||||

| 5975 | ||||||||||

| TOTAL CONNECTED LOAD | (W) | 5975 | ||||||||

| DIVERSITY FACTOR | % | 0.30 | ||||||||

| DIVERSIFIED LOAD | (kW) | 1.79 | ||||||||

References

- Carbon Trust Residential Lighting Challenges and Solutions. Carbon Trust Publ. 2019.

- Ciardiello Energy Inefficiency in UK Homes. Build. Serv. J. 2020.

- Sonta, A. Restoring Older Structures for Energy Efficiency. Energy Build. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.& B. Renovation Strategies for Energy Reduction. J. Sustain. Archit. 2020.

- Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers. Lighting Control and Flexibility in Residential Design; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- National Library of Medicine Circadian Rhythm and Lighting Health Impacts. Med. Light. Rev. 2021.

- Jalali, M.S.; Jones, J.R.; Tural, E.; Gibbons, R.B. Human-Centric Lighting Design: A Framework for Supporting Healthy Circadian Rhythm Grounded in Established Knowledge in Interior Spaces. Buildings 2024, 14, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergesen Gibon & Suh, T. Environmental Impact of Inefficient Lighting. J. Clean. Prod. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, B.& Lighting Design and Health Impacts. Light. Res. Technol. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Chiradeja, P.; Yoomak, S. Development of Public Lighting System with Smart Lighting Control Systems and Internet of Thing (IoT) Technologies for Smart City. Energy Reports 2023, 10, 3355–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HM Government Conservation of Fuel and Power - Approved Document L. Build. Regul. 2010 2023, 1. Government UK Net Zero and Part L Compliance. B.

- Reinhart, C. Manual vs Simulation-Based Lighting Design. Build. Environ. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lighting, P. DIALux and CAD Tools for Lighting Design. Light. Des. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, B.; Boubekri, M. Sustainable Architecture and Human Health: A Case for Effective Circadian Daylighting Metrics. Buildings 2025, 15, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooban, A. UK Energy Crisis Is ‘Bigger than the Pandemic’. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2022/08/24/energy/energy-crisis-uk-cost-pandemic/index.html (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Steffy, G. Architectural Lighting Design, 3rd ed.; Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2008; ISBN 978-0-470-11249-6. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Y.; et al. Effects of Blue Light on Melatonin Suppression. J. Biol. Rhythms 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, S.; et al. Impact of Residential Lighting Design on Sleep Quality. Light. Res. Technol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, M.T.; Trebucq, L.L.; Senna, C.A.; Hokama, G.; Paladino, N.; Agostino, P.V.; Chiesa, J.J. Circadian Disruption of Feeding-Fasting Rhythm and Its Consequences for Metabolic, Immune, Cancer, and Cognitive Processes. Biomed. J. 2025, 48, 100827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- (CEN) European Committee for Standardization Light and Lighting—Lighting of Workplaces—Indoor Workplaces. EN 12464-12011, 2011.

- (CIBSE) Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers Lighting Guide LG7: Office Lighting. CIBSE LG7, 2015.

- Aliparast, S.; Onaygil, S. A Field Study of Individual, Energy-Efficient, and Human-Centered Indoor Electric Lighting: Its Impact on Comfort and Visual Performance in an Open-Plan Office. Buildings 2024, 14, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trząski, A.; Rucińska, J. Integration of Daylight in Building Design as a Way to Improve the Energy Efficiency of Buildings. Energies 2025, 18, 4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zocchi, G.; Hosseini, M.; Triantafyllidis, G. Exploring the Synergy of Advanced Lighting Controls, Building Information Modelling and Internet of Things for Sustainable and Energy-Efficient Buildings: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lighting Scene | Recreated existing lighting design for manual calculation & details of the lights using | Proposed lighting design using DIALux calculations & details of the lights using |

|

LS1 |

Living – 20W CFL Bed room – 15W CFL Bath room – 12W CFL |

Living – 10W LED Bed room – 10W LED Bath room – 8W LED |

| LS2 |

Living, Kitchen, bed room – 12W CFL Bath room – 10W CFL |

Living, kitchen – 10W LED Bed room -8W LED Bath room – 3W LED |

|

LS3 |

Living & bed room – 10W LED Bath room – 8W LED |

Living & bed room- 8W LED Bath room – 3W LED |

|

LS4 |

Living & bed room – 10W LED Bath room – 8W LED |

Living & bed room – 12W LED Bath room – 3W LED |

|

LS5 |

Living & kitchen – 10W LED Bed room – 10W LED Bath room – 8W LED |

Living & kitchen -8W LED Bed room – 5W LED Bath room – 3W LED |

|

LS6 |

Living – 10W LED Entrance – 8W LED Bed room – 10W LED Bath room – 8W LED |

Living & entrance – 8W LED Bed room – 10W LED Bath room – 3W LED |

| LS7 |

Living, entrance & kitchen-20W CFL Bed & bath room-10W CFL |

Living, entrance, kitchen & bed room -10W LED Bath room -3W LED |

| LS8 |

Living & bed room – 10W LED Bath room – 8W LED |

Living & bed room – 5W LED Bath room-3W LED |

|

LS9 |

Living – 13W CFL Bed room & bath room-10W CFL |

Living – 8W LED Bed room & bath room-10W LED |

|

LS10 |

Living & bed room – 18W CFL Bath room – 10W CFL |

Living & bed room – 8W LED Bath room – 5W LED |

| LS 11 |

Living -15W CFL Bed room – 8W CFL Bath room – 10W CFL |

Living-3W LED Bed rom & bath room-8W LED |

| LS12 |

Living – 10W LED Bed room-13W LED Kitchen-5W LED |

Living & kitchen – 5W LED Bed room-3W LED |

| LS13 |

Living & kitchen-12W CFL Bed room-10W CFL Bath room-12W CFL |

Living -3W LED Bed room-8W LED Bath room-3W LED |

| LS14 |

Living & bed room-20W CFL Bath room-12W CFL |

Living-3W LED Bed room -8W LED Bath room-5W LED |

| LS 15 |

Living, bed room & kitchen -20W CFL Bath room -8W CFL |

Living & kitchen -5W LED Bed room & bath room-10W LED |

| LS 16 |

Living & bed room -13W CFL Kitchen -20W CFL Bath room-10W CFL |

Living -5W LED Bed room -8W LED Kitchen -10W CFL Bath room-3W LED |

| LS17 |

Living & kitchen -15W LED Bed -20W LED Bath room-10W LED |

Living, 5. W LED Bath room – 8W LED |

| LS 18 |

Livning-20W CFL Bed – 15W CFL Bath room – 8W CFL |

Living, bed room – 5W LED Bath room – 8W LED |

|

LS 19 |

Living & Bed room – 13W LED Bath room- 10 LED |

Living & bed room- 5W LED Bath room -8W LED |

| LS20 |

Living & Kitchen – 10W CFL Bed room -12W CFL Bath room – 13 W CFL |

Living & kitchen – 8W LED Bed room – 7.5W LED |

| Existing energy Consumption (kWh) | Energy Consumption after applying DIALux (kWh) | |

| Lighting Scene 1 | 10.06 | 8.81 |

| Lighting Scene 2 | 12.11 | 9.52 |

| Lighting Scene 3 | 12.09 | 9.93 |

| Lighting Scene 4 | 9.93 | 7.41 |

| Lighting Scene 5 | 10.74 | 8.54 |

| Lighting Scene 6 | 11.48 | 10 |

| Lighting Scene 7 | 10 | 7.45 |

| Lighting Scene 8 | 9.91 | 11.84 |

| Lighting Scene 9 | 9.89 | 7.61 |

| Lighting Scene 10 | 9.9 | 6.95 |

| Lighting Scene 11 | 9.72 | 8.54 |

| Lighting Scene 12 | 10 | 8.21 |

| Lighting Scene 13 | 10.776 | 8.92 |

| Lighting Scene 14 | 9.81 | 8.28 |

| Lighting Scene 15 | 9.72 | 9.62 |

| Lighting Scene 16 | 9.71 | 8.92 |

| Lighting Scene 17 | 9.72 | 7.21 |

| Lighting Scene 18 | 9.55 | 9.82 |

| Lighting Scene 19 | 10.2 | 8.1 |

| Lighting Scene 20 | 10.34 | 9.12 |

| Data Sample | Mean | Variance | Standard deviation |

| Calculated existing energy consumption | 10.25428 | 0.55338 | 0.743867 |

| Calculated DIALux simulated consumption | 8.68047 | 1.33819 | 1.1568037 |

| Sample | Mean | Variance | Standard Deviation |

| Existing design | 94.357 | 367.726 | 19.176 |

| Proposed design | 116.930 | 509.21 | 22.566 |

| Sample | Living | Kitchen | Bed room | Bathroom | ||||

| Manual | DIALux | Manual | DIALux | Manual | DIALux | Manual | DIALux | |

| Mean | 57.2 | 98.25 | 58.25 | 98.25 | 65.65 | 99.5 | 64.55 | 105.35 |

| Variance | 863.010 | 554.09 | 355.25 | 1225.25 | 495.292 | 549.527 | 436.365 | 465.187 |

| Std Dev. | 29.377 | 23.539 | 18.848 | 35.004 | 22.255 | 23.445 | 20.889 | 21.568 |

| Area | t-test | p-value |

| Living | 4.8767 | 0.000010 |

| Kitchen | 4.4996 | 0.000031 |

| Bed room | 4.6835 | 0.000018 |

| Bathroom | 6.0769 | 0.000001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).